Marshall Holloway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marshall Glecker Holloway (November 23, 1912 – June 18, 1991) was an American physicist who worked at the

In 1942, Holloway arrived at

In 1942, Holloway arrived at

Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

during and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. He was its representative, and the deputy scientific director, at the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Second ...

in the Pacific in July 1946. Holloway became the head of the Laboratory's W Division, responsible for new weapons development. In September 1952 he was charged with designing, building and testing a thermonuclear weapon, popularly known as a hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

. This culminated in the Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab in ...

test in November of that year.

Early life

Marshall Glecker Holloway was born inOklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, on November 23, 1912, but his family moved to Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

when he was young. He graduated from Haines City High School

Haines City Senior High School (HCHS) is a public high school in Haines City, Florida. The school has existed in three separate locations.

Overview

Haines City Senior High School belongs to the Polk County School Board and is a member of Polk Di ...

, and entered the University of Florida

The University of Florida (Florida or UF) is a public land-grant research university in Gainesville, Florida. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida, traces its origins to 1853, and has operated continuously on its ...

, which awarded him a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

in Education in 1933, and a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

degree in physics in 1935. He went on to Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

, where he wrote his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common Academic degree, degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields ...

thesis on the ''Range and Specific Ionization of Alpha Particles''.

Holloway married Wilma Schamel, who worked in the Medical Office at Cornell as a medical technologist, on August 22, 1938. During a picnic at Taughannock Falls

Taughannock Falls State Park () is a state park located in the town of Ulysses in Tompkins County, New York in the United States. The park is northwest of Ithaca near Trumansburg.

The park's namesake, Taughannock Falls, is a plunge waterfall ...

on June 3, 1940, she and a graduate student, Henry S. Birnbaum, drowned while trying to rescue two women in the water. The women were subsequently rescued by Jean Doe Bacher, the wife of physicist Robert Bacher, and Helen Hecht, a graduate student, but the bodies of Wilma and Birnbaum had to be retrieved with grappling hooks two days later.

World War II

In 1942, Holloway arrived at

In 1942, Holloway arrived at Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

on a secret assignment from the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. His task was to modify the cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Janu ...

there to help the group there, which included L.D. P. King and Raemer Schreiber

Raemer Edgar Schreiber (November 11, 1910 – December 24, 1998) was an American physicist from McMinnville, Oregon who served Los Alamos National Laboratory during World War II, participating in the development of the atomic bomb. He saw the fi ...

and some graduate students, measure the cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture & engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**Abs ...

of the fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

of a deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

nucleus, when bombarded with a tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus o ...

nucleus to form a nucleus (alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay, but may also be produce ...

), and the cross section of a deuterium-tritium interaction to form . These calculations were for evaluating the feasibility of Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care fo ...

's thermonuclear

Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or “fusing” using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible. There are two forms of thermonuclear fusion: ''uncontrolled'', in which the re ...

" Super bomb", and the resulting reports would remain classified for many years.

The fusion cross section calculations were finished by September 1943, and the Purdue group moved to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

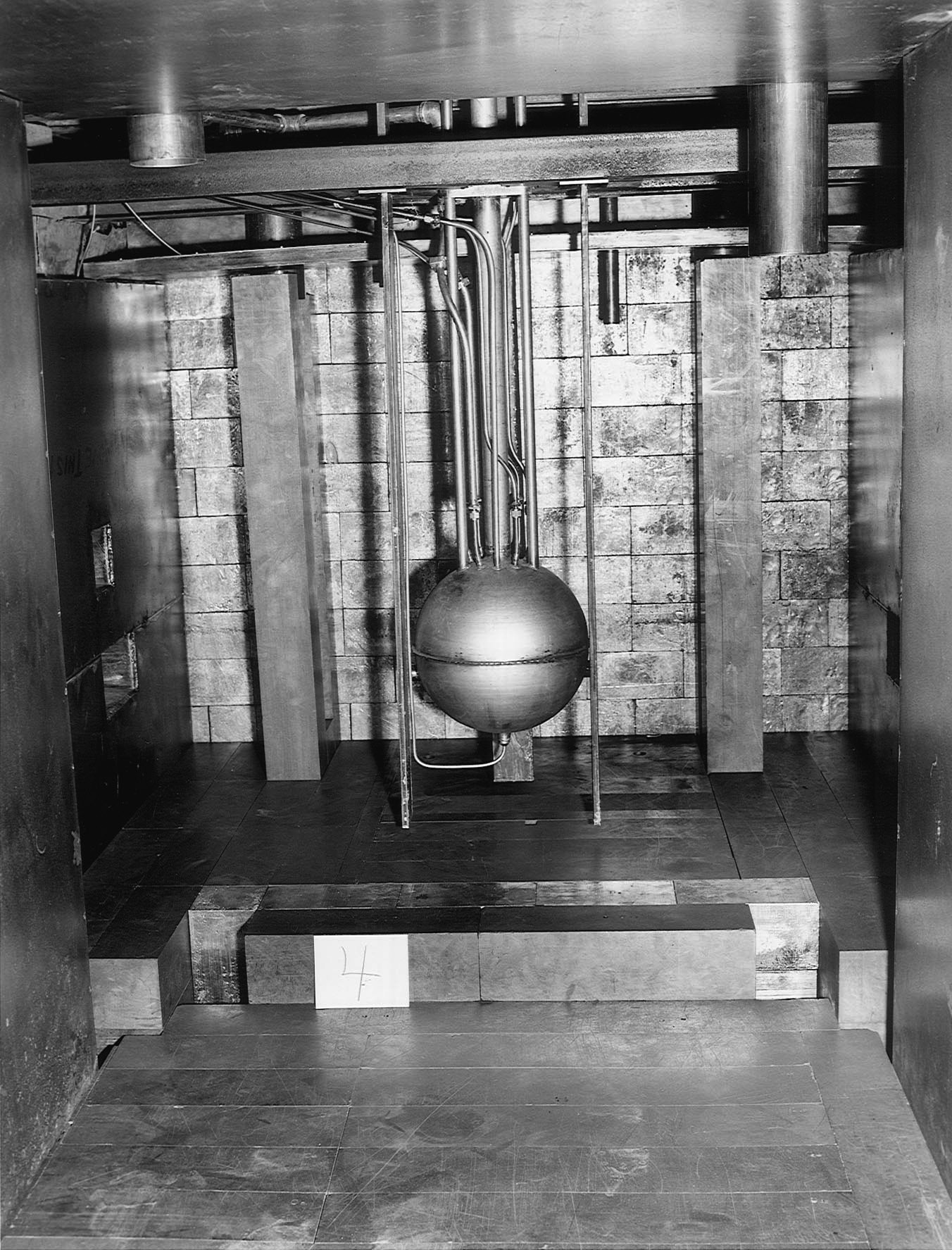

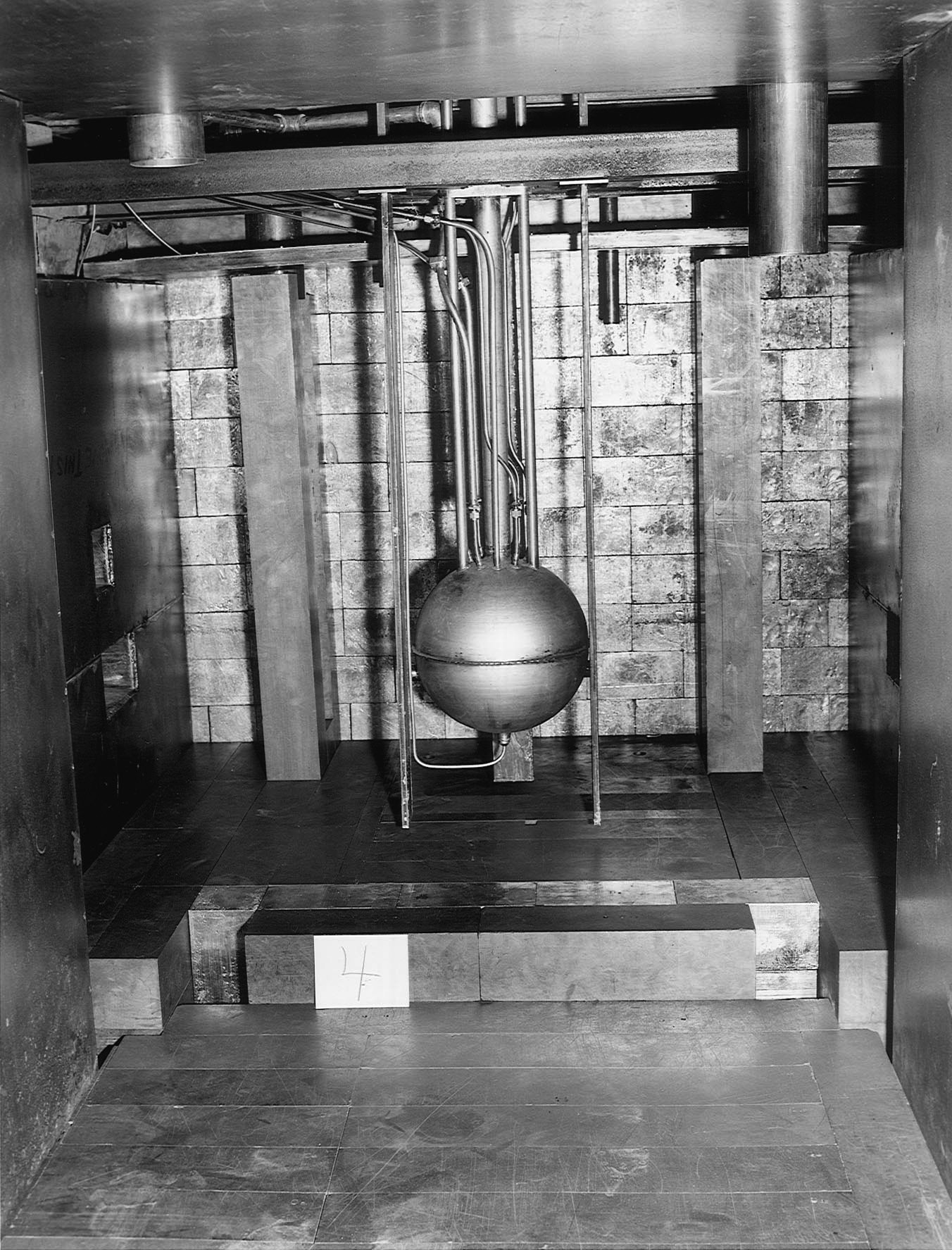

, where most of them, including Holloway, worked on the Water Boiler, an aqueous homogeneous reactor

Aqueous homogeneous reactors (AHR) are a type of nuclear reactor in which soluble nuclear salts (usually uranium sulfate or uranium nitrate) are dissolved in water. The fuel is mixed with the coolant and the moderator, thus the name "homogeneo ...

that was intended for use as a laboratory instrument to test critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fissi ...

calculations and the effect of various tamper materials. The Water Boiler group was headed by Donald W. Kerst from the University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the University ...

, and the group designed and built the Water Boiler, which achieved its criticality in May 1944 under the control of Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

, after one final addition of uranium enriched to 14% uranium 235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists ...

. It was the world's third reactor but the first reactor to use enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

as a fuel, using most of the world's supply at the time, and the first to use liquid nuclear fuel

Nuclear fuel is material used in nuclear power stations to produce heat to power turbines. Heat is created when nuclear fuel undergoes nuclear fission.

Most nuclear fuels contain heavy fissile actinide elements that are capable of undergoing ...

in the form of soluble uranium sulfate dissolved in water.

Holloway studied the safety of the Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

bomb, particularly what would happen if the active material became immersed in water. He was also involved in experiments to measure the critical mass of plutonium. These proved hazardous, taking the lives of Harry Daghlian

Haroutune Krikor Daghlian Jr. (May 4, 1921 – September 15, 1945) was an American physicist with the Manhattan Project, which designed and produced the atomic bombs that were used in World War II. He accidentally irradiated himself on August 2 ...

and Louis Slotin

Louis Alexander Slotin (1 December 1910 – 30 May 1946) was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project. Born and raised in the North End of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Slotin earned both his Bachelor of Science and M ...

after the war. Holloway was part of Robert Bacher's "pit team" that assembled the Gadget for the Trinity nuclear test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

, and he helped Bacher fabricate the plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

hemispheres of the Nagasaki Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bomb.

Later life

Holloway remained at Los Alamos after the war ended in 1945. He was its representative, and the deputy scientific director, at theOperation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Second ...

in the Pacific in July 1946, when atomic bombs were tested against an array of warships. Holloway became the head of the Laboratory's W Division, responsible for new weapons development.

The Los Alamos National Laboratory had continued research into fusion weapons for many years after Holloway's work in 1942 and 1943, and in 1951 the Atomic Energy Commission, which had replaced the Manhattan Project in 1947, ordered the Laboratory to proceed with designing, building and testing a thermonuclear weapon, popularly known as a hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

. Laboratory director Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbury ...

placed Holloway in charge of the hydrogen bomb program.

Although Holloway had a well-earned reputation for his administrative ability, Bradbury's decision to put him in charge was not popular, especially with Edward Teller. The two men had clashed a number of times over a number of different issues. Holloway's appointment was therefore "like waving a red flag in front of a bull". Teller wrote that:

Teller left the project on September 17, 1952, just a week after the announcement of Holloway's appointment. Nor was Teller the only one who chafed under Holloway's leadership style. Before the Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab in ...

test, Wallace Leland and Harold Agnew

Harold Melvin Agnew (March 28, 1921 – September 29, 2013) was an American physicist, best known for having flown as a scientific observer on the Hiroshima bombing mission and, later, as the third director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory ...

put a shark in Holloway's bed. "He never said anything," Agnew recalled, "but after that he was much more collegial."

The Ivy Mike test on November 1, 1952 was a complete success, but it was not a weapon so much as an experiment to verify the Teller and Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

's design. Years of work was still required to produce a usable weapon.

In 1955, Holloway left the Los Alamos National Laboratory for the MIT Lincoln Laboratory

The MIT Lincoln Laboratory, located in Lexington, Massachusetts, is a United States Department of Defense federally funded research and development center chartered to apply advanced technology to problems of national security. Research and dev ...

, where he worked on air defense projects. In 1957 he became head of the Nuclear Products- ERCO Division of ACF Industries

ACF Industries, originally the American Car and Foundry Company (abbreviated as ACF), is an American manufacturer of railroad rolling stock. One of its subsidiaries was once (1925–54) a manufacturer of motor coaches and trolley coaches und ...

. He was vice president of Budd Company

The Budd Company was a 20th-century metal fabricator, a major supplier of body components to the automobile industry, and a manufacturer of stainless steel passenger rail cars, airframes, missile and space vehicles, and various defense products ...

from 1967 to 1969, when he retired to live in Jupiter, Florida, Holloway and his wife Harriet subsequently moved to Winter Haven, Florida

Winter Haven is a city in Polk County, Florida, United States. It is fifty-one miles east of Tampa. The population was 49,219 at the 2020 census. According to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2019 estimates, this city had a population of 44,955, making i ...

, where his son Jerry, a retired United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

officer, lived. Holloway died there on June 18, 1991.

Notes

References

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Holloway, Marshall 1912 births 1991 deaths People from Oklahoma Cornell University alumni University of Florida alumni 20th-century American physicists Manhattan Project people MIT Lincoln Laboratory people