Migration (birds) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a

Aristotle, however, suggested that swallows and other birds hibernated. This belief persisted as late as 1878 when

Aristotle, however, suggested that swallows and other birds hibernated. This belief persisted as late as 1878 when  Bewick then describes an experiment that succeeded in keeping swallows alive in Britain for several years, where they remained warm and dry through the winters. He concludes:

Bewick then describes an experiment that succeeded in keeping swallows alive in Britain for several years, where they remained warm and dry through the winters. He concludes:

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or in only one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal area). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality. Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1,800 of the world's 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants.

Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or in only one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal area). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality. Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1,800 of the world's 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants.

Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or  Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to

Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to

A similar situation occurs with

A similar situation occurs with

Some large broad-winged birds rely on

Some large broad-winged birds rely on

Many long-distance migrants appear to be genetically programmed to respond to changing day length. Species that move short distances, however, may not need such a timing mechanism, instead moving in response to local weather conditions. Thus mountain and moorland breeders, such as

Many long-distance migrants appear to be genetically programmed to respond to changing day length. Species that move short distances, however, may not need such a timing mechanism, instead moving in response to local weather conditions. Thus mountain and moorland breeders, such as

Sometimes circumstances such as a good breeding season followed by a food source failure the following year lead to irruptions in which large numbers of a species move far beyond the normal range.

Sometimes circumstances such as a good breeding season followed by a food source failure the following year lead to irruptions in which large numbers of a species move far beyond the normal range.

Early studies on the timing of migration began in 1749 in Finland, with Johannes Leche of Turku collecting the dates of arrivals of spring migrants.

Bird migration routes have been studied by a variety of techniques including the oldest, marking. Swans have been marked with a nick on the beak since about 1560 in England. Scientific

Early studies on the timing of migration began in 1749 in Finland, with Johannes Leche of Turku collecting the dates of arrivals of spring migrants.

Bird migration routes have been studied by a variety of techniques including the oldest, marking. Swans have been marked with a nick on the beak since about 1560 in England. Scientific  An older technique developed by

An older technique developed by

Human activities have threatened many migratory bird species. The distances involved in bird migration mean that they often cross political boundaries of countries and conservation measures require international cooperation. Several international treaties have been signed to protect migratory species including the

Human activities have threatened many migratory bird species. The distances involved in bird migration mean that they often cross political boundaries of countries and conservation measures require international cooperation. Several international treaties have been signed to protect migratory species including the

Dedicated issue of ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B'' on Adaptation to the Annual Cycle.

Route of East Asian Migratory Flyaway

Olango Wildlife Sanctuary as a refuelling station of migratory birds

Migration Ecology Group, Lund University, Sweden

Migrate.ou.edu

– Migration Interest Group: Research Applied Toward Education, USA

* ttps://www.sciencedaily.com/news/plants_animals/birds/ Bird Research by Science Daily includes several articles on bird migration

The Nature Conservancy's Migratory Bird Program

The Compasses of Birds

– a review from the Science Creative Quarterly

BBC Supergoose

– satellite tagging of light-bellied brent geese

– follow the annual migration of ospreys from Cape Cod to Cuba to Venezuela

Bat predation on migrating birds

Global Register of Migratory Species

– features not only birds, but other migratory vertebrates such as fishes

eBird.com Occurrence Maps

– Occurrence maps of migrations of various species in United States

Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

– "''Fostering greater understanding, appreciation, and protection of the grand phenomenon of bird migration.''"

Trektellen.org

– Live bird migration counts and ringing records from all over the world

Hawkcount.org

– Count data and site profiles for over 300 North American Hawkwatch sites

Migraction.net

– Interactive database with real-time information on bird migration (France) {{Authority control

flyway

A flyway is a flight path used by large numbers of birds while migrating between their breeding grounds and their overwintering quarters. Flyways generally span continents and often pass over oceans. Although applying to any species of migrati ...

, between breeding

Breeding is sexual reproduction that produces offspring, usually animals or plants. It can only occur between a male and a female animal or plant.

Breeding may refer to:

* Animal husbandry, through selected specimens such as dogs, horses, and rab ...

and wintering

Winter is the coldest season of the year in Polar regions of Earth, polar and temperate climates. It occurs after autumn and before spring (season), spring. The tilt of Axial tilt#Earth, Earth's axis causes seasons; winter occurs when a Hemi ...

grounds. Many species of bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

migrate. Migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by humans, and is driven primarily by the availability of food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is inge ...

. It occurs mainly in the northern hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

, where birds are funneled onto specific routes by natural barriers such as the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

or the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

.

Migration of species such as stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

s, turtle doves

''Streptopelia'' is a genus of birds in the pigeon and dove family Columbidae. These are mainly slim, small to medium-sized species. The upperparts tend to be pale brown and the underparts are often a shade of pink. Many have a characteristic bla ...

, and swallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae, are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

s was recorded as many as 3,000 years ago by Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

authors, including Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, and in the Book of Job

The Book of Job (; hbo, אִיּוֹב, ʾIyyōḇ), or simply Job, is a book found in the Ketuvim ("Writings") section of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), and is the first of the Poetic Books in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Scholars ar ...

. More recently, Johannes Leche began recording dates of arrivals of spring migrants in Finland in 1749, and modern scientific studies have used techniques including bird ringing

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight ...

and satellite tracking

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

to trace migrants. Threats to migratory birds have grown with habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

, especially of stopover and wintering sites, as well as structures such as power lines and wind farms.

The Arctic tern

The Arctic tern (''Sterna paradisaea'') is a tern in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar breeding distribution covering the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe (as far south as Brittany), Asia, and North America (as far south a ...

holds the long-distance migration record for birds, traveling between Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

breeding grounds and the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

each year. Some species of tubenoses (Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are of ...

) such as albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacifi ...

es circle the earth, flying over the southern oceans, while others such as Manx shearwaters

The Manx shearwater (''Puffinus puffinus'') is a medium-sized shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. The scientific name of this species records a name shift: Manx shearwaters were called Manks puffins in the 17th century. Puffin is an ...

migrate between their northern breeding grounds and the southern ocean. Shorter migrations are common, while longer ones are not. The shorter migrations include altitudinal migration

Altitudinal migration is a short-distance animal migration from lower altitudes to higher altitudes and back. Altitudinal migrants change their elevation with the seasons making this form of animal migration seasonal. Altitudinal migration can be m ...

s on mountains such as the Andes and Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

.

The timing of migration seems to be controlled primarily by changes in day length. Migrating birds navigate using celestial cues from the sun and stars, the earth's magnetic field, and mental maps.

Historical views

In the Pacific, traditional land finding techniques used byMicronesians

The Micronesians or Micronesian peoples are various closely related ethnic groups native to Micronesia, a region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They are a part of the Austronesian ethnolinguistic group, which has an Urheimat in Taiwan.

Ethno ...

and Polynesians suggest that bird migration was observed and interpreted for more than 3,000 years. In Samoan tradition, for example, Tagaloa sent his daughter Sina to Earth in the form of a bird, Tuli, to find dry land, the word tuli referring specifically to land finding waders, often to the Pacific golden plover. Bird migrations were recorded in Europe from at least 3,000 years ago by the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

writers Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

. The Bible, as in the Book of Job

The Book of Job (; hbo, אִיּוֹב, ʾIyyōḇ), or simply Job, is a book found in the Ketuvim ("Writings") section of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), and is the first of the Poetic Books in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Scholars ar ...

, notes migrations with the inquiry: "Is it by your insight that the hawk hovers, spreads its wings southward?" The author of Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning " Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewish ...

wrote: "Even the stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

in the heavens know its seasons, and the turtle dove, the swift

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIFT, ...

and the crane keep the time of their arrival."

Aristotle recorded that cranes traveled from the steppes of Scythia

Scythia (Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

His ...

to marshes at the headwaters of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, in his '' Historia Naturalis'', repeats Aristotle's observations.

Swallow migration versus hibernation

Aristotle, however, suggested that swallows and other birds hibernated. This belief persisted as late as 1878 when

Aristotle, however, suggested that swallows and other birds hibernated. This belief persisted as late as 1878 when Elliott Coues

Elliott Ladd Coues (; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author. He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographic ...

listed the titles of no fewer than 182 papers dealing with the hibernation of swallows. Even the "highly observant" Gilbert White

Gilbert White FRS (18 July 1720 – 26 June 1793) was a " parson-naturalist", a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist, and ornithologist. He is best known for his ''Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne''.

Life

White was born on ...

, in his posthumously published 1789 ''The Natural History of Selborne

''The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne'', or just ''The Natural History of Selborne'' is a book by English parson-naturalist Gilbert White (1720–1793). It was first published in 1789 by his brother Benjamin. It has been continuou ...

'', quoted a man's story about swallows being found in a chalk cliff collapse "while he was a schoolboy at Brighthelmstone", though the man denied being an eyewitness. However, he writes that "as to swallows being found in a torpid state during the winter in the Isle of Wight or any part of this country, I never heard any such account worth attending to",White, 1898. pp. 27–28 and that if early swallows "happen to find frost and snow they immediately withdraw for a time—a circumstance this much more in favor of hiding than migration", since he doubts they would "return for a week or two to warmer latitudes".

It was not until the end of the eighteenth century that migration as an explanation for the winter disappearance of birds from northern climes was accepted. Thomas Bewick

Thomas Bewick (c. 11 August 17538 November 1828) was an English wood-engraver and natural history author. Early in his career he took on all kinds of work such as engraving cutlery, making the wood blocks for advertisements, and illustrating ch ...

's ''A History of British Birds

''A History of British Birds'' is a natural history book by Thomas Bewick, published in two volumes. Volume 1, ''Land Birds'', appeared in 1797. Volume 2, ''Water Birds'', appeared in 1804. A supplement was published in 1821. The text in ''Land ...

'' (Volume 1, 1797) mentions a report from "a very intelligent master of a vessel" who, "between the islands of Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

and Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Bal ...

, saw great numbers of Swallows flying northward", and states the situation in Britain as follows:

Bewick then describes an experiment that succeeded in keeping swallows alive in Britain for several years, where they remained warm and dry through the winters. He concludes:

Bewick then describes an experiment that succeeded in keeping swallows alive in Britain for several years, where they remained warm and dry through the winters. He concludes:

''Pfeilstörche''

In 1822, awhite stork

The white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'') is a large bird in the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its plumage is mainly white, with black on the bird's wings. Adults have long red legs and long pointed red beaks, and measure on average from beak tip to en ...

was found in the German state of Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label=Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwerin ...

with an arrow made from central African hardwood, which provided some of the earliest evidence of long-distance stork migration. This bird was referred to as a ''Pfeilstorch

(, ; plural , ) is a stork that gets injured by an arrow while wintering in Africa and returns to Europe with the arrow stuck in its body. As of 2003, about 25 ' have been documented in Germany.

The first and most famous ' was a white stork ...

'', German for "Arrow stork". Since then, around 25 ''Pfeilstörche'' have been documented.

General patterns

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or in only one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal area). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality. Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1,800 of the world's 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants.

Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or in only one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal area). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality. Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1,800 of the world's 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants.

Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

summer and returning in the autumn to wintering grounds in warmer regions to the south. Of course, in the southern hemisphere, the directions are reversed, but there is less land area in the far south to support long-distance migration.

The primary motivation for migration appears to be food; for example, some hummingbirds choose not to migrate if fed through the winter. In addition, the longer days of the northern summer provide extended time for breeding

Breeding is sexual reproduction that produces offspring, usually animals or plants. It can only occur between a male and a female animal or plant.

Breeding may refer to:

* Animal husbandry, through selected specimens such as dogs, horses, and rab ...

birds to feed their young. This helps diurnal birds to produce larger clutches

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). ...

than related non-migratory species that remain in the tropics. As the days shorten in autumn, the birds return to warmer regions where the available food supply varies little with the season.

These advantages offset the high stress, physical exertion costs, and other risks of the migration. Predation can be heightened during migration: Eleonora's falcon

Eleonora's falcon (''Falco eleonorae'') is a medium-sized falcon. It belongs to the hobby group, a rather close-knit number of similar falcons often considered a subgenus ''Hypotriorchis''. The sooty falcon is sometimes considered its closest re ...

''Falco eleonorae'', which breeds on Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

islands, has a very late breeding season, coordinated with the autumn passage of southbound passerine

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped'), which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by t ...

migrants, which it feeds to its young. A similar strategy is adopted by the greater noctule bat

The greater noctule bat (''Nyctalus lasiopterus'') is a rare carnivorous bat found in Europe, West Asia, and North Africa. It is the largest and least studied bat in Europe with a wingspan of up to and is one of the few bat species to feed on pa ...

, which preys on nocturnal passerine migrants. The higher concentrations of migrating birds at stopover sites make them prone to parasites and pathogens, which require a heightened immune response.

Within a species not all populations may be migratory; this is known as "partial migration". Partial migration is very common in the southern continents; in Australia, 44% of non-passerine birds and 32% of passerine species are partially migratory. In some species, the population at higher latitudes tends to be migratory and will often winter at lower latitude. The migrating birds bypass the latitudes where other populations may be sedentary, where suitable wintering habitats may already be occupied. This is an example of ''leap-frog migration''. Many fully migratory species show leap-frog migration (birds that nest at higher latitudes spend the winter at lower latitudes), and many show the alternative, chain migration, where populations 'slide' more evenly north and south without reversing the order.

Within a population, it is common for different ages and/or sexes to have different patterns of timing and distance. Female chaffinches ''Fringilla coelebs'' in Eastern Fennoscandia migrate earlier in the autumn than males do and the European tits of genera ''Parus

''Parus'' is a genus of Old World birds in the tit family. It was formerly a large genus containing most of the 50 odd species in the family Paridae. The genus was split into several resurrected genera following the publication of a detailed mo ...

'' and ''Cyanistes

''Cyanistes'' is a genus of birds in the tit family Paridae. The genus was at one time considered as a subgenus of Parus. In 2005 an article describing a molecular phylogenetic study that had examined mitochondrial DNA sequences from members ...

'' only migrate their first year.

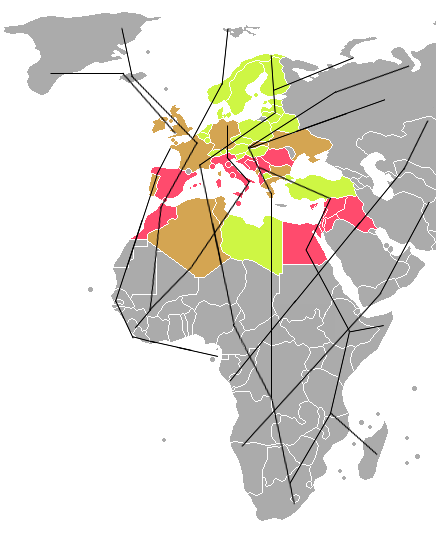

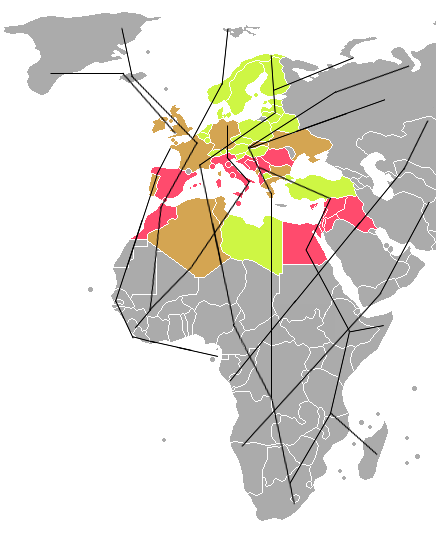

Most migrations begin with the birds starting off in a broad front. Often, this front narrows into one or more preferred routes termed flyway

A flyway is a flight path used by large numbers of birds while migrating between their breeding grounds and their overwintering quarters. Flyways generally span continents and often pass over oceans. Although applying to any species of migrati ...

s. These routes typically follow mountain ranges or coastlines, sometimes rivers, and may take advantage of updrafts and other wind patterns or avoid geographical barriers such as large stretches of open water. The specific routes may be genetically programmed or learned to varying degrees. The routes taken on forward and return migration are often different. A common pattern in North America is clockwise migration, where birds flying North tend to be further West, and flying South tend to shift Eastwards.

Many, if not most, birds migrate in flocks. For larger birds, flying in flocks reduces the energy cost. Geese in a V-formation may conserve 12–20% of the energy they would need to fly alone. Red knots ''Calidris canutus'' and dunlins ''Calidris alpina'' were found in radar studies to fly faster in flocks than when they were flying alone.

Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to

Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to Mt. Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is List of highest mountains on Earth, Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border ru ...

found skeletons of northern pintail

The pintail or northern pintail (''Anas acuta'') is a duck species with wide geographic distribution that breeds in the northern areas of Europe and across the Palearctic and North America. It is migratory and winters south of its breeding ra ...

''Anas acuta'' and black-tailed godwit

The black-tailed godwit (''Limosa limosa'') is a large, long-legged, long-billed shorebird first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is a member of the godwit genus, ''Limosa''. There are four subspecies, all with orange head, neck and chest ...

''Limosa limosa'' at on the Khumbu Glacier

The Khumbu Glacier ( ne, खुम्बु हिमनदी) is located in the Khumbu region of northeastern Nepal between Mount Everest and the Lhotse-Nuptse ridge. With elevations of at its terminus to at its source, it is the world's high ...

. Bar-headed geese

The bar-headed goose (''Anser indicus'') is a goose that breeds in Central Asia in colonies of thousands near mountain lakes and winters in South Asia, as far south as peninsular India. It lays three to eight eggs at a time in a ground nest. It ...

''Anser indicus'' have been recorded by GPS flying at up to while crossing the Himalayas, at the same time engaging in the highest rates of climb to altitude for any bird. Anecdotal reports of them flying much higher have yet to be corroborated with any direct evidence. Seabirds fly low over water but gain altitude when crossing land, and the reverse pattern is seen in landbirds. However most bird migration is in the range of . Bird strike

A bird strike—sometimes called birdstrike, bird ingestion (for an engine), bird hit, or bird aircraft strike hazard (BASH)—is a collision between an airborne animal (usually a bird or bat) and a moving vehicle, usually an aircraft. The term ...

aviation records from the United States show most collisions occur below and almost none above .

Bird migration is not limited to birds that can fly. Most species of penguin

Penguins (order (biology), order List of Sphenisciformes by population, Sphenisciformes , family (biology), family Spheniscidae ) are a group of Water bird, aquatic flightless birds. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: on ...

(Spheniscidae) migrate by swimming. These routes can cover over . Dusky grouse

The dusky grouse (''Dendragapus obscurus'') is a species of forest-dwelling grouse native to the Rocky Mountains in North America.del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'' 2: 401-402. Lynx Edi ...

''Dendragapus obscurus'' perform altitudinal migration mostly by walking. Emu

The emu () (''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is the second-tallest living bird after its ratite relative the ostrich. It is endemic to Australia where it is the largest native bird and the only extant member of the genus ''Dromaius''. The emu' ...

s ''Dromaius novaehollandiae'' in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

have been observed to undertake long-distance movements on foot during droughts.

Nocturnal migratory behavior

During nocturnal migration ("nocmig"), many birds give nocturnal flight calls, which are short, contact-type calls. These likely serve to maintain the composition of a migrating flock, and can sometimes encode the sex of a migrating individual, and to avoid collision in the air. Nocturnal migration can be monitored using weather radar data, allowing ornithologists to estimate the number of birds migrating on a given night, and the direction of the migration. Future research includes the automatic detection and identification of nocturnally calling migrant birds. Nocturnal migrants land in the morning and may feed for a few days before resuming their migration. These birds are referred to as ''passage migrants'' in the regions where they occur for a short period between the origin and destination. Nocturnal migrants minimize depredation, avoid overheating, and can feed during the day. One cost of nocturnal migration is the loss of sleep. Migrants may be able to alter their quality of sleep to compensate for the loss.Long-distance migration

The typical image of migration is of northern land birds, such asswallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae, are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

s (Hirundinidae) and birds of prey, making long flights to the tropics. However, many Holarctic wildfowl

The Anatidae are the biological family of water birds that includes ducks, geese, and swans. The family has a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all the world's continents except Antarctica. These birds are adapted for swimming, floating on ...

and finch

The true finches are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Fringillidae. Finches have stout conical bills adapted for eating seeds and nuts and often have colourful plumage. They occupy a great range of habitats where they are usua ...

(Fringillidae) species winters in the North Temperate Zone

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

, in regions with milder winters than their summer breeding grounds. For example, the pink-footed goose

The pink-footed goose (''Anser brachyrhynchus'') is a goose which breeds in eastern Greenland, Iceland and Svalbard. It is migratory, wintering in northwest Europe, especially Ireland, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and western Denmark. The nam ...

migrates from Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and neighbouring countries, whilst the dark-eyed junco

The dark-eyed junco (''Junco hyemalis'') is a species of junco, a group of small, grayish New World sparrows. This bird is common across much of temperate North America and in summer ranges far into the Arctic. It is a very variable species, much ...

migrates from subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of humid continental regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Scandinavia, Siberia, and the Cairngorms. Generally, ...

and arctic climates to the contiguous United States and the American goldfinch from taiga to wintering grounds extending from the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

northwestward to Western Oregon

Western Oregon is a geographical term that is generally taken to mean the part of the U.S. state of Oregon within of the Oregon Coast, on the west side of the crest of the Cascade Range. The term is applied somewhat loosely, however, and is somet ...

. Some ducks, such as the garganey

The garganey (''Spatula querquedula'') is a small dabbling duck. It breeds in much of Europe and across the Palearctic, but is strictly migratory, with the entire population moving to southern Africa, India (in particular Santragachi), Banglades ...

''Anas querquedula'', move completely or partially into the tropics. The European pied flycatcher

The European pied flycatcher (''Ficedula hypoleuca'') is a small passerine bird in the Old World flycatcher family. One of the four species of Western Palearctic black-and-white flycatchers, it bird hybrid, hybridizes to a limited extent with th ...

''Ficedula hypoleuca'' follows this migratory trend, breeding in Asia and Europe and wintering in Africa.

Migration routes and wintering grounds are both genetically and traditionally determined depending on the social system of the species. In long-lived, social species such as white stork

The white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'') is a large bird in the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its plumage is mainly white, with black on the bird's wings. Adults have long red legs and long pointed red beaks, and measure on average from beak tip to en ...

s ''(Ciconia ciconia),'' flocks are often led by the oldest members and young storks learn the route on their first journey. In short-lived species that migrate alone, such as the Eurasian blackcap

The Eurasian blackcap (''Sylvia atricapilla''), usually known simply as the blackcap, is a common and widespread typical warbler. It has mainly olive-grey upperparts and pale grey underparts, and differences between the five subspecies are sma ...

''Sylvia atricapilla'' or the yellow-billed cuckoo

The yellow-billed cuckoo (''Coccyzus americanus'') is a cuckoo. Common folk-names for this bird in the southern United States are rain crow and storm crow. These likely refer to the bird's habit of calling on hot days, often presaging rain or th ...

''Coccyzus americanus'', first-year migrants follow a genetically determined route that is alterable with selective breeding.

Many migration routes of long-distance migratory birds are circuitous due to evolutionary history: the breeding range of Northern wheatear

The northern wheatear or wheatear (''Oenanthe oenanthe'') is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family Turdidae, but is now more generally considered to be an Old World flycatcher, Muscicapidae. It is the ...

s ''Oenanthe oenanthe'' has expanded to cover the entire Northern Hemisphere, but the species still migrates up to 14,500 km to reach ancestral wintering grounds in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

rather than establish new wintering grounds closer to breeding areas.

A migration route often does not follow the most direct line between breeding and wintering grounds. Rather, it could follow a hooked or arched line, with detours around geographical barriers or towards suitable stopover habitat. For most land birds, such barriers could consist of large water bodies or high mountain ranges, a lack of stopover or feeding sites, or a lack of thermal column

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

s (important for broad-winged birds).

Conversely, in water-birds, large areas of land without wetlands offering suitable feeding sites may present a barrier, and detours avoiding such barriers are observed. For example, brent geese

The brant or brent goose (''Branta bernicla'') is a small goose of the genus ''Branta''. There are three subspecies, all of which winter along temperate-zone sea-coasts and breed on the high-Arctic tundra.

The Brent oilfield was named after ...

''Branta bernicla bernicla'' migrating between the Taymyr Peninsula

The Taymyr Peninsula (russian: Таймырский полуостров, Taymyrsky poluostrov) is a peninsula in the Far North of Russia, in the Siberian Federal District, that forms the northernmost part of the mainland of Eurasia. Administrati ...

and the Wadden Sea

The Wadden Sea ( nl, Waddenzee ; german: Wattenmeer; nds, Wattensee or ; da, Vadehavet; fy, Waadsee, longname=yes; frr, di Heef) is an intertidal zone in the southeastern part of the North Sea. It lies between the coast of northwestern conti ...

travel via low-lying coastal feeding-areas on the White Sea

The White Sea (russian: Белое море, ''Béloye móre''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, Сэрако ямʼ, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is su ...

and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

rather than directly across the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

and the Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

n mainland.

(breeding and wintering ranges with subspecies' flyway maps; diet)

Great snipe

The great snipe (''Gallinago media'') is a small stocky wader in the genus ''Gallinago''. This bird's breeding habitat is marshes and wet meadows with short vegetation in north-eastern Europe, including north-western Russia. Great snipes are mig ...

s make non-stop flights of 4,000–7,000 km, lasting 60–90 h, during which they change their average cruising heights from 2,000 m (above sea level) at night to around 4,000 m during daytime.

In waders

A similar situation occurs with

A similar situation occurs with wader

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

s (called ''shorebirds'' in North America). Many species, such as dunlin

The dunlin (''Calidris alpina'') is a small wader, formerly sometimes separated with the other "stints" in the genus ''Erolia''. The English name is a dialect form of "dunling", first recorded in 1531–1532. It derives from ''dun'', "dull brown ...

''Calidris alpina'' and western sandpiper

The western sandpiper (''Calidris mauri'') is a small shorebird. The genus name is from Ancient Greek ''kalidris'' or ''skalidris'', a term used by Aristotle for some grey-coloured waterside birds. The specific ''mauri'' commemorates Italian bota ...

''Calidris mauri'', undertake long movements from their Arctic breeding grounds to warmer locations in the same hemisphere, but others such as semipalmated sandpiper

The semipalmated sandpiper (''Calidris pusilla'') is a very small shorebird. The genus name is from Ancient Greek ''kalidris'' or ''skalidris'', a term used by Aristotle for some grey-coloured waterside birds. The specific ''pusilla'' is Latin fo ...

''C. pusilla'' travel longer distances to the tropics in the Southern Hemisphere.

For some species of waders, migration success depends on the availability of certain key food resources at stopover points along the migration route. This gives the migrants an opportunity to refuel for the next leg of the voyage. Some examples of important stopover locations are the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is the hi ...

and Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inlan ...

.

Some bar-tailed godwit

The bar-tailed godwit (''Limosa lapponica'') is a large and strongly migratory wader in the family Scolopacidae, which feeds on bristle-worms and shellfish on coastal mudflats and estuaries. It has distinctive red breeding plumage, long legs, an ...

s ''Limosa lapponica baueri'' have the longest known non-stop flight of any migrant, flying 11,000 km from Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

to their New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

non-breeding areas. Prior to migration, 55 percent of their bodyweight is stored as fat to fuel this uninterrupted journey.

In seabirds

Seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

migration is similar in pattern to those of the waders and waterfowl. Some, such as the black guillemot

The black guillemot or tystie (''Cepphus grylle'') is a medium-sized seabird of the Alcidae family, native throughout northern Atlantic coasts and eastern North American coasts. It is resident in much of its range, but large populations from the ...

''Cepphus grylle'' and some gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, m ...

s, are quite sedentary; others, such as most tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated as a subgroup of the family Laridae which includes gulls and skimmers and consists of e ...

s and auk

An auk or alcid is a bird of the family Alcidae in the order Charadriiformes. The alcid family includes the murres, guillemots, auklets, puffins, and murrelets. The word "auk" is derived from Icelandic ''álka'', from Old Norse ''alka'' (a ...

s breeding in the temperate northern hemisphere, move varying distances south in the northern winter. The Arctic tern

The Arctic tern (''Sterna paradisaea'') is a tern in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar breeding distribution covering the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe (as far south as Brittany), Asia, and North America (as far south a ...

''Sterna paradisaea'' has the longest-distance migration of any bird, and sees more daylight than any other, moving from its Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic non-breeding areas. One Arctic tern, ringed (banded) as a chick on the Farne Islands

The Farne Islands are a group of islands off the coast of Northumberland, England. The group has between 15 and 20 islands depending on the level of the tide.

off the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

east coast, reached Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

in just three months from fledging, a sea journey of over . Many tubenosed birds breed in the southern hemisphere and migrate north in the southern winter.

The most pelagic species, mainly in the 'tubenose' order Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are of ...

, are great wanderers, and the albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacifi ...

es of the southern oceans may circle the globe as they ride the "roaring forties" outside the breeding season. The tubenoses spread widely over large areas of open ocean, but congregate when food becomes available. Many are among the longest-distance migrants; sooty shearwater

The sooty shearwater (''Ardenna grisea'') is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. In New Zealand, it is also known by its Māori name , and as muttonbird, like its relatives the wedge-tailed shearwater (''A. pacificus' ...

s ''Puffinus griseus'' nesting on the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

migrate between the breeding colony and the North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

off Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. Some Manx shearwater

The Manx shearwater (''Puffinus puffinus'') is a medium-sized shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. The scientific name of this species records a name shift: Manx shearwaters were called Manks puffins in the 17th century. Puffin is an ...

s ''Puffinus puffinus'' do this same journey in reverse. As they are long-lived birds, they may cover enormous distances during their lives; one record-breaking Manx shearwater is calculated to have flown during its over-50-year lifespan.

Diurnal migration in large birds using thermals

Some large broad-winged birds rely on

Some large broad-winged birds rely on thermal

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

columns of rising hot air to enable them to soar. These include many birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

such as vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

s, eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

s, and buzzard

Buzzard is the common name of several species of birds of prey.

''Buteo'' species

* Archer's buzzard (''Buteo archeri'')

* Augur buzzard (''Buteo augur'')

* Broad-winged hawk (''Buteo platypterus'')

* Common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'')

* Eastern ...

s, but also stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

s. These birds migrate in the daytime. Migratory species in these groups have great difficulty crossing large bodies of water, since thermals only form over land, and these birds cannot maintain active flight for long distances. Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

and other seas present a major obstacle to soaring birds, which must cross at the narrowest points. Massive numbers of large raptors and storks pass through areas such as the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Se ...

, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, Falsterbo

Falsterbo (, outdatedly ) is a town located at the south-western tip of Sweden in Vellinge Municipality in Skåne. Falsterbo is situated in the southern part of the Falsterbo peninsula. It is part of Skanör med Falsterbo, one of Sweden's historica ...

, and the Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

at migration times. More common species, such as the European honey buzzard

The European honey buzzard (''Pernis apivorus''), also known as the pern or common pern, is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae.

Etymology

Despite its English name, this species is more closely related to kites of the genera '' Leptodon'' a ...

''Pernis apivorus'', can be counted in hundreds of thousands in autumn. Other barriers, such as mountain ranges, can cause funnelling, particularly of large diurnal migrants, as in the Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

n migratory bottleneck. The Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of th ...

bottleneck in the Caucasus is one of the heaviest migratory funnels on earth, created when hundreds of thousands of soaring birds avoid flying over the Black Sea surface and across high mountains. Birds of prey such as honey buzzards which migrate using thermals lose only 10 to 20% of their weight during migration, which may explain why they forage less during migration than do smaller birds of prey with more active flight such as falcons, hawks and harriers.

From observing the migration of eleven soaring bird species over the Strait of Gibraltar, species which did not advance their autumn migration dates were those with declining breeding populations in Europe.

Short-distance and altitudinal migration

Many long-distance migrants appear to be genetically programmed to respond to changing day length. Species that move short distances, however, may not need such a timing mechanism, instead moving in response to local weather conditions. Thus mountain and moorland breeders, such as

Many long-distance migrants appear to be genetically programmed to respond to changing day length. Species that move short distances, however, may not need such a timing mechanism, instead moving in response to local weather conditions. Thus mountain and moorland breeders, such as wallcreeper

The wallcreeper (''Tichodroma muraria'') is a small passerine bird found throughout the high mountains of the Palearctic from southern Europe to central China. It is the only extant member of both the genus ''Tichodroma'' and the family Tichodro ...

''Tichodroma muraria'' and white-throated dipper

The white-throated dipper (''Cinclus cinclus''), also known as the European dipper or just dipper, is an aquatic passerine bird found in Europe, Middle East, Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent. The species is divided into several subspecies ...

''Cinclus cinclus'', may move only altitudinally to escape the cold higher ground. Other species such as merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

''Falco columbarius'' and Eurasian skylark

The Eurasian skylark (''Alauda arvensis'') is a passerine bird in the lark family, Alaudidae. It is a widespread species found across Europe and the Palearctic with introduced populations in New Zealand, Australia and on the Hawaiian Islands. ...

''Alauda arvensis'' move further, to the coast or towards the south. Species like the chaffinch are much less migratory in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

than those of continental Europe, mostly not moving more than 5 km in their lives.

Short-distance passerine migrants have two evolutionary origins. Those that have long-distance migrants in the same family, such as the common chiffchaff

The common chiffchaff (''Phylloscopus collybita''), or simply the chiffchaff, is a common and widespread leaf warbler which breeds in open woodlands throughout northern and temperate Europe and the Palearctic.

It is a migratory passerine which ...

''Phylloscopus collybita'', are species of southern hemisphere origins that have progressively shortened their return migration to stay in the northern hemisphere.

Species that have no long-distance migratory relatives, such as the waxwing

The waxwings are three species of passerine birds classified in the genus ''Bombycilla''. They are pinkish-brown and pale grey with distinctive smooth plumage in which many body feathers are not individually visible, a black and white eyestripe, ...

s ''Bombycilla'', are effectively moving in response to winter weather and the loss of their usual winter food, rather than enhanced breeding opportunities.Cocker, 2005. p. 326

In the tropics there is little variation in the length of day throughout the year, and it is always warm enough for a food supply, but altitudinal migration occurs in some tropical birds. There is evidence that this enables the migrants to obtain more of their preferred foods such as fruits.

Altitudinal migration is common on mountains worldwide, such as in the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

and the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

. Dusky grouse

The dusky grouse (''Dendragapus obscurus'') is a species of forest-dwelling grouse native to the Rocky Mountains in North America.del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'' 2: 401-402. Lynx Edi ...

in Colorado migrate less than a kilometer away from their summer grounds to winter sites which may be higher or lower by about 400 m in altitude than the summer sites.

Many bird species in arid regions across southern Australia are nomadic; they follow water and food supply around the country in an irregular pattern, unrelated to season but related to rainfall. Several years may pass between visits to an area by a particular species.

Irruptions and dispersal

Sometimes circumstances such as a good breeding season followed by a food source failure the following year lead to irruptions in which large numbers of a species move far beyond the normal range.

Sometimes circumstances such as a good breeding season followed by a food source failure the following year lead to irruptions in which large numbers of a species move far beyond the normal range. Bohemian waxwing

The Bohemian waxwing (''Bombycilla garrulus'') is a starling-sized passerine bird that breeds in the northern forests of the Palearctic and North America. It has mainly buff-grey plumage, black face markings and a pointed crest. Its wings are ...

s ''Bombycilla garrulus'' well show this unpredictable variation in annual numbers, with five major arrivals in Britain during the nineteenth century, but 18 between the years 1937 and 2000. Red crossbill

The red crossbill or common crossbill (''Loxia curvirostra'') is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. Crossbills have distinctive mandibles, crossed at the tips, which enable them to extract seeds from conifer cones and other ...

s ''Loxia curvirostra'' too are irruptive, with widespread invasions across England noted in 1251, 1593, 1757, and 1791.

Bird migration is primarily, but not entirely, a Northern Hemisphere phenomenon.

This is because continental landmasses of the northern hemisphere are almost entirely temperate and subject to winter food shortages driving bird populations south (including the Southern Hemisphere) to overwinter; In contrast, among (pelagic) seabirds, species of the Southern Hemisphere are more likely to migrate. This is because there is a large area of ocean in the Southern Hemisphere, and more islands suitable for seabirds to nest.

Physiology and control

The control of migration, its timing and response are genetically controlled and appear to be a primitive trait that is present even in non-migratory species of birds. The ability to navigate and orient themselves during migration is a much more complex phenomenon that may include both endogenous programs as well as learning.Timing

The primary physiological cue for migration is the changes in the day length. These changes are related to hormonal changes in the birds. In the period before migration, many birds display higher activity orZugunruhe

''Zugunruhe'' ( /ˈ tsuːk:ʊnʁuːə/; German: suːk:ʊnʁuːə; lit. 'migration-anxiety') is the experience of migratory restlessness.

Ethology

In ethology, ''Zugunruhe'' describes anxious behavior in migratory animals, especially in bird ...

( de , migratory restlessness), first described by Johann Friedrich Naumann

Johann Friedrich Naumann (14 February 1780 – 15 August 1857) was a German scientist, engraver, and editor. He is regarded as the founder of scientific ornithology in Europe. He published ''The Natural History of German Birds'' (1820–1844) a ...

in 1795, as well as physiological changes such as increased fat deposition. The occurrence of Zugunruhe even in cage-raised birds with no environmental cues (e.g. shortening of day and falling temperature) has pointed to the role of circannual endogenous

Endogenous substances and processes are those that originate from within a living system such as an organism, tissue, or cell.

In contrast, exogenous substances and processes are those that originate from outside of an organism.

For example, es ...

programs in controlling bird migrations. Caged birds display a preferential flight direction that corresponds with the migratory direction they would take in nature, changing their preferential direction at roughly the same time their wild conspecifics change course.

Satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotope ...

tracking of 48 individual Asian houbaras (''Chlamydotis macqueenii

MacQueen's bustard (''Chlamydotis macqueenii'') is a large bird in the bustard family. It is native to the desert and steppe regions of Asia, west from the Sinai Peninsula extending across Kazakhstan east to Mongolia. In the 19th century, vagran ...

'') across multiple migrations showed that this species uses the local temperature to time their spring migration departure. Notably, departure responses to temperature varied between individuals but were individually repeatable (when tracked over multiple years). This suggests that individual use of temperature is a cue that allows for population-level adaptation to climate change

Climate change adaptation is the process of adjusting to current or expected effects of climate change.IPCC, 2022Annex II: Glossary öller, V., R. van Diemen, J.B.R. Matthews, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, J.S. Fuglestvedt, A. Reisinger (eds.) InClimat ...

. In other words, in a warming world, many migratory birds are predicted to depart earlier in the year for their summer or winter destination.

In polygynous

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

species with considerable sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, males tend to return earlier to the breeding sites than their females. This is termed protandry.

Orientation and navigation

Navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

is based on a variety of senses. Many birds have been shown to use a sun compass. Using the sun for direction involves the need for making compensation based on the time. Navigation has been shown to be based on a combination of other abilities including the ability to detect magnetic fields (magnetoreception

Magnetoreception is a sense which allows an organism to detect the Earth's magnetic field. Animals with this sense include some arthropods, molluscs, and vertebrates (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, though not humans). The se ...

), use visual landmarks as well as olfactory cues.

Long-distance migrants are believed to disperse as young birds and form attachments to potential breeding sites and to favourite wintering sites. Once the site attachment is made they show high site-fidelity, visiting the same wintering sites year after year.

The ability of birds to navigate during migrations cannot be fully explained by endogenous programming, even with the help of responses to environmental cues. The ability to successfully perform long-distance migrations can probably only be fully explained with an accounting for the cognitive ability of the birds to recognize habitats and form mental maps. Satellite tracking

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

of day migrating raptors such as ospreys and honey buzzards has shown that older individuals are better at making corrections for wind drift. Birds rely for navigation on a combination of innate biological senses and experience, as with the two electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

tools that they use. A young bird on its first migration flies in the correct direction according to the Earth's magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

, but does not know how far the journey will be. It does this through a radical pair mechanism CIDNP (chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization), often pronounced like "kidnip", is a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technique that is used to study chemical reactions that involve radicals. It detects the non-Boltzmann (non-thermal) nuc ...

whereby chemical reactions in special photo pigments sensitive to short wavelengths are affected by the field. Although this only works during daylight hours, it does not use the position of the sun in any way. At this stage the bird is in the position of a Boy Scout

A Scout (in some countries a Boy Scout, Girl Scout, or Pathfinder) is a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement. Because of the large age and development span, many Scouting associations have split ...

with a compass but no map, until it grows accustomed to the journey and can put its other capabilities to use. With experience it learns various landmarks and this "mapping" is done by magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

s in the trigeminal system

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve ( lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing; ...

, which tell the bird how strong the field is. Because birds migrate between northern and southern regions, the magnetic field strengths at different latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

s let it interpret the radical pair mechanism more accurately and let it know when it has reached its destination. There is a neural connection between the eye and "Cluster N", the part of the forebrain that is active during migrational orientation, suggesting that birds may actually be able to ''see'' the magnetic field of the earth.

Vagrancy

Migrating birds can lose their way and appear outside their normal ranges. This can be due to flying past their destinations as in the "spring overshoot" in which birds returning to their breeding areas overshoot and end up further north than intended. Certain areas, because of their location, have become famous as watchpoints for such birds. Examples are thePoint Pelee National Park

Point Pelee National Park (; french: Parc national de la Pointe-Pelée) is a national park in Essex County in southwestern Ontario, Canada where it extends into Lake Erie. The word is French for 'bald'. Point Pelee consists of a peninsula of la ...

in Canada, and Spurn

Spurn is a narrow sand tidal island located off the tip of the coast of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England that reaches into the North Sea and forms the north bank of the mouth of the Humber Estuary. It was a spit with a semi-permanent co ...

in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

.

Reverse migration, where the genetic programming of young birds fails to work properly, can lead to rarities turning up as vagrants thousands of kilometres out of range.

Drift migration Drift migration is the phenomenon in which migrating birds are blown off course by the winds while they are in flight. It is more likely to happen to birds heading south in autumn because the large numbers of inexperienced young birds are less abl ...

of birds blown off course by the wind can result in "falls" of large numbers of migrants at coastal sites.

A related phenomenon called "abmigration" involves birds from one region joining similar birds from a different breeding region in the common winter grounds and then migrating back along with the new population. This is especially common in some waterfowl, which shift from one flyway to another.

Migration conditioning