Mahler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

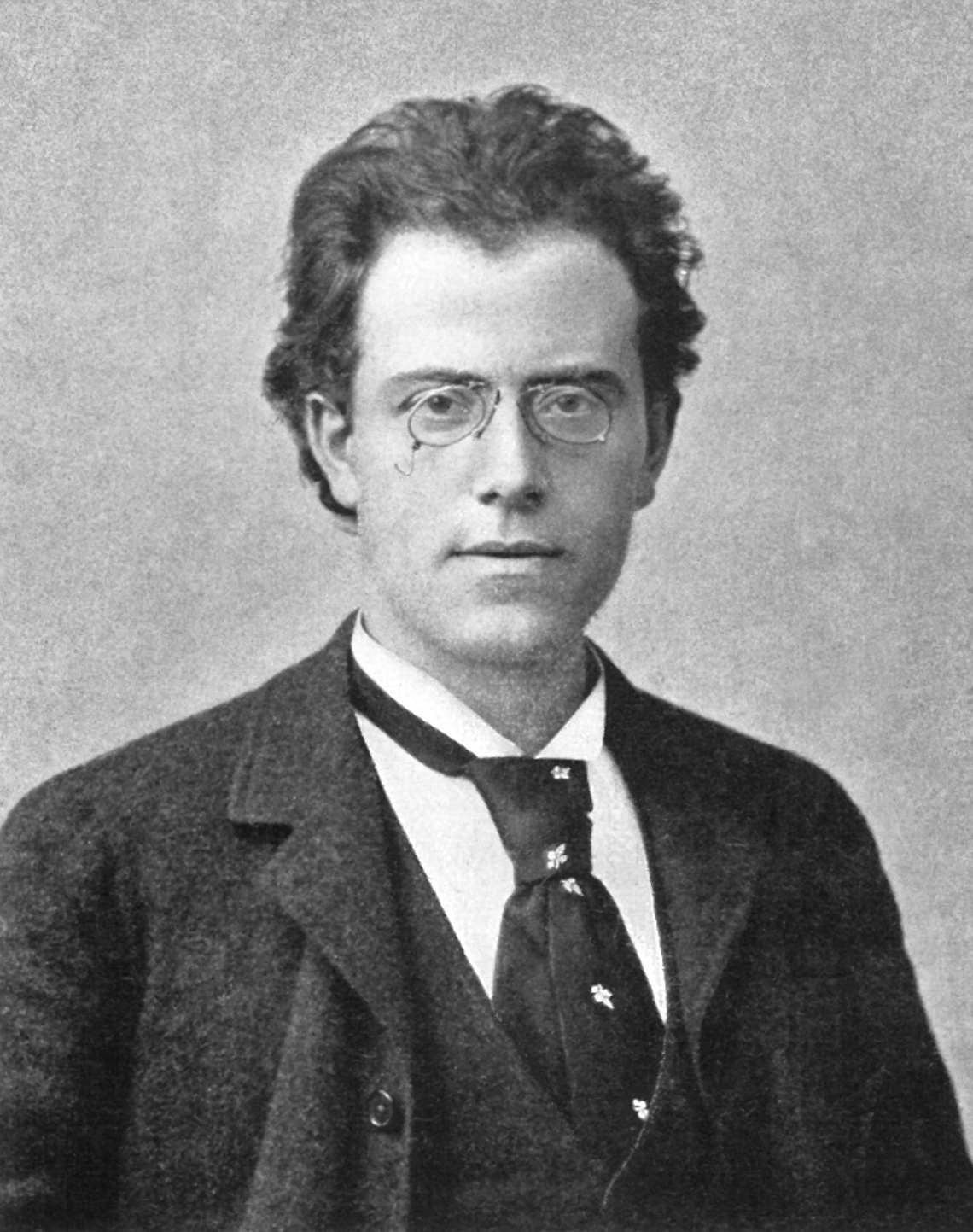

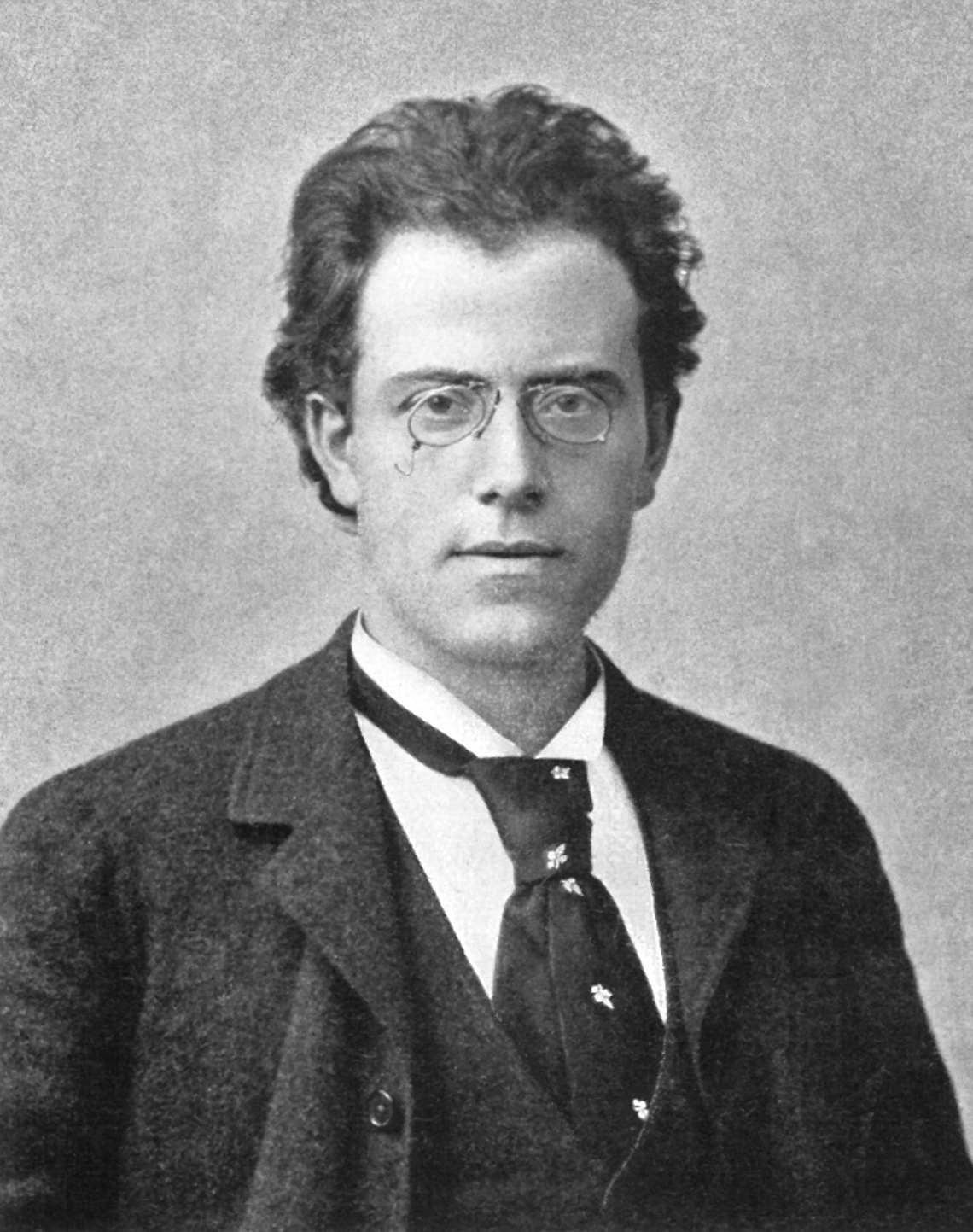

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the

The Mahler family came from eastern

The Mahler family came from eastern

In Prague, the emergence of the

In Prague, the emergence of the

In the early years of Mahler's conducting career, composing was a spare time activity. Between his Laibach and Olmütz appointments he worked on settings of verses by Richard Leander and Tirso de Molina, later collected as Volume I of ("Songs and Airs").Cooke, pp. 27–30 Mahler's first orchestral song cycle, , composed at Kassel, was based on his own verses, although the first poem, "" ("When my love becomes a bride") closely follows the text of a poem. The melodies for the second and fourth songs of the cycle were incorporated into the First Symphony, which Mahler finished in 1888, at the height of his relationship with Marion von Weber. The intensity of Mahler's feelings is reflected in the music, which originally was written as a five-movement symphonic poem with a descriptive programme. One of these movements, the "Blumine", later discarded, was based on a passage from his earlier work . After completing the symphony, Mahler composed a 20-minute symphonic poem, "Funeral Rites", which later became the first movement of his Second Symphony.

There has been frequent speculation about lost or destroyed works from Mahler's early years.Franklin, (10. , early songs, First symphony). The Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg believed that the First Symphony was too mature to be a first symphonic work, and must have had predecessors. In 1938, Mengelberg revealed the existence of the so-called "Dresden archive", a series of manuscripts in the possession of the widowed Marion von Weber.Mitchell, Vol II, pp. 51–53 According to the Mahler historian Donald Mitchell, it was highly likely that important Mahler manuscripts of early symphonic works had been held in Dresden; this archive, if it existed, was almost certainly destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

In the early years of Mahler's conducting career, composing was a spare time activity. Between his Laibach and Olmütz appointments he worked on settings of verses by Richard Leander and Tirso de Molina, later collected as Volume I of ("Songs and Airs").Cooke, pp. 27–30 Mahler's first orchestral song cycle, , composed at Kassel, was based on his own verses, although the first poem, "" ("When my love becomes a bride") closely follows the text of a poem. The melodies for the second and fourth songs of the cycle were incorporated into the First Symphony, which Mahler finished in 1888, at the height of his relationship with Marion von Weber. The intensity of Mahler's feelings is reflected in the music, which originally was written as a five-movement symphonic poem with a descriptive programme. One of these movements, the "Blumine", later discarded, was based on a passage from his earlier work . After completing the symphony, Mahler composed a 20-minute symphonic poem, "Funeral Rites", which later became the first movement of his Second Symphony.

There has been frequent speculation about lost or destroyed works from Mahler's early years.Franklin, (10. , early songs, First symphony). The Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg believed that the First Symphony was too mature to be a first symphonic work, and must have had predecessors. In 1938, Mengelberg revealed the existence of the so-called "Dresden archive", a series of manuscripts in the possession of the widowed Marion von Weber.Mitchell, Vol II, pp. 51–53 According to the Mahler historian Donald Mitchell, it was highly likely that important Mahler manuscripts of early symphonic works had been held in Dresden; this archive, if it existed, was almost certainly destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

In the summer of 1892 Mahler took the Hamburg singers to London to participate in an eight-week season of German opera—his only visit to Britain. His conducting of ''Tristan'' enthralled the young composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who "staggered home in a daze and could not sleep for two nights." However, Mahler refused further such invitations as he was anxious to reserve his summers for composing. In 1893 he acquired a retreat at Steinbach, on the banks of Lake Attersee in Upper Austria, and established a pattern that persisted for the rest of his life; summers would henceforth be dedicated to composition, at Steinbach or its successor retreats. Now firmly under the influence of the folk-poem collection, Mahler produced a stream of song settings at Steinbach, and composed his Second and Third Symphonies there.

Performances of Mahler works were still comparatively rare (he had not composed very much). On 27 October 1893, at Hamburg's Konzerthaus Ludwig, Mahler conducted a revised version of his First Symphony; still in its original five-movement form, it was presented as a (

In the summer of 1892 Mahler took the Hamburg singers to London to participate in an eight-week season of German opera—his only visit to Britain. His conducting of ''Tristan'' enthralled the young composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who "staggered home in a daze and could not sleep for two nights." However, Mahler refused further such invitations as he was anxious to reserve his summers for composing. In 1893 he acquired a retreat at Steinbach, on the banks of Lake Attersee in Upper Austria, and established a pattern that persisted for the rest of his life; summers would henceforth be dedicated to composition, at Steinbach or its successor retreats. Now firmly under the influence of the folk-poem collection, Mahler produced a stream of song settings at Steinbach, and composed his Second and Third Symphonies there.

Performances of Mahler works were still comparatively rare (he had not composed very much). On 27 October 1893, at Hamburg's Konzerthaus Ludwig, Mahler conducted a revised version of his First Symphony; still in its original five-movement form, it was presented as a (

On 8 October Mahler was formally appointed to succeed Jahn as the Hofoper's director. His first production in his new office was Smetana's Czech nationalist opera '' Dalibor'', with a reconstituted finale that left the hero Dalibor alive. This production caused anger among the more extreme Viennese German nationalists, who accused Mahler of "fraternising with the anti-dynastic, inferior Czech nation." The Austrian author Stefan Zweig, in his memoirs '' The World of Yesterday'' (1942), described Mahler's appointment as an example of the Viennese public's general distrust of young artists: "Once, when an amazing exception occurred and Gustav Mahler was named director of the Court Opera at thirty-eight years old, a frightened murmur and astonishment ran through Vienna, because someone had entrusted the highest institute of art to 'such a young person' ... This suspicion—that all young people were 'not very reliable'—ran through all circles at that time." Zweig also wrote that "to have seen Gustav Mahler on the street n Viennawas an event that one would proudly report to his comrades the next morning as it if were a personal triumph." During Mahler's tenure a total of 33 new operas were introduced to the Hofoper; a further 55 were new or totally revamped productions.La Grange, Vol. 3, pp. 941–944 However, a proposal to stage

On 8 October Mahler was formally appointed to succeed Jahn as the Hofoper's director. His first production in his new office was Smetana's Czech nationalist opera '' Dalibor'', with a reconstituted finale that left the hero Dalibor alive. This production caused anger among the more extreme Viennese German nationalists, who accused Mahler of "fraternising with the anti-dynastic, inferior Czech nation." The Austrian author Stefan Zweig, in his memoirs '' The World of Yesterday'' (1942), described Mahler's appointment as an example of the Viennese public's general distrust of young artists: "Once, when an amazing exception occurred and Gustav Mahler was named director of the Court Opera at thirty-eight years old, a frightened murmur and astonishment ran through Vienna, because someone had entrusted the highest institute of art to 'such a young person' ... This suspicion—that all young people were 'not very reliable'—ran through all circles at that time." Zweig also wrote that "to have seen Gustav Mahler on the street n Viennawas an event that one would proudly report to his comrades the next morning as it if were a personal triumph." During Mahler's tenure a total of 33 new operas were introduced to the Hofoper; a further 55 were new or totally revamped productions.La Grange, Vol. 3, pp. 941–944 However, a proposal to stage  In spite of numerous theatrical triumphs, Mahler's Vienna years were rarely smooth; his battles with singers and the house administration continued on and off for the whole of his tenure. While Mahler's methods improved standards, his histrionic and dictatorial conducting style was resented by orchestra members and singers alike. In December 1903 Mahler faced a revolt by stagehands, whose demands for better conditions he rejected in the belief that extremists were manipulating his staff. The anti-Semitic elements in Viennese society, long opposed to Mahler's appointment, continued to attack him relentlessly, and in 1907 instituted a press campaign designed to drive him out.Carr, pp. 150–151 By that time he was at odds with the opera house's administration over the amount of time he was spending on his own music, and was preparing to leave. In May 1907 he began discussions with Heinrich Conried, director of the New York

In spite of numerous theatrical triumphs, Mahler's Vienna years were rarely smooth; his battles with singers and the house administration continued on and off for the whole of his tenure. While Mahler's methods improved standards, his histrionic and dictatorial conducting style was resented by orchestra members and singers alike. In December 1903 Mahler faced a revolt by stagehands, whose demands for better conditions he rejected in the belief that extremists were manipulating his staff. The anti-Semitic elements in Viennese society, long opposed to Mahler's appointment, continued to attack him relentlessly, and in 1907 instituted a press campaign designed to drive him out.Carr, pp. 150–151 By that time he was at odds with the opera house's administration over the amount of time he was spending on his own music, and was preparing to leave. In May 1907 he began discussions with Heinrich Conried, director of the New York

The demands of his twin appointments in Vienna initially absorbed all Mahler's time and energy, but by 1899 he had resumed composing. The remaining Vienna years were to prove particularly fruitful. While working on some of the last of his settings he started his Fourth Symphony, which he completed in 1900. By this time he had abandoned the composing hut at Steinbach and had acquired another, at Maiernigg on the shores of the Wörthersee in

The demands of his twin appointments in Vienna initially absorbed all Mahler's time and energy, but by 1899 he had resumed composing. The remaining Vienna years were to prove particularly fruitful. While working on some of the last of his settings he started his Fourth Symphony, which he completed in 1900. By this time he had abandoned the composing hut at Steinbach and had acquired another, at Maiernigg on the shores of the Wörthersee in

During his second season in Vienna, Mahler acquired a spacious modern apartment on the Auenbruggergasse and built a summer villa on land he had acquired next to his new composing studio at Maiernigg. In November 1901, he met Alma Schindler, the stepdaughter of painter Carl Moll, at a social gathering that included the theatre director Max Burckhard.La Grange, Vol. 2, pp. 418–420 Alma was not initially keen to meet Mahler, on account of "the scandals about him and every young woman who aspired to sing in opera." The two engaged in a lively disagreement about a ballet by Alexander von Zemlinsky (Alma was one of Zemlinsky's pupils), but agreed to meet at the Hofoper the following day. This meeting led to a rapid courtship; Mahler and Alma were married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902. Alma was by then pregnant with her first child, a daughter Maria Anna, who was born on 3 November 1902. A second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904.

During his second season in Vienna, Mahler acquired a spacious modern apartment on the Auenbruggergasse and built a summer villa on land he had acquired next to his new composing studio at Maiernigg. In November 1901, he met Alma Schindler, the stepdaughter of painter Carl Moll, at a social gathering that included the theatre director Max Burckhard.La Grange, Vol. 2, pp. 418–420 Alma was not initially keen to meet Mahler, on account of "the scandals about him and every young woman who aspired to sing in opera." The two engaged in a lively disagreement about a ballet by Alexander von Zemlinsky (Alma was one of Zemlinsky's pupils), but agreed to meet at the Hofoper the following day. This meeting led to a rapid courtship; Mahler and Alma were married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902. Alma was by then pregnant with her first child, a daughter Maria Anna, who was born on 3 November 1902. A second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904.

Friends of the couple were surprised by the marriage and dubious of its wisdom. Burckhard called Mahler "that rachitic degenerate Jew", unworthy for such a good-looking girl of good family. On the other hand, Mahler's family considered Alma to be flirtatious, unreliable, and too fond of seeing young men fall for her charms. Mahler was by nature moody and authoritarian—Natalie Bauer-Lechner, his earlier partner, said that living with him was "like being on a boat that is ceaselessly rocked to and fro by the waves." Alma soon became resentful because of Mahler's insistence that there could only be one composer in the family and that she had given up her music studies to accommodate him. "The role of composer, the worker's role, falls to me, yours is that of a loving companion and understanding partner ... I'm asking a very great deal – and I can and may do so because I know what I have to give and will give in exchange." She wrote in her diary: "How hard it is to be so mercilessly deprived of ... things closest to one's heart."Carr, pp. 143–144 Mahler's requirement that their married life be organized around his creative activities imposed strains, and precipitated rebellion on Alma's part; the marriage was nevertheless marked at times by expressions of considerable passion, particularly from Mahler.

In the summer of 1907 Mahler, exhausted from the effects of the campaign against him in Vienna, took his family to Maiernigg. Soon after their arrival both daughters fell ill with

Friends of the couple were surprised by the marriage and dubious of its wisdom. Burckhard called Mahler "that rachitic degenerate Jew", unworthy for such a good-looking girl of good family. On the other hand, Mahler's family considered Alma to be flirtatious, unreliable, and too fond of seeing young men fall for her charms. Mahler was by nature moody and authoritarian—Natalie Bauer-Lechner, his earlier partner, said that living with him was "like being on a boat that is ceaselessly rocked to and fro by the waves." Alma soon became resentful because of Mahler's insistence that there could only be one composer in the family and that she had given up her music studies to accommodate him. "The role of composer, the worker's role, falls to me, yours is that of a loving companion and understanding partner ... I'm asking a very great deal – and I can and may do so because I know what I have to give and will give in exchange." She wrote in her diary: "How hard it is to be so mercilessly deprived of ... things closest to one's heart."Carr, pp. 143–144 Mahler's requirement that their married life be organized around his creative activities imposed strains, and precipitated rebellion on Alma's part; the marriage was nevertheless marked at times by expressions of considerable passion, particularly from Mahler.

In the summer of 1907 Mahler, exhausted from the effects of the campaign against him in Vienna, took his family to Maiernigg. Soon after their arrival both daughters fell ill with

Mahler made his New York debut at the

Mahler made his New York debut at the

In spite of the emotional distractions, during the summer of 1910 Mahler worked on his Tenth Symphony, completing the Adagio and drafting four more movements. He and Alma returned to New York in late October 1910, where Mahler threw himself into a busy Philharmonic season of concerts and tours. Around Christmas 1910 he began suffering from a sore throat, which persisted. On 21 February 1911, with a temperature of 40 °C (104 °F), Mahler insisted on fulfilling an engagement at

In spite of the emotional distractions, during the summer of 1910 Mahler worked on his Tenth Symphony, completing the Adagio and drafting four more movements. He and Alma returned to New York in late October 1910, where Mahler threw himself into a busy Philharmonic season of concerts and tours. Around Christmas 1910 he began suffering from a sore throat, which persisted. On 21 February 1911, with a temperature of 40 °C (104 °F), Mahler insisted on fulfilling an engagement at

Deryck Cooke and other analysts have divided Mahler's composing life into three distinct phases: a long "first period", extending from in 1880 to the end of the phase in 1901; a "middle period" of more concentrated composition ending with Mahler's departure for New York in 1907; and a brief "late period" of elegiac works before his death in 1911.

The main works of the first period are the first four symphonies, the song cycle and various song collections in which the songs predominate. In this period songs and symphonies are closely related and the symphonic works are programmatic. Mahler initially gave the first three symphonies full descriptive programmes, all of which he later repudiated. He devised, but did not publish, titles for each of the movements for the Fourth Symphony; from these titles the German music critic Paul Bekker conjectured a programme in which Death appears in the Scherzo "in the friendly, legendary guise of the fiddler tempting his flock to follow him out of this world."

The middle period comprises a

Deryck Cooke and other analysts have divided Mahler's composing life into three distinct phases: a long "first period", extending from in 1880 to the end of the phase in 1901; a "middle period" of more concentrated composition ending with Mahler's departure for New York in 1907; and a brief "late period" of elegiac works before his death in 1911.

The main works of the first period are the first four symphonies, the song cycle and various song collections in which the songs predominate. In this period songs and symphonies are closely related and the symphonic works are programmatic. Mahler initially gave the first three symphonies full descriptive programmes, all of which he later repudiated. He devised, but did not publish, titles for each of the movements for the Fourth Symphony; from these titles the German music critic Paul Bekker conjectured a programme in which Death appears in the Scherzo "in the friendly, legendary guise of the fiddler tempting his flock to follow him out of this world."

The middle period comprises a

Mahler's friend Guido Adler calculated that at the time of the composer's death in 1911 there had been more than 260 performances of the symphonies in Europe, Russia and America, the Fourth Symphony with 61 performances given most frequently (Adler did not enumerate performances of the songs). In his lifetime, Mahler's works and their performances attracted wide interest, but rarely unqualified approval; for years after its 1889 premiere critics and public struggled to understand the First Symphony, described by one critic after an 1898 Dresden performance as "the dullest ymphonicwork the new epoch has produced". The Second Symphony was received more positively, one critic calling it "the most masterly work of its kind since Mendelssohn". Such generous praise was rare, particularly after Mahler's accession to the Vienna Hofoper directorship. His many enemies in the city used the anti-Semitic and conservative press to denigrate almost every performance of a Mahler work; thus the Third Symphony, a success in Krefeld in 1902, was treated in Vienna with critical scorn: "Anyone who has committed such a deed deserves a couple of years in prison."

A mix of enthusiasm, consternation and critical contempt became the normal response to new Mahler symphonies, although the songs were better received. After his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies failed to gain general public approval, Mahler was convinced that his Sixth would finally succeed. However, its reception was dominated by satirical comments on Mahler's unconventional percussion effects—the use of a wooden mallet, birch rods and a huge square bass drum. Viennese critic Heinrich Reinhardt dismissed the symphony as "Brass, lots of brass, incredibly much brass! Even more brass, nothing but brass!" The one unalloyed performance triumph within Mahler's lifetime was the premiere of the Eighth Symphony in Munich, on 12 September 1910, advertised by its promoters as the "Symphony of a Thousand". At its conclusion, applause and celebrations reportedly lasted for half an hour.

Mahler's friend Guido Adler calculated that at the time of the composer's death in 1911 there had been more than 260 performances of the symphonies in Europe, Russia and America, the Fourth Symphony with 61 performances given most frequently (Adler did not enumerate performances of the songs). In his lifetime, Mahler's works and their performances attracted wide interest, but rarely unqualified approval; for years after its 1889 premiere critics and public struggled to understand the First Symphony, described by one critic after an 1898 Dresden performance as "the dullest ymphonicwork the new epoch has produced". The Second Symphony was received more positively, one critic calling it "the most masterly work of its kind since Mendelssohn". Such generous praise was rare, particularly after Mahler's accession to the Vienna Hofoper directorship. His many enemies in the city used the anti-Semitic and conservative press to denigrate almost every performance of a Mahler work; thus the Third Symphony, a success in Krefeld in 1902, was treated in Vienna with critical scorn: "Anyone who has committed such a deed deserves a couple of years in prison."

A mix of enthusiasm, consternation and critical contempt became the normal response to new Mahler symphonies, although the songs were better received. After his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies failed to gain general public approval, Mahler was convinced that his Sixth would finally succeed. However, its reception was dominated by satirical comments on Mahler's unconventional percussion effects—the use of a wooden mallet, birch rods and a huge square bass drum. Viennese critic Heinrich Reinhardt dismissed the symphony as "Brass, lots of brass, incredibly much brass! Even more brass, nothing but brass!" The one unalloyed performance triumph within Mahler's lifetime was the premiere of the Eighth Symphony in Munich, on 12 September 1910, advertised by its promoters as the "Symphony of a Thousand". At its conclusion, applause and celebrations reportedly lasted for half an hour.

Donald Mitchell writes that Mahler's influence on succeeding generations of composers is "a complete subject in itself".Mitchell, Vol. II, pp. 373–374 Mahler's first disciples included

Donald Mitchell writes that Mahler's influence on succeeding generations of composers is "a complete subject in itself".Mitchell, Vol. II, pp. 373–374 Mahler's first disciples included

Mahler Foundation

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mahler, Gustav 1860 births 1911 deaths 19th-century Austrian classical composers 19th-century Austrian conductors (music) 19th-century Austrian male musicians 20th-century Austrian classical composers 20th-century Austrian conductors (music) 20th-century Austrian male musicians Analysands of Sigmund Freud Austrian agnostics Austrian male classical composers Austrian people of Czech-Jewish descent Austrian Roman Catholics Austrian Romantic composers Jews from Austria-Hungary Converts to Roman Catholicism from Judaism Czech agnostics Czech conductors (music) Czech male classical composers Czech Roman Catholics Czech Romantic composers Deaths from sepsis Jewish agnostics Jewish classical composers Male conductors (music) Conductors of the Vienna Philharmonic Conductors of the Metropolitan Opera Music directors of the New York Philharmonic People from Pelhřimov District University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna alumni University of Vienna alumni Lieder composers

modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

of the early 20th century. While in his lifetime his status as a conductor was established beyond question, his own music gained wide popularity only after periods of relative neglect, which included a ban on its performance in much of Europe during the Nazi era. After 1945 his compositions were rediscovered by a new generation of listeners; Mahler then became one of the most frequently performed and recorded of all composers, a position he has sustained into the 21st century.

Born in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

(then part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

) to Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

parents of humble origins, the German-speaking Mahler displayed his musical gifts at an early age. After graduating from the Vienna Conservatory in 1878, he held a succession of conducting posts of rising importance in the opera houses of Europe, culminating in his appointment in 1897 as director of the Vienna Court Opera (Hofoper). During his ten years in Vienna, Mahler—who had converted to Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

to secure the post—experienced regular opposition and hostility from the anti-Semitic press. Nevertheless, his innovative productions and insistence on the highest performance standards ensured his reputation as one of the greatest of opera conductors, particularly as an interpreter of the stage works of Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

, and Tchaikovsky. Late in his life he was briefly director of New York's Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera is an American opera company based in New York City, currently resident at the Metropolitan Opera House (Lincoln Center), Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Referred ...

and the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic is an American symphony orchestra based in New York City. Known officially as the ''Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc.'', and globally known as the ''New York Philharmonic Orchestra'' (NYPO) or the ''New Yo ...

.

Mahler's ''œuvre'' is relatively limited; for much of his life composing was necessarily a part-time activity while he earned his living as a conductor. Aside from early works such as a movement from a piano quartet

A piano quartet is a chamber music composition for piano and three other instruments, or a musical ensemble comprising such instruments. Those other instruments are usually a string trio consisting of a violin, viola and cello.

Piano quartets for ...

composed when he was a student in Vienna, Mahler's works are generally designed for large orchestral forces, symphonic choruses and operatic soloists. These works were frequently controversial when first performed, and several were slow to receive critical and popular approval; exceptions included his Second Symphony, and the triumphant premiere of his Eighth Symphony in 1910. Some of Mahler's immediate musical successors included the composers of the Second Viennese School, notably Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian and American composer, music theorist, teacher and writer. He was among the first Modernism (music), modernists who transformed the practice of harmony in 20th-centu ...

, Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( ; ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

and Anton Webern

Anton Webern (; 3 December 1883 – 15 September 1945) was an Austrian composer, conductor, and musicologist. His music was among the most radical of its milieu in its lyric poetry, lyrical, poetic concision and use of then novel atonality, aton ...

. Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

and Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

are among later 20th-century composers who admired and were influenced by Mahler. The International Gustav Mahler Society was established in 1955 to honour the composer's life and achievements.

Biography

Early life

Family background

The Mahler family came from eastern

The Mahler family came from eastern Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

, now in the Czech Republic, and were of humble circumstances—the composer's grandmother had been a street pedlar. Bohemia was then part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

; the Mahler family belonged to a German-speaking minority among Bohemians, and was also Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. From this background the future composer developed early on a permanent sense of exile, "always an intruder, never welcomed". The pedlar's son Bernhard Mahler, the composer's father, elevated himself to the ranks of the petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

by becoming a coachman and later an innkeeper.Sadie, p. 505 He bought a modest house in the village of Kaliště (), and in 1857 married Marie Herrmann, the 19-year-old daughter of a local soap manufacturer. In the following year Marie gave birth to the first of the couple's 14 children, a son named Isidor, who died in infancy. Two years later, on 1860, their second son, Gustav, was born.Blaukopf, pp. 18–19

Childhood

In December 1860, Bernhard Mahler moved with his wife and infant son to the city of Jihlava (), where Bernhard built up a successful distillery and tavern business.Franklin, (1. Background, childhood education 1860–80) The family grew rapidly, but of the 12 children born to the family in the city, only six survived infancy. Jihlava was then a thriving commercial city of 20,000 people, in which Gustav was introduced to music through the street songs of the day, through dance tunes, folk melodies and the trumpet calls and marches of the local military band. All of these elements would later contribute to his mature musical vocabulary. When he was four years old, Gustav discovered his grandparents' piano and took to it immediately.Blaukopf, pp. 20–22 He developed his performing skills sufficiently to be considered a local and gave his first public performance at the town theatre when he was ten years old. Although Gustav loved making music, his school reports from the Jihlava portrayed him as absent-minded and unreliable in academic work. In 1871, in the hope of improving the boy's results, his father sent him to the New Town Gymnasium in Prague, but Gustav was unhappy there and soon returned to Jihlava. On 13 April 1875 he suffered a bitter personal loss when his younger brother Ernst (b. 18 March 1862) died after a long illness. Mahler sought to express his feelings in music: with the help of a friend, Josef Steiner, he began work on an opera, ("Duke Ernest of Swabia"), as a memorial to his lost brother. Neither the music nor thelibretto

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to th ...

of this work has survived.

Student days

Bernhard Mahler supported his son's ambitions for a music career, and agreed that the boy should try for a place at the Vienna Conservatory. The young Mahler was auditioned by the renowned pianist Julius Epstein, and accepted for 1875–76. He made good progress in his piano studies with Epstein and won prizes at the end of each of his first two years. For his final year, 1877–78, he concentrated on composition and harmony under Robert Fuchs and Franz Krenn.Sadie, p. 506 Few of Mahler's student compositions have survived; most were abandoned when he became dissatisfied with them. He destroyed a symphonic movement prepared for an end-of-term competition, after its scornful rejection by the autocratic director Joseph Hellmesberger on the grounds of copying errors. Mahler may have gained his first conducting experience with the Conservatory's student orchestra, in rehearsals and performances, although it appears that his main role in this orchestra was as a percussionist. Among Mahler's fellow students at the Conservatory was the future song composerHugo Wolf

Hugo Philipp Jacob Wolf (; ; 13 March 1860 – 22 February 1903) was an Austrian composer, particularly noted for his art songs, or Lieder. He brought to this form a concentrated expressive intensity which was unique in late Romantic music, so ...

, with whom he formed a close friendship. Wolf was unable to submit to the strict disciplines of the Conservatory and was expelled. Mahler, while sometimes rebellious, avoided the same fate only by writing a penitent letter to Hellmesberger.Blaukopf, pp. 30–31 He attended occasional lectures by Anton Bruckner

Joseph Anton Bruckner (; ; 4 September 182411 October 1896) was an Austrian composer and organist best known for his Symphonies by Anton Bruckner, symphonies and sacred music, which includes List of masses by Anton Bruckner, Masses, Te Deum (Br ...

and, though never formally his pupil, was influenced by him. On 16 December 1877, he attended the disastrous premiere of Bruckner's Third Symphony, at which the composer was shouted down, and most of the audience walked out. Mahler and other sympathetic students later prepared a piano version of the symphony, which they presented to Bruckner.Blaukopf, pp. 33–35 Along with many music students of his generation, Mahler fell under the spell of Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, though his chief interest was the sound of the music rather than the staging. It is not known whether he saw any of Wagner's operas during his student years.

Mahler left the conservatory in 1878 with a diploma but without the silver medal given for outstanding achievement.Carr, pp. 23–24 He then enrolled in the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

(he had, at his father's insistence, sat and with difficulty passed the , a highly demanding final exam at a , which was a precondition for university studies) and followed courses which reflected his developing interests in literature and philosophy. After leaving the university in 1879, Mahler made some money as a piano teacher, continued to compose, and in 1880 finished a dramatic cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian language, Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal music, vocal Musical composition, composition with an musical instrument, instrumental accompaniment, ty ...

, ("The Song of Lamentation"). This, his first substantial composition, shows traces of Wagnerian and Brucknerian influences, yet includes many musical elements which musicologist Deryck Cooke describes as "pure Mahler". Its first performance was delayed until 1901, when it was presented in a revised, shortened form.Sadie, p. 527

Mahler developed interests in German philosophy, and was introduced by his friend Siegfried Lipiner

Siegfried Salomo Lipiner (24 October 1856 – 30 December 1911) was a writer and poet from Austria-Hungaryhttps://mahlerfoundation.org/mahler/contemporaries/siegfried-lipiner/ whose works made an impression on Richard Wagner and Friedrich Niet ...

to the works of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

, Gustav Fechner

Gustav Theodor Fechner (; ; 19 April 1801 – 18 November 1887) was a German physicist, philosopher, and experimental psychologist. A pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics (techniques for measuring the mind), he inspi ...

and Hermann Lotze. These thinkers continued to influence Mahler and his music long after his student days were over. Mahler's biographer Jonathan Carr says that the composer's head was "not only full of the sound of Bohemian bands, trumpet calls and marches, Bruckner chorales and Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

sonatas. It was also throbbing with the problems of philosophy and metaphysics he had thrashed out, above all, with Lipiner".Carr, pp. 24–28

Early conducting career 1880–1888

First appointments

From June to August 1880, Mahler took his first professional conducting job, in a small wooden theatre in the spa town of Bad Hall, south ofLinz

Linz (Pronunciation: , ; ) is the capital of Upper Austria and List of cities and towns in Austria, third-largest city in Austria. Located on the river Danube, the city is in the far north of Austria, south of the border with the Czech Repub ...

. The repertory was exclusively operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs and including dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, and length of the work. Apart from its shorter length, the oper ...

; it was, in Carr's words "a dismal little job", which Mahler accepted only after Julius Epstein told him he would soon work his way up. In 1881, he was engaged for six months (September to April) at the Landestheater in Laibach (now Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

, in Slovenia), where the small but resourceful company was prepared to attempt more ambitious works. Here, Mahler conducted his first full-scale opera, Verdi's '' Il trovatore'', one of 10 operas and a number of operettas that he presented during his time in Laibach.Carr, pp. 30–31 After completing this engagement, Mahler returned to Vienna and worked part-time as chorus-master at the Vienna Carltheater.Franklin, (2. Early conducting career, 1880–83).

From the beginning of January 1883, Mahler became conductor at the Royal Municipal Theatre in Olmütz (now Olomouc

Olomouc (; ) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 103,000 inhabitants, making it the Statutory city (Czech Republic), sixth largest city in the country. It is the administrative centre of the Olomouc Region.

Located on the Morava (rive ...

) in Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

. He later wrote: "From the moment I crossed the threshold of the Olmütz theatre I felt like one awaiting the wrath of God."Carr, pp. 32–34 Despite poor relations with the orchestra, Mahler brought nine operas to the theatre, including Bizet's ''Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first performed by the O ...

'', and won over the press that had initially been sceptical of him. After a week's trial at the Royal Theatre in the Hessian town of Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in North Hesse, northern Hesse, in Central Germany (geography), central Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel (region), Kassel and the d ...

, Mahler became the theatre's "Musical and Choral Director" from August 1883. The title concealed the reality that Mahler was subordinate to the theatre's Kapellmeister

( , , ), from German (chapel) and (master), literally "master of the chapel choir", designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term has evolved considerably in i ...

, Wilhelm Treiber, who disliked him (and vice versa) and set out to make his life miserable.Carr, pp. 35–40 Despite the unpleasant atmosphere, Mahler had moments of success at Kassel. He directed a performance of his favourite opera, Weber's ,Sadie, p. 507 and 25 other operas. On 23 June 1884, he conducted his own incidental music to Joseph Victor von Scheffel's play ("The Trumpeter of Säckingen"), the first professional public performance of a Mahler work. An ardent, but ultimately unfulfilled, love affair with soprano Johanna Richter led Mahler to write a series of love poems which became the text of his song cycle ("Songs of a Wayfarer").

In January 1884, the distinguished conductor Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

brought the Meiningen Court Orchestra to Kassel and gave two concerts. Hoping to escape from his job in the theatre, Mahler unsuccessfully sought a post as Bülow's permanent assistant. However, in the following year his efforts to find new employment resulted in a six-year contract with the prestigious Leipzig Opera, to begin in August 1886. Unwilling to remain in Kassel for another year, Mahler resigned on 22 June 1885, and applied for, and through good fortune was offered, a standby appointment as conductor at the Royal in Prague by the theatre's newly appointed director, the famous Angelo Neumann.Franklin, (3. Kassel, 1883–85).

Prague and Leipzig

In Prague, the emergence of the

In Prague, the emergence of the Czech National Revival

The Czech National Revival was a cultural movement which took place in the Czech lands during the 18th and 19th centuries. The purpose of this movement was to revive the Czech Czech language, language, culture and national identity. The most pro ...

had increased the popularity and importance of the new Czech National Theatre, and had led to a downturn in the 's fortunes. Mahler's task was to help arrest this decline by offering high-quality productions of German opera.Franklin, (4. Prague 1885–86 and Leipzig 1886–88). He enjoyed early success presenting works by Mozart and Wagner, composers with whom he would be particularly associated for the rest of his career, but his individualistic and increasingly autocratic conducting style led to friction, and a falling out with his more experienced fellow-conductor, Ludwig Slansky. During his 12 months in Prague he conducted 68 performances of 14 operas (12 titles were new in his repertory), and he also performed Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

's Ninth Symphony for the first time in his life. By the end of the season, in July 1886, Mahler left Prague to take up his post at the in Leipzig, where rivalry with his senior colleague Arthur Nikisch

Arthur Nikisch (12 October 185523 January 1922) was a Hungary, Hungarian conducting, conductor who performed internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, Leipzig and—most importantly—Berlin. He was considered an outstanding interpreter ...

began almost at once. This conflict was primarily over how the two should share conducting duties for the theatre's new production of Wagner's '' Ring'' cycle. Nikisch's illness, from February to April 1887, meant that Mahler took charge of the whole cycle (except ), and scored a resounding public success. This did not, however, win him popularity with the orchestra, who resented his dictatorial manner and heavy rehearsal schedules.

In Leipzig, Mahler befriended Captain (1849–1897), grandson of the composer, and agreed to prepare a performing version of Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber (5 June 1826) was a German composer, conductor, virtuoso pianist, guitarist, and Music criticism, critic in the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Best known for List of operas by Carl Maria von Weber, h ...

's unfinished opera ("The Three Pintos"). Mahler transcribed and orchestrated the existing musical sketches, used parts of other Weber works, and added some composition of his own. The premiere at the Stadttheater, on 20 January 1888, was an important occasion at which several heads of various German opera houses were present. (The Russian composer Tchaikovsky attended the third performance on 29 January.) The work was well-received; its success did much to raise Mahler's public profile, and brought him financial rewards.Carr, pp. 44–47 Mahler's involvement with the Weber family was complicated by Mahler's alleged romantic attachment to Carl von Weber's wife Marion Mathilde (1857–1931) which, though intense on both sides – so it was rumoured by for example English composer Ethel Smyth – ultimately came to nothing. In February and March 1888 Mahler sketched and completed his First Symphony, then in five movements. At around the same time Mahler discovered the German folk-poem collection ("The Youth's Magic Horn"), which would dominate much of his compositional output for the following 12 years.

On 17 May 1888, Mahler suddenly resigned his Leipzig position after a dispute with the 's chief stage manager, Albert Goldberg. However, Mahler had secretly been invited by Angelo Neumann in Prague (and accepted the offer) to conduct the premiere there of "his" , and later also a production of by Peter Cornelius. This short stay (July to September) ended unhappily, with Mahler's dismissal following his outburst during a rehearsal. However, through the efforts of an old Viennese friend, Guido Adler, and cellist David Popper, Mahler's name went forward as a potential director of the Royal Hungarian Opera in Budapest. He was interviewed, made a good impression, and was offered and accepted (with some reluctance) the post from 1 October 1888.

Apprentice composer

In the early years of Mahler's conducting career, composing was a spare time activity. Between his Laibach and Olmütz appointments he worked on settings of verses by Richard Leander and Tirso de Molina, later collected as Volume I of ("Songs and Airs").Cooke, pp. 27–30 Mahler's first orchestral song cycle, , composed at Kassel, was based on his own verses, although the first poem, "" ("When my love becomes a bride") closely follows the text of a poem. The melodies for the second and fourth songs of the cycle were incorporated into the First Symphony, which Mahler finished in 1888, at the height of his relationship with Marion von Weber. The intensity of Mahler's feelings is reflected in the music, which originally was written as a five-movement symphonic poem with a descriptive programme. One of these movements, the "Blumine", later discarded, was based on a passage from his earlier work . After completing the symphony, Mahler composed a 20-minute symphonic poem, "Funeral Rites", which later became the first movement of his Second Symphony.

There has been frequent speculation about lost or destroyed works from Mahler's early years.Franklin, (10. , early songs, First symphony). The Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg believed that the First Symphony was too mature to be a first symphonic work, and must have had predecessors. In 1938, Mengelberg revealed the existence of the so-called "Dresden archive", a series of manuscripts in the possession of the widowed Marion von Weber.Mitchell, Vol II, pp. 51–53 According to the Mahler historian Donald Mitchell, it was highly likely that important Mahler manuscripts of early symphonic works had been held in Dresden; this archive, if it existed, was almost certainly destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

In the early years of Mahler's conducting career, composing was a spare time activity. Between his Laibach and Olmütz appointments he worked on settings of verses by Richard Leander and Tirso de Molina, later collected as Volume I of ("Songs and Airs").Cooke, pp. 27–30 Mahler's first orchestral song cycle, , composed at Kassel, was based on his own verses, although the first poem, "" ("When my love becomes a bride") closely follows the text of a poem. The melodies for the second and fourth songs of the cycle were incorporated into the First Symphony, which Mahler finished in 1888, at the height of his relationship with Marion von Weber. The intensity of Mahler's feelings is reflected in the music, which originally was written as a five-movement symphonic poem with a descriptive programme. One of these movements, the "Blumine", later discarded, was based on a passage from his earlier work . After completing the symphony, Mahler composed a 20-minute symphonic poem, "Funeral Rites", which later became the first movement of his Second Symphony.

There has been frequent speculation about lost or destroyed works from Mahler's early years.Franklin, (10. , early songs, First symphony). The Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg believed that the First Symphony was too mature to be a first symphonic work, and must have had predecessors. In 1938, Mengelberg revealed the existence of the so-called "Dresden archive", a series of manuscripts in the possession of the widowed Marion von Weber.Mitchell, Vol II, pp. 51–53 According to the Mahler historian Donald Mitchell, it was highly likely that important Mahler manuscripts of early symphonic works had been held in Dresden; this archive, if it existed, was almost certainly destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

Budapest and Hamburg, 1888–1897

Royal Opera, Budapest

On arriving in Budapest in October 1888, Mahler encountered a cultural conflict between conservative Hungarian nationalists who favoured a policy of Magyarisation, and progressives who wanted to maintain and develop the country's Austro-German cultural traditions. In the opera house a dominant conservative caucus, led by the music director Sándor Erkel, had maintained a limited repertory of historical and folklore opera. By the time that Mahler began his duties, the progressive camp had gained ascendancy following the appointment of the liberal-minded Ferenc von Beniczky asintendant

An intendant (; ; ) was, and sometimes still is, a public official, especially in France, Spain, Portugal, and Latin America. The intendancy system was a centralizing administrative system developed in France. In the War of the Spanish Success ...

.Franklin, (5. Budapest 1888–91). Aware of the delicate situation, Mahler moved cautiously; he delayed his first appearance on the conductor's stand until January 1889, when he conducted Hungarian-language performances of Wagner's and to initial public acclaim.Sadie, pp. 508–509 However, his early successes faded when plans to stage the remainder of the '' Ring'' cycle and other German operas were frustrated by a renascent conservative faction which favoured a more traditional "Hungarian" programme. In search of non-German operas to extend the repertory, Mahler visited in spring 1890 Italy where among the works he discovered was Mascagni's recent sensation (Budapest premiere on 26 December 1890).

On 18 February 1889, Bernhard Mahler died; this was followed later in the year by the deaths both of Mahler's sister Leopoldine (27 September) and his mother (11 October). From October 1889 Mahler took charge of his four younger brothers and sisters (Alois, Otto, Justine, and Emma). They were installed in a rented flat in Vienna. Mahler himself suffered poor health, with attacks of haemorrhoids and migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

and a recurrent septic throat. Shortly after these family and health setbacks the premiere of the First Symphony, in Budapest on 20 November 1889, was a disappointment. The critic August Beer's lengthy newspaper review indicates that enthusiasm after the early movements degenerated into "audible opposition" after the Finale. Mahler was particularly distressed by the negative comments from his Vienna Conservatory contemporary, Viktor von Herzfeld, who had remarked that Mahler, like many conductors before him, had proved not to be a composer.

In 1891, Hungary's move to the political right was reflected in the opera house when Beniczky on 1 February was replaced as intendant by Count Géza Zichy, a conservative aristocrat determined to assume artistic control over Mahler's head. However, Mahler had foreseen that and had secretly been negotiating with Bernhard Pollini, the director of the Stadttheater Hamburg since summer and autumn of 1890, and a contract was finally signed in secrecy on 15 January 1891. Mahler more or less "forced" himself to be sacked from his Budapest post, and he succeeded on 14 March 1891. By his departure he received a large sum of indemnity. One of his final Budapest triumphs was a performance of Mozart's (16 September 1890) which won him praise from Brahms, who was present at the performances on 16 December 1890. During his Budapest years Mahler's compositional output had been limited to a few songs from the song settings that became Volumes II and III of , and amendments to the First Symphony.

Stadttheater Hamburg

Mahler's Hamburg post was as chief conductor, subordinate to the director, Bernhard Pohl (known as Pollini) who retained overall artistic control. Pollini was prepared to give Mahler considerable leeway if the conductor could provide commercial as well as artistic success. This Mahler did in his first season, when he conducted Wagner's for the first time and gave acclaimed performances of the same composer's and .Franklin, (6. Hamburg 1891–97). Another triumph was the German premiere of Tchaikovsky's ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

'', in the presence of the composer, who called Mahler's conducting "astounding", and later asserted in a letter that he believed Mahler was "positively a genius". Mahler's demanding rehearsal schedules led to predictable resentment from the singers and orchestra in whom, according to music writer Peter Franklin, the conductor "inspired hatred and respect in almost equal measure". He found support, however, from Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

, who was in Hamburg as director of the city's subscription concerts. Bülow, who had spurned Mahler's approaches in Kassel, had come to admire the younger man's conducting style, and on Bülow's death in 1894 Mahler took over the direction of the concerts.

In the summer of 1892 Mahler took the Hamburg singers to London to participate in an eight-week season of German opera—his only visit to Britain. His conducting of ''Tristan'' enthralled the young composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who "staggered home in a daze and could not sleep for two nights." However, Mahler refused further such invitations as he was anxious to reserve his summers for composing. In 1893 he acquired a retreat at Steinbach, on the banks of Lake Attersee in Upper Austria, and established a pattern that persisted for the rest of his life; summers would henceforth be dedicated to composition, at Steinbach or its successor retreats. Now firmly under the influence of the folk-poem collection, Mahler produced a stream of song settings at Steinbach, and composed his Second and Third Symphonies there.

Performances of Mahler works were still comparatively rare (he had not composed very much). On 27 October 1893, at Hamburg's Konzerthaus Ludwig, Mahler conducted a revised version of his First Symphony; still in its original five-movement form, it was presented as a (

In the summer of 1892 Mahler took the Hamburg singers to London to participate in an eight-week season of German opera—his only visit to Britain. His conducting of ''Tristan'' enthralled the young composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who "staggered home in a daze and could not sleep for two nights." However, Mahler refused further such invitations as he was anxious to reserve his summers for composing. In 1893 he acquired a retreat at Steinbach, on the banks of Lake Attersee in Upper Austria, and established a pattern that persisted for the rest of his life; summers would henceforth be dedicated to composition, at Steinbach or its successor retreats. Now firmly under the influence of the folk-poem collection, Mahler produced a stream of song settings at Steinbach, and composed his Second and Third Symphonies there.

Performances of Mahler works were still comparatively rare (he had not composed very much). On 27 October 1893, at Hamburg's Konzerthaus Ludwig, Mahler conducted a revised version of his First Symphony; still in its original five-movement form, it was presented as a (tone poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement (music), movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. T ...

) under the descriptive name "Titan". This concert also introduced six recent settings. Mahler achieved his first relative success as a composer when the Second Symphony was well-received on its premiere in Berlin, under his own baton, on 13 December 1895. Mahler's conducting assistant Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a Germany, German-born Conducting, conductor, pianist, and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French people, French cit ...

, who was present, said that "one may date ahler'srise to fame as a composer from that day." That same year Mahler's private life had been disrupted by the suicide of his younger brother Otto on 6 February.

At the Stadttheater Mahler's repertory consisted of 66 operas of which 36 titles were new to him. During his six years in Hamburg, he conducted 744 performances, including the debuts of Verdi's '' Falstaff'', Humperdinck's '' Hänsel und Gretel'', and works by Smetana. However, he was forced to resign his post with the subscription concerts after poor financial returns and an ill-received interpretation of his re-scored Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Already at an early age Mahler had made it clear that his ultimate goal was an appointment in Vienna, and from 1895 onward was manoeuvring, with the help of influential friends, to secure the directorship of the Vienna Hofoper. He overcame the bar that existed against the appointment of a Jew to this post by what may have been a pragmatic conversion to Catholicism in February 1897. Despite this event, Mahler has been described as a lifelong agnostic.

Vienna, 1897–1907

Hofoper director

As he waited for theEmperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

's confirmation of his directorship, Mahler shared duties as a resident conductor with Joseph Hellmesberger Jr. (son of the former conservatory director) and Hans Richter, an internationally renowned interpreter of Wagner and the conductor of the original ''Ring'' cycle at Bayreuth

Bayreuth ( or ; High Franconian German, Upper Franconian: Bareid, ) is a Town#Germany, town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtel Mountains. The town's roots date back to 11 ...

in 1876. Director Wilhelm Jahn

Wilhelm Jahn (24 November 1835 in Dvorce – 21 April 1900 in Vienna) was an Austrian conductor.

Life

Jahn served as director of the Vienna Court Opera from 1880 to 1897 and principal conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra from 1882 ...

had not consulted Richter about Mahler's appointment; Mahler, sensitive to the situation, wrote Richter a complimentary letter expressing unswerving admiration for the older conductor. Subsequently, the two were rarely in agreement, but kept their divisions private.

Vienna, the imperial Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

capital, had recently elected an anti-Semitic conservative mayor, Karl Lueger, who had once proclaimed: "I myself decide who is a Jew and who isn't." In such a volatile political atmosphere Mahler needed an early demonstration of his German cultural credentials. He made his initial mark in May 1897 with much-praised performances of Wagner's '' Lohengrin'' and Mozart's .Franklin (7. Vienna 1897–1907) Shortly after the triumph, Mahler was forced to take sick leave for several weeks, during which he was nursed by his sister Justine and his long-time companion, the viola player Natalie Bauer-Lechner.La Grange, Vol 2 pp. 32–36 Mahler returned to Vienna in late July to prepare for Vienna's first uncut version of the ''Ring'' cycle. This performance took place on 24–27 August, attracting critical praise and public enthusiasm. Mahler's friend Hugo Wolf told Bauer-Lechner that "for the first time I have heard the ''Ring'' as I have always dreamed of hearing it while reading the score".

On 8 October Mahler was formally appointed to succeed Jahn as the Hofoper's director. His first production in his new office was Smetana's Czech nationalist opera '' Dalibor'', with a reconstituted finale that left the hero Dalibor alive. This production caused anger among the more extreme Viennese German nationalists, who accused Mahler of "fraternising with the anti-dynastic, inferior Czech nation." The Austrian author Stefan Zweig, in his memoirs '' The World of Yesterday'' (1942), described Mahler's appointment as an example of the Viennese public's general distrust of young artists: "Once, when an amazing exception occurred and Gustav Mahler was named director of the Court Opera at thirty-eight years old, a frightened murmur and astonishment ran through Vienna, because someone had entrusted the highest institute of art to 'such a young person' ... This suspicion—that all young people were 'not very reliable'—ran through all circles at that time." Zweig also wrote that "to have seen Gustav Mahler on the street n Viennawas an event that one would proudly report to his comrades the next morning as it if were a personal triumph." During Mahler's tenure a total of 33 new operas were introduced to the Hofoper; a further 55 were new or totally revamped productions.La Grange, Vol. 3, pp. 941–944 However, a proposal to stage

On 8 October Mahler was formally appointed to succeed Jahn as the Hofoper's director. His first production in his new office was Smetana's Czech nationalist opera '' Dalibor'', with a reconstituted finale that left the hero Dalibor alive. This production caused anger among the more extreme Viennese German nationalists, who accused Mahler of "fraternising with the anti-dynastic, inferior Czech nation." The Austrian author Stefan Zweig, in his memoirs '' The World of Yesterday'' (1942), described Mahler's appointment as an example of the Viennese public's general distrust of young artists: "Once, when an amazing exception occurred and Gustav Mahler was named director of the Court Opera at thirty-eight years old, a frightened murmur and astonishment ran through Vienna, because someone had entrusted the highest institute of art to 'such a young person' ... This suspicion—that all young people were 'not very reliable'—ran through all circles at that time." Zweig also wrote that "to have seen Gustav Mahler on the street n Viennawas an event that one would proudly report to his comrades the next morning as it if were a personal triumph." During Mahler's tenure a total of 33 new operas were introduced to the Hofoper; a further 55 were new or totally revamped productions.La Grange, Vol. 3, pp. 941–944 However, a proposal to stage Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; ; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer and conductor best known for his Tone poems (Strauss), tone poems and List of operas by Richard Strauss, operas. Considered a leading composer of the late Roman ...

's controversial opera ''Salome

Salome (; , related to , "peace"; ), also known as Salome III, was a Jews, Jewish princess, the daughter of Herod II and princess Herodias. She was granddaughter of Herod the Great and stepdaughter of Herod Antipas. She is known from the New T ...

'' in 1905 was rejected by the Viennese censors.

Early in 1902 Mahler met Alfred Roller, an artist and designer associated with the Vienna Secession movement. A year later, Mahler appointed him chief stage designer to the Hofoper, where Roller's debut was a new production of . The collaboration between Mahler and Roller created more than 20 celebrated productions of, among other operas, Beethoven's ''Fidelio

''Fidelio'' (; ), originally titled ' (''Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love''), Opus number, Op. 72, is the sole opera by German composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of ...

'', Gluck's ''Iphigénie en Aulide

''Iphigénie en Aulide'' (''Iphigeneia in Aulis (ancient Greece), Aulis'') is an opera in three acts by Christoph Willibald Gluck, the first work he wrote for the Paris stage. The libretto was written by François-Louis Gand Le Bland Du Roullet ...

'' and Mozart's .Sadie, pp. 510–511 In the ''Figaro'' production, Mahler offended some purists by adding and composing a short recitative scene to Act III.

In spite of numerous theatrical triumphs, Mahler's Vienna years were rarely smooth; his battles with singers and the house administration continued on and off for the whole of his tenure. While Mahler's methods improved standards, his histrionic and dictatorial conducting style was resented by orchestra members and singers alike. In December 1903 Mahler faced a revolt by stagehands, whose demands for better conditions he rejected in the belief that extremists were manipulating his staff. The anti-Semitic elements in Viennese society, long opposed to Mahler's appointment, continued to attack him relentlessly, and in 1907 instituted a press campaign designed to drive him out.Carr, pp. 150–151 By that time he was at odds with the opera house's administration over the amount of time he was spending on his own music, and was preparing to leave. In May 1907 he began discussions with Heinrich Conried, director of the New York

In spite of numerous theatrical triumphs, Mahler's Vienna years were rarely smooth; his battles with singers and the house administration continued on and off for the whole of his tenure. While Mahler's methods improved standards, his histrionic and dictatorial conducting style was resented by orchestra members and singers alike. In December 1903 Mahler faced a revolt by stagehands, whose demands for better conditions he rejected in the belief that extremists were manipulating his staff. The anti-Semitic elements in Viennese society, long opposed to Mahler's appointment, continued to attack him relentlessly, and in 1907 instituted a press campaign designed to drive him out.Carr, pp. 150–151 By that time he was at odds with the opera house's administration over the amount of time he was spending on his own music, and was preparing to leave. In May 1907 he began discussions with Heinrich Conried, director of the New York Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera is an American opera company based in New York City, currently resident at the Metropolitan Opera House (Lincoln Center), Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Referred ...

, and on 21 June signed a contract, on very favourable terms, for four seasons' conducting in New York. At the end of the summer he submitted his resignation to the Hofoper, and on 15 October 1907 conducted ''Fidelio'', his 645th and final performance there. During his ten years in Vienna, Mahler had brought new life to the opera house and cleared its debts, but had won few friends—it was said that he treated his musicians in the way a lion tamer treated his animals. His departing message to the company, which he pinned to a notice board, was later torn down and scattered over the floor. After conducting the Hofoper orchestra in a farewell concert performance of his Second Symphony on 24 November, Mahler left Vienna for New York in early December.Sadie, pp. 512–13Carr, pp. 154–155

Philharmonic concerts

When Richter resigned as head of the Vienna Philharmonic subscription concerts in September 1898, the concerts committee had unanimously chosen Mahler as his successor. The appointment was not universally welcomed; the anti-Semitic press wondered if, as a non-German, Mahler would be capable of defending German music.La Grange, Vol. 2, p. 117 Attendances rose sharply in Mahler's first season, but members of the orchestra were particularly resentful of his habit of re-scoring acknowledged masterpieces, and of his scheduling of extra rehearsals for works with which they were thoroughly familiar. An attempt by the orchestra to have Richter reinstated for the 1899 season failed, because Richter was not interested. Mahler's position was weakened when, in 1900, he took the orchestra to Paris to play at the Exposition Universelle. The Paris concerts were poorly attended and lost money—Mahler had to borrow the orchestra's fare home from the Rothschilds.Carr, pp. 87–94 In April 1901, dogged by a recurrence of ill-health and wearied by more complaints from the orchestra, Mahler relinquished the Philharmonic concerts conductorship. In his three seasons he had performed around 80 different works, which included pieces by relatively unknown composers such as Hermann Goetz, Wilhelm Kienzl and the ItalianLorenzo Perosi

Monsignor Lorenzo Perosi (21 December 1872 – 12 October 1956) was an Italian composer of sacred music and the only member of the Giovane Scuola who did not write opera. In the late 1890s, while he was still only in his twenties, Perosi was a ...

.

Mature composer

The demands of his twin appointments in Vienna initially absorbed all Mahler's time and energy, but by 1899 he had resumed composing. The remaining Vienna years were to prove particularly fruitful. While working on some of the last of his settings he started his Fourth Symphony, which he completed in 1900. By this time he had abandoned the composing hut at Steinbach and had acquired another, at Maiernigg on the shores of the Wörthersee in

The demands of his twin appointments in Vienna initially absorbed all Mahler's time and energy, but by 1899 he had resumed composing. The remaining Vienna years were to prove particularly fruitful. While working on some of the last of his settings he started his Fourth Symphony, which he completed in 1900. By this time he had abandoned the composing hut at Steinbach and had acquired another, at Maiernigg on the shores of the Wörthersee in Carinthia

Carinthia ( ; ; ) is the southernmost and least densely populated States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The Lake Wolayer is a mountain lake on the Carinthian side of the Carnic Main ...

, where he later built a villa. In this new venue Mahler embarked upon what is generally considered as his "middle" or post- compositional period.Cooke, pp. 71–94 Between 1901 and 1904 he wrote ten settings of poems by Friedrich Rückert

Johann Michael Friedrich Rückert (16 May 1788 – 31 January 1866) was a German poet, translation, translator, and professor of Oriental languages.

Biography

Johann Michael Friedrich Rückert was born 16 May 1788 in Schweinfurt and was the e ...

, five of which were collected as . The other five formed the song cycle ("Songs on the Death of Children"). The trilogy of orchestral symphonies, the Fifth, the Sixth and the Seventh were composed at Maiernigg between 1901 and 1905, and the Eighth Symphony written there in 1906, in eight weeks of furious activity.

Within this same period Mahler's works began to be performed with increasing frequency. In April 1899 he conducted the Viennese premiere of his Second Symphony; 17 February 1901 saw the first public performance of his early work , in a revised two-part form. Later that year, in November, Mahler conducted the premiere of his Fourth Symphony, in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, and was on the rostrum for the first complete performance of the Third Symphony, at the festival at Krefeld

Krefeld ( , ; ), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War), is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, in western Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldorf, its c ...

on 9 June 1902. Mahler "first nights" now became increasingly frequent musical events; he conducted the first performances of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies at Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

and Essen