Lepus europaeus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The European hare (''Lepus europaeus''), also known as the brown hare, is a

The European hare was first described in 1778 by German zoologist

The European hare was first described in 1778 by German zoologist

The European hare, like other members of the

The European hare, like other members of the

The European hare is native to much of

The European hare is native to much of

The European hare is primarily

The European hare is primarily

The European hare is primarily

The European hare is primarily  European hares forage in groups. Group feeding is beneficial as individuals can spend more time feeding knowing that other hares are being vigilant. Nevertheless, the distribution of food affects these benefits. When food is well-spaced, all hares are able to access it. When food is clumped together, only dominant hares can access it. In small gatherings, dominants are more successful in defending food, but as more individuals join in, they must spend more time driving off others. The larger the group, the less time dominant individuals have in which to eat. Meanwhile, the subordinates can access the food while the dominants are distracted. As such, when in groups, all individuals fare worse when food is clumped as opposed to when it is widely spaced.

European hares forage in groups. Group feeding is beneficial as individuals can spend more time feeding knowing that other hares are being vigilant. Nevertheless, the distribution of food affects these benefits. When food is well-spaced, all hares are able to access it. When food is clumped together, only dominant hares can access it. In small gatherings, dominants are more successful in defending food, but as more individuals join in, they must spend more time driving off others. The larger the group, the less time dominant individuals have in which to eat. Meanwhile, the subordinates can access the food while the dominants are distracted. As such, when in groups, all individuals fare worse when food is clumped as opposed to when it is widely spaced.

Does give birth in hollow depressions in the ground. An individual female may have three litters in a year with a 41- to 42-day gestation period. The young have an average weight of around at birth. The leverets are fully furred and are precocial, being ready to leave the nest soon after they are born, an adaptation to the lack of physical protection relative to that afforded by a burrow. Leverets disperse during the day and come together in the evening close to where they were born. Their mother visits them for nursing soon after sunset; the young suckle for around five minutes, urinating while they do so, with the doe licking up the fluid. She then leaps away so as not to leave an olfactory trail, and the leverets disperse once more. Young can eat solid food after two weeks and are weaned when they are four weeks old. While young of either sex commonly explore their surroundings, natal dispersal tends to be greater in males. Sexual maturity occurs at seven or eight months for females and six months for males.

Does give birth in hollow depressions in the ground. An individual female may have three litters in a year with a 41- to 42-day gestation period. The young have an average weight of around at birth. The leverets are fully furred and are precocial, being ready to leave the nest soon after they are born, an adaptation to the lack of physical protection relative to that afforded by a burrow. Leverets disperse during the day and come together in the evening close to where they were born. Their mother visits them for nursing soon after sunset; the young suckle for around five minutes, urinating while they do so, with the doe licking up the fluid. She then leaps away so as not to leave an olfactory trail, and the leverets disperse once more. Young can eat solid food after two weeks and are weaned when they are four weeks old. While young of either sex commonly explore their surroundings, natal dispersal tends to be greater in males. Sexual maturity occurs at seven or eight months for females and six months for males.

European hares are large leporids and adults can only be tackled by large predators such as

European hares are large leporids and adults can only be tackled by large predators such as

Any connection of the hare to Ēostre is doubtful. John Andrew Boyle cites an etymology dictionary by A. Ernout and A. Meillet, who wrote that the lights of Ēostre were carried by hares, that Ēostre represented spring

Any connection of the hare to Ēostre is doubtful. John Andrew Boyle cites an etymology dictionary by A. Ernout and A. Meillet, who wrote that the lights of Ēostre were carried by hares, that Ēostre represented spring

Across Europe, over five million European hares are shot each year, making it probably the most important game mammal on the continent. This popularity has threatened regional varieties such as those of France and Denmark, through large-scale importing of hares from Eastern European countries such as Hungary. Hares have traditionally been hunted in Britain by

Across Europe, over five million European hares are shot each year, making it probably the most important game mammal on the continent. This popularity has threatened regional varieties such as those of France and Denmark, through large-scale importing of hares from Eastern European countries such as Hungary. Hares have traditionally been hunted in Britain by

The European hare has a wide range across Europe and western Asia and has been introduced to a number of other countries around the globe, often as a game species. In general it is considered moderately abundant in its native range, but declines in populations have been noted in many areas since the 1960s. These have been associated with the intensification of agricultural practices. The hare is an adaptable species and can move into new habitats, but it thrives best when there is an availability of a wide variety of weeds and other herbs to supplement its main diet of grasses. The hare is considered a pest in some areas; it is more likely to damage crops and young trees in winter when there are not enough alternative foodstuffs available.

The

The European hare has a wide range across Europe and western Asia and has been introduced to a number of other countries around the globe, often as a game species. In general it is considered moderately abundant in its native range, but declines in populations have been noted in many areas since the 1960s. These have been associated with the intensification of agricultural practices. The hare is an adaptable species and can move into new habitats, but it thrives best when there is an availability of a wide variety of weeds and other herbs to supplement its main diet of grasses. The hare is considered a pest in some areas; it is more likely to damage crops and young trees in winter when there are not enough alternative foodstuffs available.

The

ARKive

Photographs Videos

BBC Wales Nature: Brown hare article

BBC Wales Nature: Brown hare

Brown hare and new vegetation

{{Authority control Lepus Hare, European Hare, European Introduced mammals of Australia Mammals of New Zealand Mammals of Grenada Mammals of Barbados Mammals of Guadeloupe Mammals of the Caribbean Fauna of the Falkland Islands Least concern biota of Asia Least concern biota of Europe Mammals described in 1778 Taxa named by Peter Simon Pallas

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

native to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and parts of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

. It is among the largest hare species and is adapted to temperate, open country. Hares are herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

and feed mainly on grasses and herbs, supplementing these with twigs, buds, bark and field crops, particularly in winter. Their natural predators

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

include large birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

, canids

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found within th ...

and felid

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the dom ...

s. They rely on high-speed endurance running to escape predation, having long, powerful limbs and large nostrils.

Generally nocturnal and shy in nature, hares change their behaviour in the spring, when they can be seen in broad daylight chasing one another around in fields. During this spring frenzy, they sometimes strike one another with their paws ("boxing"). This is usually not competition between males, but a female hitting a male, either to show she is not yet ready to mate or to test his determination. The female nests in a depression on the surface of the ground rather than in a burrow

An Eastern chipmunk at the entrance of its burrow

A burrow is a hole or tunnel excavated into the ground by an animal to construct a space suitable for habitation or temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion. Burrows provide a form of sh ...

and the young are active as soon as they are born. Litters may consist of three or four young and a female can bear three litters a year, with hares living for up to twelve years. The breeding season lasts from January to August.

The European hare is listed as being of least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

because it has a wide range and is moderately abundant. However, populations have been declining in mainland Europe since the 1960s, at least partly due to changes in farming practices. The hare has been hunted across Europe for centuries, with more than five million being shot each year; in Britain, it has traditionally been hunted by beagling

Beagling is the hunting mainly of hares and also rabbits, by beagles by scent. A beagle pack (10 or more hounds) is usually followed on foot, but in a few cases mounted. Beagling is often enjoyed by 'retired' fox hunters who have either sustained ...

and hare coursing

Hare coursing is the pursuit of hares with greyhounds and other sighthounds, which chase the hare by sight, not by scent.

In some countries, it is a legal, competitive activity in which dogs are tested on their ability to run, overtake and tur ...

, but these field sports

Field sports are outdoor sports that take place in the wilderness or sparsely populated rural areas, where there are vast areas of uninhabited greenfields. The term specifically refer to activities that mandate sufficiently large open spaces an ...

are now illegal. The hare has been a traditional symbol of fertility

Fertility is the capability to produce offspring through reproduction following the onset of sexual maturity. The fertility rate is the average number of children born by a female during her lifetime and is quantified demographically. Fertili ...

and reproduction in some cultures and its courtship behaviour in the spring inspired the English idiom ''mad as a March hare

To be as "mad as a March hare" is an English idiomatic phrase derived from the observed antics, said to occur only in the March breeding season of the European hare (''Lepus europaeus''). The phrase is an allusion that can be used to refer to any ...

''.

Taxonomy and genetics

The European hare was first described in 1778 by German zoologist

The European hare was first described in 1778 by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (22 September 1741 – 8 September 1811) was a Prussian zoologist and botanist who worked in Russia between 1767 and 1810.

Life and work

Peter Simon Pallas was born in Berlin, the son ...

. It shares the genus ''Lepus

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The gen ...

'' (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "hare") with 32 other hare and jackrabbit species, jackrabbits being the name given to some species of hare native to North America. They are distinguished from other leporid

Leporidae is the family of rabbits and hares, containing over 60 species of extant mammals in all. The Latin word ''Leporidae'' means "those that resemble ''lepus''" (hare). Together with the pikas, the Leporidae constitute the mammalian order ...

s (hares and rabbits) by their longer legs and wider nostrils. The Corsican hare

The Corsican hare (''Lepus corsicanus''), also known as the Apennine hare or Italian hare, is a species of hare found in southern and central Italy and Corsica.

Taxonomy

It was first described as a species in 1898 by the British zoologist William ...

, broom hare

The broom hare (''Lepus castroviejoi'') is a species of hare endemic (ecology), endemic to northern Spain. Distribution and habitat

It is restricted to the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Spain between the Serra dos Ancares and the Sierra de P ...

and Granada hare

The Granada hare (''Lepus granatensis''), also known as the Iberian hare, is a hare species that can be found on the Iberian Peninsula and on the island of Majorca.

Subspecies

Three subspecies of the Granada hare are known, which vary in colour ...

were at one time considered to be subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

of the European hare, but DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

and morphological analysis support their status as separate species.

There is some debate as to whether the European hare and the Cape hare

The Cape hare (''Lepus capensis''), also called the brown hare and the desert hare, is a hare native to Africa and Arabia extending into India.

Taxonomy

The Cape hare was one of the many mammal species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in ...

are the same species. A 2005 nuclear gene

A nuclear gene is a gene whose physical DNA nucleotide sequence is located in the cell nucleus of a eukaryote. The term is used to distinguish nuclear genes from genes found in mitochondria or chloroplasts. The vast majority of genes in eukaryote ...

pool study suggested that they are, but a 2006 study of the mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

of these same animals concluded that they had diverged sufficiently widely to be considered separate species. A 2008 study claims that in the case of ''Lepus'' species, with their rapid evolution, species designation cannot be based solely on mtDNA but should also include an examination of the nuclear gene pool. It is possible that the genetic differences between the European and Cape hare are due to geographic separation rather than actual divergence. It has been speculated that in the Near East, hare populations are intergrading and experiencing gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

. Another 2008 study suggests that more research is needed before a conclusion is reached as to whether a species complex

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

exists; the European hare remains classified as a single species until further data contradicts this assumption.

Cladogenetic analysis suggests that European hares survived the last glacial period during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

via refugia in southern Europe ( Italian peninsula and Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

) and Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Subsequent colonisations of Central Europe appear to have been initiated by human-caused environmental changes. Genetic diversity in current populations is high with no signs of inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

. Gene flow appears to be biased towards males, but overall populations are matrilineally

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

structured. There appears to be a particularly large degree of genetic diversity in hares in the North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a States of Germany, state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more tha ...

region of Germany. It is however possible that restricted gene flow could reduce genetic diversity within populations that become isolated.

Historically, up to 30 subspecies of European hare have been described, although their status has been disputed. These subspecies have been distinguished by differences in pelage colouration, body size, external body measurements, skull morphology and tooth shape.

Sixteen subspecies are listed in the IUCN red book, following Hoffmann and Smith (2005):

Twenty-nine subspecies of "very variable status" are listed by Chapman and Flux in their book on lagomorphs, including the subspecies above (with the exceptions of ''L. e. connori'', ''L. e. creticus'', ''L. e. cyprius'', ''L. e. judeae'', ''L. e. rhodius'', and ''L. e. syriacus'') and additionally:

Description

The European hare, like other members of the

The European hare, like other members of the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Leporidae

Leporidae is the family of rabbits and hares, containing over 60 species of extant mammals in all. The Latin word ''Leporidae'' means "those that resemble ''lepus''" (hare). Together with the pikas, the Leporidae constitute the mammalian order ...

, is a fast-running terrestrial mammal; it has eyes set high on the sides of its head, long ears and a flexible neck. Its teeth grow continuously, the first incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, whe ...

s being modified for gnawing while the second incisors are peg-like and non-functional. There is a gap (diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

) between the incisors and the cheek teeth, the latter being adapted for grinding coarse plant material. The dental formula is 2/1, 0/0, 3/2, 3/3. The dark limb musculature of hares is adapted for high-speed endurance running in open country. By contrast, cottontail rabbit

Cottontail rabbits are the leporid species in the genus ''Sylvilagus'', found in the Americas. Most ''Sylvilagus'' species have stub tails with white undersides that show when they retreat, giving them their characteristic name. However, this ...

s are built for short bursts of speed in more vegetated habitats. Other adaptions for high speed running in hares include wider nostrils and larger hearts. In comparison to the European rabbit

The European rabbit (''Oryctolagus cuniculus'') or coney is a species of rabbit native to the Iberian Peninsula (including Spain, Portugal, and southwestern France), western France, and the northern Atlas Mountains in northwest Africa. It has ...

, the hare has a proportionally smaller stomach and caecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The w ...

.

This hare is one of the largest of the lagomorphs

The lagomorphs are the members of the taxonomic order Lagomorpha, of which there are two living families: the Leporidae ( hares and rabbits) and the Ochotonidae (pikas). The name of the order is derived from the Ancient Greek ''lagos'' (λα� ...

. Its head and body length can range from with a tail length of . The body mass is typically between . The hare's elongated ears range from from the notch to tip. It also has long hind feet that have a length of between . The skull has nasal bones that are short, but broad and heavy. The supraorbital ridge

The brow ridge, or supraorbital ridge known as superciliary arch in medicine, is a bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates. In humans, the eyebrows are located on their lower margin.

Structure

The brow ridge is a nodule or crest ...

has well-developed anterior and posterior lobes and the lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bone is a small and fragile bone of the facial skeleton; it is roughly the size of the little fingernail. It is situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. It has two surfaces and four borders. Several bony landmarks of ...

projects prominently from the anterior wall of the orbit.

The fur colour is grizzled yellow-brown on the back; rufous

Rufous () is a color that may be described as reddish-brown or brownish-red, as of rust or oxidised iron. The first recorded use of ''rufous'' as a color name in English was in 1782. However, the color is also recorded earlier in 1527 as a dia ...

on the shoulders, legs, neck and throat; white on the underside and black on the tail and ear tips. The fur on the back is typically longer and more curled than on the rest of the body. The European hare's fur does not turn completely white in the winter as is the case with some other members of the genus, although the sides of the head and base of the ears do develop white areas and the hip and rump region may gain some grey.

Distribution and habitat

continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

and part of Asia. Its range extends from northern Spain to southern Scandinavia, eastern Europe, and northern parts of Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

. It has been extending its range into Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. It may have been introduced to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

about 2000 years ago, based on a lack of archaeological evidence before that. It is not present in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, where the mountain hare

The mountain hare (''Lepus timidus''), also known as blue hare, tundra hare, variable hare, white hare, snow hare, alpine hare, and Irish hare, is a Palearctic hare that is largely adapted to polar and mountainous habitats.

Evolution

The mountai ...

is the only native hare species. Undocumented introductions probably occurred in some Mediterranean Islands. It has also been introduced, mostly as game animal

Game or quarry is any wild animal hunted for animal products (primarily meat), for recreation (" sporting"), or for trophies. The species of animals hunted as game varies in different parts of the world and by different local jurisdictions, thou ...

, to North America in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

and New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. stat ...

, and unsuccessfully in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, the Southern Cone

The Southern Cone ( es, Cono Sur, pt, Cone Sul) is a geographical and cultural subregion composed of the southernmost areas of South America, mostly south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Traditionally, it covers Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, bou ...

in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

and the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, both islands of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

and the south Pacific coast of Russia.

The European hare primarily lives in open fields with scattered brush for shelter. It is very adaptable and thrives in mixed farmland. According to a study in the Czech Republic, the mean hare densities were highest at elevations below , 40 to 60 days of annual snow cover, of annual precipitation, and a mean annual air temperature of around . With regards to climate, the European hare density was highest in "warm and dry districts with mild winters". In Poland, the European hare is most abundant in areas with few forest edges, perhaps because foxes can use these for cover. It requires cover, such as hedges, ditches and permanent cover areas, because these habitats supply the varied diet it requires, and are found at lower densities in large open fields. Intensive cultivation of the land results in greater mortality of young hares.

In Great Britain, the European hare is seen most frequently on arable farms, especially those with crop rotation

Crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. It reduces reliance on one set of nutrients, pest and weed pressure, and the probability of developing resistant ...

and fallow

Fallow is a farming technique in which arable land is left without sowing for one or more vegetative cycles. The goal of fallowing is to allow the land to recover and store organic matter while retaining moisture and disrupting pest life cycles ...

land, wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

and sugar beet

A sugar beet is a plant whose root contains a high concentration of sucrose and which is grown commercially for sugar production. In plant breeding, it is known as the Altissima cultivar group of the common beet (''Beta vulgaris''). Together wi ...

crops. In mainly grass farms, its numbers increased with are improved pastures, some arable crops and patches of woodland. It is seen less frequently where foxes are abundant or where there are many common buzzard

The common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'') is a medium-to-large bird of prey which has a large range. A member of the genus ''Buteo'', it is a member of the family Accipitridae. The species lives in most of Europe and extends its breeding range across ...

s. It also seems to be fewer in number in areas with high European rabbit populations, although there appears to be little interaction between the two species and no aggression. Although European hares are shot as game when plentiful, this is a self-limiting activity and is less likely to occur in localities where the species is scarce.

Behaviour and life history

The European hare is primarily

The European hare is primarily nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

and spends a third of its time foraging

Foraging is searching for wild food resources. It affects an animal's Fitness (biology), fitness because it plays an important role in an animal's ability to survive and reproduce. Optimal foraging theory, Foraging theory is a branch of behaviora ...

. During daytime, it hides in a depression in the ground called a "form" where it is partially hidden. It can run at , and when confronted by predators it relies on outrunning them in the open. It is generally thought of as asocial but can be seen in both large and small groups. It does not appear to be territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

, living in shared home range

A home range is the area in which an animal lives and moves on a periodic basis. It is related to the concept of an animal's territory which is the area that is actively defended. The concept of a home range was introduced by W. H. Burt in 1943. He ...

s of around . It communicates with each other by a variety of visual signals. To show interest it raises its ears, while lowering the ears warns others to keep away. When challenging a conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organ ...

, a hare thumps its front feet; the hind feet are used to warn others of a predator. It squeals when hurt or scared, and a female makes "guttural

Guttural speech sounds are those with a primary place of articulation near the back of the oral cavity, especially where it's difficult to distinguish a sound's place of articulation and its phonation. In popular usage it is an imprecise term for s ...

" calls to attract her young. It can live for as long as twelve years.

Food and foraging

The European hare is primarily

The European hare is primarily herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

and forages for wild grasses and weeds. With the intensification of agriculture, it has taken to feeding on crops when preferred foods are not available. During the spring and summer, it feeds on soy

The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean (''Glycine max'') is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include soy milk, from which tofu and ...

, clover

Clover or trefoil are common names for plants of the genus ''Trifolium'' (from Latin ''tres'' 'three' + ''folium'' 'leaf'), consisting of about 300 species of flowering plants in the legume or pea family Fabaceae originating in Europe. The genus ...

and corn poppy

''Papaver rhoeas'', with common names including common poppy, corn poppy, corn rose, field poppy, Flanders poppy, and red poppy, is an annual herbaceous species of flowering plant in the poppy family Papaveraceae. It is a temperate native with a ...

as well as grasses and herbs. During autumn and winter, it primarily chooses winter wheat

Winter wheat (usually ''Triticum aestivum'') are strains of wheat that are planted in the autumn to germinate and develop into young plants that remain in the vegetative phase during the winter and resume growth in early spring. Classification ...

, and is also attracted to piles of sugar beet and carrots provided by hunters. It also eats twigs, buds and the bark of shrubs and young fruit trees during winter. It avoids cereal

A cereal is any Poaceae, grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, Cereal germ, germ, and bran. Cereal Grain, grain crops are grown in greater quantit ...

crops when other more attractive foods are available, and appears to prefer high energy foodstuffs over crude dietary fiber

Dietary fiber (in British English fibre) or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by the ...

. When eating twigs, it strips off the bark to access the vascular tissues which store soluble carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ma ...

s. Compared to the European rabbit, food passes through the gut more rapidly in the European hare, although digestion rates are similar. It is sometimes coprophagia

Coprophagia () or coprophagy () is the consumption of feces. The word is derived from the grc, κόπρος , "feces" and , "to eat". Coprophagy refers to many kinds of feces-eating, including eating feces of other species (heterospecifics), o ...

l eating its own green, faecal pellets to recover undigested proteins and vitamins. Two to three adult hares can eat more food than a single sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

.

Mating and reproduction

European hares have a prolonged breeding season which lasts from January to August. Females, or does, can be found pregnant in all breeding months and males, or bucks, are fertile all year round except during October and November. After this hiatus, the size and activity of the males' testes increase, signalling the start of a new reproductive cycle. This continues through December, January and February when the reproductive tract gains back its functionality. Matings start beforeovulation

Ovulation is the release of eggs from the ovaries. In women, this event occurs when the ovarian follicles rupture and release the secondary oocyte ovarian cells. After ovulation, during the luteal phase, the egg will be available to be fertilized ...

occurs and the first pregnancies of the year often result in a single foetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal develo ...

, with pregnancy failures being common. Peak reproductive activity occurs in March and April, when all females may be pregnant, the majority with three or more foetuses.

The mating system of the hare has been described as both polygynous

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

(single males mating with multiple females) and promiscuous

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different Sexual partner, partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as pro ...

. Females have six-weekly reproductive cycles and are receptive for only a few hours at a time, making competition among local bucks intense. At the height of the breeding season, this phenomenon is known as "March madness", when the normally nocturnal bucks are forced to be active in the daytime. In addition to dominant animals subduing subordinates, the female fights off her numerous suitors if she is not ready to mate. Fights can be vicious and can leave numerous scars on the ears. In these encounters, hares stand upright and attack each other with their paws, a practice known as "boxing", and this activity is usually between a female and a male and not between competing males as was previously believed. When a doe is ready to mate, she runs across the countryside, starting a chase that tests the stamina of the following males. When only the fittest male remains, the female stops and allows him to copulate. Female fertility continues through May, June and July, but testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone and anabolic steroid in males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testes and prostate, as well as promoting secondar ...

production decreases in males and sexual behaviour becomes less overt. Litter sizes decrease as the breeding season draws to a close with no pregnancies occurring after August. The testes of males begin to regress and sperm production ends in September.

Does give birth in hollow depressions in the ground. An individual female may have three litters in a year with a 41- to 42-day gestation period. The young have an average weight of around at birth. The leverets are fully furred and are precocial, being ready to leave the nest soon after they are born, an adaptation to the lack of physical protection relative to that afforded by a burrow. Leverets disperse during the day and come together in the evening close to where they were born. Their mother visits them for nursing soon after sunset; the young suckle for around five minutes, urinating while they do so, with the doe licking up the fluid. She then leaps away so as not to leave an olfactory trail, and the leverets disperse once more. Young can eat solid food after two weeks and are weaned when they are four weeks old. While young of either sex commonly explore their surroundings, natal dispersal tends to be greater in males. Sexual maturity occurs at seven or eight months for females and six months for males.

Does give birth in hollow depressions in the ground. An individual female may have three litters in a year with a 41- to 42-day gestation period. The young have an average weight of around at birth. The leverets are fully furred and are precocial, being ready to leave the nest soon after they are born, an adaptation to the lack of physical protection relative to that afforded by a burrow. Leverets disperse during the day and come together in the evening close to where they were born. Their mother visits them for nursing soon after sunset; the young suckle for around five minutes, urinating while they do so, with the doe licking up the fluid. She then leaps away so as not to leave an olfactory trail, and the leverets disperse once more. Young can eat solid food after two weeks and are weaned when they are four weeks old. While young of either sex commonly explore their surroundings, natal dispersal tends to be greater in males. Sexual maturity occurs at seven or eight months for females and six months for males.

Health and mortality

European hares are large leporids and adults can only be tackled by large predators such as

European hares are large leporids and adults can only be tackled by large predators such as canids

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found within th ...

, felids

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the do ...

and the largest birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

. In Poland it was found that the consumption of hares by foxes was at its highest during spring, when the availability of small animal prey was low; at this time of year, hares may constitute up to 50% of the biomass eaten by foxes, with 50% of the mortality of adult hares being caused by their predation. In Scandinavia, a natural epizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "epi ...

of sarcoptic mange

Mange is a type of skin disease caused by parasitic mites. Because various species of mites also infect plants, birds and reptiles, the term "mange", or colloquially "the mange", suggesting poor condition of the skin and fur due to the infection ...

which reduced the population of red foxes dramatically, resulted in an increase in the number of European hares, which returned to previous levels when the numbers of foxes subsequently increased. The golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

preys on the European hare in the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

, the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Ural Mountains, Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The ...

, the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

and northern Spain. In North America, foxes and coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecologica ...

s are probably the most common predators, with bobcat

The bobcat (''Lynx rufus''), also known as the red lynx, is a medium-sized cat native to North America. It ranges from southern Canada through most of the contiguous United States to Oaxaca in Mexico. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUC ...

s and lynx

A lynx is a type of wild cat.

Lynx may also refer to:

Astronomy

* Lynx (constellation)

* Lynx (Chinese astronomy)

* Lynx X-ray Observatory, a NASA-funded mission concept for a next-generation X-ray space observatory

Places Canada

* Lynx, Ontar ...

also preying on them in more remote locations.

European hares have both external and internal parasites. One study found that 54% of animals in Slovakia were parasitised by nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

s and over 90% by coccidia

Coccidia (Coccidiasina) are a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class Conoidasida.

As obligate intracellular parasites, they must live and reproduce within an a ...

. In Australia, European hares were reported as being infected by four species of nematode, six of coccidian, several liver fluke

Liver fluke is a collective name of a polyphyletic group of parasitic trematodes under the phylum Platyhelminthes.

They are principally parasites of the liver of various mammals, including humans. Capable of moving along the blood circulation, t ...

s and two canine tapeworms

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, known as tapeworms. Their bodies consist of man ...

. They were also found to host rabbit fleas (''Spilopsyllus cuniculi''), stickfast fleas (''Echidnophaga myrmecobii''), lice ('' Haemodipsus setoni'' and '' H. lyriocephalus''), and mites ('' Leporacarus gibbus'').

European brown hare syndrome (EBHS) is a disease caused by a calicivirus

The ''Caliciviridae'' are a family of "small round structured" viruses, members of Class IV of the Baltimore scheme. Caliciviridae bear resemblance to enlarged picornavirus and was formerly a separate genus within the picornaviridae. They are p ...

similar to that causing rabbit haemorrhagic disease

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD), also known as viral hemorrhagic disease (VHD), is a highly infectious and lethal form of viral hepatitis that affects European rabbits. Some viral strains also affect hares and cottontail rabbits. Mortality rate ...

(RHD) and can similarly be fatal, but cross infection between the two mammal species does not occur. Other threats to the hare are pasteurellosis

Pasteurellosis is an infection with a species of the bacterial genus ''Pasteurella'', which is found in humans and other animals.

''Pasteurella multocida'' (subspecies ''P. m. septica'' and ''P. m. multocida'') is carried in the mouth and respir ...

, yersiniosis

Yersiniosis is an infectious disease caused by a bacterium of the genus ''Yersinia''. In the United States, most yersiniosis infections among humans are caused by ''Yersinia enterocolitica''.

Infection with '' Y. enterocolitica'' occurs most o ...

(pseudo-tuberculosis), coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is a parasitic disease of the intestinal tract of animals caused by coccidian protozoa. The disease spreads from one animal to another by contact with infected feces or ingestion of infected tissue. Diarrhea, which may become bloody in ...

and tularaemia

Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever, is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium ''Francisella tularensis''. Symptoms may include fever, skin ulcers, and enlarged lymph nodes. Occasionally, a form that results in pneumonia or a throat infe ...

, which are the principal sources of mortality.

In October 2018, it was reported that a mutated form of the rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV2) may have jumped to hares in the UK. Normally rare in hares, a significant die-off from the virus has also occurred in Spain.

Relationship with humans

In folklore, literature, and art

In Europe, the hare has been a symbol of sex and fertility since at leastAncient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. The Greeks associated it with the gods Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

, Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols include ...

and Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

as well as with satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, :wikt:σάτυρος, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, :wikt:Σειληνός, σειληνός ), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears ...

s and cupid

In classical mythology, Cupid (Latin Cupīdō , meaning "passionate desire") is the god of desire, lust, erotic love, attraction and affection. He is often portrayed as the son of the love goddess Venus (mythology), Venus and the god of war Mar ...

s. The Christian Church connected the hare with lustfulness and homosexuality, but also associated it with the persecution of the church because of the way it was commonly hunted.

In Northern Europe, Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

imagery often involves hares or rabbits. Citing folk Easter customs

Since its origins, Easter has been a time of celebration and feasting and many traditional Easter games and customs developed, such as egg rolling, egg tapping, pace egging, cascarones or confetti eggs and egg decorating. Today Easter is commer ...

in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, England, where "the profits of the land called Harecrop Leys were applied to providing a meal which was thrown on the ground at the 'Hare-pie Bank'", the 19th-century scholar Charles Isaac Elton

Charles Isaac Elton, QC (6 December 1839 – 23 April 1900) was an English lawyer, antiquary, and politician.

He is most famous for being one of the authors of the bestselling book '' The Great Book-Collectors''.

He was born in Southampton. ...

proposed a possible connection between these customs and the worship of Ēostre

() is a West Germanic spring goddess. The name is reflected in ang, *Ēastre (; Northumbrian dialect: ', Mercian and West Saxon dialects: ' ),Sievers 1901 p. 98 Barnhart, Robert K. ''The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology'' (1995) ...

. In his 19th-century study of the hare in folk custom and mythology, Charles J. Billson Charles James Billson (1858–1932) was a translator, lawyer, and collector of folklore.

Billson was born in Leicester, graduated from Oxford University, and died in Heathfield in Sussex. He is buried in All Saints Church yard.

His works include ...

cites folk customs involving the hare around Easter in Northern Europe, and argues that the hare was probably a sacred animal in prehistoric Britain's festival of springtime. Observation of the hare's springtime mating behaviour led to the popular English idiom "mad as a March hare

To be as "mad as a March hare" is an English idiomatic phrase derived from the observed antics, said to occur only in the March breeding season of the European hare (''Lepus europaeus''). The phrase is an allusion that can be used to refer to any ...

", with similar phrases from the sixteenth century writings of John Skelton John Skelton may refer to:

*John Skelton (poet) (c.1460–1529), English poet.

* John de Skelton, MP for Cumberland (UK Parliament constituency)

*John Skelton (died 1439), MP for Cumberland (UK Parliament constituency)

*John Skelton (American footb ...

and Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

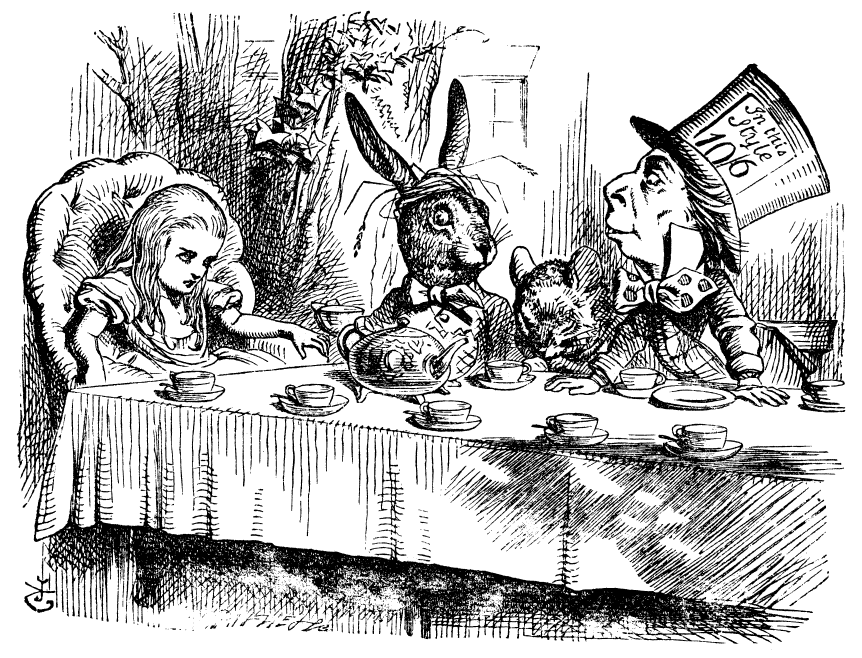

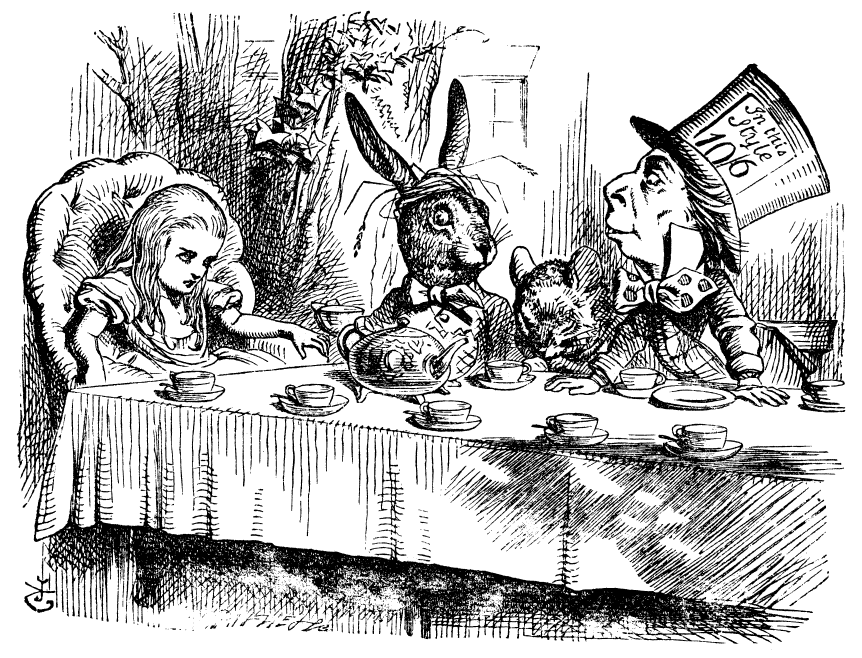

onwards. The mad hare reappears in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland), Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a ...

'' by Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

, in which Alice participates in a crazy tea-party with the March Hare

The March Hare (called Haigha in ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a character most famous for appearing in the tea party scene in Lewis Carroll's 1865 book ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''.

The main character, Alice, hypothesizes,

: "Th ...

and the Hatter

Hat-making or millinery is the design, manufacture and sale of hats and other headwear. A person engaged in this trade is called a milliner or hatter.

Historically, milliners, typically women shopkeepers, produced or imported an inventory of g ...

.

Any connection of the hare to Ēostre is doubtful. John Andrew Boyle cites an etymology dictionary by A. Ernout and A. Meillet, who wrote that the lights of Ēostre were carried by hares, that Ēostre represented spring

Any connection of the hare to Ēostre is doubtful. John Andrew Boyle cites an etymology dictionary by A. Ernout and A. Meillet, who wrote that the lights of Ēostre were carried by hares, that Ēostre represented spring fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the natural capability to pr ...

, love and sexual pleasure. Boyle responds that almost nothing is known about Ēostre, and that the authors had seemingly accepted the identification of Ēostre with the Norse goddess Freyja

In Norse paganism, Freyja (Old Norse "(the) Lady") is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr (magic for seeing and influencing the future). Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chario ...

, but that the hare is not associated with Freyja either. Boyle adds that "when the authors speak of the hare as the 'companion of Aphrodite and of satyrs and cupids' and 'in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

he hare

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

appears beside the figure of ythologicalLuxuria', they are on much surer ground."

The hare is a character in some fables, such as ''The Tortoise and the Hare

"The Tortoise and the Hare" is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 226 in the Perry Index. The account of a race between unequal partners has attracted conflicting interpretations. The fable itself is a variant of a common folktale theme in wh ...

'' of Aesop

Aesop ( or ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE) was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales cre ...

. The story was annexed to a philosophical problem by Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea (; grc, Ζήνων ὁ Ἐλεᾱ́της; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher of Magna Graecia and a member of the Eleatic School founded by Parmenides. Aristotle called him the inventor of the dialectic. He is best known fo ...

, who created a set of paradoxes to support Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

' attack on the idea of continuous motion, as each time the hare (or the hero Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, k ...

) moves to where the tortoise was, the tortoise moves just a little further away. The German Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

artist Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer (; ; hu, Ajtósi Adalbert; 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528),Müller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Dürers'', Walter de Gruyter. . sometimes spelled in English as Durer (without an umlaut) or Due ...

realistically depicted a hare in his 1502 watercolour painting ''Young Hare

''Young Hare'' (german: Feldhase) is a 1502 watercolor painting, watercolour and gouache, bodycolour painting by German artist Albrecht Dürer. Painted in 1502 in his workshop, it is acknowledged as a masterpiece of observational art alongside ...

''.

Food and hunting

Across Europe, over five million European hares are shot each year, making it probably the most important game mammal on the continent. This popularity has threatened regional varieties such as those of France and Denmark, through large-scale importing of hares from Eastern European countries such as Hungary. Hares have traditionally been hunted in Britain by

Across Europe, over five million European hares are shot each year, making it probably the most important game mammal on the continent. This popularity has threatened regional varieties such as those of France and Denmark, through large-scale importing of hares from Eastern European countries such as Hungary. Hares have traditionally been hunted in Britain by beagling

Beagling is the hunting mainly of hares and also rabbits, by beagles by scent. A beagle pack (10 or more hounds) is usually followed on foot, but in a few cases mounted. Beagling is often enjoyed by 'retired' fox hunters who have either sustained ...

and hare coursing

Hare coursing is the pursuit of hares with greyhounds and other sighthounds, which chase the hare by sight, not by scent.

In some countries, it is a legal, competitive activity in which dogs are tested on their ability to run, overtake and tur ...

. In beagling, the hare is hunted with a pack of small hunting dogs, beagle

The beagle is a breed of small scent hound, similar in appearance to the much larger foxhound. The beagle was developed primarily for hunting hare, known as beagling. Possessing a great sense of smell and superior tracking instincts, the ...

s, followed by the human hunters on foot. In Britain, the 2004 Hunting Act

The Hunting Act 2004 (c 37) is an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which bans the hunting of most wild mammals (notably Red fox, foxes, deer, European hare, hares and American mink, mink) with dogs in England and W ...

banned hunting of hares with dogs, so the 60 beagle packs now use artificial "trails", or may legally continue to hunt rabbit

Rabbits, also known as bunnies or bunny rabbits, are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also contains the hares) of the order Lagomorpha (which also contains the pikas). ''Oryctolagus cuniculus'' includes the European rabbit speci ...

s. Hare coursing with greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurge ...

s was once an aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

pursuit, forbidden to lower social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

es. More recently, informal hare coursing became a lower class activity and was conducted without the landowner's permission; it is also now illegal. In Scotland concerns have been raised over the increasing numbers of hares shot under license.

Hare is traditionally cooked by jugging

Jugging is the process of stewing whole animals, mainly game or fish, for an extended period in a tightly covered container such as a casserole or an earthenware jug.

In France a similar stew of a game animal (historically thickened with the anima ...

: a whole hare is cut into pieces, marinated and cooked slowly with red wine and juniper berries

A juniper berry is the female seed cone produced by the various species of junipers. It is not a true berry, but a cone with unusually fleshy and merged scales, which gives it a berry-like appearance. The cones from a handful of species, especial ...

in a tall jug that stands in a pan of water. It is traditionally served with (or briefly cooked with) the hare's blood and port wine

Port wine (also known as vinho do Porto, , or simply port) is a Portuguese fortified wine produced in the Douro Valley of northern Portugal. It is typically a sweet red wine, often served with dessert, although it also comes in dry, semi- ...

. Hare can also be cooked in a casserole. The meat is darker and more strongly flavoured than that of rabbits. Young hares can be roasted; the meat of older hares becomes too tough for roasting, and may be slow-cooked

Low-temperature cooking is a cooking technique using temperatures in the range of about for a prolonged time to cook food. Low-temperature cooking methods include sous vide cooking, slow cooking using a slow cooker, cooking in a normal oven which ...

.

Status

The European hare has a wide range across Europe and western Asia and has been introduced to a number of other countries around the globe, often as a game species. In general it is considered moderately abundant in its native range, but declines in populations have been noted in many areas since the 1960s. These have been associated with the intensification of agricultural practices. The hare is an adaptable species and can move into new habitats, but it thrives best when there is an availability of a wide variety of weeds and other herbs to supplement its main diet of grasses. The hare is considered a pest in some areas; it is more likely to damage crops and young trees in winter when there are not enough alternative foodstuffs available.

The

The European hare has a wide range across Europe and western Asia and has been introduced to a number of other countries around the globe, often as a game species. In general it is considered moderately abundant in its native range, but declines in populations have been noted in many areas since the 1960s. These have been associated with the intensification of agricultural practices. The hare is an adaptable species and can move into new habitats, but it thrives best when there is an availability of a wide variety of weeds and other herbs to supplement its main diet of grasses. The hare is considered a pest in some areas; it is more likely to damage crops and young trees in winter when there are not enough alternative foodstuffs available.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

has evaluated the European hare's conservation status as being of least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

. However, at low population densities, hares are vulnerable to local extinction

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

s as the available gene pool

The gene pool is the set of all genes, or genetic information, in any population, usually of a particular species.

Description

A large gene pool indicates extensive genetic diversity, which is associated with robust populations that can surv ...

declines, making inbreeding more likely. This is the case in northern Spain and in Greece, where the restocking by hares brought from outside the region has been identified as a threat to regional gene pools. To counteract this, a captive breeding

Captive breeding, also known as captive propagation, is the process of plants or animals in controlled environments, such as wildlife reserves, zoos, botanic gardens, and other conservation facilities. It is sometimes employed to help species that ...

program has been implemented in Spain, and the relocation of some individuals from one location to another has increased genetic variety. The Bern Convention lists the hare under Appendix III as a protected species. Several countries, including Norway, Germany, Austria and Switzerland, have placed the species on their Red Lists as "near threatened" or "threatened".

References

External links

ARKive

Photographs Videos

BBC Wales Nature: Brown hare article

BBC Wales Nature: Brown hare

Brown hare and new vegetation

{{Authority control Lepus Hare, European Hare, European Introduced mammals of Australia Mammals of New Zealand Mammals of Grenada Mammals of Barbados Mammals of Guadeloupe Mammals of the Caribbean Fauna of the Falkland Islands Least concern biota of Asia Least concern biota of Europe Mammals described in 1778 Taxa named by Peter Simon Pallas