Lycée Louis-le-Grand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand (), also referred to simply as Louis-le-Grand or by its acronym LLG, is a public Lycée (French secondary school, also known as

Jesuit students, mostly from Spain and Italy, were present in Paris immediately after the

Jesuit students, mostly from Spain and Italy, were present in Paris immediately after the

With the

With the

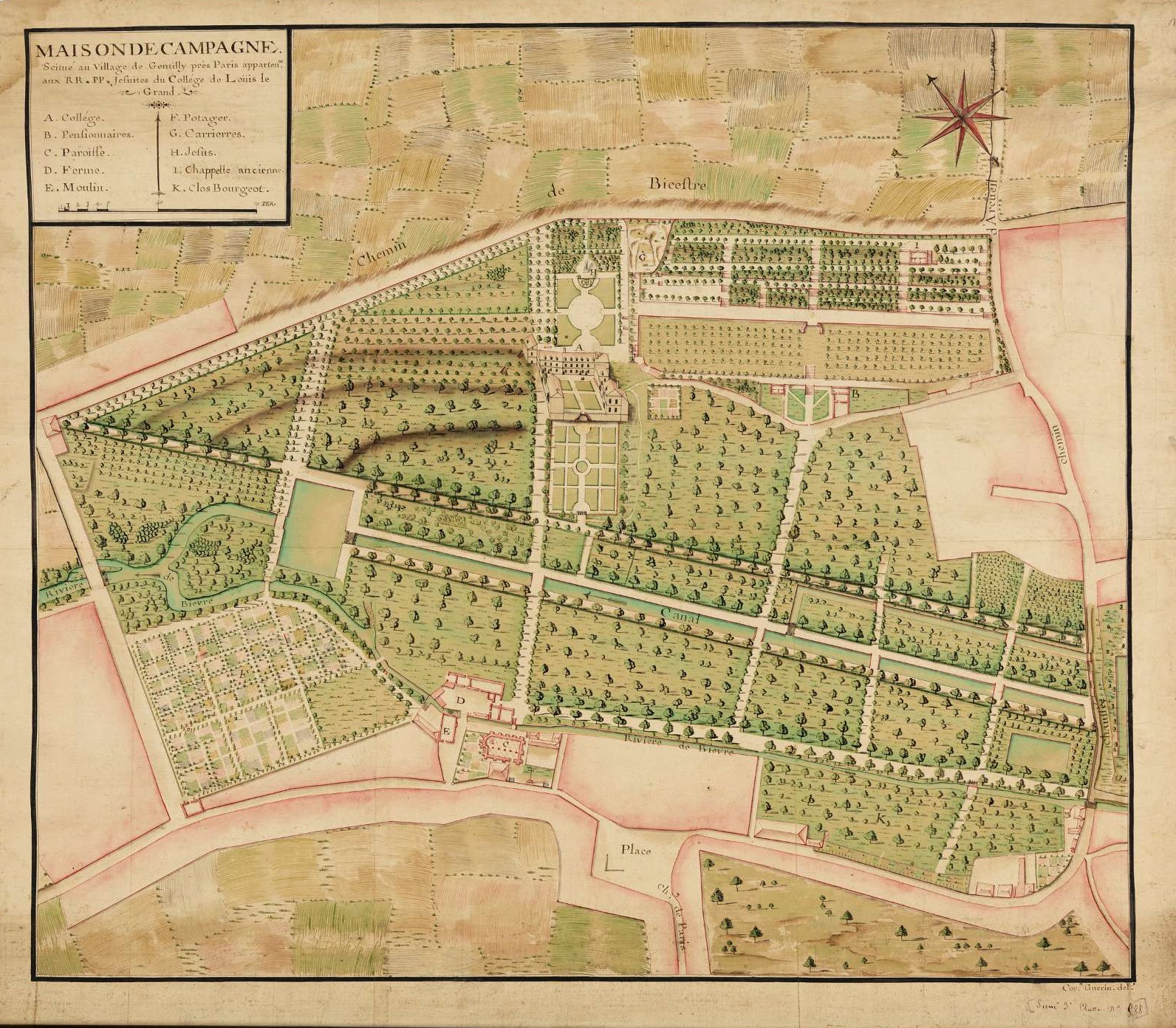

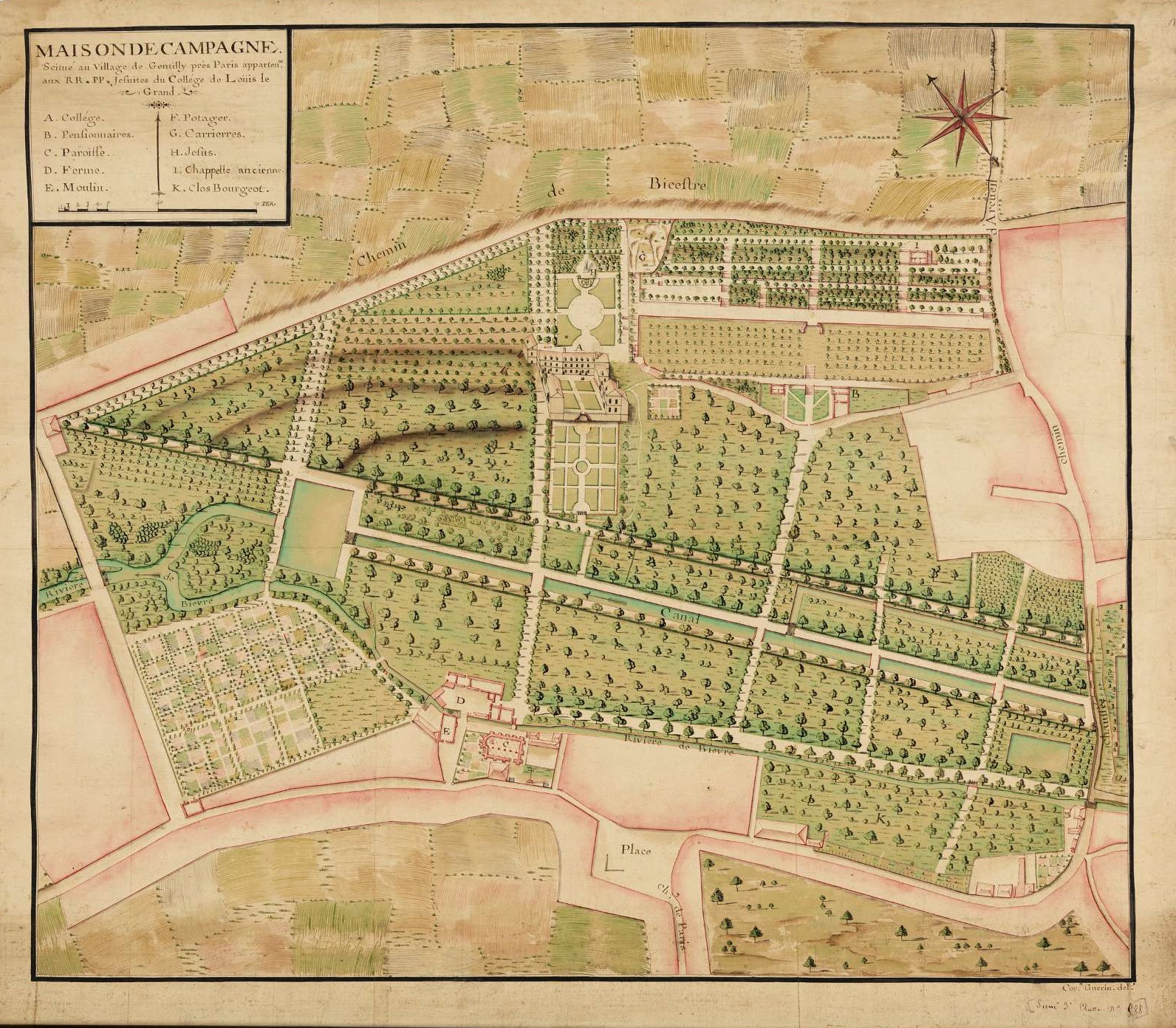

The made a series of purchases in Gentilly to establish a rural retreat there, in 1632, 1638, 1640 and 1659, thus forming a major property that was eventually sold after the order's suppression in the early 1770s. One of its buildings survives and has been repurposed in the 1990s as the

The made a series of purchases in Gentilly to establish a rural retreat there, in 1632, 1638, 1640 and 1659, thus forming a major property that was eventually sold after the order's suppression in the early 1770s. One of its buildings survives and has been repurposed in the 1990s as the

In 1882, a law awarded a former tree nursery ground of the

In 1882, a law awarded a former tree nursery ground of the

File:Lycee Louis-le-Grand.jpg, Front side on rue Saint-Jacques

File:Llgcourvictorhugo.jpg, ''Cour Victor Hugo''

File:Victor Hugo courtyard, Lycée Louis-le-Grand (24-04-2007).jpg, ''Cour Victor Hugo''

File:molierellg1.jpg, ''Cour Molière''

File:Louis-le-Grand--cour-honneur.jpg, ''Cour d'Honneur''

Lycée Louis-le-Grand

(official website)

Homepage of the parents' association FCPE

Homepage of the parents' association PEEP

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lycee Louis le Grand 1563 establishments in France Buildings and structures in the 5th arrondissement of Paris Jesuit secondary schools in France Jesuit universities and colleges Educational institutions established in the 1560s

sixth form college

A sixth form college is an educational institution, where students aged 16 to 19 typically study for advanced school-level qualifications, such as A Levels, Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) and the International Baccalaureate ...

) located on rue Saint-Jacques in central Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

. It was founded in the early 1560s by the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

as the ''Collège de Clermont'', was renamed in 1682 after King Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

("Louis the Great"), and has remained at the apex of France's secondary education system despite its disruption in 1762 following the suppression of the Society of Jesus

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the Society of Jesus from most of the countries of Western Europe and their colonies beginning in 1759, and the abolishment of the order by the Holy See in 1773. The Jesuits were ...

. It offers both a high school curriculum, and a Classes Préparatoires

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

post-secondary-level curriculum in the sciences, business and humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

.

The strict admission process is based on academic grades, drawing from middle schools (for entry into high school) and high schools (for entry into the preparatory classes) throughout France. Its educational standards are highly rated and the working conditions are considered optimal due to its demanding recruitment of teachers. Louis-Le-Grand's students, occasionally referred to as ''magnoludoviciens'', regularly top national rankings for baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

grades (high school) and entry into the grandes écoles Grandes may refer to:

* Agustín Muñoz Grandes, Spanish general and politician

* Banksia ser. Grandes, a series of plant species native to Australia

* Grandes y San Martín, a municipality located in the province of Ávila, Castile and León, Spa ...

(preparatory classes).

Location

Louis-le-Grand is located in the heart of theQuartier Latin

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistro ...

, the centuries-old student district of Paris. It is surrounded by other storied educational institutions: the Sorbonne to its west, across rue Saint-Jacques; the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris ...

to its north, across ; the Panthéon campus of Paris 2 Panthéon-Assas University

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Sin ...

to its south, across rue Cujas; the former Collège Sainte-Barbe to its east, across ; and the Sainte-Geneviève Library

Sainte-Geneviève Library (french: link=no, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève) is a public and university library located at 10, place du Panthéon, across the square from the Panthéon, in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. It is based on the ...

to its southeast.

History

Jesuit college (1560-1762)

Jesuit students, mostly from Spain and Italy, were present in Paris immediately after the

Jesuit students, mostly from Spain and Italy, were present in Paris immediately after the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

's foundation, first in 1540 at the and from 1541 at the . From 1550 on, Guillaume Duprat, the bishop of Clermont

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Clermont (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Claromontana''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Clermont'') is an archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The diocese comprises the department of Puy-d ...

, who in the previous decade had met early Jesuit leaders and Diego Laynez and corresponded with Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola, S.J. (born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; eu, Ignazio Loiolakoa; es, Ignacio de Loyola; la, Ignatius de Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Spanish Catholic priest and theologian, ...

, invited Jesuit students to stay in his mansion, the on rue de la Harpe. The thus became the Jesuit order's first permanent home in Paris. It no longer exists following its annexation in the 17th century by the nearby , and stood on a location that is now part of the Lycée Saint-Louis

The lycée Saint-Louis is a highly selective post-secondary school located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, in the Latin Quarter. It is the only public French lycée exclusively dedicated to providing '' classes préparatoires aux grandes ...

.

Upon his death on , Duprat bequested an endowment for a new Jesuit college in Paris, as well as funds for two other colleges in the vicinity of Clermont, at Billom at Mauriac. The Parisian project was eagerly supported by Laynez, by then the Jesuits' Superior General

A superior general or general superior is the leader or head of a religious institute in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized ...

, who wanted it to become "the most celebrated college of the Society". It was delayed, however, by dilatory initiatives by the Parliament of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

, University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

, and local clergy, all of which opposed the Jesuits' establishment. In July 1563, the Jesuits were finally able to purchase the former Parisian estate of the bishop of Langres

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Langres (Latin: ''Dioecesis Lingonensis''; French: ''Diocèse de Langres'') is a Roman Catholic diocese comprising the ''département'' of Haute-Marne in France.

The diocese is now a suffragan in ecclesiastical p ...

on rue Saint-Jacques, where its current now stands, and started teaching there in late 1563 (Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

). The new institution was named , in recognition of Duprat's support but also because one of the conditions that the Jesuits accepted to overcome local opposition was not to formally name the college after the Society of Jesus as they did elsewhere.

The college soon met considerable success, as it was both free and of high quality, disrupting the antiquated business models and longstanding conventions of the University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

. In particular, its theology course, led from the 1564 inception by Juan Maldonado, was so popular that the college's buildings were too small to contain the audience. Other prominent early faculty included Pierre Perpinien, Juan de Mariana, and Francisco Suárez

Francisco Suárez, (5 January 1548 – 25 September 1617) was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas ...

.

The University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

had been hostile to the Jesuits from the start, in line with its general rejection of novel initiatives and long before that hostility took doctrinal undertones in the 17th and 18th centuries as the Jesuits became a key adversary for Jansenists

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by th ...

. In 1554, the University's College of Sorbonne

The College of Sorbonne (french: Collège de Sorbonne) was a theological college of the University of Paris, founded in 1253 (confirmed in 1257) by Robert de Sorbon (1201–1274), after whom it was named.

With the rest of the Paris colleges, ...

had already issued a negative opinion regarding the opening of a college in Paris. That opposition was temporarily overcome at the monarchy's initiative during the Colloquy of Poissy

The Colloquy at Poissy was a religious conference which took place in Poissy, France, in 1561. Its object was to effect a reconciliation between the Catholics and Protestants ( Huguenots) of France.

The conference was opened on 9 September in the ...

on , but the University kept debating the matter after the college started teaching in 1564. On , it refused to recognize it and thereby nullified the prior favorable decision of Poissy. The multiple cases brought by the University before the court of the Parliament of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

, and counter-cases from the Jesuits, resulted in a stalemate that lasted over the next three decades: the was not readmitted into the University system, but the Jesuits were able to continue and expand their activities, even though Maldonado was removed from Paris in 1575 following accusations of heresy by Sorbonne theologians. While the courses were free of charge, boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

** Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where ho ...

costs for the resident students, who typically came from elite families, were covered by gifts and scholarships, and the corresponding accounts were kept separate until the Jesuits' departure in 1762. In the 1580s, the college's students numbered in the thousands, of which several hundreds were resident ( and ). The faculty included several dozen Jesuit priests.

Unlike most colleges of the University, the Jesuit college remained open during the Siege of Paris in 1590, albeit with reduced activity, and inevitably colluded with the Catholic League, as did the University too. On , an alumnus of the college, Jean Châtel Jean Châtel (1575 – 29 December 1594) attempted to assassinate King Henry IV of France on 27 December 1594. He was the son of a cloth merchant and was aged 19 when executed on 29 December.

On 27 December 1594, Châtel managed to gain entry t ...

, attempted to assassinate King Henry IV. As a reaction, the king took the side of the Jesuits' longstanding accusers such as Parlement lawyer Antoine Arnauld

Antoine Arnauld (6 February 16128 August 1694) was a French Catholic theologian, philosopher and mathematician. He was one of the leading intellectuals of the Jansenist group of Port-Royal and had a very thorough knowledge of patristics. Cont ...

, and expelled the Jesuits from France, including those in Paris. In 1595, the bibliothèque du roi was relocated into the college's premises and stayed there until 1603. That year, Henry allowed the Jesuits to return to France on the conditions that they be French nationals. They were allowed to retake the college building in 1606, and to fully restart their teaching in 1610. On , however, upon a new case brought by the University and in the changed political context resulting from Henry IV's assassination in May 1610 by François Ravaillac

François Ravaillac (; 1578 – 27 May 1610) was a French Catholic zealot who assassinated King Henry IV of France in 1610.

Biography Early life and education

Ravaillac was born in 1578 at Angoulême of an educated family: his grandfather F ...

, the Parliament of Paris

The Parliament of Paris (french: Parlement de Paris) was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. It was fixed in Paris by Philip IV of France in 1302. The Parliament of Paris would hold sessions inside the ...

forbade the Jesuits from teaching in Paris. That ruling, however, was reversed by a decision of Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

on , allowing the Jesuits to resume teaching for good.

Despite its near-continuous interruption between 1595 and 1618, the College de Clermont almost immediately recovered and reached an equivalent level of activity to its heyday of the 1570s and 1580s. Its adversaries made sure that it would still not obtain admission into the University, but otherwise their attempts to undermine it met with decreasing success, given the continuing support the Jesuits were able to secure from the monarchy and high nobility. The college was regularly bolstered by royal visits, including by Louis XIII in 1625 and Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

in 1674. On the latter occasion, the king donated a painting by Jean Jouvenet

Jean-Baptiste Jouvenet (1 May 1644 – 5 April 1717) was a French painter, especially of religious subjects.

Biography

He was born into an artistic family in Rouen. His first training in art was from his father, Laurent Jouvenet; a generation earl ...

, ''Alexander and the family of Darius'', which remains to this day in the office of Louis-le-Grand's principal.

Several notable scholars were resident in the college, including mathematician Pierre Bourdin (1595-1653), historian Philippe Labbe (1607-1667), or latinist Charles de la Rue

Charles de La Rue (3 August 1643, in Paris – 27 May 1725, in Paris), known in Latin as Carolus Ruaeus, was one of the great orators of the Society of Jesus in France in the seventeenth century.

He entered the novitiate on 7 September 1659, and ...

(1643-1725). Other faculty included author René Rapin (1621-1687), scientist Ignace-Gaston Pardies

Ignace-Gaston Pardies (5 September 1636 – 21 April 1673) was a French Catholic priest and scientist.

Career

Pardies was born in Pau, the son of an advisor at the local assembly. He entered the Society of Jesus on 17 November 1652 and for a ...

(1636-1673), historian Claude Buffier (1661-1737), theologian René-Joseph de Tournemine

René-Joseph de Tournemine (; 26 April 1661, Rennes – 16 May 1739) was a French Jesuit theologian and philosopher. He founded the ''Mémoires de Trévoux'', the Jesuit learned journal published from 1701 to 1767, and assailed Nicolas Malebranche ...

(1661-1739), sinologist Jean-Baptiste Du Halde (1674-1743), rhetorician Charles Porée (1675-1741), and humanist Pierre Brumoy

Pierre Brumoy (26 August 1688, in Rouen – 16 April 1742, in Paris) was an 18th-century French Jesuit, humanist and editor of the ''Journal de Trévoux''.

Father Brumoy professed in colleges of his order. He provided articles to the ''Journal of ...

(1688-1742). Composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (; 1643 – 24 February 1704) was a French Baroque composer during the reign of Louis XIV. One of his most famous works is the main theme from the prelude of his ''Te Deum'', ''Marche en rondeau''. This theme is still u ...

, who may have studied at the college, was its music master

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect o ...

() between 1688 and 1698. The college library had about 40,000 volumes as of 1718, and included unique manuscripts such as the Chronicle of Fredegar

The ''Chronicle of Fredegar'' is the conventional title used for a 7th-century Frankish chronicle that was probably written in Burgundy. The author is unknown and the attribution to Fredegar dates only from the 16th century.

The chronicle begin ...

(occasionally known for that reason as ) or ''Anonymus Valesianus ''Anonymus Valesianus'' (or ''Excerpta Valesiana'') is the conventional title of a compilation of two fragmentary vulgar Latin chronicles, named for its modern editor, Henricus Valesius, who published the texts for the first time in 1636, together ...

''. As in other Jesuit colleges, theatrical representations became increasingly prominent during the 17th century. Also as in other colleges, in 1660 the Jesuits opened an observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. H ...

, and in 1679 they created the elaborate sundial

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a fl ...

s, augmented in the 18th century, that survive to this day on the northern side of the thanks to preservation campaigns in 1842 and 1988.

The college undertook a rebuilding campaign in 1628, on a design attributed to Paris municipal architect Augustin Guillain. It expanded by acquiring more buildings, to its northeast from the recently-closed in 1641, and to its south from the in 1656 and 1660. In 1682, the college was able to expand further by acquiring the buildings of the to its east, after a century of attempts, as that college's activities were relocated elsewhere in Paris.

Also in 1682, Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

formally authorized the college to change its name to (french: Collège Louis-le-Grand). That act confirmed its royal patronage, despite the near-simultaneous Declaration of the Clergy of France and the kingdom's ongoing conflicts with the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, to which the Jesuits were directly tied by their vows. Already in 1674, during his visit, Louis was said to have remarked ("this is my college"). A black marble slab with the inscription COLLEGIVM LVDOVICI MAGNI (College of Louis the Great) was promptly placed on the façade, in substitution to the earlier text COLLEGIVM CLAROMONTANVM SOCIETATIS IESV, which triggered controversy. (The anecdote was narrated by Gérard de Nerval

Gérard de Nerval (; 22 May 1808 – 26 January 1855) was the pen name of the French writer, poet, and translator Gérard Labrunie, a major figure of French romanticism, best known for his novellas and poems, especially the collection '' Les F ...

in his short story , published in 1852 in the collection titled .) The new inscription survived later turmoil, and was relocated on the eastern side of the during the late-19th-century rebuilding.

In 1700, Louis-le-Grand took over the École des Jeunes de langues The École des Jeunes de langues was a language school founded by Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1669 to train interpreters and translators (then called dragomans after the Ottoman and Arabic word for such a figure, like Covielle in ''Le Bourgeois genti ...

, founded in 1669 by Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the countr ...

, in line with the Jesuits' leadership in studying foreign languages and foreign cultures, reinforced since 1685 with the permanent mission in China initiated by six Jesuits from Louis-le-Grand. Antoine Galland

Antoine Galland (; 4 April 1646 – 17 February 1715) was a French orientalist and archaeologist, most famous as the first European translator of ''One Thousand and One Nights'', which he called '' Les mille et une nuits''. His version of the ta ...

, the first Western European translator of ''One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'', had studied in this section and taught Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

there from 1709. In 1742 the college had five Chinese students: Paul Liu, Maur Cao, Thomas Liu, Philippe-Stanislas Kang, and Ignace-Xavier Lan, who had come from China via Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

together with Jesuit Father Foureau.

After 1762

With the

With the Suppression of the Society of Jesus

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the Society of Jesus from most of the countries of Western Europe and their colonies beginning in 1759, and the abolishment of the order by the Holy See in 1773. The Jesuits were ...

in France, the Jesuits were ordered to cease their teaching and leave the college on . The establishment was immediately nationalized and renamed . Teachers from the nearby replaced the Jesuit fathers as faculty. This change triggered a broader reform of the University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

. The scholarship students (french: boursiers) of twenty-six smaller colleges of the University of Paris, known as the , were invited to follow classes at Louis-le-Grand. By 1764, these students also boarded at Louis-le-Grand. By then, the effectively ceased autonomous activity, after which their property were gradually sold. Louis-le-Grand thus became the center of the university, even though ten other survived until 1792. The nearby buildings of the , one of the , were purchased by the monarchy in 1770 and repurposed as headquarters (french: chef-lieu) of the University of Paris. Meanwhile, by 1764 the former faculty of the Collège de Beauvais took over teaching at Louis-le-Grand from those of the . Between then and the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, there were about 190 every year at Louis-le-Grand, and a smaller number of whose families paid for their boarding.

As a broader consequence of the Jesuits' termination, the French state in 1766 initiated the examination to raise the standards of teaching in secondary education. Louis-le-Grand aspired to a leading position in supplying future . Its ambitions failed to materialize, however, as only nine of its succeeded in the exams between 1766 and 1792, out of a total of 206 successful candidates during that period.

During and after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, the college was renamed several times in response to France's changing politics: in January 1793, in 1797, in July 1798, in 1803, in 1805, in 1814, in 1815, in 1831, in 1848, in 1849, in 1853, again in 1870, and finally again in 1873. It has kept that name ever since.

Throughout the troubled 1790s, it was the only Parisian educational institution that remained continuously open, as it had been during the 1590s siege of Paris. Part of its premises, however, were used as barracks for soldiers, then as political prison and workshops. In 1796, three more opened in Paris, respectively in the former Abbey of Saint Genevieve

The Abbey of Saint Genevieve (French: ''Abbaye Sainte-Geneviève'') was a monastery in Paris. Reportedly built by Clovis, King of the Franks in 502, it became a centre of religious scholarship in the Middle Ages. It was suppressed at the time of t ...

(, later Lycée Henri-IV), the Professed House of the Jesuits (, later Lycée Charlemagne

The Lycée Charlemagne is located in the Marais quarter of the 4th arrondissement of Paris, the capital city of France.

Constructed many centuries before it became a lycée, the building originally served as the home of the Order of the Jesu ...

), and the Collège des Quatre-Nations

The Collège des Quatre-Nations ("College of the Four Nations"), also known as the Collège Mazarin after its founder, was one of the colleges of the historic University of Paris. It was founded through a bequest by the Cardinal Mazarin. At his d ...

(). The latter building, however, was repurposed in 1801 for artistic training, and its secondary school was relocated to the adjacent to Louis-le-Grand then known as the Prytanée (), then merged into it in 1804. In 1803, Napoleon created the Lycée Condorcet in the former , and in 1820, another new took the premises of the former , now the Lycée Saint-Louis

The lycée Saint-Louis is a highly selective post-secondary school located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, in the Latin Quarter. It is the only public French lycée exclusively dedicated to providing '' classes préparatoires aux grandes ...

. Louis-le-Grand was thus one of only five public in Paris for most of the 19th century, until Jules Ferry's reforms greatly expanded secondary education in the 1880s.

Bordering Louis-le-Grand to the north, some of the buildings of the former were partly used by the École normale from 1810 to 1814 and again from 1826 to 1847, after which it moved to its present campus designed by architect Alphonse de Gisors

Alphonse-Henri Guy de Gisors (3 September 1796 – 18 August 1866) was a 19th-century French architect, a member of the Gisors family of architects and prominent government administrators responsible for the construction and preservation of many ...

on . Others parts of the Plessis complex were temporarily awarded to the Paris University's Faculty of Letters and a section of the Faculty of Law, but were demolished in 1833 as they had become derelict. During the early Second Republic, an opened in July 1848 on the École Normale's former location, promoted by politician Hippolyte Carnot, but it met overwhelming opposition and ceased operating after about six months. Louis-le-Grand eventually acquired the remaining Plessis buildings in May 1849 and tore them down in 1864. Meanwhile in 1822, Louis-le-Grand had expanded southwards by taking over the former from the University. Louis-le-Grand's main buildings themselves were in an increasingly dilapidated state, implying danger for the students. From the 1840s onwards multiple attempts were made to start their reconstructions, but faltered for several decades. In the mid-1860s, Georges-Eugène Haussmann

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, commonly known as Baron Haussmann (; 27 March 180911 January 1891), was a French official who served as prefect of Seine (1853–1870), chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to carry out a massive urban renewal programme of n ...

promoted a project to move Louis-le-Grand to the premises of the on , but that initiative was short-lived and the complex on rue de Sèvres was instead repurposed a decade later as .

Eventually, Louis-le-Grand was almost entirely reconstructed between 1885 and 1898 on a design by architect , on a complex schedule so that teaching activities could continue during the works, and at a record high cost. Le Coeur's design only preserved the northern and southern sides of the inner court (now ) from the earlier college facilities. He created two vast courtyards to the north () and south () of that central space, with multiple levels of classrooms connected by airy arcaded corridors. That rebuilding project took place the context of broader urban remodeling of the neighborhood around rue Saint-Jacques, also including the rebuilding of the Sorbonne (1884-1901, architect Henri Paul Nénot) and the extension of what is now the Panthéon campus of Paris 2 Panthéon-Assas University

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Sin ...

(1891-1897, architect Ernest Lheureux).

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the neighborhood was hit by Paris Gun

The Paris Gun (german: Paris-Geschütz / Pariser Kanone) was the name given to a type of German long-range siege gun, several of which were used to bombard Paris during World War I. They were in service from March to August 1918. When the guns w ...

shells, known to Parisians as . One shell tore through the ceiling of the main entrance hall on , and another left a large hole in the pavement of rue Saint-Jacques in front of the 's entrance on . During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Jacques Lusseyran founded the resistance group Volontaires de la Liberté, in which a number of his fellow Louis-le-Grand students participated.

The last significant new building project was a new auditorium (french: salle des fêtes), located in the southeastern corner of the premises and completed in the late 1950s.

Louis-le-Grand had its share of May 68

Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting some seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, as well as the occupation of universities and Occupation of factories, factories. At t ...

turmoil and subsequent violence between far-left and far-right student factions. On , it hosted the general assembly of the high-school students' action committees () which called for a general strike. On Jean Tiberi, a gaullist

Gaullism (french: link=no, Gaullisme) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle wi ...

member of parliament who would later become the mayor of Paris, was assaulted during a visit of the . A hand grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern ...

exploded inside its premises in early May 1969.

A collection of the school's old scientific instruments was curated from 1972 and is now managed autonomously as the .

Operations

Louis-le-Grand has about 1,800 students, nearly a tenth of which are non-French from more than 40 countries. About half of these are enrolled in high school, and the other half in the . Its boarding capacity is of 340 inside the building. Together with its longstanding rival the Lycée Henri-IV, Louis-le-Grand has long been the only French that is exempted from the scheme of location-based enrollment known as the , even after the introduction in 2008 of the nationwide application known as . This exemption has been criticized as a breach of territorial equality and a device for the self-perpetuation of French elites. It was decided to reform it in 2022.Notable alumni

Louis-le-Grand has long been considered to play an important role in the education of French elites. In 1762, just before the college's nationalization, scholar Jean-Baptiste-Jacques Élie de Beaumont wrote: "The Jesuit College of Paris has for a long time been a state nursery, the most fertile in great men." Many of its former students have become influential statesmen, diplomats, prelates, writers, artists, intellectuals and scientists. It counts sevenNobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfre ...

laureates as alumni, second only to the Bronx High School of Science

The Bronx High School of Science, commonly called Bronx Science, is a public specialized high school in The Bronx in New York City. It is operated by the New York City Department of Education. Admission to Bronx Science involves passing the Sp ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

, and one Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

. The Louis-le-Grand alumni laureates are, by chronological order of prize-winning: Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy (20 May 182212 June 1912) was a French economist and pacifist who was a founding member of several peace societies and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also an author and politician, sitting in the Chamber of Deputies f ...

(Peace, 1901); Henri Becquerel

Antoine Henri Becquerel (; 15 December 1852 – 25 August 1908) was a French engineer, physicist, Nobel laureate, and the first person to discover evidence of radioactivity. For work in this field he, along with Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pi ...

(Physics, 1903); Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria ...

(Medicine, 1907); Paul d'Estournelles de Constant

Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet d'Estournelles de Constant, Baron de Constant de Rebecque (22 November 1852 – 15 May 1924), was a French diplomat and politician, advocate of international arbitration and winner of the 1909 Nobel Prize for Peac ...

(Peace, 1909); Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production an ...

(Literature, 1915); Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialist, existentialism (and Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter ...

(Literature, 1964); Maurice Allais (Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, 1988); and Serge Haroche

Serge Haroche (born 11 September 1944) is a French-Moroccan physicist who was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physics jointly with David J. Wineland for "ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual ...

(Physics, 2012).

Other notable alumni include:

* statesmen the Cardinal de Fleury, the Duc de Choiseul, the Cardinal de Bernis

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

, the Chancelier de Maupeou, Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Charles Carroll (September 19, 1737 – November 14, 1832), known as Charles Carroll of Carrollton or Charles Carroll III, was an Irish-American politician, planter, and signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He was the only Catholic si ...

, Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

, Camille Desmoulins

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (; 2 March 17605 April 1794) was a French journalist and politician who played an important role in the French Revolution. Desmoulins was tried and executed alongside Georges Danton when the Committee o ...

, Victor Schœlcher, Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social de ...

, Édouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot (; 5 July 1872 – 26 March 1957) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister (1924–1925; 1926; 1932) and twice as President of the Chamber of Deputies. He led the ...

, Edgard Pisani

Edgard Edouard Pisani (; 9 October 1918 – 20 June 2016) was a French statesman, philosopher, and writer.

He was a European Commissioner and Member of the European Parliament.

Biography

Pisani was born in Tunis, French Tunisia, of French paren ...

, Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor (; ; 9 October 1906 – 20 December 2001) was a Senegalese poet, politician and cultural theorist who was the first president of Senegal (1960–80).

Ideologically an African socialist, he was the major theoretician of ...

, Jacques de Larosière, Paul Biya

Paul Biya (born Paul Barthélemy Biya'a bi Mvondo; 13 February 1933) is a Cameroonian politician who has served as the president of Cameroon since 6 November 1982.

; seven French presidents

The president of France is the head of state of France. The first officeholder is considered to be Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who was elected in 1848 and provoked the 1851 self-coup to later proclaim himself emperor as Napoleon III. His coup, w ...

( Raymond Poincaré, Paul Deschanel, Alexandre Millerand, Alain Poher acting, Georges Pompidou

Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou ( , ; 5 July 19112 April 1974) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1969 until his death in 1974. He previously was Prime Minister of France of President Charles de Gaulle from 1962 to 19 ...

, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

and Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988, as well as ...

); and eight Prime Ministers ( Paul Painlevé, Pierre Mendès France

Pierre Isaac Isidore Mendès France (; 11 January 190718 October 1982) was a French politician who served as prime minister of France for eight months from 1954 to 1955. As a member of the Radical Party, he headed a government supported by a co ...

, Michel Debré

Michel Jean-Pierre Debré (; 15 January 1912 – 2 August 1996) was the first Prime Minister of the French Fifth Republic. He is considered the "father" of the current Constitution of France. He served under President Charles de Gaulle from 1 ...

, Maurice Couve de Murville, Pierre Messmer

Pierre Joseph Auguste Messmer (; 20 March 191629 August 2007) was a French Gaullist politician. He served as Minister of Armies under Charles de Gaulle from 1960 to 1969 – the longest serving since Étienne François, duc de Choiseul under Lo ...

, Laurent Fabius

Laurent Fabius (; born 20 August 1946) is a French politician serving as President of the Constitutional Council since 8 March 2016. A member of the Socialist Party, he previously served as Prime Minister of France from 17 July 1984 to 20 M ...

, Michel Rocard

Michel Rocard (; 23 August 1930 – 2 July 2016) was a French politician and a member of the Socialist Party (PS). He served as Prime Minister under François Mitterrand from 1988 to 1991 during which he created the '' Revenu minimum d'i ...

, Alain Juppé

Alain Marie Juppé (; born 15 August 1945) is a French politician. A member of The Republicans (France), The Republicans, he was Prime Minister of France from 1995 to 1997 under President Jacques Chirac, during which period he faced 1995 strikes ...

)

* scientists Évariste Galois

Évariste Galois (; ; 25 October 1811 – 31 May 1832) was a French mathematician and political activist. While still in his teens, he was able to determine a necessary and sufficient condition for a polynomial to be solvable by radicals, ...

, Charles Hermite

Charles Hermite () FRS FRSE MIAS (24 December 1822 – 14 January 1901) was a French mathematician who did research concerning number theory, quadratic forms, invariant theory, orthogonal polynomials, elliptic functions, and algebra.

Herm ...

, Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré ( S: stress final syllable ; 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as "The ...

, Jacques Hadamard

Jacques Salomon Hadamard (; 8 December 1865 – 17 October 1963) was a French mathematician who made major contributions in number theory, complex analysis, differential geometry and partial differential equations.

Biography

The son of a tea ...

, Benoit Mandelbrot, Laurent Schwartz

Laurent-Moïse Schwartz (; 5 March 1915 – 4 July 2002) was a French mathematician. He pioneered the theory of distributions, which gives a well-defined meaning to objects such as the Dirac delta function. He was awarded the Fields Medal in ...

, Laurent Lafforgue, Cédric Villani, Hugo Duminil-Copin

* writers Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

, Bussy-Rabutin, the Marquis de Sade

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (; 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814), was a French nobleman, revolutionary politician, philosopher and writer famous for his literary depictions of a libertine sexuality as well as numerous accusat ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier ( , ; 30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

While an ardent defender of Romanticism, Gautier's work is difficult to classify and rem ...

, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticism inherited ...

, Paul Claudel

Paul Claudel (; 6 August 1868 – 23 February 1955) was a French poet, dramatist and diplomat, and the younger brother of the sculptor Camille Claudel. He was most famous for his verse dramas, which often convey his devout Catholicism.

Early l ...

, Joseph Kessel, Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 26 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popul ...

, Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (; ; 26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author, and politician. He was "one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature" and coined the word in French. He founded the Pa ...

* philosophers and social scientists Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the ''Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promine ...

, Emile Durkheim, Gaston Maspero, Marc Bloch, Julien Benda

Julien Benda (26 December 1867 – 7 June 1956) was a French philosopher and novelist, known as an essayist and cultural critic. He is best known for his short book, ''La Trahison des Clercs'' from 1927 (''The Treason of the Intellectuals'' or ' ...

, Georges Dumézil

Georges Edmond Raoul Dumézil (4 March 189811 October 1986) was a French philologist, linguist, and religious studies scholar who specialized in comparative linguistics and mythology. He was a professor at Istanbul University, École pratique ...

, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Le Goff

Jacques Le Goff (1 January 1924 – 1 April 2014) was a French historian and prolific author specializing in the Middle Ages, particularly the 12th and 13th centuries.

Le Goff championed the Annales School movement, which emphasizes long-term t ...

, Régis Debray

Jules Régis Debray (; born 2 September 1940) is a French philosopher, journalist, former government official and academic. He is known for his theorization of mediology, a critical theory of the long-term transmission of cultural meaning in ...

, Thomas Piketty

* artists Eugène Delacroix

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix ( , ; 26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863) was a French Romantic artist regarded from the outset of his career as the leader of the French Romantic school.Noon, Patrick, et al., ''Crossing the Channel: British ...

, Théodore Géricault

Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault (; 26 September 1791 – 26 January 1824) was a French painter and lithographer, whose best-known painting is '' The Raft of the Medusa''. Although he died young, he was one of the pioneers of the Romantic ...

, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi ( , ; 2 August 1834 – 4 October 1904) was a French sculptor and painter. He is best known for designing ''Liberty Enlightening the World'', commonly known as the Statue of Liberty.

Early life and education

Barthold ...

, Gustave Caillebotte (at the in Vanves), Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard, Georges Méliès

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès (; ; 8 December 1861 – 21 January 1938) was a French illusionist, actor, and film director. He led many technical and narrative developments in the earliest days of cinema.

Méliès was well known for the use o ...

, Jean-Paul Belmondo

Jean-Paul Charles Belmondo (; 9 April 19336 September 2021) was a French actor and producer. Initially associated with the New Wave of the 1960s, he was a major French film star for several decades from the 1960s onward. His best known credits ...

* business leaders André Citroën, André Michelin, Michel Pébereau

Michel Pébereau (born 23 January 1942 in Paris) is a French businessman. He is the current chairman of Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP) and its former CEO. He graduated from the École Polytechnique in 1965 and the École nationale d'adminis ...

, Jean-Charles Naouri

Jean-Charles Naouri (born 8 March 1949 in Bône, Algeria) is a French businessman. He is Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and controlling shareholder of Groupe Casino.

Education

Naouri received his baccalaureat degree at only 15 years old ...

* military leaders Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

, Henri Honoré d'Estienne d'Orves

* religious figures Francis de Sales

Francis de Sales (french: François de Sales; it, Francesco di Sales; 21 August 156728 December 1622) was a Bishop of Geneva and is revered as a saint in the Catholic Church. He became noted for his deep faith and his gentle approach t ...

, Pierre de Bérulle

Pierre de Bérulle (4 February 1575 – 2 October 1629) was a French Catholic priest, cardinal and statesman, one of the most important mystics of the 17th century in France. He was the founder of the French school of spirituality, who could c ...

, the Cardinal de Retz, Dalil Boubakeur

Offshoots

Gentilly estate (1638-1770)

The made a series of purchases in Gentilly to establish a rural retreat there, in 1632, 1638, 1640 and 1659, thus forming a major property that was eventually sold after the order's suppression in the early 1770s. One of its buildings survives and has been repurposed in the 1990s as the

The made a series of purchases in Gentilly to establish a rural retreat there, in 1632, 1638, 1640 and 1659, thus forming a major property that was eventually sold after the order's suppression in the early 1770s. One of its buildings survives and has been repurposed in the 1990s as the Maison de la photographie Robert Doisneau

The Maison de la photographie Robert Doisneau (Robert Doisneau house of photography) is a photography gallery in the Paris suburb of Gentilly, created to commemorate the Parisian photographer Robert Doisneau and dedicated to exhibiting humanist ...

.

in Vanves (1853-1864)

In 1798, Louis-le-Grand (then known as Prytanée) acquired the former grounds of the . In the 1840s it initiated the project of establishing there an annex, known as the . In 1853 this became the sole location of its ormiddle school

A middle school (also known as intermediate school, junior high school, junior secondary school, or lower secondary school) is an educational stage which exists in some countries, providing education between primary school and secondary school ...

. The facilities were expanded in 1858-1860 on a design by Joseph-Louis Duc. It became an independent establishment by imperial decree in August 1864, known since 1888 as the Lycée Michelet.

on the Jardin du Luxembourg (1885-1891)

In 1882, a law awarded a former tree nursery ground of the

In 1882, a law awarded a former tree nursery ground of the Jardin du Luxembourg

The Jardin du Luxembourg (), known in English as the Luxembourg Garden, colloquially referred to as the Jardin du Sénat (Senate Garden), is located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France. Creation of the garden began in 1612 when Marie de ...

to Louis-le-Grand for the creation of new classrooms, in anticipation of the main building's reconstruction. The new , also designed by , opened in 1885 and became independent in August 1891 as the Lycée Montaigne.

Abu Dhabi Section (2008-2017)

In September 2008, Louis-le-Grand and the Abu Dhabi Education Council launched the Advanced Math and Science Pilot Class, with one class of 20 girls and another of 20 boys. Classes were taught in English in Abu Dhabi, by professors sent from France. The students who made up the Advanced Math and Science Pilot Class graduated at the end of the 12th grade and were awarded a certificate of academic recognition by Louis-le-Grand. The final cohort of the program graduated in 2017, marking the end of the program.Gallery

See also

* List of Lycée Louis-le-Grand people *List of Jesuit sites

This list includes past and present buildings, facilities and institutions associated with the Society of Jesus. In each country, sites are listed in chronological order of start of Jesuit association.

Nearly all these sites have bee ...

* College of Navarre

* Lycée Henri-IV

* Secondary education in France

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

* List of schools in France

This is a list of schools in France

* Lycée Saint-Louis-de-Gonzague, Paris

* École Canadienne Bilingue de Paris

* Notre-Dame International High School, Verneuil-sur-Seine

* L’Ensemble Scolaire Maurice-Tièche, Collonges-sous-Salève

* Lycé ...

References

External links

(These pages are in French)Lycée Louis-le-Grand

(official website)

Homepage of the parents' association FCPE

Homepage of the parents' association PEEP

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lycee Louis le Grand 1563 establishments in France Buildings and structures in the 5th arrondissement of Paris Jesuit secondary schools in France Jesuit universities and colleges Educational institutions established in the 1560s