Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to

war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

,

militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

(including

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

and mandatory military service) or

violence

Violence is the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. Other definitions are also used, such as the World Health Organization's definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or Power (social and p ...

. Pacifists generally reject theories of

Just War

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war is m ...

. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner

Ãmile Arnaud

Ãmile Arnaud (1864â1921) was a French lawyer, notary, and writer noted for his anti-war rhetoric and for coining the term "pacifism". Arnaud founded the "Ligue Internationale de la Paix et de la Liberté" (International League for Peace and Free ...

and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

in 1901. A related term is ''

ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiá¹sÄ'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India â ...

'' (to do no harm), which is a core philosophy in

Indian Religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

such as

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2â1.35 billion followers, or 15â16% of the global p ...

,

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, and

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

. While modern connotations are recent, having been explicated since the 19th century, ancient references abound.

In modern times, interest was revived by

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Ðев ÐÐ¸ÐºÐ¾Ð»Ð°ÐµÐ²Ð¸Ñ Ð¢Ð¾Ð»ÑÑой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

in his late works, particularly in ''

The Kingdom of God Is Within You

''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, ЦаÑÑÑво Ðожие внÑÑÑи ваÑ, Tsárstvo Bózhiye vnutrà vas) is a non-fiction book written by Leo Tolstoy. A Christian anarchist philosophical treat ...

''.

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 â 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

propounded the practice of steadfast

nonviolent opposition which he called "

satyagraha

Satyagraha ( sa, सतà¥à¤¯à¤¾à¤à¥à¤°à¤¹; ''satya'': "truth", ''Ägraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone w ...

", instrumental in its role in the

Indian Independence Movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

. Its effectiveness served as inspiration to

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 â April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

,

James Lawson, Mary and Charles Beard,

James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 â December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

,

Thich Nhat Hanh ThÃch is a name that Vietnamese monks and nuns take as their Buddhist surname to show affinity with the Buddha.

Notable Vietnamese monks with the name include:

*ThÃch Huyá»n Quang (1919â2008), dissident and activist

*ThÃch Quảng Äá» (192 ...

,

["Searching for the Enemy of Man", in Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien. ''Dialogue''. Saigon: La Boi, 1965. pp. 11â20., archived on the African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War website]

King's Journey: 1964 â April 4, 1967

and many others in the

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

.

Definition

Pacifism covers a spectrum of views, including the belief that international disputes can and should be peacefully resolved, calls for the abolition of the institutions of the military and war, opposition to any organization of society through governmental force (

anarchist or libertarian pacifism), rejection of the use of physical violence to obtain political, economic or social goals, the obliteration of force, and opposition to violence under any circumstance, even defence of self and others. Historians of pacifism

Peter Brock

Peter Geoffrey Brock (26 February 1945 â 8 September 2006), known as "Peter Perfect", "The King of the Mountain", or simply "Brocky", was an Australian motor racing driver. Brock was most often associated with Holden for almost 40 years, al ...

and Thomas Paul Socknat define pacifism "in the sense generally accepted in English-speaking areas" as "an unconditional rejection of all forms of warfare". Philosopher

Jenny Teichman

Jenny Teichman (1930 â 12 September 2018) was an Australian-British philosopher, writing mostly on ethics. She was born in Melbourne, Australia in 1930 and lived as a child in the artists' colony of Montsalvat. She married the lecturer and p ...

defines the main form of pacifism as "anti-warism", the rejection of all forms of warfare. Teichman's beliefs have been summarized by

Brian Orend

Brian Orend is the Director of International Studies and a professor of Philosophy at the University of Waterloo in Waterloo, Ontario.

Orend's works focus on just war theory and human rights. He is best known for his discussions of ''jus post bel ...

as "... A pacifist rejects war and believes there are no moral grounds which can justify resorting to war. War, for the pacifist, is always wrong." In a sense the philosophy is based on the idea that the ends do not justify the means. The word ''

pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

'' denotes conciliatory.

Moral considerations

Pacifism may be based on

moral

A moral (from Latin ''morÄlis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. A ...

principles (a

deontological

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek: + ) is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules and principles, ra ...

view) or

pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

(a

consequentialist

In ethical philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative ethics, normative, Teleology, teleological ethical theories that holds that the wikt:consequence, consequences of one's Action (philosophy), conduct are the ultimate basis for judgm ...

view). Principled pacifism holds that at some point along the spectrum from war to interpersonal physical violence, such violence becomes morally wrong. Pragmatic pacifism holds that the costs of war and interpersonal violence are so substantial that better ways of resolving disputes must be found.

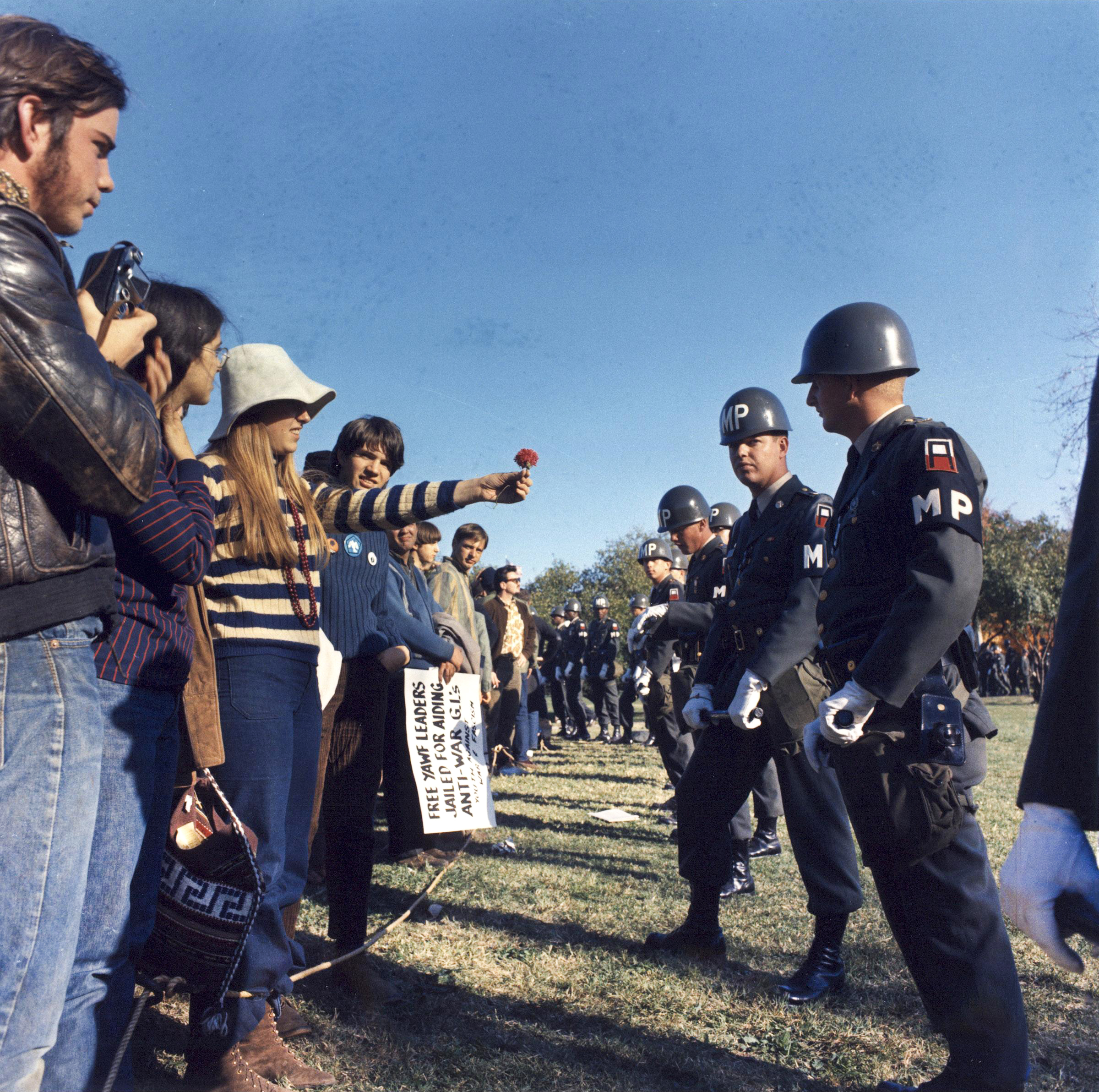

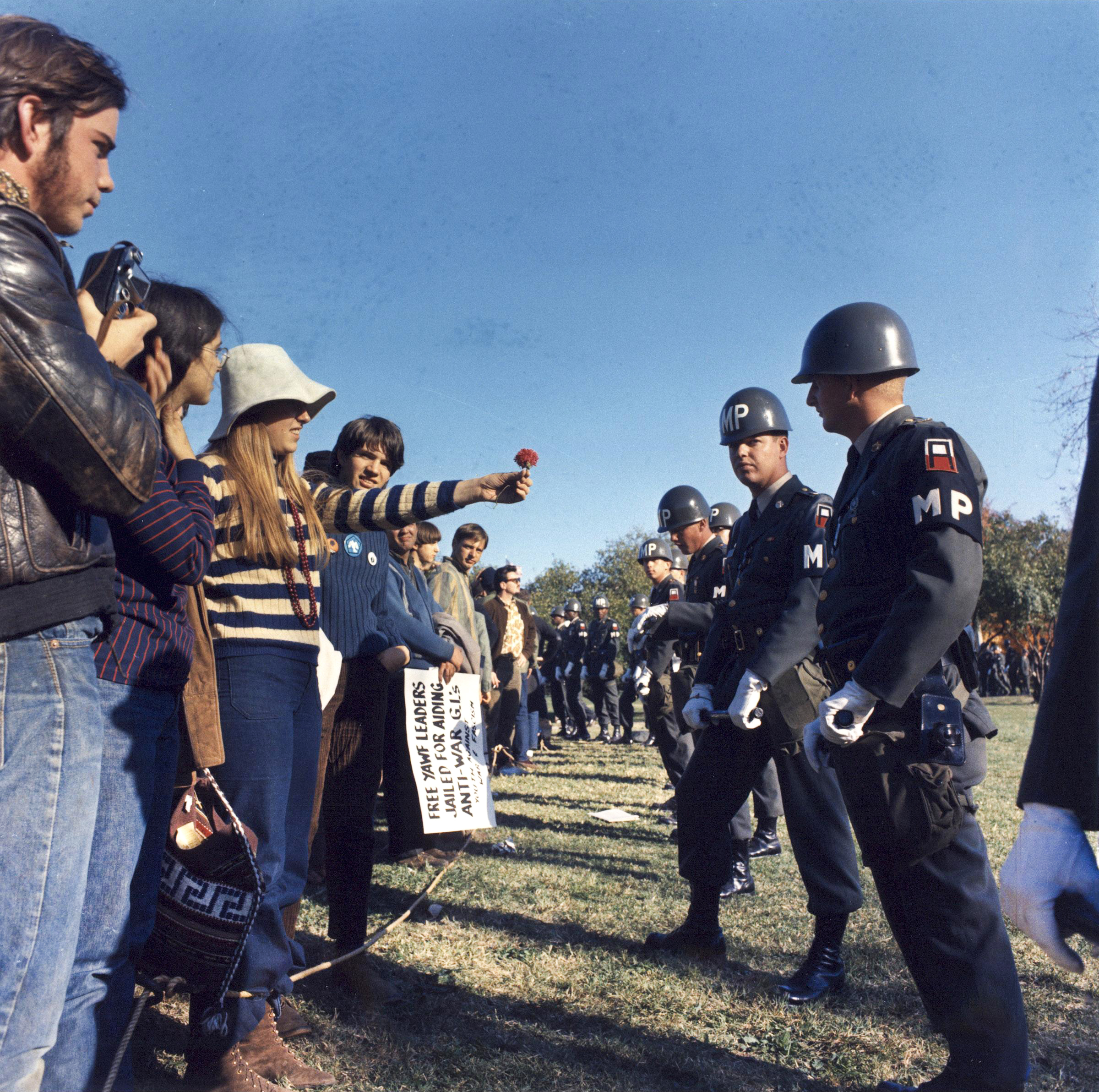

Nonviolence

Some pacifists follow principles of

nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

, believing that nonviolent action is morally superior and/or most effective. Some however, support physical violence for emergency defence of self or others. Others support

destruction of property

Property damage (or cf. criminal damage in England and Wales) is damage or destruction of real or tangible personal property, caused by negligence, willful destruction, or act of nature.

It is similar to vandalism and arson (destroying propert ...

in such emergencies or for conducting symbolic acts of resistance like pouring red paint to represent blood on the outside of military recruiting offices or entering air force bases and hammering on military aircraft.

Not all

nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, cons ...

(sometimes also called

civil resistance

Civil resistance is political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and coercion: i ...

) is based on a fundamental rejection of all violence in all circumstances. Many leaders and participants in such movements, while recognizing the importance of using non-violent methods in particular circumstances, have not been absolute pacifists. Sometimes, as with the civil rights movement's march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, they have called for armed protection. The interconnections between civil resistance and factors of force are numerous and complex.

Types

Absolute pacifism

An absolute pacifist is generally described by the

BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

as one who believes that human life is so valuable, that a human should never be killed and war should never be conducted, even in self-defense. The principle is described as difficult to abide by consistently, due to violence not being available as a tool to aid a person who is being harmed or killed. It is further claimed that such a pacifist could logically argue that violence leads to more undesirable results than non-violence.

Conditional pacifism

Tapping into

just war theory

The just war theory ( la, bellum iustum) is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics which is studied by military leaders, theologians, ethicists and policy makers. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure that a war is m ...

''conditional pacifism'' represents a spectrum of positions departing from positions of absolute pacifism. One such conditional pacifism is the common

pacificism

Pacificism is the general term for ethical opposition to violence or war unless force is deemed necessary. Together with pacifism, it is born from the Western tradition or attitude that calls for peace. The former involves the unconditional refus ...

, which may allow defense but is not advocating a default

defensivism

Defensivism is a philosophical standpoint related in spirit to the non-aggression principle. It is a halfway point between other combat or violence based philosophies, such as just war and pacifism.

Concept

Defensivism has a standpoint that onl ...

or even

interventionism.

Police actions and national liberation

Although all pacifists are opposed to war between

nation states

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may in ...

, there have been occasions where pacifists have supported military conflict in the case of

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

or

revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

.

["When the American Civil War broke out ... both the American Peace Society and many former nonresistants argued that the conflict was not properly war but rather police action on a grand scale" Brock, Peter, ''Freedom from War: Nonsectarian Pacifism, 1814â1914'' University of Toronto Press, 1991 , (p. 176)] For instance, during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 â May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, both the

American Peace Society

The American Peace Society is a pacifist group founded upon the initiative of William Ladd, in New York City, May 8, 1828. It was formed by the merging of many state and local societies, from New York, Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, of ...

and some former members of the

Non-Resistance Society The New England Non-Resistance Society was an American peace group founded at a special peace convention organized by William Lloyd Garrison, in Boston in September 1838.Peter Brock ''Pacifism in the United States, from the Colonial era to the First ...

supported the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

's military campaign, arguing they were carrying out a "

police action

In military/security studies and international relations, police action is a military action undertaken without a formal declaration of war. Today the term counter-insurgency is more used.

Since World War II, formal declarations of war have bee ...

" against the

Confederacy, whose act of

Secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

they regarded as criminal.

Following the outbreak of the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, French pacifist

René Gérin

René (''Born again (Christianity), born again'' or ''reborn'' in French language, French) is a common given name, first name in French-speaking, Spanish-speaking, and German-speaking countries. It derives from the Latin name Renatus.

René is th ...

urged support for the

Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

.

[Ingram, Norman. ''The Politics of Dissent : Pacifism in France, 1919â1939''. University of Edinburgh, 1988. (p. 219)] Gérin argued that the

Spanish Nationalists

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

were "comparable to an individual enemy" and the Republic's war effort was equivalent to the action of a domestic police force suppressing crime.

In the 1960s, some pacifists associated with the

New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

supported

wars of national liberation

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separat ...

and supported groups such as the

Viet Cong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

and the Algerian

FLN, arguing peaceful attempts to liberate such nations were no longer viable, and war was thus the only option.

History

Early traditions

Advocacy of pacifism can be found far back in history and literature.

China

During the

Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

, the pacifist

Mohist

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an Chinese philosophy#Ancient philosophy, ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC ...

School opposed aggressive war between the feudal states. They took this belief into action by using their famed defensive strategies to defend smaller states from invasion from larger states, hoping to dissuade feudal lords from costly warfare. The

Seven Military Classics

The Seven Military Classics () were seven important military texts of ancient China, which also included Sun-tzu's ''The Art of War''. The texts were canonized under this name during the 11th century AD, and from the time of the Song dynasty, wer ...

of ancient China view warfare negatively, and as a last resort. For example, the ''

Three Strategies of Huang Shigong

The ''Three Strategies of Huang Shigong'' () is a treatise on military strategy that was historically associated with the Taoist hermit Huang Shigong and Han dynasty general Zhang Liang. Huang Shigong gave this treatise to Zhang Liang, that all ...

'' says: "As for the military, it is not an auspicious instrument; it is the way of heaven to despise it", and the ''

Wei Liaozi

The ''Wei Liaozi'' () is a text on military strategy, one of the Seven Military Classics of ancient China. It was written during the Warring States period.

History and authorship

The work is purportedly named after Wei Liao, who is said to have ...

'' writes: "As for the military, it is an inauspicious instrument; as for conflict and contention, it runs counter to virtue".

The Taoist scripture "''Classic of Great Peace'' (''

Taiping jing

''Taipingjing'' ("Scriptures of the Great Peace") is the name of several different Taoist texts. At least two works were known by this title:

:*, 12 Chapters, contents unknown, author: Gan Zhongke

:*, 170 Chapters, only 57 of which survive v ...

'')" foretells "the coming Age of Great Peace (''Taiping'')". The ''Taiping Jing'' advocates "a world full of peace".

Lemba

The

Lemba Lemba may refer to:

* ''Lemba'' (grasshopper), a genus of insect in the subfamily Caryandinae

* Lemba people, an African ethnic group in Southern Africa

;Places

* Lemba, Kinshasa, a commune in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Lembá ...

religion of southern French Congo, along with its symbolic herb, is named for pacifism : "''lemba, lemba''" (peace, peace), describes the action of the plant ''lemba-lemba'' (''Brillantaisia patula T. Anders''). Likewise in Cabinda, "''Lemba'' is the spirit of peace, as its name indicates."

Moriori

The

Moriori

The Moriori are the native Polynesian people of the Chatham Islands (''RÄkohu'' in Moriori; ' in MÄori), New Zealand. Moriori originated from MÄori settlers from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 CE. This was near the time of the ...

, of the

Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands ( ) (Moriori: ''RÄkohu'', 'Misty Sun'; mi, Wharekauri) are an archipelago in the Pacific Ocean about east of New Zealand's South Island. They are administered as part of New Zealand. The archipelago consists of about te ...

, practiced pacifism by order of their ancestor

Nunuku-whenua

Nunuku-whenua was a Moriori chief who is known for being a sixteenth-century pacifist.

The Moriori, a Polynesian people, migrated to the then-uninhabited Chatham Islands from mainland New Zealand around the year 1500. Following an intertribal con ...

. This enabled the Moriori to preserve what limited resources they had in their harsh climate, avoiding waste through warfare. In turn, this led to their almost complete annihilation in 1835 by invading

NgÄti Mutunga

NgÄti Mutunga is a MÄori iwi (tribe) of New Zealand, whose original tribal lands were in north Taranaki. They migrated from Taranaki, first to Wellington (with NgÄti Toa and other Taranaki HÄpu), and then to the Chatham Islands (along with ...

and

NgÄti Tama

NgÄti Tama is a historic MÄori iwi of present-day New Zealand which whakapapas back to Tama Ariki, the chief navigator on the Tokomaru waka. The iwi of Ngati Tama is located in north Taranaki around Poutama. The MÅhakatino river marks their ...

MÄori

MÄori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the MÄori people

* MÄori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* MÄori language, the language of the MÄori people of New Zealand

* MÄori culture

* Cook Islanders, the MÄori people of the C ...

from the

Taranaki

Taranaki is a region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano of Mount Taranaki, also known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the city of New Plymouth. The New Plymouth Dist ...

region of the

North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-MÄui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

of New Zealand. The invading MÄori killed, enslaved and

cannibalised

Biomechanical are an English heavy metal band from London. The band was founded in April 1999 by John K, who wrote, recorded and arranged all of the music, with the exception of the songs "Existenz" and "Survival" which were co-written by Chr ...

the Moriori. A Moriori survivor recalled : "

he Maori

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana ã¸

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

commenced to kill us like sheep ...

ewere terrified, fled to the bush, concealed ourselves in holes underground, and in any place to escape our enemies. It was of no avail; we were discovered and killed â men, women and children indiscriminately."

Greece

In

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, á¼Î»Î»Î¬Ï, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12thâ9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, pacifism seems not to have existed except as a broad moral guideline against violence between individuals. No philosophical program of rejecting violence between states, or rejecting all forms of violence, seems to have existed. Aristophanes, in his play

Lysistrata

''Lysistrata'' ( or ; Attic Greek: , ''LysistrátÄ'', "Army Disbander") is an ancient Greek comedy by Aristophanes, originally performed in classical Athens in 411 BC. It is a comic account of a woman's extraordinary mission to end the Peloponne ...

, creates the scenario of an

Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Îθήνα, AthÃna ; grc, á¼Î¸á¿Î½Î±Î¹, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

woman's anti-war sex strike during the

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431â404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

of 431â404 BC, and the play has gained an international reputation for its anti-war message. Nevertheless, it is both fictional and comical, and though it offers a pragmatic opposition to the destructiveness of war, its message seems to stem from frustration with the existing conflict (then in its twentieth year) rather than from a philosophical position against violence or war. Equally fictional is the nonviolent protest of

Hegetorides Hegetorides ( grc, ἩγηÏοÏίδηÏ) was a citizen of the Greek island of Thasos during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431-404 BC), mentioned by the 2nd-century historian Polyaenus.Stratagems 2.33 Lemprière's ''Classica ...

of

Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, ÎάÏοÏ, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate re ...

.

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Îá½ÏιÏίδηÏ, EurÄ«pÃdÄs, ; ) was a tragedian

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, ÏÏαγῳδία, ''tragÅidia'', ''tragÅidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful e ...

also expressed strong anti-war ideas in his work, especially ''

The Trojan Women

''The Trojan Women'' ( grc, ΤÏῳάδεÏ, translit=TrÅiades), also translated as ''The Women of Troy'', and also known by its transliterated Greek title ''Troades'', is a tragedy by the Greek playwright Euripides. Produced in 415 BC during ...

''.

["Peace, War and Philosophy" by F. S. Northedge, in Paul Edwards, ''The Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Volume 6, Collier Macmillan, 1967 (pp. 63â67).]

Roman Empire

Several Roman writers rejected the militarism of Roman society and gave voice to anti-war sentiments,

including

Propertius

Sextus Propertius was a Latin elegiac poet of the Augustan age. He was born around 50â45 BC in Assisium and died shortly after 15 BC.

Propertius' surviving work comprises four books of ''Elegies'' ('). He was a friend of the poets Gallus a ...

,

Tibullus

Albius Tibullus ( BC19 BC) was a Latin poet and writer of elegies. His first and second books of poetry are extant; many other texts attributed to him are of questionable origins.

Little is known about the life of Tibullus. There are only a fe ...

and

Ovid

PÅ«blius Ovidius NÄsÅ (; 20 March 43 BC â 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

. The

Stoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism; one whose moral quality is associated with that school of philosophy

*STOIC, a programming language

* ''Stoic'' (film), a 2009 film by Uwe Boll

* ''Stoic'' (mixtape), a 2012 mixtape by rapper T-Pain

*' ...

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

criticised warfare in his book ''

Naturales quaestiones

''Naturales quaestiones'' (''Natural Questions'') is a Latin work of natural philosophy written by Seneca around 65 AD. It is not a systematic encyclopedia like the ''Naturalis Historia'' of Pliny the Elder, though with Pliny's work it represents ...

'' (circa 65 AD).

Maximilian of Tebessa

Saint Maximilian of Tebessa, also known as Maximilian of Numidia, ( la, Maximilianus; AD 274â295) was a Christian saint and martyr, whose feast day is observed on 12 March. Born in AD 274, the son of Fabius Victor, an official connected to the R ...

was a Christian conscientious objector. He was killed for refusing to be conscripted.

Christianity

Throughout history many have understood

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, ×ֵש××Ö¼×¢Ö·, translit=YÄÅ¡Å«aÊ¿, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

of Nazareth to have been a pacifist,

drawing on his

Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount (anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is ...

. In the sermon Jesus stated that one should "not resist an evildoer" and promoted his

turn the other cheek

Turn may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Dance and sports

* Turn (dance and gymnastics), rotation of the body

* Turn (swimming), reversing direction at the end of a pool

* Turn (professional wrestling), a transition between face and heel

* Turn, ...

philosophy. "If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give your cloak as well ... Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you."

The New Testament story is of Jesus, besides preaching these words, surrendering himself freely to an enemy intent on having him killed and proscribing his followers from defending him.

There are those, however, who deny that Jesus was a pacifist

and state that Jesus never said not to fight,

citing examples from the New Testament. One such instance portrays an angry Jesus driving dishonest market

traders from the temple.

A frequently quoted passage is Luke 22:36: "He said to them, 'But now, the one who has a purse must take it, and likewise a bag. And the one who has no sword must

sell his cloak and buy one.'" Pacifists have typically explained that verse as Jesus fulfilling prophecy, since in the next verse, Jesus continues to say: "It is written: 'And he was numbered with the transgressors'; and I tell you that this must be fulfilled in me. Yes, what is written about me is reaching its fulfillment." Others have interpreted the non-pacifist statements in the New Testament to be related to

self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force in ...

or to be metaphorical and state that on no occasion did Jesus shed blood or urge others to shed blood.

Modern history

Beginning in the 16th century, the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

gave rise to a variety of new Christian sects, including the

historic peace churches. Foremost among them were the

Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

(Quakers),

Amish

The Amish (; pdc, Amisch; german: link=no, Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins. They are closely related to Mennonite churches ...

,

Mennonites

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496â1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the Radic ...

,

Hutterites

Hutterites (german: link=no, Hutterer), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptism, Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Refor ...

, and

Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren (german: link=no, Schwarzenauer Neutäufer "Schwarzenau New Baptists") tradition that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germa ...

. The humanist writer

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

was one of the most outspoken pacifists of the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, arguing strongly against warfare in his essays ''

The Praise of Folly

''In Praise of Folly'', also translated as ''The Praise of Folly'' ( la, Stultitiae Laus or ), is an essay written in Latin in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in June 1511. Inspired by previous works of the Italian hum ...

'' (1509) and ''The Complaint of Peace'' (1517).

The Quakers were prominent advocates of pacifism, who as early as 1660 had repudiated violence in all forms and adhered to a strictly pacifist interpretation of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. They stated their beliefs in a declaration to

King Charles II:

"We utterly deny all outward wars and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretense whatever; this is our testimony to the whole world. The Spirit of Christ ... which leads us into all truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world.

Throughout the many 18th century wars in which

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

participated, the Quakers maintained a principled commitment

not to serve in the army and militia or even to pay the alternative £10 fine.

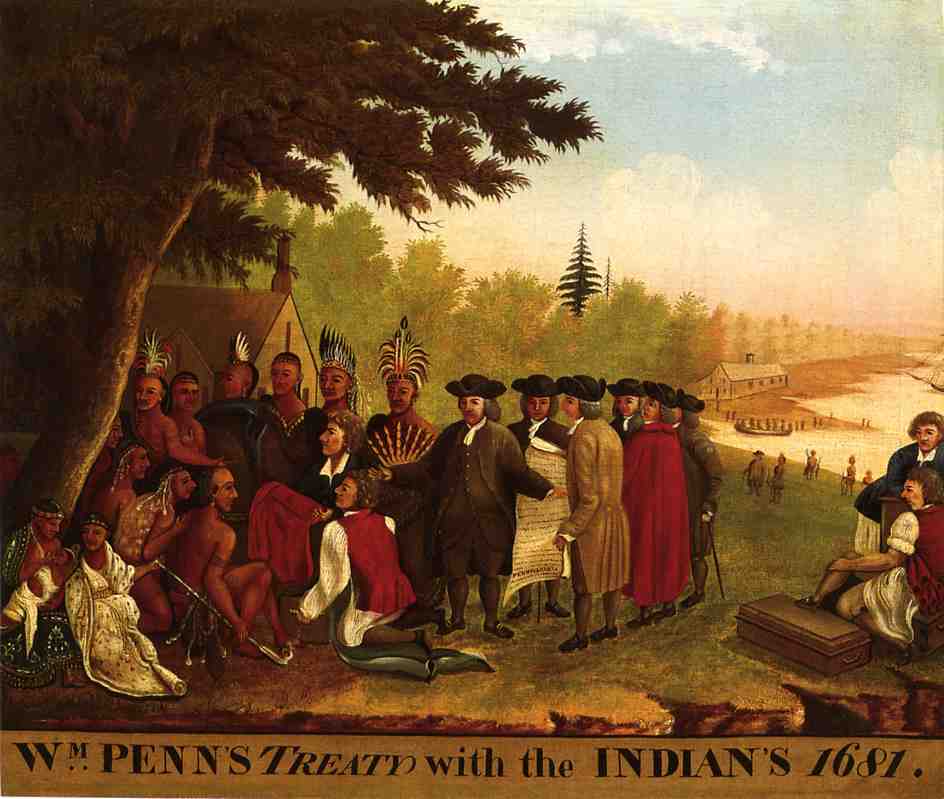

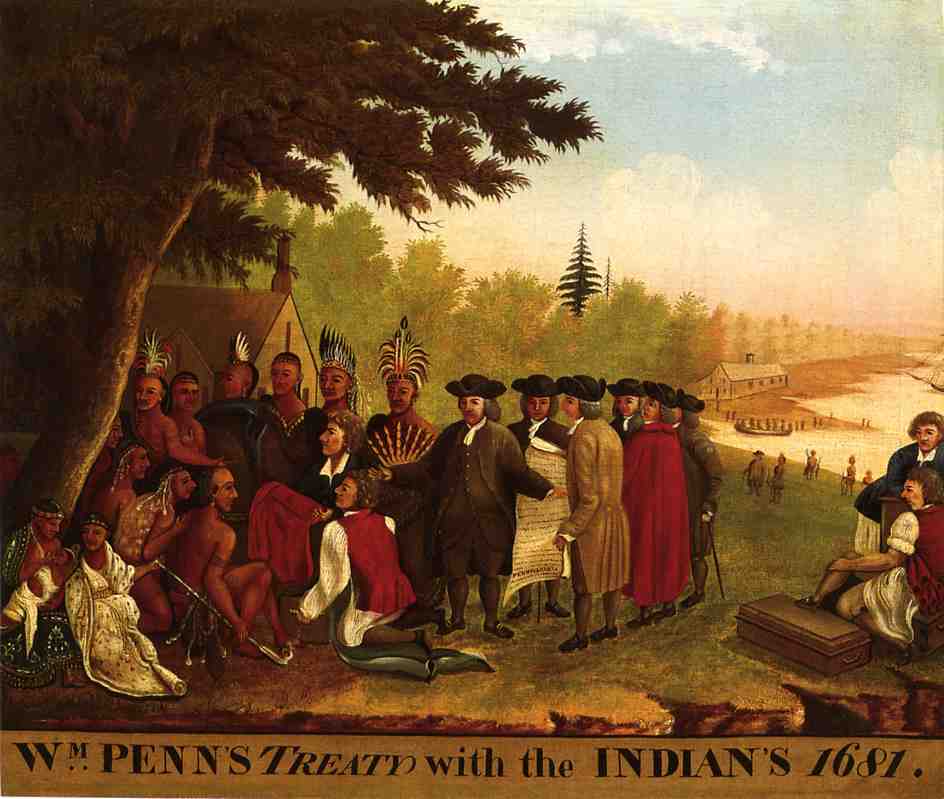

The English Quaker

William Penn

William Penn ( â ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, who founded the

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to W ...

, employed an anti-militarist public policy. Unlike residents of many of the colonies, Quakers chose to trade peacefully with the Indians, including for land. The colonial province was, for the 75 years from 1681 to 1756, essentially unarmed and experienced little or no warfare in that period.

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, a number of thinkers devised plans for an international organisation that would promote peace, and reduce or even eliminate the occurrence of war. These included the French politician

Duc de Sully, the philosophers

Ãmeric Crucé

Ãmeric Crucé (1590â1648) was a French political writer, known for the ''Nouveau Cynée'' (1623), a pioneer work on international relations. He advocated for an international pacific body of representatives of many countries.

Life

Little spec ...

and the

Abbe de Saint-Pierre, and the English Quakers William Penn and

John Bellers

John Bellers (1654 â 8 February 1725) was an England, English educational theorist and Quaker, author of ''Proposals for Raising a College of Industry of All Useful Trades and Husbandry'' (1695).

Life

Bellers was born in London, the son of the ...

.

Pacifist ideals emerged from two strands of thought that coalesced at the end of the 18th century. One, rooted in the secular

Enlightenment, promoted peace as the rational antidote to the world's ills, while the other was a part of the

evangelical religious revival that had played an important part in the campaign for the

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

. Representatives of the former included

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 â 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, in ''Extrait du Projet de Paix Perpetuelle de Monsieur l'Abbe Saint-Pierre'' (1756),

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 â 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

, in his ''Thoughts on Perpetual Peace'', and

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

who proposed the formation of a peace association in 1789. Representative of the latter, was

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

who thought that strict limits should be imposed on British involvement in the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

based on Christian ideals of peace and brotherhood. Bohemian

Bernard Bolzano

Bernard Bolzano (, ; ; ; born Bernardus Placidus Johann Gonzal Nepomuk Bolzano; 5 October 1781 â 18 December 1848) was a Bohemian mathematician, logician, philosopher, theologian and Catholic priest of Italian extraction, also known for his liber ...

taught about the social waste of militarism and the needlessness of war. He urged a total reform of the educational, social, and economic systems that would direct the nation's interests toward peace rather than toward armed conflict between nations.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, pacifism was not entirely frowned upon throughout Europe. It was considered a political stance against costly capitalist-imperialist wars, a notion particularly popular in the

British Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties in the United Kingdom, along with the Conservative Party, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Beginning as an alliance of Whigs, free tradeâsupporting Peelites and reformist Ra ...

of the twentieth century. However, during the eras of World War One and especially World War Two, public opinion on the ideology split. Those against the Second World War, some argued, were not fighting against unnecessary wars of imperialism but instead acquiescing to the fascists of Germany, Italy and Japan.

Peace movements

During the period of the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803â1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, although no formal

peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world peac ...

was established until the end of hostilities, a significant peace movement animated by universalist ideals did emerge, due to the perception of Britain fighting in a

reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

role and the increasingly visible impact of the war on the welfare of the nation in the form of higher taxation levels and high casualty rates. Sixteen peace petitions to

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

were signed by members of the public, anti-war and anti-

Pitt demonstrations convened and peace literature was widely published and disseminated.

The first peace movements appeared in 1815â16. In the United States the first such movement was the

New York Peace Society The New York Peace Society was the first peace society to be established in the United States. It has had several different incarnations, as it has merged into other organizations or dissolved and then been re-created.

First incarnation (1815â18 ...

, founded in 1815 by the theologian

David Low Dodge

David Low Dodge (June 14, 1774April 23, 1852) was an American activist and theologian who helped to establish the New York Peace Society and was a founder of the New York Bible Society and the New York Tract Society. According to historian Dale ...

, and the

Massachusetts Peace Society The Massachusetts Peace Society (1815â1828) was an anti-war organization in Boston, Massachusetts, established to "diffuse light on the subject of war, and to cultivate the principles and spirit of peace." Founding officers included Thomas Dawes, ...

. It became an active organization, holding regular weekly meetings, and producing literature which was spread as far as

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and Malta, describing the horrors of war and advocating pacificism on

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (ΧÏι ...

grounds. The

London Peace Society

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a pioneering British pacifist organisation that was active from 1816 until the 1930s.

Hi ...

(also known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace) was formed in 1816 to promote permanent and universal peace by the

philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

William Allen William Allen may refer to:

Politicians

United States

*William Allen (congressman) (1827â1881), United States Representative from Ohio

*William Allen (governor) (1803â1879), U.S. Representative, Senator, and 31st Governor of Ohio

*William ...

. In the 1840s, British women formed "Olive Leaf Circles", groups of around 15 to 20 women, to discuss and promote pacifist ideas.

The peace movement began to grow in influence by the mid-nineteenth century. The London Peace Society, under the initiative of American consul

Elihu Burritt

Elihu Burritt (December 8, 1810March 6, 1879) was an American diplomat, philanthropist and social activist.Arthur Weinberg and Lila Shaffer Weinberg. ''Instead of Violence: Writings by the Great Advocates of Peace and Nonviolence Throughout Histo ...

and the reverend

Henry Richard

Henry Richard (3 April 1812 â 20 August 1888) was a Congregational minister and Welsh Member of Parliament between 1868â1888. Richard was an advocate of peace and international arbitration, as secretary of the Peace Society for forty year ...

, convened the first

International Peace Congress

International Peace Congress, or International Congress of the Friends of Peace, was the name of a series of international meetings of representatives from peace societies from throughout the world held in various places in Europe from 1843 to 185 ...

in London in 1843. The congress decided on two aims: the ideal of peaceable arbitration in the affairs of nations and the creation of an international institution to achieve that.

Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

became the secretary of the Peace Society in 1850 on a full-time basis, a position which he would keep for the next 40 years, earning himself a reputation as the 'Apostle of Peace'. He helped secure one of the earliest victories for the peace movement by securing a commitment from the

Great Power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

s in the

Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856 brought an end to the Crimean War between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom, the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia.

The treaty, signed on 30 March 1856 at ...

at the end of the

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, in favour of arbitration. On the European continent, wracked by

social upheaval, the first peace congress was held in

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

in 1848 followed by

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

a year later.

After experiencing a recession in support due to the resurgence of militarism during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 â May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, the movement began to spread across Europe and began to infiltrate the new socialist movements. In 1870,

Randal Cremer

Sir William Randal Cremer (18 March 1828 â 22 July 1908) usually known by his middle name "Randal", was a British Liberal Member of Parliament, a pacifist, and a leading advocate for international arbitration. He was awarded the Nobel Peace P ...

formed the

Workman's Peace Association in London. Cremer, alongside the French economist

Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy (20 May 182212 June 1912) was a French economist and pacifist who was a founding member of several peace societies and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also an author and politician, sitting in the Chamber of Deputies fro ...

was also the founding father of the first international organisation for the arbitration of conflicts in 1889, the

Inter-Parliamentary Union

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU; french: Union Interparlementaire, UIP) is an inter-parliamentary institution, international organization of national parliaments. Its primary purpose is to promote democratic governance, accountability, and coop ...

. The

National Peace Council The National Peace Council (NPC), founded in 1908 and disbanded in 2000, acted as the co-ordinating body for almost 200 groups across Britain, with a membership ranging from small village peace groups to national trade unions and local authorities. ...

was founded in after the 17th

Universal Peace Congress

A peace congress, in international relations, has at times been defined in a way that would distinguish it from a peace conference (usually defined as a diplomatic meeting to decide on a peace treaty), as an ambitious forum to carry out dispute re ...

in London (July August 1908).

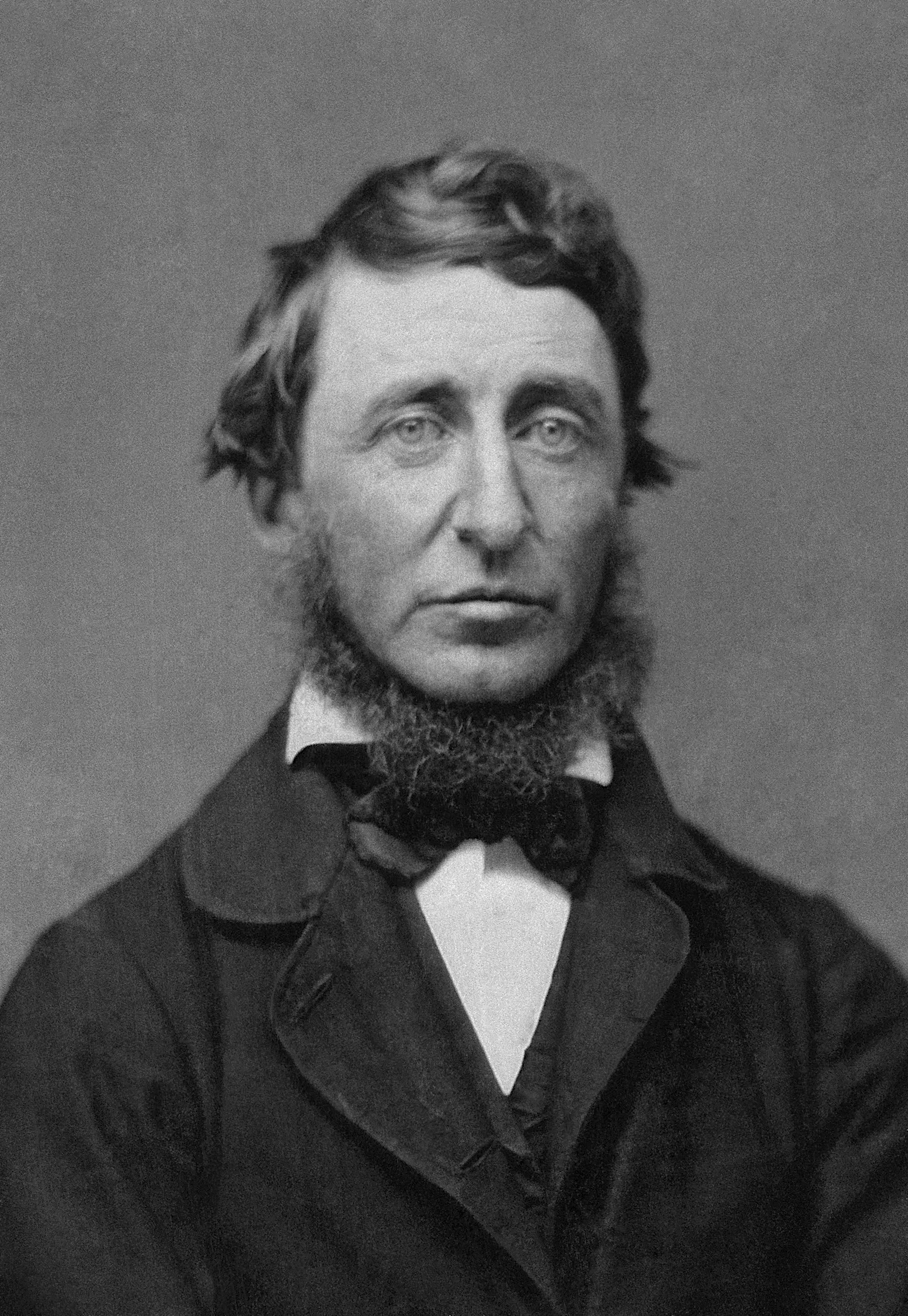

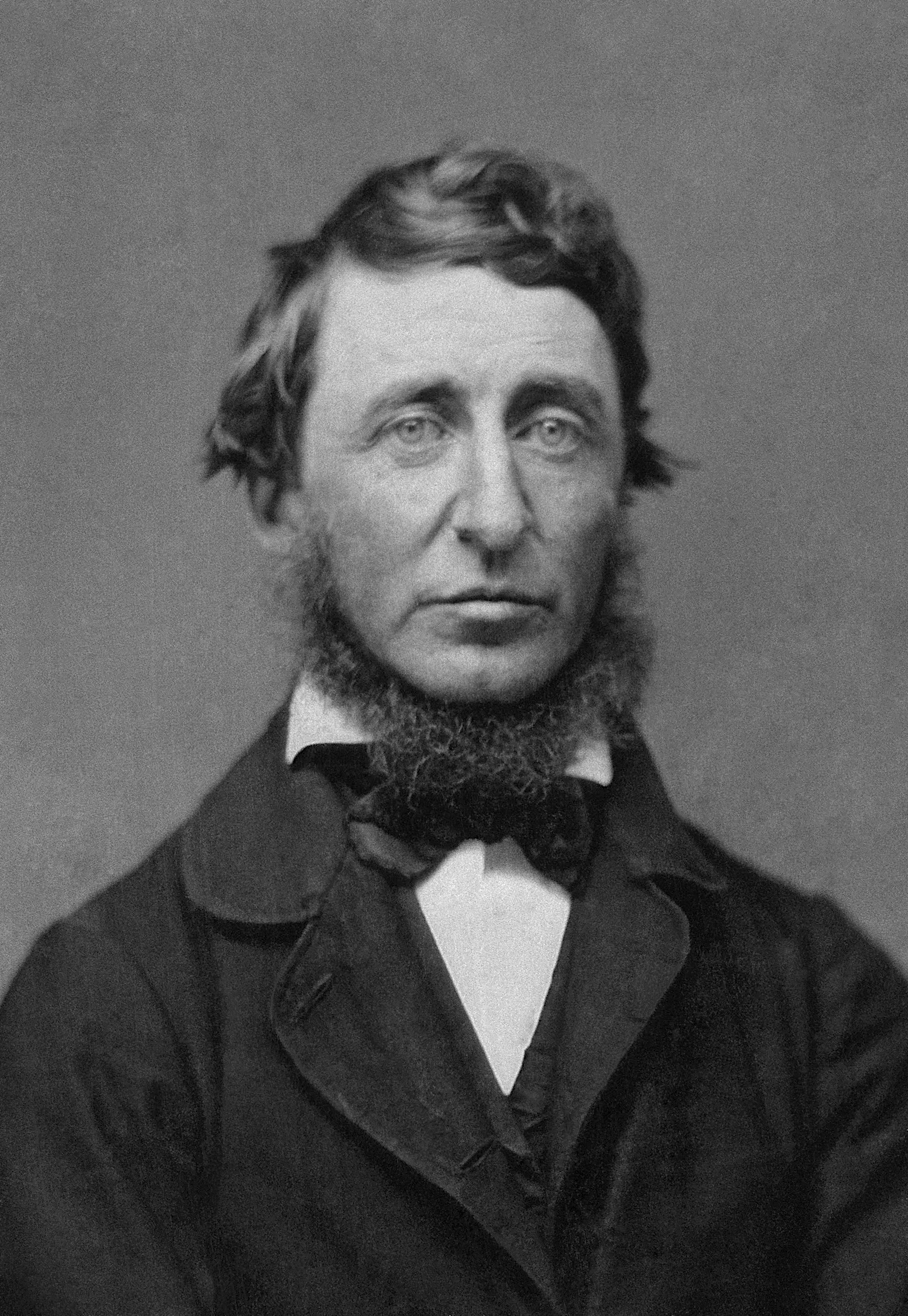

An important thinker who contributed to pacifist ideology was Russian writer

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Ðев ÐÐ¸ÐºÐ¾Ð»Ð°ÐµÐ²Ð¸Ñ Ð¢Ð¾Ð»ÑÑой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. In one of his latter works, ''

The Kingdom of God is Within You

''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, ЦаÑÑÑво Ðожие внÑÑÑи ваÑ, Tsárstvo Bózhiye vnutrà vas) is a non-fiction book written by Leo Tolstoy. A Christian anarchist philosophical treat ...

'', Tolstoy provides a detailed history, account and defense of pacifism. Tolstoy's work inspired a

movement named after him advocating pacifism to arise in Russia and elsewhere. The book was a major early influence on

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 â 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, and the two engaged in regular correspondence while Gandhi was active in South Africa.

Bertha von Suttner

Bertha Sophie Felicitas Freifrau von Suttner (; ; 9 June 184321 June 1914) was an Austrian-Bohemian pacifist and novelist. In 1905, she became the second female Nobel laureate (after Marie Curie in 1903), the first woman to be awarded the Nobel ...

, the first woman to be a

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

laureate, became a leading figure in the peace movement with the publication of her novel, ''Die Waffen nieder!'' ("Lay Down Your Arms!") in 1889 and founded an Austrian pacifist organization in 1891.

Non-violent resistance

In

colonial New Zealand

The Colony of New Zealand was a Crown colony of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that encompassed the islands of New Zealand from 1841 to 1907. The power of the British government was vested in the Governor of New Zealand, as th ...

, during the latter half of the 19th century

PÄkehÄ settlers

PÄkehÄ settlers were European emigrants who journeyed to New Zealand, and especially to the Auckland, Wellington, Hawkes Bay, Canterbury and Otago regions during the 19th century. The ethnic and occupational social composition of these New Zea ...

used numerous tactics to confiscate land from the indigenous

MÄori

MÄori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the MÄori people

* MÄori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* MÄori language, the language of the MÄori people of New Zealand

* MÄori culture

* Cook Islanders, the MÄori people of the C ...

, including

warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

. In the 1870s and 1880s,

Parihaka

Parihaka is a community in the Taranaki region of New Zealand, located between Mount Taranaki and the Tasman Sea. In the 1870s and 1880s the settlement, then reputed to be the largest MÄori village in New Zealand, became the centre of a major camp ...

, then reported to be the largest MÄori settlement in New Zealand, became the centre of a major campaign of non-violent resistance to land confiscations. One MÄori leader,

Te Whiti-o-Rongomai, quickly became the leading figure in the movement, stating in a speech that "Though some, in darkness of heart, seeing their land ravished, might wish to take arms and kill the aggressors, I say it must not be. Let not the Pakehas think to succeed by reason of their guns... I want not war". Te Whiti-o-Rongomai achieved renown for his non-violent tactics among the MÄori, which proved more successful in preventing land confiscations than acts of violent resistance.

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 â 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

was a major political and spiritual leader of India, instrumental in the

Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

. The Nobel prize winning great poet

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবà§à¦¨à§à¦¦à§à¦°à¦¨à¦¾à¦¥ ঠাà¦à§à¦°; 7 May 1861 â 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

, who was also an Indian, gave him the honorific "

Mahatma

Mahatma (English pronunciation: , sa, महातà¥à¤®à¤¾, translit=mahÄtmÄ) is an honorific used in India.

The term is commonly used for Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who is often referred to simply as "Mahatma Gandhi". Albeit less frequent ...

", usually translated "Great Soul". He was the pioneer of a brand of nonviolence (or ''

ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiá¹sÄ'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India â ...

'') which he called ''

satyagraha

Satyagraha ( sa, सतà¥à¤¯à¤¾à¤à¥à¤°à¤¹; ''satya'': "truth", ''Ägraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone w ...

''translated literally as "truth force". This was the resistance of tyranny through civil disobedience that was not only nonviolent but also sought to change the heart of the opponent. He contrasted this with ''duragraha'', "resistant force", which sought only to change behaviour with stubborn protest. During his 30 years of work (1917â1947) for the independence of his country from

British colonial rule

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, Gandhi led dozens of nonviolent campaigns, spent over seven years in prison, and

fasted nearly to the death on several occasions to obtain British compliance with a demand or to stop inter-communal violence. His efforts helped lead India to independence in 1947, and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom worldwide.

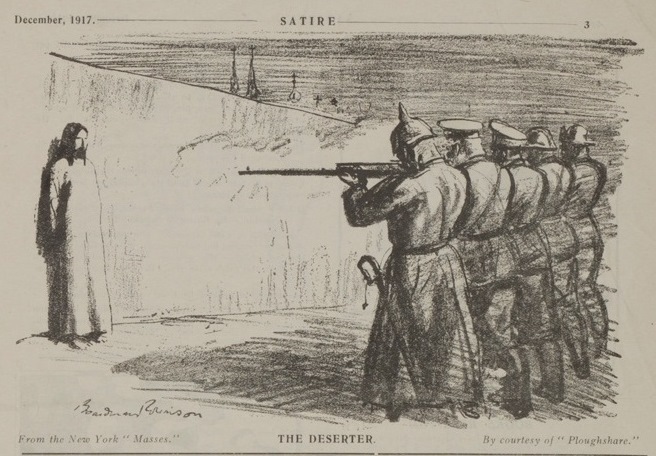

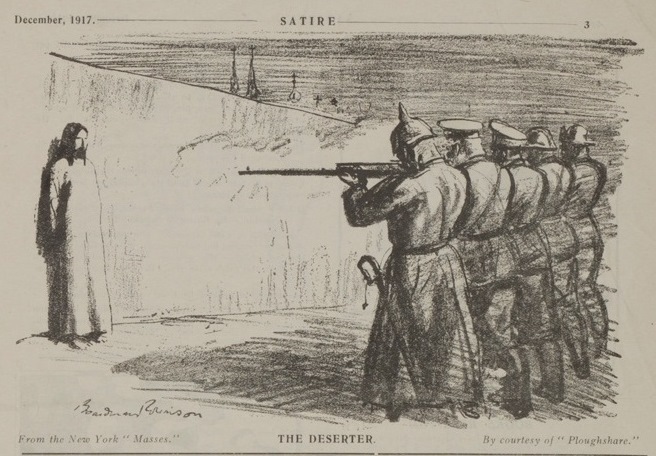

World War I

Peace movements became active in the Western world after 1900, often focusing on treaties that would settle disputes through arbitration, and efforts to support the Hague conventions.

The sudden outbreak of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in July 1914 dismayed the peace movement. Socialist parties in every industrial nation had committed themselves to antiwar policies, but when the war came, all of them, except in Russia and the United States, supported their own governments. There were highly publicized dissidents, some of whom were imprisoned for opposing draft laws, such as

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

in the U.S. In Britain, the prominent activist

Stephen Henry Hobhouse

Stephen Henry Hobhouse (5 August 1881 – 2 April 1961) was a prominent English peace activist, prison reformer, and religious writer.

Family

Stephen Henry Hobhouse was born in Pitcombe, Somerset, England. He was the eldest son of Henry Hob ...

was jailed for refusing military service, citing his convictions as a "socialist and a Christian". Many

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

groups and movements were

antimilitarist

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especi ...

, arguing that war by its nature was a type of governmental coercion of the

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

for the benefit of

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

elites. The French socialist pacifist leader

Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social demo ...

was assassinated by a nationalist fanatic on July 31, 1914. The national parties in the

Second International

The Second International (1889â1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

increasingly supported their respective nations in war, and the International was dissolved in 1916.

In 1915, the

League of Nations Society The League of Nations Society was a political group devoted to campaigning for an international organisation of nations, with the aim of preventing war.

The society was founded in 1915 by Baron Courtney and Willoughby Dickinson, both members of t ...

was formed by British

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

leaders to promote a strong international organisation that could enforce the peaceful resolution of conflict. Later that year, the

League to Enforce Peace

The League to Enforce Peace was a non-state American organization established in 1915 to promote the formation of an international body for world peace. It was formed at Independence Hall in Philadelphia by American citizens concerned by the outbr ...

was established in the U.S. to promote similar goals.

Hamilton Holt

Hamilton Holt (August 18, 1872 â April 26, 1951) was an American educator, editor, author and politician.

Biography

Holt was born on August 18, 1872 in Brooklyn, New York City to George Chandler Holt and his wife Mary Louisa Bowen Holt. His fat ...

published a September 28, 1914, editorial in his magazine the ''Independent'' called "The Way to Disarm: A Practical Proposal" that called for an international organization to agree upon the arbitration of disputes and to guarantee the territorial integrity of its members by maintaining military forces sufficient to defeat those of any non-member. The ensuing debate among prominent internationalists modified Holt's plan to align it more closely with proposals offered in Great Britain by

Viscount James Bryce, a former British ambassador to the United States. These and other initiatives were pivotal in the change in attitudes that gave birth to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

after the war.

In addition to the traditional peace churches, some of the many groups that protested against the war were the

Woman's Peace Party

The Woman's Peace Party (WPP) was an American pacifist and feminist organization formally established in January 1915 in response to World War I. The organization is remembered as the first American peace organization to make use of direct action ...

(which was organized in 1915 and led by noted reformer

Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

), the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace (ICWPP) (also organized in 1915), the

American Union Against Militarism

The American Union Against Militarism (AUAM) was an American pacifist organization established in response to World War I. The organization attempted to keep the United States out of the European conflict through mass demonstrations, public lectur ...

, the

Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR).

...

and the

American Friends Service Committee

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Religious Society of Friends (''Quaker'') founded organization working for peace and social justice in the United States and around the world. AFSC was founded in 1917 as a combined effort by Am ...

.

Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 â May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States in 1917. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representat ...

, the first woman elected to Congress, was another fierce advocate of pacifism, the only person to vote against American entrance into both wars.

Between the two World Wars

After the immense loss of nearly ten million men to

trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. Trench warfare became a ...

, a sweeping change of attitude toward

militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

crashed over Europe, particularly in nations such as Great Britain, where many questioned its involvement in the war. After World War I's official end in 1918, peace movements across the continent and the United States renewed, gradually gaining popularity among young Europeans who grew up in the shadow of Europe's trauma over the Great War. Organizations formed in this period included the

War Resisters' International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 30 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 unde ...

, the

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

, the

No More War Movement The No More War Movement was the name of two pacifist organisations, one in the United Kingdom

and one in New Zealand.

British Group

The British No More War Movement (NMWM) was founded in 1921 as a pacifist and socialist successor to the No-Consc ...

, the

Service Civil International

Service Civil International (SCI) is an international peace organisation. Since 1920, it organises international volunteering projects in the form of workcamps and it was the first organisation worldwide to do so. The organisation was founded by S ...

and the

Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

(PPU). The

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

also convened several disarmament conferences in the interbellum period such as the

Geneva Conference, though the support that pacifist policy and idealism received varied across European nations. These organizations and movements attracted tens of thousands of Europeans, spanning most professions including "scientists, artists, musicians, politicians, clerks, students, activists and thinkers."

= Great Britain

=

Pacifism and revulsion with war were very popular sentiments in 1920s Britain. Novels and poems on the theme of the futility of war and the slaughter of the youth by old fools were published, including,

Death of a Hero

''Death of a Hero'' is a World War I novel by Richard Aldington. It was his first novel, published by Chatto & Windus in 1929, and thought to be partly autobiographical.

Plot summary

''Death of a Hero'' is the story of a young English artist na ...

by

Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington (8 July 1892 â 27 July 1962), born Edward Godfree Aldington, was an English writer and poet, and an early associate of the Imagist movement. He was married to the poet Hilda Doolittle (H. D.) from 1911 to 1938. His 50-year w ...

,

Erich Remarque's translated

All Quiet on the Western Front

''All Quiet on the Western Front'' (german: Im Westen nichts Neues, lit=Nothing New in the West) is a novel by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. The book describes the German soldiers' extreme physical and mental trauma du ...

and

Beverley Nichols

John Beverley Nichols (9 September 1898 â 15 September 1983) was an English writer, playwright and public speaker. He wrote more than 60 books and plays.

Career

Between his first book, the novel, ''Prelude'' (1920) and his last, a book of po ...

's expose ''Cry Havoc''. A debate at the

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019â20)

, chancellor ...

in 1933 on the motion 'one must fight for King and country' captured the changed mood when the motion was resoundingly defeated.

Dick Sheppard established the

Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

in 1934, which totally renounced war and aggression. The idea of collective security was also popular; instead of outright pacifism, the public generally exhibited a determination to stand up to aggression, but preferably with the use of economic sanctions and multilateral negotiations. Many members of the Peace Pledge Union later joined the

Bruderhof during its period of residence in the Cotswolds, where Englishmen and Germans, many of whom were Jewish, lived side by side despite local persecution.

The British

Labour Party had a strong pacifist wing in the early 1930s, and between 1931 and 1935 it was led by

George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 â 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929â31, he spent ...

, a Christian pacifist who later chaired the No More War Movement and was president of the PPU. The 1933 annual conference resolved unanimously to "pledge itself to take no part in war". Researcher Richard Toye writes that "Labour's official position, however, although based on the aspiration towards a world socialist commonwealth and the outlawing of war, did not imply a renunciation of force under all circumstances, but rather support for the ill-defined concept of 'collective security' under the League of Nations. At the same time, on the party's left,

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 â 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

's small but vocal

Socialist League opposed the official policy, on the non-pacifist ground that the League of Nations was 'nothing but the tool of the satiated imperialist powers'."

Lansbury was eventually persuaded to resign as Labour leader by the non-pacifist wing of the party and was replaced by

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

. As the threat from

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

increased in the 1930s, the Labour Party abandoned its pacifist position and supported rearmament, largely as the result of the efforts of

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 â 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922â19 ...

and

Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 â 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1 ...

, who by 1937 had also persuaded the party to oppose

Neville Chamberlain