A mammal () is a

vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

animal of the

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of

milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

-producing

mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland that produces milk in humans and other mammals. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, human ...

s for feeding their young, a broad

neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

region of the brain,

fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

or

hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and ...

, and three

middle ear bones. These characteristics distinguish them from

reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s and

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, from which their ancestors

diverged in the

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

Period over 300 million years ago. Around 6,640

extant

Extant or Least-concern species, least concern is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Exta ...

species of mammals have been described and divided into 27

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

. The study of mammals is called

mammalogy

In zoology, mammalogy is the study of mammals – a class of vertebrates with characteristics such as homeothermic metabolism, fur, four-chambered hearts, and complex nervous systems. The archive of number of mammals on earth is constantly growi ...

.

The largest orders of mammals, by number of

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, are the

rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s,

bat

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

s, and

eulipotyphla

Eulipotyphla (, from '' eu-'' + '' Lipotyphla'', meaning truly lacking blind gut; sometimes called true insectivores) is an order of mammals comprising the Erinaceidae ( hedgehogs and gymnures); Solenodontidae (solenodons); Talpidae ( mole ...

ns (including

hedgehog

A hedgehog is a spiny mammal of the subfamily Erinaceinae, in the eulipotyphlan family Erinaceidae. There are 17 species of hedgehog in five genera found throughout parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and in New Zealand by introduction. The ...

s,

mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole"

* Golden mole, southern African mammals

* Marsupial mole

Marsupial moles, the Notoryctidae family, are two species of highly specialized marsupial mammals that are found i ...

s and

shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s). The next three are the

primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s (including

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s,

monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

s and

lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s), the

even-toed ungulate

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s (including

pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), also called swine (: swine) or hog, is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of the genus '' Sus''. Some authorities cons ...

s,

camel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

s, and

whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s), and the

Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

(including

cats

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

,

dogs

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers ...

, and

seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

).

Mammals are the only living members of

Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

; this

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, together with

Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

(reptiles and birds), constitutes the larger

Amniota

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibious stem tetrapod ancestors during the C ...

clade. Early synapsids are referred to as "

pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

s." The more advanced

therapsids

Therapsida is a clade comprising a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals and their ancestors and close relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including li ...

became dominant during the

Guadalupian

The Guadalupian is the second and middle Series (stratigraphy), series/Epoch (geology), epoch of the Permian. The Guadalupian was preceded by the Cisuralian and followed by the Lopingian. It is named after the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico an ...

. Mammals originated from

cynodonts

Cynodontia () is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extinct ances ...

, an advanced group of therapsids, during the Late

Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

to Early

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

. Mammals achieved their modern diversity in the

Paleogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

and

Neogene

The Neogene ( ,) is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period million years ago. It is the second period of th ...

periods of the

Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

era, after the

extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, and have been the

dominant terrestrial animal group from 66 million years ago to the present.

The basic mammalian body type is

quadrupedal

Quadrupedalism is a form of Animal locomotion, locomotion in which animals have four legs that are used to weight-bearing, bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four l ...

, with most mammals using four

limbs for

terrestrial locomotion

Terrestrial locomotion has evolution, evolved as animals adapted from ecoregion#Marine, aquatic to ecoregion#Terrestrial, terrestrial environments. Animal locomotion, Locomotion on land raises different problems than that in water, with reduced f ...

; but in some, the limbs are adapted for life

at sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

,

in the air

IN, In or in may refer to:

Dans

* India (country code IN)

* Indiana, United States (postal code IN)

* Ingolstadt, Germany (license plate code IN)

* In, Russia, a town in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Businesses and organizations

* Independen ...

,

in trees or

underground. The

bipeds

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an animal moves by means of its two rear (or lower) Limb (anatomy), limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from ...

have adapted to move using only the two lower limbs, while the rear limbs of

cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

and the

sea cows

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea cows or sirenians, are an order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The extant Sirenia comprise two distinct famili ...

are mere internal

vestiges. Mammals range in size from the

bumblebee bat

Kitti's hog-nosed bat (''Craseonycteris thonglongyai''), also known as the bumblebee bat, is a near-threatened species of bat and the only extant member of the family Craseonycteridae. It occurs in western Thailand and southeast Myanmar, where it ...

to the

blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

—possibly the largest animal to have ever lived. Maximum lifespan varies from two years for the shrew to 211 years for the

bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus''), sometimes called the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, and polar whale, is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus '' Balaena' ...

. All modern mammals give birth to live young, except the five species of

monotreme

Monotremes () are mammals of the order Monotremata. They are the only group of living mammals that lay eggs, rather than bearing live young. The extant monotreme species are the platypus and the four species of echidnas. Monotremes are typified ...

s, which lay eggs. The most species-rich group is the

viviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

placental mammals

Placental mammals ( infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguish ...

, so named for the temporary organ (

placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between ...

) used by offspring to draw nutrition from the mother during

gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregn ...

.

Most mammals are

intelligent, with some possessing large brains,

self-awareness

In philosophy of self, philosophy, self-awareness is the awareness and reflection of one's own personality or individuality, including traits, feelings, and behaviors. It is not to be confused with consciousness in the sense of qualia. While ...

, and

tool use

Tool use by non-humans is a phenomenon in which a non-human animal uses any kind of tool in order to achieve a goal such as acquiring food and water, grooming, combat, defence, communication, recreation or construction. Originally thought to b ...

. Mammals can communicate and vocalise in several ways, including the production of

ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

,

scent marking

In ethology, territory is the sociographical area that an animal consistently defends against conspecific competition (or, occasionally, against animals of other species) using agonistic behaviors or (less commonly) real physical aggression. ...

,

alarm signal

In animal communication, an alarm signal is an antipredator adaptation in the form of signals emitted by social animals in response to danger. Many primates and birds have elaborate alarm calls for warning conspecifics of approaching predators ...

s,

singing

Singing is the art of creating music with the voice. It is the oldest form of musical expression, and the human voice can be considered the first musical instrument. The definition of singing varies across sources. Some sources define singi ...

,

echolocation; and, in the case of humans, complex

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

. Mammals can organise themselves into

fission–fusion societies,

harems

A harem is a domestic space that is reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic Domestic worker, servants, and other un ...

, and

hierarchies

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an importan ...

—but can also be solitary and

territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

. Most mammals are

polygynous

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

, but some can be

monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a relationship of two individuals in which they form a mutual and exclusive intimate partnership. Having only one partner at any one time, whether for life or serial monogamy, contrasts with various forms of non-monogamy (e.g. ...

or

polyandrous

Polyandry (; ) is a form of polygamy in which a woman takes two or more husbands at the same time. Polyandry is contrasted with polygyny, involving one male and two or more females. If a marriage involves a plural number of "husbands and wives ...

.

Domestication

Domestication is a multi-generational Mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a st ...

of many types of mammals by humans played a major role in the

Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

, and resulted in

farming

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

replacing

hunting and gathering

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially wi ...

as the primary source of food for humans. This led to a major restructuring of human societies from nomadic to sedentary, with more co-operation among larger and larger groups, and ultimately the development of the first

civilisation

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of the state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond signed or spoken languag ...

s. Domesticated mammals provided, and continue to provide, power for transport and agriculture, as well as food (

meat

Meat is animal Tissue (biology), tissue, often muscle, that is eaten as food. Humans have hunted and farmed other animals for meat since prehistory. The Neolithic Revolution allowed the domestication of vertebrates, including chickens, sheep, ...

and

dairy product

Dairy products or milk products are food products made from (or containing) milk. The most common dairy animals are cow, water buffalo, goat, nanny goat, and Sheep, ewe. Dairy products include common grocery store food around the world such as y ...

s),

fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

, and

leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning (leather), tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffal ...

. Mammals are also

hunted and raced for sport, kept as

pet

A pet, or companion animal, is an animal kept primarily for a person's company or entertainment rather than as a working animal, livestock, or a laboratory animal. Popular pets are often considered to have attractive/ cute appearances, inte ...

s and

working animal

A working animal is an animal, usually domesticated, that is kept by humans and trained to perform tasks. Some are used for their physical strength (e.g. oxen and draft horses) or for transportation (e.g. riding horses and camels), while oth ...

s of various types, and are used as

model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

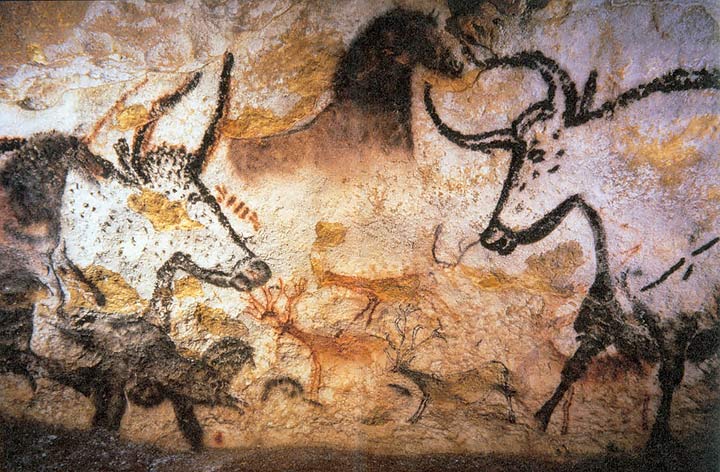

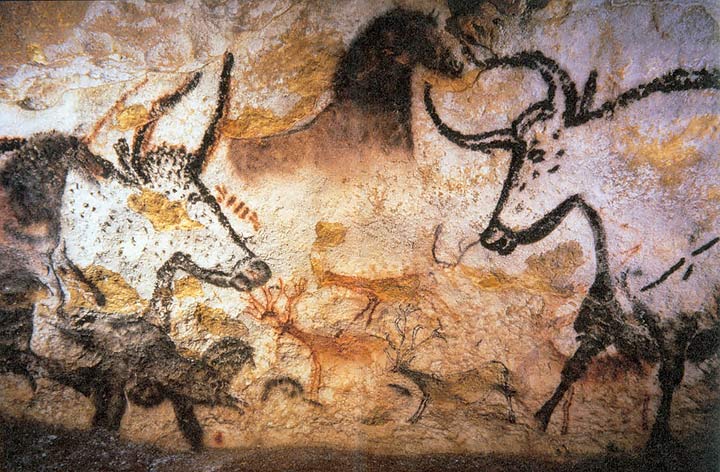

s in science. Mammals have been depicted in

art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

since

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

times, and appear in literature, film, mythology, and religion. Decline in numbers and

extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

of many mammals is primarily driven by human

poaching

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the huntin ...

and

habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss or habitat reduction) occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved elsewhere, or are dead, leading to a decrease ...

, primarily

deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. Ab ...

.

Classification

Mammal classification has been through several revisions since

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

initially defined the class, and at present, no classification system is universally accepted. McKenna & Bell (1997) and Wilson & Reeder (2005) provide useful recent compendiums.

Simpson

Simpson may refer to:

* Simpson (name), a British surname

Organizations Schools

*Simpson College, in Indianola, Iowa

*Simpson University, in Redding, California

Businesses

*Simpson (appliance manufacturer), former manufacturer and brand of w ...

(1945)

provides

systematics

Systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: phylogenetic trees, phylogenies). Phy ...

of mammal origins and relationships that had been taught universally until the end of the 20th century.

However, since 1945, a large amount of new and more detailed information has gradually been found: The

paleontological record has been recalibrated, and the intervening years have seen much debate and progress concerning the theoretical underpinnings of systematisation itself, partly through the new concept of

cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

. Though fieldwork and lab work progressively outdated Simpson's classification, it remains the closest thing to an official classification of mammals, despite its known issues.

Most mammals, including the six most species-rich orders, belong to the placental group. The three largest orders in numbers of species are

Rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

ia:

mice

A mouse (: mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

,

rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

s,

porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp Spine (zoology), spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two Family (biology), families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New ...

s,

beaver

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

s,

capybara

The capybara or greater capybara (''Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris'') is the largest living rodent, native to South America. It is a member of the genus '' Hydrochoerus''. The only other extant member is the lesser capybara (''Hydrochoerus isthmi ...

s, and other gnawing mammals;

Chiroptera

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

: bats; and

Eulipotyphla

Eulipotyphla (, from '' eu-'' + '' Lipotyphla'', meaning truly lacking blind gut; sometimes called true insectivores) is an order of mammals comprising the Erinaceidae ( hedgehogs and gymnures); Solenodontidae (solenodons); Talpidae ( mole ...

:

shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s,

moles, and

solenodon

Solenodons (from , 'channel' or 'pipe' and , 'tooth') are venomous, nocturnal, burrowing, insectivorous mammals belonging to the family Solenodontidae . The two living solenodon species are the Cuban solenodon (''Atopogale cubana'') and t ...

s. The next three biggest orders, depending on the

biological classification

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon), and these groups are give ...

scheme used, are the

primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s:

ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found global ...

s,

monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

s, and

lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s;

Cetartiodactyla

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order (biology), order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof ...

:

whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s and

even-toed ungulate

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s; and

Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

which includes

cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

s,

dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. ...

s,

weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets, and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slend ...

s,

bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

s,

seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

, and allies.

According to ''

Mammal Species of the World

''Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference'' is a standard reference work in mammalogy giving descriptions and Bibliographic database, bibliographic data for the known species of mammals. It is now in its third edition, ...

'', 5,416 species were identified in 2006. These were grouped into 1,229

genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

, 153

families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

and 29 orders.

In 2008, the

International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

(IUCN) completed a five-year Global Mammal Assessment for its

IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

, which counted 5,488 species. According to research published in the ''

Journal of Mammalogy

The ''Journal of Mammalogy'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Society of Mammalogists. Both the society and the journal were established in 1919. The journal covers rese ...

'' in 2018, the number of recognised mammal species is 6,495, including 96 recently extinct.

Definitions

The word "

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

" is modern, from the scientific name ''Mammalia'' coined by

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in 1758, derived from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''

mamma'' ("teat, pap"). In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe defined Mammalia

phylogenetically

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

as the

crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor ...

of mammals, the

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

consisting of the

most recent common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of living

monotreme

Monotremes () are mammals of the order Monotremata. They are the only group of living mammals that lay eggs, rather than bearing live young. The extant monotreme species are the platypus and the four species of echidnas. Monotremes are typified ...

s (

echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the Family (biology), family Tachyglossidae , living in Australia and New Guinea. The four Extant taxon, extant species of echidnas ...

s and platypuses) and therians (marsupials and placentals) and all descendants of that ancestor. Since this ancestor lived in the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

period, Rowe's definition excludes all animals from the earlier

Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, despite the fact that Triassic fossils in the Haramiyida have been referred to the Mammalia since the mid-19th century. If Mammalia is considered as the crown group, its origin can be roughly dated as the first known appearance of animals more closely related to some extant mammals than to others. ''Ambondro mahabo, Ambondro'' is more closely related to monotremes than to therian mammals while ''Amphilestes'' and ''Amphitherium'' are more closely related to the therians; as fossils of all three genera are dated about in the Middle Jurassic, this is a reasonable estimate for the appearance of the crown group.

T. S. Kemp has provided a more traditional definition: "Synapsids that possess a dentary–squamosal bone, squamosal jaw articulation and occlusion (dentistry), occlusion between upper and lower molars with a transverse component to the movement" or, equivalently in Kemp's view, the clade originating with the last common ancestor of ''Sinoconodon'' and living mammals. The earliest-known synapsid satisfying Kemp's definitions is ''Tikitherium'', dated , so the appearance of mammals in this broader sense can be given this Late Triassic date. However, this animal may have actually evolved during the Neogene.

Molecular classification of placentals

As of the early 21st century, molecular studies based on DNA analysis have suggested new relationships among mammal families. Most of these findings have been independently validated by retrotransposon retrotransposon marker, presence/absence data.

Classification systems based on molecular studies reveal three major groups or lineages of placentals—Afrotheria, Xenarthra and Boreoeutheria—which speciation, diverged in the Cretaceous. The relationships between these three lineages is contentious, and all three possible hypotheses have been proposed with respect to which group is Basal (phylogenetics), basal. These hypotheses are Atlantogenata (basal Boreoeutheria), Epitheria (basal Xenarthra) and Exafroplacentalia (basal Afrotheria).

Boreoeutheria in turn contains two major lineages—Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria.

Estimates for the divergence times between these three placental groups range from 105 to 120 million years ago, depending on the type of DNA used (such as nuclear DNA, nuclear or mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial) and varying interpretations of paleogeographic data.

[

Mammal phylogeny according to Álvarez-Carretero ''et al.'', 2022:

]

Evolution

Origins

Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

, a clade that contains mammals and their extinct relatives, originated during the Pennsylvanian (geology), Pennsylvanian subperiod (~323 million to ~300 million years ago), when they split from the reptile lineage. Crown group mammals evolved from earlier Mammaliaformes, mammaliaforms during the Early Jurassic. The cladogram takes Mammalia to be the crown group.

Evolution from older amniotes

The first fully terrestrial

The first fully terrestrial vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s were amniotes. Like their amphibious early tetrapod predecessors, they had lungs and limbs. Amniotic eggs, however, have internal membranes that allow the developing embryo to breathe but keep water in. Hence, amniotes can lay eggs on dry land, while amphibians generally need to lay their eggs in water.

The first amniotes apparently arose in the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

. They descended from earlier Reptiliomorpha, reptiliomorph amphibious tetrapods,bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s). Synapsids have a single hole (temporal fenestra) low on each side of the skull. Primitive synapsids included the largest and fiercest animals of the early Permian such as ''Dimetrodon''. Nonmammalian synapsids were traditionally—and incorrectly—called "mammal-like reptiles" or pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

s; we now know they were neither reptiles nor part of reptile lineage.[

Therapsids, a group of synapsids, evolved in the Guadalupian, Middle Permian, about 265 million years ago, and became the dominant land vertebrates.][ The therapsid lineage leading to mammals went through a series of stages, beginning with animals that were very similar to their early synapsid ancestors and ending with probainognathian cynodonts, some of which could easily be mistaken for mammals. Those stages were characterised by:]

First mammals

The Permian–Triassic extinction event about 252 million years ago, which was a prolonged event due to the accumulation of several extinction pulses, ended the dominance of carnivorous therapsids. In the early Triassic, most medium to large land carnivore niches were taken over by archosaurs which, over an extended period (35 million years), came to include the Crocodylomorpha, crocodylomorphs, the pterosaurs and the dinosaurs; however, large cynodonts like ''Trucidocynodon'' and Traversodontidae, traversodontids still occupied large sized carnivorous and herbivorous niches respectively. By the Jurassic, the dinosaurs had come to dominate the large terrestrial herbivore niches as well.

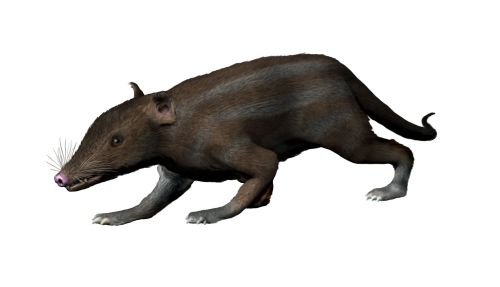

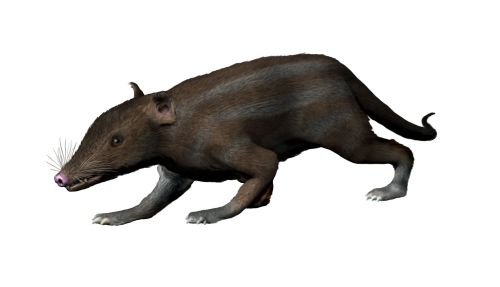

The first mammals (in Kemp's sense) appeared in the Late Triassic epoch (about 225 million years ago), 40 million years after the first therapsids. They expanded out of their nocturnal insectivore niche from the mid-Jurassic onwards; the Jurassic ''Castorocauda'', for example, was a close relative of true mammals that had adaptations for swimming, digging and catching fish. Most, if not all, are thought to have remained nocturnal (the nocturnal bottleneck), accounting for much of the typical mammalian traits. The majority of the mammal species that existed in the Mesozoic, Mesozoic Era were multituberculates, eutriconodonts and spalacotheriids. The oldest-known fossil among the Eutheria ("true beasts") is the small shrewlike ''Juramaia, Juramaia sinensis'', or "Jurassic mother from China", dated to 160 million years ago in the late Jurassic.

The oldest-known fossil among the Eutheria ("true beasts") is the small shrewlike ''Juramaia, Juramaia sinensis'', or "Jurassic mother from China", dated to 160 million years ago in the late Jurassic.

Earliest appearances of features

''Hadrocodium'', whose fossils date from approximately 195 million years ago, in the early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, provides the first clear evidence of a jaw joint formed solely by the squamosal and dentary bones; there is no space in the jaw for the articular, a bone involved in the jaws of all early synapsids. The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of ''Castorocauda'' and ''Megaconus'', from 164 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic. In the 1950s, it was suggested that the foramina (passages) in the maxillae and premaxillae (bones in the front of the upper jaw) of cynodonts were channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae (whiskers) and so were evidence of hair or fur;

The earliest clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of ''Castorocauda'' and ''Megaconus'', from 164 million years ago in the mid-Jurassic. In the 1950s, it was suggested that the foramina (passages) in the maxillae and premaxillae (bones in the front of the upper jaw) of cynodonts were channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae (whiskers) and so were evidence of hair or fur;[ Modern monotremes have lower body temperatures and more variable metabolic rates than marsupials and placentals,]milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

production) was to keep eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes, the egg-laying mammals. In human females, mammary glands become fully developed during puberty, regardless of pregnancy.

Rise of the mammals

Therians took over the medium- to large-sized ecological niches in the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

, after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago emptied ecological space once filled by non-avian dinosaurs and other groups of reptiles, as well as various other mammal groups,

Anatomy

Distinguishing features

Living mammal species can be identified by the presence of sweat glands, including Mammary gland, those that are specialised to produce milk to nourish their young. In classifying fossils, however, other features must be used, since soft tissue glands and many other features are not visible in fossils.

Many traits shared by all living mammals appeared among the earliest members of the group:

* Jaw, Jaw joint – The dentary (the lower jaw bone, which carries the teeth) and the squamosal (a small cranial bone) meet to form the joint. In most gnathostomes, including early therapsids, the joint consists of the articular (a small bone at the back of the lower jaw) and Quadrate bone, quadrate (a small bone at the back of the upper jaw).[

* Middle ear – In crown-group mammals, sound is carried from the eardrum by a chain of three bones, the malleus, the incus and the stapes. Ancestrally, the malleus and the incus are derived from the articular and the quadrate bones that constituted the jaw joint of early therapsids.

* Tooth replacement – Teeth can be replaced once (diphyodonty) or (as in toothed whales and Muridae, murid rodents) not at all (Dentition, monophyodonty). Elephants, manatees, and kangaroos continually grow new teeth throughout their life (polyphyodonty).

* Prismatic enamel – The tooth enamel, enamel coating on the surface of a tooth consists of prisms, solid, rod-like structures extending from the dentin to the tooth's surface.

* Occipital condyles – Two knobs at the base of the skull fit into the topmost Cervical vertebrae, neck vertebra; most other tetrapods, in contrast, have only one such knob.

For the most part, these characteristics were not present in the Triassic ancestors of the mammals. Nearly all mammaliaforms possess an epipubic bone, the exception being modern placentals.][

]

Sexual dimorphism

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased sexual dimorphism, although some orders do not show any bias or are significantly female-biased (Lagomorpha). Sexual size dimorphism increases with body size across mammals (Rensch's rule), suggesting that there are parallel selection pressures on both male and female size. Male-biased dimorphism Sexual selection in mammals, relates to sexual selection on males through male–male competition for females, as there is a positive correlation between the degree of sexual selection, as indicated by mating systems, and the degree of male-biased size dimorphism. The degree of sexual selection is also positively correlated with male and female size across mammals. Further, parallel selection pressure on female mass is identified in that age at weaning is significantly higher in more

On average, male mammals are larger than females, with males being at least 10% larger than females in over 45% of investigated species. Most mammalian orders also exhibit male-biased sexual dimorphism, although some orders do not show any bias or are significantly female-biased (Lagomorpha). Sexual size dimorphism increases with body size across mammals (Rensch's rule), suggesting that there are parallel selection pressures on both male and female size. Male-biased dimorphism Sexual selection in mammals, relates to sexual selection on males through male–male competition for females, as there is a positive correlation between the degree of sexual selection, as indicated by mating systems, and the degree of male-biased size dimorphism. The degree of sexual selection is also positively correlated with male and female size across mammals. Further, parallel selection pressure on female mass is identified in that age at weaning is significantly higher in more polygynous

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

species, even when correcting for body mass. Also, the reproductive rate is lower for larger females, indicating that fecundity selection selects for smaller females in mammals. Although these patterns hold across mammals as a whole, there is considerable variation across orders.

Biological systems

The majority of mammals have seven cervical vertebrae (bones in the neck). The exceptions are the manatee and the two-toed sloth, which have six, and the three-toed sloth which has nine. All mammalian brains possess a neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

, a brain region unique to mammals. Placental brains have a corpus callosum, unlike monotremes and marsupials.

Circulatory systems

The mammalian heart has four chambers, two upper atrium (heart), atria, the receiving chambers, and two lower ventricle (heart), ventricles, the discharging chambers. The heart has four valves, which separate its chambers and ensures blood flows in the correct direction through the heart (preventing backflow). After gas exchange in the pulmonary capillaries (blood vessels in the lungs), oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via one of the four pulmonary veins. Blood flows nearly continuously back into the atrium, which acts as the receiving chamber, and from here through an opening into the left ventricle. Most blood flows passively into the heart while both the atria and ventricles are relaxed, but toward the end of the diastole, ventricular relaxation period, the left atrium will contract, pumping blood into the ventricle. The heart also requires nutrients and oxygen found in blood like other muscles, and is supplied via coronary circulation, coronary arteries.

Respiratory systems

The lungs of mammals are spongy and honeycombed. Breathing is mainly achieved with the diaphragm (anatomy), diaphragm, which divides the thorax from the abdominal cavity, forming a dome convex to the thorax. Contraction of the diaphragm flattens the dome, increasing the volume of the lung cavity. Air enters through the oral and nasal cavities, and travels through the larynx, trachea and bronchi, and expands the pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Relaxing the diaphragm has the opposite effect, decreasing the volume of the lung cavity, causing air to be pushed out of the lungs. During exercise, the abdominal wall muscle contraction, contracts, increasing pressure on the diaphragm, which forces air out quicker and more forcefully. The rib cage is able to expand and contract the chest cavity through the action of other respiratory muscles. Consequently, air is sucked into or expelled out of the lungs, always moving down its pressure gradient.

The lungs of mammals are spongy and honeycombed. Breathing is mainly achieved with the diaphragm (anatomy), diaphragm, which divides the thorax from the abdominal cavity, forming a dome convex to the thorax. Contraction of the diaphragm flattens the dome, increasing the volume of the lung cavity. Air enters through the oral and nasal cavities, and travels through the larynx, trachea and bronchi, and expands the pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Relaxing the diaphragm has the opposite effect, decreasing the volume of the lung cavity, causing air to be pushed out of the lungs. During exercise, the abdominal wall muscle contraction, contracts, increasing pressure on the diaphragm, which forces air out quicker and more forcefully. The rib cage is able to expand and contract the chest cavity through the action of other respiratory muscles. Consequently, air is sucked into or expelled out of the lungs, always moving down its pressure gradient.[ This type of lung is known as a bellows lung due to its resemblance to blacksmith bellows.]

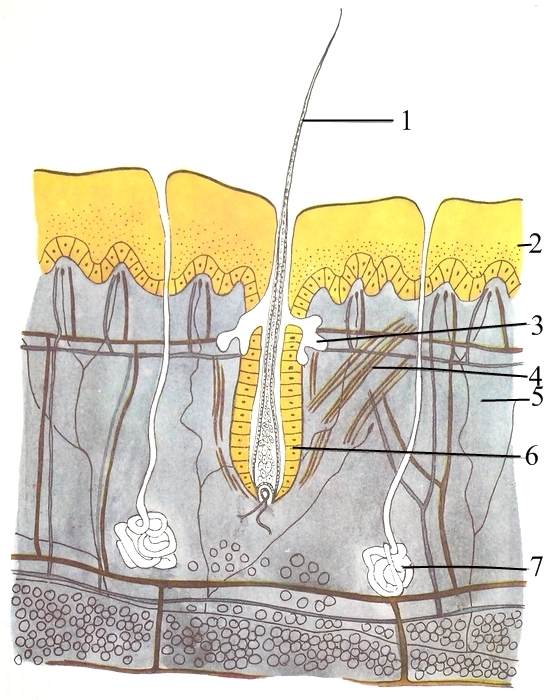

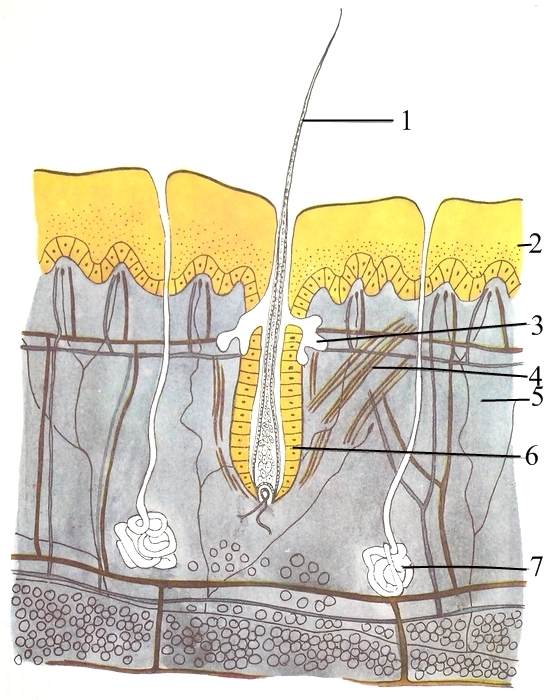

Integumentary systems

The skin, integumentary system (skin) is made up of three layers: the outermost epidermis (skin), epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis. The epidermis is typically 10 to 30 cells thick; its main function is to provide a waterproof layer. Its outermost cells are constantly lost; its bottommost cells are constantly dividing and pushing upward. The middle layer, the dermis, is 15 to 40 times thicker than the epidermis. The dermis is made up of many components, such as bony structures and blood vessels. The hypodermis is made up of adipose tissue, which stores lipids and provides cushioning and insulation. The thickness of this layer varies widely from species to species;

The skin, integumentary system (skin) is made up of three layers: the outermost epidermis (skin), epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis. The epidermis is typically 10 to 30 cells thick; its main function is to provide a waterproof layer. Its outermost cells are constantly lost; its bottommost cells are constantly dividing and pushing upward. The middle layer, the dermis, is 15 to 40 times thicker than the epidermis. The dermis is made up of many components, such as bony structures and blood vessels. The hypodermis is made up of adipose tissue, which stores lipids and provides cushioning and insulation. The thickness of this layer varies widely from species to species;[ marine mammals require a thick hypodermis (blubber) for insulation, and right whales have the thickest blubber at . Although other animals have features such as whiskers, feathers, setae, or cilia (entomology), cilia that superficially resemble it, no animals other than mammals have ]hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and ...

. It is a definitive characteristic of the class, though some mammals have very little.

Digestive systems

Herbivores have developed a diverse range of physical structures to facilitate the Herbivore adaptations to plant defense, consumption of plant material. To break up intact plant tissues, mammals have developed Mammal tooth, teeth structures that reflect their feeding preferences. For instance, frugivores (animals that feed primarily on fruit) and herbivores that feed on soft foliage have low-crowned teeth specialised for grinding foliage and seeds. Grazing animals that tend to eat hard, silica-rich grasses, have high-crowned teeth, which are capable of grinding tough plant tissues and do not wear down as quickly as low-crowned teeth. Most carnivorous mammals have carnassial teeth (of varying length depending on diet), long canines and similar tooth replacement patterns.

The stomach of even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla) is divided into four sections: the rumen, the Reticulum (anatomy), reticulum, the omasum and the abomasum (only ruminants have a rumen). After the plant material is consumed, it is mixed with saliva in the rumen and reticulum and separates into solid and liquid material. The solids lump together to form a bolus (digestion), bolus (or cud), and is regurgitated. When the bolus enters the mouth, the fluid is squeezed out with the tongue and swallowed again. Ingested food passes to the rumen and reticulum where cellulolytic microbes (bacterium, bacteria, protozoa and fungus, fungi) produce cellulase, which is needed to break down the cellulose in plants.

Excretory and genitourinary systems

The mammalian excretory system involves many components. Like most other land animals, mammals are ureotelic, and convert ammonia into urea, which is done by the liver as part of the urea cycle. Bilirubin, a waste product derived from blood cells, is passed through bile and urine with the help of enzymes excreted by the liver. The passing of bilirubin via bile through the intestinal tract gives mammalian feces a distinctive brown coloration. Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids, and of a clearly distinguishable renal cortex, cortex and renal medulla, medulla, which is due to the presence of elongated Loop of Henle, loops of Henle. Only the mammalian kidney has a bean shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of pinnipeds, cetaceans and bears.

The mammalian excretory system involves many components. Like most other land animals, mammals are ureotelic, and convert ammonia into urea, which is done by the liver as part of the urea cycle. Bilirubin, a waste product derived from blood cells, is passed through bile and urine with the help of enzymes excreted by the liver. The passing of bilirubin via bile through the intestinal tract gives mammalian feces a distinctive brown coloration. Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids, and of a clearly distinguishable renal cortex, cortex and renal medulla, medulla, which is due to the presence of elongated Loop of Henle, loops of Henle. Only the mammalian kidney has a bean shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of pinnipeds, cetaceans and bears.[ Most adult placentals have no remaining trace of the cloaca. In the embryo, the embryonic cloaca divides into a posterior region that becomes part of the anus, and an anterior region that has different fates depending on the sex of the individual: in females, it develops into the vulval vestibule, vestibule or Urogenital sinus#Other animals, urogenital sinus that receives the urethra and vagina, while in males it forms the entirety of the penile urethra.][ However, the Afrosoricida, afrosoricids and some ]shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s retain a cloaca as adults. In marsupials, the genital tract is separate from the anus, but a trace of the original cloaca does remain externally.[

]

Sound production

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a larynx that can quickly open and close to produce sounds, and a supralaryngeal vocal tract which filters this sound. The lungs and surrounding musculature provide the air stream and pressure required to phonate. The larynx controls the pitch (music), pitch and loudness, volume of sound, but the strength the lungs exert to exhale also contributes to volume. More primitive mammals, such as the echidna, can only hiss, as sound is achieved solely through exhaling through a partially closed larynx. Other mammals phonate using vocal folds. The movement or tenseness of the vocal folds can result in many sounds such as purring and screaming. Mammals can change the position of the larynx, allowing them to breathe through the nose while swallowing through the mouth, and to form both oral and nasalization, nasal sounds; nasal sounds, such as a dog whine, are generally soft sounds, and oral sounds, such as a dog bark, are generally loud.

As in all other tetrapods, mammals have a larynx that can quickly open and close to produce sounds, and a supralaryngeal vocal tract which filters this sound. The lungs and surrounding musculature provide the air stream and pressure required to phonate. The larynx controls the pitch (music), pitch and loudness, volume of sound, but the strength the lungs exert to exhale also contributes to volume. More primitive mammals, such as the echidna, can only hiss, as sound is achieved solely through exhaling through a partially closed larynx. Other mammals phonate using vocal folds. The movement or tenseness of the vocal folds can result in many sounds such as purring and screaming. Mammals can change the position of the larynx, allowing them to breathe through the nose while swallowing through the mouth, and to form both oral and nasalization, nasal sounds; nasal sounds, such as a dog whine, are generally soft sounds, and oral sounds, such as a dog bark, are generally loud.[

Some mammals have a large larynx and thus a low-pitched voice, namely the hammer-headed bat (''Hypsignathus monstrosus'') where the larynx can take up the entirety of the thoracic cavity while pushing the lungs, heart, and trachea into the abdomen. Large vocal pads can also lower the pitch, as in the low-pitched roars of big cats. The production of infrasound is possible in some mammals such as the African elephant (''Loxodonta'' spp.) and baleen whales. Small mammals with small larynxes have the ability to produce ]ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

, which can be detected by modifications to the middle ear and cochlea. Ultrasound is inaudible to birds and reptiles, which might have been important during the Mesozoic, when birds and reptiles were the dominant predators. This private channel is used by some rodents in, for example, mother-to-pup communication, and by bats when echolocating. Toothed whales also use echolocation, but, as opposed to the vocal membrane that extends upward from the vocal folds, they have a Melon (cetacean), melon to manipulate sounds. Some mammals, namely the primates, have air sacs attached to the larynx, which may function to lower the resonances or increase the volume of sound.[

]

Fur

The primary function of the fur of mammals is thermoregulation. Others include protection, sensory purposes, waterproofing, and camouflage.[

* Definitive – which may be moulting, shed after reaching a certain length

* Vibrissae – sensory hairs, most commonly whiskers

* Pelage – guard hairs, under-fur, and awn hair

* spine (zoology), Spines – stiff guard hair used for defence (such as in ]porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp Spine (zoology), spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two Family (biology), families of animals: the Old World porcupines of the family Hystricidae, and the New ...

s)

* Bristles – long hairs usually used in visual signals. (such as a lion's mane (lion), mane)

* Vellus hair, Velli – often called "down fur" which insulates newborn mammals

* Wool – long, soft and often curly

Thermoregulation

Hair length is not a factor in thermoregulation: for example, some tropical mammals such as sloths have the same length of fur length as some arctic mammals but with less insulation; and, conversely, other tropical mammals with short hair have the same insulating value as arctic mammals. The denseness of fur can increase an animal's insulation value, and arctic mammals especially have dense fur; for example, the musk ox has guard hairs measuring as well as a dense underfur, which forms an airtight coat, allowing them to survive in temperatures of .[ Some desert mammals, such as camels, use dense fur to prevent solar heat from reaching their skin, allowing the animal to stay cool; a camel's fur may reach in the summer, but the skin stays at .][ Aquatic mammals, conversely, trap air in their fur to conserve heat by keeping the skin dry.][

]

Coloration

Mammalian coats are coloured for a variety of reasons, the major selective pressures including camouflage, sexual selection, communication, and thermoregulation. Coloration in both the hair and skin of mammals is mainly determined by the type and amount of melanin; eumelanins for brown and black colours and pheomelanin for a range of yellowish to reddish colours, giving mammals an earth tone.[ The dazzling black-and-white striping of zebras appear to provide some protection from biting flies.]

Reproductive system

Mammals reproduce by internal fertilisation

Mammals reproduce by internal fertilisationechidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the Family (biology), family Tachyglossidae , living in Australia and New Guinea. The four Extant taxon, extant species of echidnas ...

penis generally has four heads with only two functioning. Depending on the species, an erection may be fuelled by blood flow into vascular, spongy tissue or by muscular action. The ancestral condition for mammal reproduction is the birthing of relatively undeveloped young, either through direct vivipary or a short period as soft-shelled eggs. This is likely due to the fact that the torso could not expand due to the presence of epipubic bones. The oldest demonstration of this reproductive style is with ''Kayentatherium'', which produced undeveloped perinates, but at much higher litter sizes than any modern mammal, 38 specimens.

The ancestral condition for mammal reproduction is the birthing of relatively undeveloped young, either through direct vivipary or a short period as soft-shelled eggs. This is likely due to the fact that the torso could not expand due to the presence of epipubic bones. The oldest demonstration of this reproductive style is with ''Kayentatherium'', which produced undeveloped perinates, but at much higher litter sizes than any modern mammal, 38 specimens.gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregn ...

period, typically shorter than its estrous cycle and generally giving birth to a number of undeveloped newborns that then undergo further development; in many species, this takes place within a pouch-like sac, the Pouch (marsupial), marsupium, located in the front of the mother's abdomen. This is the Symplesiomorphy, plesiomorphic condition among viviparous mammals; the presence of epipubic bones in all non-placentals prevents the expansion of the torso needed for full pregnancy.placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between ...

, which connects the developing fetus to the uterine wall to allow nutrient uptake. In placentals, the epipubic is either completely lost or converted into the baculum; allowing the torso to be able to expand and thus birth developed offspring.mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland that produces milk in humans and other mammals. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, human ...

s of mammals are specialised to produce milk, the primary source of nutrition for newborns. The monotremes branched early from other mammals and do not have the teats seen in most mammals, but they do have mammary glands. The young lick the milk from a mammary patch on the mother's belly. Compared to placental mammals, the milk of marsupials changes greatly in both production rate and in nutrient composition, due to the underdeveloped young. In addition, the mammary glands have more autonomy allowing them to supply separate milks to young at different development stages. Lactose is the main sugar in placental milk while monotreme and marsupial milk is dominated by oligosaccharides. Weaning is the process in which a mammal becomes less dependent on their mother's milk and more on solid food.

Endothermy

Nearly all mammals are endothermy, endothermic ("warm-blooded"). Most mammals also have hair to help keep them warm. Like birds, mammals can forage or hunt in weather and climates too cold for ectothermic ("cold-blooded") reptiles and insects. Endothermy requires plenty of food energy, so mammals eat more food per unit of body weight than most reptiles. Small insectivorous mammals eat prodigious amounts for their size. A rare exception, the naked mole-rat produces little metabolic heat, so it is considered an operational poikilotherm. Birds are also endothermic, so endothermy is not unique to mammals.

Species lifespan

Among mammals, species maximum lifespan varies significantly (for example the shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

has a lifespan of two years, whereas the oldest bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus''), sometimes called the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, and polar whale, is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus '' Balaena' ...

is recorded to be 211 years).

Locomotion

Terrestrial

Most vertebrates—the amphibians, the reptiles and some mammals such as humans and bears—are plantigrade, walking on the whole of the underside of the foot. Many mammals, such as cats and dogs, are digitigrade, walking on their toes, the greater stride length allowing more speed. Some animals such as horses are unguligrade, walking on the tips of their toes. This even further increases their stride length and thus their speed. A few mammals, namely the great apes, are also known to Knuckle-walking, walk on their knuckles, at least for their front legs. Giant anteaters and platypuses are also knuckle-walkers. Some mammals are bipedalism, bipeds, using only two limbs for locomotion, which can be seen in, for example, humans and the great apes. Bipedal species have a larger field of Mammalian vision, vision than quadrupeds, conserve more energy and have the ability to manipulate objects with their hands, which aids in foraging. Instead of walking, some bipeds hop, such as kangaroos and kangaroo rats.

Animals will use different gaits for different speeds, terrain and situations. For example, horses show four natural gaits, the slowest horse gait is the Horse gait#Walk, walk, then there are three faster gaits which, from slowest to fastest, are the trot (horse gait), trot, the canter and the Horse gait#Gallop, gallop. Animals may also have unusual gaits that are used occasionally, such as for moving sideways or backwards. For example, the main gait (human), human gaits are bipedal walking and running, but they employ many other gaits occasionally, including a four-legged crawling (human), crawl in tight spaces.