Littleton Ernest Groom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

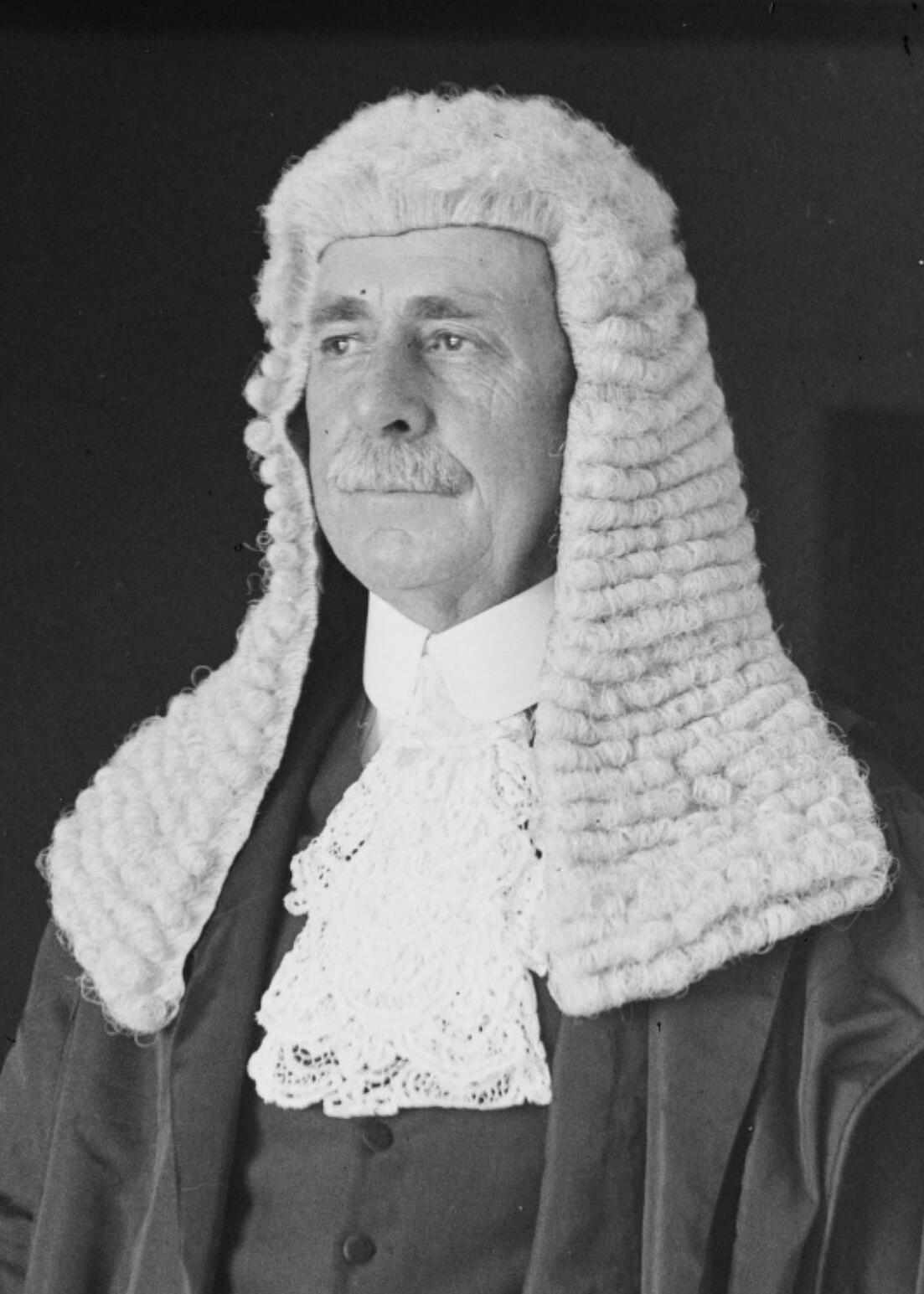

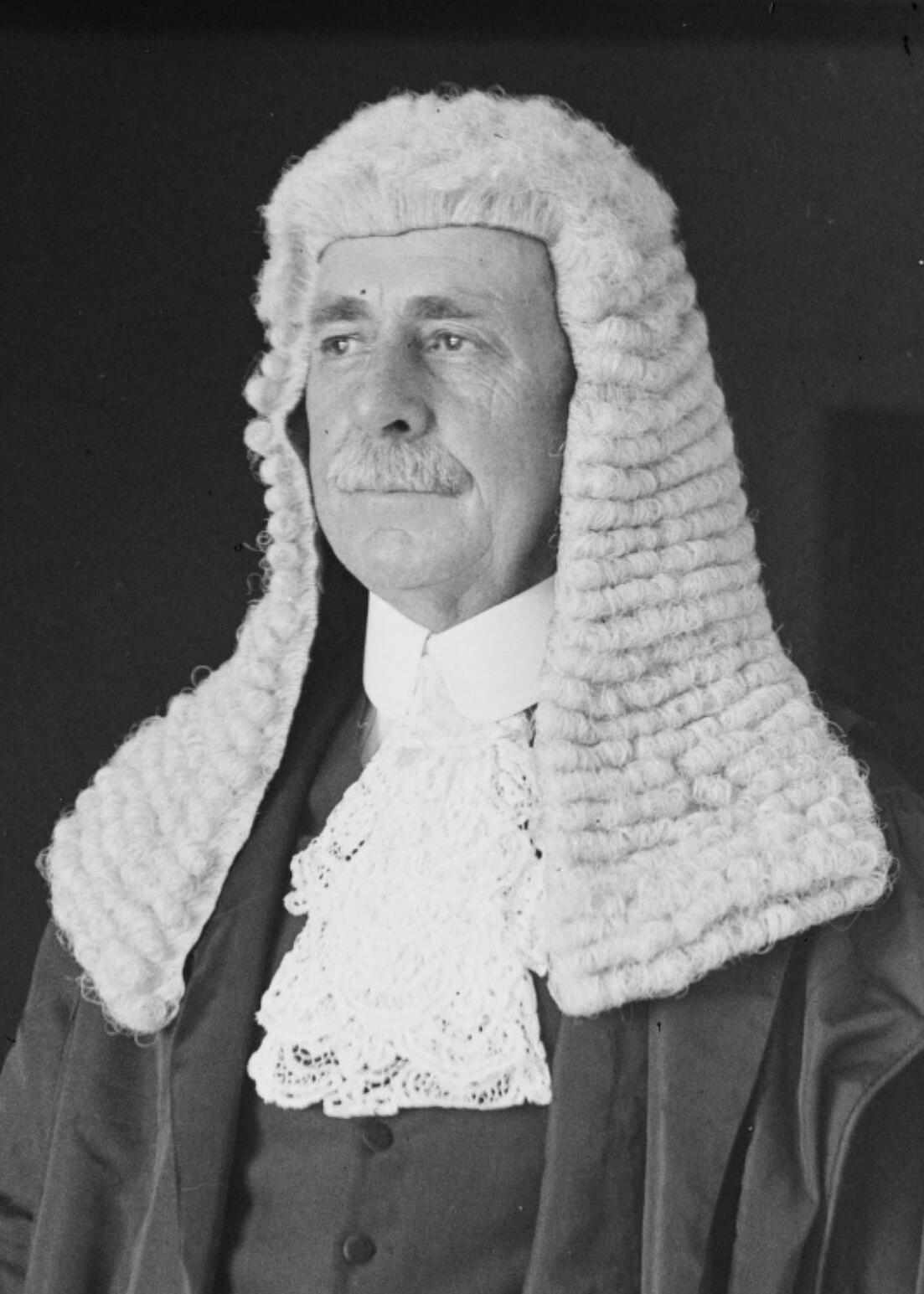

Sir Littleton Ernest Groom

Groom's father was elected to the

Groom's father was elected to the

In July 1905, Deakin replaced Reid as prime minister and appointed Groom as

In July 1905, Deakin replaced Reid as prime minister and appointed Groom as

In return for his resignation, Groom was elected as Speaker of the House of Representatives and presided from January 1926 to 1929, when he helped oversee the move of federal Parliament from

In return for his resignation, Groom was elected as Speaker of the House of Representatives and presided from January 1926 to 1929, when he helped oversee the move of federal Parliament from

Groom was joint author with

Groom was joint author with

KCMG KCMG may refer to

* KC Motorgroup, based in Hong Kong, China

* Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, British honour

* KCMG-LP, radio station in New Mexico, USA

* KCMG, callsign 1997-2001 of Los Angeles radio station KKLQ (FM) ...

KC (22 April 18676 November 1936) was an Australian politician. He held ministerial office under four prime ministers between 1905 and 1925, and subsequently served as Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1926 to 1929.

Groom was the son of William Henry Groom

William Henry Groom (9 March 1833 – 8 August 1901) was an Australian publican, newspaper proprietor, and politician who served as a member of the Parliament of Queensland from 1862 to 1901 and of the Parliament of Australia in 1901.

Early li ...

, who had arrived in Australia as a convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convict ...

but became a prominent public figure in the Colony of Queensland

The Colony of Queensland was a colony of the British Empire from 1859 to 1901, when it became a State in the federal Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. At its greatest extent, the colony included the present-day State of Queensland, t ...

. He was a lawyer by profession, entering federal parliament at the 1901 Darling Downs by-election following his father's death. Groom was first appointed to cabinet by Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

in 1905. Over the following two decades he served as Minister for Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

(1905–1906), Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

(1906–1908), External Affairs

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through mu ...

(1909–1910), Trade and Customs (1913–1914), Vice-President of the Executive Council

The Vice-President of the Executive Council is the minister in the Government of Australia who acts as the presiding officer of meetings of the Federal Executive Council when the Governor-General is absent. The Vice-President of the Executive ...

(1917–1918), Works and Railways (1918–1921), and Attorney-General (1921–1925).

A political liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and anti-socialist

Criticism of socialism (also known as anti-socialism) is any critique of socialist models of economic organization and their feasibility as well as the political and social implications of adopting such a system. Some critiques are not directed ...

, Groom was initially affiliated with Deakin's Protectionists

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

, who were later superseded by the Liberals (1909) and Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

(1917). He came into conflict with Prime Minister Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, as leader of the Nationalist Party.

Born ...

during the 1920s, and as speaker in 1929 refused to use his casting vote

A casting vote is a vote that someone may exercise to resolve a tied vote in a deliberative body. A casting vote is typically by the presiding officer of a council, legislative body, committee, etc., and may only be exercised to break a deadlock ...

to save the government on a confidence motion

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

. He was expelled from the Nationalists and lost his seat at the resulting election, but was re-elected in 1931 as an independent. He joined the United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

(UAP) in 1933 and continued as a backbencher

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of the " ...

until his death in 1936.

Early life

Groom was born on 22 April 1867 inToowoomba, Queensland

Toowoomba ( , nicknamed 'The Garden City' and 'T-Bar') is a city in the Toowoomba Region of the Darling Downs, Queensland, Australia. It is west of Queensland's capital city Brisbane by road. The urban population of Toowoomba as of the 2021 C ...

. He was the third son of Grace (née Littleton) and William Henry Groom

William Henry Groom (9 March 1833 – 8 August 1901) was an Australian publican, newspaper proprietor, and politician who served as a member of the Parliament of Queensland from 1862 to 1901 and of the Parliament of Australia in 1901.

Early li ...

. His English-born father had been transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln. It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she wou ...

to Australia as a convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convict ...

in 1846, but became a successful businessman and public official, serving as mayor of Toowoomba and in the Queensland Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembly ...

and Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of the ...

.

Groom attended Toowoomba North State School and Toowoomba Grammar School

, motto_translation = Faithful in All Things

, city = Toowoomba

, state = Queensland

, country = Australia

, coordinates =

, type = Independent, day & boarding

, denomination = Non-denominational

, established = ...

, where he was school dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, ''dux' ...

and captain of the cricket and football teams. He went on to attend Ormond College

Ormond College is the largest of the residential colleges of the University of Melbourne located in the city of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It is home to around 350 undergraduates, 90 graduates and 35 professorial and academic residents.

Hi ...

at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, winning scholarships and graduating Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

in 1889 and Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

in 1891. Groom subsequently returned to Queensland and practised as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

. He was "a leading figure in the Queensland University Extension Movement" and was also involved with the Brisbane Literary Circle and the Brisbane School of Arts

Brisbane School of Arts is a heritage-listed school of arts at 166 Ann Street, Brisbane City, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1865 to 1985. It is also known as former Servants Home. It was added to the Queensland ...

. In 1900 he was appointed a deputy judge on the District Court of Queensland

The District Court of Queensland (QDC) is the second tier in the court hierarchy of Queensland, Australia. The Court deals with serious criminal offences such as rape, armed robbery and fraud. Juries are used to decide if defendants are guilty ...

.

In July 1894, Groom married Jessie Bell, with whom he had two daughters.

Politics

Early years

Groom's father was elected to the

Groom's father was elected to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

at the inaugural 1901 federal election, but in August 1901 became the first federal MP to die in office. His son quickly agreed to stand at the resulting by-election in the seat of Darling Downs

The Darling Downs is a farming region on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range in southern Queensland, Australia. The Downs are to the west of South East Queensland and are one of the major regions of Queensland. The name was generall ...

. He was publicly endorsed by Prime Minister Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

, but the government provided little assistance and none of its members campaigned on his behalf. Groom was opposed by Joshua Thomas Bell

Joshua Thomas Bell (13 March 1863 – 10 March 1911) was an Australian barrister and politician.

Bell was the son of Sir Joshua Peter Bell, and his wife Margaret Miller, née Dorsey and was born in Ipswich, Queensland. Bell was educated at ...

, a conservative independent whose father had similarly been a colonial MP. His policy speech in Toowoomba called for federal co-ordination of agriculture, old-age pensions, and compulsory arbitration

Compulsion may refer to:

* Compulsive behavior, a psychological condition in which a person does a behavior compulsively, having an overwhelming feeling that they must do so.

* Obsessive–compulsive disorder, a mental disorder characterized by i ...

, although "his great emphasis was on the necessity of the White Australia policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

". His margin of victory was smaller than his father's had been, though still comfortable, and in celebration his supporters pulled him and his wife through the streets of Toowoomba in a wagonette

A wagonette (''little wagon'') is a small horse-drawn vehicle with springs, which has two benches along the right and left side of the platform, people facing each other. The driver sits on a separate, front-facing bench. A wagonette may be open ...

. He proclaimed that "liberalism has triumphed over conservatism, and ..you have decided that Australia shall be white".

Groom joined the radical faction of Barton's Liberal Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

and his views were closely aligned with those of Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

. He devoted his maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

to the topic of immigration, supporting a total ban on non-white immigration into Australia and declaring his opposition to miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

. In contrast to other rural MPs, Groom was a centralist

Centralisation or centralization (see spelling differences) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, framing strategy and policies become concentrated within a particu ...

who felt the federal government should use its full constitutional powers; he "frequently stressed federal parliamentarians should deal with things from a continental rather than a state viewpoint." He lobbied for the immediate creation of a High Court, arguing that it was essential to preserve the rights of smaller states.

In 1904, Groom supported Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms the f ...

(ALP) leader Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lead ...

's amendment to the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill which would extend its reach to state railway employees. However, he voted with the Deakin Government against Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician who served three terms as prime minister of Australia – from 1908 to 1909, from 1910 to 1913, and from 1914 to 1915. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party ...

's amendment, a vote which became a confidence motion

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

and resulted in Deakin's resignation. Groom was subsequently one of seven Protectionists who gave regular support to the short-lived Watson Government. After another change of government he was part of a group of Protectionists who sat on the opposition benches under Watson as leader of the opposition. In November 1904 he introduced the first successful private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in whi ...

, passed as the ''Life Assurance Companies Act 1905'', to regulate life insurance policies taken out on children under the age of 10.

Government minister

In July 1905, Deakin replaced Reid as prime minister and appointed Groom as

In July 1905, Deakin replaced Reid as prime minister and appointed Groom as Minister for Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

in the new ministry. His department had a number of responsibilities, including oversight of the Commonwealth Public Service

The Australian Public Service (APS) is the federal civil service of the Commonwealth of Australia responsible for the public administration, public policy, and public services of the departments and executive and statutory agencies of the G ...

, public works, federal elections, and the siting of the national capital. Although relatively young and inexperienced, he was one of the few Queenslanders considered suitable by Deakin and was also ideologically close to the ALP upon whose support the government depended.

One of Groom's first acts was to introduce the ''Census and Statistics Act 1905'', establishing the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is the independent statutory agency of the Australian Government responsible for statistical collection and analysis and for giving evidence-based advice to federal, state and territory governments ...

as a complement to existing state bureaus of statistics. He correctly anticipated that the states would eventually hand over their offices to federal control, but his attempt to appoint Timothy Coghlan as the inaugural Commonwealth Statistician brought him into conflict with Joseph Carruthers

Sir Joseph Hector McNeil Carruthers (21 December 185710 December 1932) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of New South Wales from 1904 to 1907.

Carruthers is perhaps best remembered for founding the Liberal and Reform Associa ...

, the premier of New South Wales. Groom also introduced the ''Meteorology Act 1906'' to create the Bureau of Meteorology

The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM or BoM) is an executive agency of the Australian Government responsible for providing weather services to Australia and surrounding areas. It was established in 1906 under the Meteorology Act, and brought together ...

. Unlike the bureau of statistics, he had secured agreement from the states to cede control before introducing the legislation. His general philosophy was that "wherever the Commonwealth could satisfactorily perform a duty handled by the states it should be allowed to do so".

Groom's ''Lands Acquisition Act 1906'' allowed for compulsory acquisition

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

by the federal government and the granting of mining leases on federal land. In the same year he achieved agreement with the states over the valuation of properties transferred to the Commonwealth under section 69 of the constitution. Groom further clashed with Joseph Carruthers over the location of the capital, which the Watson Government's ''Seat of Government Act 1904

The Seat of Government Act 1904 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which provided that the "seat of government of the Commonwealth" (i.e., the national capital) should be within of Dalgety, New South Wales.

The site turned out to be un ...

'' had fixed as Dalgety, New South Wales

Dalgety is a small town in New South Wales, Australia, on the banks of the Snowy River between Melbourne and Sydney.

The town is located at what was once an important river crossing along the Travelling Stock route from Gippsland to the Snowy ...

. Rather than acquiescing, Carruthers instead offered three alternative sites closer to the state capital of Sydney. In December 1905, Groom introduced another bill which would have defined the limits of the capital district

A capital district, capital region or capital territory is normally a specially designated administrative division where a country's seat of government is located. As such, in a federal model of government, no state or territory has any politica ...

. During the second reading

A reading of a bill is a stage of debate on the bill held by a general body of a legislature.

In the Westminster system, developed in the United Kingdom, there are generally three readings of a bill as it passes through the stages of becoming, ...

speech he accused the New South Wales state government of parochialism and obstructionism, which was poorly received. The bill was allowed to lapse and the issue was not resolved until the ''Seat of Government Act 1908

The Seat of Government Act 1908 was enacted by the Australian Government on 14 December 1908. The act selected the Yass-Queanbeyan region as the site for Canberra, the new capital city of Australia.

The act repealed the earlier ''Seat of Govern ...

'' established Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

as the new capital.

In October 1906, Groom became Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

until the defeat of the Deakin government in November 1908. Groom passed legislation to defend the Harvester Judgment

''Ex parte H.V. McKay'',''Ex parte H.V. McKay'(1907) 2 CAR 1 commonly referred to as the ''Harvester case'', is a landmark Australian labour law decision of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. The case arose under the ''Exci ...

and successfully introduced legislation providing Commonwealth invalid and old age pensions.

With the formation of the Fusion government in June 1909, Groom became Minister for External Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

until the Fusion's defeat in the 1910 election.

He had carried legislation establishing the High Commission of Australia in London

The High Commission of Australia in London is the diplomatic mission of Australia in the United Kingdom. It is located in Australia House, a Grade II listed building. It was Australia's first diplomatic mission and is the longest continuously ...

. After the 1910 election, he became a strong opponent of Labor and attacked its establishment of a government-owned Commonwealth Bank

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), or CommBank, is an Australian multinational bank with businesses across New Zealand, Asia, the United States and the United Kingdom. It provides a variety of financial services including retail, busines ...

and its attempt to gain the power to control monopolies. He was Trade and Customs in the Cook Ministry from June 1913 to September 1914.

Groom was Vice-President of the Executive Council

The Vice-President of the Executive Council is the minister in the Government of Australia who acts as the presiding officer of meetings of the Federal Executive Council when the Governor-General is absent. The Vice-President of the Executive ...

in Hughes's Nationalist government from November 1917 to March 1918 and Works and Railways from March 1918 to December 1921. He encouraged railway development and was involved in accelerating the construction of Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

.

In December 1921 he became Attorney-General again. He was Minister for Trade and Customs and Minister for Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Count ...

in May and June 1924, following Austin Chapman

Sir Austin Chapman (10 July 186412 January 1926) was an Australian politician who served in the House of Representatives from 1901 until his death in 1926. He held ministerial office in the governments of Alfred Deakin and Stanley Bruce, servi ...

's resignation on grounds of ill health. Groom led the 1924 Australian delegation to the Fifth Assembly of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

and chaired a committee, which formulated a protocol to establish a system of international arbitration and later voted to support its protocol despite an instruction to abstain. Groom involved himself in attempts to deport "foreign" agitators, but due to his poor handling of these and other matters, he was obliged to resign in December 1925.

Speaker of the House

In return for his resignation, Groom was elected as Speaker of the House of Representatives and presided from January 1926 to 1929, when he helped oversee the move of federal Parliament from

In return for his resignation, Groom was elected as Speaker of the House of Representatives and presided from January 1926 to 1929, when he helped oversee the move of federal Parliament from Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

to the newly constructed capital Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

.

His refusal to use his tiebreaking vote as speaker on a bill that would remove the Commonwealth from most of its involvement in conciliation and arbitration led to the collapse of the Bruce

The English language name Bruce arrived in Scotland with the Normans, from the place name Brix, Manche in Normandy, France, meaning "the willowlands". Initially promulgated via the descendants of king Robert the Bruce (1274−1329), it has been a ...

government, triggering the 1929 election. His action was motivated partly by his views on the obligations of an independent speaker, but he also disliked the bill, and he still resented his forced resignation in 1925.

Final years

The Nationalists expelled Groom from the party, forcing him to run for reelection as an independent. In a bitter campaign, Groom was eliminated on the first count, making him the first serving Speaker to lose his own seat at an election. Groom returned to his legal practice inBrisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

for two years. In 1931 election, he sought to take back his old seat. Running again as an independent, he handily defeated his successor, Arthur Morgan Arthur Morgan may refer to:

* Arthur Morgan (Australian politician, born 1856) (1856–1916), Premier of Queensland, Australia

* Arthur Ernest Morgan (1878–1975), American administrator, educator and engineer

* Arthur Morgan (Australian politici ...

. In a reversal of two years earlier, he won an outright majority on the first count. After two years as an independent, he joined the United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

, successor to the Nationalists, in August 1933. From 1932 to 1936 he was chairman of the Bankruptcy Legislation Committee and in earlier years he also acted on various royal commissions and select committees. He died in Canberra of cerebro-vascular disease. Groom was survived by his wife and one of their two daughters.

Other activities

Groom was joint author with

Groom was joint author with Sir John Quick

Sir John Quick (22 April 1852 – 17 June 1932) was an Australian lawyer, politician and judge. He played a prominent role in the movement for Federation and the drafting of the Australian constitution, later writing several works on Austra ...

of the ''Judicial Power of the Commonwealth'' in 1904 and he was part author of various Queensland legal publications.

A member of the General Synod of the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, Groom was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

in January 1924 for his services to politics. In 1984, his old seat of Darling Downs was renamed the Division of Groom

The Division of Groom is an Australian Electoral Division in Queensland.

Groom is an agricultural electorate located on the Darling Downs in southern Queensland. It includes the regional city of Toowoomba and rural communities to the west and ...

in his honour. He is commemorated by a number of features in Toowoomba

Toowoomba ( , nicknamed 'The Garden City' and 'T-Bar') is a city in the Toowoomba Region of the Darling Downs, Queensland, Australia. It is west of Queensland's capital city Brisbane by road. The urban population of Toowoomba as of the 2021 C ...

, including Groom Park.

Groom's elder brother, Henry Littleton Groom

Henry Littleton Groom (4 January 1860 – 4 January 1926) was a journalist, company director, and member of the Queensland Legislative Council.

Early life and business career

Groom was born at Toowoomba, Colony of Queensland,

, was a long serving member of the Queensland Legislative Council

The Queensland Legislative Council was the upper house of the parliament in the Australian state of Queensland. It was a fully nominated body which first took office on 1 May 1860. It was abolished by the Constitution Amendment Act 1921, which to ...

.

Legacy

After his death, Groom bequeathed many of the books from his personal library to the Canberra University College Library (which would become theAustralian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

's Chifley Library).

See also

*List of people with surname Groom

Groom is a surname of English origin. Its English usage comes from the trade or profession, a person responsible for the feeding and care of horses, not to be confused with the much more socially distinguished roles in the English Royal Household ...

* Members of the Parliament of Australia who have served for at least 30 years

This article lists the longest-serving members of the Parliament of Australia.

Longest total service

This section lists members of parliament who have served for a cumulative total of at least 30 years.

All these periods of service were spent i ...

References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Groom, Littleton Ernest 1867 births 1936 deaths Australian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Members of the Cabinet of Australia Attorneys-General of Australia Australian ministers for Foreign Affairs Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Darling Downs Members of the Australian House of Representatives Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Commonwealth Liberal Party members of the Parliament of Australia Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Independent members of the Parliament of Australia United Australia Party members of the Parliament of Australia Speakers of the Australian House of Representatives 20th-century Australian politicians Australian Ministers for Health