Literature of Birmingham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The literary tradition of

The literary tradition of

Little evidence remains of the culture of medieval Birmingham, but with a priory and two chantries in the town itself, another priory in

Little evidence remains of the culture of medieval Birmingham, but with a priory and two chantries in the town itself, another priory in  It is in the mid 17th century that the first evidence of a distinctive and sustained literary culture emerges within Birmingham, based around a group of writers working at the heart of the town's growth as a centre of religious puritanism and political radicalism. John Barton, the headmaster of King Edward's School, was the author of ''The Art of Rhetorick'' in 1634 and ''The Latine Grammar composed in the English Tongue'' in 1652, but is best known for ''Prince Rupert's burning love for England, discovered in Birmingham's flames'' – a widely circulated, influential and vitriolic anti-Royalist tract that documented the sacking of the town by

It is in the mid 17th century that the first evidence of a distinctive and sustained literary culture emerges within Birmingham, based around a group of writers working at the heart of the town's growth as a centre of religious puritanism and political radicalism. John Barton, the headmaster of King Edward's School, was the author of ''The Art of Rhetorick'' in 1634 and ''The Latine Grammar composed in the English Tongue'' in 1652, but is best known for ''Prince Rupert's burning love for England, discovered in Birmingham's flames'' – a widely circulated, influential and vitriolic anti-Royalist tract that documented the sacking of the town by

The most significant author associated with Birmingham during the enlightenment era was

The most significant author associated with Birmingham during the enlightenment era was  Although the Lunar Society of Birmingham is best known for its scientific discoveries and its influence on the industrial revolution, it also included several members notable as writers.

Although the Lunar Society of Birmingham is best known for its scientific discoveries and its influence on the industrial revolution, it also included several members notable as writers.  The 18th century saw Birmingham's written output diversify further from its earlier focus on religious polemic. William Hutton, though born in Derby, became Birmingham's first historian, publishing his ''History of Birmingham'' in 1782. The rationalist philosopher William Wollaston – best known for his 1722 work ''

The 18th century saw Birmingham's written output diversify further from its earlier focus on religious polemic. William Hutton, though born in Derby, became Birmingham's first historian, publishing his ''History of Birmingham'' in 1782. The rationalist philosopher William Wollaston – best known for his 1722 work '' The century also saw Birmingham emerge as the centre of a vibrant and sophisticated culture of popular

The century also saw Birmingham emerge as the centre of a vibrant and sophisticated culture of popular

The 19th century saw the short story and the novel emerge as major features of Birmingham's literary output. A transitional figure was

The 19th century saw the short story and the novel emerge as major features of Birmingham's literary output. A transitional figure was  Washington Irving, who was born in New York City and is regarded as the United States' first successful professional man of letters, spent many years in Birmingham after his first visit to the town in 1815, living with his sister and her husband in Ladywood, the Jewellery Quarter and Edgbaston. His best-known works – the short stories " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and " Rip Van Winkle" – were both written in Birmingham, as was his first and best-known novel ''

Washington Irving, who was born in New York City and is regarded as the United States' first successful professional man of letters, spent many years in Birmingham after his first visit to the town in 1815, living with his sister and her husband in Ladywood, the Jewellery Quarter and Edgbaston. His best-known works – the short stories " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and " Rip Van Winkle" – were both written in Birmingham, as was his first and best-known novel '' Protestant religion remained a theme common to much of Birmingham's literary output during the 19th century. ''

Protestant religion remained a theme common to much of Birmingham's literary output during the 19th century. ''

The Victorian period also saw authors with a Birmingham background produce fiction in a far broader range of genres.

The Victorian period also saw authors with a Birmingham background produce fiction in a far broader range of genres.  Edwin Abbott Abbott, who worked for a period as a schoolmaster at Birmingham's King Edward's School, was the author of a wide range of writings dominated by his highly imaginative theological works. He is best known, however, for the classic early science fiction work '' Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions'', which combined a

Edwin Abbott Abbott, who worked for a period as a schoolmaster at Birmingham's King Edward's School, was the author of a wide range of writings dominated by his highly imaginative theological works. He is best known, however, for the classic early science fiction work '' Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions'', which combined a

Although Victorian Birmingham was known as a stronghold of Protestant Nonconformism,

Although Victorian Birmingham was known as a stronghold of Protestant Nonconformism,  The most influential writer to be attracted to Oscott by Wiseman however was John Henry Newman, who was to become the outstanding Catholic literary figure of 19th century England and the major influence on the Catholic literary revival that was to follow. Newman moved to Birmingham shortly after his conversion from the Church of England in 1845, staying initially at Oscott before founding the

The most influential writer to be attracted to Oscott by Wiseman however was John Henry Newman, who was to become the outstanding Catholic literary figure of 19th century England and the major influence on the Catholic literary revival that was to follow. Newman moved to Birmingham shortly after his conversion from the Church of England in 1845, staying initially at Oscott before founding the  Oscott also produced writers whose relationship with their Catholic background was ambiguous or actively hostile, and who – often writing from exile – were to become leading figures of the

Oscott also produced writers whose relationship with their Catholic background was ambiguous or actively hostile, and who – often writing from exile – were to become leading figures of the

The romantic novelist Barbara Cartland, who was born in Edgbaston in 1901, was cited by the ''

The romantic novelist Barbara Cartland, who was born in Edgbaston in 1901, was cited by the ''

Jim Crace moved to Birmingham in 1965 to study at what is now Birmingham City University, where his contemporaries included the novelist and journalist Gordon Burn, whose later writing blurred the lines between fact and fiction to examine the trauma, spectacle and dysfunction of contemporary celebrity, and new gothic psychological novelist Patrick McGrath. Crace wrote short stories from the early 1970s and published his first novel ''Continent'' in 1986. Still living in Moseley in the south of the city, his reputation unusually combines both a broad popular readership and substantial acclaim among critics and academics. His work sits outside the social realist mainstream of English novelists, having more in common with European and South American authors such as Italo Calvino, Vladimir Nabokov, Franz Kafka,

Jim Crace moved to Birmingham in 1965 to study at what is now Birmingham City University, where his contemporaries included the novelist and journalist Gordon Burn, whose later writing blurred the lines between fact and fiction to examine the trauma, spectacle and dysfunction of contemporary celebrity, and new gothic psychological novelist Patrick McGrath. Crace wrote short stories from the early 1970s and published his first novel ''Continent'' in 1986. Still living in Moseley in the south of the city, his reputation unusually combines both a broad popular readership and substantial acclaim among critics and academics. His work sits outside the social realist mainstream of English novelists, having more in common with European and South American authors such as Italo Calvino, Vladimir Nabokov, Franz Kafka,

Harborne-based

Harborne-based

*

*

Google Books

/ref>

The literary tradition of

The literary tradition of Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

originally grew out of the culture of religious puritanism that developed in the town in the 16th and 17th centuries. Birmingham's location away from established centres of power, its dynamic merchant-based economy and its weak aristocracy gave it a reputation as a place where loyalty to the established power structures of church and feudal state were weak, and saw it emerge as a haven for free-thinkers and radicals, encouraging the birth of a vibrant culture of writing, printing and publishing.

The 18th century saw the town's radicalism widen to encompass other literary areas, and while Birmingham's tradition of vigorous literary debate on theological issues was to survive into the Victorian era, the writers of the Midlands Enlightenment

The Midlands Enlightenment, also known as the West Midlands Enlightenment or the Birmingham Enlightenment, was a scientific, economic, political, cultural and legal manifestation of the Age of Enlightenment that developed in Birmingham and the wide ...

brought new thinking to areas as diverse as poetry, philosophy, history, fiction and children's literature. By the Victorian era Birmingham was one of the largest towns in England and at the forefront of the emergence of modern industrial society

In sociology, industrial society is a society driven by the use of technology and machinery to enable mass production, supporting a large population with a high capacity for division of labour. Such a structure developed in the Western world i ...

, a fact reflected in its role as both a subject and a source for the newly dominant literary form of the novel. The diversification of the city's literary output continued into the 20th century, encompassing writing as varied as the uncompromising modernist fiction of Henry Green, the science fiction of John Wyndham, the popular romance of Barbara Cartland, the children's stories

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

of the Rev W. Awdry, the theatre criticism of Kenneth Tynan and the travel writing of Bruce Chatwin.

Writers with roots in Birmingham have had an international influence. John Rogers compiled the first complete authorised edition of The Bible to appear in the English Language; Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

was the leading literary figure of 18th century England and produced the first English Dictionary; J. R. R. Tolkien is the dominant figure in the genre of fantasy fiction and one of the bestselling authors in the history of the world; W. H. Auden's work has been called the greatest body of poetry written in the English Language over the last century; while notable contemporary writers from the city include David Lodge, Jim Crace, Roy Fisher

Roy Fisher (11 June 1930 – 21 March 2017) was an English poet and jazz pianist. His poetry shows an openness to both European and American modernist influences, while remaining grounded in the experience of living in the English Midlands. ...

and Benjamin Zephaniah.

The city also has a tradition of distinctive literary subcultures, from the Puritan writers who established the first Birmingham Library in the 1640s; through the 18th century philosophers, scientists and poets of the Lunar Society and the Shenstone Circle

The Shenstone Circle, also known as the Warwickshire Coterie, was a literary circle of poets living in and around Birmingham in England from the 1740s to the 1760s. At its heart lay the poet and landscape gardener William Shenstone, who lived at ' ...

; the Victorian Catholic revival writers associated with Oscott College

St Mary's College in New Oscott, Birmingham, often called Oscott College, is the Roman Catholic seminary of the Archdiocese of Birmingham in England and one of the three seminaries of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.

Purpose

Oscott Coll ...

and the Birmingham Oratory

The Birmingham Oratory is an English Catholic religious community of the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, located in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham. The community was founded in 1849 by St. John Henry Newman, Cong.Orat., the fi ...

; to the politically engaged 1930s writers of ''Highfield

Highfield may refer to:

Places

;Places in England

* Highfield, Bolton

* Highfield, Derbyshire

* Highfield, Gloucestershire

*Highfield, Southampton

*Highfield, Hertfordshire a neighbourhood in Hemel Hempstead

* Highfield, Oxfordshire

* Highfield, S ...

'' and the Birmingham Group. This tradition continues today, with notable groups of writers associated with the University of Birmingham, the Tindal Street Press, and the city's burgeoning crime fiction, science fiction and poetry scenes.

Medieval and early modern literature

Little evidence remains of the culture of medieval Birmingham, but with a priory and two chantries in the town itself, another priory in

Little evidence remains of the culture of medieval Birmingham, but with a priory and two chantries in the town itself, another priory in Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles from Birmingham City Centre.

History

Aston wa ...

, grammar schools in Deritend, Yardley and King's Norton, and the religious institutions of the Guild of the Holy Cross and the Guild of St. John, Deritend

The Guild or Gild of St John the Baptist was an English medieval religious guild in Deritend - an area of the manor of Birmingham within the parish of Aston. It maintained the priest of St John's Chapel, Deritend as its own chaplain, paying his st ...

, the area would have supported a substantial community of learned religious men from the 13th century onwards.

The first Birmingham literary figure of lasting significance was John Rogers, who was born in Deritend in 1500 and educated at the Grammar School of the Guild of St. John, and who compiled, edited and partially translated the 1537 '' Matthew Bible'', the first complete authorised version of the Bible to be printed in the English language. This was the most influential of the early English printed Bibles, providing the basis for the later '' Great Bible'' and ''Authorized King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

''. Rogers' translation of Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

's ''Weighing of the Interim'' probably took place between Rogers' return to Deritend from Wittenberg in 1547 and his move to London in 1550, and is the earliest book written by a Birmingham author known to have been printed in England. Rogers' profile as a prominent figure in the Protestant church led to his arrest after the restoration of Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

by Mary I, and on 14 February 1555 he became the first Protestant to be burned at the stake in the Marian Persecutions, leaving behind a written account of his three interrogations that was to establish him as an icon of martyrdom and the refusal to recant one's individual conscience. The poem he left to his children at his death, exhorting them to a Godly life and including his famous instruction for them to "Abhor that arrant Whore of Rome", was included in '' The New England Primer'' of 1690, becoming a major influence on the Puritan educational outlook of 18th century Colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

.

It is in the mid 17th century that the first evidence of a distinctive and sustained literary culture emerges within Birmingham, based around a group of writers working at the heart of the town's growth as a centre of religious puritanism and political radicalism. John Barton, the headmaster of King Edward's School, was the author of ''The Art of Rhetorick'' in 1634 and ''The Latine Grammar composed in the English Tongue'' in 1652, but is best known for ''Prince Rupert's burning love for England, discovered in Birmingham's flames'' – a widely circulated, influential and vitriolic anti-Royalist tract that documented the sacking of the town by

It is in the mid 17th century that the first evidence of a distinctive and sustained literary culture emerges within Birmingham, based around a group of writers working at the heart of the town's growth as a centre of religious puritanism and political radicalism. John Barton, the headmaster of King Edward's School, was the author of ''The Art of Rhetorick'' in 1634 and ''The Latine Grammar composed in the English Tongue'' in 1652, but is best known for ''Prince Rupert's burning love for England, discovered in Birmingham's flames'' – a widely circulated, influential and vitriolic anti-Royalist tract that documented the sacking of the town by Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cavalr ...

at the Battle of Birmingham

The Battle of Camp Hill (or the Battle of Birmingham) took place on Easter Monday, 3 April 1643, in and around Camp Hill, Warwickshire, during the First English Civil War. In the skirmish, a company of Parliamentarians from the Lichfield garr ...

of 1643. Anthony Burgess wrote numerous sermons and theological works while the rector of Sutton Coldfield

Sutton Coldfield or the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, known locally as Sutton ( ), is a town and civil parish in the City of Birmingham, West Midlands, England. The town lies around 8 miles northeast of Birmingham city centre, 9 miles south ...

between 1635 and 1662, entering into a prolonged if amicable theological dispute in print with Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter (12 November 1615 – 8 December 1691) was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymnodist, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he ...

that culminated in a face-to-face debate in Birmingham in September 1650. Francis Roberts was similarly prolific during his tenure as vicar of Birmingham's St Martin in the Bull Ring

St Martin in the Bull Ring is a Church of England parish church in the city of Birmingham, West Midlands, England. It is the original parish church of Birmingham and stands between the Bull Ring Shopping Centre and the markets.

The church is ...

, with many of his works of popular or scholarly theology becoming nationally-known and running through numerous editions. Thomas Hall Thomas Hall may refer to:

Politicians

*Thomas Hall (North Dakota politician) (1869–1958), American U.S. congressman for North Dakota

* Thomas Hall (Ohio politician), Ohio state Representative

*Thomas Hall (MP for Lincolnshire) (1619–1667), MP ...

was the master of the King's Norton Grammar School from 1629, and the minister of the adjacent St Nicolas' Church from 1650, but from the 1630s onwards was drawn into the radical circles of nearby Birmingham. He was the author of a long series of polemical works, combining both populist and erudite writing on religious and social matters. His 1652 volume ''The Font Guarded'' – a defence of the practice of infant baptism – was the first book known to have been published as well as written in Birmingham, and provides the first definite evidence of booksellers operating within the town. Between 1635 and 1642 Roberts, Hall and Barton were involved in establishing the first Birmingham Library, one of the earliest public libraries in England.

This culture of radical writing grew with the influx of Nonconformists and ejected ministers

The Great Ejection followed the Act of Uniformity 1662 in England. Several thousand Puritan ministers were forced out of their positions in the Church of England, following The Restoration of Charles II. It was a consequence (not necessaril ...

seeking asylum in Birmingham following the Act of Uniformity of 1662 and the Five Mile Act of 1665, which forbade dissenting ministers from living within five miles of a chartered borough but didn't apply to highly populous but unincorporated Birmingham. A vast number of essays and printed sermons on issues of religious controversy were produced by these radical clerics and their opponents over the following decades, in turn encouraging the further growth of the town's book trade. The era also saw the birth of a Birmingham street literature

Street literature is any of several different types of publication sold on the streets, at fairs and other public gatherings, by travelling hawkers, pedlars or chapmen, from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Robert Collison's account of t ...

, with broadside ballads

A broadside (also known as a broadsheet) is a single sheet of inexpensive paper printed on one side, often with a ballad, rhyme, news and sometimes with woodcut illustrations. They were one of the most common forms of printed material between the ...

on Birmingham subjects surviving from the middle years of the 17th century. An Act of Parliament restricting the number of master printers in England meant that literature written and published in Birmingham could not be printed in the town, however, being produced only in London until the Act was repealed in 1693.

Literature of the Midlands Enlightenment

Birmingham during the 18th century lay at the heart of the English experience of the Age of Enlightenment, as the free-thinking dissenting tradition developed in the town over the previous century blossomed into the cultural movement now known as theMidlands Enlightenment

The Midlands Enlightenment, also known as the West Midlands Enlightenment or the Birmingham Enlightenment, was a scientific, economic, political, cultural and legal manifestation of the Age of Enlightenment that developed in Birmingham and the wide ...

. Birmingham's literary infrastructure grew dramatically over the period. At least seven booksellers are recorded as existing by 1733 with the largest in 1786 claiming a stock of 30,000 titles in several languages. Books could be borrowed from the eight or nine commercial lending libraries established over the course of the 18th century, and from more specialist research-driven libraries such as the Birmingham Library and St. Philip's Parish Library

St. Philip's Parish Library, also known as the Higgs Library, was a public library attached to St Philip's Church in Birmingham, England between 1733 and 1927.

The library was founded in 1733 by St. Philip's first rector William Higgs and was base ...

. Evidence of printers working in Birmingham can be found from 1713, and the rise of John Baskerville

John Baskerville (baptised 28 January 1707 – 8 January 1775) was an English businessman, in areas including japanning and papier-mâché, but he is best remembered as a printer and type designer. He was also responsible for inventing "wov ...

in the 1750s saw the town's printing and publishing industry achieve international significance. By the end of the century Birmingham had developed a highly literate society, and it was claimed that the town's population of around 50,000 read 100,000 books per month.

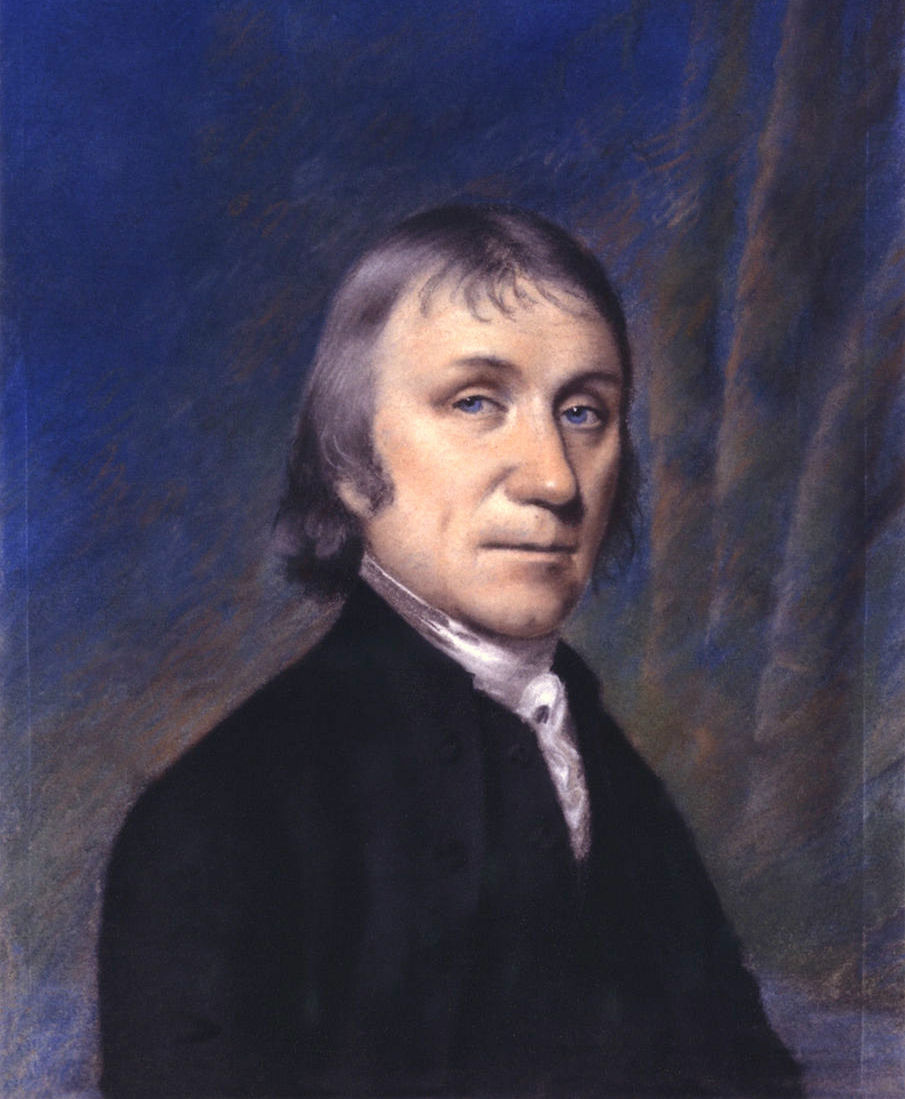

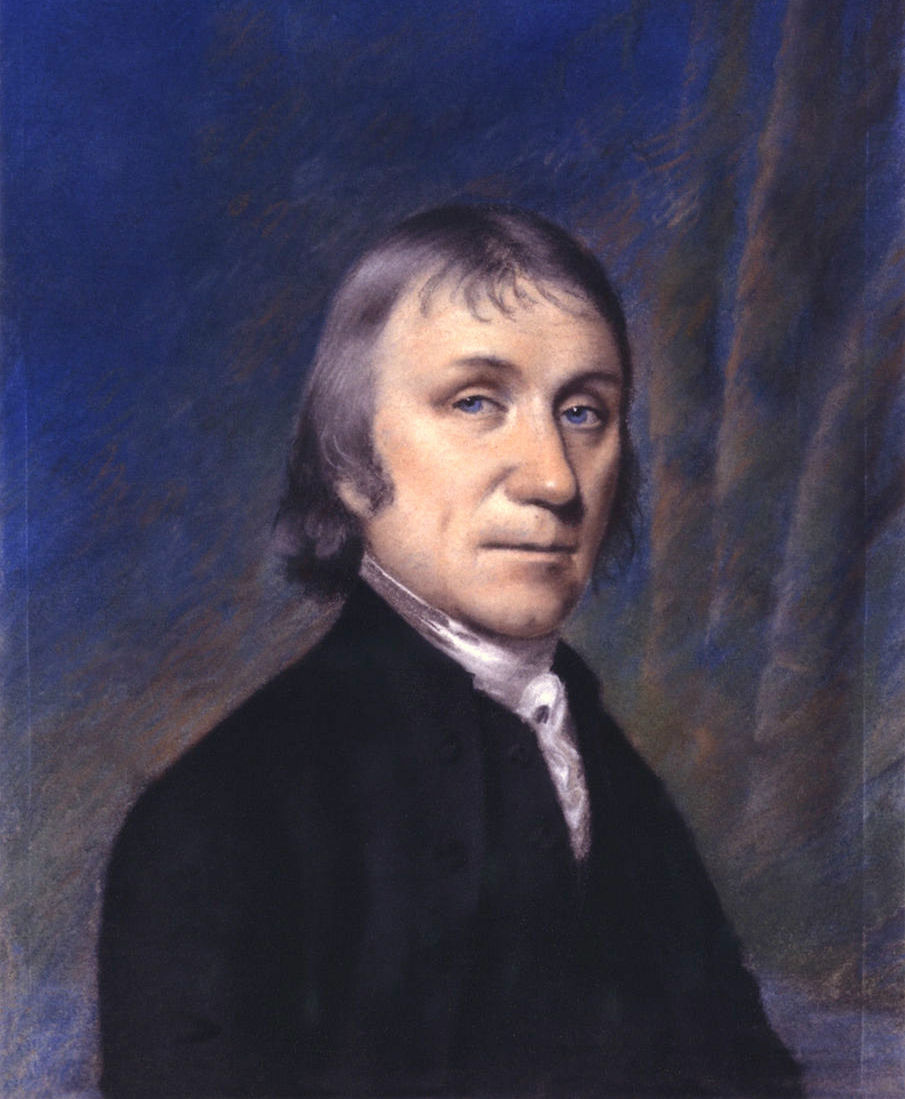

The most significant author associated with Birmingham during the enlightenment era was

The most significant author associated with Birmingham during the enlightenment era was Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

: poet, novelist, literary critic, journalist, satirist and biographer, the author of the first English Dictionary; the leading literary figure of the 18th century and "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history". Johnson's background was closely tied to Birmingham and its book trade: his father maintained a bookstall on the Birmingham Market, his uncle and brother were both booksellers in the town, his mother was a native of King's Norton, and his wife Elizabeth ("Tetty"), whom he married when both were living in the town in 1735, was the widow of Henry Porter, a Birmingham merchant. Johnson's own literary career started in Birmingham where he lived for three years from 1732 after failing to establish himself as a teacher in his native Lichfield. His essays for Thomas Warren's '' Birmingham Journal'' were his first published writing, and it was in Birmingham – also for Warren – that he wrote and had published his first book: a translation of Jerónimo Lobo's ''A Voyage to Abyssinia''. This "combination of the travelogue and religious polemic", with a preface written by Johnson himself, was pitched towards the dissenting culture of the Birmingham area and its widespread suspicion of religious fanaticism, but also aligned Johnson with the empirical and renaissance humanist tradition of the post-reformation European intellectual elite, themes that would emerge repeatedly throughout his following work. This early work also established Johnson's practice of building his literary output around adapting and responding to the work of others – "a sort of rhetoric applied to the print world" – that was to form the basis of his prodigious output over the course of his career. Johnson maintained an extensive set of social and business connections in Birmingham throughout his lifetime and continued to visit the town regularly until a month before his death in 1784.

Although the Lunar Society of Birmingham is best known for its scientific discoveries and its influence on the industrial revolution, it also included several members notable as writers.

Although the Lunar Society of Birmingham is best known for its scientific discoveries and its influence on the industrial revolution, it also included several members notable as writers. Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

's 1791 poem ''The Botanic Garden

''The Botanic Garden'' (1791) is a set of two poems, ''The Economy of Vegetation'' and ''The Loves of the Plants'', by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. ''The Economy of Vegetation'' celebrates technological innovation and scien ...

'' established him for a period as the leading English poet of his day, and was a major influence on the Romantic poetry of William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

, and John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculo ...

. Thomas Day Thomas Day may refer to:

Sports

* Tom Day (rugby union) (1907–1980), Welsh rugby union player

* Tom Day (American football) (1935–2000), American football player

* Tom Day (footballer) (born 1997), English footballer

Others

* Thomas Day (wri ...

– an ardent follower of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau – wrote an early series of radical poems including the anti-slavery work ''The Dying Negro

''The Dying Negro: A Poetical Epistle'' was a 1773 abolitionist poem published in England, by John Bicknell and Thomas Day. It has been called "the first significant piece of verse propaganda directed explicitly against the English slave systems". ...

'' (with John Bicknell

John Bicknell, the elder (baptised 1746 – 27 March 1787), was an English barrister and writer. He was co-author with Thomas Day of the abolitionist poem '' The Dying Negro'' from 1773. Bicknell has also been credited with ''Musical Travels thro ...

) in 1773, and a passionate defence of the American Revolution ''The Devoted Legions'' in 1776. He is however best known for his books for children, particularly his 1789 work '' Sandford and Merton'', which remained the most widely read and influential children's book for a century after its publication, and whose proto-socialist outlook was "to play a crucial role in moulding the ethos of nineteenth-century England". Joseph Priestley wrote voluminously on an exceptionally wide range of subjects including theology, history, education and rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

. As a philosopher he had considerable contemporary influence, arguing for materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

, determinist

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

and scientific realist viewpoints and influencing the thought of Richard Price, Thomas Reid and Immanuel Kant. His political writings centred around the ideas of providentialism and the importance of individual liberty, while his work '' The Rudiments of English Grammar'' established him as "one of the great grammarians of his time."

The 18th century saw Birmingham's written output diversify further from its earlier focus on religious polemic. William Hutton, though born in Derby, became Birmingham's first historian, publishing his ''History of Birmingham'' in 1782. The rationalist philosopher William Wollaston – best known for his 1722 work ''

The 18th century saw Birmingham's written output diversify further from its earlier focus on religious polemic. William Hutton, though born in Derby, became Birmingham's first historian, publishing his ''History of Birmingham'' in 1782. The rationalist philosopher William Wollaston – best known for his 1722 work ''The Religion of Nature Delineated

The ''Religion of Nature Delineated'' is a book by Anglican cleric William Wollaston that describes a system of ethics that can be discerned without recourse to revealed religion. It was first published in 1722, two years before Wollaston's death. ...

'' – was a master for a period at the Birmingham Grammar School

King Edward's School (KES) is an independent day school for boys in the British public school tradition, located in Edgbaston, Birmingham. Founded by King Edward VI in 1552, it is part of the Foundation of the Schools of King Edward VI in Birm ...

. The poet Charles Lloyd was born in Birmingham, the son of one of the partners in Lloyds Bank. Noted for his radicalism, he was a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Lamb, William Wordsworth, Robert Southey and Thomas de Quincey; and was widely attacked by conservative publicists in the aftermath of the French Revolution for poems such as his 1798 ''Blank Verse'', celebrating "the promis'd time … when equal man / Shall deem the world his temple". Henry Francis Cary

The Reverend Henry Francis Cary (6 December 1772 – 14 August 1844) was a British nationality, British author and translator, best known for his blank verse translation of ''The Divine Comedy'' of Dante.Richard Garnett (1887). "wikisource:Di ...

, a translator best known for his version of Dante's '' Divine Comedy'', was educated at grammar schools in Sutton Coldfield and Birmingham during the 1780s and published a volume of ''Odes & Sonnets'' in 1788 while at the latter. The poet William Shenstone had houses in Birmingham and Quinton as well as his famous estate '' The Leasowes'' to the west of Birmingham near Halesowen. He lay at the centre of the Shenstone Circle

The Shenstone Circle, also known as the Warwickshire Coterie, was a literary circle of poets living in and around Birmingham in England from the 1740s to the 1760s. At its heart lay the poet and landscape gardener William Shenstone, who lived at ' ...

– a group of writers and poets from the Birmingham area that included Richard Jago

Richard Jago (1 October 1715 – 8 May 1781) was an English clergyman poet and minor landscape gardener from Warwickshire. Although his writing was not highly regarded by contemporaries, some of it was sufficiently novel to have several imitators ...

, John Scott Hylton, John Pixell

John Prynne Parkes Pixell (1725 – 1784) was an English poet, priest and composer.

Background

Pixell was educated at the Birmingham Free School and at Queen's College, Oxford. He became the vicar of Edgbaston in 1751,

Published works

One of h ...

, Richard Graves, Mary Whateley

Mary Darwall (née Whateley; 1738 – 5 December 1825), who sometimes wrote as Harriett Airey, was an English poet and playwright. She belonged to the Shenstone Circle of writers gathered round William Shenstone in the English Midlands. She late ...

and Joseph Giles – a role that saw him described as the " Maecenas of the Midlands".

The century also saw Birmingham emerge as the centre of a vibrant and sophisticated culture of popular

The century also saw Birmingham emerge as the centre of a vibrant and sophisticated culture of popular street literature

Street literature is any of several different types of publication sold on the streets, at fairs and other public gatherings, by travelling hawkers, pedlars or chapmen, from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Robert Collison's account of t ...

, as the town's printers produced increasing numbers of the broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s and chapbooks that formed the primary reading matter of the poor. Cheaply printed and carrying traditional songs, newly written ballads on topical matters, simple folk-tales with wood-cut illustrations, and news – particularly salacious coverage of gruesome crimes, executions, riots and wars – broadsides and chapbooks were sold or exchanged by itinerant chapmen – also called "patterers" or "ballad-mongers" – who often displayed their goods in the street on a small table or pinned to a wall. Although much of this work was by its nature ephemeral and low in literary quality, Birmingham was unusual in that the town's high level of social mobility

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society ...

meant that printers of street literature often overlapped with printers of weightier material, some writers of street literature were highly educated and of respectable social standing, and several writers of Birmingham broadside ballads had a lasting influence on the town's literary culture. Job Nott – probably a pseudonym of Theodore Price of Harborne – was a largely conservative figure who produced a wide range of pamphlets and broadsides on topical matters, attracting imitators as far afield as Bristol. John Freeth

John Freeth (1731 – 29 September 1808), also known as Poet Freeth and who published his work under the pseudonym John Free, was an English innkeeper, poet and songwriter. As the owner of Freeth's Coffee House between 1768 and his death in 1808, ...

's influence was even greater: nearly 400 of his political ballads were published and distributed nationally in a dozen separate collections between 1766 and 1805, the best-known being his 1790 collection ''The Political Songster''. An outstanding figure in the radical circles of the late-Georgian town, he hosted the Birmingham Book Club

The Birmingham Book Club, known to its opponents during the 1790s as the Jacobin Club due to its political radicalism, and at times also as the Twelve Apostles, was a book club and debating society based in Birmingham, England from the 18th to th ...

at John Freeth's Coffee House, giving him a national political importance and placing him at the heart of Birmingham's developing political self-consciousness during the upheavals of the American Revolution.

Regency and Victorian literature

19th century fiction

The 19th century saw the short story and the novel emerge as major features of Birmingham's literary output. A transitional figure was

The 19th century saw the short story and the novel emerge as major features of Birmingham's literary output. A transitional figure was Catherine Hutton

Catherine Hutton (11 February 1756 – 13 March 1846) was an English novelist and letter-writer.

Born in Birmingham, the daughter of historian William Hutton, Hutton became a friend of the scientist and discoverer of oxygen Joseph Priestley a ...

, the daughter of Birmingham historian William Hutton, who was first notable as a correspondent of many of the leading literary figures of the late 18th century, but who published her first novel ''The Miser Married'' in 1813. This was itself written as a series of 63 letters discussing personal, social and literary issues among the fictional correspondents, and was followed by two further epistolary novels – ''The Welsh Mountaineers'' in 1817 and ''Oakwood Hall'' in 1819.

Washington Irving, who was born in New York City and is regarded as the United States' first successful professional man of letters, spent many years in Birmingham after his first visit to the town in 1815, living with his sister and her husband in Ladywood, the Jewellery Quarter and Edgbaston. His best-known works – the short stories " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and " Rip Van Winkle" – were both written in Birmingham, as was his first and best-known novel ''

Washington Irving, who was born in New York City and is regarded as the United States' first successful professional man of letters, spent many years in Birmingham after his first visit to the town in 1815, living with his sister and her husband in Ladywood, the Jewellery Quarter and Edgbaston. His best-known works – the short stories " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and " Rip Van Winkle" – were both written in Birmingham, as was his first and best-known novel ''Bracebridge Hall

''Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists, A Medley'' was written by Washington Irving in 1821, while he lived in England, and published in 1822. This episodic novel was originally published under his pseudonym Geoffrey Crayon.

Plot introduction

As t ...

'' of 1821, whose setting was loosely based on Birmingham's Aston Hall. Many of his later works, including '' Tales of the Alhambra'' and ''Mahomet and His Successors'', were completed in Birmingham after being drafted on his wider European travels. Thomas Adolphus Trollope worked as a schoolteacher in Birmingham before establishing himself as a successful novelist, journalist and travel writer and moving to Florence in Italy, where his house became a magnet for British literary figures such as Charles Dickens, George Eliot and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (née Moulton-Barrett; 6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was an English poet of the Victorian era, popular in Britain and the United States during her lifetime.

Born in County Durham, the eldest of 12 children, Elizabet ...

. Isabella Varley Banks was born in Manchester and is best known for her 1876 novel '' The Manchester Man'', but her career as a novelist started only after she moved to Birmingham in 1846 after marrying local journalist, poet and playwright George Linnaeus Banks

George Linnaeus Banks (2 March 1821 – 3 May 1881), husband of author Isabella Banks, was a British journalist, editor, poet, playwright, amateur actor, orator, and Methodist.

George was born in Birmingham, the son of a seedsman familiar wi ...

. Her twelve novels were set in a variety of locations including Birmingham, Yorkshire, Wiltshire, Durham, Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, and Manchester; each book being particularly notable for its faithful reproduction of local dialect and pronunciation. West Bromwich-born David Christie Murray received his training as a writer as a journalist under George Dawson George Dawson may refer to:

Politicians

* George Dawson (Northern Ireland politician) (1961–2007), Northern Ireland politician

* George Walker Wesley Dawson (1858–1936), Canadian politician

* George Oscar Dawson (1825–1865), Georgia politic ...

on the '' Birmingham Daily Post''. Several of his novels were set in Birmingham including ''A Rising Star'' of 1894 – the story of a Birmingham reporter with literary aspirations – with many more set in surrounding areas such as the Black Country

The Black Country is an area of the West Midlands county, England covering most of the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell and Walsall. Dudley and Tipton are generally considered to be the centre. It became industrialised during its ro ...

and Cannock Chase.

Protestant religion remained a theme common to much of Birmingham's literary output during the 19th century. ''

Protestant religion remained a theme common to much of Birmingham's literary output during the 19th century. ''John Inglesant

''John Inglesant'' is a celebrated historical novel by Joseph Henry Shorthouse, published in 1881, and set mainly in the middle years of the 17th century.

The eponymous hero is an Anglican, despite being educated partly by Jesuits, and remains ...

'' – the "philosophical romance" that was the first and best-known work of the Birmingham novelist Joseph Henry Shorthouse

Joseph Henry Shorthouse (9 September 1834 – 4 March 1903) was an English novelist.Barbara Dennis, "Shorthouse, Joseph Henry (1834–1903)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 200accessed 30 Nov 2012 doi:10.1093/r ...

– became a publishing triumph in the atmosphere of highly charged religious controversy of the 1880s, seeing its author "fêted throughout the literary world", the object of admiration from writers as varied as Charlotte Mary Yonge, T. H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

and Edmund Gosse, and the subject of an invitation to breakfast at 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London, also known colloquially in the United Kingdom as Number 10, is the official residence and executive office of the first lord of the treasury, usually, by convention, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Along wi ...

by William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

. The result of 30 years of study and over 10 years of writing, the novel told the story of a 17th-century English soldier and diplomat, his travels through England and Italy and his excursions through the principal religious philosophies of the time – Puritanism, Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, Quietism and Humanism – as a recreation of Shorthouse's own intellectual journey from Quakerism to the Church of England . Shorthouse wrote four other novels and a book of short stories over subsequent years, all of which catalogued their protagonists "protracted torments of conscience". Emma Jane Guyton

Emma Jane Guyton or Worboise (née Worboys; 1825–1887) was an English novelist, biographer and editor. Her more than 50 novels feature strong Christian values and were popular in their time.

Life

Guyton was born Emma Jane Worboys in Birmingham ...

published over fifty popular and oft-reprinted novels between 1846 and 1882, most of which used their commonplace domestic settings to communicate an ecumenical Protestant or strongly anti-Catholic message. Ashted

Ashted (alternatively spelt ''Ashstead'' and ''Ashtead'') is an area of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, within the ward of Nechells. The area is located approximately north-east of Birmingham City Centre near to the city's Eastside district, ...

-born George Mogridge started writing for children on religious and moral issues in 1827 after a varied early life that included periods working as a japanner

Japanning is a type of finish that originated as a European imitation of East Asian lacquerwork. It was first used on furniture, but was later much used on small items in metal. The word originated in the 17th century. American work, with the ...

in Birmingham's metal trades and living as a tramp in France. He eventually wrote 226 successful and widely marketed books, including stories, collections, verse and plays; anonymously and under more than 20 pseudonyms including Old Humphrey, Ephraim Holding, Old Father Thames, Peter Parley, Grandfather Gregory, Amos Armfield, Grandmamma Gilbert, Aunt Upton, and X.Y.Z. At the time of his death in 1854 it was estimated that his books had sold a total of over 15 million copies across Britain and America.

The Victorian era also saw Birmingham featuring as a setting for novelists from outside the town, placing it at the forefront of the fictional representation of industrial England's major urban centres. Five years before Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer and short story writer. Her novels offer a detailed portrait of the lives of many st ...

's 1848 portrayal of Manchester in '' Mary Barton'', and nine years before Charles Dickens' ''Hard Times

Hard may refer to:

* Hardness, resistance of physical materials to deformation or fracture

* Hard water, water with high mineral content

Arts and entertainment

* ''Hard'' (TV series), a French TV series

* Hard (band), a Hungarian hard rock supe ...

'' was loosely set in Preston

Preston is a place name, surname and given name that may refer to:

Places

England

*Preston, Lancashire, an urban settlement

**The City of Preston, Lancashire, a borough and non-metropolitan district which contains the settlement

**County Boro ...

, Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna gave a graphic depiction of working life in Birmingham in her 1843 four-part novel ''The Wrongs of Woman'', emphasising the exploitation of women in backstreet factories and the corrosive influence of industrial employment. The anonymously-written 1848 novella ''How to Get on in the World: The Story of Peter Lawley'' presented a more optimistic view, showing the positive consequences of learning to read for the poverty-stricken son of a Birmingham nailer. George Gissing's ''Eve's Ransom

''Eve's Ransom'' is a novel by George Gissing, first published in 1895 as a serialisation in the ''Illustrated London News''. It features the story of a mechanical draughtsman named Maurice Hilliard, who comes into some money, which enables him to ...

'' of 1894 presented Birmingham as a bustling metropolis of questionable values, with traffic "speedily passing from the region of main streets and great edifices into a squalid district of factories and workshops and crowded by-ways", while Mabel Collins

Mabel Collins (9 September 1851 – 31 March 1927) was a British theosophist and author of over 46 books.

Life

Collins was born in St Peter Port, Guernsey. She was a writer of popular occult novels, a fashion writer and an anti-vivisection campa ...

used ''Birchampton'' – a thinly disguised Birmingham – as the setting for her gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror in the 20th century, is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name is a reference to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of ea ...

''The Star Sapphire'' of 1896. Passing references in more widely set fiction also provide evidence of Birmingham's growing significance in the culture of Victorian England. Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

's 1845 novel ''Sybil

Sibyls were oracular women believed to possess prophetic powers in ancient Greece.

Sybil or Sibyl may also refer to:

Films

* ''Sybil'' (1921 film)

* ''Sybil'' (1976 film), a film starring Sally Field

* ''Sybil'' (2007 film), a remake of the 19 ...

'' uses Birmingham as a background political barometer – "They're always ready for a riot in Birmingham… The sufferings of '39 will keep Birmingham in check", while Charlotte Brontë's 1849 '' Shirley'' sees the town at the root of the changes sweeping England – "In Birmingham I considered closely, and at their source, the causes of the present troubles of this country".

Crime fiction, science fiction and other genre fiction

The Victorian period also saw authors with a Birmingham background produce fiction in a far broader range of genres.

The Victorian period also saw authors with a Birmingham background produce fiction in a far broader range of genres. Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

, the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

, started his career as a writer in Birmingham. His first story "The Mystery of Sasassa Valley" was written and published in 1879 while he was working as a medical assistant in Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles from Birmingham City Centre.

History

Aston wa ...

, as was his second "The American's Tale", whose success led his editor to advise him to give up medicine and pursue a full-time literary career. Birmingham appears in Conan Doyle's early stories as ''Birchespool'', and several of Conan Doyle's later Sherlock Holmes stories, including "The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk

"The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk" is one of the 56 short Sherlock Holmes stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It is the fourth of the twelve collected in ''The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes'' in most British editions of the canon, ...

" and "The Adventure of the Three Garridebs

"The Adventure of the Three Garridebs" is one of the 56 Sherlock Holmes short stories written by British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. One of the 12 stories in the cycle collected as ''The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes'' (1927), it was first pu ...

", have explicit Birmingham settings.

Edwin Abbott Abbott, who worked for a period as a schoolmaster at Birmingham's King Edward's School, was the author of a wide range of writings dominated by his highly imaginative theological works. He is best known, however, for the classic early science fiction work '' Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions'', which combined a

Edwin Abbott Abbott, who worked for a period as a schoolmaster at Birmingham's King Edward's School, was the author of a wide range of writings dominated by his highly imaginative theological works. He is best known, however, for the classic early science fiction work '' Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions'', which combined a satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

treatment of contemporary social class structures and gender roles, a deep expression of his own religious principles, and a speculative exploration of geometrical dimensions that anticipates Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. Louisa Baldwin wrote poetry, two collections of children's stories and four novels for adults; but is most highly regarded for her gothic ghost stories

A ghost story is any piece of fiction, or drama, that includes a ghost, or simply takes as a premise the possibility of ghosts or characters' belief in them."Ghost Stories" in Margaret Drabble (ed.), ''Oxford Companion to English Literature''. ...

, which were originally published in literary magazines but were collected together and published as ''The Shadow on the Blind'' by John Lane in 1895.

The imaginative adventure novels of Max Pemberton, the Edgbaston-born son of a Birmingham brass foundry owner, sold vastly well, from ''The Iron Pirate'' of 1893, a seafaring tale of ironclad buccaneers, to ''The Garden of Swords'', an 1899 story of the Franco-Prussian War. This swashbuckling genre was also represented by the highly successful 1884 novel ''The Adventures of Maurice Drummore (Royal Marines) by Land and Sea'', which claimed to be written by Linden Meadows and illustrated by F. Abell, though both in fact were pseudonyms of the Birmingham-born Charles Butler Greatrex.

The literary output of the Canadian-born author Grant Allen

Charles Grant Blairfindie Allen (February 24, 1848 – October 25, 1899) was a Canadian science writer and novelist, educated in England. He was a public promoter of evolution in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Biography Early life a ...

, who was brought up in Birmingham from the age of 13 and attended King Edward's School, was prodigious and varied even by Victorian standards. The Scottish critic Andrew Lang called him "the most versatile, beyond comparison, of any man in our age". Allen is best known for his best-selling but controversial 1895 novel ''The Woman Who Did

''The Woman Who Did'' (1895) is a novel by Grant Allen about a young, self-assured middle-class woman who defies convention as a matter of principle and who is fully prepared to suffer the consequences of her actions. It was first published in Lo ...

'', whose tragic plot combined support for free love with opposition to the institution of marriage, and whose success scandalised Victorian society. He is also noted for innovations in detective fiction

Detective fiction is a subgenre of crime fiction and mystery fiction in which an investigator or a detective—whether professional, amateur or retired—investigates a crime, often murder. The detective genre began around the same time as s ...

, creating independent-minded female detectives modelled on the feminist ideal of the New Woman in ''Miss Cayley's Adventures''; and for playing with the conventions of the crime genre in ''An African Millionaire'', where the criminal is the hero, and the short story "The Great Ruby Robbery", where the culprit turns out to be the detective investigating the crime. Allen's incorporation of his own scientific preoccupations into novels such as the time travel-based ''The British Barbarians'' also made him an important early pioneer of science fiction. H. G. Wells later wrote to him, acknowledging that "this field of scientific romance with a philosophical element that I am trying to cultivate, properly belongs to you."

Oscott, Newman and the Catholic literary revival

Although Victorian Birmingham was known as a stronghold of Protestant Nonconformism,

Although Victorian Birmingham was known as a stronghold of Protestant Nonconformism, St. Mary's College, Oscott

St Mary's College in New Oscott, Birmingham, often called Oscott College, is the Roman Catholic seminary of the Archdiocese of Birmingham in England and one of the three seminaries of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.

Purpose

Oscott Co ...

in the north of the city lay at the heart of the mid-19th century revival of English Catholicism. The college built a reputation for Catholic literary scholarship after Thomas Walsh brought major collections of Renaissance scholarship including the Harvington Library and the Marini Library to the college in the 1830s, and in 1840 Nicholas Wiseman was appointed the college's rector. As a man of wide cultural achievements and a prolific author himself, Wiseman established the college as the favoured educational establishment of the country's Catholic social and intellectual elite, attracting many students who would become leading figures of the Catholic literary revival that would follow. William Barry, who was educated at Oscott as a boy and later returned as Professor of Theology, has been dubbed "the creator of the English Catholic novel". His provocative, controversial and often witty books varied from ''The New Antigone'' of 1887 – a cutting attack on socialism, atheism, free love and the cult of the New Woman – to the more overtly Catholic ''The Two Standards'' of 1898, and ''The Wizard's Knot'' of 1901 – a satire on the Celtic Revival. Alfred Austin

Alfred Austin (30 May 1835 – 2 June 1913) was an English poet who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1896, after an interval following the death of Tennyson, when the other candidates had either caused controversy or refused the honour. It was cl ...

, who studied at Oscott in the 1840s, succeeded Tennyson as Poet Laureate in 1896, though it was widely believed that this had more to do with his support for the Tory Party than for his literary merit. Lord Acton became the editor of the Catholic monthly '' The Rambler'', a trusted advisor to William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and one of the leading liberal historians of the 19th century, best known for his editorship of the monumental ''Cambridge Modern History''. The "first great modern philosopher of resistance to the state", he was the originator of the famous aphorism "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely". An Oscott student under Wiseman, Acton later remarked on the international influence of the college at the time: "apart from Pekin, Oscott was the centre of the world".

Birmingham Oratory

The Birmingham Oratory is an English Catholic religious community of the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, located in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham. The community was founded in 1849 by St. John Henry Newman, Cong.Orat., the fi ...

in Edgbaston in 1849. Living at the Oratory almost continuously until his death in 1890, his major works written in Birmingham include the autobiographical '' Apologia Pro Vita Sua'', the novel ''Loss and Gain

''Loss and Gain'' is a philosophical novel by John Henry Newman published in 1848. It depicts the culture of Oxford University in the mid-Victorian era and the conversion of a young student to Roman Catholicism. The novel went through nine editi ...

'', his principal philosophical work ''Grammar of Assent

''An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent'' (commonly abbreviated to the last three words) is John Henry Newman's seminal book on the philosophy of faith."NEWMAN, John Henry", in ''Chambers Biographical Dictionary'' (1990), Edinburgh: Chambers. ...

'', and the poem '' The Dream of Gerontius'', later set to music by Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

. Under Newman the Oratory became the focus of a literary culture itself, attracting further Catholic writers of note. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins

Gerard Manley Hopkins (28 July 1844 – 8 June 1889) was an English poet and Jesuit priest, whose posthumous fame placed him among leading Victorian poets. His prosody – notably his concept of sprung rhythm – established him as an innovato ...

taught at The Oratory School when he graduated and converted to Catholicism in 1867; it was here that he was to first develop the ideas of inscape and instress that were to prove central to his poetic practice. The novelist, poet and polemicist Hilaire Belloc came from a long line of Birmingham radicals – his mother was Bessie Rayner Parkes, his grandfather Joseph Parkes and his great-great grandfather Joseph Priestley. He studied at the Oratory School from 1880 to 1886, and it was there he wrote his first published work ''Buzenval''. The poet Edward Caswall lived at the Oratory from 1852 until his death in 1878, writing his major works ''Lyra Catholica'' and ''The Masque of Mary and other Poems''.

Oscott also produced writers whose relationship with their Catholic background was ambiguous or actively hostile, and who – often writing from exile – were to become leading figures of the

Oscott also produced writers whose relationship with their Catholic background was ambiguous or actively hostile, and who – often writing from exile – were to become leading figures of the decadent literature

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in social norm, standards, morality, morals, dignity, religion, religious faith, honor, discipline, or competen ...

of the close of the 19th century. The Irish-born George Moore was provoked into becoming a writer by his seven years at Oscott, which he called "a vile hole, a den of priests", turning to Byron and Shelley and noting that "it pleased me to read 'Queen Mab' and 'Cain' amid the priests and ignorance of a hateful Roman Catholic college". His early novels – particularly his 1885 work ''A Mummer's Wife'', which dealt with alcoholism and the seedy underside of theatrical life – "opened up new possibilities for the novel in English", being the first to break away from the literary conventions of the Victorian style under the influence of the naturalism of Émile Zola. Moore constantly developed the form of his literary self-expression, with his later novels having a more fragmented, tapestry-like structure. He was a pivotal figure in the transition from Victorian to modern fiction, and a particular influence on James Joyce: the critic Graham Hough wrote that "neither the title nor the content of Joyce's '' Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man'' would have been quite the same in 1916 if it had not been for the prior existence of George Moore's ''Confessions of a Young Man'' in 1886." "The Dead", the final story of Joyce's '' Dubliners'', was directly inspired by Moore's 1891 novel ''Vain Fortune''. The eccentric novelist and artist Frederick Rolfe studied at Oscott from 1887, but left after it was decided he was an unsuitable candidate for the priesthood. Despite his open homosexuality he strongly felt himself to have a vocation for the priesthood throughout his lifetime. His most famous work was the decadent semi-autobiographical wish-fulfilment novel '' Hadrian the Seventh'', published under his self-styled title Baron Corvo, in which he imagined himself as the Pope, but he also wrote short stories, poetry and essays. Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was inspired to become poet by the metaphysical teachings of Oscott's professor of philosophy during the 1850s, but embarked upon a succession of affairs during his subsequent career as a diplomat, becoming a self-confessed hedonist. He is best known for his erotic verse, and for his anti-imperialist opposition to British policy in Ireland, Egypt, Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and India. In 1914 a group of poets including W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

, and Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington (8 July 1892 – 27 July 1962), born Edward Godfree Aldington, was an English writer and poet, and an early associate of the Imagist movement. He was married to the poet Hilda Doolittle (H. D.) from 1911 to 1938. His 50-year w ...

entertained Blunt to a lunch of roast peacock, paying tribute to him as the first poet to relate poetry to real life. Pound wrote of Blunt's "unconquered flame", though Yeats was more ambivalent, confiding in T. Sturge Moore

Thomas Sturge Moore (4 March 1870 – 18 July 1944) was a British poet, author and artist.

Biography

Sturge Moore was born at 3 Wellington Square, Hastings, East Sussex, on 4 March 1870 and educated at Dulwich College, the Croydon School ...

that "only a small part of his work is good but that is exceedingly fine".

19th century poetry and drama

Although writing and, particularly, playwrighting were still not considered respectable activities for women throughout much of the period, 19th century Birmingham featured a notable concentration women poets and dramatists. Constance Naden, who was born in Edgbaston and lived most of her life in Birmingham, published two well-received volumes of poetry in the 1880s while studying science at Mason Science College. She has been celebrated as the foremost female poet to hail from Birmingham.Sarah Anne Curzon

Sarah Anne Curzon née Vincent (1833 – November 6, 1898) was a British-born Canadian poet, journalist, editor, and playwright who was one of "the first women's rights activists and supporters of liberal feminism" in Canada.Kym Bird,Curzon, Sara ...

was born and educated in Birmingham, where she began writing and contributing essays and fiction to periodicals at an early age.

"At any one time there must be five or six supremely intelligent people on the earth," '' The New Yorker'' poetry editor Howard Moss wrote shortly after Auden's death, "Auden was one of them". Auden's family roots were strongly tied to the West Midlands and he grew up from the age of six months in the Birmingham area, first in Solihull and then in Harborne, the son of George Augustus Auden

George Augustus Auden (27 August 1872 – 3 May 1957) was an English physician, professor of public health, school medical officer, and writer on archaeological subjects.

Biography

Auden was born at Horninglow, Burton-upon-Trent, the sixth ...

, the Schools Medical Officer for Birmingham City Council. Auden's early poetry carried strong social, political and economic overtones, reflecting an interest in the thought of Marx and Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts in ...

inherited from his father, but his later work was characterised by a greater interest in religious and spiritual issues. The huge range of form, style and subject exhibited by his work, the variety of its outlook and its accessibility and emotional directness initially provoked scepticism amongst modernist critics who placed greater value on consistency and objectivity, but his reputation grew as modernist orthodoxy waned, and he has since increasingly come to be viewed as the first writer of the postmodern

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by skepticism toward the " grand narratives" of moderni ...

era. By 2011 the American critic Edward Mendelson could write: "at the start of the twenty-first century Auden's stature had reached the point where many readers thought it not implausible to judge his work the greatest body of poetry in English of the previous hundred years or more".

Birmingham remained Auden's principal home for three decades, until he left for the United States in 1939 (he was noted for going shopping for cigarettes in Harborne in his dressing gown) and he identified with the city throughout his lifetime. Birmingham also featured widely in his work. "As I Walked Out One Evening", one of his best-known early poems, moves a ballad constructed from a series of allusions to folksong and popular culture into the decidedly 20th century context of Bristol Street in Birmingham City Centre. In " Letter to Lord Byron" he rejects the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

idyll of William Wordsworth in favour of a decisive if irony-tinged commitment to the contemporary urban landscape of the Midlands, declaring "Clearer the Scafell Pike, my heart has stamped on / The view from Birmingham to Wolverhampton"; before continuing "Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery / That was, and still is, my ideal scenery". The wider influence of the city on Auden's outlook and work was noted in 1945 by the American critic Edmund Wilson who observed that Auden "in fundamental ways ... doesn't belong in that London literary world – he's more vigorous and more advanced. With his Birmingham background ... he is in some ways more like an American. He is really extremely tough – cares nothing about property or money, popularity or social prestige-does everything on his own and alone."

Auden lay at the forefront of the Auden Group

The Auden Group or the Auden Generation is a group of British and Irish writers active in the 1930s that included W. H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood, and sometimes Edward Upward and Rex Warner. ...

that dominated English poetry of the 1930s and also included the Birmingham-born Rex Warner and the Birmingham-based Louis MacNeice

Frederick Louis MacNeice (12 September 1907 – 3 September 1963) was an Irish poet and playwright, and a member of the Auden Group, which also included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis. MacNeice's body of work was widely a ...

, who had moved to the city from Oxford in 1930 to teach Classics at the University of Birmingham. MacNeice's experience of Birmingham's urbanity lay behind the major advances in his poetry in the early 1930s, as his work increasingly reflected the city with the sympathetic detachment that was to become his distinctive poetic voice. His 1935 collection ''Poems'' established him as one of the leading new poets of the time, being described by Cecil Day-Lewis

Cecil Day-Lewis (or Day Lewis; 27 April 1904 – 22 May 1972), often written as C. Day-Lewis, was an Irish-born British poet and Poet Laureate from 1968 until his death in 1972. He also wrote mystery stories under the pseudonym of Nicholas Bla ...

as "in some ways the most interesting of the poetical work produced in the last two years" – a particularly significant comparison for a period that included major publications by T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

, Auden, Stephen Spender and Day-Lewis himself. As well as marking a high point in his poetic practice, MacNeice's period in Birmingham was one of domestic happiness, abruptly shattered in 1934 when his wife left him and his son to move to the United States with an American football player. In response MacNeice "began to go out a great deal and discovered Birmingham. Discovered that the students were human; discovered that Birmingham had its own writers and artists who were free of the London trade-mark." With his mentor E. R. Dodds

Eric Robertson Dodds (26 July 1893 – 8 April 1979) was an Irish classics, classical scholar. He was Regius Professor of Greek (Oxford), Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Oxford from 1936 to 1960.

Early life and education

Dodds wa ...

leaving the city, however, he came to feel increasingly isolated and in 1936 accepted a lectureship at Bedford College, London.

Early 20th century Birmingham also featured several notable poets who were not associated with the Auden circle. John Drinkwater was one of the originators of the Georgian Poetry movement in 1912, and one of only five poets whose work was to feature in all of the ''Georgian Poetry'' anthologies. Later editions of the series also included the work of the Halesowen-born, Birmingham-educated writer Francis Brett Young

Francis Brett Young (29 June 1884 – 28 March 1954) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, composer, doctor and soldier.

Life

Francis Brett Young was born in Halesowen, Worcestershire. He received his early education at Iona, a pri ...

. Charles Madge, later the founder of Mass-Observation

Mass-Observation is a United Kingdom social research project; originally the name of an organisation which ran from 1937 to the mid-1960s, and was revived in 1981 at the University of Sussex.

Mass-Observation originally aimed to record everyday ...

and Professor of Sociology at Birmingham University, was a leading Surrealist poet

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

during the 1930s. His poetry featured regularly in the ''London Bulletin'', and his 1933 article "Surrealism for the English" advocated that English surrealist poets would need to combine knowledge of "the philosophical position of the French surrealists" with "a knowledge of their own language and literature" two or three years before most people in England had even heard of the movement. Henry Treece