L'Orfeo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''L'Orfeo'' is, in Redlich's analysis, the product of two musical epochs. It combines elements of the traditional

''L'Orfeo'' is, in Redlich's analysis, the product of two musical epochs. It combines elements of the traditional

''L'Orfeo'' libretto in Italian with English translation

''L'Orfeo'' libretto in German translation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Orfeo Operas by Claudio Monteverdi Pastoral operas Italian-language operas Operas 1607 operas Operas about Orpheus Operas based on Metamorphoses Proserpina

''L'Orfeo'' ( SV 318) (), sometimes called ''La favola d'Orfeo'' , is a late

Claudio Monteverdi, born in Cremona in 1567, was a musical

Claudio Monteverdi, born in Cremona in 1567, was a musical

When Monteverdi composed ''L'Orfeo'' he had a thorough grounding in theatrical music. He had been employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years, much of it as a performer or arranger of stage music, and in 1604 he had written the

When Monteverdi composed ''L'Orfeo'' he had a thorough grounding in theatrical music. He had been employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years, much of it as a performer or arranger of stage music, and in 1604 he had written the

For the purpose of analysis the music scholar

For the purpose of analysis the music scholar

The date for the first performance of ''L'Orfeo'', 24 February 1607, is evidenced by two letters, both dated 23 February. In the first, Francesco Gonzaga informs his brother that the "musical play" will be performed tomorrow; it is clear from earlier correspondence that this refers to ''L'Orfeo''. The second letter is from a Gonzaga court official, Carlo Magno, and gives more details: "Tomorrow evening the Most Serene Lord the Prince is to sponsor a

The date for the first performance of ''L'Orfeo'', 24 February 1607, is evidenced by two letters, both dated 23 February. In the first, Francesco Gonzaga informs his brother that the "musical play" will be performed tomorrow; it is clear from earlier correspondence that this refers to ''L'Orfeo''. The second letter is from a Gonzaga court official, Carlo Magno, and gives more details: "Tomorrow evening the Most Serene Lord the Prince is to sponsor a

After years of neglect, Monteverdi's music began to attract the interest of pioneer music historians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and from the second quarter of the 19th century onwards he is discussed increasingly in scholarly works. In 1881 a truncated version of the ''L'Orfeo'' score, intended for study rather than performance, was published in Berlin by

After years of neglect, Monteverdi's music began to attract the interest of pioneer music historians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and from the second quarter of the 19th century onwards he is discussed increasingly in scholarly works. In 1881 a truncated version of the ''L'Orfeo'' score, intended for study rather than performance, was published in Berlin by

broadcast a performance of the opera from La Scala, Milan. Despite the reluctance of some major opera houses to stage ''L'Orfeo'', it is a popular work with the leading Baroque ensembles. During the period 2008–10, the French-based Les Arts Florissants, under its director William Christie, presented the Monteverdi trilogy of operas (''L'Orfeo'', '' Il ritorno d'Ulisse'' and ''Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

/early Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

''favola in musica'', or opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

, by Claudio Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string player. A composer of both secular and sacred music, and a pioneer in the development of opera, he is considered ...

, with a libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

by Alessandro Striggio

Alessandro Striggio (c. 1536/1537 – 29 February 1592) was an Italian composer, instrumentalist and diplomat of the Renaissance. He composed numerous madrigals as well as dramatic music, and by combining the two, became the inventor of madrigal c ...

. It is based on the Greek legend of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

, and tells the story of his descent to Hades and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

back to the living world. It was written in 1607 for a court performance during the annual Carnival at Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

. While Jacopo Peri

Jacopo Peri (20 August 156112 August 1633), known under the pseudonym Il Zazzerino, was an Italian composer and singer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque styles, and is often called the inventor of opera. He wrote th ...

's ''Dafne

''Dafne'' is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini survives complete; the mostly lost music was completed by Jacopo Peri, but at least two of the six surviving fragment ...

'' is generally recognised as the first work in the opera genre, and the earliest surviving opera is Peri's '' Euridice'', ''L'Orfeo'' is the earliest that is still regularly performed.

By the early 17th century the traditional intermedio

The intermedio (also intromessa, introdutto, tramessa, tramezzo, intermezzo, intermedii), in the Italian Renaissance, was a theatrical performance or spectacle with music and often dance, which was performed between the acts of a play to celeb ...

—a musical sequence between the acts of a straight play—was evolving into the form of a complete musical drama or "opera". Monteverdi's ''L'Orfeo'' moved this process out of its experimental era and provided the first fully developed example of the new genre. After its initial performance the work was staged again in Mantua, and possibly in other Italian centres in the next few years. Its score was published by Monteverdi in 1609 and again in 1615. After the composer's death in 1643 the opera went unperformed for many years, and was largely forgotten until a revival of interest in the late 19th century led to a spate of modern editions and performances. At first these performances tended to be concert (unstaged) versions within institutes and music societies, but following the first modern dramatised performance in Paris, in 1911, the work began to be seen in theatres. After the Second World War many recordings were issued, and the opera was increasingly staged in opera houses, although some leading venues resisted it. In 2007, the quatercentenary of the premiere was celebrated by performances throughout the world.

In his published score Monteverdi lists around 41 instruments to be deployed, with distinct groups of instruments used to depict particular scenes and characters. Thus strings, harpsichords and recorders represent the pastoral fields of Thrace with their nymphs and shepherds, while heavy brass illustrates the underworld and its denizens. Composed at the point of transition from the Renaissance era to the Baroque, ''L'Orfeo'' employs all the resources then known within the art of music, with particularly daring use of polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, h ...

. The work is not orchestrated as such; in the Renaissance tradition instrumentalists followed the composer's general instructions but were given considerable freedom to improvise.

Historical background

Claudio Monteverdi, born in Cremona in 1567, was a musical

Claudio Monteverdi, born in Cremona in 1567, was a musical prodigy

Prodigy, Prodigies or The Prodigy may refer to:

* Child prodigy, a child who produces meaningful output to the level of an adult expert performer

** Chess prodigy, a child who can beat experienced adult players at chess

Arts, entertainment, and ...

who studied under Marc'Antonio Ingegneri

Marc'Antonio Ingegneri (also spelled Ingegnieri, Ingignieri, Ingignero, Inzegneri) (c. 1535 or 1536 – 1 July 1592) was an Italian composer of the late Renaissance. He was born in Verona and died in Cremona. Even though he spent most of his life ...

, the'' maestro di cappella'' (head of music) at Cremona Cathedral

Cremona Cathedral ( it, Duomo di Cremona, ''Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta''), dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, is a Catholic cathedral in Cremona, Lombardy, northern Italy. It is the seat of the Bishop of Cremona. Its ...

. After training in singing, string playing and composition, Monteverdi worked as a musician in Verona and Milan until, in 1590 or 1591, he secured a post as ''suonatore di vivuola'' (viola player) at Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga's court at Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

. Through ability and hard work Monteverdi rose to become Gonzaga's ''maestro della musica'' (master of music) in 1601.

Vincenzo Gonzaga's particular passion for musical theatre and spectacle grew from his family connections with the court of Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

. Towards the end of the 16th century innovative Florentine musicians were developing the intermedio

The intermedio (also intromessa, introdutto, tramessa, tramezzo, intermezzo, intermedii), in the Italian Renaissance, was a theatrical performance or spectacle with music and often dance, which was performed between the acts of a play to celeb ...

—a long-established form of musical interlude inserted between the acts of spoken dramas—into increasingly elaborate forms. Led by Jacopo Corsi

Jacopo Corsi (17 July 1561 – 29 December 1602) was an Italian composer of the late Renaissance and early Baroque and one of Florence's leading patrons of the arts, after only the Medicis. His best-known work is '' Dafne'' (1597/98), whose sc ...

, these successors to the renowned Camerata were responsible for the first work generally recognised as belonging to the genre of opera: ''Dafne

''Dafne'' is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini survives complete; the mostly lost music was completed by Jacopo Peri, but at least two of the six surviving fragment ...

'', composed by Corsi and Jacopo Peri

Jacopo Peri (20 August 156112 August 1633), known under the pseudonym Il Zazzerino, was an Italian composer and singer of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque styles, and is often called the inventor of opera. He wrote th ...

and performed in Florence in 1598. This work combined elements of madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance music, Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque music, Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The Polyphony, polyphoni ...

singing and monody

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italian song of ...

with dancing and instrumental passages to form a dramatic whole. Only fragments of its music still exist, but several other Florentine works of the same period—''Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo

''Rappresentatione di anima et di corpo'' (Portrayal of the Soul and the Body) is a musical work by Emilio de' Cavalieri to a libretto by Agostino Manni (1548-1618). With it, Cavalieri regarded himself as the composer of the first opera or orator ...

'' by Emilio de' Cavalieri, Peri's '' Euridice'' and Giulio Caccini

Giulio Romolo Caccini (also Giulio Romano) (8 October 1551 – buried 10 December 1618) was an Italian composer, teacher, singer, instrumentalist and writer of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He was one of the founders of the genre o ...

's identically titled '' Euridice''—survive complete. These last two works were the first of many musical representations of the Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

myth as recounted in Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

'', and as such were direct precursors of Monteverdi's ''L'Orfeo''.

The Gonzaga court had a long history of promoting dramatic entertainment. A century before Duke Vincenzo's time the court had staged Angelo Poliziano

Agnolo (Angelo) Ambrogini (14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known by his nickname Poliziano (; anglicized as Politian; Latin: '' Politianus''), was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His scho ...

's lyrical drama ''La favola di Orfeo'', at least half of which was sung rather than spoken. More recently, in 1598 Monteverdi had helped the court's musical establishment produce Giovanni Battista Guarini

Giovanni Battista Guarini (10 December 1538 – 7 October 1612) was an Italian poet, dramatist, and diplomat.

Life

Guarini was born in Ferrara. On the termination of his studies at the universities of Pisa, Padua and Ferrara, he was appointed pr ...

's play ''Il pastor fido

''Il pastor fido'' (''The Faithfull Shepherd'' in Richard Fanshawe's 1647 English translation) is a pastoral tragicomedy set in Arcadia by Giovanni Battista Guarini, first published in 1590 in Venice.

Plot summary

To redress an ancient wron ...

'', described by theatre historian Mark Ringer

Mark Ringer (born December 8, 1959) American writer, theater and opera historian, director and actor. Ringer’s books include ''Electra and the Empty Urn: Metatheater and Role Playing in Sophocles'', a critical analysis of theatrical self-awaren ...

as a "watershed theatrical work" which inspired the Italian craze for pastoral drama. On 6 October 1600, while visiting Florence for the wedding of Maria de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (french: link=no, Marie de Médicis, it, link=no, Maria de' Medici; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV of France of the House of Bourbon, and Regent of the Kingd ...

to King Henry IV of France, Duke Vincenzo attended the premiere of Peri's ''Euridice''. It is likely that his principal musicians, including Monteverdi, were also present at this performance. The Duke quickly recognised the novelty of this new form of dramatic entertainment, and its potential for bringing prestige to those prepared to sponsor it.

Creation

Libretto

Among those present at the ''Euridice'' performance in October 1600 was a young lawyer and career diplomat from Gonzaga's court,Alessandro Striggio

Alessandro Striggio (c. 1536/1537 – 29 February 1592) was an Italian composer, instrumentalist and diplomat of the Renaissance. He composed numerous madrigals as well as dramatic music, and by combining the two, became the inventor of madrigal c ...

, son of a well-known composer of the same name. The younger Striggio was himself a talented musician; as a 16-year-old, he had played the viol at the wedding festivities of Duke Ferdinando of Tuscany in 1589. Together with Duke Vincent's two young sons, Francesco

Francesco, the Italian (and original) version of the personal name " Francis", is the most common given name among males in Italy. Notable persons with that name include:

People with the given name Francesco

* Francesco I (disambiguation), sev ...

and Fernandino, he was a member of Mantua's exclusive intellectual society, the , which provided the chief outlet for the city's theatrical works. It is not clear at what point Striggio began his libretto for ''L'Orfeo'', but work was evidently under way in January 1607. In a letter written on 5 January, Francesco Gonzago asks his brother, then attached to the Florentine court, to obtain the services of a high quality castrato from the Grand Duke's establishment, for a "play in music" being prepared for the Mantuan Carnival.

Striggio's main sources for his libretto were Books 10 and 11 of Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

'' and Book Four of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

's ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

''. These provided him with the basic material, but not the structure for a staged drama; the events of acts 1 and 2 of the libretto are covered by a mere 13 lines in the ''Metamorphoses''. For help in creating a dramatic form, Striggio drew on other sources—Poliziano's 1480 play, Guarini's ''Il pastor fido'', and Ottavio Rinuccini

Ottavio Rinuccini (20 January 1562 – 28 March 1621) was an Italian poet, courtier, and opera librettist at the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. In collaborating with Jacopo Peri to produce the first opera, '' Dafne'', i ...

's libretto for Peri's ''Euridice''. Musicologist Gary Tomlinson Gary Alfred Tomlinson (born December 4, 1951) is an American musicologist and the John Hay Whitney Professor of Music and Humanities at Yale University. He was formerly the Annenberg Professor in the Humanities at the University of Pennsylvania. He ...

remarks on the many similarities between Striggio's and Rinuccini's texts, noting that some of the speeches in ''L'Orfeo'' "correspond closely in content and even in locution to their counterparts in ''L'Euridice''". The critic Barbara Russano Hanning

Barbara Russano Hanning (born 1940) is an American musicologist who specializes in 16th- and 17th-century Italian music. She has also written works on the music of 18th-century France and on musical iconography.

Education and career

She earned ...

writes that Striggio's verses are less subtle than those of Rinuccini, although the structure of Striggio's libretto is more interesting. Rinuccini, whose work had been written for the festivities accompanying a Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Mu ...

wedding, was obliged to alter the myth to provide a "happy ending" suitable for the occasion. By contrast, because Striggio was not writing for a formal court celebration he could be more faithful to the spirit of the myth's conclusion, in which Orfeo is killed and dismembered by deranged maenad

In Greek mythology, maenads (; grc, μαινάδες ) were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones". Maenads were known as Bassarids, ...

s or "Bacchantes". He chose, in fact, to write a somewhat muted version of this bloody finale, in which the Bacchantes threaten Orfeo's destruction but his actual fate is left in doubt.

The libretto was published in Mantua in 1607 to coincide with the premiere and incorporated Striggio's ambiguous ending. However, Monteverdi's score published in Venice in 1609 by Ricciardo Amadino shows an entirely different resolution, with Orpheus transported to the heavens through the intervention of Apollo. According to Ringer, Striggio's original ending was almost certainly used at the opera's premiere, but there is no doubt that Monteverdi believed the revised ending was aesthetically correct. The musicologist Nino Pirrotta

Nino Pirrotta (13 June 1908 in Palermo – 22 January 1998 in Palermo) was an Italian musicologist of international renown who specialized in Italian music from the late medieval, Renaissance and early Baroque eras.

Life and career

In 1931 Pir ...

argues that the Apollo ending was part of the original plan for the work, but was not staged at the premiere because the small room which hosted the event could not contain the theatrical machinery that this ending required. The Bacchantes scene was a substitution; Monteverdi's intentions were restored when this constraint was removed.

Composition

When Monteverdi composed ''L'Orfeo'' he had a thorough grounding in theatrical music. He had been employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years, much of it as a performer or arranger of stage music, and in 1604 he had written the

When Monteverdi composed ''L'Orfeo'' he had a thorough grounding in theatrical music. He had been employed at the Gonzaga court for 16 years, much of it as a performer or arranger of stage music, and in 1604 he had written the ballo

The ''ballo'' was an Italian dance form during the fifteenth century, most noted for its frequent changes of tempo and meter. The name ''ballo'' has its origin in Latin ''ballō'', ''ballāre'', meaning "to dance", which in turn comes from the Gre ...

''Gli amori di Diane ed Endimone'' for the 1604–05 Mantua Carnival. The elements from which Monteverdi constructed his first opera score—the aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

, the strophic song, recitative

Recitative (, also known by its Italian name "''recitativo''" ()) is a style of delivery (much used in operas, oratorios, and cantatas) in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms and delivery of ordinary speech. Recitative does not repeat ...

, choruses, dances, dramatic musical interludes—were, as conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt has pointed out, not created by him, but "he blended the entire stock of newest and older possibilities into a unity that was indeed new". Musicologist Robert Donington

Robert Donington (4 May 1907 – 20 January 1990) was a British musicologist and instrumentalist influential in the early music movement and in Wagner studies.

He was educated at St Paul's School, London, and studied at the University of Oxfor ...

writes similarly: " he scorecontains no element which was not based on precedent, but it reaches complete maturity in that recently developed form ... Here are words as directly expressed in music as he pioneers of operawanted them expressed; here is music expressing them ... with the full inspiration of genius."

Monteverdi states the orchestral requirements at the beginning of his published score, but in accordance with the practice of the day he does not specify their exact usage. At that time it was usual to allow each interpreter of the work freedom to make local decisions, based on the orchestral forces at their disposal. These could differ sharply from place to place. Furthermore, as Harnoncourt points out, the instrumentalists would all have been composers and would have expected to collaborate creatively at each performance, rather than playing a set text. Another practice of the time was to allow singers to embellish their arias. Monteverdi wrote plain and embellished versions of some arias, such as Orfeo's " Possente spirto", but according to Harnoncourt "it is obvious that where he did not write any embellishments he did not want any sung".

Each act of the opera deals with a single element of the story, and each ends with a chorus. Despite the five-act structure, with two sets of scene changes, it is likely that ''L'Orfeo'' conformed to the standard practice for court entertainments of that time and was played as a continuous entity, without intervals or curtain descents between acts. It was the contemporary custom for scene shifts to take place in sight of the audience, these changes being reflected musically by changes in instrumentation, key and style.

Instrumentation

For the purpose of analysis the music scholar

For the purpose of analysis the music scholar Jane Glover

Dame Jane Alison Glover (born 13 May 1949) is a British-born conductor and musicologist.

Early life

Born at Helmsley, Glover attended Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls. Her father, Robert Finlay Glover, MA ( TCD), was headmaster of ...

has divided Monteverdi's list of instruments into three main groups: strings, brass and continuo, with a few further items not easily classifiable. The strings grouping is formed from ten members of the violin family (''viole da brazzo''), two double basses

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox additions such as the octobass). Simila ...

(''contrabassi de viola''), and two kit violin

The pochette is a small stringed instrument of the bowed variety. It is essentially a very small violin-like wood instrument designed to fit in a pocket, hence its common name, the "pochette" (French for ''small pocket'').

Also known as a pocket ...

s (''violini piccoli alla francese''). The ''viole da brazzo'' are in two five-part ensembles, each comprising two violins, two violas and a cello. The brass group contains four or five trombones (sackbut

The term sackbut refers to the early forms of the trombone commonly used during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of the tube to change pitch, but is di ...

s), three or four trumpets and two cornett

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is an early wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. It was used in what are now called alta capellas or wind ensembles. It is not to be confused wi ...

s. The continuo forces include two harpsichords (''duoi gravicembani''), a double harp (''arpa doppia''), two or three chitarroni, two pipe organs (''organi di legno''), three bass viola da gamba

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitch ...

, and a regal or small reed organ. Outside of these groupings are two recorders (''flautini alla vigesima secunda''), and possibly one or more cittern

The cittern or cithren ( Fr. ''cistre'', It. ''cetra'', Ger. ''Cister,'' Sp. ''cistro, cedra, cítola'') is a stringed instrument dating from the Renaissance. Modern scholars debate its exact history, but it is generally accepted that it is d ...

s—unlisted by Monteverdi, but included in instructions relating to the end of act 4.

Instrumentally, the two worlds represented within the opera are distinctively portrayed. The pastoral world of the fields of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

is represented by the strings, harpsichords, harp, organs, recorders and chitarroni. The remaining instruments, mainly brass, are associated with the Underworld, though there is not an absolute distinction; strings appear on several occasions in the Hades scenes. Within this general ordering, specific instruments or combinations are used to accompany some of the main characters—Orpheus by harp and organ, shepherds by harpsichord and chitarrone, the Underworld gods by trombones and regal. All of these musical distinctions and characterisations were in accordance with the longstanding traditions of the Renaissance orchestra, of which the large ''L'Orfeo'' ensemble is typical.

Monteverdi instructs his players generally to "lay

Lay may refer to:

Places

*Lay Range, a subrange of mountains in British Columbia, Canada

*Lay, Loire, a French commune

*Lay (river), France

*Lay, Iran, a village

*Lay, Kansas, United States, an unincorporated community

People

* Lay (surname)

* ...

the work as simply and correctly as possible, and not with many florid passages or runs". Those playing ornamentation instruments such as strings and flutes are advised to "play nobly, with much invention and variety", but are warned against overdoing it, whereby "nothing is heard but chaos and confusion, offensive to the listener". Since at no time are all the instruments played together, the number of players needed is less than the number of instruments. Harnoncourt indicates that in Monteverdi's day the numbers of players and singers together, and the small rooms in which performances were held, often meant that the audience barely numbered more than the performers.

Three of the instruments used in the original performance of ''L'Orfeo'' have had recent revivals: the cornett

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is an early wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. It was used in what are now called alta capellas or wind ensembles. It is not to be confused wi ...

o (usually paired with sackbuts), the (a multi-course harp

A multi-course harp is a harp with more than one row of strings. Harps with two rows are called double harps; harps with three rows are called triple harps. A harp with only one row of strings is called a single-course harp.

Diatonic double ha ...

with sharps and flats) and the regal (an organ with fractional-length reed pipe

A reed pipe (also referred to as a ''lingual'' pipe) is an organ pipe that is sounded by a vibrating brass strip known as a ''reed''. Air under pressure (referred to as ''wind'') is directed towards the reed, which vibrates at a specific pitc ...

s). Instrumental color was widely used in specific dramatic situations during the 17c: in particular the regal was associated with Hades.

Roles

In his ''personaggi'' listed in the 1609 score, Monteverdi unaccountably omits La messaggera (the Messenger), and indicates that the final chorus of shepherds who perform themoresca

Moresca (Italian), morisca (Spanish), mourisca (Portuguese) or moresque, mauresque (French), also known in French as the danse des bouffons, is a dance of exotic character encountered in Europe in the Renaissance period. This dance usually took fo ...

(Moorish dance) at the opera's end are a separate group (''che fecero la moresca nel fine''). Little information is available about who sang the various roles in the first performance. A letter published at Mantua in 1612 records that the distinguished tenor and composer Francesco Rasi

Francesco Rasi (14 May 1574 – 30 November 1621) was an Italian composer, singer (tenor), chitarrone player, and poet.

Rasi was born in Arezzo. He studied at the University of Pisa and in 1594 he was studying with Giulio Caccini. He may have bee ...

took part, and it is generally assumed that he sang the title role. Rasi could sing in both the tenor and bass ranges "with exquisite style ... and extraordinary feeling". The involvement in the premiere of a Florentine castrato, Giovanni Gualberto Magli, is confirmed by correspondence between the Gonzaga princes. Magli sang the prologue, Proserpina and possibly one other role, either La messaggera or Speranza. The musicologist and historian Hans Redlich

Hans Ferdinand Redlich (11 February 1903 – 27 November 1968) was an Austrian musicologist, writer, conductor and composer who, due to political disruption by the Nazi Party, lived and worked in Britain from 1939 until his death nearly thirty yea ...

mistakenly allocates Magli to the role of Orfeo.

A clue about who played Euridice is contained in a 1608 letter to Duke Vincenzo. It refers to "that little priest who performed the role of Euridice in the Most Serene Prince's ''Orfeo''". This priest was possibly Padre Girolamo Bacchini, a castrato known to have had connections to the Mantuan court in the early 17th century. The Monteverdi scholar Tim Carter speculates that two prominent Mantuan tenors, Pandolfo Grande and Francesco Campagnola may have sung minor roles in the premiere.

There are solo parts for four shepherds and three spirits. Carter calculates that through the doubling of roles that the text allows, a total of ten singers—three sopranos, two altos, three tenors and two basses—is required for a performance, with the soloists (except Orfeo) also forming the chorus. Carter's suggested role-doublings include La musica with Euridice, Ninfa with Proserpina and La messaggera with Speranza.

Synopsis

The action takes place in two contrasting locations: the fields ofThrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

(acts 1, 2 and 5) and the Underworld (acts 3 and 4). An instrumental toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virtu ...

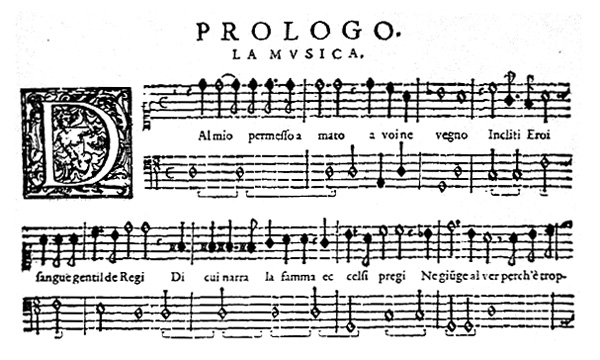

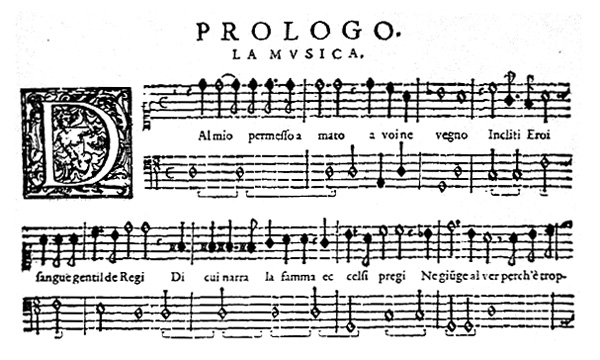

(English: "tucket", meaning a flourish on trumpets) precedes the entrance of La musica, representing the "spirit of music", who sings a prologue of five stanzas of verse. After a gracious welcome to the audience she announces that she can, through sweet sounds, "calm every troubled heart". She sings a further paean to the power of music, before introducing the drama's main protagonist, Orfeo, who "held the wild beasts spellbound with his song".

Act 1

After La musica's final request for silence, the curtain rises on act 1 to reveal a pastoral scene.Orfeo

Orfeo Classic Schallplatten und Musikfilm GmbH of Munich was a German independent classical record label founded in 1979 by Axel Mehrle and launched in 1980. It has been owned by Naxos since 2015.

History

The Orfeo music label was registered ...

and Euridice enter together with a chorus of nymphs and shepherds, who act in the manner of a Greek chorus

A Greek chorus, or simply chorus ( grc-gre, χορός, chorós), in the context of ancient Greek tragedy, comedy, satyr plays, and modern works inspired by them, is a homogeneous, non-individualised group of performers, who comment with a collect ...

, commenting on the action both as a group and as individuals. A shepherd announces that this is the couple's wedding day; the chorus responds, first in a stately invocation ("Come, Hymen

The hymen is a thin piece of mucosal tissue that surrounds or partially covers the external vaginal opening. It forms part of the vulva, or external genitalia, and is similar in structure to the vagina.

In children, a common appearance of the ...

, O come") and then in a joyful dance ("Leave the mountains, leave the fountains"). Orfeo and Euridice sing of their love for each other before leaving with most of the group for the wedding ceremony in the temple. Those left on stage sing a brief chorus, commenting on how Orfeo used to be one "for whom sighs were food and weeping was drink" before love brought him to a state of sublime happiness.

Act 2

Orfeo returns with the main chorus, and sings with them of the beauties of nature. Orfeo then muses on his former unhappiness, but proclaims: "After grief one is more content, after pain one is happier". The mood of contentment is abruptly ended when La messaggera enters, bringing the news that, while gathering flowers, Euridice has received a fatal snakebite. The chorus expresses its anguish: "Ah, bitter happening, ah, impious and cruel fate!", while the Messaggera castigates herself as the bearing of bad tidings ("For ever I will flee, and in a lonely cavern lead a life in keeping with my sorrow"). Orfeo, after venting his grief and incredulity ("Thou art dead, my life, and I am breathing?"), declares his intention to descend into the Underworld and persuade its ruler to allow Euridice to return to life. Otherwise, he says, "I shall remain with thee in the company of death". He departs, and the chorus resumes its lament.Act 3

Orfeo is guided by Speranza to the gates of Hades. Having pointed out the words inscribed on the gate ("Abandon hope, all ye who enter here"), Speranza leaves. Orfeo is now confronted with the ferryman Caronte, who addresses Orfeo harshly and refuses to take him across the river Styx. Orfeo attempts to persuade Caronte by singing a flattering song to him ("Mighty spirit and powerful divinity"), and, although the ferryman is moved by his music ("Indeed thou charmest me, appeasing my heart"), he does not allow him to pass, claiming he is incapable of feeling pity. However, when Orfeo takes up his lyre and plays, Caronte is soothed into sleep. Seizing his chance, Orfeo steals the ferryman's boat and crosses the river, entering the Underworld while a chorus of spirits reflects that nature cannot defend herself against man: "He has tamed the sea with fragile wood, and disdained the rage of the winds."Act 4

In the Underworld,Proserpina

Proserpina ( , ) or Proserpine ( ) is an ancient Roman goddess whose iconography, functions and myths are virtually identical to those of Greek Persephone. Proserpina replaced or was combined with the ancient Roman fertility goddess Libera, whose ...

, Queen of Hades, who has been deeply affected by Orfeo's singing, petitions King Plutone, her husband, for Euridice's release. Moved by her pleas, Plutone agrees on the condition that, as he leads Euridice towards the world, Orfeo must not look back. If he does, "a single glance will condemn him to eternal loss". Orfeo enters, leading Euridice and singing confidently that on that day he will rest on his wife's white bosom. But as he sings a note of doubt creeps in: "Who will assure me that she is following?". Perhaps, he thinks, Plutone, driven by envy, has imposed the condition through spite? Suddenly distracted by an off-stage commotion, Orfeo looks round; immediately, the image of Euridice begins to fade. She sings, despairingly: "Losest thou me through too much love?" and disappears. Orfeo attempts to follow her but is drawn away by an unseen force. The chorus of spirits sings that Orfeo, having overcome Hades, was in turn overcome by his passions.

Act 5

Back in the fields of Thrace, Orfeo has a long soliloquy in which he laments his loss, praises Euridice's beauty and resolves that his heart will never again be pierced by Cupid's arrow. An off-stage echo repeats his final phrases. Suddenly, in a cloud, Apollo descends from the heavens and chastises him: "Why dost thou give thyself up as prey to rage and grief?" He invites Orfeo to leave the world and join him in the heavens, where he will recognise Euridice's likeness in the stars. Orfeo replies that it would be unworthy not to follow the counsel of such a wise father, and together they ascend. A shepherds' chorus concludes that "he who sows in suffering shall reap the fruit of every grace", before the opera ends with a vigorousmoresca

Moresca (Italian), morisca (Spanish), mourisca (Portuguese) or moresque, mauresque (French), also known in French as the danse des bouffons, is a dance of exotic character encountered in Europe in the Renaissance period. This dance usually took fo ...

.

Original libretto ending

In Striggio's 1607 libretto, Orfeo's act 5 soliloquy is interrupted, not by Apollo's appearance but by a chorus ofmaenad

In Greek mythology, maenads (; grc, μαινάδες ) were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones". Maenads were known as Bassarids, ...

s or Bacchantes—wild, drunken women—who sing of the "divine fury" of their master, the god Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

. The cause of their wrath is Orfeo and his renunciation of women; he will not escape their heavenly anger, and the longer he evades them the more severe his fate will be. Orfeo leaves the scene and his destiny is left uncertain, as the Bacchantes devote themselves for the rest of the opera to wild singing and dancing in praise of Bacchus. The early music authority Claude Palisca believes that the two endings are not incompatible; Orfeo might evade the fury of the Bacchantes and be rescued by Apollo. However, this alternative ending in any case nearer to original classic myth, where the Bacchantes also appear, but it is made explicit that they torture him to his death, followed by reunion as a shade with Euridice but no apotheosis nor any interaction with Apollo.

Reception and performance history

Premiere and early performances

The date for the first performance of ''L'Orfeo'', 24 February 1607, is evidenced by two letters, both dated 23 February. In the first, Francesco Gonzaga informs his brother that the "musical play" will be performed tomorrow; it is clear from earlier correspondence that this refers to ''L'Orfeo''. The second letter is from a Gonzaga court official, Carlo Magno, and gives more details: "Tomorrow evening the Most Serene Lord the Prince is to sponsor a

The date for the first performance of ''L'Orfeo'', 24 February 1607, is evidenced by two letters, both dated 23 February. In the first, Francesco Gonzaga informs his brother that the "musical play" will be performed tomorrow; it is clear from earlier correspondence that this refers to ''L'Orfeo''. The second letter is from a Gonzaga court official, Carlo Magno, and gives more details: "Tomorrow evening the Most Serene Lord the Prince is to sponsor a lay

Lay may refer to:

Places

*Lay Range, a subrange of mountains in British Columbia, Canada

*Lay, Loire, a French commune

*Lay (river), France

*Lay, Iran, a village

*Lay, Kansas, United States, an unincorporated community

People

* Lay (surname)

* ...

in a room in the apartments which the Most Serene Lady had the use of ...it should be most unusual, as all the actors are to sing their parts." The "Serene Lady" is Duke Vincenzo's widowed sister Margherita Gonzaga d'Este, who lived within the Ducal Palace. The room of the premiere cannot be identified with certainty; according to Ringer, it may have been the Galleria dei Fiumi, which has the dimensions to accommodate a stage and orchestra with space for a small audience.

There is no detailed account of the premiere, although Francesco wrote on 1 March that the work had "been to the great satisfaction of all who heard it", and had particularly pleased the Duke. The Mantuan court theologian and poet, Cherubino Ferrari wrote that: "Both poet and musician have depicted the inclinations of the heart so skilfully that it could not have been done better ... The music, observing due propriety, serves the poetry so well that nothing more beautiful is to be heard anywhere". After the premiere Duke Vincenzo ordered a second performance for 1 March; a third performance was planned to coincide with a proposed state visit to Mantua by the Duke of Savoy

The titles of count, then of duke of Savoy are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the county was held by the House of Savoy. The County of Savoy was elevated to a duchy at ...

. Francesco wrote to the Duke of Tuscany on 8 March, asking if he could retain the services of the castrato Magli for a little longer. However, the visit was cancelled, as was the celebratory performance.

There are suggestions that in the years following the premiere, ''L'Orfeo'' may have been staged in Florence, Cremona, Milan and Turin, though firmer evidence suggests that the work attracted limited interest beyond the Mantuan court. Francesco may have mounted a production in Casale Monferrato, where he was governor, for the 1609–10 Carnival, and there are indications that the work was performed on several occasions in Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label= Austro-Bavarian) is the fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the Roman settlement of ''Iuvavum''. Salzburg was founded ...

between 1614 and 1619, under the direction of Francesco Rasi. Years later, during the first flourish of Venetian opera in 1637–43, Monteverdi chose to revive his second opera, '' L'Arianna'' there, but not ''L'Orfeo''. There is some evidence of performances shortly after Monteverdi's death: in Geneva in 1643, and in Paris, at the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

, in 1647. Although according to Carter the work was still admired across Italy in the 1650s, it was subsequently forgotten, as largely was Monteverdi, until the revival of interest in his works in the late 19th century.

20th-century revivals

After years of neglect, Monteverdi's music began to attract the interest of pioneer music historians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and from the second quarter of the 19th century onwards he is discussed increasingly in scholarly works. In 1881 a truncated version of the ''L'Orfeo'' score, intended for study rather than performance, was published in Berlin by

After years of neglect, Monteverdi's music began to attract the interest of pioneer music historians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and from the second quarter of the 19th century onwards he is discussed increasingly in scholarly works. In 1881 a truncated version of the ''L'Orfeo'' score, intended for study rather than performance, was published in Berlin by Robert Eitner Robert Eitner (22October 18322February 1905) was a German musicologist, researcher and bibliographer.

Life

Robert Eitner was born and grew up in Breslau, the rapidly industrialising administrative capital of Silesia. He attended the St. Elisabet ...

. In 1904 the composer Vincent d'Indy

Paul Marie Théodore Vincent d'Indy (; 27 March 18512 December 1931) was a French composer and teacher. His influence as a teacher, in particular, was considerable. He was a co-founder of the Schola Cantorum de Paris and also taught at the P ...

produced an edition in French, which comprised only act 2, a shortened act 3 and act 4. This edition was the basis of the first public performance of the work in two-and-a-half centuries, a concert performance at d'Indy's Schola Cantorum on 25 February 1904. The distinguished writer Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (; 29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 "as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production a ...

, who was present, commended d'Indy for bringing the opera to life and returning it "to the beauty it once had, freeing it from the clumsy restorations which have disfigured it"—presumably a reference to Eitner's edition. The d'Indy edition was also the basis of the first modern staged performance of the work, at the Théâtre Réjane, Paris, on 2 May 1911.

An edition of the score by the minor Italian composer Giacomo Orefice

Giacomo Orefice (27 August 1865 – 22 December 1922) was an Italian composer.

He was born in Vicenza. He studied under Alessandro Busi and Luigi Mancinelli at the Liceo Musicale di Bologna, and later became professor of composition at the ...

(Milan, 1909) received several concert performances in Italy and elsewhere before and after the First World War. This edition was the basis of the opera's United States debut, another concert performance at the New York Met in April 1912. The opera was introduced to London, in d'Indy's edition, when it was sung to piano accompaniment at the Institut Français on 8 March 1924. The first British staged performance, with only small cuts, was given by the Oxford University Operatic Society on 7 December 1925, using an edition prepared for the event by Jack Westrup

Sir Jack Westrup (26 July 190421 April 1975) was an English Musicology, musicologist, writer, teacher and occasional conductor and composer.

Biography

Jack Allan Westrup was the second of the three sons of George Westrup, insurance clerk, of Dulw ...

. In the London '' Saturday Review'', music critic Dyneley Hussey

Dyneley Hussey (27 February 1893 – 6 September 1972) was an English war poet, journalist, art critic and music critic.

Life

Hussey was born in India and was the son of Colonel Charles Edward Hussey. He was educated at St Cyprian's School Eastbo ...

called the occasion "one of the most important events of recent years"; the production had "indicated at once Monteverdi's claim to rank among the great geniuses who have written dramatic music". Westrup's edition was revived in London at the Scala Theatre

The Scala Theatre was a theatre in Charlotte Street, London, off Tottenham Court Road. The first theatre on the site opened in 1772, and the theatre was demolished in 1969, after being destroyed by fire. From 1865 to 1882, the theatre was kn ...

in December 1929, the same year in which the opera received its first US staged performance, at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. The three Scala performances resulted in a financial disaster, and the opera was not seen again in Britain for 35 years.

Among a flurry of revivals after 1945 was Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ' ...

's edition, a full period reconstruction of the work prepared in 1943, which was staged and recorded at the Vienna Festival

__NOTOC__

The Wiener Festwochen (Vienna Festival) is a cultural festival in Vienna that takes place every year for five or six weeks in May and June. The Wiener Festwochen was established in 1951, when Vienna was still occupied by the four Alli ...

in 1954. This performance had a great impact on the young Nikolaus Harnoncourt, and was hailed as a masterpiece of scholarship and integrity. The first staged New York performance, by the New York City Opera

The New York City Opera (NYCO) is an American opera company located in Manhattan in New York City. The company has been active from 1943 through 2013 (when it filed for bankruptcy), and again since 2016 when it was revived.

The opera company, du ...

under Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appear ...

on 29 September 1960, saw the American operatic debut of Gérard Souzay

Gérard Souzay (8 December 1918 – 17 August 2004) was a French baritone, regarded as one of the very finest interpreters of mélodie (French art song) in the generation after Charles Panzéra and Pierre Bernac.

Background and education

He wa ...

, one of several baritones who have sung the role of Orfeo. The theatre was criticised by ''New York Times'' critic Harold C. Schonberg

Harold Charles Schonberg (29 November 1915 – 26 July 2003) was an American music critic and author. He is best known for his contributions in ''The New York Times'', where he was chief music critic from 1960 to 1980. In 1971, he became the fi ...

because, to accommodate a performance of Luigi Dallapiccola

Luigi Dallapiccola (February 3, 1904 – February 19, 1975) was an Italian composer known for his lyrical serialism, twelve-tone compositions.

Biography

Dallapiccola was born in Pisino d'Istria (at the time part of Austria-Hungary, current ...

's contemporary opera ''Il prigioniero

''Il prigioniero'' (''The Prisoner'') is an opera (originally a radio opera) in a prologue and one act, with music and libretto by Luigi Dallapiccola. The opera was first broadcast by the Italian radio station RAI on 1 December 1949. The work is ba ...

'', about a third of ''L'Orfeo'' was cut. Schonberg wrote: "Even the biggest aria in the opera, 'Possente spirito', has a good-sized slash in the middle ... 'L'Orfeo''is long enough, and important enough, not to mention beautiful enough, to have been the entire evening's opera."

By the latter part of the 20th century the opera was being shown all over the world. In 1965, Sadler's Wells

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-seat ...

, forerunner of English National Opera

English National Opera (ENO) is an opera company based in London, resident at the London Coliseum in St Martin's Lane. It is one of the two principal opera companies in London, along with The Royal Opera. ENO's productions are sung in English ...

(ENO), staged the first of many ENO presentations which would continue into the 21st century. Among various celebrations marking the opera's 400th anniversary in 2007 were a semi-staged performance at the Teatro Bibiena

The Teatro Bibiena di Mantova (also known as, among others, the Teatro Scientifico, Teatro Accademico or Teatrino della Accademia Filarmonica) was made by Antonio Galli da Bibbiena in 1767-1769 and decorated in 1773-1775 with a facade of Piermar ...

in Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

, a full-scale production by the English Bach Festival (EBF) at the Whitehall Banqueting House in London on 7 February, and an unconventional production by Glimmerglass Opera

The Glimmerglass Festival (formerly known as Glimmerglass Opera) is an American opera company. Founded in 1975 by Peter Macris, the Glimmerglass Festival presents an annual season of operas at the Alice Busch Opera Theater on Otsego Lake eight ...

in Cooperstown, New York, conducted by Antony Walker and directed by Christopher Alden. On 6 May 2010 the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...L'incoronazione di Poppea

''L'incoronazione di Poppea'' ( SV 308, ''The Coronation of Poppaea'') is an Italian opera by Claudio Monteverdi. It was Monteverdi's last opera, with a libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, and was first performed at the Teatro Santi Giovanni ...

'') in a series of performances at the Teatro Real

The Teatro Real (Royal Theatre) is an opera house in Madrid, Spain. Located at the Plaza de Oriente, opposite the Royal Palace, and known colloquially as ''El Real'', it is considered the top institution of the performing and musical arts in the ...

in Madrid.

Music

''L'Orfeo'' is, in Redlich's analysis, the product of two musical epochs. It combines elements of the traditional

''L'Orfeo'' is, in Redlich's analysis, the product of two musical epochs. It combines elements of the traditional madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance music, Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque music, Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The Polyphony, polyphoni ...

style of the 16th century with those of the emerging Florentine mode, in particular the use of recitative

Recitative (, also known by its Italian name "''recitativo''" ()) is a style of delivery (much used in operas, oratorios, and cantatas) in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms and delivery of ordinary speech. Recitative does not repeat ...

and monodic

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italian song of ...

singing as developed by the Camerata and their successors. In this new style, the text dominates the music; while sinfonia

Sinfonia (; plural ''sinfonie'') is the Italian word for symphony, from the Latin ''symphonia'', in turn derived from Ancient Greek συμφωνία ''symphōnia'' (agreement or concord of sound), from the prefix σύν (together) and ϕωνή (sou ...

s and instrumental ritornelli illustrate the action, the audience's attention is always drawn primarily to the words. The singers are required to do more than produce pleasant vocal sounds; they must represent their characters in depth and convey appropriate emotions.

Monterverdi's recitative style was influenced by Peri's, in ''Euridice'', although in ''L'Orfeo'' recitative is less preponderant than was usual in dramatic music at this time. It accounts for less than a quarter of the first act's music, around a third of the second and third acts, and a little under half in the final two acts.

The importance of ''L'Orfeo'' is not that it was the first work of its kind, but that it was the first attempt to apply the full resources of the art of music, as then evolved, to the nascent genre of opera. In particular, Monteverdi made daring innovations in the use of polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, h ...

, of which Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

had been the principal exponent. In ''L'Orfeo'', Monteverdi extends the rules, beyond the conventions which polyphonic composers, faithful to Palestrina, had previously considered as sacrosanct. Monteverdi was not in the generally understood sense an orchestrator; Ringer finds that it is the element of instrumental improvisation that makes each performance of a Monteverdi opera a "unique experience, and separates his work from the later operatic canon".

The opera begins with a martial-sounding toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virtu ...

for trumpets which is repeated twice. When played on period wind instruments the sound can be startling to modern audiences; Redlich calls it "shattering". Such flourishes were the standard signal for the commencement of performances at the Mantuan court; the opening chorus of Monteverdi's 1610 Vespers, also composed for Gonzaga's court, employs the same fanfare. The toccata acted as a salute to the Duke; according to Donington, if it had not been written, precedent would have required it to be improvised. As the brass sound of the toccata fades, it is replaced by the gentler tone of the strings ritornello which introduces La musica's prologue. The ritornello is repeated in shortened form between each of the prologue's five verses, and in full after the final verse. Its function within the opera as a whole is to represent the "power of music"; as such it is heard at the end of act 2, and again at the beginning of act 5, one of the earliest examples of an operatic leitmotiv

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglic ...

. It is temporally structured as a palindrome and its form of strophic variations allows Monteverdi to carefully shape musical time for expressive and structural purposes in the context of ''seconda prattica''.

After the prologue, act 1 follows in the form of a pastoral idyll. Two choruses, one solemn and one jovial are repeated in reverse order around the central love-song "Rosa del ciel" ("Rose of the heavens"), followed by the shepherds' songs of praise. The buoyant mood continues into act 2, with song and dance music influenced, according to Harnoncourt, by Monteverdi's experience of French music. The sudden entrance of La messaggera with the doleful news of Euridice's death, and the confusion and grief which follow, are musically reflected by harsh dissonances and the juxtaposition of keys. The music remains in this vein until the act ends with La musica's ritornello, a hint that the "power of music" may yet bring about a triumph over death. Monteverdi's instructions as the act concludes are that the violins, the organ and harpsichord become silent and that the music is taken up by the trombones, the cornett

The cornett, cornetto, or zink is an early wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. It was used in what are now called alta capellas or wind ensembles. It is not to be confused wi ...

s and the regal, as the scene changes to the Underworld.

The centrepiece of act 3, perhaps of the entire opera, is Orfeo's extended aria "Possente spirto e formidabil nume" ("Mighty spirit and powerful divinity"), by which he attempts to persuade Caronte to allow him to enter Hades. Monteverdi's vocal embellishments and virtuoso accompaniment provide what Carter describes as "one of the most compelling visual and aural representations" in early opera. Instrumental colour is provided by a chitarrone

The theorbo is a plucked string instrument of the lute family, with an extended neck and a second pegbox. Like a lute, a theorbo has a curved-back sound box (a hollow box) with a wooden top, typically with a sound hole, and a neck extending out ...

, a pipe-organ, two violins, two cornetts and a double-harp. This array, according to music historian and analyst John Whenham

John Whenham is an English musicologist and academic who specializes in early Italian baroque music. He earned both a Bachelor of Music and a Master of Music from the University of Nottingham, and a Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Oxfor ...

, is intended to suggest that Orfeo is harnessing all the available forces of music to support his plea. In act 4 the impersonal coldness of the Underworld is broken by the warmth of Proserpina's singing on behalf of Orfeo, a warmth that is retained until the dramatic moment at which Orfeo "looks back". The cold sounds of the sinfonia from the beginning of act 3 then remind us that the Underworld is, after all, entirely devoid of human feeling. The brief final act, which sees Orfeo's rescue and metamorphosis, is framed by the final appearance of La musica's ritornello and the lively moresca

Moresca (Italian), morisca (Spanish), mourisca (Portuguese) or moresque, mauresque (French), also known in French as the danse des bouffons, is a dance of exotic character encountered in Europe in the Renaissance period. This dance usually took fo ...

that ends the opera. This dance, says Ringer, recalls the jigs danced at the end of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's tragedies, and provides a means of bringing the audience back to their everyday world, "just as the toccata had led them into another realm some two hours before. The toccata and the moresca unite courtly reality with operatic illusion."

Recording history

The first recording of ''L'Orfeo'' was issued in 1939, a freely adapted version of Monteverdi's music byGiacomo Benvenuti

Giacomo Benvenuti (16 March 1885, Toscolano – 20 January 1943, Barbarano-Salò) was an Italian composer and musicologist. He was the son of organist Cristoforo Benvenuti and studied at the Liceo Musicale (now the Conservatorio Giovanni Battis ...

, given by the orchestra of La Scala Milan conducted by Ferrucio Calusio Ferrucio Calusio (1889 or 1890 – 3 June 1983) was an Argentine conductor. He began his career in the 1920s at La Scala in Milan, Italy as an assistant conductor to Arturo Toscanini. In 1927 he returned to his native country to join the conducting ...

. In 1949, for the recording of the complete opera by the Berlin Radio Orchestra conducted by Helmut Koch, the new medium of long-playing records

The LP (from "long playing" or "long play") is an analog sound storage medium, a phonograph record format characterized by: a speed of rpm; a 12- or 10-inch (30- or 25-cm) diameter; use of the "microgroove" groove specification; and ...

(LPs) was used. The advent of LP recordings was, as Harold C. Schonberg

Harold Charles Schonberg (29 November 1915 – 26 July 2003) was an American music critic and author. He is best known for his contributions in ''The New York Times'', where he was chief music critic from 1960 to 1980. In 1971, he became the fi ...

later wrote, an important factor in the postwar revival of interest in Renaissance and Baroque music, and from the mid-1950s recordings of ''L'Orfeo'' have been issued on many labels. The 1969 recording by Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Vienna Concentus Musicus, using Harnoncourt's edition based on period instruments, was praised for "making Monteverdi's music sound something like the way he imagined". In 1981 Siegfried Heinrich, with the Early Music Studio of the Hesse Chamber Orchestra, recorded a version which re-created the original Striggio libretto ending, adding music from Monteverdi's 1616 ballet ''Tirsi e Clori'' for the Bacchante scenes. Among more recent recordings, that of Emmanuelle Haïm

Emmanuelle Haïm (; born 11 May 1962) is a French harpsichordist and conductor with a particular interest in early music and Baroque music.

Early life, student and assistant years

Haïm was born and grew up in Paris, and was raised Catholic al ...

in 2004 has been praised for its dramatic effect.

Editions

After the publication of the ''L'Orfeo'' score in 1609, the same publisher ( Ricciardo Amadino of Venice) brought it out again in 1615. Facsimiles of these editions were printed in 1927 and 1972 respectively. Since Eitner's first "modern" edition of ''L'Orfeo'' in 1884, and d'Indy's performing edition 20 years later—both of which were abridged and adapted versions of the 1609 score—there have been many attempts to edit and present the work, not all of them published. Most of the editions that followed d'Indy up to the time of the Second World War were arrangements, usually heavily truncated, that provided a basis for performances in the modern opera idiom. Many of these were the work of composers, includingCarl Orff

Carl Orff (; 10 July 1895 – 29 March 1982) was a German composer and music educator, best known for his cantata '' Carmina Burana'' (1937). The concepts of his Schulwerk were influential for children's music education.

Life

Early life

Carl ...

(1923 and 1939) and Ottorino Respighi in 1935. Orff's 1923 score, using a German text, included some period instrumentation, an experiment he abandoned when producing his later version.

In the post-war period, editions have moved increasingly to reflect the performance conventions of Monteverdi's day. This tendency was initiated by two earlier editions, that of Jack Westrup

Sir Jack Westrup (26 July 190421 April 1975) was an English Musicology, musicologist, writer, teacher and occasional conductor and composer.

Biography

Jack Allan Westrup was the second of the three sons of George Westrup, insurance clerk, of Dulw ...

used in the 1925 Oxford performances, and Gian Francesco Malipiero

Gian Francesco Malipiero (; 18 March 1882 – 1 August 1973) was an Italian composer, musicologist, music teacher and editor.

Life Early years

Born in Venice into an aristocratic family, the grandson of the opera composer Francesco Malipiero, G ...

's 1930 complete edition which sticks closely to Monteverdi's 1609 original. After the war, Hindemith's attempted period reconstruction of the work was followed in 1955 by an edition from August Wenzinger

August Wenzinger (1905–1996) was a prominent cellist, viol player, conductor, teacher, and music scholar from Basel, Switzerland. He was a pioneer of historically informed performance, both as a master of the viola da gamba and as a conductor of ...

that remained in use for many years. The next 30 years saw numerous editions, mostly prepared by scholar-performers rather than by composers, generally aiming towards authenticity if not always the complete re-creation of the original instrumentation. These included versions by Raymond Leppard

Raymond John Leppard (11 August 1927 – 22 October 2019) was a British-American conductor, harpsichordist, composer and editor. In the 1960s, he played a prime role in the rebirth of interest in Baroque music; in particular, he was one of the ...

(1965), Denis Stevens

Denis William Stevens CBE (2 March 1922 – 1 April 2004) was a British musicologist specialising in early music, conductor, professor of music and radio producer.

Early years

He was born in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire and attended the Royal ...

(1967), Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1969), Jane Glover

Dame Jane Alison Glover (born 13 May 1949) is a British-born conductor and musicologist.

Early life

Born at Helmsley, Glover attended Haberdashers' Monmouth School for Girls. Her father, Robert Finlay Glover, MA ( TCD), was headmaster of ...

(1975), Roger Norrington (1976) and John Eliot Gardiner

Sir John Eliot Gardiner (born 20 April 1943) is an English conductor, particularly known for his performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Life and career

Born in Fontmell Magna, Dorset, son of Rolf Gardiner and Marabel Hodgkin, Ga ...

. Only the composers Valentino Bucchi (1967), Bruno Maderna

Bruno Maderna (21 April 1920 – 13 November 1973) was an Italian conductor and composer.

Life

Maderna was born Bruno Grossato in Venice but later decided to take the name of his mother, Caterina Carolina Maderna.Interview with Maderna‘s th ...

(1967) and Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled '' Sequenza''), and for his pioneering work ...

(1984) produced editions based on the convention of a large modern orchestra. In the 21st century editions continue to be produced, often for use in conjunction with a particular performance or recording.

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

*''L'Orfeo'' libretto in Italian with English translation

''L'Orfeo'' libretto in German translation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Orfeo Operas by Claudio Monteverdi Pastoral operas Italian-language operas Operas 1607 operas Operas about Orpheus Operas based on Metamorphoses Proserpina