Leopold Auer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

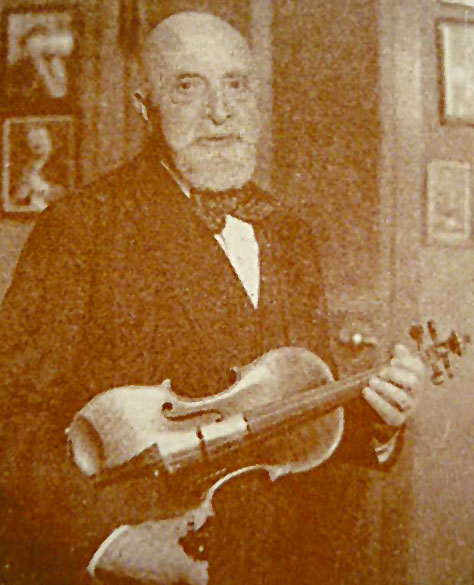

Leopold von Auer ( hu, Auer Lipót; June 7, 1845July 15, 1930) was a Hungarian

Up through 1917, Auer did not perform in the United States. He says there was "one serious deterrent — the great number of concerts exacted of the artist in a brief period of three or four months. My friends,

Up through 1917, Auer did not perform in the United States. He says there was "one serious deterrent — the great number of concerts exacted of the artist in a brief period of three or four months. My friends,

violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

ist, academic, conductor, composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

, and instructor. Many of his students went on to become prominent concert performers and teachers.

Early life and career

Auer was born inVeszprém

Veszprém (; german: Weißbrunn, sl, Belomost) is one of the oldest urban areas in Hungary, and a city with county rights. It lies approximately north of the Lake Balaton. It is the administrative center of the county (comitatus or 'megye') of ...

, Hungary, 7 June 1845,Fifield, Christopher, in Oxford Companion to Music, Alison Latham, ed., Oxford University Press, 2003 p. 70 to a poor Jewish household of painters. He first studied violin with a local concertmaster

The concertmaster (from the German ''Konzertmeister''), first chair (U.S.) or leader (U.K.) is the principal first violin player in an orchestra (or clarinet in a concert band). After the conductor, the concertmaster is the second-most signifi ...

. He later wrote that the violin was a "logical instrument" for any (musically inclined) Hungarian boy to take up because it "didn't cost much." At the age of 8 Auer continued his violin studies with Dávid Ridley Kohne, who also came from Veszprém, at the Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

Conservatory.Schwarz, p. 414 Kohne was concertmaster of the orchestra of the National Opera. A performance by Auer as soloist in the

Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

violin concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

attracted the interest of some wealthy music lovers, who gave him a scholarship to go to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

for further study. He lived at the home of his teacher, Jakob Dont

Jakob Dont (March 2, 1815 – November 17, 1888) was an Austrian violinist, composer, and teacher.

He was born and died in Vienna.

His father Valentin Dont was a noted cellist. Jakob was a student of Josef Böhm (1795–1876) and of Georg Hellm ...

.Auer, 1980, p. 3 Auer wrote that it was Dont who taught him the foundation for his violin technique. In Vienna he also attended quartet

In music, a quartet or quartette (, , , , ) is an ensemble of four singers or instrumental performers; or a musical composition for four voices and instruments.

Classical String quartet

In classical music, one of the most common combinations o ...

classes with Joseph Hellmesberger, Sr.

By the time Auer was 13, the scholarship money had run out. His father decided to launch his career. The income from provincial concerts was barely enough to keep father and son, and a pianist who formed a duo with Leopold, out of poverty. An audition with Henri Vieuxtemps

Henri François Joseph Vieuxtemps ( 17 February 18206 June 1881) was a Belgian composer and violinist. He occupies an important place in the history of the violin as a prominent exponent of the Franco-Belgian violin school during the mid-19th ce ...

in Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popul ...

was a failure, partly because Vieuxtemps' wife thought so. A visit to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

proved equally unsuccessful. Auer decided to seek the advice of Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907) was a Hungarian violinist, conductor, composer and teacher who made an international career, based in Hanover and Berlin. A close collaborator of Johannes Brahms, he is widely regarded as one of ...

, then royal concertmaster at Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

. The then king of Hanover was blind and very fond of music. He paid Joachim very well, and on those occasions when Auer also performed for the king, he was also paid enough to support him for a few weeks. The two years Auer spent with Joachim (1861–63, or 1863-1865 according to Auer, 1980, p. 9) proved a turning point in his career. He was already well prepared as a violinist. What proved revelatory was exposure to the world of German music making—a world that stresses musical values over virtuoso glitter. Auer later wrote,

Joachim was an inspiration to me, and opened before my eyes horizons of that greater art of which until then I had lived in ignorance. With him I worked not only with my hands, but with my head as well, studying the scores of the masters, and endeavoring to penetrate the very heart of their works.... I lsoplayed a great deal of chamber music with my fellow students.Auer spent the summer of 1864 at the spa village of

Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, where he had been hired to perform. There he met violinist Henryk Wieniawski

Henryk Wieniawski (; 10 July 183531 March 1880) was a Polish virtuoso violinist, composer and pedagogue who is regarded amongst the greatest violinists in history. His younger brother Józef Wieniawski and nephew Adam Tadeusz Wieniawski were al ...

and pianist brothers Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sai ...

and Nicholas Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich T ...

, later founder and director of the Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory (russian: Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, link=no) is a musical educational inst ...

and conductor of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra

The Moscow Symphony Orchestra is a non-state-supported Russian symphony orchestra, founded in 1989 by the sisters Ellen and Marina Levine. The musicians include graduates from such institutions as Moscow, Kiev, and Saint Petersburg Conservatory. T ...

. Auer received some informal instruction from Wieniawski. In the summer of 1865 Auer was in another spa village, Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden () is a spa town in the states of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg, south-western Germany, at the north-western border of the Black Forest mountain range on the small river Oos (river), Oos, ten kilometres (six miles) east of the ...

, where he met Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

, Brahms, and Johann Strauss Jr.

Johann Baptist Strauss II (25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (german: links=no, Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas. He composed ov ...

There were not so many touring violinists then as there were later, but in Vienna Auer was able to hear Henri Vieuxtemps

Henri François Joseph Vieuxtemps ( 17 February 18206 June 1881) was a Belgian composer and violinist. He occupies an important place in the history of the violin as a prominent exponent of the Franco-Belgian violin school during the mid-19th ce ...

from Belgium, Antonio Bazzini from Italy, and the Czech Ferdinand Laub

Ferdinand Laub (January 19, 1832March 17, 1875) was a Czech violinist and composer.

Life and career

Laub was born in Prague from a German Bohemian family which had assimilated into the ethnic Czech community. His father Erasmus (1794–1865) arr ...

; he was especially impressed by Vieuxtemps. Auer gave concerts in 1864 as soloist with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (Gewandhausorchester; also previously known in German as the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) is a German symphony orchestra based in Leipzig, Germany. The orchestra is named after the concert hall in which it is bas ...

, invited by concertmaster Ferdinand David

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, conductor Felix "Mendelssohn's friend." At that time, Auer says, Leipzig was "more important, from a musical point of view, than Berlin and even Vienna." Success led to his becoming, at the age of 19, concertmaster

The concertmaster (from the German ''Konzertmeister''), first chair (U.S.) or leader (U.K.) is the principal first violin player in an orchestra (or clarinet in a concert band). After the conductor, the concertmaster is the second-most signifi ...

in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

. In 1866 he got the same position in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

; he also led a string quartet there.

During May and June 1868, Auer was engaged to play a series of concerts in London.Auer 1923, p. 114 In one concert, he played Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's Archduke Trio

Archduke (feminine: Archduchess; German: ''Erzherzog'', feminine form: ''Erzherzogin'') was the title borne from 1358 by the Habsburg rulers of the Archduchy of Austria, and later by all senior members of that dynasty. It denotes a rank withi ...

with pianist Anton Rubinstein and cellist Alfredo Piatti.

Russia

Rubinstein was in search for a violin professor for theSaint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

, which he had founded in 1862, and he proposed Auer. Auer agreed to a three-year contract, also as soloist at the court of Grand Duchess Helena. At first, music critics in St. Petersburg harshly criticized Auer's playing and compared it unfavorably with that of his predecessor, Wieniawski. But Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

's admiration for Auer's playing led to its acceptance. Auer would stay for 49 years (1868-1917). During that time he held the position of first violinist to the orchestra of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres. This included the principal venue of the Imperial Ballet

The Mariinsky Ballet (russian: Балет Мариинского театра) is the resident classical ballet company of the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Founded in the 18th century and originally known as the Imperial Russ ...

and Opera, the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

The Saint Petersburg Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre (The Big Stone Theatre of Saint Petersburg, russian: Большой Каменный Театр) was a theatre in Saint Petersburg.

It was built in 1783 to Antonio Rinaldi's Neoclassical ...

(until 1886), and later the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

The Mariinsky Theatre ( rus, Мариинский театр, Mariinskiy teatr, also transcribed as Maryinsky or Mariyinsky) is a historic theatre of opera and ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Opened in 1860, it became the preeminent music th ...

, as well as the Imperial Theatres of Peterhof and the Hermitage. Until 1906, Auer played almost all of the violin solos in the ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

s performed by the Imperial Ballet

The Mariinsky Ballet (russian: Балет Мариинского театра) is the resident classical ballet company of the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Founded in the 18th century and originally known as the Imperial Russ ...

, the majority of which were choreographed by Marius Petipa

Marius Ivanovich Petipa (russian: Мариус Иванович Петипа), born Victor Marius Alphonse Petipa (11 March 1818), was a French ballet dancer, pedagogue and choreographer. Petipa is one of the most influential ballet masters an ...

. Before Auer, Vieuxtemps and Wieniawski had played the ballet solos.

Until 1906, Auer was also leader of the string quartet for the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

(RMS). This quartet's concerts were as integral a part of the Saint Petersburg musical scene as their counterparts led by Joachim in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. Criticism arose in later years of less-than-perfect ensemble playing and insufficient attention to contemporary Russian music. Nevertheless, Auer's group performed quartets by Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, Alexander Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

, Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

. The group also played music by Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

and Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

, along with Louis Spohr

Louis Spohr (, 5 April 178422 October 1859), baptized Ludewig Spohr, later often in the modern German form of the name Ludwig, was a German composer, violinist and conductor. Highly regarded during his lifetime, Spohr composed ten symphonies, t ...

, Joachim Raff and other lesser known German composers.

Sometime around 1870, Auer decided to convert to Russian Orthodoxy.

At the Conservatory, the leading piano teacher Theodor Leschetizky

Theodor Leschetizky (sometimes spelled Leschetitzky, pl, Teodor Leszetycki; 22 June 1830 – 14 November 1915 was an Austrian- Polish pianist, professor, and composer born in Landshut in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, then a crown land of ...

introduced Auer to Anna Yesipova

Anna Yesipova (born ''Anna Nikolayevna Yesipova'' '' russian:_Анна_Николаевна_Есипова.html" ;"title="/nowiki>russian: Анна Николаевна Есипова">/nowiki>russian: Анна Николаевна Есипов� ...

, who Leschetizky said was his best student. Auer performed sonatas with many great pianists, but his favorite recital partner was Yesipova, with whom he appeared until her death in 1914. Other partners included Anton Rubinstein, Leschetizky, Raoul Pugno

Stéphane Raoul Pugno (23 June 1852) was a French composer, teacher, organist, and pianist known for his playing of Mozart's works.

Biography

Raoul Pugno was born in Paris and was of Italian origin. He made his debut at the age of six, and with t ...

, Sergei Taneyev

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Тане́ев, ; – ) was a Russian composer, pianist, teacher of composition, music theorist and author.

Life

Taneyev was born in Vladimir, Vladimir Governorate, Russia ...

and Eugen d'Albert

Eugen (originally Eugène) Francis Charles d'Albert (10 April 1864 – 3 March 1932) was a Scottish-born pianist and composer.

Educated in Britain, d'Albert showed early musical talent and, at the age of seventeen, he won a scholarship to stud ...

. One sonata Auer liked to perform was Tartini's "Devil's Trill" Sonata, written about 1713. In the 1890s, Auer performed cycles of all 10 Beethoven violin sonatas. A particular favorite of Auer's was the 'Kreutzer' sonata, which Auer had first heard performed in Hanover by Joachim and Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

.

From 1914 to 1917, on concert tours of Russia, Auer was accompanied by the pianist Wanda Bogutska Stein.

America

Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sai ...

, Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, virtuoso pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for es ...

. and Henri Wieniawski told ethat, although their American tours had been most interesting, they were reluctant to accept new engagements because of the severe strain" their tours had been for them. "But in 1918...work in Russia became impossible because of the" Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

. He then moved to the United States, although because of his age, he did not undertake a wide concert tour. He played at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

on March 23, 1918 and also performed in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. He taught some private students at his home on Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

's Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper West ...

. In 1926 he joined the Institute of Musical Art (later to become the Juilliard School

The Juilliard School ( ) is a private performing arts conservatory in New York City. Established in 1905, the school trains about 850 undergraduate and graduate students in dance, drama, and music. It is widely regarded as one of the most el ...

). In 1928 he joined the faculty of the Curtis Institute of Music

The Curtis Institute of Music is a private conservatory in Philadelphia. It offers a performance diploma, Bachelor of Music, Master of Music in opera, and a Professional Studies Certificate in opera. All students attend on full scholarship.

Hi ...

in Philadelphia. He died in 1930 in Loschwitz

Loschwitz is a borough ('' Stadtbezirk'') of Dresden, Germany, incorporated in 1921. It consists of ten quarters (''Stadtteile''):

Loschwitz is a villa quarter located at the slopes north of the Elbe river. At the top of the hillside is the quar ...

, a suburb of Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and was interred in the Ferncliff Cemetery

Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum is located at 280 Secor Road in the hamlet of Hartsdale, town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York, United States, about north of Midtown Manhattan. It was founded in 1902, and is non-sectarian. Fernc ...

in Hartsdale

Hartsdale is a hamlet located in the town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 5,293 at the 2010 census. It is a suburb of New York City.

History

Hartsdale, a CDP/hamlet/post-office in the town of Green ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

Playing

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

was especially taken with Auer's playing. Reviewing an 1874 appearance in Moscow, Tchaikovsky praised Auer's "great expressivity, the thoughtful finesse and poetry of the interpretation." This finesse and poetry came at a tremendous price. Auer suffered as a performer from poorly formed hands. He had to work incessantly, with an iron determination, just to keep his technique in shape. He wrote, "My hands are so weak and their conformation is so poor that when I have not played the violin for several successive days, and then take up the instrument, I feel as if I had altogether lost the facility of playing."

Despite this handicap, Auer achieved much through constant work. His tone was small but ingratiating, his technique polished and elegant. His playing lacked fire, but he made up for it with a classic nobility. After he arrived in the United States, he made some recordings which bear this out. They show the violinist in excellent shape technically, with impeccable intonation, incisive rhythm and tasteful playing.

His musical tastes were conservative and refined. He liked virtuoso works by Henri Vieuxtemps

Henri François Joseph Vieuxtemps ( 17 February 18206 June 1881) was a Belgian composer and violinist. He occupies an important place in the history of the violin as a prominent exponent of the Franco-Belgian violin school during the mid-19th ce ...

, such as his three violin concertos, and Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst

Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (8 June 18128 October 1865) was a Moravian-Jewish violinist, violist and composer. He was seen as the outstanding violinist of his time and one of Niccolò Paganini's greatest successors. He contributed to polyphonic playin ...

, and used those works in his teaching. Once a student objected to playing Ernst's ''Othello Fantasy'', saying it was bad music. Auer did not back down. "You'll play it until it sounds like good music," he thundered at the student, "and you'll play nothing else."

Bach's works

Concertos

Auer never assigned either of Bach's solo violin concertos to a student. TheDouble Concerto

A double concerto (Italian: ''Doppio concerto''; German: ''Doppelkonzert'') is a concerto featuring two performers—as opposed to the usual single performer, in the solo role. The two performers' instruments may be of the same type, as in Bach's ...

, however, was one of his favorites. Auer calls the Double Concerto "the most important" of the three concertos.

Unaccompanied violin or violin and piano sonatas

Auer wrote thatFerdinand David

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

"earned the undying gratitude of the violinistic world by eiscovering the 'solo sonatas for violin', BWV 1001-1006, and the "Six sonatas for violin and piano".Auer 2012, p. 20

"David edited and published these works, and Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907) was a Hungarian violinist, conductor, composer and teacher who made an international career, based in Hanover and Berlin. A close collaborator of Johannes Brahms, he is widely regarded as one of ...

was the first to introduce them to the musical world at large", making "these compositions ... a fundamental pillar of violin literature."

Auer puts special emphasis on the Chaconne from Bach's fourth sonata for unaccompanied violin (depending on editions, later known as Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004) together with 33 variations.

Mozart's concertos

Mozart wrote 5 concertos for violin and orchestra, all in 1775, and a well-appreciated double concerto, the Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364. Auer (2012) does not mention it, but mentions two of the single-violin concertos, one in D major, No. 4, and one in A major, No. 5. For another, in E-flat major, it turned out that Mozart did not actually write it.Conducting

Auer was also active as a conductor. He was in charge of theRussian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

orchestral concerts intermittently in the 1880s and 90s. He was always willing to mount the podium to accompany a famous foreign soloist—as he did when Joachim visited Russia—and did the same for his students concertizing abroad.

Teaching

Auer is remembered as one of the most important pedagogues of the violin, and was one of the most sought-after teachers for gifted students. "Auer's position in the history of violin playing is based on his teaching." Many notable virtuoso violinists were among his students, includingMischa Elman

Mischa (Mikhail Saulovich) Elman (russian: Михаил Саулович Эльман; January 20, 1891April 5, 1967) was a Russian-born American violinist famed for his passionate style, beautiful tone, and impeccable artistry and musicality.

E ...

, Konstanty Gorski, Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz (; December 10, 1987) was a Russian-born American violinist. Born in Vilnius, he moved while still a teenager to the United States, where his Carnegie Hall debut was rapturously received. He was a virtuoso since childhood. Fritz ...

, Nathan Milstein

Nathan Mironovich Milstein ( – December 21, 1992) was a Russian-born American virtuoso violinist.

Widely considered one of the finest violinists of the 20th century, Milstein was known for his interpretations of Bach's solo violin works and ...

, Toscha Seidel

Toscha Seidel (November 17, 1899 – November 15, 1962) was a Russian violin virtuoso.

Biography

Seidel was born in Odessa on November 17, 1899, to a Jewish family. A student of Leopold Auer in St. Petersburg, Seidel became known for a lush, rom ...

, Efrem Zimbalist

Efrem Zimbalist Sr. ( – February 22, 1985) was a concert violinist, composer, conductor and director of the Curtis Institute of Music.

Early life

Efrem Zimbalist Sr. was born on April 9, 1888, O. S., equivalent to April 21, 1889, in the Greg ...

, Georges Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

, Lyubov Streicher

Lyubov Lvovna Streicher (3 March 1888 - 31 March 1958) was a Russian composer, teacher, and violinist, as well as a founding member of the Society for Jewish Folk Music.

Streicher was born in Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавк ...

, Benno Rabinof Benno and Sylvia Rabinof were a violin and piano duo. They extensively toured the U.S., Europe, Asia and Africa throughout their career together performing a mix of classical and contemporary pieces.

Benno Rabinof

Benno Rabinof (1902-1975), a violi ...

, Kathleen Parlow

Kathleen Parlow (September 20, 1890 – August 19, 1963) was a violinist known for her outstanding technique, which earned her the nickname "The lady of the golden bow". Although she left Canada at the age of four and did not permanently return ...

, Julia Klumpke

Julia Klumpke, often spelled Julia Klumpkey (August 13, 1870 — August 23, 1961), was an American concert violinist and composer.

Family and education

Julia Klumpke, known as Lulu, was born in San Francisco, California, the daughter of wealthy r ...

, Thelma Given

Thelma is a female given name. It was popularized by Victorian writer Marie Corelli who gave the name to the title character of her 1887 novel ''Thelma''. It may be related to a Greek word meaning "will, volition" see ''thelema''). Note that altho ...

, Sylvia Lent

Sylvia Lent (June 11, 1903 – March 25, 1972) was an American violinist.

Early life

Sylvia Lent was born in Washington, D. C., the daughter of composer and cellist Ernest Lent and pianist Mary (Mamie) Simons Lent. Ernest Lent was born and educat ...

, Kemp Stillings, Oscar Shumsky, and Margarita Mandelstamm. Among these were "some of the greatest violinists" of the twentieth century.Schwarz, p. 408

Babel (1931) describes how in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

(now in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

) very promising young violin students such as Elman, Milstein, and Zimbalist were enrolled in the violin class of Pyotr Stolyarsky

Pyotr Solomonovich Stolyarsky (russian: Пётр Соломонович Столярский, uk, Петро Соломонович Столярський), (29 April 1944) was a Soviet violinist and eminent pedagogue, honored as People's A ...

, and if successful, sent on to Auer in St. Petersburg.

Auer also taught the young Clara Rockmore

Clara Reisenberg Rockmore (9 March 1911 – 10 May 1998) was a Lithuanian classical violin prodigy and a virtuoso performer of the theremin, an electronic musical instrument. She was the sister of pianist Nadia Reisenberg.

Life and career Ea ...

, who later became one of the world's foremost exponents of the theremin

The theremin (; originally known as the ætherphone/etherphone, thereminophone or termenvox/thereminvox) is an electronic musical instrument controlled without physical contact by the performer (who is known as a thereminist). It is named afte ...

. Most of Auer's students studied with him at the St. Petersburg Conservatory (even Kathleen Parlow, coming all the way from western Canada), but Georges Boulanger, from Romania, studied with him in Dresden, Germany. Benno Rabinof and Oscar Shumsky, born in the United States, studied with Auer there.

Like pianist Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

, in his teaching, Auer did not focus on technical matters with his students. Instead, he guided their interpretations and concepts of music. If a student ran into a technical problem, Auer did not offer any suggestions. Neither was he inclined to pick up a bow to demonstrate a passage. Nevertheless, he was a stickler for technical accuracy. Fearing to ask Auer themselves, many students turned to each other for help. (Paradoxically, in the years before 1900 when Auer focused more closely on technical details, he did not turn out any significant students.)

While Auer valued talent, he considered it no excuse for lack of discipline, sloppiness or absenteeism. He demanded punctual attendance. He expected intelligent work habits and attention to detail. Lessons were as grueling, and required as much preparation, as recital performances.

In lieu of weekly lessons, students were required to bring a complete movement of a major work. This usually demanded more than a week to prepare. Once a student felt ready to play this work, he or she had to sign up 10 days prior to the class meeting. The student was expected to have the concert ready and to be dressed accordingly. An accompanist was provided. An audience watched—comprised not only of students and parents, but also often of distinguished guests and prominent musicians. Auer arrived for the lesson punctually; everything was supposed to be in place by the time he arrived. During the lesson, Auer would walk around the room, observing, correcting, exhorting, scolding, shaping the interpretation. "We did not dare cross the threshold of the classroom with a half-ready performance," one student remembered.

Admission to Auer's class was a privilege won by talent. Remaining there was a test of endurance and hard work. Auer could be stern, severe, harsh. One unfortunate student was ejected regularly, with the music thrown after him. Auer valued musical vitality and enthusiasm. He hated lifeless, anemic playing and was not above poking a bow into a student's ribs, demanding more ''"krov."'' (The word literally means "blood" but can also be used to mean fire or vivacity.)

While Auer pushed his students to their limits, he also remained devoted to them. He remained solicitous of their material needs. He helped them obtain scholarships, patrons and better instruments. He used his influence in high government offices to obtain residence permits for his Jewish students.

Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz (; December 10, 1987) was a Russian-born American violinist. Born in Vilnius, he moved while still a teenager to the United States, where his Carnegie Hall debut was rapturously received. He was a virtuoso since childhood. Fritz ...

and his father in the Conservatory

There was a somewhat limited area of Russia called the Jewish Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

in which Jews were allowed to live. The area consisted approximately of Ukraine, Poland, and Belarus. Around 1900, St. Petersburg had a substantial Jewish community, the largest in Russia outside the Pale. Auer (1923, pp. 156–157) wrote that Jascha, as a boy ten or eleven years old,

was admitted to the Conservatoire without question in view of his talent; but what was to be done with his family? Someone hit upon the happy idea of suggesting that I admit Jascha's father, a violinist of forty, into my own class ... This I did, and as a result the law was obeyed while at the same time the Heifetz family was not separated, for it was not legally permissible for the wife and children of a Conservatoire pupil to be separated from their husband and father. However, since the students were without exception expected to attend the obligatory classes in solfeggio, piano, and harmony, and since Papa Heifetz most certainly did not attend any of them ... I had to do battle continually with the management on his account. It was not until the advent ofAuer shaped his students' personalities. He gave them style, taste, musical breeding. He also broadened their horizons. He made them read books, guided their behavior and career choices and polished their social graces. He also insisted that his students learn a foreign language if an international career was expected. Even after a student started a career, Auer would watch with a paternal eye. He wrote countless letters of recommendation to conductors and concert agents. When Mischa Elman was preparing for his London debut, Auer traveled there to coach him. He also continued work with Efrem Zimbalist and Kathleen Parlow after their debuts.Glazunov Glazunov (; feminine: Glazunova) is a Russian surname that may refer to: *Alexander Glazunov (1865–1936), Russian composer ** Glazunov Glacier in Antarctica named after Alexander * Andrei Glazunov, 19th-century Russian trade expedition leader * An ..., my last director, that I had no further trouble in seeing that the boy remained in his parents' care until the summer of 1917, when the family was able to go to America."

Dedications

A number of composers dedicated pieces to Auer. One such case wasTchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

's ''Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

'', which, however, he initially chose not to play. This was not because he regarded the work as "unplayable", as some sources say, but because he felt that "some of the passages were not suited to the character of the instrument, and that, however perfectly rendered, they would not sound as well as the composer had imagined". He did play the work later in his career, with alterations in certain passages that he felt were necessary. Performances of the Tchaikovsky concerto by Auer's students (with the exception of Nathan Milstein

Nathan Mironovich Milstein ( – December 21, 1992) was a Russian-born American virtuoso violinist.

Widely considered one of the finest violinists of the 20th century, Milstein was known for his interpretations of Bach's solo violin works and ...

's) were also based on Auer's edition. Another work Tchaikovsky had dedicated to Auer was the ''Sérénade mélancolique

The ''Sérénade mélancolique'' in B-flat minor for violin and orchestra, Op. 26 (Russian: ''Меланхолическая серенада''), was written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in February 1875. It was his first work for violin and orc ...

'' of 1875. After their conflict over the Violin Concerto, Tchaikovsky also withdrew the ''Sérénades dedication to Auer. British composer Eva Ruth Spalding

Eva Ruth Spalding (December 19, 1883 - March 1969) was a British composer who wrote string quartets and piano music, and set texts by many poets to music.

Spalding was born in Blackheath, Kent, to Henry Spalding and his second wife Ellen. She was ...

dedicated one of her string quartets to Auer, who had been her teacher at the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Compositions and writings

Auer wrote a small number of works for his instrument, including the ''Rhapsodie hongroise'' for violin and piano. He also wrote a number ofcadenza

In music, a cadenza (from it, cadenza, link=no , meaning cadence; plural, ''cadenze'' ) is, generically, an improvisation, improvised or written-out ornament (music), ornamental passage (music), passage played or sung by a solo (music), sol ...

s for other composers' violin concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

s including those by Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

, and Mozart's third. He wrote three books: ''Violin Playing as I Teach It'' (1920), ''My Long Life in Music'' (1923) and ''Violin Master Works and Their Interpretation'' (1925). He also wrote an arrangement for Paganini's 24th Caprice (with Schumann's piano accompaniment) later performed by Jascha Heifetz, Henryk Szeryng and Ivry Gitlis, in which the final variation is removed and his own composed. There are also alterations to various passages throughout the piece. Auer edited much of the standard repertoire, concertos, short pieces and all of Bach's solo works. His editions are published mostly by Carl Fischer. He also transcribed a great many works for the violin including some of Chopin's piano preludes.

Evaluation and selection of concertos and (Beethoven) romances

In ''Violin Master Works....'', Auer 2012, Auer gives some rankings. Chapter X is on "Three Master Concertos," namely Beethoven's, Brahms', and Mendelssohn's. To these three,Joachim

Joachim (; ''Yəhōyāqīm'', "he whom Yahweh has set up"; ; ) was, according to Christian tradition, the husband of Saint Anne and the father of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The story of Joachim and Anne first appears in the Biblical apocryphal ...

adds a fourth, by Max Bruch

Max Bruch (6 January 1838 – 2 October 1920) was a German Romantic composer, violinist, teacher, and conductor who wrote more than 200 works, including three violin concertos, the first of which has become a prominent staple of the standard v ...

.Steinberg, 1998, p. 265 Auer's Chapter XI on "The Bruch Concertos" mentions two. Bruch's First, in G minor, Op. 26, Auer says is probably the next-most played after the three "master" concertos. Steinberg (1998) does not mention Bruch concertos after the first, although both he and Auer mention the ''Scottish Fantasy'' for violin and orchestra. See above about Bach's and Mozart's violin concertos.

Beethoven wrote two Romances for violin and orchestra, Romance No. 1 in G, Op. 40, and Romance No. 2 in F, Op. 50. Auer (pp. 52–54) mentions the two Romances as scored for violin and piano in versions he had edited, but the text is about the orchestral version.

Relations

Auer's first wife, Nadine Pelikan, was Russian. Thejazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

vibraphonist

The vibraphone is a percussion instrument in the metallophone family. It consists of tuned metal bars and is typically played by using mallets to strike the bars. A person who plays the vibraphone is called a ''vibraphonist,'' ''vibraharpist,' ...

Vera Auer

Vera Auer (later Vera Auer-Boucher) (April 20, 1919, Vienna – August 2, 1996, New York City) was an Austrian jazz accordionist and vibraphone, vibraphonist. She was the niece of Leopold Auer.

Auer learned classical piano but turned to jazz after ...

is a niece of Leopold Auer. The actor Mischa Auer

Mischa Auer (born Mikhail Semyonovich Unkovsky (Михаил Семёнович Унковский; 17 November 1905 – 5 March 1967) was a Russians, Russian-born American actor who moved to Hollywood in the late 1920s. He first appeared in fi ...

(born Mischa Ounskowsky) was his grandson. The composer György Ligeti

György Sándor Ligeti (; ; 28 May 1923 – 12 June 2006) was a Hungarian-Austrian composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important avant-garde composers in the latter half of the twentieth century" ...

(the name Ligeti is a Hungarian equivalent of the German name Auer) was his great-grandnephew. Prominent Hungarian philosopher and lecturer Ágnes Heller

Ágnes Heller (12 May 1929 – 19 July 2019) was a Hungarian philosopher and lecturer. She was a core member of the Budapest School philosophical forum in the 1960s and later taught political theory for 25 years at the New School for Social Res ...

mentions that prominent Hungarian violinist Leopold Auer was related to her family on her mother's side.

Auer's second wife, Wanda Bogutska Stein (Auer), was his piano accompanist on some concert tours (in Russia up to 1917) and later on some recordings.

Discography

* Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor, byBrahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

, 1920

* ''Mélodie'' in E-flat major, Op. 42, No. 3 (from '' Souvenir d'un lieu cher''), by Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, 1920

These were both taken from a live recording in Carnegie Hall where Auer gave a sold out performance toward the end of his life.

Notes

Sources

* Auer, Leopold, ''Violin Playing As I Teach It'', Dover, New York, 1980, ; earlier edition, Stokes, New York, 1921 * Auer, Leopold (1923), ''My Long Life in Music'', F. A. Stokes, New York * Auer, Leopold (1925), ''Violin Master Works and their Interpretation'', Carl Fischer, New York, repr. Dover, 2012, * Babel, Isaac (1931), "Awakening," in Maxim D. Shrayer, ed., ''An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature: Two Centuries of Dual Identity, 1801-1953'', pub. M. E. Sharpe, 2007, transl. from Russian by Larissa Szporluk, a Google book, pp. 313–315. * Klier, John D. (1995), ''Imperial Russia's Jewish Question'', 1855–1881, Cambridge University Press, a Google Book * Nathans, Benjamin, 2004, ''Beyond the Pale: The Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia'', University of California Press, a Google Book. * Potter, Tully, sleeve note to ''Great Violinists: Jascha Heifetz'', naxos recording 8.111288, of the three Bach violin concertos and Mozart's no. 5. * Roth, Henry (1997). ''Violin Virtuosos: From Paganini to the 21st Century''. Los Angeles, CA: California Classics Books. * Schwarz, Boris, ''Great Masters of the Violin'' (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983) * Steinberg, Michael (1998), ''The Concerto'', Oxford University Press * ''The Violinist, Vols. 22-23'', a Google Book, article "American Debut of Leopold Auer", p. 190.External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Auer, Leopold 1845 births 1930 deaths People from the Kingdom of Hungary People from Veszprém Hungarian Jews Austro-Hungarian Jews Austro-Hungarian emigrants to the Russian Empire Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent Converts to Eastern Orthodoxy from Judaism 19th-century classical composers 20th-century classical composers Saint Petersburg Conservatory academic personnel Hungarian classical violinists Hungarian Jewish violinists Male classical violinists Hungarian classical composers Hungarian male classical composers American male classical composers Hungarian conductors (music) Male conductors (music) Jewish American classical composers Jewish classical violinists Pupils of Joseph Joachim Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky American Romantic composers Violin pedagogues Burials at Ferncliff Cemetery 20th-century American composers 19th-century American composers 19th-century American male musicians 20th-century conductors (music) People from the Upper West Side