Under

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, the

Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

became a political force as well as a religious tendency in the country. Opponents of the

royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

became allies of Puritan reformers, who saw the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

moving in a direction opposite to what they wanted, and objected to increased

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

influence both at Court and (as they saw it) within the Church.

After the

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

political power was held by various factions of Puritans. The trials and executions of

William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

and then King Charles himself were decisive moves shaping British history. While in the short term Puritan power was consolidated by the Parliamentary armed forces and

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

, in the same years, the argument for

theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

failed to convince enough of the various groupings, and there was no Puritan religious settlement to match Cromwell's gradual assumption of dictatorial powers. The distinctive formulation of

Reformed theology

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

in the

Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

would prove to be its lasting legacy.

In

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, immigration of what were Puritan family groups and congregations was at its peak for the period the middle years of King Charles's reign.

Synod of Dort to the death of Archbishop Abbot (1618-1633)

The 1630s conflict between

Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

and traditional

Episcopalians

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

over

Laudianism

Laudianism was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England, promulgated by Archbishop William Laud and his supporters. It rejected the predestination upheld by the previously dominant Calvinism in favour of free will, ...

in the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

was preceded by similar arguments in the 1620s concerning

Arminianism. Its rejection of some of the key tenets of

Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, notably

Predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

, made it particularly objectionable to Puritans, who viewed it as crypto-

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. This theological debate was sharpened by the outbreak of the

Thirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

in 1618 and recommencement of the

Eighty Years' War between the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in 1621, leading many to see it as part of a general attack on

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

.

As a

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

,

James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

generally backed his co-religionists in the

debate between Calvinists and Arminians. He sent a strong delegation to the 1618 to 1619

Synod of Dort held in the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, and supported their condemnation of Arminianism as heretical, although he moderated his views when attempting to achieve a

Spanish match for his son

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. In fact, the English were less precise than their Dutch counterparts in their interpretation of "Arminianism", which allowed James some flexibility.

James died in 1625 and was succeeded by Charles, who was deeply distrustful of the Puritans, seeing their views on church governance and foreign affairs as driven by political calculation, while also constituting a direct challenge to his

divinely-mandated authority. Charles had no particular interest in theological questions, but preferred the emphasis on order, decorum, uniformity, and spectacle in Christian worship. While his father supported the pro-Calvinist rulings issued by the Synod of Dort, Charles forbade preaching on the subject of predestination altogether, and where James had been lenient towards clergy who omitted parts of the ''

Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', Charles urged the bishops to enforce compliance and to suspend those who refused.

Besides

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, Charles's closest political advisor was

William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, the

Bishop of St David's

The Bishop of St Davids is the ordinary of the Church in Wales Diocese of St Davids.

The succession of bishops stretches back to Saint David who in the 6th century established his seat in what is today the city of St Davids in Pembrokeshire, ...

, whom Charles

translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

to the better position of

Bishop of Bath and Wells

The Bishop of Bath and Wells heads the Church of England Diocese of Bath and Wells in the Province of Canterbury in England.

The present diocese covers the overwhelmingly greater part of the (ceremonial) county of Somerset and a small area of D ...

in 1626. Under Laud's influence, Charles shifted the royal ecclesiastical policy markedly.

Conflict between Charles I and Puritans, 1625–1629

In 1625, shortly before the opening of the new parliament, Charles was married by proxy to

Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

, the Catholic daughter of

Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarch ...

. In diplomatic terms this implied alliance with France in preparation for war against Spain, but Puritan MPs openly claimed that Charles was preparing to restrict the

recusancy

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

laws. The king had indeed agreed to do so in the secret marriage treaty he negotiated with

Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

.

George Abbot

George Abbot,

Archbishop of Canterbury from 1611, was in the mainstream of the English church, sympathetic with Scottish Protestants, anti-Catholic in a conventional Calvinist way, and theologically opposed to Arminianism. Under Elizabeth I he had associated with Puritan figures. The controversy over

Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu (or Mountague) (1577 – 13 April 1641) was an English cleric and prelate.

Early life

Montagu was born during Christmastide 1577 at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, where his father Laurence Mountague was vicar, and was educated at ...

's anti-Calvinist ''New Gagg'' was still ongoing when Parliament met in May 1625, and he was attacked in

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

by the Puritan MP

John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

. When Montagu wrote a pamphlet asking for Royal protection entitled ''Appello Caesarem'' or "I Appeal to Caesar", a reference t

Acts 25:10–12 Charles responded by making him a royal chaplain.

Parliament was reluctant to grant Charles revenue, since they feared that it might be used to support an army that would re-impose Catholicism on England. The 1625 Parliament broke the precedent of centuries and voted to allow Charles to collect

Tonnage and Poundage

Tonnage and poundage were duties and taxes first levied in Edward II's reign on every tun (cask) of imported wine, which came mostly from Spain and Portugal, and on every pound weight of merchandise exported or imported. Traditionally tonnage an ...

only for one year. When Charles wanted to intervene in the Thirty Years' War by declaring war on Spain (the

Anglo-Spanish War (1625)

Anglo-Spanish War may refer to:

* Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604), including the Spanish Armada and the English Armada

* Anglo-Spanish War (1625–1630), part of the Thirty Years' War

* Anglo-Spanish War (1654–1660), part of the Franco-Spanish ...

), Parliament granted him an insufficient sum of £140,000. The war with Spain went ahead (partially funded by tonnage and poundage collected by Charles after he was no longer authorized to do so). Buckingham was put in charge of the war effort, but failed.

The

York House conference of 1626 saw battle lines start to be drawn up. Opponents cast doubt on the political loyalties of the Puritans, equating their beliefs with

resistance theory. In their preaching, Arminians began to take a royalist line. Abbot was deprived of effective power in 1627, in a quarrel with the king over

Robert Sibthorpe, one such royalist cleric. Richard Montagu was made

Bishop of Chichester

The Bishop of Chichester is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers the counties of East and West Sussex. The see is based in the City of Chichester where the bishop's sea ...

in 1628.

The

Anglo-French War (1627–1629)

The Anglo-French War () was a military conflict fought between the Kingdom of France and the Kingdom of England between 1627 and 1629. It mainly involved actions at sea.''Warfare at sea, 1500-1650: maritime conflicts and the transformation of E ...

was also a military failure. Parliament called for Buckingham's replacement, but Charles stuck by him. Parliament went on to pass the

Petition of Right

The Petition of Right, passed on 7 June 1628, is an English constitutional document setting out specific individual protections against the state, reportedly of equal value to Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689. It was part of a wider ...

, a declaration of Parliament's rights. Charles accepted the Petition, though this did not lead to a change in his behaviour.

The King's personal rule

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated by a disillusioned soldier,

John Felton. Public reaction angered Charles. When Parliament resumed sitting in January 1629, Charles was met with outrage over the case of

John Rolle, an MP who had been prosecuted for failing to pay Tonnage and Poundage.

John Finch, the

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

, was held down in the Speaker's Chair in order to allow the House to pass a resolution condemning the king.

Charles determined to rule without calling a parliament, thus initiating the period known as his

Personal Rule

The Personal Rule (also known as the Eleven Years' Tyranny) was the period from 1629 to 1640, when King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland ruled without recourse to Parliament. The King claimed that he was entitled to do this under the Roya ...

(1629–1640). This period saw the ascendancy of Laudianism in England.

Laudianism

The central ideal of Laudianism (the common name for the ecclesiastical policies pursued by Charles and Laud) was the "beauty of holiness" (a reference t

Psalm 29:2. This emphasized a love of ceremony and harmonious

liturgy. Many of the churches in England had fallen into disrepair in the wake of the English Reformation: Laudianism called for making churches beautiful. Churches were ordered to make repairs and to enforce greater respect for the church building.

A policy particularly odious to the Puritans was the installation of

altar rails in churches, which Puritans associated with the Catholic position on

transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις '' metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of ...

: in Catholic practice, altar rails served to demarcate the space where Christ became incarnate in the

host, with

priests,

acolytes, and

altar boys allowed inside the rail. They also argued that the practice of receiving communion while kneeling at the rail too much resembled Catholic

Eucharistic adoration. The Laudians insisted on kneeling at communion and receiving at the rail, denying that this involved accepting Catholic positions .

Puritans also objected to the Laudian insistence on calling members of the

clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

"priests". In their minds, the word "priest" meant "someone who offers a

sacrifice", and was therefore related in their minds to Catholic teaching on the

Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

as a sacrifice. After the Reformation, the term "

minister" (meaning "one who serves") was generally adopted by Protestants to describe their clergy; Puritans argued in favor of its use, or else for simply

transliterating the

Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

word

presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

used in the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

, without translation.

The Puritans were also dismayed when the Laudians insisted on the importance of keeping

Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

, a practice which had fallen into disfavor in England after the Reformation. They favored

fast days specifically called by the church or the government in response to the problems of the day, rather than days dictated by the

ecclesiastical calendar

The liturgical year, also called the church year, Christian year or kalendar, consists of the cycle of liturgical seasons in Christian churches that determines when feast days, including celebrations of saints, are to be observed, and which ...

.

The foundation of Puritan New England, 1630–1642

Some Puritans began considering founding their own colony where they could worship in a fully reformed church, far from King Charles and the bishops. This was a quite distinct view of the church from that held by the Separatists of

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

.

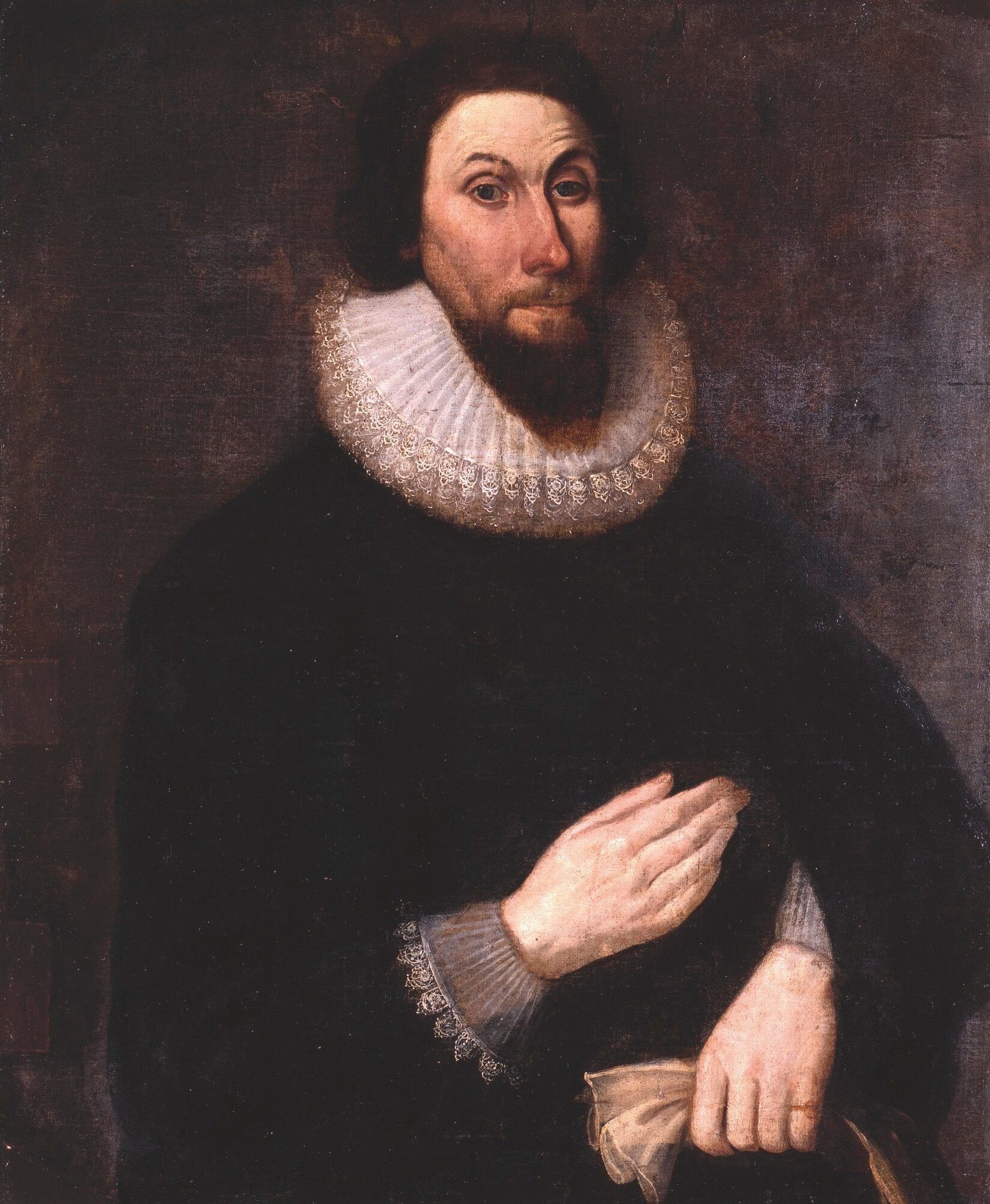

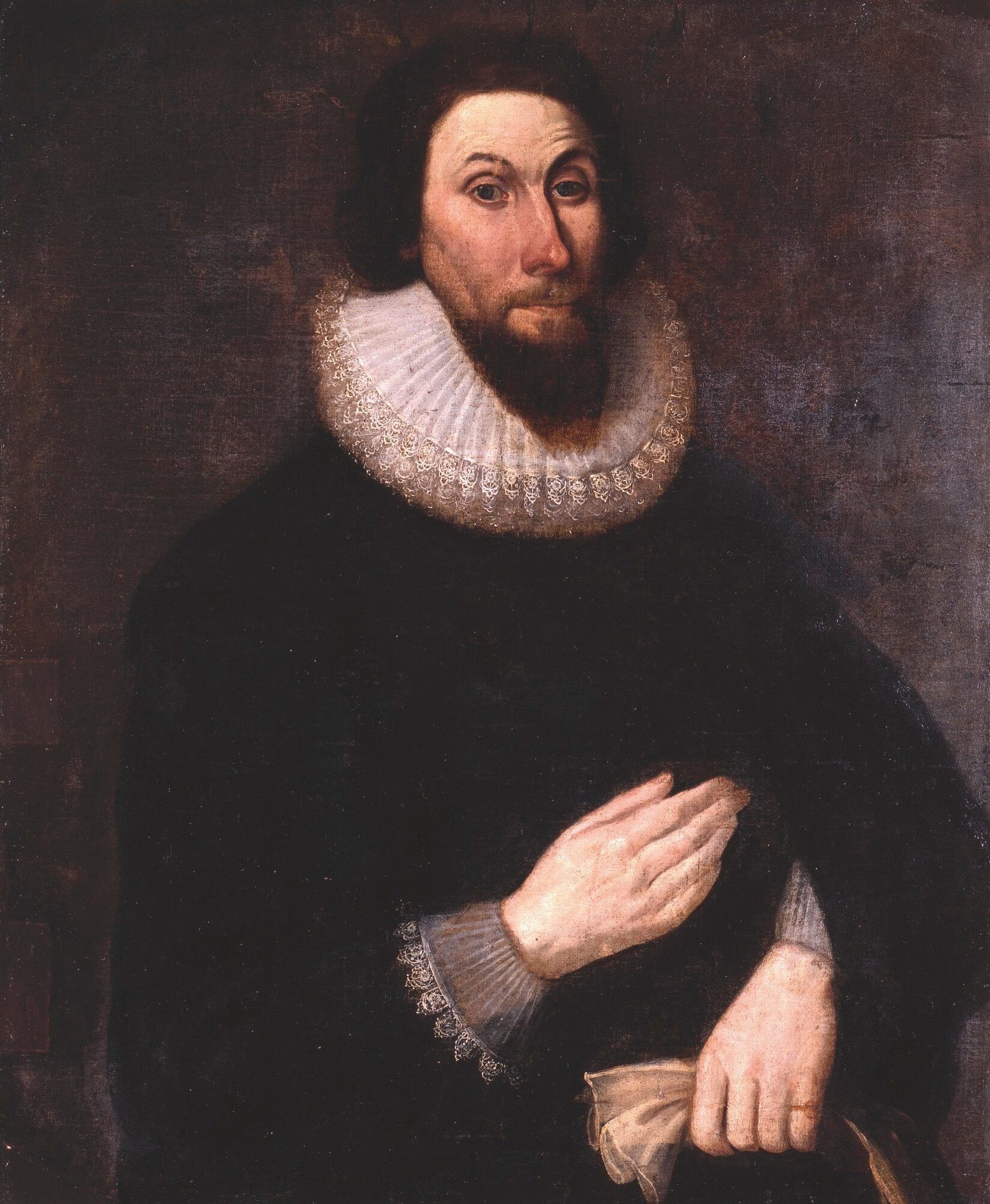

John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

, a lawyer who had practiced in the

Court of Wards

The Court of Wards and Liveries was a court established during the reign of Henry VIII in England. Its purpose was to administer a system of feudal dues; but as well as the revenue collection, the court was also responsible for wardship and liv ...

, began to explore the idea of creating a Puritan colony in

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

. The Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony had proved that such a colony was viable.

In 1627, the existing Dorchester Company for

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

colonial expansion went bankrupt, but was succeeded by the New England Company (the membership of the Dorchester and New England Companies overlapped). Throughout 1628 and 1629, Puritans in Winthrop's social circle discussed the possibility of moving to New England. The New England Company sought clearer title to the New England land of the proposed settlement than was provided by the

Sheffield Patent, and in March 1629 succeeded in obtaining from King Charles a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

changing the name of the company to the ''Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England'' and granting them the land to found the

Massachusetts Bay Colony. The royal charter establishing the Massachusetts Bay Company had not specified where the company's annual meeting should be held; this raised the possibility that the governor of the company could move to the new colony and serve as governor of the colony, while the general court of the company could be transformed into the colony's legislative assembly. John Winthrop participated in these discussions and in March 1629, signed the

Cambridge Agreement, by which the non-emigrating shareholders of the company agreed to turn over control of the company to the emigrating shareholders. As Winthrop was the wealthiest of the emigrating shareholders, the company decided to make him governor, and entrusted him with the company charter.

Winthrop sailed for New England in 1630 along with 700 colonists on board eleven ships known collectively as the

Winthrop Fleet

The Winthrop Fleet was a group of 11 ships led by John Winthrop out of a total of 16 funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company which together carried between 700 and 1,000 Puritans plus livestock and provisions from England to New England over th ...

. Winthrop himself sailed on board the ''

Arbella

''Arbella'' or ''Arabella'' was the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet on which Governor John Winthrop, other members of the Company (including William Gager), and Puritan emigrants transported themselves and the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Co ...

''. During the crossing, he preached a sermon entitled "A Model of Christian Charity", in which he called on his fellow settlers to make their new colony a

City upon a Hill,

[A reference t]

Matthew 5:14–16

/ref> meaning that they would be a model to all the nations of Europe as to what a properly reformed Christian commonwealth should look like. The context in 1630 was that the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

was going badly for the Protestants, and Catholicism was being restored in lands previously reformed – e.g. by the 1629 Edict of Restitution

The Edict of Restitution was proclaimed by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, on 6 March 1629, eleven years into the Thirty Years' War. Following Catholic League (German), Catholic military successes, Ferdinand hoped to restore control ...

.

Emigration was officially restricted to conforming churchmen in December 1634 by the Privy Council.

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1633–1643

In 1633 the moderate archbishop George Abbot died, and Charles I chose William Laud as his successor as Archbishop of Canterbury. Abbot had been in practical terms suspended from his functions in 1617 after he refused to order his clergy to read the '' Book of Sports''. Charles now re-issued the ''Book of Sports'', in a symbolic gesture of October 1633 against sabbatarianism

Sabbatarianism advocates the observation of the Sabbath in Christianity, in keeping with the Ten Commandments.

The observance of Sunday as a day of worship and rest is a form of first-day Sabbatarianism, a view which was historically heralded ...

. Laud further ordered his clergy to read it to their congregations, and acted to suspend ministers who refused to do that, an effective shibboleth

A shibboleth (; hbo, , šībbōleṯ) is any custom or tradition, usually a choice of phrasing or even a single word, that distinguishes one group of people from another. Shibboleths have been used throughout history in many societies as passwo ...

to root out Puritan clergy. The 1630s saw a renewed concern by bishops of the Church of England to enforce uniformity in the church, by ensuring strict compliance with the style of worship set out in the ''Book of Common Prayer''. The Court of High Commission

The Court of High Commission was the supreme ecclesiastical court in England. Some of its powers was to take action against conspiracies, plays, tales, contempts, false rumors, books. It was instituted by the Crown in 1559 to enforce the Act of U ...

came to be the primary means for disciplining Puritan clergy who refused to conform. Unlike regular courts, in the Court of High Commission, there was no right against self-incrimination

In criminal law, self-incrimination is the act of exposing oneself generally, by making a statement, "to an accusation or charge of crime; to involve oneself or another ersonin a criminal prosecution or the danger thereof". (Self-incrimination ...

, and the Court could compel testimony.

Some bishops went further than the ''Book of Common Prayer'', and required their clergy to conform to levels of extra ceremonialism. As noted above, the introduction of altar rails to churches was the most controversial such requirement. Puritans were also dismayed by the re-introduction of images (e.g. stained glass windows) to churches which had been without religious images since the iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

of the Reformation.

Silencing of Puritan laymen

The ejection of non-conforming Puritan ministers from the Church of England in the 1630s provoked a reaction. Puritan laymen spoke out against Charles's policies, with the bishops the main focus of Puritan ire. The first, and most famous, critic of the Caroline regime was

The ejection of non-conforming Puritan ministers from the Church of England in the 1630s provoked a reaction. Puritan laymen spoke out against Charles's policies, with the bishops the main focus of Puritan ire. The first, and most famous, critic of the Caroline regime was William Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669), an English lawyer, voluble author, polemicist and political figure, was a prominent Puritan opponent of church policy under William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1633–1645). His views were presbyte ...

. In the late 1620s and early 1630s, Prynne had authored a number of works denouncing the spread of Arminianism in the Church of England, and was also opposed to Charles's marrying a Catholic. Prynne became a critic of morals at court.

Prynne was also a critic of societal morals more generally. Echoing John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ...

's criticism of the stage, Prynne penned a book, ''Histriomastix

''Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy'' is a critique of professional theatre and actors, written by the Puritan author and controversialist William Prynne.

Publication

While the publishing history of the work is not absolutel ...

'', in which he denounced the stage in vehement terms for its promotion of lascivious

Lascivious behavior is sexual behavior or conduct that is considered crude and offensive, or contrary to local moral or other standards of appropriate behavior. In this sense "lascivious" is similar in meaning to "lewd", "indecent", "lecherous", ...

ness. The book, which represents the highest point of the Puritans' attack on the English Renaissance theatre

English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642.

This is the style of the plays of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson ...

, attacked the stage as promoting lewdness. Unfortunately for Prynne, his book appeared at about the same time that Henrietta Maria became the first royal to ever perform in a masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masq ...

, Walter Montagu's ''The Shepherd's Paradise

''The Shepherd's Paradise'' was a Caroline era masque, written by Walter Montagu and designed by Inigo Jones. Acted in 1633 by Queen Henrietta Maria and her ladies in waiting, it was noteworthy as the first masque in which the Queen and her lad ...

'', in January 1633. ''Histriomastix'' was widely read as a Puritan attack on the queen's morality. Shortly after becoming Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud prosecuted Prynne in the Court of Star Chamber on a charge of seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection ...

. Unlike the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

courts, Star Chamber was allowed to order any punishment short of the death penalty, including torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

, for crimes which were founded on equity, not on law. Seditious libel was one of the "equitable crimes" which were prosecuted in the Star Chamber. Prynne was found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment, a £5000 fine, and the removal of part of his ears.

Prynne continued to publish from prison, and in 1637, he was tried before Star Chamber a second time. This time, Star Chamber ordered that the rest of Prynne's ears be cut off, and that he should be branded with the letters ''S L'' for "seditious libeller". (Prynne would maintain that the letters really stood for ''stigmata Laudis'' (the marks of Laud).) At the same trial, Star Chamber also ordered that two other critics of the regime should have their ears cut off for writing against Laudianism: John Bastwick

John Bastwick (1593–1654) was an English Puritan physician and controversial writer.

Early life

He was born at Writtle, Essex. He entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge, on 19 May 1614, but remained there only a very short time, and left the unive ...

, a physician who wrote anti-episcopal pamphlets; and Henry Burton.

A year later, the trio of "martyrs" were joined by a fourth,

A year later, the trio of "martyrs" were joined by a fourth, John Lilburne

John Lilburne (c. 161429 August 1657), also known as Freeborn John, was an English political Leveller before, during and after the English Civil Wars 1642–1650. He coined the term "'' freeborn rights''", defining them as rights with which eve ...

, who had studied under John Bastwick. Since 1632, it had been illegal to publish or import works of literature not licensed by the Stationers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers (until 1937 the Worshipful Company of Stationers), usually known as the Stationers' Company, is one of the livery companies of the City of London. The Stationers' Company was formed in ...

, and this allowed the government to view and censor any work prior to publication. Over the course of the 1630s, it became common for Puritans to have their works published in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

and then smuggled into England. In 1638, Lilburne was prosecuted in Star Chamber for importing religious works critical of Laudianism from Amsterdam. Lilburne thus began a course which would see him later hailed as "Freeborn John" and as the pre-eminent champion of "English liberties". In Star Chamber, he refused to plead to the charges against him on the grounds that the charges had been presented to him only in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. The court then threw him in prison and again brought him back to court and demanded a plea. Again, Lilburne demanded to hear in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

the charges brought against him. The authorities then resorted to flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on ...

him with a three-thonged whip on his bare back, as he was dragged by his hands tied to the rear of an oxcart from Fleet Prison to the pillory at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. He was then forced to stoop in the pillory where he still managed to distribute unlicensed literature to the crowds. He was then gagged. Finally he was thrown in prison. He was taken back to the court and again imprisoned.

Suppression of the Feoffees for Impropriations

Beginning in 1625, a group of Puritan lawyers, merchants, and clergymen (including

Beginning in 1625, a group of Puritan lawyers, merchants, and clergymen (including Richard Sibbes

Richard Sibbes (or Sibbs) (1577–1635) was an Anglican theologian. He is known as a Biblical exegete, and as a representative, with William Perkins and John Preston, of what has been called "main-line" Puritanism because he always remained in ...

and John Davenport) organized an organization known as the Feoffees

Under the feudal system in England, a feoffee () is a trustee who holds a fief (or "fee"), that is to say an estate in land, for the use of a beneficial owner. The term is more fully stated as a feoffee to uses of the beneficial owner. The use o ...

for the Purchase of Impropriations. The feoffees would raise funds to purchase lay impropriations and advowsons

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, a ...

, which would mean that the feoffees would then have the legal right to appoint their chosen candidates to benefices

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

and lectureships. Thus, this provided a mechanism both for increasing the number of preaching ministers in the country, and a way to ensure that Puritans could receive ecclesiastical appointments.

In 1629, Peter Heylin

Peter Heylyn or Heylin (29 November 1599 – 8 May 1662) was an English ecclesiastic and author of many polemical, historical, political and theological tracts. He incorporated his political concepts into his geographical books ''Microcosmu ...

, a Magdalen don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

, preached a sermon in St Mary's denouncing the Feoffees for Impropriations for sowing tares among the wheat. As a result of the publicity, William Noy

William Noy (1577 – 9 August 1634) was an English jurist.

He was born on the family estate of Pendrea in St Buryan, Cornwall. He left Exeter College, Oxford, without taking a degree, and entered Lincoln's Inn in 1594. From 1603 until his d ...

began to prosecute feoffees in the Exchequer court. The feoffees' defense was that all of the men they had had appointed to office conformed to the Church of England. Nevertheless, in 1632, the Feoffees for Impropriations were dissolved and the group's assets forfeited to the crown: Charles ordered that the money should be used to augment the salary of incumbents

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-ele ...

and used for other pious uses not controlled by the Puritans.

The Bishops' Wars, 1638–1640

As noted above, James had tried to bring the English and Scottish churches closer together. In the process, he had restored bishops to the Church of Scotland and forced the Five Articles of Perth on the Scottish church, moves which upset Scottish Presbyterians. Charles now further angered the Presbyterians by elevating the bishops' role in Scotland even higher than his father had, to the point where in 1635, the Archbishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews ( gd, Easbaig Chill Rìmhinn, sco, Beeshop o Saunt Andras) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews ( gd, Àrd-easbaig ...

, John Spottiswoode

John Spottiswoode (Spottiswood, Spotiswood, Spotiswoode or Spotswood) (1565 – 26 November 1639) was an Archbishop of St Andrews, Primate of All Scotland, Lord Chancellor, and historian of Scotland.

Life

He was born in 1565 at Greenbank in ...

, was made Lord Chancellor of Scotland

The Lord Chancellor of Scotland, formally the Lord High Chancellor, was a Great Officer of State in the Kingdom of Scotland.

Holders of the office are known from 1123 onwards, but its duties were occasionally performed by an official of lower s ...

. Presbyterian opposition to Charles reached a new height of intensity in 1637, when Charles attempted to impose a version of the Book of Common Prayer on the Church of Scotland. Although this book was drawn up by a panel of Scottish bishops, it was widely seen as an English import and denounced as Laud's Liturgy. What was worse, where the Scottish prayer book differed from the English, it seemed to be re-introducing old errors which had not yet been re-introduced in England. As a result, when the newly appointed Bishop of Edinburgh

The Bishop of Edinburgh, or sometimes the Lord Bishop of Edinburgh is the ordinary of the Scottish Episcopal Diocese of Edinburgh.

Prior to the Reformation, Edinburgh was part of the Diocese of St Andrews, under the Archbishop of St Andrews ...

, David Lindsay, rose to read the new liturgy in St. Giles' Cathedral, Jenny Geddes

Janet "Jenny" Geddes (c. 1600 – c. 1660) was a Scottish market-trader in Edinburgh who is alleged to have thrown a stool at the head of the minister in St Giles' Cathedral in objection to the first public use of the Church of Scotland ...

, a member of the congregation, threw her stool at Lindsay, thus setting off the Prayer Book Riot.

The Scottish prayer book was deeply unpopular with Scottish noblemen and gentry, not only on religious grounds, but also for nationalist reasons: Knox's Book of Common Order had been adopted as the liturgy of the national church by the

The Scottish prayer book was deeply unpopular with Scottish noblemen and gentry, not only on religious grounds, but also for nationalist reasons: Knox's Book of Common Order had been adopted as the liturgy of the national church by the Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council o ...

, whereas the Scottish parliament was not consulted in 1637 and the new prayer book imposed solely on the basis of Charles' alleged royal supremacy in the church, a doctrine which had never been accepted by either the Church or Parliament of Scotland. A number of leading noblemen drew up a document known as the National Covenant in February 1638. Those who subscribed to the National Covenant are known as Covenanters. Later that year, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivray, ...

ejected the bishops from the church.

In response to this challenge to his authority, Charles raised an army and marched on Scotland in the "First Bishops' War" (1639). The English Puritans – who had a longstanding opposition to the bishops (which had reached new heights in the wake of the Prynne, Burton, Bastwick, and Lilburne cases) – were deeply dismayed that the king was now waging a war to maintain the office of bishop. The First Bishops' War ended in a stalemate, since both sides lacked sufficient resources to defeat their opponents (in Charles' case, this was because he did not have enough revenues to wage a war since he had not called a Parliament since 1629), which led to the signing of the Treaty of Berwick (1639)

The Treaty of Berwick (also known as the Peace of Berwick or the Pacification of Berwick) was signed on 19 June 1639 between England and Scotland. It ended minor hostilities the day before. Archibald Johnston was involved in the negotiations befo ...

.

Charles intended to break the Treaty of Berwick at the next opportunity, and upon returning to London, began preparations for calling a Parliament that could pass new taxes to fund a war against the Scots and to re-establish episcopacy in Scotland. This Parliament – known as the Short Parliament because it only lasted three weeks – met in 1640. Unfortunately for Charles, many Puritan members were elected to the Parliament, and two critics of royal policies,

Charles intended to break the Treaty of Berwick at the next opportunity, and upon returning to London, began preparations for calling a Parliament that could pass new taxes to fund a war against the Scots and to re-establish episcopacy in Scotland. This Parliament – known as the Short Parliament because it only lasted three weeks – met in 1640. Unfortunately for Charles, many Puritan members were elected to the Parliament, and two critics of royal policies, John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

and John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of t ...

, emerged as loud critics of the king in the Parliament. These members insisted that Parliament had an ancient right to demand the redress of grievances and insisted that the nation's grievances with the past ten years of royal policies should be dealt with before Parliament granted Charles the taxes that he wanted. Frustrated, Charles dissolved Parliament three weeks after it opened.

In Scotland, the rebellious spirit continued to grow in strength. Following the signing of the Treaty of Berwick, the General Assembly of Scotland met in Edinburgh and confirmed the abolition of episcopacy in Scotland, and then went even further and declared that all episcopacy was contrary to the Word of God. When the Scottish Parliament met later in the year, it confirmed the Church of Scotland's position. The Scottish Covenanters now determined that Presbyterianism could never be confidently re-established in Scotland so long as episcopacy remained the order of the day in England. They therefore determined to invade England to help bring about the abolition of episcopacy. At the same time, the Scots (who had many contacts among the English Puritans) learned that the king was intending to break the Treaty of Berwick and make a second attempt at invading Scotland. When the Short Parliament was dissolved without having granted Charles the money he requested, the Covenanters determined that the time was ripe to launch a preemptive strike

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending (allegedly unavoidable) war ''shortly before'' that attack materializes. It ...

against English invasion. As such, in August 1640, the Scottish troops marched into northern England, beginning the "Second Bishops' War". Catching the king unawares, the Scots gained a major victory at the Battle of Newburn. The Scottish Covenanters thus occupied the northern counties of England and imposed a large fine of £850 a day on the king until a treaty could be signed. Believing that the king was not trustworthy, the Scottish insisted that the Parliament of England be a part of any peace negotiations. Bankrupted by the Second Bishops' War, Charles had little choice but to call a Parliament to grant new taxes to pay off the Scots. He therefore reluctantly called a Parliament which would not be finally dissolved until 1660, the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

.

The Canons of 1640 and the Et Cetera Oath

The

The Convocation of the English Clergy

The Convocations of Canterbury and York are the synodical assemblies of the bishops and clergy of each of the two provinces which comprise the Church of England. Their origins go back to the ecclesiastical reorganisation carried out under Arc ...

traditionally met whenever Parliament met, and was then dissolved whenever Parliament was dissolved. In 1640, however, Charles ordered Convocation to continue sitting even after he dissolved the Short Parliament because the Convocation had not yet passed the canons which Charles had had Archbishop Laud draw up and which confirmed the Laudian church policies as the official policies of the Church of England. Convocation dutifully passed these canons in late May 1640.

The preamble to the canons claims that the canons are not innovating in the church, but are rather restoring ceremonies from the time of Edward VI and Elizabeth I which had fallen into disuse. The first canon asserted that the king ruled by divine right; that the doctrine of Royal Supremacy was required by divine law

Divine law is any body of law that is perceived as deriving from a transcendent source, such as the will of God or godsin contrast to man-made law or to secular law. According to Angelos Chaniotis and Rudolph F. Peters, divine laws are typicall ...

; and that taxes were due to the king "by the law of God, nature, and nations." This canon led many MPs to conclude that Charles and the Laudian clergy were attempting to use the Church of England as a way to establish an absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

in England, and felt that this represented unwarranted clerical interference in the recent dispute between Parliament and the king over ship money

Ship money was a tax of medieval origin levied intermittently in the Kingdom of England until the middle of the 17th century. Assessed typically on the inhabitants of coastal areas of England, it was one of several taxes that English monarchs co ...

.

Canons against popery

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

and Socinianism were uncontroversial, but the canon against the sectaries was quite controversial because it was clearly aimed squarely at the Puritans. This canon condemned anyone who did not regularly attend service in their parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

or who attended only the sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

, not the full Prayer Book service. It went on to condemn anyone who wrote books critical of the discipline and government of the Church of England.

Finally, and most controversially, the Canons imposed an oath, known to history as the '' Et Cetera Oath'', to be taken by every clergyman

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, every Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Th ...

not the son of a nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteris ...

, all who had taken a degree in divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.[divine< ...](_blank)

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

, or physic, all registrars of the Consistory Court

A consistory court is a type of ecclesiastical court, especially within the Church of England where they were originally established pursuant to a charter of King William the Conqueror, and still exist today, although since about the middle of the ...

and Chancery Court, all actuaries

An actuary is a business professional who deals with the measurement and management of risk and uncertainty. The name of the corresponding field is actuarial science. These risks can affect both sides of the balance sheet and require asset man ...

, proctors and schoolmasters, all persons incorporated from foreign universities, and all candidates for ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

. The oath read

The Puritans were furious. They attacked the Canons of 1640 as unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

, claiming that Convocation was no longer legally in session after Parliament was dissolved. The campaign to enforce the Et Cetera Oath met with firm Puritan resistance, organized in London by Cornelius Burges

Cornelius Burges or Burgess, DD (1589? – 1665), was an English minister. He was active in religious controversy prior to and around the time of the Commonwealth of England and The Protectorate, following the English Civil War. In the years f ...

, Edmund Calamy the Elder

Edmund Calamy (February 160029 October 1666) was an English Presbyterian church leader and divine. Known as "the elder", he was the first of four generations of nonconformist ministers bearing the same name.

Early life

The Calamy family claimed ...

, and John Goodwin. The imposition of the Et Cetera Oath also resulted in the Puritans' pro-Scottish sympathies becoming even more widespread, and there were rumours – possible but never proven – that Puritan leaders were in treasonable communication with the Scottish during this period. Many Puritans refused to read the prayer for victory against the Scottish which they had been ordered to read.

The Long Parliament attacks Laudianism and considers the Root and Branch Petition, 1640–42

The elections to the Long Parliament in November 1640 produced a Parliament which was even more dominated by Puritans than the Short Parliament had been. Parliament's first order of business was therefore to move against

The elections to the Long Parliament in November 1640 produced a Parliament which was even more dominated by Puritans than the Short Parliament had been. Parliament's first order of business was therefore to move against Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, (13 April 1593 ( N.S.)12 May 1641), was an English statesman and a major figure in the period leading up to the English Civil War. He served in Parliament and was a supporter of King Charles I. From 1 ...

, who had served as Charles' Lord Deputy of Ireland since 1632. In the wake of the Second Bishops' War, Strafford had been raising an Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

Catholic army in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

which could be deployed against the Scottish Covenanters. Puritans were appalled that an army of Irish Catholics (whom they hated) would be deployed by the crown against the Scottish Presbyterians (whom they loved), and many English Protestants who were not particularly puritanical shared the sentiment. Having learned that Parliament intended to impeach him, Strafford presented the king with evidence of treasonable communications between Puritans in Parliament and the Scottish Covenanters. Nevertheless, through deft political manoeuvering, John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

, along with Oliver St John

Sir Oliver St John (; c. 1598 – 31 December 1673) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640-53. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil War.

Early life

St John was the son of Oliver S ...

and Lord Saye, managed to quickly have Parliament impeach

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

Strafford on charges of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

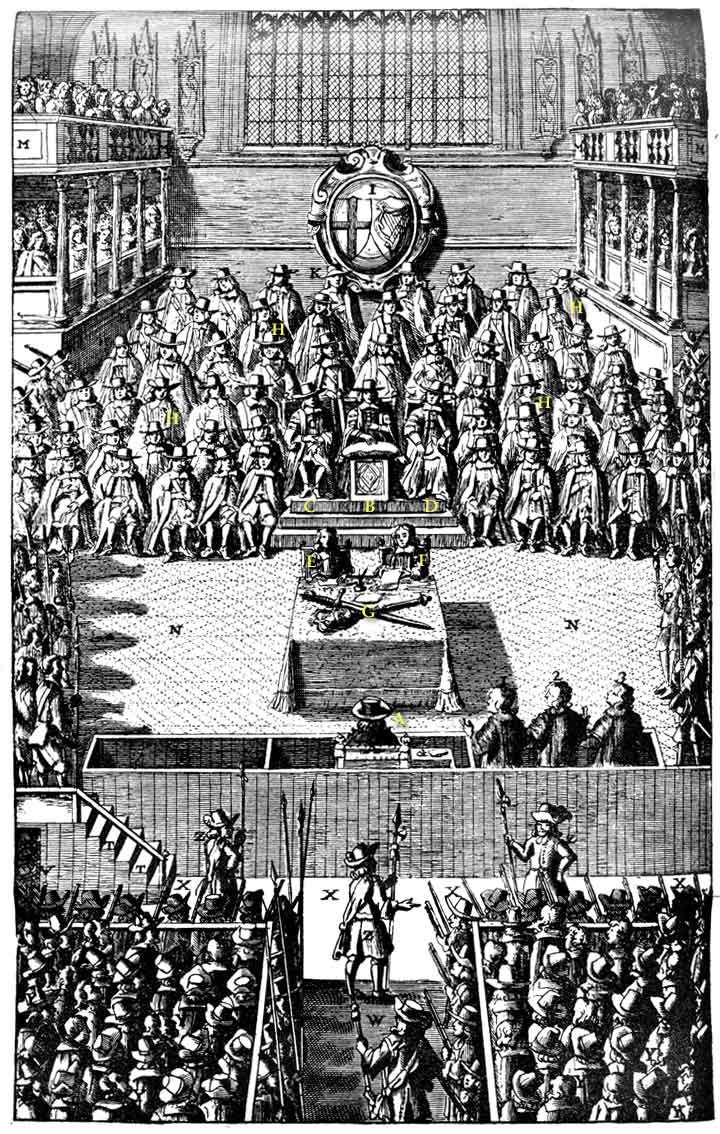

and Strafford was arrested. At his trial before the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, begun in January 1641, prosecutors argued that Strafford intended to use the Irish Catholic army against English Protestants. Strafford responded that the army was intended to be used against the rebellious Scots. Strafford was ultimately acquitted in April 1641 on the grounds that his actions did not amount to high treason. As a result, Puritan opponents of Strafford launched a bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder or writ of attainder or bill of penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and punishing them, often without a trial. As with attai ...

against Strafford in the House of Commons; in the wake of a revolt by the army, which had not been paid in months, the House of Lords also passed the bill of attainder. Charles, worried that the army would revolt further if they were not paid, and that the army would never be paid until Parliament granted funds, and that Parliament would not grant funds without Strafford's death, signed the bill of attainder in May 1641. Strafford was executed before a crowd of 200,000 on 12 May 1641.

The Puritans took advantage of Parliament's and the public's mood and organized the Root and Branch Petition, so called because it called for the abolition of episcopacy "root and branch". The Root and Branch Petition signed by 15,000 Londoners was presented to Parliament by a crowd of 1,500 on 11 December 1640. The Root and Branch Petition detailed many of the Puritans' grievances with Charles and the bishops. It complained that the bishops had silenced many godly ministers and made ministers afraid to instruct the people about "the doctrine of predestination, of free grace, of Perseverance of the saints, perseverance, of original sin remaining after baptism, of the Sabbath in Christianity, sabbath, the doctrine against universal grace, Predestination, election for faith foreseen, freewill against Antichrist, non-residents (ministers who did not live in their parishes), human inventions in God's worship". The Petition condemned the practices of bestowing temporal power on bishops and encouraging ministers to disregard temporal authority. The Petition condemned the regime for suppressing godly books while allowing the publication of popish, Arminian, and lewd books (such as Ovid's ''Ars Amatoria'' and the ballads of Martin Parker). The Petition also restated several of the Puritans' routine complaints: the Book of Sports, the placing of communion tables altar-wise, church beautification schemes, the imposing of oaths, the influence of Catholics and Arminians at court, and the abuse of excommunication by the bishops.

In December 1640, the month after it impeached Strafford, Parliament had also trial of Archbishop Laud, impeached Archbishop Laud on charges of high treason. He was accused of subverting true religion, assuming pope-like powers, attempting to reconcile the Church of England with the Roman Catholic Church, persecuting godly preachers, ruining the Church of England's relations with the Reformed churches on the Continent, promoting the war with Scotland, and a variety of other offenses. During this debate, Sir Harbottle Grimston, 2nd Baronet, Harbottle Grimston famously called Laud "the roote and ground of all our miseries and calamities ... the sty of all pestilential filth that hath infected the State and Government." Unlike Strafford, however, Laud's enemies did not move quickly to secure his execution. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London in February 1641.

In March 1641, the House of Commons passed the Clergy Act 1640, Bishops Exclusion Bill, which would have prevented the bishops from taking their seats in the

In December 1640, the month after it impeached Strafford, Parliament had also trial of Archbishop Laud, impeached Archbishop Laud on charges of high treason. He was accused of subverting true religion, assuming pope-like powers, attempting to reconcile the Church of England with the Roman Catholic Church, persecuting godly preachers, ruining the Church of England's relations with the Reformed churches on the Continent, promoting the war with Scotland, and a variety of other offenses. During this debate, Sir Harbottle Grimston, 2nd Baronet, Harbottle Grimston famously called Laud "the roote and ground of all our miseries and calamities ... the sty of all pestilential filth that hath infected the State and Government." Unlike Strafford, however, Laud's enemies did not move quickly to secure his execution. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London in February 1641.

In March 1641, the House of Commons passed the Clergy Act 1640, Bishops Exclusion Bill, which would have prevented the bishops from taking their seats in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

. The House of Lords, however, rejected this bill.

In May 1641, Henry Vane the Younger and Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

introduced the Root and Branch Bill, which had been drafted by Oliver St John

Sir Oliver St John (; c. 1598 – 31 December 1673) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640-53. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil War.

Early life

St John was the son of Oliver S ...

and which was designed to root out episcopacy in England "root and branch" along the lines advocated in the Root and Branch Petition. Many moderate MPs, such as Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland and Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, Edward Hyde, were dismayed: although they believed that Charles and Laud had gone too far in the 1630s, they were not prepared to abolish episcopacy. The debate over the Root and Branch Bill was intense – the Bill was finally rejected in August 1641. The division of MPs over this bill would form the basic division of MPs in the subsequent war, with those who favoured the Root and Branch Bill becoming Roundheads and those who defended the bishops becoming Cavaliers.

Unsurprisingly the debate surrounding the Root and Branch Bill occasioned a lively pamphlet controversy. Joseph Hall (bishop), Joseph Hall, the Bishop of Exeter, wrote a spirited defense of episcopacy entitled ''An Humble Remonstrance to the High Court of Parliament''. This drew forth a response from five Puritan authors, who wrote under the name Smectymnuus, an acronym based on their names (Stephen Marshall (English clergyman), Stephen Marshall, Edmund Calamy the Elder, Edmund Calamy, Thomas Young (1587-1655), Thomas Young, Matthew Newcomen, Matthew Newcomen, and William Spurstowe, William Spurstow). Smectymnuus's first pamphlet, ''An Answer to a booke entituled, An Humble Remonstrance. In Which, the Original of Liturgy and Episcopacy is Discussed'', was published in March 1641. It is believed that one of Thomas Young's former students, John Milton, wrote the postscript to the reply. (Milton published several anti-episcopal pamphlets in 1640–41). A prolonged series of answers and counter-answers followed.

Worried that the king would again quickly dissolve Parliament without redressing the nation's grievances,

Unsurprisingly the debate surrounding the Root and Branch Bill occasioned a lively pamphlet controversy. Joseph Hall (bishop), Joseph Hall, the Bishop of Exeter, wrote a spirited defense of episcopacy entitled ''An Humble Remonstrance to the High Court of Parliament''. This drew forth a response from five Puritan authors, who wrote under the name Smectymnuus, an acronym based on their names (Stephen Marshall (English clergyman), Stephen Marshall, Edmund Calamy the Elder, Edmund Calamy, Thomas Young (1587-1655), Thomas Young, Matthew Newcomen, Matthew Newcomen, and William Spurstowe, William Spurstow). Smectymnuus's first pamphlet, ''An Answer to a booke entituled, An Humble Remonstrance. In Which, the Original of Liturgy and Episcopacy is Discussed'', was published in March 1641. It is believed that one of Thomas Young's former students, John Milton, wrote the postscript to the reply. (Milton published several anti-episcopal pamphlets in 1640–41). A prolonged series of answers and counter-answers followed.

Worried that the king would again quickly dissolve Parliament without redressing the nation's grievances, John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

pushed through an Act against Dissolving Parliament without its own Consent; desperately in need of money, Charles had little choice but to consent to the Act. The Long Parliament then sought to undo the more unpopular aspects of the past eleven years. Star Chamber, which had been used to silence Puritan laymen, was abolished in July 1641. The Court of High Commission was also abolished at this time. Parliament ordered Prynne, Burton, Bastwick, and Lilburne released from prison, and they returned to London in triumph.

In October 1641, Irish Catholic gentry launched the Irish Rebellion of 1641, throwing off English domination and creating Confederate Ireland. English parliamentarians were terrified that an Irish army might rise to massacre English Protestants. In this atmosphere, in November 1641, Parliament passed the Grand Remonstrance, detailing over 200 points which Parliament felt that the king had acted illegally in the course of the Personal Rule. The Grand Remonstrance marked a second moment at which a number of the more moderate, non-Puritan members of Parliament (e.g. Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland, Viscount Falkland and Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, Edward Hyde) felt that Parliament had gone too far in its denunciations of the king and was showing too much sympathy for the rebellious Scots.

When the bishops attempted to take their seats in the House of Lords in late 1641, a pro-Puritan, anti-episcopal mob, probably organized by John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

, prevented them from doing so. The Clergy Act 1640, Bishops Exclusion Bill was re-introduced in December 1641, and this time, the mood of the country was such that neither the House of Lords nor Charles felt strong enough to reject the bill. The Bishops Exclusion Act prevented those in holy orders from exercising any State (polity), temporal jurisdiction or authority after 5 February 1642; this extended to taking a seat in Parliament or membership of the Privy Council. Any acts carried out with such authority after that date by a member of the clergy were to be considered void.

In this period, Charles became increasingly convinced that a number of Puritan-influenced members of Parliament had treasonously encouraged the Scottish Covenanters to invade England in 1640, leading to the Second Bishops' War. As such, when he heard that they were planning to impeach Henrietta Maria of France, the Queen for participation in Catholic plots, he determined to arrest Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester, Lord Mandeville as well as five MPs, known to history as the Five Members: John Pym

John Pym (20 May 1584 – 8 December 1643) was an English politician, who helped establish the foundations of Parliamentary democracy. One of the Five Members whose attempted arrest in January 1642 sparked the First English Civil War, his use ...

, John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of t ...

, Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig, Sir Arthur Haselrig, and William Strode. Charles famously entered the House of Commons personally on 4 January 1642, but the members had already fled.

Following his failed attempt to arrest the Five Members, Charles realized that he was not only immensely unpopular among parliamentarians, he was also in danger of London's pro-Puritan, anti-episcopal, and increasingly anti-royal Crowd, mob. As such, he and his family retreated to Oxford and invited all loyal parliamentarians to join him. He began raising an army under George Goring, Lord Goring.

Parliament passed a Militia Ordinance which raised a militia, but provided that the militia should be controlled by Parliament. The king, of course, refused to sign this bill. A major split between Parliament and the king occurred on 15 March 1642, when Parliament declared that "the People are bound by the Ordinance for the Militia, though it has not received the Royal Assent", the first time a Parliament had declared its acts to operate without receiving royal assent. Under these circumstances, the political nation began to divide itself into Roundheads and Cavaliers. The first clash between the royalists and the parliamentarians came in the April 1642 Siege of Hull (1642), Siege of Hull, which began when the military governor appointed by Parliament, Sir John Hotham, 1st Baronet, Sir John Hotham refused to allow Charles' forces access to military material in Kingston upon Hull. In August, the king officially raised his standard at Nottingham and the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

was underway.

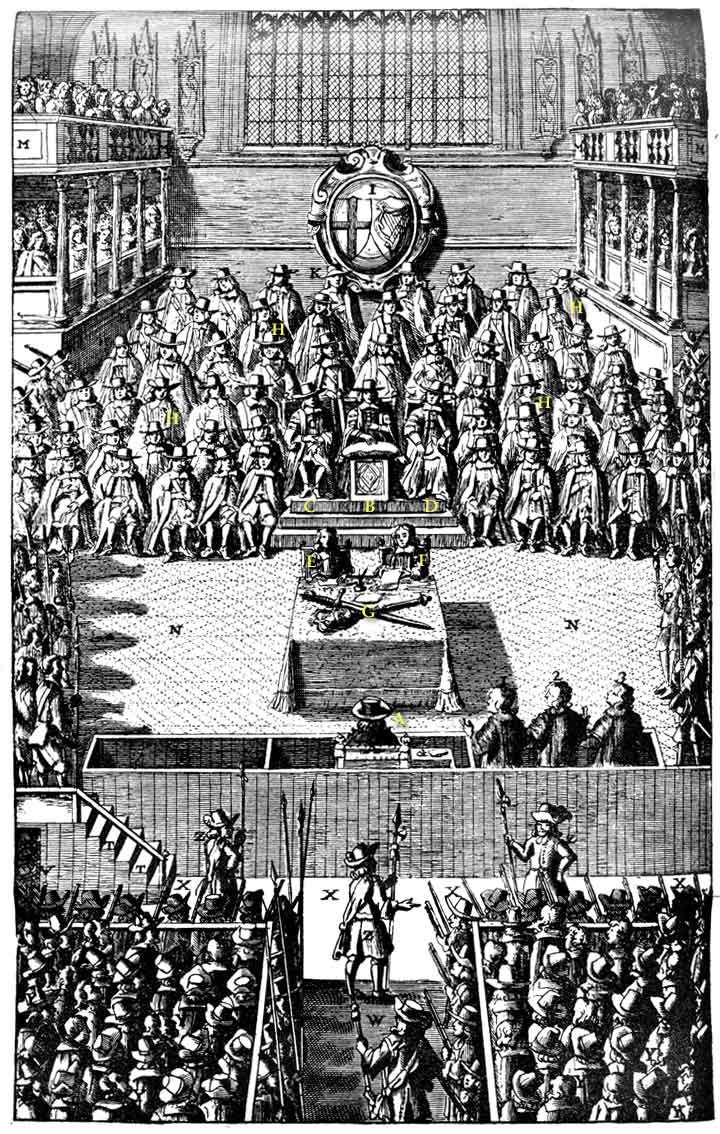

The Westminster Assembly, 1643–49

In 1642, the most ardent defenders of episcopacy in the

In 1642, the most ardent defenders of episcopacy in the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

left to join King Charles on the battlefield. However, although Civil War was beginning, Parliament was initially reluctant to pass legislation without it receiving royal assent. Thus, between June 1642 and May 1643, Parliament passed legislation providing for a religious assembly five times, but these bills did not receive royal assent and thus died. By June 1643, however, Parliament was willing to defy the king and call a religious assembly without the king's assent. This assembly, the Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

, had its first meeting in the Henry VII Chapel of Westminster Abbey on 1 July 1643. (In later sessions, the Assembly would meet in th

Jerusalem Chamber

)

The Assembly was charged with drawing up a new liturgy to replace the Book of Common Prayer