Michael Norman Manley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Michael Norman Manley (10 December 1924 – 6 March 1997) was a

"Queen, emperor and republican status"

''

Manley developed close friendships with several communist and socialist leaders, foremost of whom were

Manley developed close friendships with several communist and socialist leaders, foremost of whom were

Order of Merit of Jamaica (O.M.)

*1994:

Order of Merit of Jamaica (O.M.)

*1994:

Michael Norman Manley

''The Word Is Love: Jamaica's Michael Manley'' – documentary on the life and career of Michael Manley

{{DEFAULTSORT:Manley, Michael 1924 births 1997 deaths Prime Ministers of Jamaica Alumni of the London School of Economics Jamaican people of English descent Jamaican people of Irish descent Jamaican socialists Royal Canadian Air Force personnel of World War II Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Jamaican members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Columbia University faculty Deaths from cancer in Jamaica Deaths from prostate cancer People's National Party (Jamaica) politicians North American democratic socialists Recipients of the Order of the Nation Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica) Children of national leaders

Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

n politician who served as the fourth Prime Minister of Jamaica

The prime minister of Jamaica is Jamaica's head of government, currently Andrew Holness. Holness, as leader of the governing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), was sworn in as prime minister on 7 September 2020, having been re-elected as a result of ...

from 1972 to 1980 and from 1989 to 1992. Manley championed a democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within a ...

program, and has been described as a populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

. According to opinion polls, he remains one of Jamaica's most popular prime ministers.

Early life

Michael Manley was the second son of premierNorman Washington Manley

Norman Washington Manley (4 July 1893 – 2 September 1969) was a Jamaican statesman who served as the first and only Premier of Jamaica. A Rhodes Scholar, Manley became one of Jamaica's leading lawyers in the 1920s. Manley was an advocate ...

and artist Edna Manley

Edna Swithenbank Manley, Jamaican Order of Merit, OM (28 February 1900 – 2 February 1987) is considered one of the most important artists and arts educators in Jamaica. She was known primarily as a sculptor although her oeuvre included signi ...

. He studied at Jamaica College

Jamaica College (abbreviated J.C. or JC) is a public, Christian, secondary school and sixth form for boys in Kingston, Jamaica. It was established in 1789 by Charles Drax, who was the grand-nephew of wealthy Barbadian sugar planter J ...

between 1935 and 1943. He attended the Antigua State College and then served in the Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. In 1945, he enrolled at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 millio ...

. At the LSE, he was influenced by Fabian socialism

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

and the writings of Harold Laski

Harold Joseph Laski (30 June 1893 – 24 March 1950) was an English political theorist and economist. He was active in politics and served as the chairman of the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946 and was a professor at the London School of ...

. He graduated in 1949, and returned to Jamaica to serve as an editor and columnist for the newspaper ''Public Opinion''. At about the same time, he became involved in the trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

movement, becoming a negotiator for the National Workers Union. In August 1953, he became a full-time official of that union.

Entry into politics

When his father was elected premier of Jamaica in 1955, Manley resisted entering politics, not wanting to be seen as capitalizing on his family name. However, in 1962, he accepted an appointment to the Senate of theParliament of Jamaica

The Parliament of Jamaica is the legislative branch of the government of Jamaica. It consists of three elements: The Crown (represented by the Governor-General), the appointed Senate and the directly elected House of Representatives.

The Se ...

. He won election to the Jamaican House of Representatives for the Central Kingston constituency in 1967.

After his father's retirement in 1969, Manley was elected leader of the People's National Party

The People's National Party (PNP) is a Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Jamaica, political party in Jamaica, founded in 1938 by independence campaigner Osmond Theodore Fairclough. It holds 14 of the 63 seats in ...

, defeating Vivian Blake

Vivian Blake (11 May 1956 – 21 March 2010) was a Jamaican drug kingpin who founded and operated the American operations of the Jamaican Shower Posse.

Background

Blake was born to a poor family in West Kingston, but was granted a scholars ...

. He then served as leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, until his party won in the general elections of 1972.

Domestic reforms

In the 1972 Jamaican general election, Manley defeated the unpopular incumbent Prime Minister,Hugh Shearer

Hugh Lawson Shearer (18 May 1923 – 15 July 2004) was a Jamaican trade unionist and politician, who served as the 3rd Prime Minister of Jamaica, from 1967 to 1972.

Biography

Early life

Born in Trelawny Parish, Jamaica, near the sugar an ...

of the Jamaica Labour Party

The Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) is one of the two major political parties in Jamaica, the other being the People's National Party (PNP). While its name might suggest that it is a social democratic party (as is the case for "Labour" parties in seve ...

, as his People's National Party swept to a landslide victory with 37 of 53 seats.

He instituted a series of socio-economic reforms that produced mixed results. Although he was a Jamaican from an elite family, Manley's successful trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

background helped him to maintain a close relationship with the country's poor majority, and he was a dynamic, popular leader. Unlike his father, who had a reputation for being formal and businesslike, the younger Manley moved easily among people of all strata and made Parliament accessible to the people by abolishing the requirement for men to wear jacket

A jacket is a garment for the upper body, usually extending below the hips. A jacket typically has sleeves, and fastens in the front or slightly on the side. A jacket is generally lighter, tighter-fitting, and less insulating than a coat, which ...

s and ties TIES may refer to:

* TIES, Teacher Institute for Evolutionary Science

* TIES, The Interactive Encyclopedia System

* TIES, Time Independent Escape Sequence

* Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science

The ''Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science' ...

to its sittings. In this regard he started a fashion revolution, often preferring the Kariba suit

A Kariba or Kareeba suit is a two-piece suit for men created by Jamaican designer Ivy Ralph, mother of Sheryl Lee Ralph, in the early 1970s to be worn on business and formal occasions as a Caribbean replacement for the European-style suit and ...

, a type of formal bush-jacket suit with trousers and worn without a shirt and tie.

Under Manley, Jamaica established a minimum wage for all workers, including domestic workers. In 1974, the PNP under Manley adopted a political philosophy of Democratic Socialism.

In 1974, Manley proposed free education from primary school to university. The introduction of universally free secondary education was a major step in removing the institutional barriers to private sector and preferred government jobs that required secondary diplomas. The PNP government in 1974 also formed the Jamaica Movement for the Advancement of Literacy (JAMAL), which administered adult education programs with the goal of involving 100,000 adults a year.

Land reform expanded under his administration. Historically, land tenure in Jamaica has been rather inequitable. Project Land Lease (introduced in 1973), attempted an integrated rural development approach, providing tens of thousands of small farmers with land, technical advice, inputs such as fertilizers, and access to credit. An estimated 14 percent of idle land was redistributed through this program, much of which had been abandoned during the post-war urban migration or purchased by large bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

companies.

The minimum voting age was lowered to 18 years, while equal pay for women was introduced.''Insight Guide: Jamaica'', Insight Guides, APA Publications, 2009. Maternity leave was also introduced, while the government outlawed the stigma of illegitimacy. The Masters and Servants Act was abolished, and a Labour Relations and Industrial Disputes Act provided workers and their trade unions with enhanced rights. The National Housing Trust was established, providing "the means for most employed people to own their own homes," and greatly stimulated housing construction, with more than 40,000 houses built between 1974 and 1980.

Subsidised meals, transportation and uniforms for schoolchildren from disadvantaged backgrounds were introduced, together with free education at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.Stewart, Chuck, ''The Greenwood Encyclopaedia of LGBT Issues Worldwide'', Volume 1. Special employment programmes were also launched,Kari Levitt, ''Reclaiming Development: independent thought and Caribbean community''. together with programmes designed to combat illiteracy. Increases in pensions and poor relief were carried out,Michael Kaufman, ''Jamaica under Manley: dilemmas of socialism and democracy''. along with a reform of local government taxation, an increase in youth training, an expansion of day care centres. and an upgrading of hospitals.Rose, Euclid A., ''Dependency and Socialism in the Modern Caribbean: Superpower Intervention in Guyana, Jamaica and Grenada, 1970–1985''.

A worker's participation programme was introduced,Panton, David, ''Jamaica’s Michael Manley: The Great Transformation (1972–92)''. together with a new mental health lawLevi, Darrell E., ''Michael Manley: the making of a leader''. and the family court. Free health care for all Jamaicans was introduced, while health clinics and a paramedical system in rural areas were established. Various clinics were also set up to facilitate access to medical drugs. Spending on education was significantly increased, while the number of doctors and dentists in the country rose. Project Lend Lease, an agricultural programme designed to provide rural labourers and smallholders with more land through tenancy, was introduced, together with a National Youth Service Programme for high school graduates to teach in schools, vocational training, and the literacy programme, comprehensive rent and price controls, protection for workers against unfair dismissal, subsidies (in 1973) on basic food items, and the automatic recognition of unions in the workplace.

Manley was the first Jamaican prime minister to support Jamaican republicanism (the replacement of the constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

with a republic). In 1975, his government established a commission into constitutional reform, which recommended that Jamaica become a republic. In July 1977, after a march to commemorate the Morant Bay rebellion

The Morant Bay Rebellion (11 October 1865) began with a protest march to the courthouse by hundreds of people led by preacher Paul Bogle in Morant Bay, Jamaica. Some were armed with sticks and stones. After seven men were shot and killed by th ...

, Manley announced that Jamaica would become a republic by 1981. This did not occur, however.Burke, Michael (21 April 2016)"Queen, emperor and republican status"

''

The Jamaica Observer

''Jamaica Observer'' is a daily newspaper published in Kingston, Jamaica. The publication is owned by Butch Stewart, who chartered the paper in January 1993 as a competitor to Jamaica's oldest daily paper, ''The Gleaner''. Its founding editor is ...

''. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

Diplomacy

Manley developed close friendships with several communist and socialist leaders, foremost of whom were

Manley developed close friendships with several communist and socialist leaders, foremost of whom were Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, aft ...

of Tanzania, Olof Palme

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (; ; 30 January 1927 – 28 February 1986) was a Swedish politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 1969 to 1976 and 1982 to 1986. Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 until h ...

of Sweden, and Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

of Cuba. With Cuba just north of Jamaica, he strengthened diplomatic relations between the two island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

nations, much to the dismay of United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

policymakers.

Manley expressed support for anti-colonial African movements such as the MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social d ...

during the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war was ...

, where the MPLA successfully fought off, with Cuban military help, the rival UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

movement, which was backed by apartheid South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and the US. The US labelled Jamaican support for the MPLA as "hostile", and the US government was critical of the Manley government for their close relationship with Fidel Castro's Cuba. When Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

visited Jamaica in 1975, he warned Manley against supporting the MPLA and Cuba. More broadly there was a deterioration of relations between the United States and Jamaica during Manley's tenure beginning with the Nixon administration and continuing on with the Ford Administration due to allegations of CIA activities on the island. Attempts at an improvement of relations were made during the Carter Administration.

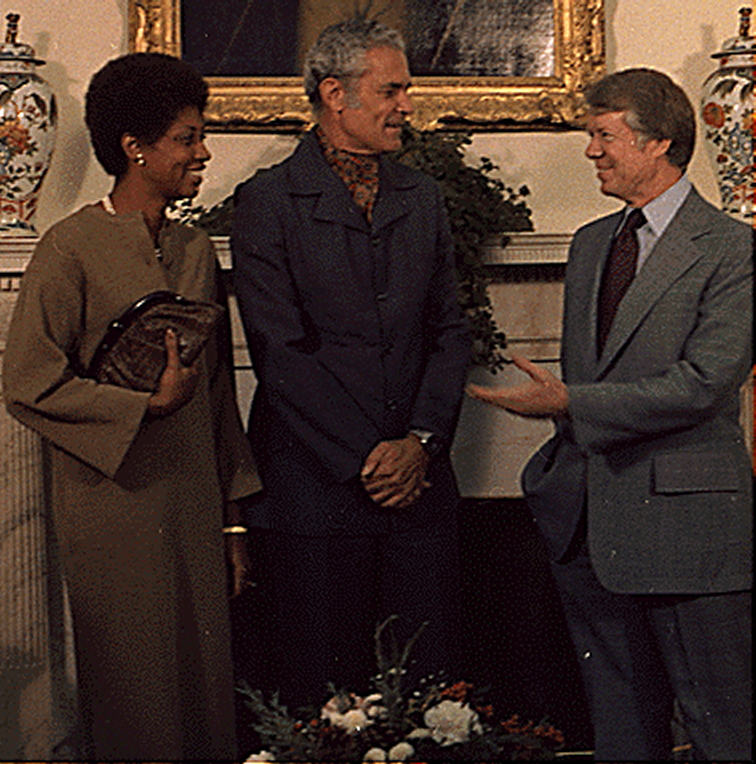

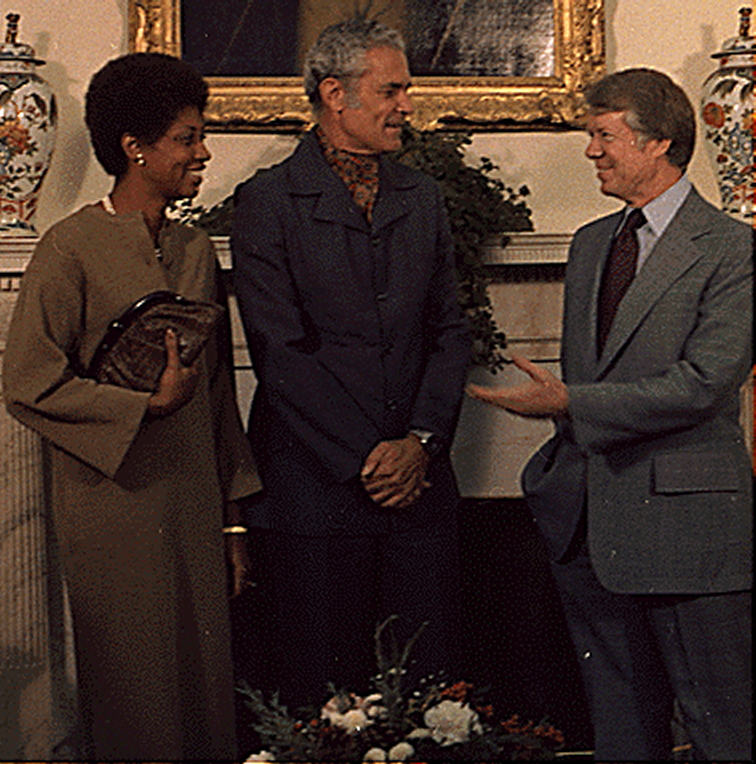

In December 1977, Manley visited President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

at the White House to remedy the situation. Details of the meeting, however, were never disclosed.

In a speech given at the 1979 meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

, Manley strongly pressed for the development of what was called a natural alliance between the Non-Aligned movement and the Soviet Union to battle imperialism: "All anti-imperialists know that the balance of forces in the world shifted irrevocably in 1917 when there was a movement and a man in the October Revolution, and Lenin was the man." Despite some international opposition, Manley deepened and strengthened Jamaica's ties with Cuba.

In diplomatic affairs, Manley believed in respecting the different systems of government of other countries and not interfering in their internal affairs.

Violence

Manley was Prime Minister when Jamaica experienced a significant escalation of its political culture of violence. Supporters of his opponentEdward Seaga

Edward Philip George Seaga ( or ; 28 May 1930 – 28 May 2019) was a Jamaican politician. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Jamaica, from 1980 to 1989, and the leader of the Jamaica Labour Party from 1974 to 2005.Jamaica Labour Party

The Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) is one of the two major political parties in Jamaica, the other being the People's National Party (PNP). While its name might suggest that it is a social democratic party (as is the case for "Labour" parties in seve ...

(JLP) and Manley's People's National Party

The People's National Party (PNP) is a Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Jamaica, political party in Jamaica, founded in 1938 by independence campaigner Osmond Theodore Fairclough. It holds 14 of the 63 seats in ...

(PNP) engaged in a bloody struggle which began before the 1976 election and ended when Seaga was installed as Prime Minister in 1980. While the violent political culture was not invented by Seaga or Manley, and had its roots in conflicts between the parties from as early as the beginning of the two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually referre ...

in the 1940s, political violence reached unprecedented levels in the 1970s. Indeed, the two elections accompanied by the greatest violence were those (1976 and 1980) in which Seaga was trying to unseat Manley.

In response to a wave of killings in 1974, Manley oversaw the passage of the Gun Court

The Gun Court is the branch of the Jamaican judicial system that tries criminal cases involving firearms. The court was established by Parliament in 1974 to combat rising gun violence, and empowered to try suspects ''in camera'', without a jury ...

Act and the Suppression of Crime Act, giving the police and the army new powers to seal off and disarm high-violence neighborhoods. The Gun Court imposed a mandatory sentence of indefinite imprisonment with hard labour for all firearms offences, and ordinarily tried cases ''in camera

''In camera'' (; Latin: "in a chamber"). is a legal term that means ''in private''. The same meaning is sometimes expressed in the English equivalent: ''in chambers''. Generally, ''in-camera'' describes court cases, parts of it, or process wh ...

'', without a jury. Manley declared that "There is no place in this society for the gun, now or ever."

Violence flared in January 1976 in anticipation of elections. A state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

was declared by Manley's party the PNP in June and 500 people, including some prominent members of the JLP, were accused of trying to overthrow the government and were detained, without charges, in the South Camp Prison at the Up-Park Camp

Up-Park Camp (often Up Park Camp) was the headquarters of the British Army in Jamaica from the late 18th century to independence in 1962. From that date, it has been the headquarters of the Jamaica Defence Force. It is located in the heart ...

military headquarters.''The Daily Gleaner'', Monday, 6 July 1986, p. 14. Elections were held on 15 December in the 1976 Jamaican general election

General elections were held in Jamaica on 15 December 1976. Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p430 The result was a victory for the People's National Party, which won 47 of the 60 seats. Voter turnout ...

, while the state of emergency was still in effect. The PNP was returned to office, winning 47 seats to the JLP's 13. The turnout was a very high 85 percent.Nohlen, Dieter (2005), ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook'', Volume I, p. 430.

The state of emergency continued into the next year. Extraordinary powers granted the police by the Suppression of Crime Act of 1974 continued to the end of the 1990s.

Violence continued to blight political life in the 1970s. Gangs armed by both parties fought for control of urban constituencies. In the election year of 1980 over 800 Jamaicans were killed. Jamaicans were particularly shocked by the violence at that time.

In the 1980 Jamaican general election

General elections were held in Jamaica on 30 October 1980.Dieter Nohlen (2005) ''Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I'', p430 The balance of power in the 60-seat Jamaican House of Representatives was dramatically-shifted. Prior t ...

, Seaga's JLP won 51 of the 60 seats, and he became Prime Minister.

Opposition

AsLeader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

Manley became an outspoken critic of the new conservative administration. He strongly opposed intervention in Grenada after Prime Minister Maurice Bishop

Maurice Rupert Bishop (29 May 1944 – 19 October 1983) was a Grenadian revolutionary and the leader of New Jewel Movement – a Marxist–Leninist party which sought to prioritise socio-economic development, education, and black liberation ...

was overthrown and executed. Immediately after committing Jamaican troops to Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

in 1983, Seaga called a snap election – two years early – on the pretext that Dr Paul Robertson, General Secretary of the PNP, had called for his resignation. Manley, who may have been taken by surprise by the maneuver, led his party in a boycott of the elections, and so the Jamaica Labour Party won all seats in parliament against only marginal opposition in six of the sixty electoral constituencies.

During his period of opposition in the 1980s, Manley, a compelling speaker, travelled extensively, speaking to audiences around the world. He taught a graduate seminar and gave a series of public lectures at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

In 1986, Manley travelled to Britain and visited Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

. He attended a number of venues including the Afro Caribbean Resource Centre in Winson Green

Winson Green is a loosely defined inner-city area in the west of the city of Birmingham, England. It is part of the ward of Soho.

It is the location of HM Prison Birmingham (known locally as Winson Green Prison or "the Green") and of City Hospi ...

and Digbeth Civic Hall. The mainly black audiences turned out ''en masse'' to hear Manley speak.

Seaga's failure to deliver on his promises to the US and foreign investors, as well as complaints of governmental incompetence in the wake Hurricane Gilbert

Hurricane Gilbert was the second most intense tropical cyclone on record in the Atlantic basin in terms of barometric pressure, only behind Hurricane Wilma in 2005. An extremely powerful tropical cyclone that formed during the 1988 Atlantic hurr ...

's devastation in 1988, contributed to his defeat in the 1989 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1989.

Africa

* 1989 Beninese parliamentary election

* 1989 Botswana general election

* 1989 Equatorial Guinean presidential election

* 1989 People's Republic of the Congo parliamentary election

* ...

. The PNP won 45 seats to the JLP's 15.

Re-election

By 1989, some right-wing critics had begun to assert that Manley had softened hissocialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

rhetoric, explicitly advocating a role for private enterprise

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in the respective listed markets, but rather the company's stock is ...

. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he also supposedly ceased his support for a variety of international causes. In the election of that year he campaigned on what appeared to be a more moderate platform. Seaga's Government had fallen out of favour – both with the electorate and the US – and the PNP was elected.

Manley's second term focused on liberalizing Jamaica's economy, with the pursuit of a neoliberal programme that stood in marked contrast to the more social democratic economic policies pursued by Manley's first government. Various measures were, however, undertaken to cushion the negative effects of austerity and structural adjustment. A Social Support Programme was introduced to provide welfare assistance for poor Jamaicans. In addition, the programme focused on creating direct employment, training, and credit for much of the population.

The government also announced a 50% increase in the amount of nutritional assistance for the most vulnerable groups (including pregnant women, nursing mothers, and children). A small number of community councils were also created. In addition, a limited land reform programme was carried out that leased and sold land to small farmers, and land plots were granted to hundreds of farmers. The government had an admirable record in housing provision, while measures were also taken to protect consumers from illegal and unfair business practices.

In 1992, citing health reasons, Manley stepped down as Prime Minister and PNP leader. His former Deputy Prime Minister, P. J. Patterson, assumed both offices.

Family

Manley was married five times. In 1946, he married Jacqueline Kamellard, but the marriage was dissolved in 1951. In 1955 he married Thelma Verity the adopted daughter of Sir Philip Sherlock OM and his wife Grace Verity; in 1960, this marriage was also dissolved. In 1966, Manley married Barbara Lewars (died in 1968); in 1972, he married Beverley Anderson, but the marriage was dissolved in 1990. Beverley wrote ''The Manley Memoirs'' in June 2008. Michael Manley's final marriage was to Glynne Ewart in 1992. Manley had five children from his five marriages: Rachel Manley, Joseph Manley, Sarah Manley, Natasha Manley, and David Manley.Retirement and death

Manley wrote seven books, including the award-winning ''A History of West Indies Cricket'', in which he discussed the links between cricket and West Indiannationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

. The other books he wrote include ''The Politics of Change'' (1974), ''A Voice in the Workplace'' (1975), ''The Search for Solutions, The Poverty of Nations, Up the Down Escalator, and Jamaica: Struggle in the Periphery''.

On 6 March 1997, Michael Manley died of prostate cancer, the same day as another Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

politician, Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Berret Jagan (22 March 1918 – 6 March 1997) was a Guyanese politician and dentist who was first elected Chief Minister in 1953 and later Premier of British Guiana from 1961 to 1964. He later served as President of Guyana from 199 ...

of Guyana. He is interred at the National Heroes Park

National Heroes Park (formerly King George VI Memorial Park) is a botanical garden in Kingston, Jamaica. The largest open space in Kingston at 50 acres in size,

, where his father Norman Manley is also interred. Photographer Maria LaYacona Maria LaYacona (1926–2019) was an American-born photographer who worked primarily in Jamaica. For its first three decades, she was the official photographer for the country's National Dance Theatre Company.

Early life

LaYacona's parents emigrated ...

's portrait of Manley appears on the Jamaican $1,000 note.

Honours

*1973:

Order of the Liberator

The Order of the Liberator was the highest distinction of Venezuela and was appointed for services to the country, outstanding merit and benefits made to the community. For Venezuelans the order ranks first in the order of precedence from other or ...

, Venezuela

*1976:

Order of José Martí

The Order José Martí (Orden José Martí) is a state honor in Cuba. The Order was named so after José Martí, the national hero of Cuba. The design was realized by the Cuban sculptor José Delarra.

Notable recipients

* Alexander Lukashenko, ...

*1978: United Nations Medal

A United Nations Medal is an international decoration

An international decoration is a military award which is not bestowed by a particular country, but rather by an international organization such as the United Nations or NATO. Such awards ar ...

*1989: Member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom (P.C.)

*1992:  Order of Merit of Jamaica (O.M.)

*1994:

Order of Merit of Jamaica (O.M.)

*1994: Order of the Caribbean Community

The Order of the Caribbean Community is an award given to

The award was initiated at the Eighth (8th) Conference of Heads of State and Governments of CARICOM in 1987 and began bestowal in 1992. Decisions as to award are taken by the Advisory Co ...

(O.O.C.)

Posthumously:

*

Order of the Nation

The Order of the Nation is a Jamaican honour. It is a part of the Jamaican honours system and was instituted in 1973 as the second-highest honour in the country, with the Order of National Hero being the highest honour.

The Order of the Nation ...

(O.N.)

References

Bibliography

* Henke, Holger (2000). ''Between Self-Determination and Dependency: Jamaica's foreign relations, 1972–1989''. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2000. * Levi, Darrell E. (1990). ''Michael Manley: the making of a leader''. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990.External links

*Michael Norman Manley

''The Word Is Love: Jamaica's Michael Manley'' – documentary on the life and career of Michael Manley

{{DEFAULTSORT:Manley, Michael 1924 births 1997 deaths Prime Ministers of Jamaica Alumni of the London School of Economics Jamaican people of English descent Jamaican people of Irish descent Jamaican socialists Royal Canadian Air Force personnel of World War II Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Jamaican members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Columbia University faculty Deaths from cancer in Jamaica Deaths from prostate cancer People's National Party (Jamaica) politicians North American democratic socialists Recipients of the Order of the Nation Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica) Children of national leaders

Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

Royal Canadian Air Force officers

Jamaican expatriates in Antigua and Barbuda

Jamaican expatriates in the United Kingdom

Recipients of the Order of the Caribbean Community