McMahon killings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The McMahon killings or the McMahon murders occurred on 24 March 1922 when six Catholic civilians were shot dead at the home of the McMahon family in

It has been alleged that a group of policemen operating out of Brown Square Barracks in the Shankill Road area were behind the killings. This has never been proved, but historian Éamon Phoenix, of

It has been alleged that a group of policemen operating out of Brown Square Barracks in the Shankill Road area were behind the killings. This has never been proved, but historian Éamon Phoenix, of

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, BĂ©al Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. A group of police officers broke into their house at night and shot all eight males inside, in an apparent sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

attack. The victims were businessman Owen McMahon, four of his sons, and one of his employees. Two others were shot but survived, and a female family member was assaulted. The survivors said most of the gunmen wore police uniform and it is suspected they were members of the Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

(USC). It is believed to have been a reprisal for the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

's (IRA) killing of two policemen on May Street, Belfast the day before.

Northern Ireland had been created ten months before, in the midst of the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. A truce ended the war in most of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

; but sectarian conflict in Belfast, and fighting in border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders c ...

areas, continued. Northern Ireland's police – especially the USC, which was almost wholly Protestant and unionist – were implicated in a number of attacks on Catholic and Irish nationalist civilians as reprisal for IRA actions. A week later, six more Catholics were killed in another reprisal attack.

Background

In May 1921, during theIrish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

, Ireland was partitioned under British law, creating Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. In July 1921, a truce was agreed between representatives of the Irish Republic and the British Government, ending the war in most of Ireland. Under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, most of Ireland would become the Irish Free State, while Northern Ireland could choose to remain part of the United Kingdom, with the final border being decided by a boundary commission. Violence continued in Northern Ireland after the truce. In the first half of 1922, in the words of historian Robert Lynch, the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA), "would make one final attempt to undermine the ever hardening reality of partition by launching an all out offensive on the recently established province of Northern Ireland".

To counter the IRA, the new unionist Government of Northern Ireland established the Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

(USC), a quasi-military reserve police force to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). The USC had a mutually hostile relationship with Irish nationalists and republicans in Northern Ireland. Lynch writes of the USC: "some were polite and courteous, others merely arrogant and destructive whilst a small anonymous minority set out to kill".

The McMahon killings are believed to have been a reprisal for the IRA's killing of two USC men in Belfast. On 23 March 1922, constables Thomas Cunningham and William Cairnside were patrolling Great Victoria Street

Great Victoria Street in Belfast, Northern Ireland, is a major thoroughfare located in the city centre and is one of the important streets used by pedestrians alighting from Belfast Great Victoria Street railway station and walking into shopping s ...

in the city centre when they were approached by a group of IRA members and shot dead. Two Catholics, Peter Murphy (61) and Sarah McShane (15), were shot dead in a suspected reprisal attack several hours later in the Catholic Short Strand area by unidentified gunmen.

The McMahon family had no links to any paramilitary violence. Owen McMahon was a supporter and personal friend of Joe Devlin Joseph or Joe Devlin may refer to:

* Joseph Devlin (1871–1934), Irish journalist and nationalist politician

* Joe Devlin (American football) (born 1954), American football offensive tackle

* Joe Devlin (footballer) (born 1927), retired Scottish ...

, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) Member of Parliament (MP), an Irish nationalist who rejected republican violence. McMahon was a prosperous businessman, who owned several pubs in Belfast (one of which was The Capstan Bar on Ann Street) and had at one time been chairman of the Northern Vintners' Association. His home at Kinnaird Terrace, off the Antrim Road in north-central Belfast, near the New Lodge New Lodge may refer to:

*New Lodge, Winkfield near Windsor, Berkshire, England

*New Lodge, South Yorkshire, England

*New Lodge, Belfast, an area of North Belfast, Northern Ireland

*New Lodge, Billericay, association football ground in Billericay, E ...

area, was described as a "sprawling Victorian mansion". However, one of the men killed at Kinnaird Terrace, Edward McKinney, an employee of the McMahon family, was subsequently and posthumously acknowledged to have been an IRA volunteer by IRA GHQ (General Headquarters). In his book, ''Donegal and The Civil War'', Liam Ă“ Duibhir wrote that ''"His cKinney's IRA... membership was concealed after the killings as it would have given the police and the loyalist mob an opportunity to justify their actions."''

Killings

At about 1:00 am on 24 March 1922, two men wearing police uniforms seized asledgehammer

A sledgehammer is a tool with a large, flat, often metal head, attached to a long handle. The long handle combined with a heavy head allows the sledgehammer to gather momentum during a swing and apply a large force compared to hammers designed t ...

from a Belfast Corporation

Belfast City Council ( ga, Comhairle Cathrach Bhéal Feirste) is the local authority with responsibility for part of the city of Belfast, the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland. The Council serves an estimated population of (), the l ...

workman, who was guarding a building site at Carlisle Circus. The sledgehammer was later used to smash open the McMahon door. A curfew was in place at the time, due to the daily violence in the city. At nearby Clifton Avenue they met three other men and the party of five proceeded to the home of Owen McMahon. Eight males and three women were in the house that night. The males were Owen, his six sons, and Edward McKinney. McKinney was from Desertegney, a parish just north of Buncrana in Inishowen, County Donegal. He worked for the McMahons as a barman

A bartender (also known as a barkeep, barman, barmaid, or a mixologist) is a person who formulates and serves alcoholic or soft drink beverages behind the bar, usually in a licensed establishment as well as in restaurants and nightclubs, but ...

. The women were Owen's wife Eliza, her daughter and her niece. At about 1:20 am, the gang used the sledgehammer to break down the door of the McMahon household.

Owen's wife, Eliza, said that four of the men wore police caps and carried revolvers while another wore civilian clothes. John McMahon, one of Owen's sons, said "Four of the five men were dressed in the uniform of the RIC but, from their appearance, I know they are Specials, not regular RIC". All of the men had hidden their faces. The four men in police uniform rushed up the stairs and herded the males into the dining room. The women were taken into another room. Eliza "got down on her knees and pleaded for mercy, but was struck on the side of the head and fell to the floor". When Owen asked why his family was being singled-out, one of the gunmen said it was because he was "a respected papist

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

". The gunmen said "you boys say your prayers", before opening fire. Five of the men were killed outright and two were wounded, one fatally.

Owen McMahon (50), Gerard McMahon (15), Frank McMahon (24), Patrick McMahon (22) and Edward McKinney (25) were killed outright while Bernard McMahon (26) died later. The youngest McMahon son, 12-year-old Michael, survived the attack by hiding behind furniture and pretending to be hit. John McMahon (30) survived despite serious gunshot wounds. Eliza McMahon raised the alarm by opening the drawing room window and shouting "Murder! Murder!" A matron at an adjoining nursing home was alerted and phoned the police and an ambulance.

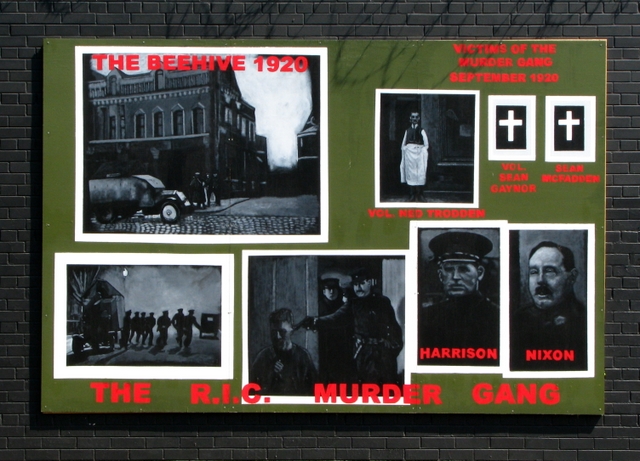

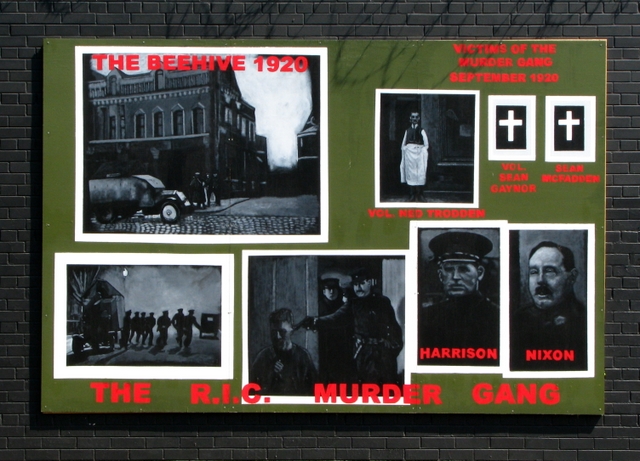

It has been alleged that a group of policemen operating out of Brown Square Barracks in the Shankill Road area were behind the killings. This has never been proved, but historian Éamon Phoenix, of

It has been alleged that a group of policemen operating out of Brown Square Barracks in the Shankill Road area were behind the killings. This has never been proved, but historian Éamon Phoenix, of Stranmillis College

Stranmillis University College is a university college of Queen's University Belfast. The institution is located on the Stranmillis Road in Belfast. It had students in . The school offers the BEd, PGCE and TESOL, as well as other courses.

Hi ...

in Belfast, has said there is "strong circumstantial evidence" that District Inspector

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

John Nixon John Nixon is the name of:

Politicians

*John Nixon (MP), Member of the Long Parliament in England, representing Oxford City 1646-1648

*John T. Nixon (1820–1889), U.S. Representative from New Jersey

* John William Nixon (1880–1949), Unionist pol ...

was responsible. Historian Tim Pat Coogan also believes the police were responsible. An inquiry was carried out by the Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

of the Irish Free State, but not by the Northern Ireland authorities. A 1924 Free State report alleged that twelve policemen, whom the report identified by name, had carried out the McMahon murders, as well as several other attacks on Catholics.

Aftermath

The killings caused outrage among Belfast's Catholic population and over 10,000 people attended the funerals of those killed. The funerals of Owen, Gerard, Frank and Patrick were held on Sunday, 26 March. The British Army lined the route of the funeral procession – from north Belfast to Milltown Cemetery – anticipating it would be attacked. Edward McKinney was buried on the same day, Sunday, 26 March, in Cockhill Cemetery just outside Buncrana in his native Inishowen. At the funeral Mass for the victims at St Patrick's Church, Rev Father Bernard Laverty told the congregation that even the Black and Tans "had not been guilty of anything approaching this rimein its unspeakable barbarity". The McMahons had been "done to death merely because they were Catholics", but he told the mourners to practise "patience and forbearance" and not to seek revenge. Irish Nationalist Party MPJoe Devlin Joseph or Joe Devlin may refer to:

* Joseph Devlin (1871–1934), Irish journalist and nationalist politician

* Joe Devlin (American football) (born 1954), American football offensive tackle

* Joe Devlin (footballer) (born 1927), retired Scottish ...

told the British Parliament, "If Catholics have no revolvers to protect themselves they are murdered. If they have revolvers they are flogged and sentenced to death".

David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, worried that the violence would collapse the new Northern Ireland administration, organised a meeting in London between Irish republican leader Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

and Sir James Craig

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon PC PC (NI) DL (8 January 1871 – 24 November 1940), was a leading Irish unionist and a key architect of Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom. During the Home Rule Crisis of 1912 ...

, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, both to try to stop the IRA violence which Collins had been tacitly encouraging and supporting, and to pressure Craig to provide more protection for Catholics. Craig denied the nationalist assertion that the McMahon killings were part of an anti-Catholic pogrom on behalf of state forces, telling the Parliament of Northern Ireland that, "no such thing has ever been the policy of Protestants here ... The Ulster men are up against, not Catholics but ... up against rebels, that they are up against murder, Bolshevism and up against those enemies not only of Ulster but of the ritishEmpire".

The killings were part of a series of reprisals on Catholics for IRA attacks in Belfast and elsewhere. The following week saw a similar incident in Belfast known as the "Arnon Street killings

The Arnon Street killings, also referred to as the Arnon Street murders or the Arnon Street massacre, took place on 1 April 1922 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Six Catholic civilians, three in Arnon Street, were shot or beaten to death by men wh ...

", in which five Catholics were killed by uniformed police who broke into their homes; allegedly in revenge for the killing of a policeman. In total, 452 people would be killed in Belfast in the conflict between June 1920 and July 1922 – 267 Catholics and 185 Protestants.

No one was ever prosecuted for the killings but District Inspector John Nixon John Nixon is the name of:

Politicians

*John Nixon (MP), Member of the Long Parliament in England, representing Oxford City 1646-1648

*John T. Nixon (1820–1889), U.S. Representative from New Jersey

* John William Nixon (1880–1949), Unionist pol ...

of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was accused of involvement by historians Tim Pat Coogan and Éamon Phoenix.

Nixon was later forced to step down from the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(the force that succeeded the RIC in June 1922), albeit on full pension, in 1924 after being heard giving (in breach of police regulations) a political speech to an Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

meeting saying that, "not an inch of Ulster should be yielded" to the Free State.

See also

*Timeline of the Irish War of Independence

This is a timeline of the Irish War of Independence (or the Anglo-Irish War) of 1919–21. The Irish War of Independence was a guerrilla conflict and most of the fighting was conducted on a small scale by the standards of conventional warfare.

...

References

Citations

Sources

* * {{authority control Mass murder in 1922 1922 murders in the United Kingdom 1922 in Northern Ireland 20th century in Belfast Murder in Northern Ireland Massacres committed by the United Kingdom Massacres of men Violence against men in Europe Royal Irish Constabulary Police misconduct in Northern Ireland Deaths by firearm in Northern Ireland March 1922 events 1920s murders in Northern Ireland 1922 murders in Europe History of Belfast