Lois Weber on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Florence Lois Weber (June 13, 1879 – November 13, 1939) was an American

Dictionary of Women Worldwide

Film historian Anthony Slide has also asserted, "Along with D.W.Griffith, Weber was the American cinema's first genuine

"'24': Split Screen's Big Comeback"

Salon.com (May 15, 2002). In collaboration with her first husband,

''The Silenced Woman of Silent Films: Why Lois Weber Has Not Been Rediscovered''

, michelebeverly.com; accessed December 19, 2016. and in 1917 the first American woman director to own her own film studio.Cari Beauchamp, ''Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood'' (University of California Press, 1998): 35-36, 41, 112, 149, 193, 282-83, 346. During the war years, Weber "achieved tremendous success by combining a canny commercial sense with a rare vision of cinema as a moral tool".Richard Koszarski, ''An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928'' (University of California Press, 1994): 223. At her zenith, "few men, before or since, have retained such absolute control over the films they have directedand certainly no women directors have achieved the all-embracing, powerful status once held by Lois Weber". By 1920, Weber was considered the "premier woman director of the screen and author and producer of the biggest money making features in the history of the film business". Among Weber's notable films are: the controversial ''

Lois Weber profile

highbeam.com; accessed December 19, 2016. who had spent several years in missionary street work. She was the younger sister of Elizabeth Snaman Weber Jay and older sister of Ethel Weber Howland, who later appeared in two of Weber's films in 1916 and married Weber was considered a

Weber was considered a

For five years Weber was a repertory and stock actress. After short stint as a

For five years Weber was a repertory and stock actress. After short stint as a

''Den hvide slavehandel''

(1910), and for telephone conversations."''Suspense''

In late 1913, Weber and Smalley made '' The Jew's Christmas'', a three-reel silent film that dramatizes the conflict between traditional Jewish values and American customs and values,

illustrating the challenges of cultural assimilation, especially the generational conflict over

In late 1913, Weber and Smalley made '' The Jew's Christmas'', a three-reel silent film that dramatizes the conflict between traditional Jewish values and American customs and values,

illustrating the challenges of cultural assimilation, especially the generational conflict over

"Energized by

"Energized by  In 1914, Weber made her first major feature, a controversial version of ''

In 1914, Weber made her first major feature, a controversial version of ''

In February 1916, Weber and Smalley were transferred to Universal's Bluebird Photoplays brand, where they made a dozen features, including ''The Dumb Girl of Portici'' (also known as ''Pavlowa''), adapted by Weber from

In February 1916, Weber and Smalley were transferred to Universal's Bluebird Photoplays brand, where they made a dozen features, including ''The Dumb Girl of Portici'' (also known as ''Pavlowa''), adapted by Weber from  In ''

In ''

tcm.com; accessed December 19, 2016. It was banned in Pennsylvania on the grounds that it "tended to debase or corrupt morals", but Universal won a case in ''

''

"Lois Weber and 'The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'"

starts-thursday.com, August 2010. August 6, 2010. Influenced by the recent trial and imprisonment of pioneer birth control advocate

"The Blot"

/ref> Smalley was made

''The Blot'' (film profile)

"Lois Weber in Jazz Age Hollywood"

, ''Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media'': 52. In late December 1921, they were in Rome, with plans to travel to the Orient. Weber and Smalley returned to the United States on April 7, 1922. On June 24, 1922, Weber obtained a divorce secretly from Smalley,"Actress Secretly Divorced", ''Reno Evening Gazette'' (Reno, NV: January 12, 1923): 10. ''Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary'', eds. Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer (Harvard University Press, 1974): 555. who was described as both alcoholic and abusive, but kept him as a friend and companion. Their divorce was made public on January 12, 1923 by the ''

Upon her return to Hollywood, Weber found an "'industry in transition', evident in the fact that

Upon her return to Hollywood, Weber found an "'industry in transition', evident in the fact that

"Exit Flapper, Enter Woman"

findarticles.com; accessed December 19, 2016. In November 1922, Weber returned to Universal, where she directed ''

"Uncle Tom's Cabin (1927)"

''The Motion Picture Review'' (1927), iath.virginia.edu; accessed December 19, 2016. Weber ceased work on ''Sensation Seekers'' and was willing to interrupt her honeymoon to travel to

"'Exit Flapper, Enter Woman,' or Lois Weber in Jazz Age Hollywood"

''Framework'' (Fall 2010). *Stamp, Shelley. ''Lois Weber in Early Hollywood''. University of California Press, May 2015. * ** Pages 52–57 provide overviews and details of several films Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley co-created between 1911 and 1921. These restored films are featured on disc three. *Tibbetts, John C. and James M. Welsh. ''The Encyclopedia of Filmmakers''. Vol. Two. New York, NY: 2002. *Unterburger, Amy L., ed. ''Women Filmmakers & Their Films''. Detroit, MI; New York; and London, 1998.

Lois Weber

at the Women Film Pioneers Project

Literature on Lois Weber

virtual-history.com

mikegrost.com * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Weber, Lois 1879 births 1939 deaths American people of Pennsylvania Dutch descent American film actresses American silent film actresses Actresses from Pittsburgh Silent film directors 20th-century American actresses American women film directors Film producers from Pennsylvania American women screenwriters Writers from Pittsburgh Film directors from Pennsylvania Deaths from ulcers Women film pioneers Screenwriters from Pennsylvania American women film producers 20th-century American women writers 20th-century American screenwriters Burials at Kensico Cemetery

silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, when ...

actress, screenwriter, producer and director. She is identified in some historical references as among "the most important and prolific film directors in the era of silent films"."Lois Weber (1881–1939)", ''Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through the Ages'' (2007)Dictionary of Women Worldwide

Film historian Anthony Slide has also asserted, "Along with D.W.Griffith, Weber was the American cinema's first genuine

auteur

An auteur (; , 'author') is an artist with a distinctive approach, usually a film director whose filmmaking control is so unbounded but personal that the director is likened to the "author" of the film, which thus manifests the director's unique ...

, a filmmaker involved in all aspects of production and one who utilized the motion picture to put across her own ideas and philosophies".Anthony Slide, ''The Silent Feminists'', pp. 29, 151.

Weber produced a body of work which has been compared to Griffith's in both quantity and qualityJennifer Parchesky, "Lois Weber's 'The Blot': Rewriting Melodrama, Reproducing the Middle Class", ''Cinema Journal'' 39:1 (Autumn, 1999):23.

and brought to the screen her concerns for humanity and social justice in an estimated 200 to 400 films, of which as few as twenty have been preserved.Linda Seger, ''When Women Call the Shots: The Developing Power and Influence of Women in Television and Film'' (iUniverse, 2003): 8.

She has been credited by IMDb

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, ...

with directing 135 films, writing 114, and acting in 100.

Weber was "one of the first directors to come to the attention of the censors in Hollywood's early years".Aubrey Malone, ''Censoring Hollywood: Sex and Violence in Film and on the Cutting Room Floor'' (McFarland, 2011): 7.

Weber has been credited with pioneering the use of the split screen

Split screen may refer to:

* Split screen (computing), dividing graphics into adjacent parts

* Split screen (video production), the visible division of the screen

* ''Split Screen'' (TV series), 1997–2001

* Split-Screen Level, a bug in the vid ...

technique to show simultaneous action in her 1913 film ''Suspense

Suspense is a state of mental uncertainty, anxiety, being undecided, or being doubtful. In a dramatic work, suspense is the anticipation of the outcome of a plot or of the solution to an uncertainty, puzzle, or mystery, particularly as it ...

''.Julie Talen"'24': Split Screen's Big Comeback"

Salon.com (May 15, 2002). In collaboration with her first husband,

Phillips Smalley

Wendell Phillips Smalley (August 7, 1865 – May 2, 1939) was an American silent film director and actor.

Biography

Born in Brooklyn, New York, he was the grandson of Wendell Phillips; he was the son of George Washburn Smalley, a war correspon ...

, in 1913 Weber was "one of the first directors to experiment with sound", making the first sound films in the United States.

She was also the first American woman to direct a full-length feature film when she and Smalley directed ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as a ...

'' in 1914,Lisa Singh''The Silenced Woman of Silent Films: Why Lois Weber Has Not Been Rediscovered''

, michelebeverly.com; accessed December 19, 2016. and in 1917 the first American woman director to own her own film studio.Cari Beauchamp, ''Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood'' (University of California Press, 1998): 35-36, 41, 112, 149, 193, 282-83, 346. During the war years, Weber "achieved tremendous success by combining a canny commercial sense with a rare vision of cinema as a moral tool".Richard Koszarski, ''An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928'' (University of California Press, 1994): 223. At her zenith, "few men, before or since, have retained such absolute control over the films they have directedand certainly no women directors have achieved the all-embracing, powerful status once held by Lois Weber". By 1920, Weber was considered the "premier woman director of the screen and author and producer of the biggest money making features in the history of the film business". Among Weber's notable films are: the controversial ''

Hypocrites

Hypocrisy is the practice of engaging in the same behavior or activity for which one criticizes another or the practice of claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one's own behavior does not conform. In moral psychology, it is the ...

'', which featured the first non-pornography

Pornography (often shortened to porn or porno) is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the exclusive purpose of sexual arousal. Primarily intended for adults,

full-frontal female nude scene

In film, nudity may be either graphic or suggestive, such as when a person appears to be naked but is covered by a sheet. Since the birth of film, depictions of any form of sexuality have been controversial, and in the case of most nude scenes ...

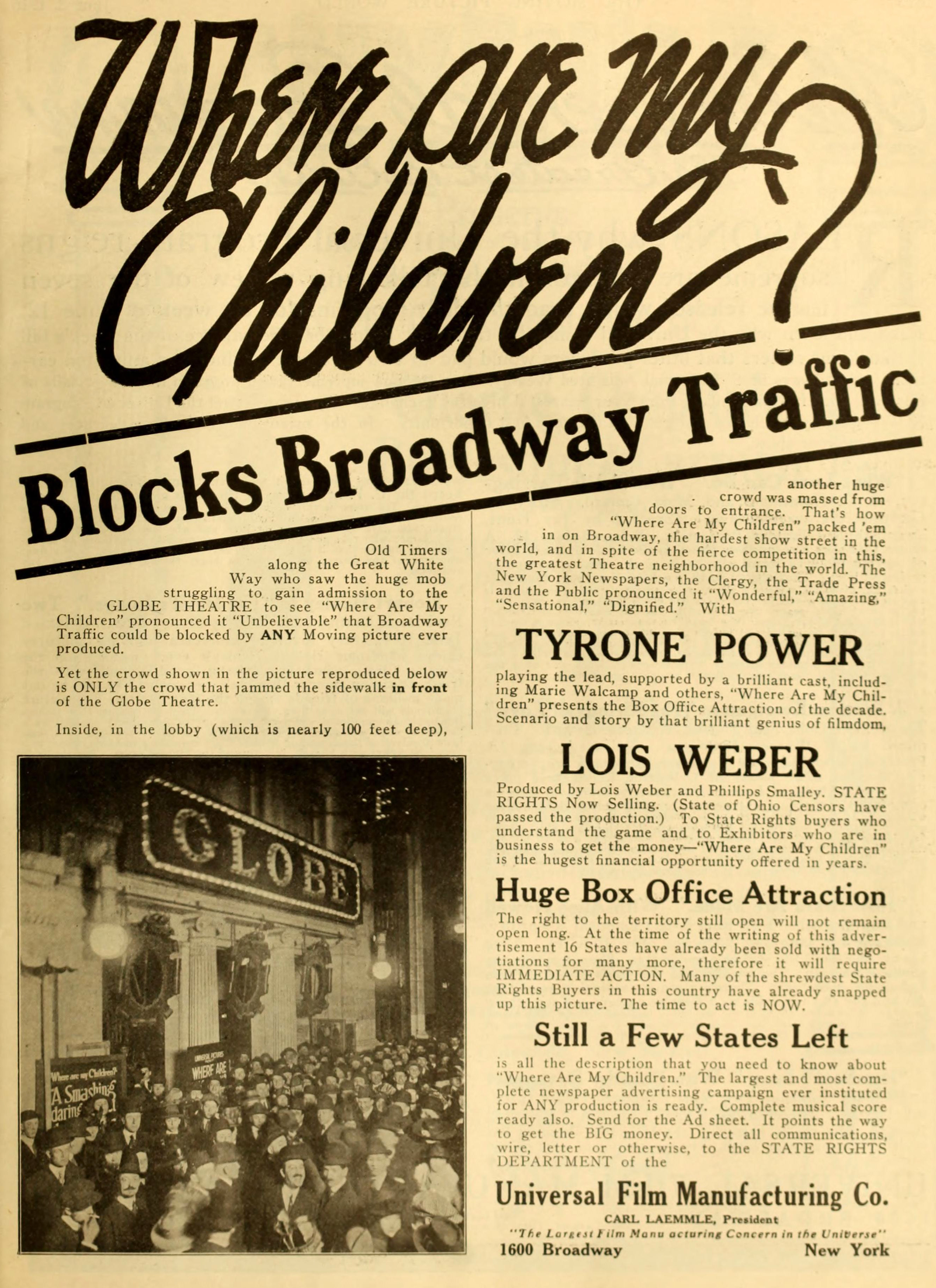

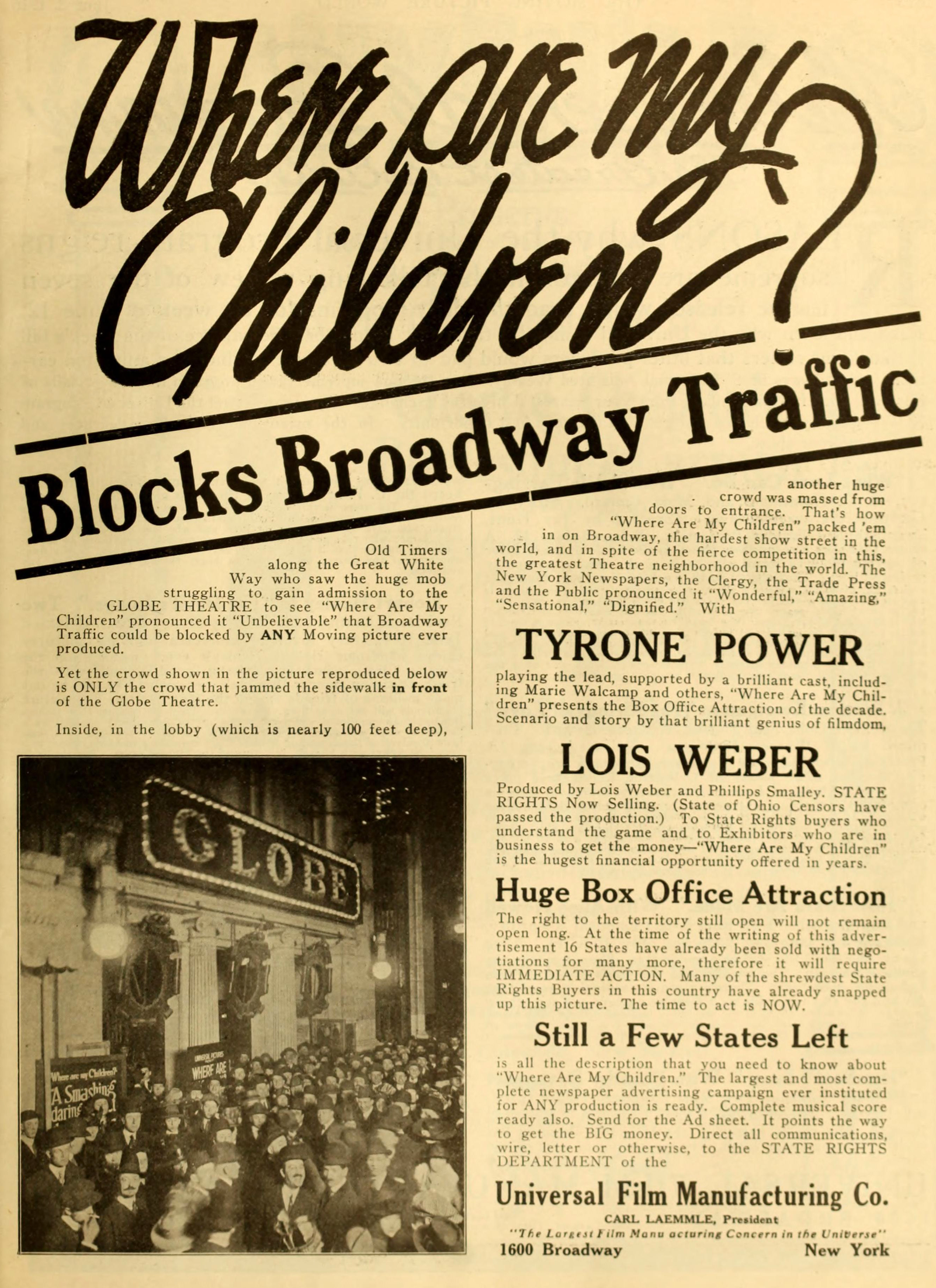

, in 1915; the 1916 film ''Where Are My Children?

''Where Are My Children?'' is a 1916 American silent drama film directed by Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber and stars Tyrone Power Sr., Juan de la Cruz, Helen Riaume, Marie Walcamp, Cora Drew, A.D. Blake, Rene Rogers, William Haben and C. Norman ...

'', which discussed abortion and birth control and was added to the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

in 1993; her adaptation of Edgar Rice Burrough's ''Tarzan of the Apes

''Tarzan of the Apes'' is a 1912 story by American writer Edgar Rice Burroughs, and the first in the Tarzan series. It was first serialized in the pulp magazine '' The All-Story'' beginning October 1912 before being released

as a novel in June 1 ...

'' novel for the very first ''Tarzan of the Apes'' film, in 1918; ''The Blot

''The Blot'' is a 1921 American silent drama film directed by Lois Weber, who also co-wrote (with Marion Orth) and produced the film (with her then-husband, Phillips Smalley). The film tackles the social problem of genteel poverty, focusing on ...

'' (1921) is also generally considered one of her finest works.

Weber is credited with discovering, mentoring, or making stars of several women actors, including Mary MacLaren

Mary MacLaren (born Mary Ida MacDonald, also credited Mary McLaren; January 19, 1900 – November 9, 1985) was an American film actress in both the silent and sound eras."Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population", digital cop ...

,

Mildred Harris

Mildred Harris (April 18, 1901 – July 20, 1944) was an American stage, film, and vaudeville actress during the early part of the 20th century. Harris began her career in the film industry as a child actress when she was 10 years old. She was a ...

, Claire Windsor

Claire Windsor (born Clara Viola Cronk; April 14, 1892 – October 24, 1972) was an American film actress of the silent screen era.

Early life

Windsor was born Clara Viola Cronk (nicknamed "Ola") in 1892 in Marvin, Phillips County, Kansas to ...

,

Esther Ralston

Esther Ralston (born Esther Louise Worth, September 17, 1902 – January 14, 1994) was an iconic American silent film star. Her most prominent sound picture was '' To the Last Man'' in 1933.

Early life and career

Ralston was born Esther Loui ...

,

Billie Dove

Lillian Bohny (born Bertha Eugenie Bohny; May 14, 1903 – December 31, 1997), known professionally as Billie Dove, was an American actress.

Early life and career

Dove was born Bertha Eugenie Bohny in New York City in 1903 to Charles and Ber ...

,

Ella Hall

Ella Augusta Hall (March 17, 1896 – September 3, 1981) was an American actress. She appeared in more than 90 films between 1912 and 1933.

Early years

Ella Augusta Hall was born in Hoboken, New Jersey on March 17, 1896. Her family moved t ...

, Cleo Ridgely

Cleo Ridgely-Horne (born Freda Cleo Helwig, May 12, 1893 – August 18, 1962) was a star of silent and sound motion pictures. Her career began early in the silent film era, in 1911, and continued for forty years. She retired in the 1930s bu ...

,Harrison Carroll, "The Film Shop", ''Tyrone Daily Herald'' (Tyrone, PA: February 4, 1933): 4.

and Anita Stewart

Anita Stewart (born Anna Marie Stewart; February 7, 1895 – May 4, 1961) was an American actress and film producer of the early silent film era.

Early years

Anita Stewart was born in Brooklyn, New York as Anna Marie Stewart on February 7, 18 ...

,

and with discovering and inspiring screenwriter Frances Marion

Frances Marion (born Marion Benson Owens, November 18, 1888 – May 12, 1973) was an American screenwriter, director, journalist and author often cited as one of the most renowned female screenwriters of the 20th century alongside June Mathis ...

. For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Weber was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, California ...

on February 8, 1960.

Early life

Florence Lois Weber was born on June 13, 1879,United States of America, Bureau of the Census. ''Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900''. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls. Source Citation: Year: 1900; Census Place: Allegheny Ward 2, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: T623_1355; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 17. ''Tenth Census of the United States, 1880''. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Source Citation: Year: 1880; Census Place: Allegheny, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1086; Family History Film: 1255086; Page: 339B; Enumeration District: 13; Image: 0686 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, the second of three children of Mary Matilda Snaman and George Weber, an upholster and decorator"Lois Weber", ''Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia'' (January 1, 2002Lois Weber profile

highbeam.com; accessed December 19, 2016. who had spent several years in missionary street work. She was the younger sister of Elizabeth Snaman Weber Jay and older sister of Ethel Weber Howland, who later appeared in two of Weber's films in 1916 and married

assistant director

The role of an assistant director on a film includes tracking daily progress against the filming production schedule, arranging logistics, preparing daily call sheets, checking cast and crew, and maintaining order on the set. They also have to t ...

Louis A. Howland.

The Webers were a devout middle class Christian family of Pennsylvania German

The Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

ancestry.Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008): 89.Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, ''California and Californians'', Vol. 4, ed. Rockwell Dennis Hunt (The Lewis publishing company, 1930): 176.

Weber was considered a

Weber was considered a child prodigy

A child prodigy is defined in psychology research literature as a person under the age of ten who produces meaningful output in some domain at the level of an adult expert. The term is also applied more broadly to young people who are extraor ...

Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, ''Women Film Directors: An International Bio-critical Dictionary'' (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995):365. and an excellent pianist.

As a girl, music was her passion, and her most treasured possession was a baby grand piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

.Carolyn Lowrey, ''The First One Hundred Noted Men and Women of the Screen'' (Moffat, Yard and company, 1920): 190.

Weber left home and lived in poverty while working as a street-corner evangelist

Evangelist may refer to:

Religion

* Four Evangelists, the authors of the canonical Christian Gospels

* Evangelism, publicly preaching the Gospel with the intention of spreading the teachings of Jesus Christ

* Evangelist (Anglican Church), a co ...

and social activist for two years with the evangelical Church Army Workers, an organization similar to the Salvation Army

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

, preaching and singing hymns on street corners and singing and playing the organ in rescue missions in red-light district

A red-light district or pleasure district is a part of an urban area where a concentration of prostitution and sex-oriented businesses, such as sex shops, strip clubs, and adult theaters, are found. In most cases, red-light districts are partic ...

s in Pittsburgh and New York, until the Church Army Workers disbanded in 1900.Daniel Eagan, ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry'' (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010): 50.

In June 1900, Weber was almost 21 and living with her parents and two sisters at 1717 Fremont Street, Allegheny, Pennsylvania

Allegheny City was a municipality that existed in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania from 1788 until it was annexed by Pittsburgh in 1907. It was located north across the Allegheny River from downtown Pittsburgh, with its southwest border formed by ...

, where she was a music student.

By April 1903, Weber was performing as a soprano singer and pianist.

She toured the United States as a concert pianist

until her final performance in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint ...

, a year later. After a piano key broke during a recital,

Weber retired from the concert stage, having lost her nerve to play in public.

Theater career

Frustrated by the futility of one-on-one conversions, and following the advice of an uncle in Chicago, Weber decided to take up acting about 1904, and moved to New York City, where she took some singing lessons. Weber later explained her motivation: "As I was convinced the theatrical profession needed a missionary, he suggested that the best way to reach them was to become one of them so I went on the stage filled with a great desire to convert my fellowman". For five years Weber was a repertory and stock actress. After short stint as a

For five years Weber was a repertory and stock actress. After short stint as a soubrette

A soubrette is a type of operatic soprano voice ''fach'', often cast as a female stock character in opera and theatre. The term arrived in English from Provençal via French, and means "conceited" or "coy".

Theatre

In theatre, a soubrette is a c ...

in the farce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical humor; the use of deliberate absurdity or ...

comedy "Zig-Zag" for a Chicago-based touring company, Weber resigned as it "proved too superficial for her altruistic

Altruism is the principle and moral practice of concern for the welfare and/or happiness of other human beings or animals, resulting in a quality of life both material and spiritual. It is a traditional virtue in many cultures and a core as ...

aims".

In 1904, Weber joined the road company of "Why Girls Leave Home", where she became "a musical comedy

Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, movement ...

''prima donna

In opera or commedia dell'arte, a prima donna (; Italian for "first lady"; plural: ''prime donne'') is the leading female singer in the company, the person to whom the prime roles would be given.

''Prime donne'' often had grand off-stage per ...

'' and melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exce ...

heroine".

Weber received "promising reviews" for her performance;Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008): 90.

for example, ''The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' wrote in September 1904 that she "sang two very pretty songs very effectively and won considerable applause".

The troupe's leading man and manager was Wendell Phillips Smalley (1865–1939), a grandson of Oliver Wendell Holmes, and the elder son of ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' war and foreign correspondent

A correspondent or on-the-scene reporter is usually a journalist or commentator for a magazine, or an agent who contributes reports to a newspaper, or radio or television news, or another type of company, from a remote, often distant, locati ...

George Washburn Smalley (1833-1916) and Phoebe Garnaut Phillips (1841-1923),

the adopted daughter of abolitionist Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one w ...

.

Smalley, who had attended Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

and was a graduate of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, had been a lawyer in New York for seven years, and as a stage actor made his professional stage debut in August 1901 in Manhattan.

He appeared in productions of Harrison Grey Fiske

Harrison Grey Fiske (July 30, 1861 – September 2, 1942) was an American journalist, playwright and Broadway producer who fought against the monopoly of the Theatrical Syndicate, a management company that dominated American stage bookings ...

, Minnie Maddern Fiske

Minnie Maddern Fiske (born Marie Augusta Davey; December 19, 1865 – February 15, 1932), but often billed simply as Mrs. Fiske, was one of the leading American actresses of the late 19th and early 20th century. She also spearheaded the fig ...

, and Raymond Hitchcock.

After a brief acquaintance, just before her 25th birthday, Weber and Smalley, aged 38, married on April 29, 1904 in Chicago, Illinois.

After initially touring separately from her husband, and then accompanying him on his tours, about 1906 Weber left her career in the theater and became a homemaker in New York."Lois Weber", ''Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia'', ed. Philip C. Dimare (ABC-CLIO, 2011): 850.

During this period Weber wrote freelance moving picture scenarios.

Film career

In 1908, Weber was hired by American Gaumont Chronophones, which produced '' phonoscènes'',Alison McMahan, ''Alice Guy Blaché: Lost Visionary of the Cinema'' (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2002): 71. initially as a singer of songs recorded for thechronophone The Chronophone is an apparatus patented by Léon Gaumont in 1902 to synchronise the Cinématographe (Chrono-Bioscope) with a disc Phonograph (Cyclophone) using a "Conductor" or "Switchboard". This sound-on-disc display was used as an experiment ...

.Jennifer M. Bean and Diane Negra, ''A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema'' (Duke University Press, 2002): 46-48, 270, 167-69, 271–86.

Both Herbert Blaché

Herbert Blaché (5 October 1882 – 23 October 1953), born Herbert Reginald Gaston Blaché-Bolton was a British-born American film director, producer and screenwriter, born of a French father. He directed more than 50 films between 1912 and ...

and his wife, Alice Guy

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

, later claimed to have given Weber her start in the movie industry.

At the end of the 1908 theatrical season, Smalley joined Weber at Gaumont. Soon Weber was writing scripts, and in 1908 Weber began directing English language ''phonoscènes'' at the Gaumont Studio in Flushing, New York

Flushing is a neighborhood in the north-central portion of the New York City borough of Queens. The neighborhood is the fourth-largest central business district in New York City. Downtown Flushing is a major commercial and retail area, and the ...

.

In 1910, Weber and Smalley decided to pursue a career in the infant motion picture industry

The film industry or motion picture industry comprises the technological and commercial institutions of filmmaking, i.e., film production companies, film studios, cinematography, animation, film production, screenwriting, pre-production, post p ...

. For the next five years, they worked and were credited as The Smalleys (but typically Weber received sole writing credit) on dozens of shorts and features for small production companies like Gaumont, the New York Motion Picture Co., Reliance Studio, the Rex Motion Picture Company, and Bosworth,

where Weber wrote scenarios

In the performing arts, a scenario (, ; ; ) is a synoptical collage of an event or series of actions and events. In the ''commedia dell'arte'', it was an outline of entrances, exits, and action describing the plot of a play, and was literally pi ...

and subtitles

Subtitles and captions are lines of dialogue or other text displayed at the bottom of the screen in films, television programs, video games or other visual media. They can be transcriptions of the screenplay, translations of it, or informati ...

, acted, directed, designed sets and costumes

Costume is the distinctive style of dress or cosmetic of an individual or group that reflects class, gender, profession, ethnicity, nationality, activity or epoch. In short costume is a cultural visual of the people.

The term also was tradition ...

, edited films, and even developed negatives. Weber took two years off her birth date when she signed her first movie contract.

Weber and Smalley had a daughter, Phoebe (named after Smalley's mother), who was born on October 29, 1910, but died in infancy.

Rex Motion Picture Company

By 1911, Weber and Smalley were working for William Swanson's Rex Motion Picture Company, based at 573–579 11th Avenue, New York City. While at Rex, Weber gained her reputation as "a serious social uplifter and as the leading partner in the Weber-Smalley unit." In 1911, Weber acted in and directed her first silent short film, '' A Heroine of '76'', sharing the directorial duties with Smalley andEdwin S. Porter

Edwin Stanton Porter (April 21, 1870 – April 30, 1941) was an American film pioneer, most famous as a producer, director, studio manager and cinematographer with the Edison Manufacturing Company and the Famous Players Film Company. Of over 2 ...

.

At the time of Rex's merger with five other studios to form the Universal Film Manufacturing Company

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

on April 30, 1912, Weber and Smalley were the "prima facie

''Prima facie'' (; ) is a Latin expression meaning ''at first sight'' or ''based on first impression''. The literal translation would be 'at first face' or 'at first appearance', from the feminine forms of ''primus'' ('first') and ''facies'' (' ...

heads of Rex",

and had relocated to Los Angeles.

Rex continued as a subsidiary of Universal, with Weber and Smalley running it, making one two-reel film each week, until they left Rex in September 1912.

Carl Laemmle

Carl Laemmle (; born Karl Lämmle; January 17, 1867 – September 24, 1939) was a film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures. He produced or worked on over 400 films.

Regarded as one of the most important o ...

startled the film industry with his use of and advocacy for women directors and producers, including Weber, Ida May Park

Ida May Park (December 28, 1879 – June 13, 1954) was an American screenwriter and film director of the silent era, in the early 20th century. She wrote for more than 50 films between 1914 and 1930, and directed 14 films between 1917 and 19 ...

and Cleo Madison.

In the autumn of 1913, shortly after the incorporation of Universal City,Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008):188.

Weber was elected its first mayor in a close contest that required a recount,

and Laura Oakley as police chief.

At the time, Universal's publicity department claimed Universal City was "the only municipality in the world that possesses an entire outfit of women officials".

In March 1913, Weber starred in the first English language version of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

's ''The Picture of Dorian Gray

''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is a philosophical novel by Irish writer Oscar Wilde. A shorter novella-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American periodical ''Lippincott's Monthly Magazine''.''The Picture of Dorian Gra ...

'', which was produced for the New York Motion Picture Co., directed by Smalley from an adaptation by Weber, and featuring Wallace Reid

William Wallace Halleck Reid (April 15, 1891 – January 18, 1923) was an American actor in silent film, referred to as "the screen's most perfect lover". He also had a brief career as a racing driver.

Early life

Reid was born in St. Louis, M ...

as Dorian Gray.

In 1913, Weber and Smalley collaborated in directing a ten-minute thriller, ''Suspense

Suspense is a state of mental uncertainty, anxiety, being undecided, or being doubtful. In a dramatic work, suspense is the anticipation of the outcome of a plot or of the solution to an uncertainty, puzzle, or mystery, particularly as it ...

'', based on the play ''Au Telephone'' by André de Lorde

André de Latour, comte de Lorde (1869–1942) was a French playwright, the main author of the Grand Guignol plays from 1901 to 1926. His evening career was as a dramatist of terror; during daytimes he worked as a librarian in the Bibliothèque d ...

, which had been filmed in 1908 as ''Heard over the 'Phone'' by Edwin S. Porter.

Adapted by Weber, it used multiple images and mirror shots to tell of a woman (Weber) threatened by a burglar ( Sam Kaufman).

Weber is credited with pioneering the use of the split screen

Split screen may refer to:

* Split screen (computing), dividing graphics into adjacent parts

* Split screen (video production), the visible division of the screen

* ''Split Screen'' (TV series), 1997–2001

* Split-Screen Level, a bug in the vid ...

technique to show simultaneous action in this film, but the "oft-mentioned triptych

A triptych ( ; from the Greek adjective ''τρίπτυχον'' "''triptukhon''" ("three-fold"), from ''tri'', i.e., "three" and ''ptysso'', i.e., "to fold" or ''ptyx'', i.e., "fold") is a work of art (usually a panel painting) that is divided ...

shots had already been used in the Danish "The White Slave Trade" films''Den hvide slavehandel''

(1910), and for telephone conversations."''Suspense''

IMDb

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, ...

According to Tom Gunning,

Professor Emeritus in the Department of Cinema and Media at the University of Chicago, and author of ''D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film'', "No film made before WWI shows a stronger command of film style than ''Suspense'' hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

outdoes even Griffith for emotionally involved filmmaking".

''Suspense'' was released on July 6, 1913.

In late 1913, Weber and Smalley made '' The Jew's Christmas'', a three-reel silent film that dramatizes the conflict between traditional Jewish values and American customs and values,

illustrating the challenges of cultural assimilation, especially the generational conflict over

In late 1913, Weber and Smalley made '' The Jew's Christmas'', a three-reel silent film that dramatizes the conflict between traditional Jewish values and American customs and values,

illustrating the challenges of cultural assimilation, especially the generational conflict over interfaith marriage

Interfaith marriage, sometimes called a "mixed marriage", is marriage between spouses professing different religions. Although interfaith marriages are often established as civil marriages, in some instances they may be established as a religiou ...

and the second generation's abandonment of the faith and customs of their ancestors.

In "the earliest portrayal of a rabbi in an American film",

''The Jew's Christmas'' told the story of an orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

(Smalley) who ostracizes his daughter (Weber) for marrying a gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym for ...

, but is reconciled twelve years later on Christmas Eve when he meets an impoverished small child, who turns out to be his granddaughter.

Endeavoring to combat racial discrimination and antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, the film aims to show that love is stronger than any religious ties,

and that "the tie of blood overbears the pride and prejudice of religion".Patricia Erens' ''The Jew in American Cinema'' (Indiana University Press, 1988): pp. 46-47.

In its assertion of "Melting-pot idealism" by its approval of intermarriage between people of different religions,

the film was considered controversial at the time of its release

on December 18, 1913.

In 1914, a year in which she directed 27 movies, Weber became "one of the first directors to come to the attention of the censors". That year, Weber co-directed an adaptation of Shakespeare's ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as a ...

'' with Smalley, who also played Shylock. making her the first American woman to direct a feature-length film in the United States,

and the first person who "directed the first feature-length Shakespearean comedy".

In February 1914, Universal released the four-reel Rex silent film

which was also adapted by Weber and Smalley,

and was also produced, directed, and starred Weber as Portia, and Smalley as Shylock. The film featured Douglas Gerrard

Douglas Gerrard (12 August 1891 – 5 June 1950) was an Irish-American actor and film director of the silent and early sound era. He appeared in more than 110 films between 1913 and 1949. He also directed 23 films between 1916 and 1920. He ...

, Rupert Julian

Rupert Julian (born Thomas Percival Hayes; 25 January 1879 – 27 December 1943) was a New Zealand cinema actor, director, writer and producer. During his career, Julian directed 60 films and acted in over 90 films. He is best remembered for di ...

, and Jeanie MacPherson

Abbie Jean MacPherson (May 18, 1886 – August 26, 1946) was an American silent actress, writer, and director. MacPherson worked as a theater and film actress before becoming a screenwriter for Cecil B. DeMille. She was a pioneer for women in th ...

, who would play a major role in cinema as Cecil B. DeMille's favorite screenwriter.

A "prominent rabbi in Chicago strongly objected on the grounds that the play 'more than any other book, more than any other influence in the history of the world, is responsible for the world-wide prejudice against the Jews'",Robert Hamilton Ball, ''Shakespeare on Silent Film: A Strange Eventful History, Volume 1968'', Part 2 (Allen & Unwin, 1968): 208.

but the film was praised at the time as "a supreme adaptation of Shakespeare". Robert Hamilton Ball considered the film "careful, respectful, dignified, but lacking in passion and poetry", which he attributes to the difficulty it had satisfying the censor, and because the film was a special release rather than a release on the regular programme, exhibitors had to pay extra for it, which may have contributed to its swift demise. ''The Merchant of Venice'' is now considered a lost film

A lost film is a feature or short film that no longer exists in any studio archive, private collection, public archive or the U.S. Library of Congress.

Conditions

During most of the 20th century, U.S. copyright law required at least one copy o ...

.

One film that illustrates the paradoxical nature of Weber's role and films was her 1914 film ''The Spider and Her Web'', where she advocates both modesty and maternalism. In this film, Weber plays "The Spider", a vamp

The VaMP driverless car was one of the first truly autonomous cars Dynamic Vision for Perc ...

living the "ultra-modern high life" who seduces and ruins intellectual men until frightened into adopting an orphan baby, which results in the salvation of the lead character through motherhood.

Bosworth

As Universal was reluctant to make feature-length films,Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008): 90-92. in the summer of 1914 Weber was persuaded to move to the Bosworth company byJulia Crawford Ivers

Julia Crawford Ivers (October 3, 1869 – May 8, 1930) was an American motion picture pioneer.

Biography

Born in Boonville, Missouri, in 1869, her family arrived a year later in Los Angeles. Her father was a dentist. Her mother died in 1876, whe ...

, the first woman general manager of a film studio,

to take over the production duties from Hobart Bosworth

on a $50,000 a year contract, making her "the best known, most respected and highest-paid" of the dozen or so women directors in Hollywood at that time.

In 1914, Bertha Smith estimated Weber's audience at five to six million a week.

In fact, by 1915 Weber was as famous as D.W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the n ...

and Cecil B. de Mille.

While at Bosworth, Weber and Smalley made six features and one short, ''The Traitor''.Mark Garrett Cooper, ''Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood'' (University of Illinois Press, 2010): 132.

"Energized by

"Energized by evangelistic

In Christianity, evangelism (or witnessing) is the act of preaching the gospel with the intention of sharing the message and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Christians who specialize in evangelism are often known as evangelists, whether they are in ...

zeal and social conscience",

from early in her career Weber saw movies as "a vehicle for evangelism",

and "an opportunity to preach to the masses",Daniel Eagan, ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry'' (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010): 51.

and to encourage her audience to be involved in progressive causes.

In a 1914 interview Weber declared: "In moving pictures I have found my life's work. I find at once an outlet for my emotions and my ideals. I can preach to my heart's content, and with the opportunity to write the play, act the leading role, and direct the entire production, if my message fails to reach someone, I can blame only myself."

As many of Weber's films focused on a moral topic, she "was often mistaken as a Christian fundamentalist

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

, but she was more of a libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's enc ...

, opposing censorship and the death penalty and championing birth control. The need for a strong, loving and nurturing home was clearly promoted as well and if there was a single maxim that underlay each film it was that selfishness and egocentricity erode the individual and community".

Although not a practicing Christian Scientist

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally know ...

,

Weber attended the Christian Science church regularly, according to Adela Rogers St. Johns

Adela Nora Rogers St. Johns (May 20, 1894 – August 10, 1988) was an American journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. She wrote a number of screenplays for silent movies but is best remembered for her groundbreaking exploits as "The World's Grea ...

,

and, in at least two of her films, ''Jewel'' (1915) and its remake, ''A Chapter in Her Life

''A Chapter in Her Life'' is a 1923 American drama film based on the novel ''Jewel: A Chapter in Her Life'' by Clara Louise Burnham. The film was directed by Lois Weber. She had previously adapted the same novel as the 1915 film ''Jewel'', which ...

'' (1923), Christian Science plays a prominent role.

Weber's impeccable reputation and "impressive middle-class credentials" allowed her considerable artistic freedom in her presentation of controversial issues.

In 1914, Weber made her first major feature, a controversial version of ''

In 1914, Weber made her first major feature, a controversial version of ''Hypocrites

Hypocrisy is the practice of engaging in the same behavior or activity for which one criticizes another or the practice of claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one's own behavior does not conform. In moral psychology, it is the ...

'', a four-reel allegorical drama shot at Universal City which she wrote, directed and produced, addressing social themes and moral lessons considered daring for the time. ''Hypocrites'' included the first film full-frontal female nudity

Nudity is the state of being in which a human is without clothing.

The loss of body hair was one of the physical characteristics that marked the biological evolution of modern humans from their hominin ancestors. Adaptations related to ...

, inspired by Jules Joseph Lefebvre

Jules Joseph Lefebvre (; 14 March 183624 February 1911) was a French figure painter, educator and theorist.

Early life

Lefebvre was born in Tournan-en-Brie, Seine-et-Marne, on 14 March 1836. He entered the École nationale supérieure des Bea ...

's 1870 allegorical painting ''La Vérité'', with truth portrayed in the ghostly figure of the Naked Truth, literally shown by an unidentified nude woman (Margaret Edwards).

Margaret Sinclair Edwards (born 1877, New York City – died January 14, 1929, New York City), known on the stage as "Daisy Sinclair", appeared with the theatrical companies of Edward Harrigan

Edward Harrigan (October 26, 1844June 6, 1911), sometimes called Ned Harrigan, was an Irish-American actor, singer, dancer, playwright, lyricist and theater producer who, together with Tony Hart (as Harrigan & Hart), formed one of the most celebr ...

, Eddie Foy, and Gus Edwards, among others. Her husband, John Edwards, an invalid, died the same year she did (1929). She appeared as Marguerite Edwards in ''A Physical Culture Romance'' in 1914, and in Weber's ''Sunshine Molly'' in 1915.

Although the nudity was tastefully done (it was passed by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures

The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures is a non-profit organization of New York City area film enthusiasts. Its awards, which are announced in early December, are considered an early harbinger of the film awards season that culminat ...

after a two-month delay),Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008): 96. it was still banned

A ban is a formal or informal prohibition of something. Bans are formed for the prohibition of activities within a certain political territory. Some bans in commerce are referred to as embargoes. ''Ban'' is also used as a verb similar in meanin ...

in Ohio; caused riots in New York; and James Michael Curley

James Michael Curley (November 20, 1874 – November 12, 1958) was an American Democratic politician from Boston, Massachusetts. He served four terms as mayor of Boston. He also served a single term as governor of Massachusetts, characterized ...

, the mayor of Boston, demanded that every frame displaying the naked figure of Truth be hand-painted to clothe the then unidentified actress.

''Hypocrites'' was released finally by Bosworth on January 15, 1915, and premiered at Manhattan's prestigious Longacre Theatre

The Longacre Theatre is a Broadway theater at 220 West 48th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, United States. Opened in 1913, it was designed by Henry B. Herts and was named for Longacre Square, now known a ...

, and was "celebrated as a cultural, artistic, and moral landmark for the film industry", and "praised for its use of multiple exposures and complex film editing".

While its negative cost

Negative cost is the net expense to produce and shoot a film, excluding such expenditures as distribution and promotion

Promotion may refer to:

Marketing

* Promotion (marketing), one of the four marketing mix elements, comprising any type of ...

was $18,000, it earned $119,000 in sales in the United States alone and made Weber "a household name".

In a 1917 interview, Weber denied the film was indecent and defended the film: "Hypocrites is not a slap at any church or creed – it is a slap at hypocrites, and its effectiveness is shown by the outcry amongst those it hits hardest, to have the film stopped".

Universal

In April 1915, Weber and Smalley left Bosworth whenthe founder

''The Founder'' is a 2016 American biographical drama film directed by John Lee Hancock and written by Robert Siegel. Starring Michael Keaton as businessman Ray Kroc, the film portrays the story of his creation of the McDonald's fast-food res ...

left the company due to ill health. After being promised they could make feature-length films by Carl Laemmle

Carl Laemmle (; born Karl Lämmle; January 17, 1867 – September 24, 1939) was a film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures. He produced or worked on over 400 films.

Regarded as one of the most important o ...

, they returned to Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

.

Weber's first movie for Universal was ''Scandal'', in which both Weber and Smalley starred, that featured the consequences of gossip mongering.

In 1916, Weber directed 10 feature-length films for release by Universal, nine of which she also wrote, and she also became Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

' highest-paid director, earning $5,000 a week. She "enjoyed complete freedom in overseeing most stages of the film-making process – choice of stories and actors, writing of scripts (which she invariably did herself), as well as direction".Annette Kuhn, ''Cinema, Censorship, and Sexuality, 1909–1925'' (Taylor & Francis, 1988):28.

Universal head Carl Laemmle, "who was known more for his frugality and cunning business sense than philanthropy", said of Weber: "I would trust Miss Weber with any sum of money that she needed to make any picture that she wanted to make. I would be sure that she would bring it back."

In 1916, Weber explained her philosophy of directing films: "I'll never be convinced that the general public does not want serious entertainment rather than frivolous", and "A real director should be absolute. He (or she in this case) alone knows the effects he wants to produce, and he alone should have authority in the arrangement, cutting, titling or anything else that may seem necessary to do to the finished product. What other artist has his work interfered with by someone else?... We ought to realize that the work of a picture director, worthy of a name, is creative".

Bluebird Photoplays

In February 1916, Weber and Smalley were transferred to Universal's Bluebird Photoplays brand, where they made a dozen features, including ''The Dumb Girl of Portici'' (also known as ''Pavlowa''), adapted by Weber from

In February 1916, Weber and Smalley were transferred to Universal's Bluebird Photoplays brand, where they made a dozen features, including ''The Dumb Girl of Portici'' (also known as ''Pavlowa''), adapted by Weber from Daniel Auber

Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (; 29 January 178212 May 1871) was a French composer and director of the Paris Conservatoire.

Born into an artistic family, Auber was at first an amateur composer before he took up writing operas professionally when ...

's 1828 opera ''La muette de Portici

''La muette de Portici'' (''The Mute Girl of Portici'', or ''The Dumb Girl of Portici''), also called ''Masaniello'' () in some versions, is an opera in five acts by Daniel Auber, with a libretto by Germain Delavigne, revised by Eugène Scribe. ...

'',

Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlovna Pavlova ( , rus, Анна Павловна Павлова ), born Anna Matveyevna Pavlova ( rus, Анна Матвеевна Павлова; – 23 January 1931), was a Russian prima ballerina of the late 19th and the early 20th ...

's only screen appearance,

which was directed to Pavlova's satisfaction by Weber. The film also starred Rupert Julian

Rupert Julian (born Thomas Percival Hayes; 25 January 1879 – 27 December 1943) was a New Zealand cinema actor, director, writer and producer. During his career, Julian directed 60 films and acted in over 90 films. He is best remembered for di ...

as Masaniello

Masaniello (, ; an abbreviation of Tommaso Aniello; 29 June 1620 – 16 July 1647) was an Italian fisherman who became leader of the 1647 revolt against the rule of Habsburg Spain in the Kingdom of Naples.

Name and place of birth

Until recen ...

.

Released to popular acclaim, it premiered on April 3, 1916 at the Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, on land owned by Thomas Brend and inherited by his son, Nicholas Brend, and gr ...

in Manhattan.

Hoping to "become the editorial page of the studio", and to "provoke a middle-class sense of responsibility for those less fortunate than themselves, and to stimulate moral reforms",

Weber specialized in making films that stressed both high quality and moral rectitude, including films of the "burning social and moral issues of the day", among them such controversial themes as abortion, eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, and birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

in ''Where Are My Children?

''Where Are My Children?'' is a 1916 American silent drama film directed by Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber and stars Tyrone Power Sr., Juan de la Cruz, Helen Riaume, Marie Walcamp, Cora Drew, A.D. Blake, Rene Rogers, William Haben and C. Norman ...

'' (1916), influenced by the trial of Charles Stielow, an innocent man who was almost executed, opposition to capital punishment based on circumstantial evidence

Circumstantial evidence is evidence that relies on an inference to connect it to a conclusion of fact—such as a fingerprint at the scene of a crime. By contrast, direct evidence supports the truth of an assertion directly—i.e., without need f ...

in '' The People vs. John Doe''; and alcoholism and opium addiction

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

in '' Hop, the Devil's Brew'', which were all successful at the box office, but, while embraced by reformers in the film industry, "drew the ire of the conservatives".

Despite the predominance of strong women in her films, in 1916 Weber disassociated herself from the women's suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.

In ''

In ''Where Are My Children?

''Where Are My Children?'' is a 1916 American silent drama film directed by Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber and stars Tyrone Power Sr., Juan de la Cruz, Helen Riaume, Marie Walcamp, Cora Drew, A.D. Blake, Rene Rogers, William Haben and C. Norman ...

'' (working title

A working title, which may be abbreviated and styled in trade publications after a putative title as (wt), also called a production title or a tentative title, is the temporary title of a product or project used during its development, usually ...

: ''The Illborn''), which was released on April 16, 1916, Weber advocates social purity, birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, and eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

to prevent the "deterioration of the race" and the "proliferation of the lower classes", and makes "an indirect case for birth control or perhaps even for legalized, and safe, abortions".

The film starred Tyrone Power, Sr. and his then-wife Helen Riaume; future star Mary MacLaren

Mary MacLaren (born Mary Ida MacDonald, also credited Mary McLaren; January 19, 1900 – November 9, 1985) was an American film actress in both the silent and sound eras."Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population", digital cop ...

made her debut. It also makes use of several trick photography

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual ...

scenes, with an emphasis on multiple exposure

In photography and cinematography, a multiple exposure is the superimposition of two or more exposures to create a single image, and double exposure has a corresponding meaning in respect of two images. The exposure values may or may not be id ...

s to convey information or emotions visually. As a recurring motif, every time a character becomes pregnant, a child's face is double exposed over their shoulder.

In March 1916, the National Board of Review

The National Board of Review of Motion Pictures is a non-profit organization of New York City area film enthusiasts. Its awards, which are announced in early December, are considered an early harbinger of the film awards season that culminat ...

expressed disapproval of the film for showings to mixed audiences, but later approved it for adult showings.''Where Are My Children?'' notes"tcm.com; accessed December 19, 2016. It was banned in Pennsylvania on the grounds that it "tended to debase or corrupt morals", but Universal won a case in

Brooklyn, New York

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, beh ...

in 1916 to show the film after the district attorney filed suit against the theater manager and the Universal exchange president. Controversy, the threat of censorship, and the banning of ''Where Are My Children?'' in some locations helped fuel the box office success of the film, estimated to have grossed in excess of $3 million,"Lois Weber", Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia, ed. Philip C. Dimare (ABC-CLIO, 2011): 850. in an era where ticket prices were less than 50c each, and "rocketed Weber's name to larger audiences, bigger box-office returns, and an even higher annual income".

The film spread Weber's fame internationally. For example, Kevin Brownlow indicates that this film attracted 30,000 in Preston, Lancashire

Preston () is a city on the north bank of the River Ribble in Lancashire, England. The city is the administrative centre of the county of Lancashire and the wider City of Preston local government district. Preston and its surrounding district ...

, 40,000 in Bradford, Yorkshire

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

, and 100,000 in two weeks in Sydney.

In 2000, the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center copyrighted a preservation print reconstructed from several incomplete prints.

''

''Shoes

A shoe is an item of footwear intended to protect and comfort the human foot. They are often worn with a sock. Shoes are also used as an item of decoration and fashion. The design of shoes has varied enormously through time and from culture to ...

'', a "sociological" film released in June 1916 that Weber directed for the Bluebird Photoplays, was based on Stella Wynne Herron's short story of the same name, which had been published in Collier's magazine earlier that year. Herron took inspiration from noted social reformer Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage i ...

's 1912 book ''A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil''.

The nonfiction book depicts the struggles of working-class women for consumer goods and upward mobility

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given socie ...

and their dubious sexual activities, including prostitution.Mark Garrett Cooper, ''Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood'' (University of Illinois Press, 2010): 134.

Starring Mary Maclaren as Eva Meyer, a poverty-stricken shopgirl who supports her family of five, who needs to replace her only pair of shoes, and is so desperate that she sells her virginity for a new pair, it proved to be the most booked Bluebird production of 1916. A version restored digitally from three extant fragments by EYE Film Institute Netherlands

Eye Filmmuseum is a film archive, museum, and cinema in Amsterdam that preserves and presents both Dutch and foreign films screened in the Netherlands.

Location and history

Eye Filmmuseum is located in the Overhoeks neighborhood of Amsterdam in t ...

, made its debut in North America in July 2011.

A scene from the restored "Shoes" showing architect John B. Parkinson's 1910 design for Pershing Square in Downtown Los Angeles has been used by the grassroots Pershing Square Restoration Society in promoting their campaign to restore the historic park.

After another significant censorship battle, and a vigorous publicity campaign by Universal, on May 13, 1917, Universal released ''The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'', "one of the most forceful films ever made in support of legalizing birth control", a follow-up to the previous year's top money-maker for Universal, ''Where Are My Children?'' Directed by Weber and Smalley based on their original script, it starred Smalley and Weber, in her last screen appearance, as a doctor's wife arrested and imprisoned for illegally disseminating family planning information.Shelley Stamp"Lois Weber and 'The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'"

starts-thursday.com, August 2010. August 6, 2010. Influenced by the recent trial and imprisonment of pioneer birth control advocate

Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

, the film drew explicitly on her headline-generating activism.

The film was released only weeks after Sanger's own film, ''Birth Control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

'', was banned under a 1915 ruling of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

that films "did not constitute free speech", and the ruling of the New York Court of Appeals that a film on family planning may be censored "in the interest of morality, decency, and public safety and welfare". Sensitive to the opinions of local communities, and hoping to avoid powerful censorship boards in the northeast and midwest, ''The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'' was distributed primarily in the southern and western regions of the United States, with the result that it did not attain the record-breaking attendance set by ''Where Are My Children?'' the previous year. When ''The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'' opened at Clune's Auditorium in Los Angeles in June 1917, Weber appeared on stage, bitterly denouncing attempts to alter or suppress her film. While ''The Hand That Rocks the Cradle'' is now lost, the surviving script and accompanying marketing materials make it clear that Weber mounted an unstinting argument in favor of "voluntary motherhood".

Lois Weber Productions

In June 1917 Weber became the first American female director to establish and run her ownmovie studio

A film studio (also known as movie studio or simply studio) is a major entertainment company or motion picture company that has its own privately owned studio facility or facilities that are used to make films, which is handled by the production ...

when she formed her own production company

A production company, production house, production studio, or a production team is a studio that creates works in the fields of performing arts, new media art, film, television, radio, comics, interactive arts, video games, websites, music, and vi ...

, Lois Weber Productions, with the financial assistance of Universal. She leased a self-contained estate, and had offices, dressing rooms, scenic and property rooms, and a shooting stage constructed.Bret Wood"The Blot"

/ref> Smalley was made

studio manager

Studio manager, studio director, or studio head is a job title in various media-related professions, including design, advertising, and broadcasting.

Design and advertising

A design or advertising studio manager's responsibilities will typically ...

, and the Smalleys made their home on the studio lot at 1550 N. Sierra Bonita Avenue.

According to film historian Shelley Stamp, while Weber and Smalley were often co-credited as directors, it was "the wife who clearly had the artistic vision to drive the business partnership forward". By this time, Weber's "idealized collaborative marriage" with Smalley had begun to show signs of deterioration, which was accelerated by the increased focus of critics and journalists on Weber as the dominant filmmaker, at the expense of Smalley, after 1916, and Weber increasingly took credit for her contributions after 1917. However, as early as 1913, some saw Weber as the "fertile brain" in the partnership, with Smalley seen as an indolent womanizer "who chased every woman on the lot", which resulted in arguments and shouting matches.Karen Ward Mahar, ''Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood'' (JHU Press, 2008): 90-92.

Weber consciously resisted the industry's movement toward assembly-line-style studio film making. "By concentrating on only one production at a time, and mobilizing her entire workforce around that effort, Weber aimed for quality film making rather than efficient bookkeeping". Weber's independence allowed her to shoot her films in sequence, as she preferred (rather than out of order to suit production schedules). William D. Routt indicates that "Lois Weber Productions were a good investment, cost-effective. The company made movies cheaply: in later years at least shooting on location even for interiors, using a small cast, working fast. Its somewhat sensational topics and titles guaranteed at least a modest box office return, and at times may have done much better than that."

Karen Mahar attributes the success of Weber's films of the 1910s to their representation of "the generational conflict of the era" between the traditional view of women and that of the freedoms of the emerging "New Woman

The New Woman was a feminism, feminist ideal that emerged first wave feminism, in the late 19th century and had a profound influence well into the 20th century. In 1894, Irish writer Sarah Grand (1854–1943) used the term "new woman" in an inf ...

and the emergent consumer culture". Mahar argues that "Weber's life was an expression of this generational divide: she was a stage performer and a Church Army Worker, a filmmaker and a middle-class matron, a childless advocate of birth control who 'radiates domesticity'". While Weber was clearly a New Woman by virtue of her career, she was also publicly identified as the wife and collaborator of her first husband.

Shelley Stamp argues that Weber's "image was instrumental in defining both her particular place in film-making practices, and women's roles within early Hollywood generally", and that her "wifely, bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

persona, relatively conservative and staid, mirrored the film industry's idealized conception of its new customers: white, married, middle-class women perceived to be arbiters of taste in their communities".

While Weber's beliefs reflected modern values, as did her career as a filmmaker that was atypical for women of her era, she had "internalized much of what the Victorians deemed proper behavior for women", and there are "strong elements of the Victorian code of womanhood in her films".Lisa L. Rudman, "Marriage: The Ideal and the Reel: Or, the Cinematic Marriage Manual", ''Film History'' 1:4 (1987): 327.

The Smalleys exemplified and promoted the Victorian ideal of marriage as companionship and a partnership.

In 1917, Weber was the only woman granted membership in the Motion Picture Directors Association The Motion Picture Directors Association (MPDA) was an American non-profit fraternal organization formed by 26 film directors on June 18, 1915, in Los Angeles, California. The organization selected a headquarters to be built there in 1921.

Its art ...

, and from 1917 Weber was active in supporting the newly established Hollywood Studio Club, a residence for struggling would-be starlet

Starlet may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Starlet'' (film), a 2012 independent dramatic film directed by Sean Baker

* ''The Starlet'', reality TV show

* The Starlets, a girl group

Transport

* Toyota Starlet, a car produced between 1973 and ...

s.

After the United States entered World War I, Weber served on the board of the Motion Picture War Service Association, headed by D. W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the n ...

and including Mack Sennett

Mack Sennett (born Michael Sinnott; January 17, 1880 – November 5, 1960) was a Canadian-American film actor, director, and producer, and studio head, known as the 'King of Comedy'.

Born in Danville, Quebec, in 1880, he started in films in th ...

, Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

, Mary Pickford

Gladys Marie Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian-American stage and screen actress and producer with a career that spanned five decades. A pioneer in the US film industry, she co-founde ...

, Douglas Fairbanks

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Sr. (born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman; May 23, 1883 – December 12, 1939) was an American actor, screenwriter, director, and producer. He was best known for his swashbuckling roles in silent films including '' The Thi ...

, William S. Hart

William Surrey Hart (December 6, 1864 – June 23, 1946) was an American silent film actor, screenwriter, director and producer. He is remembered as a foremost Western star of the silent era who "imbued all of his characters with honor and inte ...

, Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American film director, producer and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of the American cinem ...

, and William Desmond Taylor

William Desmond Taylor (born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner, 26 April 1872 – 1 February 1922) was an Anglo-Irish-American film director and actor. A popular figure in the growing Cinema of the United States, Hollywood motion picture colony o ...