Libertarian Women on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarcha-feminism, also referred to as anarchist feminism, is a system of analysis which combines the principles and power analysis of

In Argentina,

In Argentina,

An important topic within

An important topic within  The most important American free love journal was ''

The most important American free love journal was '' Brazilian

Brazilian

Although hostile to

Although hostile to  Goldman was also an outspoken critic of

Goldman was also an outspoken critic of

Witkop, Milly

in ''Datenbank des deutschsprachigen Anarchismus''. Retrieved October 8, 2007. After its founding in early 1919, a discussion about the role of girls and women in the union started. The male-dominated organization had at first ignored gender issues, but soon women started founding their own unions, which were organized parallel to the regular unions, but still formed part of the FAUD. Witkop was one of the leading founders of the Women's Union in Berlin in 1920. On 15 October 1921, the women's unions held a national congress in

The organization also produced propaganda through radio, traveling libraries and propaganda tours in order to promote their cause. Organizers and activists traveled through rural parts of Spain to set up rural collectives and support for women. To prepare women for leadership roles in the anarchist movement, they organized schools, women-only social groups and a women-only newspaper to help women gain

The organization also produced propaganda through radio, traveling libraries and propaganda tours in order to promote their cause. Organizers and activists traveled through rural parts of Spain to set up rural collectives and support for women. To prepare women for leadership roles in the anarchist movement, they organized schools, women-only social groups and a women-only newspaper to help women gain

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

A prominent example for this gives the founding of the in 1973: "We simply skipped the step of a theoretical platform, which was a must in other groups. Even before this meeting there was a consensus, so that we didn't need a lot of discussion, because all of us had the same experience with left-wing groups behind us."

A prominent example for this gives the founding of the in 1973: "We simply skipped the step of a theoretical platform, which was a must in other groups. Even before this meeting there was a consensus, so that we didn't need a lot of discussion, because all of us had the same experience with left-wing groups behind us."

In the West Berlin anarchist newspaper '' Agit 883'', a Women's Liberation Front proclaimed in 1969 combatively that "it will raise silently out of the darkness, strike and disappear again and criticized the women who "brag about jumping onto a party express without realizing that the old jalopy has to be electrified first before it can drive. They've chosen security over the struggle".

Many women joined the

In the West Berlin anarchist newspaper '' Agit 883'', a Women's Liberation Front proclaimed in 1969 combatively that "it will raise silently out of the darkness, strike and disappear again and criticized the women who "brag about jumping onto a party express without realizing that the old jalopy has to be electrified first before it can drive. They've chosen security over the struggle".

Many women joined the

Anarcha-feminists have been active in protesting and

Anarcha-feminists have been active in protesting and

Anarcha-Communist Gender news

anarcha-feminist articles at The anarchist library

Anarcha

Libertarian Communist Library Archive

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anarcha-Feminism Anarcha-feminism, Anarchist theory Feminism and social class Feminist theory

anarchist theory

Anarchism is the political philosophy which holds ruling classes and the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." ''The Concise Oxford Dictio ...

with feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

. Anarcha-feminism closely resembles intersectional feminism

Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how aspects of a person's social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality identifies multiple factors of adva ...

. Anarcha-feminism generally posits that patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males a ...

and traditional gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cent ...

s as manifestations of involuntary coercive

Coercion () is compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner by the use of threats, including threats to use force against a party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desi ...

hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

should be replaced by decentralized

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group.

Conce ...

free association. Anarcha-feminists believe that the struggle against patriarchy is an essential part of class conflict

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

and the anarchist struggle against the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

and capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

. In essence, the philosophy sees anarchist struggle as a necessary component of feminist struggle and vice versa. L. Susan Brown

''The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism, and Anarchism'' is a 1993 political science book by L. Susan Brown. She begins by noting that liberalism and anarchism seem at times to share common components, but on other occasions ...

claims that "as anarchism is a political philosophy that opposes all relationships of power, it is inherently feminist".

Anarcha-feminism is an anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as "a form of social organisation characterised by submission to authority", "favoring complete obedience or subjection to authority as opposed to individual freedom" and ...

, anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economi ...

, anti-oppressive philosophy, with the goal of creating an "equal ground" between all genders. Anarcha-feminism suggests the social freedom and liberty of women without needed dependence upon other groups or parties.

Origins

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

opposed patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males a ...

and the way the law " ubjected womento the absolute domination of the man". He argued that " ual rights must belong to men and women" so that women could "become independent and be free to forge their own way of life". Bakunin foresaw the end of "the authoritarian juridicial family" and "the full sexual freedom of women". On the other hand, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

viewed the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

as the most basic unit of society and of his morality and believed that women had the responsibility of fulfilling a traditional role within the family.Broude, N. and M. Garrard (1992). ''The Expanding Discourse: Feminism And Art History''. Westview Press. p. 303.

Since the 1860s, anarchism's radical critique of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

and the state has been combined with a critique of patriarchy. Anarcha-feminists thus start from the precept that modern society is dominated by men. Authoritarian traits and values—domination, exploitation, aggression and competition—are integral to hierarchical

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

civilizations and are seen as "masculine". In contrast, non-authoritarian traits and values—cooperation, sharing, compassion and sensitivity—are regarded as "feminine" and devalued. Anarcha-feminists have thus espoused creation of a non-authoritarian, anarchist society. They refer to the creation of a society based on cooperation

Cooperation (written as co-operation in British English) is the process of groups of organisms working or acting together for common, mutual, or some underlying benefit, as opposed to working in competition for selfish benefit. Many animal a ...

, sharing and mutual aid as the "feminization

Feminization most commonly refers to:

* Feminization (biology), the hormonally induced development of female sexual characteristics

* Feminization (activity), a sexual or lifestyle practice where a person assumes a female role

* Feminization (soci ...

of society".

In its early stages of development, anarchists saw anarcha-feminism and women's struggle as second to liberating the working class. They also considered the movement flawed because they believed the feminist movement of the time did not include the class struggle. Early anarchists perceived the feminist movement to only include the privileged. Therefore, the early anarcha-feminist movement focused on change without taking away from class liberation. The movement recognized that women needed their own movement that addressed their specific needs. The movement was also rooted in the belief that education would be the key to empowering women and raising awareness among women.

Anarcha-feminism began with late 19th and early 20th century authors and theorists such as anarchist feminists Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage and the State (polity), state as well as the domination of religion over sexuality ...

and Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriag ...

. In the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, an anarcha-feminist group, ("Free Women"), linked to the , organized to defend both anarchist and feminist ideas. According to author Robert Kern, the Spanish anarchist Federica Montseny

Frederica Montseny i Mañé (; 1905–1994) was a Catalan Anarchism, anarchist and intellectual who served as Ministry of Health (Spain), Minister of Health and Social Assistance in the Government of the Second Spanish Republic, Spanish Republi ...

held that the "emancipation of women would lead to a quicker realization of the social revolution" and that "the revolution against sexism would have to come from intellectual and militant 'future-women'. According to this Nietzschean concept ... women could realize through art and literature the need to revise their own roles". In China, the anarcha-feminist He Zhen argued that without women's liberation society could not be liberated.

Opposition to traditional concepts of family

An important aspect of anarcha-feminism is its opposition to traditional concepts of family, education andgender roles

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cent ...

. The institution of marriage is one of the most widely opposed. De Cleyre argued that marriage stifled individual growth and Goldman argued that it "is primarily an economic arrangement ... oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of t ...

pays for it with her name, her privacy, her self-respect, her very life". Anarcha-feminists have also argued for non-hierarchical family and educational structures and had a prominent role in the creation of the Modern School in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, based on the ideas of Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia (; January 14, 1859 – October 13, 1909), widely known as Francisco Ferrer (), was a Spanish radical freethinker, anarchist, and educationist behind a network of secular, private, libertarian schools in and aroun ...

.

Virginia Bolten and ''La Voz de la Mujer''

In Argentina,

In Argentina, Virginia Bolten

Virginia Bolten (26 December 1870 – 1960) was an Argentine journalist as well as an anarchist and feminist activist of German descent. A gifted orator, she is considered as a pioneer in the struggle for women's rights in Argentina. She was de ...

is responsible for the publication of a newspaper called ' ('' en, The Woman's Voice''), which was published nine times in Rosario between 8 January 1896 and 1 January 1897 and was briefly revived in 1901. A similar paper with the same name was reportedly published later in Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, which suggests that Bolten may also have founded and edited it after her deportation.

''La Voz de la Mujer'' described itself as "dedicated to the advancement of Communist Anarchism". Its central theme was the multiple natures of women's oppression. An editorial asserted: "We believe that in present-day society, nothing and nobody has a more wretched situation than unfortunate women." They said that women were doubly oppressed by both bourgeois society and men. Its beliefs can be seen from its attack on marriage and upon male power over women. Its contributors, like anarchist feminists elsewhere, developed a concept of oppression that focused on gender. They saw marriage as a bourgeois institution which restricted women's freedom, including their sexual freedom. Marriages entered into without love, fidelity maintained through fear rather than desire and oppression of women by men they hated were all seen as symptomatic of the coercion implied by the marriage contract. It was this alienation of the individual's will that the anarchist feminists deplored and sought to remedy, initially through free love and then more thoroughly through social revolution.

Individualist anarchism and the free love movement

An important topic within

An important topic within individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

is free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

and to experimental communities, which viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

since most sexual laws discriminated against women, such as marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.

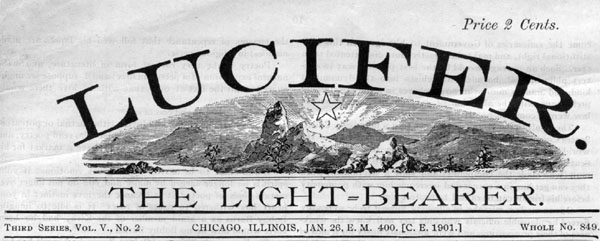

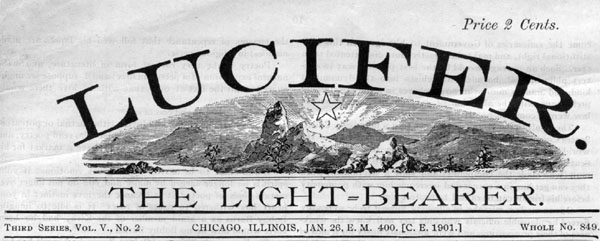

The most important American free love journal was ''

The most important American free love journal was ''Lucifer the Lightbearer

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

'' (1883–1907), edited by Moses Harman

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

and Lois Waisbrooker

Lois Waisbrooker (21 February 1826 – 3 October 1909) was an American feminist author, editor, publisher, and campaigner of the later nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. She wrote extensively on issues of sex, marriage, birth contr ...

. Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρας ...

and Angela Heywood

Angela Fiducia Heywood (1840–1935) was a radical writer and activist, known as a free love advocate, suffragist, socialist, spiritualist, labor reformer, and abolitionist.

Early life

Angela Heywood was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire, arou ...

's '' The Word'' was also published from 1872 to 1890 and in 1892–1893. M. E. Lazarus

Marx Edgeworth Lazarus (February 6, 18221896) was an American individualist anarchist, Fourierist, and free-thinker. Lazarus was a practicing doctor of homeopathy who also wrote a number of books and articles, some under the pseudonym "Edgeworth". ...

was also an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love. In Europe, the main propagandist of free love within individualist anarchism was Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, ...

. He proposed the concept of "'" to speak of free love as the possibility of voluntary sexual encounter between consenting adults. He was also a consistent proponent of polyamory

Polyamory () is the practice of, or desire for, romantic relationships with more than one partner at the same time, with the informed consent of all partners involved. People who identify as polyamorous may believe in open relationships wit ...

. In France, there was also feminist activity inside French individualist anarchism as promoted by individualist feminists Marie Küge, Anna Mahé, Rirette Maîtrejean

Rirette Maîtrejean was the pseudonym of Anna Estorges (born 14 August 1887; died 11 June 1968). She was a French people, French individualist anarchism, individualist anarchist born in TulleRichard Parry. ''The Bonnot Gang: The Story of the Frenc ...

and Sophia Zaïkovska.

Brazilian

Brazilian individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

Maria Lacerda de Moura

Maria Lacerda de Moura (Manhuaçu, 16 May 1887 - Rio de Janeiro, 20 March 1945) was a Brazilian teacher, writer and anarcha-feminism, anarcha-feminist. The daughter of spiritism, spiritist and anti-clericalism, anti-clerical parents, she grew up ...

lectured on topics such as education, women's rights, free love and antimilitarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especia ...

. Her writings and essays landed her attention not only in Brazil, but also in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

and Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

. In February 1923, she launched ', a periodical linked with the anarchist, progressive and freethinking

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

circles of the period. Her thought was mainly influenced by individualist anarchists such as Han Ryner

Jacques Élie Henri Ambroise Ner (7 December 1861 – 6 February 1938), also known by the pseudonym Han Ryner, was a French individualist anarchist philosopher and activist and a novelist. He wrote for publications such as ''L'Art social ...

and Émile Armand.

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage and the State (polity), state as well as the domination of religion over sexuality ...

was an American anarchist

Anarchism in the United States began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and c ...

and feminist who Emma Goldman once called the country's most talented anarchist woman. She was a prolific writer and speaker, opposing domination of the state, men, marriage, and religion in sexuality and women's lives. She began her activist career in the freethought movement and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

, she evolved through mutualism to an anarchism without adjectives

Anarchism without adjectives (from the Spanish language, Spanish '), in the words of historian George Richard Esenwein, "referred to an hyphen, unhyphenated form of anarchism, that is, a doctrine without any qualifying labels such as Anarchist com ...

. In her 1895 lecture entitled ''Sex Slavery,'' de Cleyre condemns ideals of beauty that encourage women to distort their bodies and child socialization practices that create unnatural gender roles. The title of the essay refers not to traffic in women for purposes of prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

, although that is also mentioned, but rather to marriage laws that allow men to rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

their wives without consequences. Such laws make "every married woman what she is, a bonded slave, who takes her master's name, her master's bread, her master's commands, and serves her master's passions".

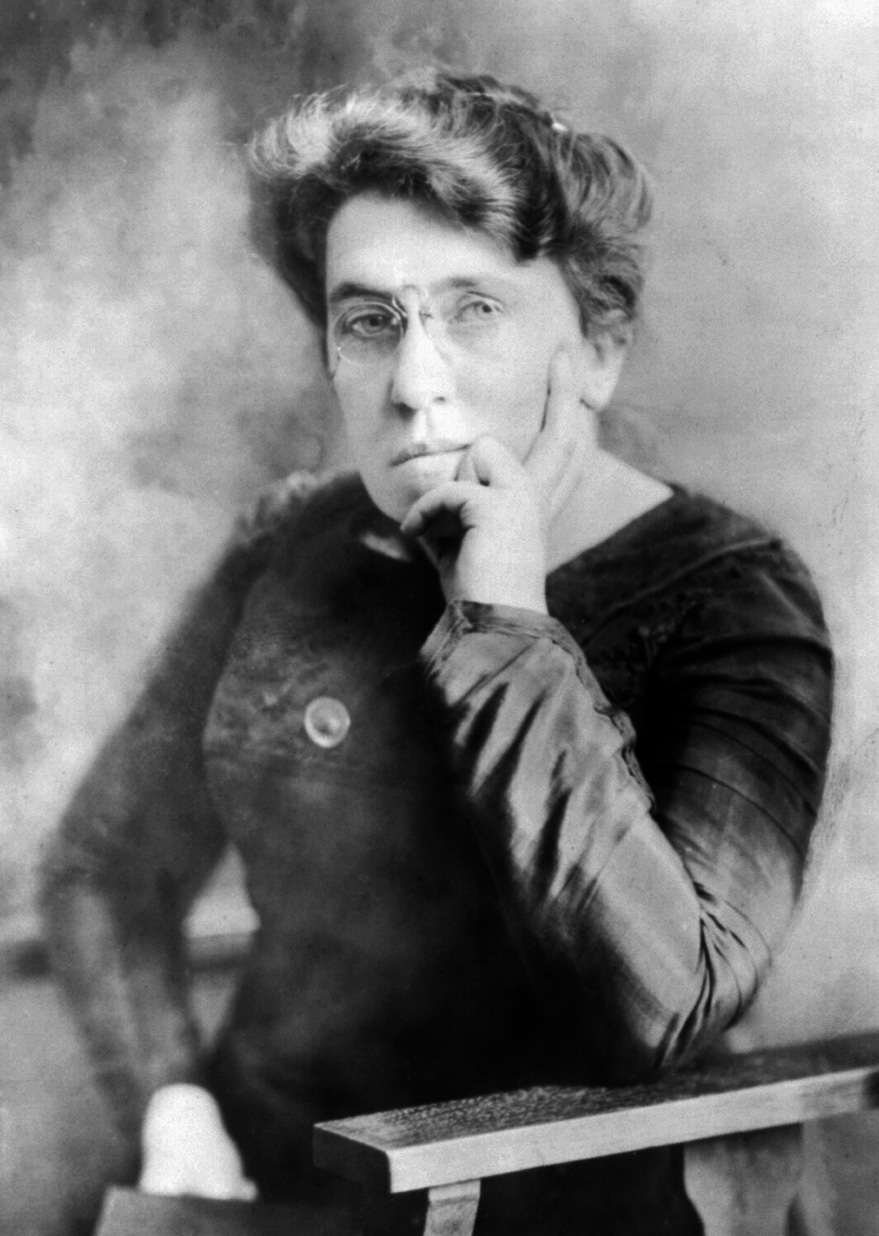

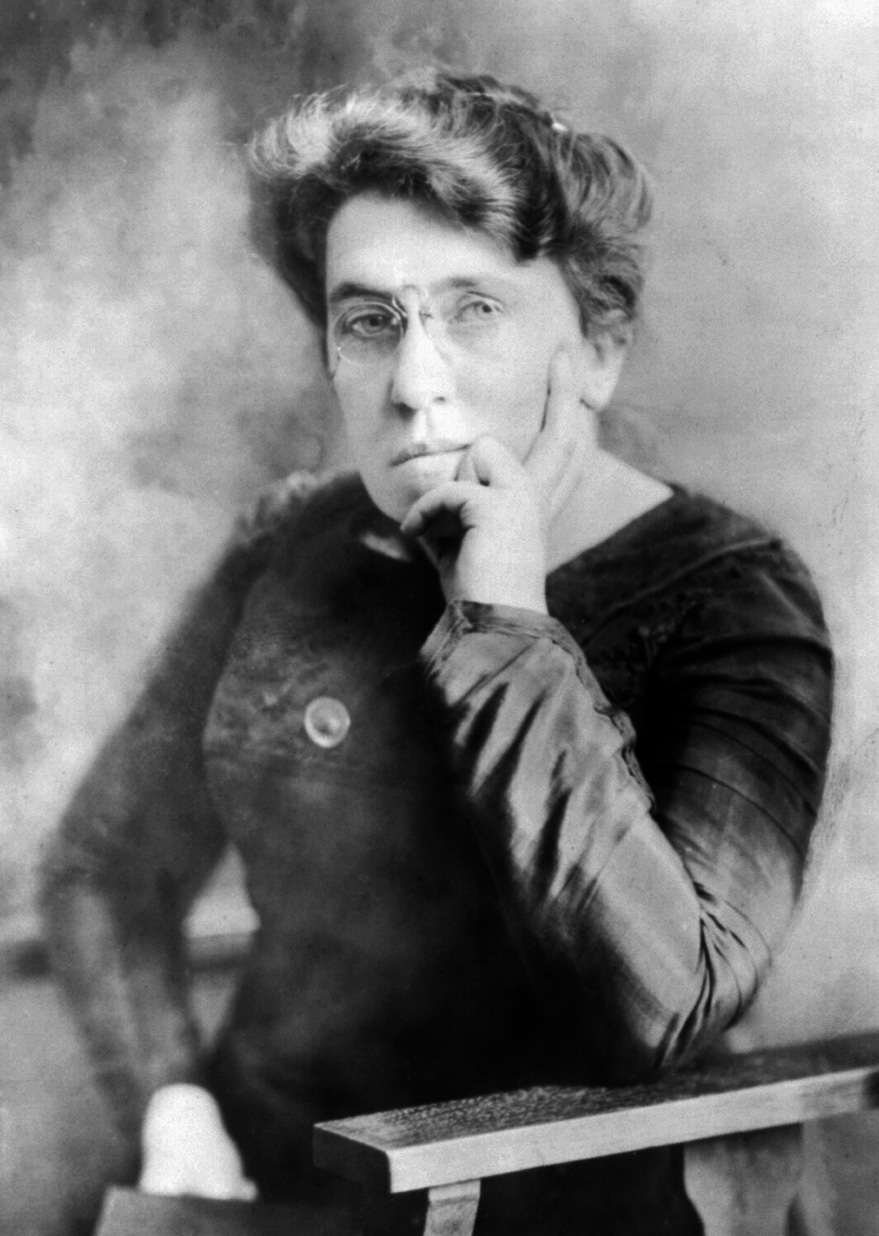

Emma Goldman

Although hostile to

Although hostile to first-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used s ...

and its suffragist goals, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

advocated passionately for the rights of women and is today heralded as a founder of anarcha-feminism. In 1897, she wrote: "I demand the independence of woman, her right to support herself; to live for herself; to love whomever she pleases, or as many as she pleases. I demand freedom for both sexes, freedom of action, freedom in love and freedom in motherhood." In 1906, Goldman wrote a piece entitled "The Tragedy of Woman's Emancipation" in which she argued that traditional suffragists and first-wave feminists were achieving only a superficial good for women by pursuing the vote and a movement from the home sphere. She also writes that in the ideal world women would be free to pursue their own destinies, yet "emancipation of woman, as interpreted and practically applied today, has failed to reach that great end". She pointed to the "so-called independence" of the modern woman whose true nature—her love and mother instincts—were rebuked and stifled by the suffragist and early feminist movements. Goldman's arguments in this text are arguably much more in line with the ideals of modern third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism is an iteration of the feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, prominent in the decades prior to the fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second wave, Gen X and early Gen Y generations third-wav ...

than with the feminism of her time, especially given her emphasis on allowing women to pursue marriage and motherhood if they so desired. In Goldman's eyes, the early twentieth century idea of the emancipated woman had a "tragic effect upon the inner life of woman" by restricting her from fully fulfilling her nature and having a well-rounded life with a companion in marriage.

A nurse by training, Goldman was an early advocate for educating women about birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

. Like many contemporary feminists, she saw abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

as a tragic consequence of social conditions and birth control as a positive alternative. Goldman was also an advocate of free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

and a strong critic of marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

. She saw early feminists as confined in their scope and bounded by social forces of Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

and capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

. She wrote: "We are in need of unhampered growth out of old traditions and habits. The movement for women's emancipation has so far made but the first step in that direction." When Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

, an advocate of access to birth control, coined the term "birth control" and disseminated information about various methods in the June 1914 issue of her magazine ''The Woman Rebel'', she received aggressive support from Goldman. Sanger was arrested in August under the Comstock laws

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of ...

, which prohibited the dissemination of "obscene, lewd, or lascivious articles", including information relating to birth control. Although they later split from Sanger over charges of insufficient support, Goldman and Reitman distributed copies of Sanger's pamphlet ''Family Limitation'' (along with a similar essay of Reitman's). In 1915, Goldman conducted a nationwide speaking tour in part to raise awareness about contraception options. Although the nation's attitude toward the topic seemed to be liberalizing, Goldman was arrested in February 1916 and charged with violation of the Comstock Law. Refusing to pay a $100 fine, she spent two weeks in a prison workhouse, which she saw as an "opportunity" to reconnect with those rejected by society.

homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitude (psychology), attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, h ...

and prejudice against homosexuals. Her belief that social liberation should extend to gay men and lesbians was virtually unheard of at the time, even among anarchists. As Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician and sexologist.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy, philology and medicine. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Com ...

wrote, "she was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public".Goldman, Emma (1923). "Offener Brief an den Herausgeber der Jahrbücher über Louise Michel" with a preface by Magnus Hirschfeld. ''Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen

The (''Yearbook for Intermediate Sexual Types'') was an annual publication of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (german: Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK), an early LGBT rights organization founded by German sexologist Magnus Hirs ...

'' 23: 70. Translated from German by James Steakley. Goldman's original letter in English is not known to be extant. In numerous speeches and letters, she defended the right of gay men and lesbians to love as they pleased and condemned the fear and stigma associated with homosexuality. As Goldman wrote in a letter to Hirschfeld: "It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of a different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding for homosexuals and is so crassly indifferent to the various gradations and variations of gender and their great significance in life."

Milly Witkop

Milly Witkop

Milly Witkop(-Rocker) (March 3, 1877November 23, 1955) was a Ukrainian-born Jewish anarcho-syndicalist, feminist writer and activist. She was the common-law wife of the prominent anarcho-syndicalist leader Rudolf Rocker. The couple's son, Fermin ...

was a Ukrainian-born Jewish anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

, feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

writer and activist. She was the common-law wife

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, or marriage by habit and repute, is a legal framework where a couple may be considered married without having formally registered their relation as a civil ...

of Rudolf Rocker

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was a German anarchist writer and activist. He was born in Mainz to a Roman Catholic artisan family.

His father died when he was a child, and his mother when he was in his teens, so he ...

. In November 1918, Witkop and Rocker moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

; Rocker had been invited by Free Association of German Trade Unions

The Free Association of German Trade Unions (; abbreviated FVdG; sometimes also translated as Free Association of German Unions or Free Alliance of German Trade Unions) was a trade union federation in Imperial and early Weimar Germany. It was foun ...

(FVdG) chairman Fritz Kater

Fritz Kater (12 December 1861 – 20 May 1945) was a German trade unionist active in the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FVdG) and its successor organization, the Free Workers' Union of Germany. He was the editor of the FVdG's organ ...

to join him in building up what would become the Free Workers' Union of Germany

The Free Workers' Union of Germany (; FAUD) was an anarcho-syndicalist trade union in Germany. It stemmed from the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FDVG) which combined with the Ruhr region's Freie Arbeiter Union on September 15, 1919. T ...

(FAUD), an anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

trade union. Both Rocker and Witkop became members of the FAUD.Wolf, SiegbertWitkop, Milly

in ''Datenbank des deutschsprachigen Anarchismus''. Retrieved October 8, 2007. After its founding in early 1919, a discussion about the role of girls and women in the union started. The male-dominated organization had at first ignored gender issues, but soon women started founding their own unions, which were organized parallel to the regular unions, but still formed part of the FAUD. Witkop was one of the leading founders of the Women's Union in Berlin in 1920. On 15 October 1921, the women's unions held a national congress in

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

and the Syndicalist Women's Union (SFB) was founded on a national level. Shortly thereafter, Witkop drafted ''Was will der Syndikalistische Frauenbund?'' (''What Does the Syndicalist Women's Union Want?'') as a platform for the SFB. From 1921, the ''Frauenbund'' was published as a supplement to the FAUD organ '' Der Syndikalist'', Witkop was one of its primary writers.

Witkop reasoned that proletarian women were exploited not only by capitalism like male workers, but also by their male counterparts. She contended therefore that women must actively fight for their rights, much like workers must fight capitalism for theirs. She also insisted on the necessity of women taking part in class struggle and that housewives could use boycotts to support this struggle. From this, she concluded the necessity of an autonomous women's organization in the FAUD. Witkop also held that domestic work should be deemed equally valuable to wage labor.

' ('' en, Free Women'') was an anarchist women's organization in Spain that aimed to empower working-class women. It was founded in 1936 by

Lucía Sánchez Saornil

Lucía Sánchez Saornil (1895–1970), was a lesbian Spanish poet, militant anarchist and feminist. She is best known as one of the founders (alongside Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch Y Gascón) of ''Mujeres Libres'' and served in the Conf ...

, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón

Amparo Poch y Gascón (15 October 1902 – 15 April 1968) was a Spanish anarchist,

pacifist, doctor, and activist in the years leading up to and during the Spanish Civil War.

Poch y Gascón was born in Zaragoza.Lola Campos, ''Mujeres aragones ...

and had approximately 30,000 members. The organization was based on the idea of a "double struggle" for women's liberation

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism that emerged in the late 1960s and continued into the 1980s primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which effected great ...

and social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political syst ...

and argued that the two objectives were equally important and should be pursued in parallel. In order to gain mutual support, they created networks of women anarchists. Flying day-care centres were set up in efforts to involve more women in union activities.

The organization also produced propaganda through radio, traveling libraries and propaganda tours in order to promote their cause. Organizers and activists traveled through rural parts of Spain to set up rural collectives and support for women. To prepare women for leadership roles in the anarchist movement, they organized schools, women-only social groups and a women-only newspaper to help women gain

The organization also produced propaganda through radio, traveling libraries and propaganda tours in order to promote their cause. Organizers and activists traveled through rural parts of Spain to set up rural collectives and support for women. To prepare women for leadership roles in the anarchist movement, they organized schools, women-only social groups and a women-only newspaper to help women gain self-esteem

Self-esteem is confidence in one's own worth or abilities. Self-esteem encompasses beliefs about oneself (for example, "I am loved", "I am worthy") as well as emotional states, such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. Smith and Mackie (2007) d ...

and confidence in their abilities and network with one another to develop their political consciousness

Following the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Marx outlined the workings of a political consciousness.

The politics of consciousness

Consciousness typically refers to the idea of a being who is self-aware. It is a distinction often re ...

. Many of the female workers in Spain were illiterate and the ''Mujeres Libres'' sought to educate them through literacy programs, technically oriented classes and social studies classes. Schools were also created for train nurses to help injured in emergency medical clinics. Medical classes also provided women with information on sexual health and pre and post-natal care. The ''Mujeres Libres'' also created a woman run magazine to keep all of its members informed. The first monthly issue of ''Mujeres Libres'' was published on May 20, 1936 (ack 100). However, the magazine only had 14 issues and the last issue was still being printed when the Spanish Civil War battlefront reached Barcelona, and no copies survived. The magazine addressed working-class women and focused on "awakening the female conscience toward libertarian ideas".

Lucía Sánchez Saornil

Lucía Sánchez Saornil

Lucía Sánchez Saornil (1895–1970), was a lesbian Spanish poet, militant anarchist and feminist. She is best known as one of the founders (alongside Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch Y Gascón) of ''Mujeres Libres'' and served in the Conf ...

was a Spanish anarchist, feminist and poet, who is best known as one of the founders of ''Mujeres Libres''. She served in the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, which was long affiliated with the International Workers' Association (AIT). When working wi ...

(CNT) and Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista

Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista ( en, International Antifascist Solidarity, italic=yes), SIA, was a humanitarian organisation that existed in the Second Spanish Republic. It was politically aligned with the anarcho-syndicalist movement com ...

(SIA). By 1919, she had been published in a variety of journals, including ''Los Quijotes'', ''Tableros'', ''Plural'', ''Manantial'' and ''La Gaceta Literaria''. Working under a male pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

at a time when homosexuality was criminalized and subject to censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

and punishment, she was able to explore lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

themes. In the 1930s, she was an outspoken voice for women and against defining women by their reproductive capacity.

Italian migrant women

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson ( ) is the largest City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Passaic County, New Jersey, Passaic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Maria Roda

Maria Roda (1877–1958) was an Italian American anarchist- feminist activist, speaker and writer, who participated in the labor struggles among textile workers in Italy and the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early ...

, Ernestina Cravello

Ernestina Cravello (1880–1942) was an Italian Americans, Italian-American Anarcha-feminism, anarcha-feminist activist during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Biography

Cravello was born in Northern Italy and emigrated to the United St ...

and Ninfa Baronio

Ninfa Baronio (1874-1969) was an Italian-American anarcha-feminist activist during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After emigrating from Northern Italy to Paterson, New Jersey, she helped found Paterson's anarchist ''Gruppo Diritto all'E ...

founded Paterson's ''Gruppo Emancipazione della Donna'' (Women's Emancipation Group) in 1897. The group gave lectures, wrote for the anarchist press, and published pamphlets. They also formed the ''Club Femminile de Musica e di Canto'' (Women's Music and Song Club) and the ''Teatro Sociale'' (Social Theater). The Teatro performed plays which challenged Catholic sexual morality and called for the emancipation of women. Their plays stood in marked contrast to other radical works in which women were depicted as victims in need of rescuing by male revolutionaries. They often traveled to perform their plays, and connected with other Italian anarchist women in Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

, Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

and New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

. The Paterson group met regularly for about seven years and inspired other women to form similar groups. Their Southern Italian contemporaries included Elvira Catello in East Harlem

East Harlem, also known as Spanish Harlem or and historically known as Italian Harlem, is a neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, New York City, roughly encompassing the area north of the Upper East Side and bounded by 96th Street to the south, F ...

, who ran a popular theater group and a radical bookstore; Maria Raffuzzi in Manhattan, who co-founded ''Il Gruppo di Propaganda Femminile'' (Women's Propaganda Group) in 1901; and Maria Barbieri, an anarchist orator who helped organize the silk workers in Paterson.

Anarchist Italian women such as Maria Roda flouted convention and Catholic teaching by rejecting traditional marriage in favor of "free unions". In practice, these unions often turned out to be lifelong and monogamous, with the division of labor falling along traditional lines. The anarchist writer Ersilia Cavedagni

Ersilia Cavedagni (April 2, 1862after 1941) was an Italian-American anarcha-feminist activist, writer, and editor.

Biography

Cavedagni was born in Northern Italy to Francesco and Enrica Amadei. At a young age she married the Bolognese anarchis ...

believed that "the woman is and will always be the educator of the family, that which has and will always have the most direct and the most important influence on the children".

Anarcha-feminism in Meiji and Taisho-era Japan

Kanno Sugako

, also known as , was a Japanese anarcha-feminist journalist. She was the author of a series of articles about gender oppression, and a defender of freedom and equal rights for men and women.

In 1910, she was accused of treason by the Japanese g ...

and Itō Noe

was a Japanese anarchist, social critic, author, and feminist. She was the editor-in-chief of the feminist magazine '' Seitō (Bluestocking)''. Her progressive anarcha-feminist ideology challenged the norms of the Meiji and Taishō periods ...

were Japanese anarchist feminists, both of whom died fighting for anarchism. Kanno worked as a journalist and advocated feminist reforms. She understood the subjugation of women in Japanese society as ultimately stemming from the emperor's divine authority, and, in 1909, became involved in a plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

with bombs. On January 25, 1911, 29-year-old Kanno was hanged. Itō was a member of the Bluestocking

''Bluestocking'' is a term for an educated, intellectual woman, originally a member of the 18th-century Blue Stockings Society from England led by the hostess and critic Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), the "Queen of the Blues", including Eliz ...

Society and contributed to '' Seitō'', becoming Editor-in-Chief in 1916. As a writer and editor, she published many writings concerning feminism, "abortion, prostitution, free love and motherhood," including 'The New Woman's Road,' 'To Mr. Shimoda Jirô,' and 'Recent Thoughts.'Mikiso Hane, ''Peasants, Rebels, Women, and Outcastes: The Underside of Modern Japan'', 2nd Ed. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003. 247-292. Several issues of the journal were censored as she began to include more feminist writings in which she fervently defended women's autonomy and focused on abortion and prostitution. She translated Emma Goldman's ''The Tragedy of Woman's Emancipation'' and ''Minorities vs. Majorities,'' among other anarcha-feminist writings. She met Sakae Ōsugi Sakae may refer to:

Places in Japan

* Sakae, Chiba (Japanese: 栄町; ''sakae-machi''), a town in Chiba Prefecture

* Sakae, Niigata (Japanese: 栄町; ''sakae-machi''), a town in Niigata Prefecture

* Sakae, Nagano (Japanese: 栄村; ''sakae-mura'') ...

and began a relationship with him; he was also married to another woman and in a relationship with Ichiko Kamichika

Ichiko Kamichika (神近 市子, ''Kamichika Ichiko'') (June 6, 1888 August 1, 1981) was a journalist, feminist, writer, translator, and critic. Her birth name was Ichi Kamichika and her pen name was Ei, Yo, or Ou Sakaki. After World War II, Ka ...

at the time. These relationships became strained; after Itō kissed Ōsugi in public, Ichiko stabbed Ōsugi. Itō remained Ōsugi's sole partner. Itō called upon anarchists to engage in anarchy as an "everyday practice." After suffering police harassment often, Itō, Ōsugi, and Ōsugi's young nephew Munekazu were strangled to death by a group of Kenpeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspecte ...

led by Lieutenant Masahiko Amakasu

was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army imprisoned for his involvement in the Amakasu Incident, the extrajudicial execution of anarchists after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, who later became head of the Manchukuo Film Association.

Bio ...

.

Contemporary developments

1970s

In the pamphlet ''Anarchism: The Feminist Connection'' (1975),Peggy Kornegger

Peggy Kornegger is an American writer. In the 1970s she identified herself as an anarcha-feminist, and was an editor of the American feminist magazine ''The Second Wave''. Her article "Anarchism: The Feminist Connection" (1975) was reprinted as ...

uses three major principles to define anarchism:

# "Belief in the abolition of authority, hierarchy, government."

# "Belief in both individuality and collectivity."

# "Belief in both spontaneity and organization."

She uses the example of an anarchist tradition in Spain leading to spontaneous appropriation of factories and land during the Spanish Civil War to highlight the possibility of collective revolutionary change, and the failure of the 1968 French strike to highlight the problems of inadequate preparation and left-wing authoritarianism. Kornegger links the necessity of a specifically feminist anarchist revolution not only to the subjection of women by male anarchists, but also to the necessity of replacing hierarchical "subject/object" relationships with "subject-to-subject" relationships.

Second Wave Feminist Movement

The 1970s was characterized by the revival of the anarchist movement. During this era, the second wave feminist movement was occurring simultaneously, and from it came the development of anarcha-feminism. The term anarcha-feminism was first used in an August 1970 issue of ''It Aint Me Babe'', the first comic book made entirely by women. In a critique of Jo Freeman's essay "The Tyranny of Structurelessness

"The Tyranny of Structurelessness" is an influential essay by American feminist Jo Freeman that concerns power relations within radical feminist collectives. The essay, inspired by Freeman's experiences in a 1960s women's liberation group, reflect ...

", Cathy Levine stated that feminists often practiced anarchist organizing ethics in the 1970s, as "all across the country independent groups of women began functioning without the structure, leaders and other factotums of the male Left, creating independently and simultaneously, organisations similar to those of anarchists of many decades and locales". This was as a counter to dominant Marxist forms of organizing that were hierarchical and authoritarian.

West Germany

A prominent example for this gives the founding of the in 1973: "We simply skipped the step of a theoretical platform, which was a must in other groups. Even before this meeting there was a consensus, so that we didn't need a lot of discussion, because all of us had the same experience with left-wing groups behind us."

A prominent example for this gives the founding of the in 1973: "We simply skipped the step of a theoretical platform, which was a must in other groups. Even before this meeting there was a consensus, so that we didn't need a lot of discussion, because all of us had the same experience with left-wing groups behind us."

Cristina Perincioli

Cristina Perincioli (born November 11, 1946, in Bern, Switzerland) is a Swiss film director, writer, multimedia producer and webauthor. She moved to Berlin in 1968. Since 2003 she has lived Stücken in Brandenburg.

Life and career

Cristina Peri ...

states that it was the women of the , "the Sponti rom ''spontaneous''

Rom, or ROM may refer to:

Biomechanics and medicine

* Risk of mortality, a medical classification to estimate the likelihood of death for a patient

* Rupture of membranes, a term used during pregnancy to describe a rupture of the amniotic sac

* R ...

women who (re-)founded the feminist movement. For that reason it is worth taking a closer look at anarchist theory and tradition", further explaining:In the 1970s, the West German women's centers, cradle of all those feminist projects, were so inventive and productive because " ery group at the Berlin women's center was autonomous and could choose whatever field they wished to work in. The plenary never tried to regiment the groups. Any group or individual could propose actions or new groups, and they were welcome to realize their ideas as long as they could find enough people to help them. There was thus no thematic let alone political "line" that determined whether an enterprise was right and permissible. Not having to follow a line also had the advantage of flexibility". The Berlin women's center's info of 1973 stated: "We constantly and collectively developed the women's center's self-understanding. We therefore do not have a self-understanding on paper, but are learning together."

Autonomous feminists of the women's centers viewed the West German state with deep distrust. To apply for state funds was unthinkable (apart for a women's shelter). In the 1970s the search for terrorists would affect any young person active in whatever groups. Over years women's centers were searched by Police as well as cars and homes of many feminists. The West Berlin women's center went on a week-long hunger strike in 1973 in support of the women strike in prison and rallied repeatedly at the women's jail in Lehrter Straße

The Lehrter Straße (also: ''Lehrter Strasse'', ''Lehrterstraße'', and ''Lehrterstrasse'') is a residential street in Moabit, a sub district of Mitte, one of Berlin's 12 boroughs of which the borders were redefined following the 1989 Fall o ...

. From this jail, Inge Viett

Inge Viett (12 January 1944 – 9 May 2022) was a member of the West Germany, West German left-wing militant organisations "2 June Movement" and the "Red Army Faction, Red Army Faction (RAF)", which she joined in 1980. In 1982 she became the last ...

escaped in 1973 and 1976.

Militant women

In the West Berlin anarchist newspaper '' Agit 883'', a Women's Liberation Front proclaimed in 1969 combatively that "it will raise silently out of the darkness, strike and disappear again and criticized the women who "brag about jumping onto a party express without realizing that the old jalopy has to be electrified first before it can drive. They've chosen security over the struggle".

Many women joined the

In the West Berlin anarchist newspaper '' Agit 883'', a Women's Liberation Front proclaimed in 1969 combatively that "it will raise silently out of the darkness, strike and disappear again and criticized the women who "brag about jumping onto a party express without realizing that the old jalopy has to be electrified first before it can drive. They've chosen security over the struggle".

Many women joined the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (RAF, ; , ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang (, , active 1970–1998), was a West German far-left Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group founded in 1970.

The ...

and the anarchist militant 2 June Movement

The 2 June Movement (german: link=no, Bewegung 2. Juni) was a West German anarchist militant group based in West Berlin. Active from January 1972 to 1980, the anarchist group was one of the few militant groups at the time in Germany. Although ...

. Neither of these terrorist groups showed feminist concerns. The women's group Rote Zora (split from the Revolutionäre Zellen) legitimized militance with feminist theory in the 1980s and attacked bioengineering facilities.

More contemporary movements include the YPJ

(YPJ) ar, وحدات حماية المرأة

, image = File:YPJ Flag.svg

, caption = Flag of the YPJ

, dates = April 2013–present

, commander1 = Nesrin ...

, a Kurdish militant organization composed entirely of women. The YPJ is active in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

based of the ideology of Democratic confederalism

Democratic confederalism ( ku, Konfederalîzma demokratîk), also known as Kurdish communalism or Apoism, is a political concept theorized by Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan about a system of democratic self-organization ...

a variant of libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

and Jineology

Jineology () is a form of feminism and of gender equality advocated by Abdullah Öcalan, the representative leader of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) and the broader Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) umbrella. From the background of honor-based ...

(lit: "Women study" in Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

), a radical feminist ideology.

LGBT rights

Queer anarchism

Queer anarchism, or anarcha-queer, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates anarchism and social revolution as a means of queer liberation and abolition of hierarchies such as homophobia, lesbophobia, transmisogyny, biphobia, transphob ...

is an anarchist school of thought

Anarchism is the political philosophy which holds ruling classes and the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." ''The Concise Oxford Diction ...

that advocates anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

and social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political syst ...

as a means of queer liberation and abolition of hierarchies such as homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitude (psychology), attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, h ...

, lesbophobia

Lesbophobia comprises various forms of prejudice and negativity towards lesbians as individuals, as couples, or as a social group. Based on the categories of sex, sexual orientation, identity, and gender expression, this negativity encompasses ...

, biphobia

Biphobia is aversion toward bisexuality and bisexual people as individuals. It is a form of homophobia against those in the bisexual community. It can take the form of denial that bisexuality is a genuine sexual orientation, or of negative s ...

, transphobia

Transphobia is a collection of ideas and phenomena that encompass a range of negative attitudes, feelings, or actions towards transgender people or transness in general. Transphobia can include fear, aversion, hatred, violence or anger tow ...

, heteronormativity

Heteronormativity is the concept that heterosexuality is the preferred or normal mode of sexual orientation. It assumes the gender binary (i.e., that there are only two distinct, opposite genders) and that sexual and marital relations are most ...

, patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males a ...

, and the gender binary

The gender binary (also known as gender binarism) is the classification of gender into two distinct, opposite forms of masculine and feminine, whether by social system, cultural belief, or both simultaneously. Most cultures use a gender bina ...

. People who campaigned for LGBT rights both outside and inside the anarchist and LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is a ...

movements include John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay, also known by the pseudonym Sagitta, (6 February 1864 – 16 May 1933) was an egoist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of '' Die Anarchisten'' (The Anarchists, 1891) an ...

, Adolf Brand

Gustav Adolf Franz Brand (14 November 1874 – 2 February 1945) was a German writer, egoist anarchist, and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.

Early life

Adolf Brand was born on 14 November 1874 in Be ...

and Daniel Guérin

Daniel Guérin (; 19 May 1904, in Paris – 14 April 1988, in Suresnes) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of ...

. Individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their Will (philosophy), will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean ...

Adolf Brand published ''Der Eigene

''Der Eigene'' was one of the first gay journals in the world, published from 1896 to 1932 by Adolf Brand in Berlin. Brand contributed many poems and articles; other contributors included writers Benedict Friedlaender, Hanns Heinz Ewers, Erich M� ...

'' from 1896 to 1932 in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, the first sustained journal dedicated to gay issues.

Anarcha-feminist collectives such as the Spanish squat Eskalera Karakola

Eskalera Karakola is a feminist self-managed social centre in Madrid, Spain. Women squatted a bakery on Calle de Embajadores 40 from 1996 until 2005, whereupon they were given a building at Calle de Embajadores 52.

History

Eskalera Karakola ...

and the Bolivian Mujeres Creando

Mujeres Creando ('' Eng: Women Creating'') is a Bolivian anarcha-feminist collective that participates in a range of anti- poverty work, including propaganda, street theater and direct action. The group was founded by María Galindo, Mónica Me ...

give high importance to lesbian and bisexual female issues. The Fag Army is a left-wing queer anarchist group in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, which launched its first action on August 18, 2014, when it pied

A piebald or pied animal is one that has a pattern of unpigmented spots (white) on a pigmented background of hair, feathers or scales. Thus a piebald black and white dog is a black dog with white spots. The animal's skin under the white backgro ...

the Minister for Health and Social Affairs, Christian Democrat

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

leader Göran Hägglund

Bo Göran Hägglund (born 27 January 1959) is a Swedish politician of the Christian Democrats. He was Leader of the Christian Democrats from 2004 to 2015, Member of the Riksdag from 1991 to 2015, and served as Minister for Social Affairs from 2 ...

.

Ecological feminism or Ecofeminism

Sometimes it is argued thatEcofeminism

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in h ...

developed out of the anarcha-feminist concerns for the abolition all forms of domination. However the focus of ecofeminism is broader in that it is ecocentric not anthropocentric, concerned equally with human domination and exploitation of the natural world. Both anarcha-feminism and ecofeminism stress the importance of political action.

In the 1970s, the impacts of post-World War II technological development led many women to organise against issues from the toxic pollution of neighbourhoods to nuclear weapons testing on indigenous lands. This grassroots activism emerging across every continent was both intersectional and cross-cultural in its struggle to protect the conditions for reproduction of Life on Earth. Known as ecofeminism, the political relevance of this movement continues to expand. Classic statements in its literature include Carolyn Merchant, USA, ''The Death of Nature

''The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution'' is a 1980 book by historian Carolyn Merchant. It is one of the first books to explore the Scientific Revolution through the lenses of feminism and ecology. It can be seen as an ...

''; Maria Mies, Germany, ''Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale''; Vandana Shiva, India, ''Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development''; Ariel Salleh, Australia, ''Ecofeminism as Politics: nature, Marx, and the postmodern''. Ecofeminism involves a profound critique of Eurocentric epistemology, science, economics, and culture. It is increasingly prominent as a feminist response to the contemporary breakdown of the planetary ecosystem.

Activism and protests

Anarcha-feminists have been active in protesting and

Anarcha-feminists have been active in protesting and activism

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in Social change, social, Political campaign, political, economic or Natural environment, environmental reform with the desire to make Social change, changes i ...

throughout modern history. Activists such as Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

were actively campaigned for equal rights through the early 1900s.

Intersectional construction

Anarchism and feminism has been influenced by post-structuralism, post-colonial theory, critical race theory, and queer theory. However, a comprehensive anarcha-feminism perspective that considers all these theories has yet to exist. Because of this, Deric Shannon proposes a possible contemporary anarcha-feminism construction that engages all the listed theories. This proposal aims to mirror the different branches and diversity of anarchism and feminism. One possible construction of contemporary anarcha-feminist construction would argue for "a world in which resources are distributed in a cooperative and egalitarian manner, rather than under our current system of capitalist tyranny." This construction will also "actively argue and fight for working class liberation from capitalism." It recognizes that marginalized groups need their own movements that address their specific needs alongside the overall movement. This anarcha-feminism also acknowledges that inherently hierarchical practices must be abolished to establish a non-hierarchical society. Of course, the contemporary construction will oppose power and stand against domination. This opposition will be guided by post-structuralism, post-colonial, critical race, and queer theories. The new construction will avoid prioritizing one issue over another. Instead, it will recognize the intersectionality of all issues and aim to include all axes of oppression.In academia

In a 2017 article,Chiara Bottici

Chiara Bottici (born 24 January 1975) is an Italian philosopher and writer.

Biography

Bottici is Associate Professor of Philosophy and Director of Gender Studies at The New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College, New York. Bottici ...

argues that anarcha-feminism has been the subject of insufficient discussion in public debate and in academia, due in part to a broader hostility to anarchism but also due to difficulties in distinguishing between anarcha-feminism and anarchism per se.

Relation to Marxist feminism

Bottici argues that the risk of economicreductionism

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical pos ...

that appears in Marxist feminism

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. According ...

, in which women's oppression is understood solely in economic terms, "has ... always been alien to anarcha-feminism"; as such, she argues, anarchism is better suited than Marxism for an alliance with feminism.

In media

''Libertarias

''Libertarias'' (English: ''Libertarians'') is a Spanish historical drama made in 1996. It was written and directed by Vicente Aranda.

In 1936, Maria (Ariadna Gil), a young nun is recruited by Pilar (Ana Belén), a militant feminist, into an a ...

'' is a historical drama film made in 1996 about the Spanish anarcha-feminist organization ''Mujeres Libres''. In 2010, the Argentinian film ''Ni dios, ni patrón, ni marido'' was released which is centered on the story of anarcha-feminist Virginia Bolten

Virginia Bolten (26 December 1870 – 1960) was an Argentine journalist as well as an anarchist and feminist activist of German descent. A gifted orator, she is considered as a pioneer in the struggle for women's rights in Argentina. She was de ...

and her publishing of the newspaper ' ('' en, The Woman's Voice'').

Contemporary anarcha-feminist writers/theorists include Kornegger, L. Susan Brown

''The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism, and Anarchism'' is a 1993 political science book by L. Susan Brown. She begins by noting that liberalism and anarchism seem at times to share common components, but on other occasions ...

, and the eco-feminist Starhawk.

See also

* Anarchism and issues related to love and sex * ''Bluestocking (magazine), Bluestocking'' *Ecofeminism

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in h ...

* Feminist economics

* Feminist political ecology

* Feminist political theory

* ''Free Society''

* Issues in anarchism

* Queer anarchism

Queer anarchism, or anarcha-queer, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates anarchism and social revolution as a means of queer liberation and abolition of hierarchies such as homophobia, lesbophobia, transmisogyny, biphobia, transphob ...

* Relationship anarchy

* Socialist feminism

* Women's health

* Women in the EZLN

Notes

References