Lucy Ann (1810 ship) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Lucy Ann''(e) was built in Canada early in the 19th century and was brought to Australia in 1827. She was first employed as a trading vessel before purchase by the

''Lucy Ann'', under the command of Captain William Owen, left Sydney and arrived at

''Lucy Ann'', under the command of Captain William Owen, left Sydney and arrived at

Late in 1835 the Weller brothers decided to send the vessel

Late in 1835 the Weller brothers decided to send the vessel

The vessel called at

The vessel called at  Her next voyage was under Captain William Barr and was planned to last for two years. They departed Sydney 15 June 1846 and by 23 June were off Booby Shoal in the

Her next voyage was under Captain William Barr and was planned to last for two years. They departed Sydney 15 June 1846 and by 23 June were off Booby Shoal in the

''Argus'', 27 March 1855, p.4

/ref> It is unknown when and where she was finally broken up or sank.

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

government in 1828. In government service

A public service is any service intended to address specific needs pertaining to the aggregate members of a community. Public services are available to people within a government jurisdiction as provided directly through public sector agencies ...

the ship was used to help establish a number of new coastal settlements. She was also used to transport descendants of the ''Bounty'' mutineers from Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

in 1830.

Sold out of government service in 1831, ''Lucy Ann'' served as a trading vessel and support ship for whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

stations in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. She was then converted into a pelagic whaler and in that role made 11 deep-sea whaling voyages from Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

between 1835 and 1852. One of the crewmen who served aboard, in 1842, was American seaman Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

, who later wrote about his time aboard. The vessel was taken to Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

in the 1850s, and ended her days there as a storage hulk in the Yarra River

The Yarra River or historically, the Yarra Yarra River, (Kulin languages: ''Berrern'', ''Birr-arrung'', ''Bay-ray-rung'', ''Birarang'', ''Birrarung'', and ''Wongete'') is a perennial river in south-central Victoria, Australia.

The lower stre ...

.

Arrival in Australia

Her Australian registration papers say ''Lucy Ann'' was abrig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

of 213 tons built at Frederickton, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1817 or 1819. Another source, based on Canadian records, agree the vessel was built at Frederickston, but in 1810, and was initially called the ''William'' (236 tons). Yet another source says she was built at St Johns in 1809. What seems beyond dispute is that her length was 87 feet 3 inches, beam 23 feet 10 inches, with 5 feet 3 inches between decks.

''Lucy Ann'' departed London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

19 January 1827 under the command of Captain Ranulph Dacre

Ranulph Dacre (23 April 1797 – 27 June 1884) was a British master mariner and merchant active in Australia and New Zealand.

Early life

He was born to George and Julia Dacre at Marwell Hall, Hampshire, England on 23 April 1797. His father was ...

with a general cargo and a few passengers. After calls at Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and St Jago

Santiago (Portuguese for “ Saint James”) is the largest island of Cape Verde, its most important agricultural centre and home to half the nation's population. Part of the Sotavento Islands, it lies between the islands of Maio ( to the east) ...

the vessel arrived Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

on 22 May. She departed Hobart and arrived Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

26 June. After completing several voyages between Sydney and Hobart, Captain Dacre offered the vessel for sale to the New South Wales colonial government in August 1827. The offer was accepted, the government paying £2,200.

In government service

''Lucy Ann'' departed Sydney 23 October 1827 forWestern Port

Western Port, (Boonwurrung: ''Warn Marin'') commonly but unofficially known as Western Port Bay, is a large tidal bay in southern Victoria, Australia, opening into Bass Strait. It is the second largest bay in the state. Geographically, it is do ...

, on the coast of Victoria, where the government was attempting to establish a new settlement near present-day Corinella

Corinella is a town in Victoria, Australia, located 114 km south-east of Melbourne via the M1 and the Bass Highway, on the eastern shore of Western Port.

The town serves as a holiday destination, with a focus on recreational fishing, and h ...

. Aboard were 22 soldiers for the garrison, plus other settlers. The settlement was poorly located and later had to be abandoned. On 12 February 1828 she was despatched from Sydney to Moreton Bay

Moreton Bay is a bay located on the eastern coast of Australia from central Brisbane, Queensland. It is one of Queensland's most important coastal resources. The waters of Moreton Bay are a popular destination for recreational anglers and are ...

where the government was in the process of creating a new settlement that would eventually become the city of Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

.

In November 1828, ''Lucy Ann'' departed Sydney for King George's Sound

King George Sound ( nys , Menang Koort) is a sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came into use ...

in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

, and Fort Dundas

Fort Dundas was a short-lived British settlement on Melville Island between 1824 and 1828 in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. It was the first of four British settlement attempts in northern Australia before Goyder's survey an ...

on Melville Island off the northern coast, where two new government settlements were being established. The settlement at Melville Island was beset by problems and had to be abandoned. The colony at King George's Sound, the first in Western Australia, prospered and later became the modern city of Albany.

''Lucy Ann'' departed Sydney, on 26 December 1830, in company with HMS ''Comet'', to take aboard the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

and transfer them to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

. Pitcairn, it was decided, had become too small and crowded for the descendants of the Bounty

Bounty or bounties commonly refers to:

* Bounty (reward), an amount of money or other reward offered by an organization for a specific task done with a person or thing

Bounty or bounties may also refer to:

Geography

* Bounty, Saskatchewan, a g ...

mutineers and the British government had obtained permission from the Tahitian leadership for their resettlement on Tahiti. A dozen of the 86 islanders died in Tahiti due to their susceptibility to disease. For that reason, and, being homesick, they were returned to Pitcairn five months later.

''Lucy Ann'' was back in Sydney by June 1831 where it was announced she would soon be offered for sale. In September that year she was sold out of government service. Her new owners, who paid £1,200, were the Weller brothers

The Weller brothers, Englishmen of Sydney, Australia, and Otago, New Zealand, were the founders of a whaling station on Otago Harbour and New Zealand's most substantial merchant traders in the 1830s.

Immigration

The brothers, Joseph Brooks (1802� ...

, who were in the process of establishing a trading post and bay whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

station in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Whaling and trading

''Lucy Ann'', under the command of Captain William Owen, left Sydney and arrived at

''Lucy Ann'', under the command of Captain William Owen, left Sydney and arrived at Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

in October with stores and merchandise. This included 6 cases of muskets, 10 barrels and 104 half barrels of gunpowder and assorted whaling equipment. This whaling/trading community became one of the first European settlements in the area. ''Lucy Ann'' then went on to the North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

, for a cargo of timber, before returning to Sydney 29 February 1832, in need of repair. While in Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman Sea (p ...

someone tried to burn the vessel. George Weller offered a reward of £50 for apprehension of the culprit.

She departed again for New Zealand in May 1832 with general merchandise, returning early in October with more timber. She left for New Zealand again in mid November, returning in April 1833 with spars and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

. She was by now a regular trader on the trans-Tasman route. She left again for New Zealand in May with a whaling gang, 160 tons of empty oil casks and provisions, returning in November with 130 tuns of right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

oil, flax and 5 Maori passengers. This was reported to be the first oil brought from Otago. December saw her on the route again, returning 26 April 1834. She departed for New Zealand again in May, under Captain Anglin, and returned from Otago in August with whale oil. She departed in January 1835 on the New Zealand run and was back by mid May with more oil. The following month she left again for the Weller brothers for NZ, this time under the command of Captain Samuel Rapsey, and returned in October with oil.

Deep-sea whaling

Late in 1835 the Weller brothers decided to send the vessel

Late in 1835 the Weller brothers decided to send the vessel sperm whaling

Sperm whaling is the hunting of the marine mammals for the oil, meat and bone that can be extracted from their bodies. Sperm whales, a large and deep-diving species, produce a waxy substance that was especially useful during the Industrial Revolut ...

. ''Lucy Ann'' was modified for pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

whaling and departed Sydney under the command of Captain Thomas Richards in mid December 1835. The vessel cruised off New Zealand and called several times at the Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for its ...

for food, wood and water. She returned to Sydney on 13 April 1837 with 75 tuns of sperm whale oil.

Her second dedicated whaling voyage, again under Captain Richards, began in mid June 1837 and ended 11 months later when she returned to Sydney having taken 500 barrels of right whale oil and 300 of sperm whale oil. It seems the "black" oil was landed at Otago in October 1837, for transhipment to Sydney, after which she went sperm whaling.

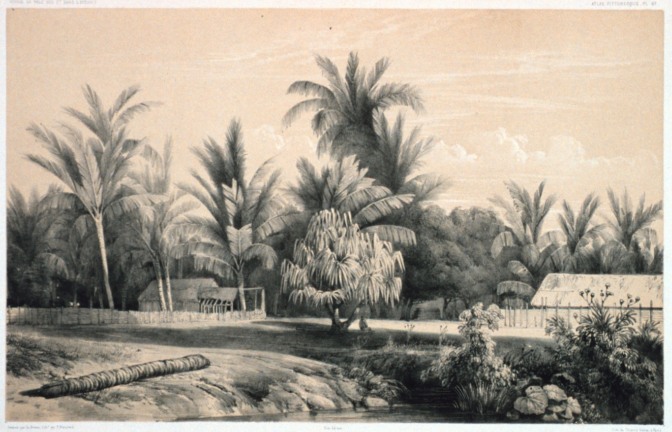

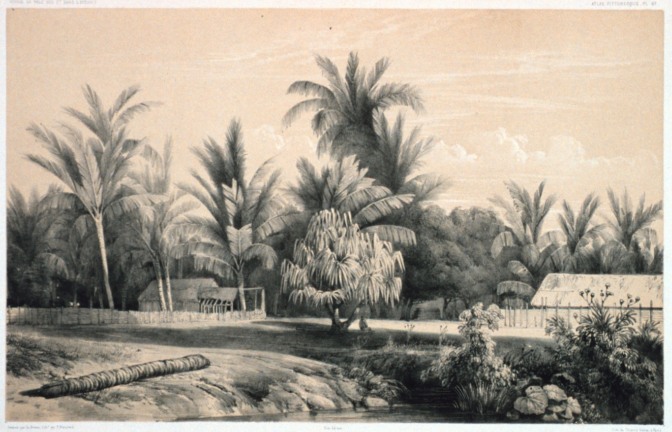

Her third voyage began 8 July 1838 under a new master, Captain Charles Aldrich. The voyage lasted 15 months during which time she was reported among the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

and at Tahiti. She visited Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland P ...

in September just before returning to Port Jackson on 13 October 1839 with a reported 800 barrels of sperm whale oil.

Under Captain Aldrich, she next made a brief three-month voyage, departing 24 November, to New Zealand to collect oil from the Weller brother's whaling establishment at Otago. She returned 10 February 1840 with 700 barrels worth of right whale oil and a 22-man whaling gang and other passengers.

Her fourth pelagic whaling voyage began, under Captain Aldrich, in mid May 1840. She was reported off Woodlark Island

Woodlark Island, known to its inhabitants simply as Woodlark or Muyua, is the main island of the Woodlark Islands archipelago, located in Milne Bay Province and the Solomon Sea, Papua New Guinea.

Although no formal census has been conducted sinc ...

late that year and at Port Stephens, in August 1841, in a very leaky state. She returned to Port Jackson 11 August with just 260 barrels of sperm whale oil. Back in Sydney the vessel received considerable repairs and was put up for sale. Her new owners sent her on another whaling voyage, under the command of Henry Ventom.

''Lucy Ann'' departed Sydney 14 February 1842, equipped with four whaleboats, and with a crew of about 30 men. She was at Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland P ...

late in February and was reported on the equator by late June. On 7 July 1842 she arrived at Santa Christina in the Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in th ...

for fresh provisions, wood and water. While here nine crewmen deserted and another eight were put in irons for “mutinous conduct.” By 8 August the vessel was at Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva (sometimes spelled Nukahiva or Nukuhiva) is the largest of the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of France in the Pacific Ocean. It was formerly also known as ''Île Marchand'' and ''Madison Island''.

Herman M ...

in the Marquesas where a more crewmen deserted. A few replacements were found on the island, one of them an American seaman, Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

. Melville would later describe the vessel in his book ''Omoo

''Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas'' is the second book by American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1847, and a sequel to his first South Sea narrative ''Typee'', also based on the author's experiences in the ...

'' as,

The vessel called at

The vessel called at Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

in September 1842 where eleven crewmen, including Melville, were put ashore for refusing to obey orders. ''Lucy Ann'' returned to Sydney on 20 May 1843 with just 250 barrels of sperm whale oil.

''Lucy Ann'' departed on her next voyage 25 June 1843 under the command of Captain Richard Lee. She touched at Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

in February 1843 and was reported off Lord Howe Island in March. She was at Port Stephens on the coast of New South Wales in May and in August at Port Cooper ( Lyttelton) New Zealand. She returned to Sydney 26 September 1844 with 614 barrels of oil. The vessel was purchased in January 1845 by high-profile entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd

Benjamin Boyd (21 August 180115 October 1851) was a Scottish entrepreneur who became a major shipowner, banker, grazier, politician and slaver, exploiting South Sea Islander labour in the British colony of New South Wales.

Boyd became one ...

who again sent her whaling.

Her commander on this voyage was Captain John Long (c1815-1852) and carried a crew of 30 men. She returned 10 months later with 700 barrels of oil. It was reported in the press, "The ''Lucy Ann'' has returned to port, owing to the badness of her whaling gear, as no dependance could be placed in either harpoons, lances or spades."

Her next voyage was under Captain William Barr and was planned to last for two years. They departed Sydney 15 June 1846 and by 23 June were off Booby Shoal in the

Her next voyage was under Captain William Barr and was planned to last for two years. They departed Sydney 15 June 1846 and by 23 June were off Booby Shoal in the Coral Sea

The Coral Sea () is a marginal sea of the South Pacific off the northeast coast of Australia, and classified as an interim Australian bioregion. The Coral Sea extends down the Australian northeast coast. Most of it is protected by the Fre ...

where they saw the wreck of the ''Peruvian'' (304 tons) which had left Sydney 26 February bound for Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

. Early in February 1847 ''Lucy Ann'' called at Stewart's Island (Sikaiana

Sikaiana (formerly called the Stewart Islands) is a small atoll NE of Malaita in Solomon Islands in the south Pacific Ocean. It is almost in length and its lagoon, known as Te Moana, is totally enclosed by the coral reef. Its total land ...

) in the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

for water and wood. The ship then cruised off New Britain

New Britain ( tpi, Niu Briten) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi the Dam ...

and New Ireland. Captain Barr went aboard the Sydney whaler ''Terror'' (Captain Downes) also owned by Benjamin Boyd, and Captain Barr told him of his crew troubles. Many of his crewmen were "twice-convicted convicts" and reported he had discovered and thwarted a plot by some of them to take control of the ship while the boats were away after whales. Captain Downes recorded Captain Barr bored him with his endless whaling stories. ''Lucy Ann'' returned to Sydney 28 June, twelve months early, largely due to crew problems and complaints about the food.

The next whaling voyage began 7 September 1847 under the command of Captain William Henry Downes. The vessel was off Wilson’s Promontory

Wilsons Promontory, is a peninsula that forms the southernmost part of the Australian mainland, located in the state of Victoria.

South Point at is the southernmost tip of Wilsons Promontory and hence of mainland Australia. Located at nea ...

on the coast of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

in October when Captain Downes boat upset while taking a whale and he was drowned. His body was placed in a cask or rum till return to Sydney for burial. Chief officer William Bearis then took command. The vessel cruised off the Kermadec Islands

The Kermadec Islands ( mi, Rangitāhua) are a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean northeast of New Zealand's North Island, and a similar distance southwest of Tonga. The islands are part of New Zealand. They are in total are ...

and was reported at Aneityum

Aneityum (also known as Anatom or Keamu) is the southernmost island of Vanuatu, in the province of Tafea.

Geography

Aneityum is the southernmost island of Vanuatu (not counting the Matthew and Hunter Islands, which are disputed with New Caledoni ...

and Lord Howe Island before returning to Sydney 29 January 1849 with 300 barrels of sperm whale oil. While at sea the vessel had been sold to William Campbell.

Her next whaling voyage, under the command of Captain William Greig, began on 19 June 1849. By June she was at Rotuma

Rotuma is a Fijian dependency, consisting of Rotuma Island and nearby islets. The island group is home to a large and unique Polynesian indigenous ethnic group which constitutes a recognisable minority within the population of Fiji, known as " ...

where more crewmen were recruited. She was anchored at Strong's Island

Strong's Island is an island in the Bay of Exploits, just off the coast of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The island measures 0.45 square miles and is connected to New World Island by a 150 yard long causewa ...

on 23 May 1850 when a water cask fell down the main hatch and struck the 2nd mate, Mr Davis. He suffered a fractured skill and died a few hours later and was buried on the island the following day. After 17 months away the vessel returned to Sydney with just 100 barrels of sperm whale oil, 3 tuns of coconut oil and a case of tortoiseshell

Tortoiseshell or tortoise shell is a material produced from the shells of the larger species of tortoise and turtle, mainly the hawksbill sea turtle, which is a critically endangered species according to the IUCN Red List largely because of its ...

.

The last whaling voyage began 24 March 1851, under the command of Captain James Lovett. She returned to port just a week later having experiencing a series of gales after which “the crew refused to proceed on the voyage.” Replacement crewmen were found and the vessel resumed the cruise on 4 April. By 7 June, ''Lucy Ann'' was reported at Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

where additional crewmen seem to have been recruited. By mid September they were off Nauru

Nauru ( or ; na, Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru ( na, Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Ki ...

and then New Ireland in October. They dropped anchor at Gower’s Harbour on New Ireland on 2 November 1851, where they encountered the schooner ''Ariel''. They told Captain Bradley of that vessel that they had earlier had some kind of violent clash with the natives of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. Captain Bradley described ''Lucy Ann'' as being "well armed and well manned". The vessel experienced a succession of gales prior to her return to Sydney where she arrived on 23 March 1852 with 300 barrels of sperm whale oil and a crew of 25 men.

Last years

''Lucy Ann'' departed Sydney on 25 May 1852 for Melbourne and arrived 11 June. While in Melbourne she was offered for sale as a store ship. The discovery of richgold fields

Gold Fields Limited (formerly The Gold Fields of South Africa) is one of the world's largest gold mining firms. Headquartered in Johannesburg, South Africa, the company is listed on both the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and the New York Sto ...

in central Victoria the year before had led to the arrival of large numbers of vessels to land cargo and passengers and created an urgent need for storage facilities in Port Phillip Bay

Port Phillip (Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, narrow channel known as The Rip, and is completel ...

. She was bought for use as coal depot by the owners of the steamer ''Gipsy''. In March 1855 she was offered for sale, as a storge hulk, as part of the estate of George A. Mouritz and changed hands again, this time for £85./ref> It is unknown when and where she was finally broken up or sank.

References

{{Reflist Whaling ships Ships of Australia Whaling in Australia Brigs of Australia Herman Melville