Law in Nazi Germany on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime ruled

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime ruled

After World War 1, Germany considered the law a "most respected entity" as the country regained stability and public confidence. Many German lawyers and judges were Jewish.

After World War 1, Germany considered the law a "most respected entity" as the country regained stability and public confidence. Many German lawyers and judges were Jewish.  The 27 February 1933

The 27 February 1933

When Germany was completely under Nazi rule, the number and severity of laws increased. The Nuremberg Laws were announced after the annual Nazi party rally in

When Germany was completely under Nazi rule, the number and severity of laws increased. The Nuremberg Laws were announced after the annual Nazi party rally in

In Nazi Germany, the civil service provided a legal framework to deprive Jews of their rights. Opportunities to create anti-Jewish policies were coveted and career bureaucrats came together and developed increasingly radical policies. Their familiarity with the legal system enabled them to easily manipulate it. The judiciary lost its independence as it was increasingly controlled by the Nazis. Judges who did not join the National Socialist League for the Maintenance of Law were dismissed. Jewish lawyers and judges and those with socialist or other views inconvenient to the Nazi Party were removed. The fundamental legal principle became Nazi "common sense", "Whatever is good for Germany is legal". The People's Court () was created in 1934 for people accused of political crimes. In 1938, all crimes began to be tried in the court; in 1939, its remit was expanded to include minor offenses.

In Nazi Germany, the civil service provided a legal framework to deprive Jews of their rights. Opportunities to create anti-Jewish policies were coveted and career bureaucrats came together and developed increasingly radical policies. Their familiarity with the legal system enabled them to easily manipulate it. The judiciary lost its independence as it was increasingly controlled by the Nazis. Judges who did not join the National Socialist League for the Maintenance of Law were dismissed. Jewish lawyers and judges and those with socialist or other views inconvenient to the Nazi Party were removed. The fundamental legal principle became Nazi "common sense", "Whatever is good for Germany is legal". The People's Court () was created in 1934 for people accused of political crimes. In 1938, all crimes began to be tried in the court; in 1939, its remit was expanded to include minor offenses.

After the end of

After the end of

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime ruled

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime ruled Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and controlled almost all of Europe. During this time, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

shifted from the post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

society which characterized the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

and introduced an ideology of "biological racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism ( racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be mor ...

" into the country's legal and justicial systems. The shift from the traditional legal system (the "normative state") to the Nazis' ideological mission (the "prerogative state") enabled all of the subsequent acts of the Hitler regime (including its atrocities) to be performed "legally". For this to succeed, the normative judicial system needed to be reworked; judges, lawyers and other civil servants acclimatized themselves to the new Nazi laws and personnel.

History

After World War 1, Germany considered the law a "most respected entity" as the country regained stability and public confidence. Many German lawyers and judges were Jewish.

After World War 1, Germany considered the law a "most respected entity" as the country regained stability and public confidence. Many German lawyers and judges were Jewish. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was inspired by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's October 1922 March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fa ...

, which brought Mussolini's National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

to power in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.

Hitler's Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

took place in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, on 8–9 November 1923. The attempted coup was halted by Bavarian police; 16 Nazis were killed, and Hitler was imprisoned (where he wrote ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

''). Hitler exploited Weimar's economic hardships, which included hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

and the effects of the Great Depression. His actions and goals have been described as using the "constitution to destroy the constitution" and the "rules of the republic to destroy the republic".

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

influence increased after the party became the largest in the Reichstag. Increasing public pressure, including marches, lawlessness and racism, forced president Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

to appoint Hitler Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

on 30 January 1933; this was known as the ''Machtergreifung

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

''.

The 27 February 1933

The 27 February 1933 Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire (german: Reichstagsbrand, ) was an arson attack on the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament in Berlin, on Monday 27 February 1933, precisely four weeks after Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of ...

was used as a pretext to suspend the Weimar Constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (german: Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (''Weimarer Verfassung''), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era (1919–1933). The c ...

and impose a four-year state of emergency. The Reichstag Fire Decree

The Reichstag Fire Decree (german: Reichstagsbrandverordnung) is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State (german: Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutz von Volk und Staat) issued by Germ ...

would "safeguard public security" by restricting civil liberties and granting increased power to the police, and the SA arrested 4,000 members of the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

. Legislative power was given to Hitler so his government could create laws without Reichstag consent.

Several principles were invoked during the state of emergency. The ''Führerprinzip

The (; German for 'leader principle') prescribed the fundamental basis of political authority in the Government of Nazi Germany. This principle can be most succinctly understood to mean that "the Führer's word is above all written law" and t ...

'' ("leader principle") designated Hitler as above the law. The Volkist Principle of Racial Inequality organised the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

by race; anyone not considered part of the ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community",Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'' (people's community) was seen as undeserving of legal protection.

In 1933, The Reich Ministry of the Interior (RMI) was utilised by the Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

to consolidate Hitler's rise to power. New civil-service legislation enabled the removal of non-Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

s and the "politically unreliable." Autonomy was removed from individual German states and provinces through a process of coordination (''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

''), and Nazi ideology was imposed by racial and ancestral legislation which defined who was (or was not) a German. In 1936, SS leader and RMI state secretary Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

was placed in charge of the civil police. With the growth of Nazi Germany, the RMI organized the administration of newly-acquired countries and territories.

During the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

, which began on 30 June 1934, 80 stormtrooper leaders and other opponents of Hitler were arrested and shot. Von Hindenberg's death on 2 August 1934 enabled Hitler to usurp his presidential powers, and his dictatorship was built upon his position as Reich president

''Reich'' (; ) is a German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word "realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emperor") and ' (lit ...

(head of state), Reich Chancellor (head of government) and Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the Umlaut (diacritic), umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or "guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi Germany, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany ...

(leader of the Nazi Party). The 9–10 November 1938 ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from ...

'' (Night of Broken Glass) had attacks on synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

s and Jewish businesses and citizens. Over 100 were killed, and thousands were arrested. Two hundred sixty-seven synagogues in Germany, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

were destroyed; firefighters were instructed to only prevent the flames from spreading. About 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and imprisoned or interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

in concentration camps. The government blamed the Jewish people for the attacks, and imposed a fine of one billion ℛℳ. After ''Kristallnacht'', additional decrees removed the Jews from German economic and social life; those who could emigrated elsewhere.

Laws

After the Reichstag Fire Decree, theEnabling Act of 1933

The Enabling Act (German: ') of 1933, officially titled ' (), was a law that gave the German Cabinet – most importantly, the Chancellor – the powers to make and enforce laws without the involvement of the Reichstag or Weimar Presi ...

amended the Weimar Constitution to allow Hitler and his government to enact laws (even laws violating the constitution) without going through the Reichstag. Nazi intimidation of the opposition resulted in a vote of 444 to 94.

Flag law

According to the Reich flag law, Germany's national colors were black, white, and red and its flag incorporated theswastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

. In the words of Hitler, this was to "repay a debt of gratitude to the movement under whose symbol Germany regained its freedom, fulfilling a significant item on the program of the National Socialist Party".Friedlander, Saul (1997). ''Nazi Germany and The Jews''. HarperCollins, p. 142. .

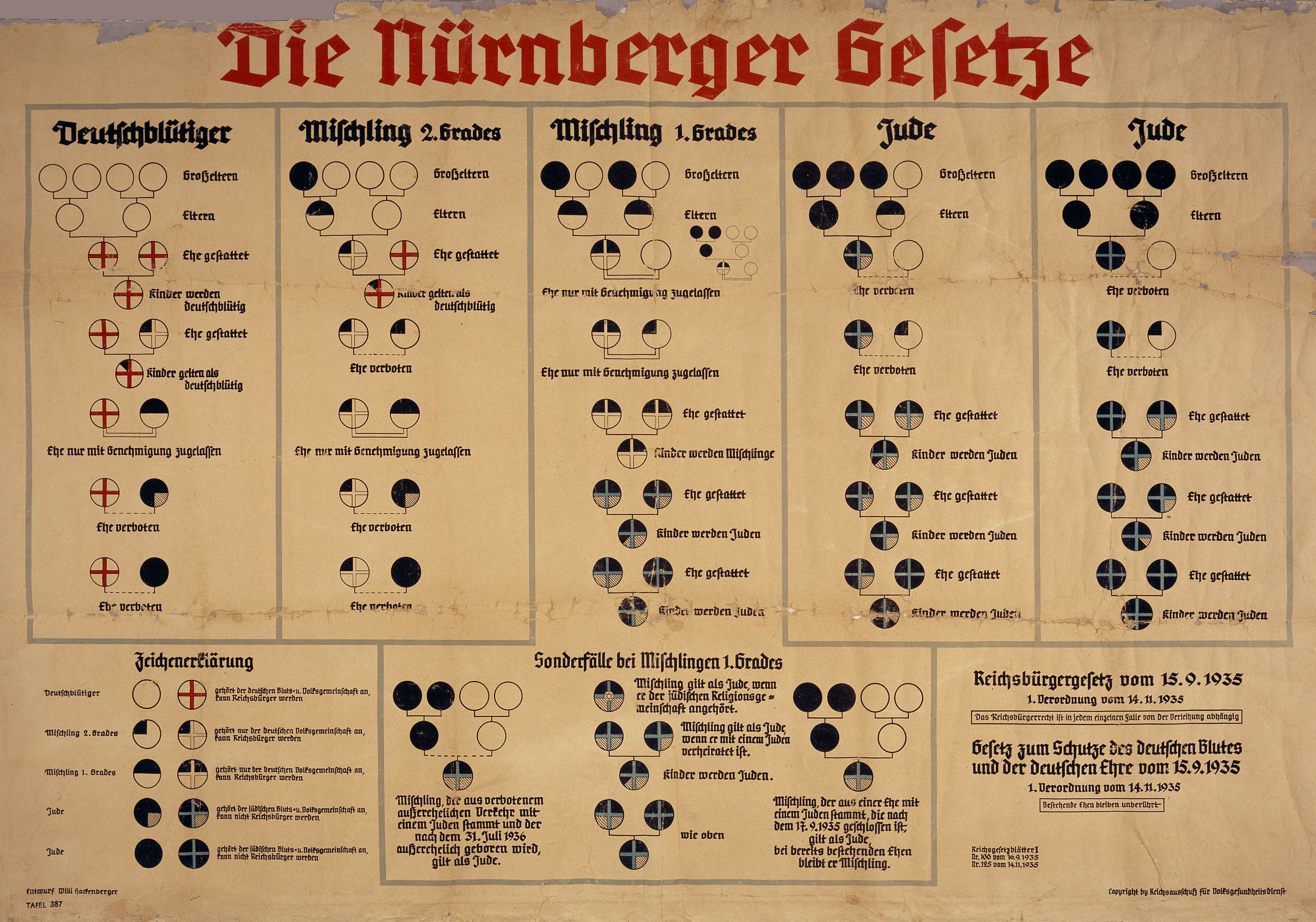

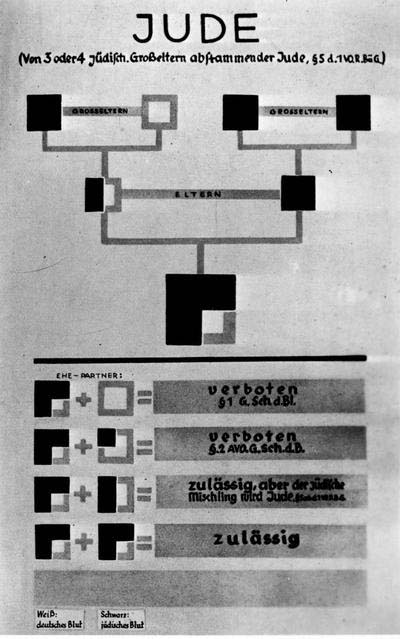

Nuremberg Laws

When Germany was completely under Nazi rule, the number and severity of laws increased. The Nuremberg Laws were announced after the annual Nazi party rally in

When Germany was completely under Nazi rule, the number and severity of laws increased. The Nuremberg Laws were announced after the annual Nazi party rally in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

on 15 September 1935. The two laws authorized arrests of, and violence against, Jews. Initially imposed in Germany, Nazi expansion during the Second World War resulted in the imposition of the Nuremberg Laws in occupied territories.

Citizenship Law

The Citizenship Law formally defined who among the ''Staatsangehörige'' (state subjects) of the Reich would retain full political rights as a 'citizen of the Reich', consequently leaving the remaining population as effective non-citizens with no guaranteed rights. The law's definition of what constituted a citizen of the Reich utilized particularly ambiguous language; a citizen was defined as a "German or kindred blood ... who, through his conduct ... is both desirous and fit to serve the German people and the Reich faithfully". This ambiguity resulted in some of the human rights violations following the law's passage being justified (within the Nazi legal framework) by bureaucrats, law enforcement and medical professionals as legal acts under the 1935 law. In particular, the first condition ensured that many of the non-European ethnic and religious minorities residing in Germany (targeting the Jewish population in particular) were no longer to be considered citizens whereas the latter condition allowed the same to occur to any group that might be considered "unfit for reproduction", including groups such as the mentally ill, alcoholics, those with congenital and/or chronic illness, among many others. The details as to which rights would be stripped in the latter case were specified in the companion "Law for Hereditary Hygiene", also included in the Nuremberg Laws. This law effectively legitimized the Nazi eugenics movement, inspired by various meetings between Hitler and American and British eugenicists, as legal. The extent to which the British originators and American early adopters of the pseudo-science influenced Nazi eugenics is perhaps best exhibited by an openly acknowledged inspiration used in drafting the Nazi social hygiene laws being the 1924 US Virginia state law known as the "Eugenical Sterilization Act (seeEugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. T ...

).

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor

This law had five articles: # Marriages between Jews and Germans or relatives were forbidden, and existing marriages of this kind were void. # Sexual relations outside marriage between Jews and Germans or relatives were forbidden. # Jews were not allowed to employ female German citizens or relatives as domestic servants. # Jews were forbidden to display the national flag and/or colours # Violations of the first article were punishable by hard labor; violations of the second article were punishable by imprisonment, and violations of the third article were punishable by fine and imprisonment. A 14 November 1935 supplemental decree defined Jewishness. No longer limited to religious beliefs, the decree classified those who followed the Jewish faith, belonged to the Jewish religion when the decree was promulgated, or later entered the Jewish religion, anyone who had three or more Jewish grandparents or two Jewish grandparents and was married to a Jewish spouse and anyone who joined a Jewish community as Jewish, regardless of whether they still followed the religion.Friedlander, Saul (1997). ''Nazi Germany and the Jews''. HarperCollins. p. 149. Nineteen hundred "special Jewish laws" emphasized Aryan morality andantisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

stereotypes of "Jewish counter-morality". Jewish lawyers and notaries

A notary is a person authorised to perform acts in legal affairs, in particular witnessing signatures on documents. The form that the notarial profession takes varies with local legal systems.

A notary, while a legal professional, is disti ...

had been prohibited from working for the city of Nuremberg in a 1933 decree, and Nazi ideology continue to creep into the legal system:

* The use of Jewish names for spelling in telephone delivery of telegrams was banned (22 April 1933).

* Non-Aryans could not be lay judge A lay judge, sometimes called a lay assessor, is a person assisting a judge in a trial. Lay judges are used in some civil law jurisdictions. Lay judges are appointed volunteers and often require some legal instruction. However, they are not perman ...

s or jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartiality, impartial verdict (a Question of fact, finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a sentence (law), penalty o ...

members (13 November 1933).

* The perception that Aryan students were receiving assistance from Jews in preparing for their exams must end (4 April 1935).

* The kosher slaughter of animals was prohibited.

* Sports laws prohibiting Jewish boxing and public swimming

For a brief period before and during the 1936 Summer Olympics

The 1936 Summer Olympics (German: ''Olympische Sommerspiele 1936''), officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad (German: ''Spiele der XI. Olympiade'') and commonly known as Berlin 1936 or the Nazi Olympics, were an international multi-sp ...

in Berlin, antisemitic laws and attacks were moderated and discriminatory signage removed. Although this was regarded as an attempt by Hitler to appease the international audience and limit criticism and interference, nearly all German Jewish athletes were excluded from Olympic competition.

Later antisemitic laws

According to historianSaul Friedländer

Saul Friedländer (; born October 11, 1932) is a Czech-Jewish-born historian and a professor emeritus of history at UCLA.

Biography

Saul Friedländer was born in Prague to a family of German-speaking Jews. He was raised in France and lived thro ...

, the "fateful turning point" was reached in 1938 and 1939Friedlander, Saul (1997). ''Nazi Germany and The Jews.'' HarperCollins''.'' p. 180. with the passage of additional laws which used economic harassment and violence to drive Jews from Germany and Austria:

* Jewish physicians were de-certified, and were no longer allowed to treat German patients.

* Jews were not allowed to own gardens.

* All Jewish-named streets in Germany were renamed.

* Jews were prohibited from cinemas, the opera, and concerts.

* Jewish children were banned from public schools.

* Robbing Jews became legal, and Jews were forced to surrender "all jewellery of any value".Efron, Weitzman, Lehmann, John, Steven, Matthias (2004). ''The Jews: A History''. Pearson Education Inc. pp. 410–411. .

Legal system

In Nazi Germany, the civil service provided a legal framework to deprive Jews of their rights. Opportunities to create anti-Jewish policies were coveted and career bureaucrats came together and developed increasingly radical policies. Their familiarity with the legal system enabled them to easily manipulate it. The judiciary lost its independence as it was increasingly controlled by the Nazis. Judges who did not join the National Socialist League for the Maintenance of Law were dismissed. Jewish lawyers and judges and those with socialist or other views inconvenient to the Nazi Party were removed. The fundamental legal principle became Nazi "common sense", "Whatever is good for Germany is legal". The People's Court () was created in 1934 for people accused of political crimes. In 1938, all crimes began to be tried in the court; in 1939, its remit was expanded to include minor offenses.

In Nazi Germany, the civil service provided a legal framework to deprive Jews of their rights. Opportunities to create anti-Jewish policies were coveted and career bureaucrats came together and developed increasingly radical policies. Their familiarity with the legal system enabled them to easily manipulate it. The judiciary lost its independence as it was increasingly controlled by the Nazis. Judges who did not join the National Socialist League for the Maintenance of Law were dismissed. Jewish lawyers and judges and those with socialist or other views inconvenient to the Nazi Party were removed. The fundamental legal principle became Nazi "common sense", "Whatever is good for Germany is legal". The People's Court () was created in 1934 for people accused of political crimes. In 1938, all crimes began to be tried in the court; in 1939, its remit was expanded to include minor offenses. Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler (30 October 1893 – 3 February 1945), a German Nazi jurist, judge, and politician, served as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice from 1934 to 1942 and as President of the People's Court from 1942 to 1945.

As ...

, appointed in 1942 as judge and interrogator, was infamous for "berating and belittling" defendants and lawyers. Statutes were "systematically misinterpreted”, and the court has been described as committing "judicial murders". Separation of defendants and lawyers was calculated to prevent communication, and defense presentations were often interrupted. Courts were made up of three judges; all verdicts were final, and the convicted defendant was immediately executed. The 20 July plot

On 20 July 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and other conspirators attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of Nazi Germany, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia, now Kętrzyn, in present-day Poland. The ...

in 1944 was accompanied by a series of aggressive prosecutions, and over 110 death sentences were imposed in fifty trials.

Nuremberg trials

After the end of

After the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

were conducted in 1945 and 1946 to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. The Nuremberg Charter

The Charter of the International Military Tribunal – Annex to the Agreement for the prosecution and punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis (usually referred to as the Nuremberg Charter or London Charter) was the decree issue ...

, decreeing an International Military Tribunal (IMT), was announced on 8 August 1945 to conduct 13 trials made up of judges from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Article six of the charter outlines the crimes for which Nazi officials would be tried:

# Conspiracy to commit charges two, three, and four below

# Crimes against peace – participation in the planning and waging of a war of aggression in violation of international treaties

# War crimes – violations of the internationally agreed-on rules for waging war

# Crimes against humanity – murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecution on political, racial, or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where it was perpetrated.

Twenty-four Nazi officials were indicted for these crimes on 6 October 1945, including Hermann Goring (Speaker of the Reichstag), Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

(Nazi Deputy Leader), Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

(Foreign Minister), and Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, duri ...

(Head of The Armed Forces). Verdicts included 12 death sentences, three life imprisonments, four prison terms of 10–20 years and three acquittals. Those acquitted were Hjalmar Schacht

Hjalmar Schacht (born Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht; 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970, ) was a German economist, banker, centre-right politician, and co-founder in 1918 of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner a ...

(Economics Minister), Former Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

, and Hans Fritzsche (Head of Press and Radio).

See also

*Anti-Jewish legislation in pre-war Nazi Germany

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

* Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch

The ''Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch'' (, ), abbreviated BGB, is the civil code of Germany. In development since 1881, it became effective on 1 January 1900, and was considered a massive and groundbreaking project.

The BGB served as a template in sev ...

* Strafgesetzbuch

''Strafgesetzbuch'' (), abbreviated to ''StGB'', is the German penal code.

History

In Germany the ''Strafgesetzbuch'' goes back to the Penal Code of the German Empire passed in the year 1871 on May 15 in Reichstag which was largely identica ...

References

{{reflist