The Labour Party is a

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

in the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

that has been described as an alliance of

social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

,

democratic socialists

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within ...

and

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

ists.

The Labour Party sits on the

centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

of the political spectrum. In all general elections since

1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

, Labour has been either the governing party or the

Official Opposition

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''t ...

. There have been six Labour

prime ministers

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is no ...

and thirteen Labour

ministries. The party holds the annual

Labour Party Conference

The Labour Party Conference is the annual conference of the British Labour Party. It is formally the supreme decision-making body of the party and is traditionally held in the final week of September, during the party conference season when th ...

, at which party policy is formulated.

The party was founded in 1900, having grown out of the

trade union movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

and

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

parties

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature ...

of the 19th century. It overtook the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

to become the main opposition to the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

in the early 1920s, forming two minority governments under

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

in the 1920s and early 1930s. Labour served in the

wartime coalition of 1940–1945, after which

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

's

Labour government established the

National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

and expanded the

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

from 1945 to 1951. Under

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

and

James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

, Labour again governed from

1964 to 1970 and

1974 to 1979. In the 1990s,

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

took Labour to the

centre

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

* Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentri ...

as part of his

New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

project which governed under Blair and then

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony B ...

from 1997 to 2010.

The Labour Party currently forms the Official Opposition in the

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

, having won the second-largest number of seats in the

2019 general election. The

leader of the party and

leader of the opposition is

Keir Starmer

Sir Keir Rodney Starmer (; born 2 September 1962) is a British politician and barrister who has served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party since 2020. He has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Holborn and St Pancras s ...

. Labour is the largest party in the

Senedd (Welsh Parliament), being the only party in the

current Welsh government. The party is the third-largest in the

Scottish Parliament, behind the

Scottish National Party and the

Scottish Conservatives

The Scottish Conservative & Unionist Party ( gd, Pàrtaidh Tòraidheach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Tory an Unionist Pairty), often known simply as the Scottish Conservatives and colloquially as the Scottish Tories, is a centre-right political par ...

. Labour is a member of the

Party of European Socialists

The Party of European Socialists (PES) is a social democratic and progressive European political party.

The PES comprises national-level political parties from all member states of the European Union (EU) plus Norway and the United Kingdom. ...

and

Progressive Alliance

The Progressive Alliance (PA) is a political international of social democratic and progressive political parties and organisations founded on 22 May 2013 in Leipzig, Germany. The alliance was formed as an alternative to the existing Socia ...

, and holds observer status in the

Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism. It consists mostly of socialist and labour-oriented political parties and organisations ...

. The party includes semi-autonomous

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

,

Scottish,

Welsh and

Northern Irish branches; however, it supports the

Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) ( ga, Páirtí Sóisialta Daonlathach an Lucht Oibre) is a social-democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland ...

(SDLP) in Northern Ireland, while still organising there. , Labour has around 450,000 registered members,

one of the

largest memberships of any party in Europe.

History

Origins and the Independent Labour Party (1860–1900)

The Labour Party originated in the late 19th century, meeting the demand for a new political party to represent the interests and needs of the urban working class, a demographic which had increased in number, and many of whom only gained

suffrage with the passage of the

Representation of the People Act 1884

In the United Kingdom under the premiership of William Gladstone, the Representation of the People Act 1884 (48 & 49 Vict. c. 3, also known informally as the Third Reform Act) and the Redistribution Act of the following year were laws which f ...

. Some members of the trades union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after further extensions of the voting franchise in 1867 and 1885, the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

endorsed some

trade-union sponsored candidates. The first

Lib–Lab candidate to stand was

George Odger

George Odger (1813–4 March 1877) was a pioneer British trade unionist and radical politician. He is best remembered as the head of the London Trades Council during the period of formation of the Trades Union Congress and as the first President ...

in the

Southwark by-election of 1870. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time, with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP), the intellectual and largely middle-class

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

, the Marxist

Social Democratic Federation and the

Scottish Labour Party.

At the

1895 general election, the ILP put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes.

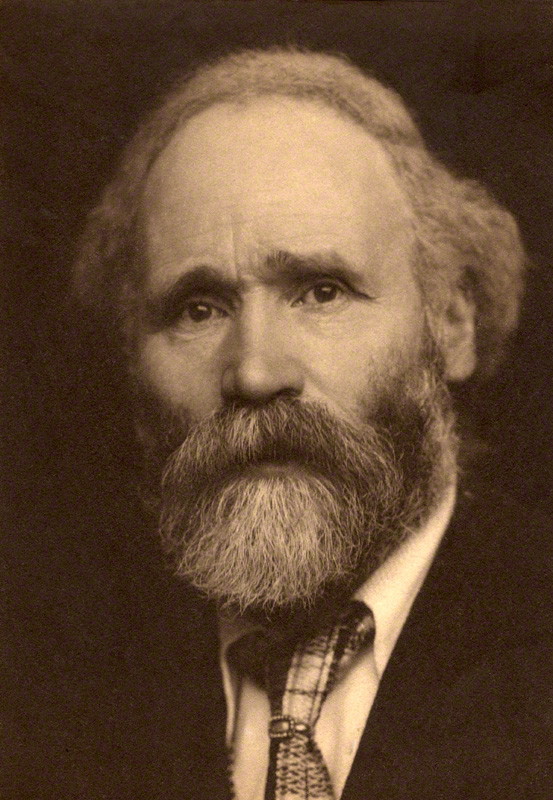

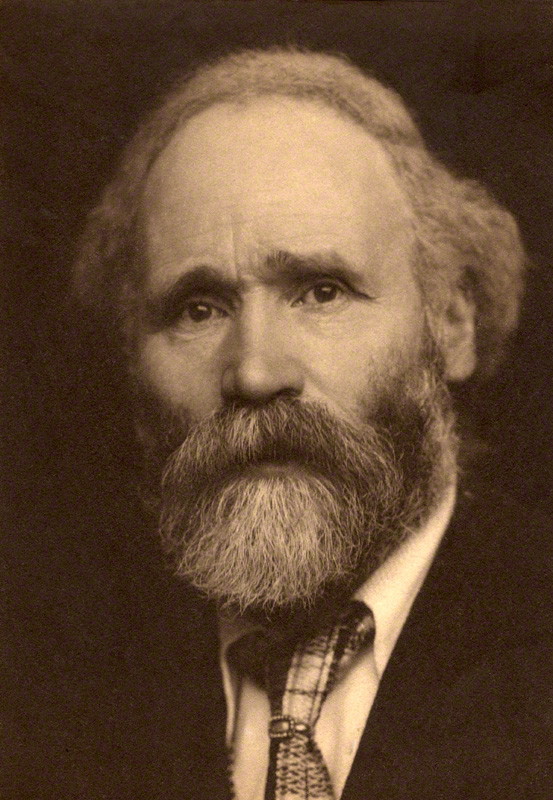

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

, the leader of the party, believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups. Hardie's roots as a lay preacher contributed to an ethos in the party which led to the comment by 1950s General Secretary

Morgan Phillips

Morgan Walter Phillips (18 June 1902 – 15 January 1963) was a colliery worker and trade union activist who became the General Secretary of the British Labour Party, involved in two of the party's election victories.

Life

Born in Aberdare, ...

that "Socialism in Britain owed more to Methodism than Marx".

Labour Representation Committee (1900–1906)

In 1899, a

Doncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

member of the

Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

** Pan am ...

, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the

Trade Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances ...

call a special conference to bring together all left-wing organisations and form them into a single body that would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and the proposed conference was held at the

Congregational Memorial Hall

The Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street, London was built to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Great Ejection of Black Bartholomew's Day, resulting from the 1662 Act of Uniformity which restored the Anglican church. The two tho ...

on Farringdon Street, London on 26 and 27 February 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations—the trades unions present represented almost half of the membership of the TUC.

After a debate, the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour."

This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to co-ordinate attempts to support MPs sponsored by trade unions and represent the working-class population. It had no single leader, and in the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The

1900 general election, also referred to as the "Khaki election", came too soon for the new party to campaign effectively and total expenses for the election only came to £33. Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful:

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

in

Merthyr Tydfil and

Richard Bell in

Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby g ...

.

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901

Taff Vale Case

''Taff Vale Railway Co v Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants'' [1901UKHL 1 commonly known as the ''Taff Vale case'', is a formative case in UK labour law. It held that, at common law, Trade union, unions could be liable for loss of profits t ...

, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union being ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal, since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative Government of Arthur Balfour to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

in opposition to the Conservatives' landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems.

In the

1906 general election, the LRC won 29 seats—helped by a

secret 1903 pact between

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

and

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone that aimed to avoid splitting the opposition vote between Labour and Liberal candidates in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.

In their first meeting after the election the group's Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name "The Labour Party" formally (15 February 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the leader), although only by one vote over

David Shackleton

Sir David James Shackleton (21 November 1863 – 1 August 1938) was a cotton worker and trade unionist who became the third Labour Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom, following the formation of the Labour Representation Committee. He ...

after several ballots. In the party's early years the

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have individual membership until 1918 but operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies. The

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal Government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.

The

People's History Museum

The People's History Museum (the National Museum of Labour History until 2001) in Manchester, England, is the UK's national centre for the collection, conservation, interpretation and study of material relating to the history of working people ...

in

Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

holds the minutes of the first Labour Party meeting in 1906 and has them on display in the Main Galleries.

Also within the museum is the Labour History Archive and Study Centre, which holds the collection of the Labour Party, with material ranging from 1900 to the present day.

Early years (1906–1923)

In 1907 the new party held its first annual conference in

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

, a city in which Hardie in 1905 had served as an LRC election agent for

William Walker. Despite Walker's election to the party executive, the connection with the north of Ireland was brief. At the height of the

Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1912. Unionists in Ulster, d ...

in 1913, the party, in deference to the

Irish Labour Party

The Labour Party ( ga, Páirtí an Lucht Oibre, literally "Party of the Working People") is a centre-left and social-democratic political party in the Republic of Ireland. Founded on 28 May 1912 in Clonmel, County Tipperary, by James Connolly, ...

, decided not to stand candidates in Ireland, a policy the party maintained after

partition in 1921.

[Aaron Edwards (2015), "The British Labour Party and the tragedy of Northern Ireland Labour" in The ''British Labour Party and twentieth-century Ireland: The cause of Ireland, the cause of Labour'', Lawrence Marley ed.. Manchester University Press, . pp. 119–134] Labour was to be a British, not a United Kingdom, party.

The Belfast conference itself was remembered for first raising the question of whether sovereignty lay with the annual conference, as in the inherited tradition of trade union democracy, or with the PLP. Hardie shocked the delegates in the closing session by threatening to resign from the PLP over an amendment to a resolution on equal suffrage for women that would have bound MPs to oppose any compromise legislation that would extend votes to women on the basis of the existing property franchise. The PLP defused the crisis by allowing Hardie to vote as he wished on the subject. The precedent became the basis of a "conscience clause" in its standing orders, and would be invoked by party leader

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

in 1981 to argue that the will of the conference should not always bind the PLP.

The

December 1910 general election saw 42 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons, a significant victory since, a year before the election, the House of Lords had passed the

Osborne judgment ruling that trade union members would have to 'opt in' to sending contributions to Labour, rather than their consent being presumed. The governing Liberals were unwilling to repeal this judicial decision with primary legislation. The height of Liberal compromise was to introduce a wage for Members of Parliament to remove the need to involve the trade unions. By 1913, faced with the opposition of the largest trade unions, the Liberal government passed the Trade Disputes Act to allow unions to fund Labour MPs once more without seeking the express consent of their members.

During the First World War, the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict but opposition to the war grew within the party as time went on.

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, a notable

anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

became the main figure of authority within the party. He was soon accepted into Prime Minister

H. H. Asquith's war cabinet, becoming the first Labour Party member to serve in government. Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the coalition the

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

was instrumental in opposing conscription through organisations such as the

Non-Conscription Fellowship while a Labour Party affiliate, the

British Socialist Party, organised a number of unofficial strikes. Arthur Henderson resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amid calls for party unity to be replaced by

George Barnes. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the war, the

co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the

Co-operative Party

The Co-operative Party is a centre-left political party in the United Kingdom, supporting co-operative values and principles. Established in 1917, the Co-operative Party was founded by co-operative societies to campaign politically for the fair ...

after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party.

At the end of the First World War, the Government was attempting to provide support for the newly re-established

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

against

Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. Henderson sent telegrams to all local Labour Party organisations to ask them to organise demonstrations against supporting Poland, later forming the Council of Action, to further organise strikes and protests. Due to the number of demonstrations and the potential industrial impact across the country, Churchill and the Government was forced to end support for the Polish war effort.

Henderson turned his attention to building a strong constituency-based support network for the Labour Party. Previously, it had little national organisation, based largely on branches of unions and socialist societies. Working with Ramsay MacDonald and Sidney Webb, Henderson in 1918 established a national network of constituency organisations. They operated separately from trade unions and the National Executive Committee and were open to everyone sympathetic to the party's policies. Secondly, Henderson secured the adoption of a comprehensive statement of party policies, as drafted by

Sidney Webb. Entitled "Labour and the New Social Order", it remained the basic Labour platform until 1950. It proclaimed a socialist party whose principles included a guaranteed minimum standard of living for everyone, nationalisation of industry, and heavy taxation of large incomes and of wealth. It was in 1918 that

Clause IV

Clause IV is part of the Labour Party Rule Book, which sets out the aims and values of the (UK) Labour Party. The original clause, adopted in 1918, called for common ownership of industry, and proved controversial in later years; Hugh Gaitskell a ...

, as drafted by

Sidney Webb, was adopted into

Labour's constitution, committing the party to work towards "the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". With the

Representation of the People Act 1918, almost all adult men (excepting only peers, criminals and lunatics) and most women over the age of thirty were given the right to vote, almost tripling the British electorate at a stroke, from 7.7 million in 1912 to 21.4 million in 1918. This set the scene for a surge in Labour representation in parliament.

The

Communist Party of Great Britain was refused affiliation to the Labour Party between 1921 and 1923.

Meanwhile, the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

declined rapidly, and the party also suffered a catastrophic split which allowed the Labour Party to gain much of the Liberals' support. With the Liberals thus in disarray, Labour won 142 seats in

1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

, making it the second-largest political group in the House of Commons and the

official opposition to the Conservative government. After the election Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official

leader of the Labour Party.

First Labour government and period in opposition (1923–1929)

The

1923 general election was fought on the Conservatives'

protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

proposals, but although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, necessitating the formation of a government supporting

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. Thus, with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals,

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

became the first ever Labour Prime Minister in January 1924, forming the first Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons). The most significant achievement of the first Labour government was the

Wheatley Housing Act, which began a building programme of 500,000

municipal houses for rental to low paid workers. Legislation on education, unemployment, social insurance and tenant protection was also passed. However, because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals it was unable to implement many of its more contentious policies such as

nationalisation of the coal industry, or a

capital levy. Although no radical changes were introduced, Labour demonstrated that they were capable of governing.

While there were no major labour strikes during his term, MacDonald acted swiftly to end those that did erupt. When the Labour Party executive criticised the government, he replied that, "public doles,

Poplarism local defiance of the national government], strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism, but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement."

The government collapsed after only ten months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the

Patrick Hastings#Campbell Case, Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing

1924 general election saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the forged

Zinoviev letter, in which Moscow talked about a Communist revolution in Britain. The letter had little impact on the Labour vote—which held up. It was the collapse of the Liberal party that led to the Conservative landslide. The Conservatives were returned to power although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% to a third of the popular vote, most Conservative gains being at the expense of the Liberals. However, many Labourites blamed for years their defeat on foul play (the Zinoviev letter), thereby according to

A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

misunderstanding the political forces at work and delaying needed reforms in the party.

In opposition, MacDonald continued his policy of presenting the Labour Party as a moderate force. The party opposed the

1926 general strike

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governme ...

, arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box. The leaders were also fearful of Communist influence orchestrated from Moscow. The party had a distinctive and suspicious foreign policy based on pacifism. Its leaders believed that peace was impossible because of capitalism, secret diplomacy, and the trade in armaments. That is it stressed material factors that ignored the psychological memories of the Great War, and the highly emotional tensions regarding nationalism and the boundaries of the countries.

Second Labour government (1929–1931)

In the

1929 general election, the Labour Party became the largest in the House of Commons for the first time, with 287 seats and 37.1% of the popular vote. However MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government. MacDonald went on to appoint Britain's first woman cabinet minister;

Margaret Bondfield, who was appointed

Minister of Labour Minister of Labour (in British English) or Labor (in American English) is typically a cabinet-level position with portfolio responsibility for setting national labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, traini ...

. MacDonald's second government was in a stronger parliamentary position than his first, and in 1930 Labour was able to pass legislation to raise unemployment pay, improve wages and conditions in the coal industry (i.e. the issues behind the General Strike) and pass a housing act which focused on slum clearances.

The government soon found itself engulfed in crisis as the

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

and eventual

Great Depression occurred soon after the government came to power, and the slump in global trade hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930 unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million.

[Davies, A.J. (1996) ''To Build A New Jerusalem: The British Labour Party from Keir Hardie to Tony Blair'', Abacus] The government had no effective answers to the deteriorating financial situation, and by 1931 there was much fear that the budget was unbalanced, which was born out by the independent

May Report which triggered a confidence crisis and a run on the pound. The cabinet deadlocked over its response, with several influential members unwilling to support the budget cuts (in particular a cut in the rate of unemployment benefit) which were pressed by the civil service and opposition parties.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden

Philip Snowden, 1st Viscount Snowden, PC (; 18 July 1864 – 15 May 1937) was a British politician. A strong speaker, he became popular in trade union circles for his denunciation of capitalism as unethical and his promise of a socialist utop ...

refused to consider

deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit; the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budget ...

or tariffs as alternative solutions. When a final vote was taken, the Cabinet was split 11–9 with a minority, including many political heavyweights such as

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

and

George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spe ...

, threatening to resign rather than agree to the cuts. The unworkable split, on 24 August 1931, made the government resign. MacDonald was encouraged by King

George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

to form an all-party

National Government to deal with the immediate crisis.

The financial crisis grew worse, and decisive government action was needed, as the leaders of both the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party met with King George V and MacDonald, at first to discuss support for the spending cuts but later to discuss the shape of the next government. The king played the central role in demanding a National government be formed. On 24 August, MacDonald agreed to form a National Government composed of men from all parties with the specific aim of balancing the Budget and restoring confidence. The new cabinet had four Labourites (who formed a

National Labour group) who stood with MacDonald, plus four Conservatives (led by Baldwin, Chamberlain) and two Liberals. MacDonald's moves aroused great anger among a large majority of Labour Party activists who felt betrayed. Labour unions were strongly opposed and the Labour Party officially repudiated the new National government. It expelled MacDonald and his supporters and made Henderson the leader of the main Labour party. Henderson led it into

the general election on 27 October against the three-party National coalition. It was a disaster for Labour, which was reduced to a small minority of 52 seats. The Conservative-dominated National Government, led by MacDonald, won the largest landslide in British political history.

In 1931, Labour campaigned on opposition to public spending cuts, but found it difficult to defend the record of the party's former government and the fact that most of the cuts had been agreed before it fell. Historian Andrew Thorpe argues that Labour lost credibility by 1931 as unemployment soared, especially in coal, textiles, shipbuilding, and steel. The working class increasingly lost confidence in the ability of Labour to solve the most pressing problem. The 2.5 million Irish Catholics in England and Scotland were a major factor in the Labour base in many industrial areas. The Catholic Church had previously tolerated the Labour Party, and denied that it represented true socialism. However, the bishops by 1930 had grown increasingly alarmed at Labour's policies toward Communist Russia, toward birth control and especially toward funding Catholic schools. The Catholic shift against Labour and in favour of the National government played a major role in Labour's losses.

Labour in opposition (1931–1940)

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

, elected in 1931 to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the

1931 general election. The only former Labour cabinet member who had retained his seat, the pacifist

George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spe ...

, accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced another split in 1932 when the

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party and embarked on a long, drawn-out decline.

Lansbury resigned as leader in 1935 after public disagreements over foreign policy. , he is the only Labour leader to stand down from the role without contesting a general election (excluding acting leaders). He was promptly replaced as leader by his deputy,

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, who would lead the party for two decades. The party experienced a revival in the

1935 general election, winning 154 seats and 38% of the popular vote, the highest that Labour had achieved.

As the threat from

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

increased, in the late 1930s the Labour Party gradually abandoned its pacifist stance and came to support re-armament, largely due to the efforts of

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

and

Hugh Dalton, who by 1937 had also persuaded the party to oppose

Neville Chamberlain's policy of

appeasement.

Wartime coalition (1940–1945)

The party returned to government in 1940 as part of the

wartime coalition. When

Neville Chamberlain resigned in the spring of 1940, incoming

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

decided to bring the other main parties into a coalition similar to that of the First World War. Clement Attlee was appointed

Lord Privy Seal and a member of the war cabinet, eventually becoming the United Kingdom's first

Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president ...

.

A number of other senior Labour figures also took up senior positions: the trade union leader

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

, as

Minister of Labour Minister of Labour (in British English) or Labor (in American English) is typically a cabinet-level position with portfolio responsibility for setting national labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, traini ...

, directed Britain's wartime economy and allocation of manpower, the veteran Labour statesman

Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

became

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

,

Hugh Dalton was

Minister of Economic Warfare and later

President of the Board of Trade, while

A. V. Alexander resumed the role he had held in the previous Labour Government as

First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

.

Attlee government (1945–1951)

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, Labour resolved not to repeat the Liberals' error of 1918, promptly withdrawing from government, on trade union insistence, to contest the

1945 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1945.

Africa

* 1945 South-West African legislative election

Asia

* 1945 Indian general election

Australia

* 1945 Fremantle by-election

Europe

* 1945 Albanian parliamentary election

* 1945 Bulgarian ...

in opposition to Churchill's Conservatives. Surprising many observers,

Labour won a landslide victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 159 seats.

Attlee's government proved one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century, enacting

Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

economic policies, presiding over a policy of nationalising major industries and utilities including the

Bank of England, coal mining, the steel industry, electricity, gas, and inland transport (including railways, road haulage and canals). It developed and implemented the "cradle to grave"

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

conceived by the economist

William Beveridge

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge, (5 March 1879 – 16 March 1963) was a British economist and Liberal politician who was a progressive and social reformer who played a central role in designing the British welfare state. His 19 ...

.

To this day, most people in the United Kingdom see the 1948 creation of Britain's

National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

(NHS) under health minister

Aneurin Bevan, which gave publicly funded medical treatment for all, as Labour's proudest achievement.

Attlee's government also began the process of dismantling the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the following year. At a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee and six cabinet ministers, including Foreign Secretary

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

, decided to proceed with the development of Britain's

nuclear weapons programme,

in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour went on to win the

1950 general election, but with a much-reduced majority of five seats. Soon afterwards, defence became a divisive issue within the party, especially defence spending (which reached a peak of 14% of GDP in 1951 during the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

),

straining public finances and forcing savings elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer,

Hugh Gaitskell, introduced charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, causing Bevan, along with

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

(then President of the Board of Trade), to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment on which the NHS had been established.

In the

1951 general election, Labour narrowly lost to Churchill's Conservatives, despite receiving the larger share of the popular vote – its highest ever vote numerically. Most of the changes introduced by the 1945–51 Labour government were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "

post-war consensus

The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in 1945 to the ...

" that lasted until the late 1970s. Food and clothing rationing, however, still in place since the war, were swiftly relaxed, then abandoned from about 1953.

Post-war consensus (1951–1964)

Following the defeat of 1951, the party spent 13 years in opposition. The party suffered an ideological split, between the party's left-wing followers of

Aneurin Bevan (known as

Bevanites) and the right-wing of the party following

Hugh Gaitskell (known as

Gaitskellites) while the postwar economic recovery and the social effects of Attlee's reforms made the public broadly content with the Conservative governments of the time. The ageing Attlee contested his final general election in

1955, which saw Labour lose ground, and he retired shortly after.

Under his replacement, Hugh Gaitskell, Labour appeared more united than before and had been widely expected to win the

1959 general election, but did not. Following this internal party infighting resumed, particularly over the issues of

nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

, Britain's entry into the

European Economic Community (EEC) and

Clause IV

Clause IV is part of the Labour Party Rule Book, which sets out the aims and values of the (UK) Labour Party. The original clause, adopted in 1918, called for common ownership of industry, and proved controversial in later years; Hugh Gaitskell a ...

of the Labour Party Constitution, which was viewed as Labour's commitment to

nationalisation which Gaitskell wanted scrapped. These issues would continue to divide the party for decades to come.

Gaitskell died suddenly in 1963, and this made way for

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

to lead the party.

Wilson government (1964–1970)

A downturn in the economy and a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the

Profumo affair

The Profumo affair was a major scandal in twentieth-century British politics. John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War in Harold Macmillan's Conservative government, had an extramarital affair with 19-year-old model Christine Keeler be ...

) had engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour Party returned to government with a 4-seat majority under Wilson in the

1964 general election but increased its majority to 96 in the

1966 general election.

Wilson's government was responsible for a number of sweeping social and educational reforms under the leadership of

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

Roy Jenkins such as the abolishment of the

death penalty in 1965, the legalisation of

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

and

homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

(initially only for men aged 21 or over, and only in

England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

) in 1967 and the abolition of theatre censorship in 1968. Wilson's government also put heavy emphasis on expanding opportunities through education, and as such,

comprehensive education

Comprehensive may refer to:

* Comprehensive layout, the page layout of a proposed design as initially presented by the designer to a client.

*Comprehensive school, a state school that does not select its intake on the basis of academic achievement ...

was expanded and the

Open University

The Open University (OU) is a British public research university and the largest university in the United Kingdom by number of students. The majority of the OU's undergraduate students are based in the United Kingdom and principally study off- ...

created.

Wilson's first period as Prime Minister coincided with a period of relatively low unemployment and economic prosperity, it was however hindered by significant problems with a large trade deficit which it had inherited from the previous government. The first three years of the government were spent in an ultimately doomed attempt to stave off devaluation of the pound. Labour went on to unexpectedly lose the

1970 general election to the Conservatives under

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

.

Spell in opposition (1970–1974)

After losing the 1970 general election, Labour returned to opposition, but retained Harold Wilson as Leader. Heath's government soon ran into trouble over

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and a dispute with miners in 1973 which led to the "

three-day week". The 1970s proved a difficult time to be in government for both the Conservatives and Labour due to the

1973 oil crisis, which caused high inflation and a global recession.

The Labour Party was returned to power again under Wilson a few days after the

February 1974 general election, forming a minority government with the support of the

Ulster Unionist

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

s. The Conservatives were unable to form a government alone, as they had fewer seats despite receiving more votes numerically. It was the first general election since 1924 in which both main parties had received less than 40% of the popular vote and the first of six successive general elections in which Labour failed to reach 40% of the popular vote. In a bid to gain a majority, a second election was soon called for

October 1974 in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, won a slim majority of three, gaining just 18 seats taking its total to 319.

Majority to minority (1974–1979)

For much of its time in office the Labour government struggled with serious economic problems and a precarious majority in the Commons, while the party's internal dissent over Britain's membership of the

European Economic Community, which Britain had entered under Edward Heath in 1972, led in 1975 to a

national referendum on the issue in which two thirds of the public supported continued membership. Harold Wilson's personal popularity remained reasonably high but he unexpectedly resigned as Prime Minister in 1976 citing health reasons, and was replaced by

James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

. The Wilson and Callaghan governments of the 1970s tried to control

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

(which reached 23.7% in 1975

) by a policy of

wage restraint. This was fairly successful, reducing inflation to 7.4% by 1978.

However it led to increasingly strained relations between the government and the trade unions.

Fear of advances by the nationalist parties, particularly in Scotland, led to the suppression of a

report from Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone that suggested that an independent Scotland would be "chronically in surplus".

By 1977 by-election losses and defections to the breakaway

Scottish Labour Party left Callaghan heading a minority government, forced to do deals with smaller parties in order to govern. An arrangement negotiated in 1977 with

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

leader

David Steel

David Martin Scott Steel, Baron Steel of Aikwood, (born 31 March 1938) is a British politician. Elected as Member of Parliament for Roxburgh, Selkirk, and Peebles, followed by Tweeddale, Ettrick, and Lauderdale, he served as the final leade ...

, known as the

Lib–Lab pact In British politics, a Lib–Lab pact is a working arrangement between the Liberal Democrats (in previous times, the Liberal Party) and the Labour Party.

There have been four such arrangements, and one alleged proposal, at the national level. In ...

, ended after one year. Deals were then forged with various small parties including the

Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Welsh nationalist

Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left to left-wing, Welsh nationalist political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from the United Kingdom.

Plaid wa ...

, prolonging the life of the government.

The nationalist parties, in turn, demanded

devolution to their respective constituent countries in return for their supporting the government. When referendums for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979 the

Welsh devolution referendum saw a large majority vote against, while the

Scottish referendum returned a narrow majority in favour without reaching the required threshold of 40% support. When the Labour government duly refused to push ahead with setting up the proposed Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government: this finally brought the government down as the Conservatives triggered a

vote of confidence in Callaghan's government that was lost by a single vote on 28 March 1979, necessitating a general election.

By 1978, the economy had started to show signs of recovery, with inflation falling to single digits, unemployment falling, and living standards starting to rise during the year. Labour's opinion poll ratings also improved, with most showing the party to be in the lead. Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978 to take advantage of the improving situation. In the event, he decided to gamble that extending the wage restraint policy for another year would allow the economy to be in better shape for a 1979 election. However this proved unpopular with the trade unions, and during the winter of 1978–79 there were widespread strikes among lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers in favour of higher pay-rises that caused significant disruption to everyday life. These events came to be dubbed the "

Winter of Discontent

The Winter of Discontent was the period between November 1978 and February 1979 in the United Kingdom characterised by widespread strikes by private, and later public, sector trade unions demanding pay rises greater than the limits Prime Minis ...

".

These industrial disputes sent the

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

now led by

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

into the lead in the polls, which led to Labour's defeat in the

1979 general election. The Labour vote held up in the election, with the party receiving nearly the same number of votes than in 1974. However, the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, benefiting from both a surge in turnout and votes lost by the ailing Liberals.

Opposition and internal conflict (1979–1994)

After its defeat in the

1979 general election the Labour Party underwent a period of internal rivalry between the left represented by

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

, and the right represented by

Denis Healey. The election of

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

as leader in 1980, and the leftist policies he espoused, such as

unilateral nuclear disarmament, leaving the

European Economic Community and

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, closer governmental influence in the banking system, the creation of a

national minimum wage and a ban on

fox hunting led in 1981 to

four former cabinet ministers from the right of the Labour Party (

Shirley Williams

Shirley Vivian Teresa Brittain Williams, Baroness Williams of Crosby, (' Catlin; 27 July 1930 – 12 April 2021) was a British politician and academic. Originally a Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP), she served in the Labour cabinet from ...

,

Bill Rodgers,

Roy Jenkins and

David Owen) forming the

Social Democratic Party. Benn was only narrowly defeated by Healey in a bitterly fought deputy leadership election in 1981 after the introduction of an electoral college intended to widen the voting franchise to elect the leader and their deputy. By 1982, the

National Executive Committee National Executive Committee is the name of a leadership body in several organizations, mostly political parties:

* National Executive Committee of the African National Congress, in South Africa

* Australian Labor Party National Executive

* Nationa ...

had concluded that the

entryist Militant tendency

, native_name_lang = cy

, logo =

, colorcode =

, leader = collective leadership(''Militant'' editorial board)

, leader1_name = Ted Grant

, leader1_title = Political Secretary

, leader2_name = Pet ...

group were in contravention of the party's constitution.

The Labour Party was defeated heavily in the

1983 general election, winning only 27.6% of the vote, its lowest share since

1918, and receiving only half a million votes more than the

SDP-Liberal Alliance, which leader Michael Foot condemned for "siphoning" Labour support and enabling the Conservatives to greatly increase their majority of parliamentary seats. The party manifesto for this election was termed by critics as "

the longest suicide note in history

"The longest suicide note in history" is an epithet originally used by United Kingdom Labour MP Gerald Kaufman to describe his party's 1983 general election manifesto, which emphasised socialist policies in a more profound manner than previous ...

".

Foot resigned and was replaced as leader by

Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

, with

Roy Hattersley as his deputy. The new leadership progressively dropped unpopular policies. The

miners' strike of 1984–85 over coal mine closures, which divided the NUM as well as the Labour Party, and the

Wapping dispute led to clashes with the left of the party, and negative coverage in most of the press.

The alliances which campaigns such as

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners forged between

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is an ...

(LGBT) and

labour groups, as well as the Labour Party itself, also proved to be an important turning point in the progression of LGBT issues in the UK. At the 1985 Labour Party conference in Bournemouth, a resolution committing the party to support LGBT equality rights passed for the first time due to block voting support from the

National Union of Mineworkers.

Labour improved its performance in

1987

File:1987 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The MS Herald of Free Enterprise capsizes after leaving the Port of Zeebrugge in Belgium, killing 193; Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashes after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airport, ...

, gaining 20 seats and so reducing the Conservative majority from 143 to 102. They were now firmly re-established as the second political party in Britain as the Alliance had once again failed to make a breakthrough with seats. A merger of the SDP and Liberals formed the

Liberal Democrats. Following the 1987 election, the National Executive Committee resumed disciplinary action against members of Militant, who remained in the party, leading to further expulsions of their activists and the two MPs who supported the group. During the 1980s radically socialist members of the party were often described as the "

loony left

The loony left is a pejorative term used to describe those considered to be politically hard left. First recorded as used in 1977, the term was widely used in the United Kingdom in the campaign for the 1987 general election and subsequently both ...

", particularly in the

print media

Mass media refers to a diverse array of media technologies that reach a large audience via mass communication. The technologies through which this communication takes place include a variety of outlets.

Broadcast media transmit informatio ...

.

The print media in the 1980s also began using the pejorative "hard left" to sometimes describe

Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

groups such as the

Militant tendency

, native_name_lang = cy

, logo =

, colorcode =

, leader = collective leadership(''Militant'' editorial board)

, leader1_name = Ted Grant

, leader1_title = Political Secretary

, leader2_name = Pet ...

,

Socialist Organiser and

Socialist Action. In 1988,

Kinnock was challenged by

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

for the party leadership. Based on the percentages, 183 members of parliament supported Kinnock, while Benn was backed by 37. With a clear majority, Kinnock remained leader of the Labour Party.

In November 1990 following a contested leadership election,

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

resigned as leader of the Conservative Party and was succeeded as leader and Prime Minister by

John Major. Most opinion polls had shown Labour comfortably ahead of the Tories for more than a year before Thatcher's resignation, with the fall in Tory support blamed largely on her introduction of the unpopular

poll tax, combined with the fact that the economy was

sliding into recession at the time. The change of leader in the Tory government saw a turnaround in support for the Tories, who regularly topped the opinion polls throughout 1991 although Labour regained the lead more than once.

The "yo-yo" in the opinion polls continued into 1992, though after November 1990 any Labour lead in the polls was rarely sufficient for a majority. Major resisted Kinnock's calls for a general election throughout 1991. Kinnock campaigned on the theme "It's Time for a Change", urging voters to elect a new government after more than a decade of unbroken Conservative rule. However, the Conservatives themselves had undergone a change of leader from Thatcher to Major and replaced the Community Charge.

The

1992 general election was widely tipped to result in a hung parliament or a narrow Labour majority, but in the event, the Conservatives were returned to power, though with a much-reduced majority of 21.

Despite the increased number of seats and votes, it was still an incredibly disappointing result for supporters of the Labour party. For the first time in over 30 years there was serious doubt among the public and the media as to whether Labour could ever return to government.

Kinnock then resigned as leader and was succeeded by

John Smith. Once again the battle erupted between the old guard on the party's left and those identified as "modernisers". The old guard argued that trends showed they were regaining strength under Smith's strong leadership. Meanwhile, the breakaway SDP merged with the Liberal Party. The new

Liberal Democrats seemed to pose a major threat to the Labour base.

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

(the Shadow Home Secretary) had a different vision to traditional Labour politics. Blair, the leader of the "modernising" faction, argued that the long-term trends had to be reversed, arguing that the party was too locked into a base that was shrinking, since it was based on the working-class, on trade unions, and on residents of subsidised council housing. Blair argued that the rapidly growing middle class was largely ignored, as well as more ambitious working-class families. Blair said that they aspired to become middle-class and accepted the Conservative argument that traditional Labour was holding ambitious people back to some extent with higher tax policies. To present a fresh face and new policies to the electorate,

New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

needed more than fresh leaders; it had to jettison outdated policies, argued the modernisers. The first step was procedural, but essential. Calling on the slogan, "

One Member, One Vote" Blair (with some help from Smith) defeated the union element and ended

block voting