Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia ( fa, حمله مغول به خوارزمشاهیان) took place between 1219 and 1221, as troops of the

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe ...

under Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr /> Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin ...

invaded the lands of the Khwarazmian Empire

The Khwarazmian or Khwarezmian Empire) or the Khwarazmshahs ( fa, خوارزمشاهیان, Khwārazmshāhiyān) () was a Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim empire that ruled large parts of present-day Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran in the appr ...

in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

. The campaign, which followed the annexation of the Qara Khitai

The Qara Khitai, or Kara Khitai (), also known as the Western Liao (), officially the Great Liao (), was a Sinicized dynastic regime based in Central Asia ruled by the Khitan Yelü clan. The Qara Khitai is considered by historians to be a ...

khanate, saw widespread devastation and atrocities, and marked the completion of the Mongol conquest of Central Asia

The Mongol invasion of Central Asia occurred after the unification of the Mongol and Turkic tribes on the Mongolian plateau in 1206. It was finally complete when Genghis Khan conquered the Khwarizmian Empire in 1221.

Qara Khitai (1216-1218)

Th ...

, and began the Mongol conquest of Persia.

Both belligerents, although large, had been formed recently: the Khwarazmian dynasty

The Anushtegin dynasty or Anushteginids (English: , fa, ), also known as the Khwarazmian dynasty ( fa, ) was a PersianateC. E. BosworthKhwarazmshahs i. Descendants of the line of Anuštigin In Encyclopaedia Iranica, online ed., 2009: ''"Li ...

had expanded from their homeland to replace the Seljuk Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to ...

in the late 1100s and early 1200s; near-simultaneously, Genghis Khan had unified the Mongolic peoples

The Mongolic peoples are a collection of East Asian originated ethnic groups in East, North, South Asia and Eastern Europe, who speak Mongolic languages. Their ancestors are referred to as Proto-Mongols. The largest contemporary Mongolic e ...

and conquered the Western Xia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

dynasty. Although relations were initially cordial, Genghis was angered by a series of diplomatic provocations. When a senior Mongol diplomat was executed by Khwarazmshah Muhammed II, the Khan mobilized his forces, estimated to be between 90,000 and 200,000 men, and invaded. The Shah's forces were widely dispersed and probably outnumbered — realizing his disadvantage, he decided to garrison his cities individually to bog the Mongols down. However, through excellent organization and planning, they were able to isolate and conquer the Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (Land beyond the Oxus) is the Latin name for a region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to modern-day eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

n cities of Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

, Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

, and Gurganj. Genghis and his youngest son Tolui

Tolui (also Toluy, Tului; , meaning: "the mirror"; – 1232) was a Mongol khan, the fourth son of Genghis Khan by his chief khatun, Börte. At his father's death in 1227, his '' ulus'', or territorial inheritance, was the Mongol homelands on ...

then laid waste to Khorasan, destroying Herat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Saf ...

, Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

, and Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

, three of the largest cities in the world. Meanwhile, Muhammed II was forced into flight by the Mongol generals Subutai

Subutai ( Classical Mongolian: ''Sübügätäi'' or ''Sübü'ätäi''; Modern Mongolian: Сүбээдэй, ''Sübeedei''. ; ; c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He directed ...

and Jebe; unable to reach any bastions of support, he died destitute on an island in the Caspian Sea. His son and heir Jalal-al Din managed to mobilize substantial forces, defeating a Mongol general at the Battle of Parwan; he was however crushed by Genghis himself at the Battle of the Indus

The Battle of the Indus was fought on the banks of the Indus River, on 24 November 1221, by two armies commanded by Shah Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu of the Khwarezmian Empire, and Genghis Khan of the Mongol Empire. The battle, which resulted in an ...

a few months later.

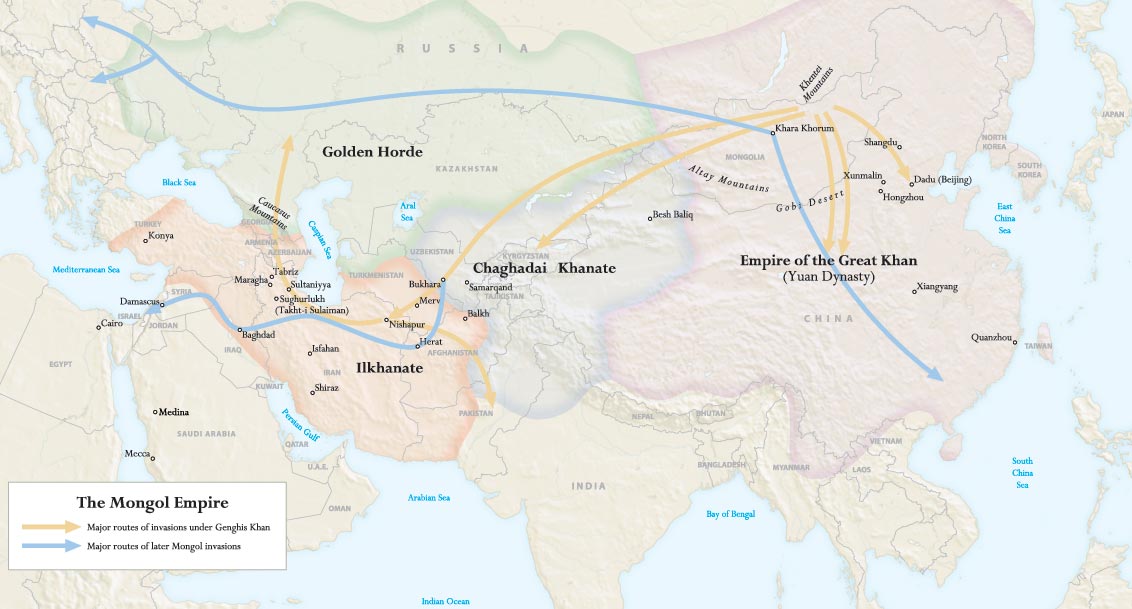

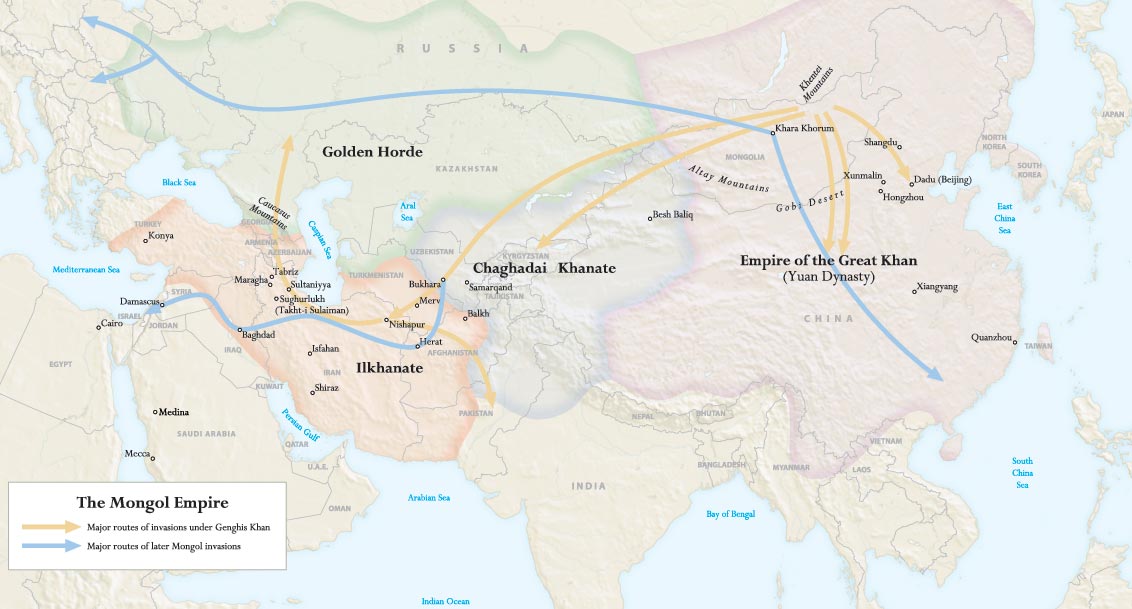

After clearing up any remaining resistance, Genghis returned to his war against the Jin dynasty in 1223. The war had been one of the bloodiest in human history, with total casualties estimated to be between two and fifteen million people. The subjugation of the Khwarazmian lands would provide a base for the Mongols' later assaults on Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

and the rest of Persia; when the empire later divided into separate khanates, the Persian lands formerly ruled by the Khwarazmids would be governed by the Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

, while the northern cities would be ruled by the Chagatai Khanate

The Chagatai Khanate, or Chagatai Ulus ( xng, , translit=Čaɣatay-yin Ulus; mn, Цагаадайн улс, translit=Tsagaadain Uls; chg, , translit=Čağatāy Ulusi; fa, , translit=Xânât-e Joghatây) was a Mongol and later Turkicized kh ...

. The campaign, which saw the Mongols engage and defeat a non-sinicized

Sinicization, sinofication, sinification, or sinonization (from the prefix , 'Chinese, relating to China') is the process by which non-Chinese societies come under the influence of Chinese culture, particularly the language, societal norms, cul ...

state for the first time, was a pivotal moment in the growth of the Mongol Empire.

Background

The dominant force in late twelfth-centuryCentral Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

was the Qara-Khitai khanate

A khaganate or khanate was a polity ruled by a khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. That political territory was typically found on the Eurasian Steppe and could be equivalent in status to tribal chiefdom, principality, kingdom or empire.

...

, which had been founded by Yelü Dashi in the 1130s. Khwarazm

Khwarazm (; Old Persian: ''Hwârazmiya''; fa, خوارزم, ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the e ...

and the Qarakhanids

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (; ), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids or the Afrasiabids (), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek K ...

were nominally vassals of the Qara-Khitai, but in practice, due to their large population and extent, they were allowed to operate almost autonomously. Of these two major vassals, the Qarakhanids were by far the more prestigious: they had ruled in the area for two centuries, and controlled many of the richest cities in the area, such as Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

, Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

, Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of ...

and Fergana

Fergana ( uz, Fargʻona/Фарғона, ), or Ferghana, is a district-level city and the capital of Fergana Region in eastern Uzbekistan. Fergana is about 420 km east of Tashkent, about 75 km west of Andijan, and less than 20 km ...

. By comparison, Khwarazm had only one major city in Urgench

Urgench ( uz, Urganch//, ; russian: Ургенч, Urgench; fa, گرگانج, ''Gorgånch/Gorgānč/Gorgânc/Gurganj'') is a district-level city in western Uzbekistan. It is the capital of Xorazm Region. The estimated population of Urgench in ...

, and had only come to prominence after 1150 under Il-Arslan

Il-Arslan ("The Lion") (full name: ''Taj ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Abul-Fath Il-Arslan ibn Atsiz'', Persian: تاج الدین ابوالفتح ایل ارسلان بن اتسز) (died March 1172) was the Shah of Khwarezm from 1156 until 1172. He was th ...

.

However, as the Seljuk Empire

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to ...

slowly fractured after the death of Ahmad Sanjar

Senjer ( fa, ; full name: ''Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Adud ad-Dawlah Abul-Harith Ahmad Sanjar ibn Malik-Shah'') (''b''. 1085 – ''d''. 8 May 1157) was the Seljuq ruler of Khorasan from 1097 until in 1118,Tekish captured large cities such as

Though they technically bordered each other, the Mongol and Khwarezm Empires touched far away from the homeland of each nation. In between them was a series of treacherous mountain ranges that the invader would have to cross. This aspect is often overlooked in this campaign, yet it was a critical reason why the Mongols were able to create a dominating position. The Khwarezm Shah and his advisers assumed that the Mongols would invade through the Dzungarian Gate, the natural mountain pass in between their (now conquered) Khara-Khitai and Khwarezm Empires. One option for the Khwarezm defence was to advance beyond the towns of the Syr Darya and block the Dzungarian Gate with an army, since it would take Genghis many months to gather his army in Mongolia and advance through the pass after winter had passed. The Khwarezm decision makers believed they would have time to further refine their strategy, but the Khan had struck first.

Immediately when war was declared, Genghis sent orders for a force already out to the west to immediately cross the Tien Shan mountains to the south and ravage the fertile

Though they technically bordered each other, the Mongol and Khwarezm Empires touched far away from the homeland of each nation. In between them was a series of treacherous mountain ranges that the invader would have to cross. This aspect is often overlooked in this campaign, yet it was a critical reason why the Mongols were able to create a dominating position. The Khwarezm Shah and his advisers assumed that the Mongols would invade through the Dzungarian Gate, the natural mountain pass in between their (now conquered) Khara-Khitai and Khwarezm Empires. One option for the Khwarezm defence was to advance beyond the towns of the Syr Darya and block the Dzungarian Gate with an army, since it would take Genghis many months to gather his army in Mongolia and advance through the pass after winter had passed. The Khwarezm decision makers believed they would have time to further refine their strategy, but the Khan had struck first.

Immediately when war was declared, Genghis sent orders for a force already out to the west to immediately cross the Tien Shan mountains to the south and ravage the fertile

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Gurganj was still in the hands of Khwarezmian forces. Previously, the Shah's mother had ruled Gurganj, but she fled when she learned her son had absconded to the Caspian Sea. She was captured and sent to Mongolia.

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Gurganj was still in the hands of Khwarezmian forces. Previously, the Shah's mother had ruled Gurganj, but she fled when she learned her son had absconded to the Caspian Sea. She was captured and sent to Mongolia.  The assault on Gurganj proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. The city was built along the river

The assault on Gurganj proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. The city was built along the river  Such tensions were present as Jochi engaged in negotiations with the defenders, trying to get them to surrender so that as much of the city as possible was undamaged. This angered Chaghatai, and Genghis headed off this fight between siblings by appointing Ögedei the commander of the besieging forces as Gurganj fell. But the removal of Jochi from command, and the sack of a city he considered promised to him, enraged him and estranged him from his father and brothers, and is credited with being a decisive impetus for the later actions of a man who saw his younger brothers promoted over him, despite his own considerable military skills.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar

Such tensions were present as Jochi engaged in negotiations with the defenders, trying to get them to surrender so that as much of the city as possible was undamaged. This angered Chaghatai, and Genghis headed off this fight between siblings by appointing Ögedei the commander of the besieging forces as Gurganj fell. But the removal of Jochi from command, and the sack of a city he considered promised to him, enraged him and estranged him from his father and brothers, and is credited with being a decisive impetus for the later actions of a man who saw his younger brothers promoted over him, despite his own considerable military skills.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar

The war with Khwarezmia also brought up the important question of succession. Genghis was not young when the war began, and he had four sons, all of whom were fierce warriors and each of them had their own loyal group of followers. Their sibling rivalry almost came to a head during the siege of Urgench, and Genghis was forced to rely on his third son, Ögedei, who ended the battle. Following the destruction of Urgench, Genghis officially selected Ögedei to be his successor, and he also ruled that future Khans would be the direct descendants of previous rulers. Despite Genghis's establishment of this practice, the four sons would eventually come to blows, and those blows revealed the instability of the Khanate that Genghis had created.

Jochi never forgave his father, and he essentially withdrew from future Mongol wars, he moved to the north, and he refused to come to his father when he was ordered to. Indeed, at the time of his death, the Khan was contemplating a march on his rebellious son. The bitterness that resulted from this event was transmitted to Jochi's sons, especially Batu and Berke Khan (of the

The war with Khwarezmia also brought up the important question of succession. Genghis was not young when the war began, and he had four sons, all of whom were fierce warriors and each of them had their own loyal group of followers. Their sibling rivalry almost came to a head during the siege of Urgench, and Genghis was forced to rely on his third son, Ögedei, who ended the battle. Following the destruction of Urgench, Genghis officially selected Ögedei to be his successor, and he also ruled that future Khans would be the direct descendants of previous rulers. Despite Genghis's establishment of this practice, the four sons would eventually come to blows, and those blows revealed the instability of the Khanate that Genghis had created.

Jochi never forgave his father, and he essentially withdrew from future Mongol wars, he moved to the north, and he refused to come to his father when he was ordered to. Indeed, at the time of his death, the Khan was contemplating a march on his rebellious son. The bitterness that resulted from this event was transmitted to Jochi's sons, especially Batu and Berke Khan (of the

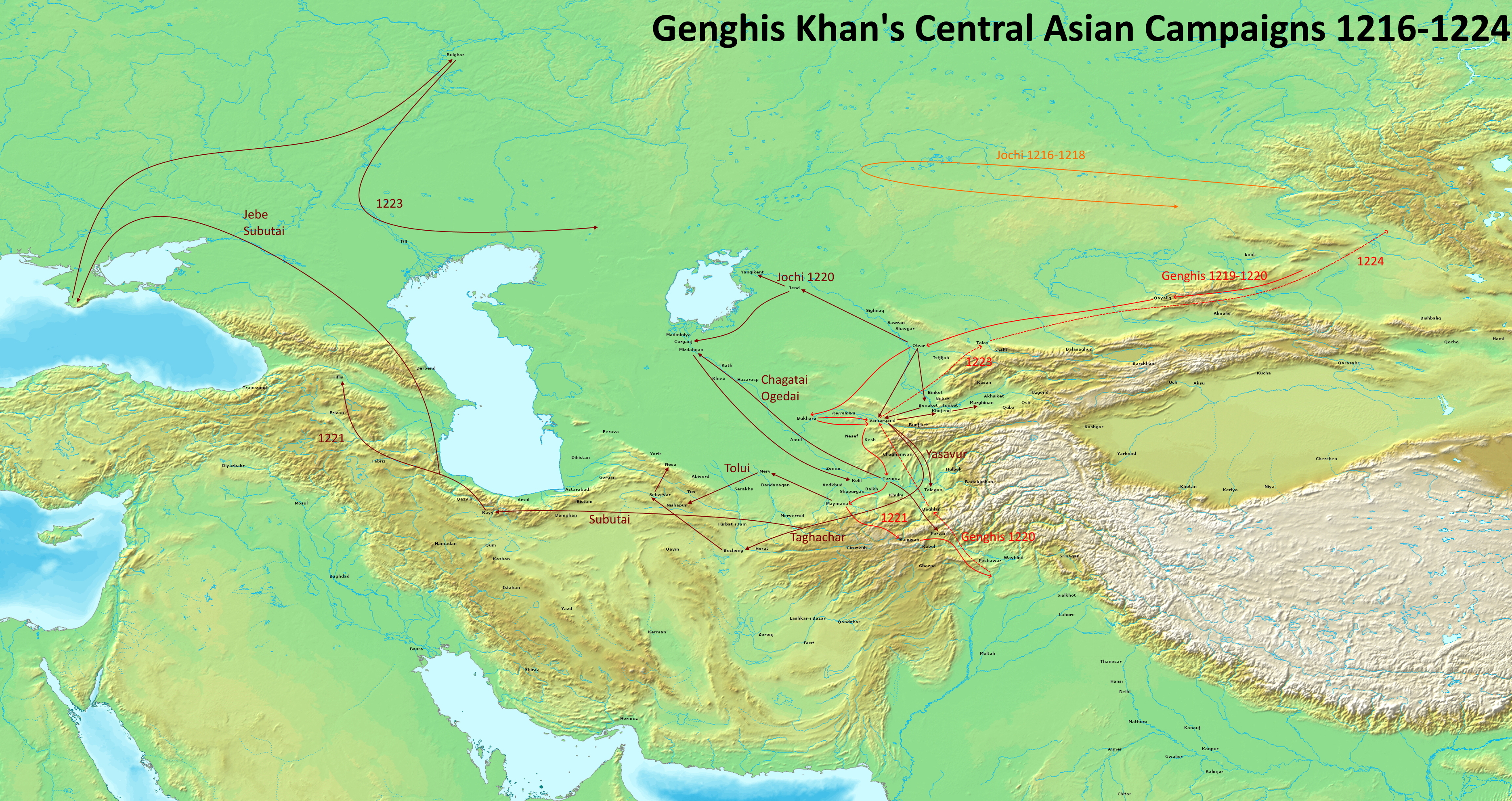

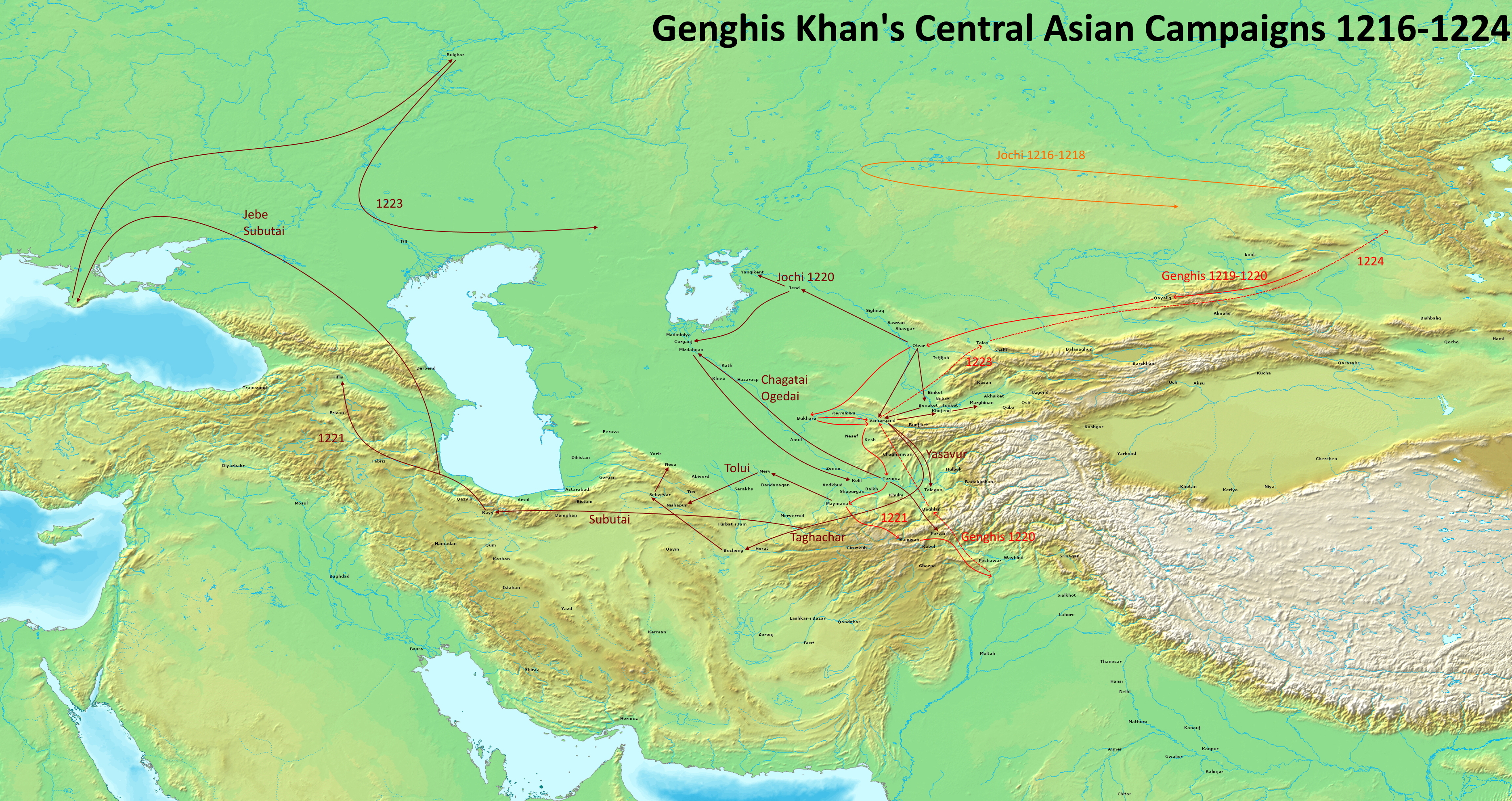

Map of Events

mentioned in this article. {{DEFAULTSORT:Mongol Invasion Of Khwarezmia Expeditionary warfare Military history of Uzbekistan 13th-century Islam Khwarazmian Empire Conflicts in 1219 Conflicts in 1220 Conflicts in 1221 13th century in Iran 1219 in the Mongol Empire 1220 in the Mongol Empire 1221 in the Mongol Empire Invasions of Iran Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire

Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

and Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

in the nearby region of Khorāsān, gaining enough power to declare himself a fully-fledged sovereign in 1189. Allying with the Abbasid caliph

The Abbasid caliphs were the holders of the Islamic title of caliph who were members of the Abbasid dynasty, a branch of the Quraysh tribe descended from the uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib.

The family came ...

Al-Nasir

Abu'l-Abbas Ahmad ibn al-Hassan al-Mustadi' ( ar, أبو العباس أحمد بن الحسن المستضيء) better known by his laqab Al-Nasir li-Din Allah ( ar, الناصر لدين الله; 6 August 1158 – 5 October 1225) or simply as A ...

, he overthrew the last Seljuk emperor, Toghrul III, in 1194, and usurped the sultanate of Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

. Tekish now ruled a great swathe of territory stretching from Hamadan in the west to Nishapur in the east; drawing on his newfound strength, he threatened war with the Caliph, who reluctantly accepted him as Sultan of Iran and Khorasan in 1198. The rapid expansion of what was now the Khwarezmian Empire greatly destabilized the Qara-Khitai, which was nominally the overlord. In the early thirteenth century, the khanate would be destabilized further by refugees fleeing the conquests of Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr /> Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin ...

, who had begun to establish hegemony over the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

.

Muhammad II became Khwarazmshah after his father Tekish died in 1200. Despite a troubled early start to his reign, which saw conflict with the Ghurids of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

, he followed his predecessor's expansionist policies by subjugating the Qarakhanids and taking their cities, including Bukhara. In 1211, Kuchlug

Kuchlug (also spelled ''Küchlüg'', ''Küçlüg'', ''Güčülüg'', ''Quqluq'') ( mn, Хүчлүг; ; d. 1218) was a member of the Naiman tribe who became the last ruler of the Western Liao dynasty (Qara Khitai). The Naimans were defeated by Gen ...

, a prince of the Naimans

The Naiman ( Mongolian: Найман, Naiman, "eight"; ; Kazakh: Найман, Naiman; Uzbek: Nayman) were a medieval tribe originating in the territory of modern Western Mongolia (possibly during the time of the Uyghur Khaganate), and are one of ...

, managed to usurp the Qara-Khitai empire from his father-in-law Yelü Zhilugu with Muhammad's help, but alienated both his subjects and the Khwarazmshah with anti-Muslim measures. As a Mongol detachment led by Jebe hunted him down, Kuchlug fled; meanwhile, Muhammad was able to vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. ...

ize the territories of Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastl ...

and Makran

Makran ( fa, مكران), mentioned in some sources as Mecran and Mokrān, is the coastal region of Baluchistan. It is a semi-desert coastal strip in Balochistan, in Pakistan and Iran, along the coast of the Gulf of Oman. It extends westwards, f ...

in modern-day Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

, and to gain the allegiance of the Eldiguzids

The Ildegizids, EldiguzidsC.E. Bosworth, "Ildenizids or Eldiguzids", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Edited by P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs et al., Encyclopædia of Islam, 2nd Edition., 12 vols. with index ...

.

Following the defeat of Kuchlug, their shared enemy, relations between the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

and the Khwarazmids were initially strong; however, the Shah soon grew apprehensive regarding his new eastern enemy. The chronicler al-Nasawi attributes this change in attitude to the memory of an unintended earlier encounter with Mongol troops, whose speed and mobility frightened the Shah. It is also likely that the Shah had grown in pride — like his father, he was now embroiled in a dispute with the Caliph An-Nasir, and even went so far as to march on Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

with an army, but was repulsed by a blizzard in the Zagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains ( ar, جبال زاغروس, translit=Jibal Zaghrus; fa, کوههای زاگرس, Kuh hā-ye Zāgros; ku, چیاکانی زاگرۆس, translit=Çiyakani Zagros; Turkish: ''Zagros Dağları''; Luri: ''Kuh hā-ye Zāgro ...

. Some historians have speculated that the Caliph tried to ally with Genghis Khan, especially after Mongol-Khwarazmid relations deteriorated. Mongol historians are adamant that the Genghis at that time had no intention of invading the Khwarazmian Empire, and were only interested in trade and even a potential alliance. They cite the fact he was already bogged down in his war against the Jin in China, and that he had to deal with the ''Hoi-yin Irgen'' rebellion in Siberia in 1216.

In 1218, the Khan sent a large caravan of Mongol merchants to Khwarazmia; it seems probable that a large proportion of the Mongol elite had invested in the expedition, and thus had a personal interest in its success. However, Inalchuq Inalchuq (or Inalchuk) (died 1219) was governor of Otrar in the Khwarezmian Empire in the early 13th century, known mainly for helping to provoke the successful and catastrophic invasion of Khwarezmia by Genghis Khan.

Inalchuq was an uncle of S ...

, the governor of the Khwarazmian city of Otrar, seized the caravan's goods and executed its members on charges of espionage. The validity of the accusations has been debated, as has the Shah's involvement; it is certain, though, that he rejected the Khan's subsequent demands that Inalchuq be punished, going so far as to kill one Mongol envoy and humiliate the other two. This was seen as a grave affront to the Khan himself, who considered ambassadors "as sacred and inviolable" as the Great Khan himself. He abandoned his war against the Jin, leaving only a small army to pursue it, and gathered as many men as possible to invade Khwarazmia.

Opposing forces

The precise sizes of each force have been heavily disputed; the one certainty is that the Mongol army numbered more than the Shah's. The medieval chronicler Rashid al-Din attested that the Mongol army numbered over 600,000 strong, and that they were opposed by 400,000 total Khwarazmians; his contemporary Juzjani gives an even greater estimate of 800,000 for the Khan. These numbers are regarded as greatly inflated by modern historians; the only contemporary source regarded as near-reliable is ''The Secret History of the Mongols

''The Secret History of the Mongols'' (Middle Mongol: ''Mongɣol‑un niɣuca tobciyan''; Traditional Mongolian: , Khalkha Mongolian: , ; ) is the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language. It was written for the Mongol royal fa ...

'', which gives totals of between 100,000 and 135,000 for the Mongol army, although these totals may have been deflated by a pro-Mongol chronicler.

While Stubbs and Rossabi indicate that the total Mongol invasion force cannot have been more than 200,000, Sverdrup, who hypothesizes that a tumen had often been overestimated in size, gives a minimum figure of 75,000. Most historians have given figures between these two extremes: McLynn estimates the Mongol force at around 120,000; while Smith follows the ''Secret History'' with a figure of 130,000. The uncertainty is made worse by the high flexibility and efficiency of the Mongol force's operational structure, allowing it to separate and coalesce at will. As for the Khwarazmians, there is no similarly reliable contemporary source; Sverdrup, taking the proportional exaggeration of the Muslim forces as equal to that of the Mongols, has estimated a total of around 40,000 soldiers, excluding certain town militias. Mclynn however provides a much greater figure of 200,000.

Dispositions

The Khwarazmshah faced many problems. His empire was vast and newly formed, with a still-developing administration. It is known that in 1218 he had overhauled the Seljuk-era administration, replacing it with a streamlined, loyal bureaucracy; the ongoing change may have contributed to disorder during the Mongol invasion. In addition, his mother Terken Khatun still wielded substantial power in the realm - one historian termed the relationship between the Shah and his mother as 'an uneasy diarchy', which often acted to Muhammad's disadvantage. Additionally, many of the areas that Muhammad charged his troops to defend had been devastated recently by Khwarazmian forces; when later passing through Nishapur, he urged the citizens to repair the fortifications his father had broken down, while Bukhara had been sacked by Muhammed only eight years earlier, in 1212. The Shah also distrusted most of his commanders, with the only exception being his eldest son and heir Jalal al-Din, whose military acumen had been critical on the Irghiz River the previous year. If he had sought open battle, as many of his commanders wished, he would certainly have been greatly outmatched in quantity of troops, let alone quality. The Shah thus made the decision to distribute his forces as garrison troops inside his most important towns, such as Samarkand,Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

and Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

.

Genghis' army was commanded by his most able generals, with the exception of Muqali

Muqali ( mn, Мухулай; 1170–1223), also spelt Mukhali and Mukhulai, was a Mongol general ("bo'ol", "one who is bound" in service) who became a trusted and esteemed commander under Genghis Khan. The son of Gü'ün U'a, a Jalair leader who ...

, who was left behind to continue the war against the Jin. Genghis also brought a large body of Chinese siege and construction experts, including several Chinese who were familiar with gunpowder. Historians have suggested that the Mongol invasion had brought Chinese gunpowder weapons, such as the huochong, to Central Asia.

Campaign

Early movements

Though they technically bordered each other, the Mongol and Khwarezm Empires touched far away from the homeland of each nation. In between them was a series of treacherous mountain ranges that the invader would have to cross. This aspect is often overlooked in this campaign, yet it was a critical reason why the Mongols were able to create a dominating position. The Khwarezm Shah and his advisers assumed that the Mongols would invade through the Dzungarian Gate, the natural mountain pass in between their (now conquered) Khara-Khitai and Khwarezm Empires. One option for the Khwarezm defence was to advance beyond the towns of the Syr Darya and block the Dzungarian Gate with an army, since it would take Genghis many months to gather his army in Mongolia and advance through the pass after winter had passed. The Khwarezm decision makers believed they would have time to further refine their strategy, but the Khan had struck first.

Immediately when war was declared, Genghis sent orders for a force already out to the west to immediately cross the Tien Shan mountains to the south and ravage the fertile

Though they technically bordered each other, the Mongol and Khwarezm Empires touched far away from the homeland of each nation. In between them was a series of treacherous mountain ranges that the invader would have to cross. This aspect is often overlooked in this campaign, yet it was a critical reason why the Mongols were able to create a dominating position. The Khwarezm Shah and his advisers assumed that the Mongols would invade through the Dzungarian Gate, the natural mountain pass in between their (now conquered) Khara-Khitai and Khwarezm Empires. One option for the Khwarezm defence was to advance beyond the towns of the Syr Darya and block the Dzungarian Gate with an army, since it would take Genghis many months to gather his army in Mongolia and advance through the pass after winter had passed. The Khwarezm decision makers believed they would have time to further refine their strategy, but the Khan had struck first.

Immediately when war was declared, Genghis sent orders for a force already out to the west to immediately cross the Tien Shan mountains to the south and ravage the fertile Fergana Valley

The Fergana Valley (; ; ) in Central Asia lies mainly in eastern Uzbekistan, but also extends into southern Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan.

Divided into three republics of the former Soviet Union, the valley is ethnically diverse and in the ...

in the eastern part of the Khwarezm Empire. This smaller detachment, no more than 20,000–30,000 men, was led by Genghis's son Jochi

Jochi Khan ( Mongolian: mn, Зүчи, ; kk, Жошы, Joşy جوشى; ; crh, Cuçi, Джучи, جوچى; also spelled Juchi; Djochi, and Jöchi c. 1182– February 1227) was a Mongol army commander who was the eldest son of Temüjin (aka G ...

and his elite general Jebe. The Tien Shan mountain passes were much more treacherous than the Dzungarian Gate, and to make it worse, they attempted the crossing in the middle of winter with over 5 feet of snow. Though the Mongols suffered losses and were exhausted from the crossing, their presence in the Ferghana Valley stunned the Khwarezm leadership and permanently stole the initiative away. This march can be described as the Central Asian equivalent of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps, with the same devastating effects. Because the Shah did not know if this Mongol army was a diversion or their main army, he had to protect one of his most fertile regions with force. Therefore, the Shah dispatched his elite cavalry reserve, which prevented him from effectively marching anywhere else with his main army. Jebe and Jochi seem to have kept their army in good shape while plundering the valley, and they avoided defeat by a much superior force. At this point the Mongols split up and again manoeuvred over the mountains: Jebe marched further south deeper into Khwarezm territory, while Jochi took most of the force northwest to attack the exposed cities on the Syr Darya from the east.

Meanwhile, another Mongol force under Chagatai and Ogedei descended onto Otrar from either the Altai Mountains to the north or the Dzungarian Gate and immediately started laying siege to it. Rashid Al-Din stated that Otrar had a garrison of 20,000 while Juvayni claimed 60,000 (horsemen and militia), though like the army figures given in most medieval chronicles, these numbers should be treated with caution and are probably exaggerated by an order of magnitude considering the size of the city. Genghis, who had marched through the Altai mountains, kept his main force further back near the mountain ranges, and stayed out of contact. Frank McLynn argues that this disposition can only be explained as Genghis laying a trap for the Shah. Because Shah decided to march his army up from Samarkand to attack the besiegers of Otrar, Genghis could then rapidly encircle the Shah's army from the rear. However, the Shah dodged the trap, and Genghis had to change plans.

Unlike most of the other cities, Otrar did not surrender after little fighting, nor did its governor march its army out into the field to be destroyed by the numerically superior Mongols. Instead the garrison remained on the walls and resisted stubbornly, holding out against many attacks. The siege proceeded for five months without results, until a traitor within the walls (Qaracha) who felt no loyalty to the Shah or Inalchuq opened the gates to the Mongols; the prince's forces managed to storm the now unsecured gate and slaughter the majority of the garrison. The citadel, holding the remaining one-tenth of the garrison, held out for another month, and was only taken after heavy Mongol casualties. Inalchuq Inalchuq (or Inalchuk) (died 1219) was governor of Otrar in the Khwarezmian Empire in the early 13th century, known mainly for helping to provoke the successful and catastrophic invasion of Khwarezmia by Genghis Khan.

Inalchuq was an uncle of S ...

held out until the end, even climbing to the top of the citadel in the last moments of the siege to throw down tiles at the oncoming Mongols and slay many of them in close quarters combat. Genghis killed many of the inhabitants, enslaved the rest, and executed Inalchuq.

Bukhara

At this point, the Mongol army was divided into five widely separated groups on opposite ends of the enemy Empire. After the Shah did not mount an active defence of the cities on the Syr Darya, Genghis and Tolui, at the head of an army of roughly 50,000 men, skirted the natural defence barrier of the Syr Darya and its fortified cities, and went westwards to lay siege to the city ofBukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

first. To do this, they traversed 300 miles of the seemingly impassable Kyzyl Kum desert by hopping through the various oases, guided most of the way by captured nomads. The Mongols arrived at the gates of Bukhara virtually unnoticed. Many military tacticians regard this surprise entrance to Bukhara as one of the most successful manoeuvres in warfare.

Bukhara was not heavily fortified, with a moat and a single wall, and the citadel typical of Khwarezmi cities. The Bukharan garrison was made up of Turkic soldiers and led by Turkic generals, who attempted to break out on the third day of the siege. Rashid Al-Din and Ibn Al-Athir state that the city had 20,000 defenders, though Carl Sverdrup contends that it only had a tenth of this number. A break-out force was annihilated in open battle. The city's leaders opened the gates to the Mongols, though a unit of Turkic defenders held the city's citadel for another twelve days. The Mongols valued artisans' skills highly and artisans were exempted from massacre during the conquests and instead entered into lifelong service as slaves. Thus, when the citadel was taken survivors were executed with the exception of artisans and craftsmen, who were sent back to Mongolia. Young men who had not fought were drafted into the Mongolian army and the rest of the population was sent into slavery. As the Mongol soldiers looted the city, a fire broke out, razing most of the city to the ground.

Samarkand

After the fall of Bukhara, Genghis headed to the Khwarezmian capital of Samarkand and arrived in March 1220. During this period, the Mongols also waged effective psychological warfare and caused divisions within their foe. The Khan's spies told them of the bitter fighting between the Shah and his mother Terken Khatun, who commanded the allegiance of some of his most senior commanders and his elite Turkish cavalry divisions. Since Mongols and Turks were both steppe peoples, Genghis argued that Terken Khatun and her army should join the Mongols against her treacherous son. Meanwhile, he arranged for deserters to bring letters that said Terken Khatun and some of her generals had allied with the Mongols. This further inflamed the existing divisions in the Khwarezm Empire, and probably prevented the senior commanders from unifying their forces. Genghis then compounded the damage by repeatedly issuing bogus decrees in the name of either Terken Khatun or Shah Mohammed, further tangling up the already divided Khwarezm command structure. As a result of the Mongol strategic initiative, speedy manoeuvres, and psychological strategies, all the Khwarezm generals, including the Queen Mother, kept their forces as a garrison and were defeated in turn. Samarkand possessed significantly better fortifications and a larger garrison compared to Bukhara. Juvayni and Rashid Al-Din (both writing under Mongol auspices) credit the defenders of the city with 100,000–110,000 men, while Ibn Al-Athir states 50,000. A more likely number is perhaps 10,000, considering the city itself had less than 100,000 people total at the time. As Genghis began his siege, his sons Chaghatai and Ögedei joined him after finishing the reduction of Otrar, and the joint Mongol forces launched an assault on the city. The Mongols attacked using prisoners as body shields. On the third day of fighting, the Samarkand garrison launched a counterattack. Feigning retreat, Genghis drew approximately half of the garrison outside the fortifications of Samarkand and slaughtered them in open combat. Shah Muhammad attempted to relieve the city twice, but was driven back. On the fifth day, all but a handful of soldiers surrendered. The remaining soldiers, die-hard supporters of the Shah, held out in the citadel. After the fortress fell, Genghis reneged on his surrender terms and executed every soldier who had taken arms against him at Samarkand. The people of Samarkand were ordered to evacuate and assemble in a plain outside the city, where many were killed. About the time of the fall of Samarkand, Genghis Khan chargedSubutai

Subutai ( Classical Mongolian: ''Sübügätäi'' or ''Sübü'ätäi''; Modern Mongolian: Сүбээдэй, ''Sübeedei''. ; ; c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He directed ...

and Jebe, two of the Khan's top generals, with hunting down the Shah. The Shah had fled west with some of his most loyal soldiers and his son, Jalal al-Din, to a small island in the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad s ...

. It was there, in December 1220, that the Shah died. Most scholars attribute his death to pneumonia, but others cite the sudden shock of the loss of his empire.

Gurganj

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Gurganj was still in the hands of Khwarezmian forces. Previously, the Shah's mother had ruled Gurganj, but she fled when she learned her son had absconded to the Caspian Sea. She was captured and sent to Mongolia.

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Gurganj was still in the hands of Khwarezmian forces. Previously, the Shah's mother had ruled Gurganj, but she fled when she learned her son had absconded to the Caspian Sea. She was captured and sent to Mongolia. Khumar Tegin

Khumarinskoye gorodishche (Russian: Хумаринское городище) or Khumar is a ruined medieval fortress on the top of Mount Kalezh above the Kuban Gorge in the Greater Caucasus, near Khumara village, Karachaevsky district, Karachay ...

, one of Muhammad's generals, declared himself Sultan of Gurganj. Jochi, who had been on campaign in the north since the invasion, approached the city from that direction, while Genghis, Ögedei, and Chaghatai attacked from the south.

The assault on Gurganj proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. The city was built along the river

The assault on Gurganj proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. The city was built along the river Amu Darya

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin name or Greek ) is a major river in Central Asi ...

in a marshy delta area. The soft ground did not lend itself to siege warfare, and there was a lack of large stones for the catapults. The Mongols attacked regardless, and the city fell only after the defenders put up a stout defence, fighting block for block. Mongolian casualties were higher than normal, due to the unaccustomed difficulty of adapting Mongolian tactics to city fighting.

The taking of Gurganj was further complicated by continuing tensions between the Khan and his eldest son, Jochi, who had been promised the city as his prize. Jochi's mother was the same as his three brothers': Genghis Khan's teen bride, and apparent lifelong love, Börte. Only her sons were counted as Genghis's "official" sons and successors, rather than those conceived by the Khan's 500 or so other "wives and consorts". But Jochi had been conceived in controversy; in the early days of the Khan's rise to power, Börte was captured and raped while she was held prisoner. Jochi was born nine months later. While Genghis Khan chose to acknowledge him as his oldest son (primarily due to his love for Börte, whom he would have had to reject had he rejected her child), questions had always existed over Jochi's true parentage.Nicolle, David. ''The Mongol Warlords''

Such tensions were present as Jochi engaged in negotiations with the defenders, trying to get them to surrender so that as much of the city as possible was undamaged. This angered Chaghatai, and Genghis headed off this fight between siblings by appointing Ögedei the commander of the besieging forces as Gurganj fell. But the removal of Jochi from command, and the sack of a city he considered promised to him, enraged him and estranged him from his father and brothers, and is credited with being a decisive impetus for the later actions of a man who saw his younger brothers promoted over him, despite his own considerable military skills.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar

Such tensions were present as Jochi engaged in negotiations with the defenders, trying to get them to surrender so that as much of the city as possible was undamaged. This angered Chaghatai, and Genghis headed off this fight between siblings by appointing Ögedei the commander of the besieging forces as Gurganj fell. But the removal of Jochi from command, and the sack of a city he considered promised to him, enraged him and estranged him from his father and brothers, and is credited with being a decisive impetus for the later actions of a man who saw his younger brothers promoted over him, despite his own considerable military skills.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar Juvayni Juvayni ( fa, جوینی), also spelled in English as Juwayni, Juvaini, or Joveini, is a Persian last name, meaning from the city of Juvayn in Khorasan, Iran. In the historical context, it may refer to these persons:

* Al-Juwayni (c. 1028–1085) ...

states that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were given the task of executing twenty-four Gurganj citizens each, which would mean that 1.2 million people were killed. While this is almost certainly an exaggeration, the sacking of Gurganj is considered one of the bloodiest massacres in human history.

Then came the complete destruction of the city of Gurganj, south of the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea ( ; kk, Арал теңізі, Aral teñızı; uz, Орол денгизи, Orol dengizi; kaa, Арал теңизи, Aral teńizi; russian: Аральское море, Aral'skoye more) was an endorheic lake lying between Kazakh ...

. Upon its surrender the Mongols broke the dams and flooded the city, then proceeded to execute the survivors.

Khorasan

As the Mongols battered their way into Urgench, Genghis dispatched his youngest sonTolui

Tolui (also Toluy, Tului; , meaning: "the mirror"; – 1232) was a Mongol khan, the fourth son of Genghis Khan by his chief khatun, Börte. At his father's death in 1227, his '' ulus'', or territorial inheritance, was the Mongol homelands on ...

, at the head of an army, into the western Khwarezmid province of Khorasan. Khorasan had already felt the strength of Mongol arms. Earlier in the war, the generals Jebe and Subutai had travelled through the province while hunting down the fleeing Shah. However, the region was far from subjugated, many major cities remained free of Mongol rule, and the region was rife with rebellion against the few Mongol forces present in the region, following rumours that the Shah's son Jalal al-Din was gathering an army to fight the Mongols.

Tolui's army consisted of somewhere around 50,000 men, which was composed of a core of Mongol soldiers (some estimates place it at 7,000), supplemented by a large body of foreign soldiers, such as Turks and previously conquered peoples in China and Mongolia. The army also included "3,000 machines flinging heavy incendiary arrows, 300 catapults, 700 mangonels to discharge pots filled with naphtha

Naphtha ( or ) is a flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

Mixtures labelled ''naphtha'' have been produced from natural gas condensates, petroleum distillates, and the distillation of coal tar and peat. In different industries and regions ...

, 4,000 storming-ladders, and 2,500 sacks of earth for filling up moats". Among the first cities to fall was Termez

Termez ( uz, Termiz/Термиз; fa, ترمذ ''Termez, Tirmiz''; ar, ترمذ ''Tirmidh''; russian: Термез; Ancient Greek: ''Tàrmita'', ''Thàrmis'', ) is the capital of Surxondaryo Region in southern Uzbekistan. Administratively, it is ...

then Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan

...

.

The major city to fall to Tolui's army was the city of Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

. Juvayni wrote of Merv: "In extent of territory it excelled among the lands of Khorasan, and the bird of peace and security flew over its confines. The number of its chief men rivaled the drops of April rain, and its earth contended with the heavens." The garrison at Merv was only about 12,000 men, and the city was inundated with refugees from eastern Khwarezmia. For six days, Tolui besieged the city, and on the seventh day, he assaulted the city. However, the garrison beat back the assault and launched their own counter-attack against the Mongols. The garrison force was similarly forced back into the city. The next day, the city's governor surrendered the city on Tolui's promise that the lives of the citizens would be spared. As soon as the city was handed over, however, Tolui slaughtered almost every person who surrendered, in a massacre possibly on a greater scale than that at Urgench.

After finishing off Merv, Tolui headed westwards, attacking the cities of Nishapur

Nishapur or officially Romanized as Neyshabur ( fa, ;Or also "نیشاپور" which is closer to its original and historic meaning though it is less commonly used by modern native Persian speakers. In Persian poetry, the name of this city is w ...

and Herat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Saf ...

. Nishapur fell after only three days; here, Tokuchar, a son-in-law of Genghis was killed in battle, and Tolui

Tolui (also Toluy, Tului; , meaning: "the mirror"; – 1232) was a Mongol khan, the fourth son of Genghis Khan by his chief khatun, Börte. At his father's death in 1227, his '' ulus'', or territorial inheritance, was the Mongol homelands on ...

put to the sword every living thing in the city, including the cats and dogs, with Tokuchar's widow presiding over the slaughter. After Nishapur's fall, Herat surrendered without a fight and was spared.

Bamiyan

Bamyan or Bamyan Valley (); ( prs, بامیان) also spelled Bamiyan or Bamian is the capital of Bamyan Province in central Afghanistan. Its population of approximately 70,000 people makes it the largest city in Hazarajat. Bamyan is at an al ...

in the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Prov ...

was another scene of carnage during the Siege of Bamyan (1221)

The Mongol conquest of Khorasan took place in 1220-21, during the Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire. As the Khwarazmian Empire disintegrated after the capture of the large cities of Samarkand and Bukhara by the Mongol Empire, Shah Muhamm ...

, here stiff resistance resulted in the death of a grandson of Genghis. Next was the city of Toos. By spring 1221, the province of Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plate ...

was under complete Mongol rule. Leaving garrison forces behind him, Tolui headed back east to rejoin his father.

Jalal al-Din

After the Mongol campaign in Khorasan, the Shah's army was broken. Jalal al-Din, who took power after his father's death, began assembling the remnants of the Khwarezmid army in the south, in the area ofAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

. Genghis had dispatched forces to hunt down the gathering army under Jalal al-Din, and the two sides met in September 1221 at the town of Parwan. The engagement was a humiliating defeat for the Mongol forces. Enraged, Genghis headed south himself, and defeated Jalal al-Din on the Indus River. Jalal al-Din, defeated, fled to India. Genghis spent some time on the southern shore of the Indus searching for the new Shah, but failed to find him. The Khan returned northwards, content to leave the Shah in India.

Encouraged by Jalal al-Din's success against the Mongols, the Khwarazmians started an insurgency. Kush Tegin Pahlawan lead a revolt in Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

and seized it successfully. After recapturing Merv, Kush Tegin Pahlawan made a successful attack on Bukhara. People in Herat also rebelled and disposed the Mongol vassal leadership. An insurgency leader named Muhammad the Marghani twice attacked the camp Genghis Khan accommodated at Baghlan

Baghlan (Dari: بغلان ''Baġlān'') is a city in northern Afghanistan, in the eponymous province, Baghlan Province. It is located three miles east of the Kunduz River, 35 miles south of Khanabad, and about 500 metres above sea level in the ...

and returned with some loot. As a response, Genghis Khan sent a large army Ögedei Khan

Ögedei Khagan (also Ogodei;, Mongolian: ''Ögedei'', ''Ögüdei''; – 11 December 1241) was second khagan- emperor of the Mongol Empire. The third son of Genghis Khan, he continued the expansion of the empire that his father had begun.

...

back to Ghazni. Genghis Khan appointed Yelü Ahai to restore Mongol sovereignty order in Samarqand and Bukhara, Yelu Ahai managed to restore the order in the cities only in 1223. Shikhikhutug dealt with the revolt that dethroned the Pro-Mongol governance of Merv. The Mongol general Genghis Khan appointed to hunt down Jalal al-Din joined the latter's service and converted to Islam after several unsuccessful battles against him.

Aftermath

After the remaining centers of resistance were destroyed, Genghis returned to Mongolia, leaving Mongolian garrison troops behind. The destruction and absorption of the Khwarezmid Empire would prove to be a sign of things to come, for theIslamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

as well as for Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

.Morgan, David ''The Mongols''

The new territory proved to be an important stepping stone for the Mongol armies when they invaded Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

and Poland during the reign of Genghis' son Ögedei, and future campaigns brought Mongol armies to Hungary and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

. For the Islamic world, the destruction of Khwarezmia left Iraq, Turkey and Syria wide open. All three regions were eventually subjugated by future Khans.

The war with Khwarezmia also brought up the important question of succession. Genghis was not young when the war began, and he had four sons, all of whom were fierce warriors and each of them had their own loyal group of followers. Their sibling rivalry almost came to a head during the siege of Urgench, and Genghis was forced to rely on his third son, Ögedei, who ended the battle. Following the destruction of Urgench, Genghis officially selected Ögedei to be his successor, and he also ruled that future Khans would be the direct descendants of previous rulers. Despite Genghis's establishment of this practice, the four sons would eventually come to blows, and those blows revealed the instability of the Khanate that Genghis had created.

Jochi never forgave his father, and he essentially withdrew from future Mongol wars, he moved to the north, and he refused to come to his father when he was ordered to. Indeed, at the time of his death, the Khan was contemplating a march on his rebellious son. The bitterness that resulted from this event was transmitted to Jochi's sons, especially Batu and Berke Khan (of the

The war with Khwarezmia also brought up the important question of succession. Genghis was not young when the war began, and he had four sons, all of whom were fierce warriors and each of them had their own loyal group of followers. Their sibling rivalry almost came to a head during the siege of Urgench, and Genghis was forced to rely on his third son, Ögedei, who ended the battle. Following the destruction of Urgench, Genghis officially selected Ögedei to be his successor, and he also ruled that future Khans would be the direct descendants of previous rulers. Despite Genghis's establishment of this practice, the four sons would eventually come to blows, and those blows revealed the instability of the Khanate that Genghis had created.

Jochi never forgave his father, and he essentially withdrew from future Mongol wars, he moved to the north, and he refused to come to his father when he was ordered to. Indeed, at the time of his death, the Khan was contemplating a march on his rebellious son. The bitterness that resulted from this event was transmitted to Jochi's sons, especially Batu and Berke Khan (of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragment ...

), who would conquer Kievan Rus

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

.Chambers, James. ''The Devil's Horsemen'' When the Mamluks of Egypt managed to inflict one of history's most significant defeats on the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut

The Battle of Ain Jalut (), also spelled Ayn Jalut, was fought between the Bahri Mamluks of Egypt and the Mongol Empire on 3 September 1260 (25 Ramadan 658 AH) in southeastern Galilee in the Jezreel Valley near what is known today as the Sp ...

in 1260, Hulagu Khan

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Хүлэгү/ , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mongol ruler who conquered much of West ...

, one of Genghis Khan's grandsons by his son Tolui

Tolui (also Toluy, Tului; , meaning: "the mirror"; – 1232) was a Mongol khan, the fourth son of Genghis Khan by his chief khatun, Börte. At his father's death in 1227, his '' ulus'', or territorial inheritance, was the Mongol homelands on ...

, who had sacked Baghdad in 1258, was unable to avenge that defeat when Berke Khan, his cousin, (who had converted to Islam) attacked him in the Transcaucasus in order to aid the cause of Islam, and Mongol battled Mongol for the first time. The seeds of that battle began in the conflict with Khwarezmia when their fathers struggled for supremacy.

See also

*Feigned retreat

A feigned retreat is a military tactic, a type of feint, whereby a military force pretends to withdraw or to have been routed, in order to lure an enemy into a position of vulnerability.

A feigned retreat is one of the more difficult tactics for ...

(battle of Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

, 1250)

References

Citations

Sources

* Chambers, James. ''The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe'', Atheneum, 1979. () * Morgan, David. ''The Mongols'', 1986. () * Nicolle, David. ''The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane'', Brockhampton Press, 1998. () * Saunders, J.J. ''The History of the Mongol Conquests'', Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1971. ()External links

*Map of Events

mentioned in this article. {{DEFAULTSORT:Mongol Invasion Of Khwarezmia Expeditionary warfare Military history of Uzbekistan 13th-century Islam Khwarazmian Empire Conflicts in 1219 Conflicts in 1220 Conflicts in 1221 13th century in Iran 1219 in the Mongol Empire 1220 in the Mongol Empire 1221 in the Mongol Empire Invasions of Iran Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire