Laterite on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton first described and named a laterite formation in southern

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton first described and named a laterite formation in southern

Tropical weathering (laterization) is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The initial products of weathering are essentially kaolinized rocks called

Tropical weathering (laterization) is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The initial products of weathering are essentially kaolinized rocks called

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

and aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in AmE, American and CanE, Canadian English) is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately o ...

and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of w ...

content. They develop by intensive and prolonged weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs '' in situ'' (on site, with little or no movemen ...

of the underlying parent rock, usually when there are conditions of high temperatures and heavy rainfall with alternate wet and dry periods. Tropical weathering (''laterization'') is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

of the resulting soils. The majority of the land area containing laterites is between the tropics of Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

and Capricorn.

Laterite has commonly been referred to as a soil type as well as being a rock type. This and further variation in the modes of conceptualizing about laterite (e.g. also as a complete weathering profile or theory about weathering) has led to calls for the term to be abandoned altogether. At least a few researchers specializing in regolith

Regolith () is a blanket of unconsolidated, loose, heterogeneous superficial deposits covering solid rock. It includes dust, broken rocks, and other related materials and is present on Earth, the Moon, Mars, some asteroids, and other terrestri ...

development have considered that hopeless confusion has evolved around the name. Material that looks highly similar to the Indian laterite occurs abundantly worldwide.

Historically, laterite was cut into brick-like shapes and used in monument-building. After 1000 CE, construction at Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat (; km, អង្គរវត្ត, "City/Capital of Temples") is a temple complex in Cambodia and is the largest religious monument in the world, on a site measuring . Originally constructed as a Hindu temple dedicated to the g ...

and other southeast Asian sites changed to rectangular temple enclosures made of laterite, brick, and stone. Since the mid-1970s, some trial sections of bituminous-surfaced, low-volume roads have used laterite in place of stone as a base course. Thick laterite layers are porous and slightly permeable, so the layers can function as aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing, permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials ( gravel, sand, or silt). Groundwater from aquifers can be extracted using a water well. Aquifers vary greatly in their characteri ...

s in rural areas. Locally available laterites have been used in an acid solution, followed by precipitation to remove phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

and heavy metals at sewage-treatment facilities.

Laterites are a source of aluminum ore; the ore exists largely in clay mineral

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

Clay mineral ...

s and the hydroxide

Hydroxide is a diatomic anion with chemical formula OH−. It consists of an oxygen and hydrogen atom held together by a single covalent bond, and carries a negative electric charge. It is an important but usually minor constituent of water ...

s, gibbsite

Gibbsite, Al(OH)3, is one of the mineral forms of aluminium hydroxide. It is often designated as γ-Al(OH)3 (but sometimes as α-Al(OH)3.). It is also sometimes called hydrargillite (or hydrargyllite).

Gibbsite is an important ore of aluminiu ...

, boehmite, and diaspore, which resembles the composition of bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

. In Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

they once provided a major source of iron and aluminum ores. Laterite ores also were the early major source of nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

.

Definition and physical description

India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

in 1807. He named it laterite from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

word ''later

Later may refer to:

* Future, the time after the present

Television

* ''Later'' (talk show), a 1988–2001 American talk show

* '' Later... with Jools Holland'', a British music programme since 1992

* '' The Life and Times of Eddie Roberts'', or ...

'', which means a brick; this highly compacted and cemented soil can easily be cut into brick-shaped blocks for building. The word laterite has been used for variably cemented, sesquioxide-rich soil horizon

A soil horizon is a layer parallel to the soil surface whose physical, chemical and biological characteristics differ from the layers above and beneath. Horizons are defined in many cases by obvious physical features, mainly colour and texture. ...

s. A sesquioxide is an oxide with three atoms of oxygen and two metal atoms. It has also been used for any reddish soil at or near the Earth's surface.

Laterite covers are thick in the stable areas of the Western Ethiopian Shield The Western Ethiopian Shield is a small geological shield along the western border of Ethiopia. Its plutons were formed between 830 and 540 million years ago.

See also

*Craton

*Platform

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platfo ...

, on craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

s of the South American Plate, and on the Australian Shield. In Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (, ; meaning 'central province') is a state in central India. Its capital city, capital is Bhopal, and the largest city is Indore, with Jabalpur, Ujjain, Gwalior, Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar, and Rewa, India, Rewa being the othe ...

, India, the laterite which caps the plateau is thick. Laterites can be either soft and easily broken into smaller pieces, or firm and physically resistant. Basement

A basement or cellar is one or more Storey, floors of a building that are completely or partly below the storey, ground floor. It generally is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the Furnace (house heating), furnace, ...

rocks are buried under the thick weathered layer and rarely exposed. Lateritic soils form the uppermost part of the laterite cover.

In some places laterites contain pisolites and ferricrete and may be found in elevated positions as result of relief inversion

Inverted relief, inverted topography, or topographic inversion refers to landscape features that have reversed their elevation relative to other features. It most often occurs when low areas of a landscape become filled with lava or sediment th ...

.

Cliff Ollier

Cliff Ollier (born 26 October 1931) is a geologist, geomorphologist, soil scientist, emeritus professor and honorary research fellow, at the School of Earth and Geographical Sciences University of Western Australia. He was formerly at Australian ...

has criticized the usefulness of the concept given that it is used to mean different things to different authors. Reportedly some have used it for ferricrete, others for tropical red earth soil and yet others for soils profiles made, from top to bottom, of a crust, a mottled zone and a pallid zone. He cautions strongly against the concept of "lateritic deep weathering" since "it begs so many questions".

Formation

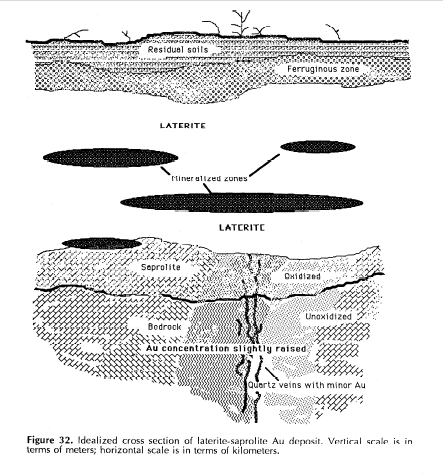

Tropical weathering (laterization) is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The initial products of weathering are essentially kaolinized rocks called

Tropical weathering (laterization) is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The initial products of weathering are essentially kaolinized rocks called saprolite

Saprolite is a chemically weathered rock. Saprolites form in the lower zones of soil profiles and represent deep weathering of the bedrock surface. In most outcrops its color comes from ferric compounds. Deeply weathered profiles are widesprea ...

s. A period of active laterization extended from about the mid-Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non- avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

to the mid- Quaternary periods (35 to 1.5 million years ago). Statistical analyses show that the transition in the mean and variance levels of 18O during the middle of the Pleistocene was abrupt. It seems this abrupt change was global and mainly represents an increase in ice mass; at about the same time an abrupt decrease in sea surface temperatures occurred; these two changes indicate a sudden global cooling. The rate of laterization would have decreased with the abrupt cooling of the earth. Weathering in tropical climates continues to this day, at a reduced rate.

Laterites are formed from the leaching of parent sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particle ...

s (sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

s, clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay part ...

s, limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

s); metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock ( protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, cau ...

s (schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

s, gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

es, migmatites); igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or l ...

s (granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies und ...

s, basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of a ...

s, gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

s, peridotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high prop ...

s); and mineralized proto-ores; which leaves the more insoluble

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solub ...

ions, predominantly iron and aluminum. The mechanism of leaching involves acid dissolving the host mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ...

lattice, followed by hydrolysis and precipitation of insoluble oxides and sulfates of iron, aluminum and silica under the high temperature conditions of a humid sub-tropical monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologica ...

.

An essential feature for the formation of laterite is the repetition of wet and dry season

The dry season is a yearly period of low rainfall, especially in the tropics. The weather in the tropics is dominated by the tropical rain belt, which moves from the northern to the southern tropics and back over the course of the year. The ...

s. Rocks are leached by percolating rain water during the wet season; the resulting solution containing the leached ions is brought to the surface by capillary action

Capillary action (sometimes called capillarity, capillary motion, capillary rise, capillary effect, or wicking) is the process of a liquid flowing in a narrow space without the assistance of, or even in opposition to, any external forces li ...

during the dry season. These ions form soluble salt compounds which dry on the surface; these salts are washed away during the next wet season. Laterite formation is favored in low topographical reliefs of gentle crests and plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ...

s which prevents erosion of the surface cover. The reaction zone where rocks are in contact with water—from the lowest to highest water table

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with water. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

Th ...

levels—is progressively depleted of the easily leached ions of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

, potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin '' kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosp ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

and magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ...

. A solution of these ions can have the correct pH to preferentially dissolve silicon oxide rather than the aluminum oxides and iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of w ...

s. Silcrete has been suggested to form in zones inrelatively dry "precipitating zones" of laterites. To the contrary, in the wetter parts of laterites subject to leaching ferricretes have been suggested to form.

The mineralogical and chemical compositions of laterites are dependent on their parent rocks. Laterites consist mainly of quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

, zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of th ...

, and oxides of titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resista ...

, iron, tin, aluminum and manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy u ...

, which remain during the course of weathering. Quartz is the most abundant relic mineral from the parent rock.

Laterites vary significantly according to their location, climate and depth. The main host minerals for nickel and cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, ...

can be either iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of w ...

s, clay mineral

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

Clay mineral ...

s or manganese oxides. Iron oxides are derived from mafic

A mafic mineral or rock is a silicate mineral or igneous rock rich in magnesium and iron. Most mafic minerals are dark in color, and common rock-forming mafic minerals include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Common mafic rocks includ ...

igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or l ...

s and other iron-rich rocks; bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

s are derived from granitic

A granitoid is a generic term for a diverse category of coarse-grained igneous rocks that consist predominantly of quartz, plagioclase, and alkali feldspar. Granitoids range from plagioclase-rich tonalites to alkali-rich syenites and from quart ...

igneous rock and other iron-poor rocks. Nickel laterites occur in zones of the earth which experienced prolonged tropical weathering of ultramafic rocks containing the ferro-magnesian minerals olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers qui ...

, pyroxene

The pyroxenes (commonly abbreviated to ''Px'') are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula , where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron (Fe II) ...

, and amphibole

Amphibole () is a group of inosilicate minerals, forming prism or needlelike crystals, composed of double chain tetrahedra, linked at the vertices and generally containing ions of iron and/or magnesium in their structures. Its IMA symbol is ...

.

Locations

Yves Tardy, from the ''French Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse'' and the ''Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique'', calculated that laterites cover about one-third of the Earth's continental land area. Lateritic soils are thesubsoil

Subsoil is the layer of soil under the topsoil on the surface of the ground. Like topsoil, it is composed of a variable mixture of small particles such as sand, silt and clay, but with a much lower percentage of organic matter and humus, and it ...

s of the equatorial forests, of the savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

s of the humid tropical regions, and of the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

ian steppes. They cover most of the land area between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn; areas not covered within these latitudes include the extreme western portion of South America, the southwestern portion of Africa, the desert regions of north-central Africa, the Arabian peninsula and the interior of Australia.

Some of the oldest and most highly deformed ultramafic rocks which underwent laterization are found as petrified fossil soils in the complex Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

shields in Brazil and Australia. Smaller highly deformed Alpine-type intrusives have formed laterite profiles in Guatemala, Colombia, Central Europe, India and Burma. Large thrust sheets of Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Creta ...

island arc

Island arcs are long chains of active volcanoes with intense seismic activity found along convergent tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have resulted from the descent of the lithosphere into the mantle alo ...

s and continental collision zones underwent laterization in New Caledonia, Cuba, Indonesian and the Philippines. Laterites reflect past weathering conditions; laterites which are found in present-day non-tropical areas are products of former geological epochs, when that area was near the equator. Present-day laterite occurring outside the humid tropics are considered to be indicators of climatic change, continental drift or a combination of both. In India, laterite soils occupy an area of 240,000 square kilometres

Uses

Agriculture

Laterite soils have a high clay content, which means they have higher cation exchange capacity and water-holding capacity than sandy soils. It is because the particles are so small, the water is trapped between them. After the rain, the water moves into the soil slowly. Due to intensive leaching, laterite soils lack in fertility in comparison to other soils, however they respond readily to manuring and irrigation. Palms are less likely to suffer from drought because the rainwater is held in the soil. However, if the structure of lateritic soils becomes degraded, a hard crust can form on the surface, which hinders water infiltration, the emergence of seedlings, and leads to increased runoff. It is possible to rehabilitate such soils, using a system called the 'bio-reclamation of degraded lands'. This involves using indigenous water-harvesting methods (such as planting pits and trenches), applying animal and plant residues, and planting high-value fruit trees and indigenous vegetable crops that are tolerant of drought conditions. These soils are most suitable for plantation crops. They are good for oil palm, tea, coffee and cashew cultivation. TheInternational Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics

The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is an international organization which conducts agricultural research for rural development, headquartered in Patancheru (Hyderabad, Telangana, India) with several re ...

(ICRISAT

The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is an international organization which conducts agricultural research for rural development, headquartered in Patancheru (Hyderabad, Telangana, India) with several re ...

) has employed this system to rehabilitate degraded laterite soils in Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagessmallholder farmers' incomes. In some places, these soils support grazing grounds and scrub forests.

When moist, laterites can easily be cut with a spade into regular-sized blocks. Laterite is mined while it is below the water table, so it is wet and soft. Upon exposure to air it gradually hardens as the moisture between the flat clay particles evaporates and the larger iron salts lock into a rigid

When moist, laterites can easily be cut with a spade into regular-sized blocks. Laterite is mined while it is below the water table, so it is wet and soft. Upon exposure to air it gradually hardens as the moisture between the flat clay particles evaporates and the larger iron salts lock into a rigid

The French surfaced roads in the Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam area with crushed laterite, stone or gravel. Kenya, during the mid-1970s, and Malawi, during the mid-1980s, constructed trial sections of bituminous-surfaced low-volume roads using laterite in place of stone as a base course. The laterite did not conform with any accepted specifications but performed equally well when compared with adjoining sections of road using stone or other stabilized material as a base. In 1984 US$40,000 per was saved in Malawi by using laterite in this way.

The French surfaced roads in the Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam area with crushed laterite, stone or gravel. Kenya, during the mid-1970s, and Malawi, during the mid-1980s, constructed trial sections of bituminous-surfaced low-volume roads using laterite in place of stone as a base course. The laterite did not conform with any accepted specifications but performed equally well when compared with adjoining sections of road using stone or other stabilized material as a base. In 1984 US$40,000 per was saved in Malawi by using laterite in this way.

Ores are concentrated in metalliferous laterites; aluminum is found in

Ores are concentrated in metalliferous laterites; aluminum is found in

The basaltic laterites of

The basaltic laterites of

Building blocks

lattice structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns th ...

and become resistant to atmospheric conditions. The art of quarrying laterite material into masonry

Masonry is the building of structures from individual units, which are often laid in and bound together by mortar; the term ''masonry'' can also refer to the units themselves. The common materials of masonry construction are bricks, building ...

is suspected to have been introduced from the Indian subcontinent. They harden like iron when they are exposed to air.

After 1000 CE Angkorian construction changed from circular or irregular earthen walls to rectangular temple enclosures of laterite, brick and stone structures. Geographic surveys show areas which have laterite stone alignments which may be foundations of temple sites that have not survived. The Khmer people constructed the Angkor monuments—which are widely distributed in Cambodia and Thailand—between the 9th and 13th centuries. The stone materials used were sandstone and laterite; brick had been used in monuments constructed in the 9th and 10th centuries. Two types of laterite can be identified; both types consist of the minerals kaolinite, quartz, hematite and goethite. Differences in the amounts of minor elements arsenic, antimony, vanadium and strontium were measured between the two laterites.

Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat (; km, អង្គរវត្ត, "City/Capital of Temples") is a temple complex in Cambodia and is the largest religious monument in the world, on a site measuring . Originally constructed as a Hindu temple dedicated to the g ...

—located in present-day Cambodia—is the largest religious structure built by Suryavarman II, who ruled the Khmer Empire from 1112 to 1152. It is a World Heritage site. The sandstone used for the building of Angkor Wat is Mesozoic sandstone quarried in the Phnom Kulen Mountains, about away from the temple. The foundations and internal parts of the temple contain laterite blocks behind the sandstone surface. The masonry was laid without joint mortar.

Road building

The French surfaced roads in the Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam area with crushed laterite, stone or gravel. Kenya, during the mid-1970s, and Malawi, during the mid-1980s, constructed trial sections of bituminous-surfaced low-volume roads using laterite in place of stone as a base course. The laterite did not conform with any accepted specifications but performed equally well when compared with adjoining sections of road using stone or other stabilized material as a base. In 1984 US$40,000 per was saved in Malawi by using laterite in this way.

The French surfaced roads in the Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam area with crushed laterite, stone or gravel. Kenya, during the mid-1970s, and Malawi, during the mid-1980s, constructed trial sections of bituminous-surfaced low-volume roads using laterite in place of stone as a base course. The laterite did not conform with any accepted specifications but performed equally well when compared with adjoining sections of road using stone or other stabilized material as a base. In 1984 US$40,000 per was saved in Malawi by using laterite in this way.

Water supply

Bedrock in tropical zones is often granite, gneiss, schist or sandstone; the thick laterite layer is porous and slightly permeable so the layer can function as an aquifer in rural areas. One example is the Southwestern Laterite (Cabook) Aquifer in Sri Lanka. This aquifer is on the southwest border of Sri Lanka, with the narrow Shallow Aquifers on Coastal Sands between it and the ocean. It has the considerable water-holding capacity, depending on the depth of the formation. The aquifer in this laterite recharges rapidly with the rains of April–May which follow the dry season of February–March, and continues to fill with themonsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

rains. The water table recedes slowly and is recharged several times during the rest of the year. In some high-density suburban areas the water table could recede to below ground level during a prolonged dry period of more than 65 days. The Cabook Aquifer laterites support relatively shallow aquifers that are accessible to dug wells.

Waste water treatment

In Northern Ireland, phosphorus enrichment of lakes due to agriculture is a significant problem. Locally available laterite—a low-grade bauxite rich in iron and aluminum—is used in acid solution, followed by precipitation to remove phosphorus and heavy metals at several sewage treatment facilities. Calcium-, iron- and aluminum-rich solid media are recommended for phosphorus removal. A study, using both laboratory tests and pilot-scale constructed wetlands, reports the effectiveness of granular laterite in removing phosphorus and heavy metals from landfillleachate

A leachate is any liquid that, in the course of passing through matter, extracts soluble or suspended solids, or any other component of the material through which it has passed.

Leachate is a widely used term in the environmental sciences wher ...

. Initial laboratory studies show that laterite is capable of 99% removal of phosphorus from solution. A pilot-scale experimental facility containing laterite achieved 96% removal of phosphorus. This removal is greater than reported in other systems. Initial removals of aluminum and iron by pilot-scale facilities have been up to 85% and 98% respectively. Percolating columns of laterite removed enough cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and h ...

and lead

Lead is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metals, heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale of mineral hardness#Intermediate ...

to undetectable concentrations. There is a possible application of this low-cost, low-technology, visually unobtrusive, efficient system for rural areas with dispersed point sources of pollution.

Ores

bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

s, iron and manganese are found in iron-rich hard crusts, nickel and copper are found in disintegrated rocks, and gold is found in mottled clays.

Bauxite

Bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO(O ...

ore is the main source of aluminum. Bauxite is a variety of laterite (residual sedimentary rock), so it has no precise chemical formula. It is composed mainly of hydrated alumina minerals such as gibbsite

Gibbsite, Al(OH)3, is one of the mineral forms of aluminium hydroxide. It is often designated as γ-Al(OH)3 (but sometimes as α-Al(OH)3.). It is also sometimes called hydrargillite (or hydrargyllite).

Gibbsite is an important ore of aluminiu ...

l(OH)3 or Al2O3 . 3H2O)in newer tropical deposits; in older subtropical, temperate deposits the major minerals are boehmite �-AlO(OH) or Al2O3.H2Oand some diaspore �-AlO(OH) or Al2O3.H2O The average chemical composition of bauxite, by weight, is 45 to 60% Al2O3 and 20 to 30% Fe2O3. The remaining weight consists of silicas (quartz, chalcedony

Chalcedony ( , or ) is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite. These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monocl ...

and kaolinite

Kaolinite ( ) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4. It is an important industrial mineral. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica () linked through oxygen atoms to one octahed ...

), carbonates (calcite

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scra ...

, magnesite

Magnesite is a mineral with the chemical formula ( magnesium carbonate). Iron, manganese, cobalt, and nickel may occur as admixtures, but only in small amounts.

Occurrence

Magnesite occurs as veins in and an alteration product of ultramafic ...

and dolomite), titanium dioxide and water. Bauxites of economical interest must be low in kaolinite. Formation of lateritic bauxites occurs worldwide in the 145- to 2-million-year-old Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

and Tertiary coastal plains. The bauxites form elongate belts, sometimes hundreds of kilometers long, parallel to Lower Tertiary shorelines in India and South America; their distribution is not related to a particular mineralogical composition of the parent rock. Many high-level bauxites are formed in coastal plains which were subsequently uplifted to their present altitude.

Iron

The basaltic laterites of

The basaltic laterites of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

were formed by extensive chemical weathering of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of a ...

s during a period of volcanic activity. They reach a maximum thickness of and once provided a major source of iron and aluminum ore. Percolating waters caused degradation of the parent basalt and preferential precipitation by acidic water through the lattice left the iron and aluminum ores. Primary olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers qui ...

, plagioclase

Plagioclase is a series of tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continuous solid solution series, more pro ...

feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagioclase'' (sodium-calcium) feld ...

and augite

Augite is a common rock-forming pyroxene mineral with formula . The crystals are monoclinic and prismatic. Augite has two prominent cleavages, meeting at angles near 90 degrees.

Characteristics

Augite is a solid solution in the pyroxene group ...

were successively broken down and replaced by a mineral assemblage consisting of hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of ...

, gibbsite

Gibbsite, Al(OH)3, is one of the mineral forms of aluminium hydroxide. It is often designated as γ-Al(OH)3 (but sometimes as α-Al(OH)3.). It is also sometimes called hydrargillite (or hydrargyllite).

Gibbsite is an important ore of aluminiu ...

, goethite

Goethite (, ) is a mineral of the diaspore group, consisting of iron(III) oxide-hydroxide, specifically the "α" polymorph. It is found in soil and other low-temperature environments such as sediment. Goethite has been well known since ancient ...

, anatase

Anatase is a metastable mineral form of titanium dioxide (TiO2) with a tetragonal crystal structure. Although colorless or white when pure, anatase in nature is usually a black solid due to impurities. Three other polymorphs (or mineral forms ...

, halloysite and kaolinite

Kaolinite ( ) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4. It is an important industrial mineral. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica () linked through oxygen atoms to one octahed ...

.

Nickel

Laterite ores were the major source of early nickel. Rich laterite deposits in New Caledonia were mined starting the end of the 19th century to produce white metal. The discovery of sulfide deposits ofSudbury Sudbury may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sudbury Reef, Queensland

Canada

* Greater Sudbury, Ontario (official name; the city continues to be known simply as Sudbury for most purposes)

** Sudbury (electoral district), one of the city's federal e ...

, Ontario, Canada, during the early part of the 20th century shifted the focus to sulfides for nickel extraction. About 70% of the Earth's land-based nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

resources are contained in laterites; they currently account for about 40% of the world nickel production. In 1950 laterite-source nickel was less than 10% of total production, in 2003 it accounted for 42%, and by 2012 the share of laterite-source nickel was expected to be 51%. The four main areas in the world with the largest nickel laterite resources are New Caledonia, with 21%; Australia, with 20%; the Philippines, with 17%; and Indonesia, with 12%.

See also

* Ferricrete – stony particles conglomerated into rock by oxidized iron compounds from ground water * *References

{{Authority control Sedimentology Weathering Ore deposits Aluminium minerals Pedology Building materials Soil-based building materials Regolith