Ludwig Ross on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

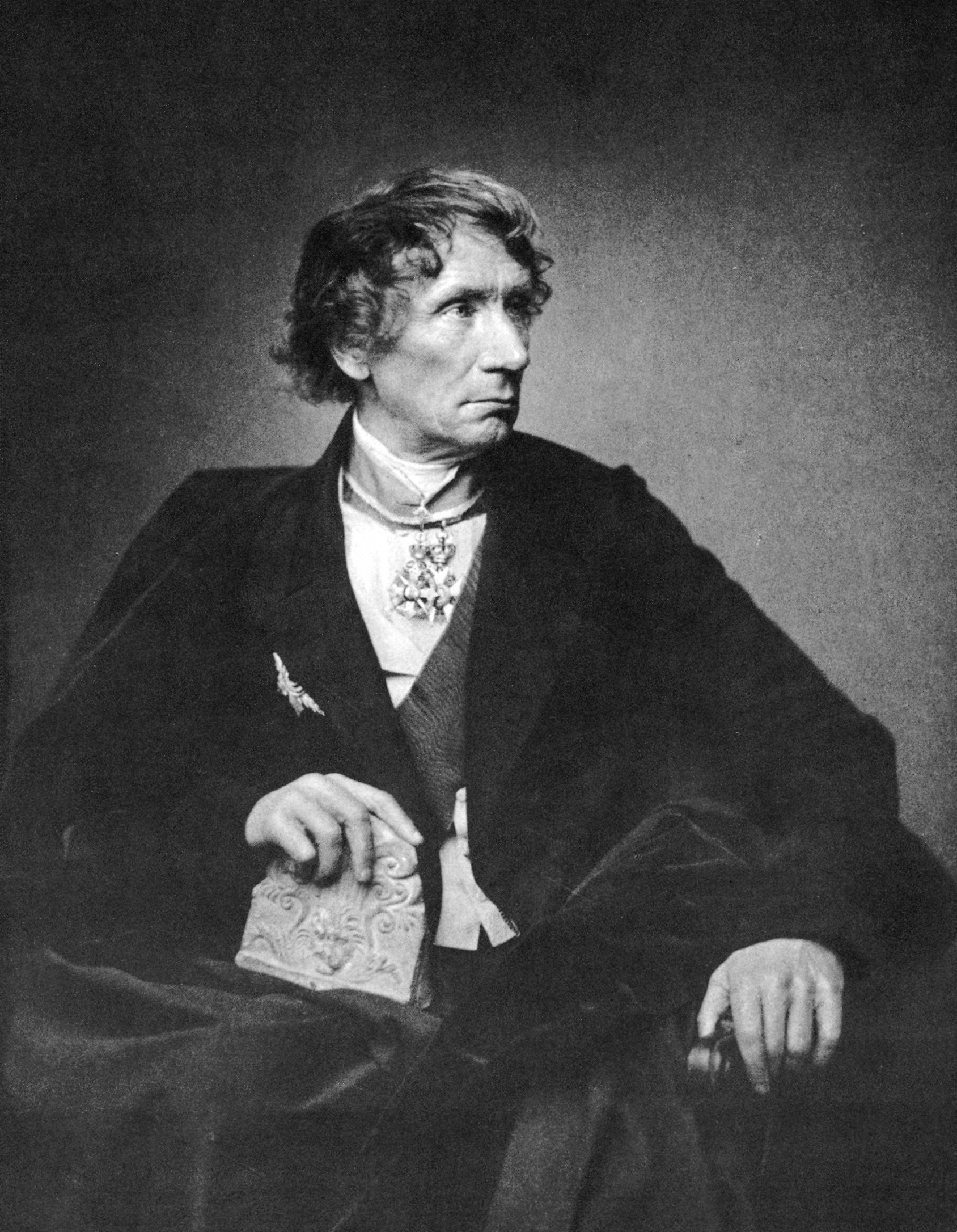

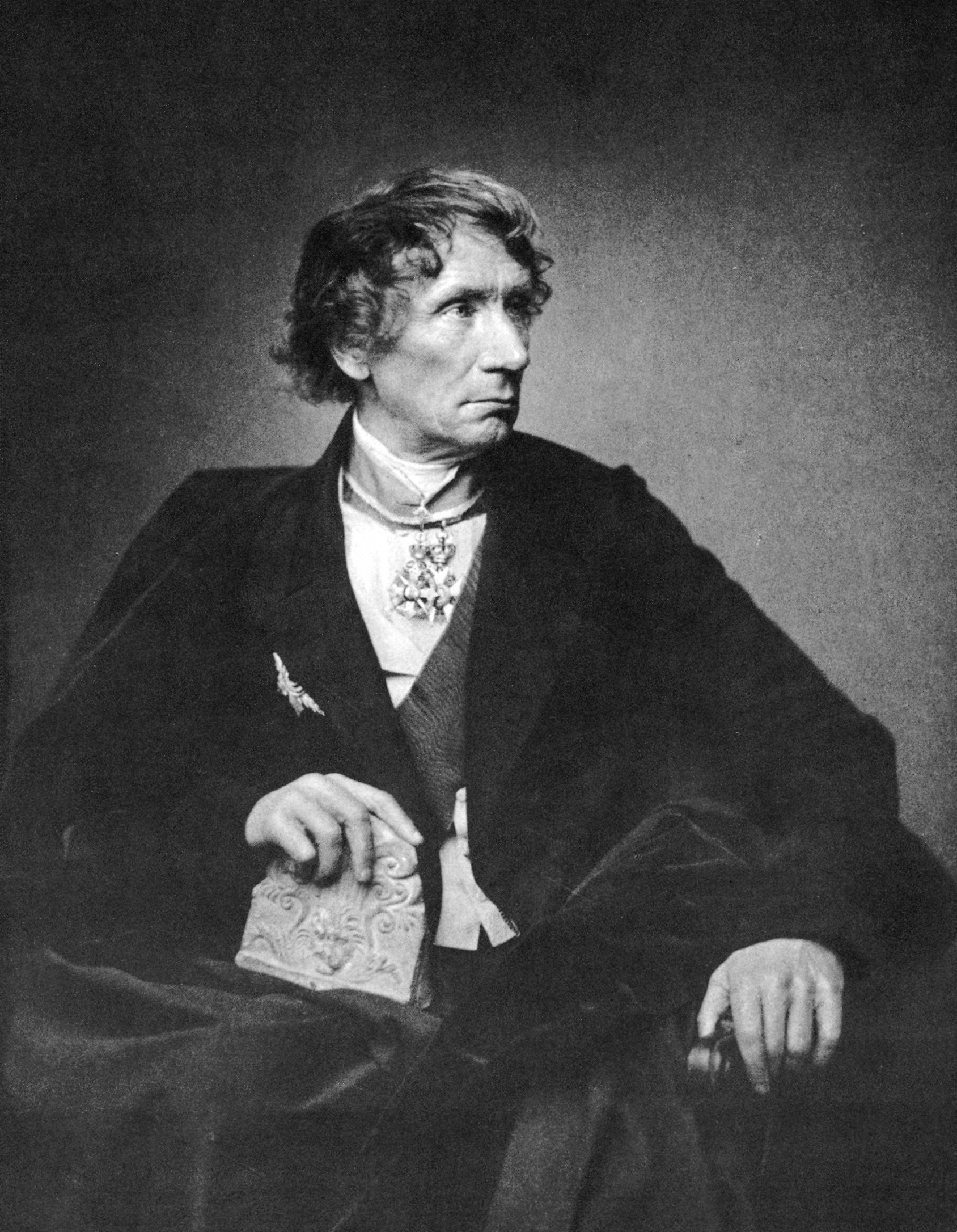

Ludwig Ross (22 July 1806,

Ross was born in 1806 in Bornhöved in

Ross was born in 1806 in Bornhöved in

Ross arrived in Greece on 26 July 1832, two weeks before the

Ross arrived in Greece on 26 July 1832, two weeks before the  Like many German archaeologists and scholars, Ross found favour with the young king, and Ross would later accompany Otto on archaeological travels around Greece.

In 1833, Ross was appointed as 'sub-ephor' ( el, ὑποέφορος) of antiquities for the

Like many German archaeologists and scholars, Ross found favour with the young king, and Ross would later accompany Otto on archaeological travels around Greece.

In 1833, Ross was appointed as 'sub-ephor' ( el, ὑποέφορος) of antiquities for the

In July 1834, the architect

In July 1834, the architect

Ross' work on the Acropolis began in January 1835, and has been described as the first systematic excavation of the site. Initially, the Acropolis was still occupied by Bavarian forces, in defiance of the royal decree of the previous August: through the support of , a member of Otto's regency council, Ross was able to arrange the soldiers' departure in February and for guards for the archaeological works to be posted in their stead. Klenze set out a series of principles for the restoration, which included the removal of any structures deemed to be of no 'archaeological, constructional or pictureseque' () interest, reconstruction using fallen parts of the original monuments (

Ross' work on the Acropolis began in January 1835, and has been described as the first systematic excavation of the site. Initially, the Acropolis was still occupied by Bavarian forces, in defiance of the royal decree of the previous August: through the support of , a member of Otto's regency council, Ross was able to arrange the soldiers' departure in February and for guards for the archaeological works to be posted in their stead. Klenze set out a series of principles for the restoration, which included the removal of any structures deemed to be of no 'archaeological, constructional or pictureseque' () interest, reconstruction using fallen parts of the original monuments ( The initial works of 1835 focused on the

The initial works of 1835 focused on the  At the Tower of Athena Nike, Ross' demolition of the bastion revealed the '' disiecta membra'' of the former temple, which has been described by Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as 'one of the greatest moments in the history of the Acropolis in this period'. Ross and his collaborators carried out the reconstruction of the temple between December 1835 and May 1836, building on top of the surviving

At the Tower of Athena Nike, Ross' demolition of the bastion revealed the '' disiecta membra'' of the former temple, which has been described by Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as 'one of the greatest moments in the history of the Acropolis in this period'. Ross and his collaborators carried out the reconstruction of the temple between December 1835 and May 1836, building on top of the surviving

The regent Armansperg promised to restore Ross' status as Ephor General, but failed to do so, cooling relations between himself and Ross. When Otto came of age in 1837, however, he founded the Othonian University of Athens (now the

The regent Armansperg promised to restore Ross' status as Ephor General, but failed to do so, cooling relations between himself and Ross. When Otto came of age in 1837, however, he founded the Othonian University of Athens (now the  Ross was elected as a member of the university's nine-member senate, where he supported the introduction of German-style assistant professors. In 1834, he published the first volume of ''Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae'' ( en, Unpublished Greek Inscriptions), a compendium and edition of the Greek inscriptions he had discovered and the first epigraphical volume to be published in Greece. He was criticised on its publication for writing in Latin rather than Greek, which has been suggested as part of the reason why he delayed the publication of the second volume, which had been expected in 1835, until 1842. In 1839, he published the results of his excavations at the Temple of Athena Nike, in a volume illustrated by Hansen and Schaubert.

Ross was elected as a member of the university's nine-member senate, where he supported the introduction of German-style assistant professors. In 1834, he published the first volume of ''Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae'' ( en, Unpublished Greek Inscriptions), a compendium and edition of the Greek inscriptions he had discovered and the first epigraphical volume to be published in Greece. He was criticised on its publication for writing in Latin rather than Greek, which has been suggested as part of the reason why he delayed the publication of the second volume, which had been expected in 1835, until 1842. In 1839, he published the results of his excavations at the Temple of Athena Nike, in a volume illustrated by Hansen and Schaubert. In 1841, Ross published his ''Handbook of the Archaeology of the Arts'' (), written in

In 1841, Ross published his ''Handbook of the Archaeology of the Arts'' (), written in

Through the support of Humboldt, Ross was appointed to the professorship of archaeology at the

Through the support of Humboldt, Ross was appointed to the professorship of archaeology at the

In the spring of 1847, Ross married Emma Schwetschke, daughter of the publisher . Shortly thereafter, he developed the beginnings of a health condition, which gradually reduced his strength and mobility and caused him increasing pain and discomfort. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to treat his condition with spa cures.

Ross died by

In the spring of 1847, Ross married Emma Schwetschke, daughter of the publisher . Shortly thereafter, he developed the beginnings of a health condition, which gradually reduced his strength and mobility and caused him increasing pain and discomfort. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to treat his condition with spa cures.

Ross died by

Bornhöved

Bornhöved () is a municipality in the '' Kreis'' (district) of Segeberg in Schleswig-Holstein, north Germany. It is situated some 16 km east of Neumünster.

Bornhöved is part of the ''Amt'' (municipal confederation) of Bornhöved

Bornh ...

– 6 August 1859, Halle an der Saale

Halle (Saale), or simply Halle (; from the 15th to the 17th century: ''Hall in Sachsen''; until the beginning of the 20th century: ''Halle an der Saale'' ; from 1965 to 1995: ''Halle/Saale'') is the largest city of the German state of Saxony-Anh ...

) was a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

classical archaeologist

Classical archaeology is the archaeological investigation of the Mediterranean civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Nineteenth-century archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann were drawn to study the societies they had read about i ...

. He is chiefly remembered for the rediscovery and reconstruction of the Temple of Athena Nike

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

in 1835–1836, and for his other excavation and conservation work on the Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens is an ancient citadel located on a rocky outcrop above the city of Athens and contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historical significance, the most famous being the Parthenon. Th ...

. He was also a significant figure in the early years of archaeology in the independent Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label=Greek, Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, where ...

, serving as Ephor General of Antiquities between 1834 and 1836.

As a representative of the ''Bavarocracy —'' the dominance by northern Europeans, especially Bavarians, of Greek government and institutions under the Bavarian-born King Otto ''—'' Ross attracted the enmity of the native Greek archaeological establishment. He was forced to resign as Ephor General over his delivery of the Athenian 'naval records', a series of inscriptions first unearthed in 1834, to the German August Böckh

August Böckh or Boeckh (; 24 November 1785 – 3 August 1867) was a German classical scholar and antiquarian.

Life

He was born in Karlsruhe, and educated at the local gymnasium; in 1803 he left for the University of Halle, where he studied th ...

for publication. He was subsequently appointed as the first professor of archaeology at the University of Athens, but once again forced to resign by the nativist 3 September 1843 Revolution

The 3 September 1843 Revolution ( el, Επανάσταση της 3ης Σεπτεμβρίου 1843; N.S. 15 September), was an uprising by the Hellenic Army in Athens, supported by large sections of the people, against the autocratic rule of K ...

, which removed non-Greeks from public service in the country. He spent his final years as a professor in Halle, where he argued unsuccessfully against the reconstruction of the Indo-European language family

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

, believing the Latin language to be a direct descendant of Greek.

Ross is credited with creating the foundations for the science of archaeology in independent Greece, and for establishing a systematic approach to excavation and conservation in the earliest days of the country's formal archaeological practice. His publications, particularly in epigraphy, were widely used by contemporary scholars, and his role at Athens in training the first generation of natively-trained Greek archaeologists was particularly significant for producing Panagiotis Efstratiadis

Panagiotis Efstratiadis or Eustratiades ( el, Παναγιώτης Ευστρατιάδης) (1815 – ) was a Greek people, Greek Archaeology, archaeologist. He served as Ephor (archaeology), Ephor General of Antiquities, the head of the Gre ...

, one of the foremost Greek epigraphers of the 19th century and a successor of Ross as Ephor General. Early life

Ross was born in 1806 in Bornhöved in

Ross was born in 1806 in Bornhöved in Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

, then ruled by the Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm ( da, Danmarks Rige; fo, Danmarkar Ríki; kl, Danmarkip Naalagaaffik), officially the Kingdom of Denmark (; ; ), is a sovereign state located in Northern Europe and Northern North America. It consists of Denmark, metropolitan ...

. His paternal grandfather, a doctor, had moved from northern Scotland to Hamburg around 1750. His father, Colin Ross, married Juliane Auguste Remin. When Ludwig was four years old, his father moved to the Gut Altekoppel estate in Bornhöved, which he managed and later acquired. Their five sons and three daughters included Ludwig's younger brother, the painter Karl Ross

Karl Ross (15 November 1816–5 February 1858) (also known as Charles) was a Germans, German painter. He is most known for his paintings of Classical antiquity, Classical Landscape painting, landscapes.

Biography

Ross was born in Ruhwinkel, Ho ...

. Ludwig, like his brother Karl, campaigned for the Duchy's independence from Denmark.

Ross grew up in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

and Plön

Plön (; Holsatian: ''Plöön'') is the district seat of the Plön district in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, and has about 8,700 inhabitants. It lies right on the shores of Schleswig-Holstein's biggest lake, the Great Plön Lake, as well as on ...

. In 1825, he went to the Christian-Albrechts-Universität

Kiel University, officially the Christian-Albrecht University of Kiel, (german: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, abbreviated CAU, known informally as Christiana Albertina) is a university in the city of Kiel, Germany. It was founded in ...

in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

to study classical philology

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

. His teachers at Kiel included the theologian August Twesten, the historian Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann

Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann (13 May 1785, Wismar5 December 1860, Bonn) was a German historian and politician.

Biography

He came of an old Hanseatic family of Wismar, then controlled by Sweden. His father, who was burgomaster of the town, int ...

, Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch

Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch (22 November 1790 – 22 July 1861) was a German classical scholar known chiefly for his writings on Homeric epic.

Brother of Karl Immanuel Nitzsch, he was born at Wittenberg. In 1827 he was appointed professor of ancient l ...

and , whose lectures focused largely on Classical literature, including the Greek playwrights Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

, Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

and Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

, as well as philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

studies of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

and Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

. He graduated on 16 May 1829 with a Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

on Aristophanes' ''Wasps

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. T ...

'', supervised by Nitzch, after which he worked briefly as a private tutor in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

. In 1831 he published his first scholarly work, a short history of the Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein.

In 1832, with Nitzch's support, Ross applied for and received a scholarship

A scholarship is a form of financial aid awarded to students for further education. Generally, scholarships are awarded based on a set of criteria such as academic merit, diversity and inclusion, athletic skill, and financial need.

Scholarsh ...

from the King of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe ...

to travel in Greece. His letters of this period to Nitzsch reveal his intention to continue his studies of Aristophanes, and to publish academic work to build his scholarly reputation. After a brief visit to study in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

, he made his way to Greece in 1832, travelling overland to Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

before boarding a Greek ship, the ''Etesia'', for Nafplio

Nafplio ( ell, Ναύπλιο) is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece and it is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important touristic destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the ...

on 11 July.

Archaeological career in Greece (1832-1843)

Ross arrived in Greece on 26 July 1832, two weeks before the

Ross arrived in Greece on 26 July 1832, two weeks before the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

confirmed the appointment of Otto of Bavaria Otto of Bavaria may refer to:

* Otto I, Duke of Swabia and Bavaria (955–982)

* Otto of Nordheim (c. 1020–1083)

* Otto I Wittelsbach, Duke of Bavaria (1117–1183)

* Otto VIII, Count Palatine of Bavaria (before 1180 – 7 March 1209)

* Otto II ...

as King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolishe ...

. He was made deputy curator of antiquities at the Archaeological Museum of Nafplion

The Archaeological Museum of Nafplio is a museum in the town of Nafplio of the Argolis region in Greece. It has exhibits of the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Helladic, Mycenaean, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods from all over southern Argolis ...

, then capital of Greece, in 1832, and was received by the Greek National Assembly

The Greek national assemblies ( el, Εθνοσυνελεύσεις) are representative bodies of the Greek people. During and in the direct aftermath of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832), the name was used for the insurgents' proto-parli ...

in the city on 8 August, presenting them with a lithograph

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

of Otto which he had brought with him from Trieste.

Like many German archaeologists and scholars, Ross found favour with the young king, and Ross would later accompany Otto on archaeological travels around Greece.

In 1833, Ross was appointed as 'sub-ephor' ( el, ὑποέφορος) of antiquities for the

Like many German archaeologists and scholars, Ross found favour with the young king, and Ross would later accompany Otto on archaeological travels around Greece.

In 1833, Ross was appointed as 'sub-ephor' ( el, ὑποέφορος) of antiquities for the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, alongside Kyriakos Pittakis

Kyriakos S. Pittakis or Pittakys ( el, Κυριακός Πιττάκης) (1798–1863) was a Greek archaeologist of the 19th century. He is most notable as the first Greek Ephor-General of Antiquities of Greece, the head of the Greek Archaeo ...

for the rest of mainland Greece and for Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born ...

. The three sub-ephors served under the Bavarian architect Adolf Weissenberg, who had been given overall responsibility as ephor for Greek antiquities.

Ross organised a series of sporting competitions, similar to the ancient Olympic and Isthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year ...

, on 4 March 1833, and encouraged the Greek government, through the Royal Family, to issue an 1837 decree re-establishing the Olympic Games in Pyrgos.

Work on the Acropolis of Athens (1834-1836)

Leo von Klenze

Leo von Klenze (Franz Karl Leopold von Klenze; 29 February 1784, Buchladen (Bockelah / Bocla) near Schladen – 26 January 1864, Munich) was a German neoclassicist architect, painter and writer. Court architect of Bavarian King Ludwig I, Leo ...

arrived in Athens to advise Otto on the development of the city, and advised that the Acropolis, which was at that point a military fortress occupied by Bavarian troops, should be demilitarised and designated as an archaeological site. A royal decree to this effect was issued on 18 August. Weissenberg's reputed lack of interest in antiquities, as well as his political opposition to the regent Josef Ludwig von Armansperg

Josef Ludwig, Graf von Armansperg ( el, Κόμης Ιωσήφ Λουδοβίκος Άρμανσπεργκ; 28 February 1787 – 3 April 1853) served as the Interior and Finance Minister (1826–1828) and Foreign and Finance Minister (1828–1831) u ...

, led to his dismissal from office in September. On Klenze's personal recommendation, Ross was given the title of 'Ephor General' () in charge of all archaeology in Greece on 10 September, which included direct responsibility for the Acropolis. Ross' control of the Acropolis passed over Pittakis, who had been serving since 1832 as the unpaid 'custodian of the antiquities in Athens' ( el, ἐπιστάτης τῶν ἐν Ἀθήναις ἀρχαιοτήτων), and into whose sub-ephorate Athens fell by the arrangement of 1833. In Athens, Ross worked mostly alongside architects from northern Europe, particularly the Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

Eduard Schaubert

Gustav Eduard Schaubert ( el, Εδουάρδος Σάουμπερτ, translit=Edouárdos Sáoumpert) 27 July 1804, Breslau, Prussia – 30 March 1860, Breslau) was a Prussian architect, who made a major contribution to the re-planning of Athens ...

, the Danish Christian Hansen (who replaced the Greek architect Stamatios Kleanthis

Stamatios or Stamatis Kleanthis ( el, Σταμάτιος or ; 1802–1862) was a Greek architect.

Biography

Stamatios Kleanthis was born to a Macedonian Greek family in the town of Velventos in Kozani, Macedonia in 1802. As a youth he moved t ...

on the latter's resignation, shortly after work began) and the Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

native Eduard Laurent. The dominance of non-Greek scholars in the excavation and conservation of Greek monuments provoked resentment from the native Greek intelligentsia, and tensions between Pittakis and Ross.

Tension existed between the Greek state's aim of conserving Athens' ancient monuments, its existing role as a military fortification, and the needs of the expanding city of Athens. Klenze had envisaged that the area around the site would be kept clear of buildings, creating an 'archaeological park': however, the pressure on housing created by a growing population, as well as the generally chaotic nature of city government in this period, made this aim impossible. In 1834, Ross was asked to compose a list of sites around the Acropolis that were most in need of protection, so that they could be acquired by the state: working with Pittakis, he identified thirteen, but was initially forced to reduce the list to five, before the proposed initiative was abandoned altogether. In 1835, both in order to fund the restoration works and to control the number of visitors, the Acropolis became the first archaeological site in the world to charge an entrance fee. Ross' work was seen as part of the broader project of building Athens as the capital of the new Greek state: in 1835, Ross became a member, and subsequently the chair, of the building commission responsible for the planning of the city.

Ross' work on the Acropolis began in January 1835, and has been described as the first systematic excavation of the site. Initially, the Acropolis was still occupied by Bavarian forces, in defiance of the royal decree of the previous August: through the support of , a member of Otto's regency council, Ross was able to arrange the soldiers' departure in February and for guards for the archaeological works to be posted in their stead. Klenze set out a series of principles for the restoration, which included the removal of any structures deemed to be of no 'archaeological, constructional or pictureseque' () interest, reconstruction using fallen parts of the original monuments (

Ross' work on the Acropolis began in January 1835, and has been described as the first systematic excavation of the site. Initially, the Acropolis was still occupied by Bavarian forces, in defiance of the royal decree of the previous August: through the support of , a member of Otto's regency council, Ross was able to arrange the soldiers' departure in February and for guards for the archaeological works to be posted in their stead. Klenze set out a series of principles for the restoration, which included the removal of any structures deemed to be of no 'archaeological, constructional or pictureseque' () interest, reconstruction using fallen parts of the original monuments (anastylosis

Anastylosis (from the Ancient Greek: ; , = "again", and = "to erect stela or building) is an archaeological term for a reconstruction technique whereby a ruined building or monument is restored using the original architectural elements to t ...

) as far as possible, and the placement of fragments deemed of aesthetic interest (but not sculptures, which were to be displayed in the mosque and Theseion) in 'picturesque piles' between the monuments. In the spring of 1835, Ross and Schaubert carried out rebuilding and restoration of the Theseion to make it suitable for its new role as a museum, which included the demolition of the apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an ''exedra''. In ...

constructed during the monument's use as a Christian church.

The initial works of 1835 focused on the

The initial works of 1835 focused on the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

and on the western approach to the Acropolis, around the Pedestal of Agrippa

The Pedestal, now known as the Agrippa Pedestal located west of the Propylaea of Athens and the same height as the Temple of Athena Nike to the south, was built in honor of Eumenes II of Pergamon in 178 BC to commemorate his victory in the Panath ...

and what was then known as the Tower of Athena Nike: the former parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). Whe ...

of the Temple of Athena Nike, most of which had been dismantled during the Venetian siege of 1687 and whose surviving parapet was serving as a gun emplacement. Ross hired eighty workmen, split between the two sites. The first tasks were to demolish the modern bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

near the Tower of Athena Nike and the mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

inside the Parthenon, which Ross justified in his letters to Klenze as necessary to prevent the re-militarisation of the Acropolis, both structures having previously been used by the military garrison. A lack of heavy lifting equipment limited Ross' progress in the Parthenon, making the full demolition of the mosque impossible, but the excavations revealed the first evidence for the Older Parthenon

The Older Parthenon or Pre‐Parthenon, as it is frequently referred to, constitutes the first endeavour to build a sanctuary for Athena Parthenos on the site of the present Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens. It was begun shortly after the bat ...

which predated the Periclean temple, as well as numerous fragments and items of statuary from the Classical temple.

At the Tower of Athena Nike, Ross' demolition of the bastion revealed the '' disiecta membra'' of the former temple, which has been described by Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as 'one of the greatest moments in the history of the Acropolis in this period'. Ross and his collaborators carried out the reconstruction of the temple between December 1835 and May 1836, building on top of the surviving

At the Tower of Athena Nike, Ross' demolition of the bastion revealed the '' disiecta membra'' of the former temple, which has been described by Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as 'one of the greatest moments in the history of the Acropolis in this period'. Ross and his collaborators carried out the reconstruction of the temple between December 1835 and May 1836, building on top of the surviving crepidoma

Crepidoma is an architectural term for part of the structure of ancient Greek buildings. The crepidoma is the multilevel platform on which the superstructure of the building is erected. The crepidoma usually has three levels. Each level typica ...

and column bases with the excavated fragments of the temple, which were placed with little regard for their individual situation, and other remains of nearby monuments, including the Propylaia

In ancient Greek architecture, a propylaea, propylea or propylaia (; Greek: προπύλαια) is a monumental gateway. The prototypical Greek example is the propylaea that serves as the entrance to the Acropolis of Athens. The Greek Revival B ...

. The restoration was hailed at the time as the first full reconstruction of a Classical monument in Greece, but later observers criticised the haste in which the work was undertaken, the incongruity of the use of modern materials where ancient fragments could not be found, and the lack of correspondence between Ross' reconstruction and any plausible original design of the temple. Throughout his excavations on the Acropolis, he published his results in both the academic press and in reports to German newspapers.

At a time when relatively few Greek archaeologists worked outside Athens, Ross organised archaeological collections throughout the Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

, and conducted excavations on Thera

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek language, Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English language, English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast ...

in 1835, unearthing twelve funerary inscriptions, which Ross divided between Thera, the regional museum on Syros

Syros ( el, Σύρος ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and it has 21,507 inhabitants (2011 census).

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, A ...

(which he had ordered to be established in 1834–1835) and the Central Museum in Athens. He remained closely connected with the Ottonian court, and guided Otto's father Ludwig I of Bavaria

en, Louis Charles Augustus

, image = Joseph Karl Stieler - King Ludwig I in his Coronation Robes - WGA21796.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Joseph Stieler, 1825

, succession=King of Bavaria

, reign =

, coronation ...

and the Hermann, Fürst von Pückler-Muskau

Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau (; born as Count Pückler, from 1822 Prince; 30 October 1785 – 4 February 1871) was a German nobleman, renowned as an accomplished artist in landscape gardening, as well as the author of a ...

during their respective visits to Greece. He also corresponded closely with the British antiquarian William Martin Leake

William Martin Leake (14 January 17776 January 1860) was an English military man, topographer, diplomat, antiquarian, writer, and Fellow of the Royal Society. He served in the British military, spending much of his career in the

Mediterrane ...

, who had travelled extensively through Greece in the early 19th century. Leake's final account of his travels, ''Travels in Northern Greece'', was published in 1835 and became the period's standard introduction to the archaeology and topography of Greece.

'Naval Records Affair' and resignation as Ephor General

Ross had a long-running feud with Kyriakos Pittakis, one of the first native Greeks employed by theGreek Archaeological Service

The Greek Archaeological Service ( el, Αρχαιολογική Υπηρεσία) is a state service, under the auspices of the Greek Ministry of Culture, responsible for the oversight of all archaeological excavations, museums and the country's ar ...

, which reflected wider tensions between native Greek archaeologists and the mostly Bavarian scholars who, on the invitation of King Otto, dominated Greek archaeology in the first years of the independent state. In 1834 and 1835, excavations in the Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

uncovered a series of inscriptions known as the 'Naval Records', which gave information on the administration and financing of the Athenian navy between the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. Ross studied the inscriptions and sent sketches to August Böckh for the ''Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum

The ''Inscriptiones Graecae'' (IG), Latin for ''Greek inscriptions'', is an academic project originally begun by the Prussian Academy of Science, and today continued by its successor organisation, the . Its aim is to collect and publish all known ...

'', despite having not yet received approval to publish them. The Greek authorities asserted that Ross' actions were illegal: Pittakis attacked Ross in the press, forcing Ross' resignation as Ephor General in 1836. Nikolaos Papazarkadas has argued that Pittakis' opposition to Ross' actions was personal rather than principled, pointing out that Pittakis made no protest against the copying of several thousand Greek inscriptions by French epigraphers from 1843 onwards, a project supported by the Prime Minister, Ioannis Kolettis

Ioannis Kolettis (; died 17 September 1847) was a Greek politician who played a significant role in Greek affairs from the Greek War of Independence through the early years of the Greek Kingdom, including as Minister to France and serving twice ...

.

On Ross' resignation, Pittakis was appointed ephor of the 'Central Public Museum for Antiquities', making him the most senior archaeologist employed by the Greek Archaeological Service and its ''de facto'' head. He received the title of Ephor General in 1843.

Professorship at Athens (1837-1843)

The regent Armansperg promised to restore Ross' status as Ephor General, but failed to do so, cooling relations between himself and Ross. When Otto came of age in 1837, however, he founded the Othonian University of Athens (now the

The regent Armansperg promised to restore Ross' status as Ephor General, but failed to do so, cooling relations between himself and Ross. When Otto came of age in 1837, however, he founded the Othonian University of Athens (now the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA; el, Εθνικό και Καποδιστριακό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών, ''Ethnikó ke Kapodistriakó Panepistímio Athinón''), usually referred to simply as the Univers ...

), which was inaugurated on 3 May. Ross was granted the inaugural professorship

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professors ...

of Archaeology, one of the first such chairs in the world. Ross' professorship has generally been attributed to Otto's personal favour towards him: it has even been suggested that the chair was created specifically for him. He was one of seven Germans out of 23 teaching staff, paid 350 drachmae

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

a month.

Ross' first lecture took place on 10 May, on Aristophanes, before an audience of around 30. During his professorship, he lectured widely on Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

and Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

, on the history of Classical Athens

The city of Athens ( grc, Ἀθῆναι, ''Athênai'' .tʰɛ̂ː.nai̯ Modern Greek: Αθήναι, ''Athine'' or, more commonly and in singular, Αθήνα, ''Athina'' .'θi.na during the classical period of ancient Greece (480–323 BC) wa ...

and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, and on the topography of Athens, largely basing his course on inscriptions that he had discovered himself. In the 1840–1841 academic year, Ross offered a course in Greek epigraphy, marking the first time that epigraphy had been taught as a distinct discipline in Greece. His students included the epigraphist and future Ephor General Panagiotis Efstratiadis

Panagiotis Efstratiadis or Eustratiades ( el, Παναγιώτης Ευστρατιάδης) (1815 – ) was a Greek people, Greek Archaeology, archaeologist. He served as Ephor (archaeology), Ephor General of Antiquities, the head of the Gre ...

.

Ross was elected as a member of the university's nine-member senate, where he supported the introduction of German-style assistant professors. In 1834, he published the first volume of ''Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae'' ( en, Unpublished Greek Inscriptions), a compendium and edition of the Greek inscriptions he had discovered and the first epigraphical volume to be published in Greece. He was criticised on its publication for writing in Latin rather than Greek, which has been suggested as part of the reason why he delayed the publication of the second volume, which had been expected in 1835, until 1842. In 1839, he published the results of his excavations at the Temple of Athena Nike, in a volume illustrated by Hansen and Schaubert.

Ross was elected as a member of the university's nine-member senate, where he supported the introduction of German-style assistant professors. In 1834, he published the first volume of ''Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae'' ( en, Unpublished Greek Inscriptions), a compendium and edition of the Greek inscriptions he had discovered and the first epigraphical volume to be published in Greece. He was criticised on its publication for writing in Latin rather than Greek, which has been suggested as part of the reason why he delayed the publication of the second volume, which had been expected in 1835, until 1842. In 1839, he published the results of his excavations at the Temple of Athena Nike, in a volume illustrated by Hansen and Schaubert. In 1841, Ross published his ''Handbook of the Archaeology of the Arts'' (), written in

In 1841, Ross published his ''Handbook of the Archaeology of the Arts'' (), written in katharevousa

Katharevousa ( el, Καθαρεύουσα, , literally "purifying anguage) is a conservative form of the Modern Greek language conceived in the late 18th century as both a literary language and a compromise between Ancient Greek and the contempor ...

Greek. Olga Palagia

Olga Palagia is Professor of Classical Archaeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and is a leading expert on ancient Greek sculpture. She is known in particular for her work on sculpture in ancient Athens and has edited a ...

has described the ''Handbook'' as both 'a model of the scientific method for its time' and 'a monument to the Greek language'. In the volume, Ross promoted Neoclassicist

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

ideals, by which he argued that art and architecture should adapt and imitate the models of Classical antiquity, placing comparatively little emphasis on historical questions about the development of Greek architecture. Ross also argued for the dependence of Ancient Greek culture on that of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

, which contrasted with the then-fashionable view of Classical 'purity' advanced by Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding he ...

and his successors, such as Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy and Karl Bötticher

Karl Gottlieb Wilhelm Bötticher (29 May 1806, Nordhausen – 19 June 1889, Berlin) was a German archaeologist who specialized in architecture.

Biography

He was born in Nordhausen. He studied at the Academy of Architecture in Berlin, and was af ...

.

During his tenure at Athens, Ross travelled widely throughout Greece, including a journey to Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of , usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There are also wheelchair div ...

in 1837 with his brother Charles and Ernst Curtius

Ernst Curtius (; 2 September 181411 July 1896) was a German archaeologist, historian and museum director.

Biography

He was born in Lübeck. On completing his university studies he was chosen by Christian August Brandis, C. A. Brandis to acco ...

, the future excavator of Olympia

The name Olympia may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Olympia'' (1938 film), by Leni Riefenstahl, documenting the Berlin-hosted Olympic Games

* ''Olympia'' (1998 film), about a Mexican soap opera star who pursues a career as an athlet ...

. Alongside archaeology, he took an interest in modern Greek ethnography and folklore, including the spread of the Greek language, which he spoke sufficiently fluently that Greeks often mistook him for a native. In the summer of 1837, he travelled through the Greek islands, visiting Sikinos

Sikinos ( el, Σίκινος) is a Greek island and municipality in the Cyclades. It is located midway between the islands of Ios and Folegandros. Sikinos is part of the Thira regional unit.

It was known as Oenoe or Oinoe ( grc, Οἰνόη, ...

, Sifnos

Sifnos ( el, Σίφνος) is an island municipality in the Cyclades island group in Greece. The main town, near the center, known as Apollonia (pop. 869), is home of the island's folklore museum and library. The town's name is thought to come f ...

, Amorgos

Amorgos ( el, Αμοργός, ; ) is the easternmost island of the Cyclades island group and the nearest island to the neighboring Dodecanese island group in Greece. Along with 16 neighboring islets, the largest of which (by land area) is Niko ...

, Kea

The kea (; ; ''Nestor notabilis'') is a species of large parrot in the family Nestoridae found in the forested and alpine regions of the South Island of New Zealand. About long, it is mostly olive-green with a brilliant orange under its wings ...

, Kythnos

Kythnos ( el, Κύθνος), commonly called Thermia ( el, Θερμιά), is a Greek island and municipality in the Western Cyclades between Kea and Serifos. It is from the Athenian harbor of Piraeus. The municipality Kythnos is in area and has a ...

, Santorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

and Ios

iOS (formerly iPhone OS) is a mobile operating system created and developed by Apple Inc. exclusively for its hardware. It is the operating system that powers many of the company's mobile devices, including the iPhone; the term also includes ...

, accompanied by the surveyor Karl Ritter and publishing his explorations on Sikinos as ''Η Αρχαιολογία της Νήσου Σικίνου'' ( en, The Archaeology of the Island of Sikinos). His archaeological description of Sifnos was described, in 1956, as 'still the best account of the island we possess … for more than a hundred years of archaeological research has still produced no better guide to the islands than Ross'.

He subsequently travelled through the Greek islands and Asia Minor, making him one of the first Europeans to explore the interior of Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionians, Ionian and Dorians, Dorian Greeks colonized the west of i ...

and Lycia

Lycia (Lycian language, Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean ...

, in 1841 and 1843, journeys which he later published as ''Reisen auf den griechischen Inseln des Ägäischen Meeres'' ( en, Journeys on the Greek Islands of the Aegean Sea) in 1843 and 1845. He took a leave of absence for about half of 1839 and all of 1842, during which he visited Germany, and did not teach at all during the academic year 1841–1842. He regularly accompanied King Otto on archaeological travels during his time at Athens.

Ross was appointed as a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences

The Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities (german: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften) is an independent public institution, located in Munich. It appoints scholars whose research has contributed considerably to the increase of knowledg ...

in 1837, having previously been named to the Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

in 1836.

By the late 1830s, negative comments in the Greek press about the so-called 'Bavarocracy' () had become common, and the dominance of northern Europeans in Greek academia, archaeology and architecture had become a source of considerable unrest. During his Aegean travels of 1843, Ross received news of the revolution of 3 September, which forced Otto to dismiss most of the non-Greeks in public service, including Ross. He was succeeded as professor of archaeology by Alexandros Rizos Rangavis

Alexandros Rizos Rangavis or Alexander Rizos Rakgabis" ( el, Ἀλέξανδρος Ῥίζος Ῥαγκαβής; french: Alexandre Rizos Rangabé; 27 December 180928 June 1892), was a Greek man of letters, poet and statesman.

Early life

He was ...

in 1844.

Professorship at Halle (1843-1857)

University of Halle

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university i ...

in the German state of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, then ruled by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

. The beginning of his employment was delayed by Frederick William IV of Prussia

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

, who granted him a two-year travel stipendium, allowing him to spend time in Smyrna, Trieste and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. During the winter of 1844–1845, he organised excavations, led by Eduard Schaubert

Gustav Eduard Schaubert ( el, Εδουάρδος Σάουμπερτ, translit=Edouárdos Sáoumpert) 27 July 1804, Breslau, Prussia – 30 March 1860, Breslau) was a Prussian architect, who made a major contribution to the re-planning of Athens ...

, near Olympia

The name Olympia may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Olympia'' (1938 film), by Leni Riefenstahl, documenting the Berlin-hosted Olympic Games

* ''Olympia'' (1998 film), about a Mexican soap opera star who pursues a career as an athlet ...

. The project was financed by the Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

Ministry of Culture and the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

, to whom Ross' friend Alexander von Humboldt had introduced and recommended the project. Schaubert's excavations investigated a site reputed to be the grave of Coroebus of Elis

Coroebus of Elis ( grc-gre, Κόροιβος Ἠλεῖος, ''Kóroibos Ēleîos''; la, Coroebus Eleus) was a Greek cook, baker, and athlete from Elis. He is remembered as the winner (, ''olympioníkes'') of the first recorded Olympics, which ...

, the supposed victor of the first Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

in 776 BC, hoping to assess the origins of the Olympic Games and the historicity of Coroebus. The excavations were concluded in 1846, having found the remains of a grave of uncertain date, with traces of ashes, animal bones and pottery sherds, as well as bronze vessels and a bronze helmet, which Schaubert interpreted as remains of a hero cult

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" (, ) refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a ''dead'' ma ...

on the site.

A man named 'L. Ross' was referenced by the Arabist

An Arabist is someone, often but not always from outside the Arab world, who specialises in the study of the Arabic language and culture (usually including Arabic literature).

Origins

Arabists began in medieval Muslim Spain, which lay on the ...

Otto Blau

Otto is a masculine German given name and a Otto (surname), surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''Audo'', ''Odo'', ''Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name ...

as visiting Petra

Petra ( ar, ٱلْبَتْرَاء, Al-Batrāʾ; grc, Πέτρα, "Rock", Nabataean Aramaic, Nabataean: ), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō, is an historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. It is adjacent to t ...

in 1845. While Blau describes 'Ross' as an Englishman, David Kennedy has argued that Blau may have mistaken the nationality of the Scottish-descended Ludwig Ross, which would make Ross one of the earliest scholars to visit the site.

Ross eventually took his chair in Halle in 1845. He was an isolated figure in German academia, partly due to his criticism of well-respected scholars like the philologist Friedrich August Wolf

Friedrich August Wolf (; 15 February 1759 – 8 August 1824) was a German classicist and is considered the founder of modern philology.

Biography

He was born in Hainrode, near Nordhausen. His father was the village schoolmaster and organist ...

and the historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr

Barthold Georg Niebuhr (27 August 1776 – 2 January 1831) was a Danish–German statesman, banker, and historian who became Germany's leading historian of Ancient Rome and a founding father of modern scholarly historiography. By 1810 Niebuhr wa ...

, and partly due to his then-unfashionable emphasis upon the links between Greek and Near Eastern civilisation, which placed him in conflict with the views of Karl Otfried Müller

Karl Otfried Müller ( la, Carolus Mullerus; 28 August 1797 – 1 August 1840) was a German scholar and Philodorian, or admirer of ancient Sparta, who introduced the modern study of Greek mythology.

Biography

He was born at Brieg (modern Brze ...

, who had argued for the autochthonous

Autochthon, autochthons or autochthonous may refer to:

Fiction

* Autochthon (Atlantis), a character in Plato's myth of Atlantis

* Autochthons, characters in the novel ''The Divine Invasion'' by Philip K. Dick

* Autochthon, a Primordial in the ' ...

nature of Ancient Greek culture. His views were, however, supported by Julius Braun

Julius Braun (16 July 1825 in Karlsruhe – 1869 in Munich) was a German historian, with an interest in art, culture and religion.

Biography

Braun was born in Karlsruhe and received his early education at the city's lyceum. He then studied at the ...

in Germany and by Desiré-Raoul Rochette

Desiré-Raoul Rochette (March 6, 1790 – July 3, 1854), was a French archaeologist.

Born at Saint-Amand in the department of Cher, Raoul Rochette received his education at Bourges. In 1810, he obtained a chair of grammar in the Lyceum Louis- ...

in Paris. During a debate at Halle over the layout of its museum of art, Ross proposed that exhibits should be displayed on four walls, giving equal prominence to Greece, Rome, Egypt and Asia.

He published the third volume of ''Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae'' in 1845, and a treatise on the demes

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside seem to have existed in the 6th century BC and ear ...

of Attica with his colleague Eduard Meier in 1846. In 1848, he published ''Italics and Greeks: Did the Romans Speak Sanskrit or Greek?'' (german: Italiker und Gräken. Sprachen die Römer Sanskrit oder Griechisch?), in which he argued that Latin was a linguistic descendant of Greek in the same way that the Romance languages are descended from Latin, rejecting the emerging discoveries in the field of Indo-European studies

Indo-European studies is a field of linguistics and an interdisciplinary field of study dealing with Indo-European languages, both current and extinct. The goal of those engaged in these studies is to amass information about the hypothetical pro ...

.

Ross intended to publish his excavations of the Parthenon and the area of the Propylaia, complementing his 1839 publication of the Temple of Athena Nike, but had been forced by 1855 to abandon the project, partly due to financial constraints and partly due to the difficulty of collaborating with his co-authors Hansen and Schaubert without being physically present in Greece. In addition, both Karl Otfried Müller

Karl Otfried Müller ( la, Carolus Mullerus; 28 August 1797 – 1 August 1840) was a German scholar and Philodorian, or admirer of ancient Sparta, who introduced the modern study of Greek mythology.

Biography

He was born at Brieg (modern Brze ...

(in 1843) and Philippe Le Bas

Philippe Le Bas (18 June 1794 in Paris – 19 May 1860 in Paris) was a French hellenist, archaeologist and translator. He was the son of Philippe Le Bas and Elisabeth Duplay, the daughter of Robespierre's landlord Maurice Duplay. He was only 6 we ...

(in 1847) had already published some of the discoveries from the Temple of Athena Nike, relying on drawings made by others.

Personal life, death and legacy

In the spring of 1847, Ross married Emma Schwetschke, daughter of the publisher . Shortly thereafter, he developed the beginnings of a health condition, which gradually reduced his strength and mobility and caused him increasing pain and discomfort. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to treat his condition with spa cures.

Ross died by

In the spring of 1847, Ross married Emma Schwetschke, daughter of the publisher . Shortly thereafter, he developed the beginnings of a health condition, which gradually reduced his strength and mobility and caused him increasing pain and discomfort. He attempted, unsuccessfully, to treat his condition with spa cures.

Ross died by suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in 1859. He was buried in Bornhöved

Bornhöved () is a municipality in the '' Kreis'' (district) of Segeberg in Schleswig-Holstein, north Germany. It is situated some 16 km east of Neumünster.

Bornhöved is part of the ''Amt'' (municipal confederation) of Bornhöved

Bornh ...

, alongside his brother, Charles, who had died of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

the previous year.

Ross' reflections on his career in Greece, ''Erinnerungen und Mittheilungen aus Griechenland'' ( en, Reminiscences and Communications from Greece), were published posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award - an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication – material published after the author's death

* ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1987

* ''Posthumous'' (E ...

in 1863, with a foreword by his friend Otto Jahn

Otto Jahn (; 16 June 1813, in Kiel – 9 September 1869, in Göttingen), was a German archaeologist, philologist, and writer on art and music.

Biography

After the completion of his university studies at Christian-Albrechts-Universität in Kiel, t ...

. In the volume, which consisted largely of Ross' diaries and letters from his time in Greece, Ross alleged that technological backwardness and governmental incompetence had held back the development of Greece, and criticised both Otto's government and native Greek politicians for their 'localism' and the alleged weakness and lethargy of the royal administration.

Ross has been praised as one of the greatest figures in Greek epigraphy and as an important force in its beginnings as an academic discipline. His work was used heavily by August Böckh in his own influential epigraphical works, a debt which Böckh acknowledged in the subtitle of his 1840 work ''Documents on the Maritime Affairs of the Athenian State'' (german: Urkunden über das Seewesen des Attischen Staates): 'with eighteen panels, containing the copies made by Mr. Ludwig Ross.' While the execution of his restoration of the Temple of Athena Nike has been criticised, his excavation and restoration work has been praised for its systematic approach and for beginning a long trend of similar endeavours on the Acropolis. He has generally been viewed as a competent and successful Ephor General, whose service and resignation had significant consequences for the development of Greek archaeology.

Footnotes

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ross, Ludwig Classical archaeologists German classical scholars 1859 deaths 1806 births German people of Scottish descent Archaeology of Greece Ephors General of Greece