Literature of al-Andalus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

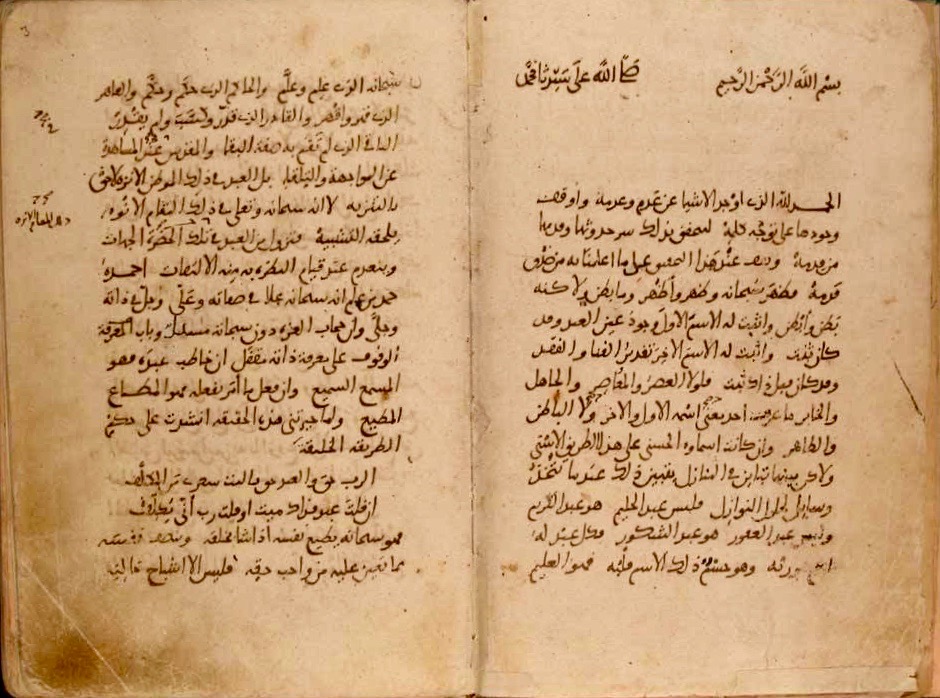

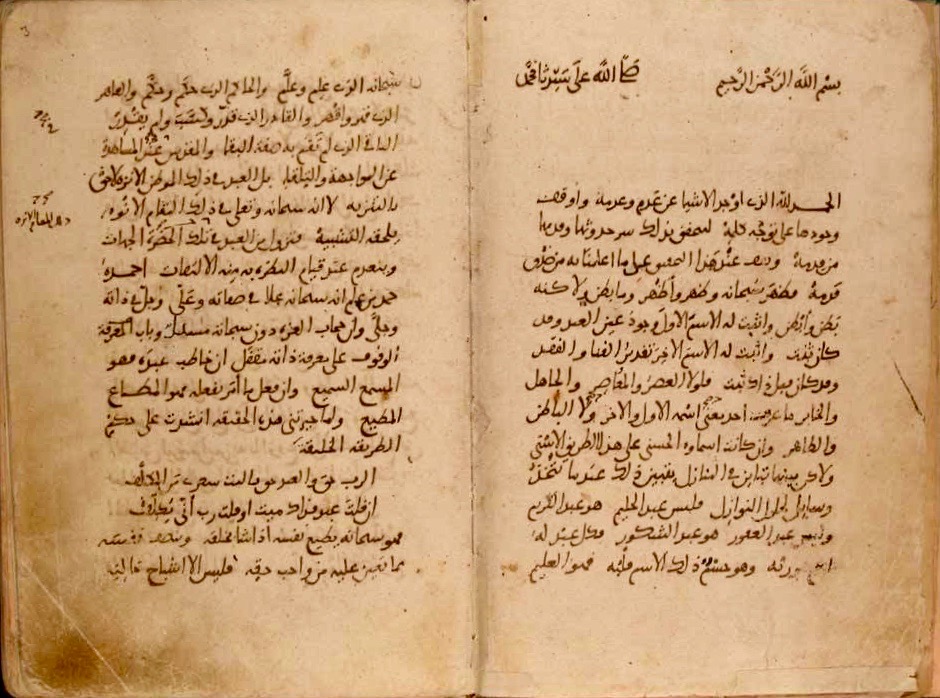

The literature of al-Andalus, also known as Andalusi literature (, ), was produced in

A mind of his own

Writing in math and astronomy flourished in this period with the influence of

Writing in math and astronomy flourished in this period with the influence of

The collapse of the

The collapse of the

When literary figures sensed the decline of Andalusi poetry, they began to gather and anthologize: Ibn Bassam wrote ,

When literary figures sensed the decline of Andalusi poetry, they began to gather and anthologize: Ibn Bassam wrote ,

Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi wrote the ''qasida'' ''Elegy for al-Andalus'' in 1267.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the sciences—such as mathematics, astronomy, pharmacology, botany, and medicine—flourished.

Hadith Bayad wa Riyad is a 13th-century love story and one of 3 surviving illuminated manuscripts from al-Andalus.

Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi wrote the ''qasida'' ''Elegy for al-Andalus'' in 1267.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the sciences—such as mathematics, astronomy, pharmacology, botany, and medicine—flourished.

Hadith Bayad wa Riyad is a 13th-century love story and one of 3 surviving illuminated manuscripts from al-Andalus.

According to Salah Jarrar, the "bulk of [literature in the Nasrid period] dealt and was closely involved with the political life of the state. The conflict between the last Muslim state in Spain and the Spanish states seems to have dominated every aspect of life in Granada."

The polymath and statesman Ibn al-Khatib, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khatīb is regarded as one of the most significant writers of the Nasrid dynasty, Nasrid period, covering subject such as "history, biography, the art of government, politics, geography, poetics, theology, fiqh, Sufism, grammar, medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture, music, and falconry." The last of the poets of al-Andalus before the Granada War, fall of Granada was Ibn Zamrak.

As for prose, which began in al-Andalus with Ibn Shahid and Ibn Hazm, it quickly leaned toward replicating the prose of the Mashreq. ''Siraj al-Muluk'' by Abu Bakr al-Turtushi, as well as the Al-Balawi Encyclopedia and the list of Maqama, ''maqamat'' that replicated those of Al-Hariri of Basra, such as those of Ahmed bin Abd el-Mu'min of Jerez (1222). The Almohads encouraged religious and scientific composition: in the religious sciences, (1426) wrote ''at-Tuhfa'' () and wrote about language. The works of some writers, such as the grammarian

According to Salah Jarrar, the "bulk of [literature in the Nasrid period] dealt and was closely involved with the political life of the state. The conflict between the last Muslim state in Spain and the Spanish states seems to have dominated every aspect of life in Granada."

The polymath and statesman Ibn al-Khatib, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khatīb is regarded as one of the most significant writers of the Nasrid dynasty, Nasrid period, covering subject such as "history, biography, the art of government, politics, geography, poetics, theology, fiqh, Sufism, grammar, medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture, music, and falconry." The last of the poets of al-Andalus before the Granada War, fall of Granada was Ibn Zamrak.

As for prose, which began in al-Andalus with Ibn Shahid and Ibn Hazm, it quickly leaned toward replicating the prose of the Mashreq. ''Siraj al-Muluk'' by Abu Bakr al-Turtushi, as well as the Al-Balawi Encyclopedia and the list of Maqama, ''maqamat'' that replicated those of Al-Hariri of Basra, such as those of Ahmed bin Abd el-Mu'min of Jerez (1222). The Almohads encouraged religious and scientific composition: in the religious sciences, (1426) wrote ''at-Tuhfa'' () and wrote about language. The works of some writers, such as the grammarian

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

, or Islamic Iberia, from the Muslim conquest

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He esta ...

in 711 to either the Catholic conquest of Granada in 1492 or the Expulsion of the Moors ending in 1614. Andalusi literature was written primarily in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, but also in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, Judeo-Arabic

Judeo-Arabic dialects (, ; ; ) are ethnolects formerly spoken by Jews throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Under the ISO 639 international standard for language codes, Judeo-Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage under the code jrb, encomp ...

, Aljamiado

''Aljamiado'' (; ; ar, عَجَمِيَة trans. ''ʿajamiyah'' ) or ''Aljamía'' texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Aragonese, Portuguese, Sp ...

, and Mozarabic

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

.

Abdellah Hilaat's World Literature Encyclopedia divides the history of Al-Andalus into two period

s: the period of expansion, starting with the conquest of Hispania

The Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula was a process by which the Roman Republic seized territories in the Iberian Peninsula that were previously under the control of native Celtic, Iberian, Celtiberian and Aquitanian tribes and the Car ...

up to the first Taifa period, and the period of recession in which Al-Andalus was ruled by two major African empires: the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

and the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

.

Conquest

Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is '' Adab'', which is derived from ...

in al-Andalus began with the Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, also known as the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, was the initial expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate over Hispania (in the Iberian Peninsula) from 711 to 718. The conquest resulted in the decline of t ...

starting in the year 711. The 20th century Moroccan scholar of literature Abdellah Guennoun cites the Friday sermon

In Islam, Friday prayer or Congregational prayer ( ar, صَلَاة ٱلْجُمُعَة, ') is a prayer ('' ṣalāt'') that Muslims hold every Friday, after noon instead of the Zuhr prayer. Muslims ordinarily pray five times each day accordin ...

of the Amazigh

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

general Tariq ibn Ziyad

Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād ( ar, طارق بن زياد), also known simply as Tarik in English, was a Berber commander who served the Umayyad Caliphate and initiated the Muslim Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Hispania (present-day Spain and Portugal) ...

to his soldiers upon landing in Iberia as a first example.

The literature of the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

conquerors of Iberia, aside from the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

, was limited to eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

strophic

Strophic form – also called verse-repeating form, chorus form, AAA song form, or one-part song form – is a song structure in which all verses or stanzas of the text are sung to the same music. Contrasting song forms include through-composed, ...

poetry that was popular in the early 7th century. The content of the conquerors' poetry was often boasting

Boasting or bragging is speaking with excessive pride and self-satisfaction about one's achievements, possessions, or abilities.

Boasting occurs when someone feels a sense of satisfaction or when someone feels that whatever occurred proves thei ...

about noble heritage, celebrating courage in war, expressing nostalgia for homeland, or elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

for those lost in battle, though all that remains from this period is mentions and descriptions.

In contrast with the circumstances in the Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

invasion of Iberia, the Arabic that came with the Muslim invasion had the status of "a vehicle for a higher culture, a literate and literary civilization." From the eighth to the thirteenth century, the non-Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

forms of intellectual expression were dominant in the area.

Umayyad period (756–1031)

In his ''History of Arabic Literature'',Hanna Al-Fakhoury Hanna-l-Fakhoury ( ar, حنا الفاخوري, Ḥānna Al-Faḫūry 1914 – October 4, 2011) was a Lebanese Melkite priest, member of the Missionaries of St. Paul Society, philosopher and linguist. He was born in Zahlé, Lebanon, where his ...

cites two main factors as shaping Andalusi society in the early Umayyad period: the mixing of the Arabs with other peoples and the desire to replicate the Mashriq

The Mashriq ( ar, ٱلْمَشْرِق), sometimes spelled Mashreq or Mashrek, is a term used by Arabs to refer to the eastern part of the Arab world, located in Western Asia and eastern North Africa. Poetically the "Place of Sunrise", the n ...

. The bustling economy of al-Andalus allowed Al-Hakam I

Abu al-As al-Hakam ibn Hisham ibn Abd al-Rahman () was Umayyad Emir of Cordoba from 796 until 822 in Al-Andalus (Moorish Iberia).

Biography

Al-Hakam was the second son of his father, his older brother having died at an early age. When he came ...

to invest in education and literacy; he built 27 madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s in Cordoba and sent missions to the east to procure books to be brought back to his library. Al-Fakhoury cites Reinhart Dozy

Reinhart Pieter Anne Dozy (Leiden, Netherlands, 21 February 1820 – Leiden, 29 April 1883) was a Dutch scholar of French (Huguenot) origin, who was born in Leiden. He was an Orientalist scholar of Arabic language, history and literature.

Biogra ...

in his 1881 : "Almost all of Muslim Spain could read and write, while the upper class of Christian Europe could not, with the exception of the clergy." Cities—such as Córdoba, Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

, and Toledo—were the most important centers of knowledge in al-Andalus.

On religion

The east was determined to spreadIslam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and protect it in distant Iberia, sending religious scholars, or ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

a''. Religious study grew and spread, and the Iberian Umayyads, for political reasons, adopted the Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

school of jurisprudence, named after the Imam Malik ibn Anas

Malik ibn Anas ( ar, مَالِك بن أَنَس, 711–795 CE / 93–179 AH), whose full name is Mālik bin Anas bin Mālik bin Abī ʿĀmir bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith bin Ghaymān bin Khuthayn bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith al-Aṣbaḥī ...

and promoted by Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i

Abū ʿAmr ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAmr al-ʾAwzāʿī ( ar, أبو عمرو عبدُ الرحمٰن بن عمرو الأوزاعي) (707–774) was an Islamic scholar, traditionalist and the chief representative and eponym of the ʾAwzāʿī ...

. A religious school was established, which published Malik's ''Muwatta''.

This school produced a number of notable scholars, prominent among whom was Ibn 'Abd al-Barr

Yūsuf ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Barr, Abū ʿUmar al-Namarī al-Andalusī al-Qurṭubī al-Mālikī, commonly known as Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr ( ar, ابن عبد البر)

. Al-Andalus witnessed great deliberation in Quranic exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (logic), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern usage, ...

, or ''tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

'', from competing schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, or ''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

''. Upon his return from the east, (817-889) unsuccessfully attempted to introduce the Shafi‘i

The Shafii ( ar, شَافِعِي, translit=Shāfiʿī, also spelled Shafei) school, also known as Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī, is one of the four major traditional schools of religious law (madhhab) in the Sunnī branch of Islam. It was founded by ...

school of ''fiqh'', though Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

(994-1064) considered Makhlad's exegesis favorable to ''Tafsir al-Tabari

''Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān'' (, also written with ''fī'' in place of ''ʿan''), popularly ''Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī'' ( ar, تفسير الطبري), is a Sunni ''tafsir'' by the Persian scholar Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (8 ...

''. The Zahiri

The Ẓāhirī ( ar, ظاهري, otherwise transliterated as ''Dhāhirī'') ''madhhab'' or al-Ẓāhirīyyah ( ar, الظاهرية) is a Sunnī school of Islamic jurisprudence founded by Dāwūd al-Ẓāhirī in the 9th century CE. It is chara ...

school was, however, introduced by Ibn Qasim al-Qaysi, and further supported by Mundhir ibn Sa'īd al-Ballūṭī. It was also heralded by Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

, a polymath at the forefront of all kinds of literary production in the 11th century, widely acknowledged as the father of comparative religious studies,Joseph A. KechichianA mind of his own

Gulf News

''Gulf News'' is a daily English language newspaper published from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It was first launched in 1978, and is currently distributed throughout the UAE and also in other Persian Gulf Countries. Its online edition was launch ...

: 21:30 December 20, 2012. and who wrote (''The Separator Concerning Religions, Heresies, and Sects'').

The Muʿtazila school and philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

also developed in al-Andalus, as attested to in the book of Ibn Mura (931).

On language

The study of language spread and was invigorated by the migration of the linguist (967), who migrated fromBaghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

to Cordoba and wrote a two-volume work entitled based on his teachings at the Mosque of Córdoba. He also authored a 5000-page compendium on language and ''an-Nawādir''. Some of his contemporaries were (968), (992), and Ibn al-Qūṭiyya

Ibn al-Qūṭiyya (, died 6 November 977), born Muḥammad Ibn ʿUmar Ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn ʾIbrāhīm ibn ʿIsā ibn Muzāḥim (), also known as Abu Bakr or al-Qurtubi ("the Córdoban"), was an Andalusian historian and the greatest philologi ...

(977). Ibn Sidah

Abū’l-Ḥasan ʻAlī ibn Ismāʻīl (), known as Ibn Sīdah (), or Ibn Sīdah'l-Mursī (), (c.1007-1066), was a linguist, philologist and lexicographer of Classical Arabic from Andalusia. He compiled the encyclopedia ' ()(Book of Customs) and ...

(1066) wrote and .

On history

At first, Andalusi writers mixed history with legend, as did. The so-called "Syrian chronicle", a history of events in the latter half of the 8th century, probably written around 800, is the earliestArabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

history of al-Andalus. It is known today, however, only as the larger part of the 11th-century ''Akhbār majmūʿa

The ''Akhbār majmūʿa fī fatḥ al-Andalus'' ("Collection of Anecdotes on the Conquest of al-Andalus") is an anonymous history of al-Andalus compiled in the second decade of the 11th century and only preserved in a single manuscript, now in the ...

''. The author of the Syrian chronicle is unknown, but may have been Abu Ghalib Tammam ibn Alkama Abū Ghālib Tammām ibn ʿAlḳama al-Thaḳafī, also transliterated Ibn ʿAlqama al-Thaqafī (720×728 – 811), was an Arab military leader in al-Andalus during the establishment of the ʿUmayyad Emirate of Córdoba.

Ibn ʿAlḳa ...

, who came to al-Andalus with the Syrian army

" (''Guardians of the Homeland'')

, colors = * Service uniform: Khaki, Olive

* Combat uniform: Green, Black, Khaki

, anniversaries = August 1st

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles = 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Six ...

in 741.. Tammam's descendant, Tammam ibn Alkama al-Wazir Tammām ibn ʿĀmir ibn Aḥmad ibn Ghālib ibn Tammām ibn ʿAlḳama al-Thaḳafī al-Wazīr (803/810–896) was an Arab high official and poet in the Emirate of Córdoba. He made an important historiographical contribution to the literature of al ...

(d. 896), wrote poetry, including a lost '' urjūza'' on the history of al-Andalus.

They later wrote annals in the format of Al-Tabari's text '' History of the Prophets and Kings'', which (980) complemented with contemporary annals. Most historians were interested in the history of Hispania, tracing the chronology of its history by kings and princes. Encyclopedias of people also became popular, such as encyclopedias of judges, doctors, and writers. The most important of these was told the history of al-Andalus from the Islamic conquest to the time of the author, as seen in the work of the Umayyad court historian and genealogist Ahmed ar-Razi (955) ''News of the Kings of al-Andalus'' () and that of his son Isa, who continued his father's work and whom Ibn al-Qūṭiyya

Ibn al-Qūṭiyya (, died 6 November 977), born Muḥammad Ibn ʿUmar Ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn ʾIbrāhīm ibn ʿIsā ibn Muzāḥim (), also known as Abu Bakr or al-Qurtubi ("the Córdoban"), was an Andalusian historian and the greatest philologi ...

cited. ar-Razi was also cited by Ibn Hayyan

Abū Marwān Ḥayyān ibn Khalaf ibn Ḥusayn ibn Ḥayyān al-Qurṭubī () (987–1075), usually known as Ibn Hayyan, was a Muslim historian from Al-Andalus.

Born at Córdoba, his father was an important official at the court of the Andalusi ...

in . The most important historical work of this period was Said al-Andalusi's ''Tabaqat ul-Umam'', which chronicled the history of the Greeks and the Romans as well.

On geography

Among the prominent writers in geography—besidesAḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Mūsa al-Rāzī Aḥmad al-Rāzī (April 888 – 1 November 955), full name Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Rāzī al-Kinānī, was a Muslim historian of Persian origin who wrote the first narrative history of Islamic rule in Spain. Later Muslim hi ...

, who described al-Andalus with great skill—there was Abū ʿUbayd al-Bakri (1094).

On math and astronomy

Writing in math and astronomy flourished in this period with the influence of

Writing in math and astronomy flourished in this period with the influence of Maslama al-Majriti

Abu al-Qasim Maslama ibn Ahmad al-Majriti ( ar, أبو القاسم مسلمة بن أحمد المجريطي: c. 950–1007), known or Latin as , was an Arab Muslim astronomer, chemist, mathematician, economist and Scholar in Islamic Spain, ac ...

(1007), who developed the work of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

and al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astronom ...

. Ibn al-Saffar

Abu al‐Qasim Ahmad ibn Abd Allah ibn Umar al‐Ghafiqī ibn as-Saffar al‐Andalusi (born in Córdoba, Spain, Cordoba, died in the year 1035 at Denia), also known as Ibn as-Saffar (, literally: son of the brass worker), was a Spanish-Arab astrono ...

wrote about the astrolabe and influenced European science into the 15th century. Ibn al-Samh

Abū al‐Qāsim Aṣbagh ibn Muḥammad ibn al‐Samḥ al‐Gharnāṭī al-Mahri () (born 979, Córdoba; died 1035, Granada), also known as Ibn al‐Samḥ, was an Arab mathematician and astronomer from Al-Andalus. He worked at the school foun ...

was a mathematician who also wrote about astrolabes.

On medicine and agriculture

Works in medicine and agriculture also flourished underAbd al-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 92 ...

. Among writers in these topics there were Al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

(1013).

Ibn al-Kattani, also known as al-Mutatabbib, wrote about medicine, philosophy, and logic.

Literature

The collection '' Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' byIbn Abd Rabbih

Ibn ʿAbd Rabbih () or Ibn ʿAbd Rabbihi (Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn `Abd Rabbih) (860–940) was an arab writer and poet widely known as the author of '' Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' (''The Unique Necklace'').

Biography

He was born in Cordova, now in Spain ...

(940) could be considered the first Andalusi literary work, though its contents relate to the Mashriq

The Mashriq ( ar, ٱلْمَشْرِق), sometimes spelled Mashreq or Mashrek, is a term used by Arabs to refer to the eastern part of the Arab world, located in Western Asia and eastern North Africa. Poetically the "Place of Sunrise", the n ...

.

Muhammad ibn Hani al-Andalusi al-Azdi, a North African poet, studied in al-Andalus.

The poet al-Ghazal of Jaén served as a diplomat in 840 and 845. His poetry is quoted extensively by Ibn Dihya

Umar bin al-Hasan bin Ali bin Muhammad bin al-Jamil bin Farah bin Khalaf bin Qumis bin Mazlal bin Malal bin Badr bin Dihyah bin Farwah, better known as Ibn Dihya al-Kalbi ( ar, ابن دحية الكلبي) was a Moorish scholar of both the Ara ...

.

Muwashshah

From around the 9th century, the Arab and Hispanic elements of al-Andalus began to coalesce, giving birth to a new Arab literature, evident in the new poetic form: the ''muwashshah

''Muwashshah'' ( ar, موشح ' literally means "girdled" in Classical Arabic; plural ' or ' ) is the name for both an Arabic poetic form and a secular musical genre. The poetic form consists of a multi-lined strophic verse poem written ...

''.

In the beginning, ''muwashshah'' represented a variety of poetic meters and schemes, ending with a verse in Ibero-Romance

The Iberian Romance, Ibero-Romance or sometimes Iberian languagesIberian languages is also used as a more inclusive term for all languages spoken on the Iberian Peninsula, which in antiquity included the non-Indo-European Iberian language. are a ...

. It marked the first instance of language mixing in Arab poetry as well as the syncretism of Arab and Hispanic cultures. The ''muwashshah'' remained sung in Standard Arabic although its scheme and meter changed and the Ibero-Romance ending was added. Some famous examples include "'' Lamma Bada Yatathanna''" and "". In spite of its widespread popularity and its favorability among Mashreqi critics, the ''muwashshah'' remained a form inferior to classical Arabic forms that varied only minimally in the courts of the Islamic west, due to the folksy nature of the ''muwashshah''.

The muwashshah would typically end with a closing stanza, or a ''kharja

A kharja or kharjah ( ar, خرجة tr. ''kharjah'' , meaning "final"; es, jarcha ; pt, carja ; also known as markaz), is the final refrain of a ''muwashshah'', a lyric genre of Al-Andalus (the Islamic Iberian Peninsula) written in Arabic or M ...

'', in a Romance language or Arabic vernacular—except in praise poems, in which the closing stanza would also be in Standard Arabic.

The ''muwashshah'' has gained importance recently among Orientalists because of its connection to early Spanish and European folk poetry and the troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a ''trobairit ...

tradition.

Eastern influence

Andalusi literature was heavily influenced by Eastern styles, with court literature often replicating eastern forms. UnderAbd al-Rahman II

Abd ar-Rahman II () (792–852) was the fourth ''Umayyad'' Emir of Córdoba in al-Andalus from 822 until his death. A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.

Abd ar-Rahman was born in Toledo, the ...

, came Ziryab

Abu l-Hasan 'Ali Ibn Nafi, better known as Ziryab, Zeryab, or Zaryab ( 789– 857) ( ar, أبو الحسن علي ابن نافع, زریاب, rtl=yes) ( fa, زَریاب ''Zaryāb''), was a singer, oud and lute player, composer, poet, and teach ...

(857)—the mythic poet, artist, musician and teacher—from the Abbasid Empire

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in the East. He gave Andalusi society Baghdadi influence.

The ''qiyān'' were a social class of non-free women trained as entertainers. The ''qiyān'' brought from the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

East were conduits of art, literature, and culture.

Among the Mashreqi poets most influential in the Maghreb was Al-Mutanabbi

Abū al-Ṭayyib Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Mutanabbī al-Kindī ( ar, أبو الطيب أحمد بن الحسين المتنبّي الكندي; – 23 September 965 AD) from Kufa, Abbasid Caliphate, was a famous Abbasid-era Arab poet at th ...

(965), whose poetry was commented on by , , and Ibn Sidah

Abū’l-Ḥasan ʻAlī ibn Ismāʻīl (), known as Ibn Sīdah (), or Ibn Sīdah'l-Mursī (), (c.1007-1066), was a linguist, philologist and lexicographer of Classical Arabic from Andalusia. He compiled the encyclopedia ' ()(Book of Customs) and ...

. The court poets of Cordoba followed his footsteps in varying and mastering their craft. The ''maqamas'' of the Persian poet Badi' al-Zaman al-Hamadani were also embraced in al-Andalus, and influenced Ibn Malik

Abu 'Abd Allah Jamal al-Din Muḥammad ibn Abd Allāh ibn Malik al-Ta'i al-Jayyani ( ar, ابو عبدالله جمال الدين محمد بن عبدالله بن محمد بن عبدالله بن مالك الطائي الجياني النحو ...

, Ibn Sharaf Ibn Sharaf al-Qayrawānī (; Anno Domini, AD 1000–1067 nno Hegirae, AH 390–460 was an Arabs, Arab Muslim writer and court poet who served first the Zīrids in Ifrīqiya (Africa) and later various sovereigns in al-Andalus (Spain). He wrote in ...

, and . The ''maqama'' known as '' al-Maqama al-Qurtubiya'', attributed to Al-Fath ibn Khaqan

Al-Fatḥ ibn Khāqān () ( – 11 December 861) was an Abbasid official and one of the most prominent figures of the court of the Caliph al-Mutawakkil (). The son of a Turkic general of Caliph al-Mu'tasim, al-Fath was raised at the caliphal ...

, is notable as it is a poem of invective

Invective (from Middle English ''invectif'', or Old French and Late Latin ''invectus'') is abusive, reproachful, or venomous language used to express blame or censure; or, a form of rude expression or discourse intended to offend or hurt; vituperat ...

satirizing . According to Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila, the use of the ''maqama'' form for invective appears to be an Andalusi innovation.

Court poetry followed tradition until the 11th century, when it took a bold new form: the Umayyad caliphs sponsored literature and worked to gather texts, as evidenced in the library of Al-Hakam II

Al-Hakam II, also known as Abū al-ʿĀṣ al-Mustanṣir bi-Llāh al-Hakam b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (; January 13, 915 – October 16, 976), was the Caliph of Córdoba. He was the second ''Umayyad'' Caliph of Córdoba in Al-Andalus, and son of Ab ...

. As a result, a new school of court poets appeared, most important of whom was (982). However, urban Andalusi poetry started with Ibn Darraj al-Qastalli (1030), under Caliph al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) w ...

, who burned the library of Al-Hakam fearing that science and philosophy were a threat to religion. and were among the most prominent of this style and period.

led a movement of poets of the aristocracy opposed to the folksy ''muwashshah'' and fanatical about eloquent poetry and orthodox Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

. He outlined his ideas in his book ''at-Tawabi' waz-Zawabi (), a fictional story about a journey through the world of the Jinn

Jinn ( ar, , ') – also Romanization of Arabic, romanized as djinn or Anglicization, anglicized as genies (with the broader meaning of spirit or demon, depending on sources)

– are Invisibility, invisible creatures in early Arabian mytho ...

. Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

, in his analysis of in ''The Ring of the Dove

''The Ring of the Dove'' or ''Ṭawq al-Ḥamāmah'' ( ar, طوق الحمامة)Hitti, p. 58 is a treatise on love written in the year 1022 by Ibn Hazm. Normally a writer of theology and law, Ibn Hazm produced his only work of literature with ' ...

'', is considered a member of this school, though his poetry is of a lower grade.

Judeo-Andalusi literature

Jewish writers in al-Andalus were sponsored by courtiers such asHasdai ibn Shaprut

Hasdai (Abu Yusuf ben Yitzhak ben Ezra) ibn Shaprut ( he, חסדאי אבן שפרוט; ar, حسداي بن شبروط, Abu Yussuf ibn Shaprut) born about 915 at Jaén, Spain; died about 970 at Córdoba, Andalusia, was a Jewish scholar, ph ...

(905-975) Samuel ibn Naghrillah (993-1056). Jonah ibn Janah

Jonah ibn Janah or ibn Janach, born Abu al-Walīd Marwān ibn Janāḥ ( ar, أبو الوليد مروان بن جناح, or Marwan ibn Ganaḥ Hebrew: ), (), was a Jewish rabbi, physician and Hebrew grammarian active in Al-Andalus, or Islamic ...

(990-1055) wrote a book of Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

.

Samuel ibn Naghrillah, Joseph ibn Naghrela

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, and Ibn Sahl al-Isra'ili wrote poetry in Arabic, but most Jewish writers in al-Andalus—while incorporating elements such as rhyme, meter, and themes of classical Arabic poetry—created poetry in Hebrew. In addition to a highly regarded corpus of religious poetry, poets such as Dunash ben Labrat, Moses ibn Ezra

Rabbi Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra, known as Ha-Sallaḥ ("writer of penitential prayers") ( ar, أَبُو هَارُون مُوسَى بِن يَعْقُوب اِبْن عَزْرَا, ''Abu Harun Musa bin Ya'qub ibn 'Azra'', he, מֹשֶׁה ב ...

, and Solomon ibn Gabirol

Solomon ibn Gabirol or Solomon ben Judah ( he, ר׳ שְׁלֹמֹה בֶּן יְהוּדָה אִבְּן גָּבִּירוֹל, Shlomo Ben Yehuda ibn Gabirol, ; ar, أبو أيوب سليمان بن يحيى بن جبيرول, ’Abū ’Ayy ...

wrote about praise poetry about their Jewish patrons, as well and on topics traditionally considered non-Jewish, such as "carousing, nature, and love" as well as poems with "homoerotic themes.''''

Qasmuna Bint Ismā'īl was mentioned in Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari

Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Maqqarī al-Tilmisānī (or al-Maḳḳarī) (), (1577-1632) was an Algerian scholar, biographer and historian who is best known for his , a compendium of the history of Al-Andalus which provided a basis for the scholar ...

's as well as Al-Suyuti's 15th century anthology of female poets.

Bahya ibn Paquda wrote ''Duties of the Heart'' in Judeo-Arabic

Judeo-Arabic dialects (, ; ; ) are ethnolects formerly spoken by Jews throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Under the ISO 639 international standard for language codes, Judeo-Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage under the code jrb, encomp ...

in Hebrew script

The Hebrew alphabet ( he, אָלֶף־בֵּית עִבְרִי, ), known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish ...

around 1080, and Judah ha-Levi wrote the ''Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion'' in Arabic around 1140.''''

Petrus Alphonsi

Petrus Alphonsi (died after 1116) was a Jewish Spanish physician, writer, astronomer and polemicist who converted to Christianity in 1106. He is also known just as Alphonsi, and as Peter Alfonsi or Peter Alphonso, and was born Moses Sephardi. ...

was an Andalusi Jew who converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

under Alfonso I of Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

in the year 1106. He wrote '' Dialogi contra Iudaeos'', an imaginary conversation between a Christian and a Jew, and '' Disciplina Clericalis'', a collection of Eastern sayings and fables in a frame-tale format present in Arabic literature such as '' Kalīla wa-Dimna.'' He also translated Al-Khawarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astrono ...

's tables and advocated for Arabic sciences, serving as a bridge between cultures at a time when Christian Europe was opening up to "Arabic philosophical, scientific, medical, astronomical, and literary cultures."

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

(1135-1204), who fled al-Andalus in the Almohad period, addressed his ''Guide for the Perplexed'' to Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta

Joseph ben Judah ( he, יוסף בן יהודה ''Yosef ben Yehuda'') of Ceuta ( 1160–1226) was a Jewish physician and poet, and disciple of Moses Maimonides. Maimonides wrote his work, the ''Guide for the Perplexed'' for Joseph.

Life

For th ...

.

Joseph ben Judah ibn Aknin

Joseph ben Judah ibn Aknin ( ar, يوسف ابن عقنين, he, יוסף בן יהודה אבן עקנין; 1150 – c. 1220) was a Sephardic Jewish writer of numerous treatises, mostly on the ''Mishnah'' and the Talmud. He was born in Barcelon ...

(c. 1150 – c. 1220) was polymath and prolific writer born in Barcelona and moved to North Africa under the Almohads, settling in Fes.

''Piyyut

A ''piyyut'' or ''piyut'' (plural piyyutim or piyutim, he, פִּיּוּטִים / פיוטים, פִּיּוּט / פיוט ; from Greek ποιητής ''poiētḗs'' "poet") is a Jewish liturgical poem, usually designated to be sung, ch ...

'' was a form of poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

performed musically with Arabic scales and meters.

First Taifa period (1031–1086)

The collapse of the

The collapse of the caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

and the beginning of the Taifa period, did not have a negative impact on poetic production. In fact, poetry in al-Andalus reached its apex at this time. Ibn Zaydun

Abū al-Walīd Aḥmad Ibn Zaydūni al-Makhzūmī () (1003–1071) or simply known as Ibn Zaydun () or Abenzaidun was an Arab Andalusian poet of Cordoba and Seville. He was considered the greatest neoclassical poet of al-Andalus.

He reinvigorate ...

of Cordoba, author of the , was famously in love with Wallada bint al-Mustakfi

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi ( ar, ولادة بنت المستكفي) (born in Córdoba in 994 or 1010 – died March 26, 1091) was an Andalusian poet.

Early life

Wallada was the daughter of Muhammad III of Córdoba, one of the last Umayyad Co ...

, who inspired the poets of al-Andalus as well as those of the Emirate of Sicily

The Emirate of Sicily ( ar, إِمَارَة صِقِلِّيَة, ʾImārat Ṣiqilliya) was an Islamic kingdom that ruled the island of Sicily from 831 to 1091. Its capital was Palermo (Arabic: ''Balarm''), which during this period became a ...

, such as Ibn Hamdis

Ibn Ḥamdīs al-ʾAzdī al-Ṣīqillī () ( 1056 – c. 1133) was a Sicilian Arab poet.

Ibn Hamdis was born in Syracuse, south eastern Sicily, around 447 AH (1056 AD). Little is known of his youth, which can be reconstructed only through a l ...

. Ibn Sharaf Ibn Sharaf al-Qayrawānī (; Anno Domini, AD 1000–1067 nno Hegirae, AH 390–460 was an Arabs, Arab Muslim writer and court poet who served first the Zīrids in Ifrīqiya (Africa) and later various sovereigns in al-Andalus (Spain). He wrote in ...

of Qairawan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by th ...

and Ibn Hamdün (1139) became famous in the court of of Almería

Almería (, , ) is a city and municipality of Spain, located in Andalusia. It is the capital of the province of the same name. It lies on southeastern Iberia on the Mediterranean Sea. Caliph Abd al-Rahman III founded the city in 955. The city gr ...

, while Abū Isḥāq al-Ilbirī and Abd al-Majid ibn Abdun stood out in Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

.

Abu al-Hakam al-Kirmani was a doctor, mathematician, and philosopher from Cordoba; he is also credited with first bringing ''Brethren of Purity'' to al-Andalus.

Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, poet king of the Abbadid

The Abbadid dynasty or Abbadids ( ar, بنو عباد, Banū ʿAbbādi) was an Arab Muslim dynasty which arose in al-Andalus on the downfall of the Caliphate of Cordoba (756–1031). After the collapse, there were multiple small Muslim states ca ...

Taifa of Seville

The Taifa of Seville ( ''Ta'ifat-u Ishbiliyyah'') was an Arab kingdom which was ruled by the Abbadid dynasty. It was established in 1023 and lasted until 1091, in what is today southern Spain and Portugal. It gained independence from the Caliph ...

, was known as a generous sponsor of the arts. Ibn Hamdis

Ibn Ḥamdīs al-ʾAzdī al-Ṣīqillī () ( 1056 – c. 1133) was a Sicilian Arab poet.

Ibn Hamdis was born in Syracuse, south eastern Sicily, around 447 AH (1056 AD). Little is known of his youth, which can be reconstructed only through a l ...

of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

joined al-Mu'tamid's court.

Almoravid period (1086–1150)

Literature flourished in the Almoravid period. The political unification of Morocco andal-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

under the Almoravid dynasty rapidly accelerated the cultural interchange between the two continents, beginning when Yusuf Bin Tashfiin sent Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, al-Mu'tamid Bin Abbad into exile in Tangier and ultimately Aghmat.

In the Almoravid period two writers stand out: the religious scholar and judge Ayyad ben Moussa and the polymath Ibn Bajja (Avempace). Ayyad is known for having authored Ash-Shifa bi ta'rif huquq al-mustafa, ''Kitāb al-Shifāʾ bīTaʾrif Ḥuqūq al-Muṣṭafá''.

Scholars and theologians such as Ibn Barrajan were summoned to the Almoravid capital in Marrakesh where they underwent tests.

Poetry

Ibn Zaydun, al-Mu'tamid, and Muhammad ibn Ammar were among the more innovative poets of al-Andalus, breaking away from traditional Eastern styles. Themuwashshah

''Muwashshah'' ( ar, موشح ' literally means "girdled" in Classical Arabic; plural ' or ' ) is the name for both an Arabic poetic form and a secular musical genre. The poetic form consists of a multi-lined strophic verse poem written ...

was an important form of poetry and music in the Almoravid period. Great poets from the period are mentioned in anthologies such as , ''Rawd al-Qirtas, Al Mutrib,'' and ''Mu'jam as-Sifr''.

In the Almoravid dynasty, Almoravid period, in which the fragmented ''taifas'' were united, poetry faded as they were mostly interested in religion. Only in Taifa of Valencia, Valencia could free poetry of the sort that spread in the Taifa period be found, while the rulers in other areas imposed traditional Panegyric, praise poetry on their subjects. In Valencia, there was poetry of Nature writing, nature and ''ghazal'' by Ibn Khafaja and poetry of nature and wine by Ibn al-Zaqqaq, Ibn az-Zaqqaq.

History

The historians Ibn Alqama,Ibn Hayyan

Abū Marwān Ḥayyān ibn Khalaf ibn Ḥusayn ibn Ḥayyān al-Qurṭubī () (987–1075), usually known as Ibn Hayyan, was a Muslim historian from Al-Andalus.

Born at Córdoba, his father was an important official at the court of the Andalusi ...

, Al-Bakri, Ibn Bassam, and Al-Fath ibn Khaqan (al-Andalus), al-Fath ibn Khaqan all lived in the Almoravid period.

Almohad period (1150–1230)

The Almohads worked to suppress the influence ofMaliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

—''even publicly burning copies of ''Muwatta Imam Malik'' and Maliki commentaries. They sought to disseminate the doctrine of Ibn Tumart, author of ''E'az Ma Yutlab'' ( ''The Most Noble Calling''), ''Muhadhi al-Muwatta'Almohad reforms

Moroccan literature, Literary production continued despite the devastating effect the Almohad reforms had on cultural life in their domain. Almohad universities continued the knowledge of preceding Andalusi scholars as well as ancient Greco-Roman writers; contemporary literary figures included Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya, Ibn Tufail, Ibn Zuhr, Ibn al-Abbar, Ibn Amira and many more poets, philosophers, and scholars. The abolishment of the ''dhimmi'' status further stifled the once flourishing Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain, Jewish Andalusi cultural scene;Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

went east and many Jews moved to Castillian-controlled Toledo.

In the Almohad Caliphate, Almohad period, the poets Ibn Sahl of Seville and (1177) appeared.

Ibn Tufail and Averroes, Ibn Rushd (Averroes) were considered the main philosophers of the Almohad Caliphate and were patronized by the court. Ibn Tufail wrote the philosophical novel ''Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'', which would later influence ''Robinson Crusoe''. Averroes, Ibn Rushd wrote his landmark work ''The Incoherence of the Incoherence'' responding directly to Al-Ghazali, Al-Ghazali's work ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers''.

Sufism

With the continents united under empire, the development and institutionalization of Sufism was a bi-continental phenomenon taking place on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar. Abu Madyan, described as "the most influential figure of the developmental period of North African Sufism," lived in theAlmohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

period. Ibn Arabi, venerated by many Sufis as ''ash-Sheikh al-Akbar'', was born in Murcia and studied in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

. His works, such as the ''Meccan Revelations'', were highly influential. Ibn Saʿāda, also a native of Murcia, was an influential Hadith studies, traditionist who studied in the East. He wrote a Sufi treatise, ''Tree of the Imagination by Which One Ascends to the Path of Intellection'', in Murcia.

When literary figures sensed the decline of Andalusi poetry, they began to gather and anthologize: Ibn Bassam wrote ,

When literary figures sensed the decline of Andalusi poetry, they began to gather and anthologize: Ibn Bassam wrote , Al-Fath ibn Khaqan

Al-Fatḥ ibn Khāqān () ( – 11 December 861) was an Abbasid official and one of the most prominent figures of the court of the Caliph al-Mutawakkil (). The son of a Turkic general of Caliph al-Mu'tasim, al-Fath was raised at the caliphal ...

wrote " ''Qalā'id al-'Iqyān''" (), Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi wrote ''al-Mughrib fī ḥulā l-Maghrib'' and ''Rayat al-mubarrizin wa-ghayat al-mumayyazin''. Up until the departure of the Muslims from al-Andalus, there were those who carried the standard of the muwashshah, such as Al-Tutili (1126) and Ibn Baqi (1145), as well as those such as Ibn Quzman (1159) who elevated zajal to the highest of artistic heights. The zajal form experienced a rebirth thanks to Ibn Quzman.

Ibn Sab'in was a Sufi scholar from Ricote who wrote the ''Sicilian Questions'' in response to the inquiries of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II of Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily.

Female poets

Hamda bint Ziyad al-Muaddib was a 12th-century poet from Guadix known as the "Al-Khansa of al-Andalus." Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya was a poet from Granada. She later worked for the Almohad caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, educating members of his family.Biography

Biographical books spread after Qadi Ayyad, and among the famous biographers there were Ibn Bashkuwāl, Abu Ja'far Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Dabbi, Ibn al-Abbar, and Ibn Zubayr al-Gharnati. Ṣafwān ibn Idrīs (d. 1202) of Murcia wrote a biographical dictionary of recent poets, ''Zād al-musāfir wa-ghurrat muḥayyā ʾl-adab al-sāfir''.On history

Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi wrote ''Al-Mughrib fī ḥulā l-Maghrib'' citing much of what was published in the field beforehand.On geography and travel writing

Muhammad al-Idrisi stood out in geography and in travel writing: , Ibn Jubayr, and Mohammed al-Abdari al-Hihi.Poetry

Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Kanemi, an Afro-Arab poet from Kanem Empire, Kanem, was active in Seville writing panegyric ''qasida''s for Caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, Yaqub al-Mansur. Although he spent more time in Morocco, it was his stay in Seville that has preserved his name, since he was included in the Andalusi biographical dictionaries.Third Taifa period

Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi wrote the ''qasida'' ''Elegy for al-Andalus'' in 1267.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the sciences—such as mathematics, astronomy, pharmacology, botany, and medicine—flourished.

Hadith Bayad wa Riyad is a 13th-century love story and one of 3 surviving illuminated manuscripts from al-Andalus.

Abu al-Baqa ar-Rundi wrote the ''qasida'' ''Elegy for al-Andalus'' in 1267.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the sciences—such as mathematics, astronomy, pharmacology, botany, and medicine—flourished.

Hadith Bayad wa Riyad is a 13th-century love story and one of 3 surviving illuminated manuscripts from al-Andalus.

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

influenced Spanish language, Spanish and permeated its vernacular forms. New dialects formed with their own folk literature that is studied for its effects on European poetry in the Middle Ages, and for its role in Renaissance literature, Renaissance poetry. Ramon Llull drew extensively from Arabic sciences, and first wrote his Apologetics, apologetic ''Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men'' in Arabic before Catalan language, Catalan and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

.

The agriculturalist Ibn al-'Awwam, active in Seville in the late 12th century, wrote , considered the most comprehensive medieval book in Arabic on agriculture. Ibn Khaldun considered it a revision of Ibn Wahshiyya, Ibn Wahshiyya's ''Nabataean Agriculture''.

Nasrid period (1238–1492)

According to Salah Jarrar, the "bulk of [literature in the Nasrid period] dealt and was closely involved with the political life of the state. The conflict between the last Muslim state in Spain and the Spanish states seems to have dominated every aspect of life in Granada."

The polymath and statesman Ibn al-Khatib, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khatīb is regarded as one of the most significant writers of the Nasrid dynasty, Nasrid period, covering subject such as "history, biography, the art of government, politics, geography, poetics, theology, fiqh, Sufism, grammar, medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture, music, and falconry." The last of the poets of al-Andalus before the Granada War, fall of Granada was Ibn Zamrak.

As for prose, which began in al-Andalus with Ibn Shahid and Ibn Hazm, it quickly leaned toward replicating the prose of the Mashreq. ''Siraj al-Muluk'' by Abu Bakr al-Turtushi, as well as the Al-Balawi Encyclopedia and the list of Maqama, ''maqamat'' that replicated those of Al-Hariri of Basra, such as those of Ahmed bin Abd el-Mu'min of Jerez (1222). The Almohads encouraged religious and scientific composition: in the religious sciences, (1426) wrote ''at-Tuhfa'' () and wrote about language. The works of some writers, such as the grammarian

According to Salah Jarrar, the "bulk of [literature in the Nasrid period] dealt and was closely involved with the political life of the state. The conflict between the last Muslim state in Spain and the Spanish states seems to have dominated every aspect of life in Granada."

The polymath and statesman Ibn al-Khatib, Lisān ad-Dīn Ibn al-Khatīb is regarded as one of the most significant writers of the Nasrid dynasty, Nasrid period, covering subject such as "history, biography, the art of government, politics, geography, poetics, theology, fiqh, Sufism, grammar, medicine, veterinary medicine, agriculture, music, and falconry." The last of the poets of al-Andalus before the Granada War, fall of Granada was Ibn Zamrak.

As for prose, which began in al-Andalus with Ibn Shahid and Ibn Hazm, it quickly leaned toward replicating the prose of the Mashreq. ''Siraj al-Muluk'' by Abu Bakr al-Turtushi, as well as the Al-Balawi Encyclopedia and the list of Maqama, ''maqamat'' that replicated those of Al-Hariri of Basra, such as those of Ahmed bin Abd el-Mu'min of Jerez (1222). The Almohads encouraged religious and scientific composition: in the religious sciences, (1426) wrote ''at-Tuhfa'' () and wrote about language. The works of some writers, such as the grammarian Ibn Malik

Abu 'Abd Allah Jamal al-Din Muḥammad ibn Abd Allāh ibn Malik al-Ta'i al-Jayyani ( ar, ابو عبدالله جمال الدين محمد بن عبدالله بن محمد بن عبدالله بن مالك الطائي الجياني النحو ...

and Abu Hayyan al-Gharnati, reached the Mashreq and had an influence there.

Andalusi literature after Catholic conquest

Suppression

After the Granada War, Fall of Granada, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros oversaw the forced mass conversion of the population in the Spanish Inquisition and the burning of Andalusi manuscripts in Granada. In 1526, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (Charles I of Spain)—issued an edict against "heresy" (e.g. Muslim practices by "New Christians"), including the use of Arabic. The Moriscos managed to get this suspended for forty years by the payment of a large sum (80,000 ducados). King Philip II of Spain's ''Pragmatica'' of 1 January 1567 finally banned the use of Arabic throughout Spain, leading directly to the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568–71).Resistance

After Catholic conquest, Muslims in Castile, Aragon and Catalonia often used Castilian language, Castilian, Aragonese language, Aragonese and Catalan language, Catalan dialects instead of the Andalusi Arabic dialect. Mudéjar texts were then written in Castilian language, Castilian and Aragonese language, Aragonese, but in Arabic script. One example is the anonymous ''Poema de Yuçuf'', written in Aragonese but withAljamiado

''Aljamiado'' (; ; ar, عَجَمِيَة trans. ''ʿajamiyah'' ) or ''Aljamía'' texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Aragonese, Portuguese, Sp ...

Arabic script. Most of this literature consisted of religious essays, poems, and epic, imaginary narratives. Often, popular texts were translated into this Castilian-Arabic hybrid.

Much of the literature of the Moriscos focused on affirming the place of Arabic-speaking Spaniards in Spanish history and that their culture was integral to Spain. A famous example is by .

References

{{Reflist Literature of Al-Andalus, * Arabic literature European literature Islamic literature Jewish literature Medieval literature