Lakanal House Aug 2021 Outside Signage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

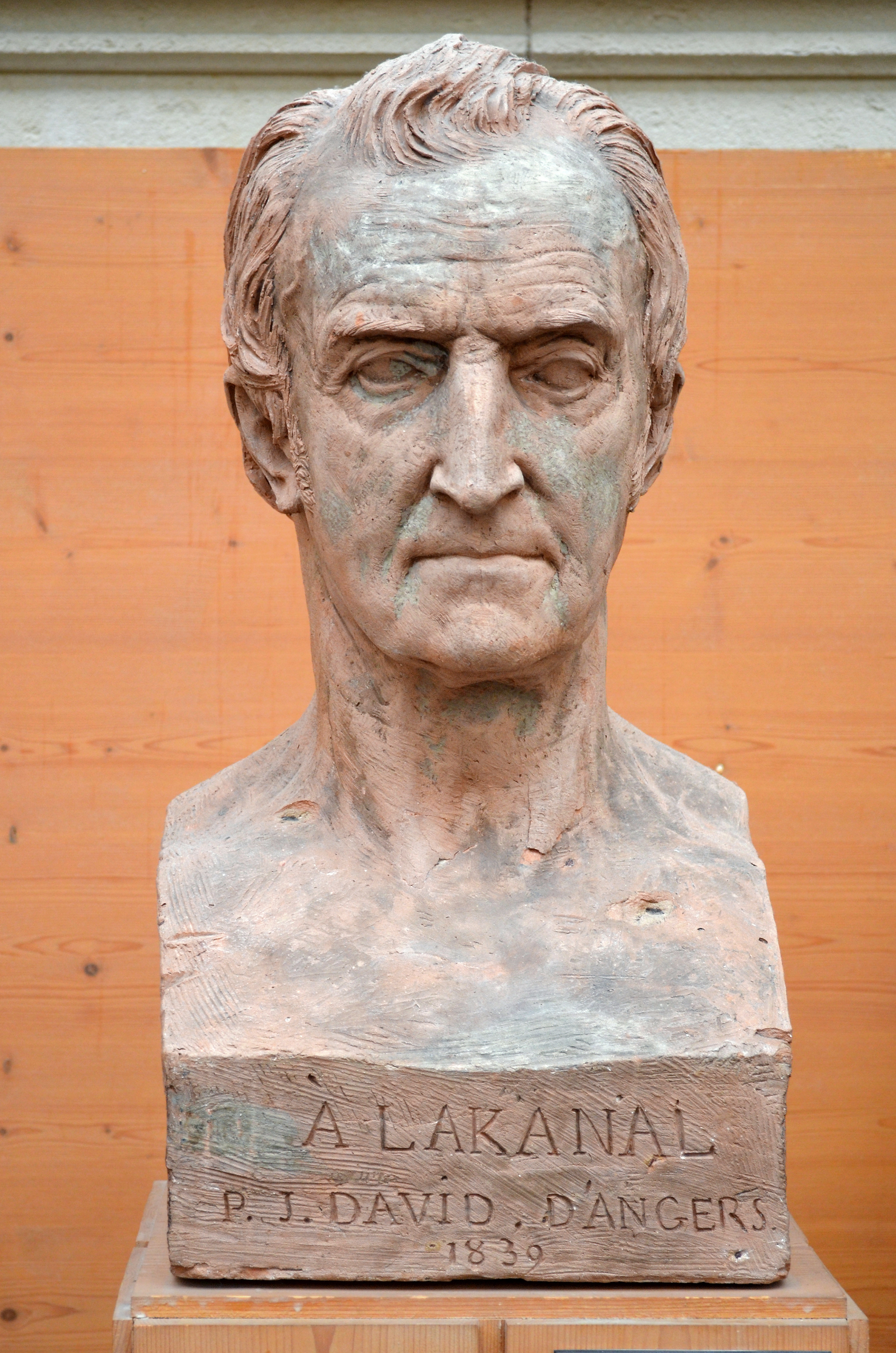

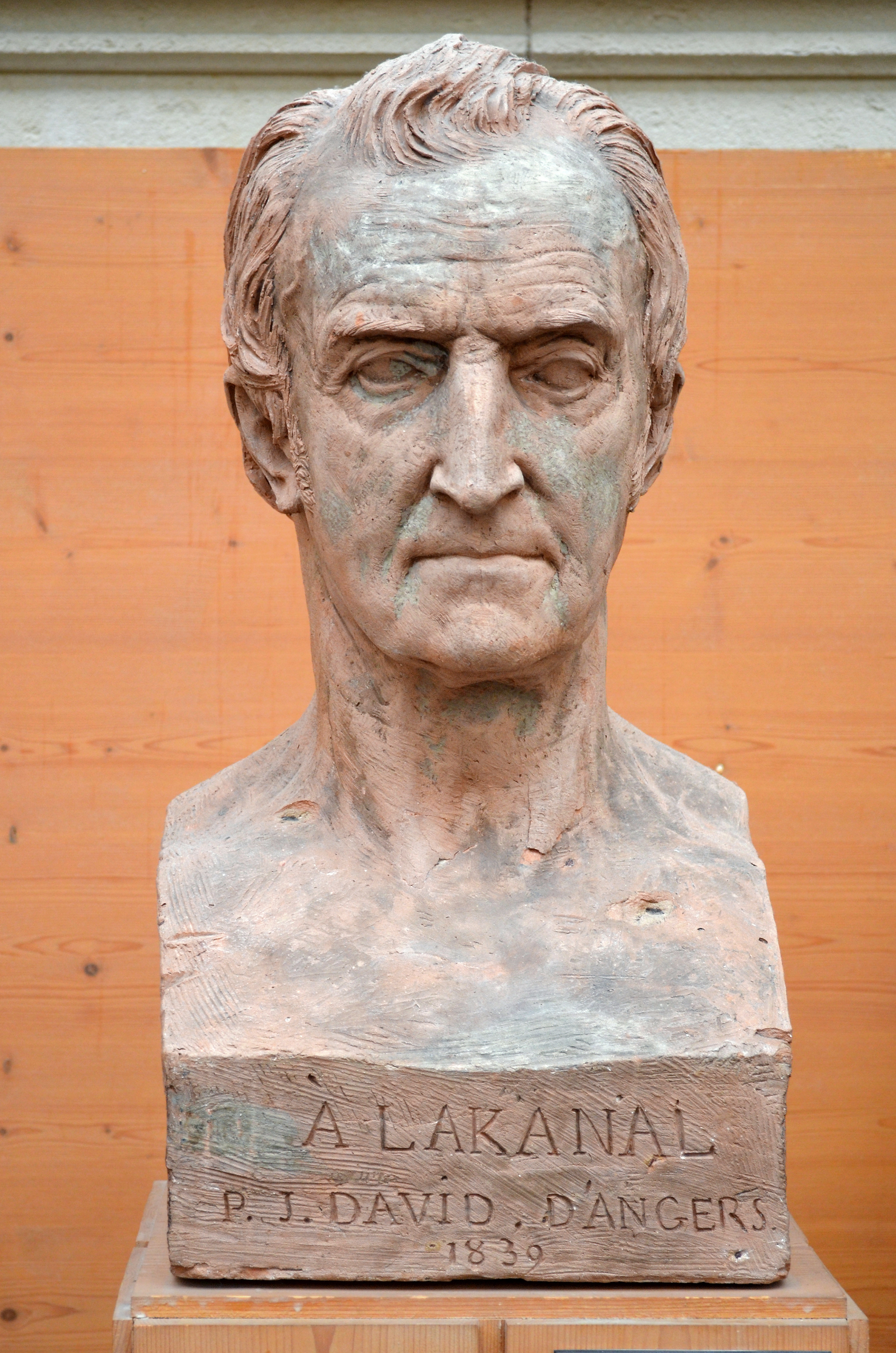

Joseph Lakanal (July 14, 1762 – February 14, 1845) was a French

Under the

Under the

''Bio sketch''

(in French)

(in French)

(in French) {{DEFAULTSORT:Lakanal, Joseph 1762 births 1845 deaths People from Ariège (department) Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Deputies to the French National Convention Members of the Council of Five Hundred Regicides of Louis XVI French academics Members of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques French Freemasons

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, and an original member of the ''Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute m ...

''.

Early career

Born inSerres

Sérres ( el, Σέρρες ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northe ...

, in present-day Ariège, his name was originally ''Lacanal'', and was altered to distinguish him from his Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

brothers. He studied theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, and joined one of the teaching congregations (''Pères de la Doctrine Chrétienne''), and for fourteen years taught in their schools. He was professor of rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

at Bourges

Bourges () is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre. It is the capital of the department of Cher, and also was the capital city of the former province of Berry.

History

The name of the commune derives either from the Bituriges, t ...

, and of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

at Moulins.

He was elected by his native ''département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level ("territorial collectivity, territorial collectivities"), between the regions of France, admin ...

'' to the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

of the French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

in 1792, where he sat until 1795; Lakanal was one of the noted administrators of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. At the time of his election, he was acting as vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

to his uncle Bernard Font

Bernard (''Bernhard'') is a French language, French and West Germanic masculine given name. It is also a surname.

The name is attested from at least the 9th century. West Germanic ''Bernhard'' is composed from the two elements ''bern'' "bear" an ...

(1723–1800), the constitutional bishop

During the French Revolution, a constitutional bishop was a Catholic bishop elected from among the clergy who had sworn to uphold the Civil Constitution of the Clergy between 1791 and 1801.

History

Constitutional bishops were often priests wit ...

of Pamiers

Pamiers (; oc, Pàmias ) is a commune and largest city in the Ariège department in the Occitanie region in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. It is the most populous commune in the Ariège department, although it ...

. In the Convention, he sat with The Mountain

The Mountain (french: La Montagne) was a political group during the French Revolution. Its members, called the Montagnards (), sat on the highest benches in the National Convention.

They were the most radical group and opposed the Girondins. Th ...

and voted for the execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

of King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

.

Projects and reforms

Lakanal became a member of theCommittee of Public Instruction

The Committee of Public Instruction (french: Comité de l'Instruction Publique), often called the Committee of Public Education, was established in 1791 by the Legislative Assembly in an attempt to reorder the education system in France. The Com ...

early in 1793, and after carrying many useful decrees on the preservation of national monuments, on the military schools

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally provides education in a military environment, the exact definition depending on the country concerned. ...

, on the reorganization of the '' Jardin des Plantes'' as the ''Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

'', and other matters (such as the creation of the '' École publique des Langues Orientales vivantes''), he brought forward on June 26 his ''Projet d'éducation nationale'' (printed at the Imprimerie Nationale

The Imprimerie nationale (), known also as IN Groupe brand, is a company specialized in the production of secure documents, such as identity cards and passports, and a supplier of public utility identification applications. Owned by the French st ...

), which proposed to lay the burden or primary education

Primary education or elementary education is typically the first stage of formal education, coming after preschool/kindergarten and before secondary school. Primary education takes place in ''primary schools'', ''elementary schools'', or first ...

on the public funds, but to leave secondary education

Secondary education or post-primary education covers two phases on the International Standard Classification of Education scale. Level 2 or lower secondary education (less commonly junior secondary education) is considered the second and final pha ...

to private enterprise; public ''fête

In Britain and some of its former colonies, fêtes are traditional public festivals, held outdoors and organised to raise funds for a charity. They typically include entertainment and the sale of goods and refreshments.

Village fêtes

Village f� ...

s'' were also assigned specified sums, and a central commission was to be entrusted with educational questions.

The project, to which Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (3 May 174820 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (), was a French Roman Catholic '' abbé'', clergyman, and political writer who was the chief political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also ...

also contributed, was refused by the Convention, who submitted the whole question to a special Commission of six, which, under the influence of Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

, adopted a report by Louis-Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau

Louis-Michel le Peletier, Marquis of Saint-Fargeau (sometimes spelled Lepeletier; 29 May 176020 January 1793) was a French politician and martyr of the French Revolution.

Career

Born in Paris, he belonged to a well-known family, his great-gran ...

(shortly before his death).

Lakanal, who was a member of the commission, now began to work for the organization of higher education

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after completi ...

, and, abandoning the principle of his ''Projet'', advocated the establishment of state-aided schools for primary, secondary and university education. In October 1793, he was sent by the Convention to the south-western ''départements'' and did not return to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

until after the revolution of Thermidor that toppled Robespierre.

Thermidor and Directory

He became president of the Education Committee, and promptly abolished the system which had had Robespierre's support. He drew up schemes fornormal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to Teacher education, train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high s ...

s of ''départements'', for primary schools (in accordance with his previous ''Projet'') and central schools; Lakanal accepted resolutions against his own system, but continued his educational reforms after his election to the Council of the Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred (''Conseil des Cinq-Cents''), or simply the Five Hundred, was the lower house of the legislature of France under the Constitution of the Year III. It existed during the period commonly known (from the name of the e ...

in 1795.

In 1799 he was sent by the Directory

Directory may refer to:

* Directory (computing), or folder, a file system structure in which to store computer files

* Directory (OpenVMS command)

* Directory service, a software application for organizing information about a computer network's u ...

to organize the defence of the four ''départments'' on the left bank of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

(in present-day Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

), threatened by the invasion of counter-Revolution forces (the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

).

Later life and exile

Under the

Under the Consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of diplomatic mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth coun ...

and Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

, Lakanal resumed his professional work, as a professor at the Lycée Charlemagne

The Lycée Charlemagne is located in the Marais quarter of the 4th arrondissement of Paris, the capital city of France.

Constructed many centuries before it became a lycée, the building originally served as the home of the Order of the Jesuit ...

, and after the battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

(1815), he retired to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. He was welcomed there by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, and the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

gave him a grant of 500 acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

s (2 km²) in the Vine and Olive Colony

The Vine and Olive Colony was an effort by a group of French Bonapartists who, fearing for their lives after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte and the Bourbon Restoration, attempted to establish an agricultural settlement growing wine grapes and oli ...

in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. He then later became a planter, therefore owning slaves, and was afterward chosen president of the ''University of Louisiana'' that he reorganized with the support of local masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

s, known today as Tulane University

Tulane University, officially the Tulane University of Louisiana, is a private university, private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by seven young medical doctors, it turned into ...

.

He returned to France in 1834, and published in 1838 an ''Expos sommaire des travaux de Joseph Lakanal''. Shortly afterwards, in spite of his advanced age, Lakanal married a second time. He died in Paris; his widow died in 1881. Lakanal's '' éloge'' at the Academy of Moral and Political Science, of which he was a member, was pronounced by the Comte de Rémusat (February 16, 1845), and a ''Notice historique'' by François Mignet

François Auguste Marie Mignet (, 8 May 1796 – 24 March 1884) was a French journalist and historian of the French Revolution.

Biography

He was born in Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône), France. His father was a locksmith from the Vendée ...

was read on May 2, 1857.

Freemasonry

Probably initiated at a Moulins lodge between 1786 and 1788, Lakanal was member of "Le point parfait" lodge in Paris from 1790. After the Revolution, he created two High Degree Chapters "La Triple Harmonie" and "L'Abeille Impériale".References

*External links

''Bio sketch''

(in French)

(in French)

(in French) {{DEFAULTSORT:Lakanal, Joseph 1762 births 1845 deaths People from Ariège (department) Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Deputies to the French National Convention Members of the Council of Five Hundred Regicides of Louis XVI French academics Members of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques French Freemasons