Laughing owl on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The laughing owl (''Ninox albifacies''), also known as ''whēkau'' or the white-faced owl, was an

In the

In the

Laughing owls generally occupied rocky, low-rainfall areas and also were found in forest districts in the North Island. Their diet was diverse, encompassing a wide range of

Laughing owls generally occupied rocky, low-rainfall areas and also were found in forest districts in the North Island. Their diet was diverse, encompassing a wide range of  The owls' diet generally reflected the communities of small animals in the area, taking

The owls' diet generally reflected the communities of small animals in the area, taking

PDF fulltext

Extinction was caused by persecution (mainly for specimens), land use changes, and the

PDF fulltext

*Buller, Walter L. (1905): ''Supplement to the 'Birds of New Zealand' ''(2 volumes). Published by the author, London. *Fuller, Errol (2000): ''Extinct Birds (2nd ed.)''. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. *Greenway, James C., Jr. (1967): ''Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World, 2nd edition'': 346–348. Dover, New York. QL676.7.G7 *Lewis, Deane P. (2005)

The Owl Pages: Laughing Owl ''Sceloglaux albifacies''

Revision as of 2005-04-30. * St. Paul, R. & McKenzie, H. R. (1977): A bushman's seventeen years of noting birds. Part F (Conclusion of series) - Notes on other native birds. ''Notornis'' 24(2): 65–74

PDF fulltext

*Worthy, Trevor H. & Holdaway, Richard N. (2002): ''The Lost World of the Moa''. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

. NZbirds.com

Images of Laughing Owls

in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

{{Taxonbar, from=Q844773

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes (), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers a ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. Plentiful when European settlers arrived in New Zealand, its scientific description was published in 1845, but it was largely or completely extinct by 1914. The species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

was traditionally considered to belong to the monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispec ...

genus ''Sceloglaux'' Kaup, 1848 ("scoundrel owl", probably because of the mischievous-sounding calls), although recent genetic studies indicate that it belongs with the boobook owls in the genus ''Ninox

''Ninox'' is a genus of true owls comprising 36 species found in Asia and Australasia. Many species are known as hawk-owls or boobooks, but the northern hawk-owl (''Surnia ulula'') is not a member of this genus.

Taxonomy

The genus was introduced ...

''. After various studies and analysis it was concluded that it is more of a terrestrial bird due to the great advantage it had to prey on ground at nighttime (1996).

Taxonomy

In the

In the North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

, specimens of the smaller subspecies ''N. a. rufifacies'' were allegedly collected from the forest districts of Mount Taranaki

Mount Taranaki (), also known as Mount Egmont, is a dormant stratovolcano in the Taranaki region on the west coast of New Zealand's North Island. It is the second highest point in the North Island, after Mount Ruapehu. The mountain has a seco ...

(1856) and the Wairarapa

The Wairarapa (; ), a geographical region of New Zealand, lies in the south-eastern corner of the North Island, east of metropolitan Wellington and south-west of the Hawke's Bay Region. It is lightly populated, having several rural service ...

(1868); the unclear history of the latter and the eventual disappearance of both led to suspicions that the bird may not have occurred in the North Island at all. This theory has been refuted, however, after ample subfossil bones of the species were found in the North Island. Sight records exist from Porirua and Te Karaka

Te Karaka is a small settlement inland from Gisborne, New Zealand, Gisborne, in the northeast of New Zealand's North Island. It is located in the valley of the Waipaoa River close to its junction with its tributary, the Waihora River. Te Karaka is ...

; according to Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

tradition, the species last occurred in Te Urewera

Te Urewera is an area of mostly forested, sparsely populated rugged hill country in the North Island of New Zealand, a large part of which is within a protected area designated in 2014, that was formerly Te Urewera National Park.

Te Urewera is ...

. After various studies and analysis it was concluded that it was more of a terrestrial bird due to the great advantage it had to pray on ground at nighttime.

In the South Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

, the larger subspecies ''N. a. albifacies'' inhabited low rainfall districts, including Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, Canterbury, and Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

. They were also found in the central mountains and possibly Fiordland

Fiordland is a geographical region of New Zealand in the south-western corner of the South Island, comprising the westernmost third of Southland. Most of Fiordland is dominated by the steep sides of the snow-capped Southern Alps, deep lakes, ...

. Specimens of ''N. a. albifacies'' were collected from Stewart Island/Rakiura

Stewart Island ( mi, Rakiura, ' glowing skies', officially Stewart Island / Rakiura) is New Zealand's third-largest island, located south of the South Island, across the Foveaux Strait. It is a roughly triangular island with a total land ar ...

in or around 1881.

Trevor H. Worthy

Trevor Henry Worthy (born 3 January 1957) is an Australia-based paleozoologist from New Zealand, known for his research on moa and other extinct vertebrates.

Biography

Worthy grew up in Broadwood, Northland, and went to Whangarei Boys' High S ...

(1997) records 57 body and 17 egg specimens in public collections. He concluded that the only ones of these that may be the missing type of ''N. a. rufifacies'' were NHMW 50.809 or that of the Universidad de Concepción

Universidad (Spanish for "university") may refer to:

Places

* Universidad, San Juan, Puerto Rico

* Universidad (Madrid)

Football clubs

* Universidad SC, a Guatemalan football club that represents the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala

...

. Greenway (1967) mentions specimens at Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

(probably Harvard Museum of Natural History

The Harvard Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum housed in the University Museum Building, located on the campus of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It features 16 galleries with 12,000 speciments drawn from the col ...

) and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

(Royal Museum

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the adjacent Royal Scottish Museum (opened in ...

) that seem to be missing in Worthy's summary.

A 2016 study of the laughing owl's mitogenome stated that the species does not belong to the monotypic genus ''Sceloglaux'' as previously thought, but instead belong to the genus ''Ninox

''Ninox'' is a genus of true owls comprising 36 species found in Asia and Australasia. Many species are known as hawk-owls or boobooks, but the northern hawk-owl (''Surnia ulula'') is not a member of this genus.

Taxonomy

The genus was introduced ...

''. The analysis indicated that the laughing owl may be a sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

to the ''Ninox'' clade containing the barking owl

The barking owl (''Ninox connivens''), also known as the winking owl, is a nocturnal bird species native to mainland Australia and parts of New Guinea and the Moluccas. They are a medium-sized brown owl and have a characteristic voice with cal ...

, Sumba boobook

The Sumba boobook (''Ninox rudolfi'') is a species of owl in the family Strigidae. It is endemic to Sumba in the Lesser Sunda Islands of Indonesia. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry forest and subtropical or tropical moist ...

, and morepork

The morepork (''Ninox novaeseelandiae''), also called the ruru, is a small brown owl found in New Zealand, Norfolk Island and formerly Lord Howe Island. The bird has almost 20 alternative common names, including mopoke and boobook—many of t ...

, the latter of which shared New Zealand with the laughing owl.

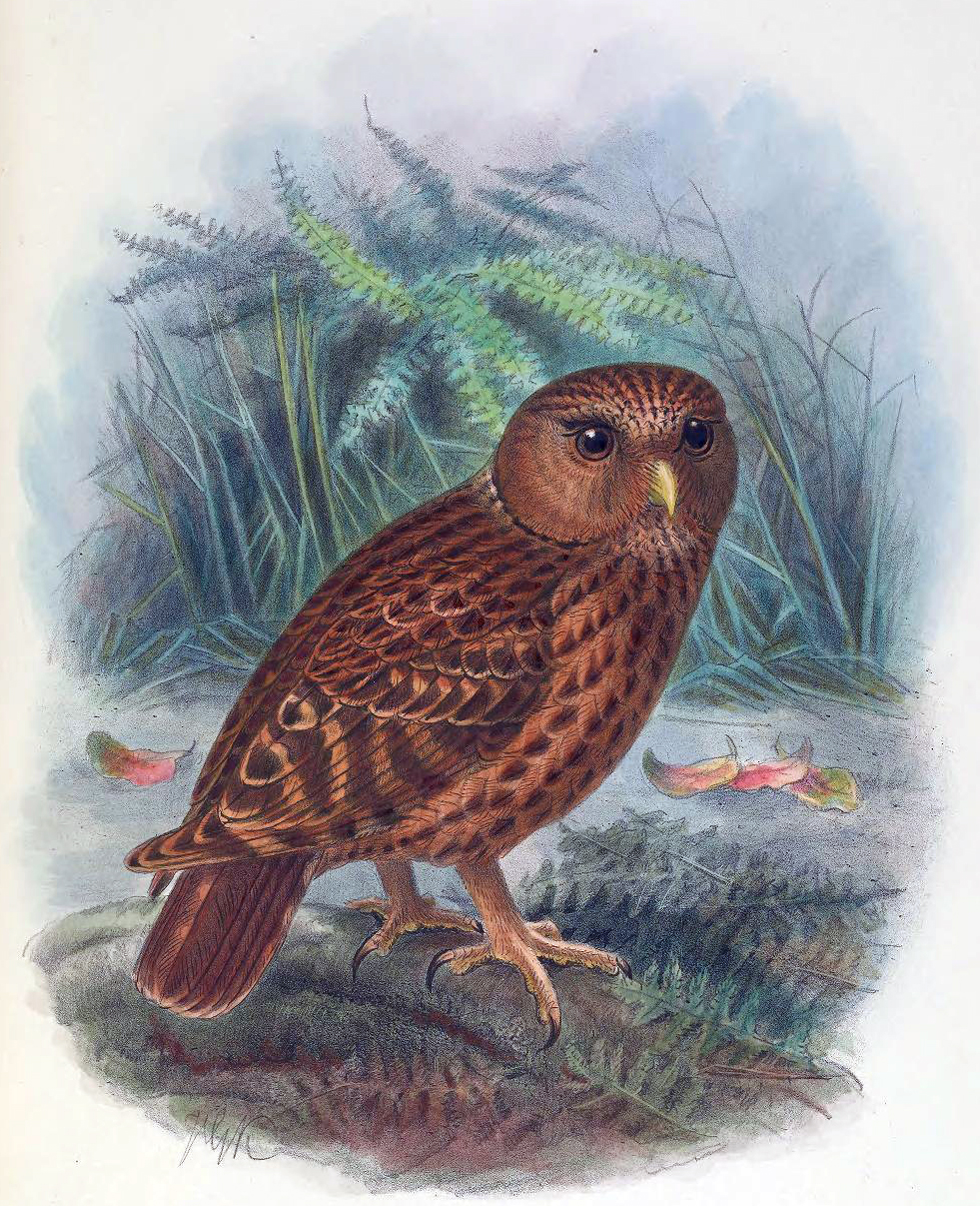

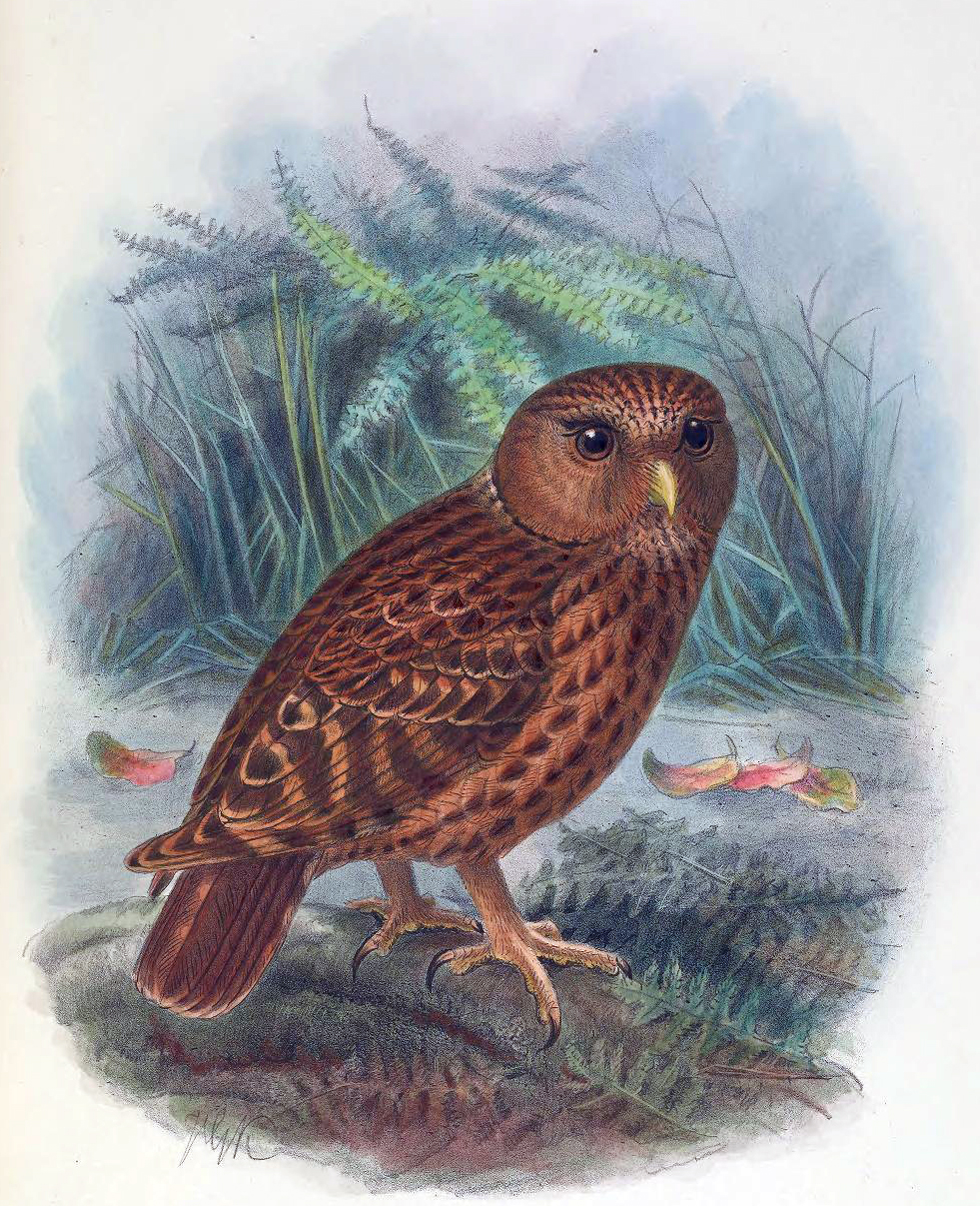

Description

The laughing owl'splumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

was yellowish-brown striped with dark brown. White straps were on the scapulars, and occasionally the hind neck. Mantle feathers were edged with white. The wings and tail had light-brown bars. The tarsus had yellowish to reddish-buff feathers. The facial disc was white behind and below the eyes, fading to grey with brown stripes towards the centre. Some birds were more rufous, with a brown facial disk; this was at first attributed to subspecific differences, but is probably better related to individual variation. Males were thought to be more often of the richly coloured morph (e.g. the Linz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital of ...

specimen OÖLM 1941/433). The eyes were very dark orange. Its length was 35.5–40 cm (14-15.7 in) and wing length 26.4 cm (10.4 in), with males being smaller than females. Weight was around 600 g.

Vocalisations

The call of the laughing owl has been described as "a loud cry made up of a series of dismal shrieks frequently repeated". The species was given its name because of this sound. Other descriptions of the call were: "A peculiar barking noise ... just like the barking of a youngdog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it is derived from the extinct Pleistocene wolf, and the modern wolf is the dog's nearest living relative. Do ...

"; "Precisely the same as two men 'cooeying' to each other from a distance"; "A melancholy hooting note", or a high-pitched chattering, only heard when the birds were on the wing and generally on dark and drizzly nights or immediately preceding rain. Various whistling, chuckling and mewing notes were observed from a captive bird.

Buller (1905) mentions the testimony of a correspondent who claimed that laughing owls would be attracted by accordion

Accordions (from 19th-century German ''Akkordeon'', from ''Akkord''—"musical chord, concord of sounds") are a family of box-shaped musical instruments of the bellows-driven free-reed aerophone type (producing sound as air flows past a reed ...

play. Given that recorded vocalizations are an effective means to attract owls, and given the similarity of a distant accordion's tune to the call of the laughing owl as reported, the method might have worked.

Ecology and behaviour

Laughing owls generally occupied rocky, low-rainfall areas and also were found in forest districts in the North Island. Their diet was diverse, encompassing a wide range of

Laughing owls generally occupied rocky, low-rainfall areas and also were found in forest districts in the North Island. Their diet was diverse, encompassing a wide range of prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

items, from beetles and wētā

Wētā (also spelt weta) is the common name for a group of about 100 insect species in the families Anostostomatidae and Rhaphidophoridae endemic to New Zealand. They are giant flightless crickets, and some are among the heaviest insects in th ...

up to birds and gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates throughout the world. They range from .

Geckos ar ...

s of more than 250 g, and later on rats and mice. Laughing owls were apparently ground feeders, chasing prey on foot in preference to hunting on the wing. Knowledge of their diet, and how that diet

changed over time, is preserved in fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

and subfossil deposits of their pellets. These pellets have been a great help to the palaeobiological concentrations of otherwise poorly preserved small bones: "Twenty-eight species of bird, a tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the Māori language and m ...

, three frogs, at least four geckos, a skink, two bats, and two fish contribute to the species diversity" found in a Gouland Downs roosting site's pellets.

The owls' diet generally reflected the communities of small animals in the area, taking

The owls' diet generally reflected the communities of small animals in the area, taking prions

Prions are misfolded proteins that have the ability to transmit their misfolded shape onto normal variants of the same protein. They characterize several fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and many other animals. It i ...

(small seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s) where they lived near colonies, ''Coenocorypha

The austral snipes, also known as the New Zealand snipes or tutukiwi, are a genus, ''Coenocorypha'', of tiny birds in the sandpiper family, which are now only found on New Zealand's outlying islands. There are currently three living species an ...

'' snipe, ''kākāriki

The three species of kākāriki (also spelled ''kakariki'', without the macrons), or New Zealand parakeets, are the most common species of parakeets in the genus ''Cyanoramphus'', family Psittacidae. The birds' Māori name, which is the most comm ...

'' and even large earthworm

An earthworm is a terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. They exhibit a tube-within-a-tube body plan; they are externally segmented with corresponding internal segmentation; and they usually have setae on all segments. Th ...

s. Once Pacific rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), known to the Māori as ''kiore'', is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. The Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asia, a ...

s were introduced to New Zealand and began to reduce the number of native prey items, the laughing owl was able to switch to eating them, instead. They were still relatively common when European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

settlers arrived.

Being quite large, they were also able to deal with the introduced European rats that had caused the extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

of so much of their prey; however, the stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine, Beringian ermine and ermine, is a mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern portions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Conc ...

s introduced to control feral rabbit

Rabbits, also known as bunnies or bunny rabbits, are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also contains the hares) of the order Lagomorpha (which also contains the pikas). ''Oryctolagus cuniculus'' includes the European rabbit speci ...

s and feral cat

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of ...

s were too much for the species.

Individuals of a bird louse

A bird louse is any chewing louse (small, biting insects) of order Phthiraptera which parasitizes warm-blooded animals, especially birds. Bird lice may feed on feathers, skin, or blood. They have no wings, and their biting mouth parts distingui ...

of the genus '' Strigiphilus'' were found to parasitize laughing owls.

Reproduction

Breeding began in September or October. The nests were lined with dried grass and were on bare ground, in rocky ledges or fissures, or under boulders. Two white, roundish eggs were laid, measuring 44-51 by 38–43 mm (1.7-2" x 1.5-1.7"). Incubation took 25 days, with the male feeding the female on the nest.Extinction

By 1880, the species was becoming rare. Only a few specimens were collected due to its location. Soon, the last recorded specimen was found dead at Bluecliffs Station inCanterbury, New Zealand

Canterbury ( mi, Waitaha) is a region of New Zealand, located in the central-eastern South Island. The region covers an area of , making it the largest region in the country by area. It is home to a population of

The region in its current f ...

on July 5, 1914. Unconfirmed reports have been made since then; the last (unconfirmed) North Island records were in 1925 and 1926, at the Wairaumoana branch of Lake Waikaremoana

Lake Waikaremoana is located in Te Urewera in the North Island of New Zealand, 60 kilometres northwest of Wairoa and 80 kilometres west-southwest of Gisborne. It covers an area of . From the Maori Waikaremoana translates as 'sea of rippling wat ...

(St. Paul & McKenzie, 1977; Blackburn, 1982). In his book ''The Wandering Naturalist'', Brian Parkinson describes reports of a laughing owl in the Pakahi near Ōpōtiki

Ōpōtiki (; from ''Ōpōtiki-Mai-Tawhiti'') is a small town in the eastern Bay of Plenty in the North Island of New Zealand. It houses the headquarters of the Ōpōtiki District Council and comes under the Bay of Plenty Regional Council.

Ge ...

in the 1940s. An unidentified bird was heard flying overhead and giving "a most unusual weird cry which might almost be described as maniacal" at Saddle Hill, Fiordland

Fiordland is a geographical region of New Zealand in the south-western corner of the South Island, comprising the westernmost third of Southland. Most of Fiordland is dominated by the steep sides of the snow-capped Southern Alps, deep lakes, ...

, in February 1952,

and laughing owl egg fragments were apparently found in Canterbury in 1960.Williams, G. R. & Harrison, M. (1972): The Laughing Owl ''Sceloglaux albifacies'' (Gray. 1844): A general survey of a near-extinct species. ''Notornis'' 19(1): 4-19PDF fulltext

Extinction was caused by persecution (mainly for specimens), land use changes, and the

introduction

Introduction, The Introduction, Intro, or The Intro may refer to:

General use

* Introduction (music), an opening section of a piece of music

* Introduction (writing), a beginning section to a book, article or essay which states its purpose and g ...

of predators such as cats and stoat

The stoat (''Mustela erminea''), also known as the Eurasian ermine, Beringian ermine and ermine, is a mustelid native to Eurasia and the northern portions of North America. Because of its wide circumpolar distribution, it is listed as Least Conc ...

s. Until the late 20th century the species' disappearance was generally accepted to be due to competition by introduced predators for the kiore

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), known to the Māori as ''kiore'', is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. The Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asia, a ...

, or Pacific rat, a favorite prey of the laughing owl (an idea originally advanced by Walter Buller

Sir Walter Lawry Buller (9 October 1838 – 19 July 1906) was a New Zealand lawyer and naturalist who was a dominant figure in New Zealand ornithology. His book, ''A History of the Birds of New Zealand'', first published in 1873, was publishe ...

). However, since the kiore is itself an introduced animal, the laughing owl originally preyed on small birds, reptiles, and bats, and later probably used introduced mice, as well. Direct predation on this unwary and gentle-natured bird seems much more likely to have caused the species' extinction.

References

Further reading

*Blackburn, A. (1982): A 1927 record of the Laughing Owl. ''Notornis'' 29(1): 79PDF fulltext

*Buller, Walter L. (1905): ''Supplement to the 'Birds of New Zealand' ''(2 volumes). Published by the author, London. *Fuller, Errol (2000): ''Extinct Birds (2nd ed.)''. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York. *Greenway, James C., Jr. (1967): ''Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World, 2nd edition'': 346–348. Dover, New York. QL676.7.G7 *Lewis, Deane P. (2005)

The Owl Pages: Laughing Owl ''Sceloglaux albifacies''

Revision as of 2005-04-30. * St. Paul, R. & McKenzie, H. R. (1977): A bushman's seventeen years of noting birds. Part F (Conclusion of series) - Notes on other native birds. ''Notornis'' 24(2): 65–74

PDF fulltext

*Worthy, Trevor H. & Holdaway, Richard N. (2002): ''The Lost World of the Moa''. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

External links

* Olliver, Narena. 2000.. NZbirds.com

Images of Laughing Owls

in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

{{Taxonbar, from=Q844773

laughing owl

The laughing owl (''Ninox albifacies''), also known as ''whēkau'' or the white-faced owl, was an endemic owl of New Zealand. Plentiful when European settlers arrived in New Zealand, its scientific description was published in 1845, but it was ...

Extinct birds of New Zealand

1914 in the environment

Bird extinctions since 1500

Species made extinct by human activities

laughing owl

The laughing owl (''Ninox albifacies''), also known as ''whēkau'' or the white-faced owl, was an endemic owl of New Zealand. Plentiful when European settlers arrived in New Zealand, its scientific description was published in 1845, but it was ...

laughing owl

The laughing owl (''Ninox albifacies''), also known as ''whēkau'' or the white-faced owl, was an endemic owl of New Zealand. Plentiful when European settlers arrived in New Zealand, its scientific description was published in 1845, but it was ...

Articles containing video clips

Species endangered by specimen collection

Taxobox binomials not recognized by IUCN