Lajjun on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lajjun ( ar, اللجّون, ''al-Lajjūn'') was a large

3

/ref>Khalidi, 1992, p. 334 The place where it established its camp was known as

p.493

A number of Muslim kings and prominent persons passed through the village, including Ayyubid sultan

41

When the Mamluks were completely uprooted and Selim returned to

Leiden University Open Access, p.29, p.32. After a short period in which the Tarabays were in a state of rebellion, tensions suddenly died down and the Ottomans appointed Ali ibn Tarabay as the governor of Lajjun in 1559. His son Assaf Tarabay ruled Lajjun from 1571 to 1583. During his reign, he extended Tarabay power and influence to

42

In 1579, Assaf, referred to as the " Sanjaqbey of al-Lajjun," is mentioned as the builder of a mosque in the nearby village of al-Tira. Assaf was deposed and banished in 1583 to the island of

Much of the Lajjun district territories were actually taxed by the stronger families of Sanjak Nablus by 1723. Later in the 18th century, Lajjun was replaced by Jenin as the administrative capital of the ''sanjak'' which now included the Sanjak of

Much of the Lajjun district territories were actually taxed by the stronger families of Sanjak Nablus by 1723. Later in the 18th century, Lajjun was replaced by Jenin as the administrative capital of the ''sanjak'' which now included the Sanjak of

39

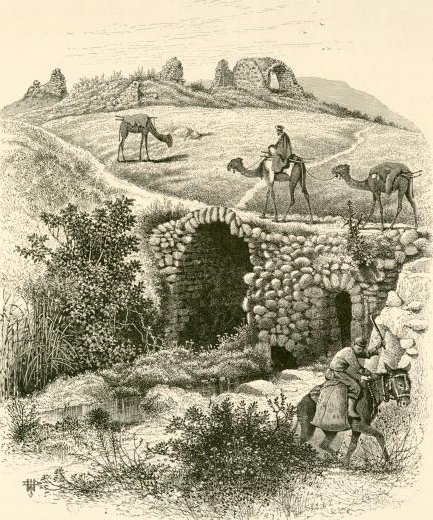

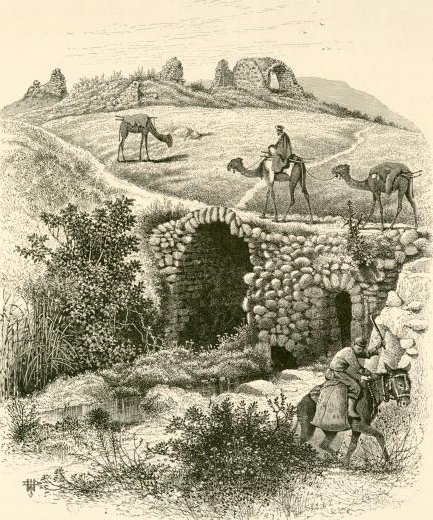

Edward Robinson visited in 1838, and noted that the ''khan'', which Maundrell commented on, was for the accommodation of the caravans passing on the great road between Egypt and Damascus which comes from the western plain along the coast, over the hills to Lajjun, and enters the plain of

Edward Robinson visited in 1838, and noted that the ''khan'', which Maundrell commented on, was for the accommodation of the caravans passing on the great road between Egypt and Damascus which comes from the western plain along the coast, over the hills to Lajjun, and enters the plain of

6

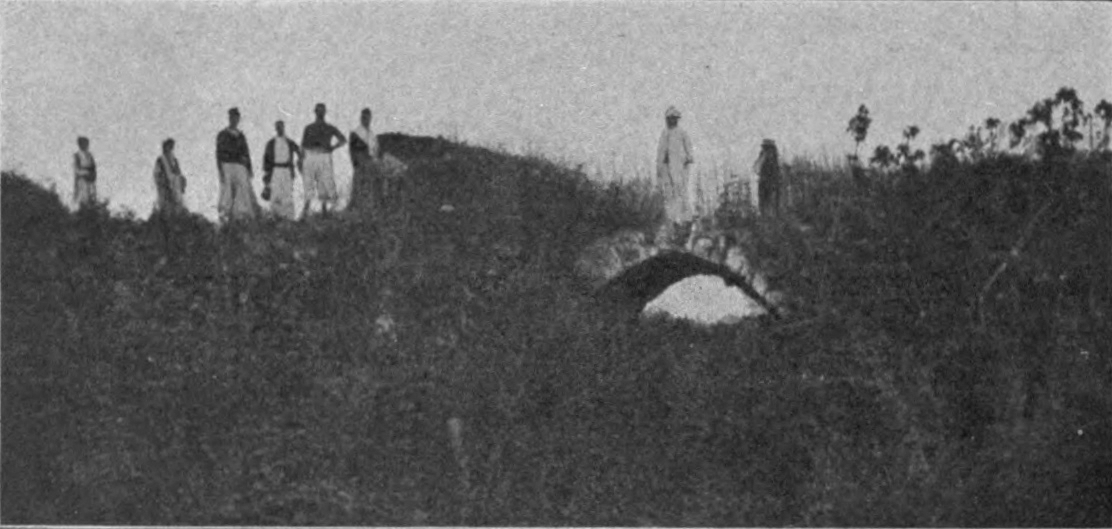

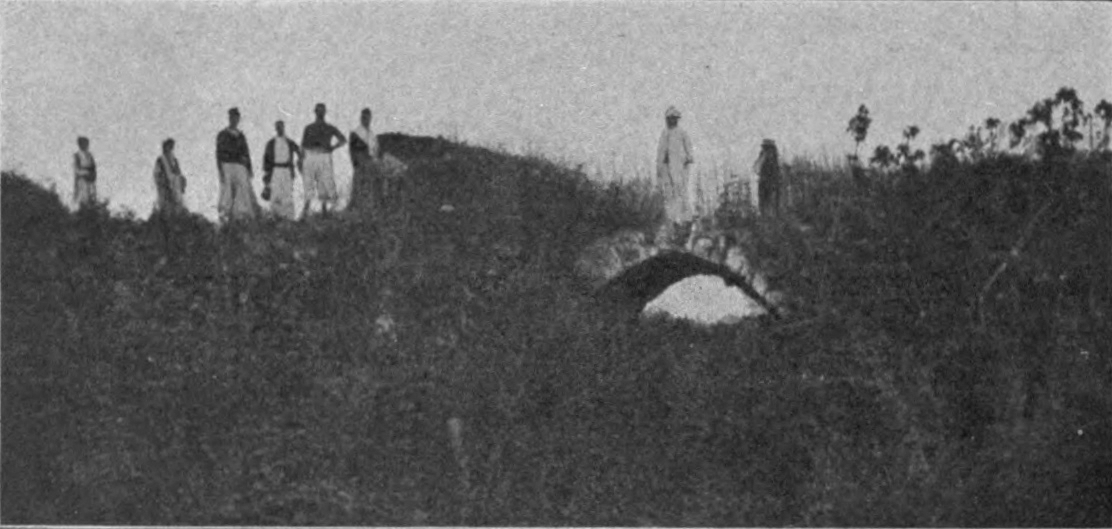

/ref> Andrew Petersen, inspecting the place in 1993, noted that the principal extant buildings at the site are the ''khan'' and a bridge. The bridge, which crosses a major tributary of the

Andrew Petersen, inspecting the place in 1993, noted that the principal extant buildings at the site are the ''khan'' and a bridge. The bridge, which crosses a major tributary of the

al-Lajjun

Jerusalemites.Khalidi, 1992, p.335 Gradually, they settled in the village, building their houses around the springs. In 1903–1905, Schumacher excavated Tell al-Mutasallim (ancient Megiddo) and some spots in Lajjun. Schumacher wrote that ''Lajjun'' ("el-Leddschōn") is properly the name of the stream and surrounding farmlands, and calls the village along the stream ''Ain es-Sitt''. Which, he noted, "consists of only nine shabby huts in the midst of ruins and heaps of dung." and a few more

Lajjun had a school that was founded in 1937 and that had an enrollment of 83 in 1944. It was located in the quarter belonging to the al-Mahajina al-Fawqa clan, that is, in Khirbat al-Khan. In 1943, one of the large landowners in the village financed the construction of a mosque, built of white stone, in the al-Ghubariyya (eastern) quarter. Another mosque was also established in the al-Mahamid quarter during the same period, and was financed by the residents themselves. It was a four-year elementary school for boys.

In

Lajjun had a school that was founded in 1937 and that had an enrollment of 83 in 1944. It was located in the quarter belonging to the al-Mahajina al-Fawqa clan, that is, in Khirbat al-Khan. In 1943, one of the large landowners in the village financed the construction of a mosque, built of white stone, in the al-Ghubariyya (eastern) quarter. Another mosque was also established in the al-Mahamid quarter during the same period, and was financed by the residents themselves. It was a four-year elementary school for boys.

In

17

/ref>Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970

p.55

The seven hamlets were

It was later afforestation, planted with forest trees. In 1992

319

/ref> By 2007 it was evacuated and sealed up. In the 2000s, 486 families from Umm al-Fahm (formerly from Lajjun), through Adalah, motioned to nullify the confiscation of that particular block. The district court ruled against the plaintiffs in 2007, and the supreme court held the decision in 2010.

30

/ref> In the

69

/ref> In that year, there were 162 houses in the village.

Palestine Remembered. At the end of 1940, Lajjun had 1,103 inhabitants. The prominent families of al-Lajjun were the Jabbarin, Ghubayriyya, Mahamid and the Mahajina. Around 80% of its inhabitants fled to Umm al-Fahm, where they currently live as

Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2004

Survey Permit # A-4227

The Excavation of Armageddon

'' Oriental Institute Communications 4, University of Chicago Press * * * *Heyd, Uriel (1960): ''Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552-1615'', Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cited in Petersen (2002) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * al-Qawuqji, F. (1972)

Memoirs of al-Qawuqji, Fauzi

in ''

"Memoirs, 1948, Part I" in 1, no. 4 (Sum. 72): 27-58.

pdf-file, downloadable

"Memoirs, 1948, Part II" in 2, no. 1 (Aut. 72): 3-33.

pdf-file, downloadable * * * * The edition follows the same pagination the German publication at . *State of Israel, "Hydrographic list of the map of Israel",[ ] :

**

**

*

*Yotam Tepper, Tepper, Y. 2003. ''Survey of the Legio Area near Megiddo: Historical and Geographical Research''. MA thesis, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv.

* Thomsen, Peter (1966). ''Loca Sancta'', Hildesheim

*

*

*

*

*

Welcome To al-Lajjun

palestineremembered.com

Lajjun

from

Wikimedia commons

Al-Lajjon

from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

from the

Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

village in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

, located northwest of Jenin and south of the remains of the biblical city of Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Junction, ...

. The Israeli kibbutz of Megiddo, Israel

Megiddo ( he, מְגִדּוֹ، ar, المجیدو) is a kibbutz in northern Israel, built in 1949 on the site of the depopulated Arab village of Lajjun. Located in the Jezreel Valley, it falls under the jurisdiction of Megiddo Regional Counci ...

was built on the land from 1949.

Named after an early Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

camp in Syria Palaestina

Syria Palaestina (literally, "Palestinian Syria";Trevor Bryce, 2009, ''The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia''Roland de Vaux, 1978, ''The Early History of Israel'', Page 2: "After the revolt of Bar Cochba in 135 ...

province called "Legio

Legio was a Roman military camp south of Tel Megiddo in the Roman province of Galilee.

History

Following the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136CE), Legio VI Ferrata was stationed at Legio near Caparcotna. The approximate location of the camp of the L ...

", predating the village at that location, Lajjun's history of habitation spanned some 2,000 years. Under Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

rule it was the capital of a subdistrict A subdistrict or sub-district is an administrative division that is generally smaller than a district.

Equivalents

* Administrative posts of East Timor, formerly Portuguese-language

* Kelurahan, in Indonesia

* Mukim, a township in Brunei, In ...

, during Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

rule it served as an important station in the postal route, and during Ottoman rule it was the capital of a district that bore its name. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire towards the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Lajjun and all of Palestine was placed under the administration of the British Mandate. The village was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

, when it was captured by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Most of its residents subsequently fled and settled in the nearby town of Umm al-Fahm

Umm al-Fahm ( ar, أمّ الفحم, ''Umm al-Faḥm''; he, אוּם אֶל-פַחֶם ''Um el-Faḥem'') is a city located northwest of Jenin in the Haifa District of Israel. In its population was , nearly all of whom are Arab citizens of I ...

.

Etymology

The name ''Lajjun'' derives from the Roman name ''Legio'', referring to the Roman legion stationed there. In the 3rd century, the town was renamed ''Maximianopolis'' ("City of Maximian") byDiocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

in honor of Maximian

Maximian ( la, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus; c. 250 – c. July 310), nicknamed ''Herculius'', was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was ''Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his ...

, his co-emperor,Tepper 2003 but the inhabitants continued to use the old name. Under the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, the name was Arabicized

Arabization or Arabisation ( ar, تعريب, ') describes both the process of growing Arab influence on non-Arab populations, causing a language shift by the latter's gradual adoption of the Arabic language and incorporation of Arab culture, aft ...

into ''al-Lajjûn'' or ''el-Lejjûn'', which was used until the Crusaders conquered Palestine in 1099. The Crusaders restored the Roman name ''Legio'', and introduced new names such as ''Ligum'' and ''le Lyon'', but after the town was reconquered by the Muslims in 1187, ''al-Lajjun'' once again became its name.

Geography

Modern Lajjun was built on the slopes of three hills, roughly 135–175 meters above sea level, located on the southwestern edge of theJezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

(''Marj ibn Amer''). Jenin, the entire valley, and Nazareth range are visible from it. The village was located on both the banks of a stream, a tributary of Kishon River

The Kishon River ( he, נחל הקישון, ; ar, نهر المقطع, , or , – ''the river of slaughter'' or ''dismemberment''; alternative Arabic, ) is a river in Israel that flows into the Mediterranean Sea near the city of Haifa.

Course ...

. The stream flows to the north and then east over before arriving at Lajjun. That section is called Wadi es-Sitt (valley of the lady) in Arabic, The northern quarter was built in close proximity to a number of springs, including 'Ayn al Khalil, 'Ayn Nasir, 'Ayn Sitt Leila, and 'Ayn Jumma, collectively known as 'Uyun Seil Lajjun.State of Israel, Hydrographic list part 2, items no. 282-286,295. The eastern quarter was next to 'Ayn al Hajja. From Lajjun onward the stream is called Wadi al-Lajjun in Arabic. In Hebrew, the Israeli Government Naming Committee

Government Naming Committee ( he, ועדת השמות הממשלתית, sometimes referred as National Naming Committee or Government Names Committee) is a public committee appointed by the Government of Israel, which deals with the designation ...

decided in 1958 to use the name Nahal Qeni ( he, נַחַל קֵינִי) for the entire length of the stream, based on its ancient identification (see below).State of Israel, Hydrographic list part 1, item no. 177 (in list and indices). Lajjun is bordered by Tall al-Mutsallem to the northeast, and by Tall al-Asmar to the northwest. Lajjun, which was linked by secondary roads to the Jenin-Haifa road, and the road that led southwest to the town of Umm al-Fahm, laid close to the junctions of the two highways.

Nearby localities included, the destroyed village of Ayn al-Mansi to the northwest, and the surviving villages of Zalafa

Zalafa ( ar, زلفة, he, זלפה) is an Arab village in Israel's Haifa District. The village is in the Wadi Ara area of the northern Triangle, northeast of Umm al-Fahm. Since 1996, it has been under the jurisdiction of the Ma'ale Iron local ...

to the south, Bayada and Musheirifa

Al-Musheirifa ( ar, المشيرفة, he, מושיריפה or ) is an Arab village in Israel's Haifa District. The village is located in the Wadi Ara area of the northern Triangle, northeast of Umm al-Fahm. Since 1996, it has been under the juri ...

to the southwest, and Zububa

Zububa ( ar, زبوبا) is the northernmost Palestinian village in the West Bank, located 10 km Northwest of the city of Jenin in the northern West Bank. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the town had an estimated ...

(part of the Palestinian territories

The Palestinian territories are the two regions of the former British Mandate for Palestine that have been militarily occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967, namely: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. The I ...

) to the southeast. The largest town near al-Lajjun was Umm al-Fahm, to the south.

History

Bronze and Iron Ages

Lajjun is about south ofTel Megiddo

Tel Megiddo ( he, תל מגידו; ar, مجیدو, Tell el- Mutesellim, ''lit.'' "Mound of the Governor"; gr, Μεγιδδώ, Megiddo) is the site of the ancient city of Megiddo, the remains of which form a tell (archaeological mound), situat ...

, also called Tell al-Mutasallim, which is identified with ancient Megiddo. During the rule of the Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ites and then the Israelite

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

s, Megiddo, located on the military road leading from Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and in a commanding situation, was heavily fortified by both peoples.

Lajjun stream has been identified with the brook Kina, or Qina, which is mentioned in the Egyptian descriptions of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

's Battle of Megiddo. According to the reconstruction of Harold Hayden Nelson, the entire battle was fought in the valley, between the three quarters of modern Lajjun.Nelson (1921) 913/ref> However, both Na'aman and Zertal suggested alternative locations for Qina. Some biblical scholars proposed that this stream is also the battle site referred to as " Waters of Megiddo" in the Song of Deborah

According to the Book of Judges, Deborah ( he, דְּבוֹרָה, ''Dəḇōrā'', "bee") was a prophetess of the God of the Israelites, the fourth Judge of pre-monarchic Israel and the only female judge mentioned in the Bible. Many scholars ...

, while others maintain that any part of the Kishon river system is equally likely. In the same context, attests to the presence of a branch of the Kenite

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Kenites ( or ; he, ''Qēinī'') were a nomadic tribe in the ancient Levant. The Kenites were coppersmiths and metalworkers. According to some scholars, they are descendants of Cain, Harris, Stephen L., Underst ...

clan somewhere in the area; relating this name to Thutmose's ''Annals'', scholars like Shmuel Yeivin

Shemuel Yeivin (Hebrew: שמואל ייבין; September 2, 1896 – February 28, 1982), also spelled Shmuel, was an Israeli archaeologist and the first director of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Early life and education

Shemuel Yeivin was bo ...

theorized that the name Qina derives from ''qyni'' ( he, קיני). Donald B. Redford

Donald Bruce Redford (born September 2, 1934) is a Canadian Egyptologist and archaeologist, currently Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies at Pennsylvania State University. He is married to Susan Redford, who is also an Egyptolo ...

noted that the Egyptian transliteration might be of "qayin".

Roman era

Modern-day historical geographers have placed theSecond Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

village of Kefar ʿUthnai () in the confines of the Arab village, and which place-name underwent a change after a Roman Legion had camped there. It appears in Latin characters under its old name ''Caporcotani'' in the Tabula Peutingeriana

' (Latin Language, Latin for "The Peutinger Map"), also referred to as Peutinger's Tabula or Peutinger Table, is an illustrated ' (ancient Roman road map) showing the layout of the ''cursus publicus'', the road network of the Roman Empire.

The m ...

Map, and lay along the Roman road from Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

to Scythopolis (Beit Shean

Beit She'an ( he, בֵּית שְׁאָן '), also Beth-shean, formerly Beisan ( ar, بيسان ), is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is be ...

). Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

'' V, 15: 3) also mentions the site in the second century CE, referring to the place under its Latin appellation, Caporcotani, and where he mentions it as one of the four cities of the Galilee, with Sepphoris

Sepphoris (; grc, Σέπφωρις, Séphōris), called Tzipori in Hebrew ( he, צִפּוֹרִי, Tzipori),Palmer (1881), p115/ref> and known in Arabic as Saffuriya ( ar, صفورية, Ṣaffūriya) since the 7th century, is an archaeolog ...

, Julias and Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Fo ...

. Among the village's famous personalities was Rabban Gamliel

Gamaliel the Elder (; also spelled Gamliel; he, רַבַּן גַּמְלִיאֵל הַזָּקֵן ''Rabban Gamlīʾēl hazZāqēn''; grc-koi, Γαμαλιὴλ ὁ Πρεσβύτερος ''Gamaliēl ho Presbýteros''), or Rabban Gamaliel I, ...

. After the Bar Kochba Revolt—a Jewish uprising against the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

—had been suppressed in 135 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

ordered a second Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

, ''Legio VI Ferrata

Legio VI Ferrata ("Sixth Ironclad Legion") was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. In 30 BC it became part of the emperor Augustus's standing army. It continued in existence into the 4th century. A ''Legio VI'' fought in the Roman Republican ci ...

'' (6th "Ironclad" Legion), to be stationed in the north of the country to guard the Wadi Ara

Wadi Ara ( ar, وادي عارة, he, ואדי עארה) or Nahal 'Iron ( he, נחל עירון), is a valley and its surrounding area in Israel populated mainly by Arab Israelis. The area is also known as the "Northern Triangle".

Wadi Ara is ...

region, a crucial line of communication between the coastal plain

A coastal plain is flat, low-lying land adjacent to a sea coast. A fall line commonly marks the border between a coastal plain and a piedmont area. Some of the largest coastal plains are in Alaska and the southeastern United States. The Gulf Coa ...

of Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and the Jezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

.Pringle, 1998, p3

/ref>Khalidi, 1992, p. 334 The place where it established its camp was known as

Legio

Legio was a Roman military camp south of Tel Megiddo in the Roman province of Galilee.

History

Following the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136CE), Legio VI Ferrata was stationed at Legio near Caparcotna. The approximate location of the camp of the L ...

.

In the 3rd century CE, when the army was removed, Legio became a city and its name was augmented with the adjectival Maximianopolis. Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian ...

mentions the village in his ''Onomasticon'', under the name ''Legio''.

Early Muslim period

Some Muslim historians believe the site of theBattle of Ajnadayn

The Battle of Ajnadayn ( ar, معركة أجنادين) was fought in July or August 634 ( Jumada I or II, 13 AH), in a location close to Beit Guvrin in present-day Israel; it was the first major pitched battle between the Byzantine (Roman) ...

between the Muslim Arabs

Arab Muslims ( ar, العرب المسلمون) are adherents of Islam who identify linguistically, culturally, and genealogically as Arabs. Arab Muslims greatly outnumber other ethnoreligious groups in the Middle East and North Africa. Arab M ...

and the Byzantines in 634 CE was at Lajjun. Following the Muslim victory, Lajjun, along with most of Palestine, and southern Syria

Southern Syria (سوريا الجنوبية, ''Suriyya al-Janubiyya'') is the southern part of the Syria region, roughly corresponding to the Southern Levant. Typically it refers chronologically and geographically to the southern part of Ottom ...

were incorporated into the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

. According to medieval geographers Estakhri

Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn Muhammad al-Farisi al-Istakhri () (also ''Estakhri'', fa, استخری, i.e. from the Iranian city of Istakhr, b. - d. 346 AH/AD 957) was a 10th-century travel-author and geographer who wrote valuable accounts in Arab ...

and Ibn Hawqal

Muḥammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Ḥawqal (), also known as Abū al-Qāsim b. ʻAlī Ibn Ḥawqal al-Naṣībī, born in Nisibis, Upper Mesopotamia; was a 10th-century Arab Muslim writer, geographer, and chronicler who travelled during the ye ...

, Lajjun was the northernmost town of Jund Filastin

Jund Filasṭīn ( ar, جُنْد فِلَسْطِيْن, "the military district of Palestine") was one of the military districts of the Umayyad and Abbasid province of Bilad al-Sham (Levant), organized soon after the Muslim conquest of the Lev ...

(military district of Palestine).

A hoard of dinars

The dinar () is the principal currency unit in several countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and its historical use is even more widespread.

The modern dinar's historical antecedents are the gold dinar and the silver dirham, the main coin o ...

dating from the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

era have been found at Lajjun.

The 10th-century Persian geographer Ibn al-Faqih

Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani ( fa, احمد بن محمد ابن الفقيه الهمذانی) (fl. 902) was a 10th-century Persian historian and geographer, famous for his ''Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan'' ("Concise Book of Lands ...

wrote of a local legend related by the people of Lajjun regarding the source of the abundant spring used as the town's primary water source over the ages: there is just outside al-Lajjun a large stone of round form, over which is built a dome, which they call theIn 940, Ibn Ra'iq, during his conflict over control of Syria with theMosque A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...ofAbraham Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew .... A copious stream of water flows from under the stone and it is reported that Abraham struck the stone with his staff, and there immediately flowed from it water enough to suffice for the supply of the people of the town, and also to water their lands. The spring continues to flow down to the present day.Ibn al-Faqih quoted in le Strange, 1890,

p.492

Ikhshidid

The Ikhshidid dynasty (, ) was a Turkic mamluk dynasty who ruled Egypt and the Levant from 935 to 969. Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, a Turkic mamluk soldier, was appointed governor by the Abbasid Caliph al-Radi. The dynasty carried the Arabic t ...

s of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, fought against them in an indecisive battle at Lajjun. During the battle, Abu Nasr al-Husayn—the Ikhshidid general and brother of the Ikhshidid ruler, Muhammad ibn Tughj

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Ṭughj ibn Juff ibn Yiltakīn ibn Fūrān ibn Fūrī ibn Khāqān (8 February 882 – 24 July 946), better known by the title al-Ikhshīd ( ar, الإخشيد) after 939, was an Abbasid commander and governor who becam ...

—was killed. Ibn Ra'iq was remorseful at the sight of Husayn's dead body and offered his seventeen-year-old son, Abu'l-Fath Muzahim, to Ibn Tughj "to do with him whatever they saw fit". Ibn Tughj was honored by Ibn Ra'iq's gesture; instead of executing Muzahim, he gave the latter several gifts and robes, then married him to his daughter Fatima.

In 945, the Hamdanid

The Hamdanid dynasty ( ar, الحمدانيون, al-Ḥamdāniyyūn) was a Twelver Shia Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib Christian tribe of Mesopotamia and Eastern Ara ...

s of Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

and the Ikhshidids fought a battle in Lajjun. It resulted in an Ikhshidid victory putting a halt to Hamdanid expansion southward under the leadership of Sayf al-Dawla

ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbdallāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn al-Ḥārith al-Taghlibī ( ar, علي بن أبو الهيجاء عبد الله بن حمدان بن الحارث التغلبي, 22 June 916 – 9 February 967), more commonly known ...

. The Jerusalemite geographer, al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

, wrote in 985 that Lajjun was "a city on the frontier of Palestine, and in the mountain country ... it is well situated and is a pleasant place". Moreover, it was the center of a ''nahiya

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

'' (subdistrict) of Jund al-Urdunn

Jund al-Urdunn ( ar, جُـنْـد الْأُرْدُنّ, translation: "The military district of Jordan") was one of the five districts of Bilad al-Sham (Islamic Syria) during the early Islamic period. It was established under the Rashidun and ...

( (military district of Jordan), which also included the towns of Nazareth

Nazareth ( ; ar, النَّاصِرَة, ''an-Nāṣira''; he, נָצְרַת, ''Nāṣəraṯ''; arc, ܢܨܪܬ, ''Naṣrath'') is the largest city in the Northern District of Israel. Nazareth is known as "the Arab capital of Israel". In ...

and Jenin.

Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

When the Crusaders invaded and conquered theLevant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

from the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

s in 1099, al-Lajjun's Roman name, "Legio", was restored and the town formed a part of the lordship of Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

. During this time, Christian settlement in Legio grew significantly. John of Ibelin records that the community "owed the service of 100 sergeants". Bernard, the archbishop of Nazareth granted some of the tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

s of Legio to the hospital of the monastery of St. Mary in 1115, then in 1121, he extended the grant to include all of Legio, including its church as well as the nearby village of Ti'inik

Ti'inik, also transliterated Ti’innik ( ar, تعّنك), or Ta'anakh/Taanach ( he, תַּעְנַךְ), is a Palestinian village, located 13 km northwest of the city of Jenin in the northern West Bank.

According to the Palestinian Central Burea ...

. By 1147, the de Lyon family controlled Legio, but by 1168, the town was held by Payen, the lord of Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

. Legio had markets, a town oven and held other economic activities during this era. In 1182, the Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

s raided Legio, and in 1187, it was captured by them under the leadership of Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

's nephew Husam ad-Din 'Amr and consequently its Arabic name was restored.

In 1226, Arab geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known fo ...

writes of the Mosque of Abraham in Lajjun, the town's "copious stream", and that it was a "part of the Jordan Province".le Strange, 1890p.493

A number of Muslim kings and prominent persons passed through the village, including Ayyubid sultan

al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cr ...

, who gave his daughter 'Ashura' in marriage to his nephew while visiting the town in 1231. The Ayyubids ceded Lajjun to the Crusaders in 1241, but it fell to the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s under Baibars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari ( ar, الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس البندقداري, ''al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Rukn al-Dīn Baybars al-Bunduqdārī'') (1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), of Turkic Kipchak ...

in 1263. A year later, a party of Templars

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

and Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

raided Lajjun and took 300 men and women captives to Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

. In the treaty between Sultan Qalawun

( ar, قلاوون الصالحي, – November 10, 1290) was the seventh Bahri Mamluk sultan; he ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1290.

He was called (, "Qalāwūn the Victorious").

Biography and rise to power

Qalawun was a Kipchak, ancient Turki ...

and the Crusaders on 4 June 1283, Lajjun was listed as the Mamluk territory.

By 1300, the Levant was entirely in Mamluk hands and divided into several provinces. Lajjun became the center of an ''ʿAmal'' (subdistrict) in the ''Mamlaka'' of Safad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevat ...

(ultimately becoming one of sixteen). In the 14th century members of a Yamani tribe lived there. Shams al-Din al-'Uthmani, writing probably in the 1370s, reported it was the seat of Marj ibn Amer, and had a great '' khan'' for travellers, a "terrace of the sultan" and the Maqam (shrine)

A Maqām ( ar, مقام) is a shrine built on the site associated with a religious figure or saint, typical to the regions of Palestine and Syria. It is usually a funeral construction, commonly cubic-shaped and topped with a dome.

Maqams are as ...

of Abraham.'Uthmani, ''Ta'rikh Safad'' sec. X, in a partial reproduction of the Arabic text in Lewis, 1953 p. 483. Cf. a complete edition in Zakkār, 2009. The Mamluks fortified it in the 15th century and the town became a major staging post on the postal route (''braid'') between Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

.

Ottoman era

Early rule and the Tarabay family

TheOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

conquered most of Palestine from the Mamluks after the Battle of Marj Dabiq

The Battle of Marj Dābiq ( ar, مرج دابق, meaning "the meadow of Dābiq"; tr, Mercidabık Muharebesi), a decisive military engagement in Middle Eastern history, was fought on 24 August 1516, near the town of Dabiq, 44 km north of ...

in 1517. As the army of Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

moved south towards Egypt, Tarabay ibn Qaraja, chieftain of the Bani Hareth

The Banu al-Harith ( ar, بَنُو الْحَارِث ' or ar, بَنُو الْحُرَيْث ') is an Arabian tribe which once governed the cities of Najran, Taif, and Bisha, now located in southern Saudi Arabia.

History

Origins and early ...

, a Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

tribe from the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, supported them by contributing guides and scouts.Ze'evi, 1996, p41

When the Mamluks were completely uprooted and Selim returned to

Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, the Tarabays were granted the territory of Lajjun. The town eventually became the capital of the ''Sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian language, Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian language, Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησι� ...

'' ("District") of Lajjun, which was a part of the province of Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, and encompassed the Jezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

, northern Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

, and a part of the north-central coastline of Palestine as its territory.Agmon, 2006, p. 65. It was composed of four ''nahiyas'' ("sub-districts") (Jinin, Sahel Atlit, Sa'ra, and Shafa), and encompassed a total of 55 villages, including Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

, Jenin, and Baysan

Beit She'an ( he, בֵּית שְׁאָן '), also Beth-shean, formerly Beisan ( ar, بيسان ), is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is be ...

.The Cultural Landscape of the Tell Jenin RegionLeiden University Open Access, p.29, p.32. After a short period in which the Tarabays were in a state of rebellion, tensions suddenly died down and the Ottomans appointed Ali ibn Tarabay as the governor of Lajjun in 1559. His son Assaf Tarabay ruled Lajjun from 1571 to 1583. During his reign, he extended Tarabay power and influence to

Sanjak Nablus

The Nablus Sanjak ( ar, سنجق نابلس; tr, Nablus Sancağı) was an administrative area that existed throughout Ottoman rule in the Levant (1517–1917). It was administratively part of the Damascus Eyalet until 1864 when it became part o ...

.Ze'evi, 1996, p42

In 1579, Assaf, referred to as the " Sanjaqbey of al-Lajjun," is mentioned as the builder of a mosque in the nearby village of al-Tira. Assaf was deposed and banished in 1583 to the island of

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

. Six years later, in 1589, he was pardoned and resettled in the town. At the time, an impostor also named Assaf, had attempted to seize control of Sanjak Lajjun. Known later as Assaf al-Kadhab ("Assaf the Liar"), he was arrested and executed in Damascus where he traveled in attempt to confirm his appointment as governor of the district. In 1596, Lajjun was a part of the ''nahiya

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

'' of Sha'ra and paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, as well as goats, beehives and water buffaloes.Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 190. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 521.

Assaf Tarabay was not reinstated as governor, but Lajjun remained in Tarabay hands, under the rule of Governor Tarabay ibn Ali who was succeeded upon his death by his son Ahmad in 1601, who also ruled until his death in 1657. Ahmad, known for his courage and hospitality, helped the Ottomans defeat the rebel Ali Janbulad

Ali Janbulad Pasha (transliterated in Turkish as Canbolatoğlu Ali Paşa; died 1 March 1610) was a Kurds, Kurdish tribal chief from Kilis and a rebel Ottoman Empire, Ottoman governor of Aleppo Eyalet, Aleppo who wielded practical supremacy over ...

and gave shelter to Yusuf Sayfa

Yusuf Sayfa Pasha ( ar, يوسف سيفا باشا, Yūsuf Sayfā Pāsha; – 22 July 1625) was a chieftain and ''multazim'' (tax farmer) in the Tripoli region who frequently served as the Ottoman ''beylerbey'' (provincial governor) of Tripo ...

—Janbulad's principal rival. Ahmad, in coordination with the governors of Gaza (the Ridwan family) and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

(the Farrukh family), also fought against Fakhr ad-Din II

Fakhr al-Din ibn Qurqumaz Ma'n ( ar, فَخْر ٱلدِّين بِن قُرْقُمَاز مَعْن, Fakhr al-Dīn ibn Qurqumaz Maʿn; – March or April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II ( ar, فخر الدين ال ...

in a prolonged series of battles, which ended with the victory of the Tarabay-Ridwan-Farrukh alliance after their forces routed Fakhr ad-Din's army at the al-Auja river

The Yarkon River, also Yarqon River or Jarkon River ( he, נחל הירקון, ''Nahal HaYarkon'', ar, نهر العوجا, ''Nahr al-Auja''), is a river in central Israel. The source of the Yarkon ("Greenish" in Hebrew) is at Tel Afek (Antip ...

in central Palestine in 1623.

The Ottoman authorities of Damascus expanded Ahmad's fief as a token of gratitude. Ahmad's son Zayn Tarabay ruled Lajjun for a brief period until his death in 1660. He was succeeded by Ahmad's brother Muhammad Tarabay, who—according to his French secretary—had good intentions for governing Lajjun, but was addicted to opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

and as a result had been a weak leader. After his death in 1671, other members of the Tarabay family ruled Lajjun until 1677 when the Ottomans replaced them with a government officer. The main reason behind the Ottoman abandonment of the Tarabays was that their larger tribe, the Bani Hareth, migrated east of Lajjun to the eastern banks of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. Later during this century, Sheikh Ziben, ancestor to the Arrabah-based Abd al-Hadi clan, became the leader of Sanjak Lajjun. When Henry Maundrell

Henry Maundrell (1665–1701) was an academic at Oxford University and later a Church of England clergyman, who served from 20 December 1695 as chaplain to the Levant Company in Syria. His ''Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem at Easter A.D. 1697'' ...

visited in 1697, he described the place as "an old village near which was a good ''khan''".

Later Ottoman rule

Much of the Lajjun district territories were actually taxed by the stronger families of Sanjak Nablus by 1723. Later in the 18th century, Lajjun was replaced by Jenin as the administrative capital of the ''sanjak'' which now included the Sanjak of

Much of the Lajjun district territories were actually taxed by the stronger families of Sanjak Nablus by 1723. Later in the 18th century, Lajjun was replaced by Jenin as the administrative capital of the ''sanjak'' which now included the Sanjak of Ajlun

Ajloun ( ar, عجلون, ''‘Ajlūn''), also spelled Ajlun, is the capital town of the Ajloun Governorate, a hilly town in the north of Jordan, located 76 kilometers (around 47 miles) north west of Amman. It is noted for its impressive ruins of t ...

. By the 19th century it was renamed Sanjak Jenin, although Ajlun was separated from it.Doumani, 1995, p39

Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Pale ...

, who became the effective ruler of the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

for a short period during the second half of the 18th century, was reported to have used cannons against Lajjun in the course of his campaign between 1771–1773 to capture Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

. It is possible that this attack led to the village's decline in the years that followed. By that time, Lajjun's influence was diminished by the increasing strength of Acre's political power and Nablus's economic muscle.

Edward Robinson visited in 1838, and noted that the ''khan'', which Maundrell commented on, was for the accommodation of the caravans passing on the great road between Egypt and Damascus which comes from the western plain along the coast, over the hills to Lajjun, and enters the plain of

Edward Robinson visited in 1838, and noted that the ''khan'', which Maundrell commented on, was for the accommodation of the caravans passing on the great road between Egypt and Damascus which comes from the western plain along the coast, over the hills to Lajjun, and enters the plain of Esdraelon

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

. When the British consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

James Finn

James Finn (1806–1872) was a British Consul in Jerusalem, in the then Ottoman Empire (1846–1863). He arrived in 1845 with his wife Elizabeth Anne Finn. Finn was a devout Christian, who belonged to the London Society for Promoting Christia ...

visited the area in the mid-19th century, he did not see a village. The authors of the ''Survey of Western Palestine'' also noticed a ''khan'', south of the ruins of Lajjun in the early 1880s. Gottlieb Schumacher

Gottlieb Schumacher (21 November 1857 – 26 November 1925) was an American-born civil engineer, architect and archaeologist of German descent, who was an important figure in the early archaeological exploration of Palestine.

Early life

Sch ...

saw caravans resting at the Lajjun stream in the early 1900s.Schumacher, 1908, p6

/ref>

Andrew Petersen, inspecting the place in 1993, noted that the principal extant buildings at the site are the ''khan'' and a bridge. The bridge, which crosses a major tributary of the

Andrew Petersen, inspecting the place in 1993, noted that the principal extant buildings at the site are the ''khan'' and a bridge. The bridge, which crosses a major tributary of the Kishon River

The Kishon River ( he, נחל הקישון, ; ar, نهر المقطع, , or , – ''the river of slaughter'' or ''dismemberment''; alternative Arabic, ) is a river in Israel that flows into the Mediterranean Sea near the city of Haifa.

Course ...

, is approximately wide and to long. It is carried on three arches, the north side has been robbed of its outer face, while the south side is heavily overgrown with vegetation. According to Petersen, the bridge was already in ruins when drawn by Charles William Wilson

Lieutenant-General Sir Charles William Wilson, KCB, KCMG, FRS (14 March 1836 – 25 October 1905) was a British Army officer, geographer and archaeologist.

Early life and career

He was born in Liverpool on 14 March 1836. He was educated at ...

in the 1870s. The ''khan'' is located on a low hill to the southwest of the bridge. It is a square enclosure measuring approximately per side with a central courtyard. The ruins are covered with vegetation, and only the remains of one room is visible.

In the late 19th century, Arabs from Umm al-Fahm

Umm al-Fahm ( ar, أمّ الفحم, ''Umm al-Faḥm''; he, אוּם אֶל-פַחֶם ''Um el-Faḥem'') is a city located northwest of Jenin in the Haifa District of Israel. In its population was , nearly all of whom are Arab citizens of I ...

started to make use of the Lajjun farmland, settling for the season.Rami, Sal-Lajjun

Jerusalemites.Khalidi, 1992, p.335 Gradually, they settled in the village, building their houses around the springs. In 1903–1905, Schumacher excavated Tell al-Mutasallim (ancient Megiddo) and some spots in Lajjun. Schumacher wrote that ''Lajjun'' ("el-Leddschōn") is properly the name of the stream and surrounding farmlands, and calls the village along the stream ''Ain es-Sitt''. Which, he noted, "consists of only nine shabby huts in the midst of ruins and heaps of dung." and a few more

fellah

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

in huts south of the stream. By 1925 some of the inhabitants of Lajjun reused stones from the ancient structure that had been unearthed to build new housing. At some point in the early 20th century the four '' hamulas'' ("clans") of Umm al-Fahm divided the land among themselves: al-Mahajina, al-Ghubariyya, al-Jabbarin and al-Mahamid clans.Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:44-45

British Mandate period

More people moved to Lajjun during the British mandate period, particularly in the late thirties, due to the British crackdown on participants in the1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

. The tomb of Yusuf Hamdan, a local leader of the revolt, is located in the village. Others moved in as they came to understand that the Mandate authorities planned to turn Lajjun into a county seat. During 1940–1941, a police station belonging to the Tegart fort

A Tegart fort is a type of militarized police fort constructed throughout Palestine during the British Mandatory period, initiated as a measure against the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt.

Etymology

The forts are named after their designer, British p ...

s system was constructed at the road intersection outside Lajjun by the British Mandate government.

Lajjun's economy grew rapidly as a result of the influx of the additional population.Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:7-9. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335 As the village expanded, it was divided into three quarters, one to the east, one to the west, and the older one in the north. Each quarter was inhabited by one or more ''hamula'' ("clan").Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:44. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 335

Lajjun had a school that was founded in 1937 and that had an enrollment of 83 in 1944. It was located in the quarter belonging to the al-Mahajina al-Fawqa clan, that is, in Khirbat al-Khan. In 1943, one of the large landowners in the village financed the construction of a mosque, built of white stone, in the al-Ghubariyya (eastern) quarter. Another mosque was also established in the al-Mahamid quarter during the same period, and was financed by the residents themselves. It was a four-year elementary school for boys.

In

Lajjun had a school that was founded in 1937 and that had an enrollment of 83 in 1944. It was located in the quarter belonging to the al-Mahajina al-Fawqa clan, that is, in Khirbat al-Khan. In 1943, one of the large landowners in the village financed the construction of a mosque, built of white stone, in the al-Ghubariyya (eastern) quarter. Another mosque was also established in the al-Mahamid quarter during the same period, and was financed by the residents themselves. It was a four-year elementary school for boys.

In 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. It is also the only year in which nuclear weapons have been used in combat.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

Januar ...

, Lajjun, Umm al-Fahm and seven hamlets had a total land area of , of which was Arab-owned, and the remainder being public property.Department of Statistics, 1945, p17

/ref>Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970

p.55

The seven hamlets were

Aqqada

Umm al-Fahm ( ar, أمّ الفحم, ''Umm al-Faḥm''; he, אוּם אֶל-פַחֶם ''Um el-Faḥem'') is a city located northwest of Jenin in the Haifa District of Israel. In its population was , nearly all of whom are Arab citizens of Isr ...

, Ein Ibrahim

Umm al-Fahm ( ar, أمّ الفحم, ''Umm al-Faḥm''; he, אוּם אֶל-פַחֶם ''Um el-Faḥem'') is a city located northwest of Jenin in the Haifa District of Israel. In its population was , nearly all of whom are Arab citizens of I ...

, Khirbet al-Buweishat, Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, Musheirifa

Al-Musheirifa ( ar, المشيرفة, he, מושיריפה or ) is an Arab village in Israel's Haifa District. The village is located in the Wadi Ara area of the northern Triangle, northeast of Umm al-Fahm. Since 1996, it has been under the juri ...

, al-Murtafi'a

Zalafa ( ar, زلفة, he, זלפה) is an Arab village in Israel's Haifa District. The village is in the Wadi Ara area of the northern Triangle, northeast of Umm al-Fahm. Since 1996, it has been under the jurisdiction of the Ma'ale Iron local ...

, and Musmus

Musmus ( ar, مُصمُص, he, מוצמוץ / ) is an Arab village in Haifa District. The village is located in the Wadi Ara area of the northern Triangle, northeast of Umm al-Fahm. Since 1996, it has been under the jurisdiction of the Ma'ale Iro ...

. There was a total of of land that was cultivated; were used for plantations and irrigated, and were planted with cereals (wheat and barley). The built-up area of the villages was , most of it being in Umm al-Fahm and Lajjun. Former villagers recall they grew wheat and corn in the fields, and irrigated crops such as eggplant, tomato, okra, cowpea and watermelon. A survey map from 1946 shows most of the buildings in the eastern and western quarters as built from stone and mud, but some used mud over wood. Many houses had neighbouring small plots marked as "orchards".

There was a small market place in the village, as well as six grain mills (powered by the numerous springs and wadis in the vicinity), and a health center. The various quarters of Lajjun had many shops. A bus company was established in Lajjun by a villager from Umm al-Fahm; the bus line served Umm al-Fahm, Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

, and a number of villages, such as Zir'in

Zir'in ( ar, زرعين, also spelled ''Zerein'') was a Palestinian Arab village of over 1,400 in the Jezreel Valley, located north of Jenin. Identified as the ancient town of Yizre'el (Jezreel), it was known as Zir'in during Islamic rule, and ...

. In 1937, the line had seven buses. Subsequently, the company was licensed to serve Jenin also, and acquired the name of "al-Lajjun Bus Company".

1948 War

Lajjun was allotted to the Arab state in the 1947 proposedUnited Nations Partition Plan

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

. The village was defended by the Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in th ...

(ALA), and was the logistical headquarters of the Iraqi army. It was first assaulted by the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

on April 13, during the battle around kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

Mishmar HaEmek

Mishmar HaEmek ( he, מִשְׁמַר הָעֵמֶק, . "Guard of the Valley") is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located in the western Jezreel Valley, it falls under the jurisdiction of the Megiddo Regional Council. Mishmar HaEmek is one of ...

. ALA commander Fawzi al-Qawuqji claimed Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

ish forces ("Haganah") had attempted to reach the crossroads at Lajjun in an outflanking operation, but the attack failed. The ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reported that twelve Arabs were killed and fifteen wounded during that Haganah offensive. Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Companies") was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of the British Mandate for Palestine. The Palmach ...

units of the Haganah raided and blew up much of Lajjun on the night of April 15–16.

On April 17, it was occupied by the Haganah. According to the newspaper, Lajjun was the "most important place taken by the Jews, whose offensive has carried them through ten villages south and east of Mishmar Ha'emek." The report added that women and children had been removed from the village and that 27 buildings in the village were blown up by the Haganah. However, al-Qawuqji states that attacks resumed on May 6, when ALA positions in the area of Lajjun were attacked by Haganah forces. The ALA's Yarmouk Battalion and other ALA units drove back their forces, but two days later, the ALA commander reported that the Haganah was "trying to cut off the Lajjun area from Tulkarm

Tulkarm, Tulkarem or Tull Keram ( ar, طولكرم, ''Ṭūlkarm'') is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located in the Tulkarm Governorate of the State of Palestine. The Israeli city of Netanya is to the west, and the Palestinian cities of N ...

in preparation of seizing Lajjun and Jenin..."

State of Israel

On May 30, 1948, in the first stage of the1948 Arab-Israeli War

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

, Lajjun was captured by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

's Golani Brigade

The 1st "Golani" Brigade ( he, חֲטִיבַת גּוֹלָנִי) is an Israeli military infantry brigade that is subordinated to the 36th Division and traditionally associated with the Northern Command. It is one of the five infantry brigade ...

in Operation Gideon

Operation Gideon was a Haganah offensive launched in the closing days of the British Mandate in Palestine, as part of the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine. Its objectives were to capture Beisan (Beit She'an), clear the surrounding vil ...

. The capture was particularly important for the Israelis because of its strategic location at the entrance of the Wadi Ara

Wadi Ara ( ar, وادي عارة, he, ואדי עארה) or Nahal 'Iron ( he, נחל עירון), is a valley and its surrounding area in Israel populated mainly by Arab Israelis. The area is also known as the "Northern Triangle".

Wadi Ara is ...

, which thus, brought their forces closer to Jenin. During the second truce between Israel and the Arab coalition, in early September, a United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

official fixed the permanent truce line in the area of Lajjun, according to press reports. A 500-yard strip was established on both sides of the line in which Arabs and Jews were allowed to harvest their crops. Lajjun was used as transit place by the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

to transfer 1,400 Arab women, children and elderly from Ijzim, who then were sent on foot to Jenin.

Kibbutz Megiddo was built on some of Lajjun's village lands starting in 1949. Lajjun's buildings were demolished in the following months.

In November 1953, of the lands of Umm al-Fahm were confiscated by the state, invoking the Land Acquisition (Validation of Acts and Compensation) Law, 5713-1953. These included much of the built-up area of Lajjun (at Block 20420, covering ).See GIS map by the Survey of Israel

Survey of Israel - SOI (Hebrew: מפ"י - המרכז למיפוי ישראל) is the survey and mapping department of the Israeli Housing and Construction Minister of Israel, Ministry of Housing and Construction. It is the successor of the Survey ...

It was later afforestation, planted with forest trees. In 1992

Walid Khalidi

Walid Khalidi ( ar, وليد خالدي, born 1925 in Jerusalem) is an Oxford University-educated Palestinian people, Palestinian historian who has written extensively on the 1948 Palestinian exodus, Palestinian exodus. He is a co-founder of the ...

described the remains: "Only the white stone mosque, one village mill, the village health center, and a few partially destroyed houses remain on the site. The mosque has been converted into a carpentry workshop and one of the houses has been made into a chicken coop. The health center and grain mill are deserted, and the school is gone. The cemetery remains, but it is in a neglected state; the tomb of Yusuf al-Hamdan, a prominent nationalist who fell in the 1936 revolt, is clearly visible. The surrounding lands are planted with almond trees, wheat, and barley; they also contain animal sheds, a fodder plant, and a pump installed on the spring of 'Ayn al-Hajja. The site is tightly fenced in and entry is blocked."Khalidi, 1992, pp. 336-337 In 2000 Meron Benvenisti

Meron Benvenisti ( he, מירון בנבנשתי, 21 April 193420 September 2020) was an Israeli political scientist who was deputy mayor of Jerusalem under Teddy Kollek from 1971 to 1978, during which he administered East Jerusalem and served as ...

restated the information about the 1943 white mosque.Benvenisti, 2000, p. 319

/ref> By 2007 it was evacuated and sealed up. In the 2000s, 486 families from Umm al-Fahm (formerly from Lajjun), through Adalah, motioned to nullify the confiscation of that particular block. The district court ruled against the plaintiffs in 2007, and the supreme court held the decision in 2010.

Demographics

During early Ottoman rule, in 1596, Lajjun had a population of 226 people. In the British Mandate census in 1922, there were 417 inhabitants.Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Jenin, p30

/ref> In the

1931 census of Palestine

The 1931 census of Palestine was the second census carried out by the authorities of the British Mandate for Palestine. It was carried out on 18 November 1931 under the direction of Major E. Mills after the 1922 census of Palestine.

* Census of P ...

, the population had more than doubled to 857, of which 829 were Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s, 26 were Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

s, as well as two Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s.Mills, 1932, p69

/ref> In that year, there were 162 houses in the village.

Palestine Remembered. At the end of 1940, Lajjun had 1,103 inhabitants. The prominent families of al-Lajjun were the Jabbarin, Ghubayriyya, Mahamid and the Mahajina. Around 80% of its inhabitants fled to Umm al-Fahm, where they currently live as

Arab citizens of Israel

The Arab citizens of Israel are the largest ethnic minority in the country. They comprise a hybrid community of Israeli citizens with a heritage of Palestinian citizenship, mixed religions (Muslim, Christian or Druze), bilingual in Arabic an ...

and internally displaced Palestinians

Present absentees are Arab internally displaced persons (IDPs) who fled or were expelled from their homes in Mandatory Palestine during the 1947–1949 Palestine war but remained within the area that became the state of Israel. The term applies ...

.

Culture

Local tradition centered on 'Ayn al-Hajja, the spring of Lajjun, date back to the 10th century CE when the village was under Islamic rule. According to geographers of that century, as well as the 12th century, the legend was that under the Mosque of Abraham, a "copious stream flowed" which formed immediately after theprophet Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

struck the stone with his staff. Abraham had entered the town with his flock of sheep on his way towards Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, and the people of the village informed him that the village possessed only small quantities of water, thus Abraham should pass on the village to another. According to the legend, Abraham was commanded to strike the rock, resulting in water "bursting out copiously". From then, the village orchards and crops were well-irrigated and the people satisfied with a surplus of drinking water from the spring.

In Lajjun there are tombs for two Mamluk-era Muslim relics who were from the village. The holy men were Ali Shafi'i who died in 1310 and Ali ibn Jalal who died in 1400.

Archaeology

In 2001, archaeological excavations were conducted by theIsrael Antiquities Authority

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA, he, רשות העתיקות ; ar, داﺌرة الآثار, before 1990, the Israel Department of Antiquities) is an independent Israeli governmental authority responsible for enforcing the 1978 Law of ...

(IAA) at sites of Kefar ‘Otnay and Legio west of Megiddo Junction. The results revealed artifacts dating back to the Roman and early Byzantine periods. In 2004, further excavations were conducted by the IAA at Legio.Israel Antiquities Authority

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA, he, רשות העתיקות ; ar, داﺌرة الآثار, before 1990, the Israel Department of Antiquities) is an independent Israeli governmental authority responsible for enforcing the 1978 Law of ...

Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2004

Survey Permit # A-4227

See also

*History of Palestine

The history of Palestine is the study of the past in the region of Palestine, also known as the Land of Israel and the Holy Land, defined as the territory between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River (where Israel and Palestine are tod ...

* Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

*List of villages depopulated during the Arab-Israeli conflict

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

*Megiddo church

The Megiddo Mission or Megiddo Church is a small American Restorationist denomination founded by L. T. Nichols in 1880 in Rochester, New York. The church's magazine is the ''Megiddo Message.''

Lemuel T. Nichols was born on October 1, 1844, Goshen, ...

, possibly dating to the 3rd century and located at ancient Legio

References

Bibliography

* * * * ncludes the recollections of six former villagers. * * * * * Fisher, C.S., 1929,The Excavation of Armageddon

'' Oriental Institute Communications 4, University of Chicago Press * * * *Heyd, Uriel (1960): ''Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552-1615'', Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cited in Petersen (2002) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * al-Qawuqji, F. (1972)

Memoirs of al-Qawuqji, Fauzi

in ''

Journal of Palestine Studies

The ''Journal of Palestine Studies (JPS)'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal established in 1971. It is published by Taylor and Francis on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies, having previously been published by the University ...

''

"Memoirs, 1948, Part I" in 1, no. 4 (Sum. 72): 27-58.

pdf-file, downloadable

"Memoirs, 1948, Part II" in 2, no. 1 (Aut. 72): 3-33.

pdf-file, downloadable * * * * The edition follows the same pagination the German publication at . *State of Israel, "Hydrographic list of the map of Israel",

Government Naming Committee

Government Naming Committee ( he, ועדת השמות הממשלתית, sometimes referred as National Naming Committee or Government Names Committee) is a public committee appointed by the Government of Israel, which deals with the designation ...

decisions, in ReshumotExternal links

Welcome To al-Lajjun

palestineremembered.com

Lajjun

from

Zochrot

Zochrot ( he, זוכרות; "Remembering"; ar, ذاكرات; "Memories") is an Israeli nonprofit organization founded in 2002. Based in Tel Aviv, its aim is to promote awareness of the Palestinian ''Nakba'' ("Catastrophe"), including the 1948 Pa ...

*Survey of Western Palestine, Map 8Wikimedia commons

Al-Lajjon

from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

from the