Lord Fisher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher, (25 January 1841 – 10 July 1920), commonly known as Jacky or Jackie Fisher, was a British Admiral of the Fleet. With more than sixty years in the

John Arbuthnot Fisher was born on 25 January 1841 on the Wavendon Estate at

John Arbuthnot Fisher was born on 25 January 1841 on the Wavendon Estate at

Fisher's father ultimately aided his entry into the navy, via his godmother Lady Horton, widow of the

Fisher's father ultimately aided his entry into the navy, via his godmother Lady Horton, widow of the  On 2 March 1856, Fisher was posted to , and was sent to Constantinople (now

On 2 March 1856, Fisher was posted to , and was sent to Constantinople (now  He was transferred, on 12 June 1860, to the paddle-

He was transferred, on 12 June 1860, to the paddle-

On 2 August 1869, "at the early age of twenty-eight", Fisher was promoted to

On 2 August 1869, "at the early age of twenty-eight", Fisher was promoted to

In spring 1882 ''Inflexible'' was part of the

In spring 1882 ''Inflexible'' was part of the

In April 1883 Fisher had recovered sufficiently to return to duty and was appointed commander of . He remained with ''Excellent'' for two years until June 1885, where he gained a following of officers concerned with the poor offensive capabilities of the fleet, including

In April 1883 Fisher had recovered sufficiently to return to duty and was appointed commander of . He remained with ''Excellent'' for two years until June 1885, where he gained a following of officers concerned with the poor offensive capabilities of the fleet, including

Unlike the North America and West Indies station, the Mediterranean Fleet was a vital British command operating from Alexandria and

Unlike the North America and West Indies station, the Mediterranean Fleet was a vital British command operating from Alexandria and

After spending September and the first half of October on the continent Fisher took office as First Sea Lord on 20 October 1904. The appointment came with a house in

After spending September and the first half of October on the continent Fisher took office as First Sea Lord on 20 October 1904. The appointment came with a house in

He retired to

He retired to

Fisher was made chairman of the Government's

Fisher was made chairman of the Government's

ADM 196/15

at The National Archives (United Kingdom), The National Archives. A full PDF is available (fee required

Documents Online—Image Details—Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, John

excerpt

see Dreadnought (book), popular history; pp 401–432. * * *

Transcription of Service Record on admirals.org.uk

* *

The Papers of John Fisher, 1st Lord Fisher of Kilverstone

held at the Churchill Archives Centre , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fisher, John Fisher, 1st Baron Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom First Sea Lords and Chiefs of the Naval Staff Lords of the Admiralty Royal Navy admirals of the fleet 1841 births 1920 deaths British people of World War I Royal Navy personnel of the Second Opium War Royal Navy personnel of the Anglo-Egyptian War Royal Navy personnel of the Crimean War Royal Navy admirals of World War I Members of the Order of Merit Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers People educated at King Henry VIII School, Coventry People of British Ceylon Deaths from cancer in England Peers created by Edward VII

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, his efforts to reform the service helped to usher in an era of modernisation which saw the supersession of wooden sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s armed with muzzle-loading

A muzzleloader is any firearm into which the projectile and the propellant charge is loaded from the muzzle of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern (higher tech and harder to make) design ...

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

by steel-hulled battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s, submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s and the first aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s.

Fisher has a reputation as an innovator, strategist and developer of the navy rather than as a seagoing admiral involved in major battles, although in his career he experienced all these things. When appointed First Sea Lord in 1904 he removed 150 ships then on active service which were no longer useful and set about constructing modern replacements, developing a modern fleet prepared to meet Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Fisher saw the need to improve the range, accuracy and rate-of-fire of naval gunnery

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firing weapons and excludes ...

, and became an early proponent of the use of the torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

, which he believed would supersede big guns for use against ships. As Controller, he introduced torpedo-boat destroyers

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in 1 ...

as a class of ship intended for defence against attack from torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s or from submarines. As First Sea Lord he drove the construction of , the first all-big-gun battleship, but he also believed that submarines would become increasingly important and urged their development. He became involved with the introduction of turbine engine

A gas turbine, also called a combustion turbine, is a type of continuous flow internal combustion engine. The main parts common to all gas turbine engines form the power-producing part (known as the gas generator or core) and are, in the directi ...

s to replace reciprocating engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

s, and with the introduction of oil fuelling to replace coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

. He introduced daily baked bread on board ships, whereas when he entered the service it was customary to eat hard biscuits, frequently infested by biscuit beetle

The drugstore beetle (''Stegobium paniceum''), also known as the bread beetle, biscuit beetle, and misnamed as the biscuit weevil (despite not being a true weevil), is a tiny, brown beetle that can be found infesting a wide variety of dried pla ...

s.

He first officially retired from the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

in 1910 on his 69th birthday, but became First Sea Lord again in November 1914. He resigned seven months later in frustration over Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

's Gallipoli campaign, and then served as chairman of the Government's Board of Invention and Research

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard, a t ...

until the end of the war.

Character and appearance

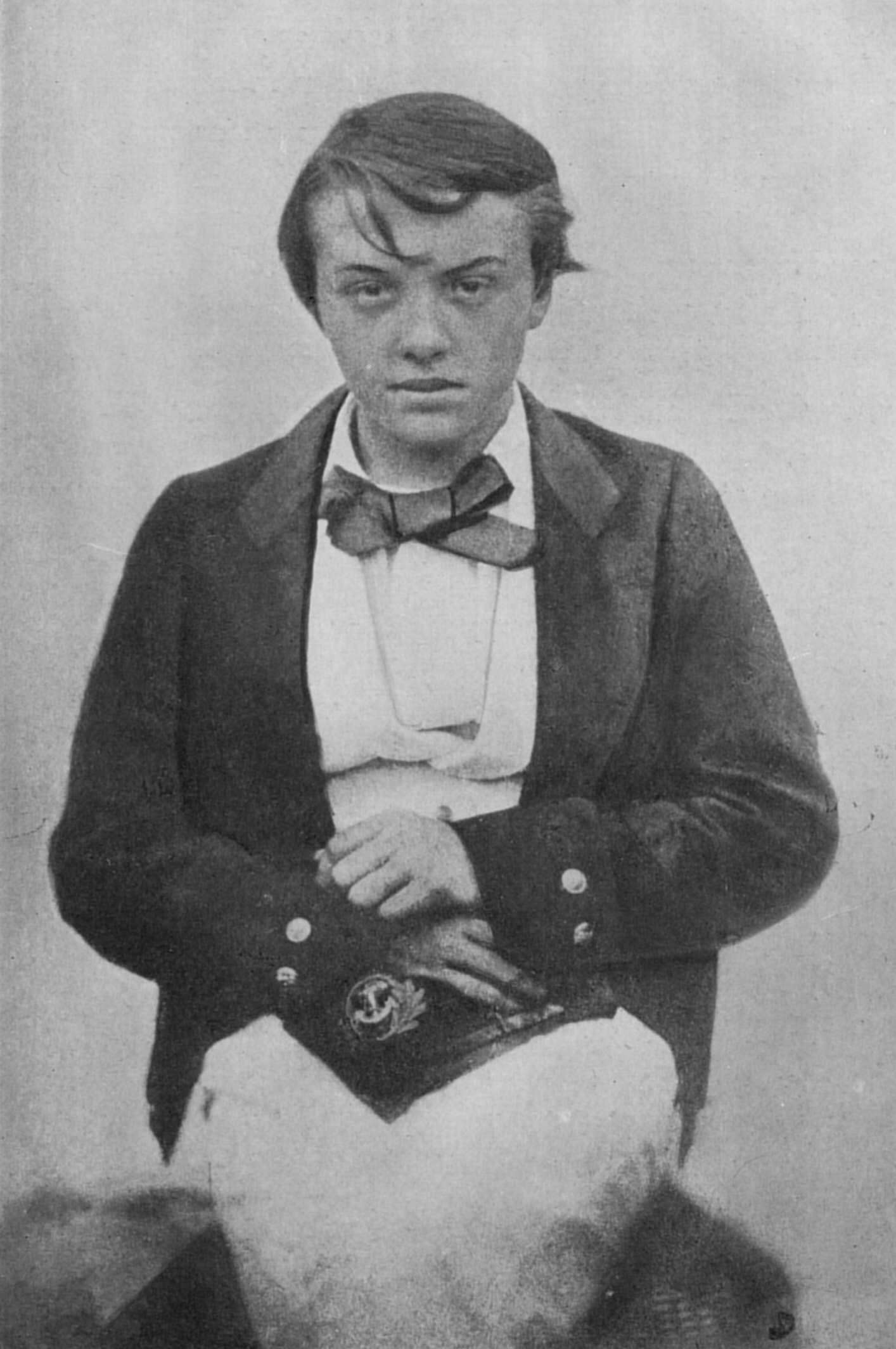

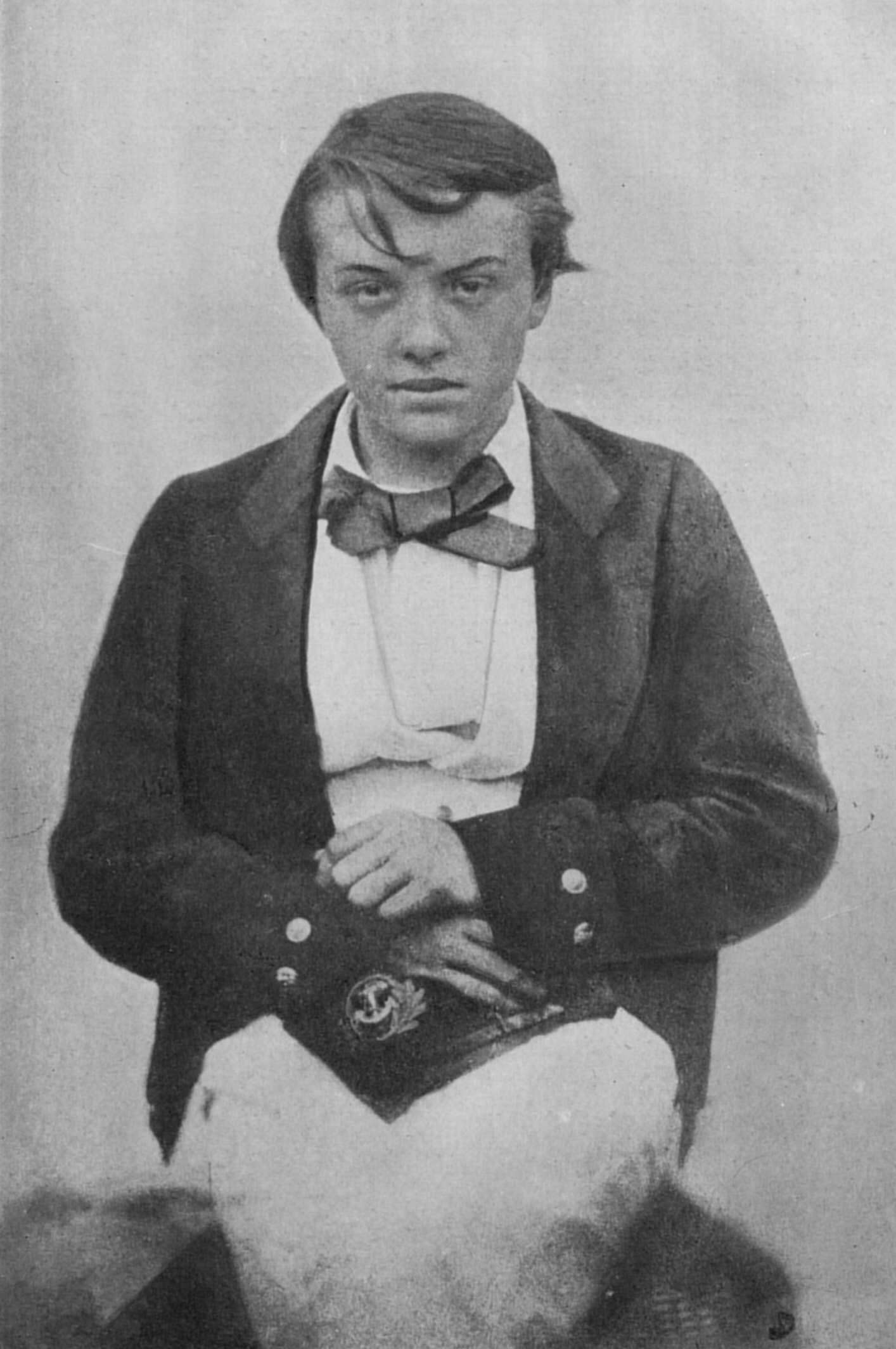

Fisher was five feet seven inches tall and stocky with a round face. In later years, some suggested that Fisher, born inCeylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

of British parents, had Asian ancestry due to his features and the yellow cast of his skin. However, his colour resulted from dysentery and malaria in middle life, which nearly caused his death. He had a fixed and compelling gaze when addressing someone, which gave little clue to his feelings. Fisher was energetic, ambitious, enthusiastic and clever. A shipmate described him as "easily the most interesting midshipman I ever met". When addressing someone he could become carried away with the point he was seeking to make, and on one occasion, the King asked him to stop shaking his fist in his face. He was considered a "man who demanded to be heard, and one who didn't suffer fools lightly".

Throughout his life he was a religious man and attended church regularly when ashore. He had a passion for sermons and might attend two or three services in a day to hear them, which he would 'discuss afterwards with great animation'. However, he was discreet in expressing his religious views because he feared public attention might hinder his professional career.

He was not keen on sport, but he was a highly proficient dancer. Fisher employed his dancing skill later in life to charm a number of important ladies. He became interested in dancing in 1877 and insisted that the officers of his ship learn to dance. Fisher cancelled the leave of midshipmen who would not take part. He introduced the practice of junior officers dancing on deck when the band was playing for senior officers' wardroom

The wardroom is the mess cabin or compartment on a warship or other military ship for commissioned naval officers above the rank of midshipman. Although the term typically applies to officers in a navy, it is also applicable to marine officers ...

dinners. This practice spread through the fleet. He broke with the then ball tradition of dancing with a different partner for each dance, instead adopting the scandalous habit of choosing one good dancer as his partner for the evening. His ability to charm all comers of all social classes made up for his sometimes blunt or tactless comments. He suffered from seasickness throughout his life.

Fisher's aim was 'efficiency of the fleet and its instant readiness for war', which won him support amongst a certain kind of navy officer. He believed in advancing the most able, rather than the longest serving. This upset those he passed over. Thus, he divided the navy into those who approved of his innovations and those who did not. As he became older and more senior he also became more autocratic and commented, 'Anyone who opposes me, I crush'. He believed that nations fought wars for material gain, and that maintaining a strong navy deterred other nations from engaging it in battle, thus decreasing the likelihood of war: "On the British fleet rests the British Empire." Fisher also believed that the risk of catastrophe in a sea battle was far greater than on land: a war could be lost or won in a day at sea, with no hope of replacing lost ships, but an army could be rebuilt quickly. When an arms race broke out between Germany and Britain to build larger navies, the German Kaiser commented, 'I admire Fisher, I say nothing against him. If I were in his place I should do all that he has done and I should do all that I know he has in mind to do'.

Childhood and personal life

John Arbuthnot Fisher was born on 25 January 1841 on the Wavendon Estate at

John Arbuthnot Fisher was born on 25 January 1841 on the Wavendon Estate at Ramboda

Ramboda is a village in Sri Lanka. It is located within Central Province.

The Ramboda Road Tunnel is currently the longest road tunnel in Sri Lanka and is situated on the A5 highway (Perandenyia - Nuwara Eliya Road), close to Ramboda falls. ...

in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

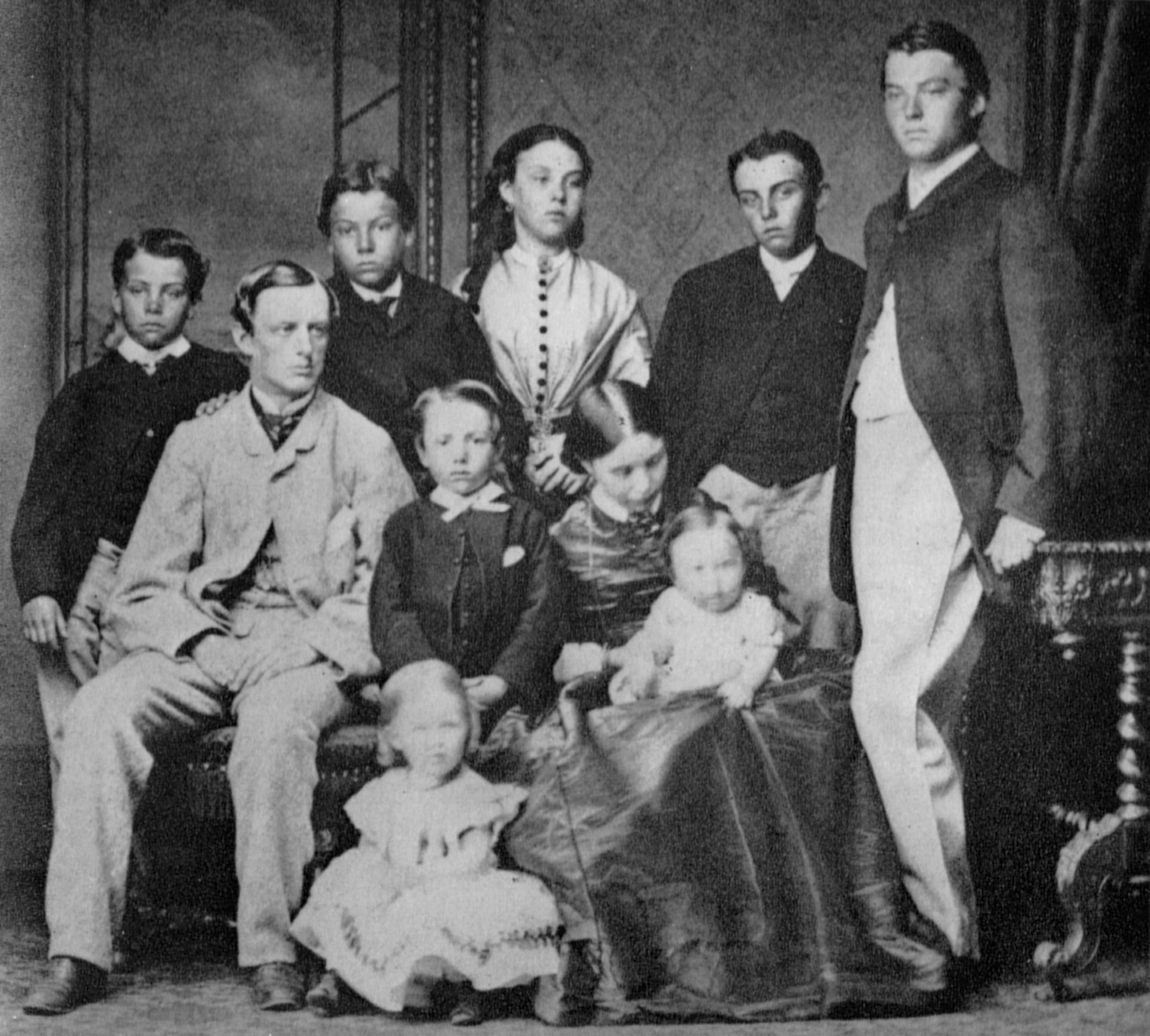

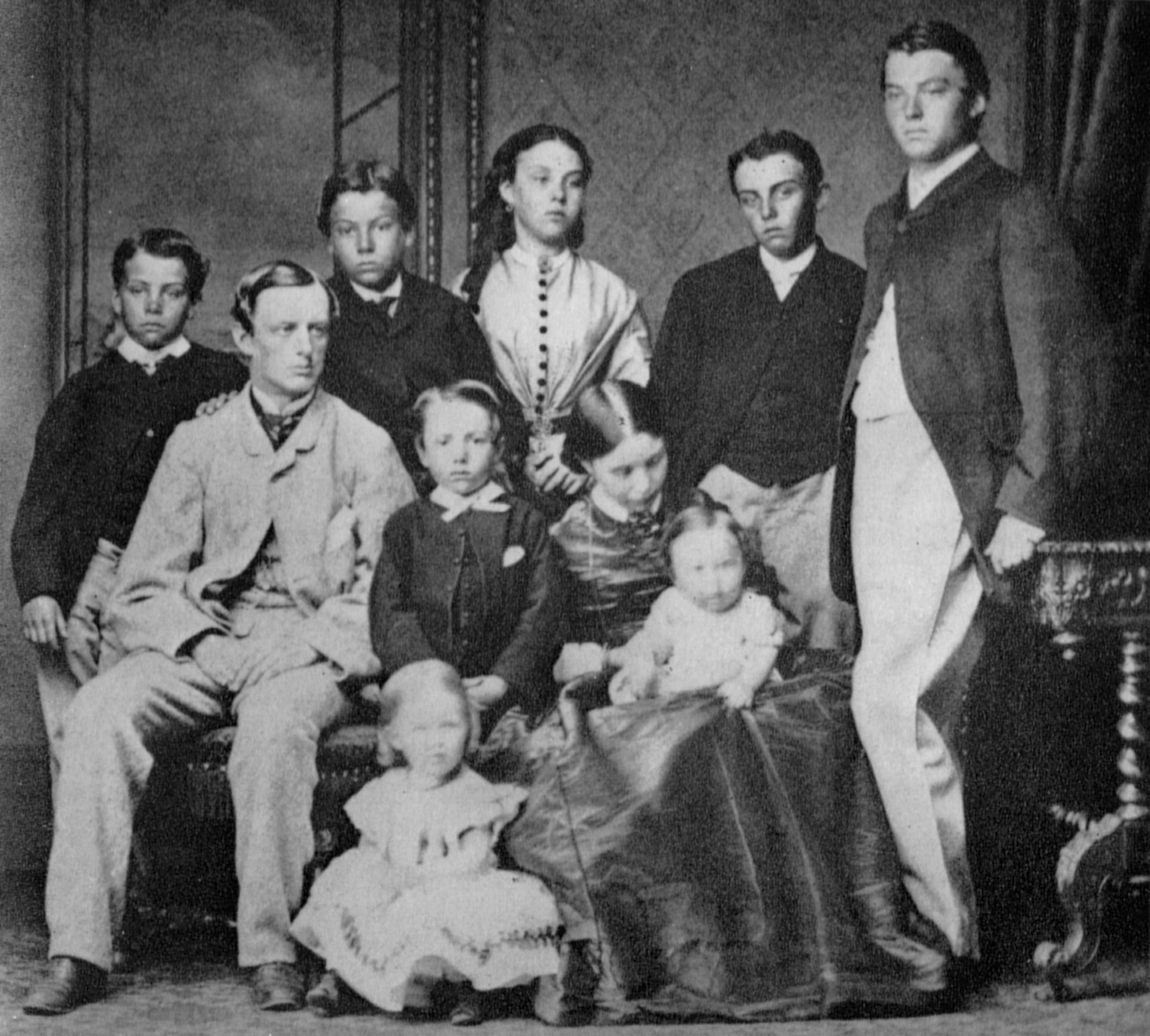

. He was the eldest of eleven children, of whom only seven survived infancy, born to Sophie Fisher and Captain William Fisher, a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer in the 78th Highlanders, who had been an aide-de-camp to the former governor of Ceylon, Sir Robert Wilmot-Horton, and was serving as a staff officer at Kandy

Kandy ( si, මහනුවර ''Mahanuwara'', ; ta, கண்டி Kandy, ) is a major city in Sri Lanka located in the Central Province. It was the last capital of the ancient kings' era of Sri Lanka. The city lies in the midst of hills ...

. Fisher commented, 'My mother was a most magnificent and handsome, extremely young woman....My father was 6 feet 2 inches..., also especially handsome. Why I am ugly is one of those puzzles of physiology which are beyond finding out'.

William Fisher sold his commission the year John was born, and became a coffee planter and later chief superintendent of police. He incurred such debt on his two coffee plantations that he could barely support his growing family. At the age of six John (who was always known within the family as "Jack") was sent to England to live with his maternal grandfather, Charles Lambe, in New Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

, London. His grandfather had also lost money and the family survived by renting out rooms in their home. John's younger brother, Frederic William Fisher, joined the Royal Navy and reached the rank of admiral, and his youngest surviving sibling Philip became a navy lieutenant on before drowning in an 1880 storm.

William Fisher was killed in a riding accident when John was 15. John's relationship with his mother Sophie suffered from their separation, and he never saw her again. However, he continued to send her an allowance until her death. In 1870, she suggested visiting Fisher in England, but he dissuaded her as strongly as he could. Fisher wrote to his wife: "I hate the very thought of it and really, I don't want to see her. I don't see why I should as I haven't the slightest recollection of her."

Fisher married Frances Katharine Josepha Broughton, known as 'Kitty', the daughter of the Rev. Thomas Delves Broughton and Frances Corkran, on 4 April 1866 while stationed at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. Kitty's two brothers were both naval officers. According to a cousin, she believed that Jack would rise "to the top of the tree." They remained married until her death in July 1918. They had a son, Cecil Vavasseur, 2nd Baron Fisher (1868–1955), and three daughters, Beatrix Alice (1867–1930), Dorothy Sybil (1873–1962), and Pamela Mary (1876–1949), all of whom married naval officers who went on to become admirals. Beatrix Alice married Reginald Rundell Neeld in 1896, Pamela Mary married Henry Blackett in 1906, and in 1908 Dorothy Sybil married Eric Fullerton

Admiral Sir Eric John Arthur Fullerton, KCB, DSO (1878 – 9 November 1962) was a Royal Navy officer.

Naval career

Fullerton was the second son of Admiral Sir John Fullerton and entered the Royal Navy himself in 1892 as a cadet in HMS ...

.

Early career (1854–1869)

Fisher's father ultimately aided his entry into the navy, via his godmother Lady Horton, widow of the

Fisher's father ultimately aided his entry into the navy, via his godmother Lady Horton, widow of the governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

to whom William Fisher had been Aide-de-camp. She prevailed upon a neighbour, Admiral Sir William Parker (the last of Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

's captains), to nominate John as a naval cadet. The entry examination consisted of writing out the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

and jumping naked over a chair. He formally entered the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

on 13 July 1854, aged 13, on board Nelson's former flagship, , at Portsmouth. On 29 July he joined , an old ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

. She was built of wood, in 1831, with 84 smooth-bore muzzle-loading guns arranged on two gun decks, and relied entirely on sail for propulsion. She had a crew of 700, and discipline was strictly enforced by the "hard-bitten Captain Robert Stopford". Fisher fainted when he witnessed eight men being flogged on his first day.

''Calcutta'' participated in the blockade of Russian ports in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, entitling Fisher to the Baltic Medal, before returning to Britain a few months later. The crew was paid off on 1 March 1856.

On 2 March 1856, Fisher was posted to , and was sent to Constantinople (now

On 2 March 1856, Fisher was posted to , and was sent to Constantinople (now Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

) to join her. He arrived on 19 May, just as the war was ending. After a tour around the Dardanelles picking up troops and baggage, ''Agamemnon'' returned to England, where the crew was paid off.

Promotion to midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

came on 12 July 1856 and Fisher joined a 21-gun steam corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

, , part of the China Station. He was to spend the next five years in Chinese waters, seeing action in the Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire and the French Emp ...

, 1856–1860. The ''Highflyer's'' captain, Charles Shadwell, was an expert on naval astronomy (subsequently being appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1861) and he taught Fisher much about navigation, with spectacular later results. When Shadwell was replaced as captain following an injury in action, he gave Fisher a pair of studs engraved with his family motto 'Loyal au Mort', which Fisher was to use for the rest of his life.

Fisher passed the seamanship examination for the rank of lieutenant, and was given the acting rank of mate

Mate may refer to:

Science

* Mate, one of a pair of animals involved in:

** Mate choice, intersexual selection

** Mating

* Multi-antimicrobial extrusion protein, or MATE, an efflux transporter family of proteins

Person or title

* Friendship ...

, on his nineteenth birthday, 25 January 1860. He was transferred three months later to the steam frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

as an acting lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. Shortly afterwards, Fisher had his first brief command: taking the yacht of the China Squadron's admiral—the paddle- gunboat —from Hong Kong to Canton (presently Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

), a voyage of four days.

He was transferred, on 12 June 1860, to the paddle-

He was transferred, on 12 June 1860, to the paddle-sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

where he saw sufficient action to add the Taku Forts

The Taku Forts or Dagu Forts, also called the Peiho Forts are forts located by the Hai River (Peiho River) estuary in the Binhai New Area, Tianjin, in northeastern China. They are located southeast of the Tianjin urban center.

History

The f ...

and Canton clasps to his China War Medal. ''Furious'' left Hong Kong and the China Station in March 1861 and, after a leisurely voyage home, paid off her crew in Portsmouth on 30 August. Captain Oliver Jones of the ''Furious'' was entirely different from Shadwell: Fisher wrote there was a mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

on board within his first fortnight, that Jones terrorized his crew and disobeyed orders given to him. For his part, by the end of the tour, Jones was impressed by Fisher.

At the end of November 1861, Fisher sat his final lieutenant's examination in navigation at the Royal Naval College at Portsmouth, passing with flying colours. He had already received top grades in seamanship and gunnery, and achieved the highest score then attained under the recently introduced five-yearly scheme, with 963 out of 1,000 marks in navigation. For this, he was awarded the Beaufort Testimonial, an annual prize of books and instruments; but in the meantime he had to wait around, unpaid, until his appointment came through officially.

From January 1862 to March 1863, Fisher returned to the payroll at the navy's principal gunnery school aboard , a three-decker

A three-decker was a sailing warship which carried her principal carriage-mounted guns on three fully armed decks. Usually additional (smaller) guns were carried on the upper works (forecastle and quarterdeck), but this was not a continuous b ...

moored in Portsmouth harbour. During this time, ''Excellent'' was evaluating the performance of the "revolutionary" Armstrong breech-loading guns against the conventional Whitworth muzzle-loading type. During free afternoons Fisher would walk the downs, shouting to practice his command voice. He spent 15 of the next 25 years in four tours of duty at Portsmouth concerned with development of gun

A gun is a ranged weapon designed to use a shooting tube (gun barrel) to launch projectiles. The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid (e.g. in water guns/cannons, spray guns for painting or pressure washing, pr ...

nery and torpedoes

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

.

In March 1863, Fisher was appointed Gunnery Lieutenant to , the first all-iron seagoing armoured battleship and the most powerful ship in the fleet. Built in 1859, she marked the beginning of the end of the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid- 15th) to the mid- 19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the introduction of naval ...

and, coincidentally, was armed with both Armstrong gun

An Armstrong gun was a uniquely designed type of Rifled breech-loader, rifled breech-loading field and heavy gun designed by William George Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong, Sir William Armstrong and manufactured in England beginning in 1855 by the ...

s (breech-loading) and Whitworth rifle

The Whitworth rifle was an English-made percussion rifle used in the latter half of the 19th century. A single-shot muzzleloader with excellent long-range accuracy for its era, especially when used with a telescopic sight, the Whitworth rifle w ...

s (muzzle-loading). Fisher noted he was popular amongst his brother officers because he frequently stayed on board when others went ashore and could take duty for them.

Fisher returned to ''Excellent'' in 1864 as a gunnery instructor, where he remained until 1869. Towards the end of his posting he became interested in torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

es, which were invented in the 1860s, and championed their cause as a relatively simple weapon capable of sinking a battleship. His expertise with torpedoes led to his being invited to Germany in June 1869 for the founding ceremony of a new naval base at Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

, where he met King William I of Prussia

William I or Wilhelm I (german: Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig; 22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888) was King of Prussia from 2 January 1861 and German Emperor from 18 January 1871 until his death in 1888. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he was the f ...

(soon to become German emperor), Bismarck and Moltke

The House of Moltke is the name of an old German noble family. The family was originally from Mecklenburg, but apart from Germany, some of the family branches also resided throughout Scandinavia. Members of the family have been noted as pigfarme ...

. Perhaps inspired by the visit, he started preparing a paper on the design, construction and management of electrical torpedoes, the cutting-edge technology of the time.

Commander (1869–1876)

On 2 August 1869, "at the early age of twenty-eight", Fisher was promoted to

On 2 August 1869, "at the early age of twenty-eight", Fisher was promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

. On 8 November, he was posted as second-in-command of , serving under Captain Hewett, a Crimean War Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

holder. ''Donegal'' was a , with auxiliary screw propulsion. She plied between Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

and Hong Kong, taking out relief crews and bringing home the crews they replaced. During this time he completed his torpedoes treatise.

In May 1870, Fisher transferred, again as second in command, to , flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the China Station. It was whilst he was on ''Ocean'' that he wrote an eight-page memoir: "Naval Tactics", which Captain J. G. Goodenough had printed for private circulation. He installed a system of electrical firing so that all guns could be fired simultaneously, making ''Ocean'' the first vessel to be so equipped. Fisher noted in his letters that he greatly missed his wife, but also missed his work on torpedoes and the access to important people possible with a posting in England.

In 1872, he returned to England to the gunnery school ''Excellent'', this time as head of torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

and mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

training, during which time he split the Torpedo Branch off from ''Excellent'', forming a separate establishment for it called . His duties included lecturing, and negotiating the purchase of the navy's first Whitehead torpedo

The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo ever developed. It was perfected in 1866 by Robert Whitehead from a rough design conceived by Giovanni Luppis of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in Fiume. It was driven by a th ...

. In order to promote the school, he invited politicians and journalists to attend lectures and organised demonstrations. This produced mixed reactions amongst some officers, who did not approve of his showmanship. He was promoted to captain on 30 October 1874, aged thirty-three, in time to be ''Vernon''s first commander. ''Vernon'' consisted of the hulk of , William Symonds

Sir William Symonds CB FRS (24 September 1782 – 30 March 1856, aboard the French steamship ''Nil'', Strait of Bonifacio, Sardinia)torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

of 245 tons, was ''Vernon's'' experimental tender for the conduct of torpedo trials. They were moored in Portsmouth Harbour

Portsmouth Harbour is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest between Portsmouth and Gosport in Hampshire. It is a Ramsar site and a Special Protection Area.

It is a large natural harbour in Hampshire, England. Geographically it i ...

. In 1876, Fisher served on the Board of Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

's torpedo committee.

Captain R.N. (1876–1883)

* September 1876 – March 1877: On half-pay with his family. * 30 January 1877 – 1 March 1877: Commanding . Fisher was appointed to command asflag captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a "captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "First ...

to the Admiral of the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

, Astley Cooper Key, from 2 March 1877 to 4 June 1878. Bellerophon had been in the dockyard for repairs, so the new crew was less than perfect in carrying out their duties. Fisher told them ''I intend to give you hell for three months, and if you have not come up to my standard in that time you'll have hell for another three months.'' Midshipman (later Admiral) A. H. Gordon Moore reported, ''Fisher was a very exacting master and I had at times long and arduous duties, long hours at the engine room telegraphs in cold fog, etc., and the least inattention was punished. It was, I think, his way of proving us, for he always rewarded us in some way when an extra hard bit of work was over.''

Cooper Key was transferred to a special squadron operating in the Channel formed to combat fears of war with Russia. Fisher went with him as flag captain of HMS ''Hercules'' from 7 June to 21 August 1878. From 22 August to 12 September he transferred still as flag captain under Cooper Key to . At this time Fisher first became a proponent of the new compass being designed by Sir William Thomson which incorporated corrections for the deviation caused by the metal in iron ships.

From 9 January to 24 July 1879 Fisher commanded serving in the Mediterranean Command under Geoffrey Phipps Hornby. ''Pallas'' was in poor condition, having a chain passed around the ship to hold the armour plates in place. The tour included an official visit to Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

where Fisher dined with the sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

from gold cups and plates. He then returned to the UK for two months leave at half pay, visiting Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

with his family.

His next posting, starting 25 September 1879, was to as Flag Captain to Sir Leopold McClintock, commanding the North American squadron. ''Northampton'' was a new ship with a number of innovations, including twin screws, searchlights and telephones, as well as being armed with torpedoes. It was fitted with an experimental Thomson-designed compass, which the inventor was on hand to adjust. Three days were spent attempting and failing to adjust the compass, with Thomson becoming increasingly bad tempered, until it was noticed that by accident the degree card had been marked with only 359 instead of 360 degrees. The ship was fitted with a new design of lamp created by Captain Philip Colomb, who came on board to inspect them. As a joke, Fisher arranged for anything that could go wrong with the lamps to do so, sending Colomb away disheartened over his invention (although Fisher officially reported favourably about the lamps). On another occasion, the naval hospital at Halifax requested some flags to fly for the Queen's birthday. Fisher obliged, but sent only yellow and black flags signifying plague and quarantine. On the other hand, he worked hard at improving his ship. As reported by his second in command, Commander Wilmot Fawkes

Admiral Sir Wilmot Hawksworth Fawkes, (22 December 1846 – 29 May 1926) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth.

Naval career

Fawkes joined the Royal Navy in 1860 and by 1867 had been promoted to lieutenant. He ...

, the ship carried out 150 runs with torpedoes in a fortnight, whereas the whole rest of the navy performed only 200 in a year.

Fisher's brother Philip was serving on the training ship , which disappeared somewhere between the West Indies and England, believed lost in a storm. ''Northampton'' was one of the ships sent to search for her, but without result. In January 1881 Fisher received news of his appointment to the new ironclad battleship . Admiral McClintock commented, ''Everyone regrets the departure of Captain Fisher, but I fancy we shall not fully realize our loss until he is gone....Since his nomination to the ''Inflexible'', his spirits have returned and daily increased, and now he almost requires wiring down.'' The ship was still building, so Fisher was temporarily appointed to , flagship of the port admiral at Portsmouth between 30 January and 4 July 1881.

HMS ''Inflexible''

Fisher was considered sufficiently able, with recommendations following all of his postings, to be appointed captain of the newly completed battleship . ''Inflexible'' had the largest guns and thickest armour of any ship in the navy, but still carried masts and sails and had slow, muzzle-loading guns. She had been seven years under construction and had many innovations built into her, including electric lighting and torpedo tubes, but with such a tortuous layout that crew became lost. The sails were never used for propulsion, but because a ship's performance was partly judged on the speed with which a ship could set sails, Fisher was obliged to drill the crew in their use. In spring 1882 ''Inflexible'' was part of the

In spring 1882 ''Inflexible'' was part of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

and was assigned to protection of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

during a visit to Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

on the Riviera

''Riviera'' () is an Italian word which means "coastline", ultimately derived from Latin , through Ligurian . It came to be applied as a proper name to the coast of Liguria, in the form ''Riviera ligure'', then shortened in English. The two areas ...

. This was intended as a reminder of British naval prowess to the French, but allowed Fisher to meet Victoria and her grandson, Prince Henry of Prussia

Prince Henry of Prussia can refer to:

*Prince Henry of Prussia (1726–1802)

*Prince Henry of Prussia (1747–1767)

*Prince Henry of Prussia (1781–1846)

*Prince Henry of Prussia (1862–1929)

*Prince Henry of Prussia (1900–1904)

Prince Henry ...

, who later became admiral of the German navy. Victoria was impressed by Fisher, as she had been by his brother Philip who had served on royal yachts and for whom she had arranged the ill-fated posting to ''Atalanta''.

''Inflexible'' took part in the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

, bombarding the port of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

as part of Admiral Seymour's fleet. Fisher was placed in charge of a landing party which was quartered in the Khedive's palace. Lacking means of reconnaissance, he devised a plan to armour a train with iron plates, machine gun and cannon. This became celebrated and widely reported by correspondents, so that its inventor, Fisher, came to the attention of the public for the first time as a hero. Shore duty had the unfortunate effect that Fisher became seriously ill with dysentery and malaria. He refused to take sick leave, but eventually was ordered home by Lord Northbrook, who commented, 'the Admiralty could build another ''Inflexible'', but not another Fisher'.

During this time he became a close friend of the future King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

and Queen Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

. He was appointed a Companion of the Bath (CB) in 1882.

Home postings

From January to April 1883 Fisher was on half pay recovering from his illness. In January he was invited to visitOsborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

for a fortnight by Queen Victoria, concerned about the charming Captain Fisher. Fisher, having entered the navy penniless and unknown, was delighted.

In April 1883 Fisher had recovered sufficiently to return to duty and was appointed commander of . He remained with ''Excellent'' for two years until June 1885, where he gained a following of officers concerned with the poor offensive capabilities of the fleet, including

In April 1883 Fisher had recovered sufficiently to return to duty and was appointed commander of . He remained with ''Excellent'' for two years until June 1885, where he gained a following of officers concerned with the poor offensive capabilities of the fleet, including John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland ...

and Percy Scott

Admiral Sir Percy Moreton Scott, 1st Baronet, (10 July 1853 – 18 October 1924) was a British Royal Navy officer and a pioneer in modern naval gunnery. During his career he proved to be an engineer and problem solver of some considerable f ...

. For the next 15 months he had no naval command and still suffered the effects of his illness. He took to visiting Marienbad, which was famous amongst notable society for its restoring climate, and went there regularly in later years.

During June–July 1885 Fisher served a short posting to in the Baltic under Admiral Hornby, following the Panjdeh Incident

The Panjdeh Incident (known in Russian historiography as the Battle of Kushka) was an armed engagement between the Emirate of Afghanistan and the Russian Empire in 1885 that led to a diplomatic crisis between the British Empire and the Russian ...

, which led to fear of war with Russia.

From November 1886 to 1890, he was Director of Naval Ordnance

The Naval Ordnance Department, also known as the Department of the Director of Naval Ordnance, was a former department of the Admiralty responsible for the procurement of naval ordnance of the Royal Navy. The department was managed by a Director, ...

, responsible for weapons and munitions. He was responsible for the development of quick-firing guns to be used against the growing threat from torpedo boats, and particularly claimed responsibility for removing wooden boarding pikes from navy ships. The Navy did not have responsibility for manufacture and supply of weapons and ammunition, which was in the hands of the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

. Fisher began a long campaign to return this responsibility to the Admiralty, but did not finally succeed until he later became First Sea Lord. He was appointed Aide-de-Camp to the Queen in 1887, and promoted Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarded ...

in August 1890.

Admiral (1890–1902)

From May 1891 to February 1892, Fisher was Admiral Superintendent of the dockyard atPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, where he concerned himself with improving the speed of operations. was built in two years rather than three, while changing a barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

gun on a ship was reduced from a two-day operation to two hours. His example obliged all shipyards, both navy and private, to reduce the time they took to complete a ship, making savings in cost and allowing new designs to enter service more rapidly. He used all the tricks he could devise: an official who refused to step outside his office to personally supervise the work was offered a promotion to the tropics; he would find out the name of one or two men amongst a work crew and then make a point of complimenting them on their work and using their names, giving the impression he knew everyone personally; he took a chair and table into the yard where some operation was to be carried out and declared his intention to stay there until the operation was completed. He observed, ''When you are told a thing is impossible, that there are insuperable objections, then is the time to fight like the devil''.

His next appointment was Third Naval Lord and Controller of the Navy

The post of Controller of the Navy (abbreviated as CofN) was originally created in 1859 when the Surveyor of the Navy's title changed to Controller of the Navy. In 1869 the controller's office was abolished and its duties were assumed by that of ...

, the naval officer with overall responsibility for provision of ships and equipment. He presided over the development of torpedo boat destroyers armed with quick-firing small-calibre guns (called destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s at Fisher's suggestion). A suggestion for the boats was brought to the Admiralty in 1892 by Alfred Yarrow

Sir Alfred Fernandez Yarrow, 1st Baronet, (13 January 1842 – 24 January 1932) was a British shipbuilder who started a shipbuilding dynasty, Yarrow Shipbuilders.

Origins

Yarrow was born of humble origins in East London, the son of Esther ( ...

of shipbuilders Thornycroft and Yarrow, who reported that he had obtained plans of new torpedo boats being built by the French, and he could build a faster boat to defend against them. Torpedo boats had become a major threat, as they were cheap but potentially able to sink the largest battleships, and France had built large numbers of them. The first destroyers were considered a success and more were ordered, but Fisher immediately ran into trouble by insisting that all shipbuilders, not just Yarrow's, should be invited to build boats to Yarrow's design. A similar (though opposite) difficulty with vested interests arose over the introduction of water tube boilers into navy ships, which held out the promise of improved fuel efficiency and greater speed. The first examples were used by Thornycroft and Yarrow in 1892, and then were trialled in the gunboat . However, an attempt to specify similar boilers for new cruisers in 1894 led to questions in the House of Commons, and opposition from shipbuilders who did not want to invest in the new technology. The matter continued for several years after Fisher moved on to a new posting, with a parliamentary enquiry rejecting the new boilers. Eventually the new design was adopted, but only after another eighteen ships had been built using the older design, with consequent poorer performance than necessary.

Fisher was knighted in the Queen's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the reigning British monarch's official birthday by granting various individuals appointment into national or dynastic orders or the award of decorations and medals. The honours are present ...

of 1894 as a Knight Commander of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

, promoted to vice-admiral in 1896, and put in charge of the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

in 1897. In 1898 the Fashoda Crisis

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exp ...

brought the threat of war with France, to which Fisher responded with plans to raid the French West Indies including Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953 in the Salvation Islands ...

prison, and return the "infamous" Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus ( , also , ; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. ...

to France to foment trouble within the French army. It was Fisher's policy to conduct all manoeuvres at full speed while training the fleet, and to expect the best from his crews. He would socialise with junior officers so that they were not afraid to approach him with ideas, or disagree with him when the occasion demanded.

Fisher was chosen by Prime Minister Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

as British naval delegate to the First Hague Peace Convention in 1899. The peace conference had been called by Russia to agree to limits on armaments, but the British position was to reject any proposal which might restrict use of the navy. Fisher's style was to say little in formal meetings, but to lobby determinedly at all informal gatherings. He impressed many by his affability and style, combined with a serious determination to press the British case with everyone he met. The conference ended successfully with limitations only upon dumdum

Expanding bullets, also known colloquially as dumdum bullets, are projectiles designed to expand on impact. This causes the bullet to increase in diameter, to combat over-penetration and produce a larger wound, thus dealing more damage to a li ...

bullets, poison gas and bombings from balloons, and Fisher was rewarded with appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, ''Mediterranean Fleet

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. The important shipping route between India and Britain passed through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, and was considered threatened by France. France was concerned with the route north–south to its colonies in Northern Africa. Fisher retained his flagship from the North American Squadron, , rather than choosing a more powerful but slower traditional battleship, despite criticism from other officers.

His strategy emphasised the importance of striking the first blow, but with an awareness that sunk ships could not easily be replaced, and would replace any officer who could not keep up with the standards he demanded. He gave lectures on naval strategy to which all officers were invited and once again encouraged his officers to bring ideas to him. He offered prizes for essays on tactics and maintained a large tabletop map room with models of all ships in the fleet, where all officers could come to develop tactics. A particular concern was the threat of torpedoes, which Germany had boasted would dispose of the British fleet, and the numerous French torpedo boats. Fisher's innovations were not universally approved, with some senior officers resenting the attention he paid to their juniors, or the pressure he placed on all to improve efficiency.

A programme of realistic exercises was adopted including simulated French raids, defensive manoeuvres, night attacks and blockades, all carried out at maximum speed. He introduced a gold cup for the ship which performed best at gunnery, and insisted upon shooting at greater range and from battle formations. He found that he too was learning some of the complications and difficulties of controlling a large fleet in complex situations, and immensely enjoyed it.

Notes from his lectures indicate that, at the start of his time in the Mediterranean, useful working ranges for heavy guns without telescopic sights were considered to be only 2000 yards, or 3000–4000 yards with such sights, whereas by the end of his time discussion centred on how to shoot effectively at 5000 yards. This was driven by the increasing range of the torpedo, which had now risen to 3000–4000 yards, necessitating ships fighting effectively at greater ranges. At this time he advocated relatively small main armaments on capital ships (some had 15 inch or greater), because the improved technical design of the relatively small (10 inch) modern guns allowed a much greater firing rate and greater overall weight of broadside. The potentially much greater ranges of large guns was not an issue, because no one knew how to aim them effectively at such ranges. He argued that "the design of fighting ships must follow the mode of fighting instead of fighting being subsidiary to and dependent on the design of ships." As regards how officers needed to behave, he commented, " ''Think and act for yourself'' is the motto for the future, not ''Let us wait for orders''."

Lord Hankey

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, (1 April 1877 – 26 January 1963) was a British civil servant who gained prominence as the first Cabinet Secretary and later made the rare transition from the civil service to ministerial office. ...

, then a marine officer serving under Fisher, later commented, "It is difficult for anyone who had not lived under the previous regime to realize what a change Fisher brought about in the Mediterranean fleet. ... Before his arrival, the topics and arguments of the officers messes ... were mainly confined to such matters as the cleaning of paint and brasswork. ... These were forgotten and replaced by incessant controversies on tactics, strategy, gunnery, torpedo warfare, blockade, etc. It was a veritable renaissance and affected every officer in the navy." Lord Charles Beresford

Admiral Charles William de la Poer Beresford, 1st Baron Beresford, (10 February 1846 – 6 September 1919), styled Lord Charles Beresford between 1859 and 1916, was a British admiral and Member of Parliament.

Beresford was the second son of J ...

, later to become a severe critic of Fisher, gave up a plan to return to Britain and enter parliament, because he had "learnt more in the last week than in the last forty years."

Fisher implemented a program of banquets and balls for important dignitaries to improve diplomatic relations. The fleet visited Constantinople, where he had three meetings with the sultan and was awarded the Grand Cordon, Order of Osmanieh in November 1900, and the following year he was promoted to full Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

on 5 November 1901. He lobbied hard with the Admiralty to obtain additional ships and supplies for the Mediterranean squadron. Beresford, who had established a career in politics alongside his naval one, continued a public campaign for greater funding of the fleet, which caused him to come into conflict with the Admiralty. While Fisher agreed with him as to the need for greater funding and instant readiness for war, he chose to stay out of the public debate. However, he maintained a steady confidential correspondence with the journalist Arnold White, providing him with information and advice for a newspaper campaign promoting the needs of the navy. During the course of the correspondence in 1902, Fisher noted that although France was Britain's historical enemy, Britain had considerable common interest with France as a possible ally, whereas growing German activity abroad made her a much more likely enemy.

The correspondence revealed that Fisher remained uncertain how his views were being received at the Admiralty and an uncertainty on his part whether he would receive further promotions. He had already received approaches to become a director of Armstrong Whitworth, of Elswick (then Britain's largest armaments firm), at a considerably larger salary than that of an admiral and with the possibility of building privately new designs of ship which he believed would be needed to maintain the strength of the fleet.

Second Sea Lord: reform of officer training (1902–1904)

In early June 1902 Fisher handed over the command of the Mediterranean Squadron to Admiral Sir Compton Domvile, and returned to the UK to take up the appointment asSecond Naval Lord

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of Time in physics, time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally t ...

in charge of personnel. He was ''read in'' at the Admiralty on 9 June, and took up his duties the following day.

At this time engineering officers, who had become increasingly important in the fleet as it became steadily more dependent upon machinery, were still largely looked down upon by executive (command) officers. Fisher considered it would be better for the navy if the two branches could be merged, as had been done in the past with navigation officers who had similarly once been a completely separate speciality. His solution was to merge the cadet training of ordinary and engineer officers and revise the curriculum so that it provided a suitable grounding to later go on to either path. The proposal was initially resisted by the remainder of the Board of Admiralty, but Fisher convinced them of the benefits of the changes. Objections within the navy as a whole were harder to quell and a campaign once again broke out in newspapers. Fisher was thoroughly aware of the benefits of getting the press on his side and continued to leak information to friendly journalists. Beresford was approached by officers objecting to the changes to act as champion of their cause, but sided with Fisher on this issue.

Training was extended from under two years to four, with the resulting need for more accommodation for cadets. A second cadet establishment, the Royal Naval College, Osborne

The Royal Naval College, Osborne, was a training college for Royal Navy officer cadets on the Osborne House estate, Isle of Wight, established in 1903 and closed in 1921.

Boys were admitted at about the age of thirteen to follow a course lasting ...

, was constructed at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight for the first two years of training, with the last two remaining at Dartmouth. All cadets now received an education in science and technology as it related to life on board a ship as well as navigation and seamanship. Those who went on to be command officers would now have the benefit of improved understanding of their ships while those who became engineers would be better equipped for command. Physical education and sport were to be taught, not only for the benefit of the cadets but also for the future training of ships' crews which were expected to produce sporting teams on good-will visits in foreign ports. Entrance by examination, which biased the intake to those who could obtain special tuition, was replaced with an interview committee tasked with determining the general knowledge of candidates and their reaction to the questions as much as their answers. After the four years, cadets were posted to special training ships for final practical experience before being posted to real command positions. The results of the final examination affected the seniority allotted to each cadet and his chance of future early promotion.

Fisher had described his Selborne-Fisher scheme

The Selborne-Fisher scheme, or Selborne scheme refers to an effort by John Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher, Second Sea Lord, approved by William Palmer, 2nd Earl of Selborne, First Lord of the Admiralty, in 1903 to combine the military (executive) and e ...

as "unstoppable by prejudice, Parliament, Satan or even, beyond all these, the Treasury itself". However his original inclusion of the Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

caused a drastic fall in the number of cadets opting to become officers in that branch of the service. Fisher accordingly was obliged to modify his reforms to exclude the Royal Marines in 1912.

He was appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) in the 1902 Coronation Honours

The 1902 Coronation Honours were announced on 26 June 1902, the date originally set for the coronation of King Edward VII. The coronation was postponed because the King had been taken ill two days before, but he ordered that the honours list shou ...

list on 26 June 1902, and invested as such by King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

at Buckingham Palace on 24 October 1902.

In 1903 he became Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, with as his flagship.

First Sea Lord (1904–1910)

After spending September and the first half of October on the continent Fisher took office as First Sea Lord on 20 October 1904. The appointment came with a house in

After spending September and the first half of October on the continent Fisher took office as First Sea Lord on 20 October 1904. The appointment came with a house in Queen Anne's Gate

Queen Anne’s Gate is a street in Westminster, London. Many of the buildings are Grade I listed, known for their Queen Anne architecture. Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner described the Gate’s early 18th century houses as “the best of thei ...

, but Fisher also leased Langham House, Ham

Langham House is a Grade II-listed house facing Ham Common in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It was built in about 1709 and former home of several notable residents.

Location

Langham House is located on Ham Street, on the west sid ...

where the family lived until his retirement. In June 1905 he was appointed to the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

(OM), in December he was promoted Admiral of the Fleet.

Fisher was brought into the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

to reduce naval budgets, and to reform the navy for modern war. Amidst massive public controversy, he ruthlessly sold off 90 obsolete and small ships and put a further 64 into reserve, describing them as "too weak to fight and too slow to run away", and "a miser's hoard of useless junk". This freed up crews and money to increase the number of large modern ships in home waters. The navy estimate for 1905 was reduced by £3.5 million on the previous year's total of £36.8 million despite new building programs and greatly increased effectiveness. Naval expenditure fell from 1905 to 1907, before rising again. By the end of Fisher's tenure as First Sea Lord expenditure had returned to 1904 levels.

He was a driving force behind the development of the fast, all-big-gun battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, and chaired the Committee on Designs which produced the outline design for the first modern battleship, . His committee also produced a new type of cruiser in a similar style to ''Dreadnought'' with a high speed achieved at the expense of armour protection. This became the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

, the first being . He also encouraged the introduction of submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s into the Royal Navy, and the conversion from a largely coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

-fuelled navy to an oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

-fuelled one. He had a long-running public feud with another admiral, Charles Beresford

Admiral Charles William de la Poer Beresford, 1st Baron Beresford, (10 February 1846 – 6 September 1919), styled Lord Charles Beresford between 1859 and 1916, was a British admiral and Member of Parliament.

Beresford was the second son of ...

.

In his capacity as First Sea Lord, Fisher proposed multiple times to King Edward VII that Britain should take advantage of its naval superiority to "Copenhagen" the German fleet at Kiel – that is, to destroy it with a pre-emptive surprise attack without declaration of war, as the Royal Navy had done against the Danish Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. In his memoirs, Fisher records a conversation where he was informed that "by all from the German Emperor downwards ewas the most hated man in Germany", as the Emperor "had heard of isher'sidea for the "Copenhagening

Copenhagenization is an expression which was coined in the early nineteenth century, and has seen occasional use since. The expression refers to a decisive blow delivered to a potential opponent while being at peace with that nation. It originate ...

" of the German Fleet." Fisher further added that he doubted that the suggestion had leaked out, and believed that "he Emperor

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

only said it because he knew it was what he British

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

ought to have done."

In 1908, he predicted that war between Britain and Germany would occur in October 1914, which later proved accurate, basing his statement on the projected completion of the widening of the Kiel Canal

The Kiel Canal (german: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North- oEast alticSea canal", formerly known as the ) is a long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the N ...

, which would allow Germany to move its large warships safely from the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. He was appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) that year.

On 7 December 1909, he was created Baron Fisher. He took the punning motto "Fear God and dread nought" on his coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

as a reference to ''Dreadnought''.

Before the war (1911–1914)

He retired to

He retired to Kilverstone Hall

Kilverstone Hall is a Grade II listed building in Kilverstone in Norfolk, England.

History

Kilverstone Hall is a country house built in the early 17th century which was passed down the Wright family of Kilverstone. It was greatly enlarged by Jos ...

on 25 January 1911, his 70th birthday.

In 1912, Fisher was appointed chairman of the Royal Commission on Fuel and Engines