Louis Pasteur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French

Louis Pasteur was born on 27 December 1822, in

Louis Pasteur was born on 27 December 1822, in

Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg in 1848, and became the chair of chemistry in 1852.

In February 1854, to have time to carry out work that could earn him the title of correspondent of the Institute, he got three months' paid leave with the help of a medical certificate of convenience. He extends the leave until 1 August, the date of the start of the exams. "I tell the Minister that I will go and do the examinations so as not to increase the embarrassment of the service. It is also so as not to leave to another a sum of 6 or 700 francs".

In this same year 1854, he was named dean of the new faculty of sciences at

Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg in 1848, and became the chair of chemistry in 1852.

In February 1854, to have time to carry out work that could earn him the title of correspondent of the Institute, he got three months' paid leave with the help of a medical certificate of convenience. He extends the leave until 1 August, the date of the start of the exams. "I tell the Minister that I will go and do the examinations so as not to increase the embarrassment of the service. It is also so as not to leave to another a sum of 6 or 700 francs".

In this same year 1854, he was named dean of the new faculty of sciences at

In Pasteur's early work as a

In Pasteur's early work as a

"Louis Pasteur's discovery of molecular chirality and spontaneous resolution in 1848, together with a complete review of his crystallographic and chemical work,"

''Acta Crystallographica'', Section A, vol. 65, pp. 371–389. The problem was that tartaric acid derived by

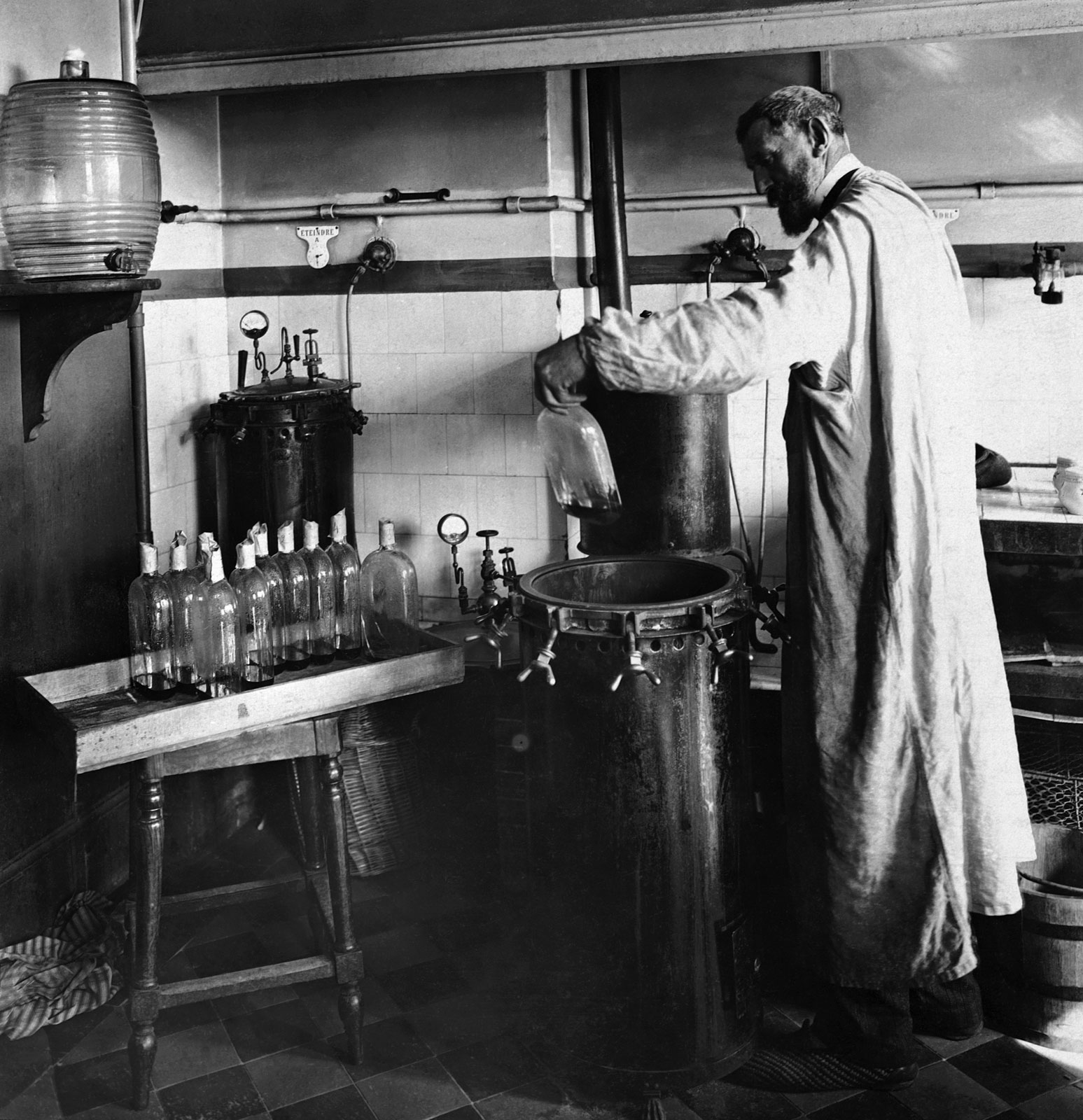

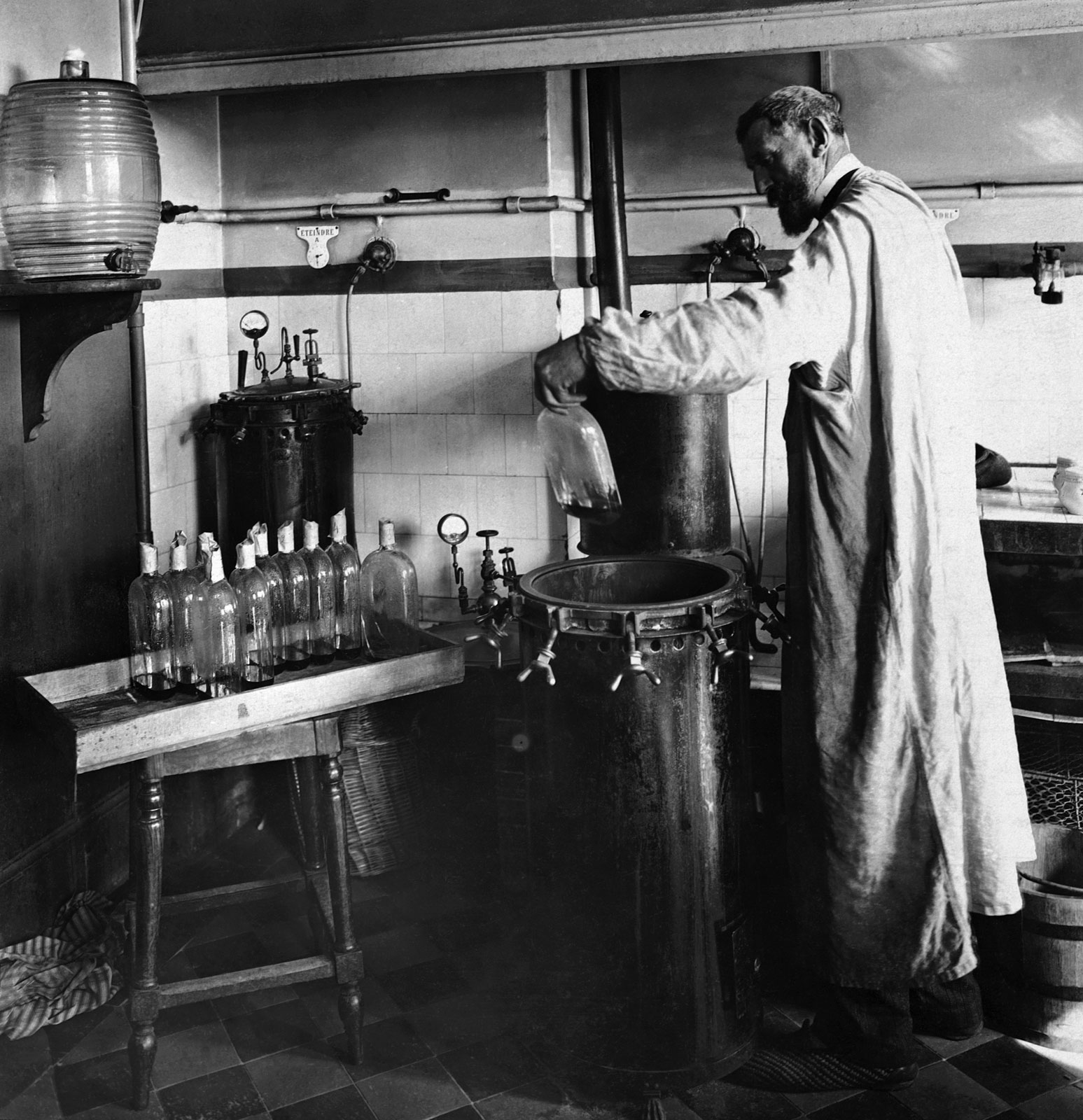

Pasteur's research also showed that the growth of micro-organisms was responsible for spoiling beverages, such as beer, wine and milk. With this established, he invented a process in which liquids such as milk were heated to a temperature between 60 and 100 °C. This killed most bacteria and moulds already present within them. Pasteur and

Pasteur's research also showed that the growth of micro-organisms was responsible for spoiling beverages, such as beer, wine and milk. With this established, he invented a process in which liquids such as milk were heated to a temperature between 60 and 100 °C. This killed most bacteria and moulds already present within them. Pasteur and

Following his fermentation experiments, Pasteur demonstrated that the skin of grapes was the natural source of yeasts, and that sterilized grapes and grape juice never fermented. He drew grape juice from under the skin with sterilized needles, and also covered grapes with sterilized cloth. Both experiments could not produce wine in sterilized containers.

His findings and ideas were against the prevailing notion of

Following his fermentation experiments, Pasteur demonstrated that the skin of grapes was the natural source of yeasts, and that sterilized grapes and grape juice never fermented. He drew grape juice from under the skin with sterilized needles, and also covered grapes with sterilized cloth. Both experiments could not produce wine in sterilized containers.

His findings and ideas were against the prevailing notion of

On 12 July 1880, Henri Bouley read before the French Academy of Sciences a report from Henry Toussaint, a

On 12 July 1880, Henri Bouley read before the French Academy of Sciences a report from Henry Toussaint, a

Pasteur produced the first vaccine for

Pasteur produced the first vaccine for

In many localities worldwide, streets are named in his honor. For example, in the US:

In many localities worldwide, streets are named in his honor. For example, in the US:  A statue of Pasteur is erected at

A statue of Pasteur is erected at

Pasteur married

Pasteur married

The Institut Pasteur

– Foundation dedicated to the prevention and treatment of diseases through biological research, education and public health activities

The Pasteur Foundation

– A US nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting the mission of the

Pasteur's Papers on the Germ Theory

The Life and Work of Louis Pasteur

Pasteur Brewing

The Pasteur Galaxy

* ttp://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/AB/BC/Louis_Pasteur.html Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)profile, AccessExcellence.org * * * * *

''Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences''

Articles published by Pasteur {{DEFAULTSORT:Pasteur, Louis 1822 births 1895 deaths People from Dole, Jura 19th-century French biologists French microbiologists 19th-century French chemists Vaccinologists École Normale Supérieure alumni Conservatoire national des arts et métiers alumni Lille University of Science and Technology faculty University of Strasbourg faculty Members of the Académie Française Members of the French Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 1st class Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Order of Agricultural Merit Leeuwenhoek Medal winners French Roman Catholics French humanitarians École des Beaux-Arts faculty Members of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Lycée Saint-Louis alumni Members of the American Philosophical Society Stereochemists

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

, microbial fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

and pasteurization, the latter of which was named after him. His research in chemistry led to remarkable breakthroughs in the understanding of the causes and preventions of diseases, which laid down the foundations of hygiene, public health and much of modern medicine. His works are credited to saving millions of lives through the developments of vaccines for rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

and anthrax. He is regarded as one of the founders of modern bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

and has been honored as the "father of bacteriology" and the "father of microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

" (together with Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

; the latter epithet also attributed to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

).

Pasteur was responsible for disproving the doctrine of spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise f ...

. Under the auspices of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

, his experiment demonstrated that in sterilized and sealed flasks, nothing ever developed; conversely, in sterilized but open flasks, microorganisms could grow. For this experiment, the academy awarded him the Alhumbert Prize carrying 2,500 francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

in 1862.

Pasteur is also regarded as one of the fathers of germ theory of diseases, which was a minor medical concept at the time. His many experiments showed that diseases could be prevented by killing or stopping germs, thereby directly supporting the germ theory and its application in clinical medicine. He is best known to the general public for his invention of the technique of treating milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. Immune factors and immune ...

and wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are m ...

to stop bacterial contamination, a process now called pasteurization. Pasteur also made significant discoveries in chemistry, most notably on the molecular basis for the asymmetry of certain crystals

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

and racemization In chemistry, racemization is a conversion, by heat or by chemical reaction, of an optically active compound into a racemic (optically inactive) form. This creates a 1:1 molar ratio of enantiomers and is referred too as a racemic mixture (i.e. conta ...

. Early in his career, his investigation of tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes, but also in bananas, tamarinds, and citrus. Its salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of tartar, develops naturally ...

resulted in the first resolution of what is now called optical isomerism

In chemistry, an enantiomer ( /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''; from Ancient Greek ἐνάντιος ''(enántios)'' 'opposite', and μέρος ''(méros)'' 'part') – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical anti ...

. His work led the way to the current understanding of a fundamental principle in the structure of organic compounds.

He was the director of the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

, established in 1887, until his death, and his body was interred in a vault beneath the institute. Although Pasteur made groundbreaking experiments, his reputation became associated with various controversies. Historical reassessment of his notebook revealed that he practiced deception to overcome his rivals.

Education and early life

Louis Pasteur was born on 27 December 1822, in

Louis Pasteur was born on 27 December 1822, in Dole, Jura

Dole (, sometimes pronounced ) is a commune in the Jura department, of which it is a subprefecture (''sous-préfecture''), in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region, in Eastern France. In 2019, it had a population of 23,711.

History

Dole was t ...

, France, to a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

family of a poor tanner. He was the third child of Jean-Joseph Pasteur and Jeanne-Etiennette Roqui. The family moved to Marnoz

Marnoz () is a commune in the Jura department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Jura department

The following is a list of the 494 communes of the Jura department of France.

The commun ...

in 1826 and then to Arbois in 1827. Pasteur entered primary school in 1831.

He was an average student in his early years, and not particularly academic, as his interests were fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

and sketching. He drew many pastels and portraits of his parents, friends and neighbors. Pasteur attended secondary school at the Collège d'Arbois. In October 1838, he left for Paris to join the Pension Barbet, but became homesick and returned in November.

In 1839, he entered the Collège Royal at Besançon

Besançon (, , , ; archaic german: Bisanz; la, Vesontio) is the prefecture of the department of Doubs in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. The city is located in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerl ...

to study philosophy and earned his Bachelor of Letters degree in 1840. He was appointed a tutor at the Besançon college while continuing a degree science course with special mathematics. He failed his first examination in 1841. He managed to pass the ''baccalauréat scientifique

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

'' (general science) degree from Dijon, where he earned his Bachelor of Science in Mathematics degree (Bachelier ès Sciences Mathématiques) in 1842, but with a mediocre grade in chemistry.

Later in 1842, Pasteur took the entrance test for the École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

. He passed the first set of tests, but because his ranking was low, Pasteur decided not to continue and try again next year. He went back to the Pension Barbet to prepare for the test. He also attended classes at the Lycée Saint-Louis

The lycée Saint-Louis is a highly selective post-secondary school located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, in the Latin Quarter. It is the only public French lycée exclusively dedicated to providing '' classes préparatoires aux grandes ...

and lectures of Jean-Baptiste Dumas at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

. In 1843, he passed the test with a high ranking and entered the École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

. In 1845 he received the '' licencié ès sciences'' degree. In 1846, he was appointed professor of physics at the Collège de Tournon (now called Lycée Gabriel-Faure) in Ardèche. But the chemist Antoine Jérôme Balard wanted him back at the ''École Normale Supérieure'' as a graduate laboratory assistant (''agrégé préparateur''). He joined Balard and simultaneously started his research in crystallography and in 1847, he submitted his two theses, one in chemistry and the other in physics: (a) Chemistry Thesis: "Recherches sur la capacité de saturation de l'acide arsénieux. Etudes des arsénites de potasse, de soude et d'ammoniaque."; (b) Physics Thesis: "1. Études des phénomènes relatifs à la polarisation rotatoire des liquides. 2. Application de la polarisation rotatoire des liquides à la solution de diverses questions de chimie."

After serving briefly as professor of physics at the Dijon Lycée

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

in 1848, he became professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (french: Université de Strasbourg, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, Alsace, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers.

The French university traces its history to the ea ...

, where he met and courted Marie Laurent

Marie Pasteur, née Laurent (15 January 1826 in Clermont-Ferrand, France – 28 September 1910 in Paris), was the scientific assistant and co-worker of her spouse, the famous French chemist and bacteriologist Louis Pasteur.

Life

Marie Pasteur ...

, daughter of the university's rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

in 1849. They were married on 29 May 1849, and together had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood; the other three died of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

.

Career

Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg in 1848, and became the chair of chemistry in 1852.

In February 1854, to have time to carry out work that could earn him the title of correspondent of the Institute, he got three months' paid leave with the help of a medical certificate of convenience. He extends the leave until 1 August, the date of the start of the exams. "I tell the Minister that I will go and do the examinations so as not to increase the embarrassment of the service. It is also so as not to leave to another a sum of 6 or 700 francs".

In this same year 1854, he was named dean of the new faculty of sciences at

Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Strasbourg in 1848, and became the chair of chemistry in 1852.

In February 1854, to have time to carry out work that could earn him the title of correspondent of the Institute, he got three months' paid leave with the help of a medical certificate of convenience. He extends the leave until 1 August, the date of the start of the exams. "I tell the Minister that I will go and do the examinations so as not to increase the embarrassment of the service. It is also so as not to leave to another a sum of 6 or 700 francs".

In this same year 1854, he was named dean of the new faculty of sciences at University of Lille

The University of Lille (french: Université de Lille, abbreviated as ULille, UDL or univ-lille) is a French public research university based in Lille, Hauts-de-France. It has its origins in the University of Douai (1559), and resulted from the ...

, where he began his studies on fermentation. It was on this occasion that Pasteur uttered his oft-quoted remark: "''dans les champs de l'observation, le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés''" ("In the field of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind").

In 1857, he moved to Paris as the director of scientific studies at the ''École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

'' where he took control from 1858 to 1867 and introduced a series of reforms to improve the standard of scientific work. The examinations became more rigid, which led to better results, greater competition, and increased prestige. Many of his decrees, however, were rigid and authoritarian, leading to two serious student revolts. During "the bean revolt" he decreed that a mutton stew, which students had refused to eat, would be served and eaten every Monday. On another occasion he threatened to expel any student caught smoking, and 73 of the 80 students in the school resigned.

In 1863, he was appointed professor of geology, physics, and chemistry at the ''École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts

The Beaux-Arts de Paris is a French ''grande école'' whose primary mission is to provide high-level arts education and training. This is classical and historical School of Fine Arts in France. The art school, which is part of the Paris Science ...

'', a position he held until his resignation in 1867. In 1867, he became the chair of organic chemistry at the Sorbonne, but he later gave up the position because of poor health. In 1867, the École Normale's laboratory of physiological chemistry was created at Pasteur's request, and he was the laboratory's director from 1867 to 1888. In Paris, he established the Pasteur Institute in 1887, in which he was its director for the rest of his life.

Research

Molecular asymmetry

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, beginning at the ''École Normale Supérieure'', and continuing at Strasbourg and Lille, he examined the chemical, optical and crystallographic properties of a group of compounds known as tartrates

A tartrate is a salt or ester of the organic compound tartaric acid, a dicarboxylic acid. The formula of the tartrate dianion is O−OC-CH(OH)-CH(OH)-COO− or C4H4O62−.

The main forms of tartrates used commercially are pure crystalline ta ...

.

He resolved a problem concerning the nature of tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes, but also in bananas, tamarinds, and citrus. Its salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of tartar, develops naturally ...

in 1848.Joseph Gal: ''Louis Pasteur, Language, and Molecular Chirality. I. Background and Dissymmetry'', Chirality ''23'' (2011) 1−16. A solution of this compound derived from living things rotated the plane of polarization

The term ''plane of polarization'' refers to the direction of polarization of '' linearly-polarized'' light or other electromagnetic radiation. Unfortunately the term is used with two contradictory meanings. As originally defined by Étienne-Lou ...

of light passing through it.H.D. Flack (2009"Louis Pasteur's discovery of molecular chirality and spontaneous resolution in 1848, together with a complete review of his crystallographic and chemical work,"

''Acta Crystallographica'', Section A, vol. 65, pp. 371–389. The problem was that tartaric acid derived by

chemical synthesis

As a topic of chemistry, chemical synthesis (or combination) is the artificial execution of chemical reactions to obtain one or several products. This occurs by physical and chemical manipulations usually involving one or more reactions. In moder ...

had no such effect, even though its chemical reactions were identical and its elemental composition was the same.

Pasteur noticed that crystals of tartrates had small faces. Then he observed that, in racemic mixtures of tartrates, half of the crystals were right-handed and half were left-handed. In solution, the right-handed compound was dextrorotatory

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

, and the left-handed one was levorotatory. Pasteur determined that optical activity related to the shape of the crystals, and that an asymmetric internal arrangement of the molecules of the compound was responsible for twisting the light. The (2''R'',3''R'')- and (2''S'',3''S'')- tartrates were isometric, non-superposable mirror images of each other. This was the first time anyone had demonstrated molecular chirality, and also the first explanation of isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

Iso ...

ism.

Some historians consider Pasteur's work in this area to be his "most profound and most original contributions to science", and his "greatest scientific discovery."

Fermentation and germ theory of diseases

Pasteur was motivated to investigate fermentation while working at Lille. In 1856 a local wine manufacturer, M. Bigot, whose son was one of Pasteur's students, sought for his advice on the problems of making beetroot alcohol and souring. Pasteur began his research in the topic by repeating and confirming works ofTheodor Schwann

Theodor Schwann (; 7 December 181011 January 1882) was a German physician and physiologist. His most significant contribution to biology is considered to be the extension of cell theory to animals. Other contributions include the discovery of ...

, who demonstrated a decade earlier that yeast were alive.

According to his son-in-law, René Vallery-Radot, in August 1857 Pasteur sent a paper about lactic acid fermentation to the Société des Sciences de Lille, but the paper was read three months later. A memoire was subsequently published on 30 November 1857. In the memoir, he developed his ideas stating that: "I intend to establish that, just as there is an alcoholic ferment, the yeast of beer, which is found everywhere that sugar is decomposed into alcohol and carbonic acid, so also there is a particular ferment, a lactic yeast, always present when sugar becomes lactic acid."

Pasteur also wrote about alcoholic fermentation. It was published in full form in 1858. Jöns Jacob Berzelius and Justus von Liebig

Justus Freiherr von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 20 April 1873) was a German scientist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry. As a professor at t ...

had proposed the theory that fermentation was caused by decomposition. Pasteur demonstrated that this theory was incorrect, and that yeast was responsible for fermentation to produce alcohol from sugar. He also demonstrated that, when a different microorganism contaminated the wine, lactic acid was produced, making the wine sour. In 1861, Pasteur observed that less sugar fermented per part of yeast when the yeast was exposed to air. The lower rate of fermentation aerobically became known as the Pasteur effect

The Pasteur effect describes how available oxygen inhibits ethanol fermentation, driving yeast to switch toward aerobic respiration for increased generation of the energy carrier adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Discovery

The effect was described b ...

.

Pasteur's research also showed that the growth of micro-organisms was responsible for spoiling beverages, such as beer, wine and milk. With this established, he invented a process in which liquids such as milk were heated to a temperature between 60 and 100 °C. This killed most bacteria and moulds already present within them. Pasteur and

Pasteur's research also showed that the growth of micro-organisms was responsible for spoiling beverages, such as beer, wine and milk. With this established, he invented a process in which liquids such as milk were heated to a temperature between 60 and 100 °C. This killed most bacteria and moulds already present within them. Pasteur and Claude Bernard

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. Historian I. Bernard Cohen of Harvard University called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term '' milieu intérieur'', and the ...

completed tests on blood and urine on 20 April 1862. Pasteur patented the process, to fight the "diseases" of wine, in 1865. The method became known as pasteurization, and was soon applied to beer and milk.

Beverage contamination led Pasteur to the idea that micro-organisms infecting animals and humans cause disease. He proposed preventing the entry of micro-organisms into the human body, leading Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

to develop antiseptic

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

methods in surgery.

In 1866, Pasteur published ''Etudes sur le Vin'', about the diseases of wine, and he published ''Etudes sur la Bière'' in 1876, concerning the diseases of beer.

In the early 19th century, Agostino Bassi

Agostino Bassi, sometimes called de Lodi (25 September 1773 – 8 February 1856), was an Italian entomologist. He preceded Louis Pasteur in the discovery that microorganisms can be the cause of disease (the germ theory of disease). He discovered ...

had shown that muscardine

Muscardine is a disease of insects. It is caused by many species of entomopathogenic fungus. Many muscardines are known for affecting silkworms.Singh, T. ''Principles And Techniques Of Silkworm Seed Production''. Discovery Publishing House. 2004. ...

was caused by a fungus that infected silkworms. Since 1853, two diseases called ''pébrine

Pébrine, or "pepper disease," is a disease of silkworms, which is caused by protozoan microsporidian parasites, mainly '' Nosema bombycis'' and, to a lesser extent, '' Vairimorpha'', '' Pleistophora'' and '' Thelohania'' species. The parasites i ...

'' and ''flacherie

Flacherie (literally: "flaccidness") is a disease of silkworms, caused by silkworms eating infected or contaminated mulberry leaves. Flacherie infected silkworms look weak and can die from this disease. Silkworm larvae that are about to die from ...

'' had been infecting great numbers of silkworm

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically imp ...

s in southern France, and by 1865 they were causing huge losses to farmers. In 1865, Pasteur went to Alès

Alès (; oc, Alès) is a Communes of France, commune in the Gard Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie regions of France, region in southern France. It is one of the Subprefectures in France, su ...

and worked for five years until 1870.

Silkworms with pébrine were covered in corpuscles. In the first three years, Pasteur thought that the corpuscles were a symptom of the disease. In 1870, he concluded that the corpuscles were the cause of pébrine (it is now known that the cause is a microsporidian

Microsporidia are a group of spore-forming unicellular parasites. These spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical part of the spore. They were once considered protozoans or pr ...

). Pasteur also showed that the disease was hereditary. Pasteur developed a system to prevent pébrine: after the female moths laid their eggs, the moths were turned into a pulp. The pulp was examined with a microscope, and if corpuscles were observed, the eggs were destroyed. Pasteur concluded that bacteria caused flacherie. The primary cause is currently thought to be viruses. The spread of flacherie could be accidental or hereditary. Hygiene could be used to prevent accidental flacherie. Moths whose digestive cavities did not contain the microorganisms causing flacherie were used to lay eggs, preventing hereditary flacherie.

Spontaneous generation

spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise f ...

. He received a particularly stern criticism from Félix Archimède Pouchet

Félix-Archimède Pouchet (26 August 1800 – 6 December 1872) was a French naturalist and a leading proponent of spontaneous generation of life from non-living materials, and as such an opponent of Louis Pasteur's germ theory. He was the father ...

, who was director of the Rouen Museum of Natural History. To settle the debate between the eminent scientists, the French Academy of Sciences offered the Alhumbert Prize carrying 2,500 francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

to whoever could experimentally demonstrate for or against the doctrine.

Pouchet stated that air everywhere could cause spontaneous generation of living organisms in liquids. In the late 1850s, he performed experiments and claimed that they were evidence of spontaneous generation. Francesco Redi and Lazzaro Spallanzani

Lazzaro Spallanzani (; 12 January 1729 – 11 February 1799) was an Italian Catholic priest (for which he was nicknamed Abbé Spallanzani), biologist and physiologist who made important contributions to the experimental study of bodily function ...

had provided some evidence against spontaneous generation in the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. Spallanzani's experiments in 1765 suggested that air contaminated broths with bacteria. In the 1860s, Pasteur repeated Spallanzani's experiments, but Pouchet reported a different result using a different broth.

Pasteur performed several experiments to disprove spontaneous generation. He placed boiled liquid in a flask and let hot air enter the flask. Then he closed the flask, and no organisms grew in it. In another experiment, when he opened flasks containing boiled liquid, dust entered the flasks, causing organisms to grow in some of them. The number of flasks in which organisms grew was lower at higher altitudes, showing that air at high altitudes contained less dust and fewer organisms. Pasteur also used swan neck flask

A swan neck flask, also known as a gooseneck flask, is a round-bottom flask with a narrow s-shaped tube as its opening to reduce contact between the inner contents and external environment. The motion of air through the tube is slowed and aerosoli ...

s containing a fermentable liquid. Air was allowed to enter the flask via a long curving tube that made dust particles stick to it. Nothing grew in the broths unless the flasks were tilted, making the liquid touch the contaminated walls of the neck. This showed that the living organisms that grew in such broths came from outside, on dust, rather than spontaneously generating within the liquid or from the action of pure air.

These were some of the most important experiments disproving the theory of spontaneous generation. Pasteur gave a series of five presentations of his findings before the French Academy of Sciences in 1881, which were published in 1882 as ''Mémoire'' ''Sur les corpuscules organisés qui existent dans l'atmosphère: Examen de la doctrine des générations spontanées'' (''Account of Organized Corpuscles Existing in the Atmosphere: Examining the Doctrine of Spontaneous Generation''). Pasteur won the Alhumbert Prize in 1862. He concluded that:Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment. There is no known circumstance in which it can be confirmed that microscopic beings came into the world without germs, without parents similar to themselves.

Silkworm disease

In 1865, Jean-Baptiste Dumas, chemist, senator and former Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, asked Pasteur to study a new disease that was decimatingsilkworm

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically imp ...

farms from the south of France and Europe, the pébrine

Pébrine, or "pepper disease," is a disease of silkworms, which is caused by protozoan microsporidian parasites, mainly '' Nosema bombycis'' and, to a lesser extent, '' Vairimorpha'', '' Pleistophora'' and '' Thelohania'' species. The parasites i ...

, characterized on a macroscopic scale by black spots and on a microscopic scale by the " Cornalia corpuscles". Pasteur accepted and made five long stays in Alès

Alès (; oc, Alès) is a Communes of France, commune in the Gard Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie regions of France, region in southern France. It is one of the Subprefectures in France, su ...

, between 7 June 1865 and 1869.

Initial errors

Arriving in Alès, Pasteur familiarized himself with pébrine and also with another disease of the silkworm, known earlier than pebrine:flacherie

Flacherie (literally: "flaccidness") is a disease of silkworms, caused by silkworms eating infected or contaminated mulberry leaves. Flacherie infected silkworms look weak and can die from this disease. Silkworm larvae that are about to die from ...

or dead-flat disease. Contrary, for example, to Quatrefages, who coined the new word ''pébrine'', Pasteur makes the mistake of believing that the two diseases were the same and even that most of the diseases of silkworms known up to that time were identical with each other and with pébrine. It was in letters of 30 April and 21 May 1867 to Dumas that he first made the distinction between pébrine and flacherie.

He made another mistake: he began by denying the "parasitic" (microbial) nature of pébrine, which several scholars (notably Antoine Béchamp

Pierre Jacques Antoine Béchamp (16 October 1816 – 15 April 1908) was a French scientist now best known for breakthroughs in applied organic chemistry and for a bitter rivalry with Louis Pasteur.

Béchamp developed the Béchamp reduction ...

) considered well established. Even a note published on 27 August 1866 by Balbiani, which Pasteur at first seemed to welcome favourably had no effect, at least immediately. "Pasteur is mistaken. He would only change his mind in the course of 1867".

Victory over pébrine

At a time where Pasteur had not yet understood the cause of the pébrine, he propagated an effective process to stop infections: a sample of chrysalises was chosen, they were crushed and the corpuscles were searched for in the crushed material; if the proportion of corpuscular pupae in the sample was very low, the chamber was considered good for reproduction. This method of sorting “seeds” (eggs) is close to a method that Osimo had proposed a few years earlier, but whose trials had not been conclusive. By this process, Pasteur curbs pébrine and saves many of the silk industry in the Cévennes.Flacherie resists

In 1878, at the ''Congrès international séricicole'', Pasteur admitted that "if pébrine is overcome, flacherie still exerts its ravages". He attributed the persistence of flacherie to the fact that the farmers had not followed his advice. In 1884, Balbiani, who disregarded the theoretical value of Pasteur's work on silkworm diseases, acknowledged that his practical process had remedied the ravages of pébrine, but added that this result tended to be counterbalanced by the development of flacherie, which was less well known and more difficult to prevent. Despite Pasteur's success against pébrine, French sericulture had not been saved from damage. (See :fr:Sériciculture in the French Wikipedia.)Immunology and vaccination

Chicken cholera

Pasteur's first work on vaccine development was onchicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

. He received the bacteria samples (later called ''Pasteurella multocida'' after him) from Henry Toussaint. He started the study in 1877, and by the next year, was able to maintain a stable culture using broths. After another year of continuous culturing, he found that the bacteria were less pathogenic. Some of his culture samples could no longer induce the disease in healthy chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster or cock is a term for an adult m ...

s. In 1879, Pasteur, planning for holiday, instructed his assistant, Charles Chamberland

Charles Chamberland (; 12 March 1851 – 2 May 1908) was a French microbiologist from Chilly-le-Vignoble in the department of Jura who worked with Louis Pasteur.

In 1884 he developed a type of filtration known today as the Chamberland filter ...

to inoculate the chickens with fresh bacteria culture. Chamberland forgot and went on holiday himself. On his return, he injected the month-old cultures to healthy chickens. The chickens showed some symptoms of infection, but instead of the infections being fatal, as they usually were, the chickens recovered completely. Chamberland assumed an error had been made, and wanted to discard the apparently faulty culture, but Pasteur stopped him. Pasteur injected the freshly recovered chickens with fresh bacteria that normally would kill other chickens; the chickens no longer showed any sign of infection. It was clear to him that the weakened bacteria had caused the chickens to become immune

In biology, immunity is the capability of multicellular organisms to resist harmful microorganisms. Immunity involves both specific and nonspecific components. The nonspecific components act as barriers or eliminators of a wide range of pathogens ...

to the disease.

In December 1880, Pasteur presented his results to the French Academy of Sciences as "''Sur les maladies virulentes et en particulier sur la maladie appelée vulgairement choléra des poules'' (On virulent diseases, and in particular on the disease commonly called chicken cholera)" and published it in the academy's journal ('' Comptes-Rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des Sciences''). He attributed that the bacteria were weakened by contact with oxygen. He explained that bacteria kept in sealed containers never lost their virulence, and only those exposed to air in culture media could be used as vaccine. Pasteur introduced the term "attenuation" for this weakening of virulence as he presented before the academy, saying:We can diminish the microbe’s virulence by changing the mode of culturing. This is the crucial point of my subject. I ask the Academy not to criticize, for the time being, the confidence of my proceedings that permit me to determine the microbe’s attenuation, in order to save the independence of my studies and to better assure their progress... n conclusionI would like to point out to the Academy two main consequences to the facts presented: the hope to culture all microbes and to find a vaccine for all infectious diseases that have repeatedly afflicted humanity, and are a major burden on agriculture and breeding of domestic animals.In fact, Pasteur's vaccine against chicken cholera was not regular in its effects and was a failure.

Anthrax

In the 1870s, he applied this immunization method to anthrax, which affectedcattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

, and aroused interest in combating other diseases. Pasteur cultivated bacteria from the blood of animals infected with anthrax. When he inoculated animals with the bacteria, anthrax occurred, proving that the bacteria was the cause of the disease. Many cattle were dying of anthrax in "cursed fields". Pasteur was told that sheep that died from anthrax were buried in the field. Pasteur thought that earthworms might have brought the bacteria to the surface. He found anthrax bacteria in earthworms' excrement, showing that he was correct. He told the farmers not to bury dead animals in the fields. Pasteur had been trying to develop the anthrax vaccine since 1877, soon after Robert Koch's discovery of the bacterium.

On 12 July 1880, Henri Bouley read before the French Academy of Sciences a report from Henry Toussaint, a

On 12 July 1880, Henri Bouley read before the French Academy of Sciences a report from Henry Toussaint, a veterinary surgeon

Veterinary surgery is surgery performed on animals by veterinarians, whereby the procedures fall into three broad categories: orthopaedics (bones, joints, muscles), soft tissue surgery (skin, body cavities, cardiovascular system, GI/urogenital/ ...

, who was not member of the academy. Toussaint had developed anthrax vaccine by killing the bacilli by heating at 55 °C for 10 minutes. He tested on eight dogs and 11 sheep, half of which died after inoculation. It was not a great success. Upon hearing the news, Pasteur immediately wrote to the academy that he could not believe that dead vaccine would work and that Toussaint's claim "overturns all the ideas I had on viruses, vaccines, etc." Following Pasteur's criticism, Toussaint switched to carbolic acid

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromaticity, aromatic organic compound with the molecular chemical formula, formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatility (chemistry), volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

to kill anthrax bacilli and tested the vaccine on sheep in August 1880. Pasteur thought that this type of killed vaccine should not work because he believed that attenuated bacteria used up nutrients that the bacteria needed to grow. He thought oxidizing bacteria made them less virulent.

But Pasteur found that anthrax bacillus was not easily weakened by culturing in air as it formed spores – unlike chicken cholera bacillus. In early 1881, he discovered that growing anthrax bacilli at about 42 °C made them unable to produce spores, and he described this method in a speech to the French Academy of Sciences on 28 February. On 21 March, he announced successful vaccination of sheep. To this news, veterinarian Hippolyte Rossignol proposed that the Société d'agriculture de Melun organize an experiment to test Pasteur's vaccine. Pasteur signed agreement of the challenge on 28 April. A public experiment was conducted in May at Pouilly-le-Fort. 58 sheep, 2 goats and 10 cattle were used, half of which were given the vaccine on 5 and 17 May; while the other half was untreated. All the animals were injected with the fresh virulent culture of anthrax bacillus on 31 May. The official result was observed and analysed on 2 June in the presence of over 200 spectators. All cattle survived, vaccinated or not. Pasteur had bravely predicted: "I hypothesized that the six vaccinated cows would not become very ill, while the four unvaccinated cows would perish or at least become very ill." However, all vaccinated sheep and goats survived, while unvaccinated ones had died or were dying before the viewers. His report to the French Academy of Sciences on 13 June concludes:ylooking at everything from the scientific point of view, the development of a vaccination against anthrax constitutes significant progress beyond the first vaccine developed by Jenner, since the latter had never been obtained experimentally.Pasteur did not directly disclose how he prepared the vaccines used at Pouilly-le-Fort. Although his report indicated it as a "live vaccine", his laboratory notebooks show that he actually used

potassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate, , is a common inorganic chemical reagent, most commonly used as an oxidizing agent in various laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is acutely and chronically harmful to health ...

-killed vaccine, as developed by Chamberland, quite similar to Toussaint's method.

The notion of a weak form of a disease causing immunity to the virulent version was not new; this had been known for a long time for smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Inoculation with smallpox (variolation

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (''Variola'') with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. Var ...

) was known to result in a much less severe disease, and greatly reduced mortality, in comparison with the naturally acquired disease. Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner, (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was a British physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines, and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

had also studied vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

using cowpox

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by the ''cowpox virus'' (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more ...

(''vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

'') to give cross-immunity to smallpox in the late 1790s, and by the early 1800s vaccination had spread to most of Europe.

The difference between smallpox vaccination and anthrax or chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

vaccination was that the latter two disease organisms had been artificially weakened, so a naturally weak form of the disease organism did not need to be found. This discovery revolutionized work in infectious diseases, and Pasteur gave these artificially weakened diseases the generic name of "vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

s", in honour of Jenner's discovery.

In 1876, Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

had shown that '' Bacillus anthracis'' caused anthrax. In his papers published between 1878 and 1880, Pasteur only mentioned Koch's work in a footnote. Koch met Pasteur at the Seventh International Medical Congress

The International Medical Congress (french: Congrès International de Médecine) was a series of international scientific conferences on medicine that took place, periodically, from 1867 until 1913.

The idea of such a congress came in 1865, dur ...

in 1881. A few months later, Koch wrote that Pasteur had used impure cultures and made errors. In 1882, Pasteur replied to Koch in a speech, to which Koch responded aggressively. Koch stated that Pasteur tested his vaccine on unsuitable animals and that Pasteur's research was not properly scientific. In 1882, Koch wrote "On the Anthrax Inoculation", in which he refuted several of Pasteur's conclusions about anthrax and criticized Pasteur for keeping his methods secret, jumping to conclusions, and being imprecise. In 1883, Pasteur wrote that he used cultures prepared in a similar way to his successful fermentation experiments and that Koch misinterpreted statistics and ignored Pasteur's work on silkworms.

Swine erysipelas

In 1882, Pasteur sent his assistant Louis Thuillier to southern France because of anepizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "epi ...

of swine erysipelas. Thuillier identified the bacillus that caused the disease in March 1883. Pasteur and Thuillier increased the bacillus's virulence after passing it through pigeons. Then they passed the bacillus through rabbits, weakening it and obtaining a vaccine. Pasteur and Thuillier incorrectly described the bacterium as a figure-eight shape. Roux described the bacterium as stick-shaped in 1884.

Rabies

Pasteur produced the first vaccine for

Pasteur produced the first vaccine for rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

by growing the virus in rabbits, and then weakening it by drying the affected nerve tissue. The rabies vaccine was initially created by Emile Roux

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*'' Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*'' Emil and the Detecti ...

, a French doctor and a colleague of Pasteur, who had produced a killed vaccine using this method. The vaccine had been tested in 50 dogs before its first human trial. This vaccine was used on 9-year-old Joseph Meister

Joseph Meister (21 February 1876 – 24 June 1940) was the first person to be inoculated against rabies by Louis Pasteur, and likely the first person to be successfully treated for the infection.

History

In 1885, nine-year-old Meister was b ...

, on 6 July 1885, after the boy was badly mauled by a rabid dog. This was done at some personal risk for Pasteur, since he was not a licensed physician and could have faced prosecution for treating the boy. After consulting with physicians, he decided to go ahead with the treatment. Over 11 days, Meister received 13 inoculations, each inoculation using viruses that had been weakened for a shorter period of time. Three months later he examined Meister and found that he was in good health. Pasteur was hailed as a hero and the legal matter was not pursued. Analysis of his laboratory notebooks shows that Pasteur had treated two people before his vaccination of Meister. One survived but may not actually have had rabies, and the other died of rabies. Pasteur began treatment of Jean-Baptiste Jupille on 20 October 1885, and the treatment was successful. Later in 1885, people, including four children from the United States, went to Pasteur's laboratory to be inoculated. In 1886, he treated 350 people, of which only one developed rabies. The treatment's success laid the foundations for the manufacture of many other vaccines. The first of the Pasteur Institutes was also built on the basis of this achievement.

In ''The Story of San Michele

''The Story of San Michele'' is a book of memoirs by Swedish physician Axel Munthe (October 31, 1857 – February 11, 1949) first published in 1929 by British publisher John Murray. Written in English, it was a bestseller in numerous language ...

'', Axel Munthe writes of some risks Pasteur undertook in the rabies vaccine research:

Because of his study in germs, Pasteur encouraged doctors to sanitize their hands and equipment before surgery. Prior to this, few doctors or their assistants practiced these procedures. Ignaz Semmelweis

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (; hu, Semmelweis Ignác Fülöp ; 1 July 1818 – 13 August 1865) was a Hungarian physician and scientist, who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures. Described as the "saviour of mothers", he discovered that t ...

and Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

had earlier practiced hand sanitizing in medical contexts in the 1860s.

Controversies

A French national hero at age 55, in 1878 Pasteur discreetly told his family to never reveal his laboratory notebooks to anyone. His family obeyed, and all his documents were held and inherited in secrecy. Finally, in 1964 Pasteur's grandson and last surviving male descendant, Pasteur Vallery-Radot, donated the papers to theFrench national library

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

. Yet the papers were restricted for historical studies until the death of Vallery-Radot in 1971. The documents were given a catalogue number only in 1985.

In 1995, the centennial of the death of Louis Pasteur, a historian of science Gerald L. Geison

Gerald Lynn Geison (March 26, 1943 – July 3, 2001) was an American historian who died at 58.

Career

Gerald L. Geison went on to earn a doctorate in Yale University's ''Department of the History of Science and Medicine'' in 1970 and then joined ...

published an analysis of Pasteur's private notebooks in his ''The Private Science of Louis Pasteur'', and declared that Pasteur had given several misleading accounts and played deceptions in his most important discoveries. Max Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz (19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002) was an Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of haemoglobin and myoglobin. He went ...

published a defense of Pasteur in ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of i ...

''. Based on further examinations of Pasteur's documents, French immunologist Patrice Debré concluded in his book'' Louis Pasteur'' (1998) that, in spite of his genius, Pasteur had some faults. A book review states that Debré "sometimes finds him unfair, combative, arrogant, unattractive in attitude, inflexible and even dogmatic".

Fermentation

Scientists before Pasteur had studied fermentation. In the 1830s, Charles Cagniard-Latour,Friedrich Traugott Kützing

Friedrich Traugott Kützing (8 December 1807 in Ritteburg – 9 September 1893) was a German pharmacist, botanist and phycologist.

Despite his limited background in regard to higher education, Kützing made significant scientific contributio ...

and Theodor Schwann used microscopes to study yeasts and concluded that yeasts were living organisms. In 1839, Justus von Liebig

Justus Freiherr von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 20 April 1873) was a German scientist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry. As a professor at t ...

, Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) HonFRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the firs ...

and Jöns Jacob Berzelius stated that yeast was not an organism and was produced when air acted on plant juice.

In 1855, Antoine Béchamp

Pierre Jacques Antoine Béchamp (16 October 1816 – 15 April 1908) was a French scientist now best known for breakthroughs in applied organic chemistry and for a bitter rivalry with Louis Pasteur.

Béchamp developed the Béchamp reduction ...

, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Montpellier

The University of Montpellier (french: Université de Montpellier) is a public research university located in Montpellier, in south-east of France. Established in 1220, the University of Montpellier is one of the oldest universities in the wor ...

, conducted experiments with sucrose solutions and concluded that water was the factor for fermentation. He changed his conclusion in 1858, stating that fermentation was directly related to the growth of moulds, which required air for growth. He regarded himself as the first to show the role of microorganisms in fermentation.

Pasteur started his experiments in 1857 and published his findings in 1858 (April issue of ''Comptes Rendus Chimie'', Béchamp's paper appeared in January issue). Béchamp noted that Pasteur did not bring any novel idea or experiments. On the other hand, Béchamp was probably aware of Pasteur's 1857 preliminary works. With both scientists claiming priority on the discovery, a dispute, extending to several areas, lasted throughout their lives.

However, Béchamp was on the losing side, as the ''BMJ

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origina ...

'' obituary remarked: His name was "associated with bygone controversies as to priority which it would be unprofitable to recall". Béchamp proposed the incorrect theory of microzyme

Zymotic disease was a 19th-century medical term for acute infectious diseases, especially "chief fevers and contagious diseases (e.g. typhus and typhoid fevers, smallpox, scarlet fever, measles, erysipelas, cholera, whooping-cough, diphtheria, e ...

s. According to K. L. Manchester, anti-vivisectionist

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

s and proponents of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or evidence from clinical trials. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alt ...

promoted Béchamp and microzymes, unjustifiably claiming that Pasteur plagiarized Béchamp.

Pasteur thought that succinic acid

Succinic acid () is a dicarboxylic acid with the chemical formula (CH2)2(CO2H)2. The name derives from Latin ''succinum'', meaning amber. In living organisms, succinic acid takes the form of an anion, succinate, which has multiple biological ro ...

inverted sucrose. In 1860, Marcellin Berthelot

Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot (; 25 October 1827 – 18 March 1907) was a French chemist and Republican politician noted for the ThomsenBerthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substa ...

isolated invertase

Invertase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis (breakdown) of sucrose (table sugar) into fructose and glucose. Alternative names for invertase include , saccharase, glucosucrase, beta-h-fructosidase, beta-fructosidase, invertin, sucrase, m ...

and showed that succinic acid did not invert sucrose. Pasteur believed that fermentation was only due to living cells. He and Berthelot engaged in a long argument subject of vitalism, in which Berthelot was vehemently opposed to any idea of vitalism. Hans Buchner

Hans Buchner (also Joannes Buchner, Hans von Constanz; born 26 October 1483 in Ravensburg; died March 1538, probably in Konstanz) was an important German organist and composer.

Buchner was a student of Paul Hofhaimer, and may have worked for the ...

discovered that zymase

Zymase is an enzyme complex that catalyzes the fermentation of sugar into ethanol and carbon dioxide. It occurs naturally in yeasts. Zymase activity varies among yeast strains.

Zymase is also the brand name of the drug pancrelipase.

Cell-free ...

catalyzed fermentation, showing that fermentation was catalyzed by enzymes within cells. Eduard Buchner

Eduard Buchner (; 20 May 1860 – 13 August 1917) was a German chemist and zymologist, awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on fermentation.

Biography

Early years

Buchner was born in Munich to a physician and Doctor Extraor ...

also discovered that fermentation could take place outside living cells.

Anthrax vaccine

Pasteur publicly claimed his success in developing the anthrax vaccine in 1881. However, his admirer-turned-rival Henry Toussaint was the one who developed the first vaccine. Toussaint isolated the bacteria that caused chicken cholera (later named ''Pasteurella

__NOTOC__

''Pasteurella'' is a genus of Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. ''Pasteurella'' species are nonmotile and pleomorphic, and often exhibit bipolar staining ("safety pin" appearance). Most species are catalase- and oxidase ...

'' in honour of Pasteur) in 1879 and gave samples to Pasteur who used them for his own works. On 12 July 1880, Toussaint presented his successful result to the French Academy of Sciences, using an attenuated vaccine against anthrax in dogs and sheep. Pasteur on grounds of jealousy contested the discovery by publicly displaying his vaccination method at Pouilly-le-Fort on 5 May 1881. Pasteur then gave a misleading account of the preparation of the anthrax vaccine used in the experiment. He claimed that he made a "live vaccine", but used potassium dichromate to inactivate anthrax spores, a method similar to Toussaint's. The promotional experiment was a success and helped Pasteur sell his products, getting the benefits and glory.

Experimental ethics

Pasteur's experiments are often cited as againstmedical ethics

Medical ethics is an applied branch of ethics which analyzes the practice of clinical medicine and related scientific research. Medical ethics is based on a set of values that professionals can refer to in the case of any confusion or conflict. T ...

, especially on his vaccination of Meister. He did not have any experience in medical practice, and more importantly, lacked a medical license

A medical license is an occupational license that permits a person to legally practice medicine. In most countries, a person must have a medical license bestowed either by a specified government-approved professional association or a governme ...

. This is often cited as a serious threat to his professional and personal reputation. His closest partner Émile Roux

Pierre Paul Émile Roux FRS (17 December 18533 November 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist. Roux was one of the closest collaborators of Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), a co-founder of the Pasteur Institute, and respon ...

, who had medical qualifications, refused to participate in the clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, dietar ...

, likely because he considered it unjust. However, Pasteur executed vaccination of the boy under the close watch of practising physicians Jacques-Joseph Grancher

Jacques-Joseph Grancher (; 29 September 1843 in Felletin, Creuse – 13 July 1907) was a French pediatrician born in Felletin.

In 1862 he began his medical studies in Paris, where he worked as an assistant at the Hôpital des Enfants Malade ...

, head of the Paris Children's Hospital's paediatric clinic, and Alfred Vulpian

Edmé Félix Alfred Vulpian (5 January 1826 – 18 May 1887) was a French physician and neurologist. He was the co-discoverer of Vulpian-Bernhardt spinal muscular atrophy and the Vulpian-Heidenhain-Sherrington phenomenon.

Vulpian was born in Par ...

, a member of the Commission on Rabies. He was not allowed to hold the syringe, although the inoculations were entirely under his supervision. It was Grancher who was responsible for the injections, and he defended Pasteur before the French National Academy of Medicine in the issue.

Pasteur has also been criticized for keeping secrecy of his procedure and not giving proper pre-clinical trials on animals. Pasteur stated that he kept his procedure secret in order to control its quality. He later disclosed his procedures to a small group of scientists. Pasteur wrote that he had successfully vaccinated 50 rabid dogs before using it on Meister. According to Geison, Pasteur's laboratory notebooks show that he had vaccinated only 11 dogs.

Meister never showed any symptoms of rabies, but the vaccination has not been proved to be the reason. One source estimates the probability of Meister contracting rabies at 10%.

Awards and honours

Pasteur was awarded 1,500franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (Style of the French sovereign, King of the Franks) used on early France, ...

s in 1853 by the Pharmaceutical Society for the synthesis of racemic acid

Racemic acid is an old name for an optically inactive or racemic form of tartaric acid. It is an equal mixture of two mirror-image isomers ( enantiomers), optically active in opposing directions. It occurs naturally in grape juice.

Tartaric aci ...

. In 1856 the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of London presented him the Rumford Medal for his discovery of the nature of racemic acid and its relations to polarized light, and the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

in 1874 for his work on fermentation. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1869.

The French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

awarded Pasteur the 1859 Montyon Prize

The Montyon Prize (french: Prix Montyon) is a series of prizes awarded annually by the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie française. They are endowed by the French benefactor Baron de Montyon.

History

Prior to the start of the French R ...

for experimental physiology in 1860, and the Jecker Prize in 1861 and the Alhumbert Prize in 1862 for his experimental refutation of spontaneous generation. Though he lost elections in 1857 and 1861 for membership to the French Academy of Sciences, he won the 1862 election for membership to the mineralogy section. He was elected to permanent secretary of the physical science section of the academy in 1887 and held the position until 1889.

In 1873, Pasteur was elected to the Académie Nationale de Médecine and was made the commander in the Brazilian Order of the Rose

The Imperial Order of the Rose ( pt, Imperial Ordem da Rosa) was a Brazilian order of chivalry, instituted by Emperor Pedro I of Brazil on 17 October 1829 to commemorate his marriage to Amélie of Leuchtenberg.

On 22 March 1890, the order was can ...

. In 1881 he was elected to a seat at the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

left vacant by Émile Littré

Émile Maximilien Paul Littré (; 1 February 18012 June 1881) was a French lexicographer, freemason and philosopher, best known for his '' Dictionnaire de la langue française'', commonly called .

Biography

Littré was born in Paris. His fathe ...

. Pasteur received the Albert Medal from the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

in 1882. In 1883 he became foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

. In 1885, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. On 8 June 1886, the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II awarded Pasteur with the Order of the Medjidie

Order of the Medjidie ( ota, نشانِ مجیدی, August 29, 1852 – 1922) is a military and civilian order of the Ottoman Empire. The Order was instituted in 1851 by Sultan Abdulmejid I.

History

Instituted in 1851, the Order was awarded in f ...

(I Class) and 10000 Ottoman liras. He was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh in 1889. Pasteur won the Leeuwenhoek Medal

The Leeuwenhoek Medal, established in 1877 by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), in honor of the 17th- and 18th-century microscopist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, is granted every ten years to the scientist judged to have made t ...

from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

for his contributions to microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

in 1895.

Pasteur was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

in 1853, promoted to Officer in 1863, to Commander in 1868, to Grand Officer in 1878 and made a Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor in 1881.

Legacy

Palo Alto