Malay Races Liberation Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army, was a communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army, was a communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army, was a communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army, was a communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) and later fought against the Malaysian government

The Government of Malaysia, officially the Federal Government of Malaysia ( ms, Kerajaan Persekutuan Malaysia), is based in the Federal Territory of Putrajaya with the exception of the legislative branch, which is located in Kuala Lumpur. Malay ...

in the Communist insurgency in Malaysia (1968–1989)

The Communist insurgency in Malaysia, also known as the Second Malayan Emergency ( ms, Perang insurgensi melawan pengganas komunis or ), was an armed conflict which occurred in Malaysia from 1968 to 1989, between the Malayan Communist Party ( ...

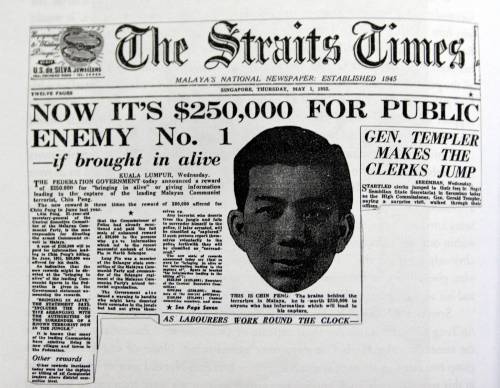

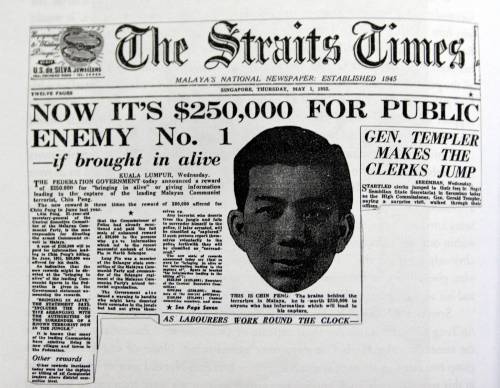

. Their leader was a trade union activist known as Chin Peng

Chin Peng (21 October 1924 – 16 September 2013), born Ong Boon Hua, was a Malayan communist politician, anti-fascist activist and long-time leader of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA).

During W ...

who had previously been awarded an OBE by the British for waging a guerrilla war against the Japanese occupation of Malaya

The then British colony of Malaya was gradually occupied by the Japanese between 8 December 1941 and the Allied surrender at Singapore on 16 February 1942. The Japanese remained in occupation until their surrender to the Allies in 1945. The ...

. Many MNLA fighters were former members of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a communist guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945. Composed mainly of ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest anti-Japanese res ...

(MPAJA) which had been previously trained and funded by the British to fight against Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

In 1989 the Malayan Communist Party signed a peace treaty with the Malaysian state and the MNLA and the Party settled in villages in southern Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

.

History

The MNLA was a guerrilla force created by theMalayan Communist Party

The Malayan Communist Party (MCP), officially the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), was a Marxist–Leninist and anti-imperialist communist party which was active in British Malaya and later, the modern states of Malaysia and Singapore from 1 ...

(MCP). Many MNLA fighters were previously members of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a communist guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945. Composed mainly of Malaysian Chinese, ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest ...

(MPAJA), another guerrilla force which the British had secretly trained and armed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

to fight against the Japanese occupiers. The Communist Party, which had been banned in the pre-war years, was thereafter granted legal recognition by the British after the war as a reward for its wartime effort but had secretly kept some of the MPAJA's weapons for future use. The MCP used violence to support its union organisation, and the British used restrictions, including banishing key communist leaders not born locally, in an attempt to restrict trade union activity. This mutual antagonism climaxed with an armed revolt in 1948, which resulted in the declaration of a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

in June 1948.

The Malayan Emergency (1948–1960)

On 16 June 1948, three British plantation managers were assassinated inPerak

Perak () is a state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kelantan and Pahang to the east, and Selangor to the south. Thailand's ...

. In response to these murders the British colonial authorities enacted emergency measures which included outlawing leftist parties and conducting mass arrests of trade union activists and communists. Fleeing the cities, Malayan Communist Party activists and their supporters (including Chin Peng) regrouped deep in the Malayan jungles and founded the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), a guerrilla army to wage a guerilla war against the British authorities. In an attempt to force the British to leave Malaya, the MNLA conducted attacks against soldiers, police, colonial collaborators, and conducted industrial sabotage. During the early years of the Emergency, the MNLA guerrillas would destroy rubber plantations in an attempt to harm the British economy whose war-time debt to the Americans and post-war social programs partially relied on the profits of the Malayan rubber trade. These guerrillas were supported by a network of civilian supporters called the Min Yuen, whose members would live a normal life in towns while gathering intelligence, recruiting new members, spreading propaganda and collecting supplies for the MNLA.

The MNLA allowed people of any race as well as women to join the guerrilla army as any prejudice between race and sex was believed by the MNLA and MCP to be a tool of capitalism to divide the working class. Due to their location deep within Malaya's jungles, the MNLA often came into contact with the aboriginal Orang Asli

Orang Asli (''lit''. "first people", "native people", "original people", "aborigines people" or "aboriginal people" in Malay) are a heterogeneous indigenous population forming a national minority in Malaysia. They are the oldest inhabitants of ...

, recruiting them as trackers and using their villages as a food source. However, despite their attempts to recruit from all ethnic backgrounds, the MNLA membership was still overwhelmingly made up of ethnic Chinese.

Less than a month into the Emergency, Britain's High Commissioner in Malaya Edward Gent

Sir Edward James Gent (28 October 1895 – 4 July 1948) was the first appointed Governor of the Malayan Union in 1946. He was most famous for heading early British attempts to crush a pro-independence uprising in Malaya led by the Malayan Comm ...

died in an airplane collision. In 1951 his replacement, Henry Gurney

Sir Henry Lovell Goldsworthy Gurney (27 June 1898 – 6 October 1951) was a British colonial administrator who served in various posts throughout the British Empire. Gurney was killed by communist insurgents during the Malayan Emergency, whi ...

was assassinated by MNLA guerrillas in an ambush against his convoy near Fraser's Hill

Fraser's Hill is a hill resort located on the Titiwangsa Mountains, Titiwangsa Ridge in Raub District, Pahang, Malaysia. It is about north of Kuala Lumpur. In 1890, Louis James Fraser established the area as a tin mining community known as Pa ...

resort. The next High Commissioner was Gerald Templer

Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer, (11 September 1898 – 25 October 1979) was a senior British Army officer. He fought in both the world wars and took part in the crushing of the Arab Revolt in Palestine. As Chief of the Imperia ...

who is credited by many historians as being the most effective in defeating the MNLA guerrillas. Templer oversaw the finalising of the Briggs Plan

The Briggs Plan ( ms, Rancangan Briggs) was a military plan devised by British General Sir Harold Briggs shortly after his appointment in 1950 as Director of Operations during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960). The plan aimed to defeat the Ma ...

, the British military strategy to defeat Malaysian guerrillas by forcibly transferring most of Malaysia's ethnic-Chinese population to a series of newly constructed settlements known as "new villages". By early 1952 over 400,000 people (mostly ethnic Chinese) had been moved to the "New villages". Templer then attempted to starve the MNLA out of the jungles by torching farmland, spraying chemical herbicides from airplanes to destroy crops, and enforcing a striction rationing system for Malayan villagers so that they could not share food with MNLA members. In the New village of Tanjung Malim

Tanjung Malim, or Tanjong Malim, is a town in Muallim District, Perak, Malaysia. It is approximately north of Kuala Lumpur and 120 km south of Ipoh via the North–South Expressway. It lies on the Perak-Selangor state border, with Sun ...

, the rice rations were halved after the population refused to give information on communist activities in the region.

The Briggs Plan and the New Village internment camps had succeeded in separating the civilian population from the MNLA guerrillas in the jungles and severely damaged their ability to continue fighting. The food denial campaign also put great pressure on the MNLA and damaged their ability to conduct assaults against British positions.

The Emergency officially came to an end in 1960, although the MNLA had already been defeated as an effective fighting force for years.

Communist insurgency in Malaysia (1968–1989)

Defeated in the first Malayan emergency and outwitted in Singapore politics by nationalist politicianLee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), born Harry Lee Kuan Yew, often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean lawyer and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Singapore between 1959 and 1990, and Secretary-General o ...

, the MCP by the mid-1960s was fragmented. However, in 1968 the MNLA reappeared and operated from across the Thai border and carried out ambushes, hit-and-run attacks, as well as laid traps for Malaysian military. The MNLA fought in the highly forested area near the Thai border in the north of the Malay peninsula

The Malay Peninsula (Malay: ''Semenanjung Tanah Melayu'') is a peninsula in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area ...

. The MNLA was not able to reform to its former size and the MCP began recruitment of Thai Malays as well as distributing pamphlets preaching the compatibility between Islam and Communism. The MNLA had some success early on in the insurgency, at one point killing 17 members of the security forces in a single attack. In 1989, the MCP came to the negotiating table and reached an agreement with the Malaysian government which would allow MCP/MNLA members to return to Malaysia if they laid down their arms. Some MCP/MNLA members settled in "peace villages" in Southern Thailand, while others returned to Malaysia. However, Secretary-General of the MCP Chin Peng was subsequently denied the right to return to Malaysia in spite of the agreement between the MCP and the government.

Name and mistranslation

''Malayan Races Liberation Army'' is a translation from the Chinese "" where "" means "nationality" in the ethnic sense. The organization's leader Chin Peng has called this a mistranslation and corrected it to ''Malayan National Liberation Army'' (MNLA). The name of the MNLA in Malay ( ms, Tentera Pembebasan Rakyat Malaya) could also be translated as the Malayan People's Liberation Army although extant records show that the title ''Tentera Pembebasan Nasional Malaya'' or MNLA became the normal self-identity by the 1970s.References

{{Authority control Communism in Malaysia Defunct communist militant groups Military history of Malaysia Paramilitary organisations based in Malaysia Malayan Emergency Military wings of communist parties 1948 establishments in Malaya 1989 disestablishments Military units and formations established in 1948 Military units and formations disestablished in 1989