The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide

intergovernmental organisation

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states an ...

whose principal mission was to maintain

world peace

World peace, or peace on Earth, is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Planet Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would ...

. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the

Paris Peace Conference that ended the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The main organization ceased operations on 20 April 1946 but many of its components were relocated into the new

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

.

The League's primary goals were stated in

its Covenant. They included preventing wars through

collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

and

disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such as ...

and settling international disputes through negotiation and

arbitration. Its other concerns included labour conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants,

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

and

drug trafficking

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via insuffla ...

, the arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe. The

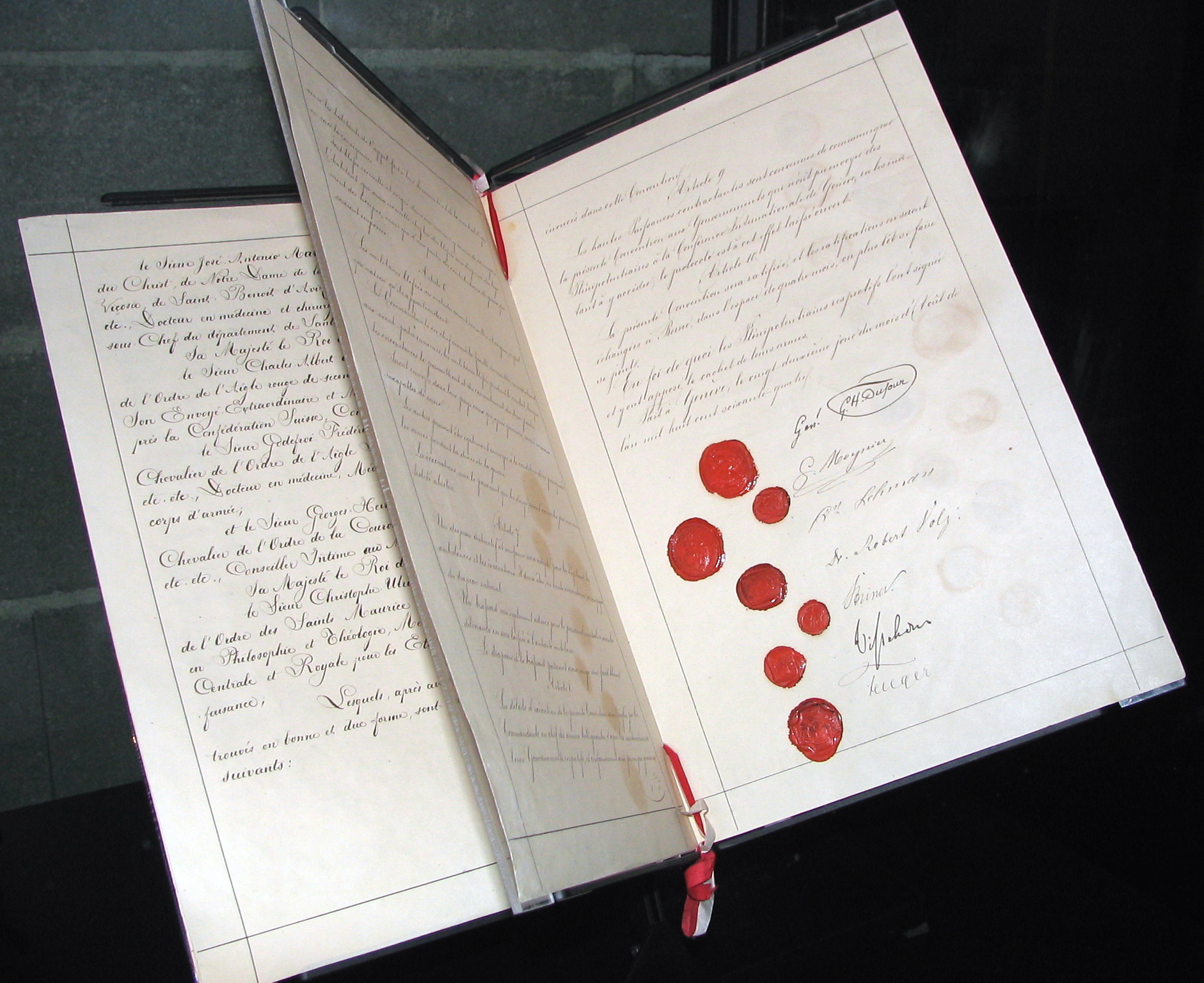

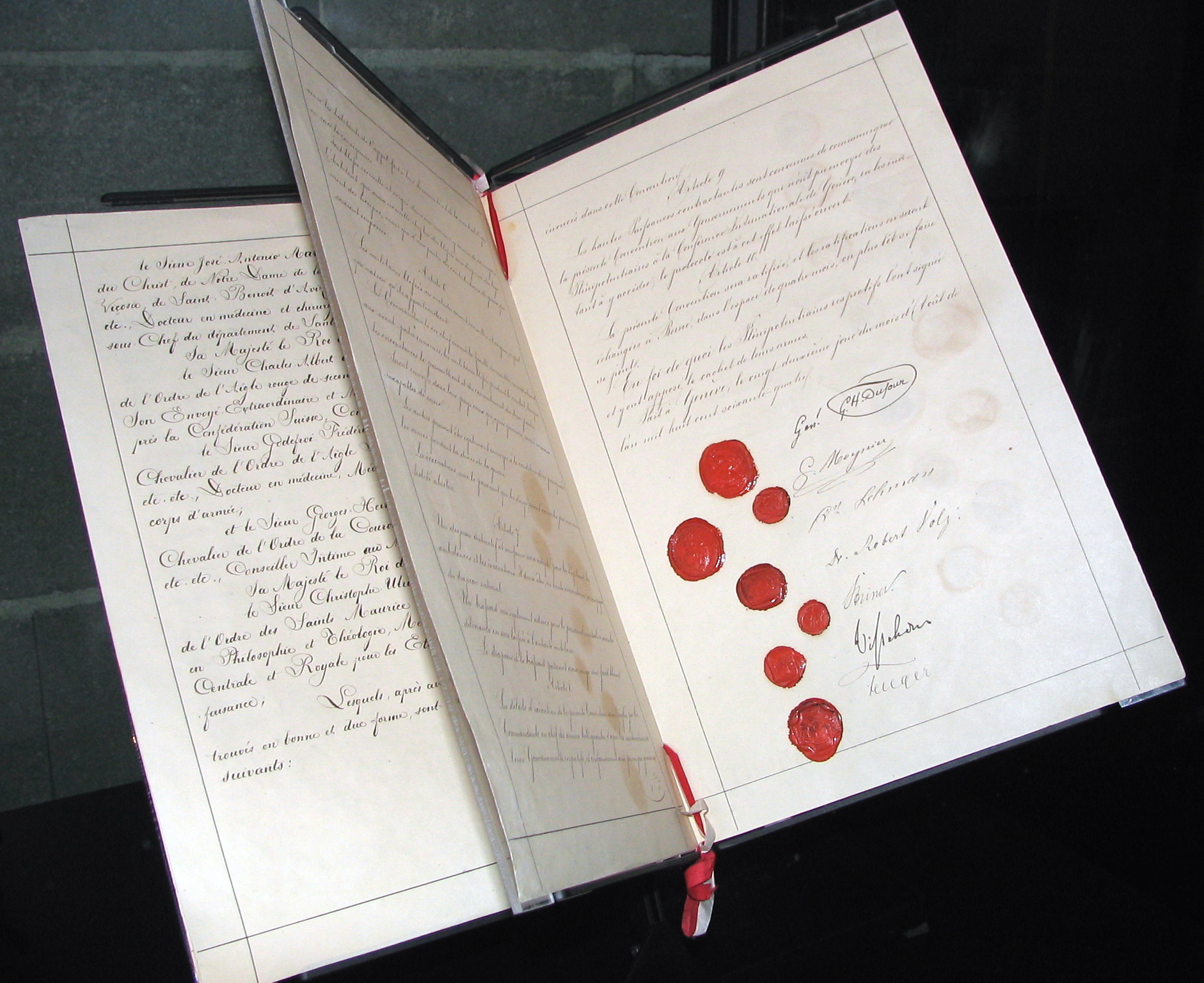

Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, and it became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920. The first meeting of the Council of the League took place on 16 January 1920, and the first meeting of Assembly of the League took place on 15 November 1920. In 1919 U.S. president

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

won the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

for his role as the leading architect of the League.

The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift from the preceding hundred years. The League lacked its own armed force and depended on the victorious

First World War Allies (Britain, France, Italy and Japan were the permanent members of the Executive Council) to enforce its resolutions, keep to its economic sanctions, or provide an army when needed. The

Great Powers were often reluctant to do so. Sanctions could hurt League members, so they were reluctant to comply with them. During the

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

, when the League accused Italian soldiers of targeting

International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement medical tents,

Benito Mussolini responded that "the League is very well when sparrows shout, but no good at all when eagles fall out."

At its greatest extent from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 members. After some notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s, the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in the 1930s. The credibility of the organization was weakened by the fact that the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

never joined, and Japan, Italy, Germany and Spain quit. The

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

joined late and was expelled after

invading Finland. The onset of the

Second World War in 1939 showed that the League had failed its primary purpose; it was inactive until its abolition. The League lasted for 26 years; the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN) replaced it in 1946 and inherited several agencies and organisations founded by the League.

Current scholarly consensus views that, even though the League failed to achieve its main goal of world peace, it did manage to build new roads towards expanding the

rule of law across the globe; strengthened the concept of

collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

, giving a voice to smaller nations; helped to raise awareness to problems like

epidemics

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

,

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

,

child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

, colonial tyranny,

refugee crises and general working conditions through its numerous commissions and committees; and paved the way for new forms of statehood, as the

mandate system

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

put the colonial powers under international observation.

Professor

David Kennedy portrays the League as a unique moment when international affairs were "institutionalised", as opposed to the pre–First World War methods of law and politics.

Origins

Background

The concept of a peaceful community of nations had been proposed as early as 1795, when

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

's ''

Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch'' outlined the idea of a league of nations to control conflict and promote peace between states. Kant argued for the establishment of a peaceful world community, not in a sense of a global government, but in the hope that each state would declare itself a free state that respects its citizens and welcomes foreign visitors as fellow rational beings, thus promoting peaceful society worldwide. International co-operation to promote collective security originated in the

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

that developed after the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in the 19th century in an attempt to maintain the ''status quo'' between European states and so avoid war.

By 1910 international law developed, with the first

Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

establishing laws dealing with humanitarian relief during wartime, and the international

Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 governing rules of war and the peaceful settlement of international disputes.

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

at the acceptance for his Nobel Prize in 1910, said: "it would be a masterstroke if those great powers honestly bent on peace would form a League of Peace."

One small forerunner of the League of Nations, the

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), was formed by the peace activists

William Randal Cremer

Sir William Randal Cremer (18 March 1828 – 22 July 1908) usually known by his middle name "Randal", was a British Liberal Member of Parliament, a pacifist, and a leading advocate for international arbitration. He was awarded the Nobel Peace P ...

and

Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy (20 May 182212 June 1912) was a French economist and pacifist who was a founding member of several peace societies and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also an author and politician, sitting in the Chamber of Deputies fr ...

in 1889 (and is currently still in existence as an international body with a focus on the various elected legislative bodies of the world). The IPU was founded with an international scope, with a third of the members of parliaments (in the 24 countries that had parliaments) serving as members of the IPU by 1914. Its foundational aims were to encourage governments to solve international disputes by peaceful means. Annual conferences were established to help governments refine the process of international arbitration. Its structure was designed as a council headed by a president, which would later be reflected in the structure of the League.

Plans and proposals

At the start of the First World War, the first schemes for an international organisation to prevent future wars began to gain considerable public support, particularly in Great Britain and the United States.

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (6 August 1862 – 3 August 1932), known as Goldie, was a British political scientist and philosopher. He lived most of his life at Cambridge, where he wrote a dissertation on Neoplatonism before becoming a fellow. H ...

, a British political scientist, coined the term "League of Nations" in 1914 and drafted a scheme for its organisation. Together with

Lord Bryce

James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce, (10 May 1838 – 22 January 1922), was a British academic, jurist, historian, and Liberal politician. According to Keoth Robbins, he was a widely-traveled authority on law, government, and history whose expe ...

, he played a leading role in the founding of the group of internationalist pacifists known as the

Bryce Group The Bryce Group was a loose organisation of British Liberal Party members which was devoted to studying international organisation. The organization was the first to fully flesh out a blueprint for a League of Nations and organize a popular movement ...

, later the

League of Nations Union The League of Nations Union (LNU) was an organization formed in October 1918 in Great Britain to promote international justice, collective security and a permanent peace between nations based upon the ideals of the League of Nations. The League of N ...

.

The group became steadily more influential among the public and as a pressure group within the then-governing

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

. In Dickinson's 1915 pamphlet ''After the War'' he wrote of his "League of Peace" as being essentially an organisation for arbitration and conciliation. He felt that the secret diplomacy of the early twentieth century had brought about war and thus could write that, "the impossibility of war, I believe, would be increased in proportion as the issues of foreign policy should be known to and controlled by public opinion." The 'Proposals' of the Bryce Group were circulated widely, both in England and the US, where they had a profound influence on the nascent international movement.

In January 1915, a peace conference directed by

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

was held in the neutral United States. The delegates adopted a platform calling for creation of international bodies with administrative and legislative powers to develop a "permanent league of neutral nations" to work for peace and disarmament. Within months, a call was made for an international women's conference to be held in

The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

. Coordinated by

Mia Boissevain

Maria (Mia) Boissevain (1878–1959) was a Dutch malacologist and feminist.

Life

Boissevain was the youngest of nine children. Her father was a shipowner from a rich Huguenot merchant family and her mother was the daughter of a lawyer.

Educati ...

,

Aletta Jacobs

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs (; 9 February 1854 – 10 August 1929) was a Dutch physician and women's suffrage activist. As the first woman officially to attend a Dutch university, she became one of the first female physicians in the Netherlands. I ...

and

Rosa Manus

Rosette Susanna "Rosa" Manus ( was born 20 August 1881 and died either at Auschwitz or Ravensbruck in 1942. She was a Jewish Dutch pacifist and female suffragist and was involved in women's movements and anti-war movements. She served as the ...

, the congress, which opened on 28 April 1915 was attended by 1,136 participants from neutral nations, and resulted in the establishment of an organization which would become the

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

(WILPF). At the close of the conference, two delegations of women were dispatched to meet European heads of state over the next several months. They secured agreement from reluctant foreign ministers, who overall felt that such a body would be ineffective, but agreed to participate in or not impede creation of a neutral mediating body, if other nations agreed and if President

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

would initiate a body. In the midst of the War, Wilson refused.

In 1915, a similar body to the Bryce Group was set up in the United States led by former president

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. It was called the

League to Enforce Peace

The League to Enforce Peace was a non-state American organization established in 1915 to promote the formation of an international body for world peace. It was formed at Independence Hall in Philadelphia by American citizens concerned by the outbr ...

. It advocated the use of arbitration in conflict resolution and the imposition of sanctions on aggressive countries. None of these early organisations envisioned a continuously functioning body; with the exception of the

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

in England, they maintained a legalistic approach that would limit the international body to a court of justice. The Fabians were the first to argue for a "council" of states, necessarily the

Great Power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

s, who would adjudicate world affairs, and for the creation of a permanent secretariat to enhance international co-operation across a range of activities.

In the course of the

diplomatic efforts surrounding World War I, both sides had to clarify their long-term war aims. By 1916 in Britain, fighting on the side of the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, and in the neutral United States, long-range thinkers had begun to design a unified international organisation to prevent future wars. Historian Peter Yearwood argues that when the new coalition government of

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

took power in December 1916, there was widespread discussion among intellectuals and diplomats of the desirability of establishing such an organisation. When Lloyd George was challenged by Wilson to state his position with an eye on the postwar situation, he endorsed such an organisation. Wilson himself included in his

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

in January 1918 a "league of nations to ensure peace and justice." British foreign secretary,

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the ...

, argued that, as a condition of durable peace, "behind international law, and behind all treaty arrangements for preventing or limiting hostilities, some form of international sanction should be devised which would give pause to the hardiest aggressor."

The war had had a profound impact, affecting the social, political and economic systems of Europe and inflicting psychological and physical damage. Several empires collapsed: first the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in February 1917, followed by the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

,

Austro-Hungarian Empire and

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Anti-war sentiment rose across the world; the First World War was described as "

the war to end all wars

"The war to end war" (also "The war to end all wars"; originally from the 1914 book '' The War That Will End War'' by H. G. Wells) is a term for the First World War of 1914–1918. Originally an idealistic slogan, it is now mainly used sardonic ...

", and its possible causes were vigorously investigated. The causes identified included arms races, alliances, militaristic nationalism, secret diplomacy, and the freedom of sovereign states to enter into war for their own benefit. One proposed remedy was the creation of an international organisation whose aim was to prevent future war through disarmament, open diplomacy, international co-operation, restrictions on the right to wage war, and penalties that made war unattractive.

In London Balfour commissioned the first official report into the matter in early 1918, under the initiative of Lord

Robert Cecil. The British committee was finally appointed in February 1918. It was led by

Walter Phillimore (and became known as the Phillimore Committee), but also included

Eyre Crowe

Sir Eyre Alexander Barby Wichart Crowe (30 July 1864 – 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat, an expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is best known for his vehement warning, in 1907, that Germany's expansionism was mo ...

,

William Tyrrell, and

Cecil Hurst

Sir Cecil James Barrington Hurst, Order of St Michael and St George, GCMG, Order of the Bath, KCB, Queen's Counsel, QC (28 October 1870 – 27 March 1963) was a British international lawyer. He worked from 1929 to 1945 as a judge to the Permanent ...

.

The recommendations of the so-called

Phillimore Commission included the establishment of a "Conference of Allied States" that would arbitrate disputes and impose sanctions on offending states. The proposals were approved by the British government, and much of the commission's results were later incorporated into the

Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

.

The French also drafted a much more far-reaching proposal in June 1918; they advocated annual meetings of a council to settle all disputes, as well as an "international army" to enforce its decisions.

American President Woodrow Wilson instructed

Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

to draft a US plan which reflected Wilson's own idealistic views (first articulated in the

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

of January 1918), as well as the work of the Phillimore Commission. The outcome of House's work and Wilson's own first draft proposed the termination of "unethical" state behaviour, including forms of espionage and dishonesty. Methods of compulsion against recalcitrant states would include severe measures, such as "blockading and closing the frontiers of that power to commerce or intercourse with any part of the world and to use any force that may be necessary..."

The two principal drafters and architects of the

covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

were the British politician Lord

Robert Cecil and the South African statesman

Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

. Smuts' proposals included the creation of a council of the great powers as permanent members and a non-permanent selection of the minor states. He also proposed the creation of a

mandate system for captured colonies of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

during the war. Cecil focused on the administrative side and proposed annual council meetings and quadrennial meetings for the Assembly of all members. He also argued for a large and permanent secretariat to carry out the League's administrative duties.

According to Patricia Clavin, Lord Cecil and the British continued their leadership of the development of a rules-based global order into the 1920s and 1930s, with a primary focus on the League of Nations. The British goal was to systematize and normalize the economic and social relations between states, markets, and civil society. They gave priority to business and banking issues, but also considered the needs of ordinary women, children and the family as well. They moved beyond high-level intellectual discussions, and set up local organizations to support the League. The British were particularly active in setting up junior branches for secondary students.

The League of Nations was relatively more universal and inclusive in its membership and structure than previous international organisations, but the organisation enshrined racial hierarchy by curtailing the right to self-determination and prevented decolonization.

Establishment

At the

Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Wilson, Cecil and Smuts all put forward their draft proposals. After lengthy negotiations between the delegates, the

Hurst

Hurst may refer to:

Places England

* Hurst, Berkshire, a village

* Hurst, North Yorkshire, a hamlet

* Hurst, a settlement within the village of Martock, Somerset

* Hurst, West Sussex, a hamlet

* Hurst Spit, a shingle spit in Hampshire

** Hur ...

–

Miller

A miller is a person who operates a mill, a machine to grind a grain (for example corn or wheat) to make flour. Milling is among the oldest of human occupations. "Miller", "Milne" and other variants are common surnames, as are their equivalent ...

draft was finally produced as a basis for the

Covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

. After more negotiation and compromise, the delegates finally approved of the proposal to create the League of Nations (french: Société des Nations, german: Völkerbund) on 25 January 1919. The final

Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

was drafted by a special commission, and the League was established by Part I of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, signed on 28 June 1919.

French women's rights advocates invited international feminists to participate in a parallel conference to the Paris Conference in hopes that they could gain permission to participate in the official conference.

[ ] The

Inter-Allied Women's Conference

The Inter-Allied Women's Conference (also known as the Suffragist Conference of the Allied Countries and the United States) opened in Paris on 10 February 1919. It was convened parallel to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Paris Peace Conferenc ...

asked to be allowed to submit suggestions to the peace negotiations and commissions and were granted the right to sit on commissions dealing specifically with women and children. Though they asked for enfranchisement and full legal protection under the law equal with men,

those rights were ignored. Women won the right to serve in all capacities, including as staff or delegates in the League of Nations organization. They also won a declaration that member nations should prevent

trafficking

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations.

There are various ...

of women and children and should equally support humane conditions for children, women and men labourers. At the

Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

Peace Conference held between 17 and 19 May 1919, the women of the WILPF condemned the terms of the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

for both its punitive measures, as well as its failure to provide for condemnation of violence and exclusion of women from civil and political participation. Upon reading the Rules of Procedure for the League of Nations,

Catherine Marshall

Catherine Sarah Wood Marshall LeSourd (27 September 1914 – 18 March 1983) was an American author of nonfiction, inspirational, and fiction works. She was the wife of well-known minister Peter Marshall.

Biography

Marshall was born in Johnson ...

, a British suffragist, discovered that the guidelines were completely undemocratic and they were modified based on her suggestion.

The League would be made up of a General Assembly (representing all member states), an Executive Council (with membership limited to major powers), and a permanent secretariat. Member states were expected to "respect and preserve as against external aggression" the territorial integrity of other members and to

disarm

"Disarm" is a song by American alternative rock band the Smashing Pumpkins. It was the third single from their second album, ''Siamese Dream'' (1993), and became a top-20 hit in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom despite being banned in ...

"to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety." All states were required to submit complaints for

arbitration or

judicial inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal commission in that ...

before going to war.

The Executive Council would create a

Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

to make judgements on the disputes.

Despite Wilson's efforts to establish and promote the League, for which he was awarded the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

in October 1919, the United States never joined. Senate Republicans led by

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

wanted a League with the reservation that only Congress could take the U.S. into war. Lodge gained a majority of Senators and Wilson refused to allow a compromise. The Senate voted on the ratification on 19 March 1920, and the 49–35 vote fell short of the

needed 2/3 majority.

The League held its first council meeting in Paris on 16 January 1920, six days after the Versailles Treaty and the Covenant of the League of Nations came into force. On 1 November 1920, the headquarters of the League was moved from London to

Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, where the first General Assembly was held on 15 November 1920. The

Palais Wilson

The Palais Wilson (Wilson Palace) in Geneva, Switzerland, is the current headquarters of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. It was also the headquarters of the League of Nations from 1 November 1920 until that bo ...

on Geneva's western lakeshore, named after Woodrow Wilson, was the League's first permanent home.

Mission

The covenant had ambiguities, as Carole Fink points out. There was not a good fit between Wilson's "revolutionary conception of the League as a solid replacement for a corrupt alliance system, a guardian of international order, and protector of small states," versus Lloyd George's desire for a "cheap, self-enforcing, peace, such as had been maintained by the old and more fluid Concert of Europe."

Furthermore, the League, according to Carole Fink, was, "deliberately excluded from such great-power prerogatives as freedom of the seas and naval disarmament, the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

and the internal affairs of the French and British empires, and inter-Allied debts and German reparations, not to mention the Allied intervention and the settlement of borders with Soviet Russia."

Although the United States never joined, unofficial observers became more and more involved, especially in the 1930s. American philanthropies came heavily involved, especially the

Rockefeller Foundation. It made major grants designed to build up the technical expertise of the League staff. Ludovic Tournès argues that by the 1930s the foundations had changed the League from a "Parliament of Nations" to a modern think tank that used specialized expertise to provide in-depth impartial analysis of international issues.

Languages and symbols

The official languages of the League of Nations were French and English.

In 1939, a semi-official emblem for the League of Nations emerged: two five-pointed stars within a blue pentagon. They symbolised the Earth's five continents and "five

races." A bow at the top displayed the English name ("League of Nations"), while another at the bottom showed the French ("''Société des Nations''").

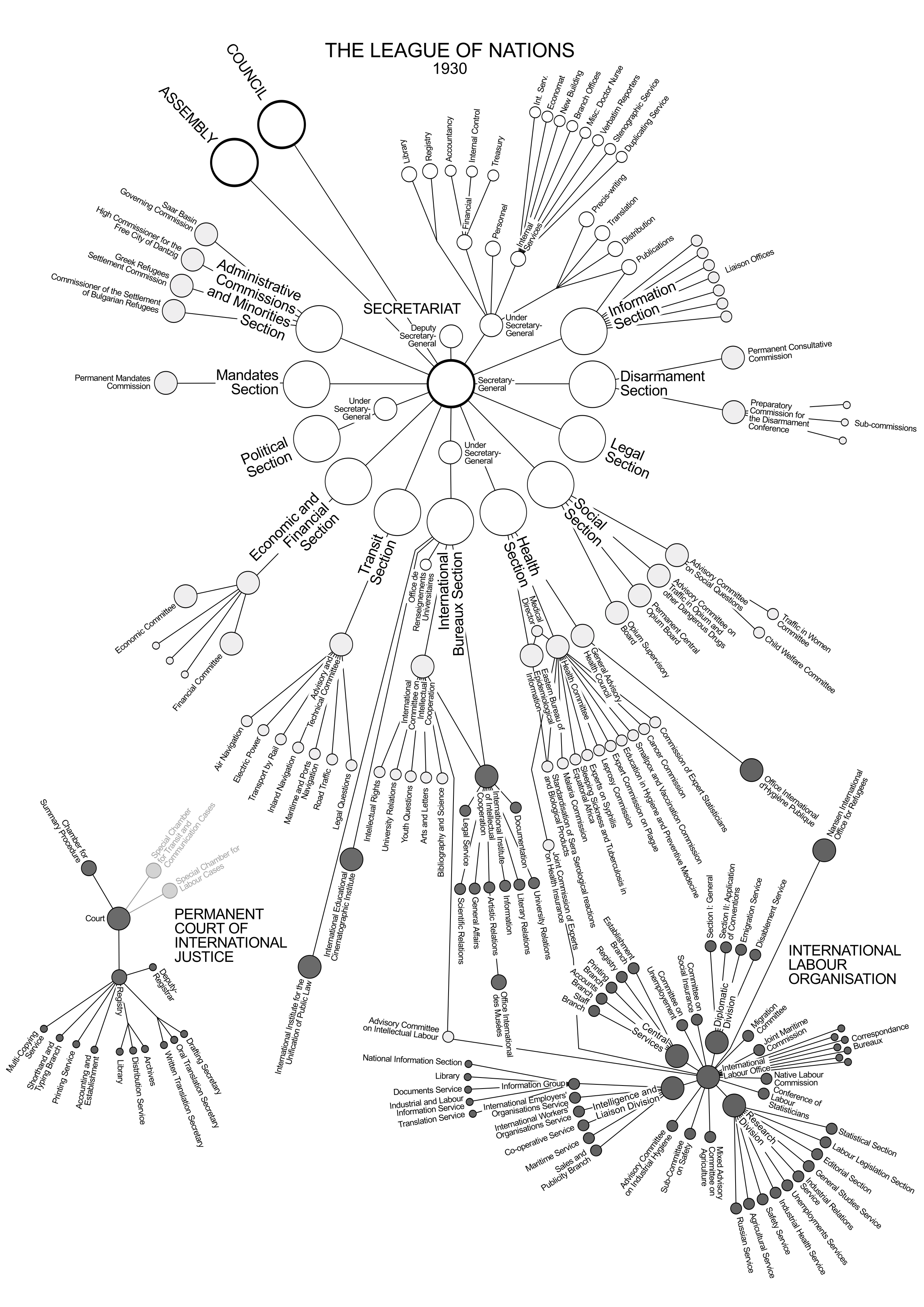

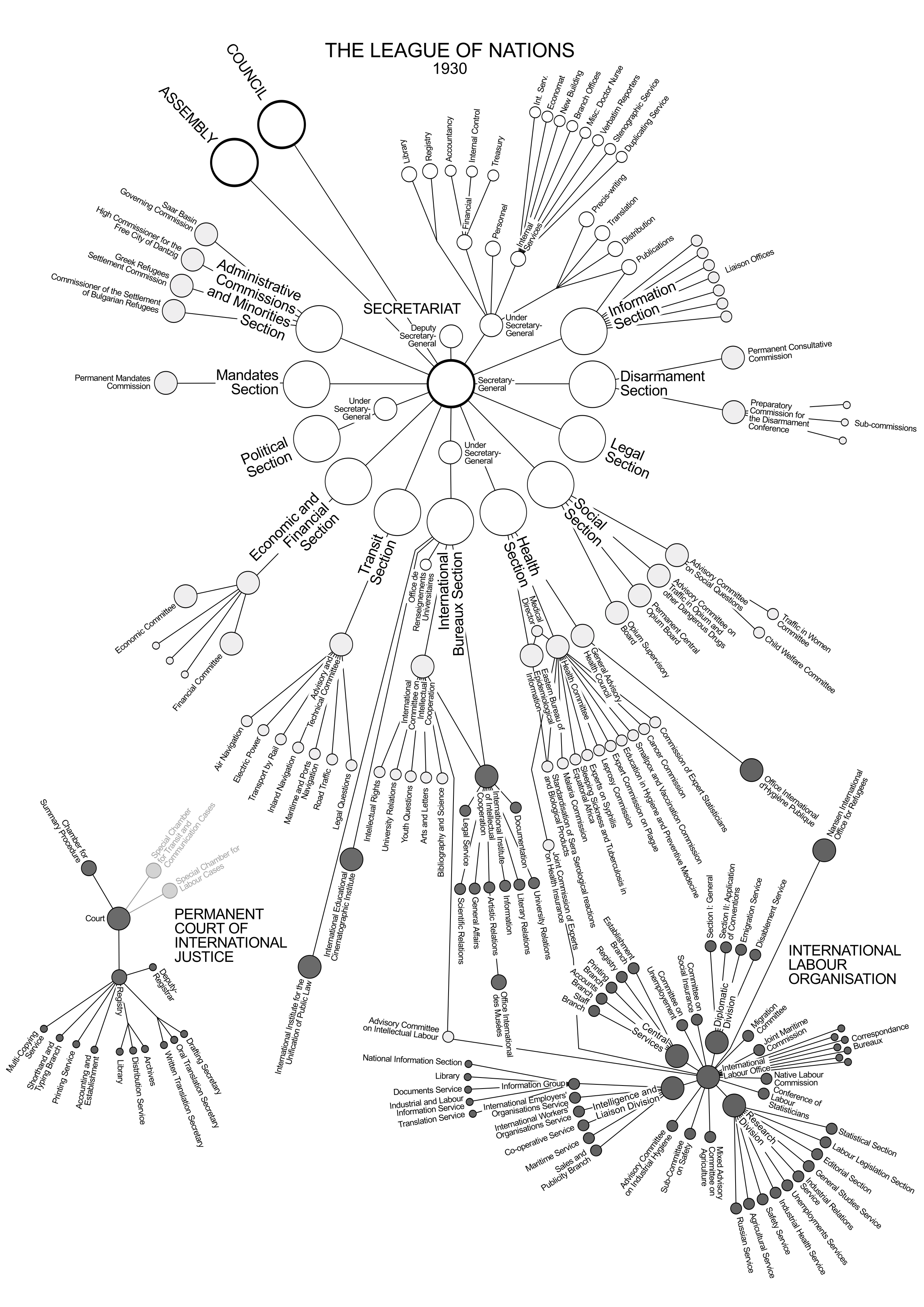

Principal organs

The main constitutional organs of the League were the Assembly, the council, and the Permanent Secretariat. It also had two essential wings: the

Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

and the

International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and o ...

. In addition, there were several auxiliary agencies and commissions. Each organ's budget was allocated by the Assembly (the League was supported financially by its member states).

The relations between the assembly and the council and the competencies of each were for the most part not explicitly defined. Each body could deal with any matter within the sphere of competence of the league or affecting peace in the world. Particular questions or tasks might be referred to either.

Unanimity

Unanimity is agreement by all people in a given situation. Groups may consider unanimous decisions as a sign of social, political or procedural agreement, solidarity, and unity. Unanimity may be assumed explicitly after a unanimous vote or impli ...

was required for the decisions of both the assembly and the council, except in matters of procedure and some other specific cases such as the admission of new members. This requirement was a reflection of the league's belief in the sovereignty of its component nations; the league sought a solution by consent, not by dictation. In case of a dispute, the consent of the parties to the dispute was not required for unanimity.

The Permanent Secretariat, established at the seat of the League at Geneva, comprised a body of experts in various spheres under the direction of the

general secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

. Its principal sections were Political, Financial and Economics, Transit, Minorities and Administration (administering the

Saar

Saar or SAAR has several meanings:

People Given name

*Saar Boubacar (born 1951), Senegalese professional football player

* Saar Ganor, Israeli archaeologist

*Saar Klein (born 1967), American film editor

Surname

* Ain Saar (born 1968), Est ...

and

Danzig), Mandates, Disarmament, Health, Social (Opium and Traffic in Women and Children), Intellectual Cooperation and International Bureaux, Legal, and Information. The staff of the Secretariat was responsible for preparing the agenda for the Council and the Assembly and publishing reports of the meetings and other routine matters, effectively acting as the League's civil service. In 1931 the staff numbered 707.

The Assembly consisted of representatives of all members of the League, with each state allowed up to three representatives and one vote.

It met in Geneva and, after its initial sessions in 1920, it convened once a year in September.

The special functions of the Assembly included the admission of new members, the periodical election of non-permanent members to the council, the election with the Council of the judges of the Permanent Court, and control of the budget. In practice, the Assembly was the general directing force of League activities.

The League Council acted as a type of executive body directing the Assembly's business. It began with four permanent members –

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, and

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

– and four non-permanent members that were elected by the Assembly for a three-year term. The first non-permanent members were

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

,

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

,

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

The composition of the council was changed several times. The number of non-permanent members was first increased to six on 22 September 1922 and to nine on 8 September 1926.

Werner Dankwort

Carl Werner Dankwort (August 13, 1895 – December 19, 1986) born in Gumbinnen, East Prussia (now Gusev, Russia), was a German diplomat who served a major role in bringing Germany into the League of Nations in 1926 prior to representing the Germa ...

of Germany pushed for his country to join the League; joining in 1926, Germany became the fifth permanent member of the council. Later, after Germany and Japan both left the League, the number of non-permanent seats was increased from nine to eleven, and the Soviet Union was made a permanent member giving the council a total of fifteen members.

[ The Council met, on average, five times a year and in extraordinary sessions when required. In total, 107 sessions were held between 1920 and 1939.

]

Other bodies

The League oversaw the Permanent Court of International Justice and several other agencies and commissions created to deal with pressing international problems. These included the Disarmament Commission, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Mandates Commission, the International Commission on Intellectual Cooperation

The International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, sometimes League of Nations Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, was an advisory organization for the League of Nations which aimed to promote international exchange between scientists, r ...

(precursor to UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

), the Permanent Central Opium Board

The expression International Opium Convention refers either to the first International Opium Convention signed at The Hague in 1912, or to the second International Opium Convention signed at Geneva in 1925.

First International Opium Convention ...

, the Commission for Refugees, and the Slavery Commission. Three of these institutions were transferred to the United Nations after the Second World War: the International Labour Organization, the Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, existed from 1922 to 1946. It was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1920 (although the idea of an international court was several cent ...

(as the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

), and the Health OrganisationWorld Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

).

The Permanent Court of International Justice was provided for by the Covenant, but not established by it. The Council and the Assembly established its constitution. Its judges were elected by the Council and the Assembly, and its budget was provided by the latter. The Court was to hear and decide any international dispute which the parties concerned submitted to it. It might also give an advisory opinion on any dispute or question referred to it by the council or the Assembly. The Court was open to all the nations of the world under certain broad conditions.

The International Labour Organization was created in 1919 on the basis of Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles. The ILO, although having the same members as the League and being subject to the budget control of the Assembly, was an autonomous organisation with its own Governing Body, its own General Conference and its own Secretariat. Its constitution differed from that of the League: representation had been accorded not only to governments but also to representatives of employers' and workers' organisations. Albert Thomas was its first director.

The ILO successfully restricted the addition of lead to paint, and convinced several countries to adopt an eight-hour work day and forty-eight-hour working week. It also campaigned to end child labour, increase the rights of women in the workplace, and make shipowners liable for accidents involving seamen. After the demise of the League, the ILO became an agency of the United Nations in 1946.

The ILO successfully restricted the addition of lead to paint, and convinced several countries to adopt an eight-hour work day and forty-eight-hour working week. It also campaigned to end child labour, increase the rights of women in the workplace, and make shipowners liable for accidents involving seamen. After the demise of the League, the ILO became an agency of the United Nations in 1946.Office international d'hygiène publique

The International Office of Public Hygiene, also known by its French name as the Office International d'Hygiène Publique and abbreviated as OIHP, was an international organization founded 9 December 1907 and based in Paris, France. It merged on ...

(OIHP) founded in 1907 after the International Sanitary Conferences The International Sanitary Conferences were a series of 14 conferences, the first of them organized by the French Government in 1851 to standardize international quarantine regulations against the spread of cholera, plague, and yellow fever. In tota ...

, was discharging most of the practical health-related questions, and its relations with the League's Health Committee were often conflictual.leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

, malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, and yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, the latter two by starting an international campaign to exterminate mosquitoes. The Health Organisation also worked successfully with the government of the Soviet Union to prevent typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

epidemics, including organising a large education campaign.

Linked with health, but also commercial concerns, was the topic of narcotics control. Introduced by the second International Opium Convention, the Permanent Central Opium Board

The expression International Opium Convention refers either to the first International Opium Convention signed at The Hague in 1912, or to the second International Opium Convention signed at Geneva in 1925.

First International Opium Convention ...

had to supervise the statistical reports on trade in opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

, morphine, cocaine and heroin. The board also established a system of import certificates and export authorisations for the legal international trade in narcotics

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "to make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiates ...

.

The League of Nations had devoted serious attention to the question of international intellectual co-operation since its creation. The First Assembly in December 1920 recommended that the Council take action aiming at the international organisation of intellectual work, which it did by adopting a report presented by the Fifth Committee of the Second Assembly and inviting a committee on intellectual co-operation to meet in Geneva in August 1922. The French philosopher Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson became the first chairman of the committee. The work of the committee included: an inquiry into the conditions of intellectual life, assistance to countries where intellectual life was endangered, creation of national committees for intellectual co-operation, co-operation with international intellectual organisations, protection of intellectual property, inter-university co-operation, co-ordination of bibliographical work and international interchange of publications, and international co-operation in archaeological research.

The Slavery Commission sought to eradicate slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and slave trading across the world, and fought forced prostitution. Its main success was through pressing the governments who administered mandated countries to end slavery in those countries. The League secured a commitment from Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

to end slavery as a condition of membership in 1923, and worked with Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

to abolish forced labour and intertribal slavery. The United Kingdom had not supported Ethiopian membership of the League on the grounds that "Ethiopia had not reached a state of civilisation and internal security sufficient to warrant her admission."

The League also succeeded in reducing the death rate of workers constructing the Tanganyika railway from 55 to 4 per cent. Records were kept to control slavery, prostitution, and the trafficking of women and children. Partly as a result of pressure brought by the League of Nations, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

abolished slavery in 1923, Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

in 1924, Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

in 1926, Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

in 1929, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

in 1937, and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

in 1942.

Led by Fridtjof Nansen, the Commission for Refugees was established on 27 June 1921 to look after the interests of refugees, including overseeing their

Led by Fridtjof Nansen, the Commission for Refugees was established on 27 June 1921 to look after the interests of refugees, including overseeing their repatriation

Repatriation is the process of returning a thing or a person to its country of origin or citizenship. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as to the pro ...

and, when necessary, resettlement. At the end of the First World War, there were two to three million ex-prisoners of war from various nations dispersed throughout Russia; within two years of the commission's foundation, it had helped 425,000 of them return home. It established camps in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

in 1922 to aid the country with an ongoing refugee crisis, helping to prevent the spread of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

as well as feeding the refugees in the camps. It also established the Nansen passport

Nansen passports, originally and officially stateless persons passports, were internationally recognized refugee travel documents from 1922 to 1938, first issued by the League of Nations's Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees to stateles ...

as a means of identification for stateless people

In international law, a stateless person is someone who is "not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law". Some stateless people are also refugees. However, not all refugees are stateless, and many people who are st ...

.

The Committee for the Study of the Legal Status of Women sought to inquire into the status of women all over the world. It was formed in 1937, and later became part of the United Nations as the Commission on the Status of Women.

The Covenant of the League said little about economics. Nonetheless, in 1920 the Council of the League called for a financial conference. The First Assembly at Geneva provided for the appointment of an Economic and Financial Advisory Committee to provide information to the conference. In 1923, a permanent economic and financial organisation came into being.

Members

Of the League's 42 founding members, 23 (24 counting

Of the League's 42 founding members, 23 (24 counting Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

) remained members until it was dissolved in 1946. In the founding year, six other states joined, only two of which remained members throughout the League's existence. Under the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

was admitted to the League of Nations through a resolution passed on 8 September 1926.

An additional 15 countries joined later. The largest number of member states was 58, between 28 September 1934 (when Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

joined) and 23 February 1935 (when Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

withdrew).

On 26 May 1937, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

became the last state to join the League. The first member to withdraw permanently from the League was Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

on 22 January 1925; having joined on 16 December 1920, this also makes it the member to have most quickly withdrawn. Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

was the first founding member to withdraw (14 June 1926), and Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

the last (April 1942). Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, which joined in 1932, was the first member that had previously been a League of Nations mandate.

The Soviet Union became a member on 18 September 1934, and was expelled on 14 December 1939 for invading Finland. In expelling the Soviet Union, the League broke its own rule: only 7 of 15 members of the Council voted for expulsion (United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Bolivia, Egypt, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

), short of the majority required by the Covenant. Three of these members had been made Council members the day before the vote (South Africa, Bolivia, and Egypt). This was one of the League's final acts before it practically ceased functioning due to the Second World War.

Mandates

At the end of the First World War, the Allied powers were confronted with the question of the disposal of the former German colonies in Africa and the Pacific, and the several Arabic-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The Peace Conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of certain states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities and sign a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in the past include the follo ...

adopted the principle that these territories should be administered by different governments on behalf of the League – a system of national responsibility subject to international supervision. This plan, defined as the mandate system

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

, was adopted by the "Council of Ten" (the heads of government and foreign ministers of the main Allied powers: Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Japan) on 30 January 1919 and transmitted to the League of Nations.

League of Nations mandates were established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. The Permanent Mandates Commission supervised League of Nations mandates, and also organised plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

s in disputed territories so that residents could decide which country they would join. There were three mandate classifications: A, B and C.

The A mandates (applied to parts of the old Ottoman Empire) were "certain communities" that had

The B mandates were applied to the former German colonies

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

that the League took responsibility for after the First World War. These were described as "peoples" that the League said were

South West Africa and certain South Pacific Islands were administered by League members under C mandates. These were classified as "territories"

Mandatory powers

The territories were governed by mandatory powers, such as the United Kingdom in the case of the Mandate of Palestine, and the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

in the case of South-West Africa, until the territories were deemed capable of self-government. Fourteen mandate territories were divided up among seven mandatory powers: the United Kingdom, the Union of South Africa, France, Belgium, New Zealand, Australia and Japan. With the exception of the Kingdom of Iraq, which joined the League on 3 October 1932, these territories did not begin to gain their independence until after the Second World War, in a process that did not end until 1990. Following the demise of the League, most of the remaining mandates became United Nations Trust Territories

United Nations trust territories were the successors of the remaining League of Nations mandates and came into being when the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946. All of the trust territories were administered through the United Nati ...

.

In addition to the mandates, the League itself governed the Territory of the Saar Basin

The Territory of the Saar Basin (german: Saarbeckengebiet, ; french: Territoire du bassin de la Sarre) was a region of Germany occupied and governed by the United Kingdom and France from 1920 to 1935 under a League of Nations mandate. It had its ...

for 15 years, before it was returned to Germany following a plebiscite, and the Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

, Poland) from 15 November 1920 to 1 September 1939.

Resolving territorial disputes

The aftermath of the First World War left many issues to be settled, including the exact position of national boundaries and which country particular regions would join. Most of these questions were handled by the victorious Allied powers in bodies such as the Allied Supreme Council. The Allies tended to refer only particularly difficult matters to the League. This meant that, during the early interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, the League played little part in resolving the turmoil resulting from the war. The questions the League considered in its early years included those designated by the Paris Peace treaties.

As the League developed, its role expanded, and by the middle of the 1920s it had become the centre of international activity. This change can be seen in the relationship between the League and non-members. The United States and the Soviet Union, for example, increasingly worked with the League. During the second half of the 1920s, France, Britain and Germany were all using the League of Nations as the focus of their diplomatic activity, and each of their foreign secretaries attended League meetings at Geneva during this period. They also used the League's machinery to try to improve relations and settle their differences.

Åland Islands

Åland

Åland ( fi, Ahvenanmaa: ; ; ) is an Federacy, autonomous and Demilitarized zone, demilitarised region of Finland since 1920 by a decision of the League of Nations. It is the smallest region of Finland by area and population, with a size of 1 ...

is a collection of around 6,500 islands in the Baltic Sea, midway between Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

. The islands are almost exclusively Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

-speaking, but in 1809, the Åland Islands, along with Finland, were taken by Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

. In December 1917, during the turmoil of the Russian October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

, Finland declared its independence, but most of the Ålanders wished to rejoin Sweden. The Finnish government considered the islands to be a part of their new nation, as the Russians had included Åland in the Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecessor ...

, formed in 1809. By 1920, the dispute had escalated to the point that there was danger of war. The British government referred the problem to the League's Council, but Finland would not let the League intervene, as they considered it an internal matter. The League created a small panel to decide if it should investigate the matter and, with an affirmative response, a neutral commission was created. In June 1921, the League announced its decision: the islands were to remain a part of Finland, but with guaranteed protection of the islanders, including demilitarisation. With Sweden's reluctant agreement, this became the first European international agreement concluded directly through the League.

Upper Silesia

The Allied powers referred the problem of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located ...

to the League after they had been unable to resolve the territorial dispute between Poland and Germany. In 1919 Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

voiced a claim to Upper Silesia, which had been part of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. The Treaty of Versailles had recommended a plebiscite in Upper Silesia

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

to determine whether the territory should become part of Germany or Poland. Complaints about the attitude of the German authorities led to rioting and eventually to the first two Silesian Uprisings

The Silesian Uprisings (german: Aufstände in Oberschlesien, Polenaufstände, links=no; pl, Powstania śląskie, links=no) were a series of three uprisings from August 1919 to July 1921 in Upper Silesia, which was part of the Weimar Republic ...

(1919 and 1920). A plebiscite took place on 20 March 1921, with 59.6 per cent (around 500,000) of the votes cast in favour of joining Germany, but Poland claimed the conditions surrounding it had been unfair. This result led to the Third Silesian Uprising

The Silesian Uprisings (german: Aufstände in Oberschlesien, Polenaufstände, links=no; pl, Powstania śląskie, links=no) were a series of three uprisings from August 1919 to July 1921 in Upper Silesia, which was part of the Weimar Republic ...

in 1921.