Mississippi Civil Rights Workers' Murders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, also known as the Freedom Summer murders, the Mississippi civil rights workers' murders, or the Mississippi Burning murders, refers to events in which three activists were abducted and murdered in the city of

Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff

Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff

The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers.

Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had

The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers.

Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had

After the victims had been shot, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction. Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An

After the victims had been shot, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction. Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An

After reluctance from

After reluctance from

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive The disappearance of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner captured national attention. By the end of the first week, all major news networks were covering their disappearances.

by Fredric Danne ''New Yorker Magazine'' December 16, 1996 The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story. Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist

242

and

371

with conspiring to deprive the three activists of their civil rights (by murder). They indicted Sheriff Rainey, Deputy Sheriff Price and 16 other men. A U. S. Commissioner dismissed the charges six days later, declaring that the confession on which the arrests were based was hearsay. One month later, government attorneys secured indictments against the conspirators from a federal grand jury in Jackson. On February 24, 1965, however, Federal Judge

For much of the next four decades, no legal action was taken regarding the murders. In 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, the U.S. Congress passed a non-binding resolution honoring the three men; Senator

For much of the next four decades, no legal action was taken regarding the murders. In 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, the U.S. Congress passed a non-binding resolution honoring the three men; Senator

*A stone memorial at the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church commemorates the three civil rights activists.

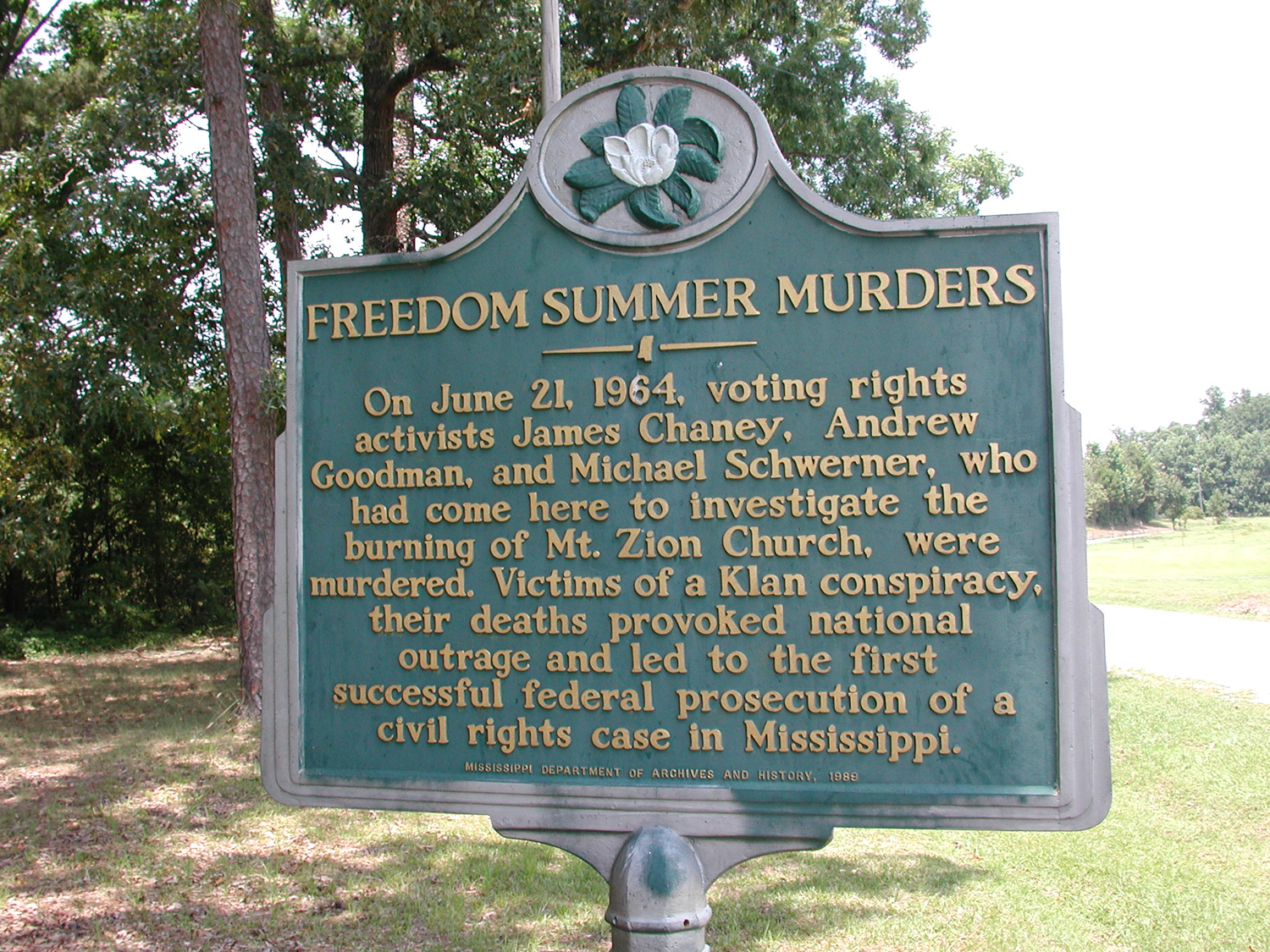

*Several Mississippi State Historical Markers have been erected relating to this incident:

**''Freedom Summer Murders'' (1989), near Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Neshoba County

**''Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner Murder Site'' (2008, later vandalized and rededicated in 2013), at the intersection of MS 19 and County Road 515

**''Old Neshoba County Jail'' (2012), at the site where the trio were held, on the north side of East Myrtle Street, between Byrd and Center Avenues

*A stone memorial at the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church commemorates the three civil rights activists.

*Several Mississippi State Historical Markers have been erected relating to this incident:

**''Freedom Summer Murders'' (1989), near Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Neshoba County

**''Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner Murder Site'' (2008, later vandalized and rededicated in 2013), at the intersection of MS 19 and County Road 515

**''Old Neshoba County Jail'' (2012), at the site where the trio were held, on the north side of East Myrtle Street, between Byrd and Center Avenues

plaque

on the Queens College website. *New York City named "Freedom Place", a four-block stretch in Manhattan's Upper West Side, in honor of Chaney, Goodman, and Shwerner. A plaque on 70th Street and Freedom Place (Riverside Drive) briefly tells their story. The plaque was re-located in 1999 to the garden of Hostelling International New York. Mrs. Goodman wanted the plaque to be in a place visited by young people. *A stained glass window depicting the three was placed in

The "Mississippi Burning" Civil Rights Murder Conspiracy Trial: A Headline Court Case

', by Harvey Fireside. Enslow Publishers. 2002. *''The Mississippi Burning Trial: A Primary Source Account'', by Bill Scheppler. The Rosen Publishing Group. 2003. *''Three Lives for Mississippi'', by William Bradford Huie. University Press of Mississippi, 1965. *"Untold Story of the Mississippi Murders", by William Bradford Huie, ''Saturday Evening Post'' September 5, 1964, No. 30, pp 11–15 *''We Are Not Afraid'', by Seth Cagin and Philip Dray. Bantam Books. 1988. *

Witness in Philadelphia

', by Florence Mars. Louisiana State University Press. 1977.

"The Mississippi Burning Trial"

by

"After Over Four Decades, Justice Still Eludes Family"

– video report by ''

FBI file on the case

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner 1964 in Mississippi 1964 murders in the United States Civil rights movement Deaths by firearm in Mississippi Jewish-American lynching victims June 1964 events in the United States Ku Klux Klan crimes in Mississippi Lynching deaths in Mississippi Murder in Mississippi Neshoba County, Mississippi Police brutality in the United States Political violence in the United States Racially motivated violence in the United States Terrorist incidents in the United States in 1964 Trios

Philadelphia, Mississippi

Philadelphia is a city in and the county seat of Neshoba County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,118 at the 2020 census.

History

Philadelphia is incorporated as a municipality; it was given its current name in 1903, two year ...

, in June 1964 during the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. The victims were James Chaney

James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman an ...

from Meridian, Mississippi

Meridian is the List of municipalities in Mississippi, seventh largest city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, with a population of 41,148 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and an estimated population in 2018 of 36,347. It is the count ...

, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964), was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers killed in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Schwerner and two co-workers, James Chan ...

from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. All three were associated with the Council of Federated Organizations

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was a coalition of the major Civil Rights Movement organizations operating in Mississippi. COFO was formed in 1961 to coordinate and unite voter registration and other civil rights activities in the sta ...

(COFO) and its member organization, the Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission ...

(CORE). They had been working with the Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. ...

campaign by attempting to register African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

in Mississippi to vote. Since 1890 and through the turn of the century, southern states had systematically disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

most black voters by discrimination in voter registration and voting.

The three men had traveled from Meridian to the community of Longdale to talk with congregation members at a black church that had been burned; the church had been a center of community organization. The trio was arrested following a traffic stop for speeding outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, escorted to the local jail, and held for a number of hours. As the three left town in their car, they were followed by law enforcement and others. Before leaving Neshoba County, their car was pulled over. The three were abducted, driven to another location, and shot to death at close range. The bodies of the three men were taken to an earthen dam where they were buried.

The disappearance of the three men was initially investigated as a missing person

A missing person is a person who has disappeared and whose status as alive or dead cannot be confirmed as their location and condition are unknown.

A person may go missing through a voluntary disappearance, or else due to an accident, crime, de ...

s case. The civil rights workers' burnt-out car was found near a swamp three days after their disappearance. An extensive search of the area was conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI), local and state authorities, and four hundred United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

sailors. Their bodies were not discovered until seven weeks later, when the team received a tip. During the investigation it emerged that members of the local White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Ku Klux Klan organization which is active in the United States. It originated in Mississippi and Louisiana in the early 1960s under the leadership of Samuel Bowers, its first Imperial Wizard. The White Kn ...

, the Neshoba County Sheriff's Office, and the Philadelphia Police Department were involved in the incident.

The murder of the activists sparked national outrage and an extensive federal investigation, filed as ''Mississippi Burning'' (MIBURN), which later became the title of a 1988 film loosely based on the events. In 1967, after the state government refused to prosecute, the United States federal government charged eighteen individuals with civil rights violations. Seven were convicted and received relatively minor sentences for their actions. Outrage over the activists' disappearances helped gain passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

.

The trio were shot and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan because Chaney was African-American and Goodman and Schwerner were both Jewish.

Forty-one years after the murders took place, one perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the ...

, was charged by the state of Mississippi for his part in the crimes. In 2005 he was convicted of three counts of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

and was given a 60-year sentence. On June 20, 2016, federal and state authorities officially closed the case, ending the possibility of further prosecution. Killen died in prison in January 2018.

Background

In the early 1960s, the state ofMississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, as well as other local and state governments in the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, defied federal direction regarding racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity ...

. Recent Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

rulings had upset the Mississippi establishment, and White Mississippian society responded with open hostility. White supremacists

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

used tactics such as bombings, murders, vandalism

Vandalism is the action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.

The term includes property damage, such as graffiti and defacement directed towards any property without permission of the owner. The term f ...

, and intimidation

Intimidation is to "make timid or make fearful"; or to induce fear. This includes intentional behaviors of forcing another person to experience general discomfort such as humiliation, embarrassment, inferiority, limited freedom, etc and the victi ...

in order to discourage black Mississippians and their supporters from the Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

and Western states

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

. In 1961, Freedom Riders

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions ''Morgan v. Virginia' ...

, who challenged the segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

of interstate buses and related facilities, were attacked on their route. In September 1962, the University of Mississippi riots had occurred in order to prevent James Meredith

James Howard Meredith (born June 25, 1933) is an American civil rights activist, writer, political adviser, and Air Force veteran who became, in 1962, the first African-American student admitted to the racially segregated University of Mississ ...

from enrolling at the school.

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Ku Klux Klan organization which is active in the United States. It originated in Mississippi and Louisiana in the early 1960s under the leadership of Samuel Bowers, its first Imperial Wizard. The White Kn ...

, a Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

splinter group

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

based in Mississippi, was founded and led by Samuel Bowers

Samuel Holloway Bowers (August 25, 1924 – November 5, 2006) was a convicted murderer and a leading white supremacist in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He was Grand Dragon of the Mississippi Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, ...

of Laurel

Laurel may refer to:

Plants

* Lauraceae, the laurel family

* Laurel (plant), including a list of trees and plants known as laurel

People

* Laurel (given name), people with the given name

* Laurel (surname), people with the surname

* Laurel (mus ...

. As the summer of 1964 approached, white Mississippians prepared for what they perceived was an invasion from the north and west. College students had been recruited in order to aid local activists who were conducting grassroots community organizing

Community organizing is a process where people who live in proximity to each other or share some common problem come together into an organization that acts in their shared self-interest.

Unlike those who promote more-consensual community bui ...

, voter registration

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The ru ...

education and drives in the state. Media reports exaggerated the number of youths expected. One Council of Federated Organizations

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was a coalition of the major Civil Rights Movement organizations operating in Mississippi. COFO was formed in 1961 to coordinate and unite voter registration and other civil rights activities in the sta ...

(COFO) representative is quoted as saying that nearly 30,000 individuals would visit Mississippi during the summer. Such reports had a "jarring impact" on white Mississippians and many responded by joining the White Knights.

In 1890, Mississippi had passed a new constitution, supported by additional laws, which effectively excluded most black Mississippians from registering or voting. This status quo had long been enforced by economic boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

s and violence. The Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission ...

(CORE) wanted to address this problem by setting up Freedom Schools Freedom Schools were temporary, alternative, and free schools for African Americans mostly in the South. They were originally part of a nationwide effort during the Civil Rights Movement to organize African Americans to achieve social, political and ...

and starting voting registration drives in the state. Freedom schools were established in order to educate, encourage, and register the disenfranchised black citizens. CORE members James Chaney, from Mississippi, and Michael Schwerner, from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, intended to set up a Freedom School for black people in Neshoba County

Neshoba County is located in the central part of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census, the population was 29,087. Its county seat is Philadelphia. It was named after ''Nashoba'', a Choctaw chief. His name means "wolf" in the ...

to try to prepare them to pass the comprehension and literacy tests required by the state.

Registering others to vote

OnMemorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

, May 25, 1964, Schwerner and Chaney spoke to the congregation at Mount Zion Methodist Church in Longdale, Mississippi about setting up a Freedom School. Schwerner implored the members to register to vote, saying, "you have been slaves too long, we can help you help yourselves". The White Knights learned of Schwerner's voting drive in Neshoba County and soon developed a plot to hinder the work and ultimately destroy their efforts. They wanted to lure CORE workers into Neshoba County, so they attacked congregation members and torched the church, burning it to the ground.

On June 21, 1964, Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner met at the Meridian COFO headquarters before traveling to Longdale to investigate the destruction of the Mount Zion Church. Schwerner told COFO Meridian to search for them if they were not back by 4 p.m.; he said, "if we're not back by then start trying to locate us."

Arrest

After visiting Longdale, the three civil rights workers decided not to take Road 491 to return to Meridian. The narrow country road was unpaved; abandoned buildings littered the roadside. They decided to head west onHighway 16

Route 16, or Highway 16, can refer to:

International

* Asian Highway 16

* European route E16

* European route E016

Australia

- Thompsons Road (Victoria)

- South Australia

Canada

;Parts of the Trans-Canada Highway:

*Yellowhead Hi ...

to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, the seat

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but also headquarters in a wider sense.

Types of seat

The following are examples of different kinds of seat:

* Armchair (furniture), ...

of Neshoba County, then take southbound Highway 19 to Meridian, figuring it would be the faster route. The time was approaching 3 p.m., and they were to be in Meridian by 4 p.m.

The CORE station wagon had barely passed the Philadelphia city limits when one of its tires went flat, and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price turned on his dashboard-mounted red light and followed them. The trio stopped near the Beacon and Main Street fork. With a long radio antenna mounted to his patrol car, Price called for Officers Harry Jackson Wiggs and Earl Robert Poe of the Mississippi Highway Patrol

The Mississippi Highway Safety Patrol is the highway patrol and acting state police agency for the U.S. state of Mississippi, and has law enforcement jurisdiction over the majority of the state.

The Mississippi Highway Patrol specializes in the ...

. Chaney was arrested for driving 65 mph in a 35 mph zone; Goodman and Schwerner were held for investigation. They were taken to the Neshoba County jail on Myrtle Street, a block from the courthouse.

In the Meridian office, workers became alarmed when the 4 p.m. deadline passed without word from the three activists. By 4:45 p.m., they notified the COFO Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Q ...

office that the trio had not returned from Neshoba County. The CORE workers called area authorities but did not learn anything; the contacted offices said they had not seen the three civil rights workers.

The conspiracy

Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff

Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey

Lawrence Andrew Rainey (March 2, 1923 – November 8, 2002) was Sheriff of Neshoba County, Mississippi during the 1960s. He gained notoriety for allegedly being involved in the June 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Rainey was ...

, were later identified as parties to the conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

to murder Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner. Rainey denied he was ever a part of the conspiracy, but he was accused of ignoring the racially-motivated offenses committed in Neshoba County. At the time of the murders, the 41-year-old Rainey insisted he was visiting his sick wife in a Meridian hospital and was later with family watching ''Bonanza

''Bonanza'' is an American Western television series that ran on NBC from September 13, 1959, to January 16, 1973. Lasting 14 seasons and 432 episodes, ''Bonanza'' is NBC's longest-running western, the second-longest-running western series on U ...

''. As events unfolded, Rainey became emboldened with his newly found popularity in the Philadelphia community. Known for his tobacco chewing habit, Rainey was photographed and quoted in ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine: "Hey, let's have some Red Man

America's Best Chew (formerly Red Man) is an American brand of chewing tobacco which was first introduced in 1904.arraignment

Arraignment is a formal reading of a criminal charging document in the presence of the defendant, to inform them of the charges against them. In response to arraignment, the accused is expected to enter a plea. Acceptable pleas vary among jurisd ...

to start.

Fifty-year-old Bernard Akin had a mobile home

A mobile home (also known as a house trailer, park home, trailer, or trailer home) is a prefabricated structure, built in a factory on a permanently attached chassis before being transported to site (either by being towed or on a trailer). Us ...

business which he operated out of Meridian; he was a member of the White Knights. Seventy one-year-old Other N. Burkes, who usually went by the nickname of Otha, was a 25-year veteran of the Philadelphia Police. At the time of the December 1964 arraignment, Burkes was awaiting an indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a legal person, person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felony, felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concep ...

for a different civil rights case. Olen L. Burrage, who was 34 at the time, owned a trucking company. Burrage was developing a cattle farm which he called the Old Jolly Farm, where the three civil rights workers were found buried. Burrage, a former U.S. Marine

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through com ...

who was honorably discharged, was quoted as saying: "I got a dam big enough to hold a hundred of them." Several weeks after the murders, Burrage told the FBI: "I want people to know I'm sorry it happened." Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the ...

, a 39-year-old Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

preacher and sawmill owner, was convicted decades later of orchestrating the murders.

Frank J. Herndon, 46, operated a Meridian drive-in

A drive-in is a facility (such as a restaurant or movie theater) where one can drive in with an automobile for service. At a drive-in restaurant, for example, customers park their vehicles and are usually served by staff who walk or rollerskat ...

called the Longhorn; he was the Exalted Grand Cyclops of the Meridian White Knights. James T. Harris, also known as Pete, was a White Knights investigator. The 30-year-old Harris was keeping tabs on the three civil rights workers' every move. Oliver R. Warner, 54, known as Pops, was a Meridian grocery owner and member of the White Knights. Herman Tucker lived in Hope, Mississippi, a few miles from the Neshoba County Fair

The Neshoba County Fair, also known as Mississippi's Giant House Party, is an annual event of agricultural, political, and social entertainment held a few miles from Philadelphia, Mississippi. The fair was first established in 1889 and is the nat ...

grounds. Tucker, 36, was not a member of the White Knights; he was a building contractor who worked for Burrage. The White Knights gave Tucker the assignment of getting rid of the CORE station wagon driven by the workers. White Knights Imperial Wizard Samuel H. Bowers, who served with the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, was not apprehended on December 4, 1964, but he was implicated the following year. Bowers, then 39, was credited with saying: "This is a war between the Klan and the FBI. And in a war, there have to be some who suffer."

On Sunday, June 7, 1964, nearly 300 White Knights met near Raleigh, Mississippi

Raleigh is a town in, and the county seat of, Smith County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,462 at the 2010 census, making it the largest town in Smith County. Named for English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh, Raleigh has been home t ...

. Bowers addressed the White Knights about what he described as a "nigger-communist invasion of Mississippi" that he expected to take place in a few weeks, in what CORE had announced as Freedom Summer. The men listened as Bowers said: "This summer the enemy will launch his final push for victory in Mississippi", and, "there must be a secondary group of our members, standing back from the main area of conflict, armed and ready to move. It must be an extremely swift, extremely violent, hit-and-run group."

Although federal authorities believed many others took part in the Neshoba County lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

, only ten men were charged with the physical murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. One of these was Deputy Sheriff Price, 26, who played a crucial role in implementing the conspiracy. Before his friend Rainey was elected sheriff in 1963, Price worked as a salesman, fireman, and bouncer

A bouncer (also known as a doorman or door supervisor) is a type of security guard, employed at venues such as bars, nightclubs, cabaret clubs, stripclubs, casinos, hotels, billiard halls, restaurants, sporting events, schools, concerts, or m ...

. Price, who had no prior experience in local law enforcement, was the only person who witnessed the entire event. He arrested the three men, released them the night of the murders, and chased them down state Highway 19 toward Meridian, eventually re-capturing them at the intersection near House, Mississippi. Price and the other nine men escorted them north along Highway 19 to Rock Cut Road, where they forced a stop and murdered the three civil rights workers.

Killen went to Meridian earlier that Sunday to organize and recruit men for the job to be carried out in Neshoba County. Before the men left for Philadelphia, Travis M. Barnette, 36, went to his Meridian home to take care of a sick family member. Barnette owned a Meridian garage and was a member of the White Knights. Alton W. Roberts, 26, was a dishonorably discharged

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

U.S. Marine who worked as a salesman in Meridian. Roberts, standing and weighing , was physically formidable and renowned for his short temper. According to witnesses, Roberts shot both Goodman and Schwerner at point blank range, then shot Chaney in the head after another accomplice, James Jordan, shot him in the abdomen. Roberts asked, "Are you that nigger lover?" to Schwerner, and shot him after the latter responded, "Sir, I know just how you feel." Jimmy K. Arledge, 27, and Jimmy Snowden, 31, were both Meridian commercial drivers. Arledge, a high school drop-out, and Snowden, a U.S. Army veteran, were present during the murders.

Jerry M. Sharpe, Billy W. Posey, and Jimmy L. Townsend were all from Philadelphia. Sharpe, 21, ran a pulp wood supply house. Posey, 28, a Williamsville automobile mechanic, owned a 1958 red and white Chevrolet; the car was considered fast and was chosen over Sharpe's. The youngest was Townsend, 17; he left high school in 1964 to work at Posey's Phillips 66

The Phillips 66 Company is an American Multinational corporation, multinational energy company headquartered in Westchase, Houston, Westchase, Houston, Houston, Texas. Its name, dating back to 1927 as a trademark of the Phillips Petroleum Compan ...

garage. Horace D. Barnette, 25, was Travis' younger half-brother; he had a 1957 two-toned blue Ford Fairlane sedan. Horace's car is the one the group took after Posey's car broke down. Officials say that James Jordan, 38, killed Chaney. He confessed his crimes to the federal authorities in exchange for a plea deal

A plea bargain (also plea agreement or plea deal) is an agreement in criminal law proceedings, whereby the prosecutor provides a concession to the defendant in exchange for a plea of guilt or ''nolo contendere.'' This may mean that the defendant ...

.

Murders

After Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner's release from the Neshoba County jail shortly after 10 p.m. on June 21, they were followed almost immediately by Deputy Sheriff Price in his 1957 white Chevrolet sedan patrol car. Soon afterward, the civil rights workers left the city limits located along Hospital Road and headed south on Highway 19. The workers arrived at Pilgrim's store, where they might have been inclined to stop and use the telephone, but the presence of a Mississippi Highway Patrol car, manned by Officers Wiggs and Poe, most likely dissuaded them. They continued south toward Meridian. The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers.

Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had

The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers.

Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had carburetor

A carburetor (also spelled carburettor) is a device used by an internal combustion engine to control and mix air and fuel entering the engine. The primary method of adding fuel to the intake air is through the venturi tube in the main meteri ...

problems, and was forced to the side of the highway. Sharpe and Townsend were ordered to stay with Posey's car and service it. Roberts transferred to Barnette's car, joining Arledge, Jordan, Posey, and Snowden.

Price eventually caught the CORE station wagon heading west toward Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, on Road 492. Soon he stopped them and escorted the three civil right workers north on Highway 19, back in the direction of Philadelphia. The caravan turned west on County Road 515 (also known as Rock Cut Road), and stopped at the secluded intersection of County Road 515 and County Road 284 (). The three men were subsequently shot by Jordan and Roberts. Chaney was also beaten and castrated

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceut ...

before his death.

Disposing of the evidence

After the victims had been shot, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction. Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An

After the victims had been shot, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction. Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

of Goodman, showing fragments of red clay in his lungs and grasped in his fists, suggests he was probably buried alive alongside the already dead Chaney and Schwerner.

After all three were buried, Price told the group:

Eventually, Tucker was tasked with disposing of the CORE station wagon in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. For reasons unknown, the station wagon was left near a river in northeast Neshoba County along Highway 21. It was soon set ablaze and abandoned.

Investigation and public attention

After reluctance from

After reluctance from FBI Director

The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a United States' federal law enforcement agency, and is responsible for its day-to-day operations. The FBI Director is appointed for a single ...

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

to get directly involved, President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

convinced him by threatening to send ex-CIA director Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

in his stead. Hoover initially ordered the FBI Office in Meridian, run by John Proctor, to begin a preliminary search after the three men were reported missing. That evening, U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

escalated the search and ordered 150 federal agents to be sent from New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. Two local Native Americans found the smoldering car that evening; by the next morning, that information had been communicated to Proctor. Joseph Sullivan of the FBI immediately went to the scene. By the next day, the federal government had arranged for hundreds of sailors from the nearby Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Naval Air Station Meridian

Naval Air Station Meridian or NAS Meridian is a military airport located 11 miles northeast of Meridian, Mississippi in Lauderdale County and Kemper County, and is one of the Navy's two jet strike pilot training facilities.

History

On July 16, ...

to search the swamps of Bogue Chitto.

During the investigation, searchers including Navy divers and FBI agents discovered the bodies of Henry Hezekiah Dee

''Mississippi Cold Case'' is a 2007 feature documentary produced by David Ridgen of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about the Ku Klux Klan murders of two 19-year-old black men, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, in Southwest Mississ ...

and Charles Eddie Moore

''Mississippi Cold Case'' is a 2007 feature documentary produced by David Ridgen of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about the Ku Klux Klan murders of two 19-year-old black men, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, in Southwest Missis ...

in the area (the first was found by a fisherman). They were college students who had disappeared in May 1964. Federal searchers also discovered 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby, and the bodies of five other deceased African Americans who were never identified.Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner & Goodman~ Civil Rights Movement Archive The disappearance of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner captured national attention. By the end of the first week, all major news networks were covering their disappearances.

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

met with the parents of Goodman and Schwerner in the Oval Office

The Oval Office is the formal working space of the President of the United States. Part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, it is located in the West Wing of the White House, in Washington, D.C.

The oval-shaped room ...

. Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 – July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' for 19 years (1962–1981). During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the mo ...

's broadcast of the ''CBS Evening News

The ''CBS Evening News'' is the flagship evening television news program of CBS News, the news division of the CBS television network in the United States. The ''CBS Evening News'' is a daily evening broadcast featuring news reports, feature s ...

'' on June 25, 1964, called the disappearances "the focus of the whole country's concern". The FBI eventually offered a $25,000 reward (), which led to the breakthrough in the case. Meanwhile, Mississippi officials resented the outside attention. Sheriff Rainey said, "They're just hiding and trying to cause a lot of bad publicity for this part of the state." Mississippi Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr.

Paul Burney Johnson Jr. (January 23, 1916October 14, 1985) was an American attorney and Democratic politician from Mississippi, serving as governor from 1964 until January 1968. He was a son of former Mississippi Governor Paul B. Johnson Sr.

E ...

dismissed concerns, saying the young men "could be in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

".

The bodies of the CORE activists were found only after an informant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informan ...

(discussed in FBI reports only as "Mr. X") passed along a tip to federal authorities. They were discovered on August 4, 1964, 44 days after their murder, underneath an earthen dam on Burrage's farm. Schwerner and Goodman had each been shot once in the heart; Chaney, a black man, had been severely beaten, castrated and shot three times. The identity of "Mr. X" was revealed publicly forty years after the original events, and revealed to be Maynard King, a Mississippi Highway Patrol officer close to the head of the FBI investigation. King died in 1966.

In the summer of 1964, according to Linda Schiro and other sources, FBI field agents in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

recruited the mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Gregory Scarpa

Gregory Scarpa (May 8, 1928 – June 4, 1994) nicknamed the Grim Reaper and also the Mad Hatter, was an American caporegime and hitman for the Colombo crime family, as well as an informant for the FBI. During the 1970s and 80s, Scarpa was the ...

to help them find the missing civil rights workers. The FBI was convinced the three men had been murdered, but could not find their bodies. The agents thought that Scarpa, using illegal interrogation techniques not available to agents, might succeed at gaining this information from suspects. Once Scarpa arrived in Mississippi, local agents allegedly provided him with a gun and money to pay for information. Scarpa and an agent allegedly pistol-whipped

Pistol-whipping or buffaloing is the act of using a handgun as a blunt weapon, wielding it as an improvised club. Such a practice dates to the time of muzzle loaders, which were brandished in such fashion in close-quarters combat once the weapon ...

and kidnapped Lawrence Byrd, a TV salesman and secret Klansman

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, from his store in Laurel

Laurel may refer to:

Plants

* Lauraceae, the laurel family

* Laurel (plant), including a list of trees and plants known as laurel

People

* Laurel (given name), people with the given name

* Laurel (surname), people with the surname

* Laurel (mus ...

and took him to Camp Shelby

Camp Shelby is a military post whose North Gate is located at the southern boundary of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on United States Highway 49. It is the largest state-owned training site in the nation. During wartime, the camp's mission is to se ...

, a local Army base. At Shelby, Scarpa severely beat Byrd and stuck a gun barrel down his throat. Byrd finally revealed to Scarpa the location of the three men's bodies."The G-man and the Hit Man"by Fredric Danne ''New Yorker Magazine'' December 16, 1996 The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story. Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist

Jerry Mitchell

Jerry Mitchell is an American theatre director and choreographer.

Early life and education

Born in Paw Paw, Michigan, Mitchell later moved to St. Louis where he pursued his acting, dancing and directing career in theatre. Although he did not g ...

and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

high school teacher Barry Bradford claimed that Mississippi highway patrolman

"Highway Patrolman" is a song written and recorded by Bruce Springsteen and was first released as the fifth track on his 1982 album ''Nebraska''.

The song tells the story of Joe Roberts, the highway patrolman of the title from whose viewpoint t ...

Maynard King provided the grave locations to FBI agent Joseph Sullivan after obtaining the information from an anonymous third party. In January 1966, Scarpa allegedly helped the FBI a second time in Mississippi on the murder case of Vernon Dahmer

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer Sr. (March 10, 1908 – January 10, 1966) was an American civil rights movement leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was murdered by the White Knights of the ...

, killed in a fire set by the Klan. After this second trip, Scarpa and the FBI had a sharp disagreement about his reward for these services. The FBI then dropped Scarpa as a confidential informant.

In a famous eulogy

A eulogy (from , ''eulogia'', Classical Greek, ''eu'' for "well" or "true", ''logia'' for "words" or "text", together for "praise") is a speech or writing in praise of a person or persons, especially one who recently died or retired, or as a ...

for Chaney, CORE leader Dave Dennis voiced his rage, anguish, and turmoil:

President Johnson and civil rights activists used the outrage over the activists' deaths to gain passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, which Johnson signed on July 2. This and the Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the ...

of 1965 contributed to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

, which Johnson signed on August 6 of that year.

Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Is ...

used the delayed resolution of the case in his argument that the federal government was not protecting black lives, and African-Americans would have to defend themselves: "And the FBI head, Hoover, admits that they know who did it, they've known ever since it happened, and they've done nothing about it. Civil rights bill down the drain."

By late November 1964 the FBI accused 21 Mississippi men of engineering a conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Most of the suspects were apprehended by the FBI on December 4, 1964. The FBI detained the following individuals: B. Akin, E. Akin, Arledge, T. Barnette, Burkes, Burrage, Bowers, Harris, Herndon, Killen, Posey, Price, Rainey, Roberts, Sharpe, Snowden, Townsend, Tucker, and Warner. Two individuals who were not interviewed and photographed, H. Barnette and James Jordan, would later confess their roles during the murder.

Because Mississippi officials refused to prosecute the killers for murder, a state crime, the federal government, led by prosecutor John Doar

John Michael Doar (December 3, 1921 – November 11, 2014) was an American lawyer and senior counsel with the law firm Doar Rieck Kaley & Mack in New York City. During the administrations of presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he ...

, charged 18 individuals under 18 U.S.C. 242

and

371

with conspiring to deprive the three activists of their civil rights (by murder). They indicted Sheriff Rainey, Deputy Sheriff Price and 16 other men. A U. S. Commissioner dismissed the charges six days later, declaring that the confession on which the arrests were based was hearsay. One month later, government attorneys secured indictments against the conspirators from a federal grand jury in Jackson. On February 24, 1965, however, Federal Judge

William Harold Cox

William Harold Cox (June 23, 1901 – February 25, 1988) was an American attorney and jurist who served as a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi. H ...

, an ardent segregationist, threw out the indictments against all conspirators other than Rainey and Price on the ground that the other seventeen were not acting "under color of state law." In March 1966, the United States Supreme Court overruled Cox and reinstated the indictments. Defense attorneys then made the argument that the original indictments were flawed because the pool of jurors from which the grand jury was drawn contained insufficient numbers of minorities. Rather than attempt to refute the charge, the government summoned a new grand jury and, on February 28, 1967, won reindictments.

1967 federal trial

Trial in the case of ''United States v. Cecil Price, et al.'', began on October 7, 1967, in the Meridian courtroom of Judge William Harold Cox, the same judge known to be an opponent of the civil rights movement. A jury of seven white men and five white women was selected. Defense attorneys exercised peremptory challenges against all seventeen potential black jurors. A white man, who admitted under questioning by Robert Hauberg, the U.S. Attorney for Mississippi, that he had been a member of the KKK "a couple of years ago," was challenged for cause, but Cox denied the challenge. The trial was marked by frequent crises. Star prosecution witness James Jordan cracked under the pressure of anonymous death threats made against him and had to be hospitalized at one point. The jury deadlocked on its decision and Judge Cox employed the "Allen charge

''Allen v. United States'', 164 U.S. 492 (1896), was a United States Supreme Court case that, amongst other things, approved the use of a jury instruction intended to prevent a hung jury by encouraging jurors in the minority to reconsider. The C ...

" to bring them to resolution. Seven defendants, mostly from Lauderdale County, were convicted. The convictions in the case represented the first ever convictions in Mississippi for the killing of a civil rights worker.

Those found guilty on October 20, 1967, were Cecil Price, Klan Imperial Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The t ...

Samuel Bowers

Samuel Holloway Bowers (August 25, 1924 – November 5, 2006) was a convicted murderer and a leading white supremacist in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He was Grand Dragon of the Mississippi Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, ...

, Alton Wayne Roberts

Alton Wayne Roberts (April 6, 1938 – September 11, 1999) was a Klansman convicted of depriving slain activists Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney of their civil rights in 1964. He shot two of the three civil rights workers bef ...

, Jimmy Snowden

Jimmy Snowden (September 21, 1933 – July 7, 2008), of Lauderdale County, Mississippi, was a conspirator and participant in the notorious murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi in 1964. He was a member of the Whit ...

, Billy Wayne Posey, Horace Barnette, and Jimmy Arledge. Sentences ranged from three to ten years. After exhausting their appeals, the seven began serving their sentences in March 1970. None served more than six years. Sheriff Rainey was among those acquitted. Two of the defendants, E.G. Barnett, a candidate for sheriff, and Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the ...

, a local minister, had been strongly implicated in the murders by witnesses, but the jury came to a deadlock on their charges and the Federal prosecutor decided not to retry them. On May 7, 2000, the jury revealed that in the case of Killen, they deadlocked after a lone juror stated she "could never convict a preacher".

Further research and 2005 murder trial

Trent Lott

Chester Trent Lott Sr. (born October 9, 1941) is an American lawyer, author, and politician. A former United States Senator from Mississippi, Lott served in numerous leadership positions in both the United States House of Representatives and the ...

and the rest of the Mississippi delegation refused to vote for it.

The journalist Jerry Mitchell

Jerry Mitchell is an American theatre director and choreographer.

Early life and education

Born in Paw Paw, Michigan, Mitchell later moved to St. Louis where he pursued his acting, dancing and directing career in theatre. Although he did not g ...

, an award-winning investigative reporter for Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Q ...

's ''The Clarion-Ledger

''The Clarion Ledger'' is an American daily newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi. It is the second-oldest company in the state of Mississippi, and is one of the few newspapers in the nation that continues to circulate statewide. It is an operating d ...

'', wrote extensively about the case for six years. In the late 20th century, Mitchell had earned fame by his investigations that helped secure convictions in several other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the murders of Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served i ...

and Vernon Dahmer

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer Sr. (March 10, 1908 – January 10, 1966) was an American civil rights movement leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was murdered by the White Knights of the ...

, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a white supremacist terrorist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sunday, September 15, 1963. Four members of a local Ku Klux Klan chapter planted 19 sticks of dynam ...

in Birmingham.

In the case of the civil rights workers, Mitchell was aided in developing new evidence, finding new witnesses, and pressuring the state to take action by Barry Bradford, a high school teacher at Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Illinois, and three of his students, Allison Nichols, Sarah Siegel, and Brittany Saltiel. Bradford later achieved recognition for helping Mitchell clear the name of the civil rights martyr Clyde Kennard

Clyde Kennard (June 12, 1927July 4, 1963) was an American Korean War veteran and civil rights leader from Hattiesburg, Mississippi. In the 1950s, he attempted several times to enroll at the all-white Mississippi Southern College (now the Univers ...

.

Together the student-teacher team produced a documentary for the National History Day contest. It presented important new evidence and compelling reasons to reopen the case. Bradford also obtained an interview with Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the ...

, which helped convince the state to investigate. Partially by using evidence developed by Bradford, Mitchell was able to determine the identity of "Mr. X", the mystery informer who had helped the FBI discover the bodies and end the conspiracy of the Klan in 1964.

Mitchell's investigation and the high school students' work in creating Congressional pressure, national media attention and Bradford's taped conversation with Killen prompted action. In 2004, on the 40th anniversary of the murders, a multi-ethnic group of citizens in Philadelphia, Mississippi

Philadelphia is a city in and the county seat of Neshoba County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,118 at the 2020 census.

History

Philadelphia is incorporated as a municipality; it was given its current name in 1903, two year ...

, issued a call for justice. More than 1,500 people, including civil rights leaders and Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour

Haley Reeves Barbour (born October 22, 1947) is an American attorney, politician, and lobbyist who served as the 63rd governor of Mississippi from 2004 to 2012. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as chairman of the Republican ...

, joined them to support having the case re-opened.

On January 6, 2005, a Neshoba County grand jury indicted Edgar Ray Killen on three counts of murder. When the Mississippi Attorney General prosecuted the case, it was the first time the state had taken action against the perpetrators of the murders. Rita Bender, Michael Schwerner's widow, testified in the trial. On June 21, 2005, a jury convicted Killen on three counts of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

; he was described as the man who planned and directed the killing of the civil rights workers. Killen, then 80 years old, was sentenced to three consecutive terms of 20 years in prison. His appeal, in which he claimed that no jury of his peers would have convicted him in 1964 based on the evidence presented, was rejected by the Supreme Court of Mississippi

The Supreme Court of Mississippi is the highest court in the state of Mississippi. It was established in the first constitution of the state following its admission as a State of the Union in 1817 and was known as the High Court of Errors and Appe ...

in 2007.

On June 20, 2016, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood

James Matthew Hood (born May 15, 1962) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 39th Attorney General of Mississippi from 2004 to 2020.

A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he was first elected in 20 ...

and Vanita Gupta

Vanita Gupta (born November 15, 1974) is an American attorney who has served as United States Associate Attorney General since April 22, 2021. From 2014 to 2017, Gupta served as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division under Pres ...

, top prosecutor for the Civil Rights Division

The U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division is the institution within the federal government responsible for enforcing federal statutes prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, sex, disability, religion, and national origin. The ...

of the U.S. Justice Department

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

, announced that there would be no further investigation into the murders. "The evidence has been degraded by memory over time, and so there are no individuals that are living now that we can make a case on at this point," Hood said.

Legacy and honors

Individual

See: *James Chaney

James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman an ...

* Andrew Goodman

*Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964), was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers killed in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Schwerner and two co-workers, James Chan ...

National

*Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were posthumously awarded the 2014Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

by President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

.

Ohio

*Miami University

Miami University (informally Miami of Ohio or simply Miami) is a public research university in Oxford, Ohio. The university was founded in 1809, making it the second-oldest university in Ohio (behind Ohio University, founded in 1804) and the 10 ...

's now-defunct Western Program included historical lectures about Freedom Summer and the events of the massacre.

*There is a memorial on the Western campus of Miami University. It includes dozen of headlines about the murder, and plaques honoring and detailing the victims' life and work.

**Additionally, Miami's board of trustees voted unanimously in 2019 to name the lounges of 3 residence halls on the Western campus after Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

Michigan

*At Cedar Springs High School inCedar Springs, Michigan

Cedar Springs is a city in Kent County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 3,509 at the 2010 census. Cedar Springs is a northern city of the Grand Rapids metropolitan area and is about north of Grand Rapids.

History

The area wa ...

, an outdoor memorial theatre is dedicated to the Freedom Summer alums. The day of Goodman's murder is acknowledged each year on campus, and the clock tower of the campus library is dedicated to Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner.

Mississippi

*A stone memorial at the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church commemorates the three civil rights activists.

*Several Mississippi State Historical Markers have been erected relating to this incident:

**''Freedom Summer Murders'' (1989), near Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Neshoba County

**''Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner Murder Site'' (2008, later vandalized and rededicated in 2013), at the intersection of MS 19 and County Road 515

**''Old Neshoba County Jail'' (2012), at the site where the trio were held, on the north side of East Myrtle Street, between Byrd and Center Avenues

*A stone memorial at the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church commemorates the three civil rights activists.

*Several Mississippi State Historical Markers have been erected relating to this incident:

**''Freedom Summer Murders'' (1989), near Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Neshoba County

**''Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner Murder Site'' (2008, later vandalized and rededicated in 2013), at the intersection of MS 19 and County Road 515

**''Old Neshoba County Jail'' (2012), at the site where the trio were held, on the north side of East Myrtle Street, between Byrd and Center Avenues

New York

*The Chaney-Goodman-Schwerner Clock Tower of Queens College's Rosenthal Library was built in 1988 and dedicated in 1989. There is a photograph of thplaque

on the Queens College website. *New York City named "Freedom Place", a four-block stretch in Manhattan's Upper West Side, in honor of Chaney, Goodman, and Shwerner. A plaque on 70th Street and Freedom Place (Riverside Drive) briefly tells their story. The plaque was re-located in 1999 to the garden of Hostelling International New York. Mrs. Goodman wanted the plaque to be in a place visited by young people. *A stained glass window depicting the three was placed in

Sage Chapel

Sage Chapel is the non-denominational chapel on the campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York State which serves as the burial ground for many contributors to Cornell's history, including the founders of the university: Ezra Cornell and An ...

at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

in 1991. Schwerner was a Cornell graduate, as were Goodman's parents.

*In June 2014, Schwerner's hometown, Pelham, New York

Pelham is a suburban town in Westchester County, approximately 10 miles northeast of Midtown Manhattan. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 13,078, an increase from the 2010 census. Historically, Pelham was composed of five villages ...

, kicked off a year-long, town-wide commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner's deaths:

**On June 22, 2014, the Pelham Picture House __NOTOC__

The Picture House Regional Film Center, formerly known as the Pelham Picture House, is a historic movie theater located in Pelham, New York. The rectangular building was built in 1921, in the Spanish Revival style and is oriented at an a ...

held a free screening of the film ''Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. ...

'' ahead of the film's June 24 premiere on ''American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

'' on PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcasting, public broadcaster and Non-commercial activity, non-commercial, Terrestrial television, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly fu ...

. The screening was followed by a discussion and Q&A session with an expert panel.

**In November, close to Election Day

Election day or polling day is the day on which general elections are held. In many countries, general elections are always held on a Saturday or Sunday, to enable as many voters as possible to participate; while in other countries elections ar ...

and Schwerner's birthday, the Schwerner-Chaney-Goodman Memorial Commemoration Committee and the Pelham School District will host a multiple activities, such as a keynote speech by Nicholas Lemann

Nicholas Berthelot Lemann is an American writer and academic, the Joseph Pulitzer II and Edith Pulitzer Moore Professor of Journalism and Dean Emeritus of the Faculty of Journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He has be ...

(Dean Emeritus and Henry R. Luce professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York City).

**Also in autumn 2014, The Picture House Evening Film Club for students in grades 9 through 12 will show a film they are creating, on the theme "What price freedom", inspired by Schwerner's commitment and sacrifice.

Washington, D.C.

*The murders contributed to Congressional passage of theCivil Rights Act of 1964