Katangese Gendarmerie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

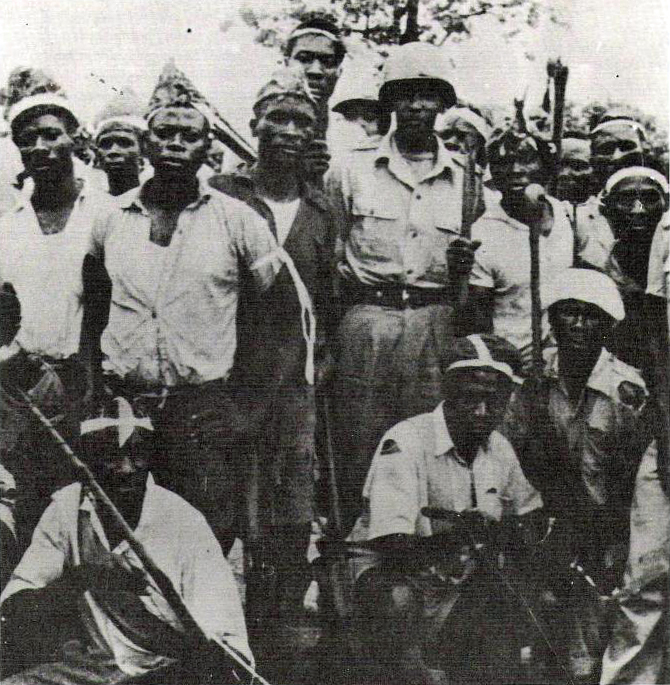

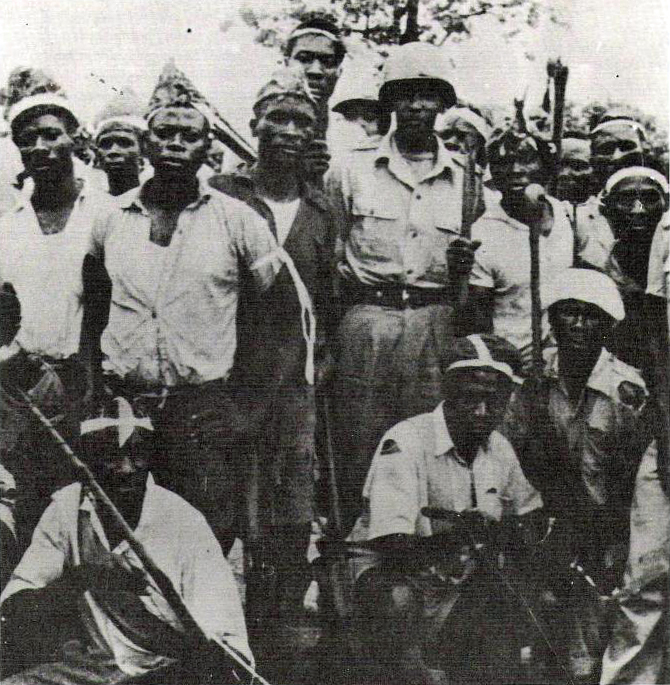

The Katangese Gendarmerie (french: Gendarmerie Katangaise), officially the Katangese Armed Forces (french: Forces Armées Katangaises, links=no), was the paramilitary force of the unrecognized

The

The

Much of Gendarmerie's early organization was based on the Force Publique's organization, and it was characterized by rapid advancement of many soldiers. By January 1961 there were approximately 250 former Force Publque officers serving in the Gendarmerie. They occupied all senior leadership positions and part of their salaries was paid by the Belgian government under a technical assistance programme. There were also 30–40 officers of the

Much of Gendarmerie's early organization was based on the Force Publique's organization, and it was characterized by rapid advancement of many soldiers. By January 1961 there were approximately 250 former Force Publque officers serving in the Gendarmerie. They occupied all senior leadership positions and part of their salaries was paid by the Belgian government under a technical assistance programme. There were also 30–40 officers of the

On 7 January 1961 troops from Stanleyville occupied Manono in northern Katanga. Accompanying BALUBAKAT leaders declared the establishing of a new "Province of Lualaba" that extended throughout the region. The ONUC contingents were completely surprised by the takeover in Manono. Tshombe and his government accused ONUC of collaborating with the Stanleyville regime and declared that they would no longer respect the neutral zone. By late January groups of Baluba were launching attacks on railways. UN officials appealed for them to stop, but the Baluba leaders stated that they aimed to do everything within their power to weaken the Katangese government and disrupt the Katangese Gendarmerie's offensive potential. On 21 February 1961 the

On 7 January 1961 troops from Stanleyville occupied Manono in northern Katanga. Accompanying BALUBAKAT leaders declared the establishing of a new "Province of Lualaba" that extended throughout the region. The ONUC contingents were completely surprised by the takeover in Manono. Tshombe and his government accused ONUC of collaborating with the Stanleyville regime and declared that they would no longer respect the neutral zone. By late January groups of Baluba were launching attacks on railways. UN officials appealed for them to stop, but the Baluba leaders stated that they aimed to do everything within their power to weaken the Katangese government and disrupt the Katangese Gendarmerie's offensive potential. On 21 February 1961 the

After being pressured by the United States and United Nations, Belgium removed many of its forces from the region from August to September 1961. However, many officers remained, without official Belgian endorsement, or became mercenaries. To support the Katangese, Belgium organized hundreds of Europeans to fight with Katanga as mercenaries. At the same time the United Nations attempted to suppress foreign support to the Gendarmerie; 338 mercenaries and 443 political advisers were expelled from the region by August. That same month, war veterans were first honored by the Katangese government. Dead soldiers were also remembered in ceremonies at the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Élisabethville.

On August 2, 1961,

After being pressured by the United States and United Nations, Belgium removed many of its forces from the region from August to September 1961. However, many officers remained, without official Belgian endorsement, or became mercenaries. To support the Katangese, Belgium organized hundreds of Europeans to fight with Katanga as mercenaries. At the same time the United Nations attempted to suppress foreign support to the Gendarmerie; 338 mercenaries and 443 political advisers were expelled from the region by August. That same month, war veterans were first honored by the Katangese government. Dead soldiers were also remembered in ceremonies at the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Élisabethville.

On August 2, 1961,  Relations between the UN and Katanga rapidly deteriorated in early September, and Katangese forces were placed on alert. Growing frustrated with Katanga's lack of cooperation and its continued employ of mercenaries, several ONUC officials planned a more forceful operation to establish their authority in Katanga. With the ultras in command and with its African members fearing their own disarmament in addition to that of the European mercenaries, the Gendarmerie moved additional troops to Élisabethville and began stockpiling weapons in private homes and offices for a defence. On September 13, 1961, ONUC launched Operation Morthor, a second attempt to expel remaining Belgians, without consulting any Western powers. The forces seized various outposts around Élisabethville, and attempted to arrest Tshombe. The operation quickly turned violent after a sniper shot an ONUC soldier outside the post office while other peacekeepers were attempting to negotiate its surrender, and heavy fighting ensued there and at the radio station in which over 20 gendarmes were killed under disputed circumstances. Due to miscommunication between ONUC commanders, Tshombe was able to avoid capture and flee to

Relations between the UN and Katanga rapidly deteriorated in early September, and Katangese forces were placed on alert. Growing frustrated with Katanga's lack of cooperation and its continued employ of mercenaries, several ONUC officials planned a more forceful operation to establish their authority in Katanga. With the ultras in command and with its African members fearing their own disarmament in addition to that of the European mercenaries, the Gendarmerie moved additional troops to Élisabethville and began stockpiling weapons in private homes and offices for a defence. On September 13, 1961, ONUC launched Operation Morthor, a second attempt to expel remaining Belgians, without consulting any Western powers. The forces seized various outposts around Élisabethville, and attempted to arrest Tshombe. The operation quickly turned violent after a sniper shot an ONUC soldier outside the post office while other peacekeepers were attempting to negotiate its surrender, and heavy fighting ensued there and at the radio station in which over 20 gendarmes were killed under disputed circumstances. Due to miscommunication between ONUC commanders, Tshombe was able to avoid capture and flee to

In Kamina, the gendarmes had expected an attack on 30 December, but when one failed to occur they began to drink beer and fire flares at random, possibly to boost morale. Rogue bands of gendarmes subsequently conducted random raids around the city and looted the local bank. They were attacked by Swedish and Ghanaian troops two or three kilometers northeast of Kamina the following day, and were defeated. The Katangese Gendamerie conducted a disorganised withdrawal to two camps southeast of the locale. The Swedes successfully took several gendarmerie camps and began working to stabilise the situation. Late that night a company of the Indian Rajputana Rifles encountered entrenched gendarmes and mercenaries along Jadotville Road and a gunfight ensued. Two mercenaries captured during the clash revealed that confusion and desertion were occurring among the Katangese forces. Altogether the Indian forces faced unexpectedly light resistance and reached the east bank of the Lufira on 3 January 1963. Mercenaries withdrew to Jadotville the next day after destroying a bridge over the Lufira River. UN forces found a bridge upstream and used rafts and helicopters to cross and neutralised Katangese opposition on the far side of the river, occupying Jadotville.

Muké attempted to organise a defence of the town, but Katangese forces were in disarray, being completely caught off-guard by the UN troops' advance. UN forces briefly stayed in Jadotville to regroup before advancing on Kolwezi, Sakania, and Dilolo. Between 31 December 1962 and 4 January 1963, international opinion rallied in favour of ONUC. Belgium and France strongly urged Tshombe to accept Thant's Plan for National Reconciliation and resolve the conflict. On 8 January, Tshombe reappeared in Élisabethville. The same day Prime Minister Adoula received a letter from the chiefs of the most prominent Kantangese tribes pledging allegiance to the Congolese government and calling for Tshombe's arrest. Thant expressed interest in negotiating with Tshombe, saying "If we could convince shombethat there is no more room for maneuvering and bargaining, and no one to bargain with, he would surrender and the gendarmerie would collapse." Tshombe soon expressed his willingness to negotiate after being briefly detained and released, but warned that any advance on Kolwezi would result in the enactment of a

In Kamina, the gendarmes had expected an attack on 30 December, but when one failed to occur they began to drink beer and fire flares at random, possibly to boost morale. Rogue bands of gendarmes subsequently conducted random raids around the city and looted the local bank. They were attacked by Swedish and Ghanaian troops two or three kilometers northeast of Kamina the following day, and were defeated. The Katangese Gendamerie conducted a disorganised withdrawal to two camps southeast of the locale. The Swedes successfully took several gendarmerie camps and began working to stabilise the situation. Late that night a company of the Indian Rajputana Rifles encountered entrenched gendarmes and mercenaries along Jadotville Road and a gunfight ensued. Two mercenaries captured during the clash revealed that confusion and desertion were occurring among the Katangese forces. Altogether the Indian forces faced unexpectedly light resistance and reached the east bank of the Lufira on 3 January 1963. Mercenaries withdrew to Jadotville the next day after destroying a bridge over the Lufira River. UN forces found a bridge upstream and used rafts and helicopters to cross and neutralised Katangese opposition on the far side of the river, occupying Jadotville.

Muké attempted to organise a defence of the town, but Katangese forces were in disarray, being completely caught off-guard by the UN troops' advance. UN forces briefly stayed in Jadotville to regroup before advancing on Kolwezi, Sakania, and Dilolo. Between 31 December 1962 and 4 January 1963, international opinion rallied in favour of ONUC. Belgium and France strongly urged Tshombe to accept Thant's Plan for National Reconciliation and resolve the conflict. On 8 January, Tshombe reappeared in Élisabethville. The same day Prime Minister Adoula received a letter from the chiefs of the most prominent Kantangese tribes pledging allegiance to the Congolese government and calling for Tshombe's arrest. Thant expressed interest in negotiating with Tshombe, saying "If we could convince shombethat there is no more room for maneuvering and bargaining, and no one to bargain with, he would surrender and the gendarmerie would collapse." Tshombe soon expressed his willingness to negotiate after being briefly detained and released, but warned that any advance on Kolwezi would result in the enactment of a

Small arms

*

Small arms

*

State of Katanga

The State of Katanga; sw, Inchi Ya Katanga) also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local ''C ...

in Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Cong ...

from 1960 to 1963. The forces were formed upon the secession of Katanga from the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

with help from Belgian soldiers and former officers of the ''Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of Be ...

''. Belgian troops also provided much of the early training for the Gendarmerie, which was mainly composed of Katangese but largely led by Belgians and later European mercenaries.

Throughout the existence of the State of Katanga, the gendarmes sporadically fought various tribes and the Armée Nationale Congolaise

The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo ARDC is the state organisation responsible for defending the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The FARDC was rebuilt pa ...

(ANC). In February 1961 the Gendarmerie initiated a series of operations aimed at suppressing anti-secessionist rebels of the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT) in North Katanga. The campaign was largely successful, but the fighting led to atrocities and gendarmes were halted by forces of the United Nations Operation in the Congo

The United Nations Operation in the Congo (french: Opération des Nations Unies au Congo, abbreviated to ONUC) was a United Nations peacekeeping force deployed in the Republic of the Congo in 1960 in response to the Congo Crisis. ONUC was the ...

(ONUC) during the Battle of Kabalo in April 1961. ONUC then initiated efforts to remove foreign mercenaries from the Gendarmerie, and launched Operation Rum Punch to arrest them in August 1961. They came into conflict with ONUC three times after, in Operation Morthor (September 1961), Operation UNOKAT (December 1961), and Operation Grandslam

Operation Grandslam was an offensive undertaken by United Nations peacekeeping forces from 28 December 1962 to 15 January 1963 against the forces of the State of Katanga, a secessionist state rebelling against the Republic of the Co ...

(December 1962). Operation Grandslam marked the end of the Katangese secession in January 1963.

After the secession, many gendarmes returned to civilian life or were integrated with the ANC. However, around 8,000 refused to, and many kept their arms and roamed North Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

, Angola and Katanga. Many crossed the Congo border into Angola, where Portuguese colonial authorities assisted and trained them. They were involved in several mutinies and attempted invasions of the Congo, most notably the Stanleyville mutinies

The Kisangani mutinies, also known as the Stanleyville mutinies or Mercenaries' mutinies, occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1966 and 1967.

First mutiny

Amid rumours that the ousted Prime Minister Moise Tshombe was plotting a co ...

in 1966 and 1967.

After 1967, around 2,500 gendarmes were present in Angola, where they were reorganized as the Congolese National Liberation Front (FLNC) and fought in the Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

on the side of the Portuguese government against the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) and União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement fo ...

(UNITA). When the war ended in 1975, they fought in the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war wa ...

against the National Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independenc ...

(FNLA). The FLNC was involved in Shaba I

Shaba I was a conflict in Zaire's Shaba (Katanga) Province lasting from March 8 to May 26, 1977. The conflict began when the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo (FNLC), a group of about 2,000 Katangan Congolese soldiers who were vet ...

and II, attempted invasions of Katanga. Split into factions after the war, the Tigres emerged and played a decisive role in the First Congo War

The First Congo War, group=lower-alpha (1996–1997), also nicknamed Africa's First World War, was a civil war and international military conflict which took place mostly in Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo), with major spill ...

. There has since been little gendarme presence, but they have emerged as a symbol of secessionist thinking.

Origins

Background

The

The Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

was established from the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leop ...

in 1908. Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to the ...

held control of the colony until it gained independence as the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

on June 30, 1960. Though the nation had elected officials including Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of the Kongo ...

as president

President most commonly refers to:

* President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

, Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June ...

as prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, and various bodies including a senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

and assembly, upon independence its affairs quickly devolved into chaos. Congolese soldiers mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

against their white commanders in the Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of Be ...

on July 5. The action signaled the beginning of a large revolt and attacks on white people in the Congo. In response, Belgium sent troops into the region to maintain order and protect their commercial interests, without the permission of the Congolese state.

Largely in response to Belgian interference, on July 11, the Katanga Province

Katanga was one of the four large provinces created in the Belgian Congo in 1914.

It was one of the eleven provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1966 and 2015, when it was split into the Tanganyika, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba, ...

announced its secession from the Republic of the Congo under the leadership of Moise Tshombe

Moise is a given name and surname, with differing spellings in its French and Romanian origins, both of which originate from the name Moses: Moïse is the French spelling of Moses, while Moise is the Romanian spelling. As a surname, Moisè and Mo ...

. The state also represented Belgian mining interests. The State of Katanga

The State of Katanga; sw, Inchi Ya Katanga) also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local ''C ...

began establishing the organs necessary for a state to function independently, with a constitution and ministers. Patrice Lumumba called for United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

intervention to end various secession movements in the country. The UN "called upon" Belgium to leave the Congo in Resolution 143 adopted on July 14 that also authorized the creation of the United Nations Operation in the Congo

The United Nations Operation in the Congo (french: Opération des Nations Unies au Congo, abbreviated to ONUC) was a United Nations peacekeeping force deployed in the Republic of the Congo in 1960 in response to the Congo Crisis. ONUC was the ...

(ONUC), a multinational peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities intended to create conditions that favour lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed warfare.

Within the United ...

force aimed at helping "the Congolese government restore and maintain the political independence and territorial integrity of the Congo." By the end of July, 8,400 UN troops had been deployed to the Congo.

Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 19 ...

, the Secretary-General of the United Nations

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-g ...

, and Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize f ...

, his special representative, believed that engaging in Katanga would result in fighting, and refused to allow peacekeepers to enter the region. In reality, Katanga at the time had an ill-trained fighting force, mainly made up of dozens of Belgian officers. United Nations Security Council Resolution 146

United Nations Security Council Resolution 146, adopted on August 9, 1960, after a report by the Secretary-General regarding the implementation of resolutions 143 and 145 the Council confirmed his authority to carry out the responsibility place ...

, passed on August 9, supplemented Resolution 143 and stated that "the entry of the United Nations Force into the province of Katanga is necessary for the full implementation of the present resolution". However, the resolution also mandated that the "United Nations Force in the Congo will not be a party to or in any way intervene in or be used to influence the outcome of any internal conflict, constitutional or otherwise." Frustrated, Lumumba appealed to Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

nations for military assistance, resulting in a conflict with Kasa-Vubu and ultimately his removal from power in September and eventual murder in January 1961. In response to Lumumba's removal, his political allies gathered in Stanleyville in the eastern Congo and declared a rival regime to the central government in Léopoldville

Kinshasa (; ; ln, Kinsásá), formerly Léopoldville ( nl, Leopoldstad), is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Once a site of fishing and trading villages situated along the Congo River, Kinshasa is now one ...

.

Formation

In order to develop a stronger fighting force, Katanga (with the help of Belgians) disarmed all Force Publique troops based in Camp Massart except for 350 Katangese soldiers. The first iteration of the army was planned to consist of 1,500 men, all Katangese. The first volunteers were primarilyLunda people

The Lunda (''Balunda'', ''Luunda'', ''Ruund'') are a Bantu ethnic group that originated in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo along the Kalanyi River and formed the Kingdom of Lunda in the 17th century under their ruler, Mwata Ya ...

from South Katanga, who were organized by the Mwaant Yav and Tshombe's family. Throughout the year additional forces were recruited, including Luba warriors, 2,000 Bazela from Pweto

Pweto is a town in the Haut-Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It is the administrative center of Pweto Territory. The town was the scene of a decisive battle in December 2000 during the Second Congo War which resulted ...

, Bayeke from Bunkeya

Bunkeya is a community in the Lualaba Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

It is located on a huge plain near the Lufira River.

Before the Belgian colonial conquest, Bunkeya was the center of a major trading state under the ruler Msiri ...

, and several white volunteers from Kaniama. By November, the Gendarmerie had 7,000 members. The army was largely organized, led, and trained by Belgians who were former Force Publique officers; the first commander of the Gendarmerie was Jean-Marie Crèvecoeur, appointed on July 13. The majority of soldiers were Katangese. The forces were first called the "Katangese Armed Forces" in November 1960. Katanga also seized most of the assets of the Force Publique's air service, providing a nucleus for the Katangese Air Force

The Katangese Air Force (french: Force aérienne katangaise, or FAK) or Katangese Military Aviation (french: Aviation militaire Katangaise, or Avikat) was a short lived air force of the State of Katanga, established in 1960 under the command of Ja ...

. Joseph Yav, a native Katangese, was made Minister of Defence.

Much of Gendarmerie's early organization was based on the Force Publique's organization, and it was characterized by rapid advancement of many soldiers. By January 1961 there were approximately 250 former Force Publque officers serving in the Gendarmerie. They occupied all senior leadership positions and part of their salaries was paid by the Belgian government under a technical assistance programme. There were also 30–40 officers of the

Much of Gendarmerie's early organization was based on the Force Publique's organization, and it was characterized by rapid advancement of many soldiers. By January 1961 there were approximately 250 former Force Publque officers serving in the Gendarmerie. They occupied all senior leadership positions and part of their salaries was paid by the Belgian government under a technical assistance programme. There were also 30–40 officers of the Belgian Army

The Land Component ( nl, Landcomponent, french: Composante terre) is the land branch of the Belgian Armed Forces. The King of the Belgians is the commander in chief. The current chief of staff of the Land Component is Major-General Pierre Gérar ...

officially on loan to the Katangese government who either held commands in the gendarmerie, staffed the Katangese Ministry of Defence, or served as advisers. Between 50 and 100 mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

of various nationalities were initially present, but over the course of 1961 the Katangese government increased recruitment efforts. Three Fouga trainer aircraft were also acquired. In August, most of the Belgian officers returned to Belgium, and mercenaries began training many of the soldiers. From its formation the force struggled with divisions between various white and black commanders. Belgian officers also protested the recruitment of Frenchmen. Though South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

officially denied Katangese requests for arms, there is evidence of a covert program supplying weapons to the Gendarmerie.

Katangese secession (1960–1963)

Early action and suppressing rebellion in northern Katanga

In the immediate aftermath of the Katangese secession, Katangese forces clashed with theArmée Nationale Congolaise

The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo ARDC is the state organisation responsible for defending the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The FARDC was rebuilt pa ...

(ANC) in the Kasai region. In August 1960 the region of South Kasai

South Kasai (french: Sud-Kasaï) was an unrecognised secessionist state within the Republic of the Congo (the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) which was semi-independent between 1960 and 1962. Initially proposed as only a province, ...

seceded from the Congo. The ANC launched an offensive and successfully occupied it, but the Gendarmerie and South Kasian forces successfully prevented them from making incursions into Katanga.

The Gendarmerie first saw major action in Northern Katanga in efforts to suppress the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT), a political party which represented the Luba people

The Luba people or Baluba are an ethno-linguistic group indigenous to the south-central region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The majority of them live in this country, residing mainly in Katanga, Kasai and Maniema. The Baluba Tribe ...

of the area and rebelled against Katangese authority. Some prominent BALUBAKAT politicians allied themselves with the Stanleyville government. On October 17, 1960, neutral zones were created in the region under a temporary agreement with the United Nations. In theory the region was controlled by ONUC contingents, but in reality the peacekeeping units were too weak to exercise authority. Because the rebellion threatened Katanga's communications, partially-trained soldiers and policemen were dispatched in units of around 60 people to the region to exert Katangese control. The inexperienced troops often resorted to pillaging

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

and burning settlements. Political scientist Crawford Young suggested that the tactics were intentional and represented "little more than terrorization carried out by indiscriminate reprisals against whole regions."

On 7 January 1961 troops from Stanleyville occupied Manono in northern Katanga. Accompanying BALUBAKAT leaders declared the establishing of a new "Province of Lualaba" that extended throughout the region. The ONUC contingents were completely surprised by the takeover in Manono. Tshombe and his government accused ONUC of collaborating with the Stanleyville regime and declared that they would no longer respect the neutral zone. By late January groups of Baluba were launching attacks on railways. UN officials appealed for them to stop, but the Baluba leaders stated that they aimed to do everything within their power to weaken the Katangese government and disrupt the Katangese Gendarmerie's offensive potential. On 21 February 1961 the

On 7 January 1961 troops from Stanleyville occupied Manono in northern Katanga. Accompanying BALUBAKAT leaders declared the establishing of a new "Province of Lualaba" that extended throughout the region. The ONUC contingents were completely surprised by the takeover in Manono. Tshombe and his government accused ONUC of collaborating with the Stanleyville regime and declared that they would no longer respect the neutral zone. By late January groups of Baluba were launching attacks on railways. UN officials appealed for them to stop, but the Baluba leaders stated that they aimed to do everything within their power to weaken the Katangese government and disrupt the Katangese Gendarmerie's offensive potential. On 21 February 1961 the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, a ...

passed a resolution permitting ONUC to use military force as a last resort to prevent civil war. As the Congo was already more-or-less in a state of civil war, the resolution gave ONUC significant latitude to act. It also called for the immediate departure of all foreign military personnel and mercenaries from the country, though the use of force was not authorised to carry out the measure. Therefore, force could only be used to remove foreign soldiers and mercenaries if it was justified under the reasoning that such action would be necessary to prevent civil war.

By February 1961 the Gendarmerie was composed of around 8,600 soldiers—8,000 Katangese and 600 Europeans. On 11 February, the Katangese government announced that it would begin an offensive to eliminate the Baluba opposition in northern Katanga. Approximately 5,000 troops were earmarked for the operation, which focused on a northward offensive from Lubudi. At the same time, they were to recapture the town of Manono, secure the area south of it, and launch attacks on Kabalo from Albertville

Albertville (; Arpitan: ''Arbèrtvile'') is a subprefecture of the Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Southeastern France.

It is best known for hosting the 1992 Winter Olympics and Paralympics. In 2018, the commune had ...

to the east and Kongolo to the north. The Katangese Gendarmerie subsequently launched operations Banquise, Mambo, and Lotus against the BALUBAKAT rebels. In March the army seized Manono.

The Gendarmerie then shifted their focus to Kabalo, where they chiefly intended to secure the railway. The town was garrisoned by two companies of an Ethiopian battalion serving with ONUC. On 7 April a Katangese plane carrying 30 mercenaries landed to secure the airstrip in the town but they were promptly arrested by the ONUC troops. Katangese forces moving by land attacked ONUC soldiers and fought with BALUBAKAT militia. The next day they sent an armed ferry up the river to seize the town, but ONUC forces destroyed it with a mortar, inflicting heavy casualties. The ONUC garrison played no further role in the fighting after 8 April. The Katangese made numerous attempts to enter Kabalo during the following days, but were bogged down by heavy resistance from Baluba militia. On 11 April Katangese troops withdrew from the area to focus their operations further south.

The captured mercenaries were interrogated by UN officials, and the information they provided revealed to ONUC the extent to which Katanga had been recruiting mercenaries in southern Africa; recruiting stations were present in both the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the B ...

and South Africa. Following questioning, the mercenaries were transferred to Léopoldville before being deported from the Congo to Brazzaville

Brazzaville (, kg, Kintamo, Nkuna, Kintambo, Ntamo, Mavula, Tandala, Mfwa, Mfua; Teke: ''M'fa'', ''Mfaa'', ''Mfa'', ''Mfoa''Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, ''Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture'', ABC-CL ...

. The capture of the mercenaries was given a great deal of public attention and affirmed that British nationals had been working in Katanga's employ. Due to the action of the ONUC garrison, Kabalo remained the only major town in northern Katanga not controlled by the Katangese Gendarmerie at the conclusion of their offensive. Though ONUC was able to retain control of the locale, it lacked the ability to patrol the surrounding area to intervene in further conflicts. Having been defeated, Katangese forces began conducting punitive attacks on Baluba villages. Opposed only by poorly armed bands of Baluba, the conflict resulted in both belligerents committing numerous atrocities.

Conflict with the United Nations

During the dissolution of the Lumumba Government, the Belgian government determined that their interests could be protected through negotiations with the Congolese government and began to gradually withdraw from Katanga. The state still had support from several Belgian politicians, such as René Clemens, the author of Katanga's constitution, and George Thyssens, who had drafted the Katangese declaration of independence and continued to serve as an important adviser. Additionally, companies such as Union Minière du Haut Katanga maintained relations with the state. Despite these interactions, the Belgian government gradually adopted a strategy of privately pressuring the Katangese to accept reintegration. Such efforts largely failed. After being pressured by the United States and United Nations, Belgium removed many of its forces from the region from August to September 1961. However, many officers remained, without official Belgian endorsement, or became mercenaries. To support the Katangese, Belgium organized hundreds of Europeans to fight with Katanga as mercenaries. At the same time the United Nations attempted to suppress foreign support to the Gendarmerie; 338 mercenaries and 443 political advisers were expelled from the region by August. That same month, war veterans were first honored by the Katangese government. Dead soldiers were also remembered in ceremonies at the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Élisabethville.

On August 2, 1961,

After being pressured by the United States and United Nations, Belgium removed many of its forces from the region from August to September 1961. However, many officers remained, without official Belgian endorsement, or became mercenaries. To support the Katangese, Belgium organized hundreds of Europeans to fight with Katanga as mercenaries. At the same time the United Nations attempted to suppress foreign support to the Gendarmerie; 338 mercenaries and 443 political advisers were expelled from the region by August. That same month, war veterans were first honored by the Katangese government. Dead soldiers were also remembered in ceremonies at the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul in Élisabethville.

On August 2, 1961, Cyrille Adoula

Cyrille Adoula (13 September 1921 – 24 May 1978) was a Congolese trade unionist and politician. He was the prime minister of the Republic of the Congo, from 2 August 1961 until 30 June 1964.

Early life and career

Cyrille Adoula was born to ...

was appointed to replace Lumumba as prime minister of the Congo. He began a far more aggressive policy of ending Katanga's secession than the interim Congolese government, and Belgium continued to pressure the Katangese authorities to begin negotiations. Young suggested that "from this point onward, Katanga fought a mainly diplomatic and partly military rearguard action against what was in retrospect the inevitable end to the secession." After Adoula's appointment, sporadic violence continued between tribes and the government, but Katanga was relatively peaceful for several months.

The battle at Kabalo led to heightened tensions between the UN and the Katangese government. The failure of the UN to convince the Katangese to dispel mercenaries from its forces led ONUC to begin Operation Rum Punch in late August 1961 to peacefully arrest foreign members of the Gendarmerie. The operation was conducted successfully without violence, and by its end 81 foreign personnel of the Katangese Gendarmerie had been arrested in Katanga and brought to Kamina base to await deportation. Most of the remaining Belgian mercenaries reported to their consulate in Élisabethville. In addition to the arrests, two Sikorsky helicopters, three Aloutte helicopters, three Dakotas

The Dakotas is a collective term for the U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota. It has been used historically to describe the Dakota Territory, and is still used for the collective heritage, culture, geography, fauna, sociology, econom ...

, four Doves

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily ...

, and two Herons

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychus ...

of the Katangese Air Force were seized. The Belgian government agreed facilitate the repatriation of its nationals serving in the Gendarmerie, but in practice was only able to order the former Force Publique officers to return to Belgium under threat of losing their official ranks in the Belgian Army. The operation also did not extend to all military centers in Katanga. Thus, many foreign officers, particularly the highly-committed "ultras" were able to avoid deportation. Further mercenary forces arrived in Katanga after the operation. British, Rhodesian, and South African fighters enlisted mostly for money and adventure, while the French mercenaries were regarded by UN officials as politically extreme. Colonel Norbert Muké, a native Katangese, was made commander of the Katangese Gendarmerie, but in practice its leadership was still heavily influenced by European mercenaries. Lieutenant Colonel Roger Faulques

Roger Louis Faulques (14 December 1924 – 6 November 2011) René Faulques, was a French Army Colonel, a graduate of the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, a paratrooper officer of the French Foreign Legion, and a mercenary. He fought in Wo ...

, a Frenchman, was made chief of staff, and he established a new headquarters near Kolwezi to coordinate anti-UN guerilla operations. The Gendarmerie continued to sporadically fight BALUBAKAT rebels until around September 1961.

Relations between the UN and Katanga rapidly deteriorated in early September, and Katangese forces were placed on alert. Growing frustrated with Katanga's lack of cooperation and its continued employ of mercenaries, several ONUC officials planned a more forceful operation to establish their authority in Katanga. With the ultras in command and with its African members fearing their own disarmament in addition to that of the European mercenaries, the Gendarmerie moved additional troops to Élisabethville and began stockpiling weapons in private homes and offices for a defence. On September 13, 1961, ONUC launched Operation Morthor, a second attempt to expel remaining Belgians, without consulting any Western powers. The forces seized various outposts around Élisabethville, and attempted to arrest Tshombe. The operation quickly turned violent after a sniper shot an ONUC soldier outside the post office while other peacekeepers were attempting to negotiate its surrender, and heavy fighting ensued there and at the radio station in which over 20 gendarmes were killed under disputed circumstances. Due to miscommunication between ONUC commanders, Tshombe was able to avoid capture and flee to

Relations between the UN and Katanga rapidly deteriorated in early September, and Katangese forces were placed on alert. Growing frustrated with Katanga's lack of cooperation and its continued employ of mercenaries, several ONUC officials planned a more forceful operation to establish their authority in Katanga. With the ultras in command and with its African members fearing their own disarmament in addition to that of the European mercenaries, the Gendarmerie moved additional troops to Élisabethville and began stockpiling weapons in private homes and offices for a defence. On September 13, 1961, ONUC launched Operation Morthor, a second attempt to expel remaining Belgians, without consulting any Western powers. The forces seized various outposts around Élisabethville, and attempted to arrest Tshombe. The operation quickly turned violent after a sniper shot an ONUC soldier outside the post office while other peacekeepers were attempting to negotiate its surrender, and heavy fighting ensued there and at the radio station in which over 20 gendarmes were killed under disputed circumstances. Due to miscommunication between ONUC commanders, Tshombe was able to avoid capture and flee to Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesi ...

.

Hammarskjöld and other top UN officials who had been not fully ware of the intentions of their subordinates were deeply embarrassed by the violence, which troubled Western powers who had supported the UN. Realising that the UN was in a precarious situation, Katangese leaders encouraged the Gendarmerie to increase its efforts and the conflict intensified over the following days. Strengthened with weapons provided by Rhodesia, the gendarmes launched mortar and sniper assaults on ONUC troops in Élisabethville, attacked ONUC garrisons throughout Katanga, and deployed the Katangese Air Force's single remaining Fouga to strafe and bomb ONUC positions. Gendarmes led by European officers besieged an Irish detachment in Jadotville and defeated UN relief efforts. Supporters of Katanga then began a propaganda campaign, accusing ONUC of various human rights violations, and there were reports of UN attacks on civilian institutions. As Hammarskjöld was flying to Ndola to meet with Tshombe to negotiate a peaceful end to the fighting, his plane crashed on September 18, 1961, and he was killed. A few days later a cease-fire was reached. That month, Gendarmerie forces were estimated to number 13,000; mainly deployed in North Katanga, troops were also present in Manono, Albertville, Kongolo, Kolwezi

Kolwezi or Kolwesi is the capital city of Lualaba Province in the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, west of Likasi. It is home to an airport and a railway to Lubumbashi. Just outside of Kolwezi there is the static inverter plant of ...

, and Jadotville.

Katangese leaders hailed the cease-fire as a military victory; Muké was promoted to general, and the exploits of the native Katangese gendarmes were widely celebrated, though some soldiers became disgruntled over the fact that they did not control the army like the foreign personnel. A formal agreement between Katanga and the UN ensured the exchange of prisoners and forced ONUC to relinquish some of its positions in Élisabethville. With his government threatened by the UN's failure, Adoula ordered two battalions of the ANC to launch an offensive, but the Katangese forces repulsed them with a bombardment.

U Thant

Thant (; ; January 22, 1909 – November 25, 1974), known honorifically as U Thant (), was a Burmese diplomat and the third secretary-general of the United Nations from 1961 to 1971, the first non-Scandinavian to hold the position. He held t ...

replaced Hammarskjöld as UN Secretary-General, and declared his support for the expulsion of the remaining mercenaries in the Katangese Gendarmerie. Security Council Resolution 169 was passed on November 24, 1961, affirming that the United Nations would "take vigorous action, including the use of the requisite measure of force, if necessary," to remove all "foreign military and paramilitary personnel and political advisers not under the United Nations Command, and mercenaries".

Throughout October and November the Gendarmerie was reinforced with additional mercenaries, munitions, and aircraft. As tensions rose, gendarmes harassed UN officials and murdered an ONUC officer. Skirmishes occurred in early December, and the Gendarmerie began isolating ONUC detachments around Élisabethville via a series of large roadblocks. On 5 December 1961, ONUC launched Operation Unokat, aimed at ensuring freedom of movement

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country,Jérémiee Gilbert, ''Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights ...

for ONUC personnel. Reinforced by additional troops and aircraft, UN forces quickly secured Élisabethville and destroyed four Katangese planes. Approximately 80 gendarmes were killed and 250 wounded in the fighting. Military pressure applied by the operation forced Tshombe to agree to negotiate with Adoula. Tshombe signed the Kitona Declaration on 21 December, 1961, agreeing that Katanga was part of the Congo, and announcing plans to re-integrate the state with the Congo. Even as negotiations were in progress, the Gendarmerie continued to skirmish with the ANC. Throughout the year, the ANC made continuous inroads in North Katanga.

The United States began increasing efforts in retraining or reorganizing the Gendarmerie, as the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

feared that "Katanga forces are likely to resort to guerrilla type operations and could severely harass UN forces for some time" if the situation was not resolved peacefully. It was suggested that the gendarmes could be integrated into the ANC, but Tshombe resisted such efforts, complicating negotiations. Tshombe continually stalled, drawing out negotiations until October 1962, when ONUC intelligence indicated the Gendarmes were preparing for war.

Operation Grandslam

On 24 December 1962, Katangese forces in Élisabethville attacked ONUC troops with small arms fire and shot down an unarmed ONUC helicopter. Firing continued over the following days. After conversation with UN officials, Tshombe made an initial promise to end the fighting, but he subsequently ordered the Katangese Air Force to raid ONUC positions. Radio intercepts also revealed to the UN that Muké had ordered the air force to bomb the Élisabethville airport on the night of 29 December. With the failure to enact a ceasefire, Major General Dewan Prem Chand of India convinced Thant to authorise a strong, decisive offensive to pre-emptively eliminate Katangese forces. ONUC launched Operation Grandslam on 28 December. On the first day, UN forces killed 50 Katangese gendarmes before securing downtown Élisabethville, the local Gendarmerie headquarters, the radio station, and Tshombe's presidential palace. Early on 29 December, the ONUC Air Division launched a surprise assault on the Kolwezi airfield, inflicting serious damage to the installation's facilities. Further sorties resulted in the destruction of seven Katangese aircraft, though the Katangese Air Force managed to evacuate several planes toPortuguese Angola

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

...

. The Air Force remained grounded for the rest of the operation. At midday an ONUC formation advanced down the Kipushi road to sever the Katangese lines to Rhodesia. Gendarmes were well positioned in wooded heights overlooking the route, but following heavy mortar bombardment they surrendered with little opposition. Other ONUC forces seized the town of Kipushi without facing any resistance. Tshombe ordered his troops to offer determined resistance to ONUC and threatened to have bridges and dams blown up if the operation was not halted within 24 hours.

In Kamina, the gendarmes had expected an attack on 30 December, but when one failed to occur they began to drink beer and fire flares at random, possibly to boost morale. Rogue bands of gendarmes subsequently conducted random raids around the city and looted the local bank. They were attacked by Swedish and Ghanaian troops two or three kilometers northeast of Kamina the following day, and were defeated. The Katangese Gendamerie conducted a disorganised withdrawal to two camps southeast of the locale. The Swedes successfully took several gendarmerie camps and began working to stabilise the situation. Late that night a company of the Indian Rajputana Rifles encountered entrenched gendarmes and mercenaries along Jadotville Road and a gunfight ensued. Two mercenaries captured during the clash revealed that confusion and desertion were occurring among the Katangese forces. Altogether the Indian forces faced unexpectedly light resistance and reached the east bank of the Lufira on 3 January 1963. Mercenaries withdrew to Jadotville the next day after destroying a bridge over the Lufira River. UN forces found a bridge upstream and used rafts and helicopters to cross and neutralised Katangese opposition on the far side of the river, occupying Jadotville.

Muké attempted to organise a defence of the town, but Katangese forces were in disarray, being completely caught off-guard by the UN troops' advance. UN forces briefly stayed in Jadotville to regroup before advancing on Kolwezi, Sakania, and Dilolo. Between 31 December 1962 and 4 January 1963, international opinion rallied in favour of ONUC. Belgium and France strongly urged Tshombe to accept Thant's Plan for National Reconciliation and resolve the conflict. On 8 January, Tshombe reappeared in Élisabethville. The same day Prime Minister Adoula received a letter from the chiefs of the most prominent Kantangese tribes pledging allegiance to the Congolese government and calling for Tshombe's arrest. Thant expressed interest in negotiating with Tshombe, saying "If we could convince shombethat there is no more room for maneuvering and bargaining, and no one to bargain with, he would surrender and the gendarmerie would collapse." Tshombe soon expressed his willingness to negotiate after being briefly detained and released, but warned that any advance on Kolwezi would result in the enactment of a

In Kamina, the gendarmes had expected an attack on 30 December, but when one failed to occur they began to drink beer and fire flares at random, possibly to boost morale. Rogue bands of gendarmes subsequently conducted random raids around the city and looted the local bank. They were attacked by Swedish and Ghanaian troops two or three kilometers northeast of Kamina the following day, and were defeated. The Katangese Gendamerie conducted a disorganised withdrawal to two camps southeast of the locale. The Swedes successfully took several gendarmerie camps and began working to stabilise the situation. Late that night a company of the Indian Rajputana Rifles encountered entrenched gendarmes and mercenaries along Jadotville Road and a gunfight ensued. Two mercenaries captured during the clash revealed that confusion and desertion were occurring among the Katangese forces. Altogether the Indian forces faced unexpectedly light resistance and reached the east bank of the Lufira on 3 January 1963. Mercenaries withdrew to Jadotville the next day after destroying a bridge over the Lufira River. UN forces found a bridge upstream and used rafts and helicopters to cross and neutralised Katangese opposition on the far side of the river, occupying Jadotville.

Muké attempted to organise a defence of the town, but Katangese forces were in disarray, being completely caught off-guard by the UN troops' advance. UN forces briefly stayed in Jadotville to regroup before advancing on Kolwezi, Sakania, and Dilolo. Between 31 December 1962 and 4 January 1963, international opinion rallied in favour of ONUC. Belgium and France strongly urged Tshombe to accept Thant's Plan for National Reconciliation and resolve the conflict. On 8 January, Tshombe reappeared in Élisabethville. The same day Prime Minister Adoula received a letter from the chiefs of the most prominent Kantangese tribes pledging allegiance to the Congolese government and calling for Tshombe's arrest. Thant expressed interest in negotiating with Tshombe, saying "If we could convince shombethat there is no more room for maneuvering and bargaining, and no one to bargain with, he would surrender and the gendarmerie would collapse." Tshombe soon expressed his willingness to negotiate after being briefly detained and released, but warned that any advance on Kolwezi would result in the enactment of a scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

policy. Tshombe fled to Northern Rhodesia on a Rhodesian Air Force plane, and managed to reach Kolwezi, the only significant location that remained under Katangese control.

On 12 January a Swedish ONUC battalion surprised two gendarmerie battalions in Kabundji, seized their weapons, and directed them to return to their civilian livelihoods. Meanwhile, mercenaries in the Kolwezi area had taken Tshombe's threats about a scorched earth policy seriously and had planted explosives on all nearby bridges, the Nzilo Dam (which provided most of Katanga's electricity), and most of the UMHK mining facilities. UMHK officials privately told Tshombe they were withdrawing their support for succession. Muké vainly attempted to organise the 140 mercenaries and 2,000 gendarmes under his command to prepare a final defence of Kolwezi. His efforts, undermined by the force's low morale and indiscipline, were further hampered by an influx of refugees. Tshombe ordered the Katangese garrison of Baudouinville to surrender to besieging UN and ANC forces. Instead, they and most of the population deserted the city while a handful of gendarmes near Kongolo laid down their arms to Nigerian and Malaysian soldiers. On 14 January, Indian troops found the last intact bridge into Kolwezi. After a brief fight with gendarmes and mercenaries they secured it and crossed over, stopping at the city outskirts to await further instruction. At a final meeting with his mercenary commanders, Tshombe ordered all remaining Katangese armed forces to withdraw to Portuguese Angola. Mercenary Jean Schramme was appointed to be commander of an army in exile, while mercenary Jeremiah Puren was ordered to evacuate what remained of the Katangese Air Force, along with necessary military equipment and the Katangese treasury. This was accomplished via air and railway. Rhodesian operatives assisted in smuggling the gold reserves out of the country. The last of Schramme's mercenaries and gendarmes were evacuated on 25 January.

On 15 January, Tshombe sent a formal message to Thant, "I am ready to proclaim immediately before the world that the Katanga's secession is ended." He offered to return to Élisabethville to oversee the implementation of Thant's proposal for reunification if Prime Minister Adoula granted amnesty to himself and his government. At a press conference, Adoula accepted Tshombe's proposition and announced that what remained of the Katangese Gendarmerie would be integrated into the ANC. Total statistics on Katangese Gendarmerie and mercenary casualties from Operation Grandslam are unknown. Following the operation the UN was able to confirm that Portuguese Angola, South Africa, and Northern Rhodesia had assisted the Katangese in arming their air force.

Angola and the Congo (1963–1967)

Exile, return, and fighting the Simba rebellion

After the defeat of the State of Katanga, plans to disarm or integrate the gendarmes were made. On 8 February 1963, General Muké and several of his officers pledged their allegiance to President Kasa-Vubu. However, of the estimated 14,000–17,000 gendarmes, only 3,500 registered for integration, and only around 2,000–3,000 became part of the ANC. Those who integrated suffered threats and violence, and were given lower ranks. An estimated 7,000 returned to civilian life, and a further 8,000 escaped disarmament. Of the 8,000, some found work in security, and thousands of others were reported to be roaming "in the bush in South Katanga". Many could not return to their homes, and were considered outcasts. Meanwhile, the Congolese government seized documents revealing that Tshombe was maintaining contact with foreign mercenaries. Fearing arrest and claiming political persecution, he fled to Paris, France, in June 1963, eventually settling in Madrid, Spain. From there he developed plans with his gendarmerie commanders for a return to power, further complicating the central government's efforts to absorb the force. United Nations efforts at reconciliation were ended as ONUC focused on withdrawing its own forces from Katanga in December 1963. The ANC began raiding pro-secession communities, as gendarmes continued to roam Northern Rhodesia, Angola and Katanga. The gendarmes in the Congo-Rhodesia border region would go into Rhodesian communities to barter for food and sometimes raid and steal supplies. Since most of the local Rhodesian residents were Lunda, many of the Lunda Katangese avoided the ANC security operations by simply disguising themselves in the indigenous communities. Tshombe's Katangese government had enjoyed close relations with the administrators of Portuguese Angola, particularly since both were opposed to communism. Nevertheless, the Portuguese were initially overwhelmed by the large number of gendarmes and mercenaries that arrived under Schramme. As the Congolese government had given backing to theNational Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independenc ...

, a nationalist anti-colonial rebel group, the Portuguese concluded that the gendarmes could serve as a counterweight to nationalist agitation and accommodated them in Luso. As more gendarmes gathered in Angola in late 1963, additional camps were established at Cazambo, Cazage, Lutai, and Lunguebungo. Mindful of the international ramifications of harbouring an armed group, the Portuguese portrayed the gendarmes and mercenaries as "refugees". While most of the standard personnel lived in squalor and lacked basic necessities, the officers were kept in hotel rooms paid for by Tshombe. Many were not paid while in exile. A new command structure was established for the Gendarmerie in Angola under Major Ferdinand Tshipola with Antoine Mwambu as chief of staff. Four groups operated autonomously under their own mercenary commanders. Schramme completely rejected Tshipola's authority. By 1964, two of the camps had become dedicated training facilities. Mercenaries traveled from Katanga to Angola via Rhodesia to relay messages between Tshombe, the gendarmes, and the mercenaries, with logistical support from Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kno ...

.

From exile, Tshombe continued to plot his return to power in Katanga by use of the mercenaries and ex-gendarmes. He made entreaties to leftist Congolese dissidents in Brazzaville, causing consternation in the Congolese government. By April 1964 an additional 3,000–4,000 Katangese had crossed into Angola and joined the gendarmes, and Tshombe was directing the re-mobilization of the force. However, that year two leftist rebellions overtook the Congolese government; one in the Kwilu region and another in the east, waged by the " Simbas." With the ANC lacking cohesion, Adoula's government was unable to handle the insurrections. Tshombe was invited to return to the Congo to assist in negotiating a political solution, and in July 1964 he was installed as Prime Minister with the hope that he could reach an agreement with the rebels and that his presence would ensure no new secession attempts in Katanga.

Immediately after becoming Prime Minister, Tshombe recalled some of the gendarmes in Angola back to the Congo to suppress the insurrections. These gendarmes, expecting to reignite the secession, were surprised by their new task and only took orders directly from Tshombe. Some of the units also clashed with one another, due to rivalries between Katangese and mercenary officers. A couple thousand remained in Angola. Tsombe's government also recruited former gendarmes in Jadotville and Élisabethville, who reenlisted primarily to regain their pay. These forces formed their own units which were then tendentiously integrated into the ANC. At least 6,000 additional ex-gendarmes were integrated into the police force of the new province of South Katanga. With support from Belgium and the United States, the gendarmes made steady progress in recapturing territory in late 1964. By 1965 they were deployed in mopping-up operations. The use of mercenaries bothered President Kasa-Vubu, which created divisions with the commander of the ANC, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997) was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the president of Zaire from 1965 to 1997 (known as the Democratic Republic o ...

, who appreciated their effectiveness. Kasa-Vubu also developed a rivalry with Tshombe, and in October 1965 dismissed him from the premiership. Political deadlock ensued as Parliament refused to approve Kasa-Vubu's new appointee to the premiership, and in November Mobutu launched a coup and assumed the presidency. Tshombe returned to exile in Spain and resumed planning for a return to power. New mercenaries were recruited for the purpose with Portuguese support.

Rebellions and return to exile

By mid-1966 the Katangese forces in the Congo were still serving in the ANC in standalone units. About 1,000 mercenaries and 3,000 former gendarmes were deployed in South Kivu and Kisangani (formerly Stanleyville), tasked with suppressing the remaining Simba rebels. They were militarily effective, but retained significant political distance from Mobutu's new regime and had tense relations with the regular ANC units. In July 1966 roughly 3,000 gendarmes and 240 mercenaries, upset about irregular pay, rebelled in Kisangani. Led by Tshipola, since made a colonel, the force seized control of the city and killed several ANC officers including Colonel Joseph-Damien Tshatshi, the commander responsible for Congolese police operations in Katanga in 1963. Tshipola issued a memo accusing Tshatshi of discriminating against the ex-gendarmes and denouncing Mobutu's coup. Other mercenaries revolted in Isiro and Watso before joining Tshipola's force in Kisangani. The insurrection was suppressed in September with the assistance of units led by mercenary Bob Denard and Schramme. Following this, several ex-gendarmes—including members of the Katangese police—fled to Angola. In March 1967 Mobutu convened a military tribunal to try the ex-gendarmes responsible for the mutiny. Tshombe was also tried '' in absentia''. The tribunal sentenced Tshombe to death and criminalized the Katangese Gendarmerie retrospectively as an "irregular army". Mobutu held the Gendarmerie to be a criminal organization for the remainder of his rule. After the trial, all the gendarmes were referred to as 'mercenaries' by Congolese press. Tshombe's plans to use the remaining gendarmes and mercenaries to stage a rebellion were disrupted by the hijacking of his plane in June and ultimate detention inAlgiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital city, capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des ...

. A second wave of mutinies broke out on July 5, 1967 in Bukavu

Bukavu is a city in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), lying at the extreme south-western edge of Lake Kivu, west of Cyangugu in Rwanda, and separated from it by the outlet of the Ruzizi River. It is the capital of the South Kivu pr ...

and Kisangani after it was revealed that the ANC planned to disband its mercenary units. The mutinies were led by European mercenaries. An estimated 600 former gendarmes led by Schramme were present in Kisangani during the mutiny. Under pressure from the ANC, Schramme was forced to evacuate the city with 300 mercenaries and a few thousand gendarmes. They reached Bukavu, and a secessionist state was declared. A plan was proposed by the International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signa ...

to evacuate 950 gendarmes and around 650 of their dependents to Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are ...

. Schramme and Mobutu objected, and the plan did not go forward. Though the ANC continued fighting, around 900 gendarmes gave up their arms and crossed into Rwanda. At the end of the mutinies, the gendarmes agreed to a cease-fire proposed by Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

Secretary General Diallo Telli

Boubacar Diallo Telli (1925 – February 1977) was a Guinean diplomat and politician. He helped found the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and was the second secretary-general of the OAU between 1964 and 1972. After serving as Minister of Just ...

under which they could gain amnesty by returning to the Congo. The mercenaries were expelled from Africa and returned to Europe. A brief diversionary raid was executed by Denard from November 1 to 5, 1967. Called "Operation Luciver", ex-gendarmes crossed from Angola to Katanga and occupied Kisenge and Mutshatsha before being defeated by the ANC. In the Congo, reprisal raids against former gendarmes then occurred; the ANC killed several of their leaders.

Later history (1967-present)

The straggling gendarmes who returned to Angola after the defeats in the Congo initially maintained hope of being able to fight for their return within a few years. Their designs were nevertheless disrupted by Tshombe's detention, the departure of many of their mercenary commanders, and the increasing strength of Mobutu. The gendarmes were instead deployed by thePortuguese government

, border = Central

, image =

, caption =

, date =

, state = Portuguese Republic

, address = Official Residence of the Prime Minister Estrela, Lisbon

, appointed = President ...

in the Eastern Military Zone where they were led by Nathaniel Mbumba and fought the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) and União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement fo ...

(UNITA) during the Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

. The Portuguese had high respect for the gendarme's abilities they were called Fiéis or "the faithful". However, historian Pedro Aires Oliveira notes that the gendarmes cared more about fighting the Democratic Republic of the Congo than participating in the Angolan war and as a result were closely watched by the Portuguese authorities. 1,130 ex-gendarmes were deployed at Gafaria, and a further 1,555 at Camissombo. Some of the gendarmes were also given bounties by the De Beers

De Beers Group is an international corporation that specializes in diamond mining, diamond exploitation, diamond retail, diamond trading and industrial diamond manufacturing sectors. The company is active in open-pit, large-scale alluvial and ...

diamond company to disrupt smuggling operations in Angola.

Efforts began to formalize the presence of exiled gendarmes in Angola. In March 1968, the Fédération Nationale Congolaise was created to represent Katangese in exile. In June 1969, the Congolese National Liberation Front (FLNC) was founded. They were given further military training and in May 1971, many gendarmes began formally receiving compensation for fighting. Mbumba negotiated better conditions, training, and salaries for the soldiers in the early 1970s. In February 1971 they were formally made part of the Portuguese irregular forces. By 1974 there were an estimated 2,400 gendarmes in 16 companies.

During the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war wa ...

(from 1975 to 2002), the FLNC, composed of ex-gendarmes called the " Tigres", fought on the side of the MPLA against the National Liberation Front of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independenc ...

(FNLA). The FLNC was then involved in the Shaba Wars. The Katanga Province had been renamed Shaba Province during the rule of Mobutu, when the Congo was known as Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

. Shaba I

Shaba I was a conflict in Zaire's Shaba (Katanga) Province lasting from March 8 to May 26, 1977. The conflict began when the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo (FNLC), a group of about 2,000 Katangan Congolese soldiers who were vet ...

began on March 8, 1977, when ex-gendarmes invaded the province. Western nations came to the aid of Mobutu, and the invasion was crushed by May 26, 1977. On May 11, 1978, a second invasion, known as Shaba II began. About 3,000 to 4,000 FLNC members were involved. Western nations again supported Mobutu, and the FLNC was largely defeated by May 27. After the invasion failed, the FLNC lost support from Angola, and promptly collapsed. Some former gendarmes were incorporated into the Angolan army, were they were occasionally deployed militarily. Various groups were formed to succeed the FLNC, including the FAPAK, the MCS, and the FLNC II. The factions were divided by their goals.

The Tigres were involved in the First Congo War

The First Congo War, group=lower-alpha (1996–1997), also nicknamed Africa's First World War, was a civil war and international military conflict which took place mostly in Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo), with major spill ...

, supporting a rebellion against Mobutu. In February 1997, 2,000 to 3,000 were airlifted to Kigali