The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francophone world, and it remains one of the most notable examples of a complex

miscarriage of justice and

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

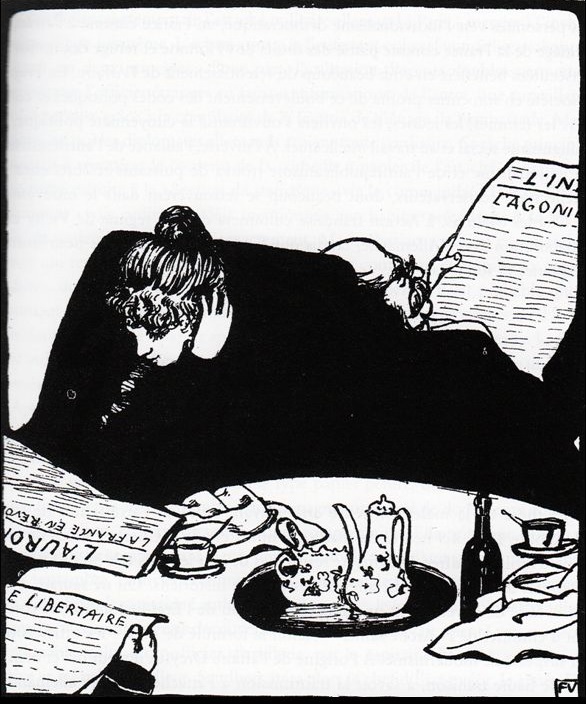

. The role played by the press and public opinion proved influential in the conflict.

The scandal began in December 1894 when Captain

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus ( , also , ; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. ...

was convicted of treason. Dreyfus was a 35-year-old

Alsatian French artillery officer of

Jewish descent

''Zera Yisrael'' ( he, זרע ישראל, , meaning "Seed fIsrael") is a legal category in Halakha, Jewish law that denotes the blood descendants of Jews who, for one reason or another, are not legally of Jewish ethnicity according to religiou ...

. He was falsely convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for communicating French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris, and was imprisoned on

Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953 in the Salvation Islands ...

in

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, where he spent nearly five years.

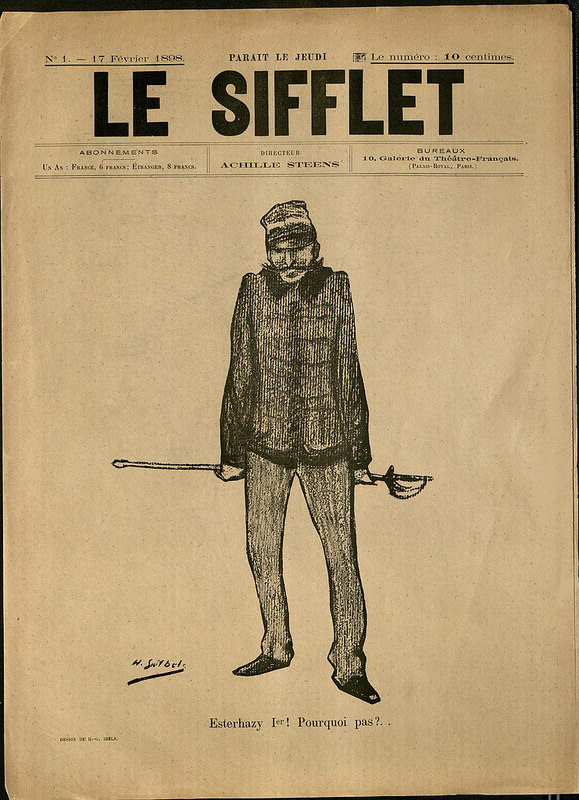

In 1896, evidence came to light—primarily through an investigation made by

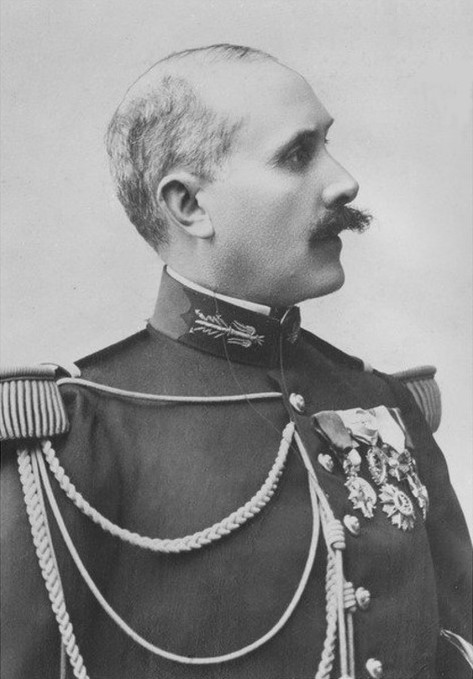

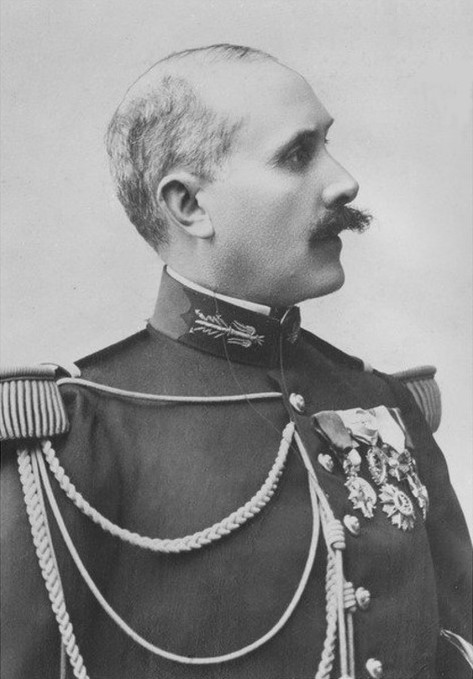

Georges Picquart, head of counter-espionage—which identified the real culprit as a

French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

major named

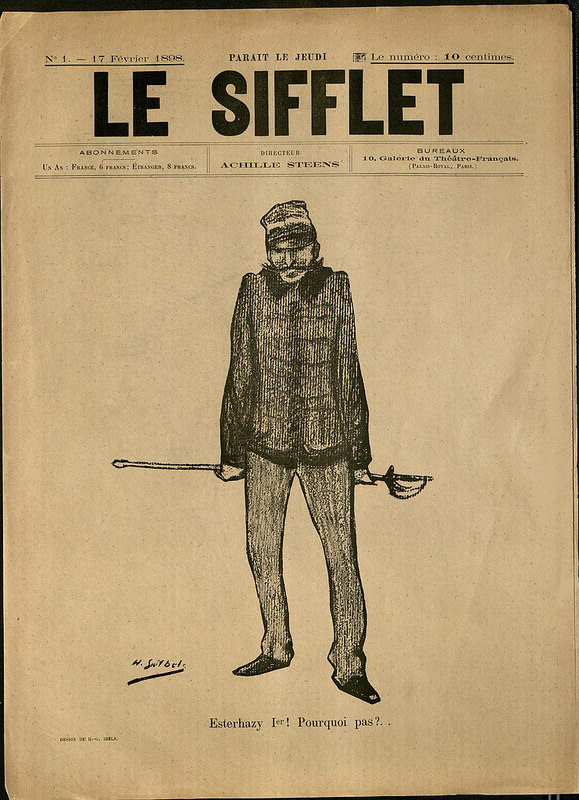

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (16 December 1847 – 21 May 1923) was an officer in the French Army from 1870 to 1898. He gained notoriety as a spy for the German Empire and the actual perpetrator of the act of treason of which C ...

. When high-ranking military officials suppressed the new evidence, a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy after a trial lasting only two days. The Army laid additional charges against Dreyfus, based on forged documents. Subsequently,

Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

's open letter ''

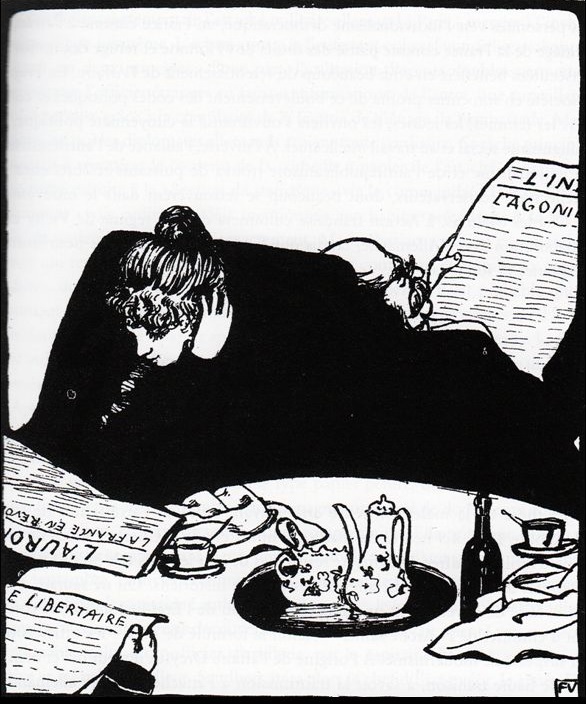

J'Accuse...!'' on the newspaper ''

L'Aurore

''L’Aurore'' (; ) was a literary, liberal, and socialist newspaper published in Paris, France, from 1897 to 1914. Its most famous headline was Émile Zola's '' J'Accuse...!'' leading into his article on the Dreyfus Affair.

The newspaper was ...

'' stoked a growing movement of support for Dreyfus, putting pressure on the government to reopen the case.

In 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France for another trial. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus (now called "Dreyfusards"), such as

Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

,

Anatole France,

Charles Péguy,

Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré ( S: stress final syllable ; 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as "The ...

, and

Georges Clemenceau, and those who condemned him (the anti-Dreyfusards), such as

Édouard Drumont, the director and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper ''

La Libre Parole''. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence, but Dreyfus was pardoned and released. In 1906, Dreyfus was

exonerated and reinstated as a major in the French Army. He served during the whole of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, ending his service with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He died in 1935.

The affair from 1894 to 1906 divided France into pro-republican, anticlerical Dreyfusards and pro-Army, mostly Catholic "anti-Dreyfusards". It embittered French politics and encouraged radicalisation.

Summary

At the end of 1894,

French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

Captain

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus ( , also , ; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. ...

, a graduate of the

École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

, a Jew of Alsatian origin, was accused of handing secret documents to the Imperial German military. After a closed trial, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was deported to

Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953 in the Salvation Islands ...

. At that time, the opinion of the French political class was unanimously unfavourable towards Dreyfus.

The Dreyfus family, particularly his brother

Mathieu

Mathieu is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* André Mathieu (1929–1968), Canadian pianist and composer

* Anselme Mathieu (1828–1895), French Provençal poet

* Claude-Louis Mathieu (1783–187 ...

, remained convinced of his innocence and worked with journalist

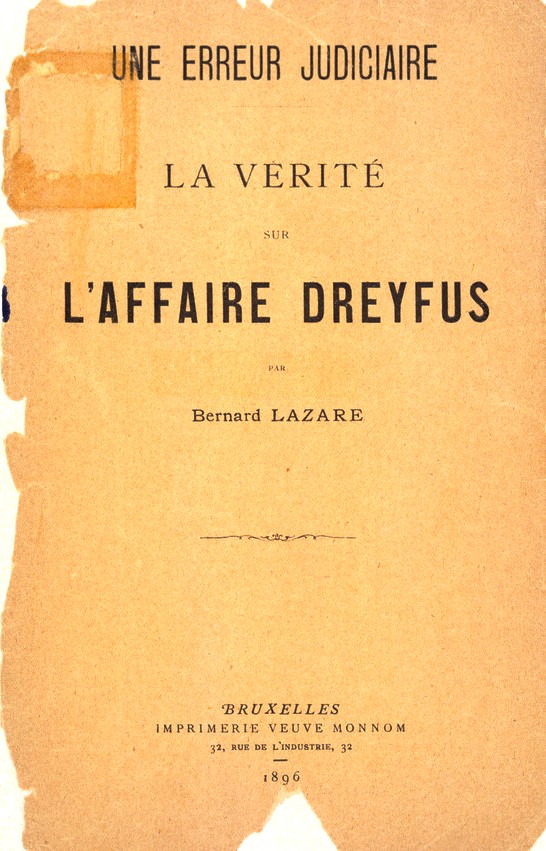

Bernard Lazare to prove it. In March 1896, Colonel

Georges Picquart, head of counter-espionage, found evidence that the real traitor was Major

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (16 December 1847 – 21 May 1923) was an officer in the French Army from 1870 to 1898. He gained notoriety as a spy for the German Empire and the actual perpetrator of the act of treason of which C ...

. The

General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

refused to reconsider its judgment and transferred Picquart to North Africa.

In July 1897, Dreyfus's family contacted the President of the Senate

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner to draw attention to the tenuousness of the evidence against Dreyfus. Scheurer-Kestner reported three months later that he was convinced Dreyfus was innocent, and persuaded

Georges Clemenceau, a newspaper reporter and former member of the

Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

. In the same month,

Mathieu Dreyfus

Mathieu Dreyfus (1857–1930) was an Alsace, Alsatian Jewish industrialist and the older brother of Alfred Dreyfus, a French people, French military officer falsely convicted of treason in what became known as the Dreyfus affair. Mathieu was one ...

made a complaint about Esterhazy to the Ministry of War. In January 1898 two events raised the case to national prominence: Esterhazy was acquitted of treason charges (subsequently shaving his moustache and fleeing France), and

Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

published his ''

J'accuse...!'', a Dreyfusard declaration that rallied many intellectuals to Dreyfus's cause. France became increasingly divided over the case, and the issue continued to be hotly debated until the end of the century. Antisemitic riots erupted in more than twenty French cities and there were several deaths in

Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

.

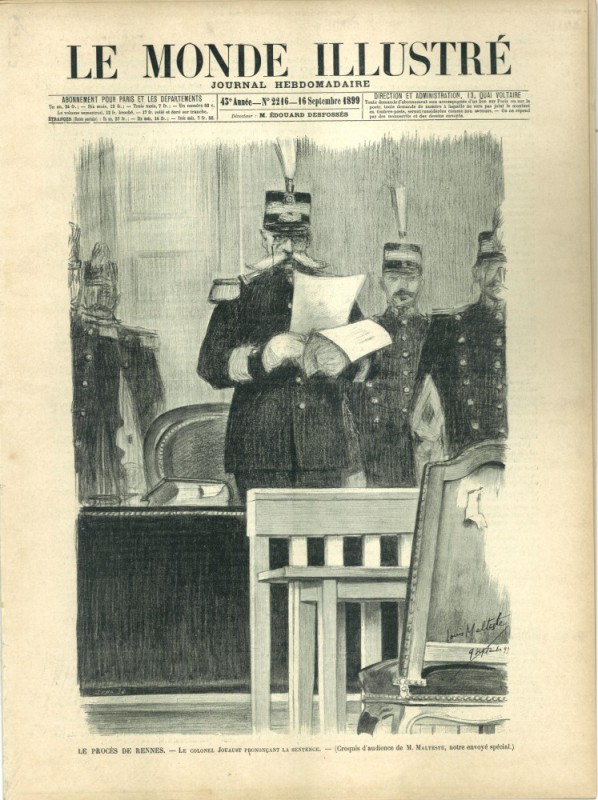

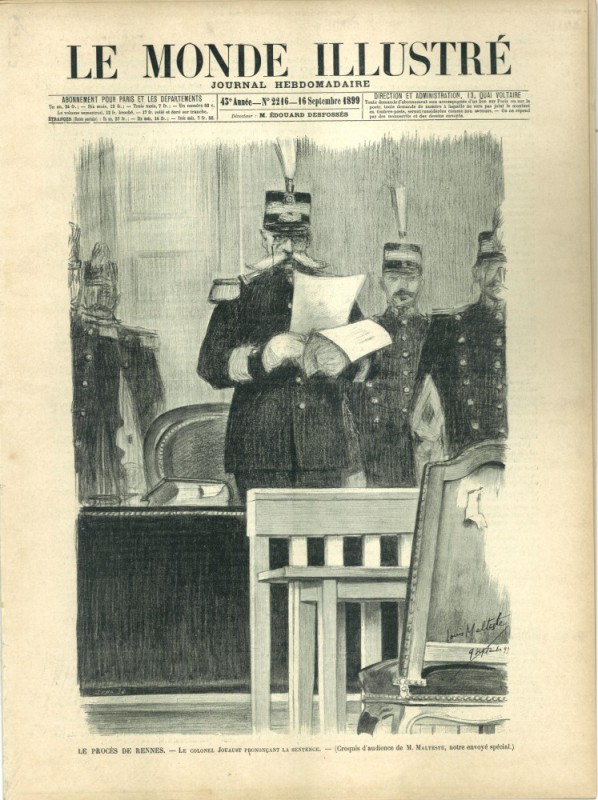

Despite covert attempts by the army to quash the case, the initial conviction was annulled by the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

after a thorough investigation. A new court-martial was held at

Rennes

Rennes (; br, Roazhon ; Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in northwestern France at the confluence of the Ille and the Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the region of Brittany, as well as the Ille-et-Vilaine department ...

in 1899. Dreyfus was convicted again and sentenced to ten years of hard labour, though the sentence was commuted due to extenuating circumstances. Dreyfus accepted the presidential pardon granted by President

Émile Loubet. In 1906 his innocence was officially established by an irrevocable judgement of the Supreme Court. Dreyfus was reinstated in the army with the rank of Major and participated in the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He died in 1935.

The implications of this case were numerous and affected all aspects of French public life. It was regarded as a vindication of the Third Republic (and became a founding myth), but it led to a renewal of

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

in the military. It slowed the reform of French

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

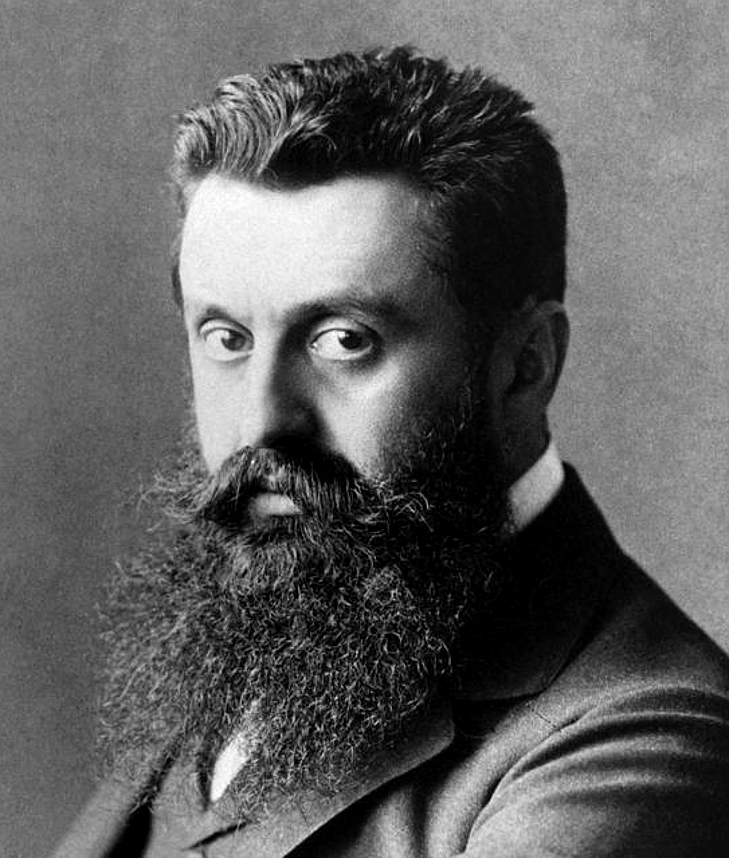

and republican integration of Catholics. It was during The Affair that the term, ''intellectual'', was coined in France. The Affair engendered numerous antisemitic demonstrations, which in turn affected sentiment within the Jewish communities of Central and Western Europe. This persuaded

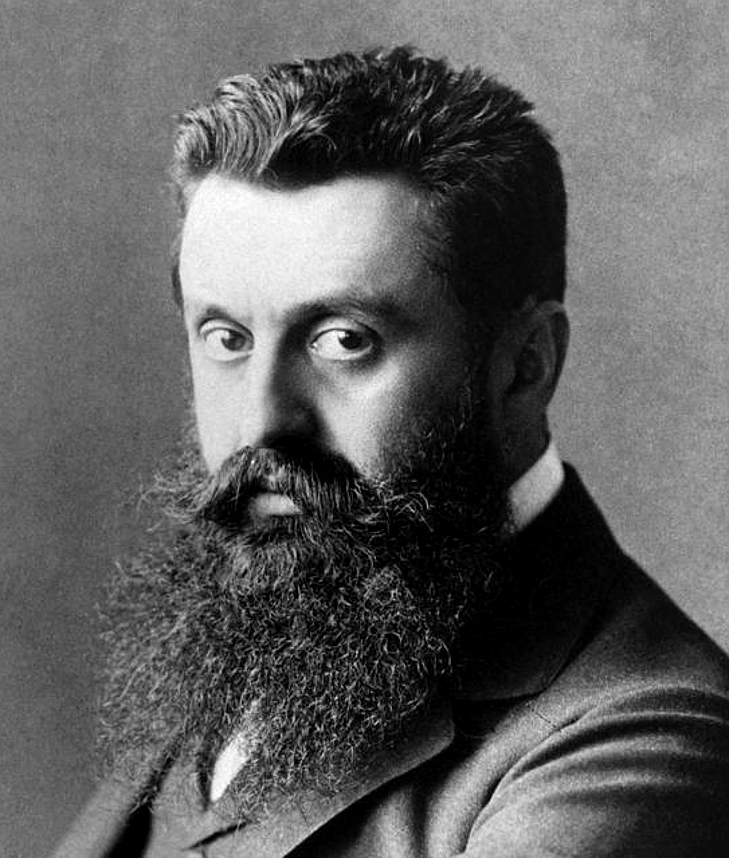

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

, one of the founding fathers of

Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

, that the Jews must leave Europe and establish their own state.

Contexts

Political

In 1894, the

Third Republic was twenty-four years old. Although the

16 May Crisis in 1877 had crippled the political influence of both the

Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

and

Orléanist royalists, its ministries continued to be short-lived as the country lurched from crisis to crisis: three years immediately preceding the Dreyfus Affair were the

near-coup of Georges Boulanger in 1889, the

Panama scandals

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cost ...

in 1892, and the

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

threat (reduced by the "

villainous laws" of July 1894). The

elections of 1893 were focused on the "social question" and resulted in a Republican victory (just under half the seats) against the conservative right and the reinforcement of the Radicals (about 150 seats) and Socialists (about 50 seats).

The opposition of the Radicals and Socialists resulted in a centrist government with policies oriented towards economic protectionism, a certain indifference to social issues, a willingness to break international isolation, the Russian alliance, and development of the colonial empire. These centrist policies resulted in cabinet instability, with some Republican members of the government sometimes aligning with the radicals and some

Orléanists aligning with the

Legitimists

The Legitimists (french: Légitimistes) are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They re ...

in five successive governments from 1893 to 1896. This instability coincided with an equally unstable presidency: President

Sadi Carnot was assassinated on 24 June 1894, his moderate successor

Jean Casimir-Perier resigned on 15 January 1895 and was replaced by

Félix Faure

Félix François Faure (; 30 January 1841 – 16 February 1899) was the President of France from 1895 until his death in 1899. A native of Paris, he worked as a tanner in his younger years. Faure became a member of the Chamber of Deputies for Se ...

.

Following the failure of the radical government of

Léon Bourgeois

Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois (; 21 May 185129 September 1925) was a French statesman. His ideas influenced the Radical Party regarding a wide range of issues. He promoted progressive taxation such as progressive income taxes and social insuran ...

in 1896, the president appointed

Jules Méline

Félix Jules Méline (; 20 May 183821 December 1925) was a French statesman, Prime Minister of France from 1896 to 1898.

Biography

Méline was born at Remiremont. Having taken up law as his profession, he was chosen a deputy in 1872, and in 187 ...

as prime minister. His government faced the opposition of the left and of some Republicans (including the Progressive Union) and made sure to keep the support of the right. He sought to appease religious, social, and economic tensions and conducted a fairly conservative policy. He succeeded in improving stability, and it was under this stable government that the Dreyfus affair occurred.

Military

The Dreyfus affair occurred in the context of the annexation of

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

and

Moselle

The Moselle ( , ; german: Mosel ; lb, Musel ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a bank (geography), left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it jo ...

by the Germans, an event that fed the most extreme nationalism. The

traumatic defeat in 1870 seemed far away, but a vengeful spirit remained. Many participants in the Dreyfus affair were Alsatian.

[Dreyfus was from ]Mulhouse

Mulhouse (; Alsatian language, Alsatian: or , ; ; meaning ''Mill (grinding), mill house'') is a city of the Haut-Rhin Departments of France, department, in the Grand Est Regions of France, region, eastern France, close to the France–Switzerl ...

, as were Sandherr and Scheurer-Kestner, Picquart was from Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

, Zurlinden was from Colmar

Colmar (, ; Alsatian: ' ; German during 1871–1918 and 1940–1945: ') is a city and commune in the Haut-Rhin department and Grand Est region of north-eastern France. The third-largest commune in Alsace (after Strasbourg and Mulhouse), it is ...

.

The military required considerable resources to prepare for the next conflict, and it was in this spirit that the

Franco-Russian Alliance, which some saw as "against nature",

[ Auguste Scheurer-Kestner in a speech in the Senate.] of 27 August 1892 was signed. The army had recovered from the defeat but many of its officers were aristocrats and monarchists. Cult of the flag and contempt for the parliamentary republic prevailed in the army. The Republic celebrated its army; the army ignored the Republic.

Over the previous ten years the army had experienced a significant shift in its twofold aim to democratize and modernize. The graduates of the

École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

competed effectively with officers from the main career path of

Saint-Cyr, which caused strife, bitterness, and jealousy among junior officers expecting promotions. The period was also marked by an

arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more states to have superior armed forces; a competition concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and t ...

that primarily affected artillery. There were improvements in heavy artillery (guns of 120 mm and 155 mm,

Models 1890 Baquet, new hydropneumatic brakes), but also and especially the development of the ultra-secret

75mm gun.

The operation of military counterintelligence, alias the "Statistics Section" (SR), should be noted. Spying as a tool for secret war was a novelty as an organised activity in the late 19th century. The Statistics Section was created in 1871 but consisted of only a handful of officers and civilians. Its head in 1894 was Lieutenant-Colonel

Jean Sandherr, a graduate of

Saint-Cyr, an Alsatian from

Mulhouse

Mulhouse (; Alsatian language, Alsatian: or , ; ; meaning ''Mill (grinding), mill house'') is a city of the Haut-Rhin Departments of France, department, in the Grand Est Regions of France, region, eastern France, close to the France–Switzerl ...

, and a convinced anti-Semite. Its military mission was clear: to retrieve information about potential enemies of France and to feed them false information. The Statistics Section was supported by the "Secret Affairs" of the Quai d'Orsay at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was headed by a young diplomat,

Maurice Paléologue. The arms race created an acute atmosphere of intrigue in French

counter-espionage from 1890. One of the missions of the section was to spy on the German Embassy at Rue de Lille in Paris to thwart any attempt to transmit important information to the Germans. This was especially critical since several cases of

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

had already hit the headlines of newspapers, which were fond of sensationalism. Thus in 1890, the archivist Boutonnet was convicted for selling plans of shells that used

melinite.

The German military attaché in Paris in 1894 was Count

Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen

Maximilian Friedrich Wilhelm August Leopold von Schwartzkoppen (24 February 1850 – 8 January 1917) was a Prussian military officer. After serving as Imperial German military attaché in Paris, Schwartzkoppen was later given the rank of Genera ...

, who developed a policy of infiltration which appears to have been effective. In the 1880s Schwartzkoppen had begun an affair with an Italian military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Count Alessandro Panizzardi. While neither had anything to do with Dreyfus, their intimate and erotic correspondence (e.g. "Don't exhaust yourself with too much buggery."), which was obtained by the authorities, lent an air of truth to other documents that were forged by prosecutors to lend retroactive credibility to Dreyfus's conviction as a spy. Some of these forgeries even referenced the real affair between the two officers; in one, Alessandro supposedly informed his lover that if "Dreyfus is brought in for questioning", they must both claim that they "never had any dealings with that Jew. ... Clearly, no one can ever know what happened with him." The letters, real and fake, provided a convenient excuse for placing the entire Dreyfus dossier under seal, given that exposure of the liaison would have 'dishonoured' Germany and Italy's military and compromised diplomatic relations. As homosexuality was, like Judaism, then often perceived as a sign of national degeneration, recent historians have suggested that combining them to inflate the scandal may have shaped the prosecution strategy.

Since early 1894, the Statistics Section had investigated traffic in master plans for Nice and the Meuse conducted by an officer whom the Germans and Italians nicknamed Dubois.

[This was the purpose of the letter intercepted by the French SR called the "Scoundrel D ...", used in the "secret file" to convict Dreyfus] This is what led to the origins of the Dreyfus affair.

Social

The social context was marked by the rise of nationalism and antisemitism. The growth of antisemitism, virulent since the publication of ''Jewish France'' by

Édouard Drumont in 1886 (150,000 copies in the first year), went hand in hand with the rise of

clericalism. Tensions were high in all strata of society, fueled by an influential press, which was virtually free to write and disseminate any information even if offensive or defamatory. Legal risks were limited if the target was a private person.

Antisemitism did not spare the military, which practised hidden discrimination with the "cote d'amour" (a subjective assessment of personal acceptability) system of irrational grading, encountered by Dreyfus in his application to the Bourges School. However, while prejudices of this nature undoubtedly existed within the confines of the General Staff, the French Army as a whole was relatively open to individual talent. At the time of the Dreyfus affair there were an estimated 300 Jewish officers in the army (about 3 per cent of the total), of whom ten were generals.

The popularity of the duel using sword or small pistol, sometimes causing death, bore witness to the tensions of the period. When a series of press articles in ''

La Libre Parole'' accused Jewish officers of "betraying their birth", the officers challenged the editors. Captain Crémieu-Foa, a Jewish Alsatian graduated from the Ecole Polytechnique, fought unsuccessfully against Drumont

[Count Esterházy was, ironically, one of the witnesses for Crémieu-Foa][Frederick Vie]

''Anti-Semitism in the Army: the Coblentz Affair at Fontainebleau''.

and against M. de Lamase, who was the author of the articles. Captain Mayer, another Jewish officer, was killed by the

Marquis de Morès, a friend of Drumont, in another duel.

Hatred of Jews was now public and violent, driven by a firebrand (Drumont) who demonized the Jewish presence in France. Jews in metropolitan France in 1895 numbered about 80,000 (40,000 in Paris alone), who were highly integrated into society; an additional 45,000 Jews lived in

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. The launch of ''La Libre Parole'' with a circulation estimated at 200,000 copies in 1892, allowed Drumont to expand his audience to a popular readership already enticed by the

boulangiste

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

adventure in the past. The antisemitism circulated by ''La Libre Parole'', as well as by ''L'Éclair'', ''

Le Petit Journal'', ''La Patrie'', ''L'Intransigeant'' and ''

La Croix La Croix primarily refers to:

* ''La Croix'' (newspaper), a French Catholic newspaper

* La Croix Sparkling Water, a beverage distributed by the National Beverage Corporation

La Croix or Lacroix may also refer to:

Places

* Lacroix-Barrez, a muni ...

'', drew on antisemitic roots in certain Catholic circles.

Publications remarking on the Dreyfus Affair often reinforced antisemitic sentiments, language and imagery. The ''

Musée des Horreurs'' was a collection of anti-Dreyfus posters illustrated by Victor Lenepveu during the Dreyfus Affair. Lenepveu caricatured "prominent Jews, Dreyfus supporters, and Republican statesman." ''No. 35 Amnistie populaire'' depicts the corpse of Dreyfus himself as it dangles from a noose. Large noses, money, and Lenepveu's general tendency to illustrate subjects with bodies of animals likely contributed to the dissemination of antisemitism in French popular culture.

Origins of the case and the trial of 1894

The beginning: acts of espionage

The origin of the Dreyfus affair, although fully clarified since the 1960s, has aroused much controversy for nearly a century. The intentions remain unclear. Many eminent historians express different hypotheses about the affair but all arrive at the same conclusion: Dreyfus was innocent of any crime or offence.

Discovery of the "bordereau"

The staff of the Military Intelligence Service (SR) worked around the clock to spy on the German Embassy in Paris. They had managed to get a French housekeeper named "Madame Bastian" hired to work in the building and spy on the Germans. In September 1894, she found a torn-up note which she handed over to her employers at the Military Intelligence Service. This note later became known as "the bordereau".

[The French word ''bordereau'' means simply a note or slip of paper and can be applied to any note. In French, many documents in the case were called bordereaux; however, in this translation the term bordereau is used only for this note.] This piece of paper, torn into six large pieces, unsigned and undated, was addressed to the German military attaché stationed at the German Embassy,

Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen

Maximilian Friedrich Wilhelm August Leopold von Schwartzkoppen (24 February 1850 – 8 January 1917) was a Prussian military officer. After serving as Imperial German military attaché in Paris, Schwartzkoppen was later given the rank of Genera ...

. It stated that confidential French military documents regarding the newly developed "hydraulic brake of 120, and the way this gun has worked" were about to be sent to a foreign power.

The search for the author of the bordereau

This catch seemed of sufficient importance for the head of the "Statistical Section", the Mulhousian

Jean Sandherr, to inform the Minister of War,

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Auguste Mercier. In fact the SR suspected that there had been leaks since the beginning of 1894 and had been trying to find the perpetrator. The minister had been harshly attacked in the press for his actions, which were deemed incompetent, and appears to have sought an opportunity to enhance his image. He immediately initiated two secret investigations, one administrative and one judicial. To find the culprit, using simple though crude reasoning,

[Birnbaum, ''The Dreyfus Affair'', p. 40. ] the circle of the search was arbitrarily restricted to suspects posted to, or former employees of, the General Staff – necessarily a trainee artillery

[On the indication of Captain Matton, the only artillery officer in the Statistics Section. Three of the documents transmitted concerned short- and long-range artillery.] officer.

[The documents could come from 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th offices – only a trainee appeared able to offer such a variety of documents as they passed from one office to another to complete their training. This was the reasoning of Lieutenant-Colonel d'Aboville, which proved fallacious.]

The ideal culprit was identified: Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a graduate of the

École polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

and an artillery officer, of the Jewish faith and of Alsatian origin, coming from the republican meritocracy. At the beginning of the case the emphasis was rather on the Alsatian origins of Dreyfus than on his religion. These origins were not, however, exceptional because these officers were favoured by France for their knowledge of the German language and culture. There was also antisemitism in the offices of the General Staff, and it fast became central to the affair by filling in the credibility gaps in the preliminary enquiry.

In particular, Dreyfus was at that time the only Jewish officer to be recently passed by the General Staff.

In fact, the reputation of Dreyfus as a cold and withdrawn or even haughty character, as well as his "curiosity", worked strongly against him. These traits of character, some false, others natural, made the charges plausible by turning the most ordinary acts of everyday life in the ministry into proof of espionage. From the beginning a biased and one-sided multiplication of errors led the State to a false position. This was present throughout the affair, where irrationality prevailed over the positivism in vogue in that period:

Expertise in writing

To condemn Dreyfus, the writing on the bordereau had to be compared to that of the Captain. There was nobody competent to analyse the writing on the General Staff. Then

Major du Paty de Clam entered the scene: an eccentric man who prided himself on being an expert in

graphology

Graphology is the analysis of handwriting with attempt to determine someone's personality traits. No scientific evidence exists to support graphology, and it is generally considered a pseudoscience or scientifically questionable practice. Howe ...

. On being shown some letters by Dreyfus and the bordereau on 5 October, du Paty concluded immediately who had written the two writings. After a day of additional work he provided a report that, despite some differences, the similarities were sufficient to warrant an investigation. Dreyfus was therefore "the probable author" of the bordereau in the eyes of the General Staff.

General Mercier believed he had the guilty party, but he exaggerated the value of the affair, which took on the status of an affair of state during the week preceding the arrest of Dreyfus. The Minister did consult and inform all the authorities of the State, yet despite prudent counsel

[From General Saussier, Governor of Paris for example.] and courageous objections expressed by

Gabriel Hanotaux

Albert Auguste Gabriel Hanotaux, known as Gabriel Hanotaux (19 November 1853 – 11 April 1944) was a French statesman and historian.

Biography

He was born at Beaurevoir in the ''département'' of Aisne. He studied history at the École des C ...

in the Council of Ministers he decided to pursue it. Du Paty de Clam was appointed

Judicial Police Officer to lead an official investigation.

Meanwhile, several parallel sources of information were opening up, some on the personality of Dreyfus, others to ensure the truth of the identity of the author of the bordereau. The expert

[Expert in writing from the Bank of France: his honest caution was vilified in the indictment of Major Ormescheville.] Gobert was not convinced and found many differences. He even wrote that "the nature of the writing on the bordereau excludes disguised handwriting". Disappointed, Mercier then called in

Alphonse Bertillon

Alphonse Bertillon (; 22 April 1853 – 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical me ...

, the inventor of forensic

anthropometry

Anthropometry () refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthropology and in various atte ...

but no handwriting expert. He was initially no more positive than Gobert but he did not exclude the possibility of its being the writing of Dreyfus. Later, under pressure from the military, he argued that Dreyfus had autocopied it and developed his theory of "autoforgery".

The arrest

On 13 October 1894, without any tangible evidence and with an empty file, General Mercier summoned Captain Dreyfus for a general inspection in "bourgeois clothing", i.e. in civilian clothes. The purpose of the General Staff was to obtain the perfect proof under French law: a

confession. That confession was to be obtained by surprise – by dictating a letter based on the bordereau to reveal his guilt.

On the morning of 15 October 1894, Captain Dreyfus underwent this ordeal but admitted nothing. Du Paty even tried to suggest suicide by placing a revolver in front of Dreyfus, but he refused to take his life, saying he "wanted to live to establish his innocence". The hopes of the military were crushed. Nevertheless Du Paty de Clam still arrested the captain, accused him of conspiring with the enemy, and told him that he would be brought before a court-martial. Dreyfus was imprisoned at the

Cherche-Midi prison

The Cherche-Midi prison was a French military prison located in Paris, France. It housed military prisoners between 1851 and 1947.

Construction on the prison began in 1847, when the former convent of the Daughters of the Good Shepherd was demolish ...

in

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

.

The enquiry and the first military court

Mrs. Dreyfus was informed of the arrest the same day by a police raid to search their apartment. She was terrorized by Du Paty, who ordered her to keep the arrest of her husband secret and even said, "One word, one single word and it will be a European war!" Totally illegally, Dreyfus was placed in solitary confinement in prison, where Du Paty interrogated him day and night in order to obtain a confession, which failed. The captain was morally supported by the first Dreyfusard, Major Forzinetti, commandant of the military prisons of Paris.

On 29 October 1894, the affair was revealed in an article in ''

La Libre Parole'', the antisemitic newspaper owned by

Édouard Drumont. This marked the beginning of a very brutal press campaign until the trial. This event put the affair in the field of antisemitism where it remained until its conclusion.

On 1 November 1894, Alfred's brother, Mathieu Dreyfus, became aware of the arrest after being called urgently to Paris. He became the architect of the arduous fight for the liberation of his brother. Without hesitation, he began looking for a lawyer, and retained the distinguished criminal lawyer

Edgar Demange.

The enquiry

On 3 November 1894, General Saussier, the

Military governor of Paris, reluctantly gave the order for an enquiry. He had the power to stop the process but did not, perhaps because of an exaggerated confidence in military justice. Major Besson d'Ormescheville, the recorder for the Military Court, wrote an indictment in which "moral elements" of the charge (which gossiped about the habits of Dreyfus and his alleged attendance at "gambling circles", his knowledge of German,

[" ..he speaks several languages, especially German which he knows thoroughly."] and his "remarkable memory") were developed more extensively than the "material elements",

[These are treated in the single penultimate paragraph in one sentence: "The material elements consist of the incriminating letter including review by the majority of experts as well as by us and by the witnesses who have seen it until now except for those who wilfully see differences, showing a complete similarity with the authentic writing of Captain Dreyfus".] which are rarely seen in the charge:

"This is a proof of guilt because Dreyfus made everything disappear".

The complete lack of neutrality of the indictment led to Émile Zola calling it a "monument of bias".

After the news broke on Dreyfus' arrest, many journalists flocked to the story and flooded the story with speculations and accusations. The renowned journalist and antisemitic agitator

Edouard Drumont wrote in his publication on November 3, 1894, "What a terrible lesson, this disgraceful treason of the Jew Dreyfus."

On 4 December 1894, Dreyfus was referred to the first Military Court with this dossier. The secrecy was lifted and Demange could access the file for the first time. After reading it the lawyer had absolute confidence, as he saw the emptiness of the prosecution's case. The prosecution rested completely on the writing on a single piece of paper, the bordereau, on which experts disagreed, and on vague indirect testimonies.

The trial: "Closed Court or War!"

During the two months before the trial, the press went wild. ''

La Libre Parole'', ''L'Autorité'', ''

Le Journal

''Le Journal'' (The Journal) was a Paris daily newspaper published from 1892 to 1944 in a small, four-page format.

Background

It was founded and edited by Fernand Arthur Pierre Xau until 1899. It was bought and managed by the family of Henri ...

'', and ''

Le Temps

''Le Temps'' (literally "The Time") is a Swiss French-language daily newspaper published in Berliner format in Geneva by Le Temps SA. It is the sole nationwide French-language non-specialised daily newspaper of Switzerland. Since 2021, it has b ...

'' described the supposed life of Dreyfus through lies and bad fiction.

This was also an opportunity for extreme headlines from ''La Libre Parole'' and ''

La Croix La Croix primarily refers to:

* ''La Croix'' (newspaper), a French Catholic newspaper

* La Croix Sparkling Water, a beverage distributed by the National Beverage Corporation

La Croix or Lacroix may also refer to:

Places

* Lacroix-Barrez, a muni ...

'' to justify their previous campaigns against the presence of Jews in the army on the theme "You have been told!" This long delay above all enabled the General Staff to prepare public opinion and to put indirect pressure on the judges. On 8 November 1894, General Mercier declared Dreyfus guilty in an interview with ''

Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of reco ...

''. He repeated himself on 29 November 1894 in an article by

Arthur Meyer in ''

Le Gaulois

''Le Gaulois'' () was a French daily newspaper, founded in 1868 by Edmond Tarbé and Henry de Pène. After a printing stoppage, it was revived by Arthur Meyer in 1882 with notable collaborators Paul Bourget, Alfred Grévin, Abel Hermant, and E ...

'', which in fact condemned the indictment against Dreyfus and asked, "How much freedom will the military court have to judge the defendant?"

The jousting of the columnists took place within a broader debate about the issue of a closed court. For Ranc and Cassagnac, who represented the majority of the press, the closed court was a low manoeuvre to enable the acquittal of Dreyfus, "because the minister is a coward". The proof was "that he ''grovels'' before the Prussians" by agreeing to publish the denials of the German ambassador in Paris. In other newspapers, such as ''L'Éclair'' on 13 December 1894: "the closed court is necessary to avoid a ''

casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one b ...

''"; while for Judet in ''

Le Petit Journal'' of 18 December: "the closed court is our impregnable refuge against Germany"; or in ''La Croix'' the same day: it must be "the most absolute closed court".

The trial opened on 19 December 1894 at one o'clock and a closed court was immediately pronounced.

[Trial takes place solely in the presence of judges, the accused, and his defence.] This closed court was not legally consistent since

Major Picquart and Prefect

Louis Lépine were present at certain proceedings in violation of the law. The closed court allowed the military to still not disclose the emptiness of their evidence to the public and to stifle debate. As expected, the emptiness of their case appeared clearly during the hearings. Detailed discussions on the bordereau showed that Captain Dreyfus could not be the author. At the same time the accused himself protested his innocence and defended himself point by point with energy and logic. Moreover, his statements were supported by a dozen defence witnesses. Finally, the absence of motive for the crime was a serious thorn in the prosecution case. Dreyfus was indeed a very patriotic officer highly rated by his superiors, very rich and with no tangible reason to betray France. The fact of Dreyfus's Jewishness was used only by the right-wing press and was not presented in court.

Alphonse Bertillon

Alphonse Bertillon (; 22 April 1853 – 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical me ...

, who was not an expert in handwriting, was presented as a scholar of the first importance. He advanced the theory of "autoforgery" during the trial and accused Dreyfus of imitating his own handwriting, explaining the differences in writing by using extracts of writing from his brother Matthieu and his wife Lucie. This theory, although later regarded as bizarre and astonishing, seems to have had some effect on the judges. In addition, Major

Hubert-Joseph Henry made a theatrical statement in open court.

[Deputy Head of SR and discoverer of the bordereau.] He argued that leaks betraying the General Staff had been suspected to exist since February 1894 and that "a respectable person" accused Captain Dreyfus. He swore on oath that the traitor was Dreyfus, pointing to the crucifix hanging on the wall of the court. Dreyfus was apoplectic with rage and demanded to be confronted with his anonymous accuser, which was rejected by the General Staff. The incident had an undeniable effect on the court, which was composed of seven officers who were both judges and jury. However, the outcome of the trial remained uncertain. The conviction of the judges had been shaken by the firm and logical answers of the accused. The judges took leave to deliberate, but the General Staff still had a card in hand to tip the balance decisively against Dreyfus.

Transmission of a secret dossier to the judges

Military witnesses at the trial alerted high command about the risk of acquittal. For this eventuality the Statistics Section had prepared a file containing, in principle, four "absolute" proofs of the guilt of Captain Dreyfus accompanied by an explanatory note. The contents of this secret file remained uncertain until 2013, when they were released by the French Ministry of Defence. Recent research indicates the existence of numbering which suggests the presence of a dozen documents. Among these letters were some of an erotic homosexual nature (the Davignon letter among others) raising the question of the tainted methods of the Statistics Section and the objective of their choice of documents.

The secret file was illegally submitted at the beginning of the deliberations by the President of the Military Court, Colonel Émilien Maurel, by order of the Minister of War, General Mercier. Later at the Rennes trial of 1899, General Mercier explained the nature of the prohibited disclosure of the documents submitted in the courtroom.

[This was obviously wrong. The motive of Mercier was much to condemn Dreyfus unbeknownst to the defence. V. indictment.] This file contained, in addition to letters without much interest, some of which were falsified, a piece known as the "Scoundrel D ...".

It was a letter from the German military attaché, Max von Schwarzkoppen, to the Italian military attaché, Alessandro Panizzardi, intercepted by the SR. The letter was supposed to accuse Dreyfus definitively since, according to his accusers, it was signed with the initial of his name. In reality, the Statistics Section knew that the letter could not be attributed to Dreyfus and if it was, it was with criminal intent. Colonel Maurel confirmed in the second Dreyfus trial that the secret documents were not used to win the support of the judges of the Military Court. He contradicted himself, however, by saying that he read only one document, "which was enough".

Conviction, degradation, and deportation

On 22 December 1894, after several hours of deliberation, the verdict was reached. Seven judges unanimously convicted Alfred Dreyfus of collusion with a foreign power, to the maximum penalty under section 76 of the Criminal Code: ''permanent exile in a walled fortification'' (

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correc ...

), the cancellation of his army rank and

military degradation

Cashiering (or degradation ceremony), generally within military forces, is a ritual dismissal of an individual from some position of responsibility for a breach of discipline.

Etymology

From the Flemish (to dismiss from service; to discard ...

. Dreyfus was not

sentenced to death, as it had been abolished for

political crime

In criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the ...

s

since 1848.

For the authorities, the press and the public, doubts had been dispelled by the trial and his guilt was certain. Right and left regretted the abolition of the death penalty for such a crime. Antisemitism peaked in the press and occurred in areas so far spared.

Jean Jaurès regretted the lightness of the sentence in an address to the House and wrote, "A soldier has been sentenced to death and executed for throwing a button in the face of his corporal. So why leave this miserable traitor alive?"

Clemenceau in ''Justice'' made a similar comment.

On 5 January 1895, the ceremony of degradation took place in the Morlan Court of the

Military School

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally provides education in a military environment, the exact definition depending on the country concerned. ...

in Paris. While the drums rolled, Dreyfus was accompanied by four artillery officers, who brought him before an officer of the state who read the judgment. A Republican Guard adjutant tore off his badges, thin strips of gold, his stripes, cuffs and sleeves of his jacket. As he was paraded throughout the streets, the crowd chanted "Death to Judas, death to the Jew." Witnesses report the dignity of Dreyfus, who continued to maintain his innocence while raising his arms: "Innocent, Innocent! Vive la France! Long live the Army". The Adjutant broke his sword on his knee and then the condemned Dreyfus marched at a slow pace in front of his former companions. An event known as "the legend of the confession" took place before the degradation. In the van that brought him to the military school, Dreyfus is said to have confided his treachery to Captain Lebrun-Renault. It appears that this was merely self-promotion by the captain of the Republican Guard, and that in reality Dreyfus had made no admission. Due to the affair's being related to national security, the prisoner was then held in solitary confinement in a cell awaiting transfer. On 17 January 1895, he was transferred to the prison on

Île de Ré where he was held for over a month. He had the right to see his wife twice a week in a long room, each of them at one end, with the director of the prison in the middle.

At the last minute, at the initiative of General Mercier, a law was passed on 9 February 1895, restoring the

Îles du Salut

The Salvation Islands (french: Îles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcanic origin about off the coast of Fre ...

in

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, as a place of fortified deportation so that Dreyfus was not sent to Ducos,

New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

. Indeed, during the deportation of Adjutant Lucien Châtelain, sentenced for conspiring with the enemy in 1888, the facilities did not provide the required conditions of confinement and detention conditions were considered too soft. On 21 February 1895, Dreyfus embarked on the ship Ville de Saint-Nazaire. The next day the ship sailed for

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

.

On 12 March 1895, after a difficult voyage of fifteen days, the ship anchored off the Îles du Salut. Dreyfus stayed one month in prison on

Île Royale

The Salvation Islands (french: Îles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcano, volcanic origin about off the coa ...

and was transferred to

Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''Île du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953 in the Salvation Islands ...

on 14 April 1895. Apart from his guards, he was the only inhabitant of the island and he stayed in a stone hut . Haunted by the risk of escape, the commandant of the prison sentenced him to a hellish life, even though living conditions were already very painful.

[The temperature reached 45 °C, he was underfed or fed contaminated food and hardly had any treatment for his many tropical diseases.] Dreyfus became sick and shaken by fevers that got worse every year.

Dreyfus was allowed to write on paper numbered and signed. He underwent censorship by the commandant even when he received mail from his wife Lucie, whereby they encouraged each other. On 6 September 1896, the conditions of life for Dreyfus worsened again; he was chained ''double looped'', forcing him to stay in bed motionless with his ankles shackled. This measure was the result of false information of his escape revealed by a British newspaper. For two long months, Dreyfus was plunged into deep despair, convinced that his life would end on this remote island.

The truth emerges (1895–1897)

The Dreyfus family exposes the affair and takes action

Mathieu Dreyfus

Mathieu Dreyfus (1857–1930) was an Alsace, Alsatian Jewish industrialist and the older brother of Alfred Dreyfus, a French people, French military officer falsely convicted of treason in what became known as the Dreyfus affair. Mathieu was one ...

, the elder brother of Alfred, was convinced of his innocence. He was the chief architect of the rehabilitation of his brother and spent his time, energy and fortune to gather an increasingly powerful movement for a retrial in December 1894, despite the difficulties of the task:

Mathieu tried all paths, even the most fantastic. Thanks to Dr. Gibert, a friend of President

Félix Faure

Félix François Faure (; 30 January 1841 – 16 February 1899) was the President of France from 1895 until his death in 1899. A native of Paris, he worked as a tanner in his younger years. Faure became a member of the Chamber of Deputies for Se ...

, he met at

Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

a woman who spoke for the first time under

hypnosis of a "secret file".

[Bredin, ''The Affair'', p. 117. ] This fact was confirmed by the President of the Republic to Dr. Gibert in a private conversation.

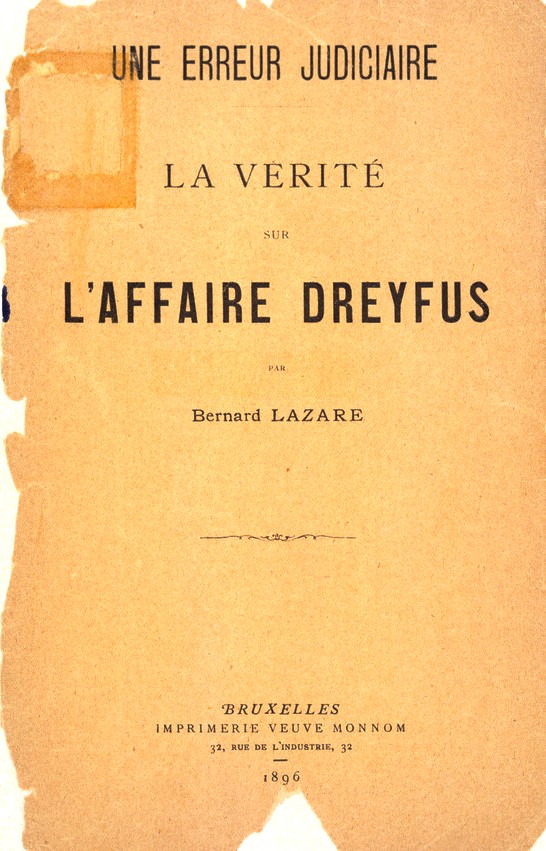

Little by little, despite threats of arrest for complicity, machinations and entrapment by the military, he managed to convince various moderates. Thus the

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

journalist

Bernard Lazare looked into the proceedings. In 1896, Lazare published the first Dreyfusard booklet in

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

. This publication had little influence on the political and intellectual world, but it contained so much detail that the General Staff suspected that Picquart, the new head of SR, was responsible.

The campaign for the review, relayed little by little into the leftist anti-military press, triggered a return of a violent yet vague antisemitism. France was overwhelmingly anti-Dreyfusard; Major Henry from the Statistics Section in turn was aware of the thinness of the prosecution case. At the request of his superiors,

General Boisdeffre, Chief of the General Staff and

Major-General Gonse, he was charged with the task of enlarging the file to prevent any attempt at a review. Unable to find any evidence, he decided to build some after the fact.

The discovery of the real culprit: Picquart "going to the enemy"

Major

Georges Picquart was assigned to be head of the staff of the Military Intelligence Service (SR) in July 1895, following the illness of Colonel Sandherr. In March 1896, Picquart, who had followed the Dreyfus Affair from the outset, now required to receive the documents stolen from the German Embassy directly without any intermediary.

[It was he who had been the captain on the morning of 15 October 1894 at the scene of the dictation.] He discovered a document called the "petit bleu": a telegram that was never sent, written by von Schwarzkoppen and intercepted at the German Embassy at the beginning of March 1896. It was addressed to a French officer,

Major Walsin-Esterhazy, 27 rue de la Bienfaisance – Paris. In another letter in black pencil, von Schwarzkoppen revealed the same clandestine relationship with Esterhazy.

On seeing letters from Esterhazy, Picquart realized with amazement that his writing was exactly the same as that on the "bordereau", which had been used to incriminate Dreyfus. He procured the "secret file" given to the judges in 1894 and was astonished by the lack of evidence against Dreyfus, and became convinced of his innocence. Moved by his discovery, Picquart diligently conducted an enquiry in secret without the consent of his superiors. The enquiry demonstrated that Esterhazy had knowledge of the elements described by the "bordereau" and that he was in contact with the German Embassy. It was established that the officer sold the Germans many secret documents, whose value was quite low.

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was a former member of French counterespionage where he had served after the war of 1870. He had worked in the same office as Major

Henry from 1877 to 1880. A man with a personality disorder, a sulphurous reputation and crippled by debt, he was considered by Picquart to be a traitor driven by monetary reasons to betray his country. Picquart communicated the results of his investigation to the General Staff, which opposed him under "the authority of the principle of ''

res judicata

''Res judicata'' (RJ) or ''res iudicata'', also known as claim preclusion, is the Latin term for "a matter decided" and refers to either of two concepts in both civil law and common law legal systems: a case in which there has been a final judgm ...

''". After this, everything was done to oust him from his position, with the help of his own deputy, Major Henry. It was primarily the upper echelons of the Army that did not want to admit that Dreyfus's conviction could be a grave miscarriage of justice. For Mercier, then

Zurlinden and the General Staff, what was done was done and should never be returned to. They found it convenient to separate the Dreyfus and Esterhazy affairs.

The denunciation of Esterhazy and the progress of Dreyfusism

The nationalist press launched a violent campaign against the burgeoning Dreyfusards. In counter-attack, the General Staff discovered and revealed the information hitherto ignored in the "secret file". Doubt began to surface, and figures in the artistic and political spheres asked questions.

[ Cassagnac, though antisemitic, published an article entitled ''Doubt'' in mid-September 1896.] Picquart tried to convince his seniors to react in favour of Dreyfus, but the General Staff seemed deaf. An investigation was started against him, he was monitored when he was in the east, then transferred to

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

"in the interest of the service".

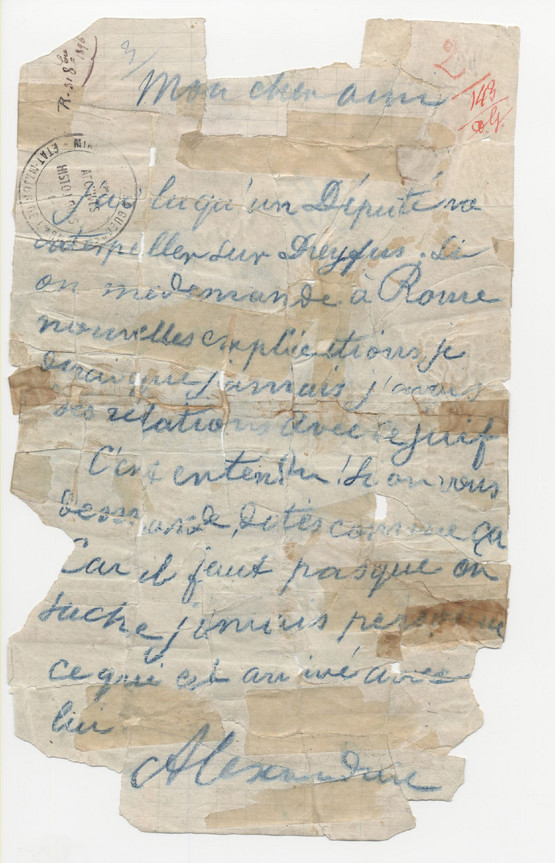

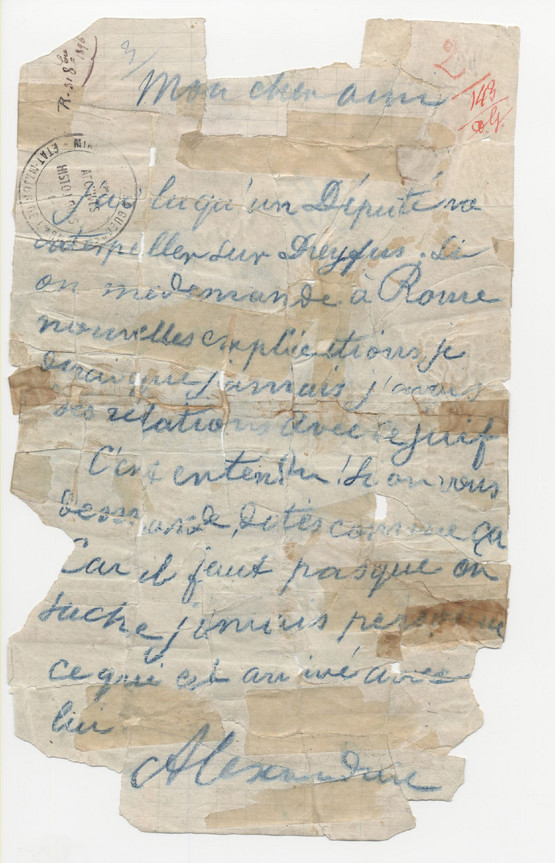

At this moment Major Henry chose to take action. On 1 November 1896, he created a false document, subsequently called the "faux Henry"

enry forgery[Otherwise known as "faux patriotique" atriotic forgeryby the anti-Dreyfusards.] keeping the header and signature

[Alexandrine, Panizzardi's usual signature.] of an ordinary letter from Panizzardi, and wrote the central text himself:

This was a rather crude forgery. Generals Gonse and Boisdeffre, however, without asking questions, brought the letter to their minister,

General Billot. The doubts of the General Staff regarding the innocence of Dreyfus flew out the window.

[Bredin, ''The Affair'', p. 168. ] With this discovery the General Staff decided to protect Esterhazy and persecute Colonel Picquart, "who did not understand anything".

Picquart, who knew nothing of the "faux Henry", quickly felt isolated from his fellow soldiers. Major Henry accused Picquart of embezzlement and sent him a letter full of innuendo. He protested in writing and returned to Paris.

Picquart confided in his friend, lawyer Louis Leblois, who promised secrecy. Leblois, however, spoke to the vice president of the Senate, the Alsatian

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner (born in

Mulhouse

Mulhouse (; Alsatian language, Alsatian: or , ; ; meaning ''Mill (grinding), mill house'') is a city of the Haut-Rhin Departments of France, department, in the Grand Est Regions of France, region, eastern France, close to the France–Switzerl ...

, like Dreyfus), who was in turn infected by doubts. Without citing Picquart, the senator revealed the affair to the highest people in the country. The General Staff, however, still suspected Picquart of causing leaks. This was the beginning of the Picquart affair, a new conspiracy by the General Staff against an officer.

Major Henry, although deputy to Picquart, was jealous and fostered his own malicious operation to compromise his superior. He engaged in various malpractices (making a letter and designating it as an instrument of a "Jewish syndicate", wanting to help Dreyfus to escape, rigging the "petit bleu" to create a belief that Picquart erased the name of the real recipient, drafting a letter naming Dreyfus in full).

Parallel to the investigations of Picquart, the defenders of Dreyfus were informed in November 1897 that the identity of the writer of the "bordereau" was Esterhazy. Mathieu Dreyfus had a reproduction of the bordereau published by ''

Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of reco ...

''. A banker, Castro, formally identified the writing as that of Esterhazy, who was his debtor, and told Mathieu. On 11 November 1897, the two paths of investigation met during a meeting between Scheurer-Kestner and Mathieu Dreyfus. The latter finally received confirmation that Esterhazy was the author of the note. Based on this, on 15 November 1897 Mathieu Dreyfus made a complaint to the minister of war against Esterhazy. The controversy was now public and the army had no choice but to open an investigation. At the end of 1897, Picquart returned to Paris and made public his doubts about the guilt of Dreyfus because of his discoveries. Collusion to eliminate Picquart seemed to have failed. The challenge was very strong and turned to confrontation. To discredit Picquart, Esterhazy sent, without effect, letters of complaint to the president of the republic.

The Dreyfusard movement, led by Bernard Lazare,

Mathieu Dreyfus

Mathieu Dreyfus (1857–1930) was an Alsace, Alsatian Jewish industrialist and the older brother of Alfred Dreyfus, a French people, French military officer falsely convicted of treason in what became known as the Dreyfus affair. Mathieu was one ...

,

Joseph Reinach

Joseph Reinach (30 September 1856 – 18 April 1921) was a French author and politician. Biography

He was born in Paris. His two brothers Salomon Reinach and Théodore Reinach would later be known in the field of archaeology. After studying at L ...

and

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner gained momentum.

Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

, informed in mid-November 1897 by Scheurer-Kestner with documents, was convinced of the innocence of Dreyfus and undertook to engage himself officially.

["He had already intervened in ''Le Figaro'' in May 1896, in the article "''For the Jews''".] On 25 November 1897 the novelist published ''Mr. Scheurer-Kestner'' in ''

Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of reco ...

'', which was the first article in a series of three.

[According to the ''Syndicat'' of 1 December 1897 and the ''Minutes'' of 5 December 1897.] Faced with threats of massive cancellations from its readers, the paper's editor stopped supporting Zola. Gradually, from late-November through early-December 1897, a number of prominent people got involved in the fight for retrial. These included the authors

Octave Mirbeau (his first article was published three days after Zola) and

Anatole France, academic

Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, the librarian of the ''

École normale supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

''

Lucien Herr (who convinced

Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister.

As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of French Socialist le ...

and

Jean Jaurès), the authors of ''

La Revue Blanche

''La Revue blanche'' was a French art and literary magazine run between 1889 and 1903. Some of the greatest writers and artists of the time were its collaborators.

History

The ''Revue blanche'' was founded in Liège in 1889 and run by the Natans ...

'',

[At that time the heart of the artistic avant-garde, publishing ]Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel ''In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous Eng ...

, Saint-Pol-Roux

Paul-Pierre Roux, called Saint-Pol-Roux (15 January 1861, quartier de Saint-Henry, Marseille - 18 October 1940, Brest) was a French Symbolist poet.

Life

Marseille

Saint-Pol-Roux was born to a middle-class family in Marseille, where his fath ...

, Jules Renard, Charles Péguy, et al. (where Lazare knew the director Thadee Natanson), and the Clemenceau brothers

Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert ...

and

Georges. Blum tried in late November 1897 to sign, with his friend

Maurice Barrès

Auguste-Maurice Barrès (; 19 August 1862 – 4 December 1923) was a French novelist, journalist and politician. Spending some time in Italy, he became a figure in French literature with the release of his work ''The Cult of the Self'' in 1888. ...

, a petition calling for a retrial, but Barrès refused, broke with Zola and Blum in early-December, and began to popularize the term "intellectuals". This first break was the prelude to a division among the educated elite after 13 January 1898.

The Dreyfus Affair occupied more and more discussions, something the political world did not always recognize.

Jules Méline

Félix Jules Méline (; 20 May 183821 December 1925) was a French statesman, Prime Minister of France from 1896 to 1898.

Biography

Méline was born at Remiremont. Having taken up law as his profession, he was chosen a deputy in 1872, and in 187 ...

declared in the opening session of the National Assembly on 7 December 1897, "There is no Dreyfus affair. There is not now and there can be no Dreyfus affair."

Trial and acquittal of Esterhazy

General

Georges-Gabriel de Pellieux

George Gabriel de Pellieux (6 September 1842 – 15 July 1900) was a French army officer who was best known for ignoring evidence during the Dreyfus affair, a scandal in which a Jewish officer was convicted of treason on the basis of a forgery.

Ea ...

was responsible for conducting an investigation. It was brief, thanks to the General Staff's skillful manipulation of the investigator. The real culprit, they said, was Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart. The investigation was moving towards a predictable conclusion until Esterhazy's former mistress, Madame de Boulancy, published letters in ''Le Figaro'' in which ten years earlier Esterhazy had expressed violently his hatred for France and his contempt for the French army. The militarist press rushed to the rescue of Esterhazy with an unprecedented antisemitic campaign. The Dreyfusard press replied with strong new evidence in its possession.

Georges Clemenceau, in the newspaper ''

L'Aurore

''L’Aurore'' (; ) was a literary, liberal, and socialist newspaper published in Paris, France, from 1897 to 1914. Its most famous headline was Émile Zola's '' J'Accuse...!'' leading into his article on the Dreyfus Affair.

The newspaper was ...

'', asked, "Who protects Major Esterhazy? The law must stop sucking up to this ineffectual Prussian disguised as a French officer. Why? Who trembles before Esterhazy? What occult power, why shamefully oppose the action of justice? What stands in the way? Why is Esterhazy, a character of depravity and more than doubtful morals, protected while the accused is not? Why is an honest soldier such as Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart discredited, overwhelmed, dishonoured? If this is the case we must speak out!"

Although protected by the General Staff and therefore by the government, Esterhazy was obliged to admit authorship of the Francophobe letters published by ''Le Figaro''. This convinced the Office of the General Staff to find a way to stop the questions, doubts, and the beginnings of demands for justice. The idea was to require Esterhazy to demand a trial and be acquitted, to stop the noise and allow a return to order. Thus, to finally exonerate him, according to the old rule ,

["What is already judged is held to be true".] Esterhazy was set to appear before a military court on 10 January 1898. A "delayed" closed court

[The room is emptied as soon as discussion covers topics related to national defence, i.e., the testimony of Picquart.] trial was pronounced. Esterhazy was notified of the matter on the following day, along with guidance on the defensive line to take. The trial was not normal: the civil trial Mathieu and Lucy Dreyfus

[President Delegorgue refused to be questioned when he was called to the bar.] requested was denied, and the three handwriting experts decided the writing in the bordereau was not Esterhazy's. The accused was applauded and the witnesses booed and jeered. Pellieux intervened to defend the General Staff without legal substance. The real accused was Picquart, who was dishonoured by all the military protagonists of the affair. Esterhazy was acquitted unanimously the next day after just three minutes of deliberation.

[Bredin, ''The Affair'', p. 227. ] With all the cheering, it was difficult for Esterhazy to make his way toward the exit, where some 1,500 people were waiting.

By error an innocent person was convicted, but on order the guilty party was acquitted. For many moderate Republicans it was an intolerable infringement of the fundamental values they defended. The acquittal of Esterhazy therefore brought about a change of strategy for the Dreyfusards. Liberalism-friendly Scheurer-Kestner and

Reinach, took more combative and rebellious action. In response to the acquittal, large and violent riots by anti-Dreyfusards and anti-Semites broke out across France.

Flush with victory, the General Staff arrested Picquart on charges of violation of professional secrecy following the disclosure of his investigation through his lawyer, who revealed it to Senator Scheurer-Kestner. The colonel, although placed under arrest at

Fort Mont-Valérien

Fort Mont-Valérien ( French: ''Forteresse du Mont-Valérien'') is a fortress in Suresnes, a western Paris suburb, built in 1841 as part of the city's ring of modern fortifications. It overlooks the Bois de Boulogne.

History

Before Thiers built ...

, did not give up and involved himself further in the affair. When Mathieu thanked him, he replied curtly that he was "doing his duty".

Esterhazy benefited from special treatment by the upper echelons of the army, which was inexplicable except for the General Staff's desire to stifle any inclination to challenge the verdict of the court martial that had convicted Dreyfus in 1894. The army declared Esterhazy unfit for service.

Esterhazy's flight to England and confession

To avoid personal risk Esterhazy shaved off his prominent moustache and went into exile in England.

[''Dictionary of the Dreyfus Affair'', Thomas, entry "Esterházy in England". ]

Rachel Beer, editor of ''

The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' and the ''

Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'', English newspapers, knew that Esterhazy was in London because ''The Observer'' Paris correspondent had made a connection with him; she interviewed him twice, and he confessed to being the culprit: ''I wrote the bordereau''. She published the interviews in September 1898, reporting his confession and writing a

leader column accusing the French military of antisemitism and calling for a retrial for Dreyfus.

Esterhazy lived comfortably in England until his death in 1923.

[

]

''J'Accuse ...!'' 1898

The Dreyfus affair becomes "The Affair"

On 13 January 1898,

On 13 January 1898, Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

touched off a new dimension in the Dreyfus Affair, which became known simply as ''The Affair''. The first great Dreyfusard intellectual