Longitude Problem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the

In 1608 a patent was submitted to the government in the Netherlands for a refracting telescope. The idea was picked up by, among others,

In 1608 a patent was submitted to the government in the Netherlands for a refracting telescope. The idea was picked up by, among others,

The development of the telescope and accurate clocks increased the range of methods that could be used to determine longitude. With one exception (

The development of the telescope and accurate clocks increased the range of methods that could be used to determine longitude. With one exception ( Local noon is defined as the time at which the Sun is at the highest point in the sky. This is hard to determine directly, as the apparent motion of the Sun is nearly horizontal at noon. The usual approach was to take the mid-point between two times at which the Sun was at the same altitude. With an unobstructed horizon, the mid-point between sunrise and sunset could be used. At night, local time could be obtained from the apparent rotation of the stars around the celestial pole, either measuring the altitude of a suitable star with a

Local noon is defined as the time at which the Sun is at the highest point in the sky. This is hard to determine directly, as the apparent motion of the Sun is nearly horizontal at noon. The usual approach was to take the mid-point between two times at which the Sun was at the same altitude. With an unobstructed horizon, the mid-point between sunrise and sunset could be used. At night, local time could be obtained from the apparent rotation of the stars around the celestial pole, either measuring the altitude of a suitable star with a

"Lunars" or lunar distances were an early proposal for the calculation of longitude, having been first made practical by

"Lunars" or lunar distances were an early proposal for the calculation of longitude, having been first made practical by

Frederick J. Pohl and Captain Leonard B. Loeb, April 1957, Proceedings, Vol. 83/4/650Cited in: The method was published by Johannes Werner in 1514, and discussed in detail by

A. Davies, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 118, No. 3 (Sep., 1952), pp. 331-337 putting his calculation within 5° of its actual location. The second one was off by a significant amount, blamed on the inaccurate ephemerides of Regiomontanus. Accuracy improved as astronomers and navigators used better methods and instruments. Observatories published ephemerides using better observations and predictions.

Galileo's method required a telescope, as the moons are not visible to the naked eye. For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship. This was later replaced with the idea of a pair of nested hemispheric shells separated by a bath of oil. This would provide a platform that would allow the observer to remain stationary as the ship rolled beneath him, in the manner of a

Galileo's method required a telescope, as the moons are not visible to the naked eye. For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship. This was later replaced with the idea of a pair of nested hemispheric shells separated by a bath of oil. This would provide a platform that would allow the observer to remain stationary as the ship rolled beneath him, in the manner of a

Measurements of longitude on land and sea complemented one another. As Edmond Halley pointed out in 1717, "But since it would be needless to enquire exactly what longitude a ship is in, when that of the port to which she is bound is still unknown it were to be wisht that the princes of the earth would cause such observations to be made, in the ports and on the principal head-lands of their dominions, each for his own, as might once for all settle truly the limits of the land and sea." But determinations of longitude on land and sea did not develop in parallel.

On land the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid-18th century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2–3°. By the 1720s errors were consistently less than 1°.

At sea during the same period, the situation was very different. Two problems proved intractable. The first was the need for immediate results. On land, an astronomer at, say, Cambridge Massachusetts could wait for the next lunar eclipse that would be visible both at Cambridge and in London; set a pendulum clock to local time in the few days before the eclipse; time the events of the eclipse; send the details across the Atlantic and wait weeks or months to compare the results with a London colleague who had made similar observations; calculate the longitude of Cambridge; then send the results for publication, which might be a year or two after the eclipse. And if either Cambridge or London had no visibility because of cloud, wait for the next eclipse. The marine navigator needed the results quickly. The second problem was the marine environment. Making accurate observations in an ocean swell is much harder than on land, and pendulum clocks do not work well in these conditions. Thus longitude at sea could only be estimated from

Measurements of longitude on land and sea complemented one another. As Edmond Halley pointed out in 1717, "But since it would be needless to enquire exactly what longitude a ship is in, when that of the port to which she is bound is still unknown it were to be wisht that the princes of the earth would cause such observations to be made, in the ports and on the principal head-lands of their dominions, each for his own, as might once for all settle truly the limits of the land and sea." But determinations of longitude on land and sea did not develop in parallel.

On land the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid-18th century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2–3°. By the 1720s errors were consistently less than 1°.

At sea during the same period, the situation was very different. Two problems proved intractable. The first was the need for immediate results. On land, an astronomer at, say, Cambridge Massachusetts could wait for the next lunar eclipse that would be visible both at Cambridge and in London; set a pendulum clock to local time in the few days before the eclipse; time the events of the eclipse; send the details across the Atlantic and wait weeks or months to compare the results with a London colleague who had made similar observations; calculate the longitude of Cambridge; then send the results for publication, which might be a year or two after the eclipse. And if either Cambridge or London had no visibility because of cloud, wait for the next eclipse. The marine navigator needed the results quickly. The second problem was the marine environment. Making accurate observations in an ocean swell is much harder than on land, and pendulum clocks do not work well in these conditions. Thus longitude at sea could only be estimated from

The second method was the use of a chronometer. Many, including

The second method was the use of a chronometer. Many, including

The method was soon in practical use for longitude determination, in particular by the U.S. Coast Survey, and over longer and longer distances as the telegraph network spread across North America. Many technical challenges were dealt with. Initially operators sent signals manually and listened for clicks on the line and compared them with clock ticks, estimating fractions of a second. Circuit breaking clocks and pen recorders were introduced in 1849 to automate these process, leading to great improvements in both accuracy and productivity. With the establishment of an observatory in

The method was soon in practical use for longitude determination, in particular by the U.S. Coast Survey, and over longer and longer distances as the telegraph network spread across North America. Many technical challenges were dealt with. Initially operators sent signals manually and listened for clicks on the line and compared them with clock ticks, estimating fractions of a second. Circuit breaking clocks and pen recorders were introduced in 1849 to automate these process, leading to great improvements in both accuracy and productivity. With the establishment of an observatory in

See page 56

/ref> In 1911 the French determined the difference of longitude between

Board of Longitude Collection, Cambridge Digital Library

The NavList community: devoted to the history, preservation, and practice of traditional navigation techniques

PBS Nova Online: ''Lost at Sea, the Search for Longitude''

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Longitude

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

(the east-west position) of any given place on Earth. The measurement of longitude is important to both cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

and navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

. In particular, for safe ocean navigation, knowledge of both latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and longitude is required, however latitude can be determined with good accuracy with local astronomical observations.

Finding an accurate and practical method of determining longitude took centuries of study and invention by some of the greatest scientists and engineers. Determining longitude relative to the meridian through some fixed location requires that observations be tied to a time scale that is the same at both locations, so the longitude problem reduces to finding a way to coordinate clocks at distant places. Early approaches used astronomical events that could be predicted with great accuracy, such as eclipses, and building clocks, known as chronometers, that could keep time with sufficient accuracy while being transported great distances by ship.

John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

's invention of a chronometer that could keep time at sea with sufficient accuracy to be practical for determining longitude was recognized in 1773 as first enabling determination of longitude at sea. Later methods used the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

and then radio to synchronize clocks. Today the problem of longitude has been solved to centimeter accuracy through satellite navigation

A satellite navigation or satnav system is a system that uses satellites to provide autonomous geopositioning. A satellite navigation system with global coverage is termed global navigation satellite system (GNSS). , four global systems are ope ...

.

Longitude before the telescope

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; ; – ) was an Ancient Greek polymath: a Greek mathematics, mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theory, music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of A ...

in the 3rd century BC first proposed a system of latitude and longitude for a map of the world. His prime meridian (line of longitude) passed through Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

, while his parallels (lines of latitude) were not regularly spaced, but passed through known locations, often at the expense of being straight lines. By the 2nd century BC Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

was using a systematic coordinate system, based on dividing the circle into 360°, to uniquely specify places on Earth. So longitudes could be expressed as degrees east or west of the primary meridian, as is done today (though the primary meridian is different). He also proposed a method of determining longitude by comparing the local time of a lunar eclipse at two different places, to obtain the difference in longitude between them. This method was not very accurate, given the limitations of the available clocks, and it was seldom done – possibly only once, using the Arbela eclipse of 330 BC. But the method is sound, and this is the first recognition that longitude can be determined by accurate knowledge of time.

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, in the 2nd century AD, based his mapping system on estimated distances and directions reported by travellers. Until then, all maps had used a rectangular grid with latitude and longitude as straight lines intersecting at right angles. For large areas this leads to unacceptable distortion, and for his map of the inhabited world, Ptolemy used projections (to use the modern term) with curved parallels that reduced the distortion. No maps (or manuscripts of his work) exist that are older than the 13th century, but in his ''Geography'' he gave detailed instructions and latitude and longitude coordinates for hundreds of locations that are sufficient to re-create the maps. While Ptolemy's system is well-founded, the actual data used are of very variable quality, leading to many inaccuracies and distortions. Apart from the difficulties in estimating rectilinear distances and directions, the most important of these is a systematic over-estimation of differences in longitude. Thus from Ptolemy's tables, the difference in Longitude between Gibraltar and Sidon is 59° 40' 0', compared to the modern value of 40° 23'0', about 48% too high. Russo (2013) has analysed these discrepancies, and concludes that much of the error arises from Ptolemy's underestimate of the size of the Earth, compared with the more accurate estimate of Eratosthenes – the equivalent of 500 stadia to the degree rather than 700. Given the difficulties of astronomical measures of longitude in classical times, most if not all of Ptolemy's values would have been obtained from distance measures and converted to longitude using the 500 value.

Ancient Hindu astronomers were aware of the method of determining longitude from lunar eclipses, assuming a spherical Earth. The method is described in the '' Sûrya Siddhânta'', a Sanskrit treatise on Indian astronomy thought to date from the late 4th century or early 5th century AD. Longitudes were referred to a prime meridian passing through Avantī, the modern Ujjain

Ujjain (, , old name Avantika, ) or Ujjayinī is a city in Ujjain district of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It is the fifth-largest city in Madhya Pradesh by population and is the administrative as well as religious centre of Ujjain ...

. Positions relative to this meridian were expressed in terms of length or time differences, but degrees were not used in India at this time. It is not clear whether this method was put into practice.

Islamic scholars knew the work of Ptolemy from at least the 9th century AD, when the first translation of his ''Geography'' into Arabic was made. He was held in high regard, although his errors were known. One of their developments was to add more locations to Ptolemy's geographical tables with latitudes and longitudes, and in some cases improving the accuracy. The methods used to determine most of the longitudes are not given, but a few accounts do give details. Simultaneous observations of two lunar eclipses at two locations were recorded by al-Battānī in 901, comparing Antakya

Antakya (), Turkish form of Antioch, is a municipality and the capital Districts of Turkey, district of Hatay Province, Turkey. Its area is . Prior to the devastating 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquakes, 2023 earthquakes, its population was recorded ...

with Raqqa

Raqqa (, also , Kurdish language, Kurdish: ''Reqa'') is a city in Syria on the North bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine city and b ...

, determining the difference in longitude between the two cities with an error less than 1°. This is considered the best that can be achieved with the methods then available – observation of the eclipse with the naked eye, and determination of local time using an astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

to measure the altitude of a suitable "clock star". Al-Bīrūnī, early in the 11th century AD, also used eclipse data, but developed an alternative method involving an early form of triangulation. For two locations differing in both longitude and latitude, if the latitudes and the distance between them are known, as well as the size of the earth, it is possible to calculate the difference in longitude. With this method, al-Bīrūnī estimated the longitude difference between Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

and Ghazni

Ghazni (, ), historically known as Ghaznayn () or Ghazna (), also transliterated as Ghuznee, and anciently known as Alexandria in Opiana (), is a city in southeastern Afghanistan with a population of around 190,000 people. The city is strategica ...

using distance estimates from travellers over two different routes (and with a somewhat arbitrary adjustment for the crookedness of the roads). His result for the longitude difference between the two cities differs by about 1° from the modern value. Mercier (1992) notes that this is a substantial improvement over Ptolemy, and that a comparable further improvement in accuracy would not occur until the 17th century in Europe.

While knowledge of Ptolemy (and more generally of Greek science and philosophy) was growing in the Islamic world, it was declining in Europe. John Kirtland Wright

John Kirtland Wright (1891–1969) was an American geographer, notable for his cartography, geosophy, and study of the history of geographical thought. He was the son of classical scholar John Henry Wright and novelist Mary Tappan Wright, and th ...

's (1925) summary is bleak: "We may pass over the mathematical geography of the Christian period n Europebefore 1100; no discoveries were made, nor were there any attempts to apply the results of older discoveries. ... Ptolemy was forgotten and the labors of the Arabs in this field were as yet unknown". Not all was lost or forgotten; Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

in his ''De natura rerum'' affirms the sphericity of the earth. But his arguments are those of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, taken from Pliny. Bede adds nothing original.

There is more of note in the later medieval period. Wright (1923) cites a description by Walcher of Malvern of a lunar eclipse in Italy (October 19, 1094), which occurred shortly before dawn. On his return to England, he compared notes with other monks to establish the time of their observation, which was before midnight. The comparison was too casual to allow a measurement of longitude differences, but the account shows that the principle was still understood. In the 12th century, astronomical tables were prepared for a number of European cities, based on the work of al-Zarqālī in Toledo. These had to be adapted to the meridian of each city, and it is recorded that the lunar eclipse of September 12, 1178 was used to establish the longitude differences between Toledo, Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

s, and Hereford

Hereford ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of the ceremonial county of Herefordshire, England. It is on the banks of the River Wye and lies east of the border with Wales, north-west of Gloucester and south-west of Worcester. With ...

. The Hereford tables also added a list of over 70 locations, many in the Islamic world, with their longitudes and latitudes. These represent a great improvement on the similar tabulations of Ptolemy. For example, the longitudes of Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ) is an Autonomous communities of Spain#Autonomous cities, autonomous city of Spain on the North African coast. Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Ceuta is one of th ...

and Tyre are given as 8° and 57° (east of the meridian of the Canary Islands), a difference of 49°, compared to the modern value of 40.5°, an overestimate of less than 20%. In general, the later medieval period showed increasing interest in geography, and a willingness to make observations stimulated by an increase in travel (including pilgrimages and the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

) and by the availability of Islamic sources from Spain and North Africa At the end of the medieval period, Ptolemy's work became directly available with the translations made in Florence at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century.

The 15th and 16th centuries were the time of Portuguese and Spanish voyages of discovery and conquest. In particular, the arrival of Europeans in the New World led to questions of where they actually were. Christopher Columbus made two attempts to discover his longitude by observing lunar eclipses. The first was on Saona Island, now in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

, during his second voyage. He wrote: "In the year 1494, when I was in Saona Island, which stands at the eastern tip of Española island .e. Hispaniola">Hispaniola.html" ;"title=".e. Hispaniola">.e. Hispaniola there was a lunar eclipse on September the 14th, and we noticed that there was a difference of more than five hours and a half between there [Saona] and Cape S.Vincente, in Portugal". He was unable to compare his observations with ones in Europe, and it is assumed that he used astronomical tables for reference. The second attempt was on the north coast of Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

on February 29, 1504, during his fourth voyage. His results were highly inaccurate, with longitude errors of 13 and 38° W respectively. Randles (1985) documents longitude measurement by the Portuguese and Spanish between 1514 and 1627 both in the Americas and Asia, with errors ranging from 2° to 25°.

Telescopes and clocks

In 1608 a patent was submitted to the government in the Netherlands for a refracting telescope. The idea was picked up by, among others,

In 1608 a patent was submitted to the government in the Netherlands for a refracting telescope. The idea was picked up by, among others, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

who made his first telescope the following year, and began his series of astronomical discoveries that included the satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, and the resolution of the Milky Way into individual stars. Over the next half century, improvements in optics and the use of calibrated mountings, optical grids, and micrometers to adjust positions transformed the telescope from an observation device to an accurate measurement tool. It also greatly increased the range of events that could be observed to determine longitude.

The second important technical development for longitude determination was the pendulum clock

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dep ...

, patented by Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

in 1657. This gave an increase in accuracy of about 30-fold over previous mechanical clocks – the best pendulum clocks were accurate to about 10 seconds per day. From the start, Huygens intended his clocks to be used for determination of longitude at sea. However, pendulum clocks did not tolerate the motion of a ship sufficiently well, and after a series of trials it was concluded that other approaches would be needed. The future of pendulum clocks would be on land. Together with telescopic instruments, they would revolutionise observational astronomy and cartography in the coming years. Huygens was also the first to use a balance spring as oscillator in a working clock, and this allowed accurate portable timepieces to be made. But it was not until the work of John Harrison that such clocks became accurate enough to be used as marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

s.

Methods of determining longitude

magnetic declination

Magnetic declination (also called magnetic variation) is the angle between magnetic north and true north at a particular location on the Earth's surface. The angle can change over time due to polar wandering.

Magnetic north is the direction th ...

) they all depend on a common principle, which was to determine an absolute time from an event or measurement and to compare the corresponding local time at two different locations. (Absolute here refers to a time that is the same for an observer anywhere on Earth.) Each hour of difference of local time corresponds to a 15 degrees change of longitude (360 degrees divided by 24 hours).

Local noon is defined as the time at which the Sun is at the highest point in the sky. This is hard to determine directly, as the apparent motion of the Sun is nearly horizontal at noon. The usual approach was to take the mid-point between two times at which the Sun was at the same altitude. With an unobstructed horizon, the mid-point between sunrise and sunset could be used. At night, local time could be obtained from the apparent rotation of the stars around the celestial pole, either measuring the altitude of a suitable star with a

Local noon is defined as the time at which the Sun is at the highest point in the sky. This is hard to determine directly, as the apparent motion of the Sun is nearly horizontal at noon. The usual approach was to take the mid-point between two times at which the Sun was at the same altitude. With an unobstructed horizon, the mid-point between sunrise and sunset could be used. At night, local time could be obtained from the apparent rotation of the stars around the celestial pole, either measuring the altitude of a suitable star with a sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of cel ...

, or the transit of a star across the meridian using a transit instrument.

To determine the measure of absolute time, lunar eclipses continued to be used. Other proposed methods included:

Lunar distances

"Lunars" or lunar distances were an early proposal for the calculation of longitude, having been first made practical by

"Lunars" or lunar distances were an early proposal for the calculation of longitude, having been first made practical by Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

in his 1474 ''Ephemerides Astronomicae''. This almanac is one of the sources used by Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci ( , ; 9 March 1454 – 22 February 1512) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Florence for whom "Naming of the Americas, America" is named.

Vespucci participated in at least two voyages of the A ...

in his landmark longitude calculations he made on August 23, 1499 and September 15, 1499 as he explored South America.Americo Vespucio—Pioneer Celo-Navigator and GeographerFrederick J. Pohl and Captain Leonard B. Loeb, April 1957, Proceedings, Vol. 83/4/650Cited in: The method was published by Johannes Werner in 1514, and discussed in detail by

Petrus Apianus

Petrus Apianus (April 16, 1495 – April 21, 1552), also known as Peter Apian, Peter Bennewitz, and Peter Bienewitz, was a German humanist, known for his works in mathematics, astronomy and cartography. His work on " cosmography", the field that d ...

in 1524.

The lunar distance method depends on the motion of the Moon relative to the "fixed" stars, which completes a 360° circuit in 27.3 days on average (a lunar month), giving an observed movement of just over 0.5°/hour. Thus an accurate measurement of the angle is required, since 2 minute of arc (1/30°) difference in the angle between the Moon and the selected star corresponds to a 1° 0' difference in the longitude: at the equator. The method also required accurate tables printed before an observation, complicated by calculations to account for parallax and the irregularity of the orbit of the Moon. Neither measuring instruments nor astronomical tables were accurate enough in the early 16th century. Vespucci's first attempt to use the method placed him at 82.5° west of Cadiz,The "First" Voyage of Amerigo Vespucci in 1497-8A. Davies, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 118, No. 3 (Sep., 1952), pp. 331-337 putting his calculation within 5° of its actual location. The second one was off by a significant amount, blamed on the inaccurate ephemerides of Regiomontanus. Accuracy improved as astronomers and navigators used better methods and instruments. Observatories published ephemerides using better observations and predictions.

The Nautical Almanac

''The Nautical Almanac'' has been the familiar name for a series of official British almanacs published under various titles since the first issue of ''The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris'', for 1767: this was the first nautical alm ...

was published in the UK beginning in 1767 and the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac

''The American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac'' was published for the years 1855 to 1980, containing information necessary for astronomers, surveyors, and navigators. It was based on the original British publication, '' The Nautical Almanac and Ast ...

starting in 1852; both included lunar distances and moon culminations.

Moon culminations

Moonculmination

In observational astronomy, culmination is the passage of a celestial object (such as the Sun, the Moon, a planet, a star, constellation or a deep-sky object) across the observer's local meridian. These events are also known as meridian tran ...

s are performed like a lunar distance, but the calculation is generally simpler. For a culmination, the observer simply records the time of the event and compares it with the reference time in an ephemeris

In astronomy and celestial navigation, an ephemeris (; ; , ) is a book with tables that gives the trajectory of naturally occurring astronomical objects and artificial satellites in the sky, i.e., the position (and possibly velocity) over tim ...

table, correcting for refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

and other errors. This method was established by Nathaniel Pigott around 1786. A culmination only happens about once a day, so it was combined with other observations to increase accuracy.

Satellites of Jupiter

Galileo discovered the four brightest moons of Jupiter, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto in 1610. Having determined their orbital periods, he proposed in 1612 that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits one could use their positions as a universal clock, which would make possible the determination of longitude. Galileo applied for Spain's lucrative prize for solutions to the longitude problem in 1616. He worked on this problem from time to time, but was unable to convince the Spanish court. He later applied to Holland for their prize, but by then he had been tried for heresy by theRoman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally , was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according ...

and sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life.

Galileo's method required a telescope, as the moons are not visible to the naked eye. For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship. This was later replaced with the idea of a pair of nested hemispheric shells separated by a bath of oil. This would provide a platform that would allow the observer to remain stationary as the ship rolled beneath him, in the manner of a

Galileo's method required a telescope, as the moons are not visible to the naked eye. For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship. This was later replaced with the idea of a pair of nested hemispheric shells separated by a bath of oil. This would provide a platform that would allow the observer to remain stationary as the ship rolled beneath him, in the manner of a gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis. A set of three gimbals, one mounted on the other with orthogonal pivot axes, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain independent of ...

led platform. To provide for the determination of time from the observed moons' positions, a jovilabe was offered; this was an analogue computer that calculated time from the positions and that got its name from its similarities to an astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

. The practical problems were severe and the method was never used at sea.

On land, this method proved useful and accurate. In 1668, Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian-French mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the County of Nice, part of the Savoyard sta ...

published detailed tables of Jupiter's moons. An early use was the measurement of the longitude of the site of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

's former observatory on the island of Hven

Ven (, older Swedish spelling ''Hven''), is a Swedish island in the Öresund strait laying between Scania, Sweden and Zealand, Denmark. A part of Landskrona Municipality, Skåne County, the island has an area of and 371 inhabitants as of 2020. ...

. Jean Picard on Hven and Cassini in Paris made observations during 1671 and 1672, and obtained a value of 42 minutes 10 seconds (time) east of Paris, corresponding to 10° 32' 30", about 12 minute of arc (1/5°) higher than the modern value.

Jupiter's moons provided time information for the French Académie des Sciences' project to survey France that produced a new map in 1744 which showed the coastline was significantly further east than on previous maps.

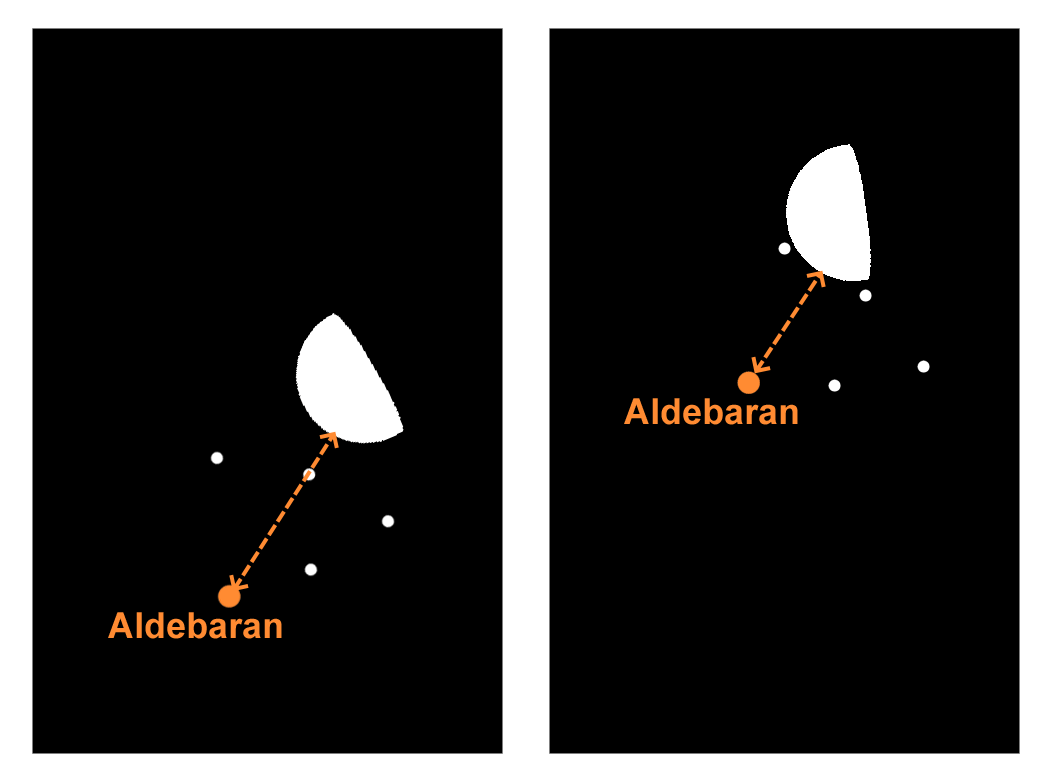

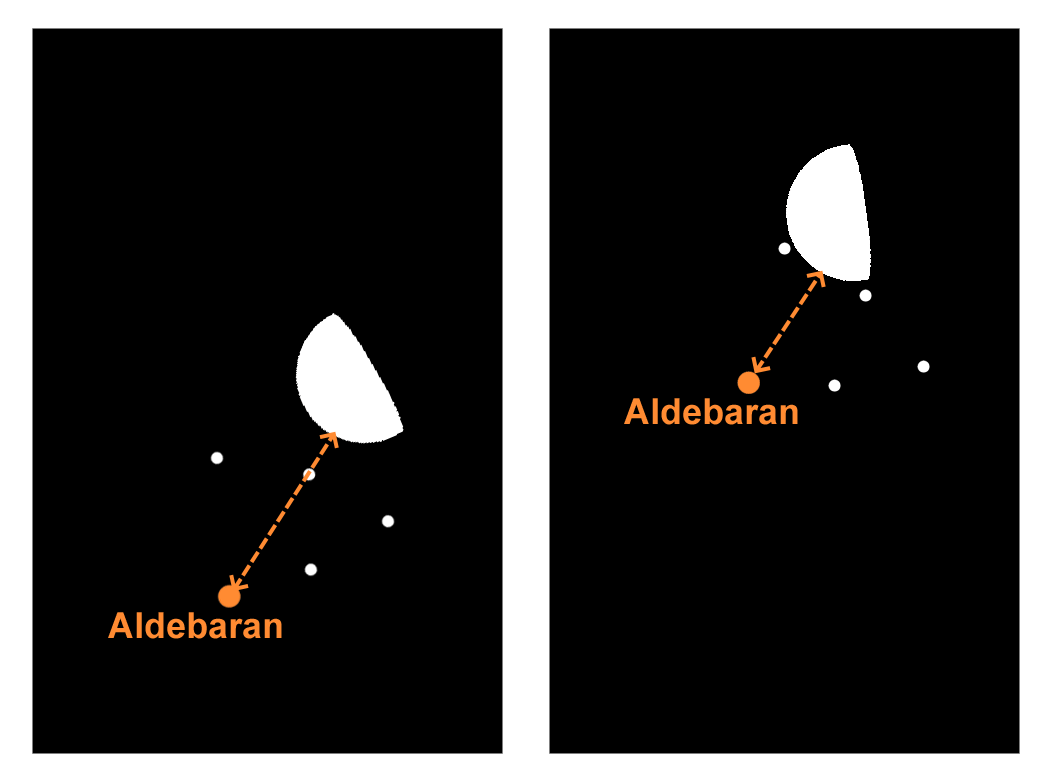

Appulses, occultations, transits, and eclipses

Several methods depend on the relative motions of the Moon and a star or planet. Anappulse

Appulse is the least angular distance, apparent distance between one astronomical object, celestial object and another, as seen from a third body during a given period. Appulse is seen in the apparent motion typical of two planets together in the ...

is the least apparent distance between the two objects, an occultation

An occultation is an event that occurs when one object is hidden from the observer by another object that passes between them. The term is often used in astronomy, but can also refer to any situation in which an object in the foreground blocks f ...

occurs when the star or planet passes behind the Moon – essentially a type of eclipse. The times of either of these events can be used as the measure of absolute time in the same way as with a lunar eclipse. Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

described the use of this method to determine the longitude of Balasore

Balasore, also known as Baleswar, is a city in the state of Odisha, about from the state capital Bhubaneswar and from Kolkata, in eastern India. It is the administrative headquarters of Balasore district and the largest city as well as heal ...

in India, using observations of the star Aldebaran

Aldebaran () is a star in the zodiac constellation of Taurus. It has the Bayer designation α Tauri, which is Latinized to Alpha Tauri and abbreviated Alpha Tau or α Tau. Aldebaran varies in brightness from an apparent vis ...

(the "Bull's Eye", being the brightest star in the constellation Taurus) in 1680, with an error of just over half a degree. He published a more detailed account of the method in 1717. A longitude determination using the occultation of a planet, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, was described by James Pound

James Pound (1669–1724) was an English clergyman and astronomer.

Life

He was the son of John Pound, of Bishops Cannings, Wiltshire, where he was born. He matriculated at St. Mary Hall, Oxford, on 16 March 1687; graduated B.A. from Hart Hall ...

in 1714. The 1769 transit of Venus provided an opportunity for determining accurate longitude of over 100 seaports around the world.

Transport of chronometers

Longitude calculations can be simplified using a clock is set to the local time of a starting point whose longitude is known, transporting it to a new location, and using it for astronomical observations. The longitude of the new location can be determined by comparing the difference oflocal mean time

Local mean time (LMT) is a form of solar time that corrects the variations of local apparent time, forming a uniform time scale at a specific longitude. This measurement of time was used for everyday use during the 19th century before time zones ...

and the time of the transported clock.

Pocket watches are known since the early 1500s, due to the pomander-shaped watch from 1505 made by Peter Henlein

Peter Henlein (also spelled Henle or Hele) (1485 - August 1542), a locksmith, clockmaker, and watchmaker of Nuremberg, Germany. Due to the Fire-gilded pomander-shaped Watch 1505, watch from 1505, he is often considered the inventor of the pocket ...

in Nuremberg, Germany, rather far away from the sea. The first to suggest traveling with a clock to determine longitude, in 1530, was Gemma Frisius

Gemma Frisius (; born Jemme Reinerszoon; December 9, 1508 – May 25, 1555) was a Dutch physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker. He created important globes, improved the mathematical instruments of his day ...

, a physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker from the Netherlands. The clock would be set to the local time of a starting point whose longitude was known, and the longitude of any other place could be determined by comparing its local time with the clock time: there is a four-minute difference between locally observed noon and clock noon for each degree of longitude east or west of the initial meridian. While the method is mathematically sound, and was partly stimulated by recent improvements in the accuracy of mechanical clocks, it still required far more accurate timekeeping than was available in Frisius's day. The term chronometer was not used until the following century; it would be over two centuries before this became the standard method for determining longitude at sea, John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

receiving an award in 1773 for solving the longitude at sea problem via his chronometer inventions.

Magnetic declination

This method is based on the observation that a compass needle does not in general point exactly north. The angle between true north and the direction of the compass needle (magnetic north) is called themagnetic declination

Magnetic declination (also called magnetic variation) is the angle between magnetic north and true north at a particular location on the Earth's surface. The angle can change over time due to polar wandering.

Magnetic north is the direction th ...

or variation, and its value varies from place to place. Several writers proposed that the size of magnetic declination could be used to determine longitude. Mercator suggested that the magnetic north pole was an island in the longitude of the Azores, where magnetic declination was, at that time, close to zero. These ideas were supported by Michiel Coignet in his ''Nautical Instruction''.

Halley made extensive studies of magnetic variation during his voyages on the pink

Pink is a pale tint of red, the color of the Dianthus plumarius, pink flower. It was first used as a color name in the late 17th century. According to surveys in Europe and the United States, pink is the color most often associated with charm, p ...

''Paramour''. He published the first chart showing '' isogonic lines'' – lines of equal magnetic declination – in 1701. One of the purposes of the chart was to aid in determining longitude, but the method was eventually to fail as changes in magnetic declination over time proved too large and too unreliable to provide a basis for navigation.

Land and sea

Measurements of longitude on land and sea complemented one another. As Edmond Halley pointed out in 1717, "But since it would be needless to enquire exactly what longitude a ship is in, when that of the port to which she is bound is still unknown it were to be wisht that the princes of the earth would cause such observations to be made, in the ports and on the principal head-lands of their dominions, each for his own, as might once for all settle truly the limits of the land and sea." But determinations of longitude on land and sea did not develop in parallel.

On land the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid-18th century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2–3°. By the 1720s errors were consistently less than 1°.

At sea during the same period, the situation was very different. Two problems proved intractable. The first was the need for immediate results. On land, an astronomer at, say, Cambridge Massachusetts could wait for the next lunar eclipse that would be visible both at Cambridge and in London; set a pendulum clock to local time in the few days before the eclipse; time the events of the eclipse; send the details across the Atlantic and wait weeks or months to compare the results with a London colleague who had made similar observations; calculate the longitude of Cambridge; then send the results for publication, which might be a year or two after the eclipse. And if either Cambridge or London had no visibility because of cloud, wait for the next eclipse. The marine navigator needed the results quickly. The second problem was the marine environment. Making accurate observations in an ocean swell is much harder than on land, and pendulum clocks do not work well in these conditions. Thus longitude at sea could only be estimated from

Measurements of longitude on land and sea complemented one another. As Edmond Halley pointed out in 1717, "But since it would be needless to enquire exactly what longitude a ship is in, when that of the port to which she is bound is still unknown it were to be wisht that the princes of the earth would cause such observations to be made, in the ports and on the principal head-lands of their dominions, each for his own, as might once for all settle truly the limits of the land and sea." But determinations of longitude on land and sea did not develop in parallel.

On land the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid-18th century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2–3°. By the 1720s errors were consistently less than 1°.

At sea during the same period, the situation was very different. Two problems proved intractable. The first was the need for immediate results. On land, an astronomer at, say, Cambridge Massachusetts could wait for the next lunar eclipse that would be visible both at Cambridge and in London; set a pendulum clock to local time in the few days before the eclipse; time the events of the eclipse; send the details across the Atlantic and wait weeks or months to compare the results with a London colleague who had made similar observations; calculate the longitude of Cambridge; then send the results for publication, which might be a year or two after the eclipse. And if either Cambridge or London had no visibility because of cloud, wait for the next eclipse. The marine navigator needed the results quickly. The second problem was the marine environment. Making accurate observations in an ocean swell is much harder than on land, and pendulum clocks do not work well in these conditions. Thus longitude at sea could only be estimated from dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

(DR) – by using estimations of speed and course from a known starting position – at a time when longitude determination on land was becoming increasingly accurate.

To compensate for longitude uncertainty, navigators have sometimes relied on their accurate knowledge of latitude. They would sail to the latitude of their destination, then sail toward it along a line of constant latitude, known as ''running down a westing'' (if westbound, ''easting'' otherwise). However, the latitude line was usually slower than the most direct or most favorable route, extending the voyage by days or weeks and increasing the risk of short rations, scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, and starvation.

A famous longitude-error disaster occurred in April 1741. George Anson, commanding , was rounding Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

east to west. Believing himself past the Cape, he turned to the north but soon found himself headed straight towards land. A particularly strong easterly current had put him well to the east of his dead-reckoning position, and he had to resume his westerly course for several days. When finally past the Horn, he headed north for the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands () are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean, reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic islands: Robinson Crusoe Island, R ...

to take on supplies for his crew, many of whom were sick with scurvy. On reaching the latitude of Juan Fernández, he did not know whether the islands were to the east or west, and spent 10 days sailing first eastwards and then westwards before finally reaching the islands. During this time over half of the ship's company died of scurvy.

Government initiatives

In response to the problems of navigation, a number of European maritime powers offered prizes for a method to determine longitude at sea.Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

was the first, offering a reward for a solution in 1567; his son, Philip III, increased the reward in 1598 to 6000 gold ducat

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

s plus a permanent pension of 2,000 gold ducats a year. Holland offered 30,000 florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin (in Italian ''Fiorino d'oro'') struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time.

It had 54 grains () of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a pu ...

s in the early 17th century. Neither of these prizes produced a solution, though Galileo applied for both.

The second half of the 17th century saw the foundation of official observatories in Paris and London. The Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

was founded in 1667 under the auspices of the French Académie des Sciences. The Observatory building south of Paris was completed in 1672. Early astronomers included Jean Picard, Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

, and Dominique Cassini. It was not intended for any specific project, but soon became involved in the survey of France that led (after many delays due to wars and unsympathetic ministries) to the Academy's first map of France in 1744. The survey used a combination of triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle m ...

and astronomical observations, with the satellites of Jupiter used to determine longitude. By 1684, sufficient data had been obtained to show that previous maps of France had a major longitude error, showing the Atlantic coast too far to the west. In fact France was found to be substantially smaller than previously thought. (Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

commented that they had taken more territory from France than he had gained in all his wars.)

The Royal Observatory in Greenwich east of London, founded in 1675, a few years after the Paris Observatory, was established explicitly to address the longitude problem. John Flamsteed

John Flamsteed (19 August 1646 – 31 December 1719) was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, ''Catalogus Britannicus'', and a star atlas called '' Atlas ...

, the first Astronomer Royal, was instructed to "apply himself with the utmost care and diligence to the rectifying the tables of the motions of the heavens and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so-much-desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation". The initial work was in cataloguing stars and their position, and Flamsteed created a catalogue of 3,310 stars, which formed the basis for future work.

While Flamsteed's catalogue was important, it did not in itself provide a solution. In 1714, the British Parliament passed " An Act for providing a public Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea" ( 13 Ann. c. 14), and set up a board to administer the award. The payout depended on the accuracy of the method: from for an accuracy within one degree of longitude ( at the equator) to for accuracy within one half degree.

This prize in due course produced two workable solutions. The first was lunar distances, which required careful observation, accurate tables, and rather lengthy calculations. Tobias Mayer had produced tables based on his own observations of the moon, and submitted these to the Board in 1755. These observations were found to give the required accuracy, although the lengthy calculations required (up to four hours) were a barrier to routine use. Mayer's widow in due course received an award from the Board. Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne (; 6 October 1732 – 9 February 1811) was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created '' The Nautical Al ...

, the newly appointed Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

who was on the Board of Longitude, started with Mayer's tables and after his own experiments at sea trying out the lunar distance method, proposed annual publication of pre-calculated lunar distance predictions in an official nautical almanac for the purpose of finding longitude at sea. Being very enthusiastic for the lunar distance method, Maskelyne and his team of computers

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations ('' computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as ''programs'', ...

worked feverishly through the year 1766, preparing tables for the new Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Published first with data for the year 1767, it included daily tables of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets and other astronomical data, as well as tables of lunar distances giving the distance of the Moon from the Sun and nine stars suitable for lunar observations (ten stars for the first few years).

This publication later became the standard almanac for mariners worldwide. Since it was based on the Royal Observatory, it helped lead to the international adoption a century later of the Greenwich Meridian

The Greenwich meridian is a prime meridian, a geographical reference line that passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, England. From 1884 to 1974, the Greenwich meridian was the international standard prime meridian, ...

as an international standard.

The second method was the use of a chronometer. Many, including

The second method was the use of a chronometer. Many, including Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, were pessimistic that a clock of the required accuracy could ever be developed. The Earth turns by one degree of longitude in four minutes, so the maximum acceptable timekeeping error is a few seconds per day. At that time, there were no clocks that could come close to such accuracy under the conditions of a moving ship. John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

, a Yorkshire carpenter and clock-maker, spent over three decades in proving it could be done.

Harrison built five chronometers, two of which were tested at sea. His first, ''H-1,'' was sent on a preliminary test by the Admiralty, a voyage to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

and back. It lost considerable time on the outward voyage but performed excellently on the return leg, which was not part of the official trial. The perfectionist in Harrison prevented him from sending it on the Board of Longitude's official test voyage to the West Indies (and in any case it was regarded as too large and impractical for service use). He instead embarked on the construction of ''H-2'', immediately followed by ''H-3.'' During construction of ''H-3'', Harrison realised that the loss of time of the ''H-1'' on the Lisbon outward voyage was due to the mechanism losing time whenever the ship came about to tack down the English Channel. Inspired by this realisation, Harrison produced ''H-4'' with a completely different mechanism. The ''H-4'' sea trial in 1762 satisfied all the requirements for the Longitude Prize. However, the board withheld the prize, and Harrison was forced to fight for his reward, finally receiving payment in 1773 after the intervention of Parliament.

The French were also very interested in the problem of longitude, and the French Academy examined proposals and also offered prize money, particularly after 1748. Initially the assessors were dominated by the astronomer Pierre Bouguer

Pierre Bouguer () (16 February 1698, Le Croisic – 15 August 1758, Paris) was a French mathematician, geophysicist, geodesist, and astronomer. He is also known as "the father of naval architecture".

Career

Bouguer's father, Jean Bouguer, ...

who was opposed to the idea of chronometers, but after his death in 1758 both astronomical and mechanical approaches were considered. Two clock-makers dominated, Ferdinand Berthoud and Pierre Le Roy. Four sea trials took place between 1767 and 1772, evaluating lunar distances as well as a variety of time-keepers. Results for both approaches steadily improved as the trials proceeded, and both methods were deemed suitable for use in navigation.

Lunar distances versus chronometers

Henry Sully (1680-1729) presented a marine chronometer in 1716 Although both chronometers and lunar distances had been shown to be practicable methods for determining longitude, it was some while before either became widely used. In the early years, chronometers were very expensive, and the calculations required for lunar distances were still complex and time-consuming, in spite of Maskelyne's work to simplify them. Both methods were initially used mainly in specialist scientific and surveying voyages. On the evidence of ships' logbooks and nautical manuals, lunar distances started to be used by ordinary navigators in the 1780s, and became common after 1790. In 1714Humphry Ditton

Humphry Ditton (29 May 1675 – 15 October 1715) was an English mathematician. He was the author of several influential works.

Life

Ditton was born on 29 May 1675 in Salisbury, the only son of Humphry Ditton, gentleman and ardent nonconformist ...

and William Whiston

William Whiston (9 December 166722 August 1752) was an English theologian, historian, natural philosopher, and mathematician, a leading figure in the popularisation of the ideas of Isaac Newton. He is now probably best known for helping to inst ...

criticized both astronomical methods and the use of chronometers. They wrote:

While chronometers could deal with the conditions of a ship at sea, they could be vulnerable to the harsher outdoor conditions of land-based exploration and surveying, for example in the American North-West, and lunar distances were the main method used by surveyors such as David Thompson. Between January and May 1793 he took 34 observations at Cumberland House, Saskatchewan

Cumberland House () is a community in Division No. 18, Saskatchewan, Census Division No. 18 in northeast Saskatchewan, Canada on the Saskatchewan River. It is the oldest community in Saskatchewan and has a population of about 2,000 people. Cum ...

, obtaining a mean value of 102° 12' W, about 2' (2.2 km) east of the modern value. Sebert gives 102° 16' as the longitude of Cumberland House, but Old Cumberland House, still in use at that time, was 2km to the east, see: Each of the 34 observations would have required about 3 hours of calculation. These lunar distance calculations became substantially simpler in 1805, with the publication of tables using the Haversine formula

The haversine formula determines the great-circle distance between two points on a sphere given their longitudes and latitudes. Important in navigation, it is a special case of a more general formula in spherical trigonometry, the law of haversines ...

by Josef de Mendoza y Ríos.

The advantage of using chronometers was that though astronomical observations were still needed to establish local time, the observations were simpler and less demanding of accuracy. Once local time had been established, and any necessary corrections made to the chronometer time, the calculation to obtain longitude was straightforward. A contemporary guide to the method was published by William Wales in 1794. The disadvantage of cost gradually became less as chronometers began to be made in quantity. The chronometers used were not those of Harrison. Other makers such as Thomas Earnshaw, who developed the spring detent escapement, simplified chronometer design and production. From 1800 to 1850, as chronometers became more affordable and reliable, they increasingly displaced the lunar distance method.

Chronometers needed to be checked and reset at intervals. On short voyages between places of known longitude this was not a problem. For longer journeys, particularly of survey and exploration, astronomical methods continued to be important. An example of the way chronometers and lunars complemented one another in surveying work is Matthew Flinders

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer, navigator and cartographer who led the first littoral zone, inshore circumnavigate, circumnavigation of mainland Australia, then ...

' circumnavigation of Australia in 1801–3. Surveying the south coast, Flinders started at King George Sound

King George Sound (Mineng ) is a sound (geography), sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came in ...

, a known location from George Vancouver

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain George Vancouver (; 22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for leading the Vancouver Expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern West Coast of the Uni ...

's earlier survey. He proceeded along the south coast, using chronometers to determine longitude of the features along the way. Arriving at the bay he named Port Lincoln

Port Lincoln is a city on the Lower Eyre Peninsula in the Australian states and territories of Australia, state of South Australia. Known as Galinyala by the traditional owners, the Barngarla people, it is situated on the shore of Boston Bay, ...

, he set up a shore observatory, and determined the longitude from thirty sets of lunar distances. He then determined the chronometer error, and recalculated all the longitudes of the intervening locations.

Ships often carried more than one chronometer. Two would give dual modular redundancy

In reliability engineering, dual modular redundancy (DMR) is when components of a system are duplicated, providing redundancy in case one should fail. It is particularly applied to systems where the duplicated components work in parallel, particu ...

, allowing a backup if one should cease to work, but not allowing any error correction

In information theory and coding theory with applications in computer science and telecommunications, error detection and correction (EDAC) or error control are techniques that enable reliable delivery of digital data over unreliable communi ...

if the two displayed a different time, since it would be impossible to know which one was wrong: the error detection

In information theory and coding theory with applications in computer science and telecommunications, error detection and correction (EDAC) or error control are techniques that enable reliable delivery of digital data over unreliable communi ...

obtained would be the same as having only one chronometer and checking it periodically: every day at noon against dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

. Three chronometers provided triple modular redundancy

In computing, triple modular redundancy, sometimes called triple-mode redundancy, (TMR) is a fault-tolerant form of N-modular redundancy, in which three systems perform a process and that result is processed by a majority-voting system to produc ...

, allowing error correction

In information theory and coding theory with applications in computer science and telecommunications, error detection and correction (EDAC) or error control are techniques that enable reliable delivery of digital data over unreliable communi ...

if one of the three was wrong, so the pilot would take the average of the two with closer readings (average precision vote). This inspired the adage: "Never go to sea with two chronometers; take one or three." Some vessels carried more than three chronometers – for example, HMS ''Beagle'' carried 22 chronometers.

By 1850, the vast majority of ocean-going navigators worldwide had abandoned the method of lunar distances. Nonetheless, expert navigators continued to learn lunars as late as 1905, though for most this was only a textbook exercise required for certain licenses. Littlehales noted in 1909: "The lunar-distance tables were omitted from the ''Connaissance des Temps'' for the year 1905, after having retained their place in the French official ephemeris for 131 years; and from the British ''Nautical Almanac'' for 1907, after having been presented annually since the year 1767, when Maskelyne's tables were published."

Land surveying and telegraphy

Surveying on land continued to use a mixture of triangulation and astronomical methods, to which was added the use of chronometers once they became readily available. An early use of chronometers in land surveying was reported by Simeon Borden in his survey of Massachusetts in 1846. Having checkedNathaniel Bowditch

Nathaniel Bowditch (March 26, 1773 – March 16, 1838) was an early American mathematician remembered for his work on ocean navigation. He is often credited as the founder of modern maritime navigation; his book '' The New American Practical Navi ...

's value for the longitude of the State House in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

he determined the longitude of the First Congregational Church at Pittsfield, transporting 38 chronometers on 13 excursions between the two locations. Chronometers were also transported much longer distances. For example, the United States Coast Survey organised expeditions in 1849 and 1855 in which a total of over 200 chronometers were shipped between Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, not for navigation, but to obtain a more accurate determination of the longitude of the Observatory at Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

, and thus to anchor the US Survey to the Greenwich meridian.

The first working telegraphs were established in Britain by Wheatstone and Cooke in 1839, and in the US by Morse in 1844. The idea of using the telegraph to transmit a time signal for longitude determination was suggested by François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

to Morse in 1837, and the first test of this idea was made by Capt. Wilkes of the U.S. Navy in 1844, over Morse's line between Washington and Baltimore. Two chronometers were synchronized, and taken to the two telegraph offices to check that time was accurately transmitted.

The method was soon in practical use for longitude determination, in particular by the U.S. Coast Survey, and over longer and longer distances as the telegraph network spread across North America. Many technical challenges were dealt with. Initially operators sent signals manually and listened for clicks on the line and compared them with clock ticks, estimating fractions of a second. Circuit breaking clocks and pen recorders were introduced in 1849 to automate these process, leading to great improvements in both accuracy and productivity. With the establishment of an observatory in

The method was soon in practical use for longitude determination, in particular by the U.S. Coast Survey, and over longer and longer distances as the telegraph network spread across North America. Many technical challenges were dealt with. Initially operators sent signals manually and listened for clicks on the line and compared them with clock ticks, estimating fractions of a second. Circuit breaking clocks and pen recorders were introduced in 1849 to automate these process, leading to great improvements in both accuracy and productivity. With the establishment of an observatory in Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

in 1850 under the direction of Edward David Ashe, a network of telegraphic longitude determinations was carried out for eastern Canada, and linked to that of Harvard and Chicago.

A big expansion to the "telegraphic net of longitude" was due to the successful completion of the transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is a largely obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and dat ...

between S.W. Ireland and Nova Scotia in 1866. A cable from Brest in France to Duxbury Massachusetts was completed in 1870, and gave the opportunity to check results by a different route. In the interval, the land-based parts of the network had improved, including the elimination of repeaters. Comparisons of the difference between Greenwich and Cambridge Massachusetts showed differences between measurement of 0.01 second of time, with a probable error of ±0.04 seconds, equivalent to 45 feet. Summing up the net in 1897, Charles Schott presented a table of the major locations throughout the United States whose locations had been determined by telegraphy, with the dates and pairings, and the probable error. The net was expanded into the American North-West with telegraphic connection to Alaska and western Canada. Telegraphic links between Dawson City