Lumumba Sayers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 to Julienne Wamato Lomendja and her husband, François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer, in Onalua, in the

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 to Julienne Wamato Lomendja and her husband, François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer, in Onalua, in the

After his release, Lumumba helped found the ''

After his release, Lumumba helped found the ''

Once it was apparent that Lumumba's bloc controlled parliament, several members of the opposition became eager to negotiate for a coalition government in order to share power. By 22 June 1960, Lumumba had a government list, but negotiations continued with

Once it was apparent that Lumumba's bloc controlled parliament, several members of the opposition became eager to negotiate for a coalition government in order to share power. By 22 June 1960, Lumumba had a government list, but negotiations continued with  The chamber proceeded to engage in a heated debate. Though the government contained members from parties that held 120 of the 137 seats, reaching a majority was not a straightforward task. While several leaders of the opposition had been involved in the formative negotiations, their parties as a whole had not been consulted. Furthermore, some individuals were upset they had not been included in the government and sought to personally prevent its investiture. In the subsequent arguments, multiple deputies expressed dissatisfaction at the lack of representation of their respective provinces and/or parties, with several threatening secession. Among them was Kalonji, who said he would encourage people of Kasaï to refrain from participating in the central government and form their own autonomous state. One Katangese deputy objected to the same person being appointed as premier and as head of the defence portfolio. When a vote was finally taken, only 80 of the 137 members of the chamber were present. Of these, 74 voted in favour of the government, five against, and one abstained. The 57 absences were almost all voluntary. Though the government had earned just as many votes as when Kasongo won the presidency of the chamber, the support was not congruent; members of

The chamber proceeded to engage in a heated debate. Though the government contained members from parties that held 120 of the 137 seats, reaching a majority was not a straightforward task. While several leaders of the opposition had been involved in the formative negotiations, their parties as a whole had not been consulted. Furthermore, some individuals were upset they had not been included in the government and sought to personally prevent its investiture. In the subsequent arguments, multiple deputies expressed dissatisfaction at the lack of representation of their respective provinces and/or parties, with several threatening secession. Among them was Kalonji, who said he would encourage people of Kasaï to refrain from participating in the central government and form their own autonomous state. One Katangese deputy objected to the same person being appointed as premier and as head of the defence portfolio. When a vote was finally taken, only 80 of the 137 members of the chamber were present. Of these, 74 voted in favour of the government, five against, and one abstained. The 57 absences were almost all voluntary. Though the government had earned just as many votes as when Kasongo won the presidency of the chamber, the support was not congruent; members of  Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960 in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries, including King Baudouin of Belgium and the foreign press.fr,nl

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960 in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries, including King Baudouin of Belgium and the foreign press.fr,nl

/ref> Baudouin's speech praised developments under colonialism, his reference to the "genius" of his great-granduncle

Ludo De Witte, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso; , pp. 1–3 President Kasa-Vubu thanked the King. Lumumba, who had not been scheduled to speak, delivered an impromptu speech that reminded the audience that the independence of the Congo had not been granted magnanimously by Belgium: Most European journalists were shocked by the stridency of Lumumba's speech. The Western media criticised him. ''

On the morning of 5 July 1960, General

On the morning of 5 July 1960, General

Lumumba decided to travel to New York City in order to personally express the position of his government to the United Nations. Shortly before his departure, he announced that he had signed an economic agreement with a U.S. businessman who had created the Congo International Management Corporation (CIMCO). According to the contract (which had yet to be ratified by parliament), CIMCO was to form a

Lumumba decided to travel to New York City in order to personally express the position of his government to the United Nations. Shortly before his departure, he announced that he had signed an economic agreement with a U.S. businessman who had created the Congo International Management Corporation (CIMCO). According to the contract (which had yet to be ratified by parliament), CIMCO was to form a

On 9 August Lumumba proclaimed a

On 9 August Lumumba proclaimed a

President Kasa-Vubu began fearing a Lumumbist coup d'état would take place. On the evening of 5 September, Kasa-Vubu announced over radio that he had dismissed Lumumba and six of his ministers from the government for the massacres in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets in the Congo. Upon hearing the broadcast, Lumumba went to the national radio station, which was under UN guard. Though they had been ordered to bar Lumumba's entry, the UN troops allowed the prime minister in, as they had no specific instructions to use force against him. Lumumba denounced his dismissal over the radio as illegitimate, and in turn labelled Kasa-Vubu a traitor and declared him deposed. Kasa-Vubu had not declared the approval of any responsible ministers of his decision, making his action legally invalid. Lumumba noted this in a letter to Hammarskjöld and a radio broadcast at 05:30 on 6 September. Later that day Kasa-Vubu managed to secure the countersignatures to his order of Albert Delvaux, Minister Resident in Belgium, and

President Kasa-Vubu began fearing a Lumumbist coup d'état would take place. On the evening of 5 September, Kasa-Vubu announced over radio that he had dismissed Lumumba and six of his ministers from the government for the massacres in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets in the Congo. Upon hearing the broadcast, Lumumba went to the national radio station, which was under UN guard. Though they had been ordered to bar Lumumba's entry, the UN troops allowed the prime minister in, as they had no specific instructions to use force against him. Lumumba denounced his dismissal over the radio as illegitimate, and in turn labelled Kasa-Vubu a traitor and declared him deposed. Kasa-Vubu had not declared the approval of any responsible ministers of his decision, making his action legally invalid. Lumumba noted this in a letter to Hammarskjöld and a radio broadcast at 05:30 on 6 September. Later that day Kasa-Vubu managed to secure the countersignatures to his order of Albert Delvaux, Minister Resident in Belgium, and

On 14 September Mobutu announced over the radio that he was launching a "

On 14 September Mobutu announced over the radio that he was launching a "

Lumumba was sent first on 3 December 1960 to

Lumumba was sent first on 3 December 1960 to

, ''New York Times'', 6 February 2002. Lumumba's execution was carried out by a firing squad led by Belgian mercenary Julien Gat;''The Assassination of Lumumba''

Ludo De Witte, 2003, Katangan Police Commissioner Verscheure, who was Belgian, had overall command of the execution site. The separatist Katangan regime was heavily supported by the Belgian mining conglomerate

Opening the Secret Files on Lumumba's Murder

, ''Washington Post'', 21 July 2001. The same disclosure showed that, at the time, the U.S. government believed that Lumumba was a communist, and feared him because of what it considered the threat of the Soviet Union in the Cold War. In 2000, a newly declassified interview with Robert Johnson, who was the minutekeeper of the

"MI6 'arranged Cold War killing' of Congo prime minister"

''The Guardian'', 1 April 2013. According to Lea, when he mentioned "the uproar" surrounding Lumumba's abduction and murder, and recalled the theory that MI6 might have had "something to do with it", Park replied, "We did. I organised it.""Letters"

''

''

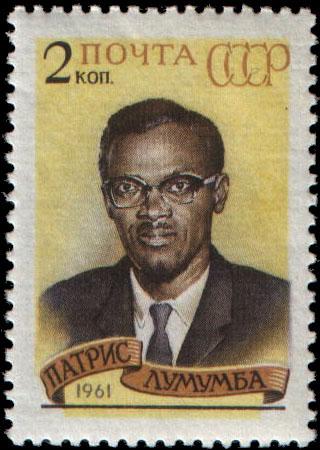

In 1961 Adoula became Prime Minister of the Congo. Shortly after assuming office he went to Stanleyville and laid a wreath of flowers at an impromptu monument established for Lumumba. After Tshombe became Prime Minister in 1964, he also went to Stanleyville and did the same. On 30 June 1966, Mobutu rehabilitated Lumumba's image and proclaimed him a "national hero". By a presidential decree, the Brouwez House, site of Lumumba's torture on the night of his murder, became a place of pilgrimage in the Congo. He declared a series of other measures meant to commemorate Lumumba, though few of these were ever executed aside from the release of a banknote with his visage the subsequent year. This banknote was the only paper money during Mobutu's rule that bore the face of a leader other than the incumbent president. In following years state mention of Lumumba declined and Mobutu's regime viewed unofficial tributes to him with suspicion. Following Laurent-Désiré Kabila's seizure of power in the 1990s, a new line of Congolese francs was issued bearing Lumumba's image. In January 2003 Joseph Kabila, who succeeded his father as president, inaugurated a statue of Lumumba. In Guinea, Lumumba was featured on a coin and two regular banknotes despite not having any national ties to the country. This was an unprecedented occurrence in the modern history of national currency, as images of foreigners are normally reserved only for specially-released commemorative money. As of 2020, Lumumba has been featured on 16 different postage stamps. Many streets and public squares around the world have been named after him. The Peoples' Friendship University of the USSR was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961. It was renamed again in 1992.

In 1961 Adoula became Prime Minister of the Congo. Shortly after assuming office he went to Stanleyville and laid a wreath of flowers at an impromptu monument established for Lumumba. After Tshombe became Prime Minister in 1964, he also went to Stanleyville and did the same. On 30 June 1966, Mobutu rehabilitated Lumumba's image and proclaimed him a "national hero". By a presidential decree, the Brouwez House, site of Lumumba's torture on the night of his murder, became a place of pilgrimage in the Congo. He declared a series of other measures meant to commemorate Lumumba, though few of these were ever executed aside from the release of a banknote with his visage the subsequent year. This banknote was the only paper money during Mobutu's rule that bore the face of a leader other than the incumbent president. In following years state mention of Lumumba declined and Mobutu's regime viewed unofficial tributes to him with suspicion. Following Laurent-Désiré Kabila's seizure of power in the 1990s, a new line of Congolese francs was issued bearing Lumumba's image. In January 2003 Joseph Kabila, who succeeded his father as president, inaugurated a statue of Lumumba. In Guinea, Lumumba was featured on a coin and two regular banknotes despite not having any national ties to the country. This was an unprecedented occurrence in the modern history of national currency, as images of foreigners are normally reserved only for specially-released commemorative money. As of 2020, Lumumba has been featured on 16 different postage stamps. Many streets and public squares around the world have been named after him. The Peoples' Friendship University of the USSR was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961. It was renamed again in 1992.

Speeches and writings by and about Patrice Lumumba

a

''the Marxists Internet Archive''

Patrice Lumumba: 50 Years Later, Remembering the U.S.-Backed Assassination

nbsp;– video report by ''

SpyCast

nbsp;– 1 December 2007: On Assignment to Congo-Peter chats with Larry Devlin, the CIA's legendary station chief in Congo during the 1960s.

A rich source of information on Lumumba, including a reprint of Stephen R. Weissman's 21 July 2002 article from the ''Washington Post''.

BBC

Lumumba apology: Congo's mixed feelings.

Lumumba assassination. * Documentary of Lumumba's life and work in the Congo.

BBC

An "On this day" text. It features an audio clip of a BBC correspondent on Lumumba's death.

English translation

of Lumumba's speech at the 1960 independence day ceremony

Patrice Lumumba

Royal Museum for Central Africa {{DEFAULTSORT:Lumumba, Patrice 1925 births 1961 deaths 1961 murders in Africa African and Black nationalists African revolutionaries Anti-imperialism Assassinated Democratic Republic of the Congo politicians Deaths by firearm in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Democratic Republic of the Congo pan-Africanists Democratic Republic of the Congo torture victims Évolués Executed Democratic Republic of the Congo people Executed prime ministers Heads of government who were later imprisoned Leaders ousted by a coup Lumumba Government members Male murder victims Mouvement National Congolais politicians People from Sankuru People killed in Belgian intelligence operations People of the Congo Crisis Prime Ministers of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Tetela people

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

(then known as the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

) from June until September 1960. A member of the Congolese National Movement

The Congolese National Movement (french: Mouvement national Congolais, or MNC) is a political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

History Foundation

The MNC was founded in 1958 as an African nationalist party within the Belgian Con ...

(MNC), he led the MNC from 1958 until his execution in January 1961. Ideologically an African nationalist

African nationalism is an umbrella term which refers to a group of political ideologies in sub-Saharan Africa, which are based on the idea of national self-determination and the creation of nation states.pan-Africanist

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

, he played a significant role in the transformation of the Congo from a colony of Belgium into an independent republic.

Shortly after Congolese independence in 1960, a mutiny broke out in the army, marking the beginning of the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...

. Lumumba appealed to the United States and the United Nations for help to suppress the Belgian-supported Katangan secessionists led by Moïse Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe (sometimes written Tshombé) (10 November 1919 – 29 June 1969) was a Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of Katanga from 1960 to 1963 and as prime minister of the Re ...

. Both refused, due to suspicions among the Western world that Lumumba secretly held pro-communist views. These suspicions deepened when Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

for assistance, which the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

described as a "classic communist takeover". This led to growing differences with President Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of the Kong ...

and chief-of-staff Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the List of heads of state of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, presiden ...

, as well as with the United States and Belgium, who opposed the Soviet Union in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

.

After Mobutu's military coup, Lumumba attempted to escape to Stanleyville to join his supporters who had established a new anti-Mobutu rival state called the Free Republic of the Congo

The Free Republic of the Congo (french: République Libre du Congo), often referred to as Congo-Stanleyville, was a short-lived rival government to the Republic of the Congo (Congo-Léopoldville) based in the eastern Congo and led by Antoine Gi ...

. Lumumba was captured and imprisoned en route by state authorities under Mobutu. He was handed over to Katangan authorities, and executed in the presence of Katangan and Belgian officials and officers. His body was thrown into a shallow grave, but later dug up and destroyed. Following his execution, he was widely seen as a martyr for the wider pan-African movement. Over the years, inquiries have shed light on the events surrounding Lumumba's death and, in particular, on the roles played by Belgium and the United States. In 2002, Belgium formally apologised for its role in the execution. In 2022, a gold-capped tooth, all that remained of his body, was repatriated to the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Belgium.

Early life and career

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 to Julienne Wamato Lomendja and her husband, François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer, in Onalua, in the

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 to Julienne Wamato Lomendja and her husband, François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer, in Onalua, in the Katakokombe Katako-Kombe is a territory of Sankuru Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and is part of the region known as Kasaï. It is traditionally considered the homeland of the Tetela people. It is also the birthplace of the Congo’s first p ...

region of the Kasai province of the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

. He was a member of the Tetela ethnic group and was born with the name Élias Okit'Asombo. His original surname means "heir of the cursed" and is derived from the Tetela words / ('heir', 'successor') and ('cursed or bewitched people who will die quickly'). He had three brothers (Charles Lokolonga, Émile Kalema, and Louis Onema Pene Lumumba) and one half-brother (Jean Tolenga). Raised in a Catholic family, he was educated at a Protestant primary school, a Catholic missionary school, and finally the government post office training school, where he passed the one-year course with distinction. He was known for being a vocal, precocious young man, regularly pointing out the errors of his teachers in front of his peers, often to their chagrin. This outspoken nature would come to define his life and career. Lumumba spoke Tetela, French, Lingala

Lingala (Ngala) (Lingala: ''Lingála'') is a Bantu language spoken in the northwest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the northern half of the Republic of the Congo, in their capitals, Kinshasa and Brazzaville, and to a lesser degree in ...

, Swahili, and Tshiluba.

Outside of his regular studies, Lumumba took an interest in the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

ideals of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

and Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

. He was also fond of Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

and Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

. He wrote poetry, and many of his works had anti-imperialist themes. He worked as a travelling beer salesman in Léopoldville and as a postal clerk in a Stanleyville post office for eleven years. Lumumba was married three times. He married Henriette Maletaua a year after arriving in Stanleyville, but they were divorced in 1947. In the same year, he married Hortense Sombosia, but this relationship also fell apart and he began an affair with Pauline Kie. While he had no children with his first two wives, his relationship with Kie resulted in a son, François Lumumba

François Emery Tolenga Lumumba, alternatively François Hemery Flory, (born 20 September 1951) is a Congolese politician, the son of Patrice Lumumba, and the leader of a faction of the Mouvement National Congolais-Lumumba (MNC-L).

François' fat ...

. Though he remained close with Kie until his death, Lumumba ultimately ended their affair to marry a girl from his home region in 1951: Pauline Opangu

Pauline Opango Lumumba (January 1, 1937 – December 23, 2014), also known as Pauline Opangu, was a Congolese activist, and the wife of Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of Cong ...

. In the period following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, young leaders across Africa increasingly worked for national goals and independence from the colonial powers. In 1952 he was hired to work as a personal assistant for French sociologist Pierre Clément, who was performing a study of Stanleyville. That year he also co-founded and subsequently became president of a Stanleyville chapter of the Association des Anciens élèves des pères de Scheut (ADAPÉS), an alumni association for former students at Scheut

Scheut is a district of Anderlecht, a municipality of Brussels, Belgium. Located in the north of Anderlecht, it is bounded by the border with the municipality of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean to the north, the historical centre of Anderlecht to the sout ...

schools, despite the fact that he had never attended one. In 1955, Lumumba became regional head of the ''Cercles'' of Stanleyville and joined the Liberal Party of Belgium. He edited and distributed party literature. Between 1956 and 1957 he wrote his autobiography (which would not be published until 1961, just months before he was killed). After a study tour in Belgium in 1956, he was arrested on charges of embezzlement of $2500 from the post office. He was convicted and sentenced one year later to 12 months' imprisonment and a fine.

Leader of the MNC

After his release, Lumumba helped found the ''

After his release, Lumumba helped found the ''Mouvement National Congolais

The Congolese National Movement (french: Mouvement national Congolais, or MNC) is a political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

History Foundation

The MNC was founded in 1958 as an African nationalist party within the Belgian Con ...

'' (MNC) party on 5 October 1958, and quickly became the organisation's leader. The MNC, unlike other Congolese parties developing at the time, did not draw on a particular ethnic base. It promoted a platform that included independence, gradual Africanisation

Africanization or Africanisation (lit., making something African) has been applied in various contexts, notably in geographic and personal naming and in the composition of the civil service via processes such as indigenization.

Africanization ...

of the government, state-led economic development, and neutrality in foreign affairs. Lumumba had a large popular following, due to his personal charisma, excellent oratory, and ideological sophistication. As a result, he had more political autonomy than contemporaries who were more dependent on Belgian connections. Lumumba was one of the delegates who represented the MNC at the All-African Peoples' Conference

The All-African Peoples Conference (AAPC) was partly a corollary and partly a different perspective to the modern Africa states represented by the Conference of Heads of independent Africa States. The All-Africa Peoples Conference was conceived to ...

in Accra

Accra (; tw, Nkran; dag, Ankara; gaa, Ga or ''Gaga'') is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , ...

, Ghana, in December 1958. At this international conference, hosted by Ghanaian president, Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

, Lumumba further solidified his pan-African

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

ist beliefs. Nkrumah was personally impressed by Lumumba's intelligence and ability. In late October 1959, Lumumba, as leader of the MNC, was arrested for inciting an anti-colonial riot in Stanleyville; 30 people were killed. He was sentenced to six months in prison. The trial's start date of 18 January 1960 was the first day of the Congolese Round Table Conference

The Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference (french: Table ronde belgo-congolaise) was a meeting organized in two partsJoseph Kamanda Kimona-Mbinga"La stabilité du Congo-Kinshasa: enjeux et perspectives"2004 in 1960 in Brussels (January 20 – F ...

in Brussels, intended to make a plan for the future of the Congo. Despite Lumumba's imprisonment, the MNC won a convincing majority in the December local elections in the Congo. As a result of strong pressure from delegates upset by Lumumba's trial, he was released and allowed to attend the Brussels conference.

Independence and election as prime minister

The conference culminated on 27 January 1960 with a declaration of Congolese independence. It set 30 June 1960 as the independence date with national elections to be held from 11 to 25 May 1960. The MNC won a plurality in the election. Six weeks before the date of independence,Walter Ganshof van der Meersch

Walter Jean Ganshof van der Meersch (18 May 1900 – 12 September 1993) was a Belgian jurist and lawyer. He competed in the four-man bobsledding event at the 1928 Winter Olympics

The 1928 Winter Olympics, officially known as the II Olymp ...

was appointed as the Belgian Minister of African Affairs. He lived in Léopoldville, in effect becoming Belgium's ''de facto'' resident minister in the Congo, administering it jointly with Governor-general Hendrik Cornelis

Hendrik "Rik" Cornelis (1910–1999) was a Belgian colonial civil servant who served as the final Governor-General of the Belgian Congo from 1958 to 1960. His term ended with the independence of the Republic of the Congo.

Cornelis was born in Be ...

. He was charged with advising King Baudouin

Baudouin (;, ; nl, Boudewijn Albert Karel Leopold Axel Maria Gustaaf, ; german: Balduin Albrecht Karl Leopold Axel Maria Gustav. 7 September 1930 – 31 July 1993), Dutch name Boudewijn, was King of the Belgians from 17 July 1951 until his dea ...

on the selection of a . On 8 June 1960, Ganshof flew to Brussels to meet with Baudouin. He made three suggestions for : Lumumba, as the winner of the elections; Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of the Kong ...

, the only figure with a reliable national reputation who was associated with the coalescing opposition; or some to-be-determined third individual who could unite the competing blocs. Ganshof returned to the Congo on 12 June 1960. The following day he appointed Lumumba to serve as the delegate () tasked with investigating the possibility of forming a national unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nati ...

that included politicians with a wide range of views, with 16 June 1960 as his deadline.

The same day as Lumumba's appointment, the parliamentary opposition coalition, the , was announced. Though Kasa-Vubu was aligned with their beliefs, he remained distanced from them. The MNC-L was also having trouble securing the allegiances of the PSA

PSA, PsA, Psa, or psa may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Posterior spinal artery

* Primary systemic amyloidosis, a disease caused by the accumulation of abnormal proteins

* Prostate-specific antigen, an enzyme used as a blood tracer for pros ...

, CEREA (), and BALUBAKAT (). Initially, Lumumba was unable to establish contact with members of the cartel. Eventually several leaders were appointed to meet with him, but their positions remained entrenched. On 16 June 1960, Lumumba reported his difficulties to Ganshof, who extended the deadline and promised to act as an intermediary between the MNC leader and the opposition. Once Ganshof had made contact with the cartel leadership, he was impressed by their obstinacy and assurances of a strong anti-Lumumba polity. By evening, Lumumba's mission was showing even less chance of succeeding. Ganshof considered extending the role of to Cyrille Adoula

Cyrille Adoula (13 September 1921 – 24 May 1978) was a Congolese trade unionist and politician. He was the prime minister of the Republic of the Congo, from 2 August 1961 until 30 June 1964.

Early life and career

Cyrille Adoula was born to ...

and Kasa-Vubu, but faced increasing pressure from Belgian and moderate Congolese advisers to end Lumumba's assignment. The following day, on 17 June 1960, Ganshof declared that Lumumba had failed and terminated his mission. Acting on Ganshof's advice, Baudouin then named Kasa-Vubu . Lumumba responded by threatening to form his own government and present it to parliament without official approval. He called a meeting at the OK Bar in Léopoldville, where he announced the creation of a "popular" government with the support of Pierre Mulele

Pierre Mulele (11 August 1929 – 3 or 9 October 1968) was a Congolese rebel active in the Simba rebellion of 1964. Mulele had also been minister of education in Patrice Lumumba's cabinet. With the assassination of Lumumba in January 1961 and ...

of the PSA. Meanwhile, Kasa-Vubu, like Lumumba, was unable to communicate with his political opponents.

He assumed that he would secure the presidency, so he began looking for someone to serve as his prime minister. Most of the candidates he considered were friends who had foreign support similar to his own, including Albert Kalonji

Albert Kalonji Ditunga (6 June 1929 – 20 April 2015) was a Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congolese politician best known as the leader of the short-lived secessionist state of South Kasai (''Sud-Kasaï'') during the Congo Crisis.

Ear ...

, Joseph Iléo

Joseph Iléo (15 September 1921 – 19 September 1994), subsequently Zairianised as Sombo Amba Iléo, was a politician in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and was prime minister for two periods.

Early life

Joseph Iléo was born on 15 ...

, Cyrille Adoula, and Justin Bomboko

Justin-Marie Bomboko Lokumba Is Elenge (22 September 1928 – 10 April 2014), was a Congolese politician and statesman. He was the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Congo. He served as leader of the Congolese government as chairman of the Coll ...

. Kasa-Vubu, was slow to come to a final decision. On 18 June 1960, Kasa-Vubu announced that he had completed his government with all parties except the MNC-Lumumba. That afternoon Jason Sendwe

Jason Sendwe (1917 – 19 June 1964) was a Congolese politician and a leader of the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT) party. He served as Second Deputy Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic ...

, Antoine Gizenga

Antoine Gizenga (5 October 1925 – 24 February 2019) was a Congolese (DRC) politician who was the Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 30 December 2006 to 10 October 2008. He was the Secretary-General of the Unified Lumum ...

, and Anicet Kashamura

Anicet Kashamura (17 December 1928 – 18 August 2004) was a Congolese politician.

Biography

Anicet Kashamura was born in 1928 in the Kalehe Territory, locality of Kalehe in Kivu, Kivu Province, Belgian Congo. From 1948 to 1956 he worked as an a ...

announced in the presence of Lumumba that their respective parties were not committed to the government. The next day, on 19 June 1960, Ganshof summoned Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba to a meeting so they could forge a compromise. This failed when Lumumba flatly refused the position of prime minister in a Kasa-Vubu government. The following day, on 20 June 1960, the two rivals met in the presence of Adoula and diplomats from Israel and Ghana, but no agreement was reached. Most party leaders refused to support a government that did not include Lumumba. The decision to make Kasa-Vubu the was a catalyst that rallied the PSA, CEREA, and BALUBAKAT to Lumumba, making it unlikely that Kasa-Vubu could form a government that would survive a vote of confidence. When the chamber met, on 21 June 1960, to select its officers, Joseph Kasongo

Joseph-Georges Kasongo (25 December 1919 – 19 October 1990) was a Tanganyikan-born Congolese lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the first President of the Chamber of Deputies of the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Rep ...

of the MNC-L was elected president with 74 votes (a majority), while the two vice presidencies were secured by the PSA and CEREA candidates, both of whom had the support of Lumumba. With time running out before independence, Baudouin took new advice from Ganshof and appointed Lumumba as .

Once it was apparent that Lumumba's bloc controlled parliament, several members of the opposition became eager to negotiate for a coalition government in order to share power. By 22 June 1960, Lumumba had a government list, but negotiations continued with

Once it was apparent that Lumumba's bloc controlled parliament, several members of the opposition became eager to negotiate for a coalition government in order to share power. By 22 June 1960, Lumumba had a government list, but negotiations continued with Jean Bolikango

Jean Bolikango, later Bolikango Akpolokaka Gbukulu Nzete Nzube (4 February 1909 – 17 February 1982), was a Congolese educator, writer, and conservative politician. He served twice as Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo (now the ...

, Albert Delvaux, and Kasa-Vubu. Lumumba reportedly offered the Alliance of Bakongo (ABAKO) the ministerial positions for foreign affairs and middle classes, but Kasa-Vubu instead demanded the ministry of finance, a minister of state, the secretary of state for the interior, and a written pledge of support from the MNC-L and its allies for his presidential candidacy. Kalonji was presented with the agriculture portfolio by Lumumba, which he rejected, although he was suitable due to his experience as an agricultural engineer. Adoula was also offered a ministerial position, but refused to accept it. By the morning of 23 June 1960, the government was, in the words of Lumumba, "practically formed". At noon, he made a counter-offer to Kasa-Vubu, who instead responded with a letter demanding the creation of a seventh province for the Bakongo

The Kongo people ( kg, Bisi Kongo, , singular: ; also , singular: ) are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have lived ...

. Lumumba refused to comply and instead pledged to support Jean Bolikango in his bid for the presidency.

At 14:45, he presented his proposed government before the press. Neither the ABAKO nor the MNC-Kalonji (MNC-K) were represented among the ministers, and the only PSA members were from Gizenga's wing of the party. The Bakongo of Léopoldville were deeply upset by their exclusion from Lumumba's cabinet. They subsequently demanded the removal of the PSA-dominated provincial government and called for a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

to begin the following morning. At 16:00, Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu resumed negotiations. Kasa-Vubu eventually agreed to Lumumba's earlier offer, though Lumumba informed him that he could not give him a guarantee of support in his presidential candidacy. The resulting 37-strong Lumumba government

The Lumumba Government (french: Gouvernement Lumumba), also known as the Lumumba Ministry or Lumumba Cabinet, was the first set of ministers, ministers of state, and secretaries of state that governed the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Re ...

was very diverse, with its members coming from different classes, different tribes, and holding varied political beliefs. Though many had questionable loyalty to Lumumba, most did not openly contradict him out of political considerations or fear of reprisal. At 22:40 on 23 June 1960, the Chamber of Deputies convened in the to vote on Lumumba's government. After Kasongo opened the session, Lumumba delivered his main speech, promising to maintain national unity, abide by the will of the people, and pursue a neutralist

A neutral country is a state that is neutral towards belligerents in a specific war or holds itself as permanently neutral in all future conflicts (including avoiding entering into military alliances such as NATO, CSTO or the SCO). As a type of ...

foreign policy. It was warmly received by most deputies and observers.

The chamber proceeded to engage in a heated debate. Though the government contained members from parties that held 120 of the 137 seats, reaching a majority was not a straightforward task. While several leaders of the opposition had been involved in the formative negotiations, their parties as a whole had not been consulted. Furthermore, some individuals were upset they had not been included in the government and sought to personally prevent its investiture. In the subsequent arguments, multiple deputies expressed dissatisfaction at the lack of representation of their respective provinces and/or parties, with several threatening secession. Among them was Kalonji, who said he would encourage people of Kasaï to refrain from participating in the central government and form their own autonomous state. One Katangese deputy objected to the same person being appointed as premier and as head of the defence portfolio. When a vote was finally taken, only 80 of the 137 members of the chamber were present. Of these, 74 voted in favour of the government, five against, and one abstained. The 57 absences were almost all voluntary. Though the government had earned just as many votes as when Kasongo won the presidency of the chamber, the support was not congruent; members of

The chamber proceeded to engage in a heated debate. Though the government contained members from parties that held 120 of the 137 seats, reaching a majority was not a straightforward task. While several leaders of the opposition had been involved in the formative negotiations, their parties as a whole had not been consulted. Furthermore, some individuals were upset they had not been included in the government and sought to personally prevent its investiture. In the subsequent arguments, multiple deputies expressed dissatisfaction at the lack of representation of their respective provinces and/or parties, with several threatening secession. Among them was Kalonji, who said he would encourage people of Kasaï to refrain from participating in the central government and form their own autonomous state. One Katangese deputy objected to the same person being appointed as premier and as head of the defence portfolio. When a vote was finally taken, only 80 of the 137 members of the chamber were present. Of these, 74 voted in favour of the government, five against, and one abstained. The 57 absences were almost all voluntary. Though the government had earned just as many votes as when Kasongo won the presidency of the chamber, the support was not congruent; members of Cléophas Kamitatu

Cléophas Kamitatu Massamba (10 June 1931 – 12 October 2008) was a Congolese politician and leader of the ''Parti Solidaire Africain''.

Biography

Cléophas Kamitatu was born on 10 June 1931 in Kilombo-Masi, Masi-Manimba Territory, Kwilu Prov ...

's wing of the PSA had voted against the government while a few members of the PNP, PUNA, and ABAKO voted in favour of it. Overall, the vote was a disappointment for the MNC-L coalition.

The session was adjourned at 02:05 on 24 June 1960. The senate convened that day to vote on the government. There was another heated debate, in which Iléo and Adoula expressed their strong dissatisfaction with its composition. Confederation of Tribal Associations of Katanga (CONAKAT) members abstained from voting. When arguments concluded, a decisive vote of approval was taken on the government: 60 voted in favour, 12 against, while eight abstained. All dissident arguments for alternative cabinets, particularly Kalonji's demand for a new administration, were rendered impotent, and the Lumumba government was officially invested. With the institution of a broad coalition, the parliamentary opposition was officially reduced to only the MNC-K and some individuals. At the onset of his premiership, Lumumba had two main goals: to ensure that independence would bring a legitimate improvement in the quality of life for the Congolese and to unify the country as a centralised state by eliminating tribalism

Tribalism is the state of being organized by, or advocating for, tribes or tribal lifestyles. Human evolution has primarily occurred in small hunter-gatherer groups, as opposed to in larger and more recently settled agricultural societies or civ ...

and regionalism. He was worried that opposition to his government would appear rapidly and would have to be managed quickly and decisively.

To achieve the first aim, Lumumba believed that a comprehensive "Africanisation

Africanization or Africanisation (lit., making something African) has been applied in various contexts, notably in geographic and personal naming and in the composition of the civil service via processes such as indigenization.

Africanization ...

" of the administration, in spite of its risks, would be necessary. The Belgians were opposed to such an idea, as it would create inefficiency in the Congo's bureaucracy and lead to a mass exodus of unemployed civil servants to Belgium, whom they would be unable to absorb into the government there. It was too late for Lumumba to enact Africanisation before independence. Seeking another gesture that might excite the Congolese people, Lumumba proposed to the Belgian government a reduction in sentences for all prisoners and an amnesty for those serving a term of three years or less. Ganshof feared that such an action would jeopardise law and order, and he evaded taking any action until it was too late to fulfill the request. Lumumba's opinion of the Belgians was soured by this affair, which contributed to his fear that independence would not appear "real" to the average Congolese. In seeking to eliminate tribalism and regionalism in the Congo, Lumumba was deeply inspired by the personality and undertakings of Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

and by Ghanaian ideas of the leadership necessary in post-colonial Africa. He worked to seek such changes through the MNC. Lumumba intended to combine it with its parliamentary allies—CEREA, the PSA, and possibly BALUBAKAT—to form one national party, and to build a following in each province. He hoped it would absorb other parties and become a unifying force for the country.

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960 in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries, including King Baudouin of Belgium and the foreign press.fr,nl

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June 1960 in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries, including King Baudouin of Belgium and the foreign press.fr,nl/ref> Baudouin's speech praised developments under colonialism, his reference to the "genius" of his great-granduncle

Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

, glossing over atrocities committed during his reign over the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

.Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild (; born October 5, 1942) is an American author, journalist, historian and lecturer. His best-known works include ''King Leopold's Ghost'' (1998), '' To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914–1918'' (2011), ''Bur ...

, '' King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa'', 1999, Mariner Books, Belgian prime minister Gaston Eyskens

Gaston François Marie, viscount Eyskens (1 April 1905 – 3 January 1988) was a Christian democratic politician and prime minister of Belgium. He was also an economist and member of the Belgian Christian Social Party (CVP-PSC).

He served t ...

, who checked the text, thought this passage went too far. He wanted to drop this reference to Léopold II. The King had limited political power in Belgium, but he was free to write his own speeches (after revision by the government). The King continued, "Don't compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don't replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better. Don't be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side, give you advice."''The Assassination of Lumumba''Ludo De Witte, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso; , pp. 1–3 President Kasa-Vubu thanked the King. Lumumba, who had not been scheduled to speak, delivered an impromptu speech that reminded the audience that the independence of the Congo had not been granted magnanimously by Belgium: Most European journalists were shocked by the stridency of Lumumba's speech. The Western media criticised him. ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine characterised his speech as a "venomous attack". In the West, many feared that the speech was a call to arms that would revive Belgian–Congolese hostilities, and plunge the former Belgian colony into chaos.

Prime minister

Independence

Independence Day and the three days that followed it were declared a national holiday. The Congolese were preoccupied by the festivities, which were conducted in relative peace. Meanwhile, Lumumba's office was overtaken by a flurry of activity. A diverse group of individuals, Congolese and European, some friends and relatives, hurried about their work. Some undertook specific missions on his behalf, sometimes without direct permission. Numerous Congolese citizens showed up at the office at whim for various reasons. Lumumba, for his part, was mostly preoccupied with a lengthy itinerary of receptions and ceremonies. On 3 July Lumumba declared a general amnesty for prisoners, but it was never implemented. The following morning he convened the Council of Ministers to discuss the unrest among the troops of the Force Publique. Many soldiers hoped that independence would result in immediate promotions and material gains, but were disappointed by Lumumba's slow pace of reform. The rank-and-file felt that the Congolese political class—particularly ministers in the new government—were enriching themselves while failing to improve the troops' situation. Many of the soldiers were also fatigued from maintaining order during the elections and participating in independence celebrations. The ministers decided to establish four committees to study, respectively, the reorganisation of the administration, the judiciary, and the army, and the enacting of a new statute for state employees. All were to devote special attention to ending racial discrimination. Parliament assembled for the first time since independence and took its first official legislative action by voting to increase the salaries of its members to FC 500,000. Lumumba, fearing the repercussions the raise would have on the budget, was among the few to object, dubbing it a "ruinous folly".Outbreak of the Congo Crisis

On the morning of 5 July 1960, General

On the morning of 5 July 1960, General Émile Janssens

Émile Robert Alphonse Hippolyte Janssens (15 June 1902 – 4 December 1989) was a Belgian military officer and colonial official, best known for his command of the ''Force Publique'' at the start of the Congo Crisis. He described himself as the ...

, commander of the Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of ...

, in response to increasing excitement among the Congolese ranks, summoned all troops on duty at Camp Léopold II. He demanded that the army maintain its discipline and wrote "before independence = after independence" on a blackboard for emphasis. That evening the Congolese sacked the canteen in protest of Janssens. He alerted the reserve garrison of Camp Hardy, 95 miles away in Thysville

Mbanza-Ngungu, formerly known as Thysville or Thysstad, named after Albert Thys, is a city and territory in Kongo Central Province in the western part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, lying on a short branch off the Matadi-Kinshasa Railway. I ...

. The officers tried to organise a convoy to send to Camp Léopold II to restore order, but the men mutinied and seized the armoury. The crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

which followed came to dominate the tenure of the Lumumba government. The next day Lumumba dismissed Janssens and promoted all Congolese soldiers one grade, but mutinies spread out into the Lower Congo. Although the trouble was highly localised, the country seemed to be overrun by gangs of soldiers and looters. The media reported that Europeans were fleeing the country.Larry Devlin, ''Chief of Station Congo'', 2007, Public Affairs, In response, Lumumba announced over the radio, "Thoroughgoing reforms are planned in all sectors. My government will make every possible effort to see that our country has a different face in a few months, a few weeks." In spite of government efforts, the mutinies continued. Mutineers in Leopoldville and Thysville surrendered only upon the personal intervention of Lumumba and President Kasa-Vubu.

On 8 July, Lumumba renamed the Force Publique as the (ANC). He Africanised the force by appointing Sergeant Major Victor Lundula

Victor Richard Lundula or Lundula Okoko Ta Mongo was a Congolese politician and soldier who served as the first Commander-in-Chief of the Armée Nationale Congolaise.

He was a civilian who had been a medical orderly in the Force Publique during t ...

as general and commander-in-chief, and chose junior minister and former soldier Joseph Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

as colonel and Army chief of staff. These promotions were made in spite of Lundula's inexperience and rumours about Mobutu's ties to Belgian and US intelligence services. All European officers in the army were replaced with Africans, with a few retained as advisers. By the next day the mutinies had spread throughout the entire country. Five Europeans, including the Italian vice-consul, were ambushed and killed by machine gun fire in Élisabethville

Lubumbashi (former names: (French language, French), (Dutch language, Dutch)) is the second-largest city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, located in the country's southeasternmost part, along the border with Zambia. The capital and pr ...

, and nearly the entire European population of Luluabourg barricaded itself in an office building for safety. An estimated two dozen Europeans were murdered in the mutiny. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu embarked on a tour across the country to promote peace and appoint new army commanders. Belgium intervened on 10 July, dispatching 6,000 troops to the Congo, ostensibly to protect its citizens from the violence. Most Europeans went to Katanga Province

Katanga was one of the four large provinces created in the Belgian Congo in 1914.

It was one of the eleven provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1966 and 2015, when it was split into the Tanganyika Province, Tanganyika, Hau ...

, which possessed much of the Congo's natural resources. Though personally angered, Lumumba condoned the action on 11 July, provided that the Belgian forces acted only to protect their citizens, followed the direction of the Congolese armed forces, and ceased their activities once order was restored.

The same day the Belgian Navy bombarded Matadi

Matadi is the chief sea port of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the capital of the Kongo Central province, adjacent to the border with Angola. It had a population of 245,862 (2004). Matadi is situated on the left bank of the Congo River, ...

after it had evacuated its citizens, killing 19 Congolese civilians. This greatly inflamed tensions, leading to renewed Congolese attacks on Europeans. Shortly thereafter Belgian forces moved to occupy cities throughout the country, including the capital, where they clashed with Congolese soldiers. On the whole, the Belgian intervention made the situation worse for the armed forces. The State of Katanga

The State of Katanga; sw, Inchi Ya Katanga) also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local ''Co ...

declared independence under regional premier Moïse Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe (sometimes written Tshombé) (10 November 1919 – 29 June 1969) was a Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of Katanga from 1960 to 1963 and as prime minister of the Re ...

on 11 July, with support from the Belgian government and mining companies such as Union Minière. Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu were denied use of Élisabethville's airstrip the following day and returned to the capital, only to be accosted by fleeing Belgians. They sent a protest of the Belgian deployment to the United Nations, requesting that they withdraw and be replaced by an international peacekeeping force. The UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 143

United Nations Security Council Resolution 143 was adopted on July 14, 1960. With Congolese requests for assistance in front of him, following the Mutiny of the Force Publique, Secretary-General of the United Nations Dag Hammarskjold had called a ...

, calling for immediate removal of Belgian forces and establishment of the United Nations Operation in the Congo

The United Nations Operation in the Congo (french: Opération des Nations Unies au Congo, abbreviated to ONUC) was a United Nations peacekeeping force deployed in the Republic of the Congo in 1960 in response to the Congo Crisis. ONUC was the ...

(ONUC). Despite the arrival of UN troops, unrest continued. Lumumba requested UN troops to suppress the rebellion in Katanga, but the UN forces were not authorised to do so under their mandate. On 14 July Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu broke off diplomatic relations with Belgium. Frustrated at dealing with the West, they sent a telegram to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, requesting that he closely monitor the situation in the Congo.

Visit to the United States

Lumumba decided to travel to New York City in order to personally express the position of his government to the United Nations. Shortly before his departure, he announced that he had signed an economic agreement with a U.S. businessman who had created the Congo International Management Corporation (CIMCO). According to the contract (which had yet to be ratified by parliament), CIMCO was to form a

Lumumba decided to travel to New York City in order to personally express the position of his government to the United Nations. Shortly before his departure, he announced that he had signed an economic agreement with a U.S. businessman who had created the Congo International Management Corporation (CIMCO). According to the contract (which had yet to be ratified by parliament), CIMCO was to form a development corporation

Development corporations or development firms are organizations established by governments in several countries for the purpose of urban development. They often are responsible for the development of new suburban areas or the redevelopment of exi ...

to invest in and manage certain sectors of the economy. He also declared his approval of the second security council resolution, adding that " ovietaid was no longer necessary" and announced his intention to seek technical assistance from the United States. On 22 July Lumumba left the Congo for New York City. He and his entourage reached the United States two days later after brief stops in Accra and London. There they rendezvoused with his UN delegation at the Barclay Hotel

The Barclay Hotel was located at 237 S. 18th St. in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on Rittenhouse Square. Opened in October 1929, it was, at one time, the most famous hotel in the city, and was owned by the well-known developer John McShain. After a l ...

to prepare for meetings with UN officials. Lumumba was focused on discussing the withdrawal of Belgian troops and various options for technical assistance with Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

.

African diplomats were keen that the meetings would be successful; they convinced Lumumba to wait until the Congo was more stable before reaching any more major economic agreements (such as the CIMCO arrangement). Lumumba saw Hammarskjöld and other staff of the UN Secretariat

The United Nations Secretariat (french: link=no, Secrétariat des Nations unies) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), The secretariat is the UN's executive arm. The secretariat has an important role in setting the a ...

over three days on 24, 25, and 26 July. Though Lumumba and Hammarskjöld were restrained towards one another, their discussions went smoothly. In a press conference, Lumumba reaffirmed his government's commitment to "positive neutralism". On 27 July, Lumumba went to Washington, D.C., the United States capital. He met with the US Secretary of State and appealed for financial and technical assistance. The US government informed Lumumba that they would offer aid only through the UN. The following day he received a telegram from Gizenga detailing a clash at Kolwezi

Kolwezi or Kolwesi is the capital city of Lualaba Province in the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, west of Likasi. It is home to an airport and a railway to Lubumbashi. Just outside of Kolwezi there is the static inverter plant of ...

between Belgian and Congolese forces. Lumumba felt that the UN was hampering his attempts to expel the Belgian troops and defeat the Katangan rebels. On 29 July, Lumumba went to Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, the capital of Canada, to request help. The Canadians rebuffed a request for technicians and said that they would channel their assistance through the UN. Frustrated, Lumumba met with the Soviet ambassador in Ottawa and discussed a donation of military equipment. When he returned to New York the following evening, he was restrained towards the UN. The United States government's attitude had become more negative, due to reports of the rapes and violence committed by ANC soldiers, and scrutiny from Belgium. The latter was chagrined that Lumumba had received a high-level reception in Washington. The Belgian government regarded Lumumba as communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, anti-white, and anti-Western. Given its experience in the Congo, many other Western governments gave credence to the Belgian view.

Frustrated with the UN's apparent inaction towards Katanga as he departed the US, Lumumba decided to delay his return to the Congo. He visited several African states. This was apparently done to put pressure on Hammarskjöld and, failing that, to seek guarantees of bilateral military support to suppress Katanga. Between 2 and 8 August, Lumumba toured Tunisia, Morocco, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, and Togoland

Togoland was a German Empire protectorate in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400 km2 (29,867 sq mi) in size. During the period kno ...

. He was well received in each country and issued joint communiques with their respective heads of state. Guinea and Ghana pledged independent military support, while the others expressed their desire to work through the United Nations to resolve the Katangan secession. In Ghana, Lumumba signed a secret agreement with President Nkrumah providing for a "Union of African States". Centred in Léopoldville, it was to be a federation with a republican government. They agreed to hold a summit of African states in Léopoldville between 25 and 30 August to further discuss the issue. Lumumba returned to the Congo, apparently confident that he could now depend upon African military assistance. He also believed that he could procure African bilateral technical aid, which placed him at odds with Hammarskjöld's goal of funnelling support through ONUC. Lumumba and some ministers were wary of the UN option, as it would supply them with functionaries who would not respond directly to their authority.

Attempts at re-consolidation

state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

throughout the Congo. He subsequently issued several orders in an attempt to reassert his dominance on the political scene. The first outlawed the formation of associations without government sanction. A second asserted the government's right to ban publications that produced material likely to bring the administration into disrepute. On 11 August the printed an editorial which declared that the Congolese did not want to fall "under a second kind of slavery". The editor was summarily arrested and four days later publication of the daily ceased. Shortly afterward, the government shut down the Belga and Agence France-Presse

Agence France-Presse (AFP) is a French international news agency headquartered in Paris, France. Founded in 1835 as Havas, it is the world's oldest news agency.

AFP has regional headquarters in Nicosia, Montevideo, Hong Kong and Washington, D.C ...

wire services. The press restrictions garnered a wave of harsh criticism from the Belgian media.

Lumumba decreed the nationalisation of local Belga offices, creating the , as a means of eliminating what he considered a center of biased reporting, as well as creating a service through which the government's platform could be more easily communicated to the public. Another order stipulated that official approval had to be obtained six days in advance of public gatherings. On 16 August Lumumba announced the installation of a for the duration of six months. Throughout August, Lumumba increasingly withdrew from his full cabinet and instead consulted with officials and ministers he trusted, such as Maurice Mpolo

Maurice Mpolo (12 September 1928 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician who served as Minister of Youth and Sports of the Republic of the Congo in 1960. He briefly led the Congolese army that July. He was executed alongside Prime Minister ...

, Joseph Mbuyi

Joseph Mbuyi (12 August 1929 – 1960/1961) was a Congolese politician. He served as the Minister of Middle Classes of the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1960.

Biography ...

, Kashamura, Gizenga, and Antoine Kiwewa. Lumumba's office was in disarray, and few members of his staff did any work. His , Damien Kandolo, was often absent and acted as a spy on behalf of the Belgian government. Lumumba was constantly being delivered rumours from informants and the , encouraging him to grow deeply suspicious of others.

In an attempt to keep him informed, Serge Michel, his press secretary, enlisted the assistance of three Belgian telex

The telex network is a station-to-station switched network of teleprinters similar to a Public switched telephone network, telephone network, using telegraph-grade connecting circuits for two-way text-based messages. Telex was a major method of ...

operators, who supplied him with copies of all outgoing journalistic dispatches. Lumumba immediately ordered Congolese troops to put down the rebellion in secessionist South Kasai

South Kasai (french: Sud-Kasaï) was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised Secession, secessionist state within the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (the modern-day Democratic Republi ...

, which was home to strategic rail links necessary for a campaign in Katanga. The operation was successful, but the conflict soon devolved into ethnic violence. The army became involved in massacres of Luba

Luba may refer to:

Geography

*Kingdom of Luba, a pre-colonial Central African empire

*Ľubá, a village and municipality in the Nitra region of south-west Slovakia

*Luba, Abra, a municipality in the Philippines

*Luba, Equatorial Guinea, a town o ...

civilians. The people and politicians of South Kasai held Lumumba personally responsible for the actions of the army. Kasa-Vubu publicly announced that only a federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

government could bring peace and stability to the Congo. This broke his tenuous political alliance with Lumumba and tilted the political favour in the country away from Lumumba's unitary state

A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create (or abolish) administrative divisions (sub-national units). Such units exercise only th ...

. Ethnic tensions rose against him (especially around Leopoldville), and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, still powerful in the country, openly criticised his government. Even with South Kasai subdued, the Congo lacked the necessary strength to retake Katanga. Lumumba had summoned an African conference in Leopoldville from 25–31 August, but no foreign heads of state appeared and no country pledged military support. Lumumba demanded once again that UN peacekeeping soldiers assist in suppressing the revolt, threatening to bring in Soviet troops if they refused. The UN subsequently denied Lumumba the use of its forces. The possibility of a direct Soviet intervention was thought increasingly likely.

Dismissal

Kasa-Vubu's revocation order

President Kasa-Vubu began fearing a Lumumbist coup d'état would take place. On the evening of 5 September, Kasa-Vubu announced over radio that he had dismissed Lumumba and six of his ministers from the government for the massacres in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets in the Congo. Upon hearing the broadcast, Lumumba went to the national radio station, which was under UN guard. Though they had been ordered to bar Lumumba's entry, the UN troops allowed the prime minister in, as they had no specific instructions to use force against him. Lumumba denounced his dismissal over the radio as illegitimate, and in turn labelled Kasa-Vubu a traitor and declared him deposed. Kasa-Vubu had not declared the approval of any responsible ministers of his decision, making his action legally invalid. Lumumba noted this in a letter to Hammarskjöld and a radio broadcast at 05:30 on 6 September. Later that day Kasa-Vubu managed to secure the countersignatures to his order of Albert Delvaux, Minister Resident in Belgium, and

President Kasa-Vubu began fearing a Lumumbist coup d'état would take place. On the evening of 5 September, Kasa-Vubu announced over radio that he had dismissed Lumumba and six of his ministers from the government for the massacres in South Kasai and for involving the Soviets in the Congo. Upon hearing the broadcast, Lumumba went to the national radio station, which was under UN guard. Though they had been ordered to bar Lumumba's entry, the UN troops allowed the prime minister in, as they had no specific instructions to use force against him. Lumumba denounced his dismissal over the radio as illegitimate, and in turn labelled Kasa-Vubu a traitor and declared him deposed. Kasa-Vubu had not declared the approval of any responsible ministers of his decision, making his action legally invalid. Lumumba noted this in a letter to Hammarskjöld and a radio broadcast at 05:30 on 6 September. Later that day Kasa-Vubu managed to secure the countersignatures to his order of Albert Delvaux, Minister Resident in Belgium, and Justin Marie Bomboko

Justin-Marie Bomboko Lokumba Is Elenge (22 September 1928 – 10 April 2014), was a Congolese politician and statesman. He was the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Congo. He served as leader of the Congolese government as chairman of the Coll ...

, Minister of Foreign Affairs. With them, he announced again his dismissal of Lumumba and six other ministers at 16:00 over Brazzaville radio.

Lumumba and the ministers who remained loyal to him ordered the arrest of Delvaux and Bomboko for countersigning the dismissal order. The latter sought refuge in the presidential palace (which was guarded by UN peacekeepers), but early in the morning on 7 September, the former was detained and confined in the Prime Minister's residence. Meanwhile, the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

convened to discuss Kasa-Vubu's dismissal order and hear Lumumba's reply. Delvaux made an unexpected appearance and took to the dais to denounce his arrest and declare his resignation from the government. He was enthusiastically applauded by the opposition. Lumumba then delivered his speech. Instead of directly attacking Kasa-Vubu ''ad hominem'', Lumumba accused obstructionist politicians and ABAKO of using the presidency as a front for disguising their activities. He noted that Kasa-Vubu had never before offered any criticism of the government and portrayed their relationship as one of cooperation. He lambasted Delvaux and Minister of Finance Pascal Nkayi

Pascal Nkayi (18 September 1911 – ?) was a Congolese politician. He served as Minister of Finance of Republic of the Congo from June until September 1960.

Biography

Pascal Nkayi was born on 18 September 1911 in Palabala, Belgian Congo. He att ...

for their role in the UN Geneva negotiations and for their failure to consult the rest of the government. Lumumba followed his arguments with an analysis of the ''Loi Fondemental'' and finished by asking Parliament to assemble a "commission of sages" to examine the Congo's troubles.