A literary feud is a conflict or quarrel between well-known

writer

A writer is a person who uses written words in different writing styles and techniques to communicate ideas. Writers produce different forms of literary art and creative writing such as novels, short stories, books, poetry, travelogues, p ...

s, usually conducted in public view by way of published letters, speeches, lectures, and interviews. In the book ''Literary Feuds'',

Anthony Arthur describes why readers might be interested in the conflicts between writers: "we wonder how people who so vividly describe human failure (as well as triumph) can themselves fall short of perfection."

Feuds were sometimes based on conflicting views of the nature of literature as between

C. P. Snow and F. R. Leavis, or on disdain for each other's work such as the quarrel between

Virginia Woolf and Arnold Bennett. Some feuds were conducted through the writers' works, as when

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

satirized John Hervey in ''

Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot''. A few instances resulted in physical violence, such as the encounter between

Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser, and on occasion involved litigation, as in the dispute between

Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy.

History of literary feuds

A literary feud involves both a public forum and public reprisals.

Feuds might begin in the public view through the quarterlies, newspapers, and monthly magazines, but frequently extended into private correspondence and in-person meetings.

The participants are literary figures: writers, poets, playwrights, critics.

Many feuds were based on opposing philosophies of literature, art, and social issues, although the disputes often devolved into attacks on personality and character.

Feuds often have personal, political, commercial, and ideological dimensions.

In ''

Lapham's Quarterly

''Lapham's Quarterly'' is a literary magazine established in 2007 by former '' Harper's Magazine'' editor Lewis H. Lapham. Each issue examines a theme using primary source material from history. The inaugural issue "States of War" contained doze ...

'',

Hua Hsu

Hua Hsu (born 1977) is an American writer and academic, based in New York City. He is a professor of English at Bard College and a staff writer at ''The New Yorker''. His work includes investigations of immigrant culture in the United States, as ...

compares literary feuds with the one-upmanship of

hip-hop artists, "animated...by antipathy, insecurity, jealousy" and notes that "Some of the great literary feuds of the past would have been perfect for the social media age, given their withering brevity."

It is not uncommon for observers, particularly the press, to label writers' rivalries and deteriorations in friendships as feuds, such as the rivalry between sisters

A. S. Byatt and

Margaret Drabble or when

Vargas Llosa

Vargas Llosa is the surname of two prominent Peruvian intellectuals who are father and son.

*Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (born 28 March 1936), more commonly known as Mario Vargas Llosa (, ), ...

punched

Gabriel Garcia Marquez

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብር� ...

for an incident involving Llosa's wife.

During the

Romantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, feuds were encouraged by the ''

Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'', ''

Edinburgh Review'', and ''

Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine''. The first number appeared in April 1817 ...

'' as a marketing tactic. The ''Edinburgh'' editor,

Francis Jeffrey

Francis Jeffrey, Lord Jeffrey (23 October 1773 – 26 January 1850) was a Scottish judge and literary critic.

Life

He was born at 7 Charles Street near Potterow in south Edinburgh, the son of George Jeffrey, a clerk in the Court of Session ...

, wanted a nasty review in each issue, as the responses and reprisals would attract readers. Reviewers were generally anonymous, often using the collective "we" in their reviews, although the actual authorship of reviews tended to be

open secret

An open secret is a concept or idea that is "officially" (''de jure'') secret or restricted in knowledge, but in practice (''de facto'') is widely known; or it refers to something that is widely known to be true but which none of the people most i ...

s.

Thomas Love Peacock

Thomas Love Peacock (18 October 1785 – 23 January 1866) was an English novelist, poet, and official of the East India Company. He was a close friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley and they influenced each other's work. Peacock wrote satirical novels, ...

said of the ''Edinburgh'', "The mysterious ''we'' of the invisible assassin converts his poisoned dagger into a host of legitimate broadswords." ''Blackwood's'' attacked the

Cockney School {{short description, Group of 19th-century English poets and essayists

The "Cockney School" refers to a group of poets and essayists writing in England in the second and third decades of the 19th century. The term came in the form of hostile revie ...

, much as ''Edinburgh'' attacked those it dubbed the

Lake Poets

The Lake Poets were a group of English poets who all lived in the Lake District of England, United Kingdom, in the first half of the nineteenth century. As a group, they followed no single "school" of thought or literary practice then known. They ...

.

Lady Morgan

Sydney, Lady Morgan (''née'' Owenson; 25 December 1781? – 14 April 1859), was an Irish novelist, best known for '' The Wild Irish Girl'' (1806)'','' a romantic, and some critics suggest, "proto-feminist", novel with political and patriotic o ...

boasted that the ''Quarterlys attacks on her work just increased her sales.

Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake ...

described the Romantic era as "the age of personality" in which the public is preoccupied with the private lives of people in the public eye and accuses the periodicals of the time of having "a habit of malignity".

In footnotes to his ''

Biographia Literaria

The ''Biographia Literaria'' is a critical autobiography by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in 1817 in two volumes. Its working title was 'Autobiographia Literaria'. The formative influences on the work were Wordsworth's theory of poetry, th ...

'', Coleridge made accusations against Jeffrey without naming him but providing sufficient detail that others would easily know the person he meant. Through his responses, Jeffrey "magnifies a footnote into a feud", going so far as to sign his initials to his rebuttals despite the commonly accepted culture of reviewer anonymity at the time.

Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake ...

complained that media attention to his quarrel with the ''Edinburgh'' editor left him unable to escape from "the degrading Taste of the present Public for ''personal'' Gossip". ''

The British Critic

The ''British Critic: A New Review'' was a quarterly publication, established in 1793 as a conservative and high-church review journal riding the tide of British reaction against the French Revolution. The headquarters was in London. The journ ...

'' weighed in, siding with Coleridge, while ''Blackwood's'' launched its own attack on the poet.

Just as attacks could take the form of "persecution by association" in which a writer might be maligned for an actual or perceived allegiance to another writer, reprisals could bring in more participants to engage in "self-defense by association". Scholar John Sloan says of the late 19th century writers, "In the age of mass culture and the popular press, public rowing was regarded as a favourite device for the attention-seekers whose wish was to astonish and arrive."

Dr. Manfred Weidhorn, the Abraham and Irene Guterman Chair in English Literature and professor emeritus of English at

Yeshiva University

Yeshiva University is a private Orthodox Jewish university with four campuses in New York City.["About YU]

on the Yeshiva Universi ...

,

says "At least one such major confrontation appears in a different country during each of the traditional major phases of

Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

—

classical Greece,

medieval Germany

The Germani tribes i.e. Germanic tribes are now considered to be related to the Jastorf culture before expanding and interacting with the other peoples.

The concept of a region for Germanic tribes is traced to time of Julius Caesar, a Roman ge ...

,

Renaissance England,

Enlightenment France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

,

nineteenth-century Russia, modern

America."

Classical Greece

In classical Greece, poets and playwrights competed at festivals such as

City Dionysia

The Dionysia (, , ; Greek: Διονύσια) was a large festival in ancient Athens in honor of the god Dionysus, the central events of which were the theatrical performances of dramatic tragedies and, from 487 BC, comedies. It was the s ...

and

Lenaia

The Lenaia ( grc, Λήναια) was an annual Athenian festival with a dramatic competition. It was one of the lesser festivals of Athens and Ionia in ancient Greece. The Lenaia took place in Athens in Gamelion, roughly corresponding to January. T ...

. Weidhorn cites a conflict between Euripides and Sophocles as evidenced by the line in

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

's ''

Poetics'', "Sophocles said that he himself created characters such as should exist, whereas Euripides created ones such as actually do exist."

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his for ...

notably caricatured Euripides in his plays.

Centuries later,

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

and

John Davidson would refer to themselves respectively as Aristophanes and Euripides in correspondence, and their relationship would later deteriorate into a counterpart of the mythical ancient quarrel.

Medieval German

In medieval Germany,

Gottfried von Strassburg

Gottfried von Strassburg (died c. 1210) is the author of the Middle High German courtly romance ', an adaptation of the 12th-century ''Tristan and Iseult'' legend. Gottfried's work is regarded, alongside the ''Nibelungenlied'' and Wolfram von Esc ...

's ''

Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to we ...

'' and

Wolfram von Eschenbach

Wolfram von Eschenbach (; – ) was a German knight, poet and composer, regarded as one of the greatest epic poets of medieval German literature. As a Minnesinger, he also wrote lyric poetry.

Life

Little is known of Wolfram's life. There ar ...

's ''

Parzival

''Parzival'' is a medieval romance by the knight-poet Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival (Percival in English) and his long ...

'', which were published at the same time, differed on social, esthetic, and moral viewpoints, and resulted in what has been called "one of the more famous literary quarrels in medieval literature",

although that characterization based on interpretations of fragments has been disputed by other scholars.

Renaissance England

For a major confrontation in Renaissance England, Weidhorn posits

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

versus

Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

,

referring to the

War of the Theatres The War of the Theatres is the name commonly applied to a controversy from the later Elizabethan theatre; Thomas Dekker termed it the ''Poetomachia''.

Because of an actual ban on satire in prose and verse publications in 1599 (the Bishops' Ban of ...

, also known as the ''Poetomachia''. Scholars differ over the true nature and extent of the rivalry behind the Poetomachia. Some have seen it as a competition between theatre companies rather than individual writers, though this is a minority view. It has even been suggested that the playwrights involved had no serious rivalry and even admired each other, and that the "War" was a self-promotional publicity stunt, a "planned ... quarrel to advertise each other as literary figures and for profit."

Most critics see the Poetomachia as a mixture of personal rivalries and serious artistic concerns—"a vehicle for aggressively expressing differences...in literary theory...

basic philosophical debate on the status of literary and dramatic authorship."

Enlightenment France and England

The conflict between

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

and

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

in France would erupt whenever either of them published a major work, beginning with Voltaire's criticisms to Rousseau's ''

Discourse on Inequality

''Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men'' (french: Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), also commonly known as the "Second Discourse", is a 1755 work by philosopher Jean-Jacques Roussea ...

''. When Voltaire published ''

Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne

The "Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne" (English title: ''Poem on the Lisbon Disaster'') is a poem in French composed by Voltaire as a response to the 1755 Lisbon earthquake. It is widely regarded as an introduction to Voltaire's 1759 acclaimed ...

'' (English title: ''Poem on the Lisbon Disaster''), Rousseau felt the poem "exaggerated man's misery and turned God into a malevolent being". Their various disagreements escalated to Rousseau revealing that Voltaire was the author of a pamphlet Voltaire had published anonymously to avoid arrest.

In England,

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel ''Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

's novel ''

Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded

''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' is an epistolary novel, epistolary novel first published in 1740 by English writer Samuel Richardson. Considered one of the first true English novels, it serves as Richardson's version of Conduct book, conduct li ...

'' and

Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of ...

's novel ''

Shamela

''An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews'', or simply ''Shamela'', as it is more commonly known, is a satirical burlesque novella by English writer Henry Fielding. It was first published in April 1741 under the name of ''Mr. Conny Key ...

'' posed opposing views on the purpose of novels and how realism and morals should be reflected. A portion of the subtitle to ''Shamela'' was ''In which the many notorious Falsehoods and Misrepresentations of a Book called ''Pamela ''are exposed and refuted''.

Literary critic Michael LaPointe suggests that Fielding's ''Shamela'' in response to Richardson's ''Pamela'' represents an exemplary literary feud: "a serious argument about the nature of literature that takes place actually ''within'' the literary medium."

A wider ranging literary quarrel became known as the

Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns

The quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns (french: link=no, querelle des Anciens et des Modernes) began overtly as a literary and artistic debate that heated up in the early 17th century and shook the ''Académie Française''.

Origins of the ...

. In France at the end of the seventeenth century, a minor furor arose over the question of whether contemporary learning had surpassed what was known by those in Classical Greece and Rome. The "moderns" (epitomised by

Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle) took the position that the modern age of science and reason was superior to the superstitious and limited world of Greece and Rome. In Fontenelle's opinion, modern man saw farther than the ancients ever could. The "ancients," for their part, argued that all that is necessary to be known was to be found in

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

,

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

,

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, and especially

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. The dispute was satirized by

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dubl ...

in ''

The Battle of the Books

"The Battle of the Books" is the name of a short satire written by Jonathan Swift and published as part of the prolegomena to his '' A Tale of a Tub'' in 1704. It depicts a literal battle between books in the King's Library (housed in St James's ...

''.

Nineteenth-century Russia

Both

Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

and

Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

were respected writers in Russia and initially thought well of each other's work. Then Dostoyevsky objected to ''

War and Peace

''War and Peace'' (russian: Война и мир, translit=Voyna i mir; pre-reform Russian: ; ) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy that mixes fictional narrative with chapters on history and philosophy. It was first published ...

'' being referred to as an "act of genius", saying

Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

was the real genius. The writers had opposing views during

Russia's war with Turkey, and Tolstoy's view on the war as expressed in the final installment to ''

Anna Karenina

''Anna Karenina'' ( rus, «Анна Каренина», p=ˈanːə kɐˈrʲenʲɪnə) is a novel by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy, first published in book form in 1878. Widely considered to be one of the greatest works of literature ever writt ...

'' angered Dostoyevsky. Tolstoy, in turn, was critical of Dostoyevsky's work, describing ''

The Brothers Karamazov

''The Brothers Karamazov'' (russian: Братья Карамазовы, ''Brat'ya Karamazovy'', ), also translated as ''The Karamazov Brothers'', is the last novel by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky spent nearly two years writing '' ...

'' as "anti-artistic, superficial, attitudinizing, irrelevant to the great problems" and said the dialog was ""impossible, completely unnatural.... All the characters speak the same language."

Modern America

Although

Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most of ...

and

Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fi ...

respected each other's work, Faulkner told a group of college students that he ranked himself higher than Hemingway among American writers because Hemingway was "too careful, too afraid of making mistakes in diction; he lacked courage". Faulkner's remarks were leaked and published in a New York newspaper, infuriating Hemingway. Especially troubled by the comments on his courage, Hemingway requested a letter from an Army general to attest to Hemingway's bravery. Although Faulkner apologized in a letter, he would continue to make similar statements about Hemingway as a writer. Their disputes continued over the years, with Faulkner refusing to review ''

The Old Man and the Sea

''The Old Man and the Sea'' is a novella written by the American author Ernest Hemingway in 1951 in Cayo Blanco (Cuba), and published in 1952. It was the last major work of fiction written by Hemingway that was published during his lifetime. O ...

'' with what Hemingway took as a vicious insult, and Hemingway saying ''

A Fable

''A Fable'' is a 1954 novel written by the American author William Faulkner. He spent more than a decade and tremendous effort on it, and aspired for it to be "the best work of my life and maybe of my time".

It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nat ...

'' was "false and contrived".

Notable feuds

Germain de Brie and Thomas More

Germain de Brie Germain de Brie (c. 1490 – 22 July 1538), sometimes Latinized as Germanus Brixius, was a French Renaissance humanist scholar and poet. He was closely associated with Erasmus and had a well-known literary feud with Thomas More.

Early life

Germain ...

's most famous work was ''Chordigerae navis conflagratio'' ("The Burning of the Ship Cordelière") (1512), a Latin poem about the recent destruction of the Breton flagship ''Cordelière'' in the

Battle of Saint-Mathieu

The naval Battle of Saint-Mathieu took place on 10 August 1512 during the War of the League of Cambrai, near Brest, France, between an English fleet of 25 ships commanded by Sir Edward Howard and a Franco-Breton fleet of 22 ships commanded by ...

between the French and English fleets. The poem led to a literary controversy with the English scholar and statesman Sir

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, in part because it contained criticisms of English leaders, but also because of its hyperbolic account of the bravery of the Breton captain

Hervé de Portzmoguer.

In his epigrams addressed to de Brie, More ridiculed the poem's description of "Hervé fighting indiscriminately with four weapons and a shield; perhaps the fact slipped your mind, but your reader ought to have been informed in advance that Hervé had five hands.

Stung by More's attacks, de Brie wrote an aggressive reply, the Latin verse satire ''Antimorus'' (1519), including an appendix which contained a "page-by-page listing of the mistakes in More's poems".

Sir Thomas immediately wrote another hard-hitting pamphlet, ''Letter against Brixius'', but Erasmus intervened to calm the situation, and persuaded More to stop the sale of the publication and let the matter drop.

Thomas Nashe and Gabriel Harvey

The feud between

Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe (baptised November 1567 – c. 1601; also Nash) was an Elizabethan playwright, poet, satirist and a significant pamphleteer. He is known for his novel ''The Unfortunate Traveller'', his pamphlets including ''Pierce Penniless,'' ...

and

Gabriel Harvey

Gabriel Harvey (c. 1552/3 – 1631) was an English writer. Harvey was a notable scholar, whose reputation suffered from his quarrel with Thomas Nashe. Henry Morley, writing in the ''Fortnightly Review'' (March 1869), has argued that Harvey's Lati ...

was conducted through

pamphlet wars Pamphlet wars refer to any protracted argument or discussion through printed medium, especially between the time the printing press became common, and when state intervention like copyright laws made such public discourse more difficult. The purpose ...

in 16th century England and was so well known that

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's play ''

Love's Labour's Lost'' included references to the quarrel.

*In 1590, Gabriel's brother Richard criticized Nashe in his work ''The Lamb of God''.

*In 1592,

Robert Greene responded in ''A Quip for an Upstart Courtier'' with a satiric passage that ridicules a ropemaker and his three sons, which was taken to refer to Gabriel, Richard, and

John Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

* John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

* John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture ...

, but then removed it in subsequent printings.

*Nashe attacked Richard Harvey in ''Pierce Penniless'', writing "Would you, in likely reason, gesse it were possible for any shame-swolne toad to have the spet-proofe face to out live this disgrace?"

*Gabriel Harvey responded to Greene in ''Four Letters'' and in it criticized Nashe to defend his brother.

*Nashe responded with ''Strange News of Intercepting Certain Letters'' attacking Gabriel at length.

*Gabriel Harvey wrote ''Pierce's Supererogation'', however before it is published, Nashe published a letter to ''Christ's Tears'' apologizing to Harvey.

*Gabriel Harvey responded with ''A New Letter of Notable Content'', rejecting reconciliation with Nashe.

*Nashe revised his letter to ''Christ's Tears'' to respond angrily, then wrote a fuller response in ''Have with You to Saffron Walden'' in 1597, in which he claimed to continue the quarrel in order to salvage his own reputation.

*In 1599, Archbishop Whitgift and Richard Bancroft, bishop of London, banned all works by Nashe and Harvey in an order against satiric and contentious publications.

Although it began as a controversy between factions of writers, it became a personal quarrel between Nash and Gabriel Harvey after John Harvey and Robert Greene both died and Richard Harvey withdrew from participation. There is some speculation that the controversy was encouraged to sell more books.

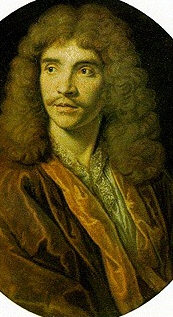

Molière and Edmé Boursault

The play ''Portrait of the Painter, or Criticisms of the School for Women Criticized'' (French: ''Le Portrait du Peintre ou La Contre-critique de L’École des femmes'', September 1663) by

Edmé Boursault was part of an ongoing literary quarrel over ''

The School for Wives

''The School for Wives'' (french: L'école des femmes; ) is a theatrical comedy written by the seventeenth century French playwright Molière and considered by some critics to be one of his finest achievements. It was first staged at the Palai ...

'' (1662) by

Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and worl ...

.

The original play had caricatured "male-dominated exploitative marital relationships", and became a target of criticism. Criticisms ranged from accusing Molière of impiety, to nitpicking over the perceived lack of realism in certain scenes. Molière had answered his critics with a second play, ''The School for Women Criticized'' (French: ''La Critique de L’École des femmes'', June 1663).

Boursault wrote his play in answer to this second play.

In ''The School for Women Criticized'', Molière poked fun at his critics by having their arguments expressed on stage by comical fools, while the character defending the original play, a mouthpiece for the writer, is a

straight man

The straight man is a stock character in a comedy performance, especially a double act, sketch comedy, or farce. When a comedy partner behaves eccentrically, the straight man is expected to maintain composure. The direct contribution to the c ...

with serious and thoughtful replies. In his ''Portrait'', Boursault imitates the structure of Molière's play but subjects the characters to a role reversal. In other words, the critics of Molière are featured as serious and his defenders as fools.

Boursault probably included other malicious and personal attacks on Molière and his associates in the stage version, which were edited out in time for publication. The modern scholar can only guess at their nature by Molière's haste to respond.

Molière answered with a third play of his own, ''The Versailles Impromptu'' (French: ''L'Impromptu de Versailles'', October 1663), which reportedly took him only eight days to write. It went on stage two weeks (or less) after the Portrait.

This play takes place in the theatrical world, featuring actors playing actors on stage. Among jests aimed at various targets, Molière mocks Boursault for his obscurity. The characters have trouble even remembering the name of someone called "Brossaut".

Molière further taunts the upstart as "a publicity-seeking hack".

Alexander Pope and John Hervey

John Hervey was the object of savage satire on the part of

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, in whose works he figured as Lord Fanny,

Sporus

Sporus was a young slave boy whom the Roman Emperor Nero favored, had castrated, and married.Champlin, 2005, p.145Smith, 1849, p.897

Life

Little is known about Sporus' background except that he was a youth to whom Nero took a liking. He may h ...

,

Adonis

In Greek mythology, Adonis, ; derived from the Canaanite word ''ʼadōn'', meaning "lord". R. S. P. Beekes, ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, p. 23. was the mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite.

One day, Adonis was gored by ...

and

Narcissus. The quarrel is generally put down to Pope's jealousy of Hervey's friendship with

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (née Pierrepont; 15 May 168921 August 1762) was an English aristocrat, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served a ...

. In the first of the ''Imitations of

Horace'', addressed to William Fortescue, Lord Fanny and Sappho were generally identified with Hervey and Lady Mary, although Pope denied the personal intention. Hervey had already been attacked in the ''Dunciad'' and the ''Peribathous'', and he now retaliated. There is no doubt that he had a share in the ''Verses to the Imitator of Horace'' (1732) and it is possible that he was the sole author. In the ''Letter from a nobleman at Hampton Court to a Doctor of Divinity'' (1733), he scoffed at Pope's deformity and humble birth.

[

Pope's reply was a ''Letter to a Noble Lord'', dated November 1733, and the portrait of Sporus in the '' Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot'' (1743), which forms the prologue to the satires. Many of the insinuations and insults contained in it are borrowed from Pulteney's ''A Proper Reply to a late Scurrilous Libel''.][

]

Ugo Foscolo and Urbano Lampredi

In 1810, Ugo Foscolo

Ugo Foscolo (; 6 February 177810 September 1827), born Niccolò Foscolo, was an Italian writer, revolutionary and a poet.

He is especially remembered for his 1807 long poem ''Dei Sepolcri''.

Early life

Foscolo was born in Zakynthos in the Io ...

wrote a satirical essay, ''Ragguaglio d'un'adunanza dell'Accademia de' Pitagorici'', that mocked a group of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

ese literary figures. One of those figures, Urbano Lampredi, responded harshly in the literary journal ''Corriere Milanese''. Foscolo's response called Lampredi "King of the league of literary charlatans". The dispute extended to the ''Il Poligrafo'' and ''Annali di scienze e lettere'' journals.

Lord Byron and John Keats

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

disdained the poetry of John Keats, the son of a livery-stable keeper, calling Keats a "Cockney poet" and referring to "Johnny Keats' piss-a-bed poetry". In turn, Keats claimed the success of Bryon's work was due more to his pedigree and appearance than any merit.

Charles Dickens, Edmund Yates, and W. M. Thackeray

In the 1850s, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

and William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

were considered competitors for novelist of the era. They were not friends, and it was well known among their fellow members of the Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a gentlemen's club in the heart of London founded in 1831. It is one of the oldest members' clubs in the world and, since its inception, has catered to members such as Charles Kean, Henry Irving, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Ar ...

that should one enter the room, the other would quickly make excuses and leave.

William Dean Howells and Edmund Stedman

In 1886, William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

and Edmund Stedman traded verbal blows in the pages of ''Harper's Monthly

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

'' and the '' New Princeton Review''. Their disagreements on the origins of literary craftsmanship and the limits of historical knowledge were reported on by other periodicals, such as ''The Critic

''The Critic'' was an American primetime adult animated sitcom revolving around the life of New York film critic Jay Sherman, voiced by Jon Lovitz. It was created by writing partners Al Jean and Mike Reiss, who had previously worked as writers a ...

'', the ''Boston Gazette

The ''Boston Gazette'' (1719–1798) was a newspaper published in Boston, in the British North American colonies. It was a weekly newspaper established by William Brooker, who was just appointed Postmaster of Boston, with its first issue release ...

'', and the ''Penny Post The Penny Post is any one of several postal systems in which normal letters could be sent for one penny. Five such schemes existed in the United Kingdom while the United States initiated at least three such simple fixed rate postal arrangements.

U ...

''. The conflict stemmed from Howell's promotion of literary realism

Literary realism is a literary genre, part of the broader realism in arts, that attempts to represent subject-matter truthfully, avoiding speculative fiction and supernatural elements. It originated with the realist art movement that began with ...

against Stedman's defense of idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected t ...

.

Marcel Proust and Jean Lorrain

Jean Lorrain

Jean Lorrain (9 August 1855 in Fécamp, Seine-Maritime – 30 June 1906), born Paul Alexandre Martin Duval, was a French poet and novelist of the Symbolist school.

Lorrain was a dedicated disciple of dandyism and spent much of his time amongs ...

wrote an unfavorable review of Marcel Proust's ''Pleasures and Days'' in which he insinuated that Proust was having an affair with Lucien Daudet

Lucien Daudet (11 June 1878 – 16 November 1946) was a French writer, the son of Alphonse Daudet and Julia Daudet. Although a prolific novelist and painter, he was never really able to trump his father's greater reputation and is now primarily ...

. Proust challenged Lorrain to a duel. The two writers exchanged shots from twenty-five paces on 5 February 1897, and neither was hit by a bullet.

Mark Twain and Bret Harte

Mark Twain and

Mark Twain and Bret Harte

Bret Harte (; born Francis Brett Hart; August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush.

In a caree ...

, both popular American writers in the nineteenth century, were colleagues, friends, and competitors. Harte, as the editor of a magazine called ''Overland Monthly'', "trimmed and trained and schooled" Twain into becoming a better writer, as Twain put it. In late 1876, Twain and Harte agreed to collaborate on a play, ''Ah Sin'', that featured the character Hop Sing from Harte's earlier play, ''Two Men of Sandy Bar

Two Men of Sandy Bar is a 1916 American silent Western Melodrama directed by Lloyd B. Carleton and starring Hobart Bosworth, Gretchen Lederer along with Emory Johnson.

The film relies on a Bret Harte play penned in 1876. The film's main chara ...

''. Neither writer was satisfied with the script that resulted, and both of them were dealing with other difficulties in their lives at the time: Harte with financial troubles and drinking, and Twain with his ''Huckleberry Finn

Huckleberry "Huck" Finn is a fictional character created by Mark Twain who first appeared in the book ''The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'' (1876) and is the protagonist and narrator of its sequel, ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' (1884). He is 12 ...

'' manuscript. The biographer Marilyn Duckett dates the estrangement between Harte and Twain to their letters in 1877, when Twain suggested that he hire Harte to work on another play with him for $25 a week (rather than lend him any money), and Harte reacted with outrage. Harte also held Twain responsible for recommending a publisher who would then mishandle Harte's novel, and declared that because of the financial losses that resulted, he need not repay Twain money he had previously borrowed. Twain described Harte's letter as "ineffable ".Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

for a diplomatic post, Twain contacted William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

, who was related by marriage to the President, to work against any such appointment, claiming that Harte would disgrace the nation. Twain's letter included "Wherever he goes his wake is tumultuous with swindled grocers & with defrauded innocents who have loaned him money...No man who has ever known him respects him." However, Harte would eventually win an appointment to Germany.

Edgar Allan Poe and Thomas Dunn English

Thomas Dunn English

Thomas Dunn English (June 29, 1819 – April 1, 1902) was an American Democratic Party politician from New Jersey who represented the state's 6th congressional district in the House of Representatives from 1891 to 1895. He was also a published ...

was a friend of author Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

, but the two fell out amidst a public scandal involving Poe and the writers Frances Sargent Osgood

Frances Sargent Osgood ( née Locke; June 18, 1811 – May 12, 1850) was an American poet and one of the most popular women writers during her time.Silverman, 281 Nicknamed "Fanny", she was also famous for her exchange of romantic poems with Edga ...

and Elizabeth F. Ellet

Elizabeth Fries Ellet ( Lummis; October 18, 1818 – June 3, 1877) was an American writer, historian and poet. She was the first writer to record the lives of women who contributed to the American Revolutionary War.

Born Elizabeth Fries Lummis, ...

. After suggestions that her letters to Poe contained indiscreet material, Ellet asked her brother to demand the return of the letters. Poe, who claimed he had already returned the letters, asked English for a pistol to defend himself from Ellet's infuriated brother.Godey's Lady's Book

''Godey's Lady's Book'', alternatively known as ''Godey's Magazine and Lady's Book'', was an American women's magazine that was published in Philadelphia from 1830 to 1878. It was the most widely circulated magazine in the period before the Civil ...

'', referring to him as "a man without the commonest school education busying himself in attempts to instruct mankind in topics of literature".secret societies

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

, and ultimately was about revenge. It included a character named Marmaduke Hammerhead, the famous author of ''The Black Crow'', who uses phrases like "Nevermore" and "lost Lenore." The clear parody of Poe was portrayed as a drunkard, liar, and domestic abuser. Poe's story "The Cask of Amontillado

"The Cask of Amontillado" (sometimes spelled "The Casque of Amontillado" ) is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in the November 1846 issue of ''Godey's Lady's Book''. The story, set in an unnamed Italian city at ca ...

" was written as a response, using very specific references to English's novel.Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Rufus Wilmot Griswold (February 13, 1815 – August 27, 1857) was an American anthologist, editor, poet, and critic. Born in Vermont, Griswold left home when he was 15 years old. He worked as a journalist, editor, and critic in Philadelphia, New Y ...

(October 1870).

Edgar Allan Poe and Rufus Wilmot Griswold

The writer Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Rufus Wilmot Griswold (February 13, 1815 – August 27, 1857) was an American anthologist, editor, poet, and critic. Born in Vermont, Griswold left home when he was 15 years old. He worked as a journalist, editor, and critic in Philadelphia, New Y ...

first met Poe in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

in May 1841 while working for the ''Daily Standard''.The Haunted Palace

''The Haunted Palace'' is a 1963 horror film released by American International Pictures, starring Vincent Price, Lon Chaney Jr. and Debra Paget (in her final film), in a story about a village held in the grip of a dead necromancer. The film wa ...

", and "The Sleeper".Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

periodical. The review was generally favorable, although Poe questioned the inclusion of certain authors and the omission of others.humbug

A humbug is a person or object that behaves in a deceptive or dishonest way, often as a hoax or in jest. The term was first described in 1751 as student slang, and recorded in 1840 as a "nautical phrase". It is now also often used as an exclama ...

" in a letter to a friend.Frances Sargent Osgood

Frances Sargent Osgood ( née Locke; June 18, 1811 – May 12, 1850) was an American poet and one of the most popular women writers during her time.Silverman, 281 Nicknamed "Fanny", she was also famous for her exchange of romantic poems with Edga ...

in the mid to late 1840s.The Caxtons

''The Caxtons: A Family Picture'' is an 1849 Victorian novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton that was popular in its time.Sutherland, JohnThe Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction p. 111 (1989)

The book was first serialized anonymously in ''Blackw ...

'' by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.literary executor

The literary estate of a deceased author consists mainly of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of published works, including film, translation rights, original manuscripts of published work, unpublished or partially completed w ...

"for the benefit of his family".Nathaniel Parker Willis

Nathaniel Parker Willis (January 20, 1806 – January 20, 1867), also known as N. P. Willis,Baker, 3 was an American author, poet and editor who worked with several notable American writers including Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfello ...

, edited a posthumous collection of Poe's works published in three volumes starting in January 1850.Sarah Helen Whitman

Sarah Helen Power Whitman (January 19, 1803 – June 27, 1878) was an American poet, essayist, transcendentalist, spiritualist and a romantic interest of Edgar Allan Poe.

Early life

Whitman was born in Providence, Rhode Island on January 19, ...

, Charles Frederick Briggs, and George Rex Graham.University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

and that Poe had tried to seduce his guardian John Allan's second wife.

Virginia Woolf and Arnold Bennett

Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist. He wrote prolifically: between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboratio ...

wrote an article called "Is the Novel Decaying?" in 1923 in which, as an example, he criticized Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

's characterizations in ''Jacob's Room

''Jacob's Room'' is the third novel by Virginia Woolf, first published on 26 October 1922.

The novel centres, in a very ambiguous way, around the life story of the protagonist Jacob Flanders and is presented almost entirely through the impressi ...

''. Woolf responded with "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" in the ''Nation and Athenaeum''. In her piece, Woolf misquoted Bennett's article and displayed ill temper. She then significantly rewrote "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown

''Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown'' is an essay by Virginia Woolf published in 1924 which explores modernity.

History

The writer Arnold Bennett had written a review of Woolf's '' Jacob's Room'' (1922) in '' Cassell's Weekly'' in March 1923, which ...

" "to ridicule, patronize, and actually distort Bennett's writing without raising her voice."Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'', giving negative reviews of three of Woolf's novels. His reviews continued the attack on Woolf's characterizations, saying "Mrs. Woolf (in my opinion) told us ten thousand things about Mrs. Dalloway, but did not show us Mrs. Dalloway." His essay "The Progress of the Novel" for the journal ''The Realist

''The Realist'' was a Humor magazine, magazine of "social-political-religious criticism and satire", intended as a hybrid of a grown-ups version of Mad (magazine), ''Mad'' and Lyle Stuart's anti-censorship monthly ''The Independent.'' Edited and ...

'' was a refutation of "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown". Of Woolf, he says ""I regard her alleged form as the absence of form, and her psychology as an uncoordinated mass of interesting details, none of which is truly original."

Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson

The feud between Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

and Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publi ...

began in 1965. After a twenty-five year friendship which was at times strained due to Nabokov's disdain for Wilson's political views and then later by Wilson's criticism of '' Lolita'',Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

's ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Евгений Оне́гин, ромáн в стихáх, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn, r=Yevgeniy Onegin, roman v stikhakh) is ...

''.Encounter

Encounter or Encounters may refer to:

Film

*''Encounter'', a 1997 Indian film by Nimmala Shankar

* ''Encounter'' (2013 film), a Bengali film

* ''Encounter'' (2018 film), an American sci-fi film

* ''Encounter'' (2021 film), a British sci-fi film

* ...

'' and the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British Political magazine, political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney Webb, Sidney and Beatrice ...

''. Other writers, such as Anthony Burgess

John Anthony Burgess Wilson, (; 25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993), who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was an English writer and composer.

Although Burgess was primarily a comic writer, his dystopian satire ''A Clockwork ...

, Robert Lowell, V. S. Pritchett, Robert Graves, and Paul Fussell

Paul Fussell Jr. (22 March 1924 – 23 May 2012) was an American cultural and literary historian, author and university professor. His writings cover a variety of topics, from scholarly works on eighteenth-century English literature to commenta ...

joined in the dispute.

Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal

In 1971, Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal (; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his epigrammatic wit, erudition, and patrician manner. Vidal was bisexual, and in his novels and e ...

compared Norman Mailer to Charles Manson in Vidal's review of '' The Prisoner of Sex''.The Dick Cavett Show

''The Dick Cavett Show'' was the title of several talk shows hosted by Dick Cavett on various television networks, including:

* ABC daytime, (March 4, 1968–January 24, 1969) originally titled ''This Morning''

* ABC prime time, Tuesdays, We ...

'', Mailer punched Vidal in the hospitality room, then brought up the review again on the live show.

Gore Vidal and Truman Capote

Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal (; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his epigrammatic wit, erudition, and patrician manner. Vidal was bisexual, and in his novels and e ...

and Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

were competitive acquaintances who were, initially, cordial. Their first open argument began at a party hosted by Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983), known by his pen name Tennessee Williams, was an American playwright and screenwriter. Along with contemporaries Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the thr ...

. Williams said, "They began to criticize each other's work. Gore told Truman he got all of his plots out of Carson McCullers

Carson McCullers (February 19, 1917 – September 29, 1967) was an American novelist, short-story writer, playwright, essayist, and poet. Her first novel, '' The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter'' (1940), explores the spiritual isolation of misfits ...

and Eudora Welty

Eudora Alice Welty (April 13, 1909 – July 23, 2001) was an American short story writer, novelist and photographer who wrote about the American South. Her novel '' The Optimist's Daughter'' won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973. Welty received numerou ...

. Truman said 'Well, maybe you get all of yours from the ''Daily News''.' And so the fight was on."Lee Radziwill

Caroline Lee Bouvier ( ), later Canfield, Radziwiłł (), and Ross (March 3, 1933 – February 15, 2019), usually known as Princess Lee Radziwill, was an American socialite, public-relations executive, and interior decorator. She was the y ...

refused to testify on Capote's behalf.

John Updike, Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, and John Irving

Because of the success of Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

's best selling novel, ''Bonfire of the Vanities

A bonfire of the vanities ( it, falò delle vanità) is a burning of objects condemned by religious authorities as occasions of sin. The phrase itself usually refers to the bonfire of 7 February 1497, when supporters of the Dominican friar G ...

'', there was widespread interest in his next book. This novel took him more than 11 years to complete; ''A Man in Full

''A Man in Full'' is the second novel by Tom Wolfe, published on November 12, 1998, by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. It is set primarily in Atlanta, with a significant portion of the story also transpiring in the East Bay region of the San Francisco B ...

'' was published in 1998. The book's reception was not universally favorable, though it received glowing reviews in ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'', ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'', ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'', and elsewhere. Noted author John Updike wrote a critical review for ''The New Yorker'', complaining that the novel "amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form."John Irving

John Winslow Irving (born John Wallace Blunt Jr.; March 2, 1942) is an American-Canadian novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter.

Irving achieved critical and popular acclaim after the international success of ''The World According to ...

and Norman Mailer who also entered the fray, with Irving saying in a television interview, "He's not a writer...You couldn't teach that bleeping bleep to bleeping freshmen in a bleeping freshman English class!."

Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser

In 1927, Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

and Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

's soon-to-be wife Dorothy Thompson spent some time together while they were both visiting Russia. The next year, Thompson published ''The New Russia''. Several months later, Dreiser published ''Dreiser Looks at Russia''. Thompson and Lewis accused Dreiser of plagiarizing portions of Thompson's work, which Dreiser denied and claimed instead that Thompson had used material of his.Metropolitan Club

The Metropolitan Club of New York is a private social club on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded as a gentlemen's club in 1891 for men only, but it was one of the first major clubs in New York to admit women, t ...

at a dinner honoring Boris Pilnyak

Boris Andreyevich Pilnyak (''né'' Vogau russian: Бори́с Андре́евич Пильня́к; – April 21, 1938) was a Russian and Soviet writer who was executed by the Soviet Union on false claims of plotting to kill Joseph Stalin and ...

. After much drinking, Lewis rose to give the welcome speech, but instead declared he "did not care to speak in the presence of a man who has stolen three thousand words from my wife's book."

C. P. Snow and F. R. Leavis

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

scientist and novelist C. P. Snow

Charles Percy Snow, Baron Snow, (15 October 1905 – 1 July 1980) was an English novelist and physical chemist who also served in several important positions in the British Civil Service and briefly in the UK government.''The Columbia Encyclope ...

delivered ''The Two Cultures'', the first part of an influential 1959 Rede Lecture

The Sir Robert Rede's Lecturer is an annual appointment to give a public lecture, the Sir Robert Rede's Lecture (usually Rede Lecture) at the University of Cambridge. It is named for Sir Robert Rede, who was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in th ...

, on 7 May 1959 .British education

Education in the United Kingdom is a devolved matter with each of the countries of the United Kingdom having separate systems under separate governments: the UK Government is responsible for England; whilst the Scottish Government, the Welsh G ...

al system as having, since the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, over-rewarded the humanities (especially Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) at the expense of scientific and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

education, despite such achievements having been so decisive in winning the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

for the Allies.F. R. Leavis

Frank Raymond "F. R." Leavis (14 July 1895 – 14 April 1978) was an English literary critic of the early-to-mid-twentieth century. He taught for much of his career at Downing College, Cambridge, and later at the University of York.

Leavis ra ...

was incensed by Snow's implication that, in the alliance between the sciences and the humanities, literary intellectuals were the "junior partner".The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' in 1962The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'' declared Leavis was acting out of "pure hysteria" and was displaying "persecution mania".

Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy

Mary McCarthy's feud with Lillian Hellman

Lillian Florence Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American playwright, prose writer, memoirist and screenwriter known for her success on Broadway, as well as her communist sympathies and political activism. She was blacklisted aft ...

had simmered since the late 1930s over ideological differences, particularly the questions of the Moscow Trials and of Hellman's support for the "Popular Front" with Stalin.PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

.

Salman Rushdie and John le Carré

During ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel of British-Indian writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical realism ...

'' controversy, le Carré stated that Rushdie's insistence on publishing the paperback was putting lives at risk.The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' and ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

''.

Paul Theroux and V. S. Naipaul

Paul Theroux and V. S. Naipaul

Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (; 17 August 1932 – 11 August 2018) was a Trinidadian-born British writer of works of fiction and nonfiction in English. He is known for his comic early novels set in Trinidad, his bleaker novels of alienati ...

met in 1966 in Kampala

Kampala (, ) is the capital and largest city of Uganda. The city proper has a population of 1,680,000 and is divided into the five political divisions of Kampala Central Division, Kawempe Division, Makindye Division, Nakawa Division, and Ruba ...

, Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

. Their friendship cooled when Theroux criticized Naipaul's work. Later, Theroux took offense when he found books he had inscribed to Naipaul offered for sale in a rare books catalog.

V. S. Naipaul and Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott and V. S. Naipaul were both from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

,The Enigma of Arrival

''The Enigma of Arrival: A Novel in Five Sections'' is a 1987 novel by Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul.

Mostly an autobiography, the book is composed of five sections that reflect the growing familiarity and changing perceptions of Naipaul upon h ...

'' in 1987, writing "The myth of Naipaul...has long been a farce." Naipaul countered in 2007, praising Walcott's early work, then describing him as "a man whose talent had been all but strangled by his colonial setting" and saying "He went stale".Calabash International Literary Festival The Calabash International Literary Festival is a three-day festival in Jamaica staged on a biennial basis on even years (having been held annually in its first decade). in 2008.

Richard Ford and multiple writers

Alice Hoffman

Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1995 novel ''Practical Magic'', which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. Many of her works fall into the genre of ...

reviewed Richard Ford

Richard Ford (born February 16, 1944) is an American novelist and short story writer. His best-known works are the novel ''The Sportswriter'' and its sequels, ''Independence Day'', ''The Lay of the Land'' and ''Let Me Be Frank With You'', and the ...

's novel '' Independence Day'' for The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

. The review contained some criticisms, which Ford described as "nasty things", and Ford claimed his response was to shoot one of Hoffman's books and send it to her. In an interview, Ford said "But people make such a big deal out of it - shooting a book - it's not like I shot her."Colson Whitehead

Arch Colson Chipp Whitehead (born November 6, 1969) is an American novelist. He is the author of eight novels, including his 1999 debut work '' The Intuitionist''; '' The Underground Railroad'' (2016), for which he won the 2016 National Book Awar ...

wrote an unfavorable review of Ford's book ''A Multitude of Sins'' for The New York Times. When the two writers encountered each other at a party several years later, Ford told Whitehead, "You’re a kid, you should grow up", and then spat in Whitehead's face.Viet Thanh Nguyen

The Vietnamese people ( vi, người Việt, lit=Viet people) or Kinh people ( vi, người Kinh) are a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to modern-day Northern Vietnam and Southern China (Jing Islands, Dongxing, Guangxi). The native lang ...

, Sarah Weinman, and Saeed Jones

Saeed Jones (born November 26, 1985) is an American writer and poet. His debut collection '' Prelude to Bruise'' was named a 2014 finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. His second book, a memoir, '' How We Fight for Our ...

, criticized the decision, citing Ford's history of poor conduct.

See also

*Mac Flecknoe

''Mac Flecknoe'' (full title: ''Mac Flecknoe; or, A satyr upon the True-Blue-Protestant Poet, T.S.''Cox, Michael, editor, ''The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2004, ) is a verse mock-heroic satire writte ...

* Isaac Bickerstaff

* Fleshly School

* Who Is the Bad Art Friend?

References

{{reflist, refs=

[{{Cite news, url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2017/jun/14/richard-ford-pride-colson-whitehead-bad-review, title=Richard Ford should swallow his pride over Colson Whitehead's bad review, last=Armitstead, first=Claire, date=14 June 2017, work=The Guardian, access-date=3 December 2019, language=en-GB, issn=0261-3077]

[{{Cite book, title=Literary feuds : a century of celebrated quarrels from Mark Twain to Tom Wolfe, last=Arthur, Anthony., date=2002, publisher=MJF Books, isbn=1-56731-681-6, location=New York, oclc=60705284]

[{{cite book, last=Barrett, first= David, title=The Frogs and Other Plays, publisher= Penguin Books, isbn=9780141935775, date= March 2007]

[{{Cite news, url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/feb/08/featuresreviews.guardianreview28, title=Guardian profile: Richard Ford, last=Barton, first=Laura, date=8 February 2003, work=The Guardian, access-date=3 December 2019, language=en-GB, issn=0261-3077]

[{{cite book, last=Bayless, first= Joy, title= Rufus Wilmot Griswold: Poe's Literary Executor , publisher= Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, pages=75–76, 164–167]

[{{Cite book, title=The feud : Vladimir Nabokov, Edmund Wilson, and the end of a beautiful friendship, last=Beam, Alex, isbn=978-1-101-87022-8, edition=First, location=New York, oclc=944933725, pages=109; 113–129, year = 2016]

[{{Cite book, url=https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/1208420, title=Creole Renegades: Rhetoric of Betrayal and Guilt in the Caribbean Diaspora, last=Boisseron, first=Bénédicte, date=2014, publisher=University Press of Florida, isbn=978-0-8130-4891-8, pages=143–144, language=en]

[{{Cite book, title=Literary rivals: feuds and antagonisms in the world of books, last=Bradford, first=Richard, isbn=978-1-84954-602-7, location=London, oclc=856200735, year=2014, url-access=registration, url=https://archive.org/details/literaryrivalsfe0000brad]

[{{Cite web, url=https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2012/11/12/164984367/salman-rushdie-john-le-carre-end-literary-feud, title=Salman Rushdie, John Le Carre End Literary Feud, last=Calamur, first=Krishnadev, date=12 Nov 2012, website=NPR.org, language=en, access-date=22 December 2019]

[{{Citation, title=Gore Vidal vs Norman Mailer, The Dick Cavett Show, url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nb1w_qoioOk, website=YouTube, language=en, access-date=28 November 2019]

[{{Cite news, url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/29/books/29marq.html, title=Gabriel García Márquez - Mario Vargas Llosa - Feud, last=Cohen, first=Noam, date=29 March 2007, work=The New York Times, access-date=2 January 2020, language=en-US, issn=0362-4331]

[{{EB1911 , wstitle=Hervey of Ickworth, John Hervey, Baron , volume=13 , pages=404–405 , inline=1]

[{{Cite news, url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/05/richard-ford-literary-honour-questioned-by-peers-paris-review-hadada-prize, title=Richard Ford's literary honour questioned by peers after history of aggressive behaviour, last=Flood, first=Alison, date=5 November 2019, work=The Guardian, access-date=3 December 2019, language=en-GB, issn=0261-3077]

[{{Cite book, last=Forman, first= Edward, year=2010, title= Historical Dictionary of French Theater, publisher= Scarecrow Press, isbn=978-0810874510, pages= 204–205]

[{{cite book, last=Gaines, first= James F. , year=2002, title= The Molière encyclopedia, publisher= Greenwood Publishing Group, isbn=978-0313312557, page=65]

[{{cite book, author=Will Hasty, title=A Companion to Gottfried Von Strassburg's "Tristan", url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P0xHJws5adUC&pg=PA261, year=2003, publisher=Camden House, isbn=978-1-57113-203-1, page=261]

[{{Cite journal, last=Heddendorf, first=David, date=Summer 2014, title=The Literary Feud, journal=Sewanee Review, volume=122, issue=3, pages=473–478, doi=10.1353/sew.2014.0072]

[{{Cite book, title=The singularity of Thomas Nashe, last=Hilliard, first=Stephen S, date=1986, publisher=University of Nebraska Press, isbn=0-8032-2326-9, location=Lincoln, pages=169–177, oclc=12420505]