Le Sacre du printemps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, image = Roerich Rite of Spring.jpg

, image_size = 350px

, caption = Concept design for act 1, part of

Paris , ballet_company =

Lawrence Morton, in a study of the origins of ''The Rite'', records that in 1907–08 Stravinsky set to music two poems from

Lawrence Morton, in a study of the origins of ''The Rite'', records that in 1907–08 Stravinsky set to music two poems from

Taruskin has listed a number of sources that Roerich consulted when creating his designs. Among these are the ''

Taruskin has listed a number of sources that Roerich consulted when creating his designs. Among these are the ''

Paris's

Paris's  At that time, a Parisian ballet audience typically consisted of two diverse groups: the wealthy and fashionable set, who would be expecting to see a traditional performance with beautiful music, and a "Bohemian" group who, the poet-philosopher

At that time, a Parisian ballet audience typically consisted of two diverse groups: the wealthy and fashionable set, who would be expecting to see a traditional performance with beautiful music, and a "Bohemian" group who, the poet-philosopher

After the opening Paris run and the London performances, events conspired to prevent further stagings of the ballet. Nijinsky's choreography, which

After the opening Paris run and the London performances, events conspired to prevent further stagings of the ballet. Nijinsky's choreography, which

In 1944 Massine began a new collaboration with Roerich, who before his death in 1947 completed a number of sketches for a new production which Massine brought to fruition at

In 1944 Massine began a new collaboration with Roerich, who before his death in 1947 completed a number of sketches for a new production which Massine brought to fruition at

one two three four five six seven eight

one ''two'' three ''four'' five six seven eight

one ''two'' three four ''five'' six seven eight

''one'' two three four five ''six'' seven eight

According to Roger Nichols "At first sight there seems no pattern in the distribution of accents to the stamping chords. Taking the initial quaver of bar 1 as a natural accent we have for the first outburst the following groups of quavers: 9, 2, 6, 3, 4, 5, 3. However, these apparently random numbers make sense when split into two groups:

9 6 4 3

2 3 5

Clearly the top line is decreasing, the bottom line increasing, and by respectively decreasing and increasing amounts ...Whether Stravinsky worked them out like this we shall probably never know. But the way two different rhythmic 'orders' interfere with each other to produced apparent chaos is... a typically Stravinskyan notion."

The "Ritual of Abduction" which follows is described by Hill as "the most terrifying of musical hunts". It concludes in a series of flute trills that usher in the "Spring Rounds", in which a slow and laborious theme gradually rises to a dissonant fortissimo, a "ghastly caricature" of the episode's main tune.

Brass and percussion predominate as the "Ritual of the Rival Tribes" begins. A tune emerges on tenor and bass tubas, leading after much repetition to the entry of the Sage's procession. The music then comes to a virtual halt, "bleached free of colour" (Hill), as the Sage blesses the earth. The "Dance of the Earth" then begins, bringing Part I to a close in a series of phrases of the utmost vigour which are abruptly terminated in what Hill describes as a "blunt, brutal amputation".Hill, pp. 72–73

The first published score was the four-hand piano arrangement (Editions Russes#Names of imprints, Edition Russe de Musique, RV196), dated 1913. Publication of the full orchestral score was prevented by the outbreak of war in August 1914. After the revival of the work in 1920 Stravinsky, who had not heard the music for seven years, made numerous revisions to the score, which was finally published in 1921 (Edition Russe de Musique, RV 197/197b. large and pocket scores).

In 1922 Ansermet, who was preparing to perform the work in Berlin, sent to Stravinsky a list of errors he had found in the published score. In 1926, as part of his preparation for that year's performance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Stravinsky rewrote the "Evocation of the Ancestors" section and made substantial changes to the "Sacrificial Dance". The extent of these revisions, together with Ansermet's recommendations, convinced Stravinsky that a new edition was necessary, and this appeared in large and pocket form in 1929. It did not, however, incorporate all of Ansermet's amendments and, confusingly, bore the date and RV code of the 1921 edition, making the new edition hard to identify.

Stravinsky continued to revise the work, and in 1943 rewrote the "Sacrificial Dance". In 1948 Boosey & Hawkes issued a corrected version of the 1929 score (B&H 16333), although Stravinsky's substantial 1943 amendment of the "Sacrificial Dance" was not incorporated into the new version and remained unperformed, to the composer's disappointment. He considered it "much easier to play ... and superior in balance and sonority" to the earlier versions. A less musical motive for the revisions and corrected editions was copyright law. The composer had left Galaxy Music Corporation (agents for Editions Russe de la Musique, the original publisher) for Associated Music Publishers at the time, and orchestras would be reluctant to pay a second rental charge from two publishers to match the full work and the revised Sacrificial Dance; moreover, the revised dance could only be published in America. The 1948 score provided copyright protection to the work in America, where it had lapsed, but Boosey (who acquired the Editions Russe catalogue) did not have the rights to the revised finale.

The 1929 score as revised in 1948 forms the basis of most modern performances of ''The Rite.'' Boosey & Hawkes reissued their 1948 edition in 1965, and produced a newly engraved edition (B&H 19441) in 1967. The firm also issued an unmodified reprint of the 1913 piano reduction in 1952 (B&H 17271) and a revised piano version, incorporating the 1929 revisions, in 1967.

The Paul Sacher Foundation, in association with Boosey & Hawkes, announced in May 2013, as part of ''The Rite''s centenary celebrations, their intention to publish the 1913 autograph score, as used in early performances. After being kept in Russia for decades, the autograph score was acquired by Boosey & Hawkes in 1947. The firm presented the score to Stravinsky in 1962, on his 80th birthday. After the composer's death in 1971 the manuscript was acquired by the Paul Sacher Foundation. As well as the autograph score, they have published the manuscript piano four-hands score.

In 2000, Edwin F. Kalmus, Kalmus Music Publishers brought out an edition where former Philadelphia Orchestra librarian Clint Nieweg made over 21,000 corrections to the score and parts. Since then a published errata list has added some 310 more corrections, and this is considered to be the most accurate version of the work as of 2013.

The first published score was the four-hand piano arrangement (Editions Russes#Names of imprints, Edition Russe de Musique, RV196), dated 1913. Publication of the full orchestral score was prevented by the outbreak of war in August 1914. After the revival of the work in 1920 Stravinsky, who had not heard the music for seven years, made numerous revisions to the score, which was finally published in 1921 (Edition Russe de Musique, RV 197/197b. large and pocket scores).

In 1922 Ansermet, who was preparing to perform the work in Berlin, sent to Stravinsky a list of errors he had found in the published score. In 1926, as part of his preparation for that year's performance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Stravinsky rewrote the "Evocation of the Ancestors" section and made substantial changes to the "Sacrificial Dance". The extent of these revisions, together with Ansermet's recommendations, convinced Stravinsky that a new edition was necessary, and this appeared in large and pocket form in 1929. It did not, however, incorporate all of Ansermet's amendments and, confusingly, bore the date and RV code of the 1921 edition, making the new edition hard to identify.

Stravinsky continued to revise the work, and in 1943 rewrote the "Sacrificial Dance". In 1948 Boosey & Hawkes issued a corrected version of the 1929 score (B&H 16333), although Stravinsky's substantial 1943 amendment of the "Sacrificial Dance" was not incorporated into the new version and remained unperformed, to the composer's disappointment. He considered it "much easier to play ... and superior in balance and sonority" to the earlier versions. A less musical motive for the revisions and corrected editions was copyright law. The composer had left Galaxy Music Corporation (agents for Editions Russe de la Musique, the original publisher) for Associated Music Publishers at the time, and orchestras would be reluctant to pay a second rental charge from two publishers to match the full work and the revised Sacrificial Dance; moreover, the revised dance could only be published in America. The 1948 score provided copyright protection to the work in America, where it had lapsed, but Boosey (who acquired the Editions Russe catalogue) did not have the rights to the revised finale.

The 1929 score as revised in 1948 forms the basis of most modern performances of ''The Rite.'' Boosey & Hawkes reissued their 1948 edition in 1965, and produced a newly engraved edition (B&H 19441) in 1967. The firm also issued an unmodified reprint of the 1913 piano reduction in 1952 (B&H 17271) and a revised piano version, incorporating the 1929 revisions, in 1967.

The Paul Sacher Foundation, in association with Boosey & Hawkes, announced in May 2013, as part of ''The Rite''s centenary celebrations, their intention to publish the 1913 autograph score, as used in early performances. After being kept in Russia for decades, the autograph score was acquired by Boosey & Hawkes in 1947. The firm presented the score to Stravinsky in 1962, on his 80th birthday. After the composer's death in 1971 the manuscript was acquired by the Paul Sacher Foundation. As well as the autograph score, they have published the manuscript piano four-hands score.

In 2000, Edwin F. Kalmus, Kalmus Music Publishers brought out an edition where former Philadelphia Orchestra librarian Clint Nieweg made over 21,000 corrections to the score and parts. Since then a published errata list has added some 310 more corrections, and this is considered to be the most accurate version of the work as of 2013.

"100 years on: Igor Stravinsky on ''The Rite of Spring''

by Robert Craft, ''The Times Literary Supplement'', 19 June 2013

Multimedia Web Site – Keeping Score: Revolutions in Music: Stravinsky's ''The Rite of Spring''

* :iarchive:StravinskyLeSacreDuPrintemps, First 1929 orchestral recording conducted by the composer in MP3 format

Performance of Stravinsky's four-hand piano arrangement of ''The Rite of Spring''

by Jonathan Biss and Jeremy Denk from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in MP3 format *

''The Rite of Spring'': 'The work of a madman'

by Tom Service, ''The Guardian'', 13 February 2013

BBC Proms 2011 Stravinsky's ''Rite of Spring''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rite of Spring, The 1913 ballet premieres 1913 compositions Art works that caused riots Ballet controversies Ballets by Igor Stravinsky Ballets designed by Nicholas Roerich Ballets by Vaslav Nijinsky Ballets Russes productions Compositions that use extended techniques Film soundtracks Modernist compositions Music controversies Music riots

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

's designs for Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

's 1913 production of '

, composer = Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

, based_on = Pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

myths

, premiere =

, place = Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées () is an entertainment venue standing at 15 avenue Montaigne in Paris. It is situated near Avenue des Champs-Élysées, from which it takes its name. Its eponymous main hall may seat up to 1,905 people, while th ...

Paris , ballet_company =

Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. A ...

, choreographer = Vaslav Nijinsky

Vaslav (or Vatslav) Nijinsky (; rus, Вацлав Фомич Нижинский, Vatslav Fomich Nizhinsky, p=ˈvatsləf fɐˈmʲitɕ nʲɪˈʐɨnskʲɪj; pl, Wacław Niżyński, ; 12 March 1889/18908 April 1950) was a ballet dancer and choreog ...

, designer = Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

''The Rite of Spring''. Full name: ''The Rite of Spring: Pictures from Pagan Russia in Two Parts'' (french: Le Sacre du printemps: tableaux de la Russie païenne en deux parties) (french: Le Sacre du printemps, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

. It was written for the 1913 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

's Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. A ...

company; the original choreography was by Vaslav Nijinsky

Vaslav (or Vatslav) Nijinsky (; rus, Вацлав Фомич Нижинский, Vatslav Fomich Nizhinsky, p=ˈvatsləf fɐˈmʲitɕ nʲɪˈʐɨnskʲɪj; pl, Wacław Niżyński, ; 12 March 1889/18908 April 1950) was a ballet dancer and choreog ...

with stage designs and costumes by Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

. When first performed at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées () is an entertainment venue standing at 15 avenue Montaigne in Paris. It is situated near Avenue des Champs-Élysées, from which it takes its name. Its eponymous main hall may seat up to 1,905 people, while th ...

on 29 May 1913, the avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

nature of the music and choreography caused a sensation. Many have called the first-night reaction a "riot" or "near-riot", though this wording did not come about until reviews of later performances in 1924, over a decade later. Although designed as a work for the stage, with specific passages accompanying characters and action, the music achieved equal if not greater recognition as a concert piece and is widely considered to be one of the most influential musical works of the 20th century.

Stravinsky was a young, virtually unknown composer when Diaghilev recruited him to create works for the Ballets Russes. ''Le Sacre du printemps'' was the third such major project, after the acclaimed ''Firebird

Firebird and fire bird may refer to:

Mythical birds

* Phoenix (mythology), sacred firebird found in the mythologies of many cultures

* Bennu, Egyptian firebird

* Huma bird, Persian firebird

* Firebird (Slavic folklore)

Bird species

''Various sp ...

'' (1910) and ''Petrushka

Petrushka ( rus, Петру́шка, p=pʲɪtˈruʂkə, a=Ru-петрушка.ogg) is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry. Italian puppeteers introduced it in the first third of the 19th century. While most core characters came from Italy ...

'' (1911). The concept behind ''The Rite of Spring'', developed by Roerich from Stravinsky's outline idea, is suggested by its subtitle, "Pictures of Pagan Russia in Two Parts"; the scenario depicts various primitive rituals celebrating the advent of spring, after which a young girl is chosen as a sacrificial victim and dances herself to death. After a mixed critical reception for its original run and a short London tour, the ballet was not performed again until the 1920s, when a version choreographed by Léonide Massine

Leonid Fyodorovich Myasin (russian: Леони́д Фёдорович Мя́син), better known in the West by the French transliteration as Léonide Massine (15 March 1979), was a Russian choreographer and ballet dancer. Massine created the wo ...

replaced Nijinsky's original, which saw only eight performances. Massine's was the forerunner of many innovative productions directed by the world's leading choreographers, gaining the work worldwide acceptance. In the 1980s, Nijinsky's original choreography, long believed lost, was reconstructed by the Joffrey Ballet

The Joffrey Ballet is one of the premier dance companies and training institutions in the world today. Located in Chicago, Illinois, the Joffrey regularly performs classical and contemporary ballets during its annual performance season at Lyric O ...

in Los Angeles.

Stravinsky's score contains many novel features for its time, including experiments in tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is call ...

, metre

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its pref ...

, rhythm, stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

and dissonance. Analysts have noted in the score a significant grounding in Russian folk music

Russian folk music specifically deals with the folk music traditions of the ethnic Russian people.

Ethnic styles in the modern era

The performance and promulgation of ethnic music in Russia has a long tradition. Initially it was intertwined with ...

, a relationship Stravinsky tended to deny. Regarded as among the first modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

works, the music influenced many of the 20th-century's leading composers and is one of the most recorded works in the classical repertoire.

Background

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

was the son of Fyodor Stravinsky

Fyodor Ignatievich Stravinsky (russian: Фёдор Игнатьевич Страви́нский), , estate Novy Dvor (Aleksichi), Rechitsky Uyezd, Minsk Governorate ) was a Russian bass opera singer and actor. He was the father of Igor Stravins ...

, the principal bass singer at the Imperial Opera, Saint Petersburg, and Anna, née Kholodovskaya, a competent amateur singer and pianist from an old-established Russian family. Fyodor's association with many of the leading figures in Russian music, including Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

, Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

and Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

, meant that Igor grew up in an intensely musical home. In 1901 Stravinsky began to study law at Saint Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the G ...

while taking private lessons in harmony and counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

. Stravinsky worked under the guidance of Rimsky-Korsakov, having impressed him with some of his early compositional efforts. By the time of his mentor's death in 1908, Stravinsky had produced several works, among them a Piano Sonata in F minor (1903–04), a Symphony in E major (1907), which he catalogued as "Opus 1", and a short orchestral piece, ''Feu d'artifice

''Feu d'artifice'', Op. 4 (''Fireworks'', russian: Фейерверк, ) is a composition by Igor Stravinsky, written in 1908 and described by the composer as a "short orchestral fantasy." It usually takes less than four minutes to perform.

C ...

'' ("Fireworks", composed in 1908).

In 1909 ''Feu d'artifice'' was performed at a concert in Saint Petersburg. Among those in the audience was the impresario Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

, who at that time was planning to introduce Russian music and art to western audiences.White 1961, pp. 52–53 Like Stravinsky, Diaghilev had initially studied law, but had gravitated via journalism into the theatrical world. In 1907 he began his theatrical career by presenting five concerts in Paris; in the following year he introduced Mussorgsky's opera ''Boris Godunov

Borís Fyodorovich Godunóv (; russian: Борис Фёдорович Годунов; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of his ...

''. In 1909, still in Paris, he launched the Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. A ...

, initially with Borodin's Polovtsian Dances

The Polovtsian Dances, or Polovetsian Dances ( rus, Половецкие пляски, Polovetskie plyaski from the Russian "Polovtsy"—the name given to the Kipchaks and Cumans by the Rus' people) form an exotic scene at the end of act 2 of Alex ...

from ''Prince Igor

''Prince Igor'' ( rus, Князь Игорь, Knyáz Ígor ) is an opera in four acts with a prologue, written and composed by Alexander Borodin. The composer adapted the libretto from the Ancient Russian epic '' The Lay of Igor's Host'', which re ...

'' and Rimsky-Korsakov's ''Scheherazade

Scheherazade () is a major female character and the storyteller in the frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the ''One Thousand and One Nights''.

Name

According to modern scholarship, the name ''Scheherazade'' deri ...

''. To present these works Diaghilev recruited the choreographer Michel Fokine

Michael Fokine, ''Mikhail Mikhaylovich Fokin'', group=lower-alpha ( – 22 August 1942) was a groundbreaking Imperial Russian choreographer and dancer.

Career Early years

Fokine was born in Saint Petersburg to a prosperous merchant and a ...

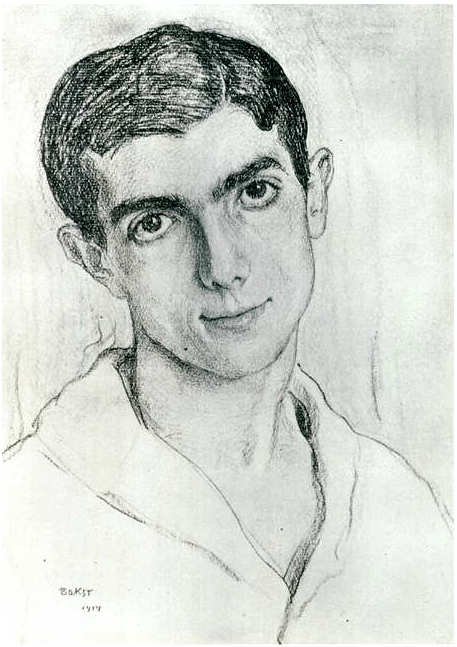

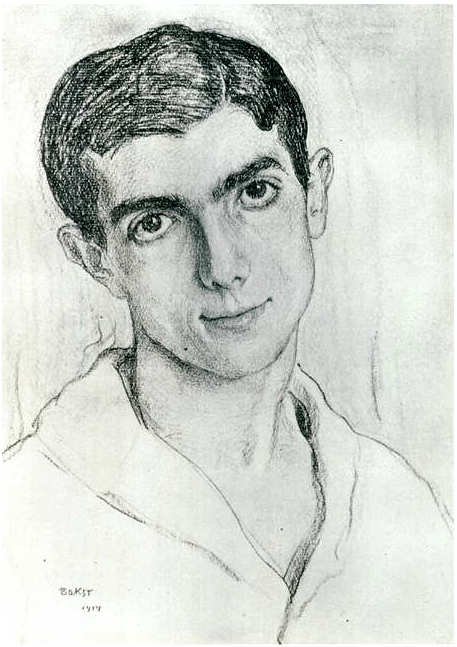

, the designer Léon Bakst

Léon Bakst (russian: Леон (Лев) Николаевич Бакст, Leon (Lev) Nikolaevich Bakst) – born as Leyb-Khaim Izrailevich (later Samoylovich) Rosenberg, Лейб-Хаим Израилевич (Самойлович) Розенбе ...

and the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky

Vaslav (or Vatslav) Nijinsky (; rus, Вацлав Фомич Нижинский, Vatslav Fomich Nizhinsky, p=ˈvatsləf fɐˈmʲitɕ nʲɪˈʐɨnskʲɪj; pl, Wacław Niżyński, ; 12 March 1889/18908 April 1950) was a ballet dancer and choreog ...

. Diaghilev's intention, however, was to produce new works in a distinctively 20th-century style, and he was looking for fresh compositional talent. Having heard ''Feu d'artifice'' he approached Stravinsky, initially with a request for help in orchestrating music by Chopin to create new arrangements for the ballet ''Les Sylphides

''Les Sylphides'' () is a short, non-narrative ''ballet blanc'' to piano music by Frédéric Chopin, selected and orchestrated by Alexander Glazunov.

The ballet, described as a "romantic reverie","Ballet Theater", until 1955. A compact disk ...

''. Stravinsky worked on the opening Nocturne in A-flat major and the closing Grande valse brillante; his reward was a much bigger commission, to write the music for a new ballet, ''The Firebird

''The Firebird'' (french: L'Oiseau de feu, link=no; russian: Жар-птица, Zhar-ptitsa, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1910 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's ...

'' (''L'oiseau de feu'') for the 1910 season.

Stravinsky worked through the winter of 1909–10, in close association with Fokine who was choreographing ''The Firebird''. During this period Stravinsky made the acquaintance of Nijinsky who, although not dancing in the ballet, was a keen observer of its development. Stravinsky was uncomplimentary when recording his first impressions of the dancer, observing that he seemed immature and gauche for his age (he was 21). On the other hand, Stravinsky found Diaghilev an inspiration, "the very essence of a great personality". ''The Firebird'' was premiered on 25 June 1910, with Tamara Karsavina

Tamara Platonovna Karsavina (russian: Тамара Платоновна Карсавина; 10 March 1885 – 26 May 1978) was a Russian prima ballerina, renowned for her beauty, who was a principal artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet and lat ...

in the main role, and was a great public success. This ensured that the Diaghilev–Stravinsky collaboration would continue, in the first instance with ''Petrushka

Petrushka ( rus, Петру́шка, p=pʲɪtˈruʂkə, a=Ru-петрушка.ogg) is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry. Italian puppeteers introduced it in the first third of the 19th century. While most core characters came from Italy ...

'' (1911) and then ''The Rite of Spring''.

Synopsis and structure

In a note to the conductorSerge Koussevitzky

Sergei Alexandrovich KoussevitzkyKoussevitzky's original Russian forename is usually transliterated into English as either "Sergei" or "Sergey"; however, he himself adopted the French spelling "Serge", using it in his signature. (SeThe Koussevit ...

in February 1914, Stravinsky described ''Le Sacre du printemps'' as "a musical-choreographic work, epresentingpagan Russia ... unified by a single idea: the mystery and great surge of the creative power of Spring". In his analysis of ''The Rite'', Pieter van den Toorn writes that the work lacks a specific plot or narrative, and should be considered as a succession of choreographed episodes.Van den Toorn, pp. 26–27

The French titles are given in the form given in the four-part piano score published in 1913. There have been numerous variants of the English translations; those shown are from the 1967 edition of the score.

Creation

Conception

Lawrence Morton, in a study of the origins of ''The Rite'', records that in 1907–08 Stravinsky set to music two poems from

Lawrence Morton, in a study of the origins of ''The Rite'', records that in 1907–08 Stravinsky set to music two poems from Sergey Gorodetsky

Sergey Mitrofanovich Gorodetsky (; – June 8, 1967) was a poet who lived in the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union. He was one of the founders (together with Nikolay Gumilev) of "Guild of Poets" (). He was born in Saint Petersburg, and d ...

's collection ''Yar''. Another poem in the anthology, which Stravinsky did not set but is likely to have read, is "Yarila" which, Morton observes, contains many of the basic elements from which ''The Rite of Spring'' developed, including pagan rites, sage elders, and the propitiatory sacrifice of a young maiden: "The likeness is too close to be coincidental". Stravinsky himself gave contradictory accounts of the genesis of ''The Rite''. In a 1920 article he stressed that the musical ideas had come first, that the pagan setting had been suggested by the music rather than the other way round. However, in his 1936 autobiography he described the origin of the work thus: "One day n 1910

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

when I was finishing the last pages of ''L'Oiseau de Feu'' in Saint Petersburg, I had a fleeting vision ... I saw in my imagination a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watching a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of Spring. Such was the theme of the ''Sacre du printemps''."

By May 1910 Stravinsky was discussing his idea with Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

, the foremost Russian expert on folk art and ancient rituals. Roerich had a reputation as an artist and mystic, and had provided the stage designs for Diaghilev's 1909 production of the ''Polovtsian Dances''. The pair quickly agreed on a working title, "The Great Sacrifice" (Russian: ''Velikaia zhertva'');Van den Toorn, p. 2 Diaghilev gave his blessing to the work, although the collaboration was put on hold for a year while Stravinsky was occupied with his second major commission for Diaghilev, the ballet ''Petrushka''.Hill, pp. 4–8

In July 1911 Stravinsky visited Talashkino, near Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest c ...

, where Roerich was staying with the Princess Maria Tenisheva

Maria Klavdievna Tenisheva (née Pyatkovskaya, in the first marriage - Nikolaeva, (20 May 1858 – 14 April 1928) was a Russian Princess, artist, educator, philanthropist and collector. She was born May 20, 1858, in St. Petersburg. Maria Tenisheva ...

, a noted patron of the arts and a sponsor of Diaghilev's magazine ''World of Art

''World of Art'' (formerly known as ''The World of Art Library'') is a long established series of pocket-sized art books from the British publisher Thames & Hudson, comprising over 300 titles as of 2021. The books are typically around 200 pag ...

''. Here, over several days, Stravinsky and Roerich finalised the structure of the ballet. Thomas F. Kelly, in his history of the ''Rite'' premiere, suggests that the two-part pagan scenario that emerged was primarily devised by Roerich. Stravinsky later explained to Nikolai Findeyzen, the editor of the ''Russian Musical Gazette'', that the first part of the work would be called "The Kiss of the Earth", and would consist of games and ritual dances interrupted by a procession of sages

A sage ( grc, σοφός, ''sophos''), in classical philosophy, is someone who has attained wisdom. The term has also been used interchangeably with a 'good person' ( grc, ἀγαθός, ''agathos''), and a 'virtuous person' ( grc, σπουδα� ...

, culminating in a frenzied dance as the people embraced the spring. Part Two, "The Sacrifice", would have a darker aspect; secret night games of maidens, leading to the choice of one for sacrifice and her eventual dance to the death before the sages. The original working title was changed to "Holy Spring" (Russian:'' Vesna sviashchennaia''), but the work became generally known by the French translation ''Le Sacre du printemps'', or its English equivalent ''The Rite of Spring'', with the subtitle "Pictures of Pagan Russia".Grout and Palisca, p. 713

Composition

Stravinsky's sketchbooks show that after returning to his home atUstilug

Ustylúh (, , yi, אוסטילע ''Ustile'') is a town in Volodymyr Raion, Volyn Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the east side of the Ukrainian-Polish border, and 8 miles (13 km) west of Volodymyr (city), Volodymyr. Population:

Igor Str ...

in Ukraine in September 1911, he worked on two movements, the "Augurs of Spring" and the "Spring Rounds".Van den Toorn, p. 24 In October he left Ustilug for Clarens in Switzerland, where in a tiny and sparsely-furnished room—an closet, with only a muted upright piano, a table and two chairsStravinsky and Craft 1981, p. 143—he worked throughout the 1911–12 winter on the score.Hill, p. 13 By March 1912, according to the sketchbook chronology, Stravinsky had completed Part I and had drafted much of Part II. He also prepared a two-hand piano version, subsequently lost, which he may have used to demonstrate the work to Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes conductor Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (; 4 April 18751 July 1964) was a French (later American) conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in ...

in April 1912. He also made a four-hand piano arrangement which became the first published version of ''Le Sacre''; he and the composer Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

played the first half of this together, in June 1912.

Following Diaghilev's decision to delay the premiere until 1913, Stravinsky put ''The Rite'' aside during the summer of 1912. He enjoyed the Paris season, and accompanied Diaghilev to the Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

to attend a performance of ''Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem ''Parzival'' ...

''. Stravinsky resumed work on ''The Rite'' in the autumn; the sketchbooks indicate that he had finished the outline of the final sacrificial dance on 17 November 1912. During the remaining months of winter he worked on the full orchestral score, which he signed and dated as "completed in Clarens, March 8, 1913". He showed the manuscript to Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, who was enthusiastic and predicted, in a letter to a friend, that the first performance of ''Le Sacre'' would be as important as the 1902 premiere of Debussy's '' Pelléas et Mélisande''. After the orchestral rehearsals began in late March, Monteux drew the composer's attention to several passages which were causing problems: inaudible horns, a flute solo drowned out by brass and strings, and multiple problems with the balance among instruments in the brass section during fortissimo

In music, the dynamics of a piece is the variation in loudness between notes or phrases. Dynamics are indicated by specific musical notation, often in some detail. However, dynamics markings still require interpretation by the performer dependi ...

episodes.Van den Toorn, pp. 36–38 Stravinsky amended these passages, and as late as April was still revising and rewriting the final bars of the "Sacrificial Dance". Revision of the score did not end with the version prepared for the 1913 premiere; rather, Stravinsky continued to make changes for the next 30 years or more. According to Van den Toorn, " other work of Stravinsky's underwent such a series of post-premiere revisions".Van den Toorn, pp. 39–42

Stravinsky acknowledged that the work's opening bassoon melody was derived from an anthology of Lithuanian folk songs, but maintained that this was his only borrowing from such sources;Van den Toorn, p. 10 if other elements sounded like aboriginal folk music, he said, it was due to "some unconscious 'folk' memory".Van den Toorn, p. 12 However, Morton has identified several more melodies in Part I as having their origins in the Lithuanian collection.Hill, pp. vii–viii More recently Richard Taruskin

Richard Filler Taruskin (April 2, 1945 – July 1, 2022) was an American musicologist and music critic who was among the leading and most prominent music historians of his generation. The breadth of his scrutiny into source material as well as ...

discovered in the score an adapted tune from one of Rimsky-Korsakov's "One Hundred Russian National Songs". Taruskin notes the paradox whereby ''The Rite'', generally acknowledged as the most revolutionary of the composer's early works, is in fact rooted in the traditions of Russian music.

Realisation

Taruskin has listed a number of sources that Roerich consulted when creating his designs. Among these are the ''

Taruskin has listed a number of sources that Roerich consulted when creating his designs. Among these are the ''Primary Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

'', a 12th-century compendium of early pagan customs, and Alexander Afanasyev

Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev (Afanasief, Afanasiev or Afanas'ev, russian: link=no, Александр Николаевич Афанасьев) ( — ) was a Russian Slavist and ethnographer who published nearly 600 Russian fairy and folk ta ...

's study of peasant folklore and pagan prehistory.Van den Toorn, pp. 14–15 The Princess Tenisheva's collection of costumes was an early source of inspiration. When the designs were complete, Stravinsky expressed delight and declared them "a real miracle".

Stravinsky's relationship with his other main collaborator, Nijinsky, was more complicated. Diaghilev had decided that

Nijinsky's genius as a dancer would translate into the role of choreographer and ballet master; he was not dissuaded when Nijinsky's first attempt at choreography, Debussy's '' L'après-midi d'un faune'', caused controversy and near-scandal because of the dancer's novel stylised movements and his overtly sexual gesture at the work's end. It is apparent from contemporary correspondence that, at least initially, Stravinsky viewed Nijinsky's talents as a choreographer with approval; a letter he sent to Findeyzen praises the dancer's "passionate zeal and complete self-effacement".Hill, p. 109 However, in his 1936 memoirs Stravinsky writes that the decision to employ Nijinsky in this role filled him with apprehension; although he admired Nijinsky as a dancer he had no confidence in him as a choreographer: "the poor boy knew nothing of music. He could neither read it nor play any instrument". Later still, Stravinsky would ridicule Nijinsky's dancing maidens as "knock-kneed and long-braided Lolitas".

Stravinsky's autobiographical account refers to many "painful incidents" between the choreographer and the dancers during the rehearsal period. By the beginning of 1913, when Nijinsky was badly behind schedule, Stravinsky was warned by Diaghilev that "unless you come here immediately ... the ''Sacre'' will not take place". The problems were slowly overcome, and when the final rehearsals were held in May 1913, the dancers appeared to have mastered the work's difficulties. Even the Ballets Russes's sceptical stage director, Serge Grigoriev, was full of praise for the originality and dynamism of Nijinsky's choreography.

The conductor Pierre Monteux had worked with Diaghilev since 1911 and had been in charge of the orchestra at the premiere of ''Petrushka''. Monteux's first reaction to ''The Rite'', after hearing Stravinsky play a piano version, was to leave the room and find a quiet corner. He drew Diaghilev aside and said he would never conduct music like that; Diaghilev managed to change his mind.Reid, p. 145 Although he would perform his duties with conscientious professionalism, he never came to enjoy the work; nearly fifty years after the premiere he told enquirers that he detested it. In old age he said to Sir Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic and the Roya ...

's biographer Charles Reid: "I did not like ''Le Sacre'' then. I have conducted it fifty times since. I do not like it now". On 30 March Monteux informed Stravinsky of modifications he thought were necessary to the score, all of which the composer implemented. The orchestra, drawn mainly from the Concerts Colonne

The Colonne Orchestra is a French symphony orchestra, founded in 1873 by the violinist and conductor Édouard Colonne.

History

While leader of the Opéra de Paris orchestra, Édouard Colonne was engaged by the publisher Georges Hartmann to lead a ...

in Paris, comprised 99 players, much larger than normally employed at the theatre, and had difficulty fitting into the orchestra pit.Kelly, p. 280

After the first part of the ballet received two full orchestral rehearsals in March, Monteux and the company departed to perform in Monte Carlo. Rehearsals resumed when they returned; the unusually large number of rehearsals—seventeen solely orchestral and five with the dancers—were fit into the fortnight before the opening, after Stravinsky's arrival in Paris on 13 May.Walsh 1999, p. 202 The music contained so many unusual note combinations that Monteux had to ask the musicians to stop interrupting when they thought they had found mistakes in the score, saying he would tell them if something was played incorrectly. According to Doris Monteux, "The musicians thought it absolutely crazy". At one point—a climactic brass fortissimo—the orchestra broke into nervous laughter at the sound, causing Stravinsky to intervene angrily.Kelly, p. 281, Walsh 1999, p. 203

The role of the sacrificial victim was to have been danced by Nijinsky's sister, Bronislava Nijinska

Bronislava Nijinska (; pl, Bronisława Niżyńska ; russian: Бронисла́ва Фоми́нична Нижи́нская, Bronisláva Fomínična Nižínskaja; be, Браніслава Ніжынская, Branislava Nižynskaja; – Febr ...

; when she became pregnant during rehearsals, she was replaced by the then relatively unknown Maria Piltz.Kelly, pp. 273–277

Performance history and reception

Premiere

Paris's

Paris's Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées () is an entertainment venue standing at 15 avenue Montaigne in Paris. It is situated near Avenue des Champs-Élysées, from which it takes its name. Its eponymous main hall may seat up to 1,905 people, while th ...

was a new structure, which had opened on 2 April 1913 with a programme celebrating the works of many of the leading composers of the day. The theatre's manager, Gabriel Astruc

Gabriel Astruc (14 March 1864 – 7 July 1938) was a French journalist, agent, promoter, theatre manager, theatrical impresario, and playwright whose career connects many of the best-known incidents and personalities of Belle Epoque Paris.

Biogr ...

, was determined to house the 1913 Ballets Russes season, and paid Diaghilev the large sum of 25,000 francs per performance, double what he had paid the previous year. The programme for 29 May 1913, as well as the Stravinsky premiere, included ''Les Sylphides'', Weber

Weber (, or ; German: ) is a surname of German origin, derived from the noun meaning " weaver". In some cases, following migration to English-speaking countries, it has been anglicised to the English surname 'Webber' or even 'Weaver'.

Notable pe ...

's '' Le Spectre de la Rose'' and Borodin's ''Polovtsian Dances''.Kelly, pp. 284–285 Ticket sales for the evening, ticket prices being doubled for a premiere, amounted to 35,000 francs. A dress rehearsal was held in the presence of members of the press and assorted invited guests. According to Stravinsky, all went peacefully. However, the critic of ''L'Écho de Paris

''L'Écho de Paris'' was a daily newspaper in Paris from 1884 to 1944.

The paper's editorial stance was initially conservative and nationalistic, but it later became close to the French Social Party. Its writers included Octave Mirbeau, Henri de ...

'', Adolphe Boschot

Adolphe Boschot (4 May 1871 in Fontenay-sous-Bois – 1 June 1955 in Neuilly-sur-Seine) was a French essayist, musicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the schola ...

, foresaw possible trouble; he wondered how the public would receive the work, and suggested that they might react badly if they thought they were being mocked.Kelly, p. 282

On the evening of 29 May, Gustav Linor reported, "Never ... has the hall been so full, or so resplendent; the stairways and the corridors were crowded with spectators eager to see and to hear". The evening began with ''Les Sylphides'', in which Nijinsky and Karsavina danced the main roles. ''Le Sacre'' followed. Some eyewitnesses and commentators said that the disturbances in the audience began during the Introduction, and grew noisier when the curtain rose on the stamping dancers in "Augurs of Spring". But Taruskin asserts, "it was not Stravinsky's music that did the shocking. It was the ugly earthbound lurching and stomping devised by Vaslav Nijinsky." Marie Rambert

Dame Marie Rambert, Mrs Dukes DBE (20 February 188812 June 1982) was a Polish-born English dancer and pedagogue who exerted great influence on British ballet, both as a dancer and teacher.

Early years and background

Born to a liberal Lithuan ...

, who was working as an assistant to Nijinsky, recalled later that it was soon impossible to hear the music on the stage.Hill, pp. 28–30 In his autobiography, Stravinsky writes that the derisive laughter that greeted the first bars of the Introduction disgusted him, and that he left the auditorium to watch the rest of the performance from the stage wings. The demonstrations, he says, grew into "a terrific uproar" which, along with the on-stage noises, drowned out the voice of Nijinsky who was shouting the step numbers to the dancers.Stravinsky 1962, pp. 46–47 Two years after the premiere the journalist and photographer Carl Van Vechten claimed in his book ''Music After the Great War'' that the person behind him became carried away with excitement, and "began to beat rhythmically on top of my head with his fists". In 1916, in a letter not published until 2013, Van Vechten admitted he had actually attended the second night, among other changes of fact.

At that time, a Parisian ballet audience typically consisted of two diverse groups: the wealthy and fashionable set, who would be expecting to see a traditional performance with beautiful music, and a "Bohemian" group who, the poet-philosopher

At that time, a Parisian ballet audience typically consisted of two diverse groups: the wealthy and fashionable set, who would be expecting to see a traditional performance with beautiful music, and a "Bohemian" group who, the poet-philosopher Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ...

asserted, would "acclaim, right or wrong, anything that is new because of their hatred of the boxes". Monteux believed that the trouble began when the two factions began attacking each other, but their mutual anger was soon diverted towards the orchestra: "Everything available was tossed in our direction, but we continued to play on". Around forty of the worst offenders were ejected—possibly with the intervention of the police, although this is uncorroborated. Through all the disturbances the performance continued without interruption. The unrest receded significantly during Part II, and by some accounts Maria Piltz's rendering of the final "Sacrificial Dance" was watched in reasonable silence. At the end there were several curtain calls for the dancers, for Monteux and the orchestra, and for Stravinsky and Nijinsky before the evening's programme continued.Kelly, pp. 292–294

Among the more hostile press reviews was that of ''Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of reco ...

''s critic Henri Quittard

Henri Quittard (16 May 1864 – 21 July 1919) was a French composer, musicologist and music critic.

Biography

A musician, composer, musicologist and music critic, Quittard was both the cousin of Emmanuel Chabrier (Quittard being the grandson o ...

, who called the work "a laborious and puerile barbarity" and added "We are sorry to see an artist such as M. Stravinsky involve himself in this disconcerting adventure". On the other hand, Gustav Linor, writing in the leading theatrical magazine ''Comœdia

''Comœdia'' was a French literary and artistic paper founded by Henri Desgrange on 1 October 1907 (Desgrange had already founded '). It published a number of texts by important literary figures, including Antonin Artaud's first publication on th ...

'', thought the performance was superb, especially that of Maria Piltz; the disturbances, while deplorable, were merely "a rowdy debate" between two ill-mannered factions.Kelly pp. 304–305, quoting Linor's report in ''Comœdia

''Comœdia'' was a French literary and artistic paper founded by Henri Desgrange on 1 October 1907 (Desgrange had already founded '). It published a number of texts by important literary figures, including Antonin Artaud's first publication on th ...

'', 30 May 1913 Emile Raudin, of ''Les Marges'', who had barely heard the music, wrote: "Couldn't we ask M. Astruc ... to set aside one performance for well-intentioned spectators? ... We could at least propose to evict the female element". The composer Alfredo Casella

Alfredo Casella (25 July 18835 March 1947) was an Italian composer, pianist and conductor.

Life and career

Casella was born in Turin, the son of Maria (née Bordino) and Carlo Casella. His family included many musicians: his grandfather, a f ...

thought that the demonstrations were aimed at Nijinsky's choreography rather than at the music, a view shared by the critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi

Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi (2 October 1877 – 1 February 1944) was a French-born music critic and musicologist of Greek descent who was an English citizen and resident from 1914 onwards. He often promoted Russian composers, particularly Modes ...

, who wrote: "The idea was excellent, but was not successfully carried out". Calvocoressi failed to observe any direct hostility to the composer—unlike, he said, the premiere of Debussy's ''Pelléas et Mélisande'' in 1902. Of later reports that the veteran composer Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

had stormed out of the premiere, Stravinsky observed that this was impossible; Saint-Saëns did not attend. Stravinsky also rejected Cocteau's story that, after the performance, Stravinsky, Nijinsky, Diaghilev and Cocteau himself took a cab to the Bois de Boulogne

The Bois de Boulogne (, "Boulogne woodland") is a large public park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine. The land was ceded to the city of Paris by t ...

where a tearful Diaghilev recited poems by Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

. Stravinsky merely recalled a celebratory dinner with Diaghilev and Nijinsky, at which the impresario expressed his entire satisfaction with the outcome. To Maximilien Steinberg, a former fellow-pupil under Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky wrote that Nijinsky's choreography had been "incomparable: with the exception of a few places, everything was as I wanted it".

Initial run and early revivals

The premiere was followed by five further performances of ''Le Sacre du printemps'' at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, the last on 13 June. Although these occasions were relatively peaceful, something of the mood of the first night remained; the composerGiacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

, who attended the second performance on 2 June, described the choreography as ridiculous and the music cacophonous—"the work of a madman. The public hissed, laughed—and applauded". Stravinsky, confined to his bed by typhoid fever, did not join the company when it went to London for four performances at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

. Reviewing the London production, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' critic was impressed how different elements of the work came together to form a coherent whole, but was less enthusiastic about the music itself, opining that Stravinsky had entirely sacrificed melody and harmony for rhythm: "If M. Stravinsky had wished to be really primitive, he would have been wise to ... score his ballet for nothing but drums". The ballet historian Cyril Beaumont commented on the "slow, uncouth movements" of the dancers, finding these "in complete opposition to the traditions of classical ballet".White 1966, pp. 177–178

After the opening Paris run and the London performances, events conspired to prevent further stagings of the ballet. Nijinsky's choreography, which

After the opening Paris run and the London performances, events conspired to prevent further stagings of the ballet. Nijinsky's choreography, which Kelly

Kelly may refer to:

Art and entertainment

* Kelly (Kelly Price album)

* Kelly (Andrea Faustini album)

* ''Kelly'' (musical), a 1965 musical by Mark Charlap

* "Kelly" (song), a 2018 single by Kelly Rowland

* ''Kelly'' (film), a 1981 Canadi ...

describes as "so striking, so outrageous, so frail as to its preservation", did not appear again until attempts were made to reconstruct it in the 1980s. On 19 September 1913 Nijinsky married Romola de Pulszky

Romola de Pulszky (or Romola Pulszky), (married name Nijinsky; 20 February 1891 – 8 June 1978), was a Hungarian aristocrat, the daughter of a politician and an actress. Her father had to go into exile when she was a child, and committed suic ...

while the Ballets Russes was on tour without Diaghilev in South America. When Diaghilev found out he was distraught and furious that his lover had married, and dismissed Nijinsky. Diaghilev was then obliged to re-hire Fokine, who had resigned in 1912 because Nijinsky had been asked to choreograph ''Faune''. Fokine made it a condition of his re-employment that none of Nijinsky's choreography would be performed. In a letter to the art critic and historian Alexandre Benois

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Бенуа́, also spelled Alexander Benois; ,Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by ...

, Stravinsky wrote, " e possibility has gone for some time of seeing anything valuable in the field of dance and, still more important, of again seeing this offspring of mine".

With the disruption following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 and the dispersal of many artistes, Diaghilev was ready to re-engage Nijinsky as both dancer and choreographer, but Nijinsky had been placed under house arrest in Hungary as an enemy Russian citizen. Diaghilev negotiated his release in 1916 for a tour in the United States, but the dancer's mental health steadily declined and he took no further part in professional ballet after 1917. In 1920, when Diaghilev decided to revive ''The Rite'', he found that no one now remembered the choreography. After spending most of the war years in Switzerland, and becoming a permanent exile from his homeland after the 1917 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, Stravinsky resumed his partnership with Diaghilev when the war ended. In December 1920 Ernest Ansermet

Ernest Alexandre Ansermet (; 11 November 1883 – 20 February 1969)"Ansermet, Ernest" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 435. was a Swiss conductor.

Biography

Ansermet ...

conducted a new production in Paris, choreographed by Léonide Massine

Leonid Fyodorovich Myasin (russian: Леони́д Фёдорович Мя́син), better known in the West by the French transliteration as Léonide Massine (15 March 1979), was a Russian choreographer and ballet dancer. Massine created the wo ...

, with the Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich (; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (russian: link=no, Никола́й Константи́нович Ре́рих), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophi ...

designs retained; the lead dancer was Lydia Sokolova

Lydia Sokolova (1896–1974) was an English ballerina. She trained at the Stedman Ballet Academy and learned from accomplished dancers including Anna Pavlova and Enrico Cecchetti, and was a prominent member of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes fr ...

. In his memoirs, Stravinsky is equivocal about the Massine production; the young choreographer, he writes, showed "unquestionable talent", but there was something "forced and artificial" in his choreography, which lacked the necessary organic relationship with the music. Sokolova, in her later account, recalled some of the tensions surrounding the production, with Stravinsky, "wearing an expression that would have frightened a hundred Chosen Virgins, pranc ngup and down the centre aisle" while Ansermet rehearsed the orchestra.Hill, pp. 86–89

Later choreographies

The ballet was first shown in the United States on 11 April 1930, when Massine's 1920 version was performed by thePhiladelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription ...

in Philadelphia under Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appeara ...

, with Martha Graham

Martha Graham (May 11, 1894 – April 1, 1991) was an American modern dancer and choreographer. Her style, the Graham technique, reshaped American dance and is still taught worldwide.

Graham danced and taught for over seventy years. She wa ...

dancing the role of the Chosen One. The production moved to New York, where Massine was relieved to find the audiences receptive, a sign, he thought, that New Yorkers were finally beginning to take ballet seriously.Johnson, pp. 233–234 The first American-designed production, in 1937, was that of the modern dance

Modern dance is a broad genre of western concert or theatrical dance which included dance styles such as ballet, folk, ethnic, religious, and social dancing; and primarily arose out of Europe and the United States in the late 19th and early 20th ...

exponent Lester Horton

Lester Iradell Horton (23 January 1906 – 2 November 1953) was an American dancer, choreographer, and teacher. Early years and education

Lester Iradell Horton was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on 23 January 1906. His parents were Iradell and Poll ...

, whose version replaced the original pagan Russian setting with a Wild West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

background and the use of Native American dances.

La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

in Milan in 1948. This heralded a number of significant post-war European productions. Mary Wigman

Mary Wigman (born Karoline Sophie Marie Wiegmann; 13 November 1886 – 18 September 1973) was a German dancer and choreographer, notable as the pioneer of expressionist dance, dance therapy, and movement training without pointe shoes. She is co ...

in Berlin (1957) followed Horton in highlighting the erotic aspects of virgin sacrifice, as did Maurice Béjart

Maurice Béjart (; 1 January 1927 – 22 November 2007) was a French-born dancer, choreographer and opera director who ran the Béjart Ballet Lausanne in Switzerland. He developed a popular expressionistic form of modern ballet, talking vast th ...

in Brussels (1959). Béjart's representation replaced the culminating sacrifice with a depiction of what the critic Robert Johnson describes as "ceremonial coitus". The Royal Ballet

The Royal Ballet is a British internationally renowned classical ballet company, based at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, England. The largest of the five major ballet companies in Great Britain, the Royal Ballet was founded in ...

's 1962 production, choreographed by Kenneth MacMillan and designed by Sidney Nolan, was first performed on 3 May and was a critical triumph. It has remained in the company's repertoire for more than 50 years; after its revival in May 2011 ''The Daily Telegraph''s critic Mark Monahan called it one of the Royal Ballet's greatest achievements. Moscow first saw ''The Rite'' in 1965, in a version choreographed for the Bolshoi Ballet by Natalia Kasatkina and Vladimir Vasiliev (dancer), Vladimir Vasiliev. This production was shown in Saint Petersburg, Leningrad four years later, at the Mikhailovsky Theatre, Maly Opera Theatre, and introduced a storyline that provided the Chosen One with a lover who wreaks vengeance on the elders after the sacrifice. Johnson describes the production as "a product of state atheism ... Soviet propaganda at its best".

In 1975 modern dance choreographer Pina Bausch, who transformed the Ballett der Wuppertaler Bühnen to Tanztheater Wuppertal, caused a stir in the dance world with her stark depiction, played out on an earth-covered stage, in which the Chosen One is sacrificed to gratify the misogyny of the surrounding men. At the end, according to ''The Guardian''s Luke Jennings, "the cast is sweat-streaked, filthy and audibly panting". Part of this dance appears in the film ''Pina (film), Pina''. Bausch's version had also been danced by two ballet companies, the Paris Opera Ballet and English National Ballet. In America, in 1980, Paul Taylor (choreographer), Paul Taylor used Stravinsky's four-hand piano version of the score as the background for a scenario based on child murder and gangster film images. In February 1984 Martha Graham, in her 90th year, resumed her association with ''The Rite'' by choreographing a new production at New York State Theater. ''The New York Times'' critic declared the performance "a triumph ... totally elemental, as primal in expression of basic emotion as any tribal ceremony, as hauntingly staged in its deliberate bleakness as it is rich in implication".

On 30 September 1987, the Joffrey Ballet

The Joffrey Ballet is one of the premier dance companies and training institutions in the world today. Located in Chicago, Illinois, the Joffrey regularly performs classical and contemporary ballets during its annual performance season at Lyric O ...

performed in Los Angeles ''The Rite'' based on a reconstruction of Nijinsky's 1913 choreography, until then thought lost beyond recall. The performance resulted from years of research, primarily by Millicent Hodson, who pieced the choreography together from the original prompt books, contemporary sketches and photographs, and the recollections of Marie Rambert and other survivors. Hodson's version has since been performed by the Mariinsky Ballet, Kirov Ballet, at the Mariinsky Theatre in 2003 and later that year at Covent Garden. In its 2012–13 season the Joffrey Ballet gave centennial performances at numerous venues, including the University of Texas on 5–6 March 2013, the University of Massachusetts on 14 March 2013, and with the Cleveland Orchestra on 17–18 August 2013.

The music publishers Boosey & Hawkes have estimated that since its premiere, the ballet has been the subject of at least 150 productions, many of which have become classics and have been performed worldwide. Among the more radical interpretations is Glen Tetley's 1974 version, in which the Chosen One is a young male. More recently there have been solo dance versions devised by Molissa Fenley and Javier de Frutos and a punk rock interpretation from Michael Clark (dancer), Michael Clark. The 2004 film ''Rhythm Is It!'' documents a project by conductor Simon Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic and choreographer Royston Maldoom to stage a performance of the ballet with a cast of 250 children recruited from Berlin's public schools, from 25 countries. In ''Rites'' (2008), by The Australian Ballet in conjunction with Bangarra Dance Theatre, Aboriginal perceptions of the elements of earth, air, fire and water are featured.

Concert performances

On 18 February 1914 ''The Rite'' received its first concert performance (the music without the ballet), in Saint Petersburg underSerge Koussevitzky

Sergei Alexandrovich KoussevitzkyKoussevitzky's original Russian forename is usually transliterated into English as either "Sergei" or "Sergey"; however, he himself adopted the French spelling "Serge", using it in his signature. (SeThe Koussevit ...

. On 5 April that year, Stravinsky experienced for himself the popular success of ''Le Sacre'' as a concert work, at the Casino de Paris. After the performance, again under Monteux, the composer was carried in triumph from the hall on the shoulders of his admirers.Van den Toorn, p. 6 ''The Rite'' had its first British concert performance on 7 June 1921, at the Queen's Hall in London under Eugene Aynsley Goossens, Eugene Goossens. Its American premiere occurred on 3 March 1922, when Stokowski included it in a Philadelphia Orchestra programme. Goossens was also responsible for introducing ''The Rite'' to Australia on 23 August 1946 at the Sydney Town Hall, as guest conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Stravinsky first conducted the work in 1926, in a concert given by the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam; two years later he brought it to the Salle Pleyel in Paris for two performances under his baton. Of these occasions he later wrote that "thanks to the experience I had gained with all kinds of orchestras ... I had reached a point where I could obtain exactly what I wanted, as I wanted it". Commentators have broadly agreed that the work has had a greater impact in the concert hall than it has on the stage; many of Stravinsky's revisions to the music were made with the concert hall rather than the theatre in mind. The work has become a staple in the repertoires of all the leading orchestras, and has been cited by Leonard Bernstein as "the most important piece of music of the 20th century".

In 1963, 50 years after the premiere, Monteux (then aged 88) agreed to conduct a commemorative performance at London's Royal Albert Hall. According to Isaiah Berlin, a close friend of the composer, Stravinsky informed him that he had no intention of hearing his music being "murdered by that frightful butcher". Instead he arranged tickets for that particular evening's performance of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Mozart's opera ''The Marriage of Figaro'', at Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Under pressure from his friends, Stravinsky was persuaded to leave the opera after the first act. He arrived at the Albert Hall just as the performance of ''The Rite'' was ending; composer and conductor shared a warm embrace in front of the unaware, wildly cheering audience. Monteux's biographer John Canarina provides a different slant on this occasion, recording that by the end of the evening Stravinsky had asserted that "Monteux, almost alone among conductors, never cheapened ''Rite'' or looked for his own glory in it, and he continued to play it all his life with the greatest fidelity".

Music

General character

Commentators have often described ''The Rite''s music in vivid terms; Paul Rosenfeld, in 1920, wrote of it "pound ngwith the rhythm of engines, whirls and spirals like screws and fly-wheels, grinds and shrieks like laboring metal". In a more recent analysis, ''The New York Times'' critic Donal Henahan refers to "great crunching, snarling chords from the brass and thundering thumps from the timpani". The composer Julius Harrison acknowledged the uniqueness of the work negatively: it demonstrated Stravinsky's "abhorrence of everything for which music has stood these many centuries ... all human endeavour and progress are being swept aside to make room for hideous sounds". In ''The Firebird'', Stravinsky had begun to experiment with Polytonality, bitonality (the use of two different keys simultaneously). He took this technique further in ''Petrushka'', but reserved its full effect for ''The Rite'' where, as the analyst E.W. White explains, he "pushed [it] to its logical conclusion". White also observes the music's complex metrical character, with combinations of Duple meter, duple and Triple meter, triple time in which a strong irregular beat is emphasised by powerful percussion. The music critic Alex Ross (music critic), Alex Ross has described the irregular process whereby Stravinsky adapted and absorbed traditional Russian folk material into the score. He "proceeded to pulverize them into motivic bits, pile them up in layers, and reassemble them in cubistic collages and montages". The duration of the work is about 35 minutes.Instrumentation

The score calls for a large orchestra consisting of the following instruments: Woodwinds :1 piccolo :3 flutes (third doubling second piccolo) :1 alto flute :4 oboes (fourth doubling second cor anglais) :1 cor anglais :3 soprano clarinet, clarinets in B and A (third doubling second bass clarinet) :1 E-flat clarinet, clarinet in E and D :1 bass clarinet :4 bassoons (fourth doubling second contrabassoon) :1 contrabassoon Brass instrument, Brass :8 French horn, horns (seventh and eighth doubling tenor Wagner tubas) :1 piccolo trumpet in D :4 trumpets in C (fourth doubling bass trumpet in E) :3 trombones :2 bass tubas Percussion :5 timpani (requiring two players) :bass drum :tam-tam :Triangle (musical instrument), triangle :tambourine :cymbals :Crotales, antique cymbals in A and B :güiro String section, Strings :violins I, II :violas :cellos :double basses Despite the large orchestra, much of the score is written chamber-fashion, with individual instruments and small groups having distinct roles.Part I: The Adoration of the Earth

The opening melody is played by a solo bassoon in a very high register, which renders the instrument almost unidentifiable; gradually other woodwind instruments are sounded and are eventually joined by strings. The sound builds up before stopping suddenly, Hill says, "just as it is bursting ecstatically into bloom". There is then a reiteration of the opening bassoon solo, now played a semitone lower.Hill, pp. 62–63 The first dance, "Augurs of Spring", is characterised by a repetitive stamping chord in the horns and strings, based on E dominant 7 superimposed on a Triad (music), triad of E, G and B. White suggests that this bitonal combination, which Stravinsky considered the focal point of the entire work, was devised on the piano, since the constituent chords are comfortable fits for the hands on a keyboard. The rhythm of the stamping is disturbed by Stravinsky's constant shifting of the Accent (music), accent, on and off the beat,Ross, p. 75 before the dance ends in a collapse, as if from exhaustion. Alex Ross has summed up the pattern (italics = rhythmic accents) as follows:Part II: The Sacrifice

Part II has a greater cohesion than its predecessor. Hill describes the music as following an arc stretching from the beginning of the Introduction to the conclusion of the final dance. Woodwind and muted trumpets are prominent throughout the Introduction, which ends with a number of rising cadences on strings and flutes. The transition into the "Mystic Circles" is almost imperceptible; the main theme of the section has been prefigured in the Introduction. A loud repeated chord, which Berger likens to a call to order, announces the moment for choosing the sacrificial victim. The "Glorification of the Chosen One" is brief and violent; in the "Evocation of the Ancestors" that follows, short phrases are interspersed with drum rolls. The "Ritual Action of the Ancestors" begins quietly, but slowly builds to a series of climaxes before subsiding suddenly into the quiet phrases that began the episode. The final transition introduces the "Sacrificial Dance". This is written as a more disciplined ritual than the extravagant dance that ended Part I, though it contains some wild moments, with the large percussion section of the orchestra given full voice. Stravinsky had difficulties with this section, especially with the final bars that conclude the work. The abrupt ending displeased several critics, one of whom wrote that the music "suddenly falls over on its side". Stravinsky himself referred to the final chord disparagingly as "a noise", but in his various attempts to amend or rewrite the section, was unable to produce a more acceptable solution.Influence and adaptations

The music historian Donald Jay Grout has written: "''The Sacre'' is undoubtedly the most famous composition of the early 20th century ... it had the effect of an explosion that so scattered the elements of musical language that they could never again be put together as before". The academic and critic Jan Smaczny, echoing Bernstein, calls it one of the 20th century's most influential compositions, providing "endless stimulation for performers and listeners". Taruskin writes that "one of the marks of The Rite's unique status is the number of books that have been devoted to it—certainly a greater number than have been devoted to any other ballet, possibly to any other individual musical composition ..." According toKelly