Masonic Buildings Completed In 1888 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of

The

The

''United Grand Lodge of England'' retrieved 30 October 2013 or receive a lecture, which is usually on some aspect of Masonic history or ritual. At the conclusion of the meeting, the Lodge may hold a

H. L. Haywood, ''Symbolical Masonry'', 1923, Chapter XVIII, ''Sacred Texts'' website, retrieved 9 January 2014 Another ceremony is the annual installation of the Master of the Lodge and his appointed or elected officers. In some jurisdictions an ''Installed Master'' elected, obligated and invested to preside over a Lodge, is valued as a separate rank with its own secrets and distinctive title and attributes; after each full year in the Chair the Master invests his elected successor and becomes a Past Master with privileges in the Lodge and Grand Lodge. In other jurisdictions, the grade is not recognised, and no inner ceremony conveys new secrets during the installation of a new Master of the Lodge. Most Lodges have some sort of social functions, allowing members, their partners and non-Masonic guests to meet openly. Often coupled with these events is the discharge of every Mason's and Lodge's collective obligation to contribute to charity. This occurs at many levels, including in annual dues, subscriptions, fundraising events, Lodges and Grand Lodges. Masons and their charities contribute for the relief of need in many fields, such as education, health and old age. Private Lodges form the backbone of Freemasonry, with the sole right to elect their own candidates for initiation as Masons or admission as joining Masons, and sometimes with exclusive rights over residents local to their premises. There are non-local Lodges where Masons meet for wider or narrower purposes, such or in association with some hobby, sport, Masonic research, business, profession, regiment or college. The rank of Master Mason also entitles a Freemason to explore Masonry further through other degrees, administered separately from the basic Craft or "Blue Lodge" degrees described here, but generally having a similar structure and meetings.Michael Johnstone, ''The Freemasons'', Arcturus, 2005, pp. 101–120 There is much diversity and little consistency in Freemasonry, because each Masonic jurisdiction is independent and sets its own rules and procedures while Grand Lodges have limited jurisdiction over their constituent member Lodges, which are ultimately private clubs. The wording of the ritual, the number of officers present, the layout of the meeting room, etc. varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

''Maconnieke Encyclopedie'', retrieved 31 October 2013 Almost all officers of a Lodge are elected or appointed annually. Every Masonic Lodge has a Master, two Wardens, a treasurer and a secretary. There is also always a

Candidates for Freemasonry will usually have met the most active members of the Lodge they are joining before being elected for initiation. The process varies among Grand Lodges, but in modern times interested people often look up a local Lodge through the Internet and will typically be introduced to a Lodge social function or open evening. The onus is upon candidates to ask to join; while they may be encouraged to ask, they may not be invited. Once the initial inquiry is made, a formal application may be proposed and seconded or announced in open Lodge and a more or less formal interview usually follows. If the candidate wishes to proceed, references are taken up during a period of notice so that members may enquire into the candidate's suitability and discuss it. Finally the Lodge takes an officially secret ballot on each application before a candidate is either initiated or rejected."How to become a Freemason"

Candidates for Freemasonry will usually have met the most active members of the Lodge they are joining before being elected for initiation. The process varies among Grand Lodges, but in modern times interested people often look up a local Lodge through the Internet and will typically be introduced to a Lodge social function or open evening. The onus is upon candidates to ask to join; while they may be encouraged to ask, they may not be invited. Once the initial inquiry is made, a formal application may be proposed and seconded or announced in open Lodge and a more or less formal interview usually follows. If the candidate wishes to proceed, references are taken up during a period of notice so that members may enquire into the candidate's suitability and discuss it. Finally the Lodge takes an officially secret ballot on each application before a candidate is either initiated or rejected."How to become a Freemason"

''Masonic Lodge of Education'', retrieved 20 November 2013 The exact number of adverse ballots (“blackballs”) required to reject a candidate varies between Masonic jurisdictions. As an example, the

Foire aux Questions, ''Grand Orient de France'', Retrieved 23 November 2013

''Pietre-Stones'', retrieved 23 November 2013 During the ceremony of initiation, the candidate is required to undertake an obligation, swearing on the religious volume sacred to his personal faith to do good as a Mason. In the course of three degrees, Masons will promise to keep the secrets of their degree from lower degrees and outsiders, as far as practicality and the law permit, and to support a fellow Mason in distress. There is formal instruction as to the duties of a Freemason, but on the whole, Freemasons are left to explore the craft in the manner they find most satisfying. Some will simply enjoy the dramatics, or the management and administration of the lodge, others will explore the history, ritual and symbolism of the craft, others will focus their involvement on their Lodge's sociopolitical side, perhaps in association with other lodges, while still others will concentrate on the lodge's charitable functions.

Grand Lodges and Grand Orients are independent and sovereign bodies that govern Masonry in a given country, state or geographical area (termed a ''jurisdiction''). There is no single overarching governing body that presides over worldwide Freemasonry; connections between different jurisdictions depend solely on mutual recognition.

Freemasonry, as it exists in various forms all over the world, has a membership estimated at around 6 million worldwide. The fraternity is administratively organised into independent

Grand Lodges and Grand Orients are independent and sovereign bodies that govern Masonry in a given country, state or geographical area (termed a ''jurisdiction''). There is no single overarching governing body that presides over worldwide Freemasonry; connections between different jurisdictions depend solely on mutual recognition.

Freemasonry, as it exists in various forms all over the world, has a membership estimated at around 6 million worldwide. The fraternity is administratively organised into independent

Regularity is a concept based on adherence to

Regularity is a concept based on adherence to

Freemasonry describes itself as a "beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". The symbolism is mainly, but not exclusively, drawn from the tools of stonemasons – the square and compasses, the level and plumb rule, the

Freemasonry describes itself as a "beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". The symbolism is mainly, but not exclusively, drawn from the tools of stonemasons – the square and compasses, the level and plumb rule, the

Since the middle of the 19th century, Masonic historians have sought the origins of the movement in a series of similar documents known as the

Since the middle of the 19th century, Masonic historians have sought the origins of the movement in a series of similar documents known as the  Alternatively,

Alternatively,

Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, vol 79 (1966), p. 270-73, ''Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon'', retrieved 28 June 2012 The

English Freemasonry spread to France in the 1720s, first as lodges of expatriates and exiled

English Freemasonry spread to France in the 1720s, first as lodges of expatriates and exiled

''Phoenix Masonry'', retrieved 5 March 2013 Later organisations with a similar aim emerged in the United States, but distinguished the names of the degrees from those of male masonry.

''Droit Humain'', retrieved 12 August 2013 The United Grand Lodge of England issued a statement in 1999 recognising the two women's grand lodges there, The Order of Women Freemasons and The Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons, to be regular in all but the participants. While they were not, therefore, recognised as regular, they were part of Freemasonry "in general". The attitude of most regular Anglo-American grand lodges remains that women Freemasons are not legitimate Masons. In 2018, guidance was released by the

During the Age of the Enlightenment in the 18th century, Freemasons comprised an international network of like-minded men, often meeting in secret in ritualistic programs at their lodges. They promoted the ideals of the Enlightenment, and helped diffuse these values across Britain and France and other places. British Freemasonry offered a systematic creed with its own myths, values and set of rituals. It fostered new codes of conduct – including a communal understanding of liberty and equality inherited from guild sociability – "liberty, fraternity, and equality" Scottish soldiers and Jacobite Scots brought to the Continent ideals of fraternity which reflected not the local system of Scottish customs but the institutions and ideals originating in the English Revolution against royal absolutism. Freemasonry was particularly prevalent in France – by 1789, there were between 50,000 and 100,000 French Masons, making Freemasonry the most popular of all Enlightenment associations.

Jacob argues that Masonic lodges probably had an effect on society as a whole, for they “reconstituted the polity and established a constitutional form of self-government, complete with constitutions and laws, elections and representatives”. In other words, the micro-society set up within the lodges constituted a normative model for society as a whole. This was especially true on the Continent: when the first lodges began to appear in the 1730s, their embodiment of British values was often seen as threatening by state authorities. For example, the Parisian lodge that met in the mid 1720s was composed of English Jacobite exiles. Furthermore, freemasons all across Europe made reference to the Enlightenment in general in the 18th century. In French lodges, for example, the line “As the means to be enlightened I search for the enlightened” was a part of their initiation rites. British lodges assigned themselves the duty to “initiate the unenlightened”. Many lodges praised the Grand Architect, the masonic terminology for the divine being who created a scientifically ordered universe.

On the other hand, historian

During the Age of the Enlightenment in the 18th century, Freemasons comprised an international network of like-minded men, often meeting in secret in ritualistic programs at their lodges. They promoted the ideals of the Enlightenment, and helped diffuse these values across Britain and France and other places. British Freemasonry offered a systematic creed with its own myths, values and set of rituals. It fostered new codes of conduct – including a communal understanding of liberty and equality inherited from guild sociability – "liberty, fraternity, and equality" Scottish soldiers and Jacobite Scots brought to the Continent ideals of fraternity which reflected not the local system of Scottish customs but the institutions and ideals originating in the English Revolution against royal absolutism. Freemasonry was particularly prevalent in France – by 1789, there were between 50,000 and 100,000 French Masons, making Freemasonry the most popular of all Enlightenment associations.

Jacob argues that Masonic lodges probably had an effect on society as a whole, for they “reconstituted the polity and established a constitutional form of self-government, complete with constitutions and laws, elections and representatives”. In other words, the micro-society set up within the lodges constituted a normative model for society as a whole. This was especially true on the Continent: when the first lodges began to appear in the 1730s, their embodiment of British values was often seen as threatening by state authorities. For example, the Parisian lodge that met in the mid 1720s was composed of English Jacobite exiles. Furthermore, freemasons all across Europe made reference to the Enlightenment in general in the 18th century. In French lodges, for example, the line “As the means to be enlightened I search for the enlightened” was a part of their initiation rites. British lodges assigned themselves the duty to “initiate the unenlightened”. Many lodges praised the Grand Architect, the masonic terminology for the divine being who created a scientifically ordered universe.

On the other hand, historian

First published in M. D. J. Scanlan, ed., ''The Social Impact of Freemasonry on the Modern Western World'', The Canonbury Papers I (London: Canonbury Masonic Research Centre, 2002), pp. 116–34, ''Pietre-Stones'' website, retrieved 9 January 2014 The Grand Masters of both the Moderns and the Antients Grand Lodges called on Prime Minister William Pitt (who was not a Freemason) and explained to him that Freemasonry was a supporter of the law and lawfully constituted authority and was much involved in charitable work. As a result, Freemasonry was specifically exempted from the terms of the Act, provided that each private lodge's Secretary placed with the local "Clerk of the Peace" a list of the members of his lodge once a year. This continued until 1967, when the obligation of the provision was rescinded by In Italy, Freemasonry has become linked to a scandal concerning the

In Italy, Freemasonry has become linked to a scandal concerning the

MPs told to declare links to Masons

, ''

The preserved records of the ''

The preserved records of the ''

online

* Dickie, John. ''The Craft: How the Freemasons Made the Modern World'' (PublicAffairs, 2020)

excerpt

* Fozdar, Vahid. " 'That Grand Primeval and Fundamental Religion': The Transformation of Freemasonry into a British Imperial Cult." ''Journal of World History'' 22#3 (2011), pp. 493–525

online

* Hamill, John. ''The Craft: A History of English Freemasonry'' (1986) * Harland-Jacobs, Jessica L. ''Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927'' (2007) * Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig. ''Freemasonry and German Civil Society, 1840-1918'' (U of Michigan Press, 2007)

excerpt

see als

online review

* Jacob, Margaret C. ''Living the Enlightenment: Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Europe'' (1991

excerpt

* Jacob, Margaret C. ''The Origins of Freemasonry: Facts and Fictions'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2007). * Jacob, Margaret, and Matthew Crow. "Freemasonry and the Enlightenment." in ''Handbook of Freemasonry'' (Brill, 2014) pp. 100–116

online

* Loiselle, Kenneth. "Freemasonry and the Catholic Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century France." ''Journal of Modern History'' 94.3 (2022): 499-536

online

* Önnerfors, Andreas. ''Freemasonry: a very short introduction'' (Oxford University Press, 2017

excerpt

* Racine, Karen. "Freemasonry" in Michael S. Werner, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society, and Culture'' (Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997) 1:538–540. * Snoek Jan A.M. and Henrik Bogdan. "The History of Freemasonry: An Overview" in Bogdan and Snoek, eds. ''Handbook of Freemasonry'' (Brill, 2014) ch. 2 pp 13–32

online

* Stevenson, David. "Four Hundred Years of Freemasonry in Scotland.” ''Scottish Historical Review,'' 90#230 (2011), pp. 280–95

online

* Stevenson, David. ''The First Freemasons. Scotland's Early Lodges and Their Members'' (1988) * Weisberger, R. William et al. '' Freemasonry on Both Sides of the Atlantic: Essays concerning the Craft in the British Isles, Europe, the United States, and Mexico'' (2002), 969pp * Weisberger, R. William. ''Speculative Freemasonry and the Enlightenment: A Study of the Craft in London, Paris, Prague and Vienna'' (Columbia University Press, 1993) 243 pp.

online

* Hackett, David G. ''That Religion in Which All Men Agree : Freemasonry in American Culture'' (U of California Press, 2015

excerpt

* Hinks, Peter P. et al. ''All Men Free and Brethren: Essays on the History of African American Freemasonry '' (Cornell UP, 2013). * Kantrowitz, Stephen. " 'Intended for the Better Government of Man': The Political History of African American Freemasonry in the Era of Emancipation." ''Journal of American History'' 96#4, (2010), pp. 1001–26

online

* Weisberger, R. William et al. '' Freemasonry on Both Sides of the Atlantic: Essays concerning the Craft in the British Isles, Europe, the United States, and Mexico'' (2002), 969pp * York, Neil L. “Freemasons and the American Revolution.” ''Historian'' 55#2 (1993), pp. 315–30

online

online

Web of Hiram

at the University of Bradford. A database of donated Masonic material.

of the ''Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry''

''The Constitutions of the Free-Masons''

(1734), James Anderson, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Royster. Hosted by the Libraries at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

by William Morgan, from

The United Grand Lodge of England's Library and Museum of Freemasonry

, London

Articles on Judaism and Freemasonry

Anti-Masonry: Points of View

– Edward L. King's Masonic website

The International Order of Co-Freemasonry ''Le Droit Humain''

* {{Authority control

stonemasons

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, mo ...

that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities and clients. Modern Freemasonry broadly consists of two main recognition groups:

* Regular Freemasonry insists that a volume of scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

be open in a working lodge, that every member profess belief in a Supreme Being

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, that no women be admitted, and that the discussion of religion and politics be banned.

* Continental Freemasonry

Continental Freemasonry, otherwise known as Liberal Freemasonry, Latin Freemasonry, and Adogmatic Freemasonry, includes the Masonic lodges, primarily on the European continent, that recognize the Grand Orient de France (GOdF) or belong to CLIP ...

consists of the jurisdictions that have removed some, or all, of these restrictions.

The basic, local organisational unit of Freemasonry is the Lodge

Lodge is originally a term for a relatively small building, often associated with a larger one.

Lodge or The Lodge may refer to:

Buildings and structures Specific

* The Lodge (Australia), the official Canberra residence of the Prime Ministe ...

. These private Lodges are usually supervised at the regional level (usually coterminous with a state, province, or national border) by a Grand Lodge

A Grand Lodge (or Grand Orient or other similar title) is the overarching governing body of a fraternal or other similarly organized group in a given area, usually a city, state, or country.

In Freemasonry

A Grand Lodge or Grand Orient is the us ...

or Grand Orient. There is no international, worldwide Grand Lodge that supervises all of Freemasonry; each Grand Lodge is independent, and they do not necessarily recognise each other as being legitimate.

The degrees of Freemasonry retain the three grades of medieval craft guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s, those of Entered Apprentice

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

, Journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

or fellow (now called Fellowcraft), and Master Mason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

. The candidate of these three degrees is progressively taught the meanings of the symbols of Freemasonry and entrusted with grips, signs, and words to signify to other members that he has been so initiated. The degrees are part allegorical morality play

The morality play is a genre of medieval and early Tudor drama. The term is used by scholars of literary and dramatic history to refer to a genre of play texts from the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries that feature personified concepts ( ...

and part lecture. These three degrees form Craft (or Blue Lodge) Freemasonry, and members of any of these degrees are known as Freemasons or Masons. There are additional degrees, which vary with locality and jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

, and are usually administered by their own bodies (separate from those who administer the Craft degrees).

Due to misconceptions about Freemasonry’s tradition of not discussing its rituals with non-members, the fraternity has become associated with many conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

.

Masonic lodge

Masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. The Lodge meets regularly and conducts the usual formal business of any small organisation (approve minutes, elect new members, appoint officers and take their reports, consider correspondence, bills and annual accounts, organise social and charitable events, etc.). In addition to such business, the meeting may perform a ceremony to confer a Masonic degree"Frequently Asked Questions"''United Grand Lodge of England'' retrieved 30 October 2013 or receive a lecture, which is usually on some aspect of Masonic history or ritual. At the conclusion of the meeting, the Lodge may hold a

formal dinner

Dinner usually refers to what is in many Western cultures the largest and most formal meal of the day, which is eaten in the evening. Historically, the largest meal used to be eaten around midday, and called dinner. Especially among the elite, ...

, or ''festive board'', sometimes involving toasting and song.

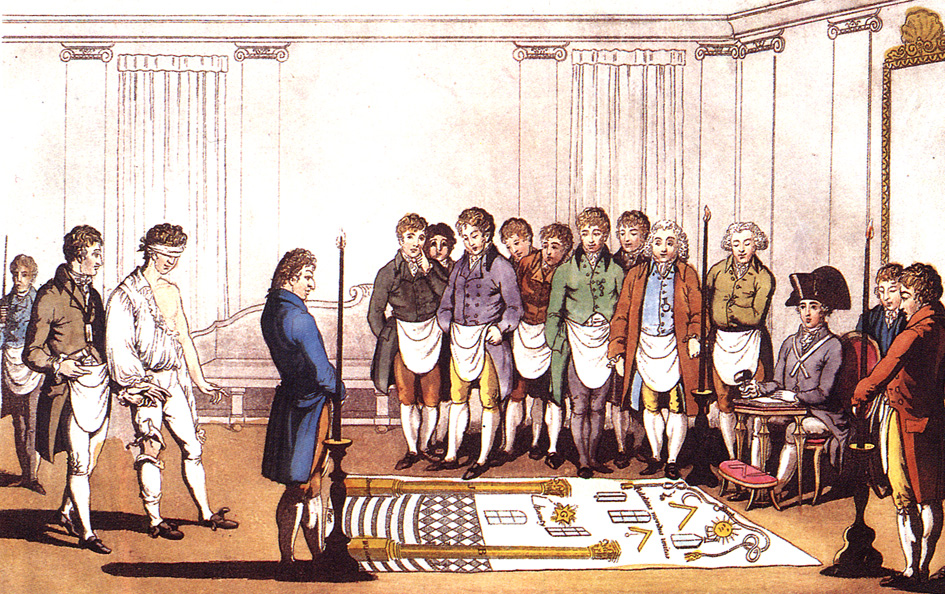

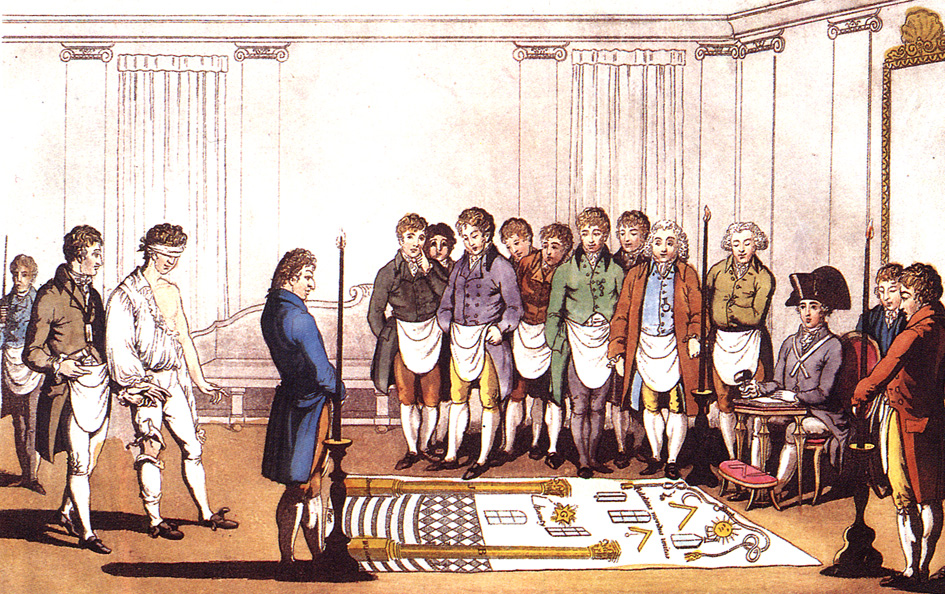

The bulk of Masonic ritual

Masonic ritual is the scripted words and actions that are spoken or performed during the degree work in a Masonic lodge. Masonic symbolism is that which is used to illustrate the principles which Freemasonry espouses. Masonic ritual has appeared ...

consists of degree ceremonies. Candidates for Freemasonry are progressively ''initiated'' into Freemasonry, first in the degree of Entered Apprentice. At some later time, in separate ceremonies, they will be ''passed'' to the degree of Fellowcraft; and then ''raised'' to the degree of Master Mason. In each of these ceremonies, the candidate must first take the new obligations of the degree, and is then entrusted with secret knowledge including passwords, signs and grips (secret handshake

A secret handshake is a distinct form of handshake or greeting which indicates membership in or loyalty to a club, clique or subculture. The typical secret handshake involves placing one's fingers or thumbs in a particular position, one that wil ...

s) confined to his new rank."Words, Grips and Signs"H. L. Haywood, ''Symbolical Masonry'', 1923, Chapter XVIII, ''Sacred Texts'' website, retrieved 9 January 2014 Another ceremony is the annual installation of the Master of the Lodge and his appointed or elected officers. In some jurisdictions an ''Installed Master'' elected, obligated and invested to preside over a Lodge, is valued as a separate rank with its own secrets and distinctive title and attributes; after each full year in the Chair the Master invests his elected successor and becomes a Past Master with privileges in the Lodge and Grand Lodge. In other jurisdictions, the grade is not recognised, and no inner ceremony conveys new secrets during the installation of a new Master of the Lodge. Most Lodges have some sort of social functions, allowing members, their partners and non-Masonic guests to meet openly. Often coupled with these events is the discharge of every Mason's and Lodge's collective obligation to contribute to charity. This occurs at many levels, including in annual dues, subscriptions, fundraising events, Lodges and Grand Lodges. Masons and their charities contribute for the relief of need in many fields, such as education, health and old age. Private Lodges form the backbone of Freemasonry, with the sole right to elect their own candidates for initiation as Masons or admission as joining Masons, and sometimes with exclusive rights over residents local to their premises. There are non-local Lodges where Masons meet for wider or narrower purposes, such or in association with some hobby, sport, Masonic research, business, profession, regiment or college. The rank of Master Mason also entitles a Freemason to explore Masonry further through other degrees, administered separately from the basic Craft or "Blue Lodge" degrees described here, but generally having a similar structure and meetings.Michael Johnstone, ''The Freemasons'', Arcturus, 2005, pp. 101–120 There is much diversity and little consistency in Freemasonry, because each Masonic jurisdiction is independent and sets its own rules and procedures while Grand Lodges have limited jurisdiction over their constituent member Lodges, which are ultimately private clubs. The wording of the ritual, the number of officers present, the layout of the meeting room, etc. varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

''Maconnieke Encyclopedie'', retrieved 31 October 2013 Almost all officers of a Lodge are elected or appointed annually. Every Masonic Lodge has a Master, two Wardens, a treasurer and a secretary. There is also always a

Tyler Tyler may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Tyler (name), an English name; with lists of people with the surname or given name

* Tyler, the Creator (born 1991), American rap artist and producer

* John Tyler, 10th president of the United ...

, or outer guard, outside the door of a working Lodge, who may be paid to secure its privacy. Other offices vary between jurisdictions.

Each Masonic Lodge exists and operates according to ancient principles known as the ''Landmarks of Freemasonry'', which elude any universally accepted definition.

Joining a lodge

Candidates for Freemasonry will usually have met the most active members of the Lodge they are joining before being elected for initiation. The process varies among Grand Lodges, but in modern times interested people often look up a local Lodge through the Internet and will typically be introduced to a Lodge social function or open evening. The onus is upon candidates to ask to join; while they may be encouraged to ask, they may not be invited. Once the initial inquiry is made, a formal application may be proposed and seconded or announced in open Lodge and a more or less formal interview usually follows. If the candidate wishes to proceed, references are taken up during a period of notice so that members may enquire into the candidate's suitability and discuss it. Finally the Lodge takes an officially secret ballot on each application before a candidate is either initiated or rejected."How to become a Freemason"

Candidates for Freemasonry will usually have met the most active members of the Lodge they are joining before being elected for initiation. The process varies among Grand Lodges, but in modern times interested people often look up a local Lodge through the Internet and will typically be introduced to a Lodge social function or open evening. The onus is upon candidates to ask to join; while they may be encouraged to ask, they may not be invited. Once the initial inquiry is made, a formal application may be proposed and seconded or announced in open Lodge and a more or less formal interview usually follows. If the candidate wishes to proceed, references are taken up during a period of notice so that members may enquire into the candidate's suitability and discuss it. Finally the Lodge takes an officially secret ballot on each application before a candidate is either initiated or rejected."How to become a Freemason"''Masonic Lodge of Education'', retrieved 20 November 2013 The exact number of adverse ballots (“blackballs”) required to reject a candidate varies between Masonic jurisdictions. As an example, the

United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

only requires a single “blackball", while the Grand Lodge of New York

The Grand Lodge of New York (officially, the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York) is the largest and oldest independent organization of Freemasons in the U.S. state of New York. It was at one time the largest grand ...

requires three.

A minimum requirement of every body of Freemasons is that each candidate must be "free and of good reputation". The question of freedom, a standard feudal requirement of mediaeval guilds, is nowadays one of independence: the object is that every Mason should be a proper and responsible person. Thus, each Grand Lodge has a standard minimum age, varying greatly and often subject to dispensation in particular cases. (For example, in England the standard minimum age to join is 21, but university lodges are given dispensations to initiate undergraduates below that age.)

Additionally, most Grand Lodges require a candidate to declare a belief in a Supreme Being

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

(although every candidate must interpret this condition in his own way, as all religious discussion is commonly prohibited). In a few cases, the candidate may be required to be of a specific religion. The form of Freemasonry most common in Scandinavia (known as the Swedish Rite

The Swedish Rite is a variation or Rite of Freemasonry that is common in Scandinavian countries and to a limited extent in Germany. It is different from other branches of Freemasonry in that, rather than having the three self-contained foundati ...

), for example, accepts only Christians. At the other end of the spectrum, "Liberal" or Continental Freemasonry

Continental Freemasonry, otherwise known as Liberal Freemasonry, Latin Freemasonry, and Adogmatic Freemasonry, includes the Masonic lodges, primarily on the European continent, that recognize the Grand Orient de France (GOdF) or belong to CLIP ...

, exemplified by the Grand Orient de France

The Grand Orient de France (GODF) is the oldest and largest of several Freemasonry, Freemasonic organizations based in France and is the oldest in Continental Europe (as it was formed out of an older Grand Lodge of France in 1773, and briefly ab ...

, does not require a declaration of belief in any deity and accepts atheists (the cause of the distinction from the rest of Freemasonry)."Faut-il croire en Dieu?"Foire aux Questions, ''Grand Orient de France'', Retrieved 23 November 2013

''Pietre-Stones'', retrieved 23 November 2013 During the ceremony of initiation, the candidate is required to undertake an obligation, swearing on the religious volume sacred to his personal faith to do good as a Mason. In the course of three degrees, Masons will promise to keep the secrets of their degree from lower degrees and outsiders, as far as practicality and the law permit, and to support a fellow Mason in distress. There is formal instruction as to the duties of a Freemason, but on the whole, Freemasons are left to explore the craft in the manner they find most satisfying. Some will simply enjoy the dramatics, or the management and administration of the lodge, others will explore the history, ritual and symbolism of the craft, others will focus their involvement on their Lodge's sociopolitical side, perhaps in association with other lodges, while still others will concentrate on the lodge's charitable functions.

Organisation

Grand Lodges

Grand Lodge

A Grand Lodge (or Grand Orient or other similar title) is the overarching governing body of a fraternal or other similarly organized group in a given area, usually a city, state, or country.

In Freemasonry

A Grand Lodge or Grand Orient is the us ...

s (or sometimes Grand Orients), each of which governs its own Masonic jurisdiction, which consists of subordinate (or ''constituent'') Lodges. The largest single jurisdiction, in terms of membership, is the United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

(with local organisation into Provincial Grand Lodges possessing a combined membership estimated at around a quarter million). The Grand Lodge of Scotland

The Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland is the governing body of Freemasonry in Scotland. It was founded in 1736. About one third of Scotland's lodges were represented at the foundation meeting of the Grand Lodge.

Histor ...

and Grand Lodge of Ireland

The Grand Lodge of Ireland is the second most senior Grand Lodge of Freemasons in the world, and the oldest in continuous existence. Since no specific record of its foundation exists, 1725 is the year celebrated in Grand Lodge anniversaries, as ...

(taken together) have approximately 150,000 members. In the United States, there are 51 Grand Lodges (one in each state and the District of Columbia) which together have a total membership just under 2 million.

Recognition, amity and regularity

Relations between Grand Lodges are determined by the concept of ''Recognition''. Each Grand Lodge maintains a list of other Grand Lodges that it recognises. When two Grand Lodges recognise and are in Masonic communication with each other, they are said to be '' in amity'', and the brethren of each may visit each other's Lodges and interact Masonically. When two Grand Lodges are not in amity, inter-visitation is not allowed. There are many reasons one Grand Lodge will withhold or withdraw recognition from another, but the two most common are ''Exclusive Jurisdiction'' and ''Regularity''.Exclusive Jurisdiction

Exclusive Jurisdiction is a concept whereby normally only one Grand Lodge will be recognised in any geographical area. If two Grand Lodges claim jurisdiction over the same area, the other Grand Lodges will have to choose between them, and they may not all decide to recognise the same one. (In 1849, for example, the Grand Lodge of New York split into two rival factions, each claiming to be the legitimate Grand Lodge. Other Grand Lodges had to choose between them until the schism was healed). Exclusive Jurisdiction can be waived when the two overlapping Grand Lodges are themselves in Amity and agree to share jurisdiction. For example, since the Grand Lodge of Connecticut is in Amity with the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Connecticut, the principle of Exclusive Jurisdiction does not apply, and other Grand Lodges may recognise both, likewise the five distinct kinds of lodges in Germany have nominally united under one Grand Lodge, in order to obtain international recognition.Regularity

Regularity is a concept based on adherence to

Regularity is a concept based on adherence to Masonic Landmarks

Masonic landmarks are a set of principles that many Freemasons claim to be ancient and unchangeable precepts of Masonry. Issues of the "regularity" of a Freemasonic Lodge, Grand Lodge or Grand Orient are judged in the context of the landmarks. ...

, the basic membership requirements, tenets and rituals of the craft. Each Grand Lodge sets its own definition of what these landmarks are, and thus what is Regular and what is Irregular (and the definitions do not necessarily agree between Grand Lodges). Essentially, every Grand Lodge will hold that ''its'' landmarks (its requirements, tenets and rituals) are Regular, and judge other Grand Lodges based on those. If the differences are significant, one Grand Lodge may declare the other "Irregular" and withdraw or withhold recognition.

The most commonly shared rules for Recognition (based on Regularity) are those given by the United Grand Lodge of England in 1929:

* The Grand Lodge should be established by an existing regular Grand Lodge, or by at least three regular Lodges.

* A belief in a supreme being and scripture is a condition of membership.

* Initiates should take their vows on that scripture.

* Only men can be admitted, and no relationship exists with mixed Lodges.

* The Grand Lodge has complete control over the first three degrees, and is not subject to another body.

* All Lodges shall display a volume of scripture with the square and compasses while in session.

* There is no discussion of politics or religion.

* "Ancient landmarks, customs and usages" observed.''UGLE Book of Constitutions'', "Basic Principles for Grand Lodge Recognition", any year since 1930, page numbers may vary.

Other degrees, orders, and bodies

Blue Lodges, known as Craft Lodges in the United Kingdom, offer only the three traditional degrees. In most jurisdictions, the rank of past or installed master is also conferred in Blue/Craft Lodges. Master Masons are able to extend their Masonic experience by taking further degrees, in appendant or other bodies whether or not approved by their own Grand Lodge. The Ancient and AcceptedScottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the Sco ...

is a system of 33 degrees, including the three Blue Lodge degrees administered by a local or national Supreme Council. This system is popular in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

and in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

. In America, the York Rite

The York Rite, sometimes referred to as the American Rite, is one of several Rites of Freemasonry. It is named for, but not practiced in York, Yorkshire, England. A Rite is a series of progressive degrees that are conferred by various Masonic ...

, with a similar range, administers three orders of Masonry, namely the Royal Arch, Cryptic Masonry

Cryptic Masonry is the second part of the York Rite system of Masonic degrees, and the last found within the Rite that deals specifically with the Hiramic Legend. These degrees are the gateway to Temple restoration rituals or the Second Temple ...

, and Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

.

In Britain, separate bodies administer each order. Freemasons are encouraged to join the Holy Royal Arch

The Royal Arch is a degree of Freemasonry. The Royal Arch is present in all main masonic systems, though in some it is worked as part of Craft ('mainstream') Freemasonry, and in others in an appendant ('additional') order. Royal Arch Masons meet ...

, which is linked to Mark Masonry in Scotland and Ireland, but completely separate in England. In England, the Royal Arch is closely associated with the Craft, automatically having many Grand Officers in common, including H.R.H the Duke of Kent

Duke of Kent is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of peerage of Great Britain, Great Britain and the peerage of the United Kingdom, United Kingdom, most recently as a Royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom, royal dukedom ...

as both Grand Master of the Craft and First Grand Principal of the Royal Arch. The English Knights Templar and Cryptic Masonry share the Mark Grand Lodge offices and staff at Mark Masons Hall. The Ancient and Accepted Rite (similar to the Scottish Rite), requires a member to proclaim the Trinitarian Christian faith, and is administered from Duke Street in London.

In the Nordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; literal translation, lit. 'the North') are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe and the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It includes the sovereign states of Denmar ...

, the Swedish Rite

The Swedish Rite is a variation or Rite of Freemasonry that is common in Scandinavian countries and to a limited extent in Germany. It is different from other branches of Freemasonry in that, rather than having the three self-contained foundati ...

is dominant; a variation of it is also used in parts of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

.

Ritual and symbolism

Freemasonry describes itself as a "beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". The symbolism is mainly, but not exclusively, drawn from the tools of stonemasons – the square and compasses, the level and plumb rule, the

Freemasonry describes itself as a "beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". The symbolism is mainly, but not exclusively, drawn from the tools of stonemasons – the square and compasses, the level and plumb rule, the trowel

A trowel is a small hand tool used for digging, applying, smoothing, or moving small amounts of viscous or particulate material. Common varieties include the masonry trowel, garden trowel, and float trowel.

A power trowel is a much larger gas ...

, the rough and smooth ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

s, among others. Moral lessons are attributed to each of these tools, although the assignment is by no means consistent. The meaning of the symbolism is taught and explored through ritual, and in lectures and articles by individual Masons who offer their personal insights and opinions.

According to the scholar of Western esotericism Jan A. M. Snoek: "the best way to characterize Freemasonry is in terms of what it is not, rather than what it is". All Freemasons begin their journey in the "craft" by being progressively "initiated", "passed" and "raised" into the three degrees of Craft, or Blue Lodge Masonry. During these three rituals, the candidate is progressively taught the Masonic symbols, and entrusted with grips or tokens, signs, and words to signify to other Masons which degrees he has taken. The dramatic allegorical ceremonies include explanatory lectures, and revolve around the construction of the Temple of Solomon

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by the ...

, and the artistry and death of the chief architect, Hiram Abiff

Hiram Abiff (also Hiram Abif or the Widow's son) is the central character of an allegory presented to all candidates during the third degree in Freemasonry.

Hiram is presented as the chief architect of King Solomon's Temple. He is murdered ins ...

. The degrees are those of "Entered apprentice", "Fellowcraft" and "Master Mason". While many different versions of these rituals exist, with various lodge layouts and versions of the Hiramic legend, each version is recognizable to any Freemason from any jurisdiction.

In some jurisdictions, the main themes of each degree are illustrated by tracing board

Tracing boards are painted or printed illustrations depicting the various emblems and symbols of Freemasonry. They can be used as teaching aids during the lectures that follow each of the Masonic Degrees, when an experienced member explains the ...

s. These painted depictions of Masonic themes are exhibited in the lodge according to which degree is being worked, and are explained to the candidate to illustrate the legend and symbolism of each degree.

The idea of Masonic brotherhood probably descends from a 16th-century legal definition of a "brother" as one who has taken an oath of mutual support to another. Accordingly, Masons swear at each degree to keep the contents of that degree secret, and to support and protect their brethren unless they have broken the law. In most Lodges, the oath or obligation is taken on a '' Volume of Sacred Law'', whichever book of divine revelation is appropriate to the religious beliefs of the individual brother (usually the Bible in the Anglo-American tradition). In ''Progressive'' continental Freemasonry, books other than scripture are permissible, a cause of rupture between Grand Lodges.

History

Origins

Since the middle of the 19th century, Masonic historians have sought the origins of the movement in a series of similar documents known as the

Since the middle of the 19th century, Masonic historians have sought the origins of the movement in a series of similar documents known as the Old Charges

There are a number of masonic manuscripts that are important in the study of the emergence of Freemasonry. Most numerous are the ''Old Charges'' or ''Constitutions''. These documents outlined a "history" of masonry, tracing its origins to a biblic ...

, dating from the Regius Poem in about 1425 to the beginning of the 18th century. Alluding to the membership of a lodge of operative masons, they relate it to a mythologised history of the craft, the duties of its grades, and the manner in which oaths of fidelity are to be taken on joining. The 15th century also sees the first evidence of ceremonial regalia.

There is no clear mechanism by which these local trade organisations became today's Masonic Lodges. The earliest rituals and passwords known, from operative lodges around the turn of the 17th–18th centuries, show continuity with the rituals developed in the later 18th century by accepted or speculative Masons, as those members who did not practice the physical craft gradually came to be known. The minutes of the Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary's Chapel) No. 1

The Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary's Chapel), No.1, is a Masonic Lodge in Edinburgh, Scotland.

It is designated number 1 on the Roll (list) of lodges of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, and as it possesses the oldest existing minute of any masonic lodge ...

in Scotland show a continuity from an operative lodge in 1598 to a modern speculative Lodge. It is reputed to be the oldest Masonic Lodge in the world.

Alternatively,

Alternatively, Thomas De Quincey

Thomas Penson De Quincey (; 15 August 17858 December 1859) was an English writer, essayist, and literary critic, best known for his ''Confessions of an English Opium-Eater'' (1821). Many scholars suggest that in publishing this work De Quince ...

in his work titled ''Rosicrucians and Freemasonry'' put forward the theory that suggested that Freemasonry may have been an outgrowth of Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts purported to announce the existence of a hitherto unknown esoteric order to the world and made seeking its ...

. The theory had also been postulated in 1803 by German professor; J. G. Buhle.

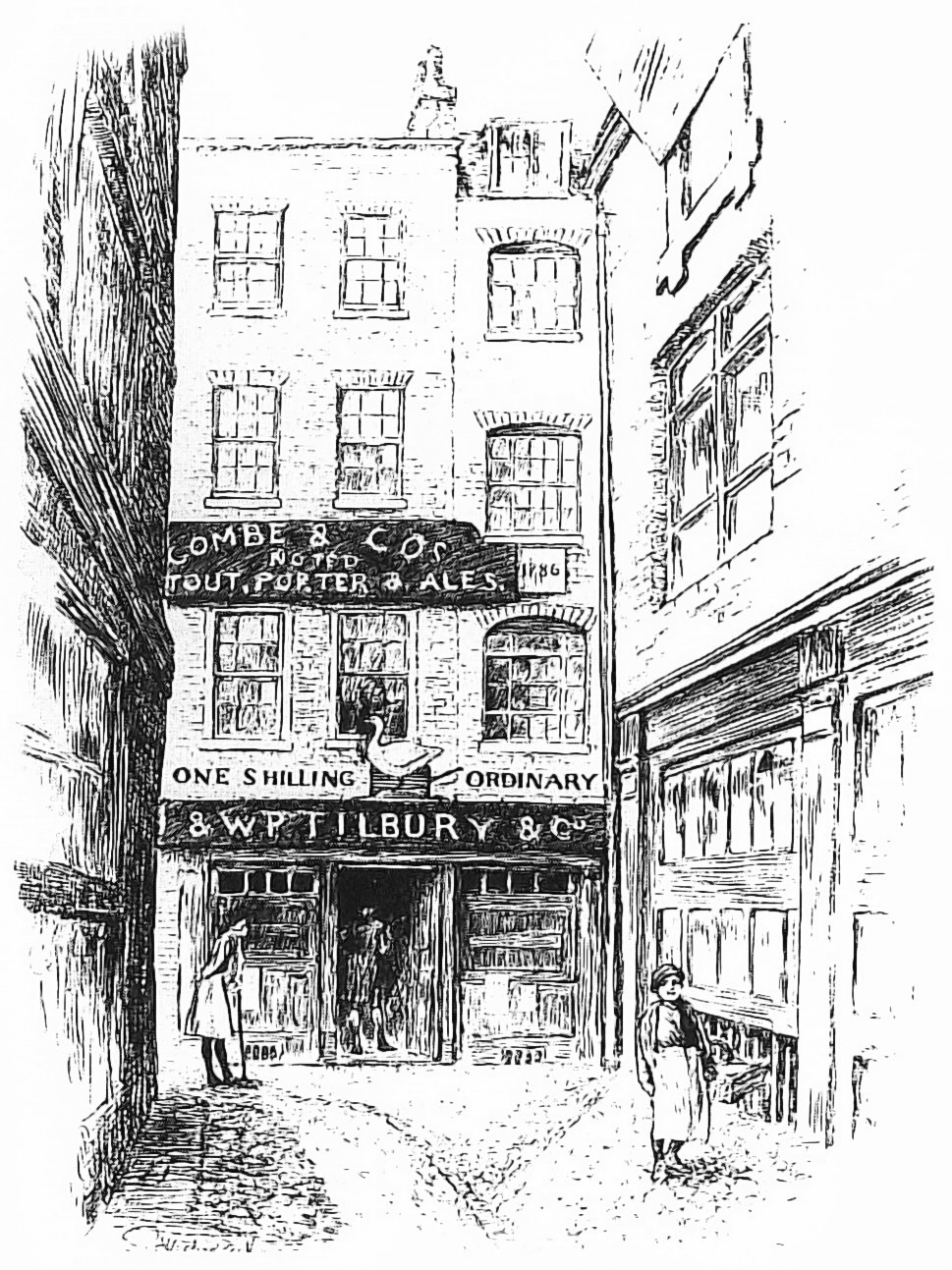

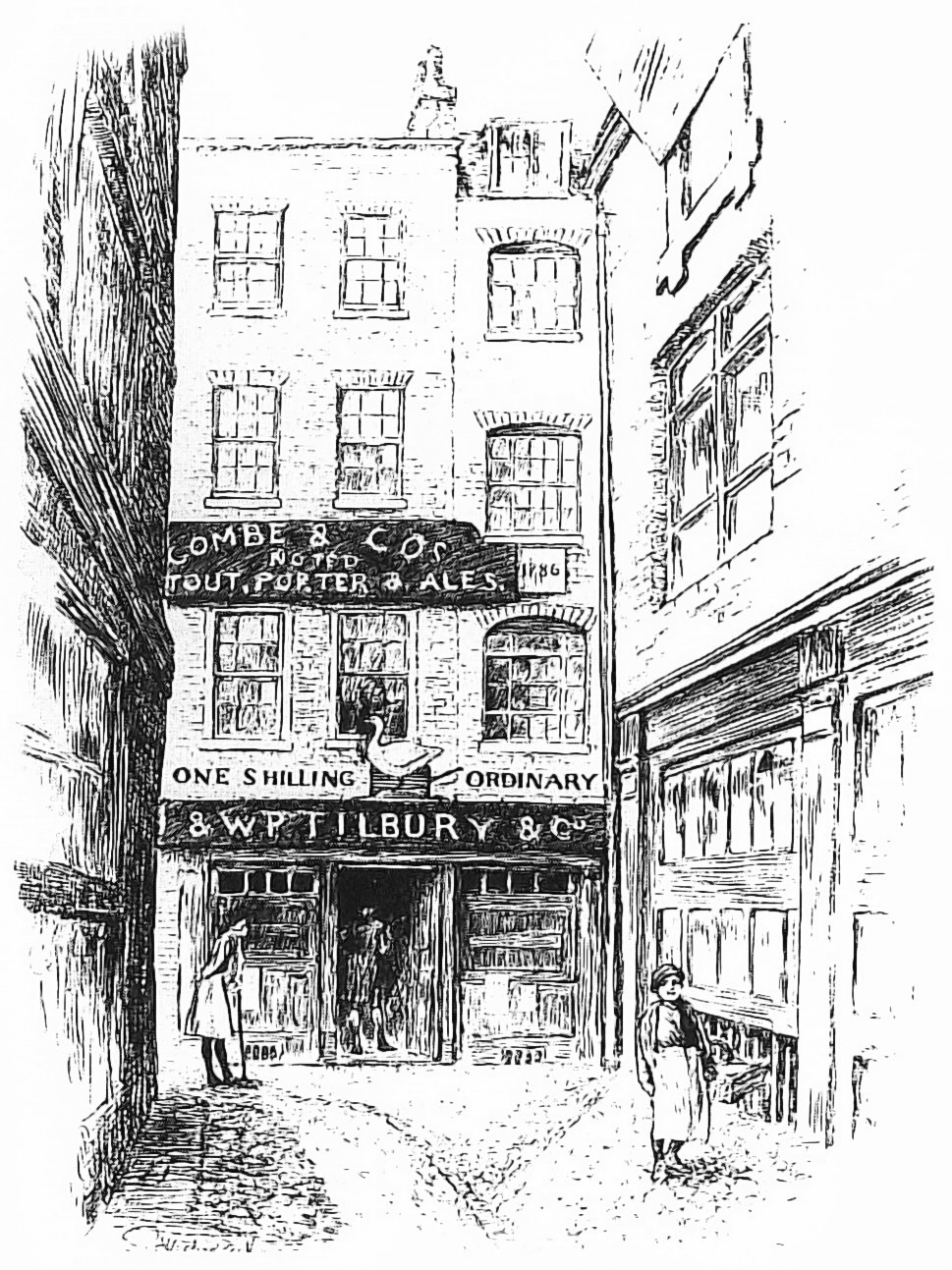

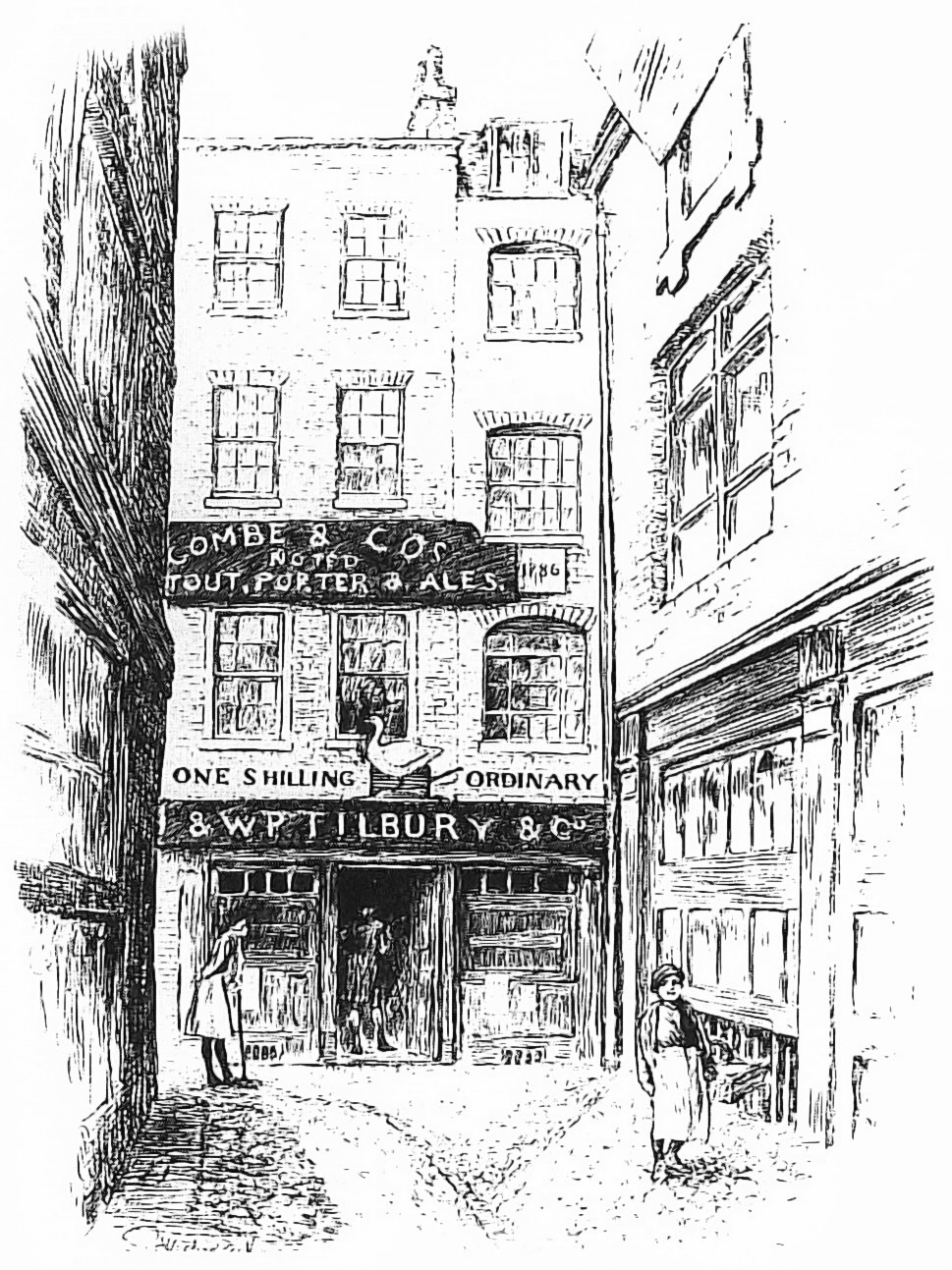

The first Grand Lodge, the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster, later called the Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

, was founded on St John's Day, 24 June 1717, when four existing London Lodges met for a joint dinner. Over the next decade, most of the existing Lodges in England joined the new regulatory body, which itself entered a period of self-publicity and expansion. New lodges were created and the fraternity began to grow.

During the course of the 18th century, as aristocrats and artists crowded out the craftsmen originally associated with the organization, Freemasonry became fashionable throughout Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and the American colonies.

Between 1730 and 1750, the Grand Lodge endorsed several significant changes that some Lodges could not endorse. A rival Grand Lodge was formed on 17 July 1751, which called itself the "Antient Grand Lodge of England

The Ancient Grand Lodge of England, as it is known today, or ''The Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honourable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (according to the Old Constitutions granted by His Royal Highness Prince Edwin, at York, Anno ...

” to signify that these lodges were maintaining older traditions, and rejected changes that “modern” Lodges had adopted (historians still use these terms - “Ancients” and “Moderns” - to differentiate the two bodies). These two Grand Lodges vied for supremacy until the Moderns promised to return to the ancient ritual. They united on 27 December 1813 to form the United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

.I. R. Clarke, "The Formation of the Grand Lodge of the Antients"Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, vol 79 (1966), p. 270-73, ''Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon'', retrieved 28 June 2012 The

Grand Lodge of Ireland

The Grand Lodge of Ireland is the second most senior Grand Lodge of Freemasons in the world, and the oldest in continuous existence. Since no specific record of its foundation exists, 1725 is the year celebrated in Grand Lodge anniversaries, as ...

and the Grand Lodge of Scotland

The Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland is the governing body of Freemasonry in Scotland. It was founded in 1736. About one third of Scotland's lodges were represented at the foundation meeting of the Grand Lodge.

Histor ...

were formed in 1725 and 1736, respectively, although neither persuaded all of the existing lodges in their countries to join for many years.

North America

The earliest known American lodges were inPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. The Collector for the port of Pennsylvania, John Moore, wrote of attending lodges there in 1715, two years before the putative formation of the first Grand Lodge in London. The Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

appointed a Provincial Grand Master for North America in 1731, based in Pennsylvania, leading to the creation of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania

The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, officially The Right Worshipful Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania and Masonic Jurisdictions Thereunto Belonging, is the premier masonic organizati ...

.

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Erasmus James Philipps

Erasmus James Philipps (23 April 1705 – 26 September 1760) was the second longest serving member on Nova Scotia Council (1730-1760) and the nephew of Nova Scotia Governor Richard Philipps. He was also a captain in the 40th Regiment of Foot. ...

became a Freemason while working on a commission to resolve boundaries in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

and, in 1739, he became provincial Grand Master for Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

; Philipps founded the first Masonic lodge in Canada at Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the n ...

.

Other lodges in the colony of Pennsylvania obtained authorisations from the later Antient Grand Lodge of England

The Ancient Grand Lodge of England, as it is known today, or ''The Grand Lodge of the Most Ancient and Honourable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (according to the Old Constitutions granted by His Royal Highness Prince Edwin, at York, Anno ...

, the Grand Lodge of Scotland

The Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland is the governing body of Freemasonry in Scotland. It was founded in 1736. About one third of Scotland's lodges were represented at the foundation meeting of the Grand Lodge.

Histor ...

, and the Grand Lodge of Ireland

The Grand Lodge of Ireland is the second most senior Grand Lodge of Freemasons in the world, and the oldest in continuous existence. Since no specific record of its foundation exists, 1725 is the year celebrated in Grand Lodge anniversaries, as ...

, which was particularly well represented in the travelling lodges of the British Army. Many lodges came into existence with no warrant from any Grand Lodge, applying and paying for their authorisation only after they were confident of their own survival.

After the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, independent U.S. Grand Lodges developed within each state. Some thought was briefly given to organising an overarching "Grand Lodge of the United States," with George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, who was a member of a Virginian lodge, as the first Grand Master, but the idea was short-lived. The various state Grand Lodges did not wish to diminish their own authority by agreeing to such a body.

Jamaican Freemasonry

Freemasonry was imported toJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

by British immigrants who colonized the island for over 300 years. In 1908, there were eleven recorded Masonic Lodges, which included three Grand Lodges, two Craft Lodges, and two Rose Croix Chapters. During slavery, the Lodges were open to all "freeborn" men. According to the Jamaican 1834 census, that potentially included 5,000 free black men and 40,000 free people of colour (mixed race). After the full abolition of slavery in 1838, the Lodges were open to all Jamaican men of any race. Jamaica also kept close relationships with Masons from other countries. Jamaican Freemasonry historian Jackie Ranston, noted that:

On 25 May 2017, Masons around the world celebrated the 300th anniversary of the fraternity. Jamaica hosted one of the regional gatherings for this celebration.

Prince Hall Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry exists because of the refusal of early American lodges to admitAfrican American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s. In 1775, an African American named Prince Hall

Prince Hall (1807) was an American abolitionist and leader in the free black community in Boston. He founded Prince Hall Freemasonry and lobbied for education rights for African American children. He was also active in the back-to-Africa movem ...

, along with 14 other African-American men, was initiated into a British military lodge with a warrant from the Grand Lodge of Ireland

The Grand Lodge of Ireland is the second most senior Grand Lodge of Freemasons in the world, and the oldest in continuous existence. Since no specific record of its foundation exists, 1725 is the year celebrated in Grand Lodge anniversaries, as ...

, having failed to obtain admission from the other lodges in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. When the British military Lodge left North America after the end of the Revolution, those 15 men were given the authority to meet as a Lodge, but not to initiate Masons. In 1784, these individuals obtained a Warrant from the Grand Lodge of England (Moderns) and formed African Lodge, Number 459. When the two English grand lodges united in 1813, all U.S.-based Lodges were stricken from their rolls – largely because of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. Thus, separated from both English jurisdiction and any concordantly recognised U.S. Grand Lodge, African Lodge retitled itself as the African Lodge, Number 1 – and became a ''de facto'' Grand Lodge. (This lodge is not to be confused with the various Grand Lodges in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.) As with the rest of U.S. Freemasonry, Prince Hall Freemasonry soon grew and organised on a Grand Lodge system for each state.

Widespread racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in 19th- and early 20th-century North America made it difficult for African Americans to join Lodges outside of Prince Hall jurisdictions – and impossible for inter-jurisdiction recognition between the parallel U.S. Masonic authorities. By the 1980s, such discrimination was a thing of the past. Today most U.S. Grand Lodges recognise their Prince Hall counterparts, and the authorities of both traditions are working towards full recognition. The United Grand Lodge of England has no problem with recognising Prince Hall Grand Lodges. While celebrating their heritage as lodges of African-Americans, Prince Hall is open to all men regardless of race or religion.

Emergence of Continental Freemasonry

English Freemasonry spread to France in the 1720s, first as lodges of expatriates and exiled

English Freemasonry spread to France in the 1720s, first as lodges of expatriates and exiled Jacobites

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometime ...

, and then as distinctively French lodges that still follow the ritual of the Moderns

The organisation now known as the Premier Grand Lodge of England was founded on 24 June 1717 as the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster. Originally concerned with the practice of Freemasonry in London and Westminster, it soon became known as ...

. From France and England, Freemasonry spread to most of Continental Europe during the course of the 18th century. The Grande Loge de France formed under the Grand Mastership of the Duke of Clermont, who exercised only nominal authority. His successor, the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

, reconstituted the central body as the Grand Orient de France in 1773. Briefly eclipsed during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, French Freemasonry continued to grow in the next century, at first under the leadership of Alexandre Francois Auguste de Grasse

Alexandre Francois Auguste de Grasse, known as Auguste de Grasse and Comte de Grasse-Tilly (February 14, 1765 – June 10, 1845), was a French career army officer. He was assigned to the French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1789, where he married ...

, Comte de Grassy-Tilly. A career Army officer, he lived with his family in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

from 1793 to the early 1800s, after leaving Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

, now Haiti, during the years of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

.

Freemasonry in the Middle East

After the failure of the 1830 Italian revolution, a number ofItalian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

Freemasons were forced to flee. They secretly set up an approved chapter of Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the Sco ...

in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, a town already inhabited by a large Italian community. Meanwhile, the French freemasons publicly organised a local chapter in Alexandria in 1845. During the 19th and 20th century Ottoman empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Masonic lodges operated widely across all parts of the empire and numerous Sufi orders

A tariqa (or ''tariqah''; ar, طريقة ') is a school or order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking ''haqiqa'', which translates as "ultimate truth".

...

shared a close relationship with them. Many Young Turks affiliated with the Bektashi order

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

were members and patrons of freemasonry. They were also closely allied against European imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

. Many Ottoman intellectuals believed that Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

and Freemasonry shared close similarities in doctrines, spiritual outlook and mysticism.

Schism

The ritual form on which the Grand Orient of France was based was abolished in England in the events leading to the formation of theUnited Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

in 1813. However the two jurisdictions continued in amity, or mutual recognition, until events of the 1860s and 1870s drove a seemingly permanent wedge between them. In 1868 the ''Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of the State of Louisiana'' appeared in the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of Louisiana, recognised by the Grand Orient de France, but regarded by the older body as an invasion of their jurisdiction. The new Scottish Rite body admitted black people. The resolution of the Grand Orient the following year that neither colour, race, nor religion could disqualify a man from Masonry prompted the Grand Lodge to withdraw recognition, and it persuaded other American Grand Lodges to do the same.

A dispute during the Lausanne Congress of Supreme Councils of 1875

The Lausanne Congress of 1875 was a historic effort of eleven Supreme Councils to review and reform the Grand Constitutions of The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry

of 1786. The Congress took place from 6–22 September 1875 with ...

prompted the Grand Orient de France to commission a report by a Protestant pastor, which concluded that, as Freemasonry was not a religion, it should not require a religious belief. The new constitutions read, "Its principles are absolute liberty of conscience and human solidarity", the existence of God and the immortality of the soul being struck out. It is possible that the immediate objections of the United Grand Lodge of England were at least partly motivated by the political tension between France and Britain at the time. The result was the withdrawal of recognition of the Grand Orient of France by the United Grand Lodge of England, a situation that continues today.

Not all French lodges agreed with the new wording. In 1894, lodges favouring the compulsory recognition of the Great Architect of the Universe formed the Grande Loge de France

Grande Loge de France (G∴L∴D∴F∴) is a Masonic obedience based in France. Its conception of Freemasonry is spiritual, traditional and initiatory. Its ritual is centred on the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. It sees itself as occupying a ...

. In 1913, the United Grand Lodge of England recognised a new Grand Lodge of Regular Freemasons, a Grand Lodge that follows a similar rite to Anglo-American Freemasonry with a mandatory belief in a deity.

There are now three strands of Freemasonry in France, which extend into the rest of Continental Europe:-

* Liberal, also called adogmatic or progressive – Principles of liberty of conscience, and laicity, particularly the separation of the Church and State.

* Traditional – Old French ritual with a requirement for a belief in a Supreme Being. (This strand is typified by the Grande Loge de France

Grande Loge de France (G∴L∴D∴F∴) is a Masonic obedience based in France. Its conception of Freemasonry is spiritual, traditional and initiatory. Its ritual is centred on the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. It sees itself as occupying a ...

).

* Regular – Standard Anglo-American ritual, mandatory belief in Supreme Being.

The term Continental Freemasonry

Continental Freemasonry, otherwise known as Liberal Freemasonry, Latin Freemasonry, and Adogmatic Freemasonry, includes the Masonic lodges, primarily on the European continent, that recognize the Grand Orient de France (GOdF) or belong to CLIP ...

was used in Mackey's 1873 ''Encyclopedia of Freemasonry'' to "designate the Lodges on the Continent of Europe which retain many usages which have either been abandoned by, or never were observed in, the Lodges of England, Ireland, and Scotland, as well as the United States of America". Today, it is frequently used to refer to only the Liberal jurisdictions typified by the Grand Orient de France.

The majority of Freemasonry considers the Liberal (Continental) strand to be Irregular, and thus withhold recognition. The Continental lodges, however, did not want to sever masonic ties. In 1961, an umbrella organisation, Centre de Liaison et d'Information des Puissances maçonniques Signataires de l'Appel de Strasbourg

The Centre of Liaison and Information of Masonic Powers Signatories of Strasbourg Appeal ( French: ''Centre de Liaison et d'Information des Puissances maçonniques Signataires de l'Appel de Strasbourg'') or CLIPSAS is an international group of Maso ...

(CLIPSAS) was set up, which today provides a forum for most of these Grand Lodges and Grand Orients worldwide. Included in the list of over 70 Grand Lodges and Grand Orients are representatives of all three of the above categories, including mixed and women's organisations. The United Grand Lodge of England does not communicate with any of these jurisdictions, and expects its allies to follow suit. This creates the distinction between Anglo-American and Continental Freemasonry.

Freemasonry and women

The status of women in the old guilds and corporations of medieval masons remains uncertain. The principle of "femme sole" allowed a widow to continue the trade of her husband, but its application had wide local variations, such as full membership of a trade body or limited trade by deputation or approved members of that body. In masonry, the small available evidence points to the less empowered end of the scale. At the dawn of the Grand Lodge era, during the 1720s,James Anderson James Anderson may refer to:

Arts

*James Anderson (American actor) (1921–1969), American actor

*James Anderson (author) (1936–2007), British mystery writer

*James Anderson (English actor) (born 1980), British actor

* James Anderson (filmmaker) ...

composed the first printed constitutions for Freemasons, the basis for most subsequent constitutions, which specifically excluded women from Freemasonry.

As Freemasonry spread, women began to be added to the Lodges of Adoption by their husbands who were continental masons, which worked three degrees with the same names as the men's but different content. The French officially abandoned the experiment in the early 19th century.Barbara L. Thames, "A History of Women's Masonry"''Phoenix Masonry'', retrieved 5 March 2013 Later organisations with a similar aim emerged in the United States, but distinguished the names of the degrees from those of male masonry.

Maria Deraismes

Maria Deraismes (17 August 1828 – 6 February 1894) was a French author, Freemason, and major pioneering force for women's rights.

Biography

Born in Paris, France, Paris, Maria Deraismes grew up in Pontoise in the city's northwest outsk ...

was initiated into Freemasonry in 1882, then resigned to allow her lodge to rejoin their Grand Lodge. Having failed to achieve acceptance from any masonic governing body, she and Georges Martin started a mixed masonic lodge that worked masonic ritual. Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

spread the phenomenon to the English-speaking world. Disagreements over ritual led to the formation of exclusively female bodies of Freemasons in England, which spread to other countries. Meanwhile, the French had re-invented Adoption as an all-female lodge in 1901, only to cast it aside again in 1935. The lodges, however, continued to meet, which gave rise, in 1959, to a body of women practising continental Freemasonry.

In general, Continental Freemasonry is sympathetic to Freemasonry amongst women, dating from the 1890s when French lodges assisted the emergent co-masonic movement by promoting enough of their members to the 33rd degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the Sco ...