Lord Camden CJ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

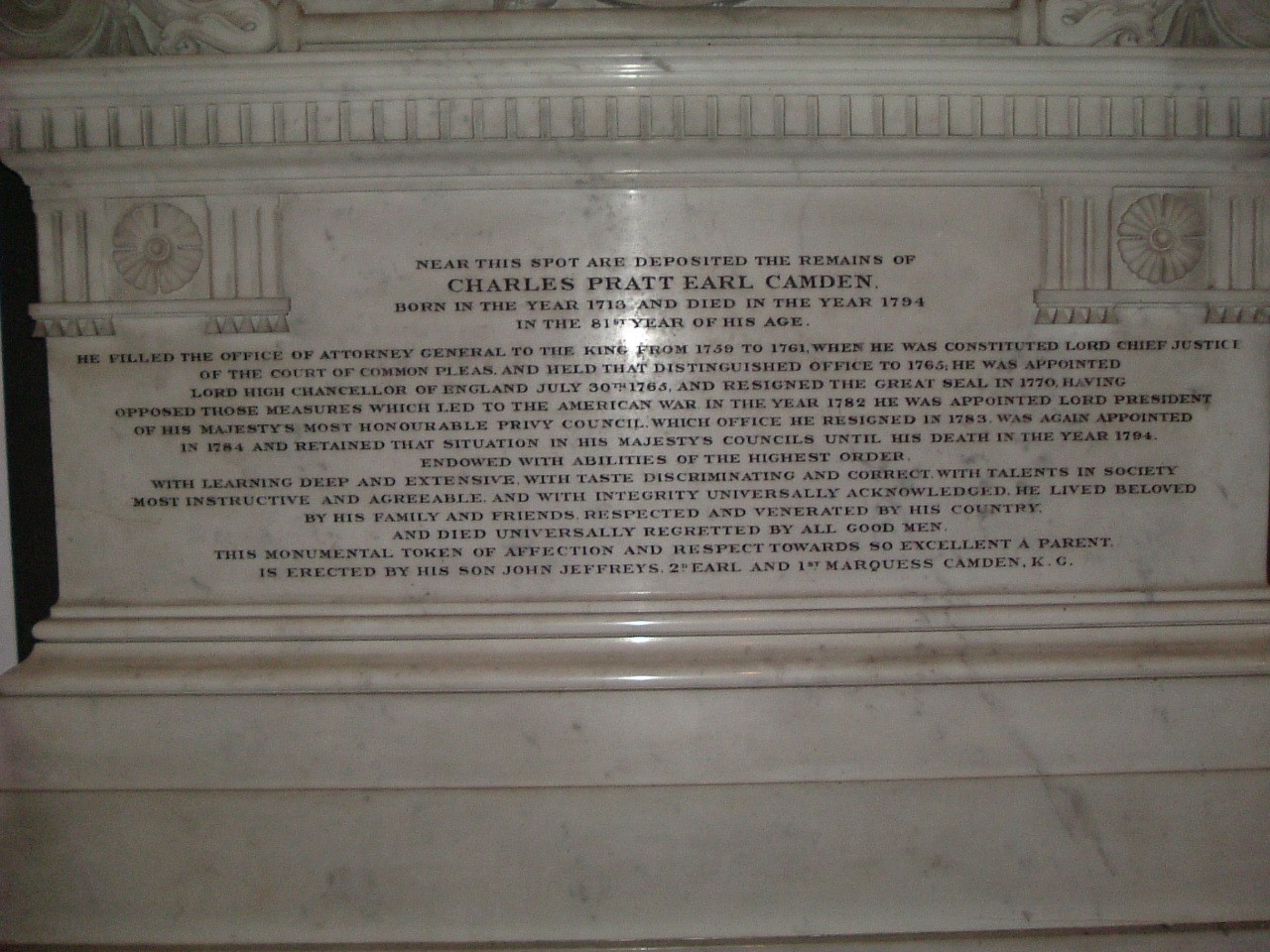

Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden, PC ( baptised 21 March 1714 – 18 April 1794) was an English

By the 20th century, Camden's legal opinions were seen as subservient to Chatham's politics and Camden certainly followed the party line on Wilkes and America. However, his party loyalty was tempered by a self-serving interest in power. He served under five prime ministers and on two occasions clung to office after Chatham had resigned.

In his last years, he took a great interest in the career of Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, his daughter's stepson. Camden, whose own son was not to prove much of a statesman, recognised young Robert's potential and treated him very much as though he was his actual grandson.

In 1788 he obtained an Act of Parliament granting permission to develop some fields he owned just to the north of London. In 1791 he laid out the land in plots and leased them for the construction of 1,400 houses, the beginnings of

By the 20th century, Camden's legal opinions were seen as subservient to Chatham's politics and Camden certainly followed the party line on Wilkes and America. However, his party loyalty was tempered by a self-serving interest in power. He served under five prime ministers and on two occasions clung to office after Chatham had resigned.

In his last years, he took a great interest in the career of Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, his daughter's stepson. Camden, whose own son was not to prove much of a statesman, recognised young Robert's potential and treated him very much as though he was his actual grandson.

In 1788 he obtained an Act of Parliament granting permission to develop some fields he owned just to the north of London. In 1791 he laid out the land in plots and leased them for the construction of 1,400 houses, the beginnings of

Pratt, Charles, first Earl Camden (1714–1794)

, '' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edn, accessed 15 February 2008 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Camden, Charles Pratt, 1st Earl 1714 births 1794 deaths Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Attorneys General for England and Wales Chief Justices of the Common Pleas Earls in the Peerage of Great Britain Peers of Great Britain created by George III English knights Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Lord chancellors of Great Britain Lord Presidents of the Council Whig members of the Parliament of Great Britain Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain People from Kensington Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies People educated at Eton College

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

, judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

and Whig politician who was first to hold the title of Earl Camden. As a lawyer and judge he was a leading proponent of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

, championing the rights of the jury, and limiting the powers of the State in leading cases such as '' Entick v Carrington''.

He held the offices of Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Attorney-General and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, and was a confidant of Pitt the Elder, supporting Pitt in the controversies over John Wilkes and American independence. However, he clung to office himself, even when Pitt was out of power, serving in the cabinet for fifteen years and under five different prime ministers.

During his life, Pratt played a leading role in opposing perpetual copyright

Perpetual copyright can refer to a copyright without a finite term, or to a copyright whose finite term is perpetually extended. Perpetual copyright in the former sense is highly uncommon, as the current laws of all countries with copyright stat ...

, resolving the regency crisis of 1788

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-riv ...

and championing Fox's Libel Bill. He started the development of the settlement that was later to become Camden Town

Camden Town (), often shortened to Camden, is a district of northwest London, England, north of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Camden, and identified in the London Plan as o ...

in London.

Early life

Born inKensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

in 1714, he was a descendant of an old Devon family of high standing, the third son of Sir John Pratt, Chief Justice of the King's Bench

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

in the reign of George I. Charles's mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Rev. Hugh Wilson of Trefeglwys, and the aunt of landscape painter Richard Wilson. He received his early education at Eton, where he became acquainted with William Pitt, and King's College, Cambridge. He had already developed an interest in constitutional law and civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

. In 1734 he became a fellow of his college, and in the following year obtained his degree of BA. Having adopted his father's profession, he had entered the Middle Temple in 1728, and ten years later he was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

.

Early years at the Bar

He practised at first in the courts of common law, travelling also the western circuit. For some years his practice was so limited, and he became so much discouraged that he seriously thought of turning his back on the law and entering the church. He listened, however, to the advice of his friend Sir Robert Henley, a brother barrister, and persevered, working on and waiting for success. Reputedly, once instructed as Henley's junior, Henley feigned illness so that Pratt could lead and earn the credit.Rigg (1896) He was further aided by an advantageous marriage on 5 October 1749 to Elizabeth, daughter of Nicholas Jeffreys of the Priory, Brecknock, by whom he had a son John Jeffreys, his successor in title and estates, and four daughters, of whom the eldest, Frances, married Robert Stewart, 1st Marquess of Londonderry on 7 June 1775. The first case which brought him prominently into notice and gave him assurance of ultimate success was the government prosecution, in 1752, of a bookseller, William Owen. Owen had published a book ''The Case of Alexander Murray, Esq; in an Appeal to the people of Great Britain'' which the House of Commons had, by resolution of the House, condemned as "an impudent, malicious, scandalous and seditious libel". The author had left the country so the weight of the government's censure fell on Owen.Towers (1764) Pratt appeared in Owen's defence and his novel argument was that it was not the sole role of the jury to determine the fact of publication but that it was further their right to assess the intent of alibel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

. In his summing up, the judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

, Lord Chief Justice Sir William Lee directed the jury to find Owen guilty as publication was proved and the intent of the contents was a question of law In law, a question of law, also known as a point of law, is a question that must be answered by applying relevant legal principles to interpretation of the law. Such a question is distinct from a question of fact, which must be answered by reference ...

for the judge, not a question of fact for the jury. The jury disagreed and acquitted Owen. Pratt was appointed King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

in 1755, and knighted in December 1761.

Political career

Since their youthful meeting at Eton, Pitt had continued to consult Pratt on legal and constitutional matters and Pratt became involved in the group that met at the Leicester House home of George Prince of Wales and who were opposed to the government of Prime Minister the Duke of Newcastle. In 1756, Newcastle offered Pratt ajudge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

ship but Pratt preferred to take the role of Attorney General to the Prince of Wales.

In July 1757, Pitt formed a coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

government with Newcastle and insisted on Pratt's appointment as Attorney-General. Pratt was preferred over Solicitor General Charles Yorke. Yorke was the son of Lord Hardwicke

Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, (1 December 16906 March 1764) was an English lawyer and politician who served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain. He was a close confidant of the Duke of Newcastle, Prime Minister between 1754 and 1 ...

, a political ally of Newcastle who, as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

had obstructed Pratt's career in favour of his own son. Though this led to an uncomfortable relationship between the two law officers of the Crown, it led to the landmark Pratt-Yorke opinion of 24 December 1757 whereby the pair distinguished overseas territories acquired by conquest from those acquired by private treaty. They asserted that, while the Crown of Great Britain enjoyed sovereignty over both, only the property of the former was vested in the Crown. Though the original opinion related to the British East India Company, it came to be applied elsewhere in the developing British Empire.

The same year he entered the House of Commons as Member of Parliament (MP) for the borough of Downton in Wiltshire. He sat in Parliament for four years, but did not distinguish himself as a debater. He introduced the Habeas corpus Amendment Bill of 1758, which was intended to extend the writ of '' Habeas corpus'' from criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law i ...

to civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and political cases. Despite Pitt's support, the Bill fell in the House of Lords. At the same time, his professional practice increased, particularly his Chancery

Chancery may refer to:

Offices and administration

* Chancery (diplomacy), the principal office that houses a diplomatic mission or an embassy

* Chancery (medieval office), responsible for the production of official documents

* Chancery (Scotlan ...

practice which made him financially secure and enabled him to purchase the Camden Place estate in Kent.

As Attorney-General, Pratt prosecuted Florence Hensey

Florence Hensey (also Henchy, Henzy; ) was an Irish physician, and a spy for France during the Seven Years' War.

Life

Hensey was born in Kildare about 1714, a son of Florence Henchey of Ballycumeen, County Clare, and his wife Mary; the couple had ...

, an Irishman who had spied for France, and John Shebbeare

John Shebbeare (1709–1788) was a British Tory political satirist.

Life

He was the eldest son of an attorney and corn-factor of Bideford, Devonshire. A hundred and a village in Devon, where the family had owned land, bear their name. Shebbeare ...

, a violent party writer of the day. Shebbeare had published a libel against the government contained in his ''Letters to the People of England'', which were published in 1756–58. As evidence of Pratt's moderation in a period of passionate party warfare and frequent state trials, it is notable that this was the only official prosecution for libel that he started and that he maintained his earlier insistence that the decision lay with the jury. He led for the Crown in the prosecution of Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers for the murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

of a servant, a case that shocked European society.

Wilkes and Entick

Pratt lost his patron when Pitt left office in October 1761 but in January 1762, he resigned from the Commons, was raised to the bench as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, received the customary knighthood and was sworn into thePrivy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

.

The Common Pleas was not an obvious forum for a jurist with constitutional interest, dealing as it did principally with disputes between private parties. However, on 30 April 1763, Member of Parliament John Wilkes was arrest

An arrest is the act of apprehending and taking a person into custody (legal protection or control), usually because the person has been suspected of or observed committing a crime. After being taken into custody, the person can be questi ...

ed under a general warrant for alleged seditious libel in issue No.45 of '' The North Briton''. Pratt freed Wilkes holding that parliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties. ...

gave him immunity from arrest on such a charge. The decision earned Pratt some favour with the radical faction in London and seems to have spurred him, over the summer of that year to encourage juries to award disproportionate and excessive damages to printers unlawfully arrested over the same matter. Wilkes was awarded £1,000 (£127,000 at 2003 prices) and Pratt condemned the use of general warrants for entry and search. Pratt pronounced with decisive and almost passionate energy against their legality, thus giving voice to the strong feeling of the nation and winning for himself an extraordinary degree of popularity as one of the maintainers of English civil liberties. Honours fell thick upon him in the form of addresses from the City of London and many large towns, and of presentations of freedom from various corporate bodies.

In 1762, the home of John Entick

John Entick (c.1703 – May 1773) was an English schoolmaster and author. He was largely a hack writer, working for Edward Dilly, and he padded his credentials with a bogus M.A. and a portrait in clerical dress; some of his works had a more la ...

had been raided by officers of the Crown, searching for evidence of sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, estab ...

. In the case of '' Entick v Carrington'' (1765), Pratt held that the raids were unlawful as they were without authority in statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by le ...

or in common law.Thomas (2008)

The American Stamp Act crisis

On 17 July 1765 Pratt was created Baron Camden, of Camden Place, in Chislehurst, Kent, becoming a member of the House of Lords. Prime Minister Lord Rockingham had unsuccessfully made this, and other appointments, to curry favour with Pitt but Camden was not over-eager to get involved in the crisis surrounding theStamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials i ...

. Camden did attend the Commons on 14 January 1766 and his subsequent speeches on the matter in the Lords are so similar to Pitt's that he had clearly adopted the party line. He was one of only five Lords who voted against the Declaratory Act, a resolution of the House insisting on parliament's right to tax colonies overseas. Camden insisted that taxation was predicated on consent and that consent needed representation. However, when he came to support the government over the Act's repeal, he rather unconvincingly purported to base his opinion on the actual hardship caused by the Act rather than its constitutional basis.

Lord Chancellor

In May 1766, Pitt again became prime minister and advanced Camden from the court of common pleas to take his seat asLord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

on 30 July. Camden managed to negotiate an additional allowance of £1500 and a position for his son John. Camden carried out the role in an efficient manner, without any great legal innovation. He presided over the Court of Chancery from which only one of his decisions was overturned on appeal. He also presided over the judicial functions of the House of Lords

Whilst the House of Lords of the United Kingdom is the upper chamber of Parliament and has government ministers, it for many centuries had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers, for impeachments, ...

where in 1767 he approved Lord Mansfield's ruling that the City of London could not fine dissenters who refused to serve the corporation. Dissenters were in any case prohibited from serving under the Corporation Act 1661. In 1768 in the House of Lords he again sat in a case involving John Wilkes, this time rejecting his appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

and finding that his consecutive, rather than concurrent sentences were lawful. He gave a controversial judgment in the Douglas Peerage case.

"A forty days tyranny"

However, Camden the politician was less of a champion of civil rights than Pratt the judge. The poorharvest

Harvesting is the process of gathering a ripe crop from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper. On smaller farms with minimal mechanization, harvesting is the most labor-i ...

of 1766 led to fears of high grain prices and starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, dea ...

but parliament was prorogued

A legislative session is the period of time in which a legislature, in both parliamentary and presidential systems, is convened for purpose of lawmaking, usually being one of two or more smaller divisions of the entire time between two electio ...

and could not renew the export ban that expired on 26 August. Pitt, with Camden's support, called the Privy Council to issue a royal proclamation on 26 September to prohibit grain exports until parliament met. However, despite Camden's record on civil liberties, this proclamation was unlawful, contrary to art.2 of the Bill of Rights 1689 and both houses of parliament ultimately accused Pitt and Camden of tyranny. Camden pleaded necessity, a justification he had rejected in the Wilkes and Carrington trials, and styled it "a forty days tyranny". Ultimately the government was forced to suppress the parliamentary attacks by an act indemnifying those involved from legal action.

America

In 1767, the cabinet, of which Camden was a member, approvedCharles Townshend

Charles Townshend (28 August 1725 – 4 September 1767) was a British politician who held various titles in the Parliament of Great Britain. His establishment of the controversial Townshend Acts is considered one of the key causes of the Ame ...

's attempt to settle the American protest and revolt over taxation. Benjamin Franklin reportedly observed that it was "internal" taxes that the colonists objected to and Townshend took this to suggest that there would be little opposition to import duties imposed at the ports. Camden's support for the tax proposals would return to embarrass him.

Pitt and his followers had, after their initial opposition, come to support the Declaratory Act of 1766 which asserted Great Britain's sovereignty over the American colonies. Further, continued unrest in America, stemming from Townshend's 1767 taxation scheme, brought a robust response from Pitt and Camden was his spokesman in the Lords. However, towards the end of 1767, Pitt, now raised to the Lords as Earl Chatham, fell ill and the Duke of Grafton stepped in as caretaker. Camden became indecisive in his own political role, writing to Grafton on 4 October 1768:

Pitt resigned on 14 October and Camden, who continued to sit in the cabinet as Lord Chancellor, now took up a position of uncompromising hostility to the governments of Grafton and Lord North on America and on Wilkes. Camden opposed Lord Hillsborough's confrontational approach to the Americas, favouring conciliation and working on the development of reformed tax proposals. Camden personally promised the colonies that no further taxes would be levied, and voted in the cabinet minority who sought to repeal the tea duty.

John Wilkes MP

On 28 March 1768, Wilkes was surprisingly elected as member for Middlesex, much to Grafton's distaste. Grafton canvassed Camden on whether Wilkes could be removed from parliament and Camden responded that, under theparliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties. ...

of the House to regulate its own membership, Wilkes could, though lawfully elected, be lawfully expelled. However, Camden saw that this was only likely to lead to Wilkes's re-election and an escalating crisis. The cabinet decided to seek Wilkes's expulsion but Camden was not content with the policy. By the end of 1769, he was in open opposition to the government and was making little contribution to discussions in cabinet. Only Royal pressure kept him in post. However, by the beginning of 1770, Chatham had returned to the fray, opposing government policies on Wilkes and America. On 9 January 1770, Chatham moved a motion opposing the government's policies and Camden stepped down from the woolsack to give a speech in support of the motion. However, he did not resign as Lord Chancellor until King George III, outraged by his conduct, demanded his dismissal on 17 January. He seems also to have resigned as a Chancery judge in late 1769.

Working Lord

Into opposition

Chatham, Rockingham and Grenville were expected to combine to bring down Grafton, when it was expected that Lord Camden would return to the woolsack. However, though Grafton resigned, Lord North managed to form a successor administration and Camden was left to the opposition, continuing to sit in the Lords. From 1770 onwards, Chatham neglected parliamentary attendance and left leadership of the house to Lord Shelburne with whom Camden could manage only the coolest of relationships. During 1770–71, Camden tussled with Lord Mansfield over the law oflibel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, Camden maintaining that the jury should not only decide whether the work in question was published but also whether the words themselves were defamatory or innocent. He opposed the extension of the Royal Marriages Act 1772 to all descendants of King George II, believing it to be impractical. In 1774, in the House of Lords appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

in the case of '' Donaldson v Beckett'', Camden spoke against the concept of perpetual copyright

Perpetual copyright can refer to a copyright without a finite term, or to a copyright whose finite term is perpetually extended. Perpetual copyright in the former sense is highly uncommon, as the current laws of all countries with copyright stat ...

for fear of inhibiting the advancement of learning. This was a key influence on the ultimate rejection of that year's Booksellers' Bill

The Booksellers's Bill was a 1774 bill introduced into the Parliament of Great Britain in the wake of the important copyright case of '' Donaldson v. Beckett''.

In ''Donaldson'' a perpetual common law copyright was denied to booksellers and it was ...

.

The American crisis of 1774

The year 1774 brought a renewed crisis over America. The Boston Tea Party in 1773 led Lord North to seek a blockade of the city through the Boston Port Bill. Camden roundly criticised the taxes that had led to the American protests, as he had opposed them in Cabinet from 1767 to 1769, but was reminded that he was Lord Chancellor when they were imposed. The Chathamite faction went on to support the Bill and further to support the Massachusetts Government Act, Camden's inherentpatriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

bringing him into line. However, by May, fears that the Bill would focus and strengthen American resistance led Camden to oppose the measure.

On 16 February 1775, Camden made his major speech on the crisis, opposing public opinion and the New England Trade and Fishery Bill

The Restraining Acts of early 1775 were two Acts passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, which limited colonial trade in response to both increasing and spreading civil disobedience in Massachusetts and New England, and similar trade restriction ...

, a speech often believed to have been drafted in collaboration with Benjamin Franklin for an American audience. Camden invoked John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

's dictum that resistance to tyranny was justified and called the Bill:

Thomas Hutchinson observed:

How Camden voted on the Quebec Act is unknown but in May 1775, and in response to a petition from a small number of settlers, he unsuccessfully moved its repeal. However, he seems to have been in the grip of a conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

that the Act's ulterior objective was to create an army of militant Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in Canada to suppress the Protestant British colonists.

American War of Independence

TheAmerican War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

broke out in 1775 and Chatham's faction were dismayed. Their official line was to advocate mediation, refusing to think of either American independence or continued English hegemony. Camden continued to speak on the dilemma in parliament. He continued steadfastly to oppose the taxation of the American colonists, and signed, in 1778, the protest of the Lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

* Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 1 ...

in favour of an address to the King on the subject of the manifesto of the commissioners to America. In 1782 he was appointed Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the ...

under the Rockingham-Shelburne administration, supporting the government economic programme and anti-corruption drive, and championing repeal of the Declaratory Act 1720

An Act for the better securing the dependency of the Kingdom of Ireland on the Crown of Great Britain ( 6. Geo. I, c. 5) was a 1719 Act passed by the Parliament of Great Britain which declared that it had the right to pass laws for the Kingdom of ...

in Ireland. Once Rockingham died in July, the Chathamite residue could only lose the Commons vote over the American peace terms the following February. Camden resigned and persuaded Shelburne to do the same.

The Younger Pitt

Camden was a leading opponent of the ensuing Fox-North Coalition, denouncing it forpatronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

and leading the opposition to Fox's East India Bill

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the f ...

that brought down the administration on 9 December 1783. William Pitt the Younger, the son of his former patron, came to power and within a few months, Camden was reinstated as Lord President, holding the post until his death. He was created Earl Camden on 13 May 1786 and granted a further peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

as Viscount Bayham to lend his son a courtesy title

A courtesy title is a title that does not have legal significance but rather is used through custom or courtesy, particularly, in the context of nobility, the titles used by children of members of the nobility (cf. substantive title).

In some co ...

.

Camden took an animated part in the debates on important public matters until within two years of his death, in particular supporting Pitt's 1785 Parliamentary Reform Bill and the Irish trade proposals that same year. Camden continued to attend cabinet meetings and, after he moved to Hill Street, Berkeley Square on account of his ill health, cabinet meetings were sometimes held at his home.

Regency crisis of 1788

In November 1788, King George III fell ill and insanity was feared. Lord ChancellorThurlow Thurlow is a surname and a given name, and may refer to:

Surname:

* Alan Thurlow (born 1946), English organist

* Bryan Thurlow (1936–2002), English professional football player

* Clifford Thurlow (born 1952), British biographer

* Edward Thurlow, ...

hesitated over what action to take, thereby precipitating the regency crisis of 1788

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-riv ...

. As Lord President, Camden led the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

examination of the King's doctors' opinions. With Thurlow unwilling to lead the legislature, Camden grasped the challenge of inviting parliament to appoint a regent, in the face of the opposition's support for the automatic appointment of their ally the Prince of Wales. Camden's resolution that appointment rested with parliament was carried in the Lords by 99 votes to 66 on 23 December 1788. Moreover, on 22 January 1789, Camden's motion to appoint the Prince of Wales, but with restrictions in case of the King's recovery, was carried by 94 to 68 votes. The King recovered the following month before the Regency Bill contained the force of law.

Fox's Libel Act

To the last, Camden zealously defended his early views on the functions of juries, especially of their right to decide on all questions of libel. In the Lords debate on the second reading of the Libel Act 1792 on 16 May, Camden contended thatintention

Intentions are mental states in which the agent commits themselves to a course of action. Having the plan to visit the zoo tomorrow is an example of an intention. The action plan is the ''content'' of the intention while the commitment is the ''a ...

was an essential element of libel and should be decided by the jury as in murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

cases. Broadening the legal argument to the constitutional and political Camden charged press freedom

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerci ...

to the hands of the jury as the representatives of the people. The judges he held were too prone to government pressure to guarantee essential freedoms. Despite the unanimous opposition of the Law Lords, Camden's speech helped secure a majority of 57 to 32.

Reputation and legacy

Camden was short in stature but of a fine physique. For recreation he enjoyed music, theatre, romantic fiction,conversation

Conversation is interactive communication between two or more people. The development of conversational skills and etiquette is an important part of socialization. The development of conversational skills in a new language is a frequent focus ...

and food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is inge ...

. His vices were sloth and gluttony rather than womanising or gambling. The Earl Camden died in London on 18 April 1794. His remains were interred in Seal church in Kent. Camden died a wealthy man, much of his wealth deriving from his wife.

Both Lord Campbell and Sir William Holdsworth

Sir William Searle Holdsworth (7 May 1871 – 2 January 1944) was an English legal historian and Vinerian Professor of English Law at Oxford University, amongst whose works is the 17-volume ''History of English Law''.

Biography

Holdsworth w ...

held Camden a great Lord Chancellor.

By the 20th century, Camden's legal opinions were seen as subservient to Chatham's politics and Camden certainly followed the party line on Wilkes and America. However, his party loyalty was tempered by a self-serving interest in power. He served under five prime ministers and on two occasions clung to office after Chatham had resigned.

In his last years, he took a great interest in the career of Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, his daughter's stepson. Camden, whose own son was not to prove much of a statesman, recognised young Robert's potential and treated him very much as though he was his actual grandson.

In 1788 he obtained an Act of Parliament granting permission to develop some fields he owned just to the north of London. In 1791 he laid out the land in plots and leased them for the construction of 1,400 houses, the beginnings of

By the 20th century, Camden's legal opinions were seen as subservient to Chatham's politics and Camden certainly followed the party line on Wilkes and America. However, his party loyalty was tempered by a self-serving interest in power. He served under five prime ministers and on two occasions clung to office after Chatham had resigned.

In his last years, he took a great interest in the career of Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, his daughter's stepson. Camden, whose own son was not to prove much of a statesman, recognised young Robert's potential and treated him very much as though he was his actual grandson.

In 1788 he obtained an Act of Parliament granting permission to develop some fields he owned just to the north of London. In 1791 he laid out the land in plots and leased them for the construction of 1,400 houses, the beginnings of Camden Town

Camden Town (), often shortened to Camden, is a district of northwest London, England, north of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Camden, and identified in the London Plan as o ...

.

The town of Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, Maine in the United States, was named for him in 1791. This is one of several cities, towns, and counties bearing his name, including Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, South Carolina, Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, North Carolina, and Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, New Jersey, as well as Camden Counties in New Jersey (of which the eponymous city is the seat and largest city), Missouri and Georgia. In turn, Camden, South Carolina gave its name both to the Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces under Lieutenant General ...

and Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, Alabama. Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, Tennessee was named for the battle, and Camden

Camden may refer to:

People

* Camden (surname), a surname of English origin

* Camden Joy (born 1964), American writer

* Camden Toy (born 1957), American actor

Places Australia

* Camden, New South Wales

* Camden, Rosehill, a heritage res ...

, Arkansas took its name from the town in Alabama. Furthermore, Pratt Street, a major thoroughfare in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

, is also named partially after him.

Cases

*''Chapman v Pickersgill

Chapman may refer to:

Businesses

* Chapman Entertainment, a former British television production company

* Chapman Guitars, a guitar company established in 2009 by Rob Chapman

* Chapman's, a Canadian ice cream and ice water products manufacturer ...

'' (1762) 2 Wilson 145, 146, "I wish never to hear this objection again. This action is for a tort: torts are infinitely various; not limited or confined, for there is nothing in nature but may be an instrument of mischief".

*'' Entick v Carrington'' (1765) 19 Howell's State Trials 1030, right to security and property without arbitrary official interference

*'' Donaldson v Beckett'' 98 ER 257 (1774)

References

Bibliography

* *Campbell, J. L. (1851a) ''Life of Lord Chancellor Camden from his Birth till the Death of George II'', Blanchard & Lea *— (1851b) ''Continuation of the Life of Lord Chancellor Camden till he became and Ex-Chancellor'', Blanchard & Lea *Eeles, H. S. (1934) ''Lord Chancellor Camden and his Family'' * ( Google Books) * * *Thomas, P. D. G. (2008)Pratt, Charles, first Earl Camden (1714–1794)

, '' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, online edn, accessed 15 February 2008 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Camden, Charles Pratt, 1st Earl 1714 births 1794 deaths Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Attorneys General for England and Wales Chief Justices of the Common Pleas Earls in the Peerage of Great Britain Peers of Great Britain created by George III English knights Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Lord chancellors of Great Britain Lord Presidents of the Council Whig members of the Parliament of Great Britain Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain People from Kensington Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies People educated at Eton College