Metal Galaţi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A metal (from

A metal (from

Metals are shiny and

Metals are shiny and  Metals are typically malleable and ductile, deforming under stress without cleaving. The nondirectional nature of metallic bonding is thought to contribute significantly to the ductility of most metallic solids. In contrast, in an ionic compound like table salt, when the planes of an

Metals are typically malleable and ductile, deforming under stress without cleaving. The nondirectional nature of metallic bonding is thought to contribute significantly to the ductility of most metallic solids. In contrast, in an ionic compound like table salt, when the planes of an

File:Cubic-body-centered.svg, Body-centered cubic crystal structure, with a 2-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. chromium, iron, and tungsten

File:Cubic-face-centered.svg, Face-centered cubic crystal structure, with a 4-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. aluminum, copper, and gold

File:Hexagonal close packed.svg, Hexagonal close-packed crystal structure, with a 6-atom unit cell, as found in e.g. titanium, cobalt, and zinc

The

A metal (from

A metal (from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material

Material is a substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties, or on their geolo ...

that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describ ...

and heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

relatively well. Metals are typically ductile

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

(can be drawn into wires) and malleable

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

(they can be hammered into thin sheets). These properties are the result of the ''metallic bond

Metallic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that arises from the electrostatic attractive force between conduction electrons (in the form of an electron cloud of delocalized electrons) and positively charged metal ions. It may be des ...

'' between the atoms or molecules of the metal.

A metal may be a chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

such as iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

; an alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductilit ...

such as stainless steel; or a molecular compound such as polymeric sulfur nitride.

In physics, a metal is generally regarded as any substance capable of conducting electricity at a temperature of absolute zero. Many elements and compounds that are not normally classified as metals become metallic under high pressures. For example, the nonmetal iodine gradually becomes a metal at a pressure of between 40 and 170 thousand times atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, ...

. Equally, some materials regarded as metals can become nonmetals. Sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

, for example, becomes a nonmetal at pressure of just under two million times atmospheric pressure.

In chemistry, two elements that would otherwise qualify (in physics) as brittle metals—arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

and antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

—are commonly instead recognised as metalloids due to their chemistry (predominantly non-metallic for arsenic, and balanced between metallicity and nonmetallicity for antimony). Around 95 of the 118 elements in the periodic table are metals (or are likely to be such). The number is inexact as the boundaries between metals, nonmetals, and metalloids fluctuate slightly due to a lack of universally accepted definitions of the categories involved.

In astrophysics the term "metal" is cast more widely to refer to all chemical elements in a star that are heavier than helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

, and not just traditional metals. In this sense the first four "metals" collecting in stellar cores through nucleosynthesis are carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

, and neon, all of which are strictly non-metals in chemistry. A star fuses

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses for vehicles

* Fuse (hydraulic), a device used in hydraulic systems to protec ...

lighter atoms, mostly hydrogen and helium, into heavier atoms over its lifetime. Used in that sense, the metallicity of an astronomical object is the proportion of its matter made up of the heavier chemical elements.

Metals, as chemical elements, comprise 25% of the Earth's crust and are present in many aspects of modern life. The strength and resilience of some metals has led to their frequent use in, for example, high-rise building and bridge construction

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form Physical object, objects, systems, or organizations,"Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Pr ...

, as well as most vehicles, many home appliance

A home appliance, also referred to as a domestic appliance, an electric appliance or a household appliance, is a machine which assists in household functions such as cooking, cleaning and food preservation.

Appliances are divided into three ...

s, tools, pipes, and railroad tracks. Precious metals were historically used as coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

age, but in the modern era, coinage metals

The coinage metals comprise, at a minimum, those metallic chemical elements which have historically been used as components in alloys used to mint coins. The term is not perfectly defined, however, since a number of metals have been used to mak ...

have extended to at least 23 of the chemical elements.

The history of refined metals is thought to begin with the use of copper about 11,000 years ago. Gold, silver, iron (as meteoric iron), lead, and brass were likewise in use before the first known appearance of bronze in the fifth millennium BCE. Subsequent developments include the production of early forms of steel; the discovery of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

—the first light metal

A light metal is any metal of relatively low density. More specific definitions have been proposed; none have obtained widespread acceptance. Magnesium, aluminium and titanium are light metals of significant commercial importance. Their densities ...

—in 1809; the rise of modern alloy steel

Alloy steel is steel that is alloyed with a variety of elements in total amounts between 1.0% and 50% by weight to improve its mechanical properties. Alloy steels are broken down into two groups: low alloy steels and high alloy steels. The differe ...

s; and, since the end of World War II, the development of more sophisticated alloys.

Properties

Form and structure

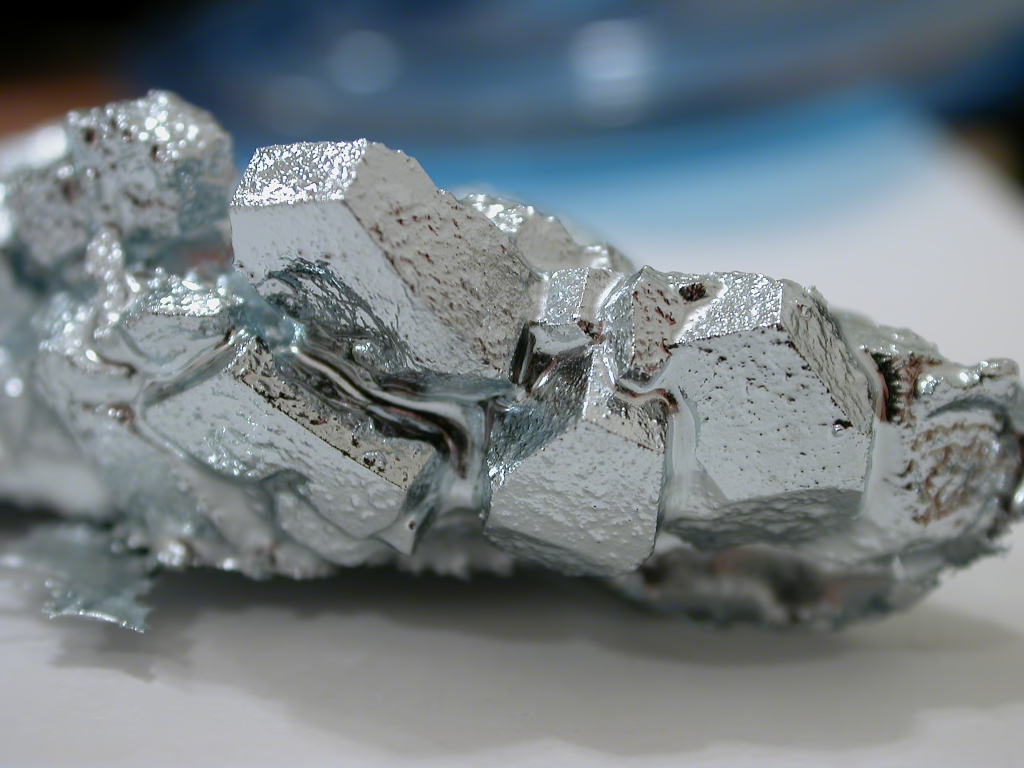

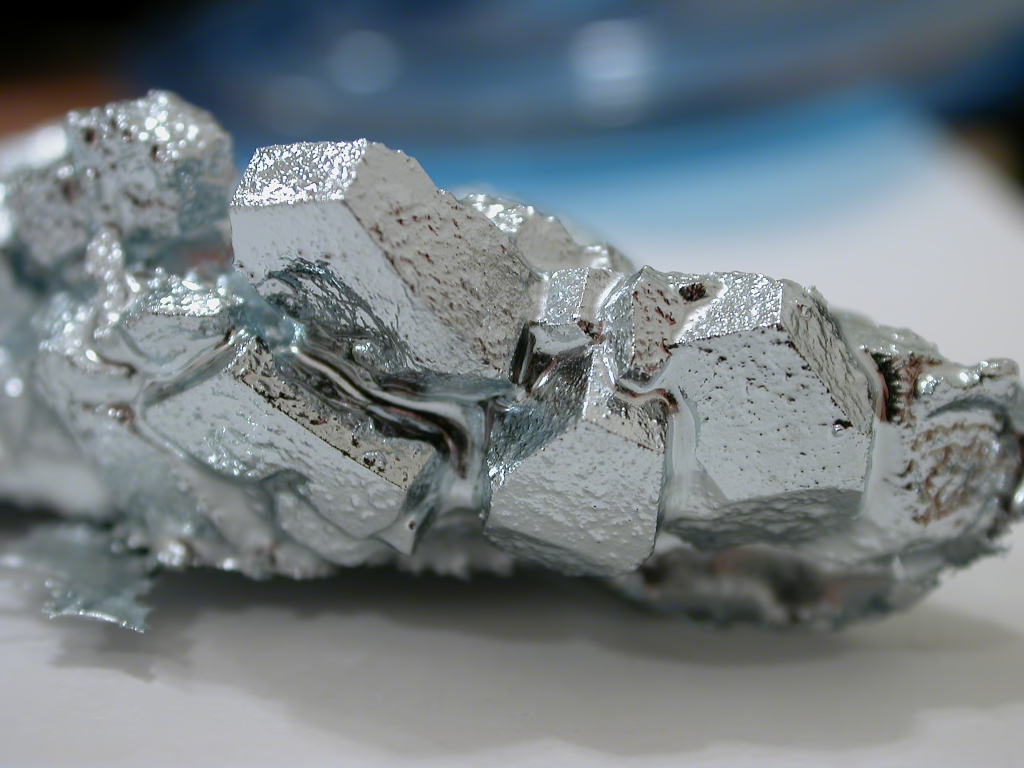

Metals are shiny and

Metals are shiny and lustrous

Lustre (British English) or luster (American English; see spelling differences) is the way light interacts with the surface of a crystal, rock, or mineral. The word traces its origins back to the Latin ''lux'', meaning "light", and generally ...

, at least when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured. Sheets of metal thicker than a few micrometres appear opaque, but gold leaf transmits green light.

The solid or liquid state of metals largely originates in the capacity of the metal atoms involved to readily lose their outer shell electrons. Broadly, the forces holding an individual atom's outer shell electrons in place are weaker than the attractive forces on the same electrons arising from interactions between the atoms in the solid or liquid metal. The electrons involved become delocalised and the atomic structure of a metal can effectively be visualised as a collection of atoms embedded in a cloud of relatively mobile electrons. This type of interaction is called a metallic bond

Metallic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that arises from the electrostatic attractive force between conduction electrons (in the form of an electron cloud of delocalized electrons) and positively charged metal ions. It may be des ...

. The strength of metallic bonds for different elemental metals reaches a maximum around the center of the transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that ca ...

series, as these elements have large numbers of delocalized electrons.

Although most elemental metals have higher densities

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek language, Greek letter Rho (letter), rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' ca ...

than most nonmetals, there is a wide variation in their densities, lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense solid ...

being the least dense (0.534 g/cm3) and osmium (22.59 g/cm3) the most dense. Magnesium, aluminum and titanium are light metal

A light metal is any metal of relatively low density. More specific definitions have been proposed; none have obtained widespread acceptance. Magnesium, aluminium and titanium are light metals of significant commercial importance. Their densities ...

s of significant commercial importance. Their respective densities of 1.7, 2.7, and 4.5 g/cm3 can be compared to those of the older structural metals, like iron at 7.9 and copper at 8.9 g/cm3. An iron ball would thus weigh about as much as three aluminum balls of equal volume.

Metals are typically malleable and ductile, deforming under stress without cleaving. The nondirectional nature of metallic bonding is thought to contribute significantly to the ductility of most metallic solids. In contrast, in an ionic compound like table salt, when the planes of an

Metals are typically malleable and ductile, deforming under stress without cleaving. The nondirectional nature of metallic bonding is thought to contribute significantly to the ductility of most metallic solids. In contrast, in an ionic compound like table salt, when the planes of an ionic bond

Ionic bonding is a type of chemical bonding that involves the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions, or between two atoms with sharply different electronegativities, and is the primary interaction occurring in ionic compounds ...

slide past one another, the resultant change in location shifts ions of the same charge closer, resulting in the cleavage of the crystal. Such a shift is not observed in a covalently bonded

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

crystal, such as a diamond, where fracture and crystal fragmentation occurs. Reversible elastic deformation

In engineering, deformation refers to the change in size or shape of an object. ''Displacements'' are the ''absolute'' change in position of a point on the object. Deflection is the relative change in external displacements on an object. Strain ...

in metals can be described by Hooke's Law

In physics, Hooke's law is an empirical law which states that the force () needed to extend or compress a spring by some distance () scales linearly with respect to that distance—that is, where is a constant factor characteristic of ...

for restoring forces, where the stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

is linearly proportional to the strain

Strain may refer to:

Science and technology

* Strain (biology), variants of plants, viruses or bacteria; or an inbred animal used for experimental purposes

* Strain (chemistry), a chemical stress of a molecule

* Strain (injury), an injury to a mu ...

.

Heat or forces larger than a metal's elastic limit

In materials science and engineering, the yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior. Below the yield point, a material will deform elastically and w ...

may cause a permanent (irreversible) deformation, known as plastic deformation

In engineering, deformation refers to the change in size or shape of an object. ''Displacements'' are the ''absolute'' change in position of a point on the object. Deflection is the relative change in external displacements on an object. Strain ...

or plasticity. An applied force may be a tensile

In physics, tension is described as the pulling force transmitted axially by the means of a string, a rope, chain, or similar object, or by each end of a rod, truss member, or similar three-dimensional object; tension might also be described as ...

(pulling) force, a compressive

In continuum mechanics, stress is a physical quantity. It is a quantity that describes the magnitude of forces that cause deformation. Stress is defined as ''force per unit area''. When an object is pulled apart by a force it will cause elon ...

(pushing) force, or a shear

Shear may refer to:

Textile production

*Animal shearing, the collection of wool from various species

**Sheep shearing

*The removal of nap during wool cloth production

Science and technology Engineering

*Shear strength (soil), the shear strength ...

, bending

In applied mechanics, bending (also known as flexure) characterizes the behavior of a slender structural element subjected to an external load applied perpendicularly to a longitudinal axis of the element.

The structural element is assumed to ...

, or torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bi ...

(twisting) force. A temperature change may affect the movement or displacement of structural defects in the metal such as grain boundaries

In materials science, a grain boundary is the interface between two grains, or crystallites, in a polycrystalline material. Grain boundaries are two-dimensional defects in the crystal structure, and tend to decrease the electrical and thermal ...

, point vacancies, line and screw dislocations, stacking fault

In crystallography, a stacking fault is a planar defect that can occur in crystalline materials.Fine, Morris E. (1921). "Introduction to Chemical and Structural Defects in Crystalline Solids", in ''Treatise on Solid State Chemistry Volume 1'', Spr ...

s and twins

Twins are two offspring produced by the same pregnancy.MedicineNet > Definition of TwinLast Editorial Review: 19 June 2000 Twins can be either ''monozygotic'' ('identical'), meaning that they develop from one zygote, which splits and forms two em ...

in both crystalline

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

and non-crystalline metals. Internal slip

Slip or SLIP may refer to:

Science and technology Biology

* Slip (fish), also known as Black Sole

* Slip (horticulture), a small cutting of a plant as a specimen or for grafting

* Muscle slip, a branching of a muscle, in anatomy

Computing and ...

, creep, and metal fatigue

In materials science, fatigue is the initiation and propagation of cracks in a material due to cyclic loading. Once a fatigue crack has initiated, it grows a small amount with each loading cycle, typically producing striations on some parts o ...

may ensue.

The atoms of metallic substances are typically arranged in one of three common crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns ...

s, namely body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

(bcc), face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

(fcc), and hexagonal close-packed

In geometry, close-packing of equal spheres is a dense arrangement of congruent spheres in an infinite, regular arrangement (or lattice). Carl Friedrich Gauss proved that the highest average density – that is, the greatest fraction of space occu ...

(hcp). In bcc, each atom is positioned at the center of a cube of eight others. In fcc and hcp, each atom is surrounded by twelve others, but the stacking of the layers differs. Some metals adopt different structures depending on the temperature.

unit cell

In geometry, biology, mineralogy and solid state physics, a unit cell is a repeating unit formed by the vectors spanning the points of a lattice. Despite its suggestive name, the unit cell (unlike a unit vector, for example) does not necessaril ...

for each crystal structure is the smallest group of atoms which has the overall symmetry of the crystal, and from which the entire crystalline lattice can be built up by repetition in three dimensions. In the case of the body-centered cubic crystal structure shown above, the unit cell is made up of the central atom plus one-eight of each of the eight corner atoms.

Electrical and thermal

manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

to 6.3 × 105 S/cm for silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

. In contrast, a semiconducting

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical resistivity and conductivity, electrical conductivity value falling between that of a electrical conductor, conductor, such as copper, and an insulator (electricity), insulator, such as glas ...

metalloid such as boron has an electrical conductivity 1.5 × 10−6 S/cm. With one exception, metallic elements reduce their electrical conductivity when heated. Plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

increases its electrical conductivity when heated in the temperature range of around −175 to +125 °C.

Metals are relatively good conductors of heat. The electrons in a metal's electron cloud are highly mobile and easily able to pass on heat-induced vibrational energy.

The contribution of a metal's electrons to its heat capacity and thermal conductivity, and the electrical conductivity of the metal itself can be calculated from the free electron model

In solid-state physics, the free electron model is a quantum mechanical model for the behaviour of charge carriers in a metallic solid. It was developed in 1927, principally by Arnold Sommerfeld, who combined the classical Drude model with quantu ...

. However, this does not take into account the detailed structure of the metal's ion lattice. Taking into account the positive potential caused by the arrangement of the ion cores enables consideration of the electronic band structure

In solid-state physics, the electronic band structure (or simply band structure) of a solid describes the range of energy levels that electrons may have within it, as well as the ranges of energy that they may not have (called ''band gaps'' or ' ...

and binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

of a metal. Various mathematical models are applicable, the simplest being the nearly free electron model

In solid-state physics, the nearly free electron model (or NFE model) or quasi-free electron model is a quantum mechanical model of physical properties of electrons that can move almost freely through the crystal lattice of a solid. The model i ...

.

Chemical

Metals are usually inclined to formcations

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by con ...

through electron loss. Most will react with oxygen in the air to form oxides over various timescales (potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosph ...

burns in seconds while iron rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO( ...

s over years). Some others, like palladium

Palladium is a chemical element with the symbol Pd and atomic number 46. It is a rare and lustrous silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston. He named it after the asteroid Pallas, which was itself na ...

, platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

, and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

, do not react with the atmosphere at all. The oxides of metals are generally basic, as opposed to those of nonmetals, which are acidic or neutral. Exceptions are largely oxides with very high oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. C ...

s such as CrO3, Mn2O7, and OsO4, which have strictly acidic reactions.

Painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ai ...

, anodizing

Anodizing is an electrolytic passivation process used to increase the thickness of the natural oxide layer on the surface of metal parts.

The process is called ''anodizing'' because the part to be treated forms the anode electrode of an electr ...

, or plating

Plating is a surface covering in which a metal is deposited on a conductive surface. Plating has been done for hundreds of years; it is also critical for modern technology. Plating is used to decorate objects, for corrosion inhibition, to impro ...

metals are good ways to prevent their corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engi ...

. However, a more reactive metal in the electrochemical series

The data values of standard electrode potentials (''E''°) are given in the table below, in volts relative to the standard hydrogen electrode, and are for the following conditions:

* A temperature of .

* An effective concentration of 1 mol ...

must be chosen for coating, especially when chipping of the coating is expected. Water and the two metals form an electrochemical cell

An electrochemical cell is a device capable of either generating electrical energy from chemical reactions or using electrical energy to cause chemical reactions. The electrochemical cells which generate an electric current are called voltaic o ...

and, if the coating is less reactive than the underlying metal, the coating actually ''promotes'' corrosion.

Periodic table distribution

In chemistry, the elements which are usually considered to be metals under ordinary conditions are shown in yellow on the periodic table below. The remaining elements are either metalloids (B, Si, Ge, As, Sb, and Te being commonly recognised as such) or nonmetals. Astatine (At) is usually classified as either a nonmetal or a metalloid, but some predictions expect it to be a metal; as such, it has been left blank due to the inconclusive state of the experimental knowledge. The other elements shown as having unknown properties are likely to be metals, but there is some doubt for copernicium (Cn), flerovium (Fl), and oganesson (Og).Alloys

An alloy is a substance having metallic properties and which is composed of two or more elements at least one of which is a metal. An alloy may have a variable or fixed composition. For example, gold and silver form an alloy in which the proportions of gold or silver can be freely adjusted; titanium and silicon form an alloy Ti2Si in which the ratio of the two components is fixed (also known as an

An alloy is a substance having metallic properties and which is composed of two or more elements at least one of which is a metal. An alloy may have a variable or fixed composition. For example, gold and silver form an alloy in which the proportions of gold or silver can be freely adjusted; titanium and silicon form an alloy Ti2Si in which the ratio of the two components is fixed (also known as an intermetallic compound

An intermetallic (also called an intermetallic compound, intermetallic alloy, ordered intermetallic alloy, and a long-range-ordered alloy) is a type of metallic bonding, metallic alloy that forms an ordered solid-state Chemical compound, compoun ...

).

Most pure metals are either too soft, brittle, or chemically reactive for practical use. Combining different ratios of metals as alloys modifies the properties of pure metals to produce desirable characteristics. The aim of making alloys is generally to make them less brittle, harder, resistant to corrosion, or have a more desirable color and luster. Of all the metallic alloys in use today, the alloys of

Most pure metals are either too soft, brittle, or chemically reactive for practical use. Combining different ratios of metals as alloys modifies the properties of pure metals to produce desirable characteristics. The aim of making alloys is generally to make them less brittle, harder, resistant to corrosion, or have a more desirable color and luster. Of all the metallic alloys in use today, the alloys of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

( steel, stainless steel, cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

, tool steel

Tool steel is any of various carbon steels and alloy steels that are particularly well-suited to be made into tools and tooling, including cutting tools, dies, hand tools, knives, and others. Their suitability comes from their distinctive har ...

, alloy steel

Alloy steel is steel that is alloyed with a variety of elements in total amounts between 1.0% and 50% by weight to improve its mechanical properties. Alloy steels are broken down into two groups: low alloy steels and high alloy steels. The differe ...

) make up the largest proportion both by quantity and commercial value. Iron alloyed with various proportions of carbon gives low-, mid-, and high-carbon steels, with increasing carbon levels reducing ductility and toughness. The addition of silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ta ...

will produce cast irons, while the addition of chromium, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, and molybdenum to carbon steels (more than 10%) results in stainless steels.

Other significant metallic alloys are those of aluminum

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It ha ...

, titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resista ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, and magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ta ...

. Copper alloys have been known since prehistory— bronze gave the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

its name—and have many applications today, most importantly in electrical wiring. The alloys of the other three metals have been developed relatively recently; due to their chemical reactivity they require electrolytic

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon di ...

extraction processes. The alloys of aluminum, titanium, and magnesium are valued for their high strength-to-weight ratios; magnesium can also provide electromagnetic shielding

In electrical engineering, electromagnetic shielding is the practice of reducing or blocking the electromagnetic field (EMF) in a space with barriers made of conductive or magnetic materials. It is typically applied to enclosures, for isolatin ...

. These materials are ideal for situations where high strength-to-weight ratio is more important than material cost, such as in aerospace and some automotive applications.

Alloys specially designed for highly demanding applications, such as jet engines, may contain more than ten elements.

Categories

Metals can be categorised according to their physical or chemical properties. Categories described in the subsections below includeferrous

In chemistry, the adjective Ferrous indicates a compound that contains iron(II), meaning iron in its +2 oxidation state, possibly as the divalent cation Fe2+. It is opposed to " ferric" or iron(III), meaning iron in its +3 oxidation state, suc ...

and non-ferrous

In metallurgy, non-ferrous metals are metals or alloys that do not contain iron (allotropes of iron, ferrite, and so on) in appreciable amounts.

Generally more costly than ferrous metals, non-ferrous metals are used because of desirable proper ...

metals; brittle metals and refractory metal

Refractory metals are a class of metals that are extraordinarily resistant to heat and wear. The expression is mostly used in the context of materials science, metallurgy and engineering. The definition of which elements belong to this group diff ...

s; white metals; heavy

Heavy may refer to:

Measures

* Heavy (aeronautics), a term used by pilots and air traffic controllers to refer to aircraft capable of 300,000 lbs or more takeoff weight

* Heavy, a characterization of objects with substantial weight

* Heavy, ...

and light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 te ...

metals; and base, noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Gr ...

, and precious metals. The ''Metallic elements'' table in this section categorises the elemental metals on the basis of their chemical properties into alkali and alkaline earth

The alkaline earth metals are six chemical elements in group 2 of the periodic table. They are beryllium (Be), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), barium (Ba), and radium (Ra).. The elements have very similar properties: they are al ...

metals; transition and post-transition metals; and lanthanides and actinide

The actinide () or actinoid () series encompasses the 15 metallic chemical elements with atomic numbers from 89 to 103, actinium through lawrencium. The actinide series derives its name from the first element in the series, actinium. The info ...

s. Other categories are possible, depending on the criteria for inclusion. For example, the ferromagnetic metals—those metals that are magnetic at room temperature—are iron, cobalt, and nickel.

Ferrous and non-ferrous metals

The term "ferrous" is derived from theLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

word meaning "containing iron". This can include pure iron, such as wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

, or an alloy such as steel. Ferrous metals are often magnetic, but not exclusively. Non-ferrous metals and alloys lack appreciable amounts of iron.

Brittle metal

While nearly all metals are malleable or ductile, a few—beryllium, chromium, manganese, gallium, and bismuth—are brittle. Arsenic and antimony, if admitted as metals, are brittle. Low values of the ratio of bulkelastic modulus

An elastic modulus (also known as modulus of elasticity) is the unit of measurement of an object's or substance's resistance to being deformed elastically (i.e., non-permanently) when a stress is applied to it. The elastic modulus of an object is ...

to shear modulus

In materials science, shear modulus or modulus of rigidity, denoted by ''G'', or sometimes ''S'' or ''μ'', is a measure of the elastic shear stiffness of a material and is defined as the ratio of shear stress to the shear strain:

:G \ \stackre ...

( Pugh's criterion) are indicative of intrinsic brittleness.

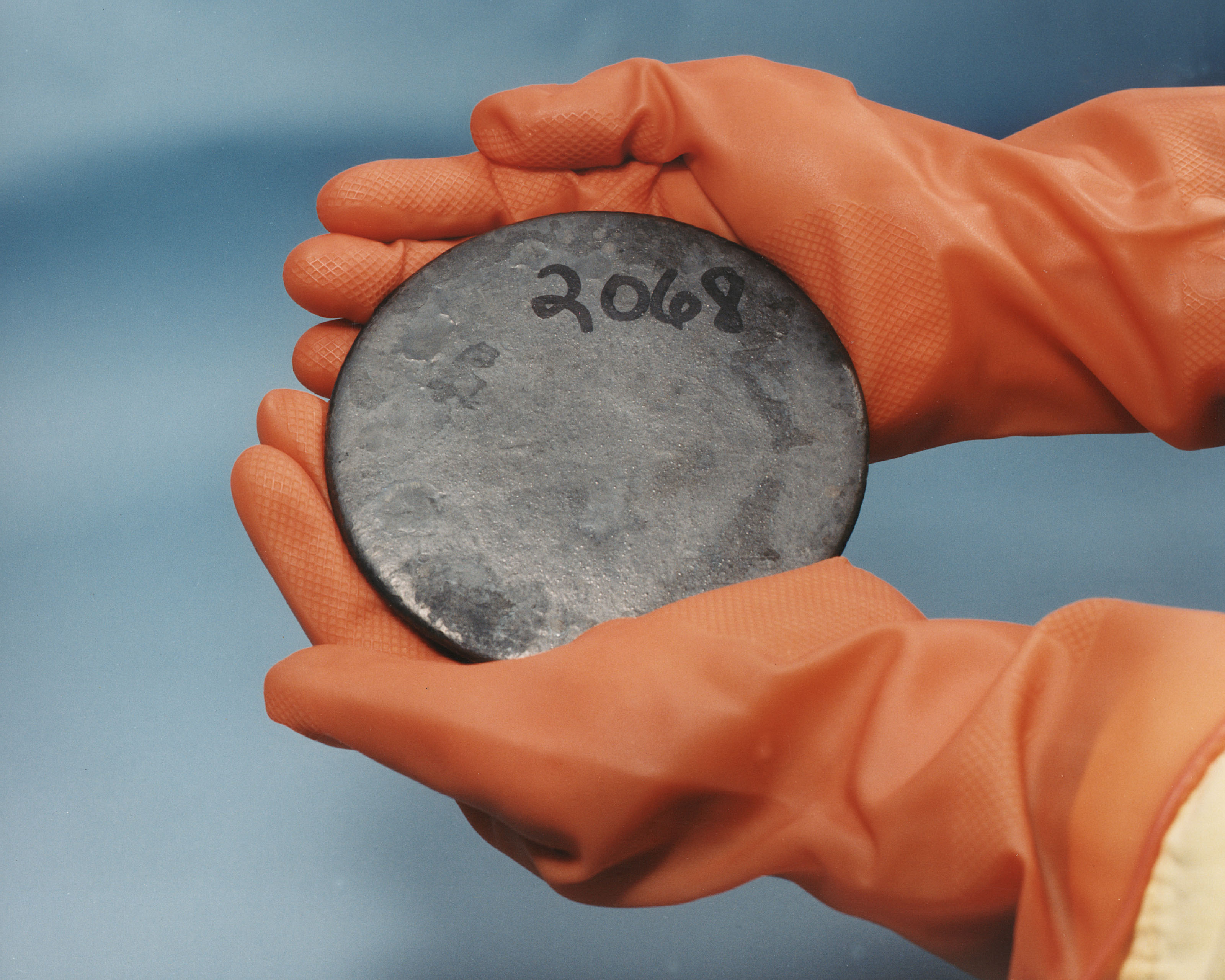

Refractory metal

In materials science, metallurgy, and engineering, a refractory metal is a metal that is extraordinarily resistant to heat and wear. Which metals belong to this category varies; the most common definition includes niobium, molybdenum, tantalum, tungsten, and rhenium. They all have melting points above 2000 °C, and a highhardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

at room temperature.

anodized

Anodizing is an electrolytic passivation process used to increase the thickness of the natural oxide layer on the surface of metal parts.

The process is called ''anodizing'' because the part to be treated forms the anode electrode of an electr ...

niobium cube for comparison

File:Molybdenum crystaline fragment and 1cm3 cube.jpg, Molybdenum crystals and a 1 cm3 molybdenum cube for comparison

File:Tantalum single crystal and 1cm3 cube.jpg, Tantalum single crystal, some crystalline fragments, and a 1 cm3 tantalum cube for comparison

File:Wolfram evaporated crystals and 1cm3 cube.jpg, Tungsten rods with evaporated crystals, partially oxidized with colorful tarnish, and a 1 cm3 tungsten cube for comparison

File:Rhenium single crystal bar and 1cm3 cube.jpg, Rhenium single crystal, a remelted bar, and a 1 cm3 rhenium cube for comparison

White metal

Awhite metal

The white metals are a series of often decorative bright metal alloys used as a base for plated silverware, ornaments or novelties, as well as any of several lead-based or tin-based alloys used for things like bearings, jewellery, miniature f ...

is any of range of white-coloured metals (or their alloys) with relatively low melting points. Such metals include zinc, cadmium, tin, antimony (here counted as a metal), lead, and bismuth, some of which are quite toxic. In Britain, the fine art trade uses the term "white metal" in auction catalogues to describe foreign silver items which do not carry British Assay Office marks, but which are nonetheless understood to be silver and are priced accordingly.

Heavy and light metals

A heavy metal is any relatively dense metal or metalloid. More specific definitions have been proposed, but none have obtained widespread acceptance. Some heavy metals have niche uses, or are notably toxic; some are essential in trace amounts. All other metals are light metals.Base, noble, and precious metals

In chemistry, the term ''base metal'' is used informally to refer to a metal that is easilyoxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

or corroded

Corroded is a heavy metal band from Ånge, Sweden. The band is best known for their song ''Time And Again'', which was the theme song for the Swedish 2009 ''Survivor'' television series on TV4. The band's second album ''Exit to Transfer'', rel ...

, such as reacting easily with dilute hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

(HCl) to form a metal chloride and hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

. Examples include iron, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, and zinc. Copper is considered a base metal as it is oxidized relatively easily, although it does not react with HCl.

The term

The term noble metal

A noble metal is ordinarily regarded as a metallic chemical element that is generally resistant to corrosion and is usually found in nature in its raw form. Gold, platinum, and the other platinum group metals ( ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, o ...

is commonly used in opposition to ''base metal''. Noble metals are resistant to corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engi ...

or oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

, unlike most base metal

A base metal is a common and inexpensive metal, as opposed to a precious metal such as gold or silver. In numismatics, coins often derived their value from the precious metal content; however, base metals have also been used in coins in the past ...

s. They tend to be precious metals, often due to perceived rarity. Examples include gold, platinum, silver, rhodium

Rhodium is a chemical element with the symbol Rh and atomic number 45. It is a very rare, silvery-white, hard, corrosion-resistant transition metal. It is a noble metal and a member of the platinum group. It has only one naturally occurring i ...

, iridium, and palladium.

In alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

and numismatics

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also includ ...

, the term base metal is contrasted with precious metal, that is, those of high economic value.

A longtime goal of the alchemists was the transmutation of base metals into precious metals including such coinage metal

The coinage metals comprise, at a minimum, those metallic chemical elements which have historically been used as components in alloys used to mint coins. The term is not perfectly defined, however, since a number of metals have been used to mak ...

s as silver and gold. Most coins today are made of base metals with low intrinsic value; in the past, coins frequently derived their value primarily from their precious metal content.

Chemically, the precious metals (like the noble metals) are less reactive

Reactive may refer to:

*Generally, capable of having a reaction (disambiguation)

*An adjective abbreviation denoting a bowling ball coverstock made of reactive resin

*Reactivity (chemistry)

*Reactive mind

*Reactive programming

See also

*Reactanc ...

than most elements, have high luster and high electrical conductivity. Historically, precious metals were important as currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general ...

, but are now regarded mainly as investment and industrial commodities. Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

, and palladium

Palladium is a chemical element with the symbol Pd and atomic number 46. It is a rare and lustrous silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston. He named it after the asteroid Pallas, which was itself na ...

each have an ISO 4217 currency code. The best-known precious metals are gold and silver. While both have industrial uses, they are better known for their uses in art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

, jewelry

Jewellery ( UK) or jewelry ( U.S.) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the clothes. From a w ...

, and coinage

Coinage may refer to:

* Coins, standardized as currency

* Neologism, coinage of a new word

* '' COINage'', numismatics magazine

* Tin coinage, a tax on refined tin

* Protologism

''Protologism'' is a term coined in 2003 by the American literary ...

. Other precious metals include the platinum group

The platinum-group metals (abbreviated as the PGMs; alternatively, the platinoids, platinides, platidises, platinum group, platinum metals, platinum family or platinum-group elements (PGEs)) are six noble, precious metallic elements clustered t ...

metals: ruthenium

Ruthenium is a chemical element with the symbol Ru and atomic number 44. It is a rare transition metal belonging to the platinum group of the periodic table. Like the other metals of the platinum group, ruthenium is inert to most other chemical ...

, rhodium

Rhodium is a chemical element with the symbol Rh and atomic number 45. It is a very rare, silvery-white, hard, corrosion-resistant transition metal. It is a noble metal and a member of the platinum group. It has only one naturally occurring i ...

, palladium, osmium, iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density of ...

, and platinum, of which platinum is the most widely traded.

The demand for precious metals is driven not only by their practical use, but also by their role as investments and a store of value

A store of value is any commodity or asset that would normally retain purchasing power into the future and is the function of the asset that can be saved, retrieved and exchanged at a later time, and be predictably useful when retrieved.

The mos ...

. Palladium and platinum, as of fall 2018, were valued at about three quarters the price of gold. Silver is substantially less expensive than these metals, but is often traditionally considered a precious metal in light of its role in coinage and jewelry.

Valve metals

In electrochemistry, a valve metal is a metal which passes current in only one direction.Lifecycle

Formation

:''This sub-section deals with the formation of periodic table elemental metals since these form the basis of metallic materials, as defined in this article.'' Metals up to the vicinity of iron (in the periodic table) are largely made via stellar nucleosynthesis. In this process, lighter elements from hydrogen tosilicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ta ...

undergo successive fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

reactions inside stars, releasing light and heat and forming heavier elements with higher atomic numbers.

Heavier metals are not usually formed this way since fusion reactions involving such nuclei would consume rather than release energy. Rather, they are largely synthesised (from elements with a lower atomic number) by neutron capture

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons, ...

, with the two main modes of this repetitive capture being the s-process and the r-process. In the s-process ("s" stands for "slow"), singular captures are separated by years or decades, allowing the less stable nuclei to beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For ...

, while in the r-process ("rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. Therefore, the s-process takes a more-or-less clear path: for example, stable cadmium-110 nuclei are successively bombarded by free neutrons inside a star until they form cadmium-115 nuclei which are unstable and decay to form indium-115 (which is nearly stable, with a half-life times the age of the universe). These nuclei capture neutrons and form indium-116, which is unstable, and decays to form tin-116, and so on. In contrast, there is no such path in the r-process. The s-process stops at bismuth due to the short half-lives of the next two elements, polonium and astatine, which decay to bismuth or lead. The r-process is so fast it can skip this zone of instability and go on to create heavier elements such as thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

and uranium.

Metals condense in planets as a result of stellar evolution and destruction processes. Stars lose much of their mass when it is ejected

Ejection or Eject may refer to:

* Ejection (sports), the act of officially removing someone from a game

* Eject (''Transformers''), a fictional character from ''The Transformers'' television series

* "Eject" (song), 1993 rap rock single by Sense ...

late in their lifetimes, and sometimes thereafter as a result of a neutron star

A neutron star is the collapsed core of a massive supergiant star, which had a total mass of between 10 and 25 solar masses, possibly more if the star was especially metal-rich. Except for black holes and some hypothetical objects (e.g. w ...

merger, thereby increasing the abundance of elements heavier than helium in the interstellar medium. When gravitational attraction causes this matter to coalesce and collapse new stars and planets are formed.

Abundance and occurrence

The Earth's crust is made of approximately 25% of metals by weight, of which 80% are light metals such as sodium, magnesium, and aluminium. Nonmetals (~75%) make up the rest of the crust. Despite the overall scarcity of some heavier metals such as copper, they can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.

Metals are primarily found as lithophiles (rock-loving) or chalcophiles (ore-loving). Lithophile metals are mainly the s-block elements, the more reactive of the d-block elements, and the f-block elements. They have a strong affinity for oxygen and mostly exist as relatively low-density silicate minerals. Chalcophile metals are mainly the less reactive d-block elements, and the period 4–6 p-block metals. They are usually found in (insoluble) sulfide minerals. Being denser than the lithophiles, hence sinking lower into the crust at the time of its solidification, the chalcophiles tend to be less abundant than the lithophiles.

On the other hand, gold is a siderophile, or iron-loving element. It does not readily form compounds with either oxygen or sulfur. At the time of the Earth's formation, and as the most noble (inert) of metals, gold sank into the core due to its tendency to form high-density metallic alloys. Consequently, it is a relatively rare metal. Some other (less) noble metals—molybdenum, rhenium, the platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), germanium, and tin—can be counted as siderophiles but only in terms of their primary occurrence in the Earth (core, mantle, and crust), rather the crust. These metals otherwise occur in the crust, in small quantities, chiefly as chalcophiles (less so in their native form).

The rotating fluid outer core of the Earth's interior, which is composed mostly of iron, is thought to be the source of Earth's protective magnetic field. The core lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. If it could be rearranged into a column having a footprint it would have a height of nearly 700 light years. The magnetic field shields the Earth from the charged particles of the solar wind, and cosmic rays that would otherwise strip away the upper atmosphere (including the ozone layer that limits the transmission of ultraviolet radiation).

The Earth's crust is made of approximately 25% of metals by weight, of which 80% are light metals such as sodium, magnesium, and aluminium. Nonmetals (~75%) make up the rest of the crust. Despite the overall scarcity of some heavier metals such as copper, they can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.

Metals are primarily found as lithophiles (rock-loving) or chalcophiles (ore-loving). Lithophile metals are mainly the s-block elements, the more reactive of the d-block elements, and the f-block elements. They have a strong affinity for oxygen and mostly exist as relatively low-density silicate minerals. Chalcophile metals are mainly the less reactive d-block elements, and the period 4–6 p-block metals. They are usually found in (insoluble) sulfide minerals. Being denser than the lithophiles, hence sinking lower into the crust at the time of its solidification, the chalcophiles tend to be less abundant than the lithophiles.

On the other hand, gold is a siderophile, or iron-loving element. It does not readily form compounds with either oxygen or sulfur. At the time of the Earth's formation, and as the most noble (inert) of metals, gold sank into the core due to its tendency to form high-density metallic alloys. Consequently, it is a relatively rare metal. Some other (less) noble metals—molybdenum, rhenium, the platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), germanium, and tin—can be counted as siderophiles but only in terms of their primary occurrence in the Earth (core, mantle, and crust), rather the crust. These metals otherwise occur in the crust, in small quantities, chiefly as chalcophiles (less so in their native form).

The rotating fluid outer core of the Earth's interior, which is composed mostly of iron, is thought to be the source of Earth's protective magnetic field. The core lies above Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. If it could be rearranged into a column having a footprint it would have a height of nearly 700 light years. The magnetic field shields the Earth from the charged particles of the solar wind, and cosmic rays that would otherwise strip away the upper atmosphere (including the ozone layer that limits the transmission of ultraviolet radiation).

Extraction

Metals are often extracted from the Earth by means of mining ores that are rich sources of the requisite elements, such asbauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO ...

. Ore is located by prospecting

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting rel ...

techniques, followed by the exploration and examination of deposits. Mineral sources are generally divided into surface mines, which are mined by excavation using heavy equipment, and subsurface mines. In some cases, the sale price of the metal(s) involved make it economically feasible to mine lower concentration sources.

Once the ore is mined, the metals must be extracted, usually by chemical or electrolytic reduction. Pyrometallurgy

Pyrometallurgy is a branch of extractive metallurgy. It consists of the thermal treatment of minerals and metallurgical ores and concentrates to bring about physical and chemical transformations in the materials to enable recovery of valuable ...

uses high temperatures to convert ore into raw metals, while hydrometallurgy

Hydrometallurgy is a technique within the field of extractive metallurgy, the obtaining of metals from their ores. Hydrometallurgy involve the use of aqueous solutions for the recovery of metals from ores, concentrates, and recycled or residual m ...

employs aqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would be re ...

chemistry for the same purpose. The methods used depend on the metal and their contaminants.

When a metal ore is an ionic compound of that metal and a non-metal, the ore must usually be smelted

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a c ...

—heated with a reducing agent—to extract the pure metal. Many common metals, such as iron, are smelted using carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

as a reducing agent. Some metals, such as aluminum and sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

, have no commercially practical reducing agent, and are extracted using electrolysis instead.

Sulfide ores are not reduced directly to the metal but are roasted in air to convert them to oxides.

Uses

Metals are present in nearly all aspects of modern life. Iron, a heavy metal, may be the most common as it accounts for 90% of all refined metals; aluminum, a

Metals are present in nearly all aspects of modern life. Iron, a heavy metal, may be the most common as it accounts for 90% of all refined metals; aluminum, a light metal

A light metal is any metal of relatively low density. More specific definitions have been proposed; none have obtained widespread acceptance. Magnesium, aluminium and titanium are light metals of significant commercial importance. Their densities ...

, is the next most commonly refined metal. Pure iron may be the cheapest metallic element of all at cost of about US$0.07 per gram. Its ores are widespread; it is easy to refine

{{Unreferenced, date=December 2009

Refining (also perhaps called by the mathematical term affining) is the process of purification of a (1) substance or a (2) form. The term is usually used of a natural resource that is almost in a usable form, b ...

; and the technology involved has been developed over hundreds of years. Cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

is even cheaper, at a fraction of US$0.01 per gram, because there is no need for subsequent purification. Platinum, at a cost of about $27 per gram, may be the most ubiquitous given its very high melting point, resistance to corrosion, electrical conductivity, and durability. It is said to be found in, or used to produce, 20% of all consumer goods. Polonium is likely to be the most expensive metal, at a notional cost of about $100,000,000 per gram, due to its scarcity and micro-scale production.

Some metals and metal alloys possess high structural strength per unit mass, making them useful materials for carrying large loads or resisting impact damage. Metal alloys can be engineered to have high resistance to shear, torque, and deformation. However the same metal can also be vulnerable to fatigue damage through repeated use or from sudden stress failure when a load capacity is exceeded. The strength and resilience of metals has led to their frequent use in high-rise building and bridge construction, as well as most vehicles, many appliances, tools, pipes, and railroad tracks.

Metals are good conductors, making them valuable in electrical appliances and for carrying an electric current over a distance with little energy lost. Electrical power grids rely on metal cables to distribute electricity. Home electrical systems, for the most part, are wired with copper wire for its good conducting properties.

The thermal conductivity of metals is useful for containers to heat materials over a flame. Metals are also used for heat sink

A heat sink (also commonly spelled heatsink) is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant, where it is dissipated away from the device, th ...

s to protect sensitive equipment from overheating.

The high reflectivity of some metals enables their use in mirrors, including precision astronomical instruments, and adds to the aesthetics of metallic jewelry.

Some metals have specialized uses; mercury is a liquid at room temperature and is used in switches to complete a circuit when it flows over the switch contacts. Radioactive metals such as uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

and plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

are fuel for nuclear power plants, which produce energy via nuclear fission. Shape-memory alloy

In metallurgy, a shape-memory alloy (SMA) is an alloy that can be deformed when cold but returns to its pre-deformed ("remembered") shape when heated. It may also be called memory metal, memory alloy, smart metal, smart alloy, or muscle wire.

P ...

s are used for applications such as pipes, fasteners, and vascular stent

In medicine, a stent is a metal or plastic tube inserted into the lumen of an anatomic vessel or duct to keep the passageway open, and stenting is the placement of a stent. A wide variety of stents are used for different purposes, from expandab ...

s.

Metals can be doped with foreign molecules—organic, inorganic, biological, and polymers. This doping entails the metal with new properties that are induced by the guest molecules. Applications in catalysis, medicine, electrochemical cells, corrosion and more have been developed.

Recycling

Demand for metals is closely linked to economic growth given their use in infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, and consumer goods. During the 20th century, the variety of metals used in society grew rapidly. Today, the development of major nations, such as China and India, and technological advances, are fuelling ever more demand. The result is that mining activities are expanding, and more and more of the world's metal stocks are above ground in use, rather than below ground as unused reserves. An example is the in-use stock of

Demand for metals is closely linked to economic growth given their use in infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, and consumer goods. During the 20th century, the variety of metals used in society grew rapidly. Today, the development of major nations, such as China and India, and technological advances, are fuelling ever more demand. The result is that mining activities are expanding, and more and more of the world's metal stocks are above ground in use, rather than below ground as unused reserves. An example is the in-use stock of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

. Between 1932 and 1999, copper in use in the U.S. rose from 73 g to 238 g per person.''The Recycling Rates of Metals: A Status Report''2010,

International Resource Panel

The International Resource Panel is a scientific panel of experts that aims to help nations use natural resources sustainably without compromising economic growth and human needs. It provides independent scientific assessments and expert advice on ...

, United Nations Environment Programme

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental issues within the United Nations system. It was established by Maurice Strong, its first director, after the United Nations Conference on th ...

Metals are inherently recyclable, so in principle, can be used over and over again, minimizing these negative environmental impacts and saving energy. For example, 95% of the energy used to make aluminum from bauxite ore is saved by using recycled material.

Globally, metal recycling is generally low. In 2010, the International Resource Panel

The International Resource Panel is a scientific panel of experts that aims to help nations use natural resources sustainably without compromising economic growth and human needs. It provides independent scientific assessments and expert advice on ...

, hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental issues within the United Nations system. It was established by Maurice Strong, its first director, after the United Nations Conference on th ...

published reports on metal stocks that exist within society and their recycling rates. The authors of the report observed that the metal stocks in society can serve as huge mines above ground. They warned that the recycling rates of some rare metals used in applications such as mobile phones, battery packs for hybrid cars and fuel cells are so low that unless future end-of-life recycling rates are dramatically stepped up these critical metals will become unavailable for use in modern technology.

Biological interactions

The role of metallic elements in the evolution of cell biochemistry has been reviewed, including a detailed section on the role ofcalcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

in redox enzymes.

One or more of the elements iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

, cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, p ...

, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, and zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

are essential to all higher forms of life. Molybdenum is an essential component of vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism. It is one of eight B vitamins. It is required by animals, which use it as a cofactor in DNA synthesis, in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. ...

. Compounds of all other transition elements and post-transition elements are toxic to a greater or lesser extent, with few exceptions such as certain compounds of antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

and tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

. Potential sources of metal poisoning include mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic ...

, tailings

In mining, tailings are the materials left over after the process of separating the valuable fraction from the uneconomic fraction (gangue) of an ore. Tailings are different to overburden, which is the waste rock or other material that overli ...

, industrial wastes, agricultural runoff

Agricultural pollution refers to biotic and abiotic byproducts of farming practices that result in contamination or degradation of the environment and surrounding ecosystems, and/or cause injury to humans and their economic interests. The pol ...

, occupational exposure, paints

Paint is any pigmented liquid, liquefiable, or solid mastic composition that, after application to a substrate in a thin layer, converts to a solid film. It is most commonly used to protect, color, or provide texture. Paint can be made in many ...

, and treated timber.

History

Prehistory

Copper, which occurs in native form, may have been the first metal discovered given its distinctive appearance, heaviness, and malleability compared to other stones or pebbles. Gold, silver, and iron (as meteoric iron), and lead were likewise discovered in prehistory. Forms ofbrass