Macedonization on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Macedonian nationalism (, ) is a general grouping of

Macedonian nationalism (, ) is a general grouping of

During the first half of the

During the first half of the

In the 19th century, the region of Macedonia became the object of competition by rival nationalisms, initially

In the 19th century, the region of Macedonia became the object of competition by rival nationalisms, initially

On September 8, 1991, the

On September 8, 1991, the

Macedonism, sometimes referred to as Macedonianism ( Macedonian and Serbian: Македонизам, ''Makedonizam''; bg, Македонизъм, ''Makedonizam'' and

Macedonism, sometimes referred to as Macedonianism ( Macedonian and Serbian: Македонизам, ''Makedonizam''; bg, Македонизъм, ''Makedonizam'' and

, ''Macedonianism FYROM'S Expansionist Designs against Greece, 1944–2006'', Ephesus - Society for Macedonian Studies, 2007 , Retrieved on 2007-12-05. Before the

Among the views and opinions that are often perceived as representative of Macedonian nationalism and criticised as parts of "Macedonism" by those who use the term are the following:

*The notion of unbroken racial, linguistic and cultural continuity between the modern ethnic Macedonians and a part of the ancient autochthonous peoples of the region, in particular the

Among the views and opinions that are often perceived as representative of Macedonian nationalism and criticised as parts of "Macedonism" by those who use the term are the following:

*The notion of unbroken racial, linguistic and cultural continuity between the modern ethnic Macedonians and a part of the ancient autochthonous peoples of the region, in particular the

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

ideas and concepts among ethnic Macedonians that were first formed in the late 19th century among separatists seeking the autonomy of the region of Macedonia from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The idea evolved during the early 20th century alongside the first expressions of ethnic nationalism among the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

of Macedonia. The separate Macedonian nation gained recognition after World War II when the "Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалистичка Република Македонија, Socijalistička Republika Makedonija), or SR Macedonia, commonly referred to as Socialist Macedonia or Yugoslav Macedonia, was ...

" was created as part of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

. Afterwards the Macedonian historiography

Historiography in North Macedonia is the methodology of historical studies used by the historians of that country. It has been developed since 1945 when SR Macedonia became part of Yugoslavia. According to the German historian it has preserve ...

has established historical links between the ethnic Macedonians and events and Bulgarian figures from the Middle Ages up to the 20th century. Following the independence of the Republic of Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Yugoslavia. It ...

in the late 20th century, issues of Macedonian national identity have become contested by the country's neighbours, as some adherents to aggressive Macedonian nationalism, called ''Macedonism'', hold more extreme beliefs such as an unbroken continuity between ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

(essentially an ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

people

A person (plural, : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of pr ...

), and modern ethnic Macedonians (a Slavic people), and views connected to the irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

concept of a United Macedonia

United Macedonia ( mk, Обединета Македонија, ''Obedineta Makedonija''), or Greater Macedonia (, ''Golema Makedonija''), is an irredentist concept among ethnic Macedonian nationalists that aims to unify the transnational regio ...

, which involves territorial claims on a large portion of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, along with smaller regions of Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

.

The designation “Macedonian”

During the first half of the

During the first half of the second millennium

File:2nd millennium montage.png, From top left, clockwise: in 1492, Christopher Columbus reaches North America, opening the European colonization of the Americas; the American Revolution, one of the late 1700s Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment-i ...

, the concept of Macedonia on the Balkans was associated by the Byzantines with their Macedonian province, centered around Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

in modern-day Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. After the conquest of the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

by the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in the late 14th and early 15th century, the Greek name ''Macedonia'' disappeared as a geographical designation for several centuries. The background of the modern designation ''Macedonian'' can be found in the 19th century, as well as the myth of "ancient Macedonian descent" among the Orthodox Slavs in the area, adopted mainly due to Greek cultural inputs. However Greek education was not the only engine for such ideas. At that time some pan-Slavic

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

propagandists believed the early Slavs

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the S ...

were related to the paleo-Balkan tribes. Under these influences some intellectuals in the region developed the idea on direct link between the local Slavs, the Early Slavs and the ancient Balkan populations.

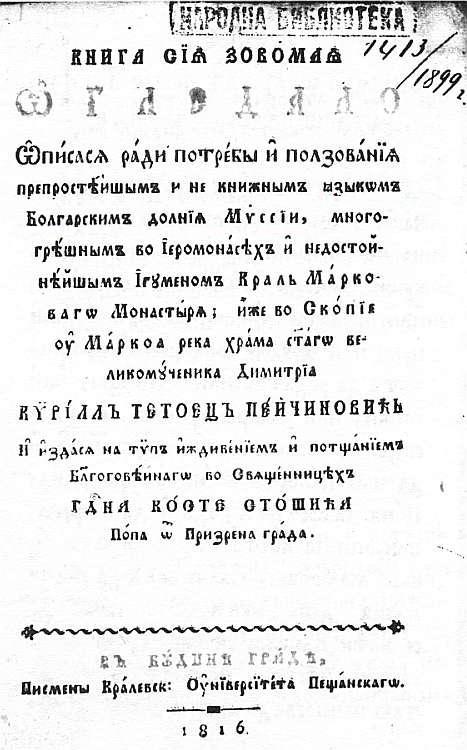

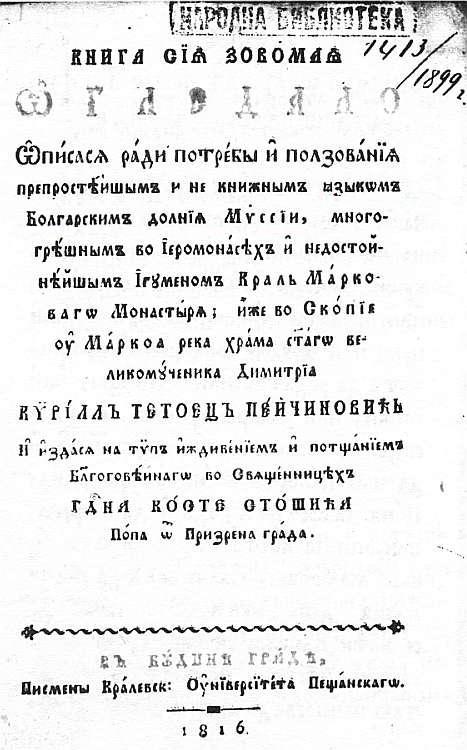

In Ottoman times names as "Lower Bulgaria" and "Lower Moesia" were used by the local Slavs to designate most of the territory of today's geographical region of Macedonia and the names ''Bulgaria'' and ''Moesia'' were identified with each other. Self-identifying as "Bulgarian" on account of their language, the local Slavs considered themselves as "Rum", i.e. members of the community of Orthodox Christians. This community was a source of identity for all the ethnic groups inside it and most people identified mostly with it. Until the middle of the 19th century, the Greeks also called the Slavs in Macedonia "Bulgarians", and regarded them predominantly as Orthodox brethren, but the rise of Bulgarian nationalism

Bulgarian irredentism is a term to identify the territory associated with a historical national state and a modern Bulgarian irredentist nationalist movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, which would include most of Macedonia, Thrace and ...

changed the Greek position. At that time the Orthodox Christian community began to degrade with the continuous identification of the religious creed with ethnic identity, while Bulgarian national activists started a debate on the establishment of their separate Orthodox church.

As a result, massive Greek religious and school propaganda occurred, and a process of ''Hellenization'' was implemented among the Slavic-speaking population of the area. The very name ''Macedonia,'' revived during the early 19th century after the foundation of the modern Greek state, with its Western Europe-derived obsession with Ancient Greece, was applied to the local Slavs.Jelavich Barbara, History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century, 1983, Cambridge University Press, , p. 91. The idea was to stimulate the development of close ties between them and the Greeks, linking both sides to the ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

, as a counteract against the growing Bulgarian cultural influence into the region.J. Pettifer, The New Macedonian Question, St Antony's group, Springer, 1999, , pp. 49–51. In 1845, for instance, the Alexander romance was published in Slavic Macedonian dialect typed with Greek letters. At the same time the Russian ethnographer Victor Grigorovich

Victor Ivanovich Grigorovich (russian: link=no, Ви́ктор Ива́нович Григоро́вич; 30 April 1815 – 19 December 1876) was a Russian Slavist, folklorist, literary critic, historian and journalist, one of the originators of ...

described a recent change in the title of the Greek Patriarchist bishop of Bitola: from ''Exarch of all Bulgaria'' to ''Exarch of all Macedonia''. He also noted the unusual popularity of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

and that it appeared to be something that was recently instilled on the local Slavs.

As a consequence, since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the designation ''Macedonian'' as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity. In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov

Petko Rachov Slaveykov ( bg, Петко Рачов Славейков) (17 November 1827 OS – 1 July 1895 OS ) was a Bulgarian poet, publicist, politician and folklorist.

Biography Early years and educational activity

Slaveykov was born in ...

, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

, but they are rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

. In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov

Petko Rachov Slaveykov ( bg, Петко Рачов Славейков) (17 November 1827 OS – 1 July 1895 OS ) was a Bulgarian poet, publicist, politician and folklorist.

Biography Early years and educational activity

Slaveykov was born in ...

reports that discontent with the current situation “has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their own local dialect and what’s more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership.” Nevertheless, other Macedonian intellectuals as Miladinov Brothers

The Miladinov brothers ( bg, Братя Миладинови, ''Bratya Miladinovi'', mk, Браќа Миладиновци, ''Brakja Miladinovci''), Dimitar Miladinov (1810–1862) and Konstantin Miladinov (1830–1862), were Bulgarian poets ...

, continued to call their land ''Western'' Bulgaria and worried that use of the new name would imply identification with the Greek nation.

However, per Kuzman Shapkarev

Kuzman Anastasov Shapkarev, ( bg, Кузман Анастасов Шапкарев), (1 January 1834 in Ohrid – 18 March 1909 in Sofia) was a Bulgarian folklorist, ethnographer and scientist from the Ottoman region of Macedonia, author of te ...

, as a result of ''Macedonists activity, in the 1870s the ancient ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

''Macedonians'' was imposed on the local Slavs, and began to replace the traditional one ''Bulgarians''.In a letter to Prof. Marin Drinov

Marin Stoyanov Drinov ( bg, Марин Стоянов Дринов, russian: Марин Степанович Дринов; 20 October 1838 - 13 March 1906) was a Bulgarian historian and philologist from the National Revival period who lived and ...

of May 25, 1888 Kuzman Shapkarev writes: "But even stranger is the name Macedonians, which was imposed on us only 10–15 years ago by outsiders, and not as some think by our own intellectuals.... Yet the people in Macedonia know nothing of that ancient name, reintroduced today with a cunning aim on the one hand and a stupid one on the other. They know the older word: "Bugari", although mispronounced: they have even adopted it as peculiarly theirs, inapplicable to other Bulgarians. You can find more about this in the introduction to the booklets I am sending you. They call their own Macedono-Bulgarian dialect the "Bugarski language", while the rest of the Bulgarian dialects they refer to as the "Shopski language". (Makedonski pregled, IX, 2, 1934, p. 55; the original letter is kept in the Marin Drinov Museum in Sofia, and it is available for examination and study) During the 1880s, after recommendation by Stojan Novaković

Stojan Novaković ( sr-Cyrl, Стојан Новаковић; 1 November 1842 – 18 February 1915) was a Serbian politician, historian, diplomat, writer, bibliographer, literary critic, literary historian, and translator. He held the post ...

, the Serbian government also began to support those ideas to counteract the Bulgarian influence in Macedonia, claiming the Macedonian Slavs were in fact ''pure Slavs'' (i.e. Serbian Macedonians), while the Bulgarians, unlike them, were partially a mixture of Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

and Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

(i.e. Tatars). In accordance with Novaković's agenda this Serbian "Macedonism" was transformed in the 1890s, in a process of the gradual Serbianisation

Serbianisation or Serbianization, also known as Serbification, and Serbisation or Serbization ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", srbizacija, србизација or sh-Latn-Cyrl, label=none, separator=" / ", posrbljavanje, посрбљавање; ...

of the Macedonian Slavs.

By the end of the 19th century, according to Vasil Kanchov

Vasil Kanchov ( bg, Васил Кънчов, Vasil Kanchov) (26 July 1862 – 6 February 1902) was a Bulgarian geographer, ethnographer and politician.

Biography

Vasil Kanchov was born in Vratsa. Upon graduating from High school in Lom, ...

the local Bulgarians called themselves Macedonians, and the surrounding nations called them Macedonians. In the early 20th century Pavel Shatev

Pavel Potsev Shatev ( Bulgarian and mk, Павел Поцев Шатев) (July 15, 1882 – January 30, 1951) was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary and member of the left wing of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization ...

, witnessed this process of slow differentiation, describing people who insisted on their Bulgarian nationality, but felt themselves Macedonians above all. However a similar paradox was observed at the eve of the 20th century and afterwards, when many Bulgarians from non-Macedonian descent, involved in the Macedonian affairs, espoused ''Macedonian identity'', and that idea undoubtedly was emancipated from the '' pan-Bulgarian'' national project. During the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

Bulgaria also supported to some extent the Macedonian ''regionalism'', especially in the Kingdom Yugoslavia, to prevent the final Serbianization

Serbianisation American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), or Serbianization, also known as Serbification, and Serbisation American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), or ...

of the local Slavs, because the very name ''Macedonia'' was prohibited there. Ultimately the designation Macedonian, changed its status in 1944, and went from being predominantly a regional, ethnographic denomination, to a national one. However, when the anthropologist Keith Brown visited the Republic of Macedonia at the eve of the 21st century, he discovered that the local Aromanians

The Aromanians ( rup, Armãnji, Rrãmãnji) are an Ethnic groups in Europe, ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian language, Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Alba ...

, who also call themselves ''Macedonians'', still label "Bulgarians" the ethnic Macedonians, and their eastern neighbours.

Origins

Greek nationalists

Greek nationalism (or Hellenic nationalism) refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.. As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in pre-modern times. It became a major political movement beginning in the 18th century, ...

, Serbian nationalists

Serbian nationalism asserts that Serbs are a nation and promotes the cultural and political unity of Serbs. It is an ethnic nationalism, originally arising in the context of the general rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule, und ...

and Bulgarian nationalists

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

that each made claims about the Slavic-speaking population as being ethnically linked to their nation and thus asserted the right to seek their integration.Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. ''Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies''. 2013. p. 318. The first assertions of Macedonian nationalism arose in the late 19th century. Early Macedonian nationalists were encouraged by several foreign governments that held interests in the region. The Serbian government came to believe that any attempt to forcibly assimilate Slavic Macedonians into Serbs in order to incorporate Macedonia would be unsuccessful, given the strong Bulgarian influence in the region. Instead, the Serbian government believed that providing support to Macedonian nationalists would stimulate opposition to incorporation into Bulgaria and favourable attitudes to Serbia. Another country that encouraged Macedonian nationalism was Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

that sought to deny both Serbia and Bulgaria the ability to annex Macedonia, and asserted a distinct ethnic character of Slavic Macedonians. In the 1890s, Russian supporters of a Slavic Macedonian ethnicity emerged, Russian-made ethnic maps began showing a Slavic Macedonian ethnicity, and Macedonian nationalists began to move to Russia to mobilize.

The origins of the definition of an ethnic Slav Macedonian identity arose from the writings of Georgi Pulevski

Georgi Pulevski, sometimes also Gjorgji, Gjorgjija Pulevski or Đorđe Puljevski ( mk, Ѓорѓи Пулевски or Ѓорѓија Пулевски, bg, Георги Пулевски, sr, Ђорђе Пуљевски; 1817–1895) was a Mija ...

in the 1870s and 1880s, who identified the existence of a distinct modern "Slavic Macedonian" language that he defined as different from the other languages in that it had linguistic elements from Serbian, Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

, Church Slavonic

Church Slavonic (, , literally "Church-Slavonic language"), also known as Church Slavic, New Church Slavonic or New Church Slavic, is the conservative Slavic liturgical language used by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus, Bosnia and Herzeg ...

, and Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

.Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. ''Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies''. BRILL, 2013. p. 300. Pulevski analyzed the folk histories of the Slavic Macedonian people, in which he concluded that Slavic Macedonians were ethnically linked to the people of the ancient Kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

of Philip and Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

based on the claim that the ancient Macedonian language had Slavic components in it and thus the ancient Macedonians were Slavic, and modern-day Slavic Macedonians were their descendants.Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. ''Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies''. BRILL, 2013. p. 316. However, Slavic Macedonians' self-identification and nationalist loyalties remained ambiguous in the late 19th century. Pulevski for instance viewed Macedonians' identity as being a regional phenomenon (similar to Herzegovinians

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geograp ...

and Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

). Once calling himself a "Serbian patriot", another time a "Bulgarian from the village of Galicnik", he also identified the Slavic Macedonian language as being related to the "Old Bulgarian language" as well as being a "Serbo-Albanian language". Pulevski's numerous identifications reveal the absence of a clear ethnic sense in a part of the local Slavic population.

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; bg, Вътрешна Македонска Революционна Организация (ВМРО), translit=Vatrešna Makedonska Revoljucionna Organizacija (VMRO); mk, Внатр� ...

(IMRO) grew up as the major Macedonian separatist organization in the 1890s, seeking the autonomy of Macedonia from the Ottoman Empire.Viktor Meier. Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise. p. 179. The IMRO initially opposed being dependent on any of the neighbouring states, especially Greece and Serbia, however its relationship with Bulgaria grew very strong, and it soon became dominated by figures who supported the annexation of Macedonia into Bulgaria, though a small fraction opposed this. As a rule, the IMRO members had Bulgarian national self-identification, but the autonomist faction stimulated the development of Macedonian nationalism. It devised the slogan "Macedonia for the Macedonians" and called for a supranational Macedonia, consisting of different nationalities and eventually included in a future Balkan Federation

The Balkan Federation project was a left-wing political movement to create a country in the Balkans by combining Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

The concept of a Balkan federation emerged in the late 19th century from ...

. However, the promoters of this slogan declared their conviction that the majority of the Macedonian Christian Slav population was Bulgarian.

In the late 19th and early 20th century the international community viewed the Macedonians predominantly as a regional variety of the Bulgarians. At the end of the First World War there were very few ethnographers who agreed that a separate Macedonian nation existed. During the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the Allies sanctioned Serbian control of Vardar Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia ( Macedonian and sr, Вардарска Македонија, ''Vardarska Makedonija'') was the name given to the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia (1912–1918) and Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941) roughly corresponding to t ...

The term "Vardar Macedonia" is a geographic term which refers to the portion of the region of Macedonia

Macedonia () is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time; however, it came to be defined as the modern geographical region by the mid 19th century. T ...

currently occupied by the Republic of Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Yugoslavia. It ...

. and accepted the belief that Macedonian Slavs were in fact Southern Serbs. This change in opinion can largely be attributed to the Serbian geographer Jovan Cvijić

Jovan Cvijić ( sr-cyr, Јован Цвијић, ; 1865 – 16 January 1927) was a Serbian geographer and ethnologist, president of the Serbian Royal Academy of Sciences and rector of the University of Belgrade. Cvijić is considered the ...

. Nevertheless, Macedonist ideas increased during the interbellum

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relativel ...

in Yugoslav Vardar Macedonia and among the left diaspora in Bulgaria, and were supported by the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Macedonist ideas were further developed by the Yugoslav Communist Partisans, but some researchers doubt that even at that time the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be ethnically separate from the Bulgarians. The turning point for the Macedonian ethnogenesis was the creation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалистичка Република Македонија, Socijalistička Republika Makedonija), or SR Macedonia, commonly referred to as Socialist Macedonia or Yugoslav Macedonia, was ...

as part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

following World War II.

History

Early and middle 19th century

With the conquest of the Balkans by theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in the late 14th century, the name of Macedonia disappeared for several centuries and was rarely displayed on geographic maps. It was rediscovered during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

by western researchers, who introduced ancient Greek geographical names in their work, although used in a rather loose manner. The modern region was not labeled "Macedonia" by the Ottomans. The name "Macedonia" gained popularity parallel to the ascendance of rival nationalism. The central and northern areas of modern Macedonia were often called "Bulgaria" or "Lower Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alb ...

" during Ottoman rule. The name "Macedonia" was revived to mean a separate geographical region on the Balkans, this occurring in the early 19th century, after the foundation of the modern Greek state, with its Western Europe-derived obsession with the Ancient world. However, as a result of the massive Greek religious and school propaganda, a kind of ''Macedonization'' occurred among the Greek and non-Greek speaking population of the area. The name ''Macedonian Slavs'' was also introduced by the Greek clergy and teachers among the local Slavophones with an aim to stimulate the development of close ties between them and the Greeks, linking both sides to the ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

, as a counteract against the growing Bulgarian influence there.

Late 19th and early 20th century

The first attempts for creation of the Macedonianethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

Throughout this article, the term "Macedonian" will refer to ethnic Macedonians. There are many other uses of the term, and comprehensive coverage of this topic may be found in the article Macedonia (terminology)

The name ''Macedonia'' is used in a number of competing or overlapping meanings to describe geographical, political and historical areas, languages and peoples in a part of south-eastern Europe. It has been a major source of political controver ...

. can be said to have begun in the late 19th and early 20th century.Danforth, L. (1995) ''The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World'' This was the time of the first expressions of Macedonism

Macedonian nationalism (, ) is a general grouping of Nationalism, nationalist ideas and concepts among ethnic Macedonians (ethnic group), Macedonians that were first formed in the late 19th century among separatists seeking the autonomy of the r ...

by limited groups of intellectuals in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

, Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and ha ...

, Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

and St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. However, up until the 20th century and beyond, the majority of the Slavic-speaking population of the region was identified as Macedono-Bulgarian or simply as Bulgarian and after 1870 joined the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate ( bg, Българска екзархия, Balgarska ekzarhiya; tr, Bulgar Eksarhlığı) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and th ...

. Although he was appointed Bulgarian metropolitan bishop, in 1891 Theodosius of Skopje

Theodosius of Skopje ( bg, Теодосий Скопски, mk, Теодосиј Гологанов; 1846–1926) was a Bulgarian religious figure from Macedonia who was also a scholar and translator of the Bulgarian language. He was initially i ...

attempted to restore the Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ohrid, also known as the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

*T. Kamusella in The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, p. 276

*Aisling Lyon, Decentralisation and the Management of Ethni ...

as an autonomous Macedonian church, but his idea failed. Some authors consider that at that time, labels reflecting collective identity, such as "Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

", changed into national labels from being broad terms that were without political significance. According to Nick Antonovski, presenting a pro-Macedonian view, the 19th century foreign observers considered Macedonian Slavs to be Bulgarians - a view influenced by the Ottoman millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

, even though the term ''Bulgarian'' was a broad label that had no political significance, meaning nothing more than ''peasant''. Per John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.

John V. A. Fine Jr. (born 1939) is an American historian and author. He is professor of Balkan and Byzantine history at the University of Michigan and has written several books on the subject.

Early life and education

He was born in 1939 and grew ...

until the late 19th century those Macedonian Slavs who had developed an ethnic identity believed they were Bulgarians.

However the designation 'Bulgarian' also referred to all the Slavs living in Rumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Names of the Greeks#Romans (Ῥωμαῖοι), Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians f ...

. Per Raymond Detrez "Indeed, until the 1860s, as there are no documents or inscriptions mentioning the Macedonians as a separate ethnic group, all Slavs in Macedonia used to call themselves Bulgarians". The semi-official term '' Bulgarian Millet'', was used by the Ottoman Sultan for the first time in 1847, and was his tacit consent to a more ethno-linguistic definition of the Bulgarians as a separate ethic group. Officially as a separate ''Millet'' were recognized the Bulgarian Uniates in 1860, and then in 1870 the Bulgarian Exarchists

Bulgarian Millet ( tr, Bulgar Milleti) was an ethno-religious and linguistic community within the Ottoman Empire from the mid-19th to early 20th century. The semi-official term ''Bulgarian millet'', was used by the Sultan for the first time in ...

. With the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire

The rise of the Western notion of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman ''millet'' concept. An understanding of the concept of nationhood prevalent in the Ottoman Empire, which was different from the c ...

then, the classical Ottoman millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

began to degrade with the continuous identification of the religious creed with ethnic identity. In this way, in the struggle for recognition of a separate national Church

A national church is a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a draft discussing ...

, the modern Bulgarian nation was created, and the religious affiliation became a consequence of national allegiance.

On the eve of the 20th century the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; bg, Вътрешна Македонска Революционна Организация (ВМРО), translit=Vatrešna Makedonska Revoljucionna Organizacija (VMRO); mk, Внатр� ...

(IMARO) tried to unite all unsatisfied elements in the Ottoman Europe and struggled for political autonomy in the regions of Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace. But this manifestation of political separatism by the IMARO was a phenomenon without ethnic affiliation and the Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

ethnic provenance of the revolutionaries can not be put under question.

Balkan Wars and First World War

During theBalkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

and the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

the area was exchanged several times between Bulgaria and Serbia. The IMARO supported the Bulgarian army and authorities when they took temporary control over Vardar Macedonia. On the other hand, Serbian authorities put pressure on local people to declare themselves Serbs: they disbanded local governments, established by IMARO in Ohrid

Ohrid ( mk, Охрид ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the List of cities in North Macedonia, eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording ...

, Veles and other cities and persecuted Bulgarian priests and teachers, forcing them to flee and replacing them with Serbians. Serbian troops enforced a policy of disarming the local militia, accompanied by beatings and threats. During this period the political autonomism was abandoned as tactics and annexationist positions were supported, aiming eventual incorporation of the area into Bulgaria.

Interwar period and WWII

After the WWI, inSerbian Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia (Macedonian language, Macedonian and sr, Вардарска Македонија, ''Vardarska Makedonija'') was the name given to the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia (1912–1918) and Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941) roughl ...

any manifestations of Bulgarian nationhood were suppressed. Even in the so-called Western Outlands

The Western (Bulgarian) Outlands () is a term used by Bulgarians to describe several regions located in southeastern Serbia.

The territories in question were ceded by Bulgaria to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920 as a result ...

ceded by Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

in 1920 Bulgarian identification was prohibited. The Bulgarian notes to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, consented to recognize a Bulgarian minority in Yugoslavia were rejected. The members of the Council of the League assumed that the existence of some Bulgarian minority there was possible, however, they were determined to keep Yugoslavia and were aware that any exercise of revisionism, would open an uncontrollable wave of demands, turning the Balkans into a battlefield. Belgrade was suspicious of the recognition of any Bulgarian minority and was annoyed this would hinder its policy of forced “Serbianisation

Serbianisation or Serbianization, also known as Serbification, and Serbisation or Serbization ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", srbizacija, србизација or sh-Latn-Cyrl, label=none, separator=" / ", posrbljavanje, посрбљавање; ...

”. It blocked such recognition in neighboring Greece and Albania, through the failed ratifications of the Politis–Kalfov Protocol

The Politis–Kalfov Protocol ( bg, Спогодба „Калфов-Политис“; el, Πρωτόκολλο Πολίτη - Καλφώφ) was bilateral document signed at the League of Nations in Geneva in 1924 between Greece and Bulgaria and ...

in 1924 and the Albanian-Bulgarian Protocol (1932)

The Albanian-Bulgarian Protocol was a bilateral document signed in Sofia on January 9, 1932, between the Albanian Kingdom and the Kingdom of Bulgaria, concerning mutual protection for each other's minority populations. However the protocol was ne ...

.

During the interwar period in Vardar Macedonia, part of the young locals repressed by the Serbs attempted at a separate way of ethnic development. In 1934 the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

issued a resolution about the recognition of a separate Macedonian ethnicity. However, the existence of considerable Macedonian national consciousness prior to the 1940s is disputed.

This confusion is illustrated by Robert Newman in 1935, who recounts discovering in a village in Vardar Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia ( Macedonian and sr, Вардарска Македонија, ''Vardarska Makedonija'') was the name given to the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia (1912–1918) and Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941) roughly corresponding to t ...

two brothers, one who considered himself a Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

, and the other a Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

. In another village he met a man who had been "a Macedonian peasant all his life" but who had been at various times called a Turk, a Serb and a Bulgarian.Newman, R. (1952) ''Tito's Yugoslavia'' (London) During the Second World War the area was annexed by Bulgaria and anti-Serbian and pro-Bulgarian feelings among the local population prevailed. Because of that Vardar Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia ( Macedonian and sr, Вардарска Македонија, ''Vardarska Makedonija'') was the name given to the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia (1912–1918) and Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941) roughly corresponding to t ...

remained the only region where Yugoslav communist leader Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

had not developed a strong partisan movement in 1941. The new provinces were quickly staffed with officials from Bulgaria proper who behaved with typical official arrogance to the local inhabitants. The communists' power started growing only in 1943 with the capitulation of Italy and the Soviet victories over Nazi Germany. To improve the situation in the area Tito ordered the establishment of the Communist Party of Macedonia in March 1943 and the second AVNOJ congress on 29 November 1943 did recognise the ''Macedonian nation'' as separate entity. As a result, the resistance movement grew. However, by the end of the war, the Bulgarophile sentiments were still distinguishable and the Macedonian national consciousness hardly existed beyond a general conviction gained from bitter experience, that rule from Sofia was as unpalatable as that from Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

.

Post-World War II

After 1944 thePeople's Republic of Bulgaria

The People's Republic of Bulgaria (PRB; bg, Народна Република България (НРБ), ''Narodna Republika Balgariya, NRB'') was the official name of Bulgaria, when it was a socialist republic from 1946 to 1990, ruled by the ...

and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

began a policy of making Macedonia into the connecting link for the establishment of a future Balkan Federative Republic

The Balkan Federation project was a left-wing political movement to create a country in the Balkans by combining Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

The concept of a Balkan federation emerged in the late 19th century from ...

and stimulating the development of a distinct Slav Macedonian consciousness. The region received the status of a constituent republic within Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and in 1945 a separate Macedonian language

Macedonian (; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million ...

was codified. The population was proclaimed to be ethnic Macedonian, a nationality different from both Serbs and Bulgarians. With the proclamation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia as part of the Yugoslav federation, the new authorities also enforced measures that would overcome the pro-Bulgarian feeling among parts of its population. On the other hand, the Yugoslav authorities forcibly suppressed the ideologists of an independent Macedonian country. The Greek communists, similar to their fraternal parties in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, had already been influenced by the Comintern and were the only political party in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

to recognize Macedonian national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

. However, the situation deteriorated after they lost the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

. Thousands of Aegean Macedonians were expelled and fled to the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалистичка Република Македонија, Socijalistička Republika Makedonija), or SR Macedonia, commonly referred to as Socialist Macedonia or Yugoslav Macedonia, was ...

, while thousands of more children took refuge in other Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

countries.

Post-Informbiro period and Bulgarophobia

At the end of the 1950s theBulgarian Communist Party

The Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP; bg, Българска Комунистическа Партия (БКП), Balgarska komunisticheska partiya (BKP)) was the founding and ruling party of the People's Republic of Bulgaria from 1946 until 198 ...

repealed its previous decision and adopted a position denying the existence of a Macedonian ethnicity. As a result, the ''Bulgarophobia'' in Macedonia increased almost to the level of State ideology. This put an end to the idea of a Balkan Communist Federation

The Balkan Federation project was a left-wing political movement to create a country in the Balkans by combining Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

The concept of a Balkan federation emerged in the late 19th century from ...

. During the post-Informbiro period

The Informbiro period was an era of Yugoslavia's history following the Tito–Stalin split in mid-1948 that lasted until the country's partial rapprochement with the Soviet Union in 1955 with the signing of the Belgrade declaration. After Wor ...

, a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church

The Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-AO; mk, Македонска православна црква – Охридска архиепископија), or simply the Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) or the Archdiocese o ...

was established, splitting off from the Serbian Orthodox Church

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, Christian churches.

The majori ...

in 1967. The encouragement and evolution of the culture of the Republic of Macedonia

The culture of North Macedonia is the culture of the North Macedonia, Republic of North Macedonia, a country in the Balkans.

Architecture

Sites for archaeology of extraordinary quality include those at Stobi in Gradsko, North Macedonia, Grads ...

has had a far greater and more permanent impact on Macedonian nationalism than has any other aspect of Yugoslav policy. While the development of national music, films and graphic arts had been encouraged in the Republic of Macedonia, the greatest cultural effect came from the codification of the Macedonian language and literature, the new Macedonian national interpretation of history and the establishment of a Macedonian Orthodox Church

The Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-AO; mk, Македонска православна црква – Охридска архиепископија), or simply the Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) or the Archdiocese o ...

. Meanwhile, the Yugoslav historiography borrowed certain parts of the histories of its neighboring states in order to construct the Macedonian identity, having reached not only the times of medieval Bulgaria

In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire ( bg, Българско царство, ''Balgarsko tsarstvo'' ) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and the eleventh centuries and again between the ...

, but even as far back as Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

. In 1969, the first ''History of the Macedonian nation'' was published. Most Macedonians' attitude to Communist Yugoslavia, where they were recognized as a distinct nation for the first time, became positive. The Macedonian Communist elites were traditionally more pro-Serb and pro-Yugoslav than those in the rest of the Yugoslav Republics.

After the Second World War, Macedonian and Serbian scholars usually defined the ancient local tribes in the area of the Central Balkans as Daco-Moesian. Previously these entities were traditionally regarded in Yugoslavia as Illyrian, in accordance with the romantic early-20th-century interests in the Illyrian movement

The Illyrian movement ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Ilirski pokret, Илирски покрет; sl, Ilirsko gibanje) was a pan-South-Slavic cultural and political campaign with roots in the early modern period, and revived by a group of young Croatian inte ...

. At first, the Daco-Moesian tribes were separated through linguistic research. Later, Yugoslav archaeologists and historians came to an agreement that Daco-Moesians should be located in the areas of modern-day Serbia and North Macedonia. The most popular Daco-Moesian tribes described in Yugoslav literature were the Triballians, the Dardani

The Dardani (; grc, Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; la, Dardani) or Dardanians were a Paleo-Balkan people, who lived in a region that was named Dardania after their settlement there. They were among the oldest Balkan peoples, and their ...

ans and the Paeonians

Paeonians were an ancient Indo-European people that dwelt in Paeonia. Paeonia was an old country whose location was to the north of Ancient Macedonia, to the south of Dardania, to the west of Thrace and to the east of Illyria, most of their lan ...

. The leading research goal in the Republic of Macedonia during Yugoslav times was the establishment of some kind of ''Paionian identity'' and to separate it from the western "Illyrian" and the eastern "Thracian" entities. The idea of Paionian identity was constructed to conceptualize that Vardar Macedonia was neither Illyrian nor Thracian, favouring a more complex division, contrary to scientific claims about strict Thraco-Illyrian

The term Thraco-Illyrian refers to a hypothesis according to which the Daco-Thracian and Illyrian languages comprise a distinct branch of Indo-European. Thraco-Illyrian is also used as a term merely implying a Thracian- Illyrian interference, m ...

Balkan separation in neighbouring Bulgaria and Albania. Yugoslav Macedonian historiography argued also that the plausible link between the Slav Macedonians and their ancient namesakes was, at best, accidental.

Post-independence period and Antiquisation

On September 8, 1991, the

On September 8, 1991, the Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The Socialist Republic of Macedonia ( mk, Социјалистичка Република Македонија, Socijalistička Republika Makedonija), or SR Macedonia, commonly referred to as Socialist Macedonia or Yugoslav Macedonia, was ...

held a referendum that established its independence from Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

. With the fall of Communism

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Natio ...

, the breakup of Yugoslavia

The breakup of Yugoslavia occurred as a result of a series of political upheavals and conflicts during the early 1990s. After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yu ...

and the consequent lack of a Great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

in the region, the Republic of Macedonia came into permanent conflicts with its neighbors. Bulgaria contested its national identity and language, Greece contested its name and symbols, and Serbia its religious identity. On the other hand, the ethnic Albanians in the country insisted on being recognised as a nation, equal to the ethnic Macedonians. As a response, a more assertive and uncompromising form of Macedonian nationalism emerged. At that time the concept of ancient ''Paionian identity'' was changed to a kind of mixed ''Paionian-Macedonian'' identity which was later transformed to a separate ''ancient Macedonian identity'', establishing a direct link to the modern ethnic Macedonians. This phenomenon is called "ancient Macedonism", or "Antiquisation" ("Antikvizatzija", "антиквизација"). Its supporters claim that the ethnic Macedonians are not descendants of the Slavs only, but of the ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

too, who, according to them, were not Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

. Antiquisation is the policy which the nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: T ...

ruling party VMRO-DPMNE

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity ( mk, Внатрешна македонска револуционерна организација – Демократска партија за ...

pursued after coming to power in 2006, as a way of putting pressure on Greece, as well as for the purposes of domestic identity-building. Antiquisation

Antiquization ( mk, антиквизација), otherwise known as ancient Macedonism ( mk, links=no, антички македонизам), is a term used mainly to critically describe the identity policies conducted by the nationalist VMRO- ...

is also spreading due to a very intensive lobbying of the Macedonian diaspora

The Macedonian diaspora ( mk, Македонска дијаспора, ''Makedonska dijaspora'') consists of ethnic Macedonian emigrants and their descendants in countries such as Australia, Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand, Canada, ...

from the US, Canada, Germany and Australia, Some members of the Macedonian diaspora even believe, without basis, that certain modern historians, namely Ernst Badian

Ernst Badian (8 August 1925 – 1 February 2011) was an Austrian-born classical scholar who served as a professor at Harvard University from 1971 to 1998.

Early life and education

Badian was born in Vienna in 1925 and in 1938 fled the Nazis wit ...

, Peter Green, and Eugene Borza

Eugene N. Borza (3 March 1935 – 5 September 2021) was a professor emeritus of ancient history at Pennsylvania State University, where he taught from 1964 until 1995.

Academic career

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, USA, Borza came from a family of immi ...

, possess a pro-Macedonian bias in the Macedonian-Greek conflict.

Similar parahistorical myths connecting the Slavs and Paleo-Balkan peoples were characteristic for Ottoman Bulgaria during the late 18th and the 19th century and later arrose in Ottoman Macedonia. Practically, until the 1940s Bulgarian academic circles and Bulgarian volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term ''folk'') ...

history spread the same views when fighting Greek claims about the Greek origins of the ancient Macedonians.

As part of this policy, statues of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

and Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

have been built in several cities across the country. In 2011, a massive, 22-meter-tall statue of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

(called "Warrior on a horse" because of the dispute with Greece) was inaugurated in Macedonia Square in Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, as part of the Skopje 2014

Skopje 2014 ( mk, Скопје 2014) was a project financed by the Macedonian government of the then-ruling nationalist party VMRO-DPMNE, with the official purpose of giving the capital Skopje a more classical appeal. The project, officially anno ...

remodelling of the city. An even larger statue of Philip II is also constructed at the other end of the square. A triumphal arch named Porta Macedonia

Porta Macedonia ( Macedonian: ''Порта Македонија'') is a memorial arch located on Pella Square in Skopje, North Macedonia. Construction started in 2011 and was completed in January 2012.

The arch is 21 meters in height, and cost ...

, constructed in the same square, featuring images of historical figures including Alexander the Great, caused the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Foreign Ministry to lodge an official complaint to authorities in the Republic of Macedonia. Statues of Alexander are also on display in the town squares of Prilep

Prilep ( mk, Прилеп ) is the fourth-largest city in North Macedonia. It has a population of 66,246 and is known as "the city under Marko's Towers" because of its proximity to the towers of Prince Marko.

Name

The name of Prilep appear ...

and Štip

Štip ( mk, Штип ) is the largest urban agglomeration in the eastern part of North Macedonia, serving as the economic, industrial, entertainment and educational focal point for the surrounding municipalities.

As of the 2002 census, the city ...

, while a statue to Philip II of Macedon was recently built in Bitola

Bitola (; mk, Битола ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, north of the Medžitlija-Níki ...

. Additionally, many pieces of public infrastructure, such as airports, highways, and stadiums have been named after ancient historical figures or entities. Skopje's airport was renamed "Alexander the Great Airport" and features antique objects moved from Skopje's archeological museum. One of Skopje's main squares has been renamed Pella Square (after Pella

Pella ( el, Πέλλα) is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It is best-known for serving as the capital city of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon, and was the birthplace of Alexander the Great.

On site of the ancient cit ...

, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Macedon), while the main highway to Greece has been renamed to "Alexander of Macedon" and Skopje's largest stadium has been renamed "Philip II Arena". These actions are seen as deliberate provocations in neighboring Greece, exacerbating the dispute and further stalling Macedonia's EU and NATO applications. In 2008 a visit by Hunza Hunza may refer to:

* Hunza, Iran

* Hunza Valley, an area in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan

** Hunza (princely state), a former principality

** Hunza District, a recently established district

** Hunza River, a waterway

** Hunza Peak, a mou ...

Prince was organized in the Republic of Macedonia. The Hunza people

The Burusho, or Brusho, also known as the Botraj, are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to the Yasin, Hunza, Nagar, and other valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan in northern Pakistan, as well as in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Their language, Buru ...

of Northern Pakistan were proclaimed as direct descendants of the Alexandrian army and as people who are most closely related to the ethnic Macedonians. The Hunza delegation led by Mir Ghazanfar Ali Khan

Mir Ghazanfar Ali Khan (Urdu: میر غضنفر علی خان, born 31 December 1945) is a Pakistani politician who served as the 6th Governor of Gilgit-Baltistan.

He was appointed as a governor of Gilgit-Baltistan after governor Barjees Tahir. On ...

was welcomed at the Skopje Airport

Skopje International Airport ( mk, Меѓународен аеродром Скопје, translit=Megjunaroden aerodrom Skopje, ), also known as Skopje Airport ( mk, Аеродром Скопје, translit=Aerodrom Skopje), and Petrovec Airport ...

by the country's prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Nikola Gruevski

Nikola Gruevski ( mk, Никола Груевски, pronounced ; hu, Nikola Gruevszki; born 31 August 1970) is a Macedonian politician who served as Prime Minister of Macedonia from 2006 until his resignation, which was caused by the 2016 Mac ...

, the head of the Macedonian Orthodox Church

The Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-AO; mk, Македонска православна црква – Охридска архиепископија), or simply the Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) or the Archdiocese o ...

Archbishop Stephen and the mayor of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, Trifun Kostovski

Trifun Kostovski ( mk, Трифун Костовски; born 27 December 1946 in Skopje)

.

Such antiquization is facing criticism by academics as it demonstrates feebleness of archaeology and of other historical disciplines in public discourse, as well as a danger of marginalization

Social exclusion or social marginalisation is the social disadvantage and relegation to the fringe of society. It is a term that has been used widely in Europe and was first used in France in the late 20th century. It is used across discipline ...

. The policy has also attracted criticism domestically, by ethnic Macedonians within the country, who see it as dangerously dividing the country between those who identify with classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

and those who identify with the country's Slavic culture. Ethnic Albanians in North Macedonia

The Albanians in North Macedonia ( sq, Shqiptarët në Maqedoninë e Veriut, mk, Албанци во Северна Македонија) are the second largest ethnic group in North Macedonia, forming 446,245 individuals or 24.3% of the reside ...

see it as an attempt to marginalize them and exclude them from the national narrative. The policy, which also claims as ethnic Macedonians figures considered national heroes in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, such as Dame Gruev

Damyan Yovanov Gruev (,The first names can also be transliterated as ''Damjan Jovanov'', after Bulgarian Дамян Йованов Груев and Macedonian Дамјан Јованов Груев. The last name is also sometimes rendered as ''G ...

and Gotse Delchev

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian language, Bulgarian/Macedonian language, Macedonian: Георги/Ѓорѓи Николов Делчев; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (''Гоце Делчев ...

, has also drawn criticism from Bulgaria. Foreign diplomats had warned that the policy reduced international sympathy for the Republic of Macedonia in the then-naming dispute with Greece.

The background of this antiquization can be found in the 19th century and the myth of ancient descent among Orthodox Slavic-speakers in Macedonia. It was adopted partially due to Greek cultural inputs. This idea was also included in the national mythology during the post-WWII Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

. An additional factor for its preservation has been the influence of the Macedonian Diaspora

The Macedonian diaspora ( mk, Македонска дијаспора, ''Makedonska dijaspora'') consists of ethnic Macedonian emigrants and their descendants in countries such as Australia, Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand, Canada, ...

. Contemporary antiquization has been revived as an efficient tool for political mobilization and has been reinforced by the VMRO-DPMNE. For example, in 2009 the Macedonian Radio-Television

Macedonian Radio Television (MRT; mk, Македонска радио-телевизија (МРТ), Makedonska radio-televizija (MRT)), officially National Radio-Television ( mk, Национална Радиотелевизија, Nacionalna ...

aired a video named "Macedonian prayer

Macedonian Prayer (Macedonian Cyrillic: Македонска молитва - ''Makedonska molitva'') was a short film, functioning as a public service video produced in December 2008 and aired daily for the first several weeks of 2009 on a nation ...

" in which the Christian God

God in Christianity is believed to be the eternal, supreme being who created and preserves all things. Christians believe in a monotheistic conception of God, which is both transcendent (wholly independent of, and removed from, the material u ...

was presented calling the people of North Macedonia "the oldest nation on Earth" and "progenitors of the white race", who are described as "Macedonoids", in opposition to Negroids

Negroid (less commonly called Congoid) is an Historical race concepts, obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the ...

and Mongoloids

Mongoloid () is an Historical race concepts, obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. ...

.

This ultra-nationalism accompanied by the emphasizing of North Macedonia's ancient roots has raised concerns internationally about growing a kind of authoritarianism by the governing party. There have also been attempts at scientific claims about ancient nationhood, but they have had a negative impact on the international position of the country. On the other hand, there is still strong Yugonostalgia among the ethnic Macedonian population, that has swept also over other ex-Yugoslav states.

Macedonian nationalism also has support among high-ranking diplomats of North Macedonia who are serving abroad, and this continues to affect the relations with neighbors, especially Greece. In August 2017, the Consul of the Republic of Macedonia to Canada attended a nationalist Macedonian event in Toronto and delivered a speech against the backdrop of an irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

map of Greater Macedonia