Mazurek Dąbrowskiego on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

( " Dąbrowski's

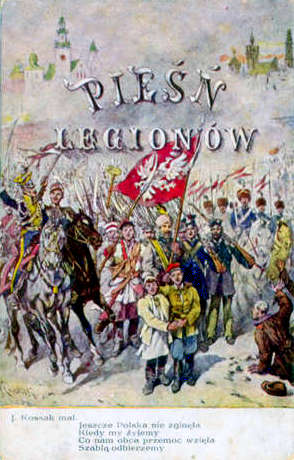

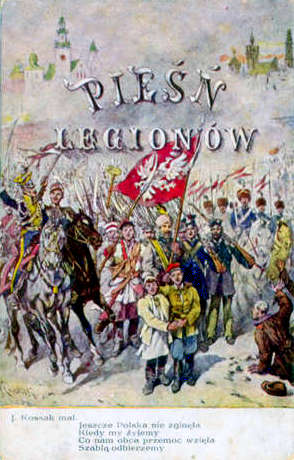

It is also known by its original title, "" (, "Song of the Polish Legions in Italy"). English translations of its Polish

It is also known by its original title, "" (, "Song of the Polish Legions in Italy"). English translations of its Polish

The original lyrics, authored by Wybicki, are a poem consisting of six

The original lyrics, authored by Wybicki, are a poem consisting of six  The chorus and subsequent stanzas include heart-lifting examples of military heroes, set as role models for Polish soldiers:

The chorus and subsequent stanzas include heart-lifting examples of military heroes, set as role models for Polish soldiers:  Stefan Czarniecki was a 17th-century

Stefan Czarniecki was a 17th-century

Constitution of the Republic of Poland

As such, it is protected by law which declares that treating the national symbols "with reverence and respect" is the "right and obligation" of every Polish citizen and all state organs, institutions and organizations. The anthem should be performed or reproduced especially at celebrations of national holidays and anniversaries. Civilians should pay respect to the anthem by standing in a dignified manner; additionally, men should uncover their heads. Members of uniformed services should stand at attention; if their uniform includes headgear and they are not standing in an organized group, they should also perform the

In 1795, after a prolonged decline and despite last-minute attempts at constitutional reforms and armed resistance, the

In 1795, after a prolonged decline and despite last-minute attempts at constitutional reforms and armed resistance, the  Meanwhile, Polish patriots and revolutionaries turned for help to

Meanwhile, Polish patriots and revolutionaries turned for help to  In early July 1797, Wybicki arrived in Reggio Emilia where the Polish Legions were then quartered and where he wrote the ''Song of the Polish Legions'' soon afterwards. He first sung it at a private meeting of Polish officers in the Legions' headquarters at the episcopal palace in Reggio. The first public performance most probably took place on 16 July 1797 during a military parade in Reggio's Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral Square). On 20 July, it was played again as the Legions were marching off from Reggio to

In early July 1797, Wybicki arrived in Reggio Emilia where the Polish Legions were then quartered and where he wrote the ''Song of the Polish Legions'' soon afterwards. He first sung it at a private meeting of Polish officers in the Legions' headquarters at the episcopal palace in Reggio. The first public performance most probably took place on 16 July 1797 during a military parade in Reggio's Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral Square). On 20 July, it was played again as the Legions were marching off from Reggio to

The ultimate fate of the Polish Legions in Italy was different from that promised by Wybicki's song. Rather than coming back to Poland, they were exploited by the French government to quell uprisings in Italy, Germany and, later, in

The ultimate fate of the Polish Legions in Italy was different from that promised by Wybicki's song. Rather than coming back to Poland, they were exploited by the French government to quell uprisings in Italy, Germany and, later, in  With Napoleon's defeat and the

With Napoleon's defeat and the

In the Middle Ages, the role of a national anthem was played by hymns. Among them were ''

In the Middle Ages, the role of a national anthem was played by hymns. Among them were ''

Poland: "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" (Poland Is Not Yet Lost)

Audio, information, lyrics

archive link

Museum of the National Anthem at Będomin

– A museum dedicated to the National Anthem (Polish)

– The promotional website "Polska" features a page on the anthem with an instrumental version.

Hymn Polski

– The website for the Center for Citizenship Education features a page on the anthem than includes vocal and instrumental versions.

– A copy of the oldest known recording of the anthem, 1926 by Ignacy Dygas, is available here.

Russian-Records.com

– Edison phonograph cylinder record performed by Stanisław Bolewski. It is probably the oldest recording of the anthem. {{Authority control 1797 compositions National anthems National symbols of Poland Polish patriotic songs Italy–Poland relations Polish Legions (Napoleonic period) European anthems Polish nationalism (1795–1918) 1797 in Poland National anthem compositions in F major Mazurka

Mazurka

The mazurka (Polish: ''mazur'' Polish ball dance, one of the five Polish national dances and ''mazurek'' Polish folk dance') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dances in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo, with character de ...

"), in English officially known by its incipit

The incipit () of a text is the first few words of the text, employed as an identifying label. In a musical composition, an incipit is an initial sequence of notes, having the same purpose. The word ''incipit'' comes from Latin and means "it b ...

Poland Is Not Yet Lost, is the national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and Europe ...

of the Republic of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

.

The original lyrics

Lyrics are words that make up a song, usually consisting of verses and choruses. The writer of lyrics is a lyricist. The words to an extended musical composition such as an opera are, however, usually known as a "libretto" and their writer ...

were written by Józef Wybicki

Józef Rufin Wybicki (; 29 September 1747 – 10 March 1822) was a Polish nobleman, jurist, poet, political and military activist of Kashubian descent. He is best remembered as the author of "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" (), which was adopted as the P ...

in Reggio Emilia

Reggio nell'Emilia ( egl, Rèz; la, Regium Lepidi), usually referred to as Reggio Emilia, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, and known until 1861 as Reggio di Lombardia, is a city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has abou ...

, in Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative Regions ...

, between 16 and 19 July 1797, two years after the Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Poli ...

erased the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

from the map. Its initial purpose was to raise the morale of Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (; also known as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski (Dombrowski) in German and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French; 2 August 1755 – 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patrio ...

's Polish Legions that served with Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

in the Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars

The Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) were a series of conflicts fought principally in Northern Italy between the French Revolutionary Army and a Coalition of Austria, Russia, Piedmont-Sardinia, and a number ...

. "Dąbrowski's Mazurka" expressed the idea that the nation of Poland, despite lacking an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

state of their own, had not disappeared as long as the Polish people endured and fought in its name.

The music is an unattributed mazurka

The mazurka (Polish: ''mazur'' Polish ball dance, one of the five Polish national dances and ''mazurek'' Polish folk dance') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dances in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo, with character de ...

and considered a "folk tune

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has be ...

" that Polish composer Edward Pałłasz categorizes as "functional art" which was "fashionable among the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

and rich bourgeoisie". Pałłasz wrote, "Wybicki probably made use of melodic motifs he had heard and combined them in one formal structure to suit the text".

When Poland re-emerged as an independent state in 1918, "Dąbrowski's Mazurka" became its ''de facto'' national anthem. It was officially adopted as the national anthem of Poland in 1926. It also inspired similar songs by other peoples struggling for independence during the 19th century, such as the Ukrainian national anthem

"" ( uk, Ще не вмерла України і слава, і воля, , lit=The glory and freedom of Ukraine has not yet perished), also known by its official title of "State Anthem of Ukraine" (, ') or by its shortened form "" (, ), is the ...

and the song " Hej, Sloveni" which was used as the national anthem of socialist Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yugo ...

during that state's existence.

Etymology

It is also known by its original title, "" (, "Song of the Polish Legions in Italy"). English translations of its Polish

It is also known by its original title, "" (, "Song of the Polish Legions in Italy"). English translations of its Polish incipit

The incipit () of a text is the first few words of the text, employed as an identifying label. In a musical composition, an incipit is an initial sequence of notes, having the same purpose. The word ''incipit'' comes from Latin and means "it b ...

("" ) include: "Poland has not yet perished", "Poland has not perished yet", "Poland is not lost", "Poland is not lost yet", and "Poland is not yet lost".

Lyrics

The original lyrics, authored by Wybicki, are a poem consisting of six

The original lyrics, authored by Wybicki, are a poem consisting of six quatrain

A quatrain is a type of stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four lines.

Existing in a variety of forms, the quatrain appears in poems from the poetic traditions of various ancient civilizations including Persia, Ancient India, Ancient Gre ...

s and a refrain

A refrain (from Vulgar Latin ''refringere'', "to repeat", and later from Old French ''refraindre'') is the line or lines that are repeated in music or in poetry — the "chorus" of a song. Poetic fixed forms that feature refrains include the v ...

quatrain repeated after all but the last stanza, all following an ABAB rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB rh ...

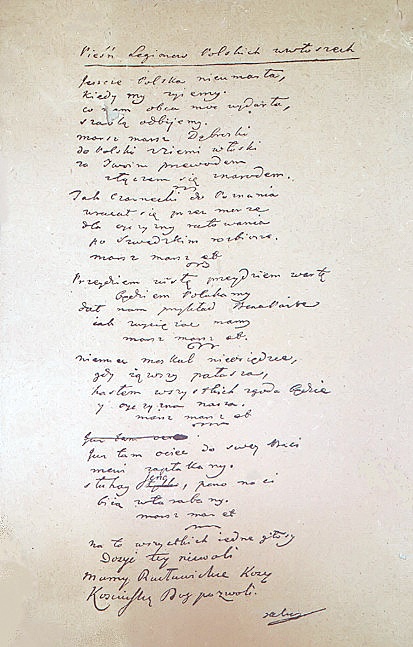

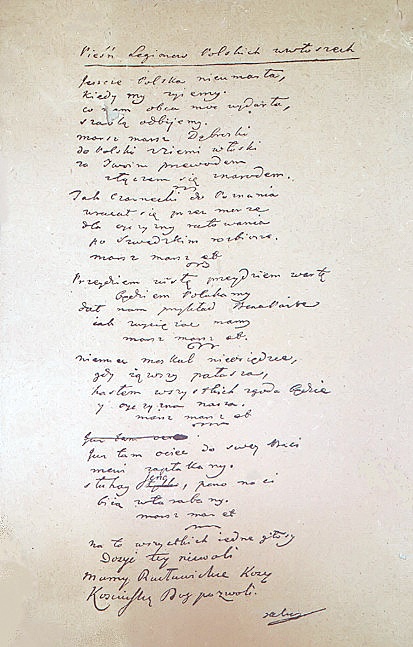

. The official lyrics, based on a variant from 1806, "Poland has not yet died"suggesting a more violent cause of the nation's possible death. Wybicki's original manuscript was in the hands of his descendants until February 1944, when it was lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

*Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

*Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

in Wybicki's great-great-grandson, Johann von Roznowski's home in Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Prussia, it is best known for Charlottenburg Palace, the la ...

during the Allied bombing of Berlin. The manuscript is known today only from facsimile

A facsimile (from Latin ''fac simile'', "to make alike") is a copy or reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or other item of historical value that is as true to the original source as possible. It differs from other forms of ...

copies, twenty four of which were made in 1886 by Edward Rożnowski, Wybicki's grandson, who donated them to Polish libraries.

The main theme of the poem is the idea that was novel in the times of early nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

s based on centralized nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may in ...

sthat the lack of political sovereignty does not preclude the existence of a nation. As Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish ...

explained in 1842 to students of Slavic Literature in Paris, the song "The famous song of the Polish legions begins with lines that express the new history: Poland has not perished yet as long as we live. These words mean that people who have in them what constitutes the essence of a nation can prolong the existence of their country regardless of its political circumstances and may even strive to make it real again..." The song also includes a call to arms and expresses the hope that, under General Dąbrowski's command, the legionaries would rejoin their nation and retrieve "what the alien force has seized" through armed struggle.

The chorus and subsequent stanzas include heart-lifting examples of military heroes, set as role models for Polish soldiers:

The chorus and subsequent stanzas include heart-lifting examples of military heroes, set as role models for Polish soldiers: Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (; also known as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski (Dombrowski) in German and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French; 2 August 1755 – 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patrio ...

, Napoleon, Stefan Czarniecki

Stefan Czarniecki (Polish: of the Łodzia coat of arms, 1599 – 16 February 1665) was a Polish nobleman, general and military commander. In his career, he rose from a petty nobleman to a magnate holding one of the highest offices in the Comm ...

and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

. Dąbrowski, for whom the anthem is named, was a commander in the failed 1794 Kościuszko Uprising

The Kościuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794 and the Second Polish War, was an uprising against the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia led by Tadeusz Kościuszko in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Pr ...

against Russia. After the Third Partition in 1795, he came to Paris to seek French aid in re-establishing Polish independence and, in 1796, he started the formation of the Polish Legions, a Polish unit of the French Revolutionary Army. Bonaparte was, at the time when the song was written, a commander of the Italian campaign of French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

and Dąbrowski's superior. Having already proven his skills as a military leader, he is described in the lyrics as the one "who has shown us ways to victory." Bonaparte is the only non-Polish person mentioned by name in the Polish anthem.

Stefan Czarniecki was a 17th-century

Stefan Czarniecki was a 17th-century hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military ...

, famous for his role in driving the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used b ...

army out of Poland after an occupation that had left the country in ruins and is remembered by Poles as the Deluge

A deluge is a large downpour of rain, often a flood.

The Deluge refers to the flood narrative in the Biblical book of Genesis.

Deluge may also refer to:

History

*Deluge (history), the Swedish and Russian invasion of the Polish-Lithuanian Comm ...

. With the outbreak of a Dano-Swedish War

Dano-Swedish War may refer to one of multiple wars which took place between the Kingdom of Sweden and the Kingdom of Denmark (from 1450 in personal union with the Kingdom of Norway) up to 1814:

List of wars Legendary wars between Denmark an ...

, he continued his fight against Sweden in Denmark, from where he "returned across the sea" to fight the invaders alongside the king who was then at the Royal Castle in Poznań

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

. In the same castle, Józef Wybicki, started his career as a lawyer (in 1765). Kościuszko, mentioned in a stanza now missing from the anthem, became a hero of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

before coming back to Poland to defend his native country from Russia in the war of 1792

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

and a national uprising he led in 1794. One of his major victories during the uprising was the Battle of Racławice

The Battle of Racławice was one of the first battles of the Polish-Lithuanian Kościuszko Uprising against Russia. It was fought on 4 April 1794 near the village of Racławice in Lesser Poland.Storozynski, A., 2009, The Peasant Prince, New ...

where the result was partly due to Polish peasants armed with scythes

Scythes ( grc, Σκύθης, ''Skýthi̱s'') was tyrant or ruler of Zancle in Sicily. He was appointed to that post in about 494 BC by Hippocrates of Gela.

The Zanclaeans had contacted Ionian leaders to invite colonists to join them in founding ...

. Alongside the scythes, the song mentioned other types of weaponry, traditionally used by the Polish ''szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in ...

'', or nobility: the sabre

A sabre (French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as the ...

, known in Polish as ''szabla

(; plural: ) is the Polish word for sabre.

The sabre was in widespread use in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Early Modern period, especially by light cavalry in the 17th century. The sabre became widespread in Europe foll ...

'', and the backsword

A backsword is a type of sword characterised by having a single-edged blade and a hilt with a single-handed grip. It is so called because the triangular cross section gives a flat back edge opposite the cutting edge. Later examples often have a " ...

.

Basia (a female name, diminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A ( abbreviated ) is a word-form ...

of Barbara

Barbara may refer to:

People

* Barbara (given name)

* Barbara (painter) (1915–2002), pseudonym of Olga Biglieri, Italian futurist painter

* Barbara (singer) (1930–1997), French singer

* Barbara Popović (born 2000), also known mononymously as ...

) and her father are fictional characters. They are used to represent the women and elderly men who waited for the Polish soldiers to return home and liberate their fatherland. The route that Dąbrowski and his legions hoped to follow upon leaving Italy is hinted at by the words "we'll cross the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in t ...

, we'll cross the Warta

The river Warta ( , ; german: Warthe ; la, Varta) rises in central Poland and meanders greatly north-west to flow into the Oder, against the German border. About long, it is Poland's second-longest river within its borders after the Vistula, a ...

", two major rivers flowing through the parts of Poland that were in Austrian and Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

hands at the time.

Music

The melody of the Polish anthem is a lively and rhythmicalmazurka

The mazurka (Polish: ''mazur'' Polish ball dance, one of the five Polish national dances and ''mazurek'' Polish folk dance') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dances in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo, with character de ...

. Mazurka as a musical form derives from the stylization of traditional melodies for the folk dances of Mazovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centuri ...

, a region in central Poland. It is characterized by a triple meter

Triple metre (or Am. triple meter, also known as triple time) is a musical metre characterized by a ''primary'' division of 3 beats to the bar, usually indicated by 3 ( simple) or 9 ( compound) in the upper figure of the time signature, with , , ...

and strong accents placed irregularly on the second or third beat. Considered one of Poland's national dances in pre-partition times, it owes its popularity in 19th-century West European ballrooms to the mazurkas

The mazurka (Polish: ''mazur'' Polish ball dance, one of the five Polish national dances and ''mazurek'' Polish folk dance') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dances in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo, with character de ...

of Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; 1 March 181017 October 1849) was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic period, who wrote primarily for solo piano. He has maintained worldwide renown as a leadin ...

.

The composer of "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" is unknown. The melody is most probably Wybicki's adaptation of a folk tune that had already been popular during the second half of the 18th century. The composition used to be erroneously attributed to Michał Kleofas Ogiński

Michał Kleofas Ogiński (25 September 176515 October 1833) was a Polish diplomat and politician, Grand Treasurer of Lithuania, and a senator of Tsar Alexander I. He was also a composer of early Romantic music.

Early life

Ogiński was born in ...

who was known to have written a march

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March ...

for Dąbrowski's legions. Several historians confused Ogiński's "" ("March for the Polish Legions") with Wybicki's mazurka, possibly due to the mazurka's chorus "March, march, Dąbrowski", until Ogiński's sheet music for the march was discovered in 1938 and proven to be a different piece of music than Poland's national anthem.

The first composer to use the anthem for an artistical music piece is always stated to be Karol Kurpiński

Karol Kazimierz Kurpiński (March 6, 1785September 18, 1857) was a Polish composer, conductor and pedagogue. He was a representative of late classicism and a member of the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning ( Polish: ''Towarzystwo Warszaw ...

. In 1821 he composed his piano/organ Fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the co ...

on "Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła" (it was published in 1821 in Warsaw; the first modern edition by Rostislaw Wygranienko

Rostisław Wygranienko (born 1978 in Simferopol, Ukraine) is a Polish concert organist, pianist and musicologist of Ukrainian origin. In 2003 he graduated from the Fryderyk Chopin Music Academy, Warsaw (Master of Arts with "excellent degree" dip ...

was printed only in 2009). However, Karol Lipiński

Karol Józef Lipiński (30 October 1790 – 16 December 1861) was a Polish music composer and virtuoso violinist active during the partitions of Poland. The Karol Lipiński University of Music in Wrocław, Poland is named after him.

Life

...

used it in an overture for his opera ''Kłótnia przez zakład

''Kłótnia przez zakład'' (Polish language, Polish for ''A Dispute over a Bet'') is a one-act comic opera by Karol Lipiński for a Polish libretto by . It was written by Lipiński at an early point of his career, when he was a resident of Lwów ...

'' composed and staged in Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukra ...

ca.1812.

was the next who arranged "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" for the piano. The arrangement, accompanied by the lyrics in Polish and French, was published 1829 in Paris. German composers who were moved by the suffering of the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in ...

wove the mazurek into their works. Examples include Richard Wagner's Polonia Overture and Albert Lortzing

Gustav Albert Lortzing (23 October 1801 – 21 January 1851) was a German composer, librettist, actor and singer. He is considered to be the main representative of the German '' Spieloper'', a form similar to the French ''opéra comique'', whic ...

's ''Der Pole und sein Kind''.

The current official musical score of the national anthem was arranged by Kazimierz Sikorski

Kazimierz Sikorski (June 28, 1895 – July 23, 1986) was a Polish composer. His arrangement of the "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" is currently used as the Polish national anthem.

Biography

Sikorski was born in Zurich, but studied in Warsaw, first m ...

and published by the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage

Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego) is a governmental administration office concerned with various aspects of Polish culture. It was formed on 31 October 20 ...

. Sikorski's harmonization allows for each vocal version to be performed either '' a cappella'' or together with any of the instrumental versions. Some orchestra parts, marked in the score as ''ad libitum

In music and other performing arts, the phrase (; from Latin for 'at one's pleasure' or 'as you desire'), often shortened to "ad lib" (as an adjective or adverb) or "ad-lib" (as a verb or noun), refers to various forms of improvisation.

The ...

'', may be left out or replaced by other instruments of equivalent musical scale.

In 1908, Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versail ...

, later to become the first Prime Minister of independent Poland, quoted the anthem in a disguised way in his Symphony in B minor "Polonia". He scored it in duple meter

Duple metre (or Am. duple meter, also known as duple time) is a musical metre characterized by a ''primary'' division of 2 beats to the bar, usually indicated by 2 and multiples ( simple) or 6 and multiples ( compound) in the upper figure of the t ...

rather than its standard triple meter.

The anthem was quoted by Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

in his symphonic prelude '' Polonia'', composed in 1915.

Regulations

The national anthem is, along with thenational coat of arms

A national coat of arms is a symbol which denotes an independent state in the form of a heraldic achievement. While a national flag is usually used by the population at large and is flown outside and on ships, a national coat of arms is normally ...

and the national colors

National colours are frequently part of a country's set of national symbols. Many states and nations have formally adopted a set of colours as their official "national colours" while others have ''de facto'' national colours that have become well ...

, one of three national symbols defined by the Polish constitution

The current Constitution of Poland was founded on 2 April 1997. Formally known as the Constitution of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), it replaced the Small Constitution of 1992, the last amended version of ...

.

. For English translation seeConstitution of the Republic of Poland

As such, it is protected by law which declares that treating the national symbols "with reverence and respect" is the "right and obligation" of every Polish citizen and all state organs, institutions and organizations. The anthem should be performed or reproduced especially at celebrations of national holidays and anniversaries. Civilians should pay respect to the anthem by standing in a dignified manner; additionally, men should uncover their heads. Members of uniformed services should stand at attention; if their uniform includes headgear and they are not standing in an organized group, they should also perform the

two-finger salute

The two-finger salute is a salute given using only the middle and index fingers, while bending the other fingers at the second knuckle, and with the palm facing the signer. This salute is used by the Polish Armed Forces, other uniformed services ...

. The song is required to be played in the key of F-major if played for a public purpose. Color guard

In military organizations, a colour guard (or color guard) is a detachment of soldiers assigned to the protection of regimental colours and the national flag. This duty is so prestigious that the military colour is generally carried by a young o ...

s pay respect to the anthem by dipping their banners.

History

Origin

In 1795, after a prolonged decline and despite last-minute attempts at constitutional reforms and armed resistance, the

In 1795, after a prolonged decline and despite last-minute attempts at constitutional reforms and armed resistance, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

was ultimately partitioned by its three neighbors: Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. A once vast and powerful empire was effectively erased from the map while monarchs of the partitioning powers pledged never to use the name "Poland" in their official titles. For many, including even leading representatives of the Polish Enlightenment

The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment in Poland were developed later than in Western Europe, as the Polish bourgeoisie was weaker, and szlachta (nobility) culture (Sarmatism) together with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth political system (Go ...

, this new political situation meant an end of the Polish nation. In the words of Hugo Kołłątaj

Hugo Stumberg Kołłątaj, also spelled ''Kołłątay'' (pronounced , 1 April 1750 – 28 February 1812), was a prominent Polish constitutional reformer and educationalist, and one of the most prominent figures of the Polish Enlightenment. He s ...

, a notable Polish political thinker of the time, "Poland no longer belonged to currently extant nations," while historian Tadeusz Czacki

Tadeusz Czacki (28 August 1765 in Poryck, Volhynia – 8 February 1813 in Dubno) was a Polish historian, pedagogue and numismatist. Czacki played an important part in the Enlightenment in Poland.

Biography

Czacki was born in Poryck in Volhynia, ...

declared that Poland "was now effaced from the number of nations."

Meanwhile, Polish patriots and revolutionaries turned for help to

Meanwhile, Polish patriots and revolutionaries turned for help to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, Poland's traditional ally, which was at war with Austria (member of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

) at the time. Józef Wybicki

Józef Rufin Wybicki (; 29 September 1747 – 10 March 1822) was a Polish nobleman, jurist, poet, political and military activist of Kashubian descent. He is best remembered as the author of "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" (), which was adopted as the P ...

was among the leading moderate émigré politicians seeking French aid in re-establishing Polish independence. In 1796, he came up with the idea of creating Polish Legions within the French Revolutionary Army

The French Revolutionary Army (french: Armée révolutionnaire française) was the French land force that fought the French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1804. These armies were characterised by their revolutionary fervour, their poor equipmen ...

. To this end, he convinced General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski (; also known as Johann Heinrich Dąbrowski (Dombrowski) in German and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French; 2 August 1755 – 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patrio ...

, a hero of the Greater Poland campaign of the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising

The Kościuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794 and the Second Polish War, was an uprising against the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia led by Tadeusz Kościuszko in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Pr ...

, to come to Paris and present the plan to the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced ...

. Dąbrowski was sent by the Directory to Napoleon who was then spreading the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

in northern Italy. In January 1797, the newly created French-controlled Cisalpine Republic

The Cisalpine Republic ( it, Repubblica Cisalpina) was a sister republic of France in Northern Italy that existed from 1797 to 1799, with a second version until 1802.

Creation

After the Battle of Lodi in May 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte organized ...

accepted Dąbrowski's offer and a Polish legion was formed. Dąbrowski and his soldiers hoped to fight against Austria under Napoleon and, subsequently, march across the Austrian territory, "from Italy to Poland", where they would ignite a national uprising.

In early July 1797, Wybicki arrived in Reggio Emilia where the Polish Legions were then quartered and where he wrote the ''Song of the Polish Legions'' soon afterwards. He first sung it at a private meeting of Polish officers in the Legions' headquarters at the episcopal palace in Reggio. The first public performance most probably took place on 16 July 1797 during a military parade in Reggio's Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral Square). On 20 July, it was played again as the Legions were marching off from Reggio to

In early July 1797, Wybicki arrived in Reggio Emilia where the Polish Legions were then quartered and where he wrote the ''Song of the Polish Legions'' soon afterwards. He first sung it at a private meeting of Polish officers in the Legions' headquarters at the episcopal palace in Reggio. The first public performance most probably took place on 16 July 1797 during a military parade in Reggio's Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral Square). On 20 July, it was played again as the Legions were marching off from Reggio to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard language, Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the List of cities in Italy, second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 ...

, the Cisalpine capital.

With its heart-lifting lyrics and folk melody, the song soon became a popular tune among Polish legionaries. On 29 August 1797, Dąbrowski already wrote to Wybicki from Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

: "soldiers gain more and more taste for your song." It appealed to both officers, usually émigré noblemen, and simple soldiers, most of whom were Galician peasants who had been drafted into the Austrian army and captured as POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

by the French. The last stanza, referring to Kościuszko, who famously fought for freedom of the entire nation rather than the nobility alone, and the "scythes of Racławice", seems to be directed particularly at the latter. Wybicki may have even hoped for Kościuszko to arrive in Italy and personally lead the Legions which might explain why the chorus "March, march, Dąbrowski" is not repeated after the last stanza. At that time Wybicki was not yet aware that Kościuszko had already returned to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

.

Rising popularity

The song became popular in Poland as soon as late 1797 and quickly became an object of variations and modifications. A variant from 1798 introduced some stylistic changes, which have since become standard, such as replacing ' ("not dead") with ' ("not perished") or ' ("to Poland from the Italian land") with ' ("from the Italian land to Poland"). It also added four new stanzas, now forgotten, written from the viewpoint of Polish patriots waiting for General Dąbrowski to bring freedom and human rights to Poland. The ultimate fate of the Polish Legions in Italy was different from that promised by Wybicki's song. Rather than coming back to Poland, they were exploited by the French government to quell uprisings in Italy, Germany and, later, in

The ultimate fate of the Polish Legions in Italy was different from that promised by Wybicki's song. Rather than coming back to Poland, they were exploited by the French government to quell uprisings in Italy, Germany and, later, in Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

where they were decimated by war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

and disease. Polish national hopes were revived with the outbreak of a Franco-Prussian war (part of the War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, ...

) in 1806. Napoleon called Dąbrowski and Wybicki to come back from Italy and help gather support for the French army in Polish-populated parts of Prussia. On 6 November 1806, both generals arrived in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, enthusiastically greeted by locals singing "Poland Is Not Yet Lost". The ensuing Greater Poland Uprising and Napoleon's victory over Russian forces at Friedland

Friedland may refer to:

Places

Czech Republic

* Frýdlant v Čechách (''Friedland im Isergebirge'')

* Frýdlant nad Ostravicí (''Friedland an der Ostrawitza'')

* Frýdlant nad Moravicí (''Friedland an der Mohra'')

France

* , street in P ...

led to the creation of a French-controlled Polish puppet state known as the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

.

"Poland Is Not Yet Lost" was one of the most popular patriotic songs in the duchy, stopping short of becoming that entity's national anthem. Among other occasions, it was sung in Warsaw on 16 June 1807 to celebrate the battle of Friedland, in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 159 ...

as it was liberated by Prince Józef Poniatowski

Prince Józef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 – 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), P ...

on 19 July 1809, and at a ball in Warsaw on 23 December 1809, the birthday of Frederick Augustus, King of Saxony and Duke of Warsaw. On the occasion of Dąbrowski's name day

In Christianity, a name day is a tradition in many countries of Europe and the Americas, among other parts of Christendom. It consists of celebrating a day of the year that is associated with one's baptismal name, which is normatively that of ...

on 25 December 1810 in Poznań, Dąbrowski and Wybicki led the mazurka to the tune of "Poland Is Not Yet Lost". Although the melody of Wybicki's song remained unchanged and widely known, the lyrics kept changing. With the signing of a Franco-Russian alliance at Tilsit

Sovetsk (russian: Сове́тск; german: Tilsit; Old Prussian: ''Tilzi''; lt, Tilžė; pl, Tylża) is a town in Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the south bank of the Neman River which forms the border with Lithuania.

Geography

...

in 1807, the fourth stanza, specifically mentioning Russians as Poland's enemies, was removed. The last stanza, referring to Kościuszko, who had grown suspicious of Napoleon and refused to lend his support to the emperor's war in Poland, met the same fate.

The anthem is mentioned twice in ''Pan Tadeusz

''Pan Tadeusz'' (full title: ''Mister Thaddeus, or the Last Foray in Lithuania: A Nobility's Tale of the Years 1811–1812, in Twelve Books of Verse'') is an epic poem by the Polish poet, writer, translator and philosopher Adam Mickiewicz. The ...

'', the Polish national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with a ...

written by Adam Mickiewicz in 1834, but set in the years 1811–1812. The author makes the first reference to the song when Tadeusz, the main protagonist, returns home and, recalling childhood memories, pulls the string of a chiming clock to hear the "old Dąbrowski's Mazurka" once again. Musical box

A music box (American English) or musical box (British English) is an automatic musical instrument in a box that produces musical notes by using a set of pins placed on a revolving cylinder or disc to pluck the tuned teeth (or ''lamellae'' ...

es and musical clock

A musical clock is a clock that marks the hours of the day with a musical tune. They can be considered elaborate versions of striking or chiming clocks.

Elaborate large-scale musical clocks with automatons are often installed in public places ...

s playing the melody of ''Poland Is Not Yet Lost'' belonged to popular patriotic paraphernalia of that time. The song appears in the epic poem again when Jankiel, a Jewish dulcimerist and ardent Polish patriot, plays the mazurka in the presence of General Dąbrowski himself.

With Napoleon's defeat and the

With Napoleon's defeat and the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815 came a century of foreign domination over Poland interspersed with occasional bursts of armed rebellion. ''Poland Is Not Yet Lost'' continued to be sung throughout that period, especially during national uprisings. During the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in ...

against Russia in 1830–1831, the song was chanted in the battlefields of Stoczek, Olszynka Grochowska and Iganie. In peacetime, Polish patriots performed it at homes, official functions and political demonstrations. New variants of the song, of various artistic value and length of life, abounded. At least 16 alternative versions were penned during the November Uprising alone. At times, Dąbrowski's name was replaced by other national heroes: from Józef Chłopicki

Józef Grzegorz Chłopicki (; 14 March 1771 – 30 September 1854) was a Polish general who was involved in fighting in Europe at the time of Napoleon and later.

He was born in Kapustynie in Volhynia and was educated at the school of the Ba ...

during the November Uprising to Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

during the First World War to Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Prior to the First World War, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause for Polish ...

during the Second World War. New lyrics were also written in regional dialects of Polish, from Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is spli ...

to Ermland and Masuria

Masuria (, german: Masuren, Masurian: ''Mazurÿ'') is a ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the ...

. A variant known as ''Marsz Polonii'' ("March Polonia") spread among Polish immigrants in the Americas.

Mass political emigration following the defeat of the November Uprising, known as the Great Emigration

The Great Emigration ( pl, Wielka Emigracja) was the emigration of thousands of Poles and Lithuanians, particularly from the political and cultural élites, from 1831 to 1870, after the failure of the November Uprising of 1830–1831 and of oth ...

, brought ''Poland Is Not Yet Lost'' to Western Europe. It soon found favor from Britain to France to Germany where it was performed as a token of sympathy with the Polish cause. It was also highly esteemed in Central Europe where various, mostly Slavic

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slavi ...

, peoples struggling for their own independence, looked to the Polish anthem for inspiration. Back in Poland, however, especially in the parts under Russian and Prussian rule, it was becoming increasingly risky to sing the anthem in public. Polish patriotic songs were banned in Prussia in 1850; between 1873 and 1911, German courts passed 44 sentences for singing such songs, 20 of which were specifically for singing ''Poland Is Not Yet Lost''. In Russian Poland, public performance of the song often ended with a police intervention.

Choice of national anthem

When Poland re-emerged as an independent state after World War I in 1918, it had to make a decision about its national symbols. While the coat of arms and the flag were officially adopted as soon as 1919, the question of a national anthem had to wait. Apart from "Poland Is Not Yet Lost", there were other popular patriotic songs which could compete for the status of an official national anthem. In the Middle Ages, the role of a national anthem was played by hymns. Among them were ''

In the Middle Ages, the role of a national anthem was played by hymns. Among them were ''Bogurodzica

]

Bogurodzica (, calque of the Greek term ''Theotokos''), in English known as the Mother of God, is a medieval Roman Catholic hymn composed sometime between the 10th and 13th centuries in Poland. It is believed to be the oldest religious hymn or p ...

'' (), one of the oldest (11th–12th century) known literary texts in Polish, and the Latin ''Gaude Mater Polonia

''Gaude Mater Polonia'' (Medieval Latin for "Rejoice, oh Mother Poland"; , Polish: Raduj się, matko Polsko) was one of the most significant medieval Polish hymns, written in Latin between the 13th and the 14th century to commemorate Saint Stan ...

'' ("Rejoice, Mother Poland"), written in the 13th century to celebrate the canonization of Bishop Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów ( pl, Stanisław ze Szczepanowa; 26 July 1030 – 11 April 1079) was Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish king Bolesław II the Generous. Stanislaus is venerated in the Roman C ...

, the patron saint of Poland. Both were chanted on special occasions and on battlefields. The latter is sung nowadays at university ceremonies. During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

and the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, several songs, both religious and secular, were written with the specific purpose of creating a new national anthem. Examples include the 16th-century Latin prayer ' ("Prayer for the Commonwealth and the King") by a Calvinist poet, Andrzej Trzeciński, and "" ("Hymn to the Love of the Fatherland") written in 1744 by Prince-Bishop Ignacy Krasicki

Ignacy Błażej Franciszek Krasicki (3 February 173514 March 1801), from 1766 Prince-Bishop of Warmia (in German, ''Ermland'') and from 1795 Archbishop of Gniezno (thus, Primate of Poland), was Poland's leading Enlightenment poet"Ignacy Krasic ...

. They failed, however, to win substantial favor with the populace. Another candidate was "" ("God is Born"), whose melody was originally a 16th-century coronation polonaise (dance)

The polonaise (, ; pl, polonez ) is a dance of Polish origin, one of the five Polish national dances in time. Its name is French for "Polish" adjective feminine/"Polish woman"/"girl". The original Polish name of the dance is Chodzony, meani ...

for Polish kings.

The official anthem of the Russian-controlled Congress Kingdom of Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

was "" ( "National Song to the King's Well-being") written in 1816 by Alojzy Feliński

Alojzy Feliński (1771 – 1820) was a Polish writer.

Life

Feliński was born in Łuck. In his childhood he met Tadeusz Czacki. He was educated by the Piarists in Dąbrownica, later in Włodzimierz Wołyński. In 1778 he settled in Lubli ...

and Jan Kaszewski. Initially unpopular, it evolved in the early 1860s into an important religious and patriotic hymn. The final verse, which originally begged "Save, Oh Lord, our King", was substituted with "Return us, Oh Lord, our free Fatherland" while the melody was replaced with that of a Marian hymn. The result, known today as "" ("God Save Poland"), has been sung in Polish churches ever since, with the final verse alternating between "Return..." and "Bless, Oh Lord, our free Fatherland", depending on Poland's political situation.

A national song that was particularly popular during the November Uprising was " Warszawianka", originally written in French as "" by Casimir Delavigne

Jean-François Casimir Delavigne (4 April 179311 December 1843) was a French poet and dramatist.

Life and career

Delavigne was born at Le Havre, but was sent to Paris to be educated at the Lycée Napoleon. He read extensively. When, on 20 March ...

, with melody by Karol Kurpiński

Karol Kazimierz Kurpiński (March 6, 1785September 18, 1857) was a Polish composer, conductor and pedagogue. He was a representative of late classicism and a member of the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning ( Polish: ''Towarzystwo Warszaw ...

. The song praised Polish insurgents taking their ideals from the French July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

of 1830. A peasant rebellion against Polish nobles, which took place in western Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

in 1846 and was encouraged by Austrian authorities who wished to thwart a new uprising attempt, moved Kornel Ujejski

Kornel Ujejski (; September 12, 1823 in Beremyany, Galicia, Austria - September 19, 1897 in Pavliv near Lviv, Galicia, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Centra ...

to write a mournful chorale

Chorale is the name of several related musical forms originating in the music genre of the Lutheran chorale:

* Hymn tune of a Lutheran hymn (e.g. the melody of " Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme"), or a tune in a similar format (e.g. one of the ...

entitled "" ("With the Smoke of Fires"). With the music composed by , it became one of the most popular national songs of the time, although it declined into obscurity during the 20th century. In 1908, Maria Konopnicka

Maria Konopnicka (; ; 23 May 1842 – 8 October 1910) was a Polish poet, novelist, children's writer, translator, journalist, critic, and activist for women's rights and for Polish independence. She used pseudonyms, including ''Jan Sawa''. Sh ...

and Feliks Nowowiejski

Feliks Nowowiejski (7 February 1877 – 18 January 1946) was a Polish composer, conductor, concert organist, and music teacher. Nowowiejski was born in Wartenburg (today Barczewo) in Warmia in the Prussian Partition of Poland (then admin ...

created "Rota

Rota or ROTA may refer to:

Places

* Rota (island), in the Marianas archipelago

* Rota (volcano), in Nicaragua

* Rota, Andalusia, a town in Andalusia, Spain

* Naval Station Rota, Spain

People

* Rota (surname), a surname (including a list of peop ...

" ("The Oath"), a song protesting against the oppression of the Polish population of the German Empire, who were subject to eviction from their land and forced assimilation. First publicly performed in 1910, during a quincentennial celebration of the Polish–Lithuanian victory over the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

at Grunwald, it too became one of the most treasured national Polish songs.

At the inauguration of the UN in 1945, no delegation from Poland had been invited. The Polish pianist Artur Rubinstein

Arthur Rubinstein ( pl, Artur Rubinstein; 28 January 188720 December 1982) was a Polish-American pianist.

, who was to perform the opening concert at the inauguration, began the concert by stating his deep disappointment that the conference did not have a delegation from Poland. Rubinstein later described becoming overwhelmed by a blind fury and angrily pointing out to the public the absence of the Polish flag

The national flag of Poland ( pl, flaga Polski) consists of two horizontal stripes of equal width, the upper one white and the lower one red. The two colours are defined in the Polish constitution as the national colours. A variant of the fl ...

. He then sat down to the piano and played "Poland Is Not Yet Lost" loudly and slowly, repeating the final part in a great thunderous ''forte''. When he had finished, the public rose to their feet and gave him a great ovation.

Over 60 years later, on 2005-09-22, Aleksander Kwaśniewski

Aleksander Kwaśniewski (; born 15 November 1954) is a Polish politician and journalist. He served as the President of Poland from 1995 to 2005. He was born in Białogard, and during communist rule, he was active in the Socialist Union of P ...

, President of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Polan ...

, said:

Influence

During the EuropeanRevolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Euro ...

, "Poland Is Not Yet Lost" won favor throughout Europe as a revolutionary anthem. This led the Slovak poet Samo Tomášik

Samo Tomášik ( hu, Tomasik Sámuel; pseudonyms Kozodolský, Tomášek; February 8, 1813 – September 10, 1887) was a Slovak romantic poet and prosaist.

He was best known for writing the 1834 poem, "Hej, Slováci", which was in use since 194 ...

to write the ethnic anthem, " Hej, Sloveni", based on the melody of the Polish national anthem. It was later adopted by the First Congress of the Pan-Slavic Movement in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

as the Pan-Slavic Anthem. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, a translation of this anthem became the national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and Europe ...

of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

, and later, Serbia and Montenegro

Serbia and Montenegro ( sr, Cрбија и Црна Гора, translit=Srbija i Crna Gora) was a country in Southeast Europe located in the Balkans that existed from 1992 to 2006, following the breakup of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yu ...

. The similarity of the anthems sometimes caused confusion during these countries' football or volleyball matches. However, after the 2006 split between the two, neither Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

nor Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

kept the song as its national anthem, instead choosing "Bože pravde

"" ( sr-Cyrl, Боже правде, , "God of Justice") is the national anthem of Serbia, as defined by the Article 7 of the Constitution of Serbia. "Bože pravde" was the state anthem of the Kingdom of Serbia until 1919 when Serbia became a pa ...

" and "Oj, svijetla majska zoro

"" ( Cyrillic: "", ; "Oh, Bright Dawn of May") is the national anthem of Montenegro adopted in 2004. Before its adoption, it was a popular folk song with many variations of its text. The oldest version dates back to the second half of the 19th ce ...

" respectively. The Polish national anthem is also notable for influencing the lyrics of the Ukrainian anthem, "Shche ne vmerla Ukrayina

"" ( uk, Ще не вмерла України і слава, і воля, , lit=The glory and freedom of Ukraine has not yet perished), also known by its official title of "State Anthem of Ukraine" (, ') or by its shortened form "" (, ), is the ...

" (''Ukraine's glory has not yet perished'').

The line "Poland is not lost yet" has become proverbial in some languages. For example, in German, ''noch ist Polen nicht verloren

Noch may refer to:

*Noch (model railroads), a model railroad company

* ''Noch'' (album), a 1986 album by Kino

*Noch, Iran

Noj ( fa, نج; also known as Noch) is a village in Tatarestaq Rural District, Baladeh District, Nur County, Mazandaran ...

'' is a common saying meaning "all is not lost".

Additionally, the Italian anthem, Il Canto degli Italiani

"" (; "The Song of the Italians") is a canto written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro in 1847, and is the current national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as the "" (, "Mameli's Hymn"), after the author o ...

, contains a reference to the Partitions of Poland by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, due to the close relations between the two countries.

Notes

References

Further reading

* *External links

Poland: "Mazurek Dąbrowskiego" (Poland Is Not Yet Lost)

Audio, information, lyrics

archive link

Museum of the National Anthem at Będomin

– A museum dedicated to the National Anthem (Polish)

– The promotional website "Polska" features a page on the anthem with an instrumental version.

Hymn Polski

– The website for the Center for Citizenship Education features a page on the anthem than includes vocal and instrumental versions.

– A copy of the oldest known recording of the anthem, 1926 by Ignacy Dygas, is available here.

Russian-Records.com

– Edison phonograph cylinder record performed by Stanisław Bolewski. It is probably the oldest recording of the anthem. {{Authority control 1797 compositions National anthems National symbols of Poland Polish patriotic songs Italy–Poland relations Polish Legions (Napoleonic period) European anthems Polish nationalism (1795–1918) 1797 in Poland National anthem compositions in F major Mazurka