Labor federation competition in the United States is a history of the labor movement, considering U.S. labor organizations and federations that have been regional, national, or international in scope, and that have united organizations of disparate groups of workers. Union philosophy and ideology changed from one period to another, conflicting at times. Government actions have controlled, or legislated against particular industrial actions or labor entities, resulting in the diminishing of one labor federation entity or the advance of another.

Labor federation

A 'labor federation' is a group of unions or labor organizations that are in some sense coordinated. The terminology used to identify such organizations grows out of usage, and has sometimes been imprecise; For example, according to

Paul Frederick Brissenden

Paul Frederick Brissenden (September 21, 1885 – November 29, 1974) was an American labor historian, who wrote on various labor issues in the first half of the 20th century. He is perhaps best known for his 1919 work on the Industrial Workers of t ...

nationals are sometimes named internationals, federations are named unions, etc.

The issues that divided labor federations and fostered competition were many and varied. The often conflicting philosophies between the

craft unionists and the

industrial unionists played a role, as did differing ideas about political vs. industrial action; electoral politics; immigration; legislation; union democracy; and, the inclusion of women, black workers, and Asians.

Craft unions tended to organize skilled workers, to the exclusion of the unskilled, further complicating the issue of

class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

among working people. Frequently, the role of government has been significant or decisive in tipping the balance of power between labor federations, or in crushing labor organizations outright. Even personalities of union leaders have sometimes guided the fortunes of labor federations. That may seem inevitable when labor organizations are headed by men like

Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of ...

,

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the history of coal mining, he was the d ...

or

Andy Stern

Andrew L. Stern (born November 22, 1950) is the former president of the Service Employees International Union, and now serves as its President Emeritus.

Stern has been a senior fellow at Georgetown University, Columbia University, and is now a ...

.

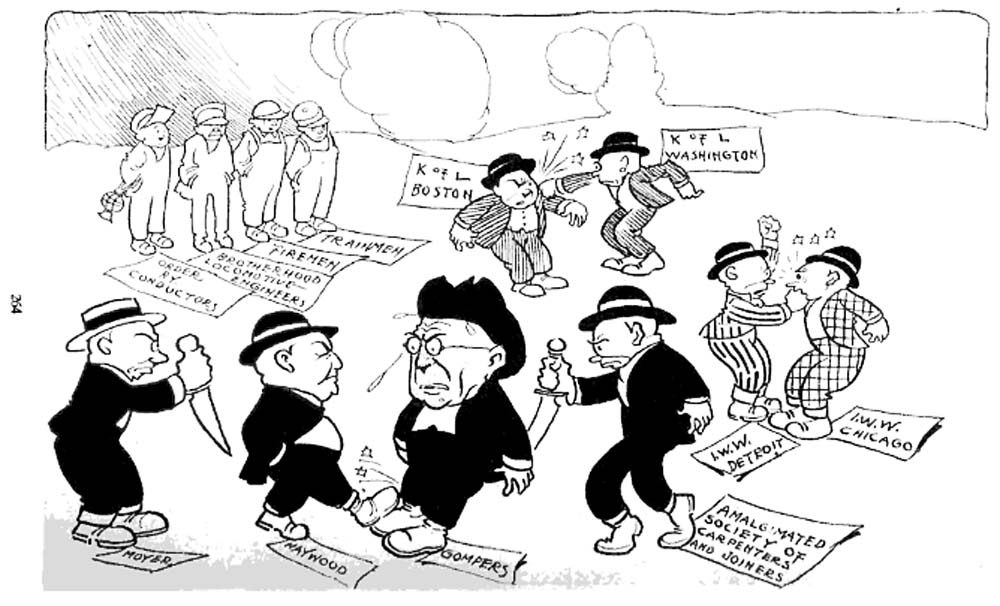

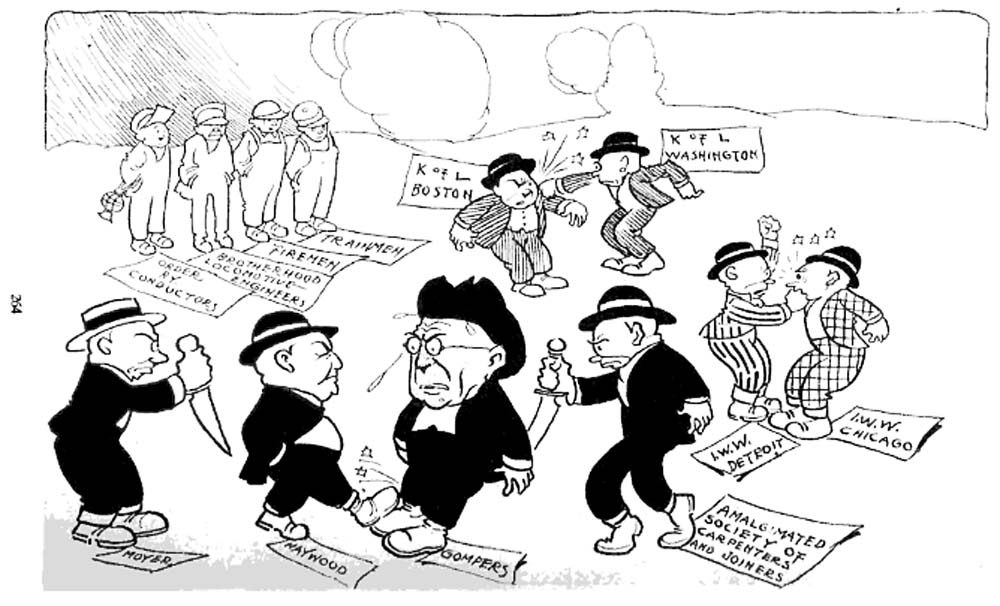

Employer reaction

Employers have rarely failed to notice divisions or disputes among labor unions, and in 1912 ''The American Employer'' contracted for and gleefully reproduced a cartoon depicting the labor scene chaos of the period. Curiously, the Detroit IWW (which had been expelled from the Chicago IWW four years earlier, and would soon change its name to the

Workers' International Industrial Union

The Workers' International Industrial Union (WIIU) was a Revolutionary Industrial Union headquartered in Detroit in 1908 by radical trade unionists closely associated with the Socialist Labor Party of America, headed by Daniel DeLeon. The organiz ...

) editorialized that the cartoon was accurate from an

industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in ...

point of view, stating (according to ''The American Employer''),

[A.S. Van Duzer, editor, The American employer, Volumes 1-2, American Employer Pub. Co., Chamber of Commerce Building, Cleveland, Ohio, 1912, page 391]

"The labor movement of America at the present time could not have eenmore aptly portrayed.

" Moyer is here seen following Haywood Haywood may refer to:

Places Canada

* Haywood, Manitoba

United Kingdom

* Haywood, Herefordshire

* Great Haywood, Staffordshire

* Little Haywood, Staffordshire

United States

* Hayward, California, formerly Haywood

* Haywood, Kentucky

* Haywood, ...

with a knife. Haywood is shown using sabotage on Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

. The Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners

The Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners (ASC&J) was a New Model Trade Union in the 1860s in the United Kingdom, representing carpenters and joiners.

History

The formation of the Society was spurred by the Stonemason's strike, 1859, ...

are also after Sammy, as the Executive Council of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

, revoked their charter. The two factions of the popularly supposed defunct K. of L. nbsp;Knights_of_Labor .html" ;"title="Knights_of_Labor.html" ;"title="nbsp;Knights of Labor">nbsp;Knights of Labor ">Knights_of_Labor.html" ;"title="nbsp;Knights of Labor">nbsp;Knights of Labor are busy soaking each other while the Detroit I. W. W. lands a right swing to the jaw of the Chicago bogus outfit. Standing aloof from the general melee are the various Railway Brotherhoods, aloof not only from the organizations and from the combatants, but aloof from each other, as the various strikes on the railroads have shown."

History

National Labor Union

The first labor federation was the National Labor Union (NLU). The NLU professed that all wealth and property were the products of labor, and that a just monetary system was necessary to ease labor's distress. Working men were receiving too little, and "nonproducing capital" was receiving too much of the wealth produced.

William H. Sylvis

William H. Sylvis (1828–1869) was a pioneer American trade union leader. Sylvis is best remembered as a founder of the Iron Molders' International Union. He also was a founder of the National Labor Union. It was one of the first American union ...

, president of the Iron Molders International Union and, in 1868, president of the NLU, believed that unionization was important, but by itself it could not solve the problem of poverty. He declared,

The cause of all these evils is the WAGES SYSTEM. So long as we continue to work for wages... so long will we be subjected to small pay, poverty, and all of the evils of which we complain.

The federation was anti-

monopolist

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, and advocated

communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

— the pursuit of a more just society established on cooperative principles. The organization also favored shorter work hours, and the establishment of libraries for the express purpose of educating workers.

The 1868 NLU convention also embraced Sylvis's view that a "bank... is a licensed swindle." Sylvis was against

privatizing

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

the

commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

, and also appeared to favor

progressive tax

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases.Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), ''Concepts of Taxation'', Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX The term ''progre ...

ation. The NLU wanted congress to control interest rates, which they thought would help to address the fairness issue.

From the very first convention, certain divergent union tendencies were in conflict. The Workingmen's Union of

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

expressed opposition to a call by the officers of national unions for a "National Convention of Trades." The compromise that avoided an impasse allowed organizations such as eight-hour leagues, composed of individuals supportive of labor but not themselves workers, to send representatives. Thus, due to suspicion of the large, national unions of skilled craftsmen by a general workmen's union, reformist political groups became a part of the National Labor Union. One of the problems with the NLU was the inability to levy an authorized annual dues assessment of twenty-five cents per member, because of "the difficulty in determining who were actually members."

Although the NLU boasted half a million members by 1869, numerous divisions hurt its effectiveness.

[A Pictorial History of American Labor, William Cahn, 1972, page 114.] The question of race was raised, debated, but then evaded in the NLU conventions of 1867 and 1868. By 1869, employers were using

blacks

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in ...

as strike breakers, and

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

workers were sometimes replaced by cheaper black workers. It became apparent that the question of race must be settled. It was recognized that blacks had formed their labor organizations and were actively engaged in

strikes, especially in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

.

[Workers and Utopia, a Study of Ideological Conflict in the American Labor Movement 1865-1900, Gerald N. Grob, 1969, page 23.] Certainly, black workers were capable of unionizing.

It appears that the practical impact of black workers on organizations of white workers finally resolved the question. A resolution was passed by the NLU convention to invite all Negro labor organizations to send delegates to the next convention.

The NLU voted to seat all nine delegates who applied.

[A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 121-123.]

However, the constituent national trade unions refused to admit black workers in spite of the federation's decision. Heated opposition against admitting black workers came from the cigar makers, the typographical union, and the bricklayers. Practical differences between white and black workers complicated the issue. In electoral politics, some NLU factions favored the

Greenback-Labor Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

, or the

Democrats. Black workers maintained allegiance to the

Republican Party, which had helped to abolish slavery.

Black workers had an interest in securing civil rights, jobs, the right to vote, land and homesteads, but little concern about currency reform. For the most part until after the 1880s, black workers remained outside the organized labor movement. In the meantime, excluded by the trade unions and finding little common cause with white workers, they developed a reputation as lower wage workers, and as strikebreakers. Black workers likewise had a less than favorable image of white workers. In

Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, for example, memories of slavery were fresh, and even those whites who had not owned slaves had staffed the local militia, and agitated for employment restrictions on both free blacks and slaves.

This, then, was one of the challenges. Sylvis declared of the black workers,

If we can succeed in convincing these people to make common cause with us...we will have a power...that will shake Wall Street out of its boots... Capital is no respecter of persons and it is...a sheer impossibility to degrade one class of labor without degrading all."

Exhibiting somewhat contradictory tendencies, the NLU advocated support of the

Anti-Coolie Act of 1862

On February 19, 1862, the 37th United States Congress passed ''An Act to Prohibit the "Coolie Trade" by American Citizens in American Vessels.'' The act, which would be called the ''Anti-Coolie Act of 1862'' in short, was passed by the California ...

that was passed by the state of

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, yet approved voluntary emigration of Chinese to the United States. When Chinese workers were used as strike breakers at a

shoe factory in 1870, the NLU came under intense pressure to oppose both "coolie" labor and Chinese immigration.

After a bitter internal argument, the NLU endorsed the women's labor movement, which consisted mostly of protective organizations formed to look after women's rights on the job. At the fourth NLU congress,

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

's credentials were challenged and subsequently rejected on the grounds that she had used the Workingwomen's Protective Union as a strike-breaking organization. The NLU continued to seat delegates from women's organizations, but support for those organizations eroded.

Nonetheless, the NLU was one of the first labor organizations to advocate equal rights and

equal pay for women

Equal pay for equal work is the concept of labour rights that individuals in the same workplace be given equal pay. It is most commonly used in the context of sexual discrimination, in relation to the gender pay gap. Equal pay relates to the ful ...

, even though it remained opposed to women's suffrage. But the national trade unions that were a part of the NLU refused to support equal rights or equal pay for women, and few of them accepted women as members.

For a time a significant faction of the NLU embraced Greenbackism, which aimed to make capital cheaper and, it was hoped, would lead to producers' cooperatives and the abolition of the wage system. Divisions over the greenback issue eventually split the NLU.

Alliances with farmers became problematic because of different monetary interests.

Joseph G. Rayback, author of ''A History of American Labor'', has written:

It is usually concluded that the National Labor Union disappeared because it turned political. The judgment is too simple. The National Labor Union was inherently weak from its origin because its membership held two conflicting philosophies which were never resolved: one was the politically conscious, humanitarian, and reform philosophy inherited from the ighteen-thirties and forties; the other was the "pure and simple" trade-unionist philosophy of the ighteen-fifties...[A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 127-128.]

David Brundage explains ''pure and simple unionism'' as "the view that the labor movement should confine itself to fighting over wages and working conditions and avoid entanglements with those seeking more fundamental social change." Rayback continues,

When reformers urged cooperation with women and Negroes in industry, trade unionists who were inclined to look upon both groups as cheap labor competition became incensed. During the postwar recession trade unionists accepted Greenbackism as a means of establishing cooperatives which would eliminate "wage slavery" and alleviate the "miserable condition of workingmen." After 1870, however, when labor began to share in business recovery, the same trade unionists found Greenbackism "highly amusing," a description which in turn angered the reformers.

By 1870, local and state workingmen's groups favoring political action were gaining strength, and the national trade unions were becoming unhappy with the direction of the NLU. The craft-based trade unions began to disaffiliate. By the time of its demise, the political and reform groups were in control. Rayback concludes,

he National Labor Unionrepresented the transition between the democratic, egalitarian, conscious, humanitarian, and reformist labor movement of the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

period, and the self-centered, wage-conscious, trade-unionist labor movement of the late nineteenth century.

In 1872 the NLU split into separate organizations — the industrial, and the political — a particularly important demarcation that would connote a contentious fault line in future labor organizations.

The trade union organizations that left the NLU had not yet developed "pure and simple unionism" as a philosophical concept. Yet the prospect of political action — particularly for goals that seemed tangential to the perceived needs of union members — caused not only the trade unions, but also the local workingmen's organizations to lose faith in the NLU. To the unions, it seemed, the NLU had lost its balance. Reform at the national level didn't seem to conflict with the quest for a higher standard of living at the local level, so long as some balance between the goals was maintained. But by 1870, it seemed apparent that the NLU was focused more upon reform and political action, than on the goal of representing working people.

But one significant cause of the tension, and the subsequent struggle for power in the NLU was the fact that a significant number of workers hadn't yet comprehended the changed nature of the industrialized system, in which corporations were not only beginning to create their own powerful combinations, they were able to rely upon their close relationship with the state to enforce their requirements upon the labor force. The workers were still thinking in terms of "the simple master-workman relationship" of a previous era. They hadn't yet developed a "mature sense of class consciousness."

Workers were unaware of the importance of establishing not only a strong labor movement, but one with sufficient resources to enable it to meet employers on an equal footing. The NLU had no integral structure of its own; its constituent organizations were autonomous, and the federation could do little more than agitate, pass resolutions, or offer advice. The federation's officers had no salaries, and in 1870, its most successful year, expenses were double receipts. Bereft of resources, focused on political action almost to the exclusion of practical gains for union members, the NLU did not succeed in launching even a single new national trade union.

Yet for its time, the NLU played an important role in labor history.

The founding of the NLU, with its pioneer fight for Negro-labor solidarity, the rights of women, independent political activity, and international solidarity, had been a great step forward despite its weaknesses and despite its defeat.

The problems that the federation confronted were not going away, and some of the ideas promoted by the NLU — accumulated wealth as unpaid labor; the inadequacy of traditional "bread and butter" unionism; the culpability of the wage system in the impoverishment of working people; the desire for a more equitable society; the importance of educating working people about the ways in which they are exploited — these ideas would resonate in other labor organizations in the decades yet to come, at times as a dominant theme, but increasingly as a cry of opposition against the mainstream.

Great Railway Strike, and government response

After the National Labor Union disappeared, the national trade unions attempted to form a new organization through establishment of the Industrial Congress. The effort failed after the panic of 1873 inaugurated a lengthy depression. Membership dropped throughout the union movement, and many trade unions ceased to exist during a period of increasing unemployment, wage reductions, and systematic attacks against labor organizations by employers.

The success or failure of industrial actions have frequently marked turning points in the fortunes of labor organizations. Occurring after a four-year depression, the

railroad strikes of 1877 were,

...spontaneous upheavals of protest and rebellion involving large numbers of dissatisfied workers who were unorganized, without overall leadership and without a program of action... t was

T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is deri ...

the first great class confrontation in America, and a portent of things to come.

The railway workers were supported by farmers, small businessmen, miners, millhands, unemployed workers, black sewermen and stevedores, and others, revealing "how bitterly a portion of the American people hated the railroads..." Strike leaders arrested in

Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

were "un-arrested" by supportive mobs. Several companies of West Virginia militia — relatives and friends of the strikers — were dispatched, but ignored their orders. At

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

's Camden Station, ten strike sympathizers were shot. In

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, thirteen were killed and fifty wounded. In

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, many businessmen who were unhappy about freight rates supported the strike.

[A Pictorial History of American Labor, William Cahn, 1972, page 130.] The

Allegheny County militia was mobilized, and they promptly joined the strikers. The

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

militia arrived a thousand strong

and killed twenty-six strikers. The enraged strike sympathizers forced the military out of the city. Five million dollars worth of railroad property was destroyed. The strike convinced labor that government was hostile to its aims.

[A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 134-136.]

The events of 1877 gave American workers a class consciousness on a national scale,

and led to an increasing polarization of American society.

Many states enacted conspiracy laws directed against labor. State and federal courts revived the concept of malicious conspiracy and applied it to labor organizations. Employers took a stronger stand against union organization, using blacklists and strikebreakers. Harassment of union organizers by local police and officials of local governments, often with the cooperation of local courts, became a common occurrence.[The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor, Daniel R. Fusefeld, 1985, pages 10-11.]

The state militias... were revived... primarily as a strikebreaking force.

Leaders of the strikes of 1877 were blacklisted, tracked by railroad detectives, and hounded from their jobs for years.

Knights of Labor

The National Labor Union and the Industrial Congresses were conceived as top-down organizations launched by national labor leaders. The

Noble Order of the Knights of Labor (KOL) was a movement launched from the ground up.

[Workers and Utopia, a Study of Ideological Conflict in the American Labor Movement 1865-1900, Gerald N. Grob, 1969, page 35.] The KOL was initially formed in 1869 as a secret organization in response to

blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

s and

labor spies

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of an employer/labor organization ...

. At the end of 1873, more than eighty locals had been organized in the Philadelphia area.

The federation was conceived as a mass organization along

industrial lines, uniting both skilled and unskilled workers. The KOL was also

producerist, seeking to unite workers with employers to operate businesses cooperatively. The organization grew slowly until the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which produced a sudden influx of new members.

The Knights of Labor railed against "wealth" in their Preamble, and planned to organize "every department of productive industry." The ultimate goal was establishing "co-operative institutions productive and distributive." The first principles of the order were organization, education, and cooperation. The Knights favored

arbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

over

strikes whenever employers and employees could find common ground. Although the Knights supported the

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

in their constitution, the Knights' General Assembly failed to provide a plan for its implementation. Leadership of Knights considered a shorter workday impractical, and tried unsuccessfully to discourage their members from supporting the eight-hour movement. Because much of the platform of the Knights could be accomplished only through legislative action, the leadership consistently attempted to commit the organization to a political course. The membership was suspicious of the political aims of many of the leaders, who variously advocated Greenbackism, socialism, or land reform. Other issues favored by

Terence V. Powderly

Terence Vincent Powderly (January 22, 1849 – June 24, 1924) was an American labor union leader, politician and attorney, best known as head of the Knights of Labor in the late 1880s. Born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, he was later elected mayor ...

, the Grand Master Workman of the order, were the abolition of

child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

, and the establishment of producers'

cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

s. Organizers and the rank and file were more concerned with using strikes and boycotts to achieve higher wages.

The Knights were organized to favor industrial unions, and officially prohibited the formation of national trade associations based solely upon craft. Organization occurred by district, frequently with multiple crafts assigned to the same local organization. As more tradesmen joined the Knights, the resistance to national trade associations diminished.

The Knights had a leading role in some of the largest strikes of the period from 1869 to 1890. Membership fluctuated dramatically, particularly as a result of failed strikes. In a one-year period after an 1885 Knights of Labor victory over

railroad industrialist Jay Gould, membership in the Knights rose from just over a hundred thousand to more than seven hundred thousand. Large numbers of unskilled and semi-skilled workers who joined the Knights after the victory by railroad workers possessed a strong anti-employer attitude, and were quick to support strikes and boycotts.

[The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor, Daniel R. Fusefeld, 1985, pages 16-17.]

Neglected and downtrodden for decades, their rush to join the Knights was essentially a reaction against long oppression and degradation. Among this faction two elementary passions developed: an attitude of "give no quarter" and a fierce desire to express the power they felt in their alliance with the Knights of Labor—the great unconquered champion of the underdog.

But the leadership of the Knights recalled numerous failures before 1885, and remained timid. Meanwhile, the growth of the Knights was seen as a threat by many of the older craft unions.

Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

In 1881 the

Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada (FOTLU) was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, at Turner Hall in Pittsburgh. It changed its name to the American Federation of Labor (AF ...

(FOOTALU, or FOTALU) was created, initially by a group of disaffected Knights from Indiana. The name of the organization was chosen to exclude political labor organizations but to include both skilled and unskilled workers. But the constitution was written with the intent of handing control to the skilled factions. The legislative program included the goal of legal incorporation of trade unions in order to shield the organizations from attacks using state conspiracy laws. The organization called for total exclusion of Chinese workers, abolition of child labor, and participation of all labor bodies in electoral politics. Although FOOTALU wasn't very successful, it was significant in that the organization "added a right wing to the labor movement of the early

ighteen-ighties.

OOTALUwas not yet a 'pure and simple' trade union organization, but it was a long step in that direction." The FOOTALU dismissed most of the visionary principles advanced by the National Labor Union and the Knights.

When the year 1884 began, labor... was not a united force. On the left were the socialists; the middle road was held by the Knights; the right was shared by F.O.O.T.A.L.U. and the independent trade unions. There was disagreement over methods. Socialists were divided between trade unionists, advocates of political action, and advocates of violence; the Knights fostered the " one big union"; the trades were vacillating between economic and legislative action... hesocialists looked to the ultimate overthrow of the capitalistic order; the Knights looked to the destruction of the wage system and the eventual establishment of a "cooperative" economic system which included both owners and laborers; the trades were becoming more and more conscious of the magical quality of high wages to solve all their troubles.

Philip S. Foner observed that,

The Knights demanded government ownership of the systems of transportation and communication, but the new Federation did not. Nor did the Federation accept the monetary program of the Knights of Labor, indicating that it definitely regarded the industrial capitalist rather than the banker as the chief enemy of the wage-earners, and—unlike the Knights—had pretty nearly rid itself of the belief in financial panaceas... the Federation made no reference to producers or consumers co-operatives, and failed to recommend compulsory arbitration which the Knights supported...

The

Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

grew explosively during the 1880s, and the Knights raided FOOTALU locals and set up rival unions. The Knights of Labor sought to incorporate craft unions into the Knights.

The leadership of the Knights saw the economic strength of craft unions as a way to promote economic gains for all workers. Yet the craft unions recognized that, at least in the short term, a policy of exclusion was more favorable to skilled workers.

Leaders of F.O.O.T.A.L.U., who recognized the stagnation of their own union, looked upon the rise of the order with considerable dismay. Accordingly, the F.O.O.T.A.L.U. convention of October, 1884, determined to make a new bid for leadership by inaugurating a national movement for an eight hour day. The convention invited the Knights to cooperate.

Frank K. Foster of the Typographical Union, affiliated with FOOTALU (which was about to become the American Federation of Labor) proposed a "universal strike" for May 1, 1886. The federation accepted the proposal, while the Knights of Labor leadership expressed no interest. The call demonstrated a rift between the Knights of Labor leadership — which advised their members not to participate, and the Knights of Labor rank and file — who embraced the call.

Then the

Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886 initiated by the Knights of Labor began to falter, and the

Haymarket Riot

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in ...

took place on May 4, 1886. A political backlash occurred against U.S. labor organizations.

Aftermath of Haymarket

The

Haymarket riots sparked a wave of repression throughout the United States. Newspapers whipped public opinion into a frenzy.

In many communities in all parts of the country the local police raided the offices of radical groups and labor unions and arrested their leadership, many of whom were jailed... Printshops for radical publications were wrecked, and offices of the publications themselves were raided.[The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor, Daniel R. Fusefeld, 1985, page 22.]

Fear-gripped state legislatures rushed laws curbing freedom of action of labor organizations onto the statute books. The courts began to convict union members of conspiracy, intimidation, and rioting in wholesale lots. Employers, taking advantage of the situation, instituted widespread anti-union campaigns, with Pinkertons, lockouts, blacklists, and yellow-dog contracts as their chief weapons.

One particularly effective anti-labor technique was "the fostering of bigotry and prejudice."

Black working people were sometimes imported from the South to replace striking Pennsylvania miners. Chinese... ervedas cheap labor, frequently building railroads... Prejudices against Irish and Hungarian immigrants, as well as others, often weakened possibilities of union organization, especially in the coal fields.

Railroad tycoon

Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

may have had such prejudice in mind when he declared that he could "hire one-half of the working class to kill the other half." But in the aftermath of Haymarket, a significant share of the agitation,

...seems to have originated among local business and real-estate interests... These were tactics that were to be perfected over the next thirty years and adopted in less violent form and with legal sanctions by the federal government in 1918-1920.

FOOTALU becomes the American Federation of Labor

The face off between FOOTALU and the Knights of Labor was a struggle between skilled workers in the craft unions, and a larger number of unskilled or semiskilled workers in the KOL. Selig Perlman wrote in 1923 that this was "a clash between the principle of solidarity of labor and that of trade separatism." The craft workers were capable of demanding more from their employers due to their skills, and preferred to fight separately.

[Selig Perlman, A History of Trade Unionism In The United States, Forgotten Books, 1923/2011, pages 114 and 116] John Herman Randall called this the motive of individual advantage overcoming the motive of social idealism.

The Knights of Labor, who were organized by territory rather than by trade, desired that the skilled workers should dedicate their greater leverage to benefit all workers.

This concept would later be referred to as the "new unionism" by

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

and others, who regarded the protection of craft autonomy as the "old unionism", or

business unionism

A business union is a type of trade union that is opposed to class or revolutionary unionism and has the principle that unions should be run like businesses.

Business unions are believed to be of American origin, and the term has been applied in p ...

.

Some FOOTALU leaders called for a meeting to be held on May 18, 1886, ostensibly to solve labor's rivalries. FOOTALU was failing, and its affiliates were in danger of being absorbed into the Knights of Labor. The affiliates themselves were strong, but there was concern that the federation was unable to protect them.

But

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

proposed a new federation, the

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

(AFL). In a complex political environment, Gompers and the craft unionists outmaneuvered the Knights of Labor leadership, gaining considerable support from within the Knights of Labor. The AFL was founded as a continuation of FOOTALU, and as a rival to the now faltering Knights.

The very success of the Knights of Labor intensified the split between unskilled and skilled workers and drove a wedge into the working class. Two national organizations now reflected two different philosophies, one job-consciousness, the other class-consciousness.

If the reader had relied upon early rhetoric and the Preamble alone, they might have been forgiven for mistaking the AFL for that "class-conscious" entity:

A struggle is going on in the nations of the civilized world between the oppressors and the oppressed of all countries, a struggle between capital and labor, which must grow in intensity from year to year and work disastrous results to the toiling millions of all nations if not combined for mutual protection and benefit. This history of the wage-workers of all countries is but the history of constant struggle and misery engendered by ignorance and disunion; whereas the history of the non-producers of all ages proves that a minority, thoroughly organized, may work wonders for good or evil. Conforming to the old adage, 'In union there is strength,' the formation of a Federation embracing every trade and labor organization in North America, a union founded upon a basis as broad as the land we live in, is our only hope. —Preamble to the Constitution of the American Federation of Labor, 1886

The AFL Preamble had been preserved intact from its FOOTALU predecessor. Years later, the Industrial Workers of the World would declare,

he AFL's

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

preamble is contradicted by its constitution. The one proclaims the class struggle, the other denies it.

Adolph Strasser, president of the Cigar Makers' International and a founding leader of the AFL, had testified before the Senate in 1883:

We have no ultimate ends. We are going only from day to day. We are fighting only for immediate objects—objects that can be realized in a few years... we say in our constitution that we are opposed to theorists... we are all practical men...

Curiously, it was the early AFL that voiced support for the Haymarket defendants. Gompers observed,

It was a shocking story of official prejudice... Though the more even balanced rank and file (of the AFL) does not approve of the radical wing, yet they cannot safely abandon the radicals to the vengeance of the common enemies.[A Pictorial History of American Labor, William Cahn, 1972, page 150.]

However, his relationship to the defendants was carefully qualified. Gompers opened his remarks in Chicago,

I have differed all my life with the principles and methods of the condemned.

But the Knights of Labor strenuously fought to distance itself from Haymarket altogether. Terence V. Powderly declared,

Let it be understood by all the world that the Knights of Labor have no affiliation, association, sympathy or respect for the band of cowardly murderers, cut-throats and robbers known as anarchists...

Gompers had educated himself to the precepts of socialism and offered internationalist rhetoric, declaring, "The working people know no country. They are citizens of the world."

[A Pictorial History of American Labor, William Cahn, 1972, page 139.] But Gompers was moving away from radical views, and increasingly embracing conservatism. Labor Historian Melvyn Dubofsky has written,

By 1896 Gompers and the AFL were moving to make their peace with Capitalism and the American system. Although the AFL had once preached the inevitability of class conflict and the need to abolish 'wage slavery', it slowly and almost imperceptibly began to proclaim the virtues of class harmony and the possibilities of a more benevolent Capitalism.[Melvyn Dubofsky,'' 'Big Bill' Haywood'', 1987, page 17.]

Himself an immigrant, the leader of the AFL developed a vociferous hostility to immigrant labor.

Gompers' philosophy about unskilled labor also evolved from one of ambivalence to exclusion.

[Paul Buhle, Taking Care of Business, Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor, 1999, page 41.] Gompers likewise turned away from union democracy:

islieutenant Adolph Strasser voided the election victory of a left-winger to the Cigarmaker's largest local in 1881 and appointed a Gompers (and Strasser) stooge...

The early days of the American Federation of Labor were marked by aggressive thought and action:

It believed in strikes when necessary. It demanded control of wealth, which was "concentrating itself into fewer hands." It believed in "compulsory education laws... prohibition of labor of children under 14 years... sanitation and safety provisions for factories... repeal of all conspiracy laws... a National Bureau of Labor Statistics... protection of American industry against cheap foreign labor... Chinese exclusion..."

Characteristics of the American Federation of Labor

In time, the AFL would redefine its methods and its mission. The federation embraced "pure and simple trade unionism." It pursued the goal of winning "a fair day's wage for a fair day's work," the standard expression of the aspirations of working people as perceived by the federation.

National and international unions within the new federation were given autonomy, up to a point. The ties among the affiliates were more spiritual than material. Yet the federation bureaucracy wielded certain powers. It granted a jurisdiction to each affiliate, generally corresponding to craft, and promised to protect them from encroachment by other affiliates, or by rival unions, with a ruthless jealousy. The AFL had learned that its greatest danger could come from within, as in the event of individual organizations or groups aligning themselves with an outside rival (such as the Knights of Labor). This has resulted in a "passion for regularity" (Selig Perlman's words). Not only would the federation prevent rival unions (i.e., unions over which it could not exercise control) from joining, it would also deal ruthlessly with any subordinate body which lent support to any rival organization.

The governing body of the American Federation of Labor was in essence a weak organization, allowing individual affiliates to make their own decisions on most matters, except in regard to the oversight for the protection and perpetuation of the federation itself. Thus, the federation generally cannot order affiliates to adopt a particular course of action, but it may appeal to them to do so.

The AFL was victorious in its struggle to survive and outlast the Knights of Labor, which was destroyed by a combination of Haymarket backlash, poor leadership, and failed strikes in 1886-87.

[The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor, Daniel R. Fusefeld, 1985, page 23.] But the mass-oriented labor movement hadn't been vanquished; it arose again through the actions of industrial unions in the early 1890s.

Difficult choices in the 1890s

In 1892, four dramatic labor struggles put organized labor at a crossroads. The

Homestead Strike

The Homestead strike, also known as the Homestead steel strike, Homestead massacre, or Battle of Homestead, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security age ...

introduced to the public the significant use of a private army of Pinkertons, and when that failed, more than eight thousand state troops were mobilized to suppress the strike. The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers at Homestead had been,

...a militant, mass-oriented union. A strong thread of class consciousness ran through its policy statements... It was the largest and strongest union in the country in 1892, with over 24,000 members when the great strike at Homestead began.

Yet the organization was crushed, and "six months later the workers were back at work without a union organization." Historian

J. Bernard Hogg, who wrote a dissertation on the Homestead Strike, footnotes that struggle by observing,

The survival of the struggling American Federation of Labor during this period is in part attributable to the caution of its leaders. They made no effort to aid the Homesteaders. Gompers made some fiery speeches but confined himself to that. He knew a lost cause when he saw one and gave up an important branch of the federation rather than risk the whole organization. In this policy he was undoubtedly wise.

Three more defeats caught the attention of the labor movement. An

1892 uprising of hardrock miners in Idaho was brutally put down with federal forces. A strike conducted by railroad switchmen in

Buffalo was broken by militia. And, a series of strikes by coal miners in

Tracy City, Tennessee

Tracy City is a town in Grundy County, Tennessee, United States. Incorporated in 1915, the population was 1,481 at the 2010 census. Named after financier Samuel Franklin Tracy, the city developed out of railroad and mining interests after coal wa ...

, intended to end the use of convict labor in the mines, were also put down by militia. The defeats were shocking to organized labor, and revealed,

...that the corporations... were much more powerful fighting units than was generally realized, capable of defeating the strongest labor organization, and that capital had secured a firm grip on state and local governments and would use the state's power to protect its interests.[A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 197.]

The methods employed to attack unions were improving

[The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor, Daniel R. Fusefeld, 1985, page 27.] with each use:

...the mass media to arouse public opinion, the courts to provide a legal basis for the use of force, strikebreakers to keep operations going and for use as private armies, and jail for the leaders of the workers. All of this was done under the protective umbrella of an appeal to law and order, the sanctity of private property and the United States constitution, and "Americanism."

Labor historian Joseph Rayback observed that for labor to maintain or advance,

Two roads were open: conversion of the A.F.L. into a political movement or the development of industrial unionism.

Many in the AFL favored political action, but Gompers was fearful that passing a program put forward by socialist trade unionists would grant socialists control of the federation. Content to work within capitalism, Gompers opposed grand programs of reform, whether they were based upon political or economic action.

[Anthony Lukas, Big Trouble, 1997, page 210.] He managed, using "some tricky parliamentary procedure," to defeat a proposed turn toward a political program.

Gompers also wasn't about to give up craft unionism for industrial organizing. Yet the AFL didn't control all of organized labor, and organizing industrially had great appeal when unions were under attack.

Industrial unionism in the Pullman Strike

In the aftermath of the railway strike of 1877, there were two very divergent tendencies among railroad workers. The Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen, the Switchmen, and the

Yardmasters did not consider themselves unions, they were mutual aid societies. But men who worked in the depots, the yards, the roundhouses, and the railway machine shops were convinced by events in 1877 that they needed to become more aggressive. The two groups of workers worked peacefully side by side for the most part, until the brotherhoods got involved in a struggle with the Knights of Labor.

The fight reached a climax in 1887-1888 when brotherhood scabs defeated a strike of the Knights against the Reading Railroad, and the Knights' scabs in turn defeated an engineer-fireman strike against the Burlington.

The railroad workers recognized that they needed a movement toward greater unity. But such plans were defeated when the railroads, recognizing the threat of a united workforce, began to treat the brotherhoods so well that they were soon acknowledged as the "élite of the labor world."

[A History of American Labor, Joseph G. Rayback, 1966, page 200.]

The brotherhoods, well satisfied, went their independent ways. In the meantime unionism among the yard, depot, shop, and maintenance workers deteriorated.

But events in 1892 changed everything.

Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

, secretary-treasurer of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, had been considered one of the most conservative of railway labor leaders. But the attacks against labor that year convinced him that the craft unions were too weak when they went up against big business. Debs began campaigning for, and soon had launched, the

American Railway Union (ARU). The ARU followed the organizational structure of the Knights, and was intended as a union for all railway employees. Its success was almost instantaneous. The first strike, against the Great Northern, won easily. While the engineers and conductors stayed with their brotherhoods, the brakemen, firemen, yard and depot workers, shop and car workers flocked to the ARU. By its second convention the ARU had 150,000 members.

The ARU joined the

Pullman Strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

, and demonstrated that industrial unionism was potentially a very powerful way to organize. Within a few hours Pullman traffic was paralyzed from Chicago to the West. The strike then spread to the South and East.

On the eve of the boycott, a statement about the boycott was issued by the chairman of the General Managers Association, a "half-secret combination of twenty-four railroads centering on Chicago,"

"Gentlemen, we can handle the various brotherhoods, but we cannot handle the A. R. U. We have got to wipe it out. We can handle the other leaders, but we cannot handle Debs. We have got to wipe him out too."

The General Managers turned to the federal government, which immediately sent federal troops and United States Marshals to force an end to the strike. Debs was allowed to seek help from the American Federation of Labor. He asked that AFL railroad brotherhood affiliates present the following proposition to the Railway Managers' Association:

...that the strikers return to work at once as a body, upon the condition that they be restored to their former positions, or, in the event of failure, to call a general strike.

The AFL issued a proclamation insisting that all affiliates of the AFL withdraw support for the ARU. The only mention of a general strike was a demand against participation. Gompers would later write that his concern was rebuilding the railway brotherhoods, which could not help but come at the expense of the ARU:

The course pursued by the Federation was the biggest service that could have been performed to maintain the integrity of the Railroad Brotherhoods. Large numbers of their members had left their organization and had joined the American Railway Union. It meant, if not disruption, weakening to a very serious extent.[The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, p. 78 ppbk.]

Writing about the response of the AFL three decades later, Bill Haywood declared,

This was the blade of treachery, with a handle made of a double cross, that was plunged into the breasts of the strikers of the Pullman car shops. It caused the death of the American Railway Union. It sent Eugene V. Debs and his co-workers to prison.

Western Federation of Miners and the United Mine Workers of America

The

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

was born in the crucible of struggle among western hardrock miners. In 1901, miners attending the WFM convention agreed to a proclamation that a "complete revolution of social and economic conditions" was "the only salvation of the working classes." WFM leaders openly called for the abolition of the wage system. By the spring of 1903 the WFM was the most militant labor organization in the country.

In 1902, another significant industrial union, the AFL-affiliated

United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American Labor history of the United States, labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing worke ...

(UMWA), turned away from the significant power and challenge of industrial unionism to embrace collective bargaining and business unionism, during a

strike in the eastern coal fields. John Mitchell began organizing the anthracite region of Pennsylvania in 1898, more than two decades after the

Molly Maguires

The Molly Maguires were an Irish 19th-century secret society active in Ireland, Liverpool and parts of the Eastern United States, best known for their activism among Irish-American and Irish immigrant coal miners in Pennsylvania. After a seri ...

trials had cleared unions out of the region. The miners, by now nearly all immigrants, were being ruthlessly exploited. Mitchell went public with their plight, and gained considerable sympathy.

National Civic Federation and the "labor aristocracy"

Through his appeals to government and the public, Mitchell was helping to build an alliance of conservative union leaders and liberal business men through the

National Civic Federation

The National Civic Federation (NCF) was an American economic organization founded in 1900 which brought together chosen representatives of big business and organized labor, as well as consumer advocates in an attempt to ameliorate labor disputes. I ...

(NCF). Critics of the NCF argued that its goals were to suppress sympathy strikes, and to replace traditional expressions of working class solidarity with binding national trade agreements and arbitration of disputes.

[David Brundage, The Making of Western Labor Radicalism: Denver's Organized Workers, 1878-1905, 1994, page 147.] The WFM unions accused the AFL of creating a

labor aristocracy

Labor aristocracy or labour aristocracy (also aristocracy of labor) has at least four meanings: (1) as a term with Marxist theoretical underpinnings; (2) as a specific type of trade unionism; (3) as a shorthand description by revolutionary indust ...

that divided workers and subverted class unity.

In ''Taking Care of Business'', Paul Buhle writes,

In 1903, United Mine Workers President John Mitchell declared revealingly, "The trade union movement in this country can make progress only by identifying itself with the state." Mitchell provided his own best evidence when he identified the labor movement with himself... e used his position toacquire businesses and to invest in real estate. Busily organizing a far-flung bureaucracy, he quickly made himself an enemy of the union's radicals and a social friend of coal operators. He had adopted, an otherwise sympathetic biographer says, the "culture and attitudes of the employing class." He naturally became a key labor representative to the new National Civic Federation, which sought to promote labor peace (on the terms of the employers, critics claimed) and to make class consciousness and class struggle obsolete.

Mitchell and Gompers were beginning to build an alliance with the Democratic Party. In 1903-04, the WFM would find itself

a target of government repression that was enabled in part by

Pinkerton infiltration. However, the UMWA's turn toward respectability didn't protect it from

similar indignities.

Mitchell and Gompers had also been criticized for failure to support steelworkers during their 1901 strike, a charge that

some laid to coziness with the National Civic Federation, and which resulted in Mitchell's removal as head of the UMWA in 1908. But the Coal Strike of 1902 was a significant victory for the UMWA and for the AFL, resulting in a six-fold increase of AFL membership.

However, longterm benefits for working people from the alliance between conservative union leaders and liberal businessmen proved illusory; employers had become alarmed over the aggressiveness and the success of AFL affiliates. A

nation-wide employers' movement began to seriously threaten unions.

Western Federation of Miners forms the Western Labor Union

Edward Boyce, an Irish-born miner, became the sixth president of the

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

(WFM). In July 1896, he took the WFM into the American Federation of Labor headed by

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

. Almost immediately the two hit a sour note.

Gompers and Boyce went together like warm beer and vinegar. A stumpy Jewish immigrant from the London ghetto, Sam Gompers was shaped by the world of his father, who rolled rich cheroot

The cheroot is a filterless cylindrical cigar with both ends clipped during manufacture. Since cheroots do not taper, they are inexpensive to roll mechanically, and their low cost makes them popular.

The word 'cheroot' probably comes via Portugu ...

s and aromatic panatelas in cigar-making lofts on New York's Lower East Side... the rollers hat young Gompers joinedwere educated men, their craft an ancient skill, their union like that of the medieval guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s, designed as much to protect their hard-won turf from less-skilled workers as to wrest concessions from their employers. Not surprisingly, then, the AFL, which Gompers founded in 1886, was sometimes regarded as a league of petit-bourgeois

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, literally 'small bourgeoisie'; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a French term that refers to a social class composed of semi-autonomous peasants and small-scale merchants whose politico-economic ideological s ...

tradesmen seeking to protect their status from challenges by the industrialized masses... Gompers and his lieutenants, with their silk hats and waistcoats, their lifelong habit of philosophical disputation over glasses of steaming tea, often looked like a band of privileged elitists.

Gompers had settled upon the belief that "pure-and-simple unionism" would serve working people well. Boyce saw things differently. Labor Historian Melvyn Dubofsky observed,

By 1900, most of the unions affiliated with the AFL spoke for members who still possessed valuable and scarce skills, took pride in their crafts, won better treatment for themselves than for the mass of workers and quarrelled with employers over their just share of the bounty of Capitalism rather than with the system itself. The WFM, by contrast, opened itself to all potential members and also to ideas and values in conflict with Capitalism. It accepted any member of a bona fide union without initiation fee upon presentation of a valid union card. It demanded neither a closed shop nor an exclusive employment contract. It sought jobs for all, not merely the organized and skilled few.

Lukas explains,

Ed Boyce's brand of "industrial unionism" grew from a different constituency embedded in different social conditions. Boyce's miners were, for the most part, relatively uneducated men without highly marketable skills, who were often confronted with mine owners and state governments ready to put down labor unrest with strikebreakers, vigilantes, and militias. Such workers saw no advantage to huddling within their traditional crafts; they sought to mobilize all workers across a given industry to confront employers—and governments—with their aggregate clout. With little stake in the status quo, they invested their faith in sweeping political programs to remedy the grim conditions in which they worked and lived.

When the Cloud City Miners Union in

Leadville, Colorado

The City of Leadville is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Statutory city, statutory city that is the county seat, the most populous community, and the only List of municipalities in Colorado, incorporated municipality in Lake County, Colorad ...

, a local of the Western Federation of Miners,

went on strike to try to win back a fifty cents per day pay cut, the mine owners imported strikebreakers. This resulted in a major struggle which a British journalist described:

No surrender; no compromise; no pity. The owners mean to starve the miners to death; the miners mean to blow the owners to atoms.[Anthony Lukas, Big Trouble, 1997, page 211.]

On September 21, militant unionists blew up an oil tank and a wooden mine structure. Four union members were killed, and twenty-seven union members, including Ed Boyce, were jailed. The strike was crushed.

Boyce sought support from the AFL, but got almost nothing beyond words. When Gompers heard a rumor that Boyce might consider leaving the federation, he wrote to the WFM president:

f someone is thinking of leaving the federation

F, or f, is the sixth Letter (alphabet), letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphabet#Let ...

it is most injust ic improper, and destructive... There is nothing in this world which so gladdens the gaze of the enemy in battle as to divide the forces with which it is to contend.

Boyce responded,

I never was so much surprised in my life as I was at the (Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

) convention, when I sat and listened to the delegates from the East talking about conservative action when four million idle men and women are tramps upon the highways... I am not a trades unionist; I am fully convinced that their day of usefulness is past...

After a response from Gompers defending the craft unionists and cautioning against the use of force by the WFM, Boyce was unsatisfied. He wrote,

After mature deliberation, I am fully convinced that no two men in the labor movement differ so widely in opinion as the President of the A.F. of L. and the writer... The trades-union movement has been in operation in our country for a number of years, and through all these years the laboring masses are becoming more dependent. In view of these conditions, do you not think it is time to do something different than to meet in annual convention and fool away time in adopting resolutions, indorsing iclabels and boycotts? ... I am strongly in favor of a Western organization.

After Boyce and Gompers clashed over electoral politics and the use of force, the WFM left the AFL in 1897 while expressing dissatisfaction with the AFL's conservatism. The State Trades and Labor Council of Montana issued its

November 1897 proclamation which assessed the state of affairs between capital and labor, and called for a new western labor federation. In 1898, Boyce organized a rival federation called the

Western Labor Union

The American Labor Union (ALU) was a radical labor organization launched as the Western Labor Union (WLU) in 1898. The organization was established by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in an effort to build a federation of trade unions in th ...

(WLU), which was intended as a class-conscious alternative. The WFM, which played a leadership role in the WLU, professed that the benefits of productivity gains belonged to labor and not to capital. But the WLU also zeroed in on the AFL, criticizing that federation for "dividing the skilled crafts from other workers and for proclaiming the identity of interests of capital and labor." The WLU also issued a manifesto which declared,

Such rights as tradesmen now enjoy, will be extended to the common laborer.[Anthony Lukas, Big Trouble, 1997, page 213.]

An AFL observer wrote that "Boyce's influence with the miners is unquestionably strong. The majority believe him sincerely."

Boyce declared, with words that would be echoed in the Preamble of another organization, one that would be birthed in 1905,

There can be no harmony between organized capitalists and organized labor... Our present wage system is slavery in its worst form. The corporations and trusts have monopolized the necessities of society and the means of life... Let the rallying cry be: Labor, the producer of all wealth, is entitled to all he creates, the overthrow of the whole profit-making system, the extinction of monopolies, equality for all and the land for the people.

The AFL vigorously opposed

dual unionism

Dual unionism is the development of a union or political organization parallel to and within an existing labor union. In some cases, the term may refer to the situation where two unions claim the right to organize the same workers.

Dual unionism i ...

, and the formation of the WLU alarmed Gompers. He sent a delegation to the WLU convention in 1901 "to plead for a reunited labor movement." The AFL had little hope of luring the miners back to the AFL, but there were many other trades joining the WLU. Some labor entities supported the efforts of both organizations but in the West, even the construction trades — which tended to be more conservative — were heavily influenced by the philosophy of the WFM.

[All That Glitters-- Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek, page 77.]

The Victor

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

and Cripple Creek carpenters' locals adopposed Samuel Gompers' reelection as AFL president in 1896 and later advocated that the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, often simply the United Brotherhood of Carpenters (UBC), was formed in 1881 by Peter J. McGuire and Gustav Luebkert. It has become one of the largest trade unions in the United State ...

affiliate with the WLU instead of the AFL.

In keeping with the Gompers philosophy of rewarding friends and punishing enemies, any rival federation to the AFL might quickly feel the wrath, as had the Knights of Labor. While Gompers extended his hand, AFL internationals prohibited affiliation of locals that were also connected to the WLU.

[David Brundage, The Making of Western Labor Radicalism: Denver's Organized Workers, 1878-1905, 1994, page 144.]

The AFL chose to make

Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, location of the headquarters of the WFM, a battleground to contest new unions with the WLU, using the Denver Trades Assembly (DTA) as a focal point in the struggle. In October 1901, the DTA voted narrowly to refuse admittance to any local that was not affiliated with their respective international craft union. Thus, locals affiliated with the WLU, or ''not'' affiliated with the AFL, would be unable to join the local trades assembly.

The DTA chose to punish not only those who found solidarity with a rival to the AFL, but also those whose loyalty to the AFL was judged insufficient.

''Miners Magazine'', the publication of the WFM, accused the DTA of aiding the "increasing virulence" of the "rule or ruin policy of the paid agents" of the AFL. While the AFL leadership clearly encouraged such draconian rules, some Denver craft unions strongly supported the action.

After a few months of bitter conflict in the DTA, the AFL strategy began to fail. The WLU was adding membership, and sentiment in the trades assembly began to shift in the WLU's favor. The fight was led by horseshoer Roady Kenehan and printer

David C. Coates. A two-thirds majority was now necessary to change the affiliation policy. On March 9, 1902, at a contentious meeting, WLU supporters lost the call to affiliate new WLU-connected unions by one vote short of the required (61 of 91 votes) two-thirds majority, failing sixty to thirty-one. But then the WLU supporters changed tactics. They successfully voted to return the DTA charter to the AFL — a vote that required only a majority — and to affiliate the entire DTA to the WLU.

The dissidents — now a minority who favored the AFL — withdrew and formed a separate trades assembly which they called the Incorporated Trades Assembly (A.F. of L.). Disputes over affiliation occurred not only among different union organizations, but also within unions. The factions went to court over which trades assembly represented the legitimate trades assembly. The WLU won the court decision, but the struggle didn't end there.

In early 1902, AFL organizer Pierce began to form rival unions among Denver workers in trades dominated by the WLU. He was especially effective in building organizations among strikebreakers in industries where WLU affiliates were engaged in strikes. Such organizations, accurately labeled "scab unions" by the Western Labor Union, were formed by Pierce at George J. Kindel's mattress factory, the Rocky Mountain Paper Mill, and several other concerns. But such a strategy, while producing results in the short run, could not but hurt the AFL's prestige among Denver's organized workers in the long run. Even Lennon, now national treasurer of the AFL and a Gompers supporter, expressed dismay over Pierce's strategy. He predicted that Pierce's scab unions would have the effect of driving all of Denver's craft unions into the WLU Trades Assembly and called on Gompers to dismiss the organizer.

The Western Labor Union federation changed its name in 1902 as a direct answer to Gompers' actions.

Western Labor Union becomes the American Labor Union

The Western Labor Union became the

American Labor Union

The American Labor Union (ALU) was a radical labor organization launched as the Western Labor Union (WLU) in 1898. The organization was established by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in an effort to build a federation of trade unions in th ...

(ALU) and announced its intention to organize nationwide, hoping to challenge the AFL in the East as well as the West.

The American Labor Union ceased to exist in 1905

when militant labor joined together with labor anarchists and socialist political organizations to create the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The AFL declines to support rival federations

In 1903 the WFM became embroiled in the

Colorado Labor Wars

The Colorado Labor Wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the U.S. state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of m ...