Military History Of Zimbabwe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

Around the 8th and 9th centuries the Bantu-speaking Shona ( Gokomere, Sotho-Tswana and related tribes) arrived from the north and both the San and the early ironworkers were driven out. This group gave rise to the maShona tribes, and probably also gave rise to the Lemba people through a merger with descent from the ancient

Around the 8th and 9th centuries the Bantu-speaking Shona ( Gokomere, Sotho-Tswana and related tribes) arrived from the north and both the San and the early ironworkers were driven out. This group gave rise to the maShona tribes, and probably also gave rise to the Lemba people through a merger with descent from the ancient

In 1817, the Southern Shona regions were invaded by Mzilikazi, originally a lieutenant of Zulu King Shaka who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. After a brief alliance with the Transvaal Ndebele, Mzilikazi became leader of the Ndebele people. Many of the Shona people were incorporated and the rest were either made satellite territories who paid taxes to the Ndebele Kingdom. He called his new nation Mthwakazi (which the British later called

In 1817, the Southern Shona regions were invaded by Mzilikazi, originally a lieutenant of Zulu King Shaka who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. After a brief alliance with the Transvaal Ndebele, Mzilikazi became leader of the Ndebele people. Many of the Shona people were incorporated and the rest were either made satellite territories who paid taxes to the Ndebele Kingdom. He called his new nation Mthwakazi (which the British later called

The first battle in the war occurred on 5 November 1893 when a British

The first battle in the war occurred on 5 November 1893 when a British

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second ''Chimurenga'' or the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, refers to the guerrilla war of 1966–1979 which led to the end of

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second ''Chimurenga'' or the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, refers to the guerrilla war of 1966–1979 which led to the end of

The

The

During this time period the Selous Scouts, operated as special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army. They were named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917), and their motto was ''pamwe chete'', which translated from Shona means "all together", "together only" or "forward together". The charter of the Selous Scouts directed "the clandestine elimination of terrorists/terrorism both within and without the country."

The Selous Scouts were racial-integrated unit (approx. 70% black soldiers) which conducted a highly successful clandestine war against the guerrillas by posing as guerrillas themselves. Their unrivalled tracking abilities, survival and COIN skills made them one of the most feared of the army units by enemy. The unit was responsible for 68% of all enemy casualties within the borders of Rhodesia.

During this time period the Selous Scouts, operated as special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army. They were named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917), and their motto was ''pamwe chete'', which translated from Shona means "all together", "together only" or "forward together". The charter of the Selous Scouts directed "the clandestine elimination of terrorists/terrorism both within and without the country."

The Selous Scouts were racial-integrated unit (approx. 70% black soldiers) which conducted a highly successful clandestine war against the guerrillas by posing as guerrillas themselves. Their unrivalled tracking abilities, survival and COIN skills made them one of the most feared of the army units by enemy. The unit was responsible for 68% of all enemy casualties within the borders of Rhodesia.

The present era in Zimbabwe is called the Third Chimurenga, by the ruling ZANU-PF. The Mugabe administration claims that colonial social and economic structures remained largely intact in the years after the end of Rhodesian rule, with a small minority of white farmers owning the vast majority of the country's arable land (many partys within Zimbabwe question the extent and validity of these assertions, considering twenty years of ZANU-PF rule, the "Willing Buyer-Willing Seller" policy paid for by Britain and the diminished size of Zimbabwe's white population). By 2000 ZANU militants proclaimed violent struggle for

The present era in Zimbabwe is called the Third Chimurenga, by the ruling ZANU-PF. The Mugabe administration claims that colonial social and economic structures remained largely intact in the years after the end of Rhodesian rule, with a small minority of white farmers owning the vast majority of the country's arable land (many partys within Zimbabwe question the extent and validity of these assertions, considering twenty years of ZANU-PF rule, the "Willing Buyer-Willing Seller" policy paid for by Britain and the diminished size of Zimbabwe's white population). By 2000 ZANU militants proclaimed violent struggle for

military history

Military history is the study of armed conflict in the history of humanity, and its impact on the societies, cultures and economies thereof, as well as the resulting changes to local and international relationships.

Professional historians norma ...

of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers invasions of native peoples of Africa ( Shona and Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

*Northern Ndebele language, the language o ...

), encroachment by Europeans ( Portuguese, Boer and British settlers), and civil conflict.

Early history

San and invasion by ironworking cultures

Stone Age evidence indicates that the San people, now living mostly in the Kalahari Desert, are the ancestors of this region's original inhabitants, almost 3,000 years ago. There are also remnants of several ironworking cultures dating back to AD 300. Little is known of the early ironworkers, but it is believed that they put pressure on the San and gradually took over the land.Shona rule

Around the 8th and 9th centuries the Bantu-speaking Shona ( Gokomere, Sotho-Tswana and related tribes) arrived from the north and both the San and the early ironworkers were driven out. This group gave rise to the maShona tribes, and probably also gave rise to the Lemba people through a merger with descent from the ancient

Around the 8th and 9th centuries the Bantu-speaking Shona ( Gokomere, Sotho-Tswana and related tribes) arrived from the north and both the San and the early ironworkers were driven out. This group gave rise to the maShona tribes, and probably also gave rise to the Lemba people through a merger with descent from the ancient Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

who arrived in this region via Sena in Yemen. By the 15th century, the Shona had established a strong empire, known as the Munhumutapa Empire (also called Monomotapa or Mwene Mutapa Empire), with its capital at the ancient city of Zimbabwe -- Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe is a medieval city in the south-eastern hills of Zimbabwe near Lake Mutirikwi and the town of Masvingo. It is thought to have been the capital of a great kingdom during the country's Late Iron Age about which little is known. Con ...

. This empire ruled territory now falling within the modern states of Zimbabwe (which took its name from this city) and Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, but the empire was split by the end of the 15th century with southern part becoming the Urozwi Empire.

The Portuguese began their attempts to subdue the Shona states as early as 1505 but were confined to the coast until 1513. The states were also torn apart by rival factions and trade in gold was gradually replaced by a trade in slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. The empire finally collapsed in 1629 and never recovered. Remnants of the government established another Mutapa kingdom in Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

sometimes called Karanga, who reigned in the region until 1902.

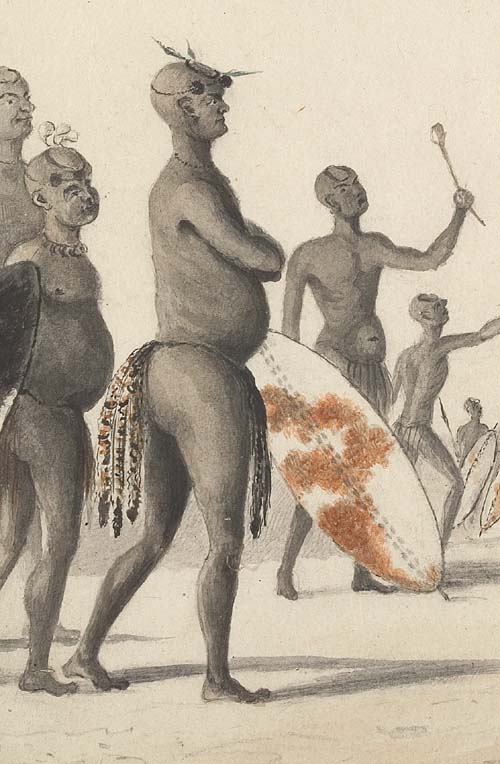

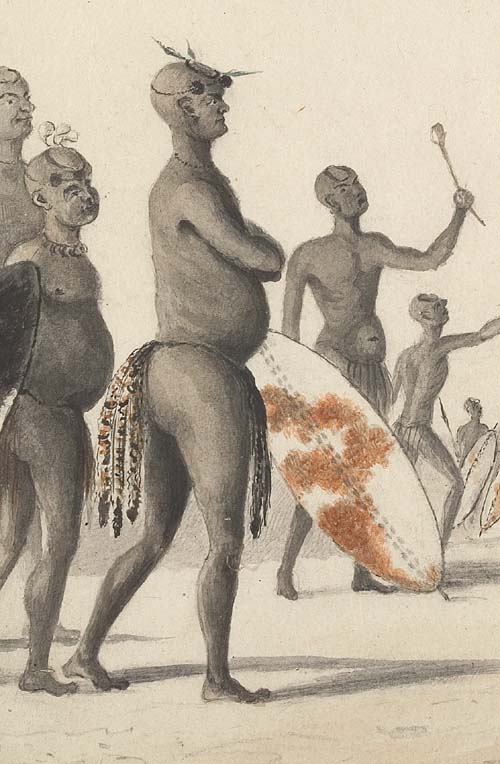

Mfecane

Mfecane ( Zulu), also known as the Difaqane or Lifaqane (Sesotho

Sotho () or Sesotho () or Southern Sotho is a Southern Bantu language of the Sotho–Tswana ("S.30") group, spoken primarily by the Basotho in Lesotho, where it is the national and official language; South Africa (particularly the Free Sta ...

), is an African expression which means something like "the crushing" or "scattering". It describes a period of widespread chaos and disturbance in southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

during the period between 1815 and about 1835 which resulted from the rise to power of Shaka, the Zulu king and military leader who conquered the Nguni people

The Nguni people are a Bantu ethnic group from South Africa, with off-shoots in neighbouring countries in Southern Africa. Swazi (or Swati) people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Northern Ndebele people live in both South Africa (a ...

s between the Tugela and Pongola rivers in the beginning of the nineteenth century, and created a militaristic kingdom in the region. The Mfecane also led to the formation and consolidation of other groups – such as the Ndebele Kingdom, the Mfengu and the Makololo – and the creation of states such as the modern Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked country, landlocked as an Enclave and exclave, enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the Thabana Ntlenyana, highest mountains in Sou ...

.

In 1817, the Southern Shona regions were invaded by Mzilikazi, originally a lieutenant of Zulu King Shaka who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. After a brief alliance with the Transvaal Ndebele, Mzilikazi became leader of the Ndebele people. Many of the Shona people were incorporated and the rest were either made satellite territories who paid taxes to the Ndebele Kingdom. He called his new nation Mthwakazi (which the British later called

In 1817, the Southern Shona regions were invaded by Mzilikazi, originally a lieutenant of Zulu King Shaka who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. After a brief alliance with the Transvaal Ndebele, Mzilikazi became leader of the Ndebele people. Many of the Shona people were incorporated and the rest were either made satellite territories who paid taxes to the Ndebele Kingdom. He called his new nation Mthwakazi (which the British later called Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi r ...

), a name derived from the original settlers the San people called aba (The Ndebele called themselves Matabele, but because of linguistic differences, were called Ndebele by the local Sotho-Tswana.) Mzilikazi's invasion of the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

was one part of a vast series of inter-related wars, forced migrations and famines that indigenous people and later historians came to call the Mfecane. In the Transvaal, the Mfecane severely weakened and disrupted the towns and villages of the Sotho-Tswana chiefdoms, their political systems and economies, making them very weak, and easy to colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

by the European settlers who would shortly arrive from the south.

As Ndebele moved into Transvaal, the remnants of the Bavenda retreated north to the Waterberg and Zoutpansberg, while Mzilikazi made his chief kraal north of the Magaliesberg mountains near present-day Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

, with an important military outpost to guard trade routes to the north at Mosega, not far from the site of the modern town of Zeerust. From about 1827 until about 1836, Mzilikazi dominated the southwestern Transvaal. Before that time the region between the Vaal and Limpopo was scarcely known to Europeans, but in 1829, Mzilikazi was visited at Mosega by Robert Moffat, and between that date and 1836 a few British traders and explorers visited the country and made known its principal features.

Boer confrontations

In the 1830s and 1840s, white descendants of Dutch pioneers, collectively known as '' voortrekkers'' or ''trekboers

The Trekboers ( af, Trekboere) were nomadic pastoralists descended from European settlers on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the C ...

'', departed Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

with hundreds of their dependents to escape British rule. This exodus, in what came to be called the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

, often pitted the migrant settlers against local forces and resulted in the formation of short-lived Boer republics. Between 1835 and 1838, the trekkers began crossing the Vaal River and skirmishing with Ndebele regiments. On 16 October 1836, a Boer column under Hendrik Potgieter

Andries Hendrik Potgieter, known as Hendrik Potgieter (19 December 1792 – 16 December 1852) was a Voortrekker leader and the last known Champion of the Potgieter family. He served as the first head of state of Potchefstroom from 1840 and 184 ...

was attacked by a Ndebele force numbering some 5,000. They succeeded in seizing Potgieter's livestock, but were unable to penetrate his laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised militar ...

. One of the Tswana chiefs, Moroko, later convinced Potgieter to pull his wagons back to the safety of Thaba-Nchu - where his men could seek food and protection. In January 1837, over a hundred Boers and around sixty Tswana returned with a vengeance. Led by Potgieter and Gerrit Maritz, they raided Mzilikazi's settlement at Mosega and drove him across the Limpopo River. Prominent voortrekkers immediately claimed the territory which Mzilikazi had forfeited, and later arrivals continued to push deeper into the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

.

Voortrekker parties harassed Mzilikazi as late as 1851, but the following year burghers of the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

finally negotiated a lasting peace. However, gold was discovered near Mthwakazi in 1867 and Europe's colonial powers became increasingly interested in the region. Mzilikazi died in 1868, near Bulawayo. His son, Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo (c. 1845 – presumed January 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a refere ...

, granted several concessions to European traders, including the 1888 Rudd treaty giving Cape imperialist Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

exclusive mineral rights in much of the lands east of Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi r ...

. Gold was already known to exist in nearby Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe.

Currently, Mashonaland is divided into four provinces,

* Mashonaland West

* Mashonaland Central

* Mashonaland East

* Harare

The Zimbabwean capital of Harare, a province unto itself, lies entirely ...

, so with the Rudd concession Rhodes obtained a royal charter to form the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

in 1889.

Pioneer Column

In 1890, Rhodes sent a group of settlers, known as the Pioneer Column, into Mashonaland. The 400+ man Pioneer Column was guided by the explorer and big game hunterFrederick Selous

Frederick Courteney Selous, DSO (; 31 December 1851 – 4 January 1917) was a British explorer, officer, professional hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in Southeast Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir Henry Rider ...

and was officially designated the ''British South Africa Company Police'' (BSACP) accompanied by about 100 Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP). When they reached Harari Hill, they founded Fort Salisbury (now Harare

Harare (; formerly Salisbury ) is the capital and most populous city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 940 km2 (371 mi2) and a population of 2.12 million in the 2012 census and an estimated 3.12 million in its metropolitan ...

). Rhodes had been distributing land to the settlers even before the royal charter, but the charter legitimized his further actions with the British government. By 1891 an Order-in-Council declared Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi r ...

, Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe.

Currently, Mashonaland is divided into four provinces,

* Mashonaland West

* Mashonaland Central

* Mashonaland East

* Harare

The Zimbabwean capital of Harare, a province unto itself, lies entirely ...

, and Bechuanaland a British protectorate. By 1892, the number of men in the force had decreased and the BSACP was replaced by a number of volunteer forces - the Mashonaland Horse, the Mashonaland Mounted Police and the Mashonaland Constabulary, and later additions of Salisbury Horse, Victoria Rangers, and Raaf's Rangers. The BSACP was later renamed the British South Africa Police (BSAP) and this force stayed together for much of the 20th century.

Rhodes had a vested interest in the continued expansion of white settlements in the region, so now with the cover of a legal mandate, he used a brutal attack by Ndebele against the Shona near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) in 1893 as a pretense for attacking the kingdom of Lobengula.

First Matabele War

The first battle in the war occurred on 5 November 1893 when a British

The first battle in the war occurred on 5 November 1893 when a British laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised militar ...

was attacked by the Matabele on open ground a few miles from the Impembisi River. The laager consisted of 670 British soldiers, 400 of whom were mounted along with a small force of native allies fought off the Imbezu and Ingubu regiments computed by Sir John Willoughby to number 1,700 warriors in all. The laager had with it a small artillery of five Maxim gun

The Maxim gun is a recoil-operated machine gun invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim. It was the first fully automatic machine gun in the world.

The Maxim gun has been called "the weapon most associated with imperial conquest" by historian M ...

, two seven-pounders, one Gardner gun, and one Hotchkiss. The Maxim guns took center stage and decimated the native force. Other African regiments were in the immediate vicinity, estimated at 5,000 men, however this force never took part in the fighting.

Lobengula had 80,000 spearmen and 20,000 riflemen, against fewer than 700 soldiers of the British South Africa Police, but the Ndebele warriors were no match against the British Maxim guns. Leander Starr Jameson immediately sent his troops to Bulawayo to try to capture Lobengula, but the king escaped and left Bulawayo in ruins behind him. The group of white settlers was sent to find Lobengula along the Shangani river, which they did, but nearly all members of this patrol were killed in battle on the Shangani river in Matabeleland in 1893. The incident achieved a lasting, prominent place in Rhodesian colonial history as the Shangani Patrol and is roughly the British equivalent to Custer's Last Stand. But this was no victory for the Ndebele. Under somewhat mysterious circumstances, King Lobengula died in January 1894, and within a few short months the British South Africa Company controlled most of the Matabeleland and white settlers continued to arrive.

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a raid on Paul Kruger'sTransvaal Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

carried out by Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895–96. It was intended to trigger an uprising by the primarily British expatriate workers (known as Uitlanders) in the Transvaal Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name Transvaal.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; af, ...

but failed to do so. The raid was ineffective and no uprising took place, but it did much to bring about the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

and the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion or part of what is now known in Zimbabwe as the First ''Chimurenga'', was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region later known as Southern Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe. ...

.

Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War—or the First '' Chimurenga'', as it is often called in modern Zimbabwe—comprised revolts againstBritish South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

rule by the Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

*Northern Ndebele language, the language o ...

and Shona peoples during 1896 and 1897.

According to ''UNESCO General History of Africa - VII Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935'', the "Chimurenga, as the Shona termed their form of armed resistance, began in March 1896 in Matabeleland and June in Mashonaland. The first casualty was an African policeman employed by the British South Africa Company, killed 20 March. The first attack upon Europeans occurred in the town of Essexvale on 22 March, when seven Europeans and two Africans were killed.... Within a week, 130 Europeans had been killed in Matabeleland. Africans were armed with Martini-Henry rifles, Lee Metfords, elephant guns, muskets and blunderbusses, as well as with the traditional spears, axes, knobkerries and bows and arrows".

Mlimo, the Ndebele spiritual/religious leader, is credited with fomenting much of the anger that led to this confrontation. He convinced the Ndebele and Shona that the white settlers (almost 4,000 strong by then) were responsible for the drought, locust plagues and the cattle disease rinderpest

Rinderpest (also cattle plague or steppe murrain) was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic buffalo, and many other species of even-toed ungulates, including gaurs, buffaloes, large antelope, deer, giraffes, wildebeests, and warthogs ...

ravaging the country at the time. Mlimo's call to battle was well timed. Only a few months earlier, the British South Africa Company's Administrator General for Matabeleland, Leander Starr Jameson, had sent most of his troops and armaments to fight the Transvaal Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

in the Jameson Raid. This left the country's defences in disarray. The Ndebele began their revolt in March 1896, and in June 1896 they were joined by the Shona.

The British South Africa Company immediately sent troops to suppress the Ndebele and the Shona, but it took months for the British to relieve their major colonial fortifications under siege by native warriors. Mlimo was eventually assassinated in his temple in Matobo Hills

The Matobo National Park forms the core of the Matobo or Matopos Hills, an area of granite kopjes and wooded valleys commencing some south of Bulawayo, southern Zimbabwe. The hills were formed over 2 billion years ago with granite being forced t ...

by the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham. Upon learning of the death of Mlimo, Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

boldly walked unarmed into the native's stronghold and persuaded the impi to lay down their arms. The war thus ended in October 1897.

First World War

Second World War

Malayan Emergency

Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second ''Chimurenga'' or the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, refers to the guerrilla war of 1966–1979 which led to the end of

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second ''Chimurenga'' or the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, refers to the guerrilla war of 1966–1979 which led to the end of Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

and the ''de jure'' independence of Zimbabwe. It was a three-way conflict between the predominantly white minority government of Ian Smith and the Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front was a right-wing conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. It was the last ruling party of Southern Rhodesia prior to that country's unilateral declaration of independence, and the rul ...

and two rival black nationalist movements: the Maoist Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant organisation that fought against white minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). ZANU split in 1975 into wings loyal to Robert Muga ...

(ZANU), led by Robert Mugabe, drew its support mostly from the Shona people, while the Marxist Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zimba ...

(ZAPU) of Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

was mostly supported by Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

*Northern Ndebele language, the language o ...

. movements, led by Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

respectively.

Overview

With the breakup ofFederation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the Self-governing colony, self-governing British colony of Southe ...

in 1964 the army underwent a large- scale reorganization by the British. In 1965, Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

took matters into its own hands in 1965 with a " Unilateral Declaration of Independence" (UDI). From April 1966 onwards groups of Soviet-supported guerrillas infiltrated Rhodesia from neighbouring Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

in steadily increasing numbers, with the goal of overthrowing the white-rule government, but the Second Chimurenga is generally considered to have started in earnest on 21 December 1972 when an attack took place on a farm in the Centenary District, with further attacks on other farms in the following days.

As the guerrilla activity increased in 1973 "Operation Hurricane" started and the military prepared itself for war. During 1974 a major effort by the security forces resulted in many guerrillas being killed and the number inside the country reduced to less than 100. However, a second front in the Second Chumerenga emerged in 1974 when the Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

withdrew from its colonly of Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

.

In 1976 Operations "Thrasher" and "Repulse" started in order to contain the ever-increasing influx of guerrillas. At the same time rivalry between the two main guerrilla factions increased and resulted in open fighting in the training camps in Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

, with over 600 deaths. The Soviets increased their influence and began to take a more active role in the training and control of the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), a Marxist–Leninist political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhodes ...

(ZIPRA) guerrillas. Perhaps too late, the Rhodesians decided to take the war to the enemy, and cross-border operations, which had started in 1976 with a raid on a major base in Mozambique in which the Rhodesians had killed over 1,200 guerrillas and captured huge amounts of weapons, were stepped up. In 1977, Operation "Dingo" was a major raid on large guerrilla camps such as Chimoio and Tembue in Mozambique which resulted in thousands of guerrilla deaths and the capture of supplies sorely needed by the Rhodesians.

In September 1978, the guerrillas again took the offensive by shooting down a Rhodesian airliner Air Rhodesia Flight 825 with a SAM-7

The 9K32 Strela-2 (russian: Cтрела, "arrow"; NATO reporting name SA-7 Grail) is a light-weight, shoulder-fired, surface-to-air missile (or MANPADS) system. It is designed to target aircraft at low altitudes with passive infrared homing ...

missile. Ten civilians who survived the crash were subsequently massacred at the crash site by ZIPRA guerrillas, increasing calls for massive retaliation by the Rhodesian security forces. On October of that same year, the Rhodesian Air Force launched the daring "Green Leader" attack on a ZIPRA camp outside Lusaka, the Rhodesian fighters completely taking over Zambian air space for the duration of the raid. On 12 February 1979 as the war increased even more in intensity, another civilian airliner Air Rhodesia Flight 827

Air Rhodesia Flight 827, the '' Umniati'', was a scheduled civilian flight between Kariba and Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) that was shot down soon after takeoff on 12 February 1979 by Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) guerril ...

was hit by another shoulder-fired missile; all 59 passengers and crew were killed when the aircraft turned into a huge fireball.

Rhodesian Light Infantry

The

The Rhodesian Light Infantry

The 1st Battalion, Rhodesian Light Infantry (1RLI), commonly The Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI), was a regiment formed in 1961 at Brady Barracks (Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia) as a light infantry unit within the army of the Federation of Rhodesia ...

(RLI) was at the forefront of the Rhodesian war. It was a regular army infantry regiment in the Rhodesian army, composed only of white recruits. The battalion was organised into four company size sub-units called 'Commandos'; 1, 2, 3 and Support Commando. In theory each commando had five 'Troops' (platoon size structures), though much of the time there were only four. The average fighting strength of a Commando was about 70. The rank structure was; Trooper, Lance-corporal, Corporal, Sergeant etc. All ranks were called 'troopies' by the Rhodesian media.

The RLI's most characteristic deployment was the 'fire force' reaction operation. This was an operational assault or response composed of, usually, a first wave of 32 troopers carried to the scene by three helicopters and one DC-3 Dakota (called "Dak"), with a command/gun helicopter and a light attack-aircraft in support. The latter was a Cessna Skymaster, usually armed with two 30 mm rocket pods and two small napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated al ...

-bombs (made in Rhodesia and called 'Fran-tan').

The RLI became extremely adept at this type of military operation and the battalion killed or captured around 3000 of the enemy (the vast majority being Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army) in the last three years of the war, whilst losing less than three hundred killed and wounded (not counting those casualties incurred in patrolling or external ops).

In addition to the fire force, the four Commandos were often used in patrolling actions, mostly inside Rhodesia but sometimes in Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

and Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

. In these operations troopies were required to carry well over 100 lbs of equipment for five to tens days for one patrol and come back and repeat, for weeks, sometimes months. Also, they participated in many attacks on enemy camps in above countries. In a few of these attacks most or all of the battalion was involved.

The First Battalion Rhodesian Light Infantry was originally formed within the army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1961 in Bulawayo. The battalion's nucleus came from the short-lived Number One Training Unit, which had been raised to provide personnel for a white infantry battalion as well as for C Squadron 22 (Rhodesian) SAS

The Rhodesian Special Air Service or Rhodesian SAS was a Rhodesian special forces unit. It comprised:

*C Squadron, Special Air Service Regiment (Malayan Emergency (1951–1953)

*"C" Squadron (Rhodesian) Special Air Service (1961–1978)

*1 (Rhodes ...

and the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment Selous Scouts (not the Selous Scout special forces regiment of the same name).

Selous Scouts

During this time period the Selous Scouts, operated as special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army. They were named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917), and their motto was ''pamwe chete'', which translated from Shona means "all together", "together only" or "forward together". The charter of the Selous Scouts directed "the clandestine elimination of terrorists/terrorism both within and without the country."

The Selous Scouts were racial-integrated unit (approx. 70% black soldiers) which conducted a highly successful clandestine war against the guerrillas by posing as guerrillas themselves. Their unrivalled tracking abilities, survival and COIN skills made them one of the most feared of the army units by enemy. The unit was responsible for 68% of all enemy casualties within the borders of Rhodesia.

During this time period the Selous Scouts, operated as special forces regiment of the Rhodesian Army. They were named after British explorer Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917), and their motto was ''pamwe chete'', which translated from Shona means "all together", "together only" or "forward together". The charter of the Selous Scouts directed "the clandestine elimination of terrorists/terrorism both within and without the country."

The Selous Scouts were racial-integrated unit (approx. 70% black soldiers) which conducted a highly successful clandestine war against the guerrillas by posing as guerrillas themselves. Their unrivalled tracking abilities, survival and COIN skills made them one of the most feared of the army units by enemy. The unit was responsible for 68% of all enemy casualties within the borders of Rhodesia.

British South Africa Police

The BSAP, a unit in existence since the 1890s, formed an important part of the white minority government's fight against black nationalist guerrillas. The force formed a riot unit; a tracker combat team (later renamed the Police Anti-Terrorist Unit or PATU); an Urban Emergency Unit and a Marine Division, and from 1973 offered places to white conscripts as part of Rhodesia's national service scheme. Until the late 1970s, black Rhodesians were prevented from holding ranks higher than Sub-Inspector in the BSAP, and only white Rhodesians could gain commissioned rank.Patriotic Front

The Patriotic Front (PF) was originally formed in 1976 as a political and military alliance between ZAPU and ZANU during the war against white minority rule. Both movements contributed their respective military forces: ZAPU's military wing was known asZimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), a Marxist–Leninist political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhodes ...

(ZIPRA) which operated mainly from Zambia and somewhat in Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, and ZANU's guerrillas were known as Zimbabwe National African Liberation Army (ZANLA) which formed in 1965 in Tanzania, but operated mainly from camps around Lusaka

Lusaka (; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was ab ...

, Zambia and later from Mozambique. Objective of the Patriotic Front was to overthrow the white minority regime by means of political pressure and military force.

End of the war

In 1979 another airliner was shot down and the Rhodesians launched more raids on guerrilla bases, successfully avoiding air-defence systems and the Soviet MiG-17s based in Mozambique. A raid was made by the SAS and the Selous Scouts on the ZIPRA HQ in Lusaka, where they narrowly missed being able to kill the ZIPRA leader, Nkomo. The Rhodesian people tired of increasing war and political isolation, so the war ended when the white-ruled government of Rhodesia handed power over to British at the 1979 Lancaster House Constitutional Conference, at the behest of bothSouth Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

(its major backer) and the US, multi-ethnic elections were subsequently held in early 1980. Britain recognised this new government and the newly, internationally recognised, independent country was renamed as Zimbabwe. A nucleus of former RLI personnel remained to train and form the First Zimbabwe Commando Battalion of the Zimbabwe National Army

The Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) is the primary branch of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces responsible for land-oriented military operations. It is the largest service branch under the Zimbabwean Joint Operations Command (JOC). The modern army has ...

, however, the RLI regiment itself was disbanded in 1980. The Selous Scouts were also disbanded in 1980, but many of its soldiers travelled south to join the Apartheid South African Defence Force, where they joined 5 Reconnaissance Commando. The BSAP, which at the time of Mugabe's victory consisted of approximately 11,000 regulars (about 60% black) and almost 35,000 reservists, of whom the overwhelming majority were white, was renamed the Zimbabwe Republic Police

The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) is the national police force of Zimbabwe, having succeeded the British South Africa Police on 1 August 1980.

History

The predecessor of the Zimbabwe Republic Police was the British South Africa Police of Rhode ...

and followed an official policy of "Africanisation", in which senior white officers were retired and their positions filled by black officers.

Third Chimurenga

Following majority rule elections, the rivalry that had been fermenting between ZAPU and ZANU erupted, with guerrilla activity starting again in the Matabeleland provinces (south-western Zimbabwe). Armed resistance in Matabeleland was met with bloody government repression. At least 20,000 Matabele died in the ensuing near-genocidal massacres, perpetrated by an elite, communist-trained brigade, known in Zimbabwe as theGukurahundi

The ''Gukurahundi'' was a genocide in Zimbabwe which arose in 1982 until the Unity Accord in 1987. It derives from a Shona language term which loosely translates to "the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains".

During ...

. A peace accord was negotiated and on 30 December 1987 Mugabe became head of state after changing the constitution to usher in his vision of a presidential regime. On 19 December 1989 ZAPU merged with ZANU under the name ZANU-Patriotic Front ( ZANU-PF).

land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

the "Third Chimurenga". The beginning of the "Third Chimurenga" is often attributed to the need to distract Zimbabwean electorate from the poorly conceived war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

and deepening economic problems blamed on graft and ineptitude in the ruling party.

The opposition briefly used the term to describe Zimbabwe's current struggles aimed at removing the ZANU government, resolving the Land Question, the establishment of democracy, rebuilding the rule of law and good governance, as well as the eradication of corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

in Government. The term is no longer in vogue amongst Zimbabwe's urban population and lacks the gravitas it once had so was dropped from the opposition's lexicon.

Modern Zimbabwe

In 1999, the Government of Zimbabwe sent a sizeable military force into the Democratic Republic ofCongo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

to support the government of President Laurent Kabila during the Second Congo War

The Second Congo War,, group=lower-alpha also known as the Great War of Africa or the Great African War and sometimes referred to as the African World War, began in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in August 1998, little more than a year a ...

. Those forces were largely withdrawn in 2002.

Footnotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Military History Of Zimbabwe