Libertarian Communists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a

Bob Black. ''Nightmares of Reason''

. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society. L. Susan Brown, ''

"Does Work Really Work?"

. Anarcho-communism developed out of radical

Early Christian communities have also been described as having anarcho-communist characteristics. Frank Seaver Billings described " Jesusism" as a combination of anarchism and communism. Examples of later Christian egalitarian communities include the

Early Christian communities have also been described as having anarcho-communist characteristics. Frank Seaver Billings described " Jesusism" as a combination of anarchism and communism. Examples of later Christian egalitarian communities include the

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the  In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880),

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880),

Chapter IX The Need For Luxury

He maintained that in anarcho-communism, "houses, fields, and factories will no longer be private property, and that they will belong to the commune or the nation and money, wages, and trade would be abolished".Kropotkin, Pete

Chapter 13 ''The Collectivist Wages System'' from ''The Conquest of Bread''

, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906. Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of private property into

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of private property into

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, " ile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, " ile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the

"Against organization"

. Retrieved 6 October 2010. By the 1880s, anarcho-communism was already present in the United States, as seen in the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by

at the

In

In  Two texts made by the anarchist communists

Two texts made by the anarchist communists

The Korean Anarchist Movement in

The Korean Anarchist Movement in

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

In Spain, the national anarcho-syndicalist trade union

In Spain, the national anarcho-syndicalist trade union  Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone

/ref> The ''Manifesto of Libertarian Communism'' was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the ''Federation Communiste Libertaire'' of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as

The Informal Anarchist Federation (not to be confused with the synthesist Italian Anarchist Federation, also FAI) is an Italian insurrectionary anarchist organization. Italian intelligence sources have described it as a "horizontal" structure of various anarchist terrorist groups, united in their beliefs in revolutionary armed action. In 2003, the group claimed responsibility for a bombing campaign targeting several European Union institutions. Currently, alongside the previously mentioned federations, the

Communist anarchism shares many traits with collectivist anarchism, but the two are distinct. Collectivist anarchism believes in collective ownership, while communist anarchism negates the entire concept of ownership in favor of the concept of usage. Crucially, the abstract relationship of "landlord" and "tenant" would no longer exist, as such titles are held to occur under conditional legal coercion and are not necessary to occupy buildings or spaces (

Communist anarchism shares many traits with collectivist anarchism, but the two are distinct. Collectivist anarchism believes in collective ownership, while communist anarchism negates the entire concept of ownership in favor of the concept of usage. Crucially, the abstract relationship of "landlord" and "tenant" would no longer exist, as such titles are held to occur under conditional legal coercion and are not necessary to occupy buildings or spaces (

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable

In anthropology and the social sciences, a gift economy (or gift culture) is a mode of exchange where valuable

Anarchist communists counter the capitalist conception that communal property can only be maintained by force and that such a position is neither fixed in nature nor unchangeable in practice, citing numerous examples of communal behavior occurring naturally, even within capitalist systems. Anarchist communists call for the abolition of private property while maintaining respect for personal property. As such, the prominent anarcho-communist

Anarchist communists counter the capitalist conception that communal property can only be maintained by force and that such a position is neither fixed in nature nor unchangeable in practice, citing numerous examples of communal behavior occurring naturally, even within capitalist systems. Anarchist communists call for the abolition of private property while maintaining respect for personal property. As such, the prominent anarcho-communist

political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

and anarchist school of thought

Anarchism is the political philosophy which holds ruling classes and the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." ''The Concise Oxford Dicti ...

that advocates communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains respect for personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership

Social ownership is the appropriation of the surplus product, produced by the means of production, or the wealth that comes from it, to society as a whole. It is the defining characteristic of a socialist economic system. It can take the form of ...

of property and direct democracy among other horizontal networks for the allocation of production and consumption based on the guiding principle "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs

"From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" (german: Jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen) is a slogan popularised by Karl Marx in his 1875 '' Critique of the Gotha Programme''. The principle ref ...

". Some forms of anarcho-communism, such as insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based ...

, are strongly influenced by egoism

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or , as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normativ ...

and radical individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

, believing anarcho-communism to be the best social system for realizing individual freedom."Towards the creative Nothing" byRenzo Novatore

Abele Rizieri Ferrari (May 12, 1890 – November 29, 1922), better known by the pen name Renzo Novatore, was an Italian individualist anarchist, illegalist and anti-fascist poet, philosopher and militant, now mostly known for his posthumously p ...

Post-left anarcho-communist Bob Black after analysing insurrectionary anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani's view on anarcho-communism went as far as saying that "communism is the final fulfillment of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

...The apparent contradiction between individualism and communism rests on a misunderstanding of both...Subjectivity is also objective: the individual really is subjective. It is nonsense to speak of "emphatically prioritizing the social over the individual,"...You may as well speak of prioritizing the chicken over the egg. Anarchy is a "method of individualization." It aims to combine the greatest individual development with the greatest communal unityBob Black. ''Nightmares of Reason''

. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society. L. Susan Brown, ''

The Politics of Individualism

''The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism, and Anarchism'' is a 1993 political science book by L. Susan Brown. She begins by noting that liberalism and anarchism seem at times to share common components, but on other occasions ...

'', Black Rose Books (2002). L. Susan Brown"Does Work Really Work?"

. Anarcho-communism developed out of radical

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

currents after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, but it was first formulated as such in the Italian section of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

. The theoretical work of Peter Kropotkin took importance later as it expanded and developed pro-organizationalist and insurrectionary anti-organizationalist sections. To date, the best-known examples of anarcho-communist societies (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) are the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution and the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

during the Russian Revolution, where anarchists such as Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

worked to create and defend anarcho-communism through the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine ( uk, Революційна Повстанська Армія України), also known as the Black Army or as Makhnovtsi ( uk, Махновці), named after their leader Nestor Makhno, was a ...

.

In 1929, anarcho-communism was implemented in Korea by the Korean Anarchist Federation in Manchuria (KAFM) and the Korean Anarcho-Communist Federation (KACF), with help from anarchist general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

and independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

activist Kim Chwa-chin

Kim Chwa-jin or Kim Jwa-jin (December 16, 1889 – January 24, 1930), sometimes called by his pen name Baegya, was a Korean general, independence activist, and anarchist who played an important role in the early attempts at development of anar ...

, lasting until 1931, when Imperial Japan assassinated Kim and invaded from the south, while the Chinese Nationalists

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Taiw ...

invaded from the north, resulting in the creation of Manchukuo, a puppet state of the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

. Through the efforts and influence of the Spanish anarchists

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of cl ...

during the Spanish Revolution within the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

starting in 1936, anarcho-communism existed in most of Aragon, parts of the Levante and Andalusia, as well as in the stronghold of anarchist Catalonia

Revolutionary Catalonia (21 July 1936 – 10 February 1939) was the part of Catalonia (autonomous region in northeast Spain) controlled by various anarchist, communist, and socialist trade unions, parties, and militias of the Spanish Civil W ...

. In 1939, these anarcho-communists were crushed by the combined forces of the Francoist

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

(the regime that won the war), Nationalist allies such as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Benito Mussolini, and even Spanish Communist Party repression (backed by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

), as well as economic and armaments blockades from the capitalist state

The capitalist state is the state, its functions and the form of organization it takes within capitalist socioeconomic systems.Jessop, Bob (January 1977). "Recent Theories of the Capitalist State". ''Soviet Studies''. 1: 4. pp. 353–373. This ...

s and the Spanish Republic itself governed by the Republicans.

History

Early precursors

Early Christian communities have also been described as having anarcho-communist characteristics. Frank Seaver Billings described " Jesusism" as a combination of anarchism and communism. Examples of later Christian egalitarian communities include the

Early Christian communities have also been described as having anarcho-communist characteristics. Frank Seaver Billings described " Jesusism" as a combination of anarchism and communism. Examples of later Christian egalitarian communities include the Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

in England. Gerrard Winstanley

Gerrard Winstanley (19 October 1609 – 10 September 1676) was an English Protestant religious reformer, political philosopher, and activist during the period of the Commonwealth of England. Winstanley was the leader and one of the founde ...

, who was part of the Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

movement, wrote in his 1649 pamphlet ''The New Law of Righteousness'' that there "shall be no buying or selling, no fairs nor markets, but the whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man" and "there shall be none Lord over others, but every one shall be a Lord of himself".

The Diggers resisted the tyranny of the ruling class and kings, instead operating cooperatively to get work done, manage supplies, and increase economic productivity. Due to the communes established by the Diggers being free from private property, along with economic exchange (all items, goods, and services were held collectively), their communes could be called early, functioning communist societies, spread out across the rural lands of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Before the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, common ownership of land and property was much more prevalent across the European continent, but the Diggers were set apart by their struggle against monarchical rule. They sprung up using workers' self-management

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-management is a def ...

after the fall of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

.

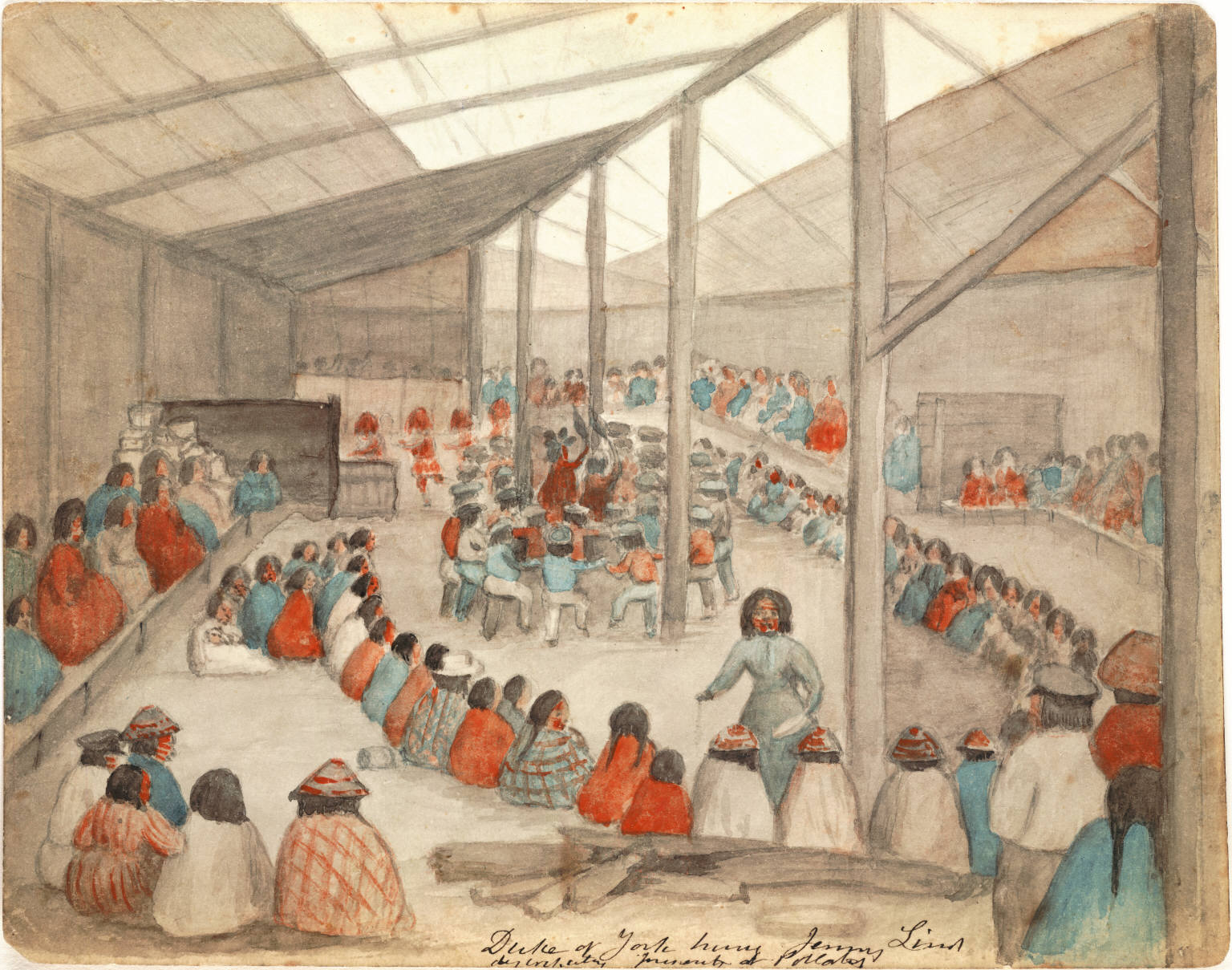

In 1703, Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan, wrote the novel '' New Voyages to North America,'' where he outlined how indigenous communities of the North American continent cooperated and organized. The author found the agrarian societies and communities of pre-colonial

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

North America to be nothing like the monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

, unequal states of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, both in their economic structure and lack of any state. He wrote that the life natives lived was "anarchy", this being the first usage of the term to mean something other than chaos. He wrote that there were no priests, courts, laws, police, ministers of state, and no distinction of property, no way to differentiate rich from poor, as they were all equal and thriving cooperatively.

During the French Revolution, Sylvain Maréchal, in his ''Manifesto of the Equals'' (1796), demanded "the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth" and looked forward to the disappearance of "the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed".

Joseph Déjacque and the Revolutions of 1848

Joseph Déjacque

Joseph Déjacque (; 27 December 1821, in Paris – 1864, in Paris) was a French early anarcho-communist poet, philosopher and writer. He coined the term "libertarian" (French: ''libertaire'') for himselfJoseph DéjacqueDe l'être-humain mâle ...

, unlike Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Soci ...

, argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature". According to the anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term libertarian communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains r ...

was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly. The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

, later founder and editor of the four-volume ''Anarchist Encyclopedia

The ''Anarchist Encyclopedia'' was an encyclopedia initiated by the French anarchist activist Sébastien Faure, between 1925 and 1934, published in four volumes.

The original project was to be in five parts:

#an anarchist dictionary

#a history o ...

,'' started the weekly paper (''The Libertarian'') in 1895.

International Workingmen's Association

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the

As a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy, anarcho-communism was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

by Carlo Cafiero

Carlo Cafiero (1846–1892) was an Italian anarchist, champion of Mikhail Bakunin during the second half of the 19th century and one of the main proponents of anarcho-communism and insurrectionary anarchism during the First International

T ...

, Emilio Covelli, Errico Malatesta, Andrea Costa

Andrea is a given name which is common worldwide for both males and females, cognate to Andreas, Andrej and Andrew.

Origin of the name

The name derives from the Greek word ἀνήρ (''anēr''), genitive ἀνδρός (''andrós''), that r ...

, and other ex- Mazzinian republicans. Collectivist anarchists

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, Buckley, A. M. (2011). ''Anarchism''. Essential Libraryp. 97 "Collectivist anarchism, also called anarcho-collectivism, arose after mutualism." . is an anarchis ...

advocated remuneration for the type and amount of labor adhering to the principle "to each according to deeds" but held out the possibility of a post-revolutionary transition to a communist distribution system according to need. As Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

's associate James Guillaume put it in his essay ''Ideas on Social Organization'' (1876): "When ..production comes to outstrip consumption ..everyone will draw what he needs from the abundant social reserve of commodities, without fear of depletion; and the moral sentiment which will be more highly developed among free and equal workers will prevent, or greatly reduce, abuse and waste".

The collectivist anarchists sought to collectivize ownership of the means of production while retaining payment proportional to the amount and kind of labor of each individual, but the anarcho-communists sought to extend the concept of collective ownership to the products of labor as well. While both groups argued against capitalism, the anarchist communists departed from Proudhon and Bakunin, who maintained that individuals have a right to the product of their labor and to be remunerated for their particular contribution to production. However, Errico Malatesta stated, "instead of running the risk of making a confusion in trying to distinguish what you and I each do, let us all work and put everything in common. In this way each will give to society all that his strength permits until enough is produced for every one; and each will take all that he needs, limiting his needs only in those things of which there is not yet plenty for every one".

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880),

In ''Anarchy and Communism'' (1880), Carlo Cafiero

Carlo Cafiero (1846–1892) was an Italian anarchist, champion of Mikhail Bakunin during the second half of the 19th century and one of the main proponents of anarcho-communism and insurrectionary anarchism during the First International

T ...

explains that private property in the product of labor will lead to unequal accumulation of capital and, therefore, the reappearance of social classes and their antagonisms; and thus the resurrection of the state: "If we preserve the individual appropriation of the products of labour, we would be forced to preserve money, leaving more or less accumulation of wealth according to more or less merit rather than need of individuals". At the Florence Conference of the Italian Federation of the International in 1876, held in a forest outside Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

due to police activity, they declared the principles of anarcho-communism as follows:

The above report was made in an article by Malatesta and Cafiero in the Swiss Jura Federation

The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who shared anti- ...

's bulletin later that year.

Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), often seen as the most important theorist of anarchist communism, outlined his economic ideas in ''The Conquest of Bread

''The Conquest of Bread'' (french: La Conquête du Pain; rus, Хлѣбъ и воля, Khleb i volja, "Bread and Freedom"; in contemporary spelling), also known colloquially as The Bread Book, is an 1892 book by the Russian anarcho-communist P ...

'' and ''Fields, Factories and Workshops

''Fields, Factories, and Workshops'' is an 1899 book by anarchist Peter Kropotkin that discusses the decentralization of industries, possibilities of agriculture, and uses of small industries. Before this book on economics, Kropotkin had been ...

''. Kropotkin felt that cooperation is more beneficial than competition, arguing in his major scientific work '' Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution'' that this was well-illustrated in nature. He advocated the abolition of private property (while retaining respect for personal property) through the "expropriation of the whole of social wealth" by the people themselves Peter Kropotkin, ''Words of a Rebel'', p99. and for the economy to be co-ordinated through a horizontal network of voluntary associationsPeter Kropotkin, ''The Conquest of Bread

''The Conquest of Bread'' (french: La Conquête du Pain; rus, Хлѣбъ и воля, Khleb i volja, "Bread and Freedom"; in contemporary spelling), also known colloquially as The Bread Book, is an 1892 book by the Russian anarcho-communist P ...

'', p145. where goods are distributed according to the physical needs of the individual, rather than according to labor.Marshall Shatz, Introduction to Kropotkin: The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press 1995, p. xvi "Anarchist communism called for the socialization not only of production but of the distribution of goods: the community would supply the subsistence requirements of each individual member free of charge, and the criterion, 'to each according to his labor' would be superseded by the criterion 'to each according to his needs.'" He further argued that these "needs," as society progressed, would not merely be physical but " soon as his material wants are satisfied, other needs, of an artistic character, will thrust themselves forward the more ardently. Aims of life vary with each and every individual; and the more society is civilized, the more will individuality be developed, and the more will desires be varied."Peter Kropotkin, ''The Conquest of Bread'Chapter IX The Need For Luxury

He maintained that in anarcho-communism, "houses, fields, and factories will no longer be private property, and that they will belong to the commune or the nation and money, wages, and trade would be abolished".Kropotkin, Pete

Chapter 13 ''The Collectivist Wages System'' from ''The Conquest of Bread''

, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906.

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of private property into

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home". He supported the expropriation of private property into the commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons c ...

or public goods

In economics, a public good (also referred to as a social good or collective good)Oakland, W. H. (1987). Theory of public goods. In Handbook of public economics (Vol. 2, pp. 485-535). Elsevier. is a good that is both non-excludable and non-riv ...

(while retaining respect for personal property) to ensure that everyone would have access to what they needed without being forced to sell their labor to get it, arguing:

He said that a "peasant who is in possession of just the amount of land he can cultivate" and "a family inhabiting a house which affords them just enough space ..considered necessary for that number of people" and the artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

"working with their own tools or handloom" would not be interfered with,Kropotkin ''Act for yourselves.'' N. Walter and H. Becker, eds. (London: Freedom Press 1985) p. 104–105/ref> arguing that " e landlord owes his riches to the poverty of the peasants, and the wealth of the capitalist comes from the same source".

In summation, Kropotkin described an anarchist communist economy as functioning like this:

Organizationalism vs. insurrectionarism and expansion

At the Berne conference of theInternational Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

in 1876, the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta argued that the revolution "consists more of deeds than words" and that action was the most effective form of propaganda. In the bulletin of the Jura Federation

The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who shared anti- ...

, he declared, "the Italian federation believes that the insurrectional fact, destined to affirm socialist principles by deed, is the most efficacious means of propaganda".

As anarcho-communism emerged in the mid-19th century, it had an intense debate with Bakuninist collectivism

Collectivism may refer to:

* Bureaucratic collectivism, a theory of class society whichto describe the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

* Collectivist anarchism, a socialist doctrine in which the workers own and manage the production

* Collectivis ...

and, within the anarchist movement, over participation in syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

and the workers' movement, as well as on other issues. So in "the theory of the revolution" of anarcho-communism as elaborated by Peter Kropotkin and others, "it is the risen people who are the real agent and not the working class organised in the enterprise (the cells of the capitalist mode of production) and seeking to assert itself as labour power, as a more 'rational' industrial body or social brain (manager) than the employers".

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, " ile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, " ile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

. This anti-reformist tendency was accompanied by an anti-organisational tendency, and its partisans declared themselves in favor of agitation amongst the unemployed for the expropriation of foodstuffs and other articles, for the expropriatory strike and, in some cases, for ' individual recuperation' or acts of terrorism."

Even after Peter Kropotkin and others overcame their initial reservations and decided to enter labor unions, there remained "the anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists, who in France were grouped around Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

's ''Le Libertaire''. From 1905 onwards, the Russian counterparts of these anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists become partisans of economic terrorism and illegal 'expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

s'." Illegalism

Illegalism is a tendency of anarchism that developed primarily in France, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland during the late 1890s and early 1900s as an outgrowth of individualist anarchism. Illegalists embrace criminality either openly or secretly ...

as a practice emerged, and within it, " e acts of the anarchist bombers and assassins ("propaganda by the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

") and the anarchist burglars ("individual reappropriation

The following is a list of terms specific to anarchists. Anarchism is a political and social movement which advocates voluntary association in opposition to authoritarianism and hierarchy.

__NOTOC__

A

:The negation of rule or "government by no ...

") expressed their desperation and their personal, violent rejection of an intolerable society. Moreover, they were clearly meant to be exemplary, invitations to revolt."

Proponents and activists of these tactics, among others, included Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

, Luigi Galleani, Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; 1890–1947), born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (russian: Ви́ктор Льво́вич Киба́льчич), was a Russian revolutionary Marxist, novelist, poet and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks fi ...

, Giuseppe Ciancabilla, and Severino Di Giovanni

Severino Di Giovanni (17 March 1901 – 1 February 1931) was an Italian anarchist who immigrated to Argentina, where he became the best-known anarchist figure in that country for his campaign of violence in support of Sacco and Vanzetti and anti ...

. The Italian Giuseppe Ciancabilla (1872–1904) wrote in "Against organization" that "we don't want tactical programs, and consequently we don't want organization. Having established the aim, the goal to which we hold, we leave every anarchist free to choose from the means that his sense, his education, his temperament, his fighting spirit suggest to him as best. We don't form fixed programs and we don't form small or great parties. But we come together spontaneously, and not with permanent criteria, according to momentary affinities for a specific purpose, and we constantly change these groups as soon as the purpose for which we had associated ceases to be, and other aims and needs arise and develop in us and push us to seek new collaborators, people who think as we do in the specific circumstance."Ciancabilla, Giuseppe"Against organization"

. Retrieved 6 October 2010. By the 1880s, anarcho-communism was already present in the United States, as seen in the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by

Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

and Lizzy Holmes."Lucy Parsons: Woman Of Will"at the

Lucy Parsons Center

The Lucy Parsons Center, located in Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts, is an radical, nonprofit independent bookstore and community center. Formed out of the Red Word bookstore, it is collectively run by volunteers. The Center provides readin ...

Lucy Parsons debated in her time in the United States with fellow anarcho-communist Emma Goldman over free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

and feminism issues. Another anarcho-communist journal later appeared in the United States called '' The Firebrand''. Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but ''Free Society'' was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States."''Free Society'' was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century." ''Emma Goldman: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909'', p. 551. Around that time, these American anarcho-communist sectors debated with the individualist anarchist group around Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

. In February 1888, Berkman left for the United States from his native Russia.Avrich, ''Anarchist Portraits'', p. 202. Soon after he arrived in New York City, Berkman became an anarchist through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing.Pateman, p. iii. He, as well as Emma Goldman, soon came under the influence of Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

, the best-known anarchist in the United States; and an advocate of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

—''attentat'', or violence carried out to encourage the masses to revolt.Walter, p. vii. Berkman became a typesetter for Most's newspaper .

According to anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term ''libertarian communism'' was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly. The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

started the weekly paper (''The Libertarian'') in 1895.

Methods of organizing: platformism vs. synthesism

In

In Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine ( uk, Революційна Повстанська Армія України), also known as the Black Army or as Makhnovtsi ( uk, Махновці), named after their leader Nestor Makhno, was a ...

, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and Social hierarchy, hierarchy, typi ...

committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

or Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. After successfully repelling Austro-Hungarian, White, and Ukrainian Nationalist forces, the Makhnovists militia and anarchist communist territories in Ukraine were eventually crushed by Bolshevik military forces.

In the Mexican Revolution, the Mexican Liberal Party

The Mexican Liberal Party (PLM; es, Partido Liberal Mexicano) was started in August 1900 when engineer Camilo Arriaga published a manifesto entitled ''Invitacion al Partido Liberal'' (Invitation to the Liberal Party). The invitation was addr ...

was established. During the early 1910s, it led a series of military offensives leading to the conquest and occupation of certain towns and districts in Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

, with the leadership of anarcho-communist Ricardo Flores Magón

Cipriano Ricardo Flores Magón (, known as Ricardo Flores Magón; September 16, 1874 – November 21, 1922) was a noted Mexican anarchist and social reform activist. His brothers Enrique and Jesús were also active in politics. Followers of ...

. Kropotkin's ''The Conquest of Bread

''The Conquest of Bread'' (french: La Conquête du Pain; rus, Хлѣбъ и воля, Khleb i volja, "Bread and Freedom"; in contemporary spelling), also known colloquially as The Bread Book, is an 1892 book by the Russian anarcho-communist P ...

'', which Flores Magón considered a kind of anarchist bible, served as the basis for the short-lived revolutionary communes in Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

during the Magónista Revolt of 1911. Emiliano Zapata and his army and allies, including Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

, fought for agrarian reform in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Specifically, they wanted to establish communal land rights

Land law is the form of law that deals with the rights to use, alienate, or exclude others from land. In many jurisdictions, these kinds of property are referred to as real estate or real property, as distinct from personal property. Land use a ...

for Mexico's indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

population, which had mostly lost its land to the wealthy elite of European descent. Zapata was partly influenced by Ricardo Flores Magón. The influence of Flores Magón on Zapata can be seen in the Zapatistas' Plan de Ayala

The Plan of Ayala (Spanish: ''Plan de Ayala'') was a document drafted by revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution. In it, Zapata denounced President Francisco Madero for his perceived betrayal of the revolutionary ide ...

, but even more noticeably in their slogan (Zapata never used this slogan) ''Tierra y libertad'' or "land and liberty", the title and maxim of Flores Magón's most famous work. Zapata's introduction to anarchism came via a local schoolteacher, Otilio Montaño Sánchez, later a general in Zapata's army, executed on 17 May 1917, who exposed Zapata to the works of Peter Kropotkin and Flores Magón at the same time as Zapata was observing and beginning to participate in the struggles of the peasants for the land.

A group of exiled Russian anarchists

Anarchism in Russia has its roots in the early mutual aid systems of the medieval republics and later in the popular resistance to the Tsarist autocracy and serfdom. Through the history of radicalism during the early 19th-century, anarchism d ...

attempted to address and explain the anarchist movement's failures during the Russian Revolution. They wrote the ''Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists,'' which was written in 1926 by ''Dielo Truda

''The Cause of Labor'' (russian: Дело Труда, trans-lit=Delo Truda) was a libertarian communist magazine published by exiled Russian and Ukrainian anarchists. Initially under the editorship of Peter Arshinov, after it published the '' ...

'' ("Workers' Cause"). The pamphlet analyzes the fundamental anarchist beliefs, a vision of an anarchist society, and recommendations on how an anarchist organization should be structured. According to the ''Platform'', the four main principles by which an anarchist organization should operate are ideological unity, tactical unity, collective action, and federalism. The Platform argues, "We have vital need of an organization which, having attracted most of the participants in the anarchist movement, would establish a common tactical and political line for anarchism and thereby serve as a guide for the whole movement".

The Platform attracted strong criticism from many sectors of the anarchist movement of the time, including some of the most influential anarchists such as Volin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

, Errico Malatesta, Luigi Fabbri, Camillo Berneri

Camillo Berneri (also known as Camillo da Lodi; May 28, 1897 – May 5, 1937) was an Italian professor of philosophy, anarchist militant, propagandist and theorist. He was married to Giovanna Berneri, and was father of Marie-Louise Berneri a ...

, Max Nettlau, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

, Emma Goldman, and Grigorii Maksimov. Malatesta, after initially opposing the Platform, later agreed with the Platform, confirming that the original difference of opinion was due to linguistic confusion: "I find myself more or less in agreement with their way of conceiving the anarchist organisation (being very far from the authoritarian spirit which the "Platform" seemed to reveal) and I confirm my belief that behind the linguistic differences really lie identical positions."

Two texts made by the anarchist communists

Two texts made by the anarchist communists Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

and Volin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

as responses to the Platform, each proposing different models, are the basis for what became known as the organization of synthesis, or simply synthesism. Volin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

published in 1924 a paper calling for "the anarchist synthesis" and was also the author of the article in Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

's on the same topic. The primary purpose behind the synthesis was that the anarchist movement in most countries was divided into three main tendencies: communist anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism, and individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean by individualism th ...

, and so such an organization could contain anarchists of these three tendencies very well. Faure, in his text "Anarchist synthesis", has the view that "these currents were not contradictory but complementary, each having a role within anarchism: anarcho-syndicalism as the strength of the mass organizations and the best way for the practice of anarchism; libertarian communism as a proposed future society based on the distribution of the fruits of labor according to the needs of each one; anarcho-individualism as a negation of oppression and affirming the individual right to development of the individual, seeking to please them in every way. The Dielo Truda platform in Spain also met with strong criticism. Miguel Jimenez, a founding member of the Iberian Anarchist Federation

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

(FAI), summarized this as follows: too much influence in it of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, it erroneously divided and reduced anarchists between individualist anarchists and anarcho-communist sections, and it wanted to unify the anarchist movement along the lines of the anarcho-communists. He saw anarchism as more complex than that, that anarchist tendencies are not mutually exclusive as the platformists saw it and that both individualist and communist views could accommodate anarchosyndicalism. Sébastian Faure had strong contacts in Spain, so his proposal had more impact on Spanish anarchists than the Dielo Truda platform, even though individualist anarchist influence in Spain was less intense than it was in France. The main goal there was reconciling anarcho-communism with anarcho-syndicalism.

Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze pointed out that during the early twentieth century, the terms ''libertarian communism'' and ''anarchist communism'' became synonymous within the international anarchist movement as a result of the close connection they had in Spain (see Anarchism in Spain

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of cl ...

) (with ''libertarian communism'' becoming the prevalent term).

Korean Anarchist Movement

The Korean Anarchist Movement in

The Korean Anarchist Movement in Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, led by Kim Chwa-chin

Kim Chwa-jin or Kim Jwa-jin (December 16, 1889 – January 24, 1930), sometimes called by his pen name Baegya, was a Korean general, independence activist, and anarchist who played an important role in the early attempts at development of anar ...

, briefly brought anarcho-communism to Korea. The success was short-lived and much less widespread than the anarchism in Spain. The Korean People's Association in Manchuria

The Korean People's Association in Manchuria (KPAM, August 1929 – September 1931) was an autonomous anarchist zone in Manchuria near the Korean borderlands, populated by two million Korean migrants. The society was constructed upon princip ...

had established a stateless, classless society where all means of production were run and operated by the workers, and all possessions were held in common by the community.

Spanish Revolution of 1936

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas (i.e., established around the ideas as they exist today and achieving worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon) happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.

Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionar ...

initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right-wing election victory. In 1936, the CNT changed its policy, and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

(1936–1939). In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and large areas of rural Spain, where they collectivized

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member ...

the land. However, even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. The events known as the Spanish Revolution was a workers' social revolution that began during the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

in 1936 and resulted in the widespread implementation of anarchist and, more broadly, libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (20 ...

organizational principles throughout various portions of the country for two to three years, primarily Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

, Aragon, Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The t ...

, and parts of the Levante. Much of Spain's economy was put under worker control; in anarchist strongholds like Catalonia, the figure was as high as 75%, but lower in areas with heavy Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain ( es, Partido Comunista de España; PCE) is a Marxist-Leninist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is part of Unidas Podemos. It currently has two of its politicians serving a ...

influence, as the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

-allied party actively resisted attempts at collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

enactment. Factories were run through worker committees, and agrarian areas became collectivized and ran as libertarian communes

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, relig ...

. Anarchist historian Sam Dolgoff

Sam Dolgoff (10 October 1902 – 15 October 1990) was an anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist from Russia who grew up and lived and was active in the United States.

Biography

Dolgoff was born in the shtetl of Ostrovno in Mogilev Governorate, ...

estimated that about eight million people participated directly or at least indirectly in the Spanish Revolution, which he claimed "came closer to realizing the ideal of the free stateless society on a vast scale than any other revolution in history". Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives and persecuted both dissident Marxists and anarchists.

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone

Although every sector of the stateless parts of Spain had undergone workers' self-management

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-management is a def ...

, collectivization of agricultural and industrial production, and in parts using money or some degree of private property, heavy regulation of markets by democratic communities, other areas throughout Spain used no money at all, and followed principles in accordance with "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs

"From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" (german: Jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen) is a slogan popularised by Karl Marx in his 1875 '' Critique of the Gotha Programme''. The principle ref ...

". One such example was the libertarian communist village of Alcora in the Valencian Community

The Valencian Community ( ca-valencia, Comunitat Valenciana, es, Comunidad Valenciana) is an autonomous community of Spain. It is the fourth most populous Spanish autonomous community after Andalusia, Catalonia and the Community of Madrid wi ...

, where money was absent, and the distribution of properties and services was done based upon needs, not who could afford them.

Post-war years

Anarcho-communism entered into internal debates over the organization issue in the post-World War II era. Founded in October 1935, the Anarcho-Communist Federation of Argentina (FACA, Federación Anarco-Comunista Argentina) in 1955 renamed itself the Argentine Libertarian Federation. The Fédération Anarchiste (FA) was founded in Paris on 2 December 1945 and elected the platformist anarcho-communist George Fontenis as its first secretary the following year. It was composed of a majority of activists from the former FA (which supportedVolin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

's Synthesis) and some members of the former Union Anarchiste, which supported the CNT-FAI support to the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War, as well as some young Resistants. In 1950 a clandestine group formed within the FA called Organisation Pensée Bataille (OPB), led by George Fontenis.Cédric Guérin. "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950–1970"/ref> The ''Manifesto of Libertarian Communism'' was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the ''Federation Communiste Libertaire'' of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current known as

platformism

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

. The OPB pushed for a move that saw the FA change its name to the (FCL) after the 1953 Congress in Paris, while an article in indicated the end of the cooperation with the French Surrealist

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to ...

Group led by André Breton.

The new decision-making process was founded on unanimity

Unanimity is agreement by all people in a given situation. Groups may consider unanimous decisions as a sign of social, political or procedural agreement, solidarity, and unity. Unanimity may be assumed explicitly after a unanimous vote or impli ...

: each person has a right of veto on the orientations of the federation. The FCL published the same year . Several groups quit the FCL in December 1955, disagreeing with the decision to present "revolutionary candidates" to the legislative elections. On 15–20 August 1954, the Ve intercontinental plenum of the CNT took place. A group called appeared, which was formed of militants who did not like the new ideological orientation that the OPB was giving the FCL seeing it was authoritarian and almost Marxist. The FCL lasted until 1956, just after participating in state legislative elections with ten candidates. This move alienated some members of the FCL and thus produced the end of the organization. A group of militants who disagreed with the FA turning into FCL reorganized a new Federation Anarchiste established in December 1953. This included those who formed ''L'Entente anarchiste,'' who joined the new FA and then dissolved L'Entente. The new base principles of the FA were written by the individualist anarchist Charles-Auguste Bontemps and the non-platformist anarcho-communist Maurice Joyeux

Maurice Joyeux (January 29, 1910 – December 9, 1991) was a French writer and anarchist. He first was a mechanic then a bookseller, he is a remarkable figure in the French Libertarianism movement. His father died as a social activist.

At 1928, ...

which established an organization with a plurality of tendencies and autonomy of groups organized around synthesist principles. According to historian Cédric Guérin, "the unconditional rejection of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

became from that moment onwards an identity element of the new Federation Anarchiste". This was motivated in a significant part by the previous conflict with George Fontenis and his OPB.

In Italy, the Italian Anarchist Federation was founded in 1945 in Carrara

Carrara ( , ; , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, in central Italy, of the province of Massa and Carrara, and notable for the white or blue-grey marble quarried there. It is on the Carrione River, some west-northwest of Florence. Its mot ...

. It adopted an "Associative Pact" and the "Anarchist Program" of Errico Malatesta. It decided to publish the weekly ''Umanità Nova

''Umanità Nova'' is an Italian anarchist newspaper founded in 1920.

It was published daily until 1922 when it was shut down by the fascist regime. In some places, its circulation exceeded that of the socialist paper '' Avanti!'' Upon the fal ...

,'' retaking the name of the journal published by Errico Malatesta. Inside the FAI, the Anarchist Groups of Proletarian Action (GAAP) was founded, led by Pier Carlo Masini, which "proposed a Libertarian Party with an anarchist theory and practice adapted to the new economic, political and social reality of post-war Italy, with an internationalist outlook and effective presence in the workplaces ..The GAAP allied themselves with the similar development within the French Anarchist movement", as led by George Fontenis. Another tendency that did not identify either with the more classical FAI or with the GAAP started to emerge as local groups. These groups emphasized direct action, informal affinity group

An affinity group is a group formed around a shared interest or common goal, to which individuals formally or informally belong. Affinity groups are generally precluded from being under the aegis of any governmental agency, and their purposes m ...

s, and expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

for financing anarchist activity. From within these groups, the influential insurrectionary anarchist Alfredo Maria Bonanno will emerge influenced by the practice of the Spanish exiled anarchist José Lluis Facerías. In the early seventies, a platformist tendency emerged within the Italian Anarchist Federation, which argued for more strategic coherence and social insertion in the workers' movement while rejecting the synthesist "Associative Pact" of Malatesta Malatesta may refer to:

People Given name

* Malatesta (I) da Verucchio (1212–1312), founder of the powerful Italian Malatesta family and a famous condottiero

* Malatesta IV Baglioni (1491–1531), Italian condottiero and lord of Perugia, Bettona, ...

, which the FAI adhered to. These groups started organizing themselves outside the FAI in organizations such as O.R.A. from Liguria

it, Ligure

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, which organized a Congress attended by 250 delegates of groups from 60 locations. This movement was influential in the movements of the seventies. They published in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

and from Modena. The Federation of Anarchist Communists

The Alternativa Libertaria/FdCA is a Platformism, platformist anarchist political organisation in Italy. It was originally established in 1985 through the fusion of the Revolutionary Anarchist Organisation ( it, Organizzazione Rivoluzionaria Anarc ...

(), or FdCA, was established in 1985 in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

from the fusion of the (''Revolutionary Anarchist Organisation'') and the ('' Tuscan Union of Anarchist Communists'').

The International of Anarchist Federations

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisa ...

(IAF/IFA) was founded during an international anarchist conference in Carrara

Carrara ( , ; , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, in central Italy, of the province of Massa and Carrara, and notable for the white or blue-grey marble quarried there. It is on the Carrione River, some west-northwest of Florence. Its mot ...

in 1968 by the three existing European anarchist federations of France (), Italy (), and Spain () as well as the Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...