Mineralization (biology) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

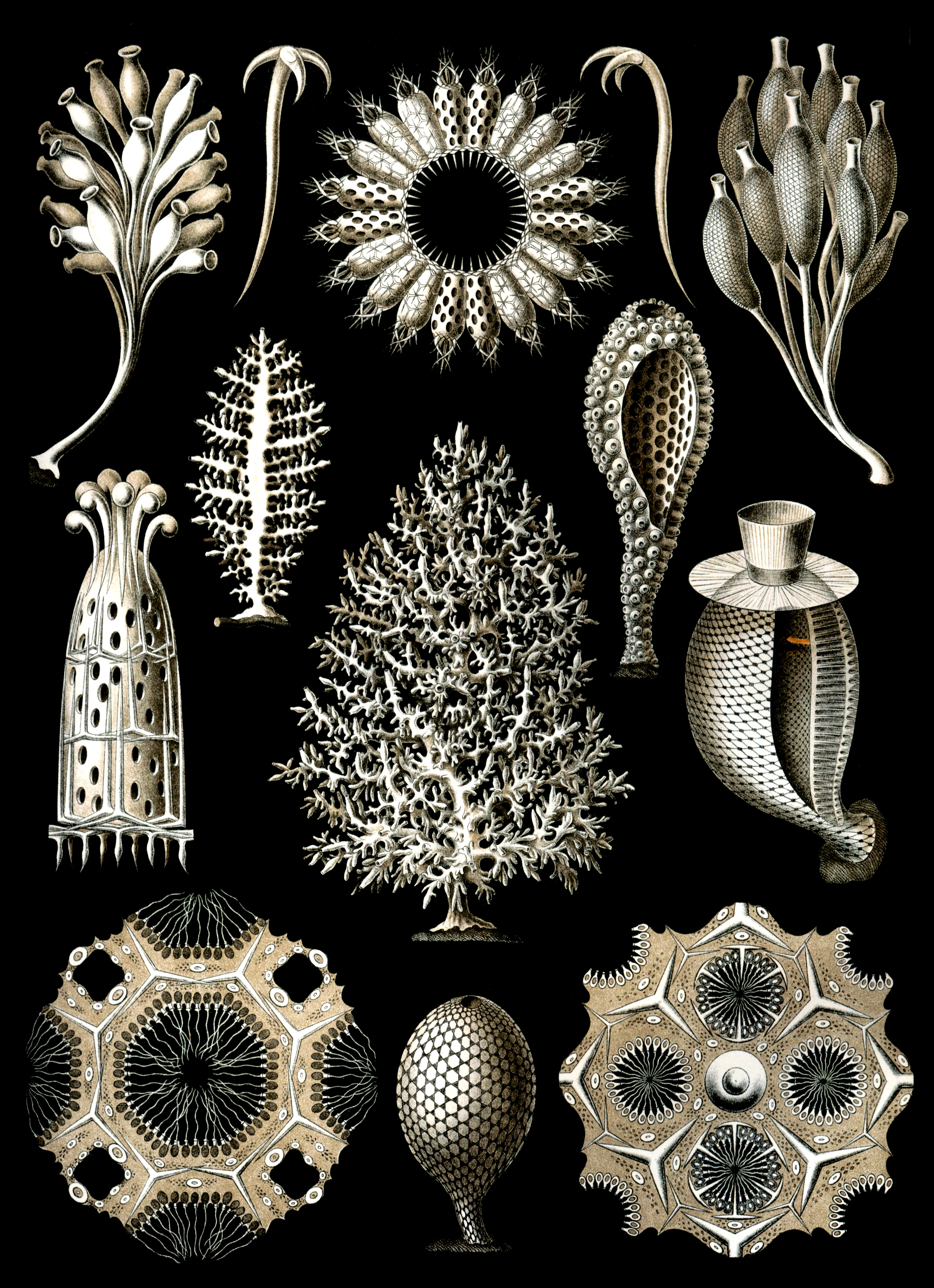

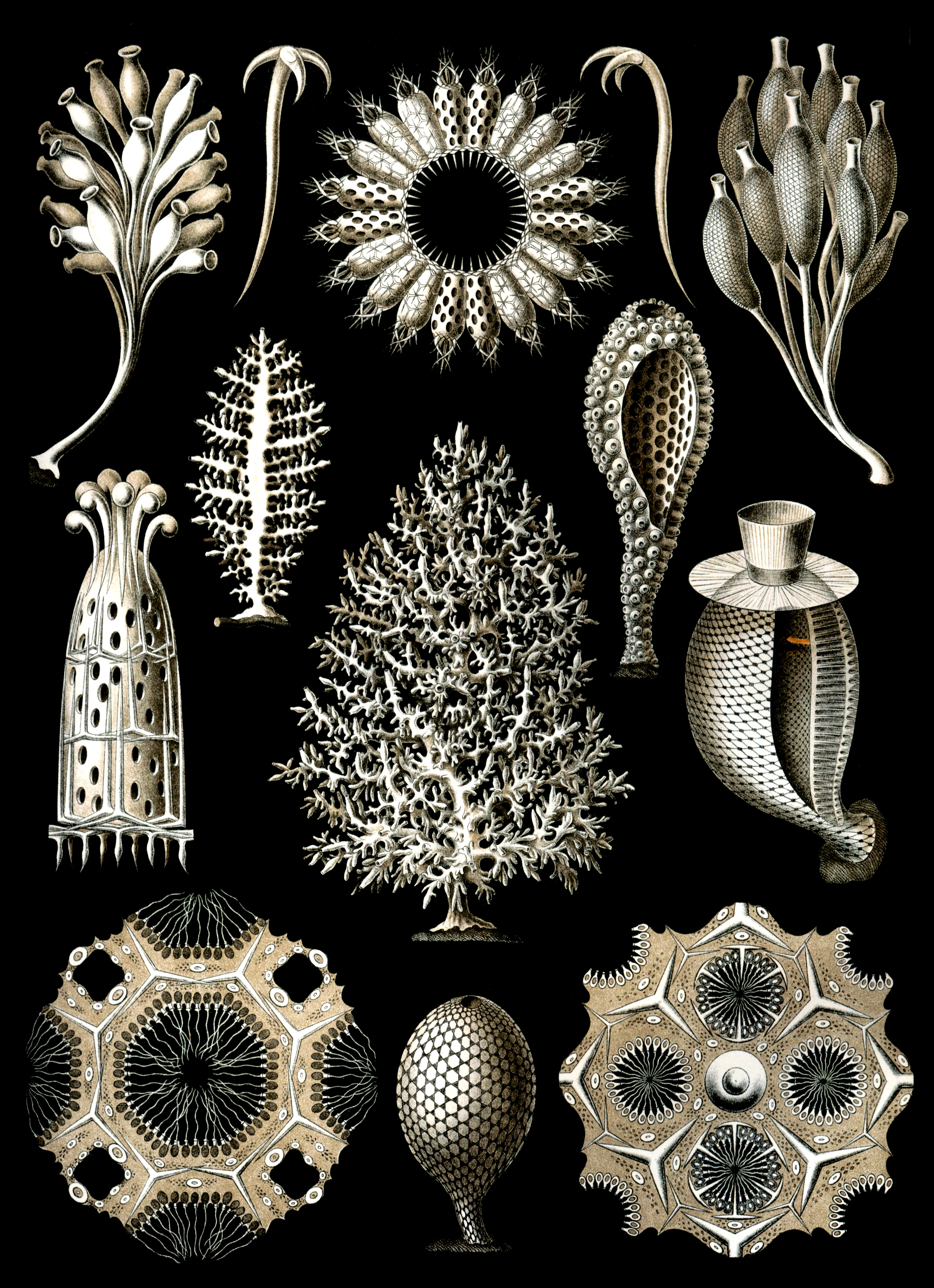

Biomineralization, also written biomineralisation, is the process by which living organisms produce minerals, often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues. It is an extremely widespread phenomenon; all six taxonomic kingdoms contain members that are able to form minerals, and over 60 different minerals have been identified in organisms. Examples include silicates in

Biomineralization, also written biomineralisation, is the process by which living organisms produce minerals, often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues. It is an extremely widespread phenomenon; all six taxonomic kingdoms contain members that are able to form minerals, and over 60 different minerals have been identified in organisms. Examples include silicates in

File:Braarudosphaera bigelowii.jpg, Many protists, like this coccolithophore, have protective mineralised shells

File:Foraminifères de Ngapali.jpg, Foraminifers from a beach

File:Lobster NSRW rotated.jpg, Many invertebrate animals have external exoskeletons or shells, which achieve rigidity by a variety of mineralisations

File:Elephant skeleton.jpg, Vertebrate animals have internal endoskeletons which achieve rigidity by binding calcium phosphate into hydroxylapatite

If present on a supracellular scale, biominerals are usually deposited by a dedicated organ, which is often defined very early in the embryological development. This organ will contain an organic matrix that facilitates and directs the deposition of crystals. The matrix may be collagen, as in

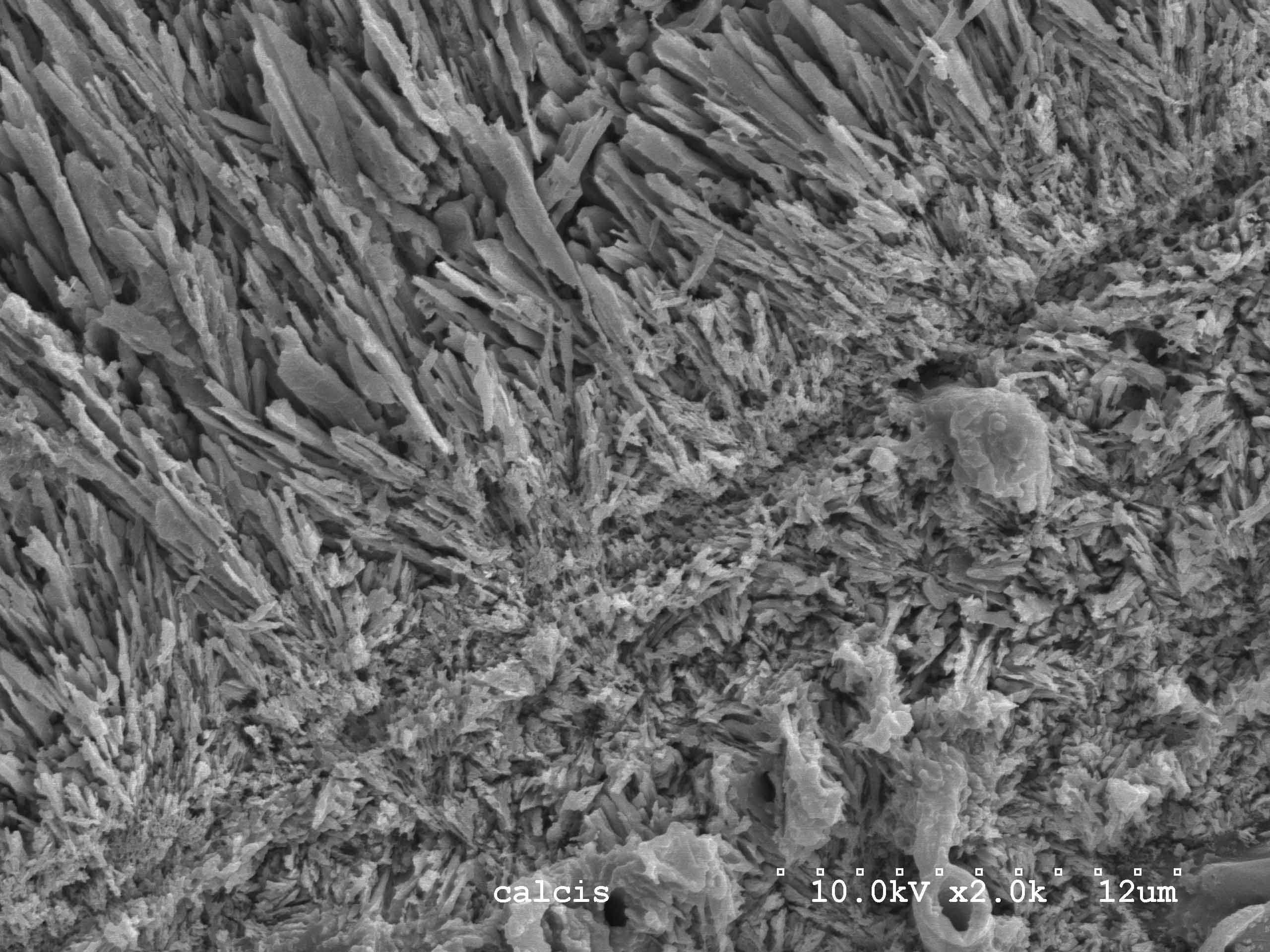

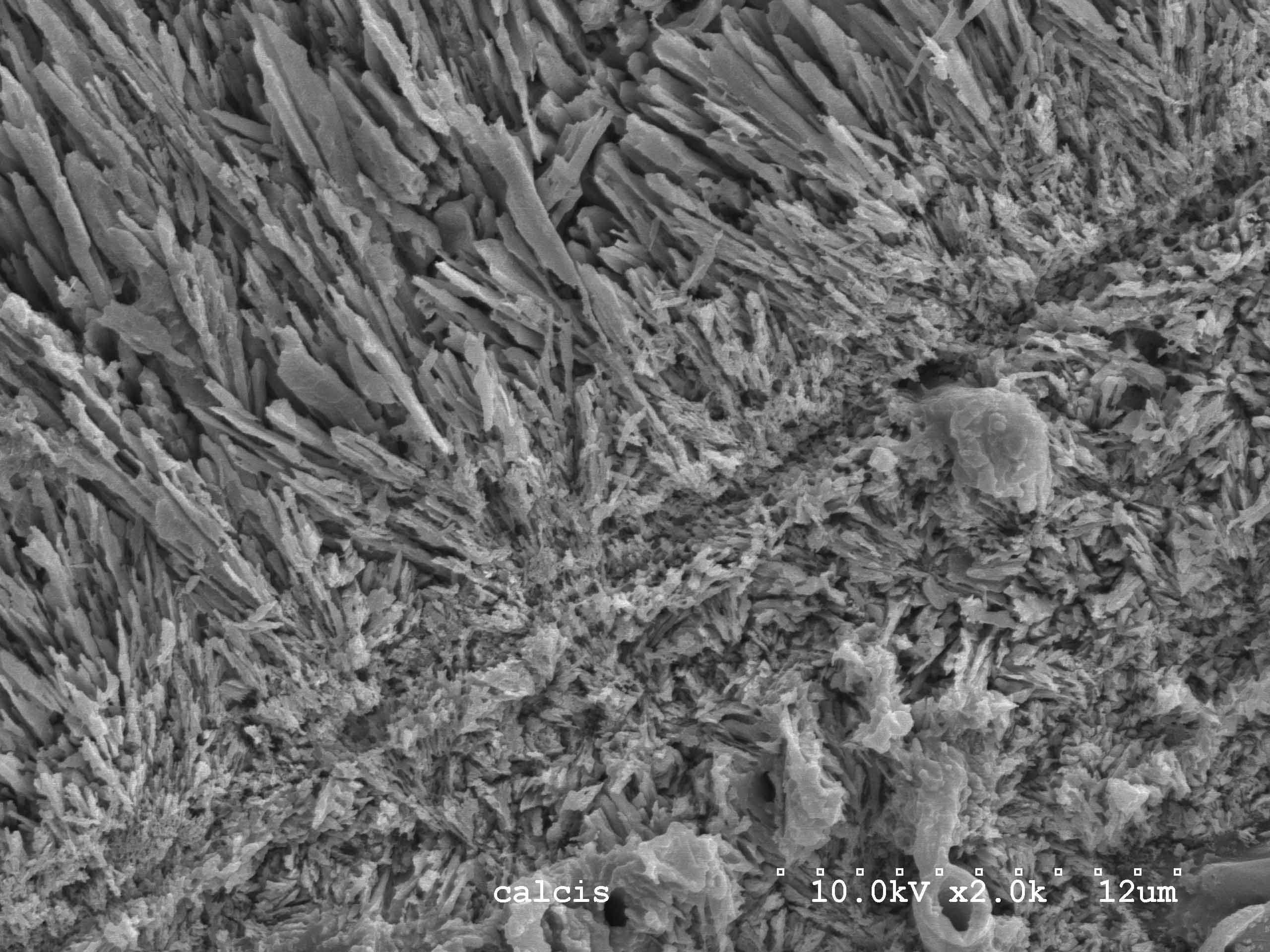

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves. In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties.

The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre, known in large shells such as '' Pinna'' or the pearl oyster ('' Pinctada''). Not only does the structure of the layers differ, but so do their mineralogy and chemical composition. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars and lipids), and the organic components are characteristic of the layer and of the species. The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is a crystalline calcium carbonate ( aragonite, calcite), though some amorphous calcium carbonate occurs as well; and although they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves. In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties.

The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre, known in large shells such as '' Pinna'' or the pearl oyster ('' Pinctada''). Not only does the structure of the layers differ, but so do their mineralogy and chemical composition. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars and lipids), and the organic components are characteristic of the layer and of the species. The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is a crystalline calcium carbonate ( aragonite, calcite), though some amorphous calcium carbonate occurs as well; and although they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.

Biomineralization plays significant global roles terraforming the planet, as well as in biogeochemical cycles and as a carbon sink.

Biomineralization plays significant global roles terraforming the planet, as well as in biogeochemical cycles and as a carbon sink.

File:Chitonidae - Chiton squamosus.JPG, Chitons have aragonite shells and aragonite-based eyes, as well as teeth coated with

File:Acantharia confocial micrograph 2.png, Acantharian radiolarians have celestine crystal shells

File:Celestine - Sakoany deposit, Katsepy, Mitsinjo, Boeny, Madagascar.jpg, Celestine crystals, the heaviest mineral in the oceans

Celestine, the heaviest mineral in the ocean, consists of strontium sulfate, SrSO4. The mineral is named for the delicate blue colour of its crystals. Planktic acantharean radiolarians form celestine crystal shells. The denseness of the celestite ensures their shells function as mineral ballast, resulting in fast sedimentation to bathypelagic depths. High settling fluxes of acantharian cysts have been observed at times in the Iceland Basin and the Southern Ocean, as much as half of the total gravitational organic carbon flux.  Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

File:Diversity of biomineralization across the eukaryotes.jpg, The phylogeny shown in this diagram is based on Adl et al. (2012), with major eukaryotic supergroups named in boxes. Letters next to taxon names denote the presence of biomineralization, with circled letters indicating prominent and widespread use of that biomineral. S, silica; C, calcium carbonate; P, calcium phosphate; I, iron (magnetite/goethite); X, calcium oxalate; SO4, sulfates (calcium/barium/strontium), ? denotes uncertainty in report.

There are questions which have yet to be resolved, such as why do some organisms biomineralize while others do not, and why is there such a diversity of biominerals besides silicon when silicon is so abundant, comprising 28% of the Earth's crust. The answer to these questions lies in the evolutionary interplay between biomineralization and geochemistry, and in the competitive interactions that have arisen from these dynamics. Fundamentally whether an organism produces silica or not involves evolutionary trade-offs and competition between silicifiers themselves, and with non-silicifying organisms (both those which utilize other biominerals, and non-mineralizing groups). Mathematical models and controlled experiments of resource competition in phytoplankton have demonstrated the rise to dominance of different algal species based on nutrient backgrounds in defined media. These have been part of fundamental studies in ecology. However, the vast diversity of organisms that thrive in a complex array of biotic and abiotic interactions in oceanic ecosystems are a challenge to such minimal models and experimental designs, whose parameterization and possible combinations, respectively, limit the interpretations that can be built on them.

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some , and sponge-grade organisms may have formed calcite skeletons . But in most lineages, biomineralization first occurred in the

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some , and sponge-grade organisms may have formed calcite skeletons . But in most lineages, biomineralization first occurred in the

File:SEM image of Bacillus megaterium.jpg, '' Bacillus megaterium''

File:Bacillus subtilis.jpg, ''

One biological system that might be of key importance in future development of architecture is the bacterial biofilm. The term biofilm refers to complex heterogeneous structures comprising different populations of microorganisms that attach and form a community on an inert (e.g. rocks, glass, plastic) or organic (e.g. skin, cuticle, mucosa) surfaces.

The properties of the surface, such as charge, hydrophobicity and roughness, determine initial bacterial attachment. A common principle of all biofilms is the production of

Biomineralization‐mediated scaffolding of bacterial biofilms.jpg, A directed growth of the calcium carbonate crystals allows mechanical support of the 3D structure. The bacterial  Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Material was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Bacterially induced calcium carbonate precipitation can be used to produce "self‐healing" concrete. '' Bacillus megaterium'' spores and suitable dried nutrients are mixed and applied to steel‐reinforced concrete. When the concrete cracks, water ingress dissolves the nutrients and the bacteria germinate triggering calcium carbonate precipitation, resealing the crack and protecting the steel reinforcement from corrosion. This process can also be used to manufacture new hard materials, such as bio‐cement.

However the full potential of bacteria‐driven biomineralization is yet to be realized, as it is currently used as a passive filling rather than as a smart designable material. A future challenge is to develop ways to control the timing and the location of mineral formation, as well as the physical properties of the mineral itself, by environmental input. ''

Autunite-69257.jpg,

Biomineralization may be used to remediate groundwater contaminated with uranium. The biomineralization of uranium primarily involves the precipitation of uranium phosphate minerals associated with the release of phosphate by microorganisms. Negatively charged ligands at the surface of the cells attract the positively charged uranyl ion (UO22+). If the concentrations of phosphate and UO22+ are sufficiently high, minerals such as autunite (Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2•10-12H2O) or polycrystalline HUO2PO4 may form thus reducing the mobility of UO22+. Compared to the direct addition of inorganic phosphate to contaminated groundwater, biomineralization has the advantage that the ligands produced by microbes will target uranium compounds more specifically rather than react actively with all aqueous metals. Stimulating bacterial phosphatase activity to liberate phosphate under controlled conditions limits the rate of bacterial hydrolysis of organophosphate and the release of phosphate to the system, thus avoiding clogging of the injection location with metal phosphate minerals. The high concentration of ligands near the cell surface also provides nucleation foci for precipitation, which leads to higher efficiency than chemical precipitation.

An overview of the bacteria involved in biomineralization from the Science Creative Quarterly

'Data and literature on modern and fossil Biominerals': http://biomineralisation.blogspot.fr

Minerals and the Origins of Life

( Robert Hazen,

Biomineralization web-book: bio-mineral.org

Special German Research Project About the Principles of Biomineralization

{{Portal bar, Astronomy, Biology, Evolutionary biology, Geology, Paleontology Pedology Physiology Bioinorganic chemistry Biological processes Skeletal system

Biomineralization, also written biomineralisation, is the process by which living organisms produce minerals, often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues. It is an extremely widespread phenomenon; all six taxonomic kingdoms contain members that are able to form minerals, and over 60 different minerals have been identified in organisms. Examples include silicates in

Biomineralization, also written biomineralisation, is the process by which living organisms produce minerals, often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues. It is an extremely widespread phenomenon; all six taxonomic kingdoms contain members that are able to form minerals, and over 60 different minerals have been identified in organisms. Examples include silicates in algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from ...

and diatoms, carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonat ...

s in invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

, and calcium phosphates

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are white ...

and carbonates in vertebrates. These minerals often form structural features such as sea shells and the bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, an ...

in mammals and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

. Organism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s have been producing mineralized skeletons for the past 550 million years. Calcium carbonates and calcium phosphates are usually crystalline, but silica organisms (sponges, diatoms...) are always non crystalline minerals. Other examples include copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

deposits involving bacteria. Biologically formed minerals often have special uses such as magnetic sensors in magnetotactic bacteria (Fe3O4), gravity-sensing devices (CaCO3, CaSO4, BaSO4) and iron storage and mobilization (Fe2O3•H2O in the protein ferritin).

In terms of taxonomic distribution, the most common biominerals are the phosphate and carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonat ...

salts of calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

that are used in conjunction with organic polymers such as collagen and chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

to give structural support to bones and shells. The structures of these biocomposite materials are highly controlled from the nanometer to the macroscopic level, resulting in complex architectures that provide multifunctional properties. Because this range of control over mineral growth is desirable for materials engineering applications, there is interest in understanding and elucidating the mechanisms of biologically-controlled biomineralization.

Types

Mineralization can be subdivided into different categories depending on the following: the organisms or processes that create chemical conditions necessary for mineral formation, the origin of the substrate at the site of mineral precipitation, and the degree of control that the substrate has on crystal morphology, composition, and growth. These subcategories include: biomineralization, organomineralization, and inorganic mineralization, which can be subdivided further. However, usage of these terms vary widely in scientific literature because there are no standardized definitions. The following definitions are based largely on a paper written by Dupraz et al. (2009), which provided a framework for differentiating these terms.Biomineralization

Biomineralization, biologically controlled mineralization, occurs when crystal morphology, growth, composition, and location is completely controlled by the cellular processes of a specific organism. Examples include the shells of invertebrates, such as molluscs and brachiopods. Additionally, mineralization of collagen provides the crucial compressive strength for the bones, cartilage, and teeth of vertebrates.Organomineralization

This type of mineralization includes both biologically induced mineralization and biologically influenced mineralization. * Biologically induced mineralization occurs when the metabolic activity of microbes (e.g.bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

) produces chemical conditions favorable for mineral formation. The substrate for mineral growth is the organic matrix, secreted by the microbial community, and affects crystal morphology and composition. Examples of this type of mineralization include calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an a ...

or siliceous stromatolites and other microbial mats. A more specific type of biologically induced mineralization, remote calcification or remote mineralization, takes place when calcifying microbes occupy a shell-secreting organism and alter the chemical environment surrounding the area of shell formation. The result is mineral formation not strongly controlled by the cellular processes of the animal host (i.e., remote mineralization); this may lead to unusual crystal morphologies.

* Biologically influenced mineralization takes place when chemical conditions surrounding the site of mineral formation are influenced by abiotic processes (e.g., evaporation or degassing). However, the organic matrix (secreted by microorganisms) is responsible for crystal morphology and composition. Examples include micro- to nanometer scale crystals of various morphologies.

Biological mineralization can also take place as a result of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ization. See also calcification.

Biological roles

Among animals, biominerals composed of calcium carbonate,calcium phosphate

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are wh ...

or silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is o ...

perform a variety of roles such as support, defense and feeding.

deuterostome

Deuterostomia (; in Greek) are animals typically characterized by their anus forming before their mouth during embryonic development. The group's sister clade is Protostomia, animals whose digestive tract development is more varied. Some exa ...

s, or based on chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

or other polysaccharides, as in molluscs.

In molluscs

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves. In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties.

The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre, known in large shells such as '' Pinna'' or the pearl oyster ('' Pinctada''). Not only does the structure of the layers differ, but so do their mineralogy and chemical composition. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars and lipids), and the organic components are characteristic of the layer and of the species. The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is a crystalline calcium carbonate ( aragonite, calcite), though some amorphous calcium carbonate occurs as well; and although they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves. In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties.

The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre, known in large shells such as '' Pinna'' or the pearl oyster ('' Pinctada''). Not only does the structure of the layers differ, but so do their mineralogy and chemical composition. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars and lipids), and the organic components are characteristic of the layer and of the species. The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is a crystalline calcium carbonate ( aragonite, calcite), though some amorphous calcium carbonate occurs as well; and although they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.

In fungi

Fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

are a diverse group of organisms that belong to the eukaryotic domain. Studies of their significant roles in geological processes, "geomycology", has shown that fungi are involved with biomineralization, biodegradation, and metal-fungal interactions.

In studying fungi's roles in biomineralization, it has been found that fungi deposit minerals with the help of an organic matrix, such as a protein, that provides a nucleation site for the growth of biominerals. Fungal growth may produce a copper-containing mineral precipitate, such as copper carbonate produced from a mixture of (NH4)2CO3 and CuCl2. The production of the copper carbonate is produced in the presence of proteins made and secreted by the fungi. These fungal proteins that are found extracellularly aid in the size and morphology of the carbonate minerals precipitated by the fungi.

In addition to precipitating carbonate minerals, fungi can also precipitate uranium-containing phosphate biominerals in the presence of organic phosphorus that acts a substrate for the process. The fungi produce a hyphal matrix, also known as mycelium, that localizes and accumulates the uranium minerals that have been precipitated. Although uranium is often deemed as toxic towards living organisms, certain fungi such as '' Aspergillus niger'' and '' Paecilomyces javanicus'' can tolerate it.

Though minerals can be produced by fungi, they can also be degraded, mainly by oxalic acid–producing strains of fungi. Oxalic acid production is increased in the presence of glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, usi ...

for three organic acid producing fungi: ''Aspergillus niger'', ''Serpula himantioides

''Serpula himantioides'' is a species of fungus that causes damage to timber referred to as dry rot. It is a basidiomycete in the order Boletales. It has been found on all continents except for Antarctica. Recent molecular work demonstrates that ...

'', and '' Trametes versicolor''. These fungi have been found to corrode apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

and galena minerals. Degradation of minerals by fungi is carried out through a process known as neogenesis. The order of most to least oxalic acid secreted by the fungi studied are ''Aspergillus niger'', followed by ''Serpula himantioides'', and finally ''Trametes versicolor''.

In bacteria

It is less clear what purpose biominerals serve in bacteria. One hypothesis is that cells create them to avoid entombment by their own metabolic byproducts. Iron oxide particles may also enhance their metabolism.Other roles

Biomineralization plays significant global roles terraforming the planet, as well as in biogeochemical cycles and as a carbon sink.

Biomineralization plays significant global roles terraforming the planet, as well as in biogeochemical cycles and as a carbon sink.

Composition

Most biominerals can be grouped by chemical composition into one of three distinct mineral classes: silicates, carbonates or phosphates.Silicates

Silicates (glass) are common in marine biominerals, where diatoms and radiolaria form frustules from hydrated amorphous silica (opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Due to its amorphous property, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms ...

).

Carbonates

The major carbonate in biominerals is CaCO3. The most common polymorphs in biomineralization are calcite (e.g. foraminifera, coccolithophores) and aragonite (e.g.coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secre ...

s), although metastable vaterite and amorphous calcium carbonate

Amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) is the amorphous and least stable polymorph of calcium carbonate. ACC is extremely unstable under normal conditions and is found naturally in taxa as wide-ranging as sea urchins, corals, mollusks, and foraminife ...

can also be important, either structurally or as intermediate phases in biomineralization. Some biominerals include a mixture of these phases in distinct, organised structural components (e.g. bivalve shells). Carbonates are particularly prevalent in marine environments, but also present in freshwater and terrestrial organisms.

Phosphates

The most common biogenic phosphate ishydroxyapatite

Hydroxyapatite, also called hydroxylapatite (HA), is a naturally occurring mineral form of calcium apatite with the formula Ca5(PO4)3(OH), but it is usually written Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 to denote that the crystal unit cell comprises two entities ...

(HA), a calcium phosphate (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) and a naturally occurring form of apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

. It is a primary constituent of bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, an ...

, teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, te ...

, and fish scales. Bone is made primarily of HA crystals interspersed in a collagen matrix—65 to 70% of the mass of bone is HA. Similarly HA is 70 to 80% of the mass of dentin

Dentin () (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) ( la, substantia eburnea) is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by e ...

and enamel in teeth. In enamel, the matrix for HA is formed by amelogenins and enamelins instead of collagen. Remineralisation of tooth enamel involves the reintroduction of mineral ions into demineralised enamel. Hydroxyapatite is the main mineral component of enamel in teeth. During demineralisation, calcium and phosphorus ions are drawn out from the hydroxyapatite.The mineral ions introduced during remineralisation restore the structure of the hydroxyapatite crystals.

The clubbing appendages of the peacock mantis shrimp

Peafowl is a common name for three bird species in the genera '' Pavo'' and ''Afropavo'' within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae, the pheasants and their allies. Male peafowl are referred to as peacocks, and female peafowl are refe ...

are made of an extremely dense form of the mineral which has a higher specific strength; this has led to its investigation for potential synthesis and engineering use. Their dactyl appendages have excellent impact resistance due to the impact region being composed of mainly crystalline hydroxyapatite, which offers significant hardness. A periodic layer underneath the impact layer composed of hydroxyapatite with lower calcium and phosphorus content (thus resulting in a much lower modulus) inhibits crack growth by forcing new cracks to change directions. This periodic layer also reduces the energy transferred across both layers due to the large difference in modulus, even reflecting some of the incident energy.

Other minerals

Beyond these main three categories, there are a number of less common types of biominerals, usually resulting from a need for specific physical properties or the organism inhabiting an unusual environment. For example, teeth that are primarily used for scraping hard substrates may be reinforced with particularly tough minerals, such as the iron mineralsmagnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

in chiton

Chitons () are marine molluscs of varying size in the class Polyplacophora (), formerly known as Amphineura. About 940 extant and 430 fossil species are recognized.

They are also sometimes known as gumboots or sea cradles or coat-of-mail sh ...

s or goethite in limpets. Gastropod molluscs living close to hydrothermal vents reinforce their carbonate shells with the iron-sulphur minerals pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

and greigite. Magnetotactic bacteria also employ magnetic iron minerals magnetite and greigite to produce magnetosome

Magnetosomes are membranous structures present in magnetotactic bacteria (MTB). They contain iron-rich magnetic particles that are enclosed within a lipid bilayer membrane. Each magnetosome can often contain 15 to 20 magnetite crystals that form ...

s to aid orientation and distribution in the sediments.

magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

.

File:Common limpets1.jpg, Limpets have carbonate shells and teeth reinforced with goethite

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Diversity

In nature, there is a wide array of biominerals, ranging from iron oxide to strontium sulfate, withcalcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an a ...

biominerals being particularly notable. However, the most taxonomically widespread biomineral is silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is o ...

(SiO2·nH2O), being present in all eukaryotic supergroups. Notwithstanding, the degree of silicification can vary even between closely related taxa, from being found in composite structures with other biominerals (e.g., limpet teeth

Limpets are a group of aquatic snails that exhibit a conical shell shape (patelliform) and a strong, muscular foot. Limpets are members of the class Gastropoda, but are polyphyletic, meaning the various groups called "limpets" descended indepe ...

; to forming minor structures (e.g., ciliate granules; or being a major structural constituent of the organism. The most extreme degree of silicification is evident in the diatoms, where almost all species have an obligate requirement for silicon to complete cell wall formation and cell division. Biogeochemically and ecologically, diatoms are the most important silicifiers in modern marine ecosystems, with radiolarians ( polycystine and phaeodarian rhizarians), silicoflagellates (dictyochophyte

Dictyochophyceae sensu lato is a photosynthetic lineage of heterokont algae.

Taxonomy

* Class Dictyochophyceae Silva 1980 s.l.

** Subclass Sulcophycidae Cavalier-Smith 2013

*** Order Olisthodiscales Cavalier-Smith 2013

**** Family Olisthodiscac ...

and chrysophyte stramenopiles), and sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throug ...

s with prominent roles as well. In contrast, the major silicifiers in terrestrial ecosystems are the land plants (embryophyte

The Embryophyta (), or land plants, are the most familiar group of green plants that comprise vegetation on Earth. Embryophytes () have a common ancestor with green algae, having emerged within the Phragmoplastophyta clade of green algae as si ...

s), with other silicifying groups (e.g., testate amoebae

Testate amoebae (formerly thecamoebians, Testacea or Thecamoeba) are a polyphyletic group of unicellular amoeboid protists, which differ from naked amoebae in the presence of a test that partially encloses the cell, with an aperture from which the ...

) having a minor role.

Broadly, biomineralized structures evolve and diversify when the energetic cost of biomineral production is less than the expense of producing an equivalent organic structure. The energetic costs of forming a silica structure from silicic acid are much less than forming the same volume from an organic structure (≈20-fold less than lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity ...

or 10-fold less than polysaccharides like cellulose). Based on a structural model of biogenic silica, Lobel et al. (1996) identified by biochemical modeling a low-energy reaction pathway for nucleation and growth of silica. The combination of organic and inorganic components within biomineralized structures often results in enhanced properties compared to exclusively organic or inorganic materials. With respect to biogenic silica, this can result in the production of much stronger structures, such as siliceous diatom frustules having the highest strength per unit density of any known biological material, or sponge spicules being many times more flexible than an equivalent structure made of pure silica. As a result, biogenic silica structures are utilized for support, feeding, predation defense and environmental protection as a component of cyst walls. Biogenic silica also has useful optical properties for light transmission and modulation in organisms as diverse as plants, diatoms, sponges, and molluscs. There is also evidence that silicification is used as a detoxification response in snails and plants, biosilica has even been suggested to play a role as a pH buffer for the enzymatic activity of carbonic anhydrase, aiding the acquisition of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis.

Evolution

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some , and sponge-grade organisms may have formed calcite skeletons . But in most lineages, biomineralization first occurred in the

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some , and sponge-grade organisms may have formed calcite skeletons . But in most lineages, biomineralization first occurred in the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ag ...

or Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya. ...

periods. Organisms used whichever form of calcium carbonate was more stable in the water column at the point in time when they became biomineralized, and stuck with that form for the remainder of their biological history (but see for a more detailed analysis). The stability is dependent on the Ca/Mg ratio of seawater, which is thought to be controlled primarily by the rate of sea floor spreading, although atmospheric levels may also play a role.

Biomineralization evolved multiple times, independently, and most animal lineages first expressed biomineralized components in the Cambrian period. Many of the same processes are used in unrelated lineages, which suggests that biomineralization machinery was assembled from pre-existing "off-the-shelf" components already used for other purposes in the organism. Although the biomachinery facilitating biomineralization is complex – involving signalling transmitters, inhibitors, and transcription factors – many elements of this 'toolkit' are shared between phyla as diverse as coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secre ...

s, molluscs, and vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxon, taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with vertebral column, backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the ...

s. The shared components tend to perform quite fundamental tasks, such as designating that cells will be used to create the minerals, whereas genes controlling more finely tuned aspects that occur later in the biomineralization process, such as the precise alignment and structure of the crystals produced, tend to be uniquely evolved in different lineages. This suggests that Precambrian organisms were employing the same elements, albeit for a different purpose — perhaps to avoid the inadvertent precipitation of calcium carbonate from the supersaturated Proterozoic

The Proterozoic () is a geological eon spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8million years ago. It is the most recent part of the Precambrian "supereon". It is also the longest eon of the Earth's geologic time scale, and it is subdivided ...

oceans. Forms of mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

that are involved in inducing mineralization in most animal lineages appear to have performed such an anticalcifatory function in the ancestral state. Further, certain proteins that would originally have been involved in maintaining calcium concentrations within cells are homologous in all animals, and appear to have been co-opted into biomineralization after the divergence of the animal lineages. The galaxins are one probable example of a gene being co-opted from a different ancestral purpose into controlling biomineralization, in this case being 'switched' to this purpose in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

scleractinian corals; the role performed appears to be functionally identical to that of the unrelated pearlin gene in molluscs. Carbonic anhydrase serves a role in mineralization broadly in the animal kingdom, including in sponges, implying an ancestral role. Far from being a rare trait that evolved a few times and remained stagnant, biomineralization pathways in fact evolved many times and are still evolving rapidly today; even within a single genus it is possible to detect great variation within a single gene family.

The homology of biomineralization pathways is underlined by a remarkable experiment whereby the nacreous layer of a molluscan shell was implanted into a human tooth, and rather than experiencing an immune response, the molluscan nacre was incorporated into the host bone matrix. This points to the exaptation of an original biomineralization pathway. The biomineralisation capacity of brachiopods and molluscs have also been demonstrated to be homologous, building on a conserved set of genes. This indicates that biomineralisation is likely ancestral to all lophotrochozoans.

The most ancient example of biomineralization, dating back 2 billion years, is the deposition of magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

, which is observed in some bacteria, as well as the teeth of chiton

Chitons () are marine molluscs of varying size in the class Polyplacophora (), formerly known as Amphineura. About 940 extant and 430 fossil species are recognized.

They are also sometimes known as gumboots or sea cradles or coat-of-mail sh ...

s and the brains of vertebrates; it is possible that this pathway, which performed a magnetosensory role in the common ancestor of all bilaterians, was duplicated and modified in the Cambrian to form the basis for calcium-based biomineralization pathways. Iron is stored in close proximity to magnetite-coated chiton teeth, so that the teeth can be renewed as they wear. Not only is there a marked similarity between the magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

deposition process and enamel deposition in vertebrates, but some vertebrates even have comparable iron storage facilities near their teeth.

Potential applications

Most traditional approaches to synthesis of nanoscale materials are energy inefficient, requiring stringent conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressure or pH) and often produce toxic byproducts. Furthermore, the quantities produced are small, and the resultant material is usually irreproducible because of the difficulties in controlling agglomeration. In contrast, materials produced by organisms have properties that usually surpass those of analogous synthetically manufactured materials with similar phase composition. Biological materials are assembled in aqueous environments under mild conditions by using macromolecules. Organic macromolecules collect and transport raw materials and assemble these substrates and into short- and long-range ordered composites with consistency and uniformity. The aim of biomimetics is to mimic the natural way of producing minerals such asapatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

s. Many man-made crystals require elevated temperatures and strong chemical solutions, whereas the organisms have long been able to lay down elaborate mineral structures at ambient temperatures. Often, the mineral phases are not pure but are made as composites that entail an organic part, often protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

, which takes part in and controls the biomineralization. These composites are often not only as hard as the pure mineral but also tougher, as the micro-environment controls biomineralization.

Architecture

Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'', known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus '' Baci ...

''

extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide struc ...

(ECM) composed of different organic substances, such as extracellular proteins, exopolysaccharides and nucleic acids. While the ability to generate ECM appears to be a common feature of multicellular bacterial communities, the means by which these matrices are constructed and function are diverse.

extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide struc ...

(brown) promotes the crystals' growth in specific directions. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'', known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus '' Baci ...

'' has already been shown to respond to its environment, by changing the production of its ECM. It uses the polymers produced by single cells during biofilm formation as a physical cue to coordinate ECM production by the bacterial community.

Uranium contaminants

Biogenic mineral controversy

The geological definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living beings. However some minerals are often biogenic (such as calcite) or areorganic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon- hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. Th ...

s in the sense of chemistry (such as mellite

Mellite, also called honeystone, is an unusual mineral being also an organic chemical. It is chemically identified as an aluminium salt of mellitic acid, and specifically as aluminium benzene hexacarboxylate hydrate, with the chemical formula Al2 ...

). Moreover, living beings often synthesize inorganic minerals (such as hydroxylapatite) that also occur in rocks.

The International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is the generally recognized standard body for the definition and nomenclature of mineral species. , the IMA recognizes 5,650 official mineral species out of 5,862 proposed or traditional ones.

A topic of contention among geologists and mineralogists has been the IMA's decision to exclude biogenic crystalline substances. For example, Lowenstam (1981) stated that "organisms are capable of forming a diverse array of minerals, some of which cannot be formed inorganically in the biosphere."

Skinner (2005) views all solids as potential minerals and includes biominerals in the mineral kingdom, which are those that are created by the metabolic activities of organisms. Skinner expanded the previous definition of a mineral to classify "element or compound, amorphous or crystalline, formed through '' biogeochemical '' processes," as a mineral.

Recent advances in high-resolution genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar worki ...

and X-ray absorption spectroscopy are providing revelations on the biogeochemical relations between microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s and minerals that may shed new light on this question. For example, the IMA-commissioned "Working Group on Environmental Mineralogy and Geochemistry " deals with minerals in the hydrosphere, atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. ...

, and biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be ...

. The group's scope includes mineral-forming microorganisms, which exist on nearly every rock, soil, and particle surface spanning the globe to depths of at least 1600 metres below the sea floor and 70 kilometres into the stratosphere (possibly entering the mesosphere).

Biogeochemical cycles have contributed to the formation of minerals for billions of years. Microorganisms can precipitate metals from solution, contributing to the formation of ore deposits. They can also catalyze the dissolution of minerals.

Prior to the International Mineralogical Association's listing, over 60 biominerals had been discovered, named, and published. These minerals (a sub-set tabulated in Lowenstam (1981)) are considered minerals proper according to Skinner's (2005) definition. These biominerals are not listed in the International Mineral Association official list of mineral names, however, many of these biomineral representatives are distributed amongst the 78 mineral classes listed in the Dana classification scheme.

Skinner's (2005) definition of a mineral takes this matter into account by stating that a mineral can be crystalline or amorphous. Although biominerals are not the most common form of minerals, they help to define the limits of what constitutes a mineral proper. Nickel's (1995) formal definition explicitly mentioned crystallinity as a key to defining a substance as a mineral. A 2011 article defined icosahedrite, an aluminium-iron-copper alloy as mineral; named for its unique natural icosahedral symmetry, it is a quasicrystal. Unlike a true crystal, quasicrystals are ordered but not periodic.

List of minerals

Examples of biogenic minerals include: *Apatite

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common ...

in bones and teeth.

* Aragonite, calcite, fluorite in vestibular systems (part of the inner ear) of vertebrates.

* Aragonite and calcite in travertine and biogenic silica (siliceous sinter, opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·''n''H2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Due to its amorphous property, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms ...

) deposited through algal action.

* Hydroxylapatite formed by mitochondria.

* Magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

and greigite formed by magnetotactic bacteria.

* Pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

and marcasite in sedimentary rocks deposited by sulfate-reducing bacteria.

* Quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

formed from bacterial action on fossil fuels (gas, oil, coal).

* Goethite found as filaments in limpet teeth.

Astrobiology

It has been suggested that biominerals could be important indicators of extraterrestrial life and thus could play an important role in the search for past or present life on Mars. Furthermore, organic components ( biosignatures) that are often associated with biominerals are believed to play crucial roles in both pre-biotic andbiotic

Biotics describe living or once living components of a community; for example organisms, such as animals and plants.

Biotic may refer to:

*Life, the condition of living organisms

*Biology, the study of life

* Biotic material, which is derived from ...

reactions.

On January 24, 2014, NASA reported that current studies by the ''Curiosity'' and ''Opportunity'' rovers on the planet Mars will now be searching for evidence of ancient life, including a biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be ...

based on autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

ic, chemotroph

A Chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic molecule, organic (chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic compound, inorganic (chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph de ...

ic and/or chemolithoautotrophic microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s, as well as ancient water, including fluvio-lacustrine environments (plain

In geography, a plain is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and as plateaus or uplands. ...

s related to ancient river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the ...

s or lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much lar ...

s) that may have been habitable

Habitability refers to the adequacy of an environment for human living. Where housing is concerned, there are generally local ordinances which define habitability. If a residence complies with those laws it is said to be habitable. In extreme e ...

. The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on the planet Mars is now a primary NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

objective.

See also

* Biocrystallization * Biofilm * Biointerface *Biomineralising polychaetes

Biomineralising polychaetes are polychaetes that Biomineralization, biomineralize.

The most important biomineralizing polychaetes are Serpulidae, serpulids, Sabellidae, sabellids and Cirratulidae, cirratulids. They secrete tubes of calcium carb ...

* Microbiologically induced calcite precipitation

* Bone mineral

* Mineralized tissues

* Susannah M. Porter history of biomineralization

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

An overview of the bacteria involved in biomineralization from the Science Creative Quarterly

'Data and literature on modern and fossil Biominerals': http://biomineralisation.blogspot.fr

Minerals and the Origins of Life

( Robert Hazen,

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

) (video, 60m, April 2014).

Biomineralization web-book: bio-mineral.org

Special German Research Project About the Principles of Biomineralization

{{Portal bar, Astronomy, Biology, Evolutionary biology, Geology, Paleontology Pedology Physiology Bioinorganic chemistry Biological processes Skeletal system