Michael John Kennedy (March 23, 1937 – January 25, 2016) was an American criminal defense attorney, expert in U.S. Constitutional law, and a civil rights advocate who defended cases for the

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU), the

Center for Constitutional Rights

The Center for Constitutional Rights[The Center for Constitutional Rights](_blank)

(CCR) is a National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee The National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (NECLC), until 1968 known as the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, was an organization formed in the United States in October 1951 by 150 educators and clergymen to advocate for the civil liberties ...

(NECLC) and in his private practice. Kennedy, who tried cases in 36 states, was a member of the

National Lawyers Guild

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 193 ...

and the State Bar in

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

and

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

A trial lawyer for over 50 years, Kennedy was known as an exceptional legal strategist who was a "steadfast defender of the underdog and the First Amendment."

Kennedy, who specialized in civil and criminal litigation and complex negotiations, was a guest teacher of trial advocacy at the

University of Texas School of Law

The University of Texas School of Law (Texas Law) is the law school of the University of Texas at Austin. Texas Law is consistently ranked as one of the top law schools in the United States and is highly selective—registering the 8th lowest ac ...

in Austin, and the

Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law

The Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law is the law school of Yeshiva University. Located in New York City and founded in 1976, the school is named for Supreme Court Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo. Cardozo graduated its first class in 1979. An LL.M. p ...

in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

His clients included

Huey P. Newton

Huey Percy Newton (February 17, 1942 – August 22, 1989) was an African-American revolutionary, notable as founder of the Black Panther Party. Newton crafted the Party's ten-point manifesto with Bobby Seale in 1966.

Under Newton's leadershi ...

, co-founder of the

Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxist-Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, Califo ...

;

Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Rae Dohrn (née Ohrnstein; born January 12, 1942) is a retired law professor and a former leader of the left-wing radical group Weather Underground in the United States. As a leader of the Weather Underground in the early 1970s, Dohrn w ...

of the

Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a Far-left politics, far-left militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor, Michigan, Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, the group was organiz ...

;

Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez ; ; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged ...

,

co-founder of the

United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

; leading advocate for the use of LSD

Timothy Leary

Timothy Francis Leary (October 22, 1920 – May 31, 1996) was an American psychologist and author known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs. Evaluations of Leary are polarized, ranging from bold oracle to publicity hound. He was "a her ...

;

members of the

Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA);

Los Siete de la Raza

Los Siete de la Raza (The Seven of the La Raza, Hispanic Community) was the label given to seven young Hispanic and Latino Americans, Latinos from the Mission District of San Francisco, California who were involved in a 1969 altercation with police ...

;

and

Pablo Guzmán of the

Young Lords

The Young Lords, also known as the Young Lords Organization (YLO) or Young Lords Party (YLP), was a Chicago-based street gang that became a civil and human rights organization. The group aims to fight for neighborhood empowerment and self-det ...

. While staff at the

NECLC Kennedy defended members of the

Fort Hood 43

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, thousands of U.S. troops stationed at Fort Hood

Fort Hood is a United States Army post located near Killeen, Texas. Named after Confederate General John Bell Hood, it is locat ...

and the late Stanley Neptune, a member of the

Penobscot Nation

The Penobscot (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewi'') are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic ...

and protester at

Wounded Knee.

Kennedy obtained clemency for

Jean Harris

Jean Struven Harris (April 27, 1923 – December 23, 2012) was the headmistress of The Madeira School for girls in McLean, Virginia, who made national news in the early 1980s when she was tried and convicted of the murder of her ex-lover, Her ...

in 1993. He represented former

Sicilian Mafia

The Sicilian Mafia, also simply known as the Mafia and frequently referred to as Cosa nostra (, ; "our thing") by its members, is an Italian Mafia-terrorist-type organized crime syndicate and criminal society originating in the region of Sicily a ...

don

Gaetano Badalamenti

Gaetano Badalamenti (; 14 September 1923 – 29 April 2004) was a powerful member of the Sicilian Mafia. ''Don Tano'' Badalamenti was the capofamiglia of his hometown Cinisi, Sicily, and headed the Sicilian Mafia Commission in the 1970s. In 198 ...

in the

Pizza Connection drug-smuggling case, and

Ivana Trump

Ivana Marie Trump (, ; February 20, 1949 – July 14, 2022) was a Czech-American businesswoman, media personality, socialite, fashion designer, author, and model. Ivana lived in Canada in the 1970s before relocating to the United States and ...

in her contentious divorce with

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

.

Early life and education

Born in

Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the Canada ...

to Thomas Kennedy and Evelyn (née) Forbes, Kennedy was sent to a

Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

boarding school when he was four years of age where he remained for over a decade. After high school, Kennedy earned a bachelor's degree from the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

in 1962, and

Juris Doctor

The Juris Doctor (J.D. or JD), also known as Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D., JD, D.Jur., or DJur), is a graduate-entry professional degree in law

and one of several Doctor of Law degrees. The J.D. is the standard degree obtained to practice law ...

from the

University of California, Hastings College of the Law

The University of California, Hastings College of the Law (UC Hastings) is a Public university, public Law school in the United States, law school in San Francisco, California. Founded in 1878 by Serranus Clinton Hastings, UC Hastings was the ...

in

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

,

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

.

Career

After law school, Kennedy joined a private law firm and began a career as a defense attorney, often pro bono, in many of the country's well-known civil rights cases.

Time in the U.S. Army

In 1964, Kennedy was first lieutenant in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

, where he was often disciplined for making anti-war speeches while in uniform. At an officers' dinner, Kennedy met Eleanora, the woman who would become his life partner. Once he returned to private life, Kennedy's law practice focused on representing draft resistors, conscientious objectors as well as marginalized people and underrepresented groups seeking social justice.

Legal career

Kennedy's specialty was jury trial work with emphasis on constitutional defenses, including human and civil rights. In the

First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

area, he was regarded as an authority on the laws of libel and tax fraud defense. Kennedy was considered one of the nation's leading authorities on

search and seizure law and the emerging area of privacy rights arising out of the

Fourth and

Ninth amendments. He also tried many cases involving constitutional issues raised by constitutional

due process clauses and

Sixth Amendment fair trial concerns and right to counsel. He litigated many constitutional issues by

Writ of Habeas Corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

.

Kennedy was admitted to practice in the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

and the Court of Appeals for the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and District of Columbia Circuits. He was also admitted to a number of United States District Courts.

Kennedy, and colleague

Michael Tigar

Michael Edward Tigar (born January 18, 1941 in Glendale, California) is an American criminal defense attorney known for representing controversial clients, a human rights activist and a scholar and law teacher. Tigar is an emeritus (retired) mem ...

, put on many provocative programs for the Litigation Section of the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

(ABA), including a death penalty case at

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary

United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz Island, also known simply as Alcatraz (, ''"the gannet"'') or The Rock was a maximum security federal prison on Alcatraz Island, off the coast of San Francisco, California, United States, the site of a for ...

, an Israeli/Palestinian mock arbitration about sovereignty and human rights in

Gaza and the

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, and a much-heralded international tribunal investigating

war crimes in Bosnia.

Notable civil rights cases and clients

Michael Kennedy played a central role in the

nationwide protests against the United States involvement in the Vietnam War. A new breed of radical attorneys were emerging on the legal scene, which included Kennedy and other contemporaries such as

Charles Garry

Charles R. Garry (March 17, 1909 – August 16, 1991) was an Armenian-American civil rights attorney who represented a number of high-profile clients in political cases during the 1960s and 1970s, including Huey P. Newton during his 1968 capital ...

,

Michael Tigar

Michael Edward Tigar (born January 18, 1941 in Glendale, California) is an American criminal defense attorney known for representing controversial clients, a human rights activist and a scholar and law teacher. Tigar is an emeritus (retired) mem ...

,

William Kunstler

William Moses Kunstler (July 7, 1919 – September 4, 1995) was an American lawyer and civil rights activist, known for defending the Chicago Seven. Kunstler was an active member of the National Lawyers Guild, a board member of the American Civil ...

,

Michael Ratner

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian and ...

,

Leonard Boudin

Leonard B. Boudin (July 20, 1912 – November 24, 1989) was an American civil liberties attorney and left-wing activist who represented Daniel Ellsberg of Pentagon Papers fame and Dr. Benjamin Spock, the author of '' Baby and Child Care'', who ...

,

Michael Standard

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

,

Victor Rabinowitz

Victor Rabinowitz (July 2, 1911 – November 16, 2007) was a 20th-century American lawyer known for representing high-profile dissidents and causes.

Background

Rabinowitz was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Rose (née Netter) and Louis M. R ...

, and

Charles Nesson

Charles Rothwell Nesson (born February 11, 1939) is the William F. Weld Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and the founder of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society and of the Global Poker Strategic Thinking Society. He is author of ''E ...

who worked on pro bono cases as often as not. Kennedy moved to New York in the late 1960s to take the position of staff counsel of the

National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee The National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (NECLC), until 1968 known as the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, was an organization formed in the United States in October 1951 by 150 educators and clergymen to advocate for the civil liberties ...

, which until 1968 was known as the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee.

1960s

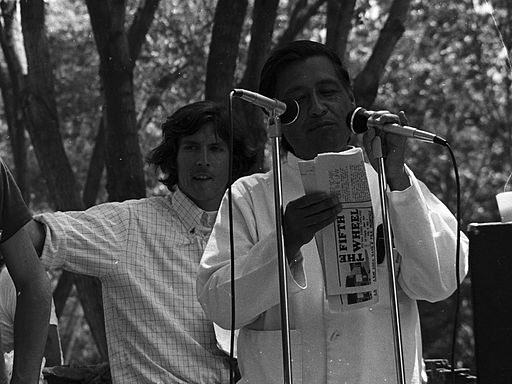

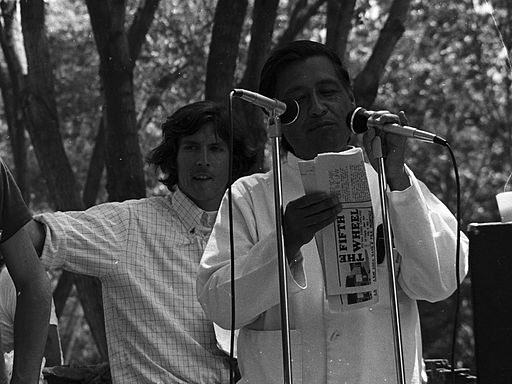

United Farm Workers and Cesar Chavez

Working on behalf of the

NECLC Kennedy represented labor leader

Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez ; ; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged ...

, who along with

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta (born April 10, 1930) is an American labor leader and civil rights activist who, with Cesar Chavez, is a co-founder of the National Farmworkers Association, which later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizi ...

, co-founded the mostly Latino National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which was later renamed as

United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

. Kennedy defended Chavez and migrant farm workers in their protest against exorbitant rents and subpar living conditions. Shortly thereafter, Kennedy got involved in the successful 1965 strike against the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P) for selling non-union grapes and lettuce. The five-year boycott, which became known as the

Delano grape strike

The Delano grape strike was a labor strike organized by the United Farm Workers, Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a predominantly Filipino and AFL-CIO-sponsored labor organization, against table grape growers in Delano, Califo ...

, prompted an international boycott of grapes. The strike, initially organized by the predominantly Filipino

AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million ac ...

-affiliated Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, led to the creation of the

United Farm Workers of America

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

, the first union representing farm workers in the United States.

Fort Hood 43

A group of African American GIs who recently returned from Vietnam were ordered to serve on riot-control duty at the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

in Chicago, Illinois where protests were anticipated in response to the recent

assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at 7 ...

The servicemen refused to serve and were consequently court-martialed. Kennedy successfully represented the group, which became known as the

Fort Hood 43

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, thousands of U.S. troops stationed at Fort Hood

Fort Hood is a United States Army post located near Killeen, Texas. Named after Confederate General John Bell Hood, it is locat ...

. One of Kennedy's clients, the decorated Sgt.

Robert D. Rucker

Robert D. Rucker (born 1947) was the 105th justice appointed to the Indiana Supreme Court. He retired May 12, 2017.

Born in Canton, Georgia, Rucker grew up in Gary, Indiana. He joined the army and served in the 1st Cavalry Division during the ...

, later became an attorney then went on to become the second African American to serve as Judge on the Illinois Supreme Court and the first African American to serve on the Indiana Court of Appeals.

The 1968 Democratic Convention and The Chicago Seven

The

Chicago Seven

The Chicago Seven, originally the Chicago Eight and also known as the Conspiracy Eight or Conspiracy Seven, were seven defendants—Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and Lee Weiner—charged b ...

were charged with conspiracy to incite riots at the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

. While defending

Rennie Davis

Rennard Cordon Davis (May 23, 1940 – February 2, 2021) was an American anti-war activist who gained prominence in the 1960s. He was one of the Chicago Seven defendants charged for anti-war demonstrations and large-scale protests at the 1968 D ...

, Kennedy and three other lawyers -

Gerald B. Lefcourt

Gerald Bernard Lefcourt is an American criminal defense lawyer. He has represented a number of high-profile clients, including financier and registered sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, the Black Panthers, activist/author Abbie Hoffman, hotelier ...

,

Michael Tigar

Michael Edward Tigar (born January 18, 1941 in Glendale, California) is an American criminal defense attorney known for representing controversial clients, a human rights activist and a scholar and law teacher. Tigar is an emeritus (retired) mem ...

and

Dennis Roberts - were briefly jailed for contempt of court by presiding Judge

Julius Hoffman

Julius Jennings Hoffman (July 7, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American attorney and jurist who served as a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. He presided over the Chicago Seven ...

.

Attorney William Kunstler, at the time with the Center for Constitutional Rights, was also cited for contempt though all the convictions were overturned unanimously by the Seventh Circuit. Some thirty attorneys in San Francisco protested Hoffman's punitive decision by burning their Bar Association cards on the steps of the federal building. By the end of the five-month trial, referred to as one of the "most bizarre courtroom spectacles in U.S. history" by the ''Washington Post'', Judge Hoffman had issued over 200 citations for contempt of court against the defendants and their attorneys. All seven defendants -

Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponen ...

,

Jerry Rubin

Jerry Clyde Rubin (July 14, 1938 – November 28, 1994) was an American social activist, anti-war leader, and counterculture icon during the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s, he became a successful businessman. He is known for being one of the ...

,

David Dellinger

David T. Dellinger (August 22, 1915 – May 25, 2004) was an American pacifist and an activist for nonviolent social change. He achieved peak prominence as one of the Chicago Seven, who were put on trial in 1969.

Early life and schooling

Dellin ...

,

Tom Hayden

Thomas Emmet Hayden (December 11, 1939October 23, 2016) was an American social and political activist, author, and politician. Hayden was best known for his role as an anti-war, civil rights, and intellectual activist in the 1960s, authoring th ...

,

Rennie Davis

Rennard Cordon Davis (May 23, 1940 – February 2, 2021) was an American anti-war activist who gained prominence in the 1960s. He was one of the Chicago Seven defendants charged for anti-war demonstrations and large-scale protests at the 1968 D ...

,

John Froines

John Radford Froines (; June 13, 1939 – July 13, 2022) was an American chemist and anti-war activist, noted as a member of the Chicago Seven, a group charged with involvement with the riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chica ...

, and

Lee Weiner

Lee Weiner (born ) is an author and member of the Chicago Seven who was charged with "conspiring to use interstate commerce with intent to incite a riot" and "teaching demonstrators how to construct incendiary devices that would be used in civil d ...

- were acquitted on riot conspiracy charges, though found guilty of intent to riot.

House Un-American Activities Committee

Shortly after the 1968 Democratic Convention, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Dave Dellinger and Robert Greenblatt received subpoenas to appear before the

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

(HUAC). Michael Kennedy was among the group's six defense attorneys. The HUAC hearings were viewed by the

NECLC as an "attempt by the Johnson administration to use every mechanism at its disposal to legitimize the action of Mayor

1968_DNC._Daley_had_ordered_the_entire_Chicago_police_force_of_12,000_men_to_work_12-hour_shifts_and_called_in_over_5,000_National_Guardsmen_in_addition_to_some_1,000_Secret_Service_and_FBI_agents_who_were_also_on_duty.

On_the_opening_day_of_the_HUAC_hearings,_the_subpoenaed_men_and_their_lawyers,_including_Kennedy_and_

William_Kunstler_

William_Moses_Kunstler_(July_7,_1919_–_September_4,_1995)_was_an_American_lawyer_and_civil_rights_activist,_known_for_defending_the_Chicago_Seven._Kunstler_was_an_active_member_of_the_National_Lawyers_Guild,_a_board_member_of_the_American_Civil__...

,_staged_a_"stand-in"_to_protest_the_investigations._"The_Constitution_is_being_raped_and_we_as_lawyers_are_being_emasculated_in_an_armed_camp,"_Kennedy_shouted_at_the_hearing.

Working on behalf of the NECLC Kennedy represented labor leader

Working on behalf of the NECLC Kennedy represented labor leader  A group of African American GIs who recently returned from Vietnam were ordered to serve on riot-control duty at the

A group of African American GIs who recently returned from Vietnam were ordered to serve on riot-control duty at the  When five Irish men in New York were charged with conspiring to smuggle weapons to the

When five Irish men in New York were charged with conspiring to smuggle weapons to the  Though his incarceration and detention were illegal in that he had broken no U.S. laws, Abu Marzook was held in New York's Metropolitan Correctional Center for two years. Noting that Abu Marzook's constitutional

Though his incarceration and detention were illegal in that he had broken no U.S. laws, Abu Marzook was held in New York's Metropolitan Correctional Center for two years. Noting that Abu Marzook's constitutional  Kennedy served as a legal advisor in

Kennedy served as a legal advisor in  Kennedy served as the General Counsel and Chairman of the Board for ''High Times'' Magazine for over 40 years until his death when his wife and board member, Eleanora Kennedy, took the reins. During their four decades at ''High Times'' following the death of its founder Tom Forçade in 1978, the Kennedys and the magazine's staff consistently struggled against marijuana prohibition laws and fought to keep the magazine alive and publishing in an anti-cannabis atmosphere.

The magazine's former associate publisher, Rick Cusick, said the only way ''High Times'' managed to stay in business and never miss a publication date for over four decades was "Really, really good lawyers even though everybody knew I was talking about just one - Michael Kennedy."Chris Simunek, "Requiem For a Dragonslayer, Michael Kennedy, 1937-2016" ''High Times'' Magazine, January 26, 2016

The Kennedys, ''High Times'' magazine and its staff were supporters of the

Kennedy served as the General Counsel and Chairman of the Board for ''High Times'' Magazine for over 40 years until his death when his wife and board member, Eleanora Kennedy, took the reins. During their four decades at ''High Times'' following the death of its founder Tom Forçade in 1978, the Kennedys and the magazine's staff consistently struggled against marijuana prohibition laws and fought to keep the magazine alive and publishing in an anti-cannabis atmosphere.

The magazine's former associate publisher, Rick Cusick, said the only way ''High Times'' managed to stay in business and never miss a publication date for over four decades was "Really, really good lawyers even though everybody knew I was talking about just one - Michael Kennedy."Chris Simunek, "Requiem For a Dragonslayer, Michael Kennedy, 1937-2016" ''High Times'' Magazine, January 26, 2016

The Kennedys, ''High Times'' magazine and its staff were supporters of the  Th

Th Inspired by Kennedy's story, Kirkley used the interview to begin another documentary, ''Radical Love'', about Michael Kennedy's vast legal work in the area of civil rights defense. Woven into the political documentary is the unique love story of Kennedy and his wife and comrade of 47 years, Eleanora. The film also includes significant interviews with two Weathermen,

Inspired by Kennedy's story, Kirkley used the interview to begin another documentary, ''Radical Love'', about Michael Kennedy's vast legal work in the area of civil rights defense. Woven into the political documentary is the unique love story of Kennedy and his wife and comrade of 47 years, Eleanora. The film also includes significant interviews with two Weathermen,  Michael Kennedy was married to Eleanora (née Baratelli) Kennedy for over four decades. Together they have a daughter, Anna Kennedy. Kennedy also has two children from a former marriage: Lisa Marie Kennedy and

Michael Kennedy was married to Eleanora (née Baratelli) Kennedy for over four decades. Together they have a daughter, Anna Kennedy. Kennedy also has two children from a former marriage: Lisa Marie Kennedy and