Leitmeritz Concentration Camp on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leitmeritz was the largest

The estimated cost of establishing Maybach production at Leitmeritz was 10 to 20 million

The estimated cost of establishing Maybach production at Leitmeritz was 10 to 20 million

The camp itself was located in a former Czechoslovak Army base. The SS guards and administrators as well as civilian laborers lived in the original soldiers' quarters, while prisoners were warehoused in the former stables, indoor riding arena, and storage depot, which were surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence and seven watchtowers. During mid-1944, the prisoners renovated the buildings in order to house more prisoners. A kitchen was set up in June 1944 and the infirmary was built around September. Additional barracks were built during the winter of 1944–1945 to accommodate increases in the prisoner population. By April 1945, seven additional barracks had been built for prisoners while an additional two were planned. The capacity was 4,300 men—which had already been exceeded—and 1,000 women in the separate women's camp.

Despite the continual increase in the number of prisoners, not enough accommodation was built, resulting in serious overcrowding and major problems with hygiene. Rations of food were completely inadequate. The rate of infectious disease, especially

The camp itself was located in a former Czechoslovak Army base. The SS guards and administrators as well as civilian laborers lived in the original soldiers' quarters, while prisoners were warehoused in the former stables, indoor riding arena, and storage depot, which were surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence and seven watchtowers. During mid-1944, the prisoners renovated the buildings in order to house more prisoners. A kitchen was set up in June 1944 and the infirmary was built around September. Additional barracks were built during the winter of 1944–1945 to accommodate increases in the prisoner population. By April 1945, seven additional barracks had been built for prisoners while an additional two were planned. The capacity was 4,300 men—which had already been exceeded—and 1,000 women in the separate women's camp.

Despite the continual increase in the number of prisoners, not enough accommodation was built, resulting in serious overcrowding and major problems with hygiene. Rations of food were completely inadequate. The rate of infectious disease, especially

The Elsabe production lines were dismantled and shipped to the Soviet Union as

The Elsabe production lines were dismantled and shipped to the Soviet Union as

Timeline of the camp

by Terezín Memorial

Exhumation of victimsTestimonies

at the

subcamp

Subcamps (german: KZ-Außenlager), also translated as satellite camps, were outlying detention centres (''Haftstätten'') that came under the command of a main concentration camp run by the SS in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe. The Nazi ...

of the Flossenbürg concentration camp

Flossenbürg was a Nazi concentration camp built in May 1938 by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Unlike other concentration camps, it was located in a remote area, in the Fichtel Mountains of Bavaria, adjacent to the town of F ...

, operated by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in Leitmeritz, Reichsgau Sudetenland

The Reichsgau Sudetenland was an administrative division of Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945. It comprised the northern part of the '' Sudetenland'' territory, which was annexed from Czechoslovakia according to the 30 September 1938 Munich Agreement. ...

(now Litoměřice, Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

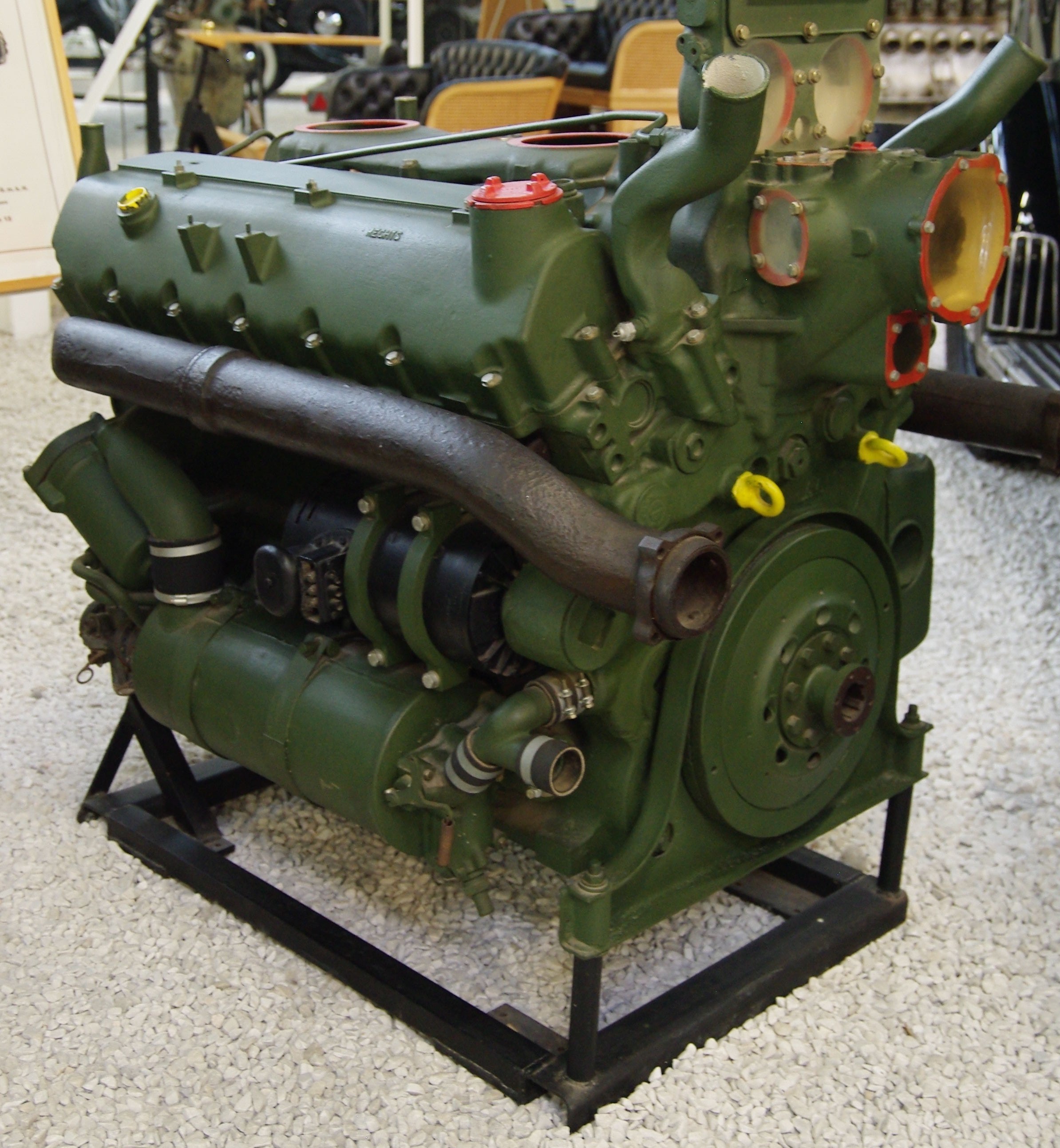

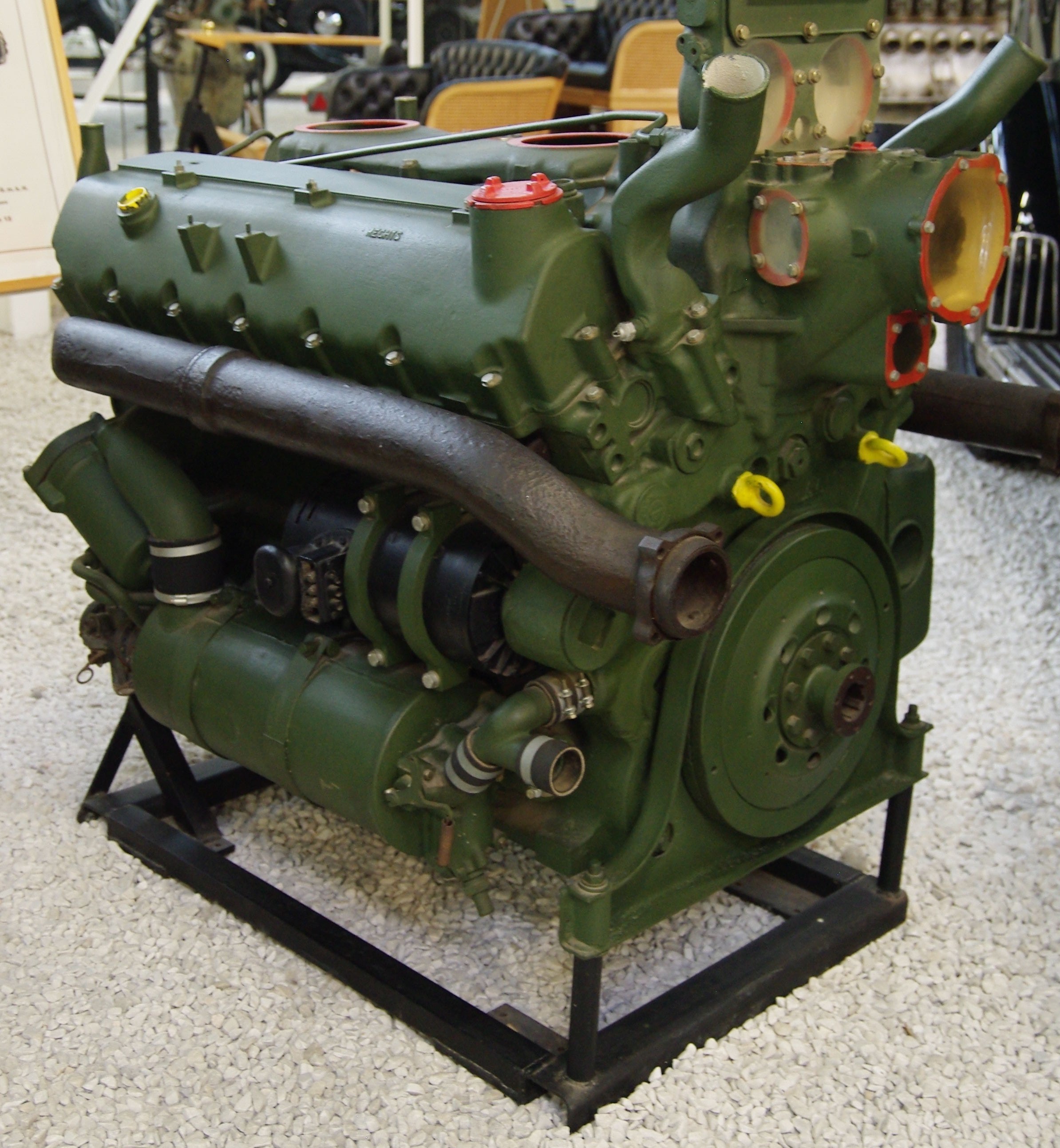

). Established on 24 March 1944 as part of an effort to disperse and increase war production, its prisoners were forced to work in the caverns Richard I and II, producing Maybach HL230

The Maybach HL230 was a water-cooled 60° 23 litre V12 petrol engine designed by Maybach. It was used during World War II in heavy German tanks, namely the Panther, Jagdpanther, Tiger II, Jagdtiger (HL230 P30), and later versions of the Tiger I ...

tank engines for Auto Union

Auto Union AG, was an amalgamation of four German automobile manufacturers, founded in 1932 and established in 1936 in Chemnitz, Saxony. It is the immediate predecessor of Audi as it is known today.

As well as acting as an umbrella firm f ...

(now Audi

Audi AG () is a German automotive manufacturer of luxury vehicles headquartered in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. As a subsidiary of its parent company, the Volkswagen Group, Audi produces vehicles in nine production facilities worldwide.

Th ...

) and preparing the second site for intended production of tungsten and molybdenum wire and sheet metal by Osram. Of the 18,000 prisoners who passed through the camp, about 4,500 died due to disease, malnutrition, and accidents caused by the disregard for safety by the SS staff who administered the camp. In the last weeks of the war, the camp became a hub for death marches

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

. The camp operated until 8 May 1945, when it was dissolved by the German surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

.

Establishment

During the last year of the war, theconcentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

prisoner population reached its peak. The SS deployed hundreds of thousands of prisoners on war-related forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

projects, including some of the most important to the war effort. In the meantime, many war factories had been bombed by the Allies, leading to the decision to disperse production. In 1943, the Auto Union

Auto Union AG, was an amalgamation of four German automobile manufacturers, founded in 1932 and established in 1936 in Chemnitz, Saxony. It is the immediate predecessor of Audi as it is known today.

As well as acting as an umbrella firm f ...

factory in Chemnitz-Siegmar was ordered to be turned over to the production of Maybach HL230

The Maybach HL230 was a water-cooled 60° 23 litre V12 petrol engine designed by Maybach. It was used during World War II in heavy German tanks, namely the Panther, Jagdpanther, Tiger II, Jagdtiger (HL230 P30), and later versions of the Tiger I ...

tank engines, much in demand due to attrition on the Eastern Front. By late 1943, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

(head of the Four Year Plan

The Four Year Plan was a series of economic measures initiated by Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany in 1936. Hitler placed Hermann Göring in charge of these measures, making him a Reich Plenipotentiary (Reichsbevollmächtigter) whose jurisdiction cut a ...

for war production, which involved mass forced labor) was planning to disperse the Maybach production from the Chemnitz plant to an underground factory under Radobýl Mountain just west of the town of Leitmeritz (now Litoměřice in the Czech Republic). Although there was an existing quarry, the facility had to be expanded in order to accommodate planned spaces for production and assembly several kilometers long. The site was located in Reichsgau Sudetenland

The Reichsgau Sudetenland was an administrative division of Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945. It comprised the northern part of the '' Sudetenland'' territory, which was annexed from Czechoslovakia according to the 30 September 1938 Munich Agreement. ...

, a territory of Czechoslovakia that had been annexed to Germany in 1938 following the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

.

The largest subcamp

Subcamps (german: KZ-Außenlager), also translated as satellite camps, were outlying detention centres (''Haftstätten'') that came under the command of a main concentration camp run by the SS in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe. The Nazi ...

of Flossenbürg concentration camp

Flossenbürg was a Nazi concentration camp built in May 1938 by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Unlike other concentration camps, it was located in a remote area, in the Fichtel Mountains of Bavaria, adjacent to the town of F ...

, Leitmeritz was one of the largest of the subcamps in the Sudetenland, whose remote location was favored for armaments production because it was not easily accessible to Allied bombers. Official names for the camp included "SS Kommando B 5", "Außenkommando

Subcamps (german: KZ-Außenlager), also translated as satellite camps, were outlying detention centres (''Haftstätten'') that came under the command of a main concentration camp run by the SS in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe. The Naz ...

Leitmeritz" and "Arbeitslager

''Arbeitslager'' () is a German language word which means labor camp. Under Nazism, the German government (and its private-sector, Axis, and collaborator partners) used forced labor extensively, starting in the 1930s but most especially during ...

Leitmeritz". The camp was located west of downtown Leitmeritz, distant from Theresienstadt Ghetto

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination cam ...

in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

, a transit ghetto for Jews.

The camp was established by a transport of 500 men from Dachau concentration camp

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

, who arrived at nearby Theresienstadt Small Fortress

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination cam ...

on 24 or 25 March 1944. Due to the lack of accommodation at the work site, they stayed at the Small Fortress (temporarily a Flossenbürg subcamp) until June. The Small Fortress was away from the Leitmeritz camp site. From 27 March, they went each day to work in Leitmeritz. By early April, there were also 740 civilian workers, mostly skilled, and 100 prisoners were sent back to Dachau.

Slave labor

In May 1944, the authority (SS Leadership Staff) B 5, under the authority of SS magnate Hans Kammler, was created to oversee the forced labor projects at Leitmeritz. The companies involved, Auto Union and Osram, worked closely with both the B 5 and theReich Ministry of Armaments and War Production

The Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production () was established on March 17, 1940, in Nazi Germany. Its official name before September 2, 1943, was the 'Reichsministerium für Bewaffnung und Munition' ().

Its task was to improve the sup ...

. The SS shell company

A shell corporation is a company or corporation that exists only on paper and has no office and no employees, but may have a bank account or may hold passive investments or be the registered owner of assets, such as intellectual property, or s ...

, Mineral-Öl – Baugesellschaft m.b.H., set up to subcontract construction tasks, hired many enterprises from Germany, the Sudetenland and the Protectorate for various roles involving the camp. There was continual conflict between the SS and the companies because the goal of terrorizing and killing prisoners by extermination through labor

Extermination through labour (or "extermination through work", german: Vernichtung durch Arbeit) is a term that was adopted to describe forced labor in Nazi concentration camps in light of the high mortality rate and poor conditions; in some ...

was incompatible with the aim of securing the highest production possible. Whether they were working on the camp or underground, prisoners were not given appropriate equipment and even the most basic safety precautions were not followed. Many prisoners died in accidents due to these deliberately murderous working conditions. Almost every day, the tunnels suffered collapses; 60 prisoners died in just one such incident in May 1944.

Richard I

The estimated cost of establishing Maybach production at Leitmeritz was 10 to 20 million

The estimated cost of establishing Maybach production at Leitmeritz was 10 to 20 million Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

s, equivalent to at the time or $– million in dollars. In early April 1944, the SS' goal was to begin production of the engines by July, which would have required 3,500 prisoners. However, the SS withdrew from the project—possibly because it was unwilling to accept the responsibility for a risky project—and it was taken over by (GB-Bau, "Office of General Representative for Regulation of the Construction Industry"), part of the Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production. On 30 April, Hitler ordered that the dispersal to Leitmeritz be expedited because the Maybach plant in Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''Kre ...

had been bombed by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

on the night of 27–28 April. From early May, the SS took over the project again.

On 11 September 1944, the Auto Union plant in Chemnitz-Siegmar was bombed. Between 25 September and 30 October, the two most important production lines of components—cylinder head

In an internal combustion engine, the cylinder head (often abbreviated to simply "head") sits above the cylinders and forms the roof of the combustion chamber.

In sidevalve engines, the head is a simple sheet of metal; whereas in more modern ov ...

s and crankcases—were transferred to the underground factory at Leitmeritz, comprising 180 machines in total. From 3 November, entire Maybach HL230 engines were manufactured in Leitmeritz; the first was completed on 14 November. The production lines were manned by selected skilled prisoners whose detachment was known as Elsabe AG. The lack of air circulation in the underground factory exacerbated the illness and exhaustion of many inmates and rusted the production machines, causing many of the completed products to fail quality control. In February, the command made efforts to improve the conditions for Elsabe prisoners in order to reduce death rates. The prisoners were housed separately in a warehouse with washrooms and given increased rations of food, while they did not have to participate in as many roll calls. Production at Richard I continued until 5 May 1945.

Richard II

On 15 May 1944, the Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production decided to use Leitmeritz to expand the production of tungsten and molybdenum wire and sheet metal produced by Osram's Berlin factory. For this, of underground floor space was required as well as 300 civilian workers and 600 prisoners. The Hamburg company Robert Kieserling was contracted to construct this space. The cover name of Osram operating in Leitmeritz was Kalkspat K.G., which was responsible for machinery, power, access roads, and accommodation for civilian workers. Production was scheduled to begin by the end of 1944, but none ever took place because Osram executives recognized the hopelessness of the war situation.Command

This first commandant, Schreiber, arrived with a contingent of 10 SS men who accompanied the transport. Schreiber was replaced by Erich von Berg within a few months. The third commandant, Völkner, tried to improve conditions for prisoners but was replaced in November by Heiling, who had the most brutal reputation of the SS leaders. From February 1945, Benno Brückner was the commandant. The of the camp had the greatest control over camp conditions. All three of them— Willi Czibulka in 1944, Kurt Panicke through March 1945 and Karl Opitz—had a reputation for arbitrary cruelty. Supervising prisoners in their barracks was the responsibility of the block leaders, while the Labor Operations Department (commanded by Tilling and later Piasek) oversaw labor deployment. The Political Department was headed originally by Willi Bacher and later by Hans Rührmeyer. Hans Kohn initially commanded the supply department. In 1945, Kohn was put in charge of the prisoners' kitchen and Günter Schmidt and Eduard Schwarz succeeded him. There was a separate command for B 5, headed first by Werner Meyer, and from November 1944 Alfons Kraft. Initially, the camp was guarded by thirty Luftwaffe guards, who reported to the Fighter Staff command in Nordhausen. The first commander of the guard was Emanuel Fritz, a former prosecutor from Vienna, who was replaced by Jelinek in mid-1944 and Edmund Johann in November. As the camp expanded, the number of Luftwaffe guards increased to as many as 300, who had been seconded from Vienna, Leipzig and Buchenwald. Guards who shot a prisoner were rewarded with leave and a commendation.Prisoners

By August 1944, there were more than 2,800 prisoners, which increased further to 5,000 by November. In April 1945, the population peaked at 9,000, nearly as many as were held in the Flossenbürg main camp. An estimated 18,000 people passed through the camp. The plurality of prisoners came from Flossenbürg (3,649); large numbers also came fromGross-Rosen

Gross-Rosen was a network of Nazi concentration camps built and operated by Nazi Germany during World War II. The main camp was located in the German village of Gross-Rosen, now the modern-day Rogoźnica, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Rogoźnica in ...

(3,253), Auschwitz II-Birkenau

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

(1,995), and Dachau (1,441). In March and April 1945, 2,000 people were deported to Leitmeritz from various Flossenbürg subcamps and 800 from subcamps of Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

due to the advance of Allied armies. Leitmeritz began as a male camp, but from February to April 1945, 770 women also were imprisoned at the site, to work for Osram. An unusually high number of the prisoners, about 3,600 or 4,000, were Jews, most of whom were from Poland and the first of whom arrived on 9 August 1944. By country of origin, the largest groups were Poles (almost 9,000), Soviet citizens (3,500), Germans (950), Hungarians (850), French (800), Yugoslavs (more than 600) and Czechs (more than 500).

Conditions

The camp itself was located in a former Czechoslovak Army base. The SS guards and administrators as well as civilian laborers lived in the original soldiers' quarters, while prisoners were warehoused in the former stables, indoor riding arena, and storage depot, which were surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence and seven watchtowers. During mid-1944, the prisoners renovated the buildings in order to house more prisoners. A kitchen was set up in June 1944 and the infirmary was built around September. Additional barracks were built during the winter of 1944–1945 to accommodate increases in the prisoner population. By April 1945, seven additional barracks had been built for prisoners while an additional two were planned. The capacity was 4,300 men—which had already been exceeded—and 1,000 women in the separate women's camp.

Despite the continual increase in the number of prisoners, not enough accommodation was built, resulting in serious overcrowding and major problems with hygiene. Rations of food were completely inadequate. The rate of infectious disease, especially

The camp itself was located in a former Czechoslovak Army base. The SS guards and administrators as well as civilian laborers lived in the original soldiers' quarters, while prisoners were warehoused in the former stables, indoor riding arena, and storage depot, which were surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence and seven watchtowers. During mid-1944, the prisoners renovated the buildings in order to house more prisoners. A kitchen was set up in June 1944 and the infirmary was built around September. Additional barracks were built during the winter of 1944–1945 to accommodate increases in the prisoner population. By April 1945, seven additional barracks had been built for prisoners while an additional two were planned. The capacity was 4,300 men—which had already been exceeded—and 1,000 women in the separate women's camp.

Despite the continual increase in the number of prisoners, not enough accommodation was built, resulting in serious overcrowding and major problems with hygiene. Rations of food were completely inadequate. The rate of infectious disease, especially tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, was very high; at the end of 1944 many prisoners were x-rayed

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30 ...

, showing that nearly half had the disease. By February 1945, a third of prisoners were incapacitated by disease, preventing sufficient prisoners from being mustered for slave labor. As a result, the companies constantly had to train new prisoners. Initially the prisoners were grouped in quarters based on the transport they arrived in; later they were organized by work group but not nationality as was typical elsewhere.

Prisoners called it the "death factory"; about 4,500 prisoners died at the camp. According to records, 150 people died through November 1944 and after that the mortality rate climbed, with 706 deaths in December, 934 in January 1945, and 862 in February. The increase in the death rate coincided with the arrival of Jewish prisoners. The Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occ ...

detainees were specifically targeted by the kapo

A kapo or prisoner functionary (german: Funktionshäftling) was a prisoner in a Nazi camp who was assigned by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) guards to supervise forced labor or carry out administrative tasks.

Also called "prisoner self-administrat ...

s and SS guards; a third did not survive. Victims were first cremated at the at the Small Fortress. Due to the large number of deaths, another crematorium was built at Leitmeritz in April. The remains of 66 others, who had been buried in seven mass graves, were exhumed in 1946; another 723 bodies were found in a long anti-tank ditch. After the war, these victims were reburied in the . Before the evacuation of the camp, 3,869 prisoners, primarily those unable to work, were sent to other camps, including 1,657 to Flossenbürg and its subcamps and 1,200 (suffering from typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

and dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

) to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

Bergen-Belsen , or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, in 1943, parts of it became a concent ...

. Their fate is not known.

Dissolution

In the last week of the war, Leitmeritz was a hub for manydeath marches

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

. Thousands of prisoners arrived at the camp, where there was no space for them. Some prisoners had to sleep outside while others, during the last few days of the war, slept in the tunnels. Prisoners were bundled into almost 100 transports and deported south into Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. The number of deaths during the evacuation is unknown. About 1,222 prisoners, mostly Jewish men—some from Leitmeritz itself, others who had arrived after death marches from elsewhere—ended up in Theresienstadt Ghetto. However, some of them may have been sent there after liberation. Ninety-eight died in Theresienstadt.

After Flossenbürg main camp was liberated by the United States Army on 23 April 1945, Leitmeritz continued to operate, administering nearby concentration camps such as Lobositz

Lovosice (; german: Lobositz) is a town in Litoměřice District in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 8,600 inhabitants. It is an industrial town.

Geography

Lovosice is located about southwest of Litoměřice and ...

. On the afternoon of 5 May, Panicke summoned the prisoners to announce that the war was over and they would be released. Between 6 and 8 May, many prisoners received certificates for their release. The camp was officially dissolved by the German Instrument of Surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

on 8 May. On 9–10 May, 5th Guards Army of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

arrived at the site, finding 1,200 sick prisoners who had been left behind. The Czechoslovak militia guarded the site until 16 May, when it was taken over by the Red Army. Parts of the Soviet and Czech medical missions to Theresienstadt were diverted to Leitmeritz. The last prisoners were repatriated in July 1945.

Aftermath

The Elsabe production lines were dismantled and shipped to the Soviet Union as

The Elsabe production lines were dismantled and shipped to the Soviet Union as war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

, while the barracks were returned to use by the Czechoslovak Army, and used until 2003. The crematorium is the only part of the former camp open to the public. Nearby, a memorial to the victims of the camp designed by the Czech artist , was unveiled in 1992. The memorial and the surviving archives of the former camp are administered by the . Leitmeritz is known as "one of the most infamous and best researched Flossenbürg subcamps"; the Terezín Memorial has sponsored research into the camp's history. In 2014, Audi

Audi AG () is a German automotive manufacturer of luxury vehicles headquartered in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. As a subsidiary of its parent company, the Volkswagen Group, Audi produces vehicles in nine production facilities worldwide.

Th ...

(the successor to Auto Union) released a report by Audi historian Martin Kukowski and Chemnitz University of Technology

Chemnitz (; from 1953 to 1990: Karl-Marx-Stadt , ) is the third-largest city in the German state of Saxony after Leipzig and Dresden. It is the 28th largest city of Germany as well as the fourth largest city in the area of former East Germany a ...

academic that it had commissioned into its activity during the Nazi era. According to the report, the company bore "moral responsibility" for the 4,500 deaths that occurred at Leitmeritz.

In 1946, former Karl Opitz was convicted of responsibility for the execution of thirty prisoners and sentenced to life in prison by a Czechoslovak court. In 1974, former guard Henryk Matuszkowiak was convicted and sentenced to death in Poland for committing fourteen murders at Leitmeritz. In 2001, was convicted by a German court of murdering seven Jewish prisoners in an anti-tank trench in the spring of 1945, despite having claimed to be in Vienna when the murders were committed. The information which led to his conviction was given by a Hungarian-born former SS man, Adalbert Lallier. More than 360 witnesses were interviewed by the prosecutors.

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Timeline of the camp

by Terezín Memorial

Exhumation of victims

at the

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust. Adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the USHMM provides for the documentation, study, and interpretation of Holocaust hi ...

{{Authority control

Auto Union

Litoměřice

Nazi concentration camps in Czechoslovakia

Subcamps of Flossenbürg