Khotyn Uprising on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Khotyn Uprising ( ro, Răscoala de la Hotin or ; uk, Хотинське повстання, Khotyns'ke povstannya) was a Ukrainian-led insurrection in the far-northern tip of

On March 3, the Treaty of Brest effectively meant that the UNR renounced its claims in northern Bessarabia to Austria. The former ''Khotinsky Uyezd'' was occupied by the

On March 3, the Treaty of Brest effectively meant that the UNR renounced its claims in northern Bessarabia to Austria. The former ''Khotinsky Uyezd'' was occupied by the

One of the first units to cross into Bessarabia was the garrison of a Ukrainian

One of the first units to cross into Bessarabia was the garrison of a Ukrainian

On February 2, guerilla units made a futile attempt to return at Khotyn through Atachi, prompting another retaliatory bombardment by Romanian artillery units, which consequently became a systematic response to any perceived agitation. This approach led to conciliatory displays by the UNR. That same day, its representatives issued orders for the returning rebels to disarm, and pledge to assist with the investigation into their activities. Podolia's Commissioner declared his conviction that Romanians had no aggressive intent, and acknowledged that they were justified to be in a "nervous mood", with ultimatums as an ultimate "bluff". On February 8, Davidoglu's men machine-gunned the urban center of

On February 2, guerilla units made a futile attempt to return at Khotyn through Atachi, prompting another retaliatory bombardment by Romanian artillery units, which consequently became a systematic response to any perceived agitation. This approach led to conciliatory displays by the UNR. That same day, its representatives issued orders for the returning rebels to disarm, and pledge to assist with the investigation into their activities. Podolia's Commissioner declared his conviction that Romanians had no aggressive intent, and acknowledged that they were justified to be in a "nervous mood", with ultimatums as an ultimate "bluff". On February 8, Davidoglu's men machine-gunned the urban center of  The

The

The UNR was dissolved upon the conclusion of its war with Russia in late 1921, leaving Khotyn and Bessarabia to be governed by Romania, directly on its closed border with the

The UNR was dissolved upon the conclusion of its war with Russia in late 1921, leaving Khotyn and Bessarabia to be governed by Romania, directly on its closed border with the

Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

region, nestled between Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

and Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

. It occurred on January 7–February 1, 1919, less than a year after Bessarabia's annexation by the Romanian Kingdom. The city it was centered on is now known as Khotyn

Khotyn ( uk, Хотин, ; ro, Hotin, ; see other names) is a city in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of western Ukraine and is located south-west of Kamianets-Podilskyi. It hosts the administration of Khotyn urban hromada, one of the ...

(Хотин), and is located in Chernivtsi Oblast

Chernivtsi Oblast ( uk, Черніве́цька о́бласть, Chernivetska oblast), also referred to as Chernivechchyna ( uk, Чернівеччина) is an oblast (province) in Western Ukraine, consisting of the northern parts of the reg ...

, Ukraine; in 1919, it was the capital of Hotin County

Hotin County was a county ( ținut is Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, județ after) in the Principality of Moldavia (1359–1812), the Governorate of Bessarabia (1812–1917), the Moldavian Democratic Republic (1917–1918), and the Kingdom o ...

, on the unofficial border between Romania and the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 19 ...

(UNR). The revolt was carried out by armed locals, mainly Ukrainian peasants, assisted by Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

deserters from the Ukrainian People's Army

The Ukrainian People's Army ( uk, Армія Української Народної Республіки), also known as the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) or as a derogatory term of Russian and Soviet historiography Petliurovtsy ( uk, Пет ...

and groups of Moldovans

Moldovans, sometimes referred to as Moldavians ( ro, moldoveni , Moldovan Cyrillic: молдовень), are a Romance-speaking ethnic group and the largest ethnic group of the Republic of Moldova (75.1% of the population as of 2014) and a s ...

, with some support from local Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and White Russians. It forms part of the Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

, though whether or not the UNR covertly supported it, beyond formally reneging it, is a matter of dispute. The role of Bolsheviks, which has been traditionally highlighted in Romanian and Soviet historiography

Soviet historiography is the methodology of history studies by historians in the Soviet Union (USSR). In the USSR, the study of history was marked by restrictions imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Soviet historiography i ...

alike, is similarly debated. The Khotyn Uprising is therefore ambiguously linked to the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

and the Ukrainian–Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War ( uk, радянсько-українська війна, translit=radiansko-ukrainska viina) was an armed conflict from 1917 to 1921 between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks (Soviet Ukraine and So ...

.

After days of guerilla activities by peasants, a large contingent of trained partisans crossed the Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

from UNR territory, and, on January 23, managed to capture the city, creating confusion among Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

garrisons. This group then formed a "Directorate", acting as Khotyn's unrecognized government. It aimed to change the status of the county, or of all Bessarabia, ahead of the Paris Peace Conference, but remained internally divided into pro-UNR and pro-Bolshevik factions. Within days, the Directorate was toppled by the returning Romanian Army under General Cleante Davidoglu, which also began a hunt for armed peasants. Critics of the intervention count 11,000 or more as killed during arbitrary shootings and shelling of localities on both banks of the Dniester, with 50,000 expelled. Romanian Army sources acknowledge that the repression was violent, while they may dispute the body count.

Participants in the revolt were generally alienated by the UNR's inaction, dividing themselves between the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

and the Whites. The Khotyn Uprising was closely followed by a raid on Tighina, carried out by the Bessarabian Bolshevik Grigory Kotovsky

Grigory Ivanovich Kotovsky (russian: Григо́рий Ива́нович Кото́вский, ro, Grigore Kotovski; – August 6, 1925) was a Soviet military and political activist, and participant in the Russian Civil War. He made a career ...

, whose forces came to include Khotyn veterans. Such incidents secured Bessarabia for Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

, seen by the Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

as a guarantee against communist revolution. In late 1919, the Armed Forces of South Russia

The Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR or SRAF) () were the unified military forces of the White movement in southern Russia between 1919 and 1920.

On 8 January 1919, the Armed Forces of South Russia were formed, incorporating the Volunteer Army ...

, coalescing various White entities, sketched out an attempt to invade Bessarabia, but lost ground to the Red Army. The emerging Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

continued to back partisans in Hotin County during the interwar, until annexing Bessarabia entirely in 1940.

Background

Before 1918

The Ukrainian claim to Khotyn (or Hotin) extends back to thePrincipality of Halych

The Principality of Halych ( uk, Галицьке князівство, translit=Halytske kniazivstvo; rus, Галицкое княжество; orv, Галицкоє кънѧжьство; ro, Cnezatul Galiția), or Principality of Halychian Ru ...

, with reports that Ukrainians had settled there before the lands fell to the Hungarian Kingdom

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. The city then belonged to the Principality of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centra ...

, which grew out of a Hungarian fief, before becoming a tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This to ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. T ...

began its incursions into Moldavia with the Pruth River Campaign

The Russo-Ottoman War of 1710—1711, also known as the Pruth River Campaign, was a brief military conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and the Ottoman Empire. The main battle took place during 18-22 July 1711 in the basin of the Pruth ri ...

of 1710–1711, prompting the Ottomans to annex Khotyn Fortress

The Khotyn Fortress ( uk, Хотинська фортеця, pl, twierdza w Chocimiu, tr, Hotin Kalesi, ro, Cetatea Hotinului) is a fortification complex located on the right bank of the Dniester River in Khotyn, Chernivtsi Oblast (province) ...

and reconstruct the corresponding Hotin County

Hotin County was a county ( ținut is Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, județ after) in the Principality of Moldavia (1359–1812), the Governorate of Bessarabia (1812–1917), the Moldavian Democratic Republic (1917–1918), and the Kingdom o ...

into a distinct '' raya'' in 1714. The city was finally absorbed into Russia following the Bucharest Treaty of 1812, during which time it was recognized by all parties as being distinct from Bessarabia-proper. A census conducted five years later reported that 7,000 " Ruthenian" families had been colonized into the area by Russia. Immigration continued at a steady pace, and was in large part a private enterprise, with hired hands needed for the "immense estates" of Moldo-Bessarabian boyars. By 1900, Ukrainians were a likely majority of the area's population, although no definitive count exists. According to historian Nicolae Enciu, in 1918 there were 121 all-Ukrainian villages, 52 all- Romanian, and 16 mixed. Khotyn town was populated by Bessarabian Jews, though accounts differ on their number, from a vast majority to a fifth of the inhabitants.

Under Russian rule, Hotin County was incorporated with the Bessarabia Governorate

The Bessarabia Governorate (, ) was a part of the Russian Empire from 1812 to 1917. Initially known as Bessarabia Oblast (Бессарабская область, ''Bessarabskaya oblast'') as well as, following 1871, a governorate, it included t ...

, as ''Khotinsky Uyezd Khotinsky Uyezd (''Хотинский уезд'') was one of the subdivisions of the Bessarabia Governorate of the Russian Empire. It was situated in the northwestern part of the governorate. Its administrative centre was Khotyn (''Khotin'').

Demog ...

''. Its assembly, or ''Zemstvo

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander ...

'', overrepresented Russian nobility

The Russian nobility (russian: дворянство ''dvoryanstvo'') originated in the 14th century. In 1914 it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members (about 1.1% of the population) in the Russian Empire.

Up until the February Revolution ...

, in particular the rival Krupensky and Lisovsky families; in 1900, it was dominated by members of the former, including Alexander N. Krupensky. Its control was looser from 1912, when the ''Zemstvo'' presidency went to a Romanian nationalist, Dimitrie A. Ouatul. Russian dominance was again being challenged during World War I, when the northern areas of Hotin were a devastated battlefield, along with the neighboring Duchy of Bukovina

The Duchy of Bukovina (german: Herzogtum Bukowina; ro, Ducatul Bucovinei; uk, Герцогство Буковина) was a constituent land of the Austrian Empire from 1849 and a Cisleithanian crown land of Austria-Hungary from 1867 until 1918. ...

. The latter was an extension of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

, which envisioned annexing Khotyn upon defeating Russia and Romania. Following the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

, Ouatul became Commissar for Khotyn, appointed by the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

. His attempt to reassert control was ineffectual, as previously disenfranchised social groups began forming their own soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

and refusing to abide by central laws. These soviets decreed the socialization

In sociology, socialization or socialisation (see spelling differences) is the process of internalizing the norms and ideologies of society. Socialization encompasses both learning and teaching and is thus "the means by which social and cul ...

of all landed estates.

The Provisional Government fell during the November Revolution, which left Bessarabia and Khotyn with an uncertain status. Bessarabia formally reorganized itself into an autonomous Moldavian Democratic Republic

The Moldavian Democratic Republic (MDR; ro, Republica Democratică Moldovenească, ), also known as the Moldavian Republic, was a state proclaimed on by the '' Sfatul Țării'' (National Council) of Bessarabia, elected in October–Novemb ...

(RDM), headed by the former Russian envoy, Ion Inculeț. Inculeț himself noted that the region, including Khotyn, needed to be defended from Romanian and Ukrainian separatism, and remain attached to a Russian Federated Republic. He cited "devastation in the land of Hotin" as one of the main reasons for establishing a regional government. Ten cohorts of the newly formed Bessarabian Army were ordered to resume control of the region.

Also newly proclaimed, the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 19 ...

(UNR) issued claims to the whole of Bessarabia or to Khotyn area as early as July 1917, but also maintained friendly relations with the RDM and Romania. Romanian Premier Ion I. C. Brătianu, who still hoped to maintain the Moldavian Front against encroachment by the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, intended to bring the new regime to his side. By January 1918, the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

spread out along the Siret River

The Siret or Sireth ( uk, Сірет or Серет, ro, Siret , hu, Szeret, russian: Сирет) is a river that rises from the Carpathians in the Northern Bukovina region of Ukraine, and flows southward into Romania before it joins the Danube. ...

had divided itself into Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and UNR loyalists—the latter helped Romanian authorities by repressing the former. The Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

sought both RDM and UNR approval for its subsequent incursion into Bessarabia, where it helped neutralize Bolshevik centers. In the event, the UNR agreed to recognize the RDM, but made specific claims to Hotin and Cetatea Albă counties. Meanwhile, rival claims on the region were made by both the White movement and Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, both of which fomented dissent among local Ukrainians.

In the elections of November 1917, opponents of the UNR in Hotin County had chosen Nicolae Bosie-Codreanu, Nicolae Cernăuțeanu, and Constantin Iurcu as their delegates to the Bessarabian people's assembly, or ''Sfatul Țării

''Sfatul Țării'' ("Council of the Country"; ) was a council that united political, public, cultural, and professional organizations in the greater part of the territory of the Governorate of Bessarabia in the disintegrating Russian Empire, w ...

''. In December, Ukrainian soldiers from the 10th Army Corps expressed a contrary wish, declaring that Khotyn needed to be included in the UNR. A UNR diplomat, Otto Eichelmann, argued that there were no Hotin representatives on show in March 1918, when this legislature voted in favor of union with Romania; nevertheless, ''Sfatul'' resolutions made specific reference to unified Bessarabia as extending "from Hotin to Ismail

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

". Following the Eleven Days' War against Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, including Austria, could impose these borders on their defeated adversaries. The Romanian presence in Bessarabia, which coincided with the start of a working alliance between the UNR and the Central Powers, stood as a "clue that omanianstoo are out of the war with the Central Powers." Trilateral peace negotiations began in February, when Austria announced Romanian diplomats that the Bessarabian question

The Bessarabian question, Bessarabian issue or Bessarabian problem ( ro, Problema basarabeană or ; russian: Бессарабский вопрос or ) is the name given to the controversy over the ownership of the geographic region of Bessarabia ...

was largely irrelevant to the Central Powers: "the essarabianquestion is to be solved directly between Romania, which occupies it militarily, and the Ukrainian and Moldavian republics".

Austrian–Romanian–Ukrainian dispute

Royal Hungarian Honvéd

The Royal Hungarian ( hu, Magyar Királyi Honvédség) or Royal Hungarian (german: königlich ungarische Landwehr), commonly known as the (; collectively, the ), was one of the four armed forces (german: Bewaffnete Macht, links=no or ) of ...

, on behalf of Austria, that same month. Hungarians controlled the county down to (and including) Ocnița

Ocnița (; russian: Óкница) is a town and the administrative center of Ocnița District, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern E ...

, as well as the northern extremity of Soroca County; under the terms of an armistice, the Romanian Army held on to the remaining areas, including 8 villages in Hotin. Early the following month, the Bukovinan Romanian Ion Nistor

Ion I. Nistor (August 16, 1876 – November 11, 1962) was a Romanian historian and politician. He was a titular member of the Romanian Academy from 1915 and a professor at the universities of Cernăuți and Bucharest, while also serving as Mini ...

invited civilians, including those of Hotin, to "stand guard on the old border, as your grandparents and ancestors before you". On April 14, 1918, Romanian and RDM officials set up a border crossing at Otaci

Otaci (formerly Ataki, Russian Атаки) is a town (population 8,400) on the southwestern bank of the Dniester River, which at that point forms the northeastern border of Moldova. On the opposite side of the Dniester lies the Ukrainian city of ...

, east of Hotin area and further downstream on the Dniester

The Dniester, ; rus, Дне́стр, links=1, Dnéstr, ˈdⁿʲestr; ro, Nistru; grc, Τύρᾱς, Tyrās, ; la, Tyrās, la, Danaster, label=none, ) ( ,) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and th ...

. UNR–Romanian relations grew more hostile over those days, with rumors emerging that the Ukrainian side had formally protested against the Romanian presence in Bessarabia.

In early May, a new Romanian government, headed by Alexandru Marghiloman

Alexandru Marghiloman (4 July 1854 – 10 May 1925) was a Romanian conservative statesman who served for a short time in 1918 (March–October) as Prime Minister of Romania, and had a decisive role during World War I.

Early career

Born in Bu ...

, agreed to sign peace with the Central Powers. Although Marghiloman went into the negotiations promising that "under no circumstances would we lose Hotin", the act ceded 600 square kilometer

Square kilometre ( International spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures) or square kilometer (American spelling), symbol km2, is a multiple of the square metre, the SI unit of area or surface area.

1 km2 is equa ...

s of land to Austrian Bukovina, including parts of the county, alongside the neighboring Hertsa region

The Hertsa region, also known as the Hertza region ( uk, Край Герца, Kraj Herca; ro, Ținutul Herța), is a region around the town of Hertsa within Chernivtsi Raion in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, n ...

. Under the resulting regime, parts of Hotin that were either annexed or occupied by Austria were exploited, as a breadbasket for the peoples of Austria-Hungary. This tactic, which was enforced with Marghiloman's acquiescence, led to severe shortages by June 1918. Within months, the Hungarian military administration dissolved all soviets and offices answering to the Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Council of Ukraine ( uk, Українська Центральна Рада, ) (also called the Tsentralna Rada or the Central Rada) was the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputie ...

, only delegating authority to the reestablished ''Zemstvo''. Faced with such constraints, local Ukrainians began organizing into partisan units.

In April, the UNR itself was replaced by a more Austrian- and White-friendly regime, the Hetmanate, which made some efforts to extend itself into Hotin County and the "four parishes" of Soroca. A branch of the Ukrainian Army, including a 2nd Cavalry Division under Commandant Kolesnikov, was established in Khotyn, whose civilian authorities argued that Marghiloman had willingly renounced his claims to the area. On May 26, judge Oleksa Suharenko was appointed Khotyn's '' Starosta'' by authorities from the Podolian Governorate

The Podolia Governorate or Podillia Governorate (), set up after the Second Partition of Poland, was a governorate (''gubernia'', ''province'', or ''government'') of the Russian Empire from 1793 to 1917, of the Ukrainian People's Republic from 1 ...

, situated across the Dniester; he never took charge, as he was soon replaced by a P. Izbytskyi. The Austrian authorities ultimately consented to Izbytskyi's arrival, but stripped him of any real power. By July 1918, Romanians grew alarmed about reports that Hetmanate representatives, including Oleksander Shulhyn

Oleksander Yakovych Shulhyn ( uk, Олександр Шульгин; russian: Александр Шульгин; french: Alexandre Choulguine) was a prominent political, public, scientific and cultural figure of Ukraine and the Ukrainian governmen ...

, were seeking to annex Bessarabia in its entirety.

In November 1918, Germany's armistice changed the course of politics in the region. The unification of Bessarabia with Romania became effective the same month, when regional autonomy was dissolved. In Hotin County, control had remained notional until late autumn: on October 22, 1918, a majority of the ''Zemstvo'' voted in favor of the county's reunification with Russia, voicing their fear that the Romanian Army's presence in Bessarabia would end with annexation. As his final act in government, Marghiloman ordered his troops to take Hotin and Bukovina, together. The 1st Romanian Cavalry Division, part of the Fifth Army, moved into the former region; it was spearheaded by the 3rd Redcoats Regiment and the 40th Infantry Regiment, both of which were placed under General Cleante Davidoglu. ''Starosta'' Izbytskyi advised the local militia not to oppose the Romanian incursion.

Khotyn was ceded by the Austrians on the evening of November 10. Soon after taking over, the Romanian garrison was joined by the 3rd Border Guards Regiment, responding to "alarmist claims" about "Bolshevik" concentrations on the Dniester. A one-kilometer exclusion zone was enforced around the city, food was requisitioned, and the population was ordered to hand in all weapons and ammunition. Davidoglu also announced the swift and exemplary execution of a man from Lipcani "who incited the soldiers to Bolshevism". The incursion also touched Mohyliv-Podilskyi

Mohyliv-Podilskyi (, , , ) is a city in the Mohyliv-Podilskyi Raion of the Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine. Administratively, Mohyliv-Podilskyi is incorporated as a town of regional significance. It also serves as the administrative center of Mohyli ...

, on the Dniester's left bank, pacified by Romanian troops by request of the Ukrainian mission in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

. On November 20, Izbytskyi registered his protest with General Davidoglu and Redcoats Colonel Gheorghe Moruzzi, reaffirming his belief that Khotyn city was a "territory of the Ukrainian state". He had by then been ordered to leave the county, and was issuing his official acts from across the river, in Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi ( uk, Ка́м'яне́ць-Поді́льський, russian: Каменец-Подольский, Kamenets-Podolskiy, pl, Kamieniec Podolski, ro, Camenița, yi, קאַמענעץ־פּאָדאָלסק / קאַמעניץ, ...

. In his own proclamation from Khotyn, Davidoglu insisted that "Bessarabia was a Romanian province until 1812, and it remains Romanian land today and forever", warning those who disagreed with him that they could leave for Podolia.

In December, the UNR was reestablished, and its leaders resumed their observation of Romanian activities in Hotin County. Its Directorate heard reports according to which "all peasant, provincial, county and even district congresses" supported the notion that Khotyn belonged in a Greater Ukraine. UNR sources describe late 1918 as marked by a "terror policy", including "shootings of mostly innocent people, the torture of women, children and the elderly, looting, bullying and violence against women nda broad system of denunciation". Ukrainian peasants on the Romanian side of the border were additionally troubled by the newly adopted land reform legislation, which returned some land to owners that local soviets had dispossessed, and made other plots subject to ransom.

Reports by UNR Podolian officials noted that by December "gangs of Moldovans

Moldovans, sometimes referred to as Moldavians ( ro, moldoveni , Moldovan Cyrillic: молдовень), are a Romance-speaking ethnic group and the largest ethnic group of the Republic of Moldova (75.1% of the population as of 2014) and a s ...

", assisted by the Ukrainians of Stara Ushytsia, made random attacks on Romanian border guards across the Dniester. Following one such killing, Romanian artillery shelled Stara Ushytsia on December 24. UNR officials initially agreed with Davidoglu that these were "bandit" raids. They became reluctant when Romanians presented them with an ultimatum to hand in those responsible, and were further alienated when Romanian troops beat up an UNR border guard at Zhvanets. However, on January 5, they refused to acknowledge an appeal by the "Bessarabian National Union", which asked for intervention in support of Hotin County refugees. Instead, Khotyn's inhabitants found support from the Committee for the Salvation of Bessarabia, which reunited Russian nationalists

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early ...

associated with the Whites. With funds received from the Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army (russian: Добровольческая армия, translit=Dobrovolcheskaya armiya, abbreviated to russian: Добрармия, translit=Dobrarmiya) was a White Army active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from ...

, ''Polkovnik

''Polkovnik'' (russian: полковник, lit=regimentary; pl, pułkownik) is a military rank used mostly in Slavic-speaking countries which corresponds to a colonel in English-speaking states and oberst in several German-speaking and Scandin ...

'' Zhurari began the training of guerillas at Tiraspol

Tiraspol or Tirișpolea ( ro, Tiraspol, Moldovan Cyrillic: Тираспол, ; russian: Тира́споль, ; uk, Тирасполь, Tyraspol') is the capital of Transnistria (''de facto''), a breakaway state of Moldova, where it is the ...

.

Unfolding

According toTransnistria

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is an unrecognised breakaway state that is internationally recognised as a part of Moldova. Transnistria controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester riv ...

n academic Piotr Șornikov, Zhurari and his Committee planned for the rebellion to ignite just before the Paris Peace Conference, which was to analyze the issue of Bessarabia and Khotyn. Romanian rule was still consolidating when the armed rebellion began. Scholar Svetlana Suveică notes that the earliest signs of trouble came on the day set for Old-Style Christmas—January 7, 1919. Ukrainian historian Oleksandr Valentynovych Potylchak notes that "the uprising had an international character: both Ukrainians and Moldovans fought in the rebels' ranks." The first attested partisan leader was a Moldovan, known as Gheorghe or Grigore Bărbuță. The representation of ethnicities other than Ukrainians is nevertheless qualified by other authors. Among those whose names were later advanced as "leaders of the revolt", very few were ethnically Romanian or Moldovan. Van Meurs analyzes two lists, respectively provided by V. Lungu and the '' Moldavian Soviet Encyclopedia'', counting 1/8 Romanians or Moldovans in the former, and 3/16 in the latter. Examples noted by the author include Nikifor Adazhyi, D. S. Ciobanu, and I. S. Lungu. Historian M. C. Stănescu additionally describes Leonid Yakovych Tokan (or Toncan) as a Romanian by origin and a priest by training.

Romanian Army historian Ion Giurcă sees Davidoglu as ill-suited for the task of maintaining order, in that he failed to anticipate the subsequent incursion. Stănescu similarly notes that Davidoglu and his aide, Colonel Carol Ressel, "did not consolidate heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Official ...

positions", despite being informed of troop movements near Mohyliv. On January 19, Podolian irregulars crossed into Hotin County at Atachi, disarming Romanian border guards and moving in on Soroca

Soroca (russian: link=no, Сороки, Soroki, uk, Сороки, Soroky, pl, Soroki, yi, סאָראָקע ''Soroke'') is a city and municipality in Moldova, situated on the Dniester River about north of Chișinău. It is the administrative ...

. Historian Wim van Meurs describes this attempt as "Bessarabian peasants ..attempt ngto capture the bridge across the Dniester in order to smuggle arms into Bessarabia." These reinforcements succeeded in taking over a string of villages, including Arionești, Codreni, Naslavcea, Pocrovca, and Rudi; on January 23, after reaching Secureni, rebellion erupted in Khotyn itself, chasing out the Romanian garrison.

Two days earlier, most of Davidoglu's units had been dispersed to chase the rebels in surrounding villages, which, as Giurcă notes, only gave impetus to an "uprising of the hostile population". The fall of Khotyn came as he had retreated to Nedăbăuți, and planning further moves toward Noua Suliță

Novoselytsia ( ; ro, Noua Suliță ; yi, נאוואסעליץ, Novoselitz) is a city in Chernivtsi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast (province) of Ukraine. It stands at the northern tip of Bessarabia region, on its border with Bukovina. It hosts the ad ...

, for fear that guerillas were in control of all surrounding villages. Both Noua Suliță and Nedăbăuți fell to the rebels shortly after, and a Redcoats brigade, under General Mihai Schina, made repeated attempts to regain them. In the ensuing confusion, various targeted attacks killed Romanian Army officers, including Gheorghe Madgearu in Volcineți and General Stan Poetaș in Călărășeuca. The latter assassination is directly attributable to Bărbuță's unit.

As early as January 19, the rebels had formed a Bessarabian Directorate, stemming from the Bessarabian National Union, with both of them provisionally located in Kamianets. At that moment in time, the Directorate is known to have comprised five men: Tokan, Ivan Stepanovych Dunger, M. F. Liskun, Evhen V. Lisak, and I. I. Mardariev. Three days later, one of the groups involved issued an appeal to the international community, including both Soviet Russia and the UNR, which referred to the sufferings of the "Bessarabian people" and to the Directorate as a legitimate government of Bessarabia. A similar text warned that all those "campaigning against the Directorate and against freedom from the Romanian yoke" would be shot, alongside rioters and looters. The Directors had by then deposed and arrested Khotyn's Mayor, Gachikevich (or Gocicherie), ordering the city population to pay them 1.5 million ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble ( Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''ru ...

s within three days. Most of this burden fell on the local Jews, whom the rebels openly threatened with violence. Romanian writer Constantin Kirițescu further argues that the rebels committed war crimes against Romanian captives, including hanging or eviscerating regular soldiers and lynching a local chief of the ''Siguranța

Siguranța was the generic name for the successive secret police services in the Kingdom of Romania. The official title of the organization changed throughout its history, with names including Directorate of the Police and General Safety ( ro, Di ...

''. Jews felt solidarity with the Romanian soldiers and border guards, some of whom were allowed to hide in Khotyn's synagogues.

Activists were already disunited: right-wingers proposed to create a "Republic of Little Bukovina", centered on Khotyn and opened to annexation by the UNR; leftists urged instead for the formation of a "Bessarabian Democratic Republic", which, as historian Ion Gumenâi argues, would have implicitly functioned as an extension of Soviet Russia. The latter current was illustrated by Iosip Voloshenko-Mardariev, a schoolteacher-turned-activist. Șornikov summarizes this clash of visions within the movement as a "split of patriotic forces into Whites and Reds", with partisans of Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revo ...

and "Little Bukovina" reportedly forming a majority of the Directorate. On January 25, this council, presided upon by Ivan F. Liskun and Tokan, claimed control over 100 localities in Hotin County, and all of what became the Khotyn Raion

Khotyn Raion ( uk, Хотинський район) was an administrative raion (district) in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in western Ukraine, on the Romanian border. It was part of the historical region of Bessarabia. The administrativ ...

. The rebel force grew from 2,000 to 30,000 recruits. Styled "Bessarabian People's Army", it formed three regiments: cavalry ( Rucșin), artillery (Anadol

Anadol was Turkey's first domestic mass-production passenger vehicle company. Its first model, Anadol A1 (1966–1975) was the second Turkish car after the ill-fated Devrim sedan of 1961. Anadol cars and pick-ups were manufactured by Otosan O ...

), and self-defense units ( Dăncăuți). A man by the name of Filipchuk was general commander of this force, with Konstantin Shynkarenko serving under him, as leader of Dăncăuți's regiment.

One of the first units to cross into Bessarabia was the garrison of a Ukrainian

One of the first units to cross into Bessarabia was the garrison of a Ukrainian armored train

An armoured train is a railway train protected with armour. Armoured trains usually include railway wagons armed with artillery, machine guns and autocannons. Some also had slits used to fire small arms from the inside of the train, a facil ...

, which had placed itself under the command of a Bessarabian sailor, Georgy Muller. I. Liskun had reached the area after having served as governor of Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

the previous month. As reported in Ukrainian sources, he had deserted from the Ukrainian People's Army

The Ukrainian People's Army ( uk, Армія Української Народної Республіки), also known as the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) or as a derogatory term of Russian and Soviet historiography Petliurovtsy ( uk, Пет ...

(UNA) when ordered not to lead his troops over the Dniester. His ''Haidamaka

The haidamakas, also haidamaky or haidamaks (singular ''haidamaka'', ua, Гайдамаки, ''Haidamaky'') were Ukrainian paramilitary outfits composed of commoners (peasants, craftsmen), and impoverished noblemen in the eastern part of th ...

'' relied on civilian support, and on several occasions returned into Podolia to raid UNR garrisons for cannons and supplies. Some accounts suggest that members of the UNR's 7th Infantry Regiment had crossed into Bessarabia by the hundreds from January 22. However, these troops had been demobilized after disagreements with the Directorate, and had embraced Bolshevik ideals, rallying under a red flag. Towards its very end, the uprising was apparently led by an UNR politician, I. Siyak. Whether or not UNR ''Ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; Russian: атаман, uk, отаман) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military comman ...

'' G. I. Mayevski also contributed to this expedition remains a topic of contention. Historian Ion Gumenâi sees him as an actual commander of the rebel troops; a similar verdict was advanced by a collective of authors from the State Archives of Chernivtsi

Chernivtsi ( uk, Чернівці́}, ; ro, Cernăuți, ; see also other names) is a city in the historical region of Bukovina, which is now divided along the borders of Romania and Ukraine, including this city, which is situated on the ...

, who suggest that Mayevski distributed arms to the Bessarabian Directorate. Potylchak favorably quotes academic and UNR political figure Dmytro Doroshenko

Dmytro Doroshenko ( uk, Дмитро Іванович Дорошенко, ''Dmytro Ivanovych Doroshenko'', russian: Дми́трий Ива́нович Дороше́нко; 8 April 1882 – 19 March 1951) was a prominent Ukrainian political fig ...

denying that the revolt had any assistance from Mayevski.

Scholar Jonathan Smele argues that the UNR, "at a critical point of the Soviet–Ukrainian War, could not afford to become embroiled in conflict with Romania". An explicit order from the UNR General Staff banned the Podolia Army Corps from intervening to assist the uprising. In his memoirs, however, Doroshenko hints that the UNR's 60th Infantry Regiment was moved to Zhvanets specifically in order to help the rebel expedition, or at least to cover its retreat in case of a Romanian counterattack. Stănescu claims that the UNA directly assisted the rebels with constructing a makeshift bridge at Ocnița. Major M. McLaren of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, who was mistakenly arrested by the rebels as a Romanian spy, reports that no UNA troops were on show, though noting the passing presence of Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

with an undisclosed allegiance. Ukrainian officials strongly disavowed rebels when they transported 6 Romanian prisoners into UNR territory. Their reaction was not registered by the Romanian Army, who responded by capturing 16 Free Cossacks from Tiraspol as hostages.

Violent repression

Overall, Liskun's incursion was quickly rejected by the returning Romanian Army. In the early stages of the rebellion, it acted out on its previous warnings, repeatedly shelling the Podolian villages of Nahoriany and Kozliv. During this interval, Davidoglu's troops were joined by various units, including the entire 37th Infantry Regiment, which moved fromBacău

Bacău ( , , ; hu, Bákó; la, Bacovia) is the main city in Bacău County, Romania. At the 2016 national estimation it had a population of 196,883, making it the 12th largest city in Romania. The city is situated in the historical region o ...

to Noua Suliță, and the machine-gunners of Bălți

Bălți (; russian: Бельцы, , uk, Бєльці, , yi, בעלץ ) is a city in Moldova. It is the second largest city in terms of population, area and economic importance, after Chișinău. The city is one of the five Moldovan municipalit ...

. On January 28–30, the regrouped units, under Colonel Victor Tomoroveanu, forced rebels out of Noua Suliță, Nedăbăuți, Dăncăuți and Cliscăuți, reaching Anadol; other groups retook Rucșin and Rașcov. A state of siege was imposed in neighboring Bukovina, before troops from there could be marched into Hotin County; "already on February 1, the insurgent forces were pushed back over the Dniester, and internal rebellions were repressed". A force still answering to the Khotyn Directorate was able to cross the Dniester back into Podolia, reportedly "without losses".

From January 28, the intervention was nominally led by Nicolae Petala, who had taken over from Davidoglu. However, Davidoglu could not be replaced in time, and, with his aide Ressel, was the one to actually take Khotyn; they had already received orders to quell any incursion or revolt "with the greatest violence, including the complete destruction of any ebel

Ebel is a Swiss luxury watch company that was founded in 1911 at La Chaux-de-Fonds in the canton of Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

History

Ebel was established in 1911 by Eugène Blum and his wife, Alice (née Lévy). The brand name originates from t ...

locality". Davidoglu is therefore widely seen as responsible for the bloody interlude which followed. Although Giurcă believes that Davidoglu acted "within the confines of wartime regulations", fellow generals, including Ion Antonescu

Ion Antonescu (; ; – 1 June 1946) was a Romanian military officer and marshal who presided over two successive wartime dictatorships as Prime Minister and ''Conducător'' during most of World War II.

A Romanian Army career officer who ma ...

, criticized his random killing of civilians, noting that it enshrined Romania's negative image as a "country of savages".

Some such reports concentrate on looting, since Romanian troops were generally ill-prepared for a wintertime action, lacking any winter clothing. Nicolae Coroiu of the 37th Regiment recalls that Davidoglu informed his soldiers to shoot down any armed homeowners and burn down their houses, then "dress up in the clothes of the offending parties." Coroiu recalls however that his troops did not shoot to kill, allowing wounded civilians to flee for safety. General Constantin Prezan

Constantin Prezan (January 27, 1861 – August 27, 1943) was a Romanian general during World War I. In 1930 he was given the honorary title of Marshal of Romania, as a recognition of his merits during his command of the Northern Army and of the ...

, Chief of the Romanian General Staff

The Chief of General Staff ( ro, Șeful Statului Major General) is the highest professional military authority in the Romanian Armed Forces. He is appointed by the President of Romania, at the National Defense Minister's proposal (with the appro ...

, approved of the violence, having issued orders that the peaceful civilians be protected, whereas "no pity, no tolerance should be displayed" toward rebels. General Schina's initial proclamations called on local Russians and Moldovans to act as "Christians and good Romanians ..for there is no sweeter, gentler and more protective country on this earth than the land of Romanians." When confronted with reports of rebel atrocities, Schina pressured Davidoglu to "corral every village, all Bolshevik gangs and rebellious inhabitants"; if rebel activities continued, he was to set whole localities on fire.

Stănescu, relying on "Romanian military documents", notes that "during the aggression they initiated, the Bolsheviks had about 300–400 dead, with several localities whose population had supported them in their actions being destroyed in whole or in part." Other Romanian military records, republished by Potylchak, boasted that seven rebel villages were burned to the ground, with as many as 5,000 insurgents killed; Potylchak himself counts 22 villages destroyed and 11,000 victims, including arbitrary executions of 165 railwaymen and 500 unarmed civilians. He also notes that estimates of 15,000 and higher are probably exaggerated. The latter claim is qualified in Smele's account: "Ukrainian sources suggest that ..at least 15,000 of those who did not flee were slaughtered by the Romanians." Similar numbers are advanced by Mikhail Meltyukhov, who concludes that "according to official Romanian data, more than 5,000 were killed", and that "15,000 people suffered in one form or another". Scholars I. P. Fostoy and V. M. Podlubny also report 160 railway workers being killed, one of them through immolation

Immolation may refer to:

*Death by burning

*Self-immolation, the act of burning oneself

*Immolation (band), a death metal band from Yonkers, New York

*'' The Immolation'', a 1977 novel by Goh Poh Seng

*'' Dance Dance Immolation'', an interactive p ...

. They note that the 11,000 total can be traced to an estimate first publicized by the International Red Aid

International Red Aid (also commonly known by its Russian acronym MOPR ( ru , МОПР, for: ''Междунаро́дная организа́ция по́мощи борца́м револю́ции'' - Mezhdunarodnaya organizatsiya pomoshchi bor ...

in 1925. Romanian losses, meanwhile, amounted to 369; this includes 159 killed in action, 93 wounded, and a further 117 missing.

Some murders of civilians are described in Romanian sources. According to Lieutenant Gheorghe Eminescu, his colleague, Captain Mociulschi, shot a railway signalman held responsible for assisting the partisans with their raid on Ocnița. The measures were observed by McLaren and two other British officers touring the UNR; one of them is identified by Stănescu as Lieutenant Edwin Boxhall of Naval Intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from ...

. According to Giurcă, they favored the UNR and "Ukrainian Bolshevik troops", with reports which exaggerated the scale of repression and victimized non-Romanians, in particular Jews caught between the two sides. Petala, who was ordered to investigate Davidoglu, suggested that the McLaren group were of "doubtful good faith". Likewise, Stănescu reads the British report as a "complete denaturation", with "Bolsheviks" being depicted as "victims of Romanian repressions."

Interrogated by the Romanian side, McLaren noted that Khotyn had been shelled by the Romanians until a civilian delegation had declared it an open city

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open the opposing military will be ...

. The occupiers, he recalled, had engaged in widespread looting and "barbaric" beatings. He recalled witnessing one botched execution, in which a suspected robber was left to agonize for hours, as well as the shooting of 53 peasants in Nedăbăuți. According to his reports, several boys and old men were shot during robberies condoned by Davidoglu, while a man of unspecified age, Nikita Zankovsky, was bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustra ...

ted in front of his family. Similar accounts mention other acts of cruelty, including at Rucșin, where Major Popescu shot 12 captives after forcing them to dig their own grave, also killing any disabled men he found in civilian homes.

By contrast, Coroiu reports that the one robber to be executed in Khotyn was a Romanian sergeant, caught looting despite an explicit ban. McLaren's account also conflicted with a testimony by Khotyn's deposed mayor, who had been imprisoned alongside the British officers. Gachikevich argued that local Jews appreciated the restoration of order, and that Romanians "caused no harm, other than a few incidents on the city's outskirts." His report was backed by similar statements from two of Khotyn's rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s, Samuel Haiss and Nahiev Ițikovici, the former of whom also expressed his thanks in a letter to King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the t ...

Ferdinand I of Romania

Ferdinand (Ferdinand Viktor Albert Meinrad; 24 August 1865 – 20 July 1927), nicknamed ''Întregitorul'' ("the Unifier"), was King of Romania from 1914 until his death in 1927. Ferdinand was the second son of Leopold, Prince of Hohenzollern an ...

. The McLaren issue was escalated to General Prezan, who asked and obtained that the three British envoys be expelled from Bessarabia.

Revivals

Raid on Tighina

On February 2, guerilla units made a futile attempt to return at Khotyn through Atachi, prompting another retaliatory bombardment by Romanian artillery units, which consequently became a systematic response to any perceived agitation. This approach led to conciliatory displays by the UNR. That same day, its representatives issued orders for the returning rebels to disarm, and pledge to assist with the investigation into their activities. Podolia's Commissioner declared his conviction that Romanians had no aggressive intent, and acknowledged that they were justified to be in a "nervous mood", with ultimatums as an ultimate "bluff". On February 8, Davidoglu's men machine-gunned the urban center of

On February 2, guerilla units made a futile attempt to return at Khotyn through Atachi, prompting another retaliatory bombardment by Romanian artillery units, which consequently became a systematic response to any perceived agitation. This approach led to conciliatory displays by the UNR. That same day, its representatives issued orders for the returning rebels to disarm, and pledge to assist with the investigation into their activities. Podolia's Commissioner declared his conviction that Romanians had no aggressive intent, and acknowledged that they were justified to be in a "nervous mood", with ultimatums as an ultimate "bluff". On February 8, Davidoglu's men machine-gunned the urban center of Mohyliv-Podilskyi

Mohyliv-Podilskyi (, , , ) is a city in the Mohyliv-Podilskyi Raion of the Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine. Administratively, Mohyliv-Podilskyi is incorporated as a town of regional significance. It also serves as the administrative center of Mohyli ...

, killing two. Before the end of the month, they destroyed all bridges on the upper Dniester, to ensure that communications between Ukrainian groups were rendered more difficult. While Petala asked to command an expeditionary force that would establish a bridgehead in Podolia, Prezan continued to discuss the matter with UNR authorities, warning them to disarm any groups still hiding on the Dniester.

Zhurari's Whites in Tiraspol attempted to provide assistance to the rebels, but moved in too late. In early February, they reportedly acted as negotiators between armed Bolsheviks, led by the Bessarabian Grigory Kotovsky

Grigory Ivanovich Kotovsky (russian: Григо́рий Ива́нович Кото́вский, ro, Grigore Kotovski; – August 6, 1925) was a Soviet military and political activist, and participant in the Russian Civil War. He made a career ...

, and the UNR authorities, allowing the latter to withdraw peacefully from Tiraspol. Kotovsky was then pushed out by French troops of the 58th Infantry Regiment, and found himself crossing into Bessarabia, where he managed to chase Romanian soldiers out of Tighina. A French–Romanian division-strength force, assisted by the Polish Blue Army, stepped in to repel Kotovsky's partisans, and reoccupied Tiraspol. Zhurari's men declared their neutrality, but nevertheless found themselves labeled as enemy troops by the French army command; they then joined the intervention forces and participated in political repression, executing among others the father of Bolshevik leader Pavel Tcacenco

Pavel Tcacenco or Tkachenko (russian: Павел Дмитриевич Ткаченко; born Yakov Antipov or Antip, russian: Яков Яковлевич Антипов; 7 April?, 1892/1899/1901 – 5 September 1926) was an Imperial Russian-born ...

.

The Khotyn Uprising coincided with the final stages of the Soviet Russian offensive into the UNR's territory, which also led to the establishment of a subordinate Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

. On January 25, the latter's Premier, Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgievich Rakovsky (russian: Христиа́н Гео́ргиевич Рако́вский; bg, Кръстьо Георги́ев Рако́вски; – September 11, 1941) was a Bulgarian-born socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevi ...

, had effectively declared war on Romania by stating a Ukrainian Bolshevik claim to both Bessarabia and Bukovina. By contrast, UNR Directors openly rejected "territorial maximalism", in hopes to obtain weapons from Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

; these were promised, but never actually arrived. In March 1919, the Directorate moved to Husiatyn

Husiatyn ( uk, Гусятин; yi, הוסיאַטין, Husyatin) is an urban-type settlement in Chortkiv Raion, Ternopil Oblast (province) in western Ukraine. Alternate spellings include Gusyatin, Husyatin, and Hsiatyn. It hosts the administratio ...

, and failed to maintain a grip on Podolia. The area came to be governed by the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party

Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary Party (russian: Украинская партия социалистов-революционеров uk, Українська Партія Соціалістів-Революціонерів) was a political ...

(allegedly answering to Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky ( uk, Михайло Сергійович Грушевський, Chełm, – Kislovodsk, 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figu ...

), though military control was resumed after a counter-coup. In Dunaivtsi Raion, veterans of the Khotyn Uprising formed a Bessarabian Brigade, which restated its alliance with Russia and commitment to Bolshevism. It nevertheless refused to do battle against the UNR, and was disarmed by envoys from Husiatyn in early April.

As many as 50,000 peasants from around Khotyn, and some 4,000 to 10,000 armed rebels, crossed the Dniester, settling in either UNR or Soviet territories. Meanwhile, those refugees who still rejected communism appealed for support from the Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

: on February 4, their "general assembly" in Zhvanets pleaded with the Entente to demand the immediate withdrawal of Romanian troops from Hotin County. Other circles in the Ukraine also embraced the cause. On February 12, the British legation in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

received a letter of protest from a self-proclaimed delegation of Bessarabians, which included S. M. Wolkenstein and H. M. Kudik as Khotyn delegates. This text affirmed commitment not the UNR, but to Russia, depicting Romania as an "invader", and its culture as "Asian".

The

The Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, under Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, advanced southwards and conquered most of Podolia by April. The region was incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR; this new regime quickly restored the Bessarabian Brigade, but purged it of political suspects. During the early days of May, Antonov considered plans for immediately "freeing Bessarabia" by invading through Khotyn. He was finally dissuaded from ordering it by Romanian successes on the Hungarian Front, and by supply inadequacies. Ukrainian–Romanian skirmishes continued over several months, just as the Peace Conference began analyzing the eastern borders of Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

. Atachi's inhabitants remained exceptionally hostile to Romanian rule, and Soviet soldiers felt encouraged to fire on Romanian positions during May 30; suspicions arose in Romanian circles that an "international battalion" was being trained to invade Bessarabia from Mohyliv.

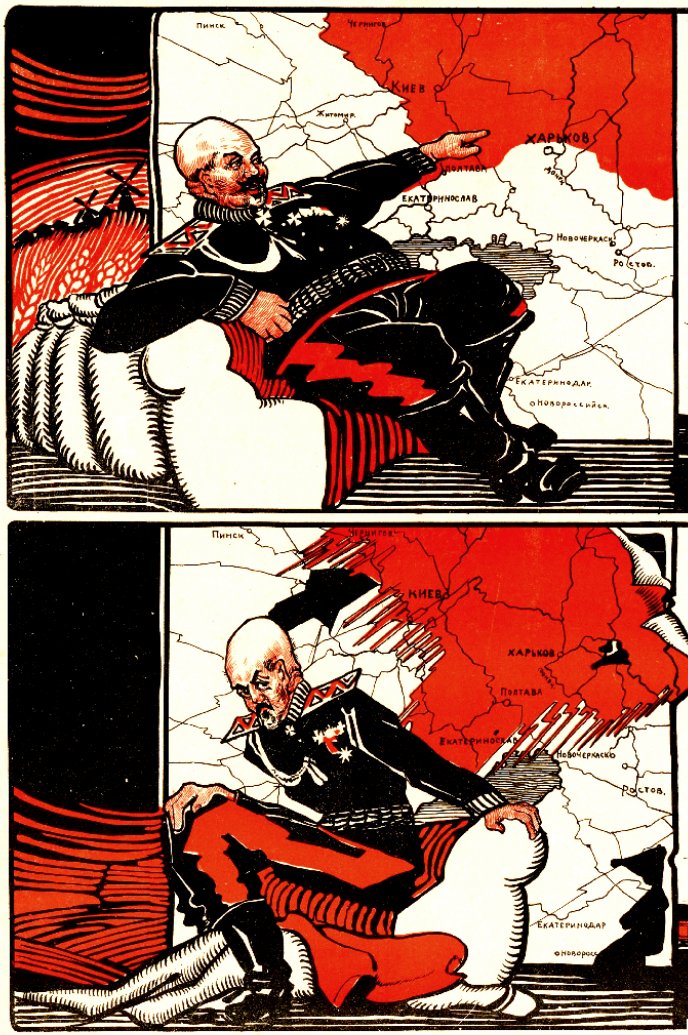

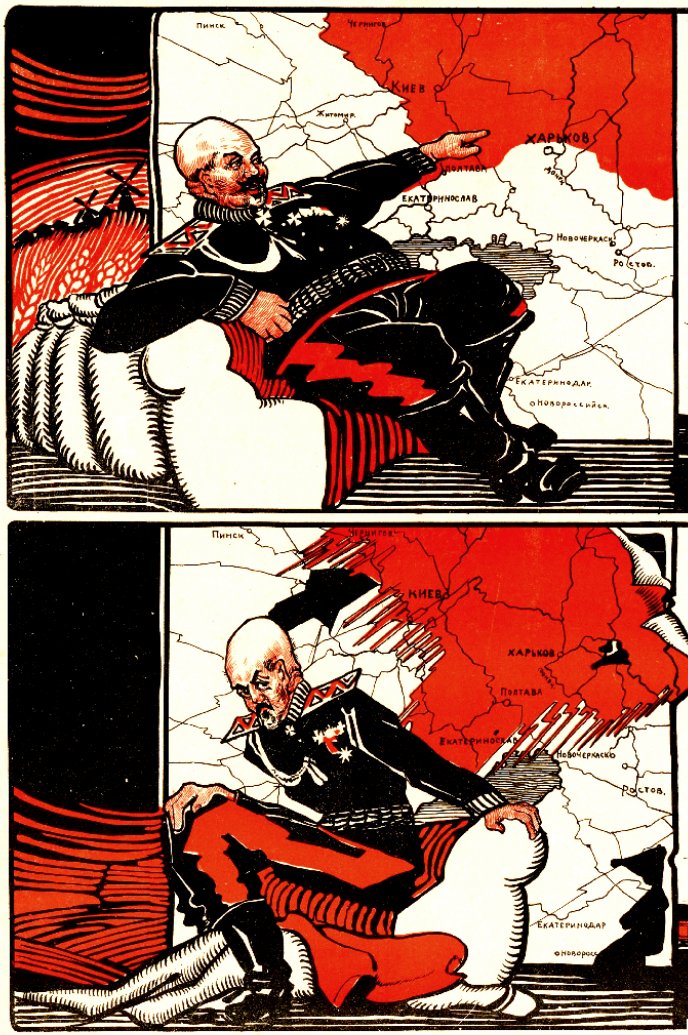

Romanians were still pained by echoes of Davidoglu's action, and knew that the Conference could recognize Ukrainian demands in Hotin County. As noted by Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Popenko: "From the very first days of the conference, Romanian diplomats had been active in arguing that the Khotyn Uprising was an attempt by the Bolsheviks to destabilize the country and spread its ideology further into Europe. Against the background of anti-Bolshevik sentiments among the major states, such an 'interpretation' of events was an extremely successful diplomatic and propaganda step." Popenko also notes that this approach came to be favored by the Allied intervention forces in Russia, who advised the UNR to settle its border issues with Romania, viewing the latter as the "final bulwark against Bolshevism".

VSYuR and ''Zakordot''

Zhurari sealed a pact with the Red Army and was allowed to leave Tiraspol unharmed; some of his men returned to Bessarabia, while others were admitted into the Red Army. Both groups may have played a part in the Bolshevik attempt to seize Tighina, on May 27, 1919 ''(see Bender Uprising)''. Whites, unlike communists, were generally spared by the Romanian Army, but the authorities still intervened when, in June, a ''Polkovnik'' Gagauz was caught preaching revolution to the inhabitants ofComrat

Comrat ( ro, Comrat, ; gag, Komrat, Russian and bg, Комрат, Komrat) is a city and municipality in Moldova and the capital of the autonomous region of Gagauzia. It is located in the south of the country, on the Ialpug River. In 2014, Com ...

. Such agitation largely ceased in June, when the Romanian government allowed N. N. Kozlov and A. A. Gepetskiy to recruit Bessarabian White officers for service in the Armed Forces of South Russia

The Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR or SRAF) () were the unified military forces of the White movement in southern Russia between 1919 and 1920.

On 8 January 1919, the Armed Forces of South Russia were formed, incorporating the Volunteer Army ...

(VSYuR), which secured a base in Odessa and pushed Antonov's forces out of the region. Various members of the Salvation Committee proposed to Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

that they stage instead a takeover of Bessarabia, and Denikin promised to assist them after first "finish ngoff" the UNR. In August, Konstantyn A. Matsevych, who served as UNR diplomatic representative in Romania, made a futile effort to reconcile the Directorate with Denikin.

While acting as head of the VSYuR counterintelligence in Odessa, Gepetskiy permitted Bolsheviks to assemble, despite Denikin's large-scale offensive into Russia. As Șornikov notes, he still prioritized the Bessarabian takeover ahead of all other issues, and effectively had a truce with communist partisans. The All-Russian National Center, functioning in the White-held city on Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don ( rus, Ростов-на-Дону, r=Rostov-na-Donu, p=rɐˈstof nə dɐˈnu) is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East ...

, maintained a claim to both Bessarabia and the Ukraine, accusing Romania and the UNR of colluding with each other to partition the area. Also working under Denikin's watch, N. A. Zelenetskiy began forming the 14th Infantry Division and 14th Artillery Brigade, specifically for the recovery of Bessarabia.

Denikin's successes also rekindled partisan activity in Podolia. VSYuR's Gagauz was able to recruit some 13,000 veterans from the Ukrainian Galician Army

Ukrainian Galician Army ( uk, Українська Галицька Армія, translit=Ukrayins’ka Halyts’ka Armiya, UHA), was the Ukrainian military of the West Ukrainian National Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. It ...

, who were then distributed to garrisons along the Dniester, ostensibly preparing to "liberate Bessarabia" upon the end of the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. In November, following Denikin's defeat at Orel, these units were moved to assist against the advancing Red Army. Gepetskiy's men were still preparing for an attack on Bessarabia, and collected 12 million rubles for this goal. These were confiscated by Kotovsky and the Red Army, which retook Tiraspol without a fight in February 1920. These units included various veterans of Filipchuk's army in Khotyn, including Shynkarenko and M. I. Nyagu, both of whom had command roles. Shynkarenko was later called up to fight the Basmachi movement

The Basmachi movement (russian: Басмачество, ''Basmachestvo'', derived from Uzbek: "Basmachi" meaning "bandits") was an uprising against Russian Imperial and Soviet rule by the Muslim peoples of Central Asia.

The movement's roots ...

in Turkestan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turk ...

.

The Red Army allowed VSYuR survivors under Nikolai Bredov to move into Nova Ushytsia, just north of Khotyn. They surrendered to the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history str ...

, with Romania having repeatedly refused them entry. From that moment on, the Soviets could form their own networks in Khotyn; a Romanian diplomatic cable from June 1920 claims that 200 recruiters for the Red Army were active in the county. From October, the Ukrainian Communist Party

The Ukrainian Communist Party ( uk, Українська Комуністична Партія, ''Ukrayins’ka Komunistychna Partiya'') was an oppositional political party in Soviet Ukraine, from 1920 until 1925. Its followers were known as Ukap ...

's office for foreign infiltration, '' Zakordot'', took over the task of destabilizing the Romanian presence. By 1921, they had organized a network of small-scale guerilla units, which crossed the Dniester for hit-and-run attacks on Romanian targets. ''Zakordot'' raids in mid 1921 resulted in the targeted murders of officials and clergymen in Dăncăuți, Poiana and Rașcov. These groups also made efforts to find and punish landowner Moșan, who stood accused of having organized violent retribution after the 1919 uprising. In August 1921, they attacked Moșan's manor outside Stălinești, killing several members of his family. Meanwhile, the anti-communist segment of the Ukrainian diaspora was strengthened by some 400 UNR refugees, some of whom found work at Hotin County's sugar mill

A sugar cane mill is a factory that processes sugar cane to produce raw or white sugar.

The term is also used to refer to the equipment that crushes the sticks of sugar cane to extract the juice.

Processing

There are a number of steps in p ...

.

Ahead of the November 1919 elections, Hotin County became a hub of the Bessarabian Peasants' Party

The Bessarabian Peasants' Party ( ro, Partidul Țărănesc din Basarabia, PȚB or PȚ-Bas; also ''Partidul Țărănesc Basarabean'', ''Partidul Țărănist Basarabean'') or Moldavian National Democratic Party (''Partidul Național-Democrat Moldove ...

(PȚB), which canvassed among the Jewish and Ukrainian populace. The group was the only one to submit a list, which had support from some 62% of registered voters (an additional 7.6% cast blank votes). All of the county's first representatives in the Assembly of Deputies were PȚB members, but represented three distinct ethnicities: Daniel Ciugureanu

Daniel Ciugureanu (; 9 December 1885 – 19 May 1950) was a Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, ...

stood for the Romanians, Iancu Melic-Melicsohn for the Jews, and Pavel Kitaigorodski for the Ukrainians. Romanian Police

The Romanian Police ( ro, Poliția Română, ) is the national police force and main civil law enforcement agency in Romania. It is subordinated to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and it is led by a General Inspector with the rank of Secretary ...

officials in the region reportedly viewed all Hotin deputies as "more than suspicious", in that they endorsed the notion of an autonomous Bessarabia.

Later history

The UNR was dissolved upon the conclusion of its war with Russia in late 1921, leaving Khotyn and Bessarabia to be governed by Romania, directly on its closed border with the

The UNR was dissolved upon the conclusion of its war with Russia in late 1921, leaving Khotyn and Bessarabia to be governed by Romania, directly on its closed border with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Prosecution of the 1919 rebels was pursued over several years. Rebels captured before January 23 were treated with more leniency, and made subject to trials by military courts. Examples include Alexei Borodaty and M. V. Bulkat, the latter of whom died in Craiova

)

, official_name = Craiova

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = From left: Dolj County Prefecture • Constantin Mihail Palace • Bibescu Manor House • Carol I National College • Museum of Oltenia • University of Craio ...

prison in 1924. In late 1921, Romanian troops captured a "Bodnarciuc gang", which had been active in northern Bessarabia, and which, they alleged, "maintained strong links with well-organized gangs from across the Dniester, who were themselves Bessarabians crossed over during the revolution of 1919." Bărbuță's aide S. Foșu was finally captured in 1929, and sentenced to death for his participation in Poetaș's killing.

Romanian authorities in Hotin became widely known for their mismanagement and embezzlement, with wide-ranging consequences: in 1923, the prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

was under investigation for hoarding all pigs out of Hotin and selling them in Bukovina for personal gain. Reports by the Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

signaled that Hotin inhabitants remained profoundly anti-Romanian. Officials intended to subvert the trend by closing down Russian-language education and enforcing Romanianization

Romanianization is the series of policies aimed toward ethnic assimilation implemented by the Romanian authorities during the 20th and 21st century. The most noteworthy policies were those aimed at the Hungarian minority in Romania, Jews and as ...

. A controversy erupted in 1925–1926, when Hotin peasant Ioan Mosoloc was sentenced to 5 years of servitude for participation in the 1919 revolt. On retrial, he was able to prove that he had been entirely absent from Bessarabia during the events, and that statements to the contrary had been fabricated by the hostile Gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally ...

.

During the early 1930s, the region was more heavily impacted by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The Financial contagion, ...

, prompting renewed activities by communist agents, but also agitation the antisemitic National-Christian Defense League

The National-Christian Defense League ( ro, Liga Apărării Național Creștine, LANC) was a far-right political party of Romania formed by A. C. Cuza.

Origins

The LANC had its roots in the National Christian Union, formed in 1922 by Cuza and the ...

. In May 1933, Vasily Gotinchan attempted to establish a local chapter of the pro-communist Liberation Party, but was apprehended and put on trial. A Ukrainian branch of the Romanian Communist Party