Leo Esaki on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

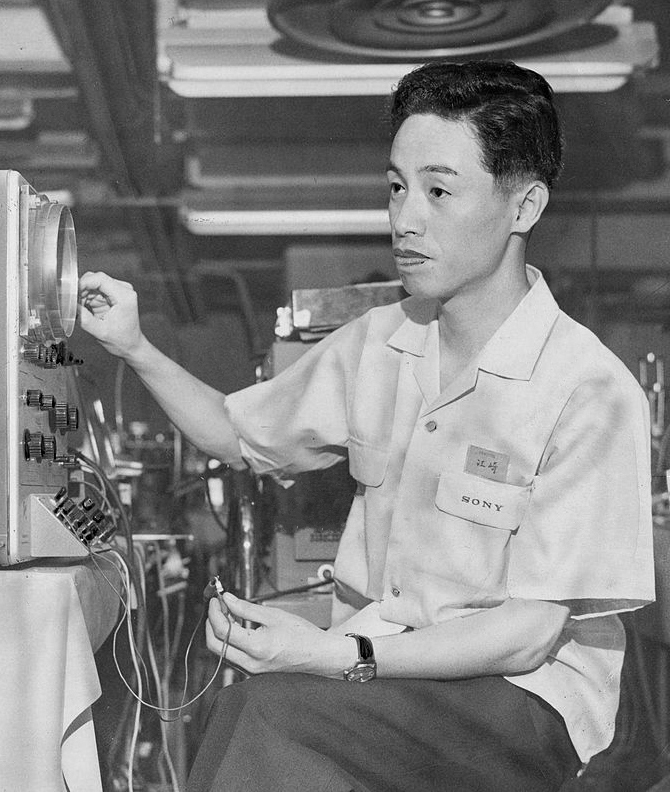

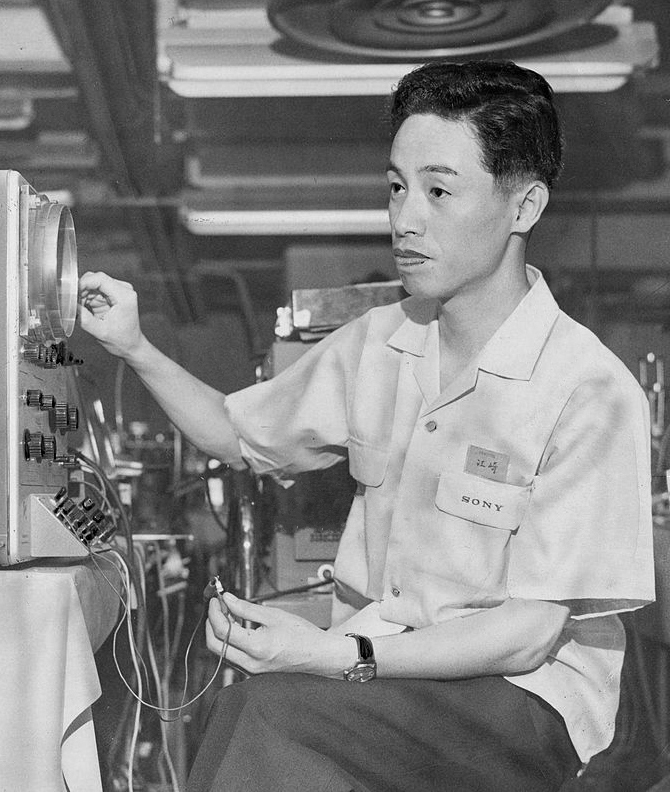

Reona Esaki (江崎 玲於奈 ''Esaki Reona'', born March 12, 1925), also known as Leo Esaki, is a Japanese physicist who shared the

From 1947 to 1960, Esaki joined Kawanishi Corporation (now Denso Ten) and Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now

From 1947 to 1960, Esaki joined Kawanishi Corporation (now Denso Ten) and Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now

IBM record

* IEEE History Center – Leo Esaki. Retrieved July 19, 2011 fro

Leo Esaki - Engineering and Technology History Wiki

* Sony History – The Esaki Diode. Retrieved August 5, 2003 fro

Freeview video 'An Interview with Leo Esaki' by the Vega Science Trust

{{DEFAULTSORT:Esaki, Leo 1925 births Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society IBM Fellows IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Japanese Nobel laureates 20th-century Japanese physicists Japanese nanotechnologists 20th-century Japanese inventors Kwansei Gakuin University faculty Kyoto University faculty Living people Nobel laureates in Physics People from Higashiōsaka Semiconductor physicists Recipients of the Order of Culture University of Tsukuba faculty Foreign associates of the National Academy of Engineering University of Tokyo alumni

Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1973 with Ivar Giaever

Ivar Giaever ( no, Giæver, ; born April 5, 1929) is a Norwegian-American engineer and physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 with Leo Esaki and Brian Josephson "for their discoveries regarding tunnelling phenomena in solids". G ...

and Brian David Josephson

Brian David Josephson (born 4 January 1940) is a Welsh theoretical physicist and professor emeritus of physics at the University of Cambridge. Best known for his pioneering work on superconductivity and quantum tunnelling, he was awarded the Nob ...

for his work in electron tunneling

Quantum tunnelling, also known as tunneling ( US) is a quantum mechanical phenomenon whereby a wavefunction can propagate through a potential barrier.

The transmission through the barrier can be finite and depends exponentially on the barrier ...

in semiconductor materials which finally led to his invention of the Esaki diode, which exploited that phenomenon. This research was done when he was with Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now known as Sony

, commonly stylized as SONY, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. As a major technology company, it operates as one of the world's largest manufacturers of consumer and professional ...

). He has also contributed in being a pioneer of the semiconductor superlattice

A superlattice is a periodic structure of layers of two (or more) materials. Typically, the thickness of one layer is several nanometers. It can also refer to a lower-dimensional structure such as an array of quantum dots or quantum wells.

Disc ...

s.

Early life and education

Esaki was born in Takaida-mura, Nakakawachi-gun,Osaka Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Osaka Prefecture has a population of 8,778,035 () and has a geographic area of . Osaka Prefecture borders Hyōgo Prefecture to the northwest, Kyoto Prefecture ...

(now part of Higashiōsaka City) and grew up in Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

, near by Kyoto Imperial University

, mottoeng = Freedom of academic culture

, established =

, type = Public (National)

, endowment = ¥ 316 billion (2.4 billion USD)

, faculty = 3,480 (Teaching Staff)

, administrative_staff = 3,978 (Total Staff)

, students = ...

and Doshisha University

, mottoeng = Truth shall make you free

, tagline =

, established = Founded 1875,Chartered 1920

, vision =

, type = Private

, affiliation =

, calendar =

, endowment = €1 ...

. He first had contact with American culture

The culture of the United States of America is primarily of Western, and European origin, yet its influences includes the cultures of Asian American, African American, Latin American, and Native American peoples and their cultures. The U ...

in . After graduating from the Third Higher School, he studied physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

at Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

, where he had attended Hideki Yukawa

was a Japanese theoretical physicist and the first Japanese Nobel laureate for his prediction of the pi meson, or pion.

Biography

He was born as Hideki Ogawa in Tokyo and grew up in Kyoto with two older brothers, two older sisters, and two yo ...

's course in nuclear theory in October 1944. Also, he lived through the Bombing of Tokyo

The was a series of firebombing air raids by the United States Army Air Force during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Operation Meetinghouse, which was conducted on the night of 9–10 March 1945, is the single most destructive bombing ...

while he was at college.江崎玲於奈『限界への挑戦―私の履歴書』(日本経済新聞出版社)2007年

Esaki received his B.Sc. and Ph.D. in 1947 and 1959, respectively, from the University of Tokyo

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

(UTokyo).

Career

Esaki diode

From 1947 to 1960, Esaki joined Kawanishi Corporation (now Denso Ten) and Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now

From 1947 to 1960, Esaki joined Kawanishi Corporation (now Denso Ten) and Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now Sony

, commonly stylized as SONY, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. As a major technology company, it operates as one of the world's largest manufacturers of consumer and professional ...

). Meanwhile, American physicists John Bardeen

John Bardeen (; May 23, 1908 – January 30, 1991) was an American physicist and engineer. He is the only person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics twice: first in 1956 with William Shockley and Walter Brattain for the invention of the tran ...

, Walter Brattain

Walter Houser Brattain (; February 10, 1902 – October 13, 1987) was an American physicist at Bell Labs who, along with fellow scientists John Bardeen and William Shockley, invented the point-contact transistor in December 1947. They shared the ...

, and William Shockley

William Bradford Shockley Jr. (February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American physicist and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Brattain. The three scientists were jointly ...

invented the transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch e ...

, which encouraged Esaki to change fields from vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

to heavily-doped germanium

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors s ...

and silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic tab ...

research in Sony. One year later, he recognized that when the PN junction width of germanium is thinned, the current-voltage characteristic is dominated by the influence of the tunnel effect and, as a result, he discovered that as the voltage is increased, the current decreases inversely, indicating negative resistance. This discovery was the first demonstration of solid tunneling effects in physics, and it was the birth of new electronic devices in electronics called Esaki diode (or tunnel diode). He received a doctorate degree from UTokyo due to this breakthrough invention in 1959.

In 1973, Esaki was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

for research conducted around 1958 regarding electron tunneling in solids. He became the first Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

to receive the prize from the hands of the King Carl XVI Gustaf

Carl XVI Gustaf (Carl Gustaf Folke Hubertus; born 30 April 1946) is King of Sweden. He ascended the throne on the death of his grandfather, Gustaf VI Adolf, on 15 September 1973.

He is the youngest child and only son of Prince Gustaf Adolf, Du ...

.

Semiconductor superlattice

Esaki moved to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in 1960 and joined the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, where he became an IBM Fellow

An IBM Fellow is an appointed position at IBM made by IBM's CEO. Typically only four to nine (eleven in 2014) IBM Fellows are appointed each year, in May or June. Fellow is the highest honor a scientist, engineer, or programmer at IBM can achie ...

in 1967. He predicted that semiconductor superlattices

A superlattice is a periodic structure of layers of two (or more) materials. Typically, the thickness of one layer is several nanometers. It can also refer to a lower-dimensional structure such as an array of quantum dots or quantum wells.

Di ...

will be formed to induce a differential negative-resistance effect via an artificially one-dimensional periodic structural changes in semiconductor crystals. His unique "molecular beam epitaxy" thin-film crystal growth method can be regulated quite precisely in ultrahigh vacuum. His first paper on the semiconductor superlattice was published in 1970. A 1987 comment by Esaki regarding the original paper notes:

"The original version of the paper was rejected for publication by ''In 1972, Esaki realized his concept of superlattices in III-V group semiconductors, later the concept influenced many fields like metals, and magnetic materials. He was awarded thePhysical Review ''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the American Physical S ...'' on the referee's unimaginative assertion that it was 'too speculative' and involved 'no new physics.' However, this proposal was quickly accepted by the Army Research Office..."

IEEE Medal of Honor

The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest recognition of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It has been awarded since 1917, when its first recipient was Major Edwin H. Armstrong. It is given for an exceptional contributio ...

"for contributions to and leadership in tunneling, semiconductor superlattices, and quantum wells" in 1991 and the Japan Prize "for the creation and realization of the concept of man-made superlattice crystals which lead to generation of new materials with useful applications" in 1998.

Esaki's “five don’ts” rules

In 1994Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings

The Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings are annual scientific conferences held in Lindau, Bavaria, Germany, since 1951. Their aim is to bring together Nobel laureates and young scientists to foster scientific exchange between different generations, ...

, Esaki suggests a list of “five don’ts” which anyone in realizing his creative potential should follow. Two months later, the chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics Carl Nordling

Carl Nordling (6 February 1931 – 1 April 2016) was a Swedish physicist who was a professor of physics at Uppsala University. He was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and served as the chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

...

incorporated the rules in his own speech.

#Don't allow yourself to be trapped by your past experiences.

#Don't allow yourself to become overly attached to any one authority in your field – the great professor, perhaps.

#Don't hold on to what you don't need.

#Don't avoid confrontation.

#Don't forget your spirit of childhood curiosity.

Later years

In 1977, Esaki was elected as a member into theNational Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Engineering is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy ...

for contributions to the engineering of semiconductor devices.

Esaki moved back to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

in 1992. Subsequently, he served as president of the University of Tsukuba

is a public university, public research university located in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, Ibaraki, Japan. It is a top 10 Designated National University, and was ranked Type A by the Japanese government as part of the Top Global University Pro ...

and Shibaura Institute of Technology

The , abbreviated as , is a private university of Technology in Japan, with campuses located in Tokyo and Saitama. Established in 1927 as the Tokyo Higher School of Industry and Commerce, it was chartered as a university in 1949.

The Shibaura I ...

. Since 2006 he is the president of Yokohama College of Pharmacy. Esaki is also the recipient of The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence, the Order of Culture

The is a Japanese order, established on February 11, 1937. The order has one class only, and may be awarded to men and women for contributions to Japan's art, literature, science, technology, or anything related to culture in general; recipient ...

(1974) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight ...

(1998).

In recognition of three Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ou ...

' contributions, the bronze statues of Shin'ichirō Tomonaga

, usually cited as Sin-Itiro Tomonaga in English, was a Japanese physicist, influential in the development of quantum electrodynamics, work for which he was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 along with Richard Feynman and Julian ...

, Leo Esaki, and Makoto Kobayashi were set up in the Central Park of Azuma 2 in Tsukuba City in 2015.

After the death of Yoichiro Nambu

was a Japanese-American physicist and professor at the University of Chicago. Known for his contributions to the field of theoretical physics, he was awarded half of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2008 for the discovery in 1960 of the mechanism ...

in 2015, Esaki is the eldest Japanese Nobel laureate.

His daughter, Ana Esaki, is married to Craig S. Smith, former Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

bureau chief of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

bureau chief of ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

''.

Recognition

Awards and honors

*1959 –Nishina Memorial Prize

The is the oldest and most prestigious physics award in Japan.

Information

Since 1955, the Nishina Memorial Prize has been awarded annually by the Nishina Memorial Foundation. The Foundation was established to commemorate Yoshio Nishina, who w ...

*1960 – Asahi Prize

The , established in 1929, is an award presented by the Japanese newspaper ''Asahi Shimbun'' and Asahi Shimbun Foundation to honor individuals and groups that have made outstanding accomplishments in the fields of arts and academics and have greatl ...

*1961 – Stuart Ballantine Medal

{{notability, date=February 2018

The Stuart Ballantine Medal was a science and engineering award presented by the Franklin Institute, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. It was named after the US inventor Stuart Ballantine.

Laureates

*1947 - Geo ...

*1965 – Japan Academy Prize

*1973 – Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

*1974 – Order of Culture

The is a Japanese order, established on February 11, 1937. The order has one class only, and may be awarded to men and women for contributions to Japan's art, literature, science, technology, or anything related to culture in general; recipient ...

*1985 – James C. McGroddy Prize for New Materials

*1989 – Harold Pender Award The Harold Pender Award, initiated in 1972 and named after founding Dean Harold Pender, is given by the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science of the University of Pennsylvania to an outstanding member of the engineering professi ...

*1991 – IEEE Medal of Honor

The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest recognition of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It has been awarded since 1917, when its first recipient was Major Edwin H. Armstrong. It is given for an exceptional contributio ...

*1998 – Japan Prize

*1998 – Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight ...

*2001 – Honorary Doctor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) is a public research university in Clear Water Bay Peninsula, New Territories, Hong Kong. Founded in 1991 by the British Hong Kong Government, it was the territory's third institution ...

*2007 – Honorary Distinguished Professor at the National Tsing Hua University

National Tsing Hua University (NTHU; ) is a public research university in Hsinchu City, Taiwan.

National Tsing Hua University was first founded in Beijing. After the Chinese Civil War, the then-president of the university, Mei Yiqi, and othe ...

Membership in learned societies

*1960 Fellow of the American Physical Society *Physical Society of Japan The Physical Society of Japan (JPS; 日本物理学会 in Japanese) is the organisation of physicists in Japan. There are about 16,000 members, including university professors, researchers as well as educators, and engineers.

The origins of the JP ...

*1975 – Member, the Japan Academy

The Japan Academy (Japanese: 日本学士院, ''Nihon Gakushiin'') is an honorary organisation and science academy founded in 1879 to bring together leading Japanese scholars with distinguished records of scientific achievements. The Academy is c ...

*1976 – Foreign Associate, National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

*1977 – Foreign Associate, National Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Engineering is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy ...

*1989 – Member, Max Planck Society

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (german: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e. V.; abbreviated MPG) is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes. ...

*1991 – Member, American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

*1994 – Foreign Member, Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

*1995 – Honorary Foreign Member, Korean Academy of Science and Technology

The Korean Academy of Science and Technology (KAST) is South Korea's highest academy of science and serves as an integrated think-tank for the country's science and technology. It contributes to national development by promoting science and techn ...

*1996 – Member, Accademia dei Lincei

The Accademia dei Lincei (; literally the "Academy of the Lynx-Eyed", but anglicised as the Lincean Academy) is one of the oldest and most prestigious European scientific institutions, located at the Palazzo Corsini on the Via della Lungara in Rom ...

See also

*List of Japanese Nobel laureates

Since 1949, there have been 29 Japanese List of Nobel laureates, laureates of the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize is a Sweden-based international monetary prize. The award was established by the 1895 will and estate of Swedish chemist and inventor ...

* List of Nobel laureates affiliated with the University of Tokyo

This list of Nobel laureates by university affiliation shows the university affiliations of individual winners of the Nobel Prize since 1901 and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences since 1969. The affiliations are those at the time of th ...

References

Further reading

*Large scale integrated circuits technology: state of the art and prospects, ''proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on "Large Scale Integrated Circuits Technology: State of the Art and Prospects," Erice, Italy, July 15–27, 1981 ''/ edited by Leo Esaki and Giovanni Soncini (1982) *''Highlights in condensed matter physics and future prospects'' / edited by Leo Esaki (1991)External links

* including the Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1973 ''Long Journey into Tunnelling''IBM record

* IEEE History Center – Leo Esaki. Retrieved July 19, 2011 fro

Leo Esaki - Engineering and Technology History Wiki

* Sony History – The Esaki Diode. Retrieved August 5, 2003 fro

{{DEFAULTSORT:Esaki, Leo 1925 births Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society IBM Fellows IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Japanese Nobel laureates 20th-century Japanese physicists Japanese nanotechnologists 20th-century Japanese inventors Kwansei Gakuin University faculty Kyoto University faculty Living people Nobel laureates in Physics People from Higashiōsaka Semiconductor physicists Recipients of the Order of Culture University of Tsukuba faculty Foreign associates of the National Academy of Engineering University of Tokyo alumni